Abstract

Objective

To define the clinical, histopathological features and the prognostic factors affecting survival in patients with adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary (AGCT).

Methods

A 322 patients whose final pathologic outcome was AGCT treated at nine tertiary oncology centers between 1988 and 2021 participated in the study.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 51.3±11.8 years and ranged from 21 to 82 years. According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2014, 250 (77.6%) patients were stage I, 24 (7.5%) patients were stage II, 20 (6.2%) patients were stage III, and 3 (7.8%) were stage IV. Lymphadenectomy was added to the surgical procedure in 210 (65.2%) patients. Lymph node involvement was noted in seven (3.3%) patients. Peritoneal cytology was positive in 19 (5.9%) patients, and 13 (4%) had metastases in the omentum. Of 285 patients who underwent hysterectomy, 19 (6.7%) had complex hyperplasia with atypia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia, and 8 (2.8%) had grade 1 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. It was found that 93 (28.9%) patients in the study group received adjuvant treatment. Bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin was the most commonly used chemotherapy protocol. The median follow-up time of the study group was 41 months (range, 1–276 months). It was noted that 34 (10.6%) patients relapsed during this period, and 9 (2.8%) patients died because of the disease. The entire cohort had a 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) of 86% and a 5-year disease-specific survival of 98%. Recurrences were observed only in the pelvis in 13 patients and the extra-abdominal region in 7 patients. The recurrence rate increased 6.168-fold in patients with positive peritoneal cytology (95% confidence interval [CI]=1.914–19.878; p=0.002), 3.755-fold in stage II–IV (95% CI=1.275–11.063; p=0.016), and 2.517-fold in postmenopausal women (95% CI=1.017–6.233; p=0.046) increased.

Conclusion

In this study, lymph node involvement was detected in 3.3% of patients with AGCT. Therefore, it was concluded that lymphadenectomy can be avoided in primary surgical treatment. Positive peritoneal cytology, stage, and menopausal status were independent prognostic predictors of DFS.

Keywords: Granulosa Cell, Disease-Free Survival, Prognostic Factors, Ovarian Carcinoma

Synopsis

Lymph node involvement is rare in patients with adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary, so lymphadenectomy can be avoided in primary surgical management. Positivity of peritoneal cytology, stage, and menopausal status are found to be independent prognostic predictor of disease-free survival.

INTRODUCTION

Adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary (AGCT) are rare and account for approximately 2%–5% of all ovarian malignancies [1,2]. AGCT is the most common type among malignant ovarian sex cord tumors, accounting for 90% of cases [3]. Although they can occur throughout life, they are usually diagnosed in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women between 50 and 55 [2,4].

AGCTs are ovarian tumors that can secrete hormones, especially estrogen. The hyperestrogenism observed in these cases results from the tumor's production of estrogens, anti-Mullerian hormone, and inhibin B [5]. Due to the hormonal effects, endometrial pathologies such as endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer may occur. These pathologies lead to abnormal uterine bleeding, the most important clinical finding. In addition, abdominal pain and distension are other critical clinical findings in these patients [6,7]. The most sensitive and specific serum tumor marker for diagnosing granulosa cell tumors is inhibin, produced in the ovaries in response to follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone [8].

Surgical excision is the basis of histologic diagnosis and initial treatment aimed at appropriate staging [9,10]. The surgical approach to AGCT includes the same principles traditionally recommended for epithelial ovarian tumors [10]. Complete surgical excision of the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, along with staging procedures (peritoneal cytology, biopsies, and infracolic omentectomy), is the gold standard [11]. Since only 2% of AGCTs are bilateral, the preferred surgical approach in women of reproductive age is unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and staging [12,13]. The incidence of nodal involvement in AGCT is very low. For this reason, the need for lymph node dissection is still debated [14,15].

Most granulosa cell tumors have a slow growth pattern and are diagnosed at stage I. Also, they have quite a good prognosis. For these reasons, they are considered low-grade malignancies [16,17]. The early stage's 5-, 10-, and 20-year survival rates were reported as 94, 82, and 62 percent, respectively [18]. However, they have metastatic potential and tend to relapse late. The median duration of recurrence is five years after surgical treatment of the primary tumor. Recurrences can occur even in early-stage disease that has been followed for decades. Moreover, many relapses have been reported 20–40 years after initial diagnosis [19,20,21,22]. Therefore, long-term follow-up is necessary [2,6,7,9]. The stage at diagnosis, the status of postoperative residual disease, and tumor size have been reported as significant prognostic factors [7,23,24].

However, despite all treatment options, these tumors still have recurrences. Because of these recurrences, AGCTs remain a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in women's lives. Given all this information, the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with AGCT, the prognostic factors for surgical management, adjuvant treatment, and recurrence of AGCT still need to be fully elucidated. So, we aimed to define the clinical and histopathological features of AGCT and the prognostic factors affecting survival in the Turkish population with the results of a total of 34 years of experience from 9 tertiary oncology centers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study design

The study enrolled 322 patients whose final pathologic outcome was AGCT at nine tertiary oncology centers between 1988 and 2021. Approval was obtained from the local ethics committee for the study. Patients not followed up after surgery, had concurrent non-gynecologic malignancies, had received prior radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and had ovarian tumors other than AGCT were excluded from the study.

Clinical, demographic, and histopathologic information on included patients was obtained from patient registries, pathology reports, and electronic databases. Treatments for those who underwent surgery at a center other than gynecologic oncology and were referred because they were AGCT were evaluated and regulated by the gynecologic oncology council of the respective hospital.

2. Definitions

The surgical procedure in which no hysterectomy is performed, and at least part of one ovary is left in place was defined as “conservative surgery”, and the surgical procedure in which at least hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is performed was defined as “definitive surgery”. The senior surgeon decided whether to include omentectomy and lymphadenectomy in the surgical procedure and whether to perform lymphadenectomy thoroughly or sampling.

In all clinics, surgical specimens are evaluated by experienced gynecopathologists. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2014 system was used for staging [25]. Those operated on before 2014 were restaged according to the pathology report using the 2014 FIGO criteria.

Depending on the final pathology result, the decision on adjuvant treatment is made by the Gynecologic Oncology Council. After surgery and adjuvant treatment, patients were enrolled in the routine surveillance program. They were examined every three months for the first two years, then every six months until the 5th year, and then once a year, with pelvic examination, abdominal ultrasonography, complete blood count, and biochemical blood tests. If clinically suspected, a chest radiograph was performed. Thoracic or abdominal computed tomography was performed if needed. Postoperative patients were not routinely followed up with computed tomography. However, computed tomography was performed when recurrence was suspected; symptoms were present, a suspicious lesion was detected on control ultrasound, or abnormal tumor marker results were present. Recurrence below the linea terminalis was defined as pelvic recurrence, recurrence between the linea terminalis and diaphragm as upper abdominal recurrence, and recurrence outside of it as extra-abdominal recurrence. Recurrences in the liver parenchyma, and bone were considered extra abdominal recurrences, cytologically defined ascites, and upper abdominal recurrences to peritonitis carcinomatosis.

Time from first surgical intervention to recurrence of disease or to last contact was defined as disease-free survival (DFS), and time to death from disease or to last contact was defined as disease-specific survival (DSS).

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of the data was determined by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The continuous data's mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values were calculated using the descriptive statistical test. The numbers and percentages of the categorical variables were calculated using the chi-square test. DFS and DSS were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Multivariate analysis was performed with a Cox proportional hazards model, and a multivariate analysis model was constructed with variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The mean age of the 322 patients included in the study was 51.3±11.8 years, ranging from 21 to 82 years. One hundred and sixty-three (50.6%) of the patients were postmenopausal. According to FIGO 2014, 250 (77.6%) patients were stage I, 24 (7.5%) patients were stage II, 20 (6.2%) patients were stage III, and 3 (7.8%) were stage IV. It was found that 220 (68.3%) patients had their first surgery in gynecologic oncology clinics, the cyst was not ruptured in 255 (79.2%) patients at the first surgery, and conservative surgery was performed in 35 (10.9%) patients. Lymphadenectomy was added to the surgical procedure in 210 (65.2%) patients, and in 197 of them, lymphadenectomy was performed as pelvic+paraaortic lymphadenectomy. In patients with lymphadenectomy, a median of 38 lymph nodes were removed (range, 2–129). Lymph node involvement was noted in seven (3.3%) patients. Omentectomy was performed in 238 (73.9%) patients, and 13 (4%) had metastases in the omentum. Ascites were present in 55 (17.1%) patients, and the median ascites volume was 100 mL (range, 20–10,000 mL). Peritoneal cytology was positive in 19 (5.9%) patients. The demographic, surgical, and pathologic characteristics of the entire study group are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical, surgical and pathological features of entire cohort.

| Characteristics | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at initial diagnosis (yr) | ||

| Mean±SD | 51.3±11.8 | |

| Median (range) | 51 (21–82) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | ||

| Mean±SD | 111.6±90.1 | |

| Median (range) | 85 (7–900) | |

| Preoperative CA 125 (IU/mL) | ||

| Mean±SD | 73.6±148.8 | |

| Median (range) | 25 (1–995) | |

| Total removed lymph node count | ||

| Mean±SD | 40.5±24.5 | |

| Median (range) | 38 (2–129) | |

| Ascites (mL) | ||

| Mean±SD | 721±1,738 | |

| Median (range) | 100 (20–10,000) | |

| FIGO stage | ||

| I | 250 (77.6) | |

| II | 24 (7.5) | |

| III | 20 (6.2) | |

| IV | 3 (0.9) | |

| Unidentified | 25 (7.8) | |

| Menopausal status | ||

| Premenopause | 157 (48.8) | |

| Postmenopause | 163 (50.6) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.6) | |

| First operation clinic | ||

| Gynecologic oncology | 220 (68.3) | |

| Other | 96 (29.8) | |

| Not reported | 6 (1.9) | |

| Rupture of cyst | ||

| Unruptured | 255 (79.2) | |

| Iatrogenic rupture | 31 (9.6) | |

| Presurgical rupture | 13 (4.0) | |

| Not reported | 23 (7.1) | |

| Hysterectomy | ||

| Performed | 285 (88.5) | |

| Not performed* | 35 (10.9) | |

| Hysterectomy performed before disease | 2 (0.6) | |

| Ovarian tumor site | ||

| Left | 150 (46.6) | |

| Right | 128 (39.8) | |

| Bilateral | 27 (8.4) | |

| Not reported | 17 (5.3) | |

| Lymphadenectomy | ||

| Performed | 210 (65.2) | |

| Not performed | 111 (34.5) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.3) | |

| Type of lymphadenectomy† | ||

| Only pelvic | 10 (4.8) | |

| Only paraaortic | 3 (1.4) | |

| Pelvic and paraaortic | 197 (93.8) | |

| Lymph node metastasis† | ||

| Negative | 203 (96.7) | |

| Positive | 7 (3.3) | |

| Omentectomy | ||

| Performed | 238 (73.9) | |

| Not performed | 83 (25.8) | |

| Not reported | 1 (0.3) | |

| Omental metastasis‡ | ||

| Negative | 225 (94.5) | |

| Positive | 13 (4.0) | |

| Ascites | ||

| Absent | 219 (68) | |

| Present | 55 (17.1) | |

| Not reported | 48 (14.9) | |

| Peritoneal cytology | ||

| Negative | 235 (73.0) | |

| Positive | 19 (5.9) | |

| Not reported | 68 (21.1) | |

Values are presented as number (%) not otherwise specified.

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SD, standard deviation.

*Conservative surgery; †210 patients; ‡238 patients.

While only 30 (9.3%) patients were asymptomatic at admission, abnormal uterine bleeding (postmenopausal bleeding and menstrual irregularity) was the most common finding. It was found that 139 (43.1%) patients had symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding (Table 2).

Table 2. Symptoms and endometrial pathology.

| Features | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Main symptom | ||

| No symptom | 30 (9.3) | |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | 79 (24.5) | |

| Abdominal distention | 69 (21.4) | |

| Abdominal or suprapubic pain | 63 (19.6) | |

| Menstrual irregularity | 60 (18.6) | |

| Not reported | 21 (6.5) | |

| Endometrial pathology on hysterectomy specimen* | ||

| Atrophic endometrium | 24 (8.4) | |

| Endometritis | 6 (2.1) | |

| Endometrial polyp | 10 (3.5) | |

| Proliferative endometrium | 108 (37.9) | |

| Secretuary endometrium | 20 (7.0) | |

| Simple hyperplasia without atypia | 48 (16.8) | |

| Complex hyperplasia without atypia | 9 (3.2) | |

| Complex hyperplasia with atypia/EIN | 19 (6.7) | |

| Endometrioid cancer grade 1 | 8 (2.8) | |

| Not reported | 33 (11.6) | |

| Endometrial pathology on endometrial sampling† | ||

| Atrophic endometrium | 2 (5.7) | |

| Endometritis | 7 (20.0) | |

| Endometrial polyp | 1 (2.9) | |

| Proliferative endometrium | 1 (2.9) | |

| Simple hyperplasia without atypia | 2 (5.7) | |

| Not performed | 22 (62.9) | |

Values are presented as number (%).

*n=285; The patients underwent hysterectomy because of adult granulosa cell tumor (definitive surgery); †n=35; The result of endometrial sampling in patients didn’t underwent hysterectomy (conservative surgery).

Four of the seven patients who underwent lymph node dissection were premenopausal, and three were postmenopausal. Definitive surgery was performed on all patients. Peritoneal cytology was negative in six patients, and no peritoneal cytology information was provided for one patient. According to the FIGO 2014 staging system, four patients were stage IIIC, one was stage IVB, and two provided no stage information. Only one patient had positive omental metastasis. While only one patient received external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), the other six underwent bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy. While no recurrence was detected in four patients after primary surgery and adjuvant treatment, recurrence was detected in three during follow-up. The recurrences were located in the lung in one patient, the pelvis in one patient, and the rectus sheath in one patient. During follow-up, one of the patients died from the disease. The median duration of DFS was 37.2 months and ranged from 1 to 108 months. The median overall survival was 52.5 months, ranging from 1 to 108 months (Table 3).

Table 3. Patients with lymph node involvement (n=7).

| Characteristics | 1. Patient | 2. Patient | 3. Patient* | 4. Patient | 5. Patient | 6. Patient | 7. Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 42 | 46 | 28 | 70 | 48 | 48 | 39 |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal | Premenopausal | Premenopausal | Postmenopausal | Postmenopausal | Postmenopausal | Premenopausal |

| Surgery type | Definitive | Definitive | Definitive | Definitive | Definitive | Definitive | Definitive |

| Tumor size (mm) | 200 | NR | 120 | 75 | 60 | 55 | 100 |

| Number of removed lymph node | 35 | 63 | 37 | 41 | 33 | 39 | 24 |

| Peritoneal cytology | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | NR | Negative | Negative |

| FIGO stage | IIIC | IIIC | IVB | NR | IIIC | IIIC | NR |

| Omental metastasis | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Adjuvant therapy | BEP | BEP | BEP | BEP | EBRT | BEP | BEP |

| Recurrence | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative |

| First recurrence site | - | - | - | Pulmoner | Pelvic | Rectus sheath | - |

| DFS (mo) | 35 | 35 | 1* | 10 | 36 | 36 | 108 |

| Exitus because of disease | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| OS (mo) | 35 | 35 | 1 | 21 | 96 | 72 | 108 |

BEP, bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin; DFS, disease-free survival; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival.

*Unfollowed patient.

Of 285 patients who underwent hysterectomy, 19 (6.7%) had complex hyperplasia with atypia/endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia, and 8 (2.8%) had grade 1 endometrioid endometrial carcinoma (Table 2). While one of eight patients defined as having endometrioid carcinoma had no myometrial invasion, six had myometrial invasion depth <1/2, and one had myometrial invasion depth ≥1/2. It was noted that 13 of 35 patients who underwent conservative surgery had endometrial sampling. Endometrial sampling results in these 13 patients were reported as atrophic endometrium, endometrial polyp, endometritis, proliferative endometrium, and simple hyperplasia without atypia (Table 2).

1. Adjuvant treatment

It was found that 93 (28.9%) patients in the study group received adjuvant treatment. Adjuvant treatment was chemotherapy only in 85 of them, radiotherapy only in 3, and chemotherapy and radiotherapy in 2. In addition, detailed records of adjuvant treatment could not be obtained for three patients. The most commonly used chemotherapy protocol was BEP (Table 4). Radiotherapy was delivered as EBRT in 5 patients.

Table 4. Features of the adjuvant treatment.

| Features | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Adjuvant treatment | ||

| Not received | 229 (71.1) | |

| Received | 93 (28.9) | |

| Type of adjuvant treatment* | ||

| Only CT | 85 (91.4) | |

| Only RT‡ | 3 (3.2) | |

| CT plus RT‡ | 2 (2.2) | |

| Unidentified | 3 (3.2) | |

| Chemotherapy protocol† | ||

| BEP | 33 (37.9) | |

| CFP | 17 (19.5) | |

| CP | 11 (12.6) | |

| VAC | 8 (9.2) | |

| EP | 2 (2.3) | |

| CE | 1 (1.2) | |

| CAP | 2 (2.3) | |

| Paclitaxel plus CbP | 8 (9.2) | |

| Paclitaxel plus Cis | 3 (3.5) | |

| Not reported | 2 (2.3) | |

Values are presented as number (%) not otherwise specified.

BEP, bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin; CAP, cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, cisplatin; CbP, carboplatin; CE, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; CFP, cyclophosphamide, farmarubicin, prednisone; Cis, cisplatin; CP, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin; CT, chemotherapy; EP, etoposide, cisplatin; RT, radiotherapy; VAC, vincristine, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide.

*93 patients; †87 patients (85 patients received only chemotherapy and 2 patients received chemotherapy plus radiotherapy); ‡External beam radiotherapy.

The mean age of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy was 50.4±10.95 years and ranged from 24 to 82 years. The mean age of patients who received adjuvant radiotherapy was 50.3±12.42 years and ranged from 36 to 58 years. The mean age of patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy + radiotherapy was 53.5±23.33 years and ranged from 37 to 70 years.

According to FIGO 2014, 39 (45.9%) patients who received adjuvant therapy were stage I, 13 (15.3%) patients were stage II, 18 (21.2%) patients were stage III, and 3 (3.5%) patients were stage IV. In addition, detailed records of the stage who received adjuvant therapy could not be obtained for 12 (14.1%) patients.

Hysterectomy was performed in 78 (91.8%) patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy. In addition, hysterectomy was not performed in 6 (7.1%) patients, and hysterectomy was performed in 1 (1.2%) patient before AGCT was diagnosed (Table S1).

All eight patients with concurrent endometrial cancer were grade 1. Seven are stage IA, and one of them is stage IB. Two of these patients received adjuvant therapy. One of the patients with stage IA endometrial cancer received chemotherapy for AGCT, and the patient with stage IB received radiotherapy for endometrial cancer and chemotherapy for AGCT.

2. Recurrence and survival

The median follow-up time of the study group was 41 months (range, 1–276 months). It was noted that 34 (10.6%) patients relapsed during this period, and 9 (2.8%) patients died because of the disease.

The symptoms of the 34 patients who experienced recurrence were as follows: The most common symptom was abdominal/pelvic pain at 55.8% (n=19), followed by asymptomatic patients at 29.4% (n=10). The remaining patients (14.7%, n=5) had abdominal distension.

The entire cohort had a 5-year DFS of 86% and a 5-year DSS of 98%. Recurrences were observed only in the pelvis in 13 patients and the extra-abdominal region in 7 patients. The recurrence pattern is shown in Table S2.

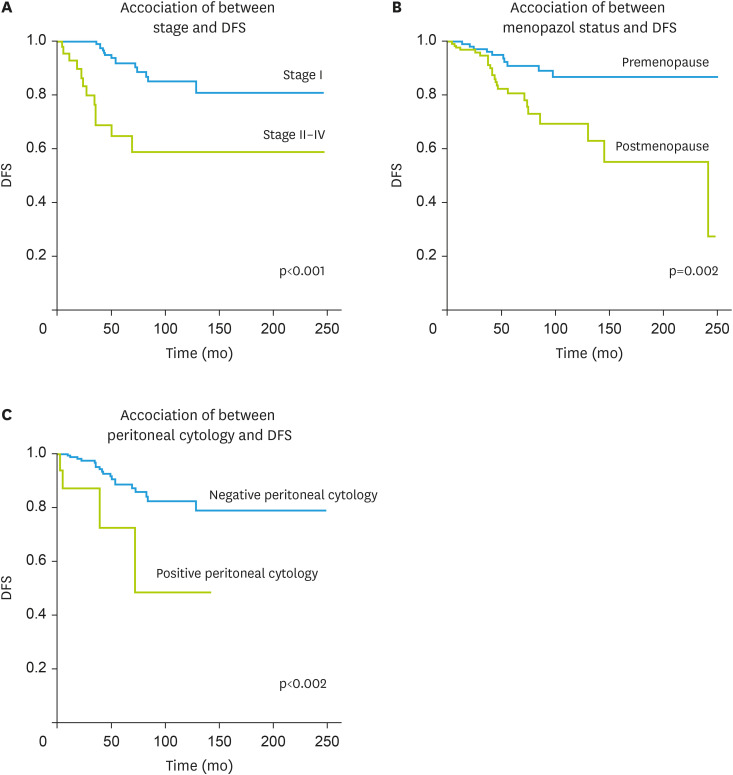

Age, peritoneal cytology, menopausal status, stage, and cyst rupture (iatrogenic or preoperative) were significant for DFS in univariate analysis. In contrast, the original surgical center, tumor size, presence of ascites, conservative surgery, lymphadenectomy, and omentectomy as part of the surgical procedure, and adjuvant treatment were not associated with DFS (Table 5). Because age and menopausal status were highly correlated among factors found to be significant in univariate analysis, excluding age at diagnosis, a model was created for multivariate analysis that accounted for peritoneal cytology (negative vs. positive), stage (I vs. II–IV), menopausal status (premenopausal vs. postmenopausal), and cyst rupture (unruptured vs. ruptured) (Fig. 1). The recurrence rate increased 6.168-fold in patients with positive peritoneal cytology (95% CI=1.914–19.878; p=0.002), 3.755-fold in stage II–IV (95% CI=1.275–11.063; p=0.016), and 2.517-fold in postmenopausal women (95% CI=1.017–6.233; p=0.046) increased. Statistical analysis could not be performed for DSS due to insufficient numbers of disease-related deaths.

Table 5. Factors related with DFS.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-yr DFS | Recurrence | ||||

| % | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Age at initial diagnosis* | 0.043 | ||||

| ≤51 yr | 88 | ||||

| >51 yr | 84 | ||||

| Peritoneal cytology | 0.002 | 0.002 | |||

| Negative | 89 | 1 (Reference) | |||

| Positive | 73 | 6.168 (1.914–19.878) | |||

| Stage | <0.001 | 0.016 | |||

| I | 92 | 1 (Reference) | |||

| II–IV | 65 | 3.755 (1.275–11.063) | |||

| Menopausal status | 0.002 | 0.046 | |||

| Premenopause | 91 | 1 (Reference) | |||

| Postmenopause | 81 | 2.517 (1.017–6.233) | |||

| Rupture of cyst | 0.007 | 0.199 | |||

| Unruptured | 89 | 1 (Reference) | |||

| Ruptured† | 76 | 2.198 (0.661–7.301) | |||

| First operation clinic | 0.390 | ||||

| Gynecologic oncology | 89 | ||||

| Other | 82 | ||||

| Ovarian tumor size* | 0.610 | ||||

| ≤85 mm | 81 | ||||

| >85 mm | 91 | ||||

| Ascites | 0.978 | ||||

| Absent | 89 | ||||

| Present | 88 | ||||

| Surgery type | 0.128 | ||||

| Definitive surgery‡ | 85 | ||||

| Conservative surgery | 100 | ||||

| Lymphadenectomy | 0.992 | ||||

| Performed | 87 | ||||

| Not performed | 84 | ||||

| Omentectomy | 0.944 | ||||

| Performed | 87 | ||||

| Not performed | 86 | ||||

| Adjuvant treatment | 0.273 | ||||

| Not received | 90 | ||||

| Received | 79 | ||||

CI, confidence interval; DFS, disease-free survival; OR, odds ratio.

*Median value; †Iatrogenic or presurgical rupture; ‡287 patients (285 patients performed because of adult granulosa cell tumor and 2 patients had underwent hysterectomy before adult granulosa cell tumor).

Fig. 1. Association of between stage, menopazol status, peritoneal cytology and DFS.

DFS, disease-free survival.

It was found that two of eight patients whose endometrial pathology was defined as grade 1 endometrioid carcinoma received adjuvant treatment. The adjuvant treatment was chemotherapy in one of them and chemotherapy plus EBRT in the other. The depth of myometrial invasion was ≥1/2 in the patient who underwent radiotherapy, and of these eight patients, recurrence occurred only in the patient who received adjuvant radiotherapy, ten months after treatment in the lung. Despite salvage treatment, this patient died at month 21 because of disease progression.

DISCUSSION

AGCTs have a low malignant potential. Therefore, their prognosis is much better than epithelial ovarian carcinomas. However, despite all treatment options, these tumors still have recurrences. Because of these recurrences, AGCTs remain a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in women's lives. Therefore, there is a need to clarify the clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with AGCT and the prognostic factors that may be associated with recurrence. In light of this information, 322 AGCT patients were studied in detail in this large multicenter retrospective study.

One of the essential features of AGCT tumors is the endometrial pathologies that occur due to the estrogen they secrete. A study examining 150 patients with primary adult AGCT found that 29.2% had hyperplasia and 7.5% had endometrial carcinoma. The same study highlighted that almost all patients with endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer were over 40. For this reason, it was indicated that endometrial sampling should be performed in AGCT patients over 40 years of age [26]. In another study evaluating 1,031 cases with AGCT, it was found that 58 patients (5.9%) had concurrent endometrial carcinoma, 251 patients (25.5%) had endometrial hyperplasia, 89 patients (9.1%) had complex hyperplasia, and 162 patients (16.5%) had simple hyperplasia. In this study, almost all (96.6%) patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer were older than 45. Also, they found that most of the diagnosed endometrial cancers were low-grade, endometrioid type, and early-stage [27]. In another study presented by Lee et al., [28] examining 68 patients with AGCT, 26.4% of the included patients had endometrial pathology. Among the endometrial pathologies detected, 14% were simple hyperplasia without atypia, 1.4% were simple hyperplasia with atypia, 2.9% were complex hyperplasia without atypia, 4.4% were complex hyperplasia with atypia, and 2.9% were endometrial cancer [28]. Pathologic examination of the hysterectomy material in our study revealed simple hyperplasia without atypia in 48 (16.8%) patients, complex hyperplasia without atypia in 9 (3.2%) patients, complex hyperplasia with atypia/ EIN in 19 (6.7%) patients, and grade 1 endometrial cancer in 8 (2.8%) patients. These findings are consistent with the results of studies published in the literature and demonstrate the importance of endometrial examination in patients scheduled for fertility-preserving surgery due to AGCT.

Whether lymph node dissection should be added to the standard surgical treatment of AGCTs remains controversial. Kuru et al., [29] examining 151 patients with AGCT, found that pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection was performed in 134 patients. Only 6 (4.5%) patients had lymph node metastases [29]. Another study by Ayhan et al. [30] found that only 1 of 18 patients who underwent lymphadenectomy had lymph node metastases. In another study by Erkılınç et al., [31] lymph node dissection was performed in 53 of 98 patients, and lymph node metastasis was found to be 3.1%. The same study highlighted that lymph node dissection did not affect survival [31]. In our study, lymph node metastases were found in 7 (3.3%) patients, similar to the literature. Studies have shown that lymph node metastases occur, especially in recurrent disease [32]. Abu-Rustum et al. [14] found that lymph node metastasis was 15% in patients with AGCT who had the first recurrence. Brown et al. [15] reported that 6 of 117 (5%) patients with recurrent ovarian tumors had lymph node metastasis. These results suggest that the status of retroperitoneal lymph nodes should be investigated in patients with recurrent AGCT and that lymphadenectomy should be performed in patients with only bulky lymph nodes.

Forty-five patients were analyzed in a study describing surgical and clinical outcomes and spread pathways in the primary and recurrent setting of the disease. Significantly different tumor spread patterns were noted between primary and recurrent patients, with the latter having a significantly higher rate of diffuse peritoneal involvement and extraovarian tumor involvement of the mid-and upper abdomen [33]. A retrospective review of patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumors revealed that 34 patients with recurrent granulosa cell tumors were treated during the study; 31 (91%) had AGCT, and 3 had juvenile histology. The location of the first recurrence included pelvis (70%), pelvis and abdomen (9%), retroperitoneum only (6%), pelvis and retroperitoneum (6%), pelvis/abdomen/retroperitoneum (3%), abdomen only (3%), and bone (3%) [14]. In another study to determine prognostic predictors and patterns of spread in AGCT, the rates of definitive retroperitoneal lymph node metastases at baseline and recurrence were found to be 5.1% (3/58) and 21.4% (3/14), respectively. In the same study, the disease was found to recur in 18 (16.6%) patients, and 8 (7.4%) patients died from the disease. The first sites of recurrence were the pelvic peritoneum in 10 patients, the liver/liver capsule in 5 patients, the rectosigmoid colon in 4 patients, the retroperitoneal lymph nodes in 3 patients, the omentum in 3 patients, the small bowel mesentery in 2 patients, and the vaginal cuff region in 2 patients. Multisite recurrence was observed in 9 (50%) patients. The 5- and 10-year survival rates were 93.3% and 90.9%, respectively. Both stage and residual tumor status were significantly associated with recurrence in univariate and multivariate analyses [34]. According to Mangili et al., [35] 97 AGCTs were evaluated in a study, and 33 patients were found to have recurrence with a median follow-up of 88 months. It was found that 47% of these recurrences occurred five years after the initial diagnosis. The same study highlighted that although the 5-year survival rate was 97%, the 20-year survival rate decreased to 66.8%. In multivariate regression analysis, age and stage were found to be independent poor prognostic factors for survival [35]. Karalok et al. [36] found that menopausal status, advanced age, cyst rupture, poorly differentiated tumor, and advanced stage were associated with recurrence in patients with AGCT. The stage was the only independent prognostic factor for the development of recurrence [36]. In another study by Sun et al., [37] the prognosis was found to be related to the initial stage, the presence of residual tumor after initial surgery, and tumor size (>13.5 cm). In our study, 13 (4%) patients had omental metastases, and 19 (5.9%) patients had positive peritoneal cytology. During the follow-up period, recurrence was observed in 34 patients. Recurrences occurred in the pelvis in 13 (38.2%) patients, in the extra-abdominal region only in 4 (11.8%) patients, and in the upper abdomen only in 4 (11.8%) patients. The positivity of peritoneal cytology, stage, and menopausal status were independent predictive parameters in univariate and multivariate regression analysis.

The efficacy of adjuvant treatment for women with advanced and recurrent AGCT remains poorly established. The National Cancer Database analysis of 2,680 women with AGCT revealed no evidence of prolonged survival with adjuvant chemotherapy. Early and complete surgical resection remains the best-evidenced treatment for AGCT [38]. However, Park et al. [5] concluded that optimal debulking followed by six cycles of BEP chemotherapy is recommended for advanced-stage GCT. There are insufficient data on the efficacy of radiotherapy in adjuvant therapy. In a previous study, a total of 103 patients with histologically confirmed AGCT were studied; Hauspy et al. [39] showed that the median DFS was 251 months in patients who underwent adjuvant radiotherapy compared with 112 months in patients who did not receive adjuvant radiotherapy. On multivariate analysis, adjuvant radiotherapy remained a significant prognostic factor for DFS [39]. In our study, 28.9% of the included patients received adjuvant treatment. Of the patients who received adjuvant therapy, 91% received chemotherapy only, 3.2% received radiotherapy only, and 2.2% received chemotherapy plus radiotherapy. The most commonly used chemotherapy regimen in adjuvant therapy was the BEP protocol. The most recent ESMO, ESGO, and SIOPE guidelines also continue to recommend the most commonly used BEP regimen [40].

The main limitation of our study is the retrospective study design. Another significant limitation is the lack of a central pathologic examination. However, the large number of participants and the presentation of long-term follow-up results of the included patients are important strengths of our study. Therefore, our study provides additional information on the state of knowledge on this topic.

In conclusion, patients with AGCT should be carefully evaluated for endometrial cancer because of increased estrogen activity. In these cases, lymph node metastasis was found in 3.3%, so that systematic lymph node dissection can be avoided in the primary treatment of patients with AGCT. In our cohort, recurrences also occurred most frequently in the pelvis. Positivity of peritoneal cytology, stage, and menopausal status were found to be independent prognostic predictors of DFS.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

- Data curation: K.V., T.A., Ö.Ç., E.Ö., U.Y., K.Y.H.E., H.C., K.F., E.B., Y.N., Ö.F., K.A., E.S.A., B.S., Ö.E.D., S.İ., U.G., K.Ö., Ç.C., K.S., K.C., C.G.K., Ü.I., 1T.T., N.M.A., 2T.T., T.S., B.N., S.M., K.F.T., T.Ö.M., Ü.Y.E., O.F.

- Formal analysis: O.O.

- Methodology: O.O.

- Writing - original draft: O.O., 3T.T.

- Writing - review & editing: O.O., 3T.T.

1T.T., Tayfun Toptaş; 2T.T., Tolga Taşçı; 3T.T., Taner Turan.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Adjuvant therapy (n=90)

Recurrence pattern, patients (n=34)

References

- 1.Schultz KA, Harris AK, Schneider DT, Young RH, Brown J, Gershenson DM, et al. Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumors. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:940–946. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.016261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schumer ST, Cannistra SA. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1180–1189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young RH. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary and testis: their similarities and differences with consideration of selected problems. Mod Pathol. 2005;18(Suppl 2):S81–S98. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenwig JT, Hazekamp JT, Beecham JB. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathological study of 118 cases with long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol. 1979;7:136–152. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(79)90090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JY, Jin KL, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM, Kim KR, et al. Surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy in the management of patients with adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.12.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YK, Park NH, Kim JW, Song YS, Kang SB, Lee HP. Characteristics of recurrence in adult-type granulosa cell tumor. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:642–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malmström H, Högberg T, Risberg B, Simonsen E. Granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: prognostic factors and outcome. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:50–55. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lappöhn RE, Burger HG, Bouma J, Bangah M, Krans M, de Bruijn HW. Inhibin as a marker for granulosa-cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:790–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909213211204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox H, Agrawal K, Langley FA. A clinicopathologic study of 92 cases of granulosa cell tumor of the ovary with special reference to the factors influencing prognosis. Cancer. 1975;35:231–241. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197501)35:1<231::aid-cncr2820350128>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan RJ, Jr, Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Behbakht K, Chen LM, et al. Ovarian cancer, version 1.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:1134–1163. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombo N, Peiretti M, Garbi A, Carinelli S, Marini C, Sessa C, et al. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii20–vii26. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eitan R, Chi DS. Successful pregnancies following fertility-preserving treatment for ovarian carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2005;2:647–651. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gershenson DM. Management of early ovarian cancer: germ cell and sex cord-stromal tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;55:S62–S72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abu-Rustum NR, Restivo A, Ivy J, Soslow R, Sabbatini P, Sonoda Y, et al. Retroperitoneal nodal metastasis in primary and recurrent granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown J, Sood AK, Deavers MT, Milojevic L, Gershenson DM. Patterns of metastasis in sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: can routine staging lymphadenectomy be omitted? Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inzani F, Santoro A, Travaglino A, D'Alessandris N, Raffone A, Straccia P, et al. Prognostic predictors in recurrent adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306:315–321. doi: 10.1007/s00404-021-06305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Björkholm E, Silfverswärd C. Prognostic factors in granulosa-cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 1981;11:261–274. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(81)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauszus FF, Petersen AC, Greisen J, Jakobsen A. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: a population-based study of 37 women with stage I disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:456–460. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crew KD, Cohen MH, Smith DH, Tiersten AD, Feirt NM, Hershman DL. Long natural history of recurrent granulosa cell tumor of the ovary 23 years after initial diagnosis: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.East N, Alobaid A, Goffin F, Ouallouche K, Gauthier P. Granulosa cell tumour: a recurrence 40 years after initial diagnosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:363–364. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30464-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hines JF, Khalifa MA, Moore JL, Fine KP, Lage JM, Barnes WA. Recurrent granulosa cell tumor of the ovary 37 years after initial diagnosis: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:484–488. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller BE, Barron BA, Wan JY, Delmore JE, Silva EG, Gershenson DM. Prognostic factors in adult granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. Cancer. 1997;79:1951–1955. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970515)79:10<1951::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan JK, Zhang M, Kaleb V, Loizzi V, Benjamin J, Vasilev S, et al. Prognostic factors responsible for survival in sex cord stromal tumors of the ovary--a multivariate analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz PE, Smith JP. Treatment of ovarian stromal tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:402–411. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prat J FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Staging classification for cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;124:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ottolina J, Ferrandina G, Gadducci A, Scollo P, Lorusso D, Giorda G, et al. Is the endometrial evaluation routinely required in patients with adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary? Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:230–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Meurs HS, Bleeker MC, van der Velden J, Overbeek LI, Kenter GG, Buist MR. The incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in 1031 patients with a granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: long-term follow-up in a population-based cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1417–1422. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182a57fb4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee IH, Choi CH, Hong DG, Song JY, Kim YJ, Kim KT, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: a multicenter retrospective study. J Gynecol Oncol. 2011;22:188–195. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2011.22.3.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuru O, Boyraz G, Uckan H, Erturk A, Gultekin M, Ozgul N, et al. Retroperitoneal nodal metastasis in primary adult type granulosa cell tumor of the ovary: can routine lymphadenectomy be omitted? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;219:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayhan A, Tuncer ZS, Tuncer R, Mercan R, Yüce K, Ayhan A. Granulosa cell tumor of the ovary. A clinicopathological evaluation of 60 cases. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1994;15:320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erkılınç S, Taylan E, Karataşlı V, Uzaldı İ, Karadeniz T, Gökçü M, et al. Does lymphadenectomy effect postoperative surgical morbidity and survival in patients with adult granulosa cell tumor of ovary? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2019;45:1019–1025. doi: 10.1111/jog.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangili G, Sigismondi C, Frigerio L, Candiani M, Savarese A, Giorda G, et al. Recurrent granulosa cell tumors (GCTs) of the ovary: a MITO-9 retrospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fotopoulou C, Savvatis K, Braicu EI, Brink-Spalink V, Darb-Esfahani S, Lichtenegger W, et al. Adult granulosa cell tumors of the ovary: tumor dissemination pattern at primary and recurrent situation, surgical outcome. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ertas IE, Gungorduk K, Taskin S, Akman L, Ozdemir A, Goklu R, et al. Prognostic predictors and spread patterns in adult ovarian granulosa cell tumors: a multicenter long-term follow-up study of 108 patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:912–920. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mangili G, Ottolina J, Gadducci A, Giorda G, Breda E, Savarese A, et al. Long-term follow-up is crucial after treatment for granulosa cell tumours of the ovary. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:29–34. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karalok A, Turan T, Ureyen I, Tasci T, Basaran D, Koc S, et al. Prognostic factors in adult granulosa cell tumor: a long follow-up at a single center. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:619–625. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun HD, Lin H, Jao MS, Wang KL, Liou WS, Hung YC, et al. A long-term follow-up study of 176 cases with adult-type ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:244–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seagle BL, Ann P, Butler S, Shahabi S. Ovarian granulosa cell tumor: a National Cancer Database study. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauspy J, Beiner ME, Harley I, Rosen B, Murphy J, Chapman W, et al. Role of adjuvant radiotherapy in granulosa cell tumors of the ovary. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:770–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray-Coquard I, Morice P, Lorusso D, Prat J, Oaknin A, Pautier P, et al. Non-epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:iv1–i18. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Adjuvant therapy (n=90)

Recurrence pattern, patients (n=34)