Abstract

Objectives

To analyse the profile and implication of genetic testing in a cohort of retinoblastoma (RB) patients and their families conducted on a single day during World Retinoblastoma Awareness Week 2017.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of blood samples were collected from 411 subjects, including 113 probands at a camp organised for RB awareness and were analysed for RB1 mutations by Sanger sequencing and Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA). If germline mutations were detected, the parents and siblings of the proband were tested for the same mutation.

Results

Germline RB1 mutations were identified in 61/113(54%) probands with a mutation detection rate of 96% (47/49) and 22% (14/64) for bilateral and unilateral RB, respectively. Ten novel pathogenic mutations were identified. Splice mutation was most common (31%) followed by nonsense mutation (26%). The mean age at RB diagnosis was significantly lower in patients having germline RB1 mutation (mean 10.7 months ±2.5) compared to those without (mean 27.2 months ±6.5) (p = <0.0001). Parental transmission of the mutant allele was detected in 15/61(25%) cases of which 11(18%) parents were unaffected indicating incomplete penetrance. The origin of the variant allele was both paternal (n = 7) and maternal (n = 4) wherein 5 were bilateral and 6 unilateral.

Conclusions

The detection of a germline mutation impacts the proband and family members due to its implications on change in prognosis, frequency of subsequent evaluations, screening for ocular and non-ocular cancers, and surveillance of family and future progeny.

Subject terms: Disease genetics, Eye cancer, Population genetics

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common primary intraocular malignancy in children, having an incidence of 1 in 15000 live births globally, and is caused by the biallelic inactivation of the RB1 gene [the “two-hit” hypothesis] [1]. The RB1 gene is the archetypal tumour suppressor gene on chromosome 13q14 containing 27 exons spanning 180 kb [2]. The two hits can be structural alterations in the genome or functional inactivation and can occur in either heritable or non-heritable forms [2, 3]. In heritable RB (also known as germline RB), one of the RB1 allele is mutated in all the cells in the proband (M1) [since it may have been inherited from one of the parents], along with an acquired somatic mutation in the second allele in the retina cells [M2 event] that give rise to the tumour. The germline mutations are also detected in 30% of sporadic cases (de novo germline) and are often a result of genomic errors during gametogenesis in parents (more common during spermatogenesis) or in the very early embryonic phase [2, 4, 5]. Non-heritable RB develops as a result of two consecutive losses of functional RB1 alleles in the immature retinal cells. In India, 50%-60% of children with RB undergo primary enucleation due to late disease presentation [6, 7]. Although enucleation increases the survival of children, it largely impairs their quality of life [8]. In this regard, early diagnosis can aid in improved survival, globe salvage and vision salvage. Genetic testing in RB not only unravels the spectrum of underlying mutations but is critical to assess the risk for tumour development in the other eye, in siblings and progeny of the affected proband, which aids in achieving better globe salvage by early detection. The major hindrances of molecular testing for genetic diseases in developing countries include the lack of accessibility to these resources and the affordability of such testing. Therefore, we attempted to make it accessible to all the RB survivors under our care and their families on a single day on the occasion of World Retinoblastoma Awareness Week on 13th May 2017, to aid in the future direction of management of these families.

Methodology

The study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics committee, and the Institutional Review Board and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study cohort

This study included unrelated RB patients, along with their parents and siblings, who were being treated and followed up for at our tertiary care centre. The demographic details were obtained from medical records including the age of noticing the first sign, age at diagnosis, treatment history, response to treatment and investigations performed during their follow-up visits. A detailed family history and pedigree chart for at least three prior generations were documented for each survivor. Diagnosis of RB was established by thorough anterior and posterior segment examination using a portable slit lamp, indirect ophthalmoscopy, digital wide field imaging and B-scan ultrasonography examinations under general anaesthesia (EUA). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits was also performed to screen for local and distant spreads. All the cases were classified according to the International Intraocular Retinoblastoma Classification (ICRB) system [9]. Patients with bilateral disease or unilateral Group B, C and D were treated with systemic chemotherapy along with focal consolidation with transpupillary thermotherapy using diode laser and cryotherapy wherever appropriate. Eyes with a small tumour (Group A) received only local treatment. Group E tumours were treated either with chemotherapy or underwent primary enucleation on a case-to-case basis. Eyes with advanced tumours with multiple recurrences were enucleated. Adjuvant chemotherapy was done for patients showing high-risk features on histopathology. All probands were followed up for a period of 5 years after obtaining samples for genetic analysis. Follow-up with EUA was done till 7 years of age in germline mutations and it was modified based on the reports of the genetic testing in patients with unilateral RB with non- germline mutations.

Samples

All RB patients under treatment or follow-up at our hospital were informed prior about a genetic testing program on 13th May 2017 (on the occasion of World Retinoblastoma awareness week). Whole blood samples were collected from all the probands and their parents and siblings after getting written informed consent for genetic testing.

DNA Isolation and RB1 mutational screening

Peripheral blood samples were collected and genomic DNA was isolated by the modified salting-out method [10]. Mutation screening was performed in a stepwise strategy to identify point mutations, small indels, and large deletions as described in an earlier report [11]. Briefly, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) was performed with 20 ng of genomic DNA, 1X PCR Buffer, 200 µM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), 400 nM of each forward and reverse primer, and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Sequencing PCR was performed using the Big Dye Terminator kit version 3.1 and purified products were analysed on a 3500 Genetic Analyzer. Variants were then identified by aligning the sequences with the reference (NCBI accession no. L11910). RB1 gene mutation was confirmed from the gene locus-specific mutation database (http://rb1-lovd.d-lohmann.de/home.php). Variants in intronic regions causing splicing alterations were chosen if they were predicted by Human Splice Site Finder (https://www.umd.be/HSF/). Pathogenicity of novel variants was predicted by mutation taster (https://www.mutationtaster.org/), varsome (https://varsome.com/) and variant effector predictor (https://asia.ensembl.org/Tools/VEP). MLPA was performed with SALSA MLPA kit P047-RB1 kit v.C1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analysed using Coffalyser software (MRC Holland), where DNA copy number ratios of samples were used computed using the matched normal controls. The threshold for recording duplications was a ratio of >1.3 and for deletion was a ratio of <0.7. Parents and siblings were screened for the presence of mutations identified in probands using the same methods described above. Low-penetrance mutations are characterized as described by Tomar et al. [12]. The genetic test results were available after 4-8 weeks and post-test counselling was done during the following world retinoblastoma awareness week on 12th May 2018. Following genetic counselling, siblings were followed for two years to study the effects of post surveillance. Additionally, siblings harbouring germline mutations were examined under EUA for the presence of tumours and were subjected to frequent EUAs depending on age, even if initial EUA revealed no tumours.

Statistical analysis

An independent t-test was performed to test the significance of mean age at diagnosis with respect to genetic testing outcome and laterality. One-way ANOVA was used to test for differences in mean age at diagnosis with respect to mutation types. All the analysis was carried out in GraphPad Prism 9.0.2 (Graphpad Software Inc., USA).

Results

Demography and clinical features

A total of 411 peripheral blood samples including 113 RB patients (59 males and 54 females) and their family members were included for genetic screening for germline RB1 mutations. Of the 113 patients, 64 were affected unilaterally (56.6%) and 49 bilaterally (43.4%). The age of presentation ranged from 1–98 months, with the mean of 8.5 ± 2 months for bilateral RB, and 25.8 ± 5.5 months for unilateral RB. Of the 162 eyes with RB (64 unilateral and 49 bilateral), 11 (6.8%) eyes had group A, 23 (14.1%) eyes had group B, 10 (6.2%) eyes had group C, 16 (9.9%) eyes had group D and 102 (63%) eyes had group E RB at presentation. Ninety-three eyes (57.4%) underwent enucleation and globe salvage was possible in 69 eyes (42.6%). High-risk features on histopathological examination were noted in 12 of the 93 eyes (13%). Seven patients had a family history of RB, and 30 had a family history of other cancers.

Mutation spectrum and germline alteration in RB1

With the combination of Sanger sequencing and MLPA, germline RB1 mutations were identified in 61 of 113 (54%) patients. The total mutation detection rate was 96% (47/49) and 22% (14/64) for bilateral and unilateral RB, respectively. The spectrum of mutations identified in 61 patients included 19 (31%) splice, 16 (26%) nonsense, 12 (20%) frameshift, 3 (5%) missense mutations along with 9 (15%) exonic deletion/duplications and 2 (3%) gross RB1 deletions (Fig. 1A). Germline mutation details are represented in Fig. 1B. The distribution of these mutations in unilateral and bilateral cases is depicted in Table 1. About 59% (36/61) of mutations were disrupting the pocket domain (Pocket A-21/36, Pocket B-15/36) of RB protein (pRB). Ten novel RB1 mutations (16.4%) were found in 7 bilateral and 3 unilateral cases (Table 1). The pathogenicity of all the novel mutations including three splice and seven null mutations was predicted by mutation taster and varsome (Table 2). The null mutations consisted of two nonsense (p.Cys169*, p.Leu523*), four frameshift mutations (p.Leu337Trpfs*12, p.Asp338Ilefs*11, p.Pro568Asnfs*3, p.Leu694Thrfs*27), and one start loss mutation (p.M1?).

Fig. 1. Distribution and schematic representation of mutations across RB1 gene.

A Types of mutations detected in our probands. B Mutational spectrum across RB1 gene: Mutation types with their frequencies are marked to relative exons. Novel mutations are highlighted in boxes. Gross RB1 deletion and duplications are represented in brown and yellow line bars, respectively.

Table 1.

RB1 mutational types with clinical profiles.

| Total number of probands | Number of bilateral cases | Number of unilateral cases | Mean age at diagnosis(months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non sense | 16 | 15 | 1 | 10.5 |

| Frameshift | 12 | 9 | 3 | 9.1 |

| Splicing | 19 | 12 | 7 | 15.2 |

| Missense | 3 | 1 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Exonic Deletion/Duplication | 9 | 8 | 1 | 6.2 |

| Large Deletion/Duplication | 2 | 2 | - | 6.5 |

| Total | 61 | 47 | 14 | 10.7 |

Table 2.

Novel germline RB1 mutations identified in our study cohort.

| Patient ID | Exon | cDNA Change | Protein change | Mutation Taster | Human Splice finder | ACMG Evidence | ACMG classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R109# | Exon 1 | c.-1_1del | p.M1? | PVS1, PM2 | LP | ||

| R215 | Exon 5 | c.507 T > A | p.Cys169* | PVS1, PM2 | P | ||

| R114 | Intron 5 | c.539+5 G > A | Splicing | Broken WT Donor Site | PP3, PM2 | VUS | |

| R188 | Exon 10 | c.1006delT | p.Leu337Trpfs*12 | Disease Causing | PVS1, PM2 | LP | |

| R237 | Exon 10 | c.1011delG | p.Asp338Ilefs*11 | Disease Causing | PVS1, PM2 | LP | |

| R174 | Exon 17 | c.1566delT | p.Leu523* | Disease Causing | PVS1, PP5, PM2 | P | |

| R171 | Exon 18 | c.1701_1722del | p.Pro568Asnfs*36 | Disease Causing | PVS1, PM2 | LP | |

| R258# | Exon 20 | c.2079_2080insA | p.Leu694Thrfs*27 | PVS1, PM2 | LP | ||

| R117 | Intron 24 | c.2521-12 T > G | Splicing | Broken WT Acceptor Site | PP3, PM2 | VUS | |

| R204 | Intron 25 | c.2663+58del | Splicing | Activation of a cryptic Donor site. | BP4, PM2 | LB |

WT wild type, LP likely pathogenic, P pathogenic, VUS variants of uncertain significance, LB likely benign; # Low penetrant variants

In bilateral RB, blood samples revealed nonsense mutations predominantly (n = 15, 32%), followed by deletion (n = 9, 19%) and frameshift mutation (n = 9, 19%). An altered splice site was the most common mutation found in unilateral RB (n = 7). We noted a low incidence of missense mutations (n = 3) and synonymous variants (n = 2) in our study cohort. In 4% (2/47) of bilateral cases, no germline RB1 mutation was detected possibly due to low level germline mosaicism which cannot be detected by the methods used in the study. Furthermore, 6 point mutations occurred more than once in 12 unrelated RB cases. These recurrent mutations comprised 19.6% (12/61) of all identified mutations. The most frequent recurring mutation was nonsense. Among them, p.Arg251*, p.Arg455*, p.Arg556*, and p.Arg787* were found in two cases each. Another two were splice mutations which occurred twice in 4 unrelated patients.

Analysis of the parental transmission of mutant alleles revealed 16 out of 61 cases (26%) with positive transmission of the variant alleles from parents. Out of these, 11 parents were unaffected (18%), indicating incomplete penetrance (Fig. 2). The origin of the variant allele was both paternal (n = 7) and maternal (n = 4) wherein five were bilateral and six unilateral. We report two novel low penetrant variants in patients R109 and R258 (Table 2). The rest 45 out of 61were de novo germline mutations. The mutations p.Leu337Trpfs*12and p.Arg556* were observed in patients with secondary neoplasms like osteosarcoma and lower limb cancer. Similarly, p.Ala15profs*3 and p.Gln575* were de novo mutations observed in discordance among triplet and twin siblings, respectively; only the children with mutation were affected and siblings were unaffected.

Fig. 2. Representative pedigree of families with low penetrance RB1 mutation.

Family A: Father is a normal carrier of the heterozygous mutation: c.-1_1delCA; Frameshift mutation. The proband and two siblings carry the same heterozygous mutation. Family B: Father is an unaffected carrier of the heterozygous mutation: dup-exon 21-26; Exon Duplication. The proband and one among the two siblings carry the mutation.

The mean age of RB diagnosis was significantly different between patients with detected RB1 mutation (mean 10.7 months ±2.5) and with no germline RB1 mutation (mean 27.2 months ±6.5) (p = <0.0001) (one-way ANOVA). There was no significant difference between the type of mutation and the mean age at diagnosis (Table 1). The mean age at diagnosis for bilateral RB was lower than that for unilateral RB among the patients with mutations, (p = 0.0172). Out of patients with germline mutation who underwent enucleation, 6 (3 unilateral and 3 bilateral) had high-risk features on histopathology. Out of these 6 patients, 3 had splice, 2 had nonsense and 1 had frameshift mutations.

Discussion

The present study involves the germline screening of RB1 gene for 113 probands and their family members done on a single day, using PCR, Sequencing and MLPA. We report a germline mutation detection rate of 53.6%, which is higher than other reports where the reported mutation detection rate in blood ranges from 42-49% [12–14]. The combination of Sanger sequencing and MLPA increased the sensitivity of detecting germline mutations thus, reducing the risk of obtaining false-negative results [14–16]. A recent study had detected germline mutation of about 19.5% in unilateral cases [12]. We had detected germline mutation in 21.8% of unilateral cases, which is much higher compared to classic reports in the literature of about 15% [2].

Patients with bilateral RB are expected to test positive for a germline mutation in the RB1 gene. In our cohort, two bilateral patients didn’t show any germline mutation. These undetectable mutations in the patients could be due to the presence of low-level mosaicism or deep intronic variants which can be detected through sensitive techniques like allele-specific PCR or next-generation sequencing only which was not done as part of our study [17].

Nonsense mutations are reported to be the most common type but were the second most common in our cohort after altered splice site mutation [13, 15]. About 59% of the mutations were in the pocket domain (Exon 12-23) of the pRB protein. Most of the mutations reported were predicted to affect the function of pRB through premature termination codon, producing unstable mRNA and/or protein truncation. Carriers of RB1 alleles with nonsense or frameshift mutations tend to develop bilateral RB, and in our study as well, these two types of mutations were the most common (32 and 19% respectively) among bilateral RB patients. Among the unilateral tumours in our cohort, an altered splice site was the most common mutation. It has been reported that mutations that affect splice signals are more likely to be associated with unilateral RB or incomplete penetrance [18]. The phenomenon of inheriting a potentially deleterious variant from an unaffected parent who lacks any disease-related phenotype is explained by low-penetrance mutation. Such asymptomatic carriers usually have the proband’s mutation as a single recessive mutant allele or rarely, a dominant variant [12]. In our cohort, 11 set of parents had such mutations without RB. The clinical phenotype of these carriers is generally either within the range of normal healthy variations, or gets incidentally detected when screened with the perspective of their offspring having a tumour [19]. Low penetrant mutations are said to have residual pRB function because of the subtle effect on the tertiary structure of pRB. This type of mutation is known as a weak allele, resulting in a variant of pRB that can suppress tumorigenesis in the biallelic state but not in the monoallelic state [19]. The influence of the nature of the mutation on penetrance and expressivity has been well-studied in heritable RBs [19]. Splice (4/11 in our cohort), missense (2/11 in our cohort) and in-frame mutations are known to be associated with incomplete penetrance or milder expressivity [19, 20]. In many instances of familial RB, previous generations were found to have retinocytomas on family screening and had never presented to an ophthalmic centre prior to this. Silent retinocytoma without any progression or visual sequelae go undetected. As we only tested the blood of patients having a tumour, it does not give a true assessment of the incidence of carrier state, as children who did not develop the tumour did not need to seek treatment.

Impact

In unilateral non-germline cases: In the absence of genetic testing, unilateral RB cases require surveillance for the development of tumours in the other eye, until 7 years often requiring EUA, depending on cooperation for complete examination. 1In our cohort 50 out of 64 unilateral patients who tested negative for germline mutation were from frequent EUA for other eye surveillance. Guidelines established indicated a requirement of up to 24 EUA, which even by the most modest estimate could amount up to 1440 (60×24) USD, excluding the cost of travel for the family. By this estimate, families, especially of unilateral non-germline cases, who underwent primary enucleation, could be saved from unnecessary financial burden and repeated EUA. Carriers of germline mutation are at risk of second cancers later in life, including bone tumours, soft tissue sarcomas and melanoma [21]. The unilateral non-germline patients were free from risk of second malignancies and also had decreased risk of tumour in their future progeny (<1% vs 45% in mutation-positive). Investigating mutations in both alleles in the tumour whenever accessible is of significant importance in unilateral RB but was not analysed as a part of this study [2].

In unilateral germline cases: Unilateral germline cases advised closer surveillance for early detection of tumours in the other eye, especially if they were very young at the time of presentation. Because of genetic testing, we were able to segregate patients harbouring mutations and counsel them for the same. Additionally, we could accurately access the risk in progeny (45%) and that had future implications like prenatal genetic testing [22].

Post-testing surveillance often re-emphasizes the predictions made from the genetic testing.

Although the genetic testing was done in 2017, certain scenarios that we have elaborated here, retrospectively highlighted the advantages of genetic testing in risk prediction in the next pregnancy as well as early treatment in next sibling, prompting us to revisit our genetic data at a 5-year follow-up period.

One patient in our cohort (Patient R240, Fig. 3), having no family history, was diagnosed at 1 month of age with bilateral RB. She underwent enucleation in one eye, which showed high-risk features on histopathological examination. Despite adjuvant chemotherapy, the other eye had multiple reactivations but ultimately globe salvage was possible. On genetic testing, she had a heterozygous deletion of the whole RB1 gene, and the same mutation was also detected in the father. At the time of genetic testing, she was the only child however subsequently, her sister was born in 2021, who underwent screening at 5 days and was found to have a unilateral tumour, for which she was treated currently both siblings are under follow-up. This is an example of variable expressivity in the family. The genetic testing in this case (and many such cases in our experience) has been of benefit to the family as a whole. In this case, we predicted the development of tumour in the second sibling and started early screening which, in turn, helped in maximum salvage of the eye and vision. (Fig. 3) Similarly, Soliman et al., have accentuated the impact of pre- and post-natal genetic screening on RB management in children’s carry their family’s RB1 mutant allele [23].

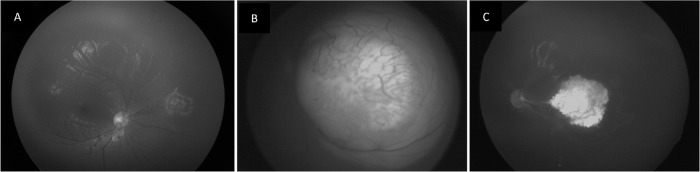

Fig. 3. Post testing surveillance in familial RB.

A Right eye showing regressed retinoblastoma in a child with bilateral tumour with left eye enucleated. Unilateral retinoblastoma in left eye of the sibling of the above child, screened at 5 days of birth - Group B RB at presentation (B) and type 1 regression at final follow up (C).

In the context of familial and germline tumours, postnatal diagnosis of familial RB may still be too late to save good vision. The option of prenatal genetic testing is available by chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis and if the foetus carries the familial mutation, the parents can decide to opt for abortion or continue the pregnancy with the knowledge of the risks involved [22]. These procedures involve some risk of foetal loss [24]. Also, these procedures require swift decision-making due to the narrow time frame for intervention. Additionally, in the Indian scenario, there are multiple social taboos associated with the termination of pregnancy and limited availability of resources. One of our patients, being treated for bilateral RB, and her mother who underwent enucleation for RB I in her childhood, was found to harbour a heterozygous mutation (deletion of 2 bases in exon 5-c.513_514delTA) in their blood. In the next pregnancy, her mother opted for chorionic villus sampling (CVS) and genetic testing. Since the mutation was detected in the blood of the foetus, the couple took the decision of termination of pregnancy (MTP) and are keen to plan for in-vitro fertilization with a preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

With improvements in reproductive medicine, we can offer a preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) with in vitro fertilization of an embryo free of the mutation even in a developing country like ours [25]. More conservative approaches include non-invasive prenatal diagnosis analysing cell-free foetal DNA within the mother’s blood, which offers a safer alternative to invasive prenatal diagnostic procedures [26]. It is possible to detect the tumour while in utero with obstetric ultrasound [27]. The option of preterm delivery can be offered with the intention to treat the tumours while they are still smaller, for better chances of eye preservation and maximize visual outcome [23].

Social impact

An initiative such as this encouraged the interaction between impacted families and led to the formation of a sort of defacto cancer support group which is otherwise rare in our country wherein families of survivors provided motivation and courage to families of newly detected patients.

A limitation of our study was that we were unable to analyse blood samples from 3 generations, which would have given us better insights into penetrance.

Unlike many other ophthalmic genetic diseases where the importance of genetic testing offers few therapeutic benefits, in RB, the result of genetic testing often offers a guide for the management of not only the proband, but also the family members especially subsequent generations. With a developing economy, improved educational backgrounds, access to information, and families getting smaller, more families are opting for genetic testing.

Research directed toward genotype-phenotype correlation can help us understand the mechanisms that can be used to reduce the risk of tumour development in children that have inherited an oncogenic RB1 allele, for the development of future therapeutic ventures. Further testing for mutations in mosaic states and deep intronic mutations will eventually lead to an even higher mutation detection rate that will result in more accurate risk estimation, which will alter the management and reproductive decisions. To conclude, the detection of a germline mutation impacts the proband and the family members due to its implications on the change in prognosis, and subsequent evaluations including follow-ups for ocular and non-ocular cancers, and surveillance of the family.

Summary

What was known before:

The major hindrances of molecular testing for genetic diseases in developing countries include the lack of accessibility to these resources and the affordability of such testing

What this study adds:

We were able to conduct a mass genetic testing for our retinoblastoma survivors on the occasion of world retinoblastoma awareness week and here we have highlighted the impact of our unique initiative. In this study, we have identified germline RB1 mutations in 61/113(54%) probands with a mutation detection rate of 22% (14/64) in unilateral RB cases. Ten novel pathogenic mutations were also identified. The detection of a germline mutation impacts the proband and the family members due to its implications on the change in prognosis, and subsequent evaluations including follow-ups for ocular and non-ocular cancers, and surveillance of family.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our patients who participated in our study. We would also like to thank Sun Foundation and our colleagues in the department of vitreoretinal and molecular genetics for providing their support.

Presentations Part of this study was presented at the International Society of Genetic Eye Diseases and Retinoblastoma, Giessen, Germany, August 29–31, 2019.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation- PKS and AV, data curation-PKS, PM and AV, data analysis- PM, KKS and AV, paper writing- PM, KKS, PKS and AV. All authors accepted the final draft of the paper.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee, PSG IMS&R (Project number 17/109).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Knudson AG. Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:820–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soliman SE, Racher H, Zhang C, MacDonald H, Gallie BL. Genetics and molecular diagnostics in Retinoblastoma-An Update. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol. 2017;6:197–207. doi: 10.22608/APO.201711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athavale V, Khetan V. Knudson to embryo selection: A story of the genetics of retinoblastoma. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2018;8:196–204. doi: 10.4103/tjo.tjo_37_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dryja TP, Mukai S, Petersen R, Rapaport JM, Walton D, Yandell DW. Parental origin of mutations of the retinoblastoma gene. Nature. 1989;339:556–8. doi: 10.1038/339556a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu XP, Dunn JM, Phillips RA, Goddard AD, Paton KE, Becker A, et al. Preferential germline mutation of the paternal allele in retinoblastoma. Nature. 1989;340:312–3. doi: 10.1038/340312a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla B, Hasan F, Azad R, Seth R, Upadhyay AD, Pathy S, et al. Clinical presentation and survival of retinoblastoma in Indian children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:172–8. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah PK, Narendran V, Kalpana N. Outcomes of intra- and extraocular retinoblastomas from a single institute in South India. Ophthalmic Genet. 2015;36:248–50. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2013.867450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francis JH, Roosipu N, Levin AM, Brodie SE, Dunkel IJ, Gobin YP, et al. Current treatment of bilateral retinoblastoma: the impact of intraarterial and intravitreous chemotherapy. Neoplasia. 2018;20:757–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linn Murphree A. Intraocular retinoblastoma: the case for a new group classification. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2005;18:41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ohc.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thirumalairaj K, Abraham A, Devarajan B, Gaikwad N, Kim U, Muthukkaruppan V, et al. A stepwise strategy for rapid and cost-effective RB1 screening in Indian retinoblastoma patients. J Hum Genet. 2015;60:547–52. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomar S, Sethi R, Sundar G, Quah TC, Quah BL, Lai PS. Mutation spectrum of RB1 mutations in retinoblastoma cases from Singapore with implications for genetic management and counselling. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0178776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahraki K, Ahani A, Sharma P, Faranoush M, Bahoush G, Torktaz I, et al. Genetic screening in Iranian patients with retinoblastoma. Eye. 2017;31:620–7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lan X, Xu W, Tang X, Ye H, Song X, Lin L, et al. Spectrum of RB1 germline mutations and clinical features in Unrelated Chinese patients With Retinoblastoma. Front Genet. 2020;11:142. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sagi M, Frenkel A, Eilat A, Weinberg N, Frenkel S, Pe’er J, et al. Genetic screening in patients with Retinoblastoma in Israel. Fam Cancer. 2015;14:471–80. doi: 10.1007/s10689-015-9794-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohd Khalid MKN, Yakob Y, Md Yasin R, Wee Teik K, Siew CG, Rahmat J, et al. Spectrum of germ-line RB1 gene mutations in Malaysian patients with retinoblastoma. Mol Vis. 2015;21:1185–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushlow D, Piovesan B, Zhang K, Prigoda-Lee NL, Marchong MN, Clark RD, et al. Detection of mosaic RB1 mutations in families with retinoblastoma. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:842–51. doi: 10.1002/humu.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohmann DR, Gallie BL. Retinoblastoma: revisiting the model prototype of inherited cancer. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;129C:23–28. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harbour JW. Molecular basis of low-penetrance retinoblastoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1699–704. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.11.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lohmann DR, Brandt B, Höpping W, Passarge E, Horsthemke B. Distinct RB1 gene mutations with low penetrance in hereditary retinoblastoma. Hum Genet. 1994;94:349–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00201591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ketteler P, Hülsenbeck I, Frank M, Schmidt B, Jöckel K-H, Lohmann DR. The impact of RB1 genotype on incidence of second tumours in heritable retinoblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 2020;133:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah PK, Sripriya S, Narendran V, Pandian AJ. Prenatal genetic diagnosis of retinoblastoma and report of RB1 gene mutation from India. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016;37:430–3. doi: 10.3109/13816810.2015.1107595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soliman SE, Dimaras H, Khetan V, Gardiner JA, Chan HSL, Héon E, et al. Prenatal versus postnatal screening for familial retinoblastoma. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2610–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akolekar R, Beta J, Picciarelli G, Ogilvie C, D’Antonio F. Procedure-related risk of miscarriage following amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:16–26. doi: 10.1002/uog.14636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu K, Rosenwaks Z, Beaverson K, Cholst I, Veeck L, Abramson DH. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis for retinoblastoma: the first reported liveborn. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:18–23. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00872-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerrish A, Bowns B, Mashayamombe-Wolfgarten C, Young E, Court S, Bott J, et al. Non-invasive prenatal diagnosis of retinoblastoma inheritance by combined targeted sequencing strategies. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3517. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manjandavida FP, Xia J, Zhang J, Tang XY, Yi HR. In-utero ultrasonography detection of fetal retinoblastoma and neonatal selective ophthalmic artery chemotherapy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019;67:958–60. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_340_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.