Background

Anorectal malformations (ARM) are a group of rectal and anal birth defects with a European prevalence of about 1 in 2500–5000 live births1–4. These rare and complex conditions require highly specialized reconstructive surgery in early life, often with a temporary defunctioning stoma5–7. ARM are associated with other organ anomalies in 58–78% of patients; therefore, all ARM newborns should be screened for associated anomalies2,5,8–11. The introduction of posterior sagittal anorectoplasty has improved the management of ARM in recent decades12. Nevertheless, problems with bowel function can remain throughout adulthood and compromise quality of life13–20.

With the rarity of ARM, specialized centres see 5–20 new patients each year21 and knowledge on epidemiology, demographics, treatment strategies and outcomes is scattered. In 2010, the Anorectal Malformation Network (ARM-Net) Consortium, a group of European paediatric surgeons, patient advocacy groups, geneticists, epidemiologists and psychologists, established a patient registry22. The ARM-Net registry represents the collaboration among multiple paediatric surgical centres with a wide geographical coverage22–36. Since its inception, more than 2600 patients have been registered. The aim of this study is to describe the clinical and surgical characteristics of ARM patients in the registry.

Methods

Objectives

The primary objective of this retrospective cohort study was to describe patients treated within the ARM-Net Consortium in terms of demographics, diagnostics, clinical characteristics including associated anomalies, surgical details including type of reconstruction, stoma placement, complications, and functional outcomes one year after reconstructive surgery. Secondary objectives were to investigate the relations between associated anomalies and ARM types, and timing of reconstructive surgery.

Subjects and data collection

ARM patients under 18 years of age treated in one of the ARM-Net Consortium and registered in the ARM-Net registry until 1 March 2023 were included. Each centre has a lead paediatric surgeon who is responsible for patient registration and data collection at their respective centre. Patient data are de-identified and pseudonymized before collection. Surgeons can only re-identify their own patients with personal code-breaking documentation. Data on demographics, ARM type according to Krickenbeck classification33,37, diagnostic screening and associated anomalies, surgical details and complications, and one-year follow-up functional outcomes are collected.

Renal, bladder, cardiac, tracheoesophageal, genital, skeletal, vertebral, sacral, spinal cord, and brain-associated anomalies, but also other (minor) anomalies, could be registered. Data on genetic studies were collected, including the presence of a syndrome or association. Surgical information included dates and types of stoma and anorectal reconstruction, and postoperative complications (for example infection, wound dehiscence, urethral injury, stenosis, recurrent fistula, or insufficient reconstruction requiring redo surgery). Data on short-term colorectal outcome one year after reconstruction were collected, including constipation and treatment, faecal consistency and frequency, anal dilatations, and late complications including perianal dermatitis and rectal mucosal prolapse, assessed at the surgeons’ discretion. Surgeons were at liberty to provide additional information in the free-text sections.

Records with more than 25% missing data for closed-ended items were excluded from our analyses.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed for patient demographics, ARM phenotype, clinical characteristics including associated anomalies, surgical details including complications, and functional outcomes one year after reconstruction. Patients with reconstruction within one year of 1 March 2023 were excluded from the follow-up analyses. To calculate patients’ age at time of surgery, date of birth and surgery used the 15th of the month, due to availability of month and year only. Mother’s approximate age at time of patient’s birth was calculated using birth year of mother and patient.

Logistic regression modelling estimated ORs and 95% c.i. for associations between accompanying anomalies and ARM phenotypes, using perineal fistula as the reference. Associations between anomalies and median age at time of reconstruction were examined using Mann–Whitney U-tests, and using chi-squared tests when age was categorized into older or younger than 3 months. All statistical tests were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Data were exported from the ARM-Net registry online database, cleaned with OpenRefine (v.3.4.1; 437dc4d, Google Inc. and contributors) and further cleaned and analysed in SPSS Statistics (version 29.0.0.0; 241, IBM Corporation, Armonk, USA).

Results

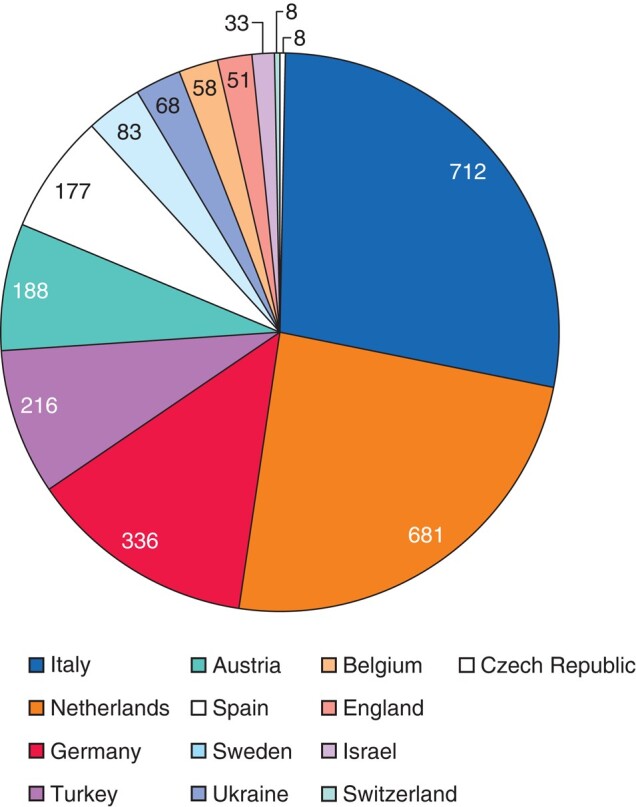

There were 2627 patients included in the ARM-Net registry. Eight records with more than 25% missing data were excluded, resulting in a total of 2619 patients included for analysis. Patients were registered through 34 different European centres (Fig. 1). Patient sex distribution was equal, and the most common ARM phenotype was perineal fistula for both sexes (41.5%), followed by vestibular fistula (31.8%) and cloaca (8.8%) in females, and rectobulbar (16.8%) and rectoprostatic fistula (15.0%) in males (Table 1). Patients were born to mothers with a median age of 32 years (i.q.r. 28–36).

Fig. 1.

ARM patients in the ARM-Net registry per country (N)

Table 1.

ARM patient characteristics of the ARM-Net registry

| N (%*) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 1314 (50.4) |

| Female | 1292 (49.6) |

| Twins | 101 (3.9) |

| Mother's age at childbirth in years (median, IQR) | 32 (28-36) |

| Krickenbeck classification | |

| Perineal fistula | 1086 (41.5) |

| Vestibular fistula (only female) | 415 (15.8) |

| Rectobulbar fistula (only male) | 222 (8.5) |

| Rectoprostatic fistula (only male) | 198 (7.6) |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula (only male) | 66 (2.5) |

| Rectourethral fistula unspecified (only male) | 51 (1.9) |

| Anal atresia without fistula | 162 (6.2) |

| Anal stenosis | 53 (2.0) |

| Cloaca (only female) | 113 (4.3) |

| <3cm common channel | 65 (2.5) |

| >3cm common channel | 29 (1.1) |

| unspecified common channel | 19 (0.7) |

| Rare types: | |

| Ventrally dystopic anus | 13 (0.5) |

| Rectal stenosis | 17 (0.6) |

| Rectal atresia | 16 (0.6) |

| Cloacal exstrophy | 18 (0.7) |

| Rectovaginal fistula (only female) | 18 (0.7) |

| H-type fistula | 12 (0.5) |

| Pouch colon | 7 (0.3) |

| Other | 50 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 102 (3.9) |

| Genetic diagnosis confirmed† | 298 (11.4) |

| Down Syndrome | 65 (2.5) |

| Cat Eye Syndrome | 21 (0.8) |

| Townes-Brocks Syndrome | 15 (0.6) |

| Currarino Syndrome or HLXB9 mutation | 14 (0.5) |

| VACTERL Association‡ | 11 (0.4) |

| Pallister-Hall Syndrome | 4 (0.2) |

| Other (including chromosomal aberrations) | 168 (6.4) |

*Of total known data, excluding unknown or missing data. †All other patients have no confirmed genetic diagnosis or results are pending at time of analysis. ‡This diagnosis was provided by the pediatric surgeon, not by checking the combination of anomalies for the VACTERL association entered (11). IQR, interquartile range.

Associated congenital anomalies

A minority of patients (11.4%) had a confirmed genetic diagnosis at time of analysis, and 31.7% of ARMs were isolated, without any associated anomalies. Frequency of associated anomalies is presented in Table S1.

Significant associations between ARM phenotypes and other anomalies were found (Table 2). Patients with vestibular fistula, rectourethral fistula (any type), recto-bladder neck fistula, cloaca, no fistula, or the group rare and other types were each more likely to have any associated anomalies compared to patients with perineal fistula. The same was true for skeletal, renal, bladder and genital anomalies separately. Patients with vestibular, rectourethral or recto-bladder neck fistula were more likely to have cardiac, spinal or tracheoesophageal anomalies than perineal fistula patients. There was no increased risk for cardiac anomalies in patients with cloaca or the group rare and other types, or for spinal anomalies in patients with no fistula, compared to perineal fistula patients. Patients with anal stenosis were not more likely to have any associated anomalies than patients with perineal fistula. Patients with no fistula had a two-fold increased risk for brain anomalies compared to perineal fistula patients, but this was not associated with Down syndrome (P = 0.469). Furthermore, there was no association between complex ARM types and any genetic abnormality (P = 0.123).

Table 2.

Congenital anomalies associated with ARM Krickenbeck phenotypes

| Associated anomalies | Krickenbeck type | N (%*) | OR | CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any anomaly

Sex Male (%): 949 (53.2) Female (%)* : 835 (46.8) |

Perineal fistula | 586 (54.0) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 314 (75.7) | 2.7 | 2.1-3.4 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 398 (84.5) | 4.7 | 3.5-6.1 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 60 (90.9) | 8.5 | 3.7-19.9 | |

| Cloaca | 111 (98.2) | 47.4 | 11.6-192.7 | |

| Anal stenosis | 28 (52.8) | 1.0 | 0.6-1.7 | |

| No fistula | 130 (80.2) | 3.5 | 2.3-5.2 | |

| Rare and other types | 108 (71.5) | 2.1 | 1.5-3.1 | |

|

Skeletal anomalies

Sex Male (%): 471 (52.3) Female (%)* : 430 (47.7) |

Perineal fistula | 259 (32.8) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 161 (53.5) | 2.4 | 1.8-3.1 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 222 (60.2) | 3.1 | 2.4-4.0 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 43 (81.1) | 8.8 | 4.4-17.8 | |

| Cloaca | 64 (67.4) | 4.2 | 2.7-6.7 | |

| Anal stenosis | 14 (37.8) | 1.3 | 0.6-2.5 | |

| No fistula | 55 (47.8) | 1.9 | 1.3-2.8 | |

| Rare and other types | 58 (53.7) | 2.4 | 1.6-3.6 | |

|

Spinal anomalies

Sex Male (%): 244 (52.8) Female (%)* : 218 (47.2) |

Perineal fistula | 91 (10.4) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 98 (27.8) | 3.3 | 2.4-4.6 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 130 (34.4) | 4.5 | 3.3-6.1 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 26 (51.0) | 8.9 | 5.0-16.1 | |

| Cloaca | 45 (47.4) | 7.7 | 4.9-12.2 | |

| Anal stenosis | 7 (18.4) | 1.9 | 0.8-4.5 | |

| No fistula | 14 (11.3) | 1.1 | 0.6-2.0 | |

| Rare and other types | 36 (30.5) | 3.8 | 2.4-5.9 | |

|

Cardiac anomalies

Sex Male (%): 432 (50.9) Female (%)* : 416 (49.1) |

Perineal fistula | 265 (29.1) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 188 (50.9) | 2.5 | 2.0-3.3 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 178 (45.1) | 2.0 | 1.6-2.6 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 23 (42.6) | 1.8 | 1.0-3.2 | |

| Cloaca | 33 (35.1) | 1.3 | 0.9-2.1 | |

| Anal stenosis | 10 (26.3) | 0.9 | 0.4-1.8 | |

| No fistula | 89 (59.7) | 3.6 | 2.5-5.2 | |

| Rare and other types | 35 (31.5) | 1.1 | 0.7-1.7 | |

|

Renal anomalies

Sex Male (%): 391 (57.5) Female (%)* : 289 (42.5) |

Perineal fistula | 186 (19.0) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 102 (27.2) | 1.6 | 1.2-2.1 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 174 (40.7) | 2.9 | 2.3-3.8 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 36 (63.2) | 7.3 | 4.2-12.8 | |

| Cloaca | 66 (61.7) | 6.9 | 4.5-10.5 | |

| Anal stenosis | 6 (13.6) | 0.7 | 0.3-1.6 | |

| No fistula | 40 (26.7) | 1.6 | 1.0-2.3 | |

| Rare and other types | 42 (33.1) | 2.1 | 1.4-3.2 | |

|

Bladder anomalies

Sex Male (%): 152 (58.7) Female (%)* : 107 (41.3) |

Perineal fistula | 40 (4.2) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 32 (9.0) | 2.3 | 1.4-3.7 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 67 (16.0) | 4.3 | 2.9-6.5 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 28 (50.9) | 23.6 | 12.8-43.8 | |

| Cloaca | 35 (34.4) | 11.9 | 7.1-20.0 | |

| Anal stenosis | 2 (5.0) | 1.2 | 0.3-5.2 | |

| No fistula | 12 (8.8) | 2.2 | 1.1-4.3 | |

| Rare and other types | 32 (25.4) | 7.8 | 4.7-12.9 | |

|

Genital anomalies

Sex Male (%): 323 (61.5) Female (%)* : 202 (38.5) |

Perineal fistula | 103 (10.4) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 45 (11.9) | 1.2 | 0.8-1.7 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 149 (32.9) | 4.3 | 3.2-5.6 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 32 (53.3) | 9.9 | 5.7-17.1 | |

| Cloaca | 80 (80.0) | 34.6 | 20.4-58.9 | |

| Anal stenosis | 6 (13.0) | 1.3 | 0.5-3.1 | |

| No fistula | 31 (20.0) | 2.2 | 1.4-3.4 | |

| Rare and other types | 59 (41.5) | 6.2 | 4.2-9.1 | |

|

Tracheoesophageal anomalies

Sex Male (%): 99 (56.9) Female (%)* : 75 (43.1) |

Perineal fistula | 29 (2.9) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 39 (10.2) | 3.7 | 2.3-6.1 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 67 (15.4) | 6.0 | 3.8-9.5 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 5 (8.3) | 3.0 | 1.1-8.1 | |

| Cloaca | 15 (13.5) | 5.2 | 2.7-10.0 | |

| Anal stenosis | 0 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | |

| No fistula | 8 (5.4) | 1.9 | 0.9-4.2 | |

| Rare and other types | 5 (3.6) | 1.3 | 0.5-3.3 | |

|

Brain anomalies

Sex Male (%): 98 (53.6) Female (%)* : 85 (46.4) |

Perineal fistula | 59 (9.8) | ref | ref |

| Vestibular fistula | 37 (13.9) | 1.5 | 1.0-2.3 | |

| Rectourethral fistula | 39 (13.0) | 1.4 | 0.9-2.1 | |

| Recto-bladder neck fistula | 5 (14.7) | 1.6 | 0.6-4.3 | |

| Cloaca | 8 (10.1) | 1.0 | 0.5-2.3 | |

| Anal stenosis | 3 (10.7) | 1.1 | 0.3-3.8 | |

| No fistula | 19 (18.4) | 2.1 | 1.2-3.7 | |

| Rare and other types | 9 (10.8) | 1.1 | 0.5-2.4 |

N/A, not applicable. *Of total known data, excluding not checked, unknown or missing data per variable.

Reconstructive surgery and stoma

Of all patients, 44.5% had a stoma. The majority of patients with no fistula, rectourethral fistula (bulbar, prostatic, or unspecified type), cloaca or recto-bladder neck fistula received a stoma (78.8%, 96.6%, 97.3% and 98.5%, respectively), while 9.5%, 12.0% and 34.0% of perineal fistula, anal stenosis or vestibular fistula patients, respectively, did. Of patients that underwent reconstruction, 45.0% received a stoma, and of those without a reconstruction or with unknown data, 29.9% did. Most were divided stomas (73.3%) and placed at the descending/sigmoid colon junction (80.3%). Stoma formation complication rate was 25.0%, including stenosis, wound infection or dehiscence, stomal prolapse or retraction. Stomas were closed in 83.7% of patients, with complications after closure in 12.3%, including wound infection, anastomotic leakage, adhesions or incisional hernia. Of the patients whose stoma was not closed (n = 183), 21 patients died, 10 had an end stoma, 8 were lost to follow-up, 3 were awaiting reconstruction, and 1 patient had closure delayed due to prioritization of other issues. The reasons for not closing the stoma could not be deduced from free-text entries for the remaining patients.

Of all 2619 patients, 2278 had undergone reconstructive surgery. Information on whether a reconstruction had been performed was unknown for 5.2% of all patients (due to secondary referrals or missing data), and the remaining 7.8% of patients did not undergo reconstructive surgery. Of the patients that did not undergo reconstruction, 30 (14.8%) patients had died before surgery. Of the remaining 173 patients, most had a perineal fistula (64.7%), followed by anal stenosis (8.7%) and ventrally displaced anus (5.2%). Only 16.8% of them had a stoma. Deduction of free text of these 173 patients showed that for 62 patients a reconstruction was not indicated, due to anal dilatation management only or a perineal fistula sufficiently surrounded by sphincter musculature24. Ten patients were awaiting surgery, four had a definitive colostomy, three were treated for other issues with priority and three patients refused surgery. For the remainder of patients (91; 52.6%), the reason to refrain from reconstruction remains elusive.

Of patients with available data (n = 2481), 91.8% underwent reconstructive surgery (Table 3). Perineal fistulas were mostly corrected by mini-posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) (40.3%), PSARP (33.5%), or anterior sagittal anorectoplasty (ASARP; 11.4%), and vestibular fistulas mostly through PSARP (71.9%) or ASARP (19.2%). Anal stenosis was mostly corrected by anoplasty (37.8%), PSARP (21.6%) or mini-PSARP (21.6%), and rectourethral fistulas (any type), no fistula and recto-bladder neck fistulas through PSARP (88.1%, 80.7%, and 63.5%, respectively). Cloacas were most often reconstructed by posterior sagittal anorectovagino(urethro)plasty (PSARV(U)P) (42.9%) or total urogenital mobilization (39.8%). Complications after reconstruction occurred in 25.5% of patients, including wound infections, dehiscence, stenosis, urethral injury and recurrent fistula. Late complications of frequent or severe perianal dermatitis or rectal mucosal prolapse occurred in 13.8% and 12.3%, respectively. Redo surgery was required in 4.4% of patients.

Table 3.

Surgical characteristics of the ARM patients in the ARM-Net registry

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 1314 (50.4) |

| Female | 1292 (49.6) |

| Stoma placement* | 1125 (44.5) |

| Type | |

| Divided | 825 (73.3) |

| Loop | 248 (22.0) |

| Unknown | 52 (4.6) |

| Bowel section | |

| Descending/sigmoid colon junction | 903 (80.3) |

| Transverse colon | 90 (8.0) |

| Ileum | 16 (1.4) |

| Sigmoid colon | 12 (1.1) |

| Ascending colon | 5 (0.4) |

| Descending colon | 4 (0.4) |

| Other | 16 (1.4) |

| Unknown | 79 (7.0) |

| Complications stoma placement* | 242 (25.0) |

| Stoma closed* | 942 (83.7) |

| Complications stoma closure* | 101 (12.3) |

| Reconstructive surgery performed* | 2278 (91.8) |

| Age at reconstructive surgery in months (median, IQR)* | 4 (2-7) |

| Type | |

| PSARP | 1247 (54.7) |

| Mini-PSARP | 435 (19.1) |

| ASARP | 197 (8.6) |

| Anoplasty | 114 (5.0) |

| Cutback | 49 (2.2) |

| LAARP | 73 (3.2) |

| PSARV(U)P | 60 (2.6) |

| TUM | 43 (1.9) |

| Other | 41 (1.8) |

| Unknown | 19 (0.8) |

| Complications reconstructive surgery* | 542 (25.5) |

| Late complications* | 379 (24.9) |

| Redo reconstructive surgery* | 93 (4.4) |

*Of total known data, excluding not checked, unknown or missing data per variable. PSARP, posterior sagittal anorectoplasty; ASARP, anterior sagittal anorectoplasty; LAARP, laparoscopic anterior anorectoplasty; PSARV(U)P, posterior sagittal anorectovagino(urethro)plasty; TUM, total urogenital mobilization.

Median age at time of reconstructive surgery was 4 months (i.q.r. 2–7). Patients with skeletal, spinal, cardiac, renal, bladder, genital or tracheoesophageal anomalies were older at time of surgery than patients without (4 (i.q.r. 2–7) versus 3 (i.q.r. 1–5) months, P < 0.001). When categorizing age into younger or older than 3 months, the patients with anomalies (43.5%) more often had undergone reconstruction later than 3 months of age than patients without anomalies (57.9%; P < 0.001). While skeletal, spinal, renal, bladder and genital anomalies separately were associated with older age at the time of surgery, cardiac anomalies were not. However, when excluding patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and patent foramen ovale (PFO; mentioned in free text) from cardiac anomalies, the same relation was found (P = 0.023).

Functional outcomes one year after anorectal reconstruction

Functional outcomes data at one-year follow-up were available in 60–70% varying per outcome measure (Table 4). Of these patients, 55.4% suffered from constipation. Treatment for constipation included stool softeners (54.8%), diet (32.4%), laxatives (23.9%) or enemas (23.4%). Faecal consistency was soft for most patients (67.8%), and median frequency was twice per 24 h (i.q.r. 1–2). Most patients (88.3%) underwent anal dilatations and 41.9% experienced pain during dilatations.

Table 4.

Functional outcomes in ARM patients one year after anorectal reconstruction

| Data available N (%) | N (%)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Constipation | 1795 (70.1) | 994 (55.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 876 (48.8) | |

| Female | 915 (51.0) | |

| Constipation treatments | ||

| Stool softener | 539 (54.8) | |

| Diet | 319 (32.4) | |

| Laxatives | 235 (23.9) | |

| Enemas | 230 (23.4) | |

| Consistency of feces | 1711 (66.9) | |

| Soft | 1160 (67.8) | |

| Solid | 483 (28.2) | |

| Liquid | 68 (4.0) | |

| Defecation frequency per 24 hours (median, IQR) | 1563 (61.1) | 2 (1-2) |

| Dilatations | 1743 (68.1) | 1539 (88.3) |

| Sex ratio | ||

| Male | 856 (49.2) | |

| Female | 883 (50.8) | |

| Pain during dilatations | 645 (41.9) |

*Of total known data, excluding not checked, unknown or missing data per variable.

Discussion

This study describes the clinical and surgical characteristics of patients in the ARM-Net over a 10-year period. In accordance with existing literature, most patients had a perineal fistula, followed by vestibular fistula in females and rectobulbar and rectoprostatic fistula in males5. The majority of patients underwent reconstructive surgery and subsequent anal dilatations. Just over half of the patients suffered from constipation one year after reconstructive surgery. Patients frequently had associated anomalies, which were mostly skeletal, cardiac or renal.

Skeletal (including vertebral), cardiac and renal anomalies were the three most common associated anomalies in the present report, in concordance with the existing literature5,9,10,38. Contrary to our findings, some studies9,10,38,39 found that genitourinary anomalies were the most frequent; however, this may be due to the inclusion of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) under genitourinary anomalies, where it is a separate entity in the present study. Remarkably in this cohort, only about a third were screened for VUR, of which subsequently a third was diagnosed with VUR, emphasizing the potential importance of systematic screening40. Incidences of skeletal and vertebral anomalies were within the ranges found in the literature5,9,10,38, although some studies included spinal cord anomalies, such as tethered cord, in this category. The incidence of tethered cord in our study (8.2%) is similar to one study10 but lower than others (15–60%)9,38,41,42. These discrepancies likely stem from a wide variation among centres in defining and diagnosing tethered cord25. Although cardiac anomalies are among the three most common anomalies associated with ARM, the frequency in our study (39%) is higher compared to the 10–25% in the literature9,10,38. However, when excluding haemodynamically insignificant conditions, such as PDA, PFO or spontaneously closed ventricular septal defects, incidence decreases to 28.9%, close to the aforementioned upper limit.

Different ARM types were significantly associated with accompanying anomalies. Vestibular fistulas, rectourethral fistulas, recto-bladder neck fistulas, cloacas, no fistulas, and the group of rare and other types were more likely associated with other anomalies than perineal fistulas. Patients with cloaca were most likely to have associated anomalies, but it should be noted that confidence intervals were wide due to the low prevalence of this ARM type. These results show that for patients with common as well as rarer ARM types, thorough diagnostic screening for associated anomalies is warranted. This study showed that associated anomalies may influence timing of reconstructive surgery, as patients with associated anomalies are older at reconstruction than patients without. This probably relates to prioritization of treatment for associated anomalies.

The majority of patients underwent reconstructive surgery, where those patients that did not had either died, had an ARM type without indication for reconstruction, or were managed through dilatations only. Most reconstructed patients underwent a PSARP, which should be considered the standard operative approach6,12,43. To prevent strictures, a common postoperative complication, most patients underwent subsequent anal dilatations, as described by Peña12. Although most centres have adopted the dilatation protocol in their postoperative regimens, several studies have found that dilatations do not lower stricture rates44,45. With over 40% of the patients in this study experiencing pain, protocolized anal dilatations in postoperative management should be reconsidered.

More than half of the patients experienced constipation one year after reconstruction, in accordance with the previous literature13,46,47. Unfortunately, constipation continues to affect ARM patients beyond childhood into adulthood and may compromise quality of life17,47.

This study has several limitations. Data quality, including completeness and comparability, poses challenges in registry data, and should be evaluated before analysing data48,49. A recent quality assessment of the ARM-Net registry found error-prone, yet with appropriate cleaning, valuable data50. Although substantial data cleaning was required, most results in this study stem from closed-ended items, minimizing missing data and interpretation variations. The 60-day window of variability in patient’s age at time of reconstruction, due to the manner that dates of birth and surgery are calculated, is another limitation. Therefore, only median age was reported, which should even out this variability. The data found that several patients did not have their stoma closed or did not undergo reconstruction, which may be explained by incomplete registration by surgeons. Therefore, one of the recommendations for an improved ARM-Net registry is to implement automatic reminders to complete or update data entry50. Another limitation is that the current registry only collects stoma closure dates, omitting placement date or indication. Although some ARM phenotypes may require a temporary diverting stoma, management of postoperative complications might also be a stoma indication. The lack of uniform and validated scoring systems for outcome assessment at 1-year follow-up introduces heterogeneity between the participating centres and highlights the importance of standardization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Members of the ARM-Net Consortium:

Eva Amerstorfer and Holger Till, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria; Piero Bagolan, Ospedale Bambino Gesù, Rome, Italy; Stefan Deluggi, Kepler University Hospital GmbH, Linz, Austria; Emre Divarci, Ege University Medical School, İzmir, Turkey; María Fanjul, Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain; Araceli García Vázquez, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; Carlos Giné, Vall d’Hebron Hospital Campus, Barcelona, Spain; Jan Gosemann and Martin Lacher, University Hospital Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany; Caterina Grano, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy; Sabine Grasshoff-Derr, Buergerhospital and Clementine Childrens Hospital, Frankfurt, Germany; Stefano Giuliani, Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, United Kingdom; Stefan Holland-Cunz, University Children’s Hospital, Basel, Switzerland; Wilfried Krois, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria; Ernesto Leva, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Italy; Judith Lindert, Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Rostock, Germany; Gabriele Lisi, Santo Spirito Civil Hospital, Pescara, Italy; Johanna Ludwiczek, Medical Faculty, Johannes Kepler University Linz and Kepler University Hospital GmbH, Linz, Austria; Igor Makedonsky, Children’s Hospital Dnepropetrovsk, Dnipro, Ukraine; Carlo Marcelis and Chris Verhaak, Amalia Children’s Hospital, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Marc Miserez, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, KULeuven, Leuven, Belgium; Mazeena Mohideen, SoMA Austria, patient organization, Austria; Alessio Pini Prato, AO SS Antonio e Biagio e Cesare Arrigo, Alessandria, Italy; Lucie Poš and Richard Škába, Charles University and University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic; Carlos Reck-Burneo, Landesklinikum Mödling, Mödling, Austria; Heiko Reutter, Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany; Stephan Rohleder, Medical University Hospital, Mainz, Germany; Inbal Samuk, Schneider Children’s Medical Center, Petah Tikva, affiliated with Sackler School of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel; Nagoud Schukfeh, Medical School Hannover, Hannover, Germany; Pernilla Stenström, Skane University Hospital Lund, Lund, Sweden; Alejandra Vilanova-Sánchez, University Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain; Patrick Volk, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; Marieke Witvliet, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Contributor Information

Isabel C Hageman, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Radboudumc Amalia Children’s Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; Surgical Research, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Paola Midrio, Pediatric Surgery Unit, Cà Foncello Hospital, Treviso, Italy.

Hendrik J J van der Steeg, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Radboudumc Amalia Children’s Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Ekkehart Jenetzky, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Medical Center of Johannes Gutenberg-University, Mainz, Germany; Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Witten/Herdecke University, Witten, Germany.

Barbara D Iacobelli, Medical and Surgical Department of the Fetus-Newborn-Infant, Ospedale Bambin Gesù, Rome, Italy.

Anna Morandi, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy.

Cornelius E J Sloots, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus Medical Center–Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Eberhard Schmiedeke, Department of Pediatric Surgery and Urology, Centre for Child and Youth Health, Klinikum Bremen-Mitte, Bremen, Germany.

Paul M A Broens, Department of Surgery, Division of Pediatric Surgery, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Francesco Fascetti Leon, Pediatric Surgery Unit, University Hospital, Padua, Italy.

Yusuf H Çavuşoğlu, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Gazi University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

Ramon R Gorter, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Emma Children’s Hospital Amsterdam UMC, Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Gastroenterology and Metabolism Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Misel Trajanovska, Surgical Research, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia.

Sebastian K King, Surgical Research, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Department of Paediatrics, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia; Department of Paediatric Surgery, The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Dalia Aminoff, AIMAR—Associazione Italiana Malformazioni AnoRettali, Rome, Italy.

Nicole Schwarzer, SOMA—Selfhelp Organization for People with Anorectal Malformations e.V., Munich, Germany.

Michel Haanen, VA-Dutch Patient Organization for Anorectal Malformations, Huizen, The Netherlands.

Ivo de Blaauw, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Radboudumc Amalia Children’s Hospital, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Iris A L M van Rooij, Department for Health Evidence, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

ARM-Net Consortium:

Eva Amerstorfer, Holger Till, Piero Bagolan, Stefan Deluggi, Emre Divarci, María Fanjul, Araceli García Vázquez, Carlos Giné, Jan Gosemann, Martin Lacher, Caterina Grano, Sabine Grasshoff-Derr, Stefano Giuliani, Stefan Holland-Cunz, Wilfried Krois, Ernesto Leva, Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Judith Lindert, Gabriele Lisi, Johanna Ludwiczek, Igor Makedonsky, Carlo Marcelis, Chris Verhaak, Marc Miserez, Mazeena Mohideen, Alessio Pini Prato, Lucie Poš, Richard Škába, Carlos Reck-Burneo, Heiko Reutter, Stephan Rohleder, Inbal Samuk, Nagoud Schukfeh, Pernilla Stenström, Alejandra Vilanova-Sánchez, Patrick Volk, and Marieke Witvliet

Funding

Dr Isabel Hageman is supported by the Academy Ter Meulen grant of the Academy Medical Sciences Fund of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts & Sciences (KNAW). Professor King is supported in his role as an Academic Paediatric Surgeon by the Royal Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Australian Government.

Author contributions

Isabel Hageman (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Paola Midrio (Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Hendrik van der Steeg (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Ekkehart Jenetzky (Conceptualization, Data curation, Software, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Barbara Iacobelli (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Anna Morandi (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Cornelius Sloots (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Eberhard Schmiedeke (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Paul Broens (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Francesco Fascetti-Leon (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Yusuf Çavuşoğlu (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Ramon Gorter (Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Misel Trajanovska (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing), Sebastian King (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing), Dalia Aminoff (Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Nicole Schwarzer (Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Michel Haanen (Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Ivo de Blaauw (Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing), Iris van Rooij (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), and ARM-Net Consortium (Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—review & editing)

Disclosure

None.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS online.

Data availability

The data generated, used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Orphanet Report Series . Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: bibliographic data. Rare Dis Collect 2022. http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Prevalence_of_rare_diseases_by_diseases.pdf (accessed 2023).

- 2. Cuschieri A. Descriptive epidemiology of isolated anal anomalies: a survey of 4.6 million births in Europe. Am J Med Genet 2001;103:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jenetzky E. Prevalence estimation of anorectal malformations using German diagnosis related groups system. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;23:1161–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kancherla V, Sundar M, Tandaki L, Lux A, Bakker MK, Bergman JEet al. Prevalence and mortality among children with anorectal malformation: a multi-country analysis. Birth Defects Res 2023;115:390–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Levitt MA, Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2007;2:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peña A. Surgical management of anorectal malformations: a unified concept. Pediatr Surg Int 1988;3:82–93 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwai N, Fumino S. Surgical treatment of anorectal malformations. Surg Today 2013;43:955–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. King SK, Krois W, Lacher M, Saadai P, Armon Y, Midrio P. Optimal management of the newborn with an anorectal malformation and evaluation of their continence potential. Semin Pediatr Surg 2020;29:150996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nah SA, Ong CC, Lakshmi NK, Yap TL, Jacobsen AS, Low Y. Anomalies associated with anorectal malformations according to the Krickenbeck anatomic classification. J Pediatr Surg 2012;47:2273–2278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ratan SK, Rattan KN, Pandey RM, Mittal A, Magu S, Sodhi PK. Associated congenital anomalies in patients with anorectal malformations—a need for developing a uniform practical approach. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1706–1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van de Putte R, van Rooij IALM, Marcelis CLM, Guo M, Brunner HG, Addor M-Cet al. Spectrum of congenital anomalies among VACTERL cases: a EUROCAT population-based study. Pediatr Res 2020;87:541–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peña A, Devries PA. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty: important technical considerations and new applications. J Pediatr Surg 1982;17:796–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levitt MA, Kant A, Peña A. The morbidity of constipation in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:1228–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Danielson J, Karlbom U, Graf W, Wester T. Persistent fecal incontinence into adulthood after repair of anorectal malformations. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Danielson J, Karlbom U, Graf W, Wester T. Outcome in adults with anorectal malformations in relation to modern classification—which patients do we need to follow beyond childhood? J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:463–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hassink EA, Rieu PN, Severijnen RS, vd Staak FH, Festen C. Are adults content or continent after repair for high anal atresia? A long-term follow-up study in patients 18 years of age and older. Ann Surg 1993;218:196–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP. Outcome of anorectal malformations and Hirschsprung’s disease beyond childhood. Semin Pediatr Surg 2010;19:160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kyrklund K, Pakarinen MP, Koivusalo A, Rintala RJ. Long-term bowel functional outcomes in rectourethral fistula treated with PSARP: controlled results after 4–29 years of follow-up: a single-institution, cross-sectional study. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:1635–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wigander H, Nisell M, Frenckner B, Wester T, Brodin U, Öjmyr-Joelsson M. Quality of life and functional outcome in Swedish children with low anorectal malformations: a follow-up study. Pediatr Surg Int 2019;35:583–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stenström P, Kockum CC, Benér DK, Ivarsson C, Arnbjörnsson E. Adolescents with anorectal malformation: physical outcome, sexual health and quality of life. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2014;26:49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morandi A, Ure B, Leva E, Lacher M. Survey on the management of anorectal malformations (ARM) in European pediatric surgical centers of excellence. Pediatr Surg Int 2015;31:543–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Blaauw I, Wijers CH, Schmiedeke E, Holland-Cunz S, Gamba P, Marcelis CLet al. First results of a European multi-center registry of patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2013;48:2530–2535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amerstorfer EE, Grano C, Verhaak C, García-Vasquez A, Miserez M, Radleff-Schlimme Aet al. What do pediatric surgeons think about sexual issues in dealing with patients with anorectal malformations? The ARM-Net Consortium members’ opinion. Pediatr Surg Int 2019;35:935–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amerstorfer EE, Schmiedeke E, Samuk I, Sloots CEJ, van Rooij I, Jenetzky Eet al. Clinical differentiation between a normal anus, anterior anus, congenital anal stenosis, and perineal fistula: definitions and consequences—the ARM-Net Consortium Consensus. Children (Basel) 2022;9:831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fanjul M, Samuk I, Bagolan P, Leva E, Sloots C, Giné Cet al. Tethered cord in patients affected by anorectal malformations: a survey from the ARM-Net Consortium. Pediatr Surg Int 2017;33:849–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Giuliani S, Grano C, Aminoff D, Schwarzer N, Van De Vorle M, Cretolle Cet al. Transition of care in patients with anorectal malformations: consensus by the ARM-Net Consortium. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:1866–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jenetzky E, van Rooij IALM, Aminoff D, Schwarzer N, Reutter H, Schmiedeke Eet al. The challenges of the European Anorectal Malformations-Net registry. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2015;25:481–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Midrio P, van Rooij I, Brisighelli G, Garcia A, Fanjul M, Broens Pet al. Inter- and intraobserver variation in the assessment of preoperative colostograms in male anorectal malformations: an ARM-Net Consortium survey. Front Pediatr 2020;8:571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morandi A, Fanjul M, Iacobelli BD, Samuk I, Aminoff D, Midrio Pet al. Urological impact of epididymo-orchitis in patients with anorectal malformation: an ARM-Net Consortium study. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2022;32:504–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samuk I, Amerstorfer EE, Fanjul M, Iacobelli BD, Lisi G, Midrio Pet al. Perineal groove: an anorectal malformation network, consortium study. J Pediatr 2020;222:207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Samuk I, Gine C, de Blaauw I, Morandi A, Stenstrom P, Giuliani Set al. Anorectal malformations and perineal hemangiomas: the ARM-Net Consortium experience. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:1993–1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schmiedeke E, de Blaauw I, Lacher M, Grasshoff-Derr S, Garcia-Vazquez A, Giuliani Set al. Towards the perfect ARM center: the European Union’s criteria for centers of expertise and their implementation in the member states. A report from the ARM-Net. Pediatr Surg Int 2015;31:741–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van der Steeg HJ, Schmiedeke E, Bagolan P, Broens P, Demirogullari B, Garcia-Vazquez Aet al. European consensus meeting of ARM-Net members concerning diagnosis and early management of newborns with anorectal malformations. Tech Coloproctol 2015;19:181–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. van der Steeg HJJ, van Rooij I, Iacobelli BD, Sloots CEJ, Leva E, Broens Pet al. The impact of perioperative care on complications and short term outcome in ARM type rectovestibular fistula: an ARM-Net Consortium study. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:1595–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van der Steeg HJJ, van Rooij I, Iacobelli BD, Sloots CEJ, Morandi A, Broens PMAet al. Bowel function and associated risk factors at preschool and early childhood age in children with anorectal malformation type rectovestibular fistula: an ARM-Net Consortium study. J Pediatr Surg 2022;57:89–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wijers CH, de Blaauw I, Marcelis CL, Wijnen RM, Brunner H, Midrio Pet al. Research perspectives in the etiology of congenital anorectal malformations using data of the International Consortium on Anorectal Malformations: evidence for risk factors across different populations. Pediatr Surg Int 2010;26:1093–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holschneider A, Hutson J, Peña A, Beket E, Chatterjee S, Coran Aet al. Preliminary report on the international conference for the development of standards for the treatment of anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2005;40:1521–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oh C, Youn JK, Han JW, Yang HB, Kim HY, Jung SE. Analysis of associated anomalies in anorectal malformation: major and minor anomalies. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35:e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, Roth MP. Associated malformations in patients with anorectal anomalies. Eur J Med Genet 2007;50:281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kruger P, Teague WJ, Khanal R, Hutson JM, King SK. Screening for associated anomalies in anorectal malformations: the need for a standardized approach. ANZ J Surg 2019;89:1250–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levitt MA, Patel M, Rodriguez G, Gaylin DS, Pena A. The tethered spinal cord in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Totonelli G, Morini F, Catania VD, Schingo PM, Mosiello G, Palma Pet al. Anorectal malformations associated spinal cord anomalies. Pediatr Surg Int 2016;32:729–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tirrell TF, McNamara ER, Dickie BH. Reoperative surgery in anorectal malformation patients. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jenetzky E, Reckin S, Schmiedeke E, Schmidt D, Schwarzer N, Grasshoff-Derr Set al. Practice of dilatation after surgical correction in anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int 2012;28:1095–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mullassery D, Chhabra S, Babu AM, Iacona R, Blackburn S, Cross KMet al. Role of routine dilatations after anorectal reconstruction-comparison of two tertiary centers. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2019;29:243–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Levitt MA, Peña A. Outcomes from the correction of anorectal malformations. Curr Opin Pediatr 2005;17:394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rintala RJ, Lindahl HG, Rasanen M. Do children with repaired low anorectal malformations have normal bowel function? J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kodra Y, Posada de la Paz M, Coi A, Santoro M, Bianchi F, Ahmed Fet al. Data quality in rare diseases registries. Adv Exp Med Biol 2017;1031:149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hageman IC, van Rooij I, de Blaauw I, Trajanovska M, King SK. A systematic overview of rare disease patient registries: challenges in design, quality management, and maintenance. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023;18:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hageman IC, van der Steeg HJJ, Jenetzky E, Trajanovska M, King SK, de Blaauw Iet al. A quality assessment of the ARM-Net registry design and data collection. J Pediatr Surg 2023;58:1921–1928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data generated, used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.