Abstract

Bispecific agents are a rapidly growing class of cancer therapeutics, and immune targeted bispecific agents have the potential to expand functionality well beyond monoclonal antibody agents. Humabodies⁎ are fully human single domain antibodies that can be linked in a modular fashion to form multispecific therapeutics. However, the effect of heterogeneous delivery on the efficacy of crosslinking bispecific agents is currently unclear. In this work, we utilize a PSMA-CD137 Humabody with an albumin binding half-life extension (HLE) domain to determine the impact of tissue penetration on T cell activating bispecific agents. Using heterotypic spheroids, we demonstrate that increased tissue penetration results in higher T cell activation at sub-saturating concentrations. Next, we tested the effect of two different albumin binding moieties on tissue distribution using albumin-specific HLE domains with varying affinities for albumin and a non-specific lipophilic dye. The results show that a specific binding mechanism to albumin does not influence tissue penetration, but a non-specific mechanism reduced both spheroid uptake and distribution in the presence of albumin. These results highlight the potential importance of tissue penetration on bispecific agent efficacy and describe how the design parameters including albumin-binding domains can be selected to maximize the efficacy of bispecific agents.

Keywords: Bispecific antibodies, Tumoral distribution, T-cell activating agents, Single domain antibodies, Heterotypic spheroids

Introduction

Bispecific agents have contributed to recent breakthroughs in immunotherapy, with over 100 bispecific agents currently in the clinical pipeline and nine FDA approvals for solid and hematological malignancies in cancer with two approved in 2023 [1]. Bispecific agents can take a variety of formats and functionalities, creating the opportunity to customize therapeutics for a specific application [2,3]. These applications include binding multiple antigens on the same cell to increase the selectivity of binding a particular cell type only when both targets are present or cross-linking antigens on two different cells to stimulate a desired response. With cellular cross-linking strategies to cluster receptors on an immune cell, binding both a tumor associated target and an immune associated target is required to cluster the receptors in the synapse and activate T cells. Cross-linking occurs only when these cells are in close proximity, which can decrease off-tumor activity and toxicity, which is a common hinderance for immune cell targeted antibodies [4].

One such crosslinking strategy targets the T-cell activation receptor CD137 (4-1BB). CD137 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) and has emerged as an attractive target for immunotherapy. This receptor provides co-stimulatory signals for CD8+ T cells, contributes to T cell proliferation, and increases the formation of memory T cells that are important in generating durable responses [5]. Intracellular signaling is normally activated after three CD137 monomers interact with a CD137L trimer, triggering the initiation of higher-order structures to activate intracellular signalling [6,7]. Because of its desirable properties, multiple CD137 targeted antibodies have advanced to the clinic, but these have so far proven unsuccessful. Antibodies such as urelumab have faced dose-limiting hepato-toxicities, [8] while the less potent utomilumab reduced toxicity but had poor clinical response rates as a monotherapy [9]. Bispecific formats with a tumor associated antigen (TAA) and T cell target have the potential to address these tolerability and efficacy limitations through greater tumor specificity.

Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a TAA that is over-expressed by a majority of prostatic adenocarcinomas, and it has been linked to worse disease prognosis and outcomes [10,11]. Previously, PSMA-targeted protein drug conjugates comprised of a fully human, variable heavy (VH) domains (Humabodies) linked to an albumin-binding half-life extension (HLE) domain were developed to deliver cytotoxic payloads to PSMA-expressing cancer cells [12]. Owing to their low molecular weight (30–45 kDa) and faster diffusion compared to a 150 kDa antibody, they showed improved tissue penetration, and thus efficacy, similar to other ADCs [13], [14], [15]. Improved tissue penetration has been linked to efficacy for ADCs and other immunotherapies, such as an IL-12 immunocytokine [16], but the impact on other protein therapeutics including bispecifics is less clear. CB307 is a clinical-stage bispecific Humabody that binds PSMA and CD137, induces immune cell activation, cytokine release, and killing, and can reduce tumor growth in syngeneic models of cancer [17]. In this work, we used variants of this agent to test the impact of tissue penetration and albumin binding on the crosslinking ability/activation of these PSMA-CD137 Humabodies.

Low molecular weight proteins are commonly used to improve tissue penetration of biologics by achieving faster diffusion than monoclonal antibodies [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. However, these scaffolds tend to fall below the renal filtration limit (∼60 kDa), which can result in fast plasma clearance with short half-lives in vivo [23]. Several strategies to address this challenge, such as PEGylation to increase the therapeutic molecular weight or half-life extension (HLE) domains that bind to albumin, have been used [21,24,25]. Albumin is the most abundant protein in the blood (∼600 µM) and has a half-life in circulation of approximately 3 weeks owing to its ability to undergo FcRn recycling and avoid renal clearance [26]. Albumin-binding protein domains, albumin fusions, and small molecule albumin binding agents, made possible by hydrophobic pockets on albumin, have therefore been used to increase the half-life and improve tumor uptake [12,21] of several drug classes including small molecules, DARPins, and nanoparticles [27,25,28]. The relationship between binding affinity to albumin and serum half-life has been explored previously, showing a surprisingly wide range of affinities able to extend the half-life (e.g. ∼2 nM to ∼300 nM Kd showing similar clearance, a 62 µM binder with improved circulation time, [29] and generally higher affinity correlating with slower clearance [30]). However, the potential impact of albumin binding on tissue penetration for both specific (e.g. albumin-binding antibody domains) and non-specific (e.g. lipophilic tags) moieties is less understood.

Here, we first determined the relationship between tissue penetration of bispecific Humabodies and T cell activation in a heterotypic spheroid model. The PSMA-CD137 targeted Humabodies [31] are comprised of three variable heavy (VH) domains, including a mouse serum albumin (MSA) or human serum albumin (HSA) binding domain with different albumin affinities (50 nM and 8 nM Kd to MSA and HSA, respectively). We then determined how different mechanisms of albumin binding impact tissue penetration, including a specific and non-specific binding mechanism. These results can be used to guide the complex design of bispecific agents, immunotherapies, and half-life extended drugs.

Methods

Cell lines and animals

The DU145 cell line transfected with PSMA (DU145T) was generated by Crescendo Biologics as previously described [32]. The 22Rv1 cell line was purchased from ATCC. Both cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 media with L-Glutamine, supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % Penicillin/streptomycin (%v/v). DU145T cells were dissociated using accutase, and both cell lines were passaged 2–3 times per week up to passage 50. 4-1BB Effector cells were purchased from Promega and passaged according to manufacturer's instructions. Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media with HEPES, and supplemented with 10 % FBS, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 800 ug/mL G418 sulfate solution, and 500 ug/mL hygromycin B. Cells were passaged every 2–3 days to maintain a concentration of 600,000 cells/mL up to passage 25. 6–8 week-old nude mice from Jackson Labs were implanted with 5 × 106 cells subcutaneously on the left flank with 50 % v/v Matrigel and experiments were performed once they reached 250–300 mm3. All animal procedures were approved and performed in accordance with IACUC and AAALAC guidelines.

Protein constructs

Humabody constructs were provided by Crescendo Biologics. Humabody VH generation methods and the Crescendo mouse platform have been previously described [31]. Humabody constructs were expressed as histidine tagged proteins in a microbial system, and subsequently purified using standard nickel affinity and size exclusion chromatography techniques. Samples were confirmed to contain low levels of endotoxin (<0.5 EU/mL). Purified sample quality was confirmed by SDS PAGE, SEC-UPLC and LC-MS prior to their use (Figure S1)

Humabodies were labeled using NHS ester chemistry with AlexaFluor 680 (AF680) or AlexaFluor 647 (AF647) as described previously for a final degree of labeling between 0.3–0.6 [33]. For (non-sulfated) Cy5.5 conjugates (Lumiprobe), the Cy5.5 dye in DMSO was serially diluted in PBS up to a volume of 30 µL before adding gradually to the protein construct to keep the dye dissolved. Concentrations and degree of labeling were verified using absorbance spectra from a NanoDrop.

Histology imaging and tumor digests

Once tumors reached a size of 250–300 mm3, mice received injections of 0.7 nmol fluorescent Humabody or J591 antibody via tail vein. After 24 h, mice received injections of 15 mg/kg Hoechst 33342 to mark functional vessels 15 min before sacrifice, and tumors were resected. Part of the tumor was flash frozen in OCT, stored at -80°C, and sectioned into 12 µm slices with a cryostat. Tumors were digested with Miltenyi Tumor Dissociation kits according to manufacturer's instructions, then measured on an Attune Flow Cytometer. Data were analyzed using FlowJo.

Before imaging, tumor sections were stained for 30 min with CD31 antibody (BD Bioscences) labeled with AlexaFluor555 to mark blood vessels. Tumors were imaged on an Olympus FV1200 confocal microscope using 405 nm, 543 nm, and 635 nm lasers using a 20x objective. Multiple images of each tumor were scanned and stitched together using Olympus software. Images were analyzed using Fiji (ImageJ).

Heterotypic spheroids

Heterotypic spheroids were seeded in AggreWell Plates (STEM Technologies) after preparing plates by washing each well with basal media, then adding 500 µL non-adherent rinse solution per well and spinning down at 1300 x g for 5 min. After ensuring no bubbles remained in each microwell, the rinse solution was removed and wells were washed with basal media before adding 1 mL complete RPMI media (containing 10 % FBS and 1 % Penicillin/streptomycin). 22Rv1 and 4-1BB reporter cells were seeded simultaneously in complete RPMI media with a concentration of 3,000 cells and 1,000 cells per microwell, respectively, for a total volume of 2 mL in each well, including 20% v/v methylcellulose. Complete RPMI media was exchanged daily until day 5 when spheroids were incubated for 24 h with varying concentrations of Humabody (unlabeled for bioluminescent assays or labeled with AlexaFluor647 for imaging), then harvested. After extracting spheroids from the plates, spheroids were filtered using STEM Technologies filters to remove unincorporated single cells.

Spheroids were either used to measure T cell activation (described below) or washed twice with PBS-BSA (0.5%) and fixed using BD Cytofix for 15 min. Spheroids were washed again with PBS and flash frozen in OCT, then stored at -80°C until sectioning into 12 μm slices. Before imaging, spheroid slides were stained for 30 min with CD45-FITC (BD Biosciences), washed in PBS, and followed with a Hoechst 33342 stain for 1 min to stain cell nuclei. Spheroid slides were then imaged on the FV1200 confocal microscope with 405 nm, 488 nm, and 635 nm lasers.

To determine the saturation point, spheroids incubated with varying concentrations of Humabodies were filtered to remove single cells, then digested using trypsin at 37°C. Cells were then washed with PBS-BSA (0.5 %) and pelleted. The digested spheroids were then resuspended in 40 nM PSMA-CD137-HLE-AF647 to saturate the remaining available receptors on the cell surface. Cells were washed again, then analyzed on an Attune Flow Cytometer.

T cell activation assays

After harvesting, spheroids were washed in basal media, filtered to remove single cells, and transferred to opaque, white 96-well plates in 75 µL basal media with triplicate wells for each concentration tested. 75 µL BioGlo reagent (Promega) was added to each well for a 15 min incubation. Plates were then scanned on a BioTek platereader to measure bioluminescence and fold induction was measured by the following equation: (treated spheroid luminescence – negative well luminescence)/(untreated spheroid luminescence – negative well luminescence), where negative well luminescence is 75 µL basal media and 75 µL BioGlo reagent. Data were graphed in PRISM (GraphPad). Data shown is the mean and SEM of three technical replicates for 2D data and three independent experiments for spheroids.

For the 2D format, DU145T or 22Rv1 cells were plated at 40,000 cells/well the day before the assay. Various concentrations of Humabody were prepared in RPMI media with 1% FBS and added to wells with 50,000 cells/well 4-1BB effector cells for a total volume of 75 µL/well. Plates were transferred to an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 6 h before plates were removed and equilibrated to room temperature for 15 min. Then, 75 µL of BioGlo reagent was added to each well and incubated for 15 min before scanning on a BioTek plate reader.

Spheroids with albumin

Spheroids were seeded using a similar procedure as described above, with 3,000 DU145T cells per microwell. Media changes were completed daily until 8 days after seeding. The media in some wells was replaced with complete media (RPMI with 10 % FBS and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin) containing 14 mg/mL human serum albumin (HSA) or mouse serum albumin (MSA), and a few hours later 20 nM Humabody with the corresponding HSA or MSA binding HLE domains were added. After 24 h, spheroids were harvested, flash frozen, and sectioned on a cryostat. Fluorescence intensity was mapped against distance from the spheroid edge using Euclidean distance mapping as described previously [34]. Data shown is the mean fluorescent intensity and standard deviation of 7–10 spheroid images, and was representative of multiple independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t tests in Prism (GraphPad).

Albumin binding domain affinity measurements

Affinity measurements were determined using a ForteBio Octet RED 384. ARG2 sensors were coated with HSA or MSA. Serial dilutions (1:2) of anti-HSA and anti-MSA Humabody VH were prepared from a top concentration of 300 nM. Binding kinetics were determined from sensorgram traces using 1:1 binding models and ForteBio Octet Data Analysis software.

Spheroid modeling

Spheroid modeling of drug penetration was adapted from previous Krogh cylinder and spheroid code, [35] where the equations and parameters used are provided in supplemental information. Briefly, the simulations solved for free, PSMA-bound, albumin-bound, and internalized Humabody based on experimental or literature values, accounting for diffusion, target binding, internalization, and albumin binding, with modified diffusion rates for albumin-bound constructs.

Results

Humabody binding and crosslinking

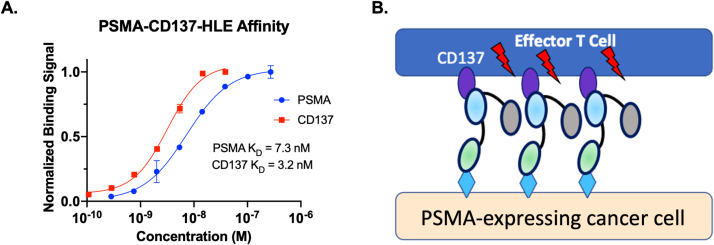

The Humabodies were generated from 3 fully human VH domains derived from the Crescendo Mouse: anti-PSMA, anti-CD137, and anti-albumin, from N to C terminus, respectively. The PSMA and CD137 affinities were measured on cells with 7.3 nM and 3.2 nM affinities, respectively (Fig. 1A). When binding in the synapse between a T cell and cancer cells, the PSMA binding will cluster the CD137 on the T cell, driving signaling (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Binding Affinity and Mechanism. Measured binding affinity of PSMA and CD137 domains on cells (A). Synapse binding between T cells and cancer cells clusters the receptor to drive signaling (B). It is assumed that albumin binding does not interfere with clustering for these agents.

T cell activation in monolayers and heterotypic spheroids

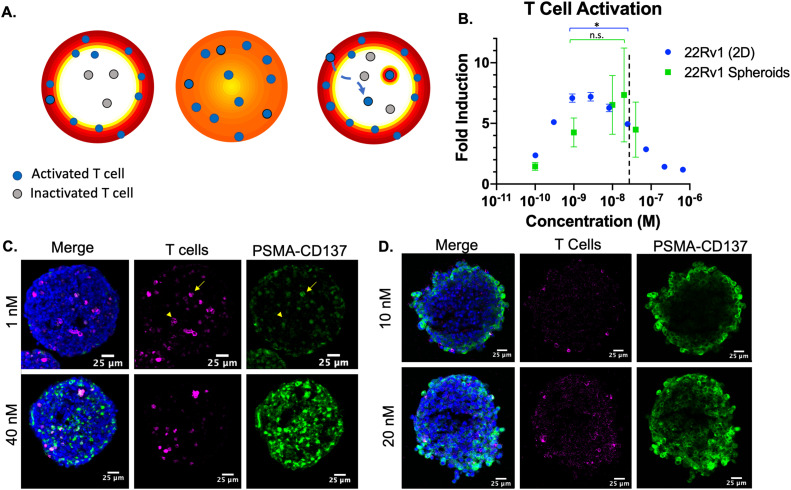

In order to determine how tissue penetration of the bispecific Humabodies related to T cell activation, we used a heterotypic spheroid system and compared the activation of the T cell reporter cell line in 2D vs 3D culture. This system enables testing of tissue penetration using human cell lines since this Humabody does not cross-react with mouse CD137. While tissue penetration of ADCs is known to significantly impact efficacy, [12] it is possible that tissue penetration of bispecific therapeutics has less of an impact. For example, the mobility of immune cells could compensate for drug gradients and/or the avidity from binding multiple antigens may concentrate the bispecific in regions with lower free drug (Fig. 2A). The 3D tissue culture was used to capture these effects.

Fig. 2.

Heterotypic spheroids for T cell activation. (A) Heterogeneous Humabody distribution may leave T cells in the center inactivated (left) relative to more homogeneous distribution (middle). However, migrating T cells and/or avidity increasing binding in the synapse may compensate for poor distribution (right). (B) T cell activation from 2D and 3D experiments demonstrated higher concentrations are needed for full activation in 3D culture, indicating tissue penetration is having an impact. The 3D spheroid saturation point is marked with a dotted line. (C) Images of heterotypic 22Rv1 spheroids show cell nuclei (blue), CD45 to mark T cells (magenta) or Humabody (green). An example of concentrated Humabody around a T cell marked with an arrow versus a T cell without concentrated Humabody marked, arrowhead. (D) Tissue gradients are steeper in the high expression DU145 spheroids, but T cells were mainly incorporated along the periphery, preventing measurement of activation in the middle of the spheroid. * p < 0.05.

In monolayer culture, PSMA-expressing cells are incubated with the reporter T cell line seeded on top with a given concentration of Humabody. This ensures the PSMA cells are directly exposed to the Humabody concentration in media in the presence of T cells. Under these conditions, signaling of CD137 on the T cell surface is mediated by Humabody crosslinking PSMA on the cancer cell with CD137 on the T cell to drive clustering of the receptor. This is seen as an increase in reporter cell line signal when concentrations ranged from 0.1 to 3 nM (Fig. 2B). As the concentration increased in monolayer culture, the free Humabody concentration started to compete with crosslinked Humabody, resulting in the binding of two separate Humabodies that do not crosslink (Figure S2). Signaling therefore peaks at 1–3 nM and starts to reduce at higher concentrations until complete inhibition at 1 µM. The difference in activation between 1 nM and 20 nM was statistically significant in 2D culture (p = 0.0056) via unpaired t test.

For the 3D (heterotypic spheroid) experiments, the cell-level binding is also influenced by gradients in extracellular concentrations of Humabody from the spheroid periphery to the center. The improved tissue penetration compensates for suppression at higher concentrations, and in contrast to 2D culture, the difference in activation between 1 nM and 20 nM was not significant (p = 0.49). As the drug concentration increased in 3D culture, the activation of T cells increased up until 20 nM. Notably, T cell activation in 3D culture was less than 2D culture at lower concentrations of Humabody. In 3D culture, the signal decreased at 40 nM, and this concentration coincides with spheroid saturation (Figure S3).

To visualize the distribution of drug and T cells, we imaged spheroids after treatment with Humabody and stained for T cells. CD45 stain shows distribution of T cells throughout the spheroids (Fig. 2C). This is in contrast to heterotypic DU145 and T cell spheroids, where the T cells were mostly excluded and only found at the spheroid periphery (Fig. 2D). While the higher PSMA expression of DU145 results in steeper tissue gradients of Humabody, the impact on T cell activation was confounded by a lack of T cells in the spheroid center. For 22Rv1 spheroids, as the drug concentration increased, deeper penetration into the spheroid and higher signal intensity was observed (Figure S3). There were some T cells that showed higher binding than surrounding cancer cells (Fig. 2C arrow). This could be due to the avidity of binding in the immune synapse, since other T cells deeper in the tissue did not show this effect (Fig. 2C arrowhead). However, this was not sufficient to compensate for the reduced tissue penetration in the spheroid. Therefore, these results demonstrate that tissue penetration can play a role in T cell activation of these bispecific agents.

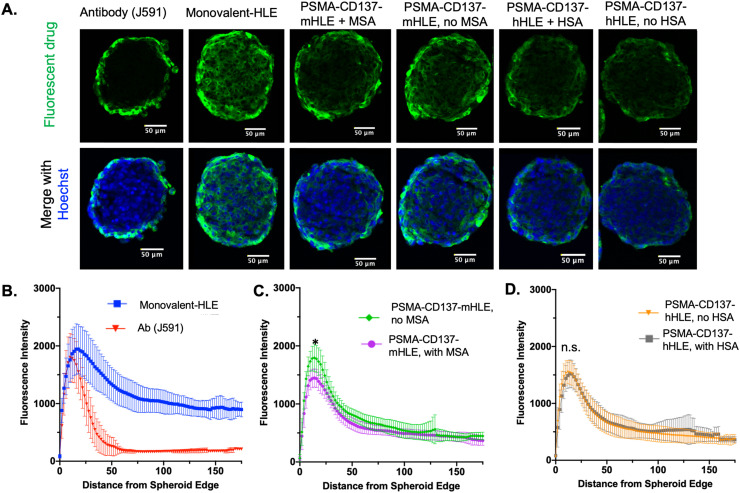

Albumin binding and tissue penetration

Given the importance of tissue penetration, we next investigated the impact of albumin binding on diffusion. In theory, the diffusion of a Humabody-albumin complex (∼110 kDa) would be slower than the Humabody alone (∼45 kDa), which could reduce tissue penetration. The impact of albumin binding on tissue distribution was therefore tested in DU145T spheroids. Humabodies with HLE domains were incubated with and without their corresponding albumin type (HSA or MSA), which have 8 nM and 50 nM affinity (Kd), respectively. In both cases, the addition of albumin did not result in changes in tissue penetration compared to Humabody alone (Fig. 3A). Despite the concentration of albumin well above the Kd (∼ 200 µM), where most of the Humabody could be in complex with albumin, the presence of albumin had a negligible effect on tissue penetration. These findings were confirmed by quantitative image analysis to map the fluorescence distribution as a function of distance from the spheroid edge (Fig. 3B–D). The fluorescent signal in the center of the spheroids did not show any statistically significant differences with and without albumin. In contrast, an equal molar amounts of J591 antibody (∼150 kDa) resulted in heterogeneous distribution, which is typical for large biologics. A control monovalent-HLE (that had no CD137 binding domain) with the lowest molecular weight (∼30 kDa) distributed the most evenly.

Fig. 3.

Tissue penetration of Humabodies with and without albumin in spheroids. Spheroids show cell nuclei (blue) and fluorescent drug (green). Incubations included 20 nM J591 antibody, monovalent-HLE Humabody, PSMA-CD137 with MSA binding HLE (mHLE) incubated with and without MSA, PSMA-CD137 with HSA binding HLE (hHLE) incubated with and without HSA (A). Euclidean distance mapping shows the fluorescent intensity versus distance from the spheroid edge in μm (B-D), indicating that specific albumin binding is not impacting tissue penetration to the spheroid center. The MSA binders (Fig. 2B) had lower maximum signal with the presence of MSA (p=0.002), but HSA binders did not have differences in the maximum signal (p = 0.85). *, p < 0.05.

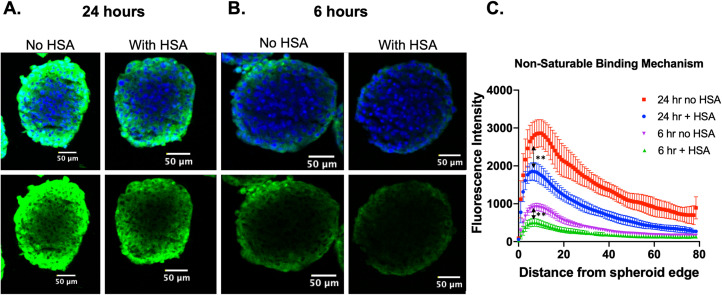

Non-specific albumin binding and tissue penetration

The efficient tissue penetration of the Humabodies was consistent with literature reports of reduced plasma clearance but high tissue penetration of proteins with albumin binding domains. However, low molecular weight lipophilic agents, such as fatty acids, can also mediate albumin binding at a lower molecular weight than antibody domains. To shed light on these differences, we tested a non-specific albumin binding mechanism by conjugating a lipophilic dye, Cy5.5, to the Humabody. Lipophilic small molecules are well known modifications to induce albumin binding by interacting with the small hydrophobic pockets on albumin normally utilized to shuttle fatty acids in the blood. In fact, peptides, such as semaglutide, use this mechanism for reduced clearance [36]. Previously, we have used non-sulfated cyanine dyes as a lipophilic moiety to induce albumin binding [37].

In spheroids incubated with Humabodies conjugated to lipophilic Cy5.5, we observed differences in tissue penetration after 6 h and 24 h incubations, both in terms of intensity of signal, representing total uptake into the spheroid, and penetration depth (Fig. 4A,B). Similarly, these observations were confirmed using quantitative image analysis (Fig. 4C) that shows differences in distribution and maximum signal with and without albumin present. Unlike the HLE Humabody that is specific for albumin, the lipophilic dye is capable of interacting with many proteins, cell membranes, etc. in a non-specific manner. These results provide evidence that non-specific mechanisms of albumin binding can impact tissue distribution.

Fig. 4.

Impact of non-specific albumin binding on tissue penetration in spheroids. Spheroids were incubated for 24 h (A) or 6 h (B) with 20 nM Humabody labeled with lipophilic dye, Cy5.5. Euclidean distance mapping shows fluorescence intensity for each condition as a function of distance from spheroid edge. The non-specific interaction with albumin reduces the total uptake and penetration depth within the spheroids. **, p < 0.000001.

Mathematical model of tissue penetration with albumin binding

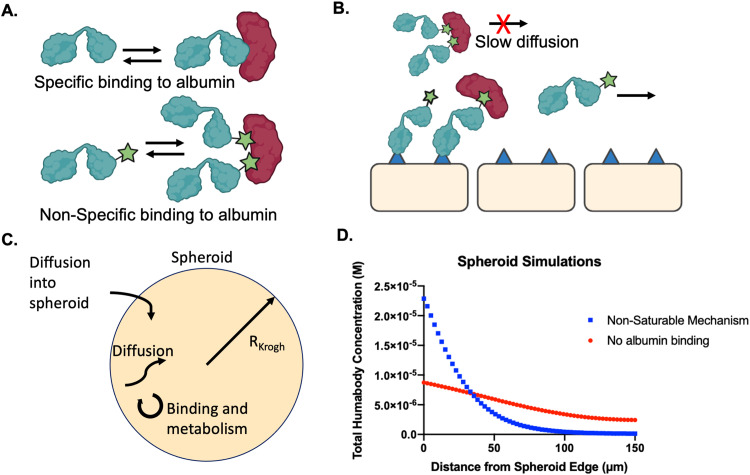

The molecular mechanism behind the difference in tissue penetration is not completely understood. Conceptually, a specific mechanism of albumin binding would have a defined stoichiometry and reach an equilibrium with the antibody/bispecific (assuming rapid binding relative to diffusion). Once the albumin-binding had reached a pseudo-steady state, further association with albumin would be offset by dissociation, allowing unbound antibody to rapidly diffuse in the tissue. In contrast, a non-specific lipophilic mechanism could bind both at higher stoichiometries and may bind to other cellular/extracellular components, potentially reducing the amount of free protein to diffuse, resulting in lower tissue penetration (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Simulations of reversible Humabody binding via specific or non-specific mechanisms. Non-specific mechanisms can interact with multiple albumin domains and other proteins/membrans versus a single epitope (A). Schematic that displays how Humabody-albumin complexes may diffuse more slowly through tissue and potentially limit tissue penetration compared to free Humabody (B). A schematic of the spheroid simulations, which include diffusion, binding to the cell surface, binding to albumin, internalization, and degradation (C). Simulation results displaying concentration of Humabody versus distance from the spheroid edge with and without albumin binding (D).

To model these concepts empirically (due to uncertainty in the exact mechanism), we modified a previously used model of antibody penetration in tumor spheroids to included albumin binding. In one case, the number of available binding sites was held constant such that it could not be saturated. This was used to mimic an agent like Cy5.5 that can presumably bind a large number of low affinity sites similar to non-specific sticking models. Matching experimental results, heterogeneous distribution of the Humabody was documented with spheroid distribution simulations when albumin could not be saturated (Fig. 5D). Alternatively, more homogeneous distribution was achieved in simulations when binding to albumin was assumed to have a negligible effect on tissue penetration, creating a similar distribution to Humabody with no albumin present or a specific binding mechanism. This empirical result suggests that specific albumin binding under these conditions does not substantially influence distribution while non-specific lipophilic moieties can.

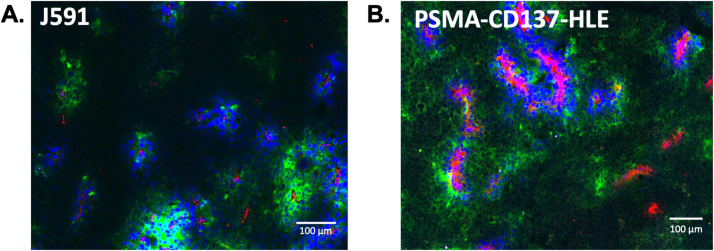

Tissue penetration in vivo

The spheroid data indicated that tissue penetration of bispecific agents is important for efficacy, and the albumin binding domain did not negatively impact efficient distribution in this 3D culture. We next tested the tissue penetration of the Humabodies in vivo to confirm efficient tumor penetration. Using the same molar dose of J591 antibody and PSMA-CD137-HLE Humabody in PSMA expressing DU145 tumors, the monoclonal antibody J591 had higher intensity of signal around blood vessels and did not penetrate as far from vessels as the Humabody (Fig. 6). The Humabody shows lower signal intensity overall because the Humabody is spread more evenly through the tumor similar to the 3D tissue culture.

Fig. 6.

Confirmation of efficient tumor tissue penetration in vivo. Fluorescent tumor images show (A) J591 antibody or (B) Humabody (green) around functional vessels (blue) and CD31 stain (red) 24 h after a 0.7 nmol dose in nude mice (representative images from n=3 mice). Images were collected with different acquisition settings and displayed with different contrasts due to large differences in fluorescent intensity.

Discussion

CD137 is an attractive target for stimulating strong T cell responses in cancer patients, but several efforts with monoclonal antibodies have not been successful in the clinic, either due to high toxicity or lack of efficacy. In light of the lack of tumor selectivity for first-generation CD137-targeted agents and other bispecifics, there is a need to refine the design of immunotherapies to avoid off-tumor toxicity and maximize efficacy. In this work, we combined in vitro and in vivo methods on variants of the clinical-stage bispecific, CB307, to determine the role of tissue distribution for CD137 and tumor associated antigen bispecific immunotherapies, confirm that lower molecular weight variants can be used to improve tumor penetration, and investigate how albumin binding influences tissue penetration. Understanding these parameters is important for the development of bispecific therapeutics in addition to other agents that rely on albumin as a half-life extender or carrier. Our findings demonstrate that tissue penetration can impact the efficacy of bispecifics and is an important factor that should be incorporated in the design of these therapeutics. Small format biologics, such as the single domain Humabodies used here, can achieve efficient tissue penetration, and albumin binding does not impede on their distribution or targeting. However, other mechanisms of albumin binding, such as small lipophilic moieties, have the potential to limit tissue penetration.

Properties of the tumor microenvironment create challenges in achieving homogeneous tissue distribution due to elevated interstitial pressure and poor lymphatic drainage that causes diffusion to be the primary driving force for mass transfer [38]. However, the relationship between efficacy and tissue penetration for bispecific therapies has not been fully established. Here, we used a single-digit nM bispecific to PSMA and CD137 that is able to bind cancer cells and crosslink CD137 receptors on nearby T cells (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that reaching a greater number of T cells with drug would result in greater overall activation, and T cell mobility or avidity effects would not be sufficient to compensate for heterogeneous distribution (Fig. 2A). In monolayer culture, high concentrations reduce activation, which is a commonly seen phenomenon for crosslinking agents (Fig. 2B). Results from the heterotypic spheroid model, however, only show maximum activation once the spheroid is nearly saturated, supporting the concept that improved tissue penetration is connected to improved efficacy with bispecific agents. Notably, the 2D experiment shows the highest activation at lower concentrations than the 3D experiment. This is consistent with imaging (Fig. 2C) and saturation measurements (Figure S4) demonstrating that at these concentrations, the spheroids were at sub-saturating concentrations, so not all T cells had yet been reached.

Both the 2D and 3D experiment showed a decrease in activation at high concentrations, which was beyond the spheroid saturation concentration in 3D culture (Fig. 2B, Figure S4). This bell-shaped pharmacodynamic effect (often called a “hook effect” particularly if the concentration range is truncated) has been observed in other studies involving antibodies that target co-stimulatory receptors [39], [40], [41]. This effect is attributed to competition with free bispecific antibody, where the unbound bispecific antibody can compete with monovalently bound bispecific for available receptors, promoting separate, monovalent binding to receptors rather than bispecific crosslinking. Other mechanisms can also reduce T cell activation, such as T cell exhaustion from continuous exposure to bispecific agents (e.g. a CD19xCD3 bispecific), but this occurs over several weeks [42]. The short incubation (hours) and use of a reporter cell line indicate the reduction in T cell activation is due to monovalent binding in these experiments.

After establishing the importance of tumor penetration, we examined if the high affinity albumin binding domain impacted tissue distribution. Albumin binding can extend the half-life of antibody fragments and increase tumor uptake, [12,21] but it is possible that the increase in apparent molecular weight upon binding to albumin (66 kDa) could hamper improvements in tissue penetration created by using low molecular weight agents. Previous studies have investigated the impact of HLE affinity to albumin on plasma clearance, showing a wide range of affinities that can improve plasma clearance, from sub-nanomolar to double-digit micromolar affinity to albumin [29,[43], [44], [45]]. Organ-level mechanistic physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models have demonstrated the relationship between binding affinity and plasma clearance [46,47]. However, the relationship between albumin binding and tissue penetration has not been studied in depth.

When using the specific albumin binding Humabody, our experimental results show albumin binding does not measurably impact tissue penetration even with high (single-digit nM) affinity and micromolar concentrations of albumin (Fig. 3). In contrast, a lipophilic dye, which can also bind albumin to reduce plasma clearance, [37] did limit tissue uptake and distribution in the presence of albumin (Fig. 4). While lipophilic moieties may be suitable for some therapeutics and molecular imaging agent applications, these data indicate the use of specific albumin-binding domains can be beneficial when tissue penetration is important. To demonstrate that the spheroid results translate to in vivo distribution, we imaged the tissue penetration of a J591 monoclonal antibody and Humabody construct in vivo. Consistent with previous results with antibody fragments, [12,20,21,48] the 45 kDa Humabodies demonstrated improved tissue penetration compared to a 150 kDa antibody in vivo (Fig. 6, Figure S5) similar to the spheroids (Fig. 3).

The trade-offs of poor tissue penetration must be considered alongside the benefits of longer half-life and increased tumor uptake to design therapeutics with maximum therapeutic efficacy across multiple biologic formats such as DARPins, [49,50] peptides, [51] and small molecules [52] that rely on these mechanisms. The results here show that specific albumin-binding domains are advantageous for Humabodies by extending plasma half-life without compromising tissue penetration compared to lipophilic albumin-binding moieties. Lipophilic moiety constructs, like the lipophilic Cy5.5 conjugated Humabody investigated here, are expected to bind non-specifically to albumin in addition to other proteins and/or cell membranes. Notably, the distribution of the lipophilic dye-conjugated Humabody was similar to the distribution of the specific albumin binders in the absence of albumin at 24 h, but the uptake and distribution of this agent were reduced in the presence of albumin. This suggests that albumin is playing a larger role than other interactions in the uptake. Albumin is often used as a carrier protein to minimize sticking of other molecules to surfaces, and non-specific sticking of the Cy5.5-Humabody in the absence of albumin could impact the results. However, this sticking would reduce the bulk concentration and lower uptake in spheroids in the absence of albumin, which is the opposite trend to what was observed. The results presented here may not translate to other lipophilic albumin-binding domains, but it does warrant consideration when tissue penetration can impact the outcome. Additionally, others have demonstrated that the binding of fatty acids to albumin can prevent FcRn binding and recycling, [53] one of the essential mechanisms that leads to albumins long half-life [54]. Thus, it's important to ensure that FcRn functions are preserved in designing albumin fusions or albumin binders.

There are several limitations to the result here. First, the CD137 domain does not bind mouse CD137; therefore, the impact of CD137 binding/affinity is not captured in vivo. Second, the lack of cross-reactivity also limited pharmacodynamic measurements of signaling to 3D spheroids instead of intact tumor tissue. The interplay between distribution in the context of tumor efficacy could not be measured. However, the clinical stage compound, CB307, has been shown to increase cytokine secretion in the context of PSMA antigen presentation, induce T cell killing in spheroids, and show efficacy in a syngeneic mouse model [17]. Third, the focus was on the impact of the albumin binding domain, whereas affinity, valency, linker flexibility, and dose (tumor saturating versus subsaturating) are all known to impact tumor uptake, distribution, and efficacy [[51], [52], [53], [54]]. Nevertheless, these results show that tissue penetration has the potential to impact efficacy for bispecific agents and should be considered during preclinical development.

In summary, this work examined the importance of tissue penetration for bispecific antibody fragments targeting co-stimulatory T cell receptors and investigated the impact of albumin binding on tissue penetration. These results demonstrate that tissue penetration can impact T cell activation, and smaller protein formats can improve tissue distribution. Specific albumin binding Humabody domains, which improve plasma clearance, did not impact tissue penetration. Depending on the mechanism of albumin binding, however, tissue penetration can be impacted, particularly with non-specific mechanisms. These results can be used to design effective bispecific agents with improved plasma clearance and tissue penetration.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anna Kopp: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Hyeyoung Kwon: Investigation. Colette Johnston: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Steven Vance: Investigation, Resources. James Legg: Conceptualization, Supervision. Laurie Galson-Holt: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Greg M. Thurber: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Colette Johnston, Steven Vance, James Legg, and Laurie Galson-Holt are employees of Crescendo Biologics, which is developing CB307 and related therapeutics. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

Funding for this work was provided by Crescendo Biologics.

Footnotes

Humabody® is a registered trademark of Crescendo Biologics Ltd.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neo.2023.100962.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wei J., Yang Y., Wang G., Liu M. Current landscape and future directions of bispecific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1035276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labrijn A.F., Janmaat M.L., Reichert J.M., Parren P.W.H.I. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:585–608. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goebeler M.E., Bargou R.C. T cell-engaging therapies - BiTEs and beyond. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020;17:418–434. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borlak J., Länger F., Spanel R., Schöndorfer G., Dittrich C. Immune-mediated liver injury of the cancer therapeutic antibody catumaxomab targeting EpCAM, CD3 and Fcγ receptors. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28059–28074. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hashimoto K. Cd137 as an attractive T cell Co-stimulatory target in the TNFRSF for immuno-oncology drug development. Cancers. 2021;13:2288. doi: 10.3390/cancers13102288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chin S.M., et al. Structure of the 4-1BB/4-1BBL complex and distinct binding and functional properties of utomilumab and urelumab. Nat. Commun. 2018;9 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu X., et al. TNF receptor agonists induce distinct receptor clusters to mediate differential agonistic activity. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02309-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmerman J., et al. Urelumab alone or in combination with rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell lymphoma. Am. J. Hematol. 2020;95:510–520. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal N.H., et al. Phase I study of single-agent utomilumab (PF-05082566), a 4-1bb/cd137 agonist, in patients with advanced cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;24:1816–1823. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mhawech-Fauceglia P., et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) protein expression in normal and neoplastic tissues and its sensitivity and specificity in prostate adenocarcinoma: an immunohistochemical study using mutiple tumour tissue microarray technique. Histopathology. 2007;50:472–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross J.S., et al. Correlation of primary tumor prostate-specific membrane antigen expression with disease recurrence in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003;9:5357–6362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nessler I., et al. Increased tumor penetration of single-domain antibody-drug conjugates improves in vivo efficacy in prostate cancer models. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1268–1278. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cilliers C., Menezes B., Nessler I., Linderman J., Thurber G.M. Improved tumor penetration and single-cell targeting of antibody–drug conjugates increases anticancer efficacy and host survival. Cancer Res. 2018;78:758–768. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponte J.F., et al. Antibody co-administration can improve systemic and local distribution of antibody–drug conjugates to increase in vivo efficacy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021;20:203–212. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-20-0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bordeau B.M., Yang Y., Balthasar J.P. Transient competitive inhibition bypasses the binding site barrier to improve tumor penetration of trastuzumab and enhance T-DM1 efficacy. Cancer Res. 2021;81:4145–4154. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jung K., Yoo S., Kim J.-E., Kim W., Kim Y.-S. Improved intratumoral penetration of IL12 immunocytokine enhances the antitumor efficacy. Front. Immunol. 2022;13:6588. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1034774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce A.J., et al. Abstract 1807: CB307: a novel targeted CD137 agonist for enhancement of immune cell responses to PSMA+ tumors. Cancer Res. 2023;83 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bannas P., Hambach J., Koch-Nolte F. Nanobodies and nanobody-based human heavy chain antibodies as antitumor therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1603. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roovers R.C., et al. A bi-paratopic anti-EGFR nanobody efficiently inhibits solid tumour growth. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;129:2013–2024. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokota T., Milenic D.E., Whitlow M., Schlom1 J. Rapid tumor penetration of a single-chain Fv and comparison with other immunoglobulin forms. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3402–3408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tijink B.M., et al. Improved tumor targeting of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor Nanobodies through albumin binding: taking advantage of modular Nanobody technology. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2288–2297. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deonarain M., et al. Small-format drug conjugates: a viable alternative to ADCs for solid tumours? Antibodies. 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/antib7020016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu A.M., Senter P.D. Arming antibodies: prospects and challenges for immunoconjugates. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1137–1146. doi: 10.1038/nbt1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang B., Lim S.I., Kim J.C., Tae G., Kwon I. Site-specific albumination as an alternative to PEGylation for the enhanced serum half-life in vivo. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:1811–1817. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennis M.S., et al. Albumin binding as a general strategy for improving the pharmacokinetics of proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:35035–35043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhury C., Brooks C.L., Carter D.C., Robinson J.M., Anderson C.L. Albumin binding to FcRn: distinct from the FcRn-IgG interaction. Biochemistry. 2006;45:4983–4990. doi: 10.1021/bi052628y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahimizadeh P., Yang S., Lim S.I. Albumin: an emerging opportunity in drug delivery. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2020;25:985–995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoefman S., et al. Pre-clinical intravenous serum pharmacokinetics of albumin binding and non-half-life extended Nanobodies®. Antibodies. 2015;4:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams R., et al. Extending the half-life of a fab fragment through generation of a humanized anti-human serum albumin Fv domain: an investigation into the correlation between affinity and serum half-life. MAbs. 2016;8:1336–1346. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1185581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen A., et al. The pharmacokinetics of an albumin-binding Fab (AB.Fab) can be modulated as a function of affinity for albumin. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2006;19:291–297. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng Y., et al. Diverse human VH antibody fragments with bio-therapeutic properties from the Crescendo Mouse. N. Biotechnol. 2020;55:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kampmeier F., Williams J.D., Maher J., Mullen G.E., Blower P.J. Design and preclinical evaluation of a 99mTc-labelled diabody of mAb J591 for SPECT imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) EJNMMI Res. 2014;4:13. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-4-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cilliers C., Nessler I., Christodolu N., Thurber G.M. Tracking antibody distribution with near-infrared fluorescent dyes: impact of dye structure and degree of labeling on plasma clearance. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:1623–1633. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b01091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khera E., et al. Quantifying ADC bystander payload penetration with cellular resolution using pharmacodynamic mapping. Neoplasia. 2021;23:210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khera E., et al. Cellular-resolution imaging of bystander payload tissue penetration from antibody-drug conjugates. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022;21:310–321. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-21-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christou G.A., Katsiki N., Blundell J., Fruhbeck G., Kiortsis D.N. Semaglutide as a promising antiobesity drug. Obes. Rev. 2019;20:805–815. doi: 10.1111/obr.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khera E., et al. Blocking of glucagonlike peptide-1 receptors in the exocrine pancreas improves specificity for β-cells in a mouse model of type 1 diabetes. J. Nucl. Med. 2019;60:1635. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.224881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baxter L.T., Jain’ R.K. Transport of fluid and macromolecules in tumors I. Role of interstitial pressure and convection. Microvasc. Res. 1989;37:77–104. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(89)90074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayes P.A., Hance K.W., Hoos A. The promise and challenges of immune agonist antibody development in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:509–527. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stebbings R., et al. ``Cytokine storm” in the phase I trial of monoclonal antibody TGN1412: better understanding the causes to improve preclinical testing of immunotherapeutics. J. Immunol. 2007;179:3325–3331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher T.S., et al. Targeting of 4-1BB by monoclonal antibody PF-05082566 enhances T-cell function and promotes anti-tumor activity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2012;61:1721–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1237-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philipp N., et al. T-cell exhaustion induced by continuous bispecific molecule exposure is ameliorated by treatment-free intervals. Blood. 2022;140:1104–1118. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopp J., et al. The effects of affinity and valency of an albumin-binding domain (ABD) on the half-life of a single-chain diabody-ABD fusion protein. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2010;23:827–834. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connor-Semmes R.L., et al. GSK2374697, a novel albumin-binding domain antibody (AlbudAb), extends systemic exposure of exendin-4: first study in humans—PK/PD and safety. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;96:704–712. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thorneloe K.S., et al. The biodistribution and clearance of AlbudAb, a novel biopharmaceutical medicine platform, assessed via PET imaging in humans. EJNMMI Res. 2019;9 doi: 10.1186/s13550-019-0514-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sepp A., Bergström M., Davies M. Cross-species/cross-modality physiologically based pharmacokinetics for biologics: 89Zr-labelled albumin-binding domain antibody GSK3128349 in humans. MAbs. 2020;12 doi: 10.1080/19420862.2020.1832861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sepp A., et al. Computer-assembled cross-species/cross-modalities two-pore physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for biologics in mice and rats. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2019;46:339–359. doi: 10.1007/s10928-019-09640-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thurber G.M., Dane Wittrup K. Quantitative spatiotemporal analysis of antibody fragment diffusion and endocytic consumption in tumor spheroids. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3334–3341. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Binz H.K., et al. Design and characterization of MP0250, a tri-specific anti-HGF/anti-VEGF DARPin® drug candidate. MAbs. 2017;9:1262–1269. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2017.1305529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steiner D., et al. Half-life extension using serum albumin-binding DARPin® domains. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2017;30:583–591. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzx022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roscoe I., Parker M., Dong D., Li X., Li Z. Human serum albumin and the p53-derived peptide fusion protein promotes cytotoxicity irrespective of p53 status in cancer cells. Mol. Pharm. 2018;15:5046–5057. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kratz F., Azab S., Zeisig R., Fichtner I., Warnecke A. Evaluation of combination therapy schedules of doxorubicin and an acid-sensitive albumin-binding prodrug of doxorubicin in the MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic xenograft model. Int. J. Pharm. 2013;441:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt M.M., et al. Crystal structure of an HSA/FcRn complex reveals recycling by competitive mimicry of HSA ligands at a pH-dependent hydrophobic interface. Structure. 2013;21:1966–1978. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pyzik M., Rath T., Lencer W.I., Baker K., Blumberg R.S.FcRn. The architect behind the immune and non-immune functions of IgG and albumin. J. Immunol. 2015;194:4595–4603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.