Abstract

Large-scale production and waste of plastic materials have resulted in widespread environmental contamination by the breakdown product of bulk plastic materials to micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs). The small size of these particles enables their suspension in the air, making pulmonary exposure inevitable. Previous work has demonstrated that xenobiotic pulmonary exposure to nanoparticles during gestation leads to maternal vascular impairments, as well as cardiovascular dysfunction within the fetus. Few studies have assessed the toxicological consequences of maternal nanoplastic (NP) exposure; therefore, the objective of this study was to assess maternal and fetal health after a single maternal pulmonary exposure to polystyrene NP in late gestation. We hypothesized that this acute exposure would impair maternal and fetal cardiovascular function. Pregnant rats were exposed to nanopolystyrene on gestational day 19 via intratracheal instillation. 24 h later, maternal and fetal health outcomes were evaluated. Cardiovascular function was assessed in dams using vascular myography ex vivo and in fetuses in vivo function was measured via ultrasound. Both fetal and placental weight were reduced after maternal exposure to nanopolystyrene. Increased heart weight and vascular dysfunction in the aorta were evident in exposed dams. Maternal exposure led to vascular dysfunction in the radial artery of the uterus, a resistance vessel that controls blood flow to the fetoplacental compartment. Function of the fetal heart, fetal aorta, and umbilical artery after gestational exposure was dysregulated. Taken together, these data suggest that exposure to NPs negatively impacts maternal and fetal health, highlighting the concern of MNPs exposure on pregnancy and fetal development.

Keywords: fetal growth restriction, intratracheal instillation, cardiac ultrasound, micro- and nanoplastics, DOHaD

Societal dependence on synthetic polymers has resulted in an ever-growing environmental burden of plastics. Plastics break down from their bulk material into smaller pieces to form particles in the micro- (<5 mm and >100 nm) and nano- (<100 nm) size range through mechanical, photochemical, or thermal degradation processes. Recent advancements in detection methods have allowed for the identification of airborne plastic particles in rural (Allen et al., 2019; Evangeliou et al., 2020), urban (Dris et al., 2015; Klein and Fischer, 2019; Liu et al., 2019), and indoor air (Perera et al., 2023; Yao et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, inhalation has been identified as major route of plastic particulate exposure (Zuri et al., 2023) and airborne plastic particles must be considered as a component of particulate matter.

Several studies have demonstrated the extensive mobility of micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) in the outdoor (Allen et al., 2019; Brahney et al., 2020; Dong et al., 2021), domestic (Dessì et al., 2021; He et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022; Shruti et al., 2022; Vega-Herrera et al., 2022; Yao et al., 2022) and biological environments (Cary et al., 2023a; Choi et al., 2021; da Silva Brito et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2021, 2022; Fournier et al., 2020; Gonçalves et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022; Sun et al., 2022). Furthermore, MNPs have been identified in human lung (Amato-Lourenço et al., 2021; Jenner et al., 2022), placental tissue (Ragusa et al., 2021), and human breastmilk samples (Ragusa et al., 2022) which demonstrates that humans experience real-world pulmonary exposure to and migration of these materials during pregnancy. Despite these findings, there have been few studies examining the toxicity of MNPs in living systems when compared to investigation other environmental contaminants. MNPs are a polymeric particulate with physicochemical and toxicological properties which differ from other well-studied micro- and nanoparticles (ie, metallic and carbonaceous particles) or components of environmental particulate matter (ie, wood smoke and diesel exhaust). Physicochemical properties (eg, size, shape, zeta-potential, core material, solubility, protein corona formation, etc.) determine particulate toxicity and interaction with biological systems (Bendtsen et al., 2020; Déciga-Alcaraz et al., 2020; Nurkiewicz et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, it cannot be assumed that MNP exposure will generate toxicological outcomes in the same way as other particulates, given their repeating carbon-based chains, oxygen atoms, hydrogen atoms, and plasticizing chemical additives to improve functional capacity. Because this emerging environmental contaminant is increasingly being detected in air, food, and water it is imperative that the biological consequences of exposure are elucidated.

Particulates are known to cause adverse cardiovascular outcomes and the ultrafine nano-size fraction is known to generate more cardiovascular toxicity than larger particles (Araujo et al., 2008; Du et al., 2013; Franck et al., 2011). Therefore, the nano-size fraction of MNPs generates more cause for concern than plastic particles of the micro-size range. Previously, it has been demonstrated that pulmonary nanoparticle exposure influences vascular function (Holland et al., 2016; Nurkiewicz et al., 2008) but whether these findings are consistent with nanoplastics (NPs) remains unknown. Vascular dysfunction is especially deleterious during physiological stresses, such as pregnancy, when blunted vascular reactivity limits nutrient delivery and impairs fetal growth. During a healthy pregnancy, the uterine vasculature is characterized by increased vasodilation, thereby allowing a higher volume of maternal arterial blood to be delivered to the uterus (Fournier et al., 2021a). Therefore, agents impairing uterine vascular responsivity often produce negative fetal outcomes including fetal growth restriction (FGR) or decreased fetal weight. This phenomenon has been observed after maternal exposure to metallic and carbonaceous nanoparticles but has not been investigated after exposure to NPs (Gandley et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2013, 2018).

FGR is associated with the decreased access to nutrients in utero and the development of cardiovascular diseases (Barker, 1995). A hostile environment in utero induces fetal cardiovascular adaptations that ultimately may generate cardiometabolic pathologies as an adult (Amruta et al., 2022; Barker et al., 1993). These pathologies may be detectable as early as the fetal stage (Pérez-Cruz et al., 2015; Stapleton et al., 2013). Accordingly, maternal nanoparticle exposures have been shown to modulate cardiovascular function in offspring (Bowdridge et al., 2022; Fournier et al., 2019, 2021b; Hathaway et al., 2017; Stapleton et al., 2013, 2018; Wu et al., 2020). Our research group has demonstrated that maternal pulmonary exposure to polystyrene NP in rats results in fetal growth restriction and an increase risk of fetal loss in the form of fetal resorption (Fournier et al., 2020); however, it is unknown if maternal NP exposure during gestation may also influence cardiovascular function.

The objective of this study was to assess maternal and fetal polystyrene NP cardiovascular toxicity in pregnant rats after deposition into the maternal lung. Polystyrene was used as a representative plastic material due to its common use in MNP research and commercial availability. Herein, we investigated maternal health, vascular function, and fetal cardiovascular physiology 24 h after a single exposure to NPs.

Materials and methods

Animals

Time-pregnant rats were ordered (n = 47) from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY) and delivered to a Rutgers University AAALAC accredited vivarium. Food and water were available to the rats ad libitum and rats were given a minimum of 24 hours to acclimate. Animals were randomly divided into control and exposed groups. All experiments were humanely conducted with Rutgers University IACUC approval.

Particle characterization

Commercially available 20 nm rhodamine-labeled polystyrene beads (8.8 × 1014 particles/mL; 10 mg/mL; PS20-RB-2; NanoCS, New York, NY) suspended in a 1% biocompatible aqueous stock solution were utilized. Material characterization and dosimetry has been previously described (Fournier et al., 2020). In brief, zeta potential and dynamic light scattering measurements verified the vendor’s characteristics that the nanopolystyrene beads had ζ-potential of − 0.09 mV ± 0.20 with an average particle size of 21.9 nm ± 0.03.

Intratracheal instillation of pregnant rats

Polystyrene beads were vortexed for 1 minute and then sonicated on ice for 5 minutes at an amplitude of 30% (Q500 Sonicator; QSonica, Newtown, CT). On GD19, pregnant Sprague Dawley rats were briefly anesthetized using 5% isoflurane and 300 µL (approximately 2.6 × 1014 particles) of nanopolystyrene bead suspension or 300 µL of saline solution were deposited into the lungs via intratracheal instillation. Rationale for the selected number of particles and route of delivery has previously been described (Fournier et al., 2020). Rats were returned to their cages after regaining consciousness and were monitored for normal behavior after exposure.

Exposure dosimetry

As most environmental detection methods do not possess the sensitivity to detect particles in the nano-size range, we considered a 1 mm3 atmospheric microparticle and mathematically converted to be representative of the spherical 20 nm polystyrene beads used in this study (Fournier et al., 2020). Consequently, a single microparticle amounts to 2.39 × 1014 nanopolystyrene beads. We then used reported estimates of human microplastic inhalation to determine an estimated nanoparticle number. It has been reported that 132 microplastic particles are inhaled by the average woman daily (Cox et al., 2019). In pregnancy, the volume of gas inhaled with each breath increases by up to 48% while the respiration rate remains constant (LoMauro and Aliverti, 2015). Therefore, we considered the daily total exposure is closer to the estimated upper bound, 279 microplastic particles (Cox et al., 2019). When converting to NPs, we considered an average microplastic particle of 1 mm3 could be reduced to 2.39 × 1014 of our NP beads. Combined with the upper bound of estimated microplastic particle exposures, data suggest that the average pregnant woman could be exposed to 6.67 × 1016 NP particles daily. Next, we accounted for differences of the surface area between human (62.7 m2) and rat (0.409 m2) lung (Ji and Yu, 2012) and calculated an appropriate experimental exposure for the pregnant rat lung as 4.34 × 1014 nanoplastic particles. This extrapolated value of a real-world estimate is 40% greater than the exposure dose used in this study (2.64 × 1014 NP particles), thus highlighting the biological relevance of this dose.

Mean arterial pressure

Twenty-four hours after intratracheal instillation, rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction; 3% maintenance) and the mean arterial pressure was measured through cannulation of the carotid artery as previously described (Fournier et al., 2019).

Tissue harvest

The maternal heart was removed, rinsed, trimmed, and weighed by the same individual to reduce intra-operator. Length on maternal tibia was recorded. Uterine horns were removed and rinsed in a 4°C physiological salt solution (PSS: 119 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.17 mM MgSO4 7H2O, 1.6 mM CaCl2 2H2O, 1.18 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, and 0.03 mM EGTA). As each uterine horn was dissected, the placentas were carefully removed. Fetuses were removed from their amniotic sacs and trimmed of the umbilical cords. Each fetus and its corresponding placenta were individually weighed, and anatomical location was recorded.

Macrovascular wire myography

Vasoreactivity of the maternal aorta and right uterine artery was assessed with wire myography. The aortic (1.5–2.5 mm; Knipp et al., 2003) or uterine artery (∼350 µm; Vodstrcil et al., 2012) vascular rings were mounted stainless steel wires connected to force transducers in an isolated vessel chamber (DMT, Ann Arbor, MI). Vessels were continuously supplied with 37°C wire myography physiological salt solution (WM-PSS: 130 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.18 mM KH2PO4, 1.17 mM MgSO4 7H2O, 14.9 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.03 mM EGTA, and 1.6 mM CaCl2) and aerated with 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide. Vascular response curves were established by incubation of vessels with increasing concentrations (10−9–10−4 M) of methacholine, sodium nitroprusside, and phenylephrine. Agonists were randomly applied in a dose-dependent manner between vessels to prevent an ordering effect of constrictors and dilating compounds. The artery segments were incubated with each agonist concentration for at least 2 min to achieve stable tension at the given concentration. Vessel ring reactivity was normalized to the vessels maximum tension induced by high-potassium physiological salt solution (KPSS: 74.7 mM NaCl, 60 mM KCl, 1.18 mM KH2PO4, 1.17 mM MgSO4 7H2O, 1.6 mM CaCl2, 14.9 mM NaHCO3, 0.03 mM EDTA, and 5.5 mM glucose).

Microvascular pressure myography

Vasoreactivity of the radial artery (a resistance vessel ∼150–250 µm; Bibeau et al., 2016; Senadheera et al., 2013) was assessed using pressure myography. The radial artery of the left uterine horn was isolated and mounted on 2 glass cannulas in a vessel chamber (Living Systems Instrumentation, Burlington, VT) containing 37°C microvessel physiological salt solution (MV-PSS: 119 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.17 mM MgSO4 7H2O, 1.6 mM CaCl2 2H2O, 1.18 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, and 0.03 mM EGTA) as previously described (Stapleton et al., 2013). The circulating PSS filling the chamber was supplied 5% CO2/21% O2. The radial artery was allowed 30 min to equilibrate and gain spontaneous tone in a circulating MV-PSS bath at a pressure constant of 60 mmHg maintained by a pressure servo-control system. Radial artery segments were incubated with increasing concentrations of methacholine, sodium nitroprusside, and phenylepherine from 10−9 to 10−4 M. Agonist order was randomly applied to prevent an ordering effect between constriction and dilation agonists. After concentration-response curves were completed, maximum vessel dilation was stimulated using Ca2+-free physiological salt solution (Ca2+ Free PSS: 120.6 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.17 mM MgSO4 7H2O, 1.18 mM NaH2PO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, and 0.03 mM EGTA) as previously described (Cary et al., 2023b). Reactivity of the vessel to each agonist was normalized to the maximum dilation induced by Ca2+-free PSS.

Maternal cardiovascular assessment

In a subset of animals (n = 12), in vivo Doppler ultrasonography of the maternal vasculature was carried out using the Vevo 2100 Imaging System (MS250 13–24 MHz transducer, VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada). Twenty-four hours after pulmonary exposure, rats were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and placed on a heated animal handling platform in the supine position and a nose cone was positioned over the nose and mouth of the rat to maintain anesthesia at 2.5% isoflurane. An electrolyte conducting gel was applied to the electrode pads and the paws of the rats were secured to the pads using surgical tape. Hair was removed from the chest and abdominal region of the rats using a depilatory cream and ultrasound transmission gel was applied. Color Doppler was used to identify the ascending aortic artery and the pulmonary artery. Subsequently, Pulsed Wave Doppler mode was used to calculate blood flow velocity and M mode was used to obtain vessel diameters.

Fetoplacental ultrasound

After assessment of maternal cardiovascular function, fetoplacental vasculature in the uteri was identified with color Doppler and fetal cardiovascular parameters were examined. The measured parameters represent the average of 3 fetuses for each dam. Pulsed Wave Doppler mode was used to calculate blood flow velocity and blood pressure gradient and stroke distance in the left ventricular outflow tract, fetal aorta, and umbilical artery. Stroke distance was represented by obtaining the velocity time integral (VTI) during systole. The VTI is the distance that the column of blood travels through an area in a given amount of time and is directly related to blood flow velocity. Other measurements such as fetal heart rate and vessel diameters were obtained using M mode or Pulsed Wave Doppler.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error with the dam as the sample size unit. Outliers were identified as above or below 2 standard deviations from the mean and removed from the presented data set. Mean arterial pressure, fetal and placental weights, and ultrasound data were analyzed by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups. Wire myography and pressure myography data were analyzed by nonlinear regression analysis. Outliers were defined as greater than 2 standard deviations from the mean and were removed from the data set (Supplementary Table 1). Statistical analyses were completed with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (San Diego, CA). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and statistical significance is defined at a p < .05 and is indicated with an asterisk (*).

Results

Maternal characteristics

Maternal weight, percent change in weight 24 h after intratracheal instillation, and mean arterial pressure were not significantly different between control and exposed groups. Pulmonary exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles resulted in a significant 11% increase in gross maternal heart weight as compared to control dams. This significant increase in maternal heart weight was maintained when controlling for tibial length, a stable marker of animal growth that is independent of litter size (Table 1). These results suggest that the nanopolystyrene exposure did not present overt toxicity to dams 24 h postexposure, although maternal heart weight increased.

Table 1.

Maternal weight, change in weight after intratracheal instillation, mean arterial pressure, gross heart weight, and heart weight with respect to tibia length

| Maternal weight (g) | Change in maternal weight post-IT (%) | Maternal mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | Maternal heart weight (g) | Maternal heart weight/tibia length (g/mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 337 ± 7.68 (n = 35) | 2.92 ± 0.32 (n = 30) | 69.7 ± 1.9 (n = 12) | 0.878 ± 0.025 (n = 36) | 0.016 ± 0.000207 (n = 12) |

| Nanopolystyrene | 338 ± 10.10 (n = 19) | 2.90 ± 0.48 (n = 12) | 72.8 ± 3.5 (n = 8) | 0.971 ± 0.039* (n = 18) | 0.0177 ± 0.00101* (n = 5) |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 5–36.

Significantly different (p < .05) from control dams as determined by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups.

Litter characteristics

Maternal exposure to polystyrene nanoparticles caused a significant reduction in fetal weight (−16%) and placental weight (−6.7%) when compared to saline controls. No significant changes were observed in placental efficiency, litter size, and resorptions (Table 2). These data demonstrate that nanopolystyrene may adversely affect fetoplacental growth.

Table 2.

Fetal weight, placental weight, placental efficiency, litter size, and resorptions

| Fetal weight | Placental weight | Placental efficiency | Litter size | Resorptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.31 ± 0.13 (n = 36) | 0.491 ± 0.009 (n = 35) | 6.52 ± 0.23 (n = 34) | 11.6 ± 0.41 (n = 35) | 0.886 ± 0.17 (n = 35) |

| Nanopolystyrene | 2.79 ± 0.12* (n = 20) | 0.458 ± 0.011* (n = 21) | 6.21 ± 0.29 (n = 21) | 12.1 ± 0.45 (n = 21) | 0.762 ± 0.18 (n = 21) |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 20–36.

Significantly different (p < .05) from control dams as determined by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups.

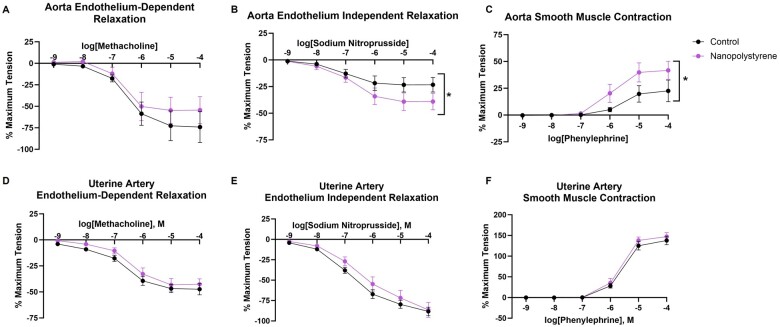

Maternal aorta and uterine artery reactivity

Aortic and uterine artery rings were challenged to investigate vascular reactivity of the macrocirculation (conduit vessels >150 μm) after NP exposure. Aortic rings of exposed dams demonstrated no significant difference in endothelium-dependent relaxation (Figure 1A) despite exhibiting an elevated smooth muscle relaxation in response to sodium nitroprusside (+70% compared to control at 10−4 M sodium nitroprusside, Figure 1B). Taken together, these data imply that exposed aortic rings do not produce comparable levels of nitric oxide and thus display endothelial dysfunction in response to methacholine. Furthermore, exposed aortic rings displayed heightened smooth muscle contraction in response to phenylephrine (+85% compared to control at 10−4 M phenylephrine, Figure 1C). Interestingly, uterine artery segments revealed no significant differences in reactivity after stimulation with methacholine, sodium nitroprusside, or phenylephrine (Figs. 1D–F). These data identify that a single exposure to polystyrene NPs excessively elevates aortic vascular smooth muscle responsivity and impairs endothelial function.

Figure 1.

Vascular reactivity in the maternal aorta and uterine artery was assessed by establishing concentration response curves with the endothelial-dependent vasodilator methacholine (A and D), the endothelial-independent vasodilator sodium nitroprusside (B and E), and the vasoconstrictor phenylephrine (C and F). Four-parameter nonlinear regression models were used to assess significant differences in overall reactivity between groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 8–9. *Significantly different (p < .05) from saline controls.

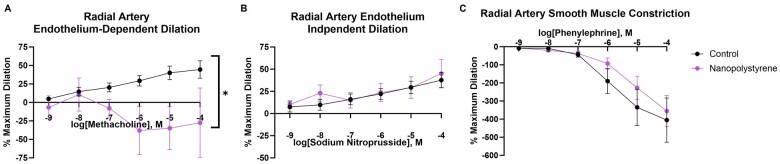

Radial artery reactivity

The radial artery, which directly influences placental perfusion, is a major resistance vessel in the uterine vascular bed, representative of the microcirculation (resistance vessels <150 µm). Reactivity of the preplacental radial artery was assessed via pressure myography. Maternal exposure to polystyrene NPs significantly blunted radial artery vasodilation in response to methacholine, an endothelium-dependent dilator (−143% compared to control at 10−4 M methacholine, Figure 2A) as compared to saline controls. Radial artery segments between groups did not demonstrate significant differences in endothelium-independent vasodilation or smooth muscle constriction in response to sodium nitroprusside or phenylephrine, respectively (Figs. 2B and 2C). These outcomes differ from those of the uterine artery, a larger vessel in the same vascular bed, and indicate that NP effects on vasculature are dependent on vessel size. Furthermore, these data indicate that the endothelium of the radial arteries leading to placental tissue is a target after pulmonary exposure to polystyrene NPs.

Figure 2.

Vascular reactivity in the uterine radial artery was assessed by establishing drug response curves with the endothelial-dependent vasodilator, methacholine (A), the endothelial independent-vasodilator, sodium nitroprusside (B), and the vasoconstrictor, phenylephrine (C). Four-parameter nonlinear regression models were used to assess significant differences in overall reactivity between groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 7–8. *Significantly different (p < .05) from saline controls.

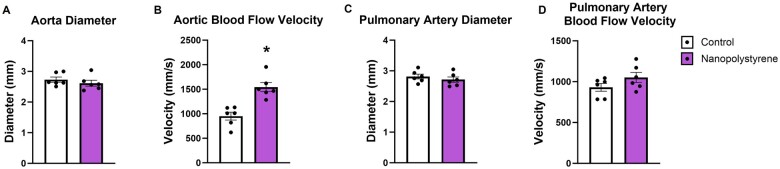

Maternal cardiovascular ultrasonography

Ultrasound of the maternal aorta and the pulmonary artery was carried out. There was no difference in aorta diameter (Figure 3A); however, aortic blood flow velocity (Figure 3B) was significantly elevated (+62%) in exposed dams as compared to controls. For pulmonary artery, there were no significant differences in vessel diameter (Figure 3C) or blood flow velocity (Figure 3D). These data suggest that the aortic responses of dams exposed to NPs are impaired within 24 h of exposure.

Figure 3.

Maternal cardiovascular function was assessed through ultrasound. The maternal aorta and pulmonary artery were examined for diameter (A and C) and velocity (B and D). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6. *Significantly different (p < .05) from control dams as determined by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups.

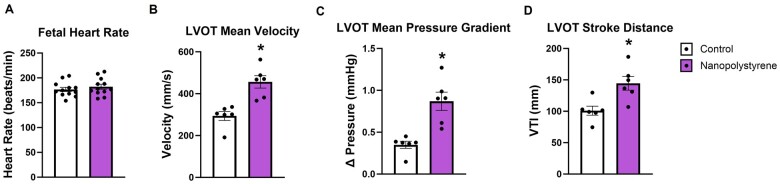

Fetal cardiac ultrasonography

The fetal heart was examined for functional endpoints. Fetal heart rate was comparable between groups (Figure 4A). Functionally, the left ventricular outflow tract demonstrated a 55% increase in velocity (Figure 4B), a 148% increase in pressure gradient (Figure 4C), and a 43% increase in stroke distance (Figure 4D) in fetuses exposed to MNP during gestation as compared to control. Therefore, the fetal hearts of exposed dams have a similar frequency of left ventricular contractions (ie, heart rate) but may have increased contractile force or altered morphology that narrows the left ventricular outflow tract.

Figure 4.

Fetal cardiac function was assessed through ultrasound. Fetal heart rate is shown in beats per minute (A). Within the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), velocity (B), pressure gradient (C), and stroke distance (D) were measured. The measured parameters represent the average of 3 fetuses for each dam. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 6. *Significantly different (p < .05) from control dams as determined by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups.

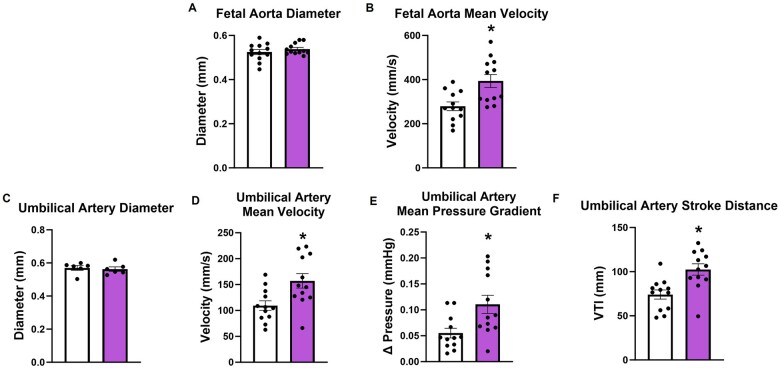

Fetoplacental vascular ultrasonography

Gestational exposure to nanopolystrene did not result in changed aortic diameter (Figure 5A) but presents an increased velocity (+41% compared to control) in the fetal aorta (Figure 5B). This is suggestive of impaired aortic compliance. The umbilical artery, which transports wastes to the fetal side of the placental labyrinth, did not differ in diameter (Figure 5C) but also exhibited marked increases in velocity (Figure 5D, +44% compared to control), pressure gradient (Figure 5E, +100% compared to control), and stroke distance (Figure 5F, +38% compared to control) after maternal NP exposure. This may suggest that the fetal umbilical-placental vasculature experiences increased vascular resistance and shear force. Overall, we have demonstrated that gestational exposure to NPs generates significant functional cardiovascular impairments in the developing fetus.

Figure 5.

Fetoplacental vascular functionality of the fetal aorta and umbilical artery was assessed through ultrasound. Fetal aorta and umbilical artery were examined for diameter (A and C) velocity (B and D). Pressure gradient (E) and stroke distance (F) were measured in the umbilical artery. The measured parameters represent the average of 3 fetuses for each dam. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 12. *Significantly different (p < .05) from control dams as determined by a two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance between groups.

Discussion

In this study, we present novel findings detailing cardiovascular outcomes caused by a single exposure to polystyrene nanoplastic in a maternal-fetal model. This exposure during late-stage pregnancy induced a significant increase in maternal heart weight, reduced fetal growth, and decreased placental weight. Agonistic challenges of the exposed maternal aortas demonstrated hyperreactivity of vascular smooth muscle to vasodilators and vasoconstrictors. Coupled with the decreased relaxation caused by methacholine, our data suggest endothelial function in the maternal aorta is impaired after NP exposure. The uterine artery did not exhibit any changes in responsivity between groups. However, radial artery endothelial-dependent dilation was significantly impaired in exposed dams. In vivo, regulation of the maternal aorta was impaired as shown by equal aortic diameters despite a significantly increased blood flow velocity in exposed dams. Fetal cardiovascular function in the pups of exposed dams was also altered, leading to increased blood velocity in the left ventricle, aorta, and umbilical artery as measured in vivo. Pulmonary exposure to nanopolystyrene therefore presents several concerns for maternal health and fetal development 24 h after a single exposure.

Few studies have examined nanoparticle toxicity during the vulnerable physiological state of pregnancy. While maternal survival was not affected after pulmonary exposure to nanopolystyrene, maternal heart weight was significantly increased. This was verified as compared to tibial length, a stable marker of rat growth. This outcome may imply an acute increase cardiovascular resistance or cardiac edema due to pulmonary NP instillation. To our knowledge, increased maternal heart weight during pregnancy has not previously been reported after maternal pulmonary exposure to metallic or carbonaceous nanoparticles. Interestingly, a recent study of polystyrene particle cardiotoxicity suggests that this specific particle type may induce cardiac hypertrophy after intratracheal instillation by means of mitochondrial disruption (Zhou et al., 2023). Future studies may investigate how acute exposure to polystyrene NPs may disrupt maternal cardiac function. The results presented in this study correlate with other groups who observed a lack of overt maternal toxicity after single (Stapleton et al., 2018) and repeated (Becaro et al., 2021; Stapleton et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2014) nanoparticle exposure. We also identified that a single NP exposure impaired fetal and placental growth which is consistent with our previous findings (Fournier et al., 2020). However, other studies utilizing nonpolymeric nanomaterials did not identify these changes (Fournier et al., 2019; Irvin-Choy et al., 2021).

Polystyrene NP deposition in the maternal lung differentially impacted the maternal vasculature based on size and tissue bed. The larger arteries such as the aorta and uterine artery serve to transport large volumes of blood while the arterioles regulate perfusion within specific tissues. The maternal aorta exhibited heightened smooth muscle responsivity and endothelial dysfunction while uterine artery reactivity was unaffected. Our finding of different responses between vascular beds is not uncommon, as a previous study also demonstrated that a single pulmonary nanoparticle exposure in male rats variably affects large vessels across different tissue beds (Abukabda et al., 2017). Interestingly, in this study, a single exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles impaired endothelium-dependent relaxation and blunted smooth muscle relaxation in the aorta whereas femoral artery function was largely unchanged. Others have identified carotid artery smooth muscle contraction to be impaired after a single nickel nanoparticle inhalation exposure in C57BL/6 mice (Cuevas et al., 2010); wherein, nanoparticle exposure blunted vascular smooth muscle responses of conduit vessels as opposed to the heightened vascular smooth muscle responses presented in this study. Another study demonstrated that a single inhalation exposure of polyamide MNPs in virgin female rats generated decreased endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent relaxation in the uterine artery, but not the aorta (Cary et al., 2023b).

Nanopolystyrene selectively impaired endothelium-dependent dilation in the radial artery of the uterine vasculature. This is consistent with evidence that nanoparticle pulmonary exposure differentially modulates vascular function between conduit vessels and resistance vessels (Abukabda et al., 2017). Microvascular impairment is consistent with other models of nanoparticle exposure for which the arterioles displayed endothelial-dependent dysfunction (Knuckles et al., 2013; Nurkiewicz et al., 2006; Stefaniak et al., 2017). Moreover, pregnant rats treated with nanoparticles via inhalation also exhibited endothelial-dependent dysfunction of the uterine microcirculation (Stapleton et al., 2013, 2018). It is during pregnancy that abnormal uterine microvascular function has the most detrimental effects. Nanoparticle-induced impairment of uterine microvascular endothelium-dependent dilation impacts blood flow to the placental and fetal compartment. In fact, it has been shown that nanomaterial inhalation during pregnancy increases placental resistance (Abukabda et al., 2019). Therefore, it is plausible that our observed radial microvascular dysfunction after nanopolystyrene exposure reduced placental perfusion and blood delivery, thus contributing to the significantly reduced fetal and placental weight reported. The mechanism behind the observed NP-induced dysfunction remains unknown and quantification of endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factors or metabolites (eg, nitric oxide, thromboxane, prostacyclin, hydrogen peroxide, cP450, etc.) is warranted. Future studies will interrogate the role of these vascular mediators in NP-induced endothelial dysfunction of the uterine microcirculation.

These results also demonstrate that maternal exposure to NPs generated extensive functional changes in the fetoplacental circulation. Increases in blood flow velocity across the left ventricular outflow tract, aorta, and umbilical artery suggest that fetal vascular control of blood flow is dysregulated. Without reductions in anatomical diameter in the aorta and umbilical artery, these findings may be the result of impaired fetal vascular compliance or functional reactivity. One study in which pregnant mice ingested polyethylene cited abnormalities in umbilical blood flow (Hanrahan et al., 2024). In other experimental models, maternal pulmonary nanoparticle exposure has led to aberrant cardiovascular function in offspring (Fournier et al., 2019, 2021b; Kunovac et al., 2020; Stapleton et al., 2013). Furthermore, nanopolystyrene beads have been shown to translocate to fetal tissues, including the fetal heart, after maternal pulmonary exposure (Fournier et al., 2020). This interaction has been shown to impair rat neonatal cardiomyocyte function in vitro (Roshanzadeh et al., 2021), unfortunately it is unclear if this is mechanism of action in our study. Due to limitations of our fetal heart image acquisition, we are unable to conclude if cardiac output or left ventricular volume differed between groups. Additionally, there may be several mechanisms by fetal cardiovascular dysfunction is induced by maternal NP exposure. It has been reported that maternal exposure to particulates has induced cardiovascular toxicity by disrupting offspring cardiac bioenergetics (Goodson et al., 2019; Hathaway et al., 2017), calcium handling (Tanwar et al., 2017), and oxidative stress response (Kunovac et al., 2019; Nichols et al., 2018; Tanwar et al., 2018). Studies are ongoing to further elucidate the developmental and generational outcomes of NP exposure.

We have shown that commercially available NPs produce adverse outcomes in a laboratory setting; however, there are multiple limitations pertaining to this study. NPs in ambient air are heterogenous, and with a very different chemical, shape, and size distribution, which would generate different biological interactions and toxicological outcomes. Additionally, pregnant dams in this study were exposed to a single bolus of NPs via intratracheal instillation instead of or more gradual inhalation exposure. Future studies should be completed utilizing an inhalation model to reduce maternal stress. Lastly, pregnant dams were acutely exposed, once, in late-stage pregnancy. Repeated NP exposure throughout pregnancy may further impair maternal and fetal cardiovascular health and the effects on fetal health could be far worse; alternatively, repeated exposure would activate compensatory mechanisms that preserve maternal health and fetal growth. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to real-world exposures.

Due to the limited toxicology reports associated with NP exposure, it is unclear if the outcomes reported in this study are unique to plastic exposures or may be extrapolated to pulmonary xenobiotic particle exposure during pregnancy. The unique physicochemical properties of each particle type (eg, metallic, carbonaceous, plastic) and any additional modification associated with particle lifecycle and weathering may influence local and systemic interactions. Therefore, it is vital to consider these properties when comparing vascular toxicities of nanoparticles. Within the scope of plastic particles, it has been demonstrated that toxicity may vary based on the polymer; however, this has primarily been tested in invertebrates or mammalian in vitro systems (Enyoh et al., 2023; Yip et al., 2022). Additionally, careful consideration of plasticizing compounds utilized in the development-specific polymers may influence endocrine function and subsequent biological responsivity. This study did not address potential hormonal aberrations. However, previous work in virgin female rats has demonstrated that a single inhalation MNP exposure decreased levels of circulating estradiol, a hormone that has been shown to modulate vasodilation; interestingly vasodilation within the uterine and radial arteries are also impaired in this model (Cary et al., 2023b). These endocrine outcomes are especially concerning in a pregnancy model given the dependence on tightly regulated hormonal signaling and the influence of sex hormones on uteroplacental vascular reactivity (Fournier et al., 2021a; Stapleton et al., 2018). Additionally, it is possible that the elevation of estradiol levels during pregnancy may confer some protection against MNP-induced endocrine disruption and vascular dysfunction.

Several factors affecting particles’ toxicity remain unknown as it pertains to NPs. For example, the timing of exposure (Stapleton et al., 2012), timing during pregnancy (Garner et al., 2022), and particle dose (Minarchick et al., 2013) influence nanoparticle toxicity but it is unclear how this may manifest for NPs. Furthermore, it is unknown whether ingestion, another major route of MNP exposure, would generate similar outcomes. Clearance and excretion mechanisms are much more limited with pulmonary exposure while some NPs ingested and directed to the portal circulation may be excreted in bile. This may result in decreased toxicity after ingestion versus a pulmonary exposure. However, this may depend on mechanism as pulmonary inflammation, systemic inflammation, and direct particle interaction with the vasculature may influence cardiovascular toxicity. Ultimately, much more work is needed to address the cardiovascular and developmental consequences of maternal NP exposure to clarify the maternal and fetal health consequences of this ubiquitous environmental contaminant.

Conclusion

In these studies, we present an assessment of maternal health, fetoplacental development, and cardiovascular function after a single pulmonary exposure to nanopolystyrene. NPs are an emerging toxicant of great concern due to inevitable human exposure and their known mobility in biological systems. Despite these concerns and the known effects of particulates on cardiovascular health, there have been no rodent studies evaluating maternal and fetal cardiovascular function after maternal NP exposure. We identified maternal macrovascular and microvascular deficits as well as functional abnormalities of the fetoplacental vasculature after NP exposure in late-stage pregnancy. Based on our findings, it is critical that NPs must be further investigated for their toxicity during pregnancy as this information will inform risk assessment and shape regulatory policy.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

C M Cary, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

S B Fournier, Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

S Adams, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

X Wang, Molecular Imaging Core, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

E J Yurkow, Molecular Imaging Core, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

P A Stapleton, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Ernest Mario School of Pharmacy, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA; Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R00-ES024783, R01-ES-031285, R01-ES-031285-S1), Rutgers Center for Environmental Exposures and Disease (P30-ES005022), and Rutgers Joint Graduate Program in Toxicology (T32-ES007148). The Rutgers Molecular Imaging Core is supported by the National Institutes of Health through an S10 instrumentation grant (Award#: 1S10OD030291-01) and by the National Science Foundation through a Major Research Instrumentation (MRI) grant (Award#: 1828332).

References

- Abukabda A. B., Bowdridge E. C., McBride C. R., Batchelor T. P., Goldsmith W. T., Garner K. L., Friend S., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2019). Maternal titanium dioxide nanomaterial inhalation exposure compromises placental hemodynamics. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 367, 51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abukabda A. B., Stapleton P. A., McBride C. R., Yi J., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2017). Heterogeneous vascular bed responses to pulmonary titanium dioxide nanoparticle exposure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 4, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S., Allen D., Phoenix V. R., Le Roux G., Durántez Jiménez P., Simonneau A., Binet S., Galop D. (2019). Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote Mountain catchment. Nat. Geosci. 12, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Amato-Lourenço L. F., Carvalho-Oliveira R., Júnior G. R., Dos Santos Galvão L., Ando R. A., Mauad T. (2021). Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 126124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amruta N., Kandikattu H. K., Intapad S. (2022). Cardiovascular dysfunction in intrauterine growth restriction. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 24, 693–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo J. A., Barajas B., Kleinman M., Wang X., Bennett B. J., Gong K. W., Navab M., Harkema J., Sioutas C., Lusis A. J., et al. (2008). Ambient particulate pollutants in the ultrafine range promote early atherosclerosis and systemic oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 102, 589–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J. (1995). Fetal origins of coronary heart disease. BMJ 311, 171–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J., Gluckman P. D., Godfrey K. M., Harding J. E., Owens J. A., Robinson J. S. (1993). Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 341, 938–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becaro A. A., de Oliveira L. P., de Castro V. L. S., Siqueira M. C., Brandão H. M., Correa D. S., Ferreira M. D. (2021). Effects of silver nanoparticles prenatal exposure on rat offspring development. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 81, 103546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen K. M., Gren L., Malmborg V. B., Shukla P. C., Tunér M., Essig Y. J., Krais A. M., Clausen P. A., Berthing T., Loeschner K., et al. (2020). Particle characterization and toxicity in c57bl/6 mice following instillation of five different diesel exhaust particles designed to differ in physicochemical properties. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 17, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibeau K., Sicotte B., Béland M., Bhat M., Gaboury L., Couture R., St-Louis J., Brochu M. (2016). Placental underperfusion in a rat model of intrauterine growth restriction induced by a reduced plasma volume expansion. PLoS One. 11, e0145982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowdridge E. C., DeVallance E., Garner K. L., Griffith J. A., Schafner K., Seaman M., Engels K. J., Wix K., Batchelor T. P., Goldsmith W. T., et al. (2022). Nano-titanium dioxide inhalation exposure during gestation drives redox dysregulation and vascular dysfunction across generations. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 19, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brahney J., Hallerud M., Heim E., Hahnenberger M., Sukumaran S. (2020). Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States. Science 368, 1257–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary C. M., DeLoid G. M., Yang Z., Bitounis D., Polunas M., Goedken M. J., Buckley B., Cheatham B., Stapleton P. A., Demokritou P. (2023a). Ingested polystyrene nanospheres translocate to placenta and fetal tissues in pregnant rats: Potential health implications. Nanomaterials (Basel) 13, 720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cary C. M., Seymore T. N., Singh D., Vayas K. N., Goedken M. J., Adams S., Polunas M., Sunil V. R., Laskin D. L., Demokritou P., et al. (2023b). Single inhalation exposure to polyamide micro and nanoplastic particles impairs vascular dilation without generating pulmonary inflammation in virgin female Sprague Dawley rats. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 20, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y. J., Park J. W., Lim Y., Seo S., Hwang D. Y. (2021). In vivo impact assessment of orally administered polystyrene nanoplastics: Biodistribution, toxicity, and inflammatory response in mice. Nanotoxicology 15, 1180–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K. D., Covernton G. A., Davies H. L., Dower J. F., Juanes F., Dudas S. E. (2019). Human consumption of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 7068–7074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas A. K., Liberda E. N., Gillespie P. A., Allina J., Chen L. C. (2010). Inhaled nickel nanoparticles alter vascular reactivity in c57bl/6 mice. Inhal. Toxicol. 22(Suppl. 2), 100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Brito W. A., Mutter F., Wende K., Cecchini A. L., Schmidt A., Bekeschus S. (2022). Consequences of nano and microplastic exposure in rodent models: The known and unknown. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 19, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déciga-Alcaraz A., Medina-Reyes E. I., Delgado-Buenrostro N. L., Rodríguez-Ibarra C., Ganem-Rondero A., Vázquez-Zapién G. J., Mata-Miranda M. M., Limón-Pacheco J. H., García-Cuéllar C. M., Sánchez-Pérez Y., et al. (2020). Toxicity of engineered nanomaterials with different physicochemical properties and the role of protein corona on cellular uptake and intrinsic ros production. Toxicology 442, 152545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessì C., Okoffo E. D., O'Brien J. W., Gallen M., Samanipour S., Kaserzon S., Rauert C., Wang X., Thomas K. V. (2021). Plastics contamination of store-bought rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 125778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Sun C., Li J., Shi H., Xu X., Ju P., Jiang F., Li F. (2022). Microplastics in global bivalve mollusks: A call for protocol standardization. J. Hazard. Mater. 438, 129490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Zhang R., Li B., Du Y., Li J., Tong X., Wu Y., Ji X., Zhang Y. (2021). Tissue distribution of polystyrene nanoplastics in mice and their entry, transport, and cytotoxicity to ges-1 cells. Environ. Pollut. 280, 116974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H., Wang L., Wang X., Xu L., Chen M., Gong P., Wang C. (2021). Microplastics in a remote lake basin of the Tibetan Plateau: Impacts of atmospheric transport and glacial melting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 12951–12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dris R., Gasperi J., Rocher V., Saad M., Renault N., Tassin B. (2015). Microplastic contamination in an urban area: A case study in greater Paris. Environ. Chem. 12, 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Du Z., Zhao D., Jing L., Cui G., Jin M., Li Y., Liu X., Liu Y., Du H., Guo C., et al. (2013). Cardiovascular toxicity of different sizes amorphous silica nanoparticles in rats after intratracheal instillation. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 13, 194–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyoh C. E., Duru C. E., Ovuoraye P. E., Wang Q. (2023). Evaluation of nanoplastics toxicity to the human placenta in systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 446, 130600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evangeliou N., Grythe H., Klimont Z., Heyes C., Eckhardt S., Lopez-Aparicio S., Stohl A. (2020). Atmospheric transport is a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions. Nat. Commun. 11, 3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. B., D'Errico J. N., Adler D. S., Kollontzi S., Goedken M. J., Fabris L., Yurkow E. J., Stapleton P. A. (2020). Nanopolystyrene translocation and fetal deposition after acute lung exposure during late-stage pregnancy. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 17, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. B., D'Errico J. N., Stapleton P. A. (2021a). Uterine vascular control preconception and during pregnancy. Compr Physiol 11, 1871–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. B., Kallontzi S., Fabris L., Love C., Stapleton P. A. (2019). Effect of gestational age on maternofetal vascular function following single maternal engineered nanoparticle exposure. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 19, 321–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier S. B., Lam V., Goedken M. J., Fabris L., Stapleton P. A. (2021b). Development of coronary dysfunction in adult progeny after maternal engineered nanomaterial inhalation during gestation. Sci. Rep. 11, 19374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franck U., Odeh S., Wiedensohler A., Wehner B., Herbarth O. (2011). The effect of particle size on cardiovascular disorders—The smaller the worse. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 4217–4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandley R. E., Jeyabalan A., Desai K., McGonigal S., Rohland J., DeLoia J. A. (2010). Cigarette exposure induces changes in maternal vascular function in a pregnant mouse model. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 298, R1249–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner K. L., Bowdridge E. C., Griffith J. A., DeVallance E., Seman M. G., Engels K. J., Groth C. P., Goldsmith W. T., Wix K., Batchelor T. P., et al. (2022). Maternal nanomaterial inhalation exposure: Critical gestational period in the uterine microcirculation is angiotensin ii dependent. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 22, 167–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves J. M., Benedetti M., d'Errico G., Regoli F., Bebianno M. J. (2023). Polystyrene nanoplastics in the marine mussel mytilus galloprovincialis. Environ. Pollut. 333, 122104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson J. M., MacDonald J. W., Bammler T. K., Chien W. M., Chin M. T. (2019). In utero exposure to diesel exhaust is associated with alterations in neonatal cardiomyocyte transcription, DNA methylation and metabolic perturbation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 16, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan J., Steeves K. L., Locke D. P., O'Brien T. M., Maekawa A. S., Amiri R., Macgowan C. K., Baschat A. A., Kingdom J. C., Simpson A. J., et al. (2024). Maternal exposure to polyethylene micro- and nanoplastics impairs umbilical blood flow but not fetal growth in pregnant mice. Sci. Rep. 14, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway Q. A., Nichols C. E., Shepherd D. L., Stapleton P. A., McLaughlin S. L., Stricker J. C., Rellick S. L., Pinti M. V., Abukabda A. B., McBride C. R., et al. (2017). Maternal-engineered nanomaterial exposure disrupts progeny cardiac function and bioenergetics. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 312, H446–h458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y. J., Qin Y., Zhang T. L., Zhu Y. Y., Wang Z. J., Zhou Z. S., Xie T. Z., Luo X. D. (2021). Migration of (non-) intentionally added substances and microplastics from microwavable plastic food containers. J. Hazard. Mater. 417, 126074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland N. A., Thompson L. C., Vidanapathirana A. K., Urankar R. N., Lust R. M., Fennell T. R., Wingard C. J. (2016). Impact of pulmonary exposure to gold core silver nanoparticles of different size and capping agents on cardiovascular injury. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 13, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Wong K. K., Li W., Zhao H., Wang T., Stanescu S., Boult S., van Dongen B., Mativenga P., Li L. (2022). Characteristics of nano-plastics in bottled drinking water. J. Hazard. Mater. 424, 127404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin-Choy N. S., Nelson K. M., Dang M. N., Gleghorn J. P., Day E. S. (2021). Gold nanoparticle biodistribution in pregnant mice following intravenous administration varies with gestational age. Nanomedicine 36, 102412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner L. C., Rotchell J. M., Bennett R. T., Cowen M., Tentzeris V., Sadofsky L. R. (2022). Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 831, 154907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J. H., Yu I. J. (2012). Estimation of human equivalent exposure from rat inhalation toxicity study of silver nanoparticles using multi-path particle dosimetry model. Toxicol. Res. 1, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- Klein M., Fischer E. K. (2019). Microplastic abundance in atmospheric deposition within the metropolitan area of Hamburg, Germany. Sci. Total Environ. 685, 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipp B. S., Ailawadi G., Sullivan V. V., Roelofs K. J., Henke P. K., Stanley J. C., Upchurch G. R. Jr (2003). Ultrasound measurement of aortic diameters in rodent models of aneurysm disease. J. Surg. Res. 112, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuckles T. L., Stapleton P. A., Minarchick V. C., Esch L., McCawley M., Hendryx M., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2013). Air pollution particulate matter collected from an Appalachian mountaintop mining site induces microvascular dysfunction. Microcirculation 20, 158–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunovac A., Hathaway Q. A., Pinti M. V., Goldsmith W. T., Durr A. J., Fink G. K., Nurkiewicz T. R., Hollander J. M. (2019). ROS promote epigenetic remodeling and cardiac dysfunction in offspring following maternal engineered nanomaterial (ENM) exposure. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 16, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunovac A., Hathaway Q. A., Pinti M. V., Taylor A. D., Hollander J. M. (2020). Cardiovascular adaptations to particle inhalation exposure: Molecular mechanisms of the toxicology. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 319, H282–H305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Li J., Zhang Y., Wang L., Deng J., Gao Y., Yu L., Zhang J., Sun H. (2019). Widespread distribution of PET and PC microplastics in dust in urban China and their estimated human exposure. Environ. Int. 128, 116–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhao Y., Dou J., Hou Q., Cheng J., Jiang X. (2022). Bioeffects of inhaled nanoplastics on neurons and alteration of animal behaviors through deposition in the brain. Nano Lett. 22, 1091–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoMauro A., Aliverti A. (2015). Respiratory physiology of pregnancy: Physiology masterclass. Breathe (Sheff) 11, 297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minarchick V. C., Stapleton P. A., Porter D. W., Wolfarth M. G., Çiftyürek E., Barger M., Sabolsky E. M., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2013). Pulmonary cerium dioxide nanoparticle exposure differentially impairs coronary and mesenteric arteriolar reactivity. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 13, 323–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols C. E., Shepherd D. L., Hathaway Q. A., Durr A. J., Thapa D., Abukabda A., Yi J., Nurkiewicz T. R., Hollander J. M. (2018). Reactive oxygen species damage drives cardiac and mitochondrial dysfunction following acute nano-titanium dioxide inhalation exposure. Nanotoxicology 12, 32–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz T. R., Porter D. W., Barger M., Millecchia L., Rao K. M., Marvar P. J., Hubbs A. F., Castranova V., Boegehold M. A. (2006). Systemic microvascular dysfunction and inflammation after pulmonary particulate matter exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 412–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurkiewicz T. R., Porter D. W., Hubbs A. F., Cumpston J. L., Chen B. T., Frazer D. G., Castranova V. (2008). Nanoparticle inhalation augments particle-dependent systemic microvascular dysfunction. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera K., Ziajahromi S., Nash S. B., Leusch F. D. L. (2023). Microplastics in Australian indoor air: Abundance, characteristics, and implications for human exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 889, 164292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cruz M., Cruz-Lemini M., Fernández M. T., Parra J. A., Bartrons J., Gómez-Roig M. D., Crispi F., Gratacós E. (2015). Fetal cardiac function in late-onset intrauterine growth restriction vs small-for-gestational age, as defined by estimated fetal weight, cerebroplacental ratio and uterine artery Doppler. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 46, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa A., Notarstefano V., Svelato A., Belloni A., Gioacchini G., Blondeel C., Zucchelli E., De Luca C., D'Avino S., Gulotta A., et al. (2022). Raman microspectroscopy detection and characterisation of microplastics in human breastmilk. Polymers (Basel) 14, 2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa A., Svelato A., Santacroce C., Catalano P., Notarstefano V., Carnevali O., Papa F., Rongioletti M. C. A., Baiocco F., Draghi S., et al. (2021). Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 146, 106274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roshanzadeh A., Oyunbaatar N. E., Ganjbakhsh S. E., Park S., Kim D. S., Kanade P. P., Lee S., Lee D. W., Kim E. S. (2021). Exposure to nanoplastics impairs collective contractility of neonatal cardiomyocytes under electrical synchronization. Biomaterials 278, 121175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senadheera S., Bertrand P. P., Grayson T. H., Leader L., Murphy T. V., Sandow S. L. (2013). Pregnancy-induced remodelling and enhanced endothelium-derived hyperpolarization-type vasodilator activity in rat uterine radial artery: Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 channels, caveolae and myoendothelial gap junctions. J. Anat. 223, 677–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruti V. C., Kutralam-Muniasamy G., Pérez-Guevara F., Roy P. D., Elizalde-Martínez I. (2022). Free, but not microplastic-free, drinking water from outdoor refill kiosks: A challenge and a wake-up call for urban management. Environ. Pollut. 309, 119800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton P. A., McBride C. R., Yi J., Abukabda A. B., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2018). Estrous cycle-dependent modulation of in vivo microvascular dysfunction after nanomaterial inhalation. Reprod. Toxicol. 78, 20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton P. A., Minarchick V. C., Cumpston A. M., McKinney W., Chen B. T., Sager T. M., Frazer D. G., Mercer R. R., Scabilloni J., Andrew M. E., et al. (2012). Impairment of coronary arteriolar endothelium-dependent dilation after multi-walled carbon nanotube inhalation: A time-course study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 13781–13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton P. A., Minarchick V. C., Yi J., Engels K., McBride C. R., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2013). Maternal engineered nanomaterial exposure and fetal microvascular function: Does the Barker hypothesis apply? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 209, 227.e221–227.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniak A. B., LeBouf R. F., Duling M. G., Yi J., Abukabda A. B., McBride C. R., Nurkiewicz T. R. (2017). Inhalation exposure to three-dimensional printer emissions stimulates acute hypertension and microvascular dysfunction. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 335, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Jin C., Bai Y., Ma R., Deng Y., Gao Y., Pan G., Yang Z., Yan L. (2022). Blood uptake and urine excretion of nano- and micro-plastics after a single exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 848, 157639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar V., Adelstein J. M., Grimmer J. A., Youtz D. J., Katapadi A., Sugar B. P., Falvo M. J., Baer L. A., Stanford K. I., Wold L. E. (2018). Preconception exposure to fine particulate matter leads to cardiac dysfunction in adult male offspring. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e010797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar V., Adelstein J. M., Grimmer J. A., Youtz D. J., Sugar B. P., Wold L. E. (2017). PM(2.5) exposure in utero contributes to neonatal cardiac dysfunction in mice. Environ. Pollut. 230, 116–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega-Herrera A., Llorca M., Borrell-Diaz X., Redondo-Hasselerharm P. E., Abad E., Villanueva C. M., Farré M. (2022). Polymers of micro(nano) plastic in household tap water of the Barcelona metropolitan area. Water Res. 220, 118645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodstrcil L. A., Tare M., Novak J., Dragomir N., Ramirez R. J., Wlodek M. E., Conrad K. P., Parry L. J. (2012). Relaxin mediates uterine artery compliance during pregnancy and increases uterine blood flow. FASEB J. 26, 4035–4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Yang Q., Long J., Ding Y., Zou X., Liao G., Cao Y. (2018). A comparative study of toxicity of TiO(2), ZnO, and Ag nanoparticles to human aortic smooth-muscle cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 8037–8049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Chen L., Chen F., Zou H., Wang Z. (2020). A key moment for tio(2): Prenatal exposure to TiO(2) nanoparticles may inhibit the development of offspring. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 202, 110911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y., Glamoclija M., Murphy A., Gao Y. (2022). Characterization of microplastics in indoor and ambient air in Northern New Jersey. Environ. Res. 207, 112142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip Y. J., Lee S. S. C., Neo M. L., Teo S. L., Valiyaveettil S. (2022). A comparative investigation of toxicity of three polymer nanoparticles on acorn barnacle (Amphibalanus amphitrite). Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. J., Son J. M., Lee J., Kim S. H., Lee I. C., Baek H. S., Shin I. S., Moon C., Kim S. H., Kim J. C. (2014). Effects of silver nanoparticles on pregnant dams and embryo-fetal development in rats. Nanotoxicology 8(Suppl. 1), 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zhao Y., Du F., Cai H., Wang G., Shi H. (2020). Microplastic fallout in different indoor environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 6530–6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Wu Q., Li Y., Feng Y., Wang Y., Cheng W. (2023). Low-dose of polystyrene microplastics induce cardiotoxicity in mice and human-originated cardiac organoids. Environ. Int. 179, 108171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuri G., Karanasiou A., Lacorte S. (2023). Microplastics: Human exposure assessment through air, water, and food. Environ. Int. 179, 108150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.