Abstract

Background:

Despite research demonstrating the risks of feeding tubes in persons with advanced dementia, they continue to be placed. The natural history of dysphagia among patients with advanced dementia has not been examined. We conducted a secondary analysis of a national cohort of persons with advanced dementia with a nursing home stay before hospitalization to examine 1) pre-hospitalization dysphagia prevalence and 2) risk of feeding tube placement during hospitalization based on pre-existing dysphagia.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study consisting of all nursing home (NH) residents (≥66 years) with advanced dementia (Cognitive Function Scale score ≥2), a hospitalization between 2013–2017, and a Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 assessment within 120 days before hospitalization. Pre-hospitalization dysphagia status and surgically placed feeding tube insertion during hospitalization were determined by MDS 3.0 swallowing items and ICD-9 codes, respectively. A multivariate logistic model clustering on hospital was used to examine the association of dysphagia with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube placement after adjustment for confounders.

Results:

Between 2013 and 2017, 889,983 persons with NH stay with advanced dementia (mean age: 84.5, SD: 7.5, and 63.5% female) were hospitalized. Pre-hospitalization dysphagia was documented in 5.4% (n=47,574) and characterized by oral dysphagia (n=21,438, 2.4%), pharyngeal dysphagia (n=24,257, 2.7%), and general swallowing complaints/pain (n=14,928, 1.7%). Overall, PEG feeding tubes were placed in 3,529 patients (11.2%) with pre-hospitalization dysphagia while 27,893 (88.8%) did not have pre-hospitalization according to MDS 3.0 items. Feeding tube placement risk increased with the number of dysphagia items noted on the pre-hospitalization MDS (6 vs. 0 dysphagia variables: OR=5.43, 95% CI: 3.19–9.27).

Conclusions:

Based on MDS 3.0 assessment, only 11% of PEG feeding tubes were inserted in persons with prior dysphagia. Future research is needed on whether this represents inadequate assessment or the impact of potentially reversible intercurrent illness resulting in feeding tube placement.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dysphagia, swallowing, enteral nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is common among older adults in the United States and represents a leading cause of death.1 Dementia is characterized by progressive cognitive and functional impairments with difficulty swallowing that may result in weight loss and/or recurrent aspiration pneumonia. Difficulty eating, also referred to as dysphagia, is noted to occur in up to 86% of persons with advanced dementia,2 placing it among the most prevalent functional impairments endured by persons living with dementia. Although dysphagia was formerly considered a late-stage sequela of dementia,3 emerging evidence has demonstrated biomechanical swallowing changes such as reduced laryngeal and hyoid elevation and prolonged laryngeal vestibule closure develop in the mild stage of the disease and accelerate with disease progression.4,5 Further infections such as urinary tract infections and respiratory infections, which are common in patients with dementia,2,6,7 may result in a functional decline in nursing home residents8 potentially impacting the ability to eat safely.9

Given the incidence of eating difficulties in patients with dementia, an important decision becomes how to address swallowing and nutritional concerns during the disease course. Historically, feeding tube placement was thought to be a relatively straightforward way to sustain nutrition and avoid aspiration in this vulnerable patient population.10 Yet, feeding tube placement in patients with advanced dementia was not without controversy11 as emerging research began demonstrating the risks and unproven benefits12–14 of feeding tube placement in these patients, particularly in those with advanced disease.2,15 This research led to increased educational efforts including a Choosing Wisely initiative by the American Board of Internal Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine cautioning against the insertion of feeding tubes in persons with advanced dementia.16,17 While increased awareness17 has resulted in an overall decline in feeding tube placement in this patient population over time,18 feeding tubes continue to be inserted in patients with advanced dementia, particularly in the hospital setting.19–22

Although feeding tubes have been used to manage eating and swallowing difficulties in patients with dementia, surprisingly, no studies to date have characterized the prevalence of dysphagia among hospitalized patients with advanced dementia based on feeding tube status. The lack of dysphagia characterization across these patients highlights concerns feeding tubes are potentially being inserted in patients with advanced dementia without pre-existing swallowing difficulties but who are experiencing a functional decline secondary to infection and/or delirium. Further, approximately two-thirds of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia are placed during an acute hospital stay23 raising the question of whether these feeding tubes are inserted in response to dysphagia already evident before the hospitalization. Yet, the natural history of dysphagia before hospitalization among patients with advanced dementia who subsequently received a feeding tube has not been investigated in previous research. In the present study, we performed a secondary analysis of a national cohort of patients with advanced dementia with a nursing home stay before hospitalization to examine 1) pre-hospitalization dysphagia prevalence and 2) risk of feeding tube placement during hospitalization based on pre-existing dysphagia.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Sources

This was a retrospective cohort study of all NH residents with advanced dementia residing in Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) certified U.S. nursing facilities that were hospitalized between 2013 and 2017. For the present analysis, the starting year 2013 was chosen based on the implementation of the MDS 3.0 in late 2010.24 The ending year was based on the available data at the time of our analysis. Hospitalizations were first selected during that time period and eligible persons included those with a nursing home stay and advanced dementia documented on MDS assessment 120 days before that hospitalization. We examined the last assessment that was completed within this time frame meaning that assessment could have been conducted during a SNF stay or quarterly follow-up. Thus,the final sample consisted of long-stay patients and patients with a SNF stay who were readmitted to the hospital. The MDS is a comprehensive, standardized, and federally mandated assessment that is administered to residents in CMS-certified facilities within 14 days of admission to a facility, every 30 days thereafter, and upon discharge.25 The MDS 3.0 provides information on clinical conditions, cognition, overall functional status, and medications administered.

Study Sample

The study cohort consisted of persons with an hospitalization with pre-existing NH stay that documented 66 years of age and older with advanced dementia (as defined by a score of 2 or greater on the Cognitive Function Scale (CFS26), who were impaired in their activities of daily living (ADL) (as defined by the presence of 2 or more ADL-related variables on the MDS 3.0 assessment), and had a dementia diagnosis noted on the MDS 3.0. The CFS is a validated measure of cognition function created using MDS 3.0 items with a range of 1–4 (higher scores indicate worse cognitive function).26 ADLs are calculated using MDS 3.0 items on a 0–28 scale with higher scores representing more dependence.27 Individuals were excluded if they had evidence of feeding tube insertion in the 6 months before the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0 assessment, or were comatose according to the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0. It should be noted persons with a pre-existing feeding tube often had missing information on the dysphagia items. We also excluded individuals who had missing dysphagia variables on the MDS 3.0 assessment. This study was approved by the Brown University Institutional Review Board. Informed consent for a secondary analysis of these retrospective data was waived. In compliance with our funder’s Resource Sharing Policy, additional information about the codes used to create the dataset and analysis can be found in Brown’s Digital Repository at https://doi.org/10.26300/7869-rh96.

Study Measures

Presence of Pre-Hospitalization Dysphagia

Pre-hospitalization dysphagia status was assessed using MDS 3.0 items related to dysphagia: K0100A (swallowing disorder, loss of mouth eating), K0100B (swallowing disorder, holding food in mouth), K0100C (swallowing disorder, choke during meals), and K0100D (swallowing disorder, complaint swallowing). These categories broadly represent swallowing impairments in the oral (K0100A and K0100B) and pharyngeal phases (K0100C) of swallowing as well as general swallowing complaints/pain (K0100D). It should be noted that this section of the MDS is often completed by the nurse or dietitian rather than by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) during their assessment. Individuals were classified as having pre-hospitalization dysphagia if any of the K0100A-K0100D items were recorded on the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0 assessment.

Dysphagia Risk Variable

The number of assessment items indicating presence or absence of dysphagia for each NH resident were summed together to construct a dysphagia risk variable. This variable ranged from 0 (no dysphagia variables were present) to 6 (all four dysphagia variables (K0100A-K0100D) plus mechanically altered diet (K0500C) and weight loss (K0300) were present).

Feeding Tube Status

Individuals who were identified to have a pre-existing feeding tube were excluded from the present analysis so the risk of a new surgically placed feeding tube placement could be determined. It should be noted that MDS assessment documents nasal or surgically placed feeding tubes. A surgically placed feeding tube during hospitalization was defined from ICD-9 codes, ICD-10 codes, and CPT-4 procedure codes commonly used and verified by CMS as the standard codes that should be used by providers to bill for PEG insertions or surgically placed feeding tube.28–30 The codes used and their descriptions are included in Supplemental Table S1. Individuals who were identified to have a pre-existing feeding tube were excluded from the present analysis so the risk of a new surgically placed feeding tube placement could be determined.

Covariates

Demographic information, dual eligibility (i.e. persons who receive coverage for preventative and primary healthcare through Medicare and supplemental healthcare assistance for long-term services and supports and Medicare premiums through their state Medicaid program),31and Medicare Advantage status for each patient were identified from the Medicare Beneficiary Enrollment File. Comorbidities including pneumonia, diabetes, non-Alzheimer’s dementia, history of cerebral vascular accident, and other covariates such as septicemia, heart failure, and hip fracture were also derived from the MDS 3.0.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample, insertion of feeding tubes, and association of pre-existing dysphagia with the insertion of surgically placed feeding tube. To control for confounders, the association of pre-existing dysphagia risk factors with the insertion of a surgically placed feeding tube was examined with a multivariate random effects model. Given that the dependent variable was the insertion of a surgically or PEG-placed feeding tube, clustering was at the hospital level. Covariates included in the model were the following: age, sex, year of hospitalization, race, number of ADLs, CFS, dual eligibility, Medicare Advantage at admission, and comorbidities (pneumonia, diabetes, non-Alzheimer’s dementia, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), septicemia, heart failure, hip fracture, and weight loss.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

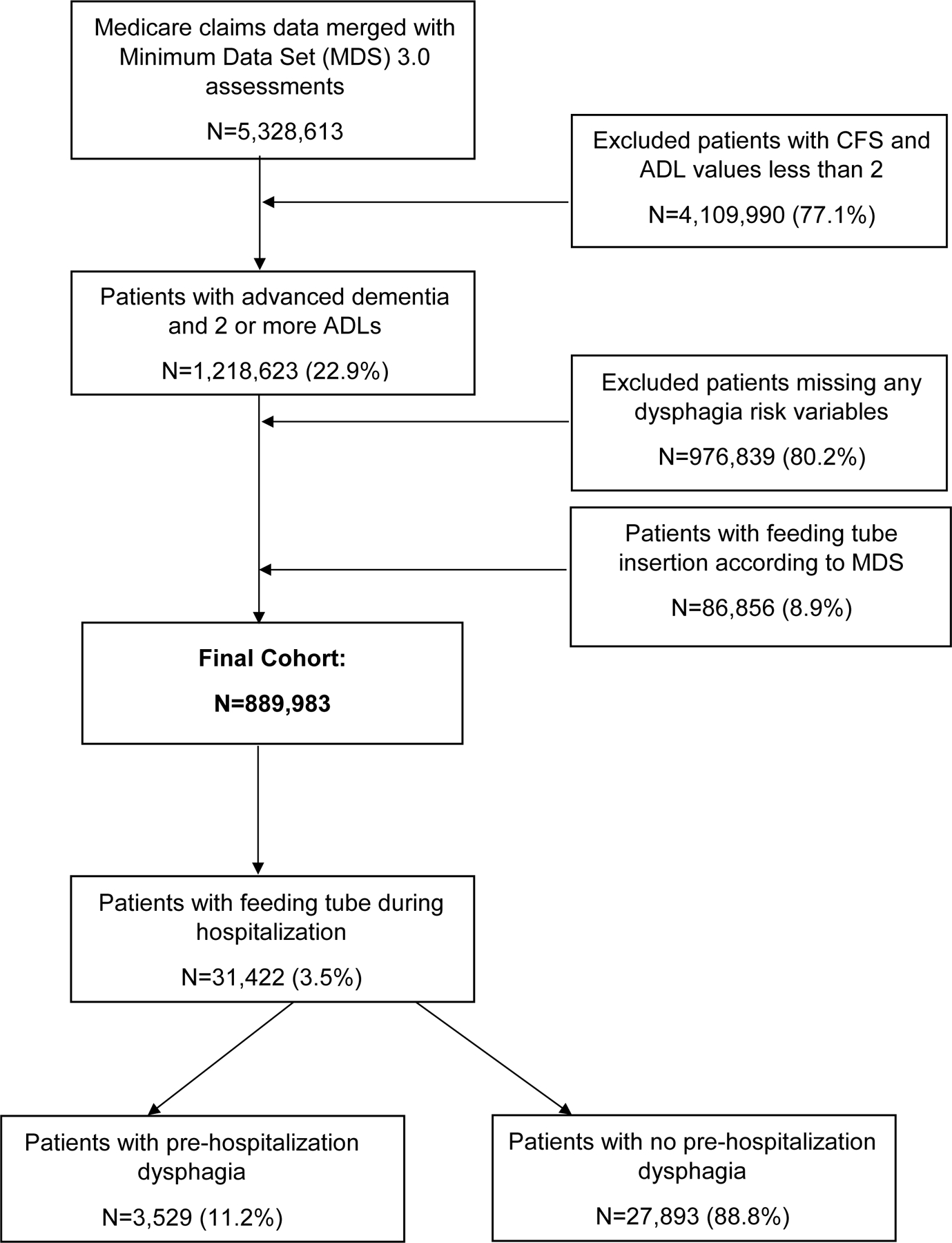

The process by which the final cohort was constructed is illustrated in Figure 1. After removing individuals with CFS and ADL values below 2, excluding individuals with missing dysphagia variables, individuals noted to be comatose on the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0 assessment and removing those with a feeding tube documented on the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0 assessment, the final cohort consisted of 889,983 patients. Demographics for the final cohort are overviewed in Table 1. The mean age of the cohort was 84.5 years (SD: 7.5) and 63.5% (n=565,503) were female.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram for construction of retrospective cohort.

Table 1:

Descriptive Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia with and without Pre-Hospitalization Dysphagia (N=889,983)

| Variables N (%) |

Pre-Hospitalization Dysphagia |

No Pre-Hospitalization Dysphagia | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||

| Overall N | 47,574 (5.3) | 842,409 (94.7) | |||

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Mean age (SD), y | 84.5 (7.6) | 84.5 (7.5) | |||

| Female | 27,171 (57.1) | 538,332 (63.9) | 0.74 | 0.77 | |

| Race | White | 37,453 (78.7) | 662,337 (78.6) | 0.98 | 1.03 |

| Black | 7,206 (15.2) | 130,260 (15.5) | 0.95 | 1.00 | |

| Hispanic | 1,261 (2.7) | 23,495 (2.8) | 0.89 | 1.00 | |

| Other | 1,654 (3.5) | 26,317 (3.1) | 1.06 | 1.17 | |

| Marital Status | Never Married (Reference) | 4,303 (9.2) | 81,697 (9.9) | ||

| Married | 14,650 (31.4) | 230,346 (27.9) | 1.17 | 1.25 | |

| Widowed | 22,735 (48.7) | 421,391 (50.9) | 0.99 | 1.06 | |

| Separated | 466 (1.0) | 9.007 (1.1) | 0.89 | 1.08 | |

| Divorced | 4,572 (9.8) | 84,053 (10.2) | 0.99 | 1.08 | |

| Medicare advantage | 6,335 (13.3) | 123,790 (14.7) | 0.87 | 0.92 | |

| ADL | 2 (Reference) | 884 (1.9) | 37,301 (4.4) | ||

| 3 | 1,335 (2.8) | 49,809 (5.9) | 1.04 | 1.23 | |

| 4 | 1,805 (3.8) | 54,138 (6.4) | 1.29 | 1.53 | |

| 5 | 4,686 (9.9) | 122,478 (14.5) | 1.50 | 1.74 | |

| 6 | 15,170 (31.9) | 329,963 (39.2) | 1.81 | 2.08 | |

| 7 | 23,694 (49.8) | 248,720 (29.5) | 3.75 | 4.30 | |

| CFS | 2 (Mild) (Reference) |

10,529 (22.1) | 246,216 (29.2) | ||

| 3 (Moderate) | 21,695 (45.6) | 393,051 (46.7) | 1.26 | 1.32 | |

| 4 (Severe) | 15,350 (32.3) | 203,142 (24.1) | 1.72 | 1.81 | |

| Weight loss | 7,875 (16.6) | 87,812 (10.5) | 1.66 | 1.75 | |

| Dehydration | 10,504 (22.1) | 162,423 (19.3) | 1.16 | 1.21 | |

| Pneumonia | 5,716 (12.0) | 50,951 (6.1) | 2.06 | 2.18 | |

| Respiratory failure | 1,546 (3.3) | 18,612 (2.2) | 1.41 | 1.57 | |

| UTI | 18,690 (39.3) | 314,529 (37.3) | 1.07 | 1.11 | |

| Septicemia | 1,341 (2.8) | 14,924 (1.8) | 1.52 | 1.70 | |

| Bowel obstruction | 1,429 (3.0) | 24,429 (2.9) | 0.98 | 1.09 | |

| Stroke | 9,773 (20.5) | 125,545 (14.9) | 1.44 | 1.51 | |

| Care characteristics | |||||

| Hospice care | 565 (1.2) | 7,694 (0.9) | 1.19 | 1.42 | |

| Any days in ICU during index admission | 2,332 (6.5) | 38,736 (6.0) | 1.04 | 1.14 | |

| Intubation during admission | 350 (0.7) | 6,305 (0.8) | 0.88 | 1.09 | |

| Surgery DRG | 5,121 (10.8) | 121,471 (14.4) | 0.69 | 0.74 | |

Within the cohort, 47,574 (5.4%) patients had pre-hospitalization dysphagia according to MDS 3.0 items. The prevalence of individual dysphagia-related items among those who did and did not receive a PEG feeding tube is presented in Table 2. Among those with pre-existing dysphagia documented on MDS assessment conducted before hospitalization, 21,438 (45.1%) had oral dysphagia, 24,257 (50.1%) had pharyngeal dysphagia, and 14,928 (31.4%) had general swallowing complaints/pain. Oral dysphagia was characterized by a loss of liquid from the mouth (n=7,182; 33.5%) and holding food in the mouth (n=14,256; 66.5%). 37,401 (78.6%) had 1 dysphagia variable present while 10,173 (21.4%) had 2 or more dysphagia variables present (Table 3).

Table 2:

Dysphagia Items Documented on the Pre-Hospitalization MDS 3.0 Assessment Among Nursing Home Residents Who Did and Did Not Receive Feeding Tubes (N=889,983).

| Dysphagia Items | Feeding Tube N (%) |

No Feeding Tube N (%) |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI (Lower-Upper) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of liquid/food | Yes | 728 (0.1%) |

6,454 (0.7%) |

3.1 | 2.9–3.4 |

| No | 30,694 (3.5%) |

852,107 (95.7%) |

|||

| Holding food in mouth | Yes | 1,290 (0.1%) |

12,966 (1.5%) |

2.8 | 2.6–2.9 |

| No | 30,132 (3.4%) |

845,595 (95.0%) |

|||

| Coughing/ choking | Yes | 1,693 (0.2%) |

22,564 (2.5%) |

2.1 | 2.0–2.2 |

| No | 29,729 (3.3%) |

835,997 (93.9%) |

|||

| Difficulty swallowing and/or pain | Yes | 1,050 (0.1%) |

13,878 (1.6%) |

2.1 | 1.9–2.2 |

| No | 30,372 (3.4%) |

844,683 (94.9%) |

|||

Table 3:

Dysphagia Risk Variables on Pre-Hospitalization MDS 3.0 Assessment and Risk of Feeding Tube Placement during Hospitalization

| Dysphagia Variable | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Wald Confidence Limits |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk variable 1 vs 0 (N=37,401) |

2.183 | 2.095 | 2.276 |

| Risk variable 2 vs 0 (N=7,785) |

2.759 | 2.547 | 2.989 |

| Risk variable 3 vs 0 (N=1,900) |

3.532 | 3.054 | 4.085 |

| Risk variable 4 vs 0 (N=52) |

1.788 | 0.557 | 5.736 |

| Risk variable 5 vs 0 (N=334) |

2.988 | 2.064 | 4.324 |

| Risk variable 6 vs 0 (N=102) |

5.434 | 3.187 | 9.266 |

Before hospitalization, 86,856 (8.9%) of patients within the cohort had a feeding tube placed. Among the remaining 889,983 (91.1%) patients with no pre-hospitalization feeding tube placement, 31,422 (3.5%) had a PEG feeding tube placed during the hospital stay. Of those with a feeding tube inserted, 3,529 (11.2%) had pre-hospitalization dysphagia. Feeding tubes were inserted during hospitalization in 2,018 (57.1%) with oral dysphagia, 1,693 (47.9%) with pharyngeal dysphagia, and 1,050 (29.7%) with general swallowing complaints/pain.

Feeding tubes were inserted in 27,893 (88.8%) patients despite not having pre-hospitalization dysphagia. Those with new PEG feeding tube placement and no pre-hospitalization dysphagia were noted to have an increased frequency of weight loss (N=5,700, 18.4% vs. N=983, 3.1%, p<0.0001) and intensive care unit time during hospitalization (M: 3.7 days, SD: 6.4 vs. M: 2.9 days, SD: 5.5, p<0.0001) as compared to those with new feeding tube placement and pre-hospitalization dysphagia.

Pre-Hospitalization Dysphagia and Feeding Tube Placement Risk

Pre-hospitalization dysphagia was associated with an odds risk (OR) of 2.3 (95% CI: 2.3–2.4) and increased risk of new feeding tube placement during the hospital admission. The odds of new feeding tube placement by individual MDS 3.0 dysphagia items are included in Table 2. A loss of liquid from the mouth, indicative of oral dysphagia, was the pre-hospitalization dysphagia item associated with the greatest odds of new feeding tube placement (OR 3.1; 95% CI: 2.9–3.4). The OR of feeding tube placement in those with at least one pre-hospitalization dysphagia variable was 2.2 (95% CI: 2.1–2.3) times greater than those without any pre-hospitalization dysphagia variables. The OR of feeding tube placement was 5.4 (95% CI: 3.2–9.3) times higher in patients with all 6 indicators of dysphagia versus those without pre-hospitalization dysphagia variables (Table 3).

Results from the multivariate random effects model are presented in Table 4. Increased risk of feeding tube placement was noted among those who were Black (adjusted odds risk, AOR: 1.21, CI: 1.14–1.28), had a higher number (7 vs. 2) of ADL dependencies (AOR: 1.13, CI: 1.01–1.27), greater severity of cognitive impairment (CFS score 4 vs. 2; AOR: 1.33, CI: 1.28–1.38), or were on a mechanically altered diet (AOR: 2.75, CI: 2.68–2.83).

Table 4.

Multivariate Random Effects Model Examining Association of Dysphagia Risk Factors with Feeding Tube Placement During Hospitalization

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

|||

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Dual Eligible at Admission Date | 1.0449 | 1.0156 | 1.0751 | |

| Medicare Advantage at Admission | 1.1748 | 1.1357 | 1.2153 | |

| Age | 0.9802 | 0.9787 | 0.9817 | |

| Female vs. Male | 0.8517 | 0.8313 | 0.8727 | |

| Race | White vs. Other | 0.6740 | 0.6366 | 0.7135 |

| African American | 1.2067 | 1.1371 | 1.2805 | |

| Hispanic | 0.8618 | 0.7974 | 0.9313 | |

| Number of ADL Dependencies | 3 vs. 2 | 1.1305 | 1.0065 | 1.2698 |

| 4 vs. 2 | 1.1819 | 1.0555 | 1.3233 | |

| 5 vs. 2 | 1.2622 | 1.1413 | 1.3958 | |

| 6 vs. 2 | 1.5321 | 1.3943 | 1.6835 | |

| 7 vs. 2 | 2.5035 | 2.2801 | 2.7487 | |

| CFS | 3 vs. 2 | 1.2170 | 1.1768 | 1.2585 |

| 4 vs. 2 | 1.3274 | 1.2805 | 1.3762 | |

| Year of Hospital Admission | 2014 vs. 2013 | 0.9661 | 0.9340 | 0.9993 |

| 2015 vs. 2013 | 0.8576 | 0.8280 | 0.8882 | |

| 2016 vs. 2013 | 0.7994 | 0.7707 | 0.8291 | |

| 2017 vs. 2013 | 0.7650 | 0.7366 | 0.7944 | |

| MDS 3.0 Dysphagia Items | Loss of Liquid/Food | 1.3840 | 1.2655 | 1.5137 |

| Holding Food in Mouth | 1.3779 | 1.2870 | 1.4752 | |

| Coughing/Choking | 1.3607 | 1.2848 | 1.4411 | |

| General Swallowing Complaints/Pain | 1.1996 | 1.1212 | 1.2835 | |

| Weight Loss | 1.9175 | 1.8625 | 1.9742 | |

| Mechanically Altered Diet | 2.7509 | 2.6783 | 2.8254 | |

| Surgery DRG | 1.0910 | 1.0542 | 1.1291 | |

| Heart Failure | 0.7985 | 0.7752 | 0.8225 | |

| Pneumonia | 1.0014 | 0.9570 | 1.0479 | |

| Septicemia | 0.9084 | 0.8405 | 0.9817 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 0.9059 | 0.8839 | 0.9285 | |

| Hip Fracture | 0.8965 | 0.8446 | 0.9515 | |

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 1.0170 | 0.9801 | 1.0553 | |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 1.0282 | 0.9984 | 1.0588 | |

| Non-Alzheimer’s Dementia | 1.0521 | 1.0046 | 1.1019 | |

Discussion

Feeding tube insertion in persons with advanced dementia is without evidence of improved survival or healing of pressure ulcers.32 The natural history of dysphagia before feeding tube placement within this patient population has yet to be examined. We conducted a secondary analysis of a national, retrospective cohort of nursing home residents with advanced dementia to characterize pre-hospitalization dysphagia status and examine the association between pre-existing dysphagia and new feeding tube placement during hospitalization. Importantly, while dysphagia may lead to feeding tube placement, in our cohort we found that 89% of feeding tubes inserted during hospitalization were in patients with no pre-existing dysphagia according to MDS 3.0 items. This raises the critical question of whether this inadequate assessment of dysphagia on the MDS or newly acquired dysphagia, which is potentially from an infection that results in a decline in function that may be reversible.

While the association between dysphagia and feeding tube placement in patients with dementia has been investigated previously,33 the prevalence of pre-existing dysphagia among patients that receive a feeding tube during hospitalization has not been examined. In the current study, we found pre-hospitalization dysphagia prevalence among the entire cohort was relatively low given the previously published ranges of 7–93%.34,35 These contrasting findings may be due to methodological differences in how dysphagia was determined across studies. When examining dysphagia presence using clinical assessment methods (e.g. questionnaires, observation of mealtimes), the prevalence of dysphagia has been found to range from 32%–45% in dementia; whereas, the range of dysphagia prevalence determined using instrumental diagnostic methods (e.g. videofluoroscopic swallowing study) is higher (84%–93%).35,36 In the current study, dysphagia was classified using the MDS 3.0 assessment which broadly categorizes dysphagia based on swallowing difficulties (e.g. coughing/choking) that are observed by the nurse or nursing aid during mealtimes. Given the broad nature of dysphagia-related MDS 3.0 items combined with the possibility that certain eating problems may not have been observed during a particular mealtime, pre-hospitalization dysphagia prevalence in the current study may have been underreported.

Among those with a feeding tube inserted, the prevalence of oral and pharyngeal dysphagia symptoms documented on the pre-hospitalization MDS 3.0 assessment were relatively similar. Historically, feeding tubes were used in patients with dementia because of long-held beliefs that they could help sustain nutrition when patients had oral and pharyngeal swallowing symptoms such as declining oral intake and aspiration. Yet, these beliefs have been challenged and questioned by the body of literature examining the benefits and safety of feeding tube placement in persons with dementia.17,37–40 This research has found feeding tube placement in persons with dementia does not have a nutritional benefit or prolong survival but may result in negative effects such as increased healthcare utilization, increased risk of pressure ulcers, and higher overall healthcare costs.12,13,41 In addition, aspiration risk is not prevented with the use of feeding tubes as reflux of stomach content to the lungs can still occur and saliva continues to be aspirated.42 Prior research has even found the incidence of aspiration pneumonia to be almost twice as high among patients with dementia with feeding tube insertion.43 The questionable utility of feeding tube placement to alleviate oral and pharyngeal dysphagia underscores the continued need to identify more beneficial and less harmful approaches to managing nutritional and eating concerns in persons with advanced dementia.

The results of the current study may provide insights into clinical decision-making surrounding feeding tube placement in patients with dementia. Increased risk of feeding tube placement was observed in those with greater cognitive impairment and ADL dependence, suggesting these patients were at more advanced stages of the disease. Despite mounting evidence suggesting otherwise,17,39,42,43 two recent surveys conducted assessing physician knowledge of feeding tubes found that >56% disagreed PEG tubes were contraindicated in patients with dementia; 62% believed that feeding tubes prevented aspiration; and 52% thought feeding tubes prevented pneumonia.44,45 Therefore, healthcare providers may be continuing to place feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia due to continued knowledge gaps regarding their clinical benefit.

Black patients with dementia were at an increased risk of feeding tube placement, highlighting a potential health disparity. Our findings are well-aligned with prior investigations noting increased feeding tube placement among Black patients with dementia as compared to White patients,18,46 although the overall insertion rate declined over time.18 Black and White proxy participants in a recent study expressed a preference for feeding tubes, with one participant stating “whatever we need to do to keep him alive”.47 On the other hand, White participants in the study preferred comfort measures and expressed not wanting any “heroic measures”.47 NH features and their influence on deciding whether to place a feeding tube were investigated in a qualitative study.14 Healthcare providers at a high-use facility (i.e. an area where feeding tubes were frequently placed) implicitly believed African Americans preferred aggressive care, including feeding tubes, at the end of their lives.14 Assumptions such as this may be related to the finding that Black people with dementia tend to have less advanced care planning, which may result in high-intensity care (e.g. hospitalizations) being administered at the end of their lives.48–50 Overall, these findings suggest that Black patients and their caregivers could benefit from additional support and resources, including discussions regarding the unproven benefits of feeding tubes to prolong survival and maintain nutrition, when faced with the decision to insert a feeding tube.

Although dysphagia is a risk factor for PEG feeding tube placement, in the present study the majority of feeding tubes were placed in patients with no prior dysphagia documented on an MDS assessment prior to that hospitalization. The continued practice of feeding tube placement in patients with advanced dementia calls into question which factors healthcare providers consider that may lead to feeding tube insertion. Hospitalized patients with cognitive impairment are noted to be at an increased risk of experiencing functional decline during hospitalization that may lead to adverse outcomes including declines in nutritional status, reduced cognitive and physical functioning, dehydration, new infections, and death.51,52 Further, patients with advanced dementia are noted to have increased incontinence, and eating difficulties that can result in aspiration, immobility, and decreased immune responses – all of which may contribute to intercurrent illnesses such as urinary tract infections, respiratory infections, and pressure ulcers.53–55 Thus, it might be that feeding tube placement is initiated in response to functional decline or intercurrent illness incurred during the course of hospitalization. Given that some of these negative health outcomes (e.g. infections) may improve over time, healthcare providers should consider whether alternatives to feeding tubes can address a temporary decline in nutritional status and function.

The possibility that feeding tubes are inserted in response to acute dysphagia that may resolve underscores a need to better understand if short-term alternatives can be used for nutritional management in this patient population. Consultation with a SLP will afford the opportunity to evaluate the patient’s swallowing and functional status. The SLP, along with the rest of the care team can implement other solutions such as environmental modifications to support patients with dementia during mealtimes. Examples of environmental modifications were previously overviewed56,57 and may include: improving lighting and visual contrast in the dining room, reduce environmental noise to avoid auditory confusion, create opportunities for social interaction during mealtimes, tailor dining care to patient needs and using skills (e.g. tactile cues) to address refusal to eat. Still, while these approaches can help alleviate symptoms in the short term, they are compensatory in nature and are insufficient to facilitate long-term improvements and maintenance of swallowing function. In addition, approaches to dysphagia management among patients with dementia have been largely reactive in nature, occurring well after dysphagia symptoms are present. Emerging research has questioned whether patients with dementia may benefit from a proactive approach to dysphagia where active, rehabilitative intervention targeting the swallowing musculature is initiated early in the disease course.3 Given the ineffectiveness of feeding tubes combined with the limitations of compensatory dysphagia management approaches in the long-term highlights a need to explore the feasibility and efficacy of proactive dysphagia interventions to manage nutritional concerns during hospitalization.

Study Limitations

There are important limitations that need to be acknowledged in the interpretation of the study results. The characterization of swallowing impairments using the MDS 3.0 relies on clinical observations by nursing staff which may be inaccurate. A prior investigation found that overall, interrater reliability of MDS 3.0 items was excellent or very good and across key areas of functional status such as cognition and ADLs, interrater reliability was higher than what was previously reported for the 2.0 version of the MDS.58 However, without visualization of the swallowing mechanism and quantification of swallowing function through instrumental diagnostic methods (e.g. videofluoroscopy), it is difficult to confirm the presence or absence of dysphagia. In the current analysis, we were unable to account for physician/staff attitudes regarding feeding tube placement to understand how these healthcare professionals arrived at the decision to insert a feeding tube. Our study was also unable to capture the conversations that took place among healthcare professionals, the patient, and their care partners discussing the possibility of feeding tube placement. We also recognize that our findings may relate to broader healthcare system issues such as feeding tubes being placed in response to patients without feeding assistance during meals due to staffing shortages, time constraints, etc. Future research incorporating patient/provider perspectives and broader system factors could help improve our understanding as to why the questionable practice of feeding tube insertion among patients with advanced dementia continues to persist. Ascertainment bias is an important limitation. Future work needs to focus on validating the MDS 3.0 against VFS or other swallowing metrics to improve our understanding of this method’s clinical utility and reliability for capturing dysphagia. However, a strength of our study is that it is a national study representing the current use of the MDS assessment that has raised an important question regarding feeding tube placement in persons with dementia during hospitalization: namely, whether watchful waiting with dysphagia rehabilitation could allow persons to avoid surgically or PEG placed feeding tubes. Future research is needed to examine the risks and benefits of feeding tube placement in persons who develop dysphagia during hospitalization, especially in persons with delirium or intercurrent infection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this retrospective cohort of patients with advanced dementia, pre-hospitalization dysphagia was associated with substantially increased odds of feeding tube placement and the risk of feeding tube placement increased with a greater number of dysphagia risk indicators on the MDS assessment before that hospitalization. However, most new feeding tubes were placed in patients without documented dysphagia before hospitalization. Future research investigating proactive alternatives to dysphagia in NH residents with advanced dementia and feasible ways to implement these approaches in the acute care setting is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Impact Statement:

We certify that this work is novel and adds new information to the documentation of pre-existing dysphagia in hospitalized persons with a NH stay and the new insertion of a feeding tube in persons with advanced dementia. Specifically, while prior research has highlighted that feeding tubes are largely ineffective at mitigating the effects of swallowing dysfunction in this patient population, no studies have examined the presence of dysphagia among patients with advanced dementia that do and do not receive a feeding tube.

KEY POINTS.

Prior research provides evidence that percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tubes are not associated with improved outcomes. Yet, the natural history of pre-existing dysphagia documented in a nursing home assessment before hospitalization has not been examined.

In this national retrospective cohort of 889,983 persons with nursing home stay, advanced dementia, and MDS 3.0 assessment completed within 120 days before hospitalization, pre-hospitalization dysphagia was documented in 47,574 (5.4%) patients.

Among 31,422 (3.5%) with PEG feeding tube inserted during that hospitalization, 3,529 (11.2%) had pre-existing dysphagia documented in an MDS Assessment and 27,893 (88.8%) did not have documentation of pre-existing dysphagia. Future research is needed to understand whether this new dysphagia results in PEG feeding tube insertion or inadequate assessment of dysphagia during a nursing home stay.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

While dysphagia is a risk factor for feeding tube placement, no research has investigated the natural history of dysphagia among patients with advanced dementia who are hospitalized. This knowledge gap raises the possibility feeding tubes are inserted in some individuals without dysphagia, but instead, temporary reduction in function secondary to an infection.

Acknowledgments:

Sponsor’s Role:

The funding organizations were not involved in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Financial Support:

Some authors are VA employees (J.L.R., and N.M.R-P). The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or official policies of the United States Government or the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work was also partially supported by the William S. Middleton Veteran Affairs Hospital, Madison, WI (Dr. Rogus-Pulia, GRECC Manuscript 007–2023); and the National Institute on Aging (8K00AG076123–03 to Dr. Robison; and 1K76AG068590 to Dr. Rogus-Pulia). Drs. Robison, Rudolph, Rogus-Pulia, and Teno have also received salary support from NIA P01AG027296.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures:

Dr. Nicole Rogus-Pulia presented findings from the current study during the 2022 American Geriatrics Society annual meeting poster session. Dr. Joan Teno is an investigator on a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services contract on CAHPS Hospice Survey and a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation contract evaluating the VBID Hospice Carve that are not associated with the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1.2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2023;19(4):1598–1695. doi: 10.1002/alz.13016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361(16):1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogus-Pulia NM, Plowman EK. Shifting Tides Toward a Proactive Patient-Centered Approach in Dysphagia Management of Neurodegenerative Disease. Am J speech-language Pathol 2020;29(2S):1094–1109. doi: 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humbert IA, McLaren DG, Kosmatka K, et al. Early deficits in cortical control of swallowing in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2010;19(4):1185–1197. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mira A, Gonçalves R, Rodrigues IT. Dysphagia in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Dement Neuropsychol 2022;16(3):261–269. doi: 10.1590/1980-5764-DN-2021-0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janbek J, Frimodt-Møller N, Laursen TM, Waldemar G. Dementia identified as a risk factor for infection-related hospital contacts in a national, population-based and longitudinal matched-cohort study. Nat Aging. 2021;1(2):226–233. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toot S, Devine M, Akporobaro A, Orrell M. Causes of Hospital Admission for People With Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14(7):463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Büla CJ, Ghilardi G, Wietlisbach V, Petignat C, Francioli P. Infections and Functional Impairment in Nursing Home Residents: A Reciprocal Relationship. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52(5):700–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brogan E, Langdon C, Brookes K, Budgeon C, Blacker D. Dysphagia and factors associated with respiratory infections in the first week post stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43(2):140–144. doi: 10.1159/000366423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervo FA, Bryan L, Farber S. To PEG or not to PEG: a review of evidence for placing feeding tubes in advanced dementia and the decision-making process. Geriatrics. 2006;61(6):30–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch MC. Is tube feeding futile in advanced dementia? Linacre Q 2016;83(3):283–307. doi: 10.1080/00243639.2016.1211879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hwang D, Teno JM, Gozalo P, Mitchell S. Feeding tubes and health costs postinsertion in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(6):1116–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Gozalo PL, et al. Hospital characteristics associated with feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA 2010;303(6):544–550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez RP, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(1):83–88. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Candy B, Sampson EL, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding in older people with advanced dementia: findings from a Cochrane systematic review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2009;15(8):396–404. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2009.15.8.43799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Promoting conversations between providers and patients. Geriatrics - Feed patients with dementia by hand. Choosing Wisely. Published 2012. https://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/feeding-tubes-for-people-with-alzheimers/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Committee AGSEC and CP and M of C. American Geriatrics Society Feeding Tubes in Advanced Dementia Position Statement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(8):1590–1593. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SL, Mor V, Gozalo PL, Servadio JL, Teno JM. Tube Feeding in US Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia, 2000–2014. JAMA 2016;316(7):769–770. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ijaopo EO, Ijaopo RO. Tube Feeding in Individuals with Advanced Dementia: A Review of Its Burdens and Perceived Benefits. J Aging Res 2019;2019:7272067. doi: 10.1155/2019/7272067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz DB. Enteral nutrition and dementia integrating ethics. Nutr Clin Pract 2018;33(3):377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorrell JM. Use of feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia: are we doing harm? J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2010;48(5):15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DS, Jones RN, Shireman TI, Kluger BM, Friedman JH, Akbar U. Trends and outcomes associated with gastrostomy tube placement in common neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Park Relat Disord 2021;4:100088. doi: 10.1016/j.prdoa.2020.100088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo S, Rhodes RL, Mitchell SL, Mor V, Teno JM. Natural history of feeding-tube use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2009;10(4):264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin CM. Getting ready for MDS 3.0: patient evaluation takes a new turn. Consult Pharm J Am Soc Consult Pharm 2010;25(7):404–406,411–415. doi: 10.4140/TCP.n.2010.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, Buchanan J. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13(7):595–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68–e72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. Journals Gerontol Ser A 1999;54(11):M546–M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Brody JA. Gastrostomy Placement and Mortality Among Hospitalized Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA 1998;279(24):1973–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.24.1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun UK, Rabeneck L, McCullough LB, et al. Decreasing use of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube feeding for veterans with dementia-racial differences remain. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53(2):242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53109.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis CL, Cox CE, Garrett JM, et al. Trends in the use of feeding tubes in North Carolina hospitals. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19(10):1034–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30071.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. People Dually Eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Published 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-medicaid-coordination/medicare-and-medicaid-coordination/medicare-medicaid-coordination-office/downloads/mmco_factsheet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teno JM, Gozalo P, Mitchell SL, Kuo S, Fulton AT, Mor V. Feeding tubes and the prevention or healing of pressure ulcers. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(9):697–701. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg LS, Altman KW. The role of gastrostomy tube placement in advanced dementia with dysphagia: a critical review. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1733–1739. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S53153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S, Gustafson S, Deckelman C, et al. Dysphagia Profiles Among Inpatients with Dementia Referred for Swallow Evaluation. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2022;89(1):351–358. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Affoo RH, Foley N, Rosenbek J, Kevin Shoemaker J, Martin RE. Swallowing Dysfunction and Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Scoping Review of the Evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61(12):2203–2213. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espinosa-Val MC, Martín-Martínez A, Graupera M, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Complications of Oropharyngeal Dysphagia in Older Patients with Dementia. Nutrients. 2020;12(3). doi: 10.3390/nu12030863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders DS, Carter MJ, D’Silva J, James G, Bolton RP, Bardhan KD. Survival analysis in percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding: a worse outcome in patients with dementia. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95(6):1472–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(4):594–599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Mitchell SL, et al. Does feeding tube insertion and its timing improve survival? J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60(10):1918–1921. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04148.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Lipsitz LA. The risk factors and impact on survival of feeding tube placement in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Arch Intern Med 1997;157(3):327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampson EL, Candy B, Jones L. Enteral tube feeding for older people with advanced dementia. Cochrane database Syst Rev 2009;2009(2):CD007209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007209.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider PL, Fruchtman C, Indenbaum J, Neuman E, Wilson C, Keville T. Ethical Considerations Concerning Use of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Feeding Tubes in Patients With Advanced Dementia. Perm J 2021;25. doi: 10.7812/TPP/20.302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cintra MTG, de Rezende NA, de Moraes EN, Cunha LCM, da Gama Torres HO. A comparison of survival, pneumonia, and hospitalization in patients with advanced dementia and dysphagia receiving either oral or enteral nutrition. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18(10):894–899. doi: 10.1007/s12603-014-0487-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Punchik B, Komissarov E, Zeldez V, Freud T, Samson T, Press Y. Doctors’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Enteral Feeding and Eating Problems in Advanced Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2018;8(2):268–276. doi: 10.1159/000489489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fessler TA, Short TB, Willcutts KF, Sawyer RG. Physician opinions on decision making for percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube placement. Surg Endosc 2019;33(12):4089–4097. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06711-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henao D, Gregory C, Walters G, Stinson C, Dixon Y. Race and prevalence of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes in patients with advanced dementia. Palliat Support Care. Published online January 2022:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521002042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCarthy EP, Lopez RP, Hendricksen M, et al. Black and white proxy experiences and perceptions that influence advanced dementia care in nursing homes: The ADVANCE study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023;71(6):1759–1772. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ornstein KA, Zhu CW, Bollens-Lund E, et al. Medicare Expenditures and Health Care Utilization in a Multiethnic Community-based Population With Dementia From Incidence to Death. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2018;32(4):320–325. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aranda MP, Kremer IN, Hinton L, et al. Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(7):1774–1783. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byhoff E, Harris JA, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life medicare expenditures. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64(9):1789–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geyskens L, Jeuris A, Deschodt M, Van Grootven B, Gielen E, Flamaing J. Patient-related risk factors for in-hospital functional decline in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2022;51(2). doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fogg C, Griffiths P, Meredith P, Bridges J. Hospital outcomes of older people with cognitive impairment: An integrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(9):1177–1197. doi: 10.1002/gps.4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahluwalia N, Vellas B. Immunologic and inflammatory mediators and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Immunol Allergy Clin 2003;23(1):103–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perls TT, Herget M. Higher respiratory infection rates on an Alzheimer’s special care unit and successful intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43(12):1341–1344. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Volicer L End-of-life care for people with dementia in long- term care settings. Alzheimers care today. 2008;9(2):84–102. doi: 10.1097/01.ALCAT.0000317191.05451.81 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faraday J, Abley C, Beyer F, Exley C, Moynihan P, Patterson JM. How do we provide good mealtime care for people with dementia living in care homes? A systematic review of carer-resident interactions. Dementia. 2021;20(8):3006–3031. doi: 10.1177/14713012211002041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brush JA, Calkins MP. Environmental Interventions and Dementia. ASHA Lead. 2008;13(8):24–25. doi: 10.1044/leader.FTR4.13082008.24 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saliba D, Buchanan J. Making the investment count: revision of the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes, MDS 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012;13(7):602–610. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.