Abstract

Policy Points.

Multisector collaboration, the dominant approach for responding to health harms created by adverse social conditions, involves collaboration among health care insurers, health care systems, and social services organizations.

Social democracy, an underused alternative, seeks to use government policy to shape the civil (e.g., civil rights), political (e.g., voting rights), and economic (e.g., labor market institutions, property rights, and the tax‐and‐transfer system) institutions that produce health.

Multisector collaboration may not achieve its goals, both because the collaborations are difficult to accomplish and because it does not seek to transform social conditions, only to mitigate their harms. Social democracy requires political contestation but has greater potential to improve population health and health equity.

Keywords: socioeconomic factors, population health, health equity, social policy, social determinants of health

In 2022, president biden convened the white house conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health. 1 This conference identified factors such as food insecurity, nutrition policy, and the built environment as determinants of population health and called for a ‘whole of society’ response, with government, businesses, and nonprofit organizations working together to improve the health of all Americans.

As this conference reflected, there is now wide recognition of the role that social conditions play in shaping health outcomes. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Such recognition invites the question of what to do about social conditions that harm health. The approach advocated for at the White House Conference falls squarely into line with what has become the dominant answer to this question. I refer to this approach as ‘multisector collaboration’ because it emphasizes the need for different sectors in society to work together to tackle the health harms created by adverse social circumstances (‘cross‐sector collaboration’ and ‘intersectoral collaboration’ are analogous terms). 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11

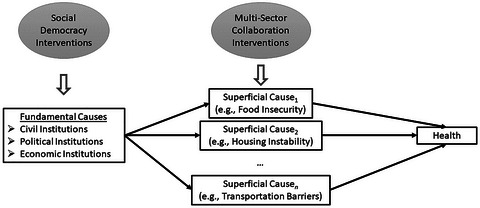

However, the hegemony of multisector collaboration obscures an alternative. This alternative, rather than seeking public–private partnerships to address harms to health, instead seeks to shape the civil, political, and economic institutions that produce health. 12 This approach is termed ‘social democracy’ (Figure 1). 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

Figure 1.

Multisector Collaboration vs. Social Democracy.

A simplified depiction of the relationship among fundamental causes, superficial causes, and health is shown. Because any individual superficial cause is only one of several pathways between fundamental causes and poor health, addressing a specific superficial cause may not improve health outcomes, as the connection between fundamental causes and health can shift to other mechanisms. Social democratic policy typically focuses on fundamental causes, whereas multisector collaboration interventions typically focus on superficial causes.

The goals of this paper are to delineate these two distinct approaches, describe their strengths and limitations, and argue that multisector collaboration, despite being the dominant strategy, may not improve population health as much as hoped. Fundamentally, this stems from the policy instruments that multisector collaboration uses. Although appealing in its pragmatic feasibility and apolitical veneer, these same aspects push toward adopting policy instruments that may not be very effective at improving population health. 16 For this reason, I will argue for prioritizing the social democracy approach while still using multisector collaboration in some cases for specific purposes. Although the arguments in this paper principally focus on the US context, similar dynamics operate in other countries as well. 16

This paper is rooted in the idea that social standing and material resources are ‘fundamental causes’ of health 17 , 18 and that a society's institutions, policies, and practices create a social structure, locate individuals within that structure, and endow them with resources. 19 , 20 This patterns the conditions under which people live and produces the health outcomes people experience. 19 , 20 I believe that advocates of both the multisector collaboration approach and the social democracy approach accept this structural explanation of the causes of poor health and accept that health inequity results from injustices in these structures. The major distinction between the approaches discussed in this paper, however, is whether to focus on policy instruments that mitigate the harms caused by injustices in institutions, policies, and practices or on policy instruments that make those institutions, policies, and practices more just.

What is Multisector Collaboration?

Multisector collaboration involves cooperation among entities, organizations, or agencies, each tasked with different roles in society, to improve health. A common example of multisector collaboration involves partnerships among health care payors (such as insurers), health care producers (such as health care systems), and social services organizations (such as housing support agencies or food pantries). 7 Furthermore, businesses organized as social entrepreneurship and philanthropies or philanthropic efforts from for‐profit companies can be involved, too. This form of multisector collaboration is perhaps epitomized by the growth of ‘screen and refer’ programs, in which an assessment for health‐related social needs is made by health care payors or producers, and then a referral to address needs identified is made to community‐based social services organizations. 21 I believe that multisector collaboration is currently the dominant approach taken by US government agencies, health care providers, and health insurers. Prominent examples of the multisector collaboration approach include the National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Accountable Health Communities model (which served over 1 million Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries) and subsequent models such as ACO REACH (Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health), state‐level Medicaid 1115 waiver programs, initiatives among health care organizations and private health insurers, and calls from both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Academy of Medicine. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37

An important distinction (albeit one not always made clearly) with multisector collaboration interventions is that, although they may understand themselves as addressing social determinants of health (macro‐level social conditions that affect health), they are often actually responding to ‘health‐related social needs’ or ‘social risks’: individual‐level experiences such as food insecurity or housing instability that can result from adverse social determinants of health. 38 , 39 , 40 If material resources and social standing are the ‘fundamental’ causes of health, health‐related social needs can be thought of as ‘superficial’ or ‘surface’ causes of poor health. 17 These superficial causes are typically what multisector collaboration efforts focus on rather than seeking to alter distributive institutions or power relations.

Two themes in multisector collaboration worth discussing are ‘residualism’ and ‘voluntarism.’ Although not every multisector collaboration effort includes these themes, they are common and influential.

Residualism

Residualism is the idea that social services should be offered only for needs that are ‘left over’ or unaddressed by the ‘usual’ ways of meeting needs—through the market or within families. 15 , 41 A hallmark of residualism is focusing on determining whether someone is ‘truly’ in need or deserving of assistance. This is frequently accomplished through means or need testing, meant to ensure that scarce resources are not spent on situations where they do not ‘have’ to be.

This emphasis on the ‘appropriate’ use of scarce resources stems in part from the influence of what Elizabeth Popp Berman has called “the economic style of thinking.” 42 This approach makes virtues of constructs such as (productive) efficiency (in terms of maximizing health ‘output’ for a given amount of resource ‘inputs’), and related ideas such as cost‐effectiveness and targeting interventions to those thought most likely to benefit. Although frequently unstated, the normative orientation of the economic style of thinking is typically consequentialist (i.e., utilitarian). The economic style of thinking is often prominent in justifications made for undertaking multisector collaboration interventions, such as the need to contain health care costs. 39 , 43 , 44 , 45 Evaluation of multisector collaboration interventions often seeks to identify whether the intervention produces ‘return on investment,’ measured in financial terms. 46

Voluntarism

A second theme of multisector collaboration is voluntarism. With voluntarism, the idea is that primary responsibility should lie with private stakeholders, and the role of government is to help coordinate the actions of these stakeholders, facilitate their collaboration, and perhaps provide financing. In this case, the stakeholders are sometimes seen as having social obligations above and beyond their nominal rationale. For example, there may be expectations that companies be ‘good corporate citizens’ by engaging in philanthropic endeavors in addition to their existence as profit making enterprises. 47 , 48 , 49 One example of this is the idea of ‘anchor institutions.’ 48 For instance, some argue that large health care systems should address social determinants of health by paying relatively high wages, offering generous benefits, and using procurement processes to support local economic activity. 48 , 49

Another aspect of voluntarism is giving wide latitude to stakeholders in deciding which initiatives they want to pursue, what specific problems (under the broad rubric of social determinants of health or health‐related social needs) they would like to address, which organizations they would like to partner with, and how they would like to pursue their goals. As long as something (interpreted broadly) is being done, the details of what that something is can be left to the entities involved. In other words, multisector collaboration generally does not mean to create clearly specified rights or benefits that individuals can claim, but rather to enable sectoral stakeholders to be somewhat free to focus on populations and programs that interest them, set their own eligibility criteria, and have leeway on intervention design. Moreover, although community benefit spending rules can encourage possibly beneficial multisector collaboration, power imbalances between health care systems and community organizations may tend to channel the actual form that community benefit spending takes in ways that favor health care systems. 50

What is Social Democracy?

Social democracy refers to a political project that aims to achieve egalitarian, rather than hierarchical, social relationships through policies, programs, and institutions that respect everyone's fundamental moral equality. Unlike the economic virtues of efficiency and targeting emphasized by multisector collaboration, social democracy emphasizes relational equality (equality of status or social standing) and universalism. 51 , 52 , 53 , 54

The term ‘social democracy’ emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the context of egalitarian social movements and, as with many terms, has been used in various ways in different contexts, including during the New Deal and in the ‘era of shared prosperity’ after World War II. 14 , 15 , 55 , 56 , 57 The core use of the term historically, both in the United States and Europe, has referred to political programs focused on three key areas: institutions of civil democracy (e.g., civil rights), institutions of political democracy (e.g., voting rights), and institutions of economic democracy (e.g., labor market institutions, property rights, and the tax‐and‐transfer system). In this paper, I use the term in this sense—that is, as an orientation toward public policy that focuses on these areas. Two examples of US policies that could be considered social democratic in the sense I mean are Social Security Old‐Age and Survivor's Insurance (OASI—a social insurance public pension that covers virtually all older adults in the United States) and the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit, which provided a monthly child benefit to virtually all children in the United States. 58 , 59

Because there exists widespread consensus on at least formal equality for civil and political democracy, the efforts of social democracy with regard to civil and political rights are primarily, although of course not exclusively, related to enforcement so as to make that formal equality substantive and to guard against revanchist efforts. But because economic democracy is underdeveloped in the United States, more extensive policy reforms are pursued in this domain.

In the economic sphere, a key concern is the ‘distributive institutions’—those policies and practices that distribute goods, services, and material resources related to health. 60 , 61 Social democratic policy efforts seek to institutionalize egalitarianism by ensuring that a society's distributive institutions provide the resources one needs to stand as an equal with others. 51 These distributive institutions create the material conditions needed for health and work against social systems that would unjustly deny individuals needed resources.

One way that social democratic policies seek to do this is by providing key services, such as education and health care, as social rights available to all. Another way is through policies related to income distribution, so that individuals can purchase on the market those goods and services necessary for health that are not allocated publicly (e.g., food). 62 Policy relating to income can be subdivided into policy related to ‘factor’ income (income from paid labor or ownership of assets such as land or capital—the ‘factors of production’ in economic parlance) and policy related to ‘transfer’ income (income received without the exchange of goods or services). 63

Social democratic factor income policy tools include pursuing full employment and labor market regulations that encourage and support those who can engage in paid labor. 64 Some examples of such policies are collective bargaining arrangements, minimum wage laws, health and safety regulation, enforcement of antidiscrimination laws, and active labor market policies (e.g., job training and placement).

Another set of social democratic policy tools is transfer income policy. Those engaging in paid labor can receive transfer income, but transfer income policy typically focuses on those who cannot and/or should not engage in paid labor. Such individuals include children, older adults, those with work‐limiting disabilities, those unemployed and looking for work, full‐time students, and those engaging in unpaid (but socially necessary) caregiving. 63 Benefits for individuals in such roles include pensions for older adults, child allowances for children, and disability income for those with work‐limiting disabilities. Transfer income policy, along with in‐kind provision of services such as education and health care, is sometimes collectively referred to as the ‘welfare state.’

Transfer income policy is financed by taxation. Social democratic tax policy is typically based around progressive income taxation, supplemented by payroll taxes (typically a flat or regressive form of income taxation), wealth taxation (including taxes on corporations), and consumption taxation (such as a ‘value added tax’ [VAT] or sales tax). 62 , 65 The purpose of the tax system is both to finance government spending and to help prevent extreme income and wealth inequality that results in unjust concentrations of power and undermines egalitarian social relations. 66 The social democratic tax‐and‐transfer system is progressive on net (even if individual taxes or benefit programs may not be), meaning that those with lower factor incomes typically receive greater, at least in relative terms, net benefits than those with higher factor incomes. 67

One way to think about the social democratic approach to addressing social determinants of health is that distributive institutions distribute general resources (e.g., money or social standing) based on an individual's location within the social structure. Those general resources can be converted into specific resources needed for health (e.g., food, housing, or health care). If the specific resources needed for health are scarce, there will be competition for them, which will tend to favor those with greater allotments of general resources. 17 This will pattern health along lines of general resource distribution. By seeking egalitarian distributive institutions, the social democratic approach works to equalize the distribution of resources that are the fundamental causes of health.

Strengths and Limitations of Multisector Collaboration

Multisector collaboration has several strengths. First, it seems intuitive that bringing multiple kinds of expertise together would be helpful for complicated problems such as addressing social determinants of health and health‐related social needs. Our world is complex, and our society is highly specialized—taking advantage of everyone's expertise seems reasonable. A second strength is that multisector collaboration seems feasible. Getting laws passed or changing policy may seem much more daunting than starting a program within one's organization or bringing together a group of like‐minded individuals from different sectors on a voluntary basis. Adverse social determinants of health present pressing problems, so multisector collaboration might be a way to at least do something. Further, even for those who prefer a social democratic approach, multisector collaboration may be a harm reduction strategy when it is unwise to risk a political confrontation or when such a confrontation seems doomed to failure. Ultimately, these strengths boil down to the idea that multisector collaboration is feasible.

Although the argument of feasibility seems compelling, its virtue is heavily premised on another, often unstated factor—effectiveness. If multisector collaboration can effectively address consequences of adverse social determinants of health and is more feasible than other approaches, then that would indeed recommend it. However, if its impact is minimal, then its feasibility is no virtue.

But why would multisector collaboration be ineffective? First, many multisector collaborations are cumbersome and difficult to make work, making the approach less feasible than meets the eye. Second, multisector collaboration can wind up benefiting the collaborating organizations more than the individuals served. Third, the policy instruments needed for multisector collaboration do not really get at the fundamental causes of poor health. Multisector collaboration often seeks to mitigate the consequences of injustice, focusing on superficial causes of poor health rather than transforming social institutions to affect fundamental causes.

(In)Feasibility

A touted strength of multisector collaboration is feasibility—for example, having a health insurer, health care system, and community‐based social services organization work together to fight food insecurity seems more feasible than enacting a federal child allowance. But multisector collaboration presents different concerns that call its feasibility into question. The primary reason for this is that coordinating across sectors is extremely challenging, rife with both barriers and costs. Evaluations of multisector collaboration interventions frequently remark on how difficult working across sectors really is. 16 , 24 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 68 , 69 , 70 There are mundane difficulties, such as poor interoperability of information technology platforms and learning curves for organizations working in regulatory environments they are not used to. And there are harder problems, such as misaligned incentives across sectors, e.g., the ‘wrong pocket problem,’ a type of externality in which the benefits of expenditures made by one organization or sector accrue to another. 47 , 71 , 72

Furthermore, multisector collaboration can create multiple goals and obligations for organizations that may be contradictory. For example, the idea of anchor institutions calls on organizations to accept social responsibility. 47 , 48 In health care, this can take the form of asking health care organizations both to hold down the costs of producing health care and to pay employees more than the organization may otherwise be able to bargain for. Both goals are laudable, but they are in tension.

An additional problem is that the expansiveness of multisector collaboration can make change more difficult. For example, although transportation policy can certainly affect health, and so particular versions of transportation policy could improve health, requiring that all transportation policy decisions undergo a health impact assessment before being made could bog down the policymaking process. This could engender a status quo bias that makes implementing new policy harder and increases the chance that existing policy will be maintained by default, even if it is health harming.

Another feasibility concern is that by making social determinants of health everyone's problem, multisector coordination makes them no one's problem—that is, it diffuses responsibility for addressing the issues to the point that it is difficult to hold any specific actor accountable for improvement.

Overall, evaluations of large‐scale multisector collaboration approaches make clear that these feasibility issues substantially undermine real‐world effectiveness. 16

Stakeholder Power

The theme of voluntarism common in multisector collaboration reduces the role of the state, and thus, in a democracy, the citizens, in taking primary responsibility for addressing social determinants of health. Instead, the state is often relegated to the role of facilitator or funder rather than lead actor. This elevates in importance organizations that may be hierarchical (e.g., private firms) rather than democratic, greatly increasing the power of these nondemocratic stakeholders. 73 , 74 Many multisector collaboration interventions are not really under democratic control. Nongovernmental organizations, with leadership that is not empaneled democratically, effectively decide what to prioritize and what implementation strategies to pursue, potentially with little input or oversight from the people affected or society more generally. This stakeholder power comes with risks of veto points and the opportunity for rent seeking by those who can now threaten to gum up the works if they do not get their way. Moreover, stakeholder organizations may be better organized than program beneficiaries and thus better able to influence policymaking and program implementation. This can create overemphasis on the desires and concerns of the involved organizations at the expense of those the programs are meant to benefit. Furthermore, if some organizations within a collaboration are more powerful than others, their interests can tend to predominate.

Multisector collaboration can also leave private entities free to set the agenda, possibly only focusing on issues most of interest to them or ones that seem most profitable to address. 72 But what is profitable to address, or what interests private organizations, may bear little relation to clinical need or what society would, democratically, choose to devote resources to. In a sense, multisector collaboration outsources government responsibility to private organizations. This means that individuals may be dependent on the good will of nondemocratic entities and that public dollars are sent to private organizations rather than directly to the people the organizations aim to serve.

Mitigation, Not Transformation

Although the above problems are important, perhaps the fundamental problem of multisector collaboration is that it focuses on treatment (mitigating the harms of unjust social relations) rather than prevention (transforming social relations into something more just). Because it relies on collaboration across sectors, multisector collaboration needs to avoid conflict among sectors and encourage consensus. This could lead to productive cooperation, but it could also limit the scope of options to those all can agree on. As political scientist Ed Burmila points out, the spirit of pragmatic feasibility that multisector collaboration often adopts “inherently respects the limitations imposed by the existing hierarchy of power, institutions, and rules; any solutions that emerge from it will perpetuate the same power relationships.” 75 p206 In other words, multisector collaboration seeks to work within existing distributive institutions rather than imagining a world with different institutions that promote health for everyone. This means that, although superficial causes of poor health might be amenable to multisector collaboration interventions, addressing fundamental causes is usually off the table. But, as fundamental cause theory teaches, addressing a superficial cause may not actually improve health if fundamental causes go unaddressed because the mechanism that creates poor health simply shifts. 17 For instance, addressing transportation barriers that prevent people from attending health care appointments may not, in fact, improve health if they cannot afford the medications prescribed at those appointments.

Because they often do not aim to address fundamental causes, multisector collaboration interventions can experience ‘downstream drift.’ 16 Downstream drift refers to justifying interventions on the basis of structural barriers to health but in practice focusing on individual‐level behaviors. An example of this would be recognizing that insufficient transfer income policy creates food insecurity, which harms health, and then intervening with educational sessions that focus on ‘eating healthy on a budget.’ Such interventions might draw rhetorically on a structural understanding of the issues, but in practice they are forms of ‘health entrepreneurialism’—the idea that individuals bear the primary responsibility for overcoming structural adversity through adopting resilient behaviors. 76

Multisector collaboration interventions are often very circumscribed in both their vision and evaluation. Evaluation of such interventions typically adopts standards of evidence that shape the form of the intervention, frequently focusing on discrete, quantifiable change over short time periods. Such methods have difficulty assessing hard‐to‐quantify outcomes or evaluating complex interactions of intervention components and background context. 77 , 78 , 79 Such methods may also have an inherent conservativism, best at evaluating slight changes from the status quo and being disfavorable toward more transformative interventions. 80

Because multisector collaboration seeks to avoid political confrontation, it can also slot in uncomfortably easily with motivations that are hierarchical rather than egalitarian. Although not all multisector collaboration interventions are designed this way, some advocate for interventions to include disciplinary elements, meant to “set right the lives of the poor,” 81 with the need for the intervention taken as evidence of being incapable of managing one's affairs without close supervision. Prominent examples of this include seeking to restrict Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits to ‘healthy’ foods 82 or requiring certain ‘health‐promoting’ conditions to be met before receiving a cash transfer. 83

Such programs can reproduce social inequality, rather than challenging it, by requiring people to participate in tightly managed programs to meet basic needs. As sociologist T.H. Marshall pointed out, beneficiaries in these cases become second‐class citizens who receive much more extensive oversight, either from the state or the private entities administering a program, than other individuals. 53 Rather than increasing the rights of citizens, such programs become alternatives to full citizenship.

Strengths and Limitations of Social Democracy

The primary strength of the social democratic approach is its effectiveness in alleviating adverse social determinants of health. Countries that implement social democratic policy instruments consistently achieve low levels of poverty (both overall and for high‐risk subgroups such as children and older adults), low levels of income inequality, low levels of food insecurity, high levels of education, high workforce participation, and strong economic growth. 13 , 84 , 85 , 86 These are reflected in key population health indicators such as long life expectancies (even for those with relatively low income within a given country), 87 low infant and maternal mortality, low years of life lost due to disability, and high health‐related quality of life. 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97

In the United States, state policy contexts in which social democratic policy goals, such as strong income supports and wide enfranchisement, are pursued have been found to offer health advantages over states where policies move away from such goals. 98 , 99 , 100 Specific policies that fit broadly under the rubric of social democracy, such as OASI, the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit, and the pandemic unemployment insurance programs, have all been associated with health benefits. 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108

The space in which social democratic policy operates is by no means small. But it is a strength that social democracy does not depend on collaboration across sectors, which has proven difficult to accomplish. 16 Interestingly, multisector collaboration faces an important coordination problem that social democracy does not. Some goods and services, notably basic education and health care, require public provision because they are not well allocated by the market. 62 But other goods and services, such as food or housing, may be well allocated by the market if individuals have sufficient income and bargaining power. 62 By providing transfer income and protecting bargaining power, social democracy can make use of markets to coordinate allocation of such goods and services. Multisector collaboration, in contrast, must rely on what are effectively ‘command economy’ approaches to allocating these goods and services. This includes identifying those in need of assistance, managing the collaboration between health care systems and providers of those goods and services, and even taking on additional responsibilities thought to be in service of the goals—e.g., providing not just food but ‘healthy’ food—creating additional programmatic complexity. There may be some irony in social democracy being more able to use markets than multisector collaboration, but there is also plenty of truth to it.

Social democratic approaches, because they are led by government and implemented for everyone, can also achieve economies of scale that multisector collaboration programs do not. Moreover, means or need testing, which creates administrative burdens and reduces program uptake, 109 is generally not needed. Means testing tends to reinforce social stratification by creating some programs explicitly for individuals with low income while better‐off individuals use other programs to meet the same needs (e.g., one form of health insurance for individuals with lower income, another for individuals with higher income). 110 , 111 Also, contrary to expectations, means testing offers few financial benefits. 59 , 112 Furthermore, multisector collaboration often leads to numerous similar programs spread across different clusters of stakeholders—for example, several health care systems may operate their own food pantries. But having every health care system or insurer run its own private welfare state to address food insecurity, housing instability, and transportation barriers for its patients is clearly inefficient.

Finally, social democratic policy can be countercyclical in a way that multisector collaboration is not. During business cycle downturns, health‐related social needs are likely to spike. But voluntary philanthropic efforts tend to pull back at these times—just when they are needed most—because the downturn hurts the business position of the stakeholders. Social democratic governments can run deficits during downturns to match assistance with need.

The primary limitation of the social democratic approach is the need for political contestation to accomplish it. Multisector collaboration is appealing to many precisely because it does not challenge status quo power relations. If that appeal draws from a pragmatic assessment regarding the likelihood of success in a political confrontation, it may be justified, assuming that multisector collaboration is effective at improving health. If, however, it results from a fundamental acceptance of unjust power relations, with a desire only to mitigate their worst consequences or to stave off political confrontation that may move toward more just social relations, then its appeal should be reconsidered.

Another concern is that, in pushing for social democratic policies, there could be a backlash toward retrenchment of policy gains already made. This is certainly possible and should be considered as part of strategizing about social democratic goals. Ultimately, however, the possibility of backlash should not prevent careful pursuit of policies likely to address the social determinants of health.

Next, the connection between social democratic policies and health may be less immediately clear than those of multisector collaboration, which can present a messaging issue. For example, programs in which individuals with diabetes and food insecurity are referred by their clinic to a community‐based food organization are quite legible as health interventions. But making the connection between enacting a child allowance and reduced food insecurity may require more explanation. 105

Finally, especially in the United States, people may simply be unaware of social democracy as a cohesive strategy to improve population health. The US political discourse since the late 1970s has sidelined social democratic perspectives, 56 , 57 , 75 which means that it may not seem to be ‘on the menu,’ despite empirical findings in favor of social democratic policy approaches. 13 , 84 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97

Pursuing Social Democratic Policy Goals

The purpose of this paper has been to make clear the distinction between the multisector collaboration and social democratic approaches to addressing social determinants of health and to discuss their strengths and limitations. One important limitation of the social democratic approach is the need for political contestation to achieve those goals. A natural next step, then, is to consider how this could be done. Achieving political change is, of course, a complex topic—one that I cannot do justice to in the context of this paper. But it is also a very important topic, and so I believe at least a brief discussion is warranted. Fundamentally, such change needs a broad, deep, and enduring coalition. This can be built by effective organizing around shared goals of health, well‐being, and material security. 113 Historically, ‘power resources’ theory has helped to explain both the role of electoral politics and grassroots (particularly labor‐related) organizing in enacting social democratic policies. 14 , 114 , 115 More recently, several public and population health scholars have emphasized the need for such organizing to improve population health and confront power relations that harm health, and their work provides both empiric examples and guidance that may be useful in pursuing social democratic policies. 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120

Conclusions

Multisector collaboration is at heart technocratic—a bet that expertise can manage the consequences of adverse social determinants of health. It offers a technical fix for what is ultimately a political problem. Pursuing multisector collaboration may be a strategic choice when avoiding a political confrontation seems desirable, but it will be helpful only if effective. Optimistically, multisector collaboration is feasible harm reduction that people without the political power to make more substantive changes can engage in. This is unobjectionable but should at least be acknowledged as second best. More pessimistically, however, multisector collaboration could become a way to delegate managerial authority, and the funds that come with it, over the problems produced by social inequality.

The social democratic approach is different. Rather than trying to tackle all of the areas in which the harms of injustice can be expressed, social democracy focuses on the core policy areas in which injustice is created. In this sense, it attempts to deal with the fundamental causes of health inequity rather than trying to address each superficial cause. From the social democratic perspective, the fundamental causes of health are addressed, not by examining the health impacts of each and every policy, but through economic democracy—through factor income policy, transfer income policy, and taxation—in a setting of egalitarian civil and political rights.

I do not think it is wrong to pursue multisector collaboration in all cases. For instance, I see a role for multisector collaboration in chronic disease management for those who experience health‐related social needs and who would benefit from the involvement of clinical and other expertise in their management. This situation may occur even if policy moves in a social democratic direction and certainly exists in the United States right now. But this means that multisector collaboration is a secondary strategy, to be deemphasized in favor of social democracy. The need to treat the harms of adverse social determinants of health should not distract us from trying to prevent adverse social determinants of health in the first place.

Fundamentally, multisector collaboration programs are not meant to interfere with social inequality. The alternative, social democracy, seeks equality at all sites of human cooperation. This is why social democracy can achieve health equity, and multisector collaboration, even if beneficial in some cases, will not.

Funding/Support

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: R01DK125406.

References

- 1. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed May 2, 2023. https://health.gov/our‐work/nutrition‐physical‐activity/white‐house‐conference‐hunger‐nutrition‐and‐health [Google Scholar]

- 2. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Equitable long‐term recovery and resilience. US Department of Health and Human Services. Updated December 5, 2023. Accessed August 4, 2023. https://health.gov/our‐work/national‐health‐initiatives/equitable‐long‐term‐recovery‐and‐resilience [Google Scholar]

- 3. Social determinants of health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Accessed October 26, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 4. Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. Accessed May 10, 2021. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health‐topics/social‐determinants‐of‐health [Google Scholar]

- 5. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Healthy people 2030. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://health.gov/healthypeople [Google Scholar]

- 6. Institute of Medicine. The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century. National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woulfe J, Oliver TR, Siemering KQ, Zahner SJ. Multisector partnerships in population health improvement. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(6):A119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities–addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8‐11. 10.1056/NEJMp1512532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu PY, Beck AF, Lindau ST, et al. A framework for cross‐sector partnerships to address childhood adversity and improve life course health. Pediatrics. 2022;149(Suppl 5):e2021053509O. 10.1542/peds.2021-053509O [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Egede LE, Ozieh MN, Campbell JA, Williams JS, Walker RJ. Cross‐sector collaborations between health care systems and community partners that target health equity/disparities in diabetes care. Diabetes Spectr. 2022;35(3):313‐319. 10.2337/dsi22-0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corley AMS, Henize AW, Klein MD, Beck AF. Pursuing a cross‐sector approach to advance child health equity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2023;70(4):709‐723. 10.1016/j.pcl.2023.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lynch J. Reframing inequality? The health inequalities turn as a dangerous frame shift. J Public Health (Oxf). 2017;39(4):653‐660. 10.1093/pubmed/fdw140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kenworthy L. Social Democratic Capitalism. Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Béland D, Morgan KJ, Obinger H, Pierson C, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esping‐Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lynch J. Regimes of Inequality. Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;Spec No:80‐94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51 Suppl:S28‐S40. 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krieger N. Epidemiology and the People's Health: Theory and Context. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krieger N. Ecosocial Theory, Embodied Truths, and the People's Health. Oxford University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fichtenberg C, Fraze TK. Two questions before health care organizations plunge into addressing social risk factors. NEJM Catalyst. 2023;4(4):CAT.22.0400. 10.1056/CAT.22.0400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Accountable health communities model. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation‐models/ahcm [Google Scholar]

- 23. Parish W, Beil H, He F, et al. Health care impacts of resource navigation for health‐related social needs in the accountable health communities model. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(6):822‐831. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Renaud J, McClellan SR, DePriest K, et al. Addressing health‐related social needs via community resources: lessons from accountable health communities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(6):832‐840. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wortman Z, Tilson EC, Cohen MK. Buying health for North Carolinians: addressing nonmedical drivers of health at scale. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):649‐654. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berkowitz SA. Health care's new emphasis on social determinants of health. NEJM Catalyst. 4(4):CAT.23.0070. 10.1056/CAT.23.0070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whole person care pilots. California Department of Health Care Services. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/Pages/WholePersonCarePilots.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gunter KE, Tanumihardjo JP, O'Neal Y, Peek ME, Chin MH. Integrated interventions to bridge medical and social care for people living with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(Suppl 1):4‐10. 10.1007/s11606-022-07926-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saulsberry L, Gunter KE, O'Neal Y, et al. “Everything in one place”: stakeholder perceptions of integrated medical and social care for diabetes patients in western Maryland. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(Suppl 1):25‐32. 10.1007/s11606-022-07919-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Taira BR, Yadav K, Perez Y, et al. A formative evaluation of social care integration across a safety‐net health system. NEJM Catalyst. 2023;4(4):CAT.22.0232. 10.1056/CAT.22.0232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gold R, Kaufmann J, Cottrell EK, et al. Implementation support for a social risk screening and referral process in community health centers. NEJM Catalyst. 2023;4(4):CAT.23.0034. 10.1056/CAT.23.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schweitzer A, Mohta NS. Pathways to success in meeting health‐related social needs. NEJM Catalyst. 2023;4(4):CAT.22.0352. 10.1056/CAT.22.0352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. De Marchis EH, Aceves BA, Brown EM, Loomba V, Molina MF, Gottlieb LM. Assessing implementation of social screening within US health care settings: a systematic scoping review. J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(4):626‐649. 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220401R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Biden‐Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger Nutrition and Health. The White House. 2022. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp‐content/uploads/2022/09/White‐House‐National‐Strategy‐on‐Hunger‐Nutrition‐and‐Health‐FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation's Health. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi: 10.17226/25467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Work together | tools for successful CHI efforts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 19, 2022. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/chinav/tools/work.html [Google Scholar]

- 37. ACO REACH . Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation‐models/aco‐reach

- 38. Lantz PM. The medicalization of population health: who will stay upstream? Milbank Q. 2018;97(1):36‐39. 10.1111/1468-0009.12363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lantz PM, Goldberg DS, Gollust SE. The perils of medicalization for population health and health equity. Milbank Q. 2023;101(S1):61‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407‐419. 10.1111/1468-0009.12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jacques O, Noël A. Targeting within universalism. J Euro Soc Policy. 2021;31(1):15‐29. 10.1177/0958928720918973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Berman EP. Thinking Like an Economist: How Efficiency Replaced Equality in U.S. Public Policy. Princeton University Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lantz PM. “Super‐utilizer” interventions: what they reveal about evaluation research, wishful thinking, and health equity. Milbank Q. 2020;98(1):31‐34. 10.1111/1468-0009.12449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fleming MD, Shim JK, Yen I, Van Natta M, Hanssmann C, Burke NJ. Caring for “super‐utilizers”: neoliberal social assistance in the safety‐net. Med Anthropol Q. 2019;33(2):173‐190. 10.1111/maq.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kanzaria HK, Niedzwiecki M, Cawley CL, et al. Frequent emergency department users: focusing solely on medical utilization misses the whole person. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(11):1866‐1875. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Welcome to the return on investment (ROI) calculator for partnerships to address the social determinants of health. The Commonwealth Fund. Accessed November 23, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/roi‐calculator [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jain P, Jain B, Dee EC. Corporate social responsibility framework: an innovative solution to social determinants of health in the USA. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities . Published online January 23, 2023. 10.1007/s40615-022-01493-2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Ansell DA, Fruin K, Holman R, Jaco A, Pham BH, Zuckerman D. The anchor strategy ‐ a place‐based business approach for health equity. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(2):97‐99. 10.1056/NEJMp2213465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Koh HK, Bantham A, Geller AC, et al. Anchor institutions: best practices to address social needs and social determinants of health. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(3):309‐316. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hawryluk M. Community with high medical debt questions its hospitals’ charity spending. KFF Health News . August 29, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/medical‐debt‐hospitals‐charity‐care‐community‐benefit‐colorado/

- 51. Anderson ES. What is the point of equality? Ethics. 1999;109(2):287‐337. 10.1086/233897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Anderson ES. The fundamental disagreement between luck egalitarians and relational egalitarians. Can J Philos. 2010;40(sup1):1‐23. 10.1080/00455091.2010.10717652 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marshall TH. Citizenship and Social Class: And Other Essays. University Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rothstein B. Managing the welfare state: lessons from Gustav Möller*. Scand Polit Stud. 1985;8(3):151‐170. 10.1111/j.1467-9477.1985.tb00318.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dow G, Higgins W. Politics Against Pessimism: Social Democratic Possibilities since Ernst Wigforss. Peter Lang AG; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Carter ZD. The Price of Peace: Money, Democracy, and the Life of John Maynard Keynes. Random House; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Reed T. Toward Freedom: The Case Against Race Reductionism. Verso; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Diamond PA. Taxation, Incomplete Markets, and Social Security. MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Berkowitz SA, Orr CJ, Palakshappa D. The public health case for a universalist child tax credit. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(9):843‐844. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Berkowitz SA, Palakshappa D. Gaps in the welfare state: A role‐based model of poverty risk in the U.S. PLoS One. 2023;18(4):e0284251. 10.1371/journal.pone.0284251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brady D. Poverty, not the poor. Science Advances. 2023;9(34):eadg1469. 10.1126/sciadv.adg1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Barr N. Economics of the Welfare State. Oxford University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Berkowitz SA. The logic of policies to address income‐related health inequity: a problem‐oriented approach. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):370‐392. 10.1111/1468-0009.12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kalecki M. Political aspects of full employment. Polit Q. 1943;14(4):322‐330. 10.1111/j.1467-923X.1943.tb01016.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Saez E, Zucman G. Progressive wealth taxation. The Brookings Institution. September 5, 2019. Accessed March 31, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/bpea‐articles/progressive‐wealth‐taxation/ [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saez E, Zucman G. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay. 1st ed. W. W. Norton & Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sligar D. The first principle of social democratic tax design is MOAR. Western Sydney Wonk. May 20, 2020. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://westernsydneywonk.wordpress.com/2020/05/20/the‐first‐principle‐of‐social‐democratic‐tax‐design‐is‐moar/ [Google Scholar]

- 68. Taylor LA, Byhoff E. Money moves the mare: the response of community‐based organizations to health care's embrace of social determinants. Milbank Q. 2021;99(1):171‐208. 10.1111/1468-0009.12491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Garg A, Byhoff E, Wexler MG. Implementation considerations for social determinants of health screening and referral interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e200693. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Berkowitz SA, Gottlieb LM, Basu S. financing health care system interventions addressing social risks. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(2):e225241. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.5241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Palakshappa D, Garg A, Peltz A, Wong CA, Cholera R, Berkowitz SA. Food insecurity was associated with greater family health care expenditures in the US, 2016–17. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(1):44‐52. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Karaca‐Mandic P, Nikpay S, Gibbons S, Haynes D, Koranne R, Thakor R. Proposing an innovative bond to increase investments in social drivers of health interventions in Medicaid managed care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(3):383‐391. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Friel S, Townsend B, Fisher M, Harris P, Freeman T, Baum F. Power and the people's health. Soc Sci Med. 2021;282:114173. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kelly AS. Private power in public programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and the structural power of private insurance. Stud Am Political Dev. 2023;37(1):24‐40. 10.1017/S0898588X22000207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Burmila E. Chaotic Neutral: How the Democrats Lost Their Soul in the Center. Bold Type Books; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Reed A. The trouble with uplift. The Baffler . September 4, 2018. Accessed December 2, 2021. https://thebaffler.com/salvos/the‐trouble‐with‐uplift‐reed

- 77. Matthay EC, Gottlieb LM, Rehkopf D, Tan ML, Vlahov D, Glymour MM. What to do when everything happens at once: analytic approaches to estimate the health effects of co‐occurring social policies. Epidemiol Rev. 2022;43(1):33‐47. 10.1093/epirev/mxab005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Matthay EC, Glymour MM. Causal inference challenges and new directions for epidemiologic research on the health effects of social policies. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2022;9:22‐37. 10.1007/s40471-022-00288-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. PCORI methodology standards: standards for studies of complex interventions . Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute. November 12, 2015. Accessed December 6, 2018. https://www.pcori.org/research‐results/about‐our‐research/research‐methodology/pcori‐methodology‐standards#Complex

- 80. Schwartz S, Prins SJ, Campbell UB, Gatto NM. Is the “well‐defined intervention assumption” politically conservative? Soc Sci Med. 2016;166:254‐257. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rothstein B. Just Institutions Matter: The Moral and Political Logic of the Universal Welfare State. Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Rubio M. No more subsidies for junk food. The Wall Street Journal . May 7, 2023. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/no‐more‐subsidies‐for‐junk‐food‐snap‐reform‐diet‐health‐obesity‐diabetes‐e1204287

- 83. Riccio JA, Dechausay N, Miller C, Nuñez S, Verma N, Yang E. Conditional Cash Transfers in New York City: The Continuing Story of the Opportunity NYC–Family Rewards Demonstration. MDRC. September 23, 2013. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.mdrc.org/publication/conditional‐cash‐transfers‐new‐york‐city [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lindert PH. Making Social Spending Work. Cambridge University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 85. OECD Data . Inequality ‐ poverty rate. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Accessed January 18, 2022. http://data.oecd.org/inequality/poverty‐rate.htm [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ostry JD, Berg A, Tsangarides CG. Redistribution, inequality, and growth. Staff Discussion Notes No. 2014/002. International Monetary Fund; 2014. 10.5089/9781484352076.006 [DOI]

- 87. Kinge JM, Modalsli JH, Øverland S, et al. Association of household income with life expectancy and cause‐specific mortality in Norway, 2005–2015. JAMA. 2019;321(19):1916‐1925. 10.1001/jama.2019.4329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives. Public Health. 2012;126(Suppl 1):S4‐S10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Reeves A, Basu S, McKee M, Marmot M, Stuckler D. Austerity's health effects: a comparative analysis of European budgetary changes. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(Suppl 1):ckt126.148. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt126.148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TAJ, Taylor S; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1661‐1669. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bambra C. Going beyond the three worlds of welfare capitalism: regime theory and public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(12):1098‐1102. 10.1136/jech.2007.064295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bambra C. In defence of (social) democracy: on health inequalities and the welfare state. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(9):713‐714. 10.1136/jech-2013-202937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Beckfield J, Bambra C, Eikemo TA, Huijts T, McNamara C, Wendt C. An institutional theory of welfare state effects on the distribution of population health. Soc Theory Health. 2015;13(3):227‐244. 10.1057/sth.2015.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Bor J, Stokes AC, Raifman J, et al. Missing Americans: early death in the United States, 1933–2021. PNAS Nexus. 2023;2(6):pgad173. 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Ahmed S, et al. Public policy and health in the Trump era. Lancet. 2021;397(10275):705‐753. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32545-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Global burden of disease (GBD) . Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2019. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.healthdata.org/research‐analysis/gbd

- 97. Global health estimates: life expectancy and leading causes of death and disability. World Health Organization. 2019. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality‐and‐global‐health‐estimates [Google Scholar]

- 98. Montez JK, Grumbach JM. US state policy contexts and population health. Milbank Q. 2023;101(S1):196‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Montez JK, Beckfield J, Cooney JK, et al. US state policies, politics, and life expectancy. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):668‐699. 10.1111/1468-0009.12469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Woolf SH. The growing influence of state governments on population health in the United States. JAMA. 2022;327(14):1331‐1332. 10.1001/jama.2022.3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Arno PS, House JS, Viola D, Schechter C. Social security and mortality: the role of income support policies and population health in the United States. J Public Health Policy. 2011;32(2):234‐250. 10.1057/jphp.2011.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Brucker DL, Jajtner K, Mitra S. Does Social Security promote food security? Evidence for older households. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2022;44(2):671‐686. 10.1002/aepp.13218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Parolin Z, Ananat E, Collyer S, Curran M, Wimer C. The effects of the monthly and lump‐sum Child Tax Credit payments on food and housing hardship. AEA Papers Proc. 2023;113:406‐412. 10.1257/pandp.20231088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Batra A, Jackson K, Hamad R. Effects of the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit on adults’ mental health: a quasi‐experimental study. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(1):74‐82. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bovell‐Ammon A, McCann NC, Mulugeta M, Ettinger de Cuba S, Raifman J, Shafer P. Association of the expiration of Child Tax Credit advance payments with food insufficiency in US households. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2234438. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.34438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Rook JM, Yama CL, Schickedanz AB, Feuerbach AM, Lee SL, Wisk LE. Changes in self‐reported adult health and household food security with the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit monthly payments. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(6):e231672. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Berkowitz SA, Basu S. Unmet social needs and worse mental health after expiration of COVID‐19 federal pandemic unemployment compensation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):426‐434. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Raifman J, Bor J, Venkataramani A. Association between receipt of unemployment insurance and food insecurity among people who lost employment during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2035884. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Ko W, Moffitt RA. Take‐up of social benefits. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 30148. 2022. Accessed December 15, 2023. https://www.nber.org/papers/w30148

- 110. Sen A. The political economy of targeting. In: van de Walle D, Nead K, eds. Public Spending and the Poor. World Bank; 1995:11‐23. [Google Scholar]

- 111. Korpi W, Palme J. The paradox of redistribution and strategies of equality: welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the Western countries. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63(5):661‐687. 10.2307/2657333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Apps P, Rees R, Thoresen TO, Vattø TE. Alternatives to paying child benefit to the rich. Means testing or higher tax? Statistics Norway, Research Department Discussion Papers 969. 2021. Accessed January 18, 2022. https://ideas.repec.org/p/ssb/dispap/969.html

- 113. McAlevey JF. No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age. Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 114. Brady D. Rich Democracies, Poor People: How Politics Explain Poverty. Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 115. Korpi W. The Democratic Class Struggle. 1st ed. Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Michener J. Racism, power, and health equity: the case of tenant organizing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(10):1318‐1324. 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Iton A, Ross RK, Tamber PS. Building community power to dismantle policy‐based structural inequity in population health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(12):1763‐1771. 10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Heller JC, Little OM, Faust V, et al. Theory in action: public health and community power building for health equity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2023;29(1):33‐38. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Heller JC, Fleming PJ, Petteway RJ, Givens M, Pollack Porter KM. Power up: a call for public health to recognize, analyze, and shift the balance in power relations to advance health and racial equity. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(10):1079‐1082. 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Reynolds MM. Health power resources theory: a relational approach to the study of health inequalities. J Health Soc Behav. 2021;62(4):493‐511. 10.1177/00221465211025963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]