INTRODUCTION

Paroxysmal bundle branch block (BBB) is a transient intraventricular conduction defect that terminates spontaneously or with an intervention. In contrast, intermittent BBBs are defined as the co-existence of BBB and normal conduction on the same electrocardiogram (ECG). Paroxysmal BBB has been reported with conditions such as anaesthesia, cardiac catheterisation, acute pancreatitis, pulmonary embolism, thoracic trauma and sudden changes in intrathoracic pressure, drugs (e.g. flecainide and propafenone) and poisonings such as mad honey and digitalis.[1]

BBB distorts the morphology of the ECG and makes the interpretation of ST–T changes difficult. A new or presumably new-onset BBB in an appropriate setting is pathological with management similar to an ST–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).[2] In a recent registry, the prevalence of left BBB (LBBB) was around 2%.[3] Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) associated with a BBB has a higher risk of adverse cardiac events and mortality, especially with right BBB (RBBB).[4,5] The evidence or guidance on the management approach to transient BBB during the perioperative period is lacking.

The current meta-summary aims to analyse all published case reports on transient BBB during the perioperative period among patients of any age to evaluate their characteristics, management and outcomes.

METHODS

A systematic search was conducted through PubMed, Science Direct, Reference Citation Analysis, Cochrane and Google Scholar by using keywords ‘Bundle–Branch Block’ OR ‘Bundle Branch Block’ OR ‘Left Bundle–Branch Block’ OR ‘Right Bundle-Branch Block’ AND ‘Perioperative Period’ OR ‘Intraoperative Period’ OR ‘Postoperative Period’ OR ‘Preoperative Period’ OR ‘Anesthesia’ OR ‘Anaesthesia’. Furthermore, it was filtered for the literature published from January 1, 1970 till March 31, 2022. The inclusion criteria were case reports in humans of any age with individual patient details on BBB during the perioperative period. Animal studies and languages other than English were excluded.

The data were extracted from case reports on patient demographics, country of origin, comorbidities, surgical procedure, anaesthesia, type of BBB, haemodynamic alterations and their management and outcomes. The prepared datasheet was evaluated using Excel and Microsoft Office 2021. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage. Median (interquartile range, IQR) was used for continuous variables.

RESULTS

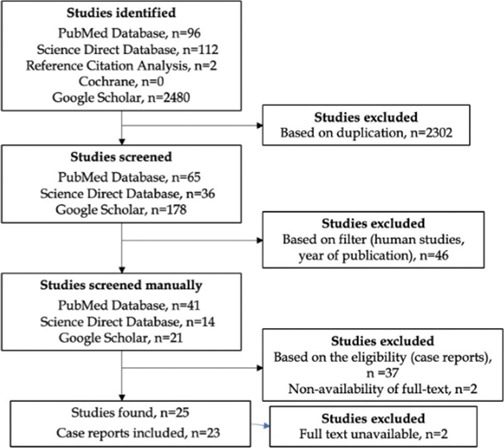

The systematic search of the databases found 25 case reports of transient BBB during the perioperative period. Finally, 23 case reports involving 24 patients were analysed [Figure 1]. Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity (37.5%), followed by coronary artery disease (CAD) and obesity in four (16.7%) patients each. Fourteen patients (49.3%) were on long-term medications such as aspirin (16.7%), beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers (8.3% each) [Table 1].

Figure 1.

The study selection flow for the meta-summary. n: Number

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients and bundle-branch block

| Variables | Patients (n=24) |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 60 (45–69) |

| Female, n | 14 |

| Country of origin, n | United States of America, 8 |

| Japan, 6 | |

| India, 4 | |

| Canada, 1 | |

| France, 1 | |

| Malaysia, 1 | |

| Portugal, 1 | |

| South Korea, 1 | |

| United Kingdom, 1 | |

| Previous Medication, n | Calcium channel blockers, 2 |

| Aspirin, 4 | |

| Beta-blocker, 2 | |

| Lithium, 2 | |

| Statins, 2 | |

| Not mentioned, 4 | |

| None, 10 | |

| Surgical site, n | Abdomen, 11 |

| Dental and maxillofacial, 4 | |

| Thoracic (non-cardiac), 3 | |

| Orthopaedics (limbs), 3 | |

| Central nervous system, 2 | |

| Vascular, 1 | |

| Type of BBB, n | Left bundle-branch block, 21 |

| Right bundle-branch block, 3 | |

| Intermittent, 6 | |

| Rate-dependent bundle-branch block, 14 | |

| Haemodynamic alterations, n | Hypertension, 3 |

| Hypotension, 1 | |

| None, 10 | |

| Treatment, n | Deepening the level of anaesthesia, 8 |

| Discontinuation of anaesthesia, 3 | |

| Carotid sinus massage, 2 | |

| Medications | |

| Beta-blockers, 3 | |

| Atropine, 1 | |

| Nitro-glycerine, 1 | |

| Calcium channel blockers, 1 | |

| Amiodarone, 1 | |

| None, 9 | |

| Follow-up investigations, n | Cardiac enzymes, 13 |

| Holter, 7 | |

| Coronary angiography, 2 | |

| Dobutamine stress echocardiography, 2 | |

| None, 2 | |

| Outcome, n | Alive, 24 |

n=numbers

Most patients developed BBB while on general anaesthesia (GA), with combined intravenous and inhalation anaesthetics used in 23 patients. Sevoflurane was used in seven patients and isoflurane in another three. Most patients (21) developed LBBB, which was paroxysmal (17) and without any haemodynamic alterations except tachycardia (13). The median duration of BBB was 20 minutes, ranging from 5 minutes to 6 hours. Pharmacological agents to abort paroxysmal BBB were used in only seven patients. All patients were discharged alive, but surgery was deferred in four patients [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

Intraoperative transient BBBs are mostly paroxysmal, with tachycardia-associated rate-dependent LBBB being the more common type. However, unless related to haemodynamic alterations, surgery can be continued safely in most patients.

The mechanism of a tachycardia-dependent BBB is phase-3 block, characterised by impulse reaching tissue in its refractory period (due to incomplete repolarisation). The bradycardia-dependent blocks caused by phase-4 block are rare and usually associated with structural heart disease.[6] Another mechanism for rate-dependent LBBB is the ‘linking’ phenomenon. Linking is characterised by the propagation of functional antegrade BBB by concealed trans-septal retrograde impulses along the contralateral bundle branch.[7] Some features of ECG may help to predict transient BBB. T-wave inversion in the apical and right-precordial leads is common with intermittent BBB and reflects the normal ventricle activation after a period of abnormal conduction (cardiac memory). Cardiac memory is not pathognomonic of transient BBB and known in ventricular tachycardia, ventricle pacing and intermittent ventricle pre-excitation.[1,8]

Most case reports were described for paroxysmal BBB. Paroxysmal BBBs during GA were attributed to perturbations in the heart rate[9,10] or blood pressure.[11] However, the exact pathophysiology of paroxysmal BBB is unclear. Only one-third of patients with transient BBB had spontaneous remission. Non-pharmacological interventions such as alteration of the depth of the anaesthesia or carotid sinus massage were effective in most patients. Pharmacological interventions for controlling heart rate and blood pressure were required in the remaining patients. No mortality was reported in this meta-summary. However, the bias caused by reporting only favourable outcomes cannot be excluded. Rate-dependent transient LBBB in non-perioperative settings has been reported with myocardial ischaemia and coronary vasospasm.[12] The symptoms of myocardial ischaemia can be obscured under the effect of anaesthetic drugs. The haemodynamic impact of BBB may help to decide the urgency of the management and further diagnostics. However, excluding ACS with new-onset LBBB perioperatively is imperative for patient safety. Though the surgery was continued in most patients, it should be deferred or cancelled in case of haemodynamic instability with urgent cardiologist consultation. The authors recommend a formal assessment and exclusion of CAD in patients with a previous history of CAD or comorbidities associated with CAD.

This is the first meta-summary of all case reports published on the paroxysmal BBB during the perioperative period. However, there exist some limitations to this meta-summary. Several intraoperative transient BBBs may not be reported unless they have unique or rare clinical presentation and management.

CONCLUSION

Transient rate-dependent BBB can appear intraoperatively in patients on GA. Surgery can be continued safely in the absence of haemodynamic alterations. Despite their innocuous nature, careful monitoring of perioperative haemodynamic stability and exclusion of CAD in patients with significant risk factors is warranted. Future studies should identify the incidence and outcomes of transient BBB through large databases during the perioperative period.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Prashant Nasa declared to be on the advisory board of Edwards Life Sciences. Other authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bazoukis G, Tsimos K, Korantzopoulos P. Episodic left bundle branch block-A comprehensive review of the literature. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2016;21:117–25. doi: 10.1111/anec.12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–77. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel A, Gehani AA, Singh R, Albinali H, Arabi A. Left bundle branch block in acute cardiac events: Insights from a 23-year registry. Angiology. 2015;66:811–7. doi: 10.1177/0003319714560223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timóteo AT, Mendonça T, Aguiar Rosa S, Gonçalves A, Carvalho R, Ferreira ML, et al. Prognostic impact of bundle branch block after acute coronary syndrome. Does it matter if it is left or right? Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2018;22:31–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko HC, Cho YH, Jang W, Kim SH, Lee HS, Ko WH. Transient left bundle branch block after posture change to the prone position during general anesthesia: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25190. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frisch DR, Zimetbaum PJ, Josephson ME. Alternating left bundle branch block and right bundle branch block during tachycardia: What is the mechanism? Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:679–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erdogan O, Altun A. Electrocardiographic demonstration of intermittent left bundle branch block because of the “linking” phenomenon. J Electrocardiol. 2002;35:143–5. doi: 10.1054/jelc.2002.31823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Birnbaum Y, Ye Y, Smith SW, Jneid H. Rapid diagnosis of STEMI equivalent in patients with left bundle-branch block: Is it feasible? J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e023275. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chavali S, Singh GP, Prabhakar H, Chaturvedi A. Recurrent transient episodes of left bundle branch block immediately following surgery - A rare phenomenon. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63:153–5. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_637_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra S, Nasa P, Goyal GN, Khurana H, Gupta D, Bhatnagar S. The rate dependent bundle branch block -- Transition from left bundle branch block to intraoperative normal sinus rhythm. Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2009;20:295–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rewari V, Ramachandran R, Parakh N, Singh P, Jayanandan SE. Intraoperative interfascicular ventricular tachycardia: A rare occurrence. Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58:76–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.126807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alhaji M. Intermittent left bundle branch block caused by coronary vasospasm. Avicenna J Med. 2013;3:50–2. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.114129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]