Abstract

Aims:

We aim to clarify the extent to which cardiac and peripheral impairments to oxygen delivery and utilization contribute to exercise intolerance and risk for adverse events, and how this relates to diversity and multiplicity in pathophysiological traits.

Methods:

Individuals with HFpEF and non-cardiac dyspnea (controls) underwent invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing and clinical follow-up. Hemodynamics and oxygen transport responses were compared. HFpEF patients were then categorized a priori into previously-proposed, non-exclusive descriptive clinical trait phenogroups, including cardiometabolic, pulmonary vascular disease, left atrial myopathy, and vascular stiffening phenogroups based on clinical and hemodynamic profiles to contrast pathophysiology and clinical risk.

Results:

Overall, patients with HFpEF (n=643) had impaired cardiac output reserve with exercise (2.3 L/min versus 2.8 L/min, p=0.025) and greater reliance on peripheral oxygen extraction augmentation (4.5 mL/dL versus 3.8 mL/dL, p<0.001) compared to dyspneic controls (n=219). Most (94%) HFpEF patients met criteria for at least one clinical phenogroup, and 67% fulfilled criteria for multiple overlapping phenogroups. There was greater impairment in peripheral limitations in the cardiometabolic group and greater cardiac output limitations and higher pulmonary vascular resistance during exertion in the other phenogroups. Increasing trait multiplicity within a given patient was associated with worse exercise hemodynamics, poorer exercise capacity, lower cardiac output reserve, and greater risk for HF hospitalization or death (HR 1.74, 95% CI:1.08–2.79 for 0–1 vs ≥2 phenogroup traits present).

Conclusions:

Though cardiac output response to exercise is limited in patients with HFpEF compared to those with non-cardiac dyspnea, the relative contributions of cardiac and peripheral limitations vary with differing numbers and types of clinical phenotypic traits present. Patients fulfilling criteria for greater multiplicity and diversity of HFpEF phenogroup traits have poorer exercise capacity, worsening hemodynamic perturbations, and greater risk for adverse outcome.

Keywords: Heart failure, HFpEF, phenotype, exercise capacity, outcome

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Exercise intolerance is the fundamental clinical expression of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but its pathophysiology is complex and incompletely understood.1–3 Research into the mechanisms of exercise intolerance originally focused on the heart, but there is a growing understanding that abnormalities in the periphery are also important.3–11 According to the Fick principle, oxygen consumption (VO2) is equal to the product of cardiac output (CO) and arterial-venous O2 content difference (Ca-vO2). Prior studies have reported that reduction in peak VO2 in patients with HFpEF are predominantly related to impaired CO with preserved Ca-vO2,5,7,8 impaired Ca-vO2 with preserved CO,12,13 or some combination of both abnormalities.10,14 The explanation for the discrepant results between studies remains unclear.

At the same time, it has increasingly become apparent that varying pathophysiologic mechanisms may contribute to development of HFpEF and that pathophysiologic diversity and clinical presentation at differing timepoints in the natural history of HFpEF progression results in groups of patients who share therapeutically or prognostically relevant similarities (HFpEF clinical phenogroups). Studies have attempted to characterize this multiplicity by classifying patients with HFpEF into phenogroups using unsupervised cluster analyses with various inputs.15–18 Others have proposed clinically defined phenogroups based on predominant (but potentially overlapping) physiologic or clinical pertubations.2,19 The most well-characterized clinical phenogroups are defined by the presence of obesity20,21 or diabetes22,23 (cardiometabolic), left atrial myopathy,24,25 pulmonary vascular disease,26 and heightened vascular stiffening.27,28 Diversity among individual patients in the types and number of phenotypic abnormalities present may have major implications on pathophysiology, treatment, and risk. The use of clinically defined phenogroups (as opposed to those derived from machine learning algorithms) leverages common descriptors of HFpEF patients, and reflects existing clinical classification and decision-making schemes.

No study has rigorously evaluated resting and exercise invasive hemodynamics, metabolic performance, and risk for adverse outcome in patients with HFpEF using these commonly used, clinically-defined phenogroups. To address this knowledge gap, we evaluated a large cohort of patients with and without HFpEF to characterize the distribution and overlap of clinically defined HFpEF phenogroups in a large series of consecutively-evaluated individuals, and then compared invasive hemodynamic signatures and measures of oxygen delivery during symptom-limited graded exercise across phenogroups, as well as clinical outcomes. We hypothesized that patients with different HFpEF phenogroup traits would display varied contributions from CO limitations and peripheral oxygen transport and utilization deficits, and that the presence of increasing numbers of phenogroups would be associated with more adverse exertional hemodynamics, greater impairments in aerobic capacity, and higher risk for adverse events.

Methods

Study population

Consecutive patients undergoing clinically indicated invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN between December 2007 and July 2021 were evaluated. Patients with HFpEF were identified as those with symptoms of lifestyle-limiting dyspnea and fatigue with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥50% and pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP) ≥15 mmHg at rest or a ≥25 mmHg during exercise.29 Patients were excluded from analysis if they had evidence of > moderate valvular heart disease or clinically significant coronary artery disease, defined as patients with acute coronary syndromes or need for clinical need for revascularization in the opinion of investigators. Controls were defined by individuals with symptoms of unexplained exercise intolerance and no evidence of heart failure (normal resting and exercise PAWP) and no pulmonary hypertension at rest (resting mean PA pressure < 20 mmHg and resting pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) < 2 WU). For individuals who underwent multiple studies during the time-period, only the first study was included in the final data set. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the institutional review board of the Mayo Clinic.

HFpEF Phenogroups

Phenogroups were defined a priori based upon the existing literature within the HFpEF cohort as follows: (1) cardiometabolic (CM) phenotype was defined by presence of obesity (body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2) and/or diabetes;20–23 (2) left atrial (LA) myopathy phenotype was defined as a LA volume index >34 mL/m2 or any history of atrial fibrillation (AF);24,25 (3) pulmonary vascular disease (PVD) phenotype was defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery (mPAP) >20 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance >2 WU at rest;30 (4) vascular stiffening phenotype was defined by pulse pressure at rest >90 mmHg or total arterial compliance index <0.5 mL/m2/mmHg.28 These groups are not mutually exclusive such that individuals can fulfil trait criteria for >1 phenogroup, and any two phenogroups may share a proportion of individual patients. Patients not fulfilling any phenotype-specific criteria were classified as “no phenogroup.”

Hemodynamic assessment

Baseline ventricular morphology, systolic and diastolic function, and atrial volumes were obtained by transthoracic echocardiography at rest according to recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography.31 Right heart catheterization was performed in the supine position using previously described methods.5,8,26 Right atrial (RAP), mean pulmonary arterial (mPA), and PA wedge pressure (PAWP) pressures were assessed manually at end-expiration at rest, 20 W incremental stages of exercise, and at peak exercise. Systemic systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressures were measured directly and continuously via radial arterial catheter.

Breath-by-breath expired gas analysis was performed at rest and during exercise (MedGraphics, St. Paul, MN, USA) to measure oxygen consumption (VO2). Arterial-venous oxygen content difference (Ca-vO2) was measured directly as the difference between systemic and PA O2 contents. Oxygen extraction was calculated as Ca-vO2/CaO2. Cardiac output (CO) was determined by the direct Fick method (CO=VO2/Ca-vO2). Pulmonary vascular resistance was calculated by (mPA–PAWP)/CO. Total arterial compliance index was calculated as stroke volume index divided by pulse pressure.27 Comparisons of hemodynamic responses to exercise were made both at matched objective external workload (20 watts) and at the individual peak workloads achieved (based upon patient volitional effort).

Outcome Assessment

Patient follow-up was initiated on the day of invasive hemodynamic cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Mortality data were ascertained from medical records, death certificates, obituaries, and notices of death in the local newspapers. Data on all deaths were obtained from the State of Minnesota annually. Heart failure hospitalizations were determined from the Mayo Clinic electronic medical record cross referencing all medical centers that utilize the Epic electronic medical record (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). Patients were censored at last follow up contact.

Statistical analysis

Continuous measurements are reported as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed variables or median (interquartile range) for non-normal distributions. Between group differences were tested with Student t test, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (%) and evaluated by Pearson’s χ2. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Event rates were compared using Kaplan–Meier curve analysis. Risk of the composite outcome was compared among between phenogroups and based upon the number of phenogroups to which each patient fulfilled criteria for. Cox proportional hazards models were created to assess prognostic relationships independent of relevant baseline group differences including age, sex, and body mass index. The statistical analysis utilized BlueSky Statistics software v. 7.10 (BlueSky Statistics LLC, Chicago, IL, USA) and SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28.0.0.0 IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics in HFpEF and Controls

Patients with HFpEF (n=643) were older and were more likely to be obese than controls with non-cardiac causes of dyspnea (n=219) (Table 1). There was no difference in the proportion of women between the two groups. As expected, patients with HFpEF were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation, and were accordingly more likely to be taking beta blockers, renin-angiotensin aldosterone antagonists, or diuretics as compared to controls. Baseline NT-proBNP was higher among HFpEF patients (Table 1).

Table 1 –

Baseline characteristics.

| Control (N=219) | HFpEF (N=643) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Age | 56.1 (13.8) | 67.3 (11.2) | < 0.001 |

| Sex (female, %) | 57.1% | 54.7% | 0.54 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.0 (5.6) | 33.7 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities and Medications | |||

| Obese (%) | 33.8% | 68.1% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 12.3% | 26.9% | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 65.3% | 87.9% | < 0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 24.7% | 32.3% | 0.03 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 2.2% | 33.5% | <0.001 |

| RAAS blocker (%) | 31.5% | 44.5% | < 0.001 |

| Beta blocker (%) | 32.0% | 52.6% | < 0.001 |

| Diuretic (%) | 23.7% | 56.0% | < 0.001 |

| Laboratories | |||

| NT-ProBNP (pg/mL) | 67 (31, 164) | 250 (87, 714) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5 (1.4) | 13.1 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 76.6 (19.3) | 64.7 (20.0) | <0.001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 64.5 (5.4) | 64.3 (5.8) | 0.66 |

| Rest physiology | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72 (64, 80) | 68 (61, 76) | 0.003 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 136 (23) | 148 (23) | <0.001 |

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 5 (2) | 10 (4) | <0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 15 (13, 18) | 26 (21, 31) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 8 (3) | 17 (5) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) | 1.3 (0.9, 1.6) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.7) | <0.001 |

| Arterial saturation (%) | 97 (96, 98) | 96 (94, 97) | <0.001 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 81 (15) | 73 (13) | <0.001 |

| CaO2 (mL/dL) | 16.9 (1.9) | 16.1 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| PvO2 (mmHg) | 38.4 (4.2) | 36.2 (3.7) | 0.002 |

| CvO2 (mL/dL) | 12.8 (1.8) | 11.5 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 5.3 (4.7, 6.3) | 5.2 (4.3, 6.3) | 0.04 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.9 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 4.1 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Oxygen extraction (%) | 24.4 (5.2) | 28.6 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 225 (56) | 239 (63) | 0.004 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.5 (0.6) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; NT-proBNP, NT-proB type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; RA, right atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; PaO2, arterial oxygen partial pressure; CaO2, arterial oxygen content; PvO2, venous oxygen partial pressure; CvO2, venous oxygen content; Ca-vO2, arterial-venous oxygen difference; VO2, oxygen consumption.

Exercise Hemodynamics in HFpEF and Controls

Resting systemic blood pressure, right atrial pressure, mean pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary artery wedge pressure, and pulmonary vascular resistance were higher in HFpEF patients than controls (Table 1). Absolute VO2, Ca-vO2, and oxygen extraction fraction were higher in HFpEF patients as compared to controls (Table 1). Cardiac index and resting VO2 scaled to weight (VO2/kg) were lower in HFpEF patients (Table 1).

At a matched external workload of 20 W, patients with HFpEF had lower CO and cardiac index, and had a smaller absolute increase in CO from baseline to 20 W. At 20 W, Ca-vO2 (Table 2) and oxygen extraction (Table S1) were higher in HFpEF versus controls. Indexing changes in Ca-vO2 and CO from baseline to 20 watts to the corresponding change in VO2 (ΔCa-vO2/ΔVO2, ΔCO/ΔVO2) revealed a greater increase in ΔCa-vO2 than ΔCO for any given change in VO2 among HFpEF patients overall (Table 2).

Table 2 –

Exercise Responses in HFpEF and Controls.

| 20 watts | Control (N=219) | HFpEF (N=643) | P value | Peak | Control (N=219) | HFpEF (N=643) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | 97.4 (18.7) | 90.3 (16.7) | <0.001 | Heart rate (bpm) | 118.6 (24.8) | 100.1 (20.6) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 163 (29) | 174 (29) | <0.001 | Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 173 (32) | 180 (33) | 0.02 |

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 8 (4) | 18 (7) | <0.001 | RA pressure (mmHg) | 8 (5, 10) | 18 (14, 24) | <0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 26 (6) | 43 (11) | <0.001 | Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 27 (7) | 46 (11) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 15 (5) | 28 (7) | <0.001 | PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 15 (5) | 31 (6) | <0.001 |

| PVR (WU) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.9 (1.2, 2.9) | <0.001 | PVR (WU) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | <0.001 |

| PVR ≥1.74 WU (%) | 26.6% | 55.5% | <0.001 | PVR ≥1.74 WU (%) | 14.9% | 41.5% | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 7.9 (6.8, 9.3) | 7.3 (5.8, 9.1) | 0.005 | Cardiac output (L/min) | 10.4 (8.6, 12.5) | 8.7 (6.9, 11.1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 4.4 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.0) | <0.001 | Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 5.5 (4.4, 6.5) | 4.2 (3.4, 5.0) | <0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 619 (528, 732) | 655 (544, 777) | 0.05 | VO2 (mL/min) | 985 (793, 1246) | 848 (673, 1064) | <0.001 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 8.1 (2.4) | 7.0 (2.0) | <0.001 | VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 12.5 (9.6, 15.3) | 8.9 (7.3, 11.2) | <0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 7.9 (1.6) | 9.1 (1.7) | <0.001 | Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 9.4 (2.0) | 10.0 (2.2) | 0.002 |

| ΔCO (L/min) | 2.7 (2.1) | 2.3 (1.9) | 0.018 | ΔCO (L/min) | 4.8 (3.3, 6.8) | 3.4 (2.1, 5.3) | <0.001 |

| ΔCa-vO2 difference | 3.8 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.5) | <0.001 | ΔCa-vO2 difference | 5.4 (2.0) | 5.4 (2.0) | 0.575 |

| ΔO2 Extraction | 22.0 (7.4) | 26.9 (7.9) | <0.001 | ΔO2 Extraction | 29.0 (9.9) | 30.9 (9.9) | 0.011 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 6.7 (4.2, 8.5) | 4.9 (3.0, 6.7) | <0.001 | ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 6.4 (5.0, 7.7) | 5.8 (4.0, 7.2) | <0.001 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 9.2 (7.2, 10.7) | 10.4 (7.7, 14.3) | <0.001 | ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 6.6 (5.3, 8.8) | 8.2 (6.5, 11.6) | <0.001 |

| Peak RER | 1.04 (0.12) | 1.01 (0.13) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: RA, right atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; VO2, oxygen consumption; Ca-vO2, arterial-venous oxygen difference; CO, cardiac output; RER, respiratory exchange ratio.

Patients with HFpEF achieved lower levels of peak exercise than dyspneic controls (40 (20, 60) W versus 60 (40, 95) W, p<0.001). At peak exercise, CO and VO2 were again lower in HFpEF than controls, while Ca-vO2 remained higher in HFpEF patients. The increase in CO from rest to peak exercise and ΔCO/ΔVO2 was lower in HFpEF patients, while ΔCa-vO2diff/ΔVO2 was higher in HFpEF patients at peak exercise (Table 2).

Phenogroup analysis

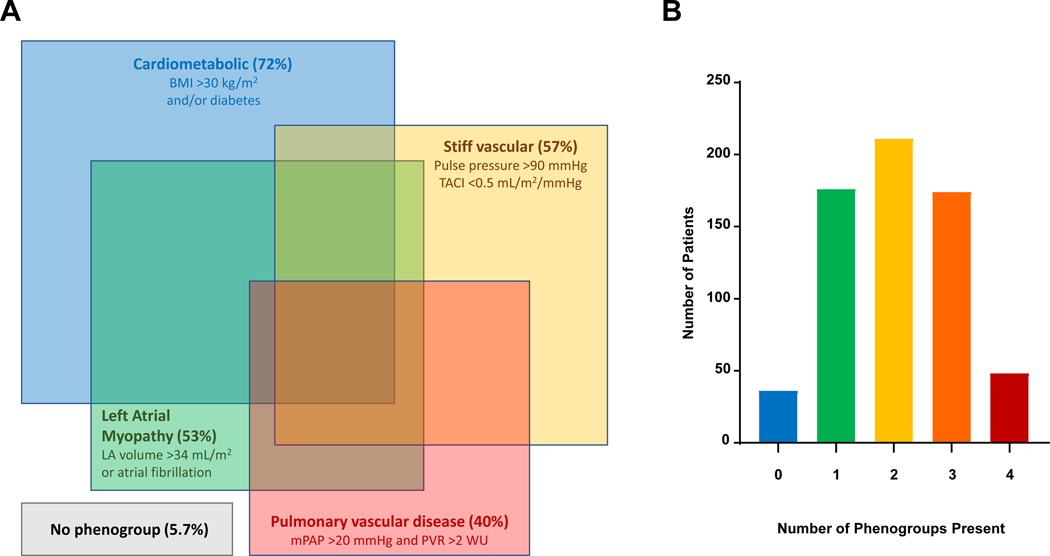

Among the 643 consecutively evaluated patients with HFpEF, 607 (94.4%) met criteria for at least one of the four phenogroups (Table 3). There was considerable overlap between groups, with 67% of HFpEF patients fulfilling criteria for >1 phenogroup (Figure 1, Table S4). The cardiometabolic phenogroup criteria encompassed 72% of all HFpEF patients. The LA myopathy, PVD, and stiff vascular criteria identified 53%, 40%, and 57% of patients with HFpEF, respectively. Those meeting LA myopathy criteria had lower LVEF and higher LV mass than patients who did not, but no other phenogroup criteria were associated with differences in LVEF or LV mass (Table 3).

Table 3 –

Characteristics of HFpEF patients with or without Specific Phenogroup Traits

| No Cardiometabolic (28%) | Cardiometabolic (72%) | No LA myopathy (47%) | LA myopathy (53%) | No pulmonary vascular disease (60%) | Pulmonary vascular disease (40%) | Non-Stiff vascular (43%) | Stiff vascular (57%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometrics | ||||||||

| Age | 70.3 (11.0) | 66.1 (11.1)** | 62.9 (11.9) | 71.4 (8.8)** | 65.1 (11.4) | 71.0 (9.5)** | 64.0 (11.7) | 70.2 (9.6)** |

| Women (%) | 59.3% | 53.0% | 56.8% | 53.0% | 50.5% | 62.7%* | 48.1% | 61.1%* |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.0 (2.8) | 36.7 (6.6)† | 34.9 (8.1) | 32.5 (6.8)** | 34.6 (7.6) | 32.0 (6.7)** | 34.2 (7.3) | 32.9 (7.3)* |

| Comorbidities and Medications | ||||||||

| Obese (%) | 0.0% | 94.4%† | 74.3% | 62.5%* | 72.8% | 58.4%** | 71.4% | 63.4% |

| Diabetes (%) | 0.0% | 37.2%† | 26.4% | 26.8% | 22.4% | 33.5%* | 24.2% | 29.4% |

| Hypertension (%) | 83.8% | 89.4% | 85.1% | 90.2% | 89.5% | 94.3% | 87.0% | 93.7%* |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 29.6% | 33.4% | 30.0% | 31.6% | 36.8% | 36.8% | 30.7% | 36.3% |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 42.7% | 29.8%* | 0.0% | 63.7%† | 24.9% | 44.5%** | 27.7% | 36.1%* |

| RAAS blocker (%) | 40.2% | 46.1% | 41.3% | 46.7% | 43.1% | 50.7% | 43.3% | 47.9% |

| Beta blocker (%) | 49.7% | 53.7% | 43.2% | 60.7%** | 48.9% | 61.2%* | 52.8% | 53.1% |

| Diuretic (%) | 50.8% | 58.0% | 50.5% | 61.0%* | 50.2% | 65.6%** | 53.2% | 58.7% |

| Laboratories and Echocardiogram | ||||||||

| NT-Pro BNP (pg/mL) | 429 (149, 971) | 196 (70, 583)** | 102 (53, 234) | 551 (235, 1078)** | 164 (57, 364) | 485 (184, 1347)** | 185 (59, 473) | 363 (121, 967)** |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.1 (1.7) | 13.1 (1.6) | 13.2 (1.6) | 13.0 (1.6) | 13.2 (1.5) | 12.9 (1.6)* | 13.3 (1.6) | 12.9 (1.6)* |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 64.4 (18.7) | 64.8 (20.5) | 69.6 (20.2) | 60.3 (18.7)** | 69.3 (19.5) | 57.9 (19.5)** | 69.4 (19.8) | 60.2 (19.6)** |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 64.1 (6.0) | 64.3 (5.8) | 65.0 (5.4) | 63.7 (6.1)* | 64.9 (5.6) | 64.9 (6.2) | 64.5 (5.9) | 65.0 (5.7) |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (mm) | 47.4 (4.5) | 49.8 (5.1)** | 48.9 (4.8) | 49.2 (5.3) | 49.6 (5.0) | 48.2 (5.1)* | 49.9 (5.2) | 48.7 (5.0)* |

| LA volume index (mL/m2) | 35.9 (28.3, 45.0) | 31.3 (25.0, 40.2)** | 26.0 (22,7, 30.3) | 41.0 (35.8, 48.5)** | 30.5 (24.5, 37.8) | 36.2 (29.1, 45.2)** | 31.2 (24.6, 39.9) | 33.4 (26.9, 42.7)* |

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 87.5 (74.0, 102.5) | 87.6 (76.5, 102.9) | 82.6 (73.3, 96.8) | 91.6 (79.0, 107.4)** | 88.0 (76.5, 101.0) | 87.3 (77.2, 105.1) | 87.8 (76.5, 103.7) | 87.1 (76.6, 102.3) |

| Rest physiology | ||||||||

| Ca-VO2 (mL/dL) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.7 (1.0)* | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.8 (0.9)** | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.7 (0.9)** |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 147 (24) | 149 (23) | 148 (23) | 149 (24) | 146 (23) | 147 (25) | 132 (18) | 161 (21)** |

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 9 (4) | 11 (4)** | 10 (4) | 10 (4) | 9 (4) | 10 (4)* | 10 (4) | 10 (4) |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 25 (20, 30) | 26 (22, 32)* | 24 (21, 29) | 27 (22, 35)** | 23 (19, 27) | 29 (24, 37)† | 24 (20, 29) | 27 (22, 34)** |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 16 (5) | 17 (6)* | 16 (5) | 18 (6)** | 16 (6) | 17 (6) | 16 (5) | 17 (6)* |

| PVR (WU) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.8) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.2) | 2.0 (1.3, 3.0)** | 1.2 (0.9, 1.7) | 2.9 (2.2, 3.8) † | 1.4 (1.0, 2.0) | 2.2 (1.3, 3.2)** |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.6 (3.9, 5.7) | 5.4 (4.4, 6.5)** | 5.5 (4.5, 6.6) | 4.9 (4.2, 5.9)** | 5.7 (4.7, 6.7) | 4.4 (3.7, 5.2)** | 5.8 (4.9, 6.9) | 4.7 (3.9, 5.6)** |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.7)** | 2.7 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.5)** | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.6)** |

Abbreviations: LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricular; RAAS, renin angiotensin aldosterone system; NT-proBNP, NT-proB type natriuretic peptide; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; Ca-vO2, arterial-venous oxygen difference; RA, right atrium; PA, pulmonary artery.

p<0.05

p<0.001

statistical comparison not appropriate because group differences are based upon phenogroup definition

Figure 1.

[A] Proportions and distributions of non-exclusive HFpEF phenogroups. Each colored square represents distinct phenogroups among all patients with HFpEF in the study cohort. Each square’s area is proportional to frequency of its respective phenogroup and the frequency of overlap with other phenogroups. The cardiometabolic phenogroup was the most common (present among 72% of the HFpEF cohort, blue), followed by the stiff vascular (57%, yellow), left atrial myopathy (53%, green) and pulmonary vascular (40%, red) phenogroups. A small proportion (5.7%) of all patients with HFpEF belonged to no phenogroups. [B] Histogram of the phenogroup burden among patients with HFpEF. Most patients with HFpEF (94%) belonged to at least one phenogroup, and 67% of HFpEF patients belonged to 2 or more phenogroups.

Patients meeting (versus not) cardiometabolic criteria were younger, more obese (by design), had lower NT-proBNP levels, and at rest, had higher biventricular filling pressures, higher CO, cardiac index (Table 3), similar arterial O2 content (CaO2), higher total oxygen consumption, lower oxygen consumption indexed to weight and similar O2 extraction (Table 3, Table S2). Left atrial volume index was lowest in those with cardiometabolic traits.

Patients meeting (versus not) LA myopathy criteria were older and less obese, had higher NT-proBNP and lower eGFR, and at rest, had higher mean PA pressure and PVR, lower CO and cardiac index (Table 3), lower CaO2 and higher O2 extraction (Table S2).

Patients meeting (versus not) PVD criteria were older and less obese, had higher NT-proBNP and lower eGFR and at rest, had higher mean PA pressure and PVR (by design), lower CO and cardiac index (Table 3), lower CaO2 and higher O2 extraction (Table S2).

Patients meeting (versus not) the stiff vascular criteria were older, more likely female, had higher BMI, higher NT-proBNP and lower eGFR, and at rest, had higher systolic blood pressure, mean PA pressure, PVR, and PAWP, lower CO, cardiac index (Table 3) and CaO2 but higher O2 extraction (Table 3, Table S2).

In summary, at rest, across the different phenogroups, phenogroup criteria positive (versus negative) patients had variable differences in right and left filling pressures. However, based on other variables, two different patterns emerged. Patients meeting (versus not) cardiometabolic criteria had similar Ca-VO2 and cardiac index, higher CO, smaller LA volume index, and lower PVR. With all other (LA myopathy, PVD and stiff vascular) phenogroups, criteria positive (versus negative) patients had higher Ca-VO2, lower CO and cardiac index, greater LA dilatation, and higher PVR.

Exercise performance and hemodynamics in Phenogroups

At 20 W exercise, patients meeting (versus not) cardiometabolic criteria had higher mean PA and right atrial pressure with a trend towards higher mean PA pressure, higher CO, similar cardiac index and PVR, higher O2 consumption and lower O2 consumption relative to body weight (Table 4). Compared to baseline, at 20 W, cardiometabolic criteria positive (versus negative) patients had less ability to augment Ca-vO2 relative to the change in VO2 with exercise but there was no difference in the CO response relative to change in VO2.

Table 4 –

HFpEF Phenogroup Responses to Exercise.

| HFpEF phenogroup (−) | HFpEF phenogroup (+) | P value | HFpEF phenogroup (−) | HFpEF phenogroup (+) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 watts Exercise | Peak Exercise | |||||

| Cardiometabolic | 72% | |||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 17 (6) | 19 (7) | <0.001 | 17 (6) | 20 (7) | <0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 41 (11) | 44 (11) | 0.005 | 43 (10) | 47 (11) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 27 (7) | 28 (7) | 0.050 | 30 (5) | 32 (7) | <0.001 |

| PVR (WU) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.0) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.9) | 0.922 | 1.6 (1.0, 2.6) | 1.5 (0.9, 2.4) | 0.306 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 6.4 (5.3, 7.8) | 7.8 (6.0, 9.6) | <0.001 | 7.4 (6.0, 9.5) | 9.2 (7.4, 11.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.0) | 0.736 | 4.1 (3.3, 5.1) | 4.2 (3.4, 5.0) | 0.594 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 592 (152) | 698 (205) | <0.001 | 796 (289) | 938 (322) | <0.001 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 8.1 (2.1) | 6.6 (1.8) | <0.001 | 10.8 (3.8) | 9.0 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 9.1 (2.0) | 9.1 (1.7) | 0.639 | 10.2 (2.5) | 9.9 (2.1) | 0.149 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 4.7 (3.3, 6.5) | 5.1 (2.5, 6.8) | 0.725 | 5.3 (3.7, 7.0) | 5.8 (4.2, 7.2) | 0.168 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 12.2 (9.6, 15.6) | 9.5 (7.4, 13.2) | <0.001 | 9.9 (7.1, 13.8) | 7.8 (6.0, 10.6) | <0.001 |

| Left atrial myopathy | 53% | |||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 17 (6) | 19 (7) | <0.001 | 18 (7) | 20 (7) | <0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 41 (11) | 46 (11) | <0.001 | 44 (11) | 48 (10) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 27 (7) | 29 (7) | <0.001 | 31 (7) | 32 (6) | 0.0354 |

| PVR (WU) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.4) | <0.001 | 1.2 (0.8, 1.9) | 1.8 (1.1, 3.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 8.3 (2.6) | 7.1 (2.2) | <0.001 | 9.8 (7.8, 12.1) | 7.9 (6.2, 9.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.0) | <0.001 | 4.5 (3.8, 5.5) | 3.9 (3.1, 4.7) | <0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 699 (211) | 643 (181) | 0.002 | 956 (342) | 844 (288) | <0.001 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 7.1 (2.0) | 7.0 (2.0) | 0.855 | 9.8 (3.4) | 9.2 (3.0) | 0.021 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 8.6 (1.4) | 9.5 (1.9) | <0.001 | 9.5 (2.0) | 10.4 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 5.5 (3.2, 7.1) | 4.6 (2.6, 6.3) | 0.007 | 6.1 (4.8, 7.5) | 5.1 (3.5, 6.9) | <0.001 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 8.8 (7.3, 12.8) | 11.7 (8.7, 15.3) | <0.001 | 7.3 (5.7, 9.5) | 9.6 (7.2, 12.9) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | 40% | |||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 16 (12, 21) | 19 (16, 24) | <0.001 | 18 (7) | 21 (7) | <0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 40 (9) | 47 (11) | <0.001 | 43 (9) | 49 (11) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 27 (8) | 28 (7) | 0.106 | 32 (7) | 31 (6) | 0.7566 |

| PVR (WU) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) | 3.0 (1.9, 4.0) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.6, 1.7) | 2.2 (1.4, 3.5) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 8.5 (2.6) | 6.3 (2.0) | <0.001 | 9.8 (7.7, 11.9) | 7.2 (5.7, 8.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.1 (0.9) | <0.001 | 4.5 (3.8, 5.3) | 3.6 (2.8, 4.4) | <0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 708 (209) | 598 (168) | <0.001 | 968 (314) | 767 (278) | <0.001 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 7.1 (2.0) | 6.9 (2.1) | <0.001 | 9.9 (3.3) | 8.8 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 8.6 (7.8, 9.3) | 9.6 (8.4, 11.1) | <0.001 | 9.6 (2.1) | 10.3 (2.4) | 0.0017 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 5.4 (3.2, 7.1) | 4.6 (2.2, 6.0) | 0.004 | 5.9 (4.3, 7.4) | 5.4 (3.6, 6.9) | 0.013 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 8.7 (7.2, 11.8) | 13.0 (10.0, 16.7) | <0.001 | 7.4 (5.8, 9.7) | 10.4 (7.4, 13.9) | <0.001 |

| Stiff vascular | 57% | |||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 16 (12, 21) | 18 (14, 23) | 0.001 | 17 (7) | 20 (7) | 0.0010 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 38 (34, 45) | 45 (38, 52) | <0.001 | 43 (10) | 48 (10) | <0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 26 (7) | 29 (7) | <0.001 | 31 (6) | 32 (7) | 0.0079 |

| PVR (WU) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.1) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.3) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.6, 1.8) | 1.81 (1.2, 2.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 8.4 (6.8, 9.9) | 6.9 (5.4, 8.7) | <0.001 | 9.8 (7.7, 11.9) | 8.1 (6.2, 10.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.0) | <0.001 | 4.6 (3.8, 5.4) | 4.0 (3.1, 4.7) | <0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 692 (195) | 642 (191) | 0.014 | 962 (321) | 830 (298) | <0.001 |

| VO2/kg (mL/min/kg) | 7.0 (5.7, 7.9) | 6.8 (5.8, 8.2) | 0.613 | 9.9 (3.2) | 9.1 (3.2) | 0.0136 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 8.6 (1.7) | 9.2 (1.7) | 0.001 | 9.6 (2.3) | 10.1 (2.2) | 0.0221 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 4.9 (3.0, 6.8) | 5.0 (2.9, 6.7) | 0.849 | 5.8 (4.0, 7.4) | 5.6 (4.1, 7.1) | 0.464 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 9.3 (7.4, 12.8) | 11.3 (7.9, 14.9) | 0.009 | 7.4 (5.7, 10.2) | 8.9 (6.9, 12.8) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: RA, right atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; VO2, oxygen consumption; Ca-vO2, arterial-venous oxygen difference; CO, cardiac output.

At 20 W exercise, patients meeting (versus not) LA myopathy criteria displayed higher mean PA and biventricular filling pressures, higher PVR, lower CO and cardiac index, lower total oxygen consumption but similar O2 consumption relative to body weight. Compared to baseline, at 20 W, LA myopathy criteria positive (versus negative) patients had greater augmentation in Ca-vO2 overall and relative to change in change in VO2 with exercise while the change in CO relative to change in VO2 was blunted.

At 20 W exercise, patients meeting (versus not) PVD criteria had higher mean PA and right atrial but not PA wedge pressures, lower CO, and cardiac index, higher PVR, lower O2 consumption and lower O2 consumption relative to body weight (Table 4). Compared to baseline, at 20 W, PVD criteria positive (versus negative) patients had greater ability to augment Ca-vO2 overall and relative to the change in VO2 while the change in CO relative to change in VO2 was blunted.

At 20 W exercise, patients meeting (versus not) stiff vascular criteria had higher mean PA and biventricular filling pressures, higher PVR, and lower CO and cardiac index. Compared to baseline, at 20 W, stiff vascular criteria positive (versus negative) patients had higher Ca-vO2 overall and relative to the change in VO2 while the change in CO relative to change in VO2 was not different (Table 4).

At peak exercise, the same patterns and statistical significance for variables in criteria positive versus negative patients within all proposed phenogroups were observed (Table 4), with the exception of VO2 relative to weight, where no differences were seen for LA myopathy and stiff vascular criteria positive vs negative patients at 20 W, but borderline lower values were seen in criteria positive patients at peak exercise. Thus, at matched submaximal and at peak exercise, three different patterns of extraction and CO relative to O2 consumption were apparent: blunted O2 extraction but relatively preserved CO with the cardiometabolic phenogroup; greater O2 extraction but blunted CO with the LA Myopathy and PVD phenogroups and greater extraction and preserved CO with the stiff vasculature criteria.

Impact of Phenogroup Multiplicity

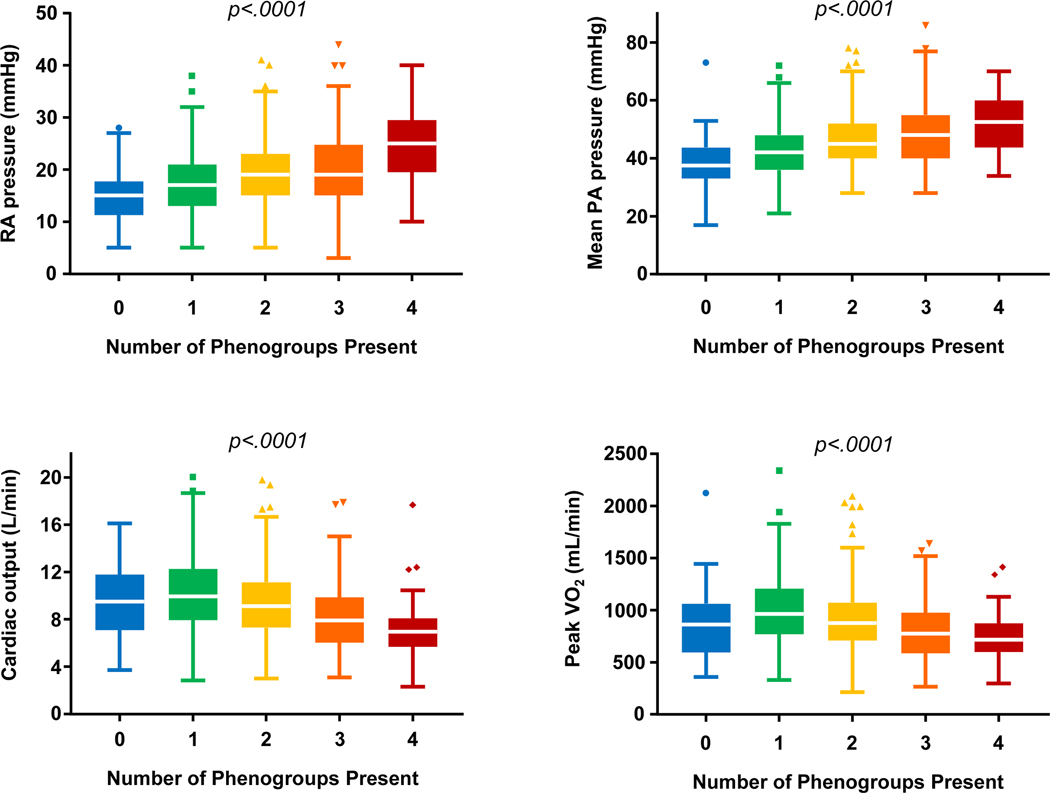

As most patients with HFpEF (67%) fulfilled criteria for more than one phenogroup, we next compared hemodynamics and exercise performance among patients based upon the number of phenogroup criteria satisfied in an individual patient (Table 5, Table S3). At rest, right and left heart filling and mean PA pressures increased, O2 consumption and CO decreased, and Ca-vO2 increased as the number of phenogroup criteria satisfied increased. These trends were also observed at 20 W (Table 5) and peak exercise (Figure 2). At 20 W and peak exercise, ΔCO/ΔVO2 decreased and Δca-vO2/ΔVO2 increased as the number of phenogroup criteria satisfied increased. (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 5:

Hemodynamics and Exercise Performance Based upon Number of Phenogroups Present.

| 0 groups (N=37) | 1 group (N=177) | 2 groups (N=212) | 3 groups (N=175) | 4 groups (N=49) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | ||||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 9 (6, 10) | 9 (7, 12) | 10 (8, 12) | 9 (7, 13) | 11 (8, 15) | 0.0103 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 22 (18, 25) | 23 (20, 28) | 26 (21, 30) | 27 (23, 35) | 35 (27, 42) | < 0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 16 (13, 17) | 16 (13, 19) | 17 (13, 20) | 16 (13, 20) | 18 (16, 23) | < 0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 234 (49) | 259 (72) | 242 (61) | 222 (57) | 221 (45) | < 0.001 |

| CO (L/min) | 5.7 (1.4) | 6.1 (1.8) | 5.6 (1.5) | 4.8 (1.3) | 4.4 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 4.3 (1.0) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.8) | 4.7 (0.9) | 5.1 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| 20 watts | ||||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 13 (10, 17) | 16 (12, 21) | 18 (14, 22) | 19 (15, 24) | 24 (20, 30) | < 0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 35 (30, 38) | 39 (34, 45) | 43 (37, 49) | 45 (38, 53) | 50 (44, 56) | < 0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 25 (21, 29) | 25 (21, 30) | 27 (23, 33) | 30 (25, 34) | 29 (25, 34) | < 0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 624 (135) | 698 (220) | 710 (190) | 616 (193) | 602 (132) | < 0.001 |

| CO (L/min) | 7.8 (2.5) | 8.4 (2.6) | 7.9 (2.5) | 7.1 (2.3) | 5.6 (1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 8.4 (2.2) | 8.6 (1.5) | 9.2 (1.6) | 9.2 (1.7) | 10.7 (2.0) | < 0.001 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 6.4 (4.7, 9.5) | 4.9 (2.9, 6.5) | 5.2 (3.2, 6.9) | 5.0 (3.1, 6.7) | 2.8 (1.3, 4.7) | 0.005 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 9.5 (7.4, 13.9) | 9.32 (7.4, 13.6) | 10.0 (7.6, 12.8) | 11.4 (7.8, 15.8) | 14.0 (11.7, 18.8) | < 0.001 |

| Peak | ||||||

| RA pressure (mmHg) | 15 (12, 18) | 17 (13, 21) | 19 (15, 23) | 19 (15, 25) | 25 (20, 29) | < 0.001 |

| Mean PA pressure (mmHg) | 38 (33, 43) | 42 (36, 48) | 45 (40, 52) | 48 (40, 55) | 53 (45, 60) | < 0.001 |

| PA wedge pressure (mmHg) | 28 (25, 31) | 30 (26, 33) | 31 (27, 35) | 31 (28, 35) | 31 (27, 35) | < 0.001 |

| VO2 (mL/min) | 858 (283) | 1004 (344) | 931 (317) | 804 (283) | 741 (222) | < 0.001 |

| CO (L/min) | 9.6 (3.0) | 10.3 (3.2) | 9.5 (3.3) | 8.2 (2.8) | 7.0 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Ca-vO2 (mL/dL) | 9.6 (3.1) | 9.9 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.2) | 10.1 (2.3) | 10.9 (2.5) | 0.010 |

| ΔCO (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 6.8 (5.7, 9.1) | 5.7 (4.2, 7.1) | 6.0 (4.0, 7.3) | 5.6 (4.2, 7.1) | 4.4 (2.7, 6.4) | 0.007 |

| ΔCa-vO2 (mL)/ ΔVO2 (mL) | 7.1 (5.7, 10.5) | 7.2 (5.7, 9.7) | 8.1 (6.5, 10.7) | 9.3 (7.0, 12.8) | 11.6 (8.6, 14.7) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: RA, right atrium; PA, pulmonary artery; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; VO2, oxygen consumption; Ca-vO2, arterial-venous oxygen difference; CO, cardiac output.

Figure 2.

Mean right atrial pressure [A], mean pulmonary artery pressure [B], cardiac output [C], and VO2 [D] at peak exercise stratified by the number of phenogroups present among HFpEF patients. As the number of phenogroups present increases, filling pressures increase further and cardiac output and VO2 decrease.

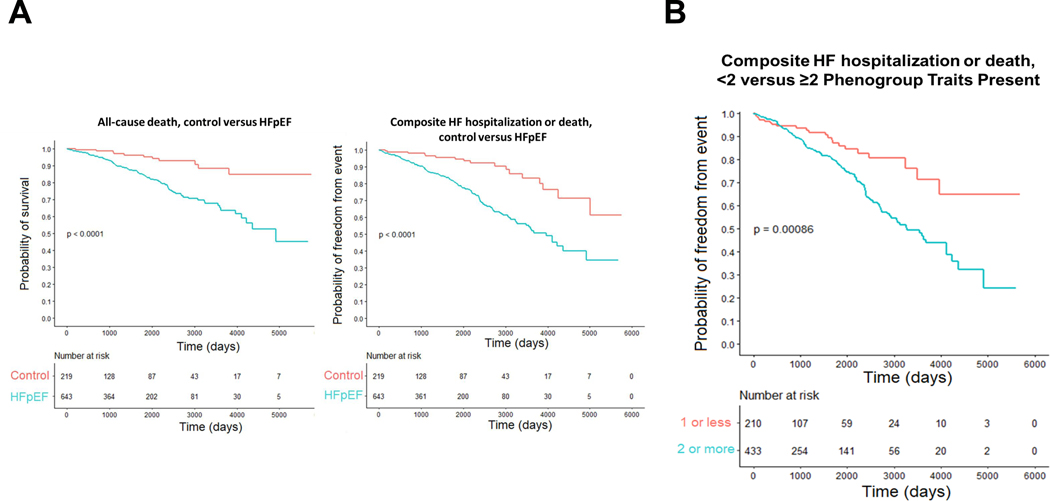

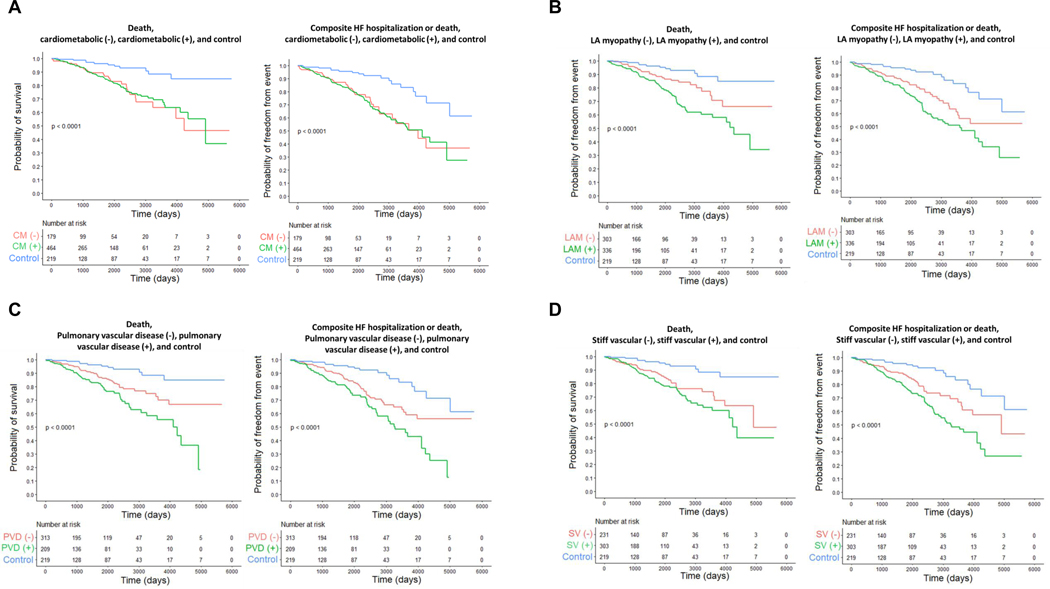

Risk for Adverse Outcome

As compared to dyspneic controls, patients with HFpEF displayed higher risk for death and the composite of HF hospitalization or death (Figure 3). Among the phenogroups, the hazard ratio of death and HF hospitalization or death was greater among those fulfilling phenogroup criteria versus controls in adjusted and unadjusted models (Table 6, Figure 4). When compared to HFpEF patients not meeting phenogroup criteria, those in the pulmonary vascular and LA myopathy phenogroups had higher risk of death, though this risk was no longer statistically insignificant when adjusting for age, sex, and BMI. Similarly, when compared to HFpEF patients not meeting phenogroup criteria, those in the pulmonary vascular, LA myopathy, and stiff vascular phenogroups had higher risk of death or HF hospitalization in an unadjusted model, but not in an adjusted model. There was additive risk of death or the composite of death or HF hospitalization for patients with increasing multiplicity of phenotypic traits: individuals belonging to two or more phenogroups had a 94% increased risk of death and 74% increased risk of heart failure hospitalization or death as compared to those fulfilling criteria for 0 or 1 phenogroups (Table 6, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of composite outcome of death, or death or heart failure hospitalization for HFpEF patients compared with controls [A], and for the composite of death or heart failure hospitalization for patients with HFpEF fulfilling criteria for <2 or ≥2 phenogroups [B]. Log-rank test comparing curves P <0.001.

Table 6:

Hazard ratios for risk of all-cause death and composite outcome from unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression models.

| All-cause death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiometabolic (CM) | Hazard Ratio, CM vs non-CM (95% CI) | P value | Hazard Ratio, CM vs control (95% CI) | P value |

| unadjusted | 0.97 (0.63, 1.50) | 0.891 | 3.65 (1.93, 6.89) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.47 (0.83, 2.59) | 0.188 | 3.04 (1.52, 6.11) | 0.002 |

| LA myopathy (LAM) | Hazard Ratio, LAM vs non-LAM (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, LAM vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.89 (1.23, 2.89) | 0.003 | 4.68 (2.47, 8.85) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.36 (0.87, 2.12) | 0.175 | 2.86 (1.46, 5.59) | 0.002 |

| Pulmonary vascular (PVD) | Hazard Ratio, PVD vs non-PVD (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, PVD vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.79 (1.19, 2.68) | 0.005 | 5.01 (2.61, 9.63) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.45 (0.94, 2.24) | 0.096 | 3.13 (1.57, 6.22) | 0.001 |

| Stiff vascular (SV) | Hazard Ratio, SV vs non-SV (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, SV vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.38 (0.91, 2.09) | 0.126 | 4.38 (2.30, 8.33) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.04 (0.68, 1.60) | 0.863 | 2.69 (1.37, 5.26) | 0.004 |

| No of groups as continuous variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| unadjusted | 1.39 (1.15, 1.68) | 0.001 | ||

| *adjusted | 1.30 (1.05, 1.60) | 0.016 | ||

| <2 vs ≥2 Phenogroup traits | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| unadjusted | 2.43 (1.41, 4.21) | 0.002 | ||

| *adjusted | 1.94 (1.09, 3.46) | 0.025 | ||

| Composite (HF hospitalization or death) | ||||

| Cardiometabolic (CM) | Hazard Ratio, CM vs non-CM (95% CI) | P value | Hazard Ratio, CM vs control (95% CI) | P value |

| unadjusted | 1.04 (0.71, 1.53) | 0.823 | 3.41 (2.04, 5.72) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.35 (0.83, 2.19) | 0.234 | 2.84 (1.60, 5.03) | <0.001 |

| LA myopathy (LAM) | Hazard Ratio, LAM vs non-LAM (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, LAM vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.57 (1.10, 2.23) | 0.013 | 4.00 (2.38, 6.74) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.23 (0.85, 1.78) | 0.278 | 2.65 (1.52, 4.61) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular (PVD) | Hazard Ratio, PVD vs non-PVD (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, PVD vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.67 (1.17, 2.39) | 0.005 | 4.19 (2.44, 7.17) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.46 (0.99, 2.14) | 0.056 | 2.85 (1.61, 5.07) | <0.001 |

| Stiff vascular (SV) | Hazard Ratio, SV vs non-SV (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio, SV vs control (95% CI) | ||

| unadjusted | 1.68 (1.15, 2.44) | 0.007 | 4.03 (2.39, 6.81) | <0.001 |

| *adjusted | 1.37 (0.93, 2.02) | 0.116 | 2.71 (1.55, 4.72) | <0.001 |

| No of groups as continuous variable | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| unadjusted | 1.28 (1.09, 1.50) | 0.003 | ||

| *adjusted | 1.19 (0.99, 1.42) | 0.058 | ||

| <2 vs ≥2 Phenogroup traits | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

| unadjusted | 2.11 (1.35, 3.30) | 0.001 | ||

| *adjusted | 1.74 (1.08, 2.79) | 0.022 | ||

Covariates included in the multivariable-adjusted Cox regression model were age, sex, and body mass index (continuous).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of death and composite outcome (death or heart failure hospitalization, for HFpEF patients fulfilling criteria for each individual phenogroup (green), HFpEF patients not fulfilling criteria that phenogroup (orange), and controls (blue); with cardiometabolic phenogroup shown in [A], left atrial (LA) myopathy in [B], pulmonary vascular disease in [C], and stiff vascular phenotype in [D]. Log-rank test comparing curves P <0.001.

Discussion

In this large cohort of consecutive patients with HFpEF undergoing invasive cardiopulmonary exercise testing, we found that individuals with HFpEF display, on average, greater elevation in biventricular filling (by definition) and pulmonary artery pressures, reduced cardiac output reserve, greater increases in Ca-vO2, poorer exercise capacity, and greater risk for HF hospitalization or death as compared to a control population of patients with non-cardiac dyspnea. However, there were notable differences in hemodynamics, O2 transport measures, and outcome based upon the type and number of phenogroup criteria fulfilled by individual patients with HFpEF (Graphical Abstract).

When comparing the clinical phenogroups at matched submaximal and at peak exercise, three different patterns of extraction and CO relative to O2 consumption were apparent (blunted extraction but preserved CO with the cardiometabolic criteria; greater extraction but blunted CO with the LA Myopathy and PVD criteria, and greater extraction and preserved CO with the stiff vasculature criteria). Only 5.6% of patients with HFpEF failed to meet criteria for any of the four phenogroups, but two-thirds of patients with HFpEF fulfilled criteria for multiple phenogroups. Patients meeting criteria for greater numbers of phenogroup traits had greater elevation in biventricular filling pressures with exercise, worsening pulmonary hypertension, a more severe impairment in cardiac output reserve relative to VO2, and greater risk for HF hospitalization or death. These findings harmonize a number of discrepant results from prior studies in the literature and highlight the pathophysiologic importance of phenotypic multiplicity and heterogeneity among the population of patients broadly defined with HFpEF, which may have important therapeutic implications.

Prior studies have evaluated the relative contributions of CO and peripheral oxygen extraction in HFpEF. Some have identified a smaller absolute Ca-vO2 or a smaller increase in Ca-vO2 from rest to exercise in patients with HFpEF as compared to healthy controls.4,10,14 However, other studies found no significant difference in Ca-vO2 difference at peak exercise among HFpEF and control patients.5,8,32 Differing results may be related in part to differing exercise intensities achieved, variability in body position, and the types of controls evaluated. For example, patients with HFpEF universally achieve a lower peak exercise workload, which will impact peak exercise findings if there is premature cessation of exercise due to dyspnea or other factors. For this reason, we included both peak exercise and comparisons at a matched external workload of 20 W. However, even matched external work may be nonequivalent, as patients with obesity-related HFpEF incur greater metabolic cost to achieve the same degree of external work,20,33 which may partly explain the apparent preservation of cardiac output reserve at 20W in this group, as demand for perfusion is greater relative to cycling work.

The present data also indicate another explanation for the variability in prior studies.4,5,8,10,14,32 If there is differing inclusion of patients fulfilling various HFpEF phenogroup definitions in different studies, there will also be differing limitations identified related to CO vs Ca-vO2, with greater deficits in the latter more apparent among studies predominantly evaluating the cardiometabolic phenotype and greater deficits in perfusion in studies dominated by patients with HFpEF and LA myopathy or PVD. This may be very important in clinical trials targeting novel therapies targeting myocardial vs peripheral abnormalities in HFpEF. Indeed, the present study suggests that phenotyping of patients with HFpEF will allow for better targeting of interventions to the mechanistic pathways of greatest pathophysiologic significance at the individual level.

Distinctive Phenogroup Characteristics

Among patients with HFpEF, those meeting (versus not) cardiometabolic criteria were younger, had higher rates of hypertension, lower NT-proBNP, and higher biventricular filling pressures, in agreement with prior studies.20,34,35 The reduction in peripheral extraction relative to VO2 at matched submaximal and peak exercise seen in the cardiometabolic criteria positive versus negative patients may be the result of local and systemic effects of adipose tissue on muscle, locoregional blood flow, or mitochondrial function.3,6 The present results in the cardiometabolic group are consistent with a recent study showing significant negative associations between ΔCa-vO2 and body fat in HFpEF.13 The cardiometabolic phenogroup also includes individuals with diabetes, a comorbid condition that has been associated with insulin resistance, increases in venous congestion, maladaptive changes in sodium handling, vascular and neurologic dysfunction,22 as well as adverse cardiac changes.23 The cardiometabolic phenogroup in the current study was unique from the other tested phenogroup criteria in the relative decrement of peripheral oxygen uptake compared to cardiometabolic criteria negative HFpEF patients, suggesting that peripheral impairments to oxygen uptake and utilization in skeletal muscle in the microvasculature are more relevant to this large phenogroup. Alternatively, increases in blood volume accompanying obesity may lead to higher cardiac output, and thus shorter transit time at the level of the capillaries, decreasing time for gas transfer, leading to higher end capillary and venous oxygen content. There were no differences in risk of HF hospitalization or death comparing individuals with or without the cardiometabolic phenotype.

Chronic diastolic dysfunction contributes to LA hypertension with LA remodeling, mechanical dysfunction, and atrial fibrillation. Concomitantly, these patients develop post-capillary pulmonary hypertension, reversible pulmonary arterial vasoconstriction and ultimately, pulmonary arterial and venous remodeling leading to right ventricular failure.36 We found that patients meeting (versus not) criteria for either LA myopathy or PVD had greater O2 extraction and lower CO reserve. This is in keeping with existing studies on the natural history of HFpEF progression, which is characterized earlier in its course by LV diastolic dysfunction followed by progressive upstream atrial dysfunction, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and subsequent right ventricular systolic dysfunction, and increasing burden of atrial fibrillation.24–26,37 Patients with the LA myopathy and PVD phenotypes both displayed greater risk of HF hospitalization or death compared to patients with HFpEF without these traits, consistent with prior studies,36,38–40 but in the fully adjusted analyses these differences were no longer statistically significant.

The stiff vascular phenogroup criteria positive (versus negative) patients had a higher proportion of women. Increases in arterial stiffness are well-described in HFpEF, particularly during exercise, and this is particularly true in women.27,41 Furthermore, differences in arterial afterload at rest are similar between HFpEF patients and patients with hypertension, but exercise unmasks impaired arterial reserve in HFpEF.24 In our study, relative to oxygen consumption, there was greater extraction but preserved CO reserve in patients meeting (versus not) stiff vasculature criteria. These findings suggest that peripheral adaptations may remain a small but viable compensatory mechanism to maintain tissue oxygen delivery in those with more severe vascular stiffening.

Phenogroup Multiplicity and Overlap

Prior studies evaluating phenogroups in various cohorts have largely used unsupervised clustering techniques, showing differences in cardiac structure, clinical outcomes, and treatment response by these clusters.15–18 One shortcoming of such approaches is the requirement to separate each patient into mutually exclusive groups, rather than embracing phenotypic overlap. Here, we examine hypothesis-driven, a priori phenogroups based upon prior pathophysiologic studies. To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study of consecutive and rigorously-evaluated patients with HFpEF to examine the distribution of underlying clinical phenogroups present in the HFpEF syndrome, with the cardiometabolic phenogroup being most common, followed by the stiff vascular and LA myopathy groups, with the pulmonary vascular disease phenogroup being least common. We further observed that most patients (67%) with HFpEF categorized in this way do not fall into one discrete phenogroup, and there is marked and inconsistent overlap between phenogroups (Figure 1). This complicates potential classification schemes given the multifaceted nature of the deficits in HFpEF if one relies on mutual exclusivity in phenogroups.

Comparison of these groups highlights the heterogeneity of exercise hemodynamic and oxygen transport responses to exercise within HFpEF. Importantly, the presence of increasing numbers of phenogroup traits among individuals was associated with more severe hemodynamic derangements, poorer exercise capacity, and greater risk for HF hospitalization or death. This emphasizes the importance of complexity and multiplicity of cardiac and noncardiac contributors to the HFpEF syndrome, in addition to differences related to specific phenotypes alone.

Limitations

This was a single-center study conducted in a referral population, introducing bias. Exercise studies were performed in the supine position, and hemodynamic responses differ in other positions as with upright exercise, so the present results may not apply in the same manner to findings with upright exertion, but all patients underwent the exact same protocol, so there is no bias. Finally, not all patients were able to exercise to a peak exercise respiratory exchange ratio >1.0. The fallout from this limitation is mitigated through the inclusion of data at matched external workloads of 20 W, and indeed, submaximal exercise may be more relevant to patient reported health status and activities of daily living.42 Increases in CO and Ca-vO2 were also normalized to increases in VO2, which adjusts for differences in oxygen transport measures that might be confounded by differing maximal workload achieved. Events of HF hospitalization were captured from the Mayo Clinic system and institutions using the Epic electronic medical record platform, which likely led to underestimates of the true event rate. However, this underdetection applies similarly to all patient groups, so there is no bias, so the estimates of risk between groups remain valid.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we report on significant variation in hemodynamics, outcome, and contributions of central and peripheral contributors to exercise intolerance in patients with HFpEF that vary across different proposed clinical phenogroups and with increasing multiplicity of phenogroup traits present. These data reinforce the importance of phenotypic characterization to distinguish patients more rigorously within the broader HFpEF spectrum but reveal the need for more optimal phenotype criteria that consider both diversity and multiplicity.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This publication was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Redfield MM & Borlaug BA Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Review. JAMA. 329, 827–838 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borlaug BA, Sharma K, Shah SJ & Ho JE Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC Scientific Statement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 81, 1810–1834 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey A, et al. Exercise Intolerance in Older Adults With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 78, 1166–1187 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haykowsky MJ, et al. Determinants of exercise intolerance in elderly heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 58, 265–274 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abudiab MM, et al. Cardiac output response to exercise in relation to metabolic demand in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 15, 776–785 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haykowsky MJ, et al. Skeletal muscle composition and its relation to exercise intolerance in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 113, 1211–1216 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos M, et al. Central cardiac limit to aerobic capacity in patients with exertional pulmonary venous hypertension: implications for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 8, 278–285 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V. & Olson TP Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 37, 3293–3302 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obokata M, et al. Haemodynamics, dyspnoea, and pulmonary reserve in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 39, 2810–2821 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houstis NE, et al. Exercise Intolerance in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Diagnosing and Ranking Its Causes Using Personalized O2 Pathway Analysis. Circulation. 137, 148–161 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy YNV, Olson TP, Obokata M, Melenovsky V. & Borlaug BA Hemodynamic Correlates and Diagnostic Role of Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 6, 665–675 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhella PS, et al. Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 13, 1296–1304 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zamani P, et al. Peripheral Determinants of Oxygen Utilization in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Central Role of Adiposity. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 5, 211–225 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhakal BP, et al. Mechanisms of Exercise Intolerance in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: The Role of Abnormal Peripheral Oxygen Extraction. Circ Heart Fail. 8, 286–294 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah SJ, et al. Phenomapping for novel classification of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 131, 269–279 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JB, et al. Clinical Phenogroups in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Detailed Phenotypes, Prognosis, and Response to Spironolactone. JACC Heart Fail. 8, 172–184 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segar MW, et al. Phenomapping of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction using machine learning-based unsupervised cluster analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 22, 148–158 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabbah MS, et al. Obese-Inflammatory Phenotypes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 13, e006414 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorimachi H, Omote K. & Borlaug BA Clinical Phenogroups in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart Fail Clin. 17, 483–498 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obokata M, Reddy YN, Pislaru SV, Melenovsky V. & Borlaug BA Evidence Supporting the Existence of a Distinct Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 136, 6–19 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borlaug BA, et al. Obesity and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: new insights and pathophysiological targets. Cardiovasc Res. 118, 3434–3450 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindman BR, et al. Cardiovascular phenotype in HFpEF patients with or without diabetes: a RELAX trial ancillary study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 64, 541–549 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chirinos JA, et al. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Ventricular Structure, Arterial Stiffness, and Pulsatile Hemodynamics in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 8, e011457 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel RB & Shah SJ Therapeutic Targeting of Left Atrial Myopathy in Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Verbrugge FH, Lin G. & Borlaug BA Atrial Dysfunction in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 76, 1051–1064 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omote K, et al. Pulmonary vascular disease in pulmonary hypertension due to left heart disease: pathophysiologic implications. Eur Heart J. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy YNV, et al. Arterial Stiffening With Exercise in Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 70, 136–148 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chirinos JA, Segers P, Hughes T. & Townsend R. Large-Artery Stiffness in Health and Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 74, 1237–1263 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pieske B, et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 40, 3297–3317 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Humbert M, et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J. 43, 3618–3731 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang RM, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 28, 1–39 e14 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR, Sheikh KH & Sullivan MJ Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function: failure of the Frank-Starling mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 17, 1065–1072 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah RV, et al. Metabolic Cost of Exercise Initiation in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction vs Community-Dwelling Adults. JAMA Cardiol. 6, 653–660 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy YNV, et al. Characterization of the Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A RELAX Trial Ancillary Study. Mayo Clin Proc 94, 1199–1209 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tromp J, et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in the Young. Circulation. 138, 2763–2773 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melenovsky V, et al. Left atrial remodeling and function in advanced heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 8, 295–303 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, Pislaru S. & Borlaug BA Deterioration in right ventricular structure and function over time in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 40, 689–697 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freed BH, et al. Prognostic Utility and Clinical Significance of Cardiac Mechanics in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Importance of Left Atrial Strain. Circ Cardiovasc Imag. 9(2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vanderpool RR, Saul M, Nouraie M, Gladwin MT & Simon MA Association Between Hemodynamic Markers of Pulmonary Hypertension and Outcomes in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Omote K, et al. Central Hemodynamic Abnormalities and Outcome in Patients with Unexplained Dyspnea. Eur J Heart Fail. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lau ES, et al. Arterial Stiffness and Vascular Load in HFpEF: Differences Among Women and Men. J Card Fail. 28, 202–211 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy YNV, et al. Quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: importance of obesity, functional capacity, and physical inactivity. Eur J Heart Fail. 22, 1009–1018 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.