Abstract

Purpose

Advance care planning (ACP) discussions can help adolescents and young adults (AYAs) communicate their preferences to their caregivers and clinical team, yet little is known about willingness to hold conversations, content, and evolution of care preferences. We aimed to assess change in care preferences and reasons for such changes over time and examine the reasons for engaging or not engaging in ACP discussions and content of these discussions among AYAs and their caregivers.

Methods

We conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial of a novel video-based ACP tool among AYA patients aged 18–39 with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Participants were asked their care preferences at baseline, after viewing the video or hearing verbal description (post questionnaire), and again 3 months later. Three-month phone calls also queried if any ACP conversations occurred since the initial study visit. Study team notes from these phone calls were evaluated using content analysis.

Results

Forty-five AYAs and 40 caregivers completed the 3-month follow-up. Nearly half of AYAs and caregivers changed their care preference from post questionnaire to 3-month follow-up. Increased reflection and learning on the topic (n = 45) prompted preference change, with participants often noting the nuanced and context-specific nature of these decisions (n = 20). Most AYAs (60%) and caregivers (65%) engaged in ACP conversation(s), often with a family member. Disease-related factors (n = 8), study participation (n = 8), and a desire for shared understanding (n = 6) were common reasons for initiating discussions. Barriers included disease status (n = 14) and timing (n = 12). ACP discussions focused on both specific wishes for treatment (n = 26) and general conversations about goals and values (n = 18).

Conclusion

AYAs and caregivers acknowledged the complexity of ACP decisions, identifying obstacles and aids for these discussions. Clinicians should support a personalized approach to ACP that captures these nuances, promoting ACP as an iterative, longitudinal, and collaborative process.

Trial registration

This trial was registered 10/31/2019 with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT0414907).

Keywords: Adolescent and young adults, Cancer, Advance care planning, Communication

Introduction

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer often receive intensive medical care throughout their treatment and at the end-of-life (EOL), yet little is known about whether this care is consistent with their goals and values [1-3]. Advance care planning (ACP) discussions between patients and caregivers can help delineate care preferences and goals and facilitate receipt of goal-concordant care [4, 5]. Therefore, ACP communication among AYAs and caregivers is crucial for quality EOL care [6]. Previous ACP interventions with AYAs facing advanced cancer have proven to be helpful to both participants and others involved, without causing significant distress or a diminishing hope [7-9].

ACP initiation remains ad hoc [10], creating unique challenges for AYAs and caregivers. AYAs have distinct treatment preferences and EOL priorities, often emphasizing quality of life and their role in decision-making [6]. They also vary in their desired level of involvement in care decisions, reflecting their evolving independence and relationships with caregivers [11-15]. Discrepancies in AYA and caregiver EOL preferences, such as the need for prognostic information and preferred location of death [16], underscore the importance of ACP discussions.

To enhance dyadic alignment in care goals during advanced illness, we conducted a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a brief ACP video decision aid for AYAs with advanced cancer and their caregivers [17]. Our findings revealed that most AYAs and caregivers initially preferred life-prolonging care and intensive interventions during advanced illness, with many participants, regardless of whether they watched the video or not, shifting preferences towards less intensive care. We conducted a follow-up assessment 3 months later to reassess care preferences and inquire about any interim ACP conversations. This study used both quantitative and qualitative analysis of longitudinal data to (1) to assess changes in care preferences and reasons for these changes over time, and (2) to explore factors influencing engagement in ACP discussions and content of these discussions among AYAs with advanced cancer and their caregivers.

Methods

Study design, participants, and enrollment

We conducted a 1:1 pilot RCT of a 10-min video ACP decision aid among AYAs aged 18–39 with advanced cancer at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) and Massachusetts General Hospital. Eligible AYAs were English-speaking without visual impairment and had diagnosis of cancer that had progressed despite upfront treatment. Patients with low grade or indolent tumors were excluded given their long course and favorable prognosis. AYAs selected an eligible caregiver to participate with them, forming the study dyad.

Recruitment and enrollment details have been published [17]. Briefly, eligible participants were identified through patient census review and contacted to explain the study details and assess interest. Enrolled participants met with a trained research assistant (RA) for the initial study visit and provided verbal consent; written consent was waived due to minimal risk. Participants completed a baseline questionnaire on care preferences and were then randomly assigned to either the intervention group (a 10-min ACP video) or usual care (verbal descriptions of care options). All participants completed a post questionnaire immediately following. Approximately 3 months later, a phone was made to assess care preferences and ACP discussions. Electronic medical records for enrolled AYAs were reviewed at enrollment and at the 3-month follow-up for ACP documentation, including healthcare proxy, serious illness conversation, advance directive, and/or medical order to limit resuscitation.

Measures

Participants were asked their overall care preference in the setting of advanced illness (life-prolonging, selective, comfort) before, after watching the video (intervention) or hearing the description of care types (control), and again 3 months later. During the 3-month follow-up, participants could choose “unsure” as a preference option. If participants changed their care preference between the post questionnaire and 3-month timepoint, they were asked to explain. All participants were asked if they had discussed their end-of-life (EOL) care preferences since the initial study visit, and if so, with whom. Those who had such conversations were asked for details, while those who had not were asked to share their reason(s) for not having these discussions. The study team recorded responses in real-time during the 3 month follow-up call.

Analysis

Only participants who completed both the post questionnaire and the 3-month follow-up phone call were included in this analysis. Responses to the post questionnaire and 3-month questions were used to assess preference change between timepoints. All care preference responses were included and analyzed together given the findings from our prior study indicating that all participants, regardless of study arm showed a shift to less intensive care and that we did not see a significantly higher rate of concordance between AYA and caregiver preference in the video arm versus control (the primary outcome of the pilot RCT) [17]. Demographic statistics were summarized using percentages. Participants who had a preference change in overall goals were asked why their answer changed, yet many participants provided unprompted justifications for their care preferences.

Frequencies of ACP conversations reported by AYAs and their caregivers were summarized using percentages. Content analysis of real time notes from phone calls was used to further explore reasons for why and why not participants engaged in discussions around ACP and examine the content of these discussions [18, 19]. Coding of the notes from phone calls was descriptive in nature, and a codebook was developed collaboratively by J.S. and D.F. Once the codebook was finalized, both members coded notes separately and then discussed codes until agreement was reached. The two coders collaboratively identified emerging salient categories, which were reviewed by all study team members. All qualitative analyses were conducted in MaxQDA [20].

Ethical considerations

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at DFCI and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT0414907).

Results

Participant characteristics

At the 3-month follow-up, there were 85 participants, comprising 45 AYAs and 40 caregivers. Within this group, 45 participants, including 24 AYAs and 21 caregivers, had been randomized to the video arm. Most AYAs identified as female (58%), White (85%), and non-Hispanic/Latino (93%; Table 1). Caregiver demographics were similar, with 57% identifying as female, 85% White, and 95% non-Hispanic/Latino. Most (58%) of caregivers identified as the partner or spouse of the AYA, while 33% were parents. AYAs primarily had a solid tumor diagnosis (53%) and were seen in the adult oncology clinic (87%). Just over half of AYAs rated their health as either very good/excellent (24%) or good (27%), while 35% reported their health as fair or poor (7%); caregivers rated AYAs’ health similarly. Of note, 2 AYAs died, 2 were lost to follow-up, and 1 withdrew from the study between the initial study visit and follow-up.

Table 1.

Participant demographics for N = 85 participants

| AYA patients, n = 45 No, % |

Caregivers, n = 40 No, % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age in years | Mean 32.6 (SD 6.0); range 18–39 | Mean 33.7 (SD 14.4); range 19–69 |

| Gender identity | ||

| Female | 26 (58) | 23 (57) |

| Male | 19 (42) | 17 (43) |

| Racial identity | ||

| White | 38 (85) | 34 (85) |

| Asian | 2 (4) | 3 (7) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2) | 0 |

| More than one race or other | 4 (9) | 3 (8) |

| Identified ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 42 (93) | 38 (95) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Education | ||

| High school or equivalent | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Some college/college graduate | 28 (62) | 27 (68) |

| Post graduate, masters, PhD | 15 (33) | 12 (30) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or with partner | 27 (60) | 35 (88) |

| Divorced | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Single, not widowed/divorced | 17 (38) | 5 (12) |

| Caregiver role | ||

| Parent | 13 (33) | |

| Partner/spouse | 23 (58) | |

| Friend/sibling | 2 (5) | |

| Grandparent | 1 (2) | |

| Child | 1 (2) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Rating of patient health | ||

| Very good/excellent | 11 (24) | 8 (20) |

| Good | 12 (27) | 12 (30) |

| Fair | 16 (35) | 15 (38) |

| Poor | 3 (7) | 5 (12) |

| Not sure | 3 (7) | 0 |

| Site | ||

| Dana Farber Cancer Institute | 39 (87) | |

| Massachusetts General Hospital | 6 (13) | |

| Primary oncologist specialty/clinic | ||

| Adult | 39 (87) | |

| Pediatric | 6 (13) | |

| Tumor type | ||

| Central nervous system tumor | 18 (40) | |

| Hematological malignancy | 3 (7) | |

| Solid tumor | 24 (53) |

SD, Standard deviation

Changes in care preferences

Changes in care preferences between timepoints for both AYAs and caregivers are outlined in Table 2. Among 19 AYAs who selected “life-prolonging care” on the post questionnaire, 7 (37%) changed care preferences at follow-up including 5 AYAs that were “unsure”. Meanwhile, of the 20 who chose “selective care” on the post questionnaire, 8 (40%) chose “life-prolonging care” at 3 months. When considering best care for the AYA, caregivers followed a similar pattern. Out of the 17 caregivers, 6 (35%) initially opted for “life-prolonging care” but later changed their preferences, with 4 choosing “selective care”, 1 opting for “comfort care”, and 1 being “unsure”. Nine (40%) caregivers switched from selective to life-prolonging care between timepoints. Overall, 27 (60%) AYAs and 22 (55%) caregivers indicated the same preference at the post questionnaire and 3-month follow-up timepoint, while 18 (40%) AYAs and 18 caregivers (45%) reported a change in overall preference. Of these, 11 AYAs and 10 caregivers’ preferences shifted to more intensive care, compared with only 2 AYAs and 6 caregivers indicating a shift to less intensive care.

Table 2.

Comparison of care preferences from post questionnaire to 3-month follow-up among n = 45 AYAs and n = 40 caregivers

| 3 month-follow up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life-prolonging | Selective | Comfort | Unsure | TOTAL | ||

| AYAs (n = 45) | ||||||

| Post questionnaire | Life-prolonging | 12 | 1 (−) | 1 (−) | 5 | 19 |

| Selective | 8 (+) | 12 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |

| Comfort | 1 (+) | 2 (+) | 3 | 0 | 6 | |

| Unsure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 21 | 15 | 4 | 5 | 45 | |

| Caregivers (n = 40) | ||||||

| Post questionnaire | Life-prolonging | 11 | 4 (−) | 1 (−) | 1 | 17 |

| Selective | 9 (+) | 10 | 1 (−) | 1 | 21 | |

| Comfort | 0 | 1 (+) | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Unsure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| TOTAL | 20 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 40 | |

(+) indicates shift to more intensive care; (−) indicates shift to less intensive care

Unsure was not an option on the post questionnaire

At baseline, 25 (56%) of the 45 AYAs had some ACP documentation in their medical record, including healthcare proxy (n = 25; 56%), documented serious illness conversation (n=4; 9%), or advance directive and/or medical order to limit resuscitation (n = 6; 13%). When reassessed 3 months later, 6 (13%) AYAs had newly added ACP documentation in their medical records—four in the control group and two in the video study arm. ACP documentation included 1 healthcare proxy, 4 documented serious illness conversations, and 3 advance directives/medical orders to limit resuscitation.

Qualitative analysis of 3-month follow-up responses

Twenty-five AYAs and 26 caregivers provided explanations for the changes in their preferences between timepoints (Table 3); yet only 18 AYAs and 18 caregivers had documented changes in their care preferences. The responses were grouped into three main categories: further reflection and learning, experiences related to care, and issues related to clarity. Many participants (n = 45) reflected and learned more about care options between timepoints, shaping their care preferences. These reflections encompassed further consideration and discussions (n = 12), improved understanding of care options and definitions (n = 9), and enhanced clarity regarding their own goals (n = 7). Notably, 12 AYAs and 8 caregivers cited the context-specific nature of ACP decisions led to changes in preferences between timepoints. Additionally, 6 AYAs and 3 caregivers indicated that their goals might evolve in the future. Both AYAs and caregivers acknowledged the complexity of these decisions, which depended on factors such as disease stage, prognosis, other goals, and the specific illness circumstances. Care-related experiences also played a role in preference changes (n = 9), including factors related to cancer prognosis or treatment response (n = 5, including 3 AYAs) and quality of life (n = 4, 3 of which were AYAs). Some participants mentioned lack of clarity regarding their preferences (n = 4) and confusion about the definitions of care types (n = 1) as reasons for care preferences change. Interestingly, 7 participants (including 6 AYAs) noted that they did not believe their goals had changed, despite reporting a different goal at follow-up.

Table 3.

Reasons for changes in care preferences between intervention and 3-month follow-up in AYAs (n = 25) and caregivers (n = 26)

| Category (N)* | Description | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 25)* |

Caregivers (N = 26)* |

||

| Can you tell me more about why you have changed your preference from the one stated before? | |||

| Further reflection and learning (45) | |||

| Contextual decisions and nuance (20) | Choices for care may differ based on clinical situation and/or prognosis; nuance | 12 | 8 |

| Increased consideration/discussion (12) | Thought and talked more about goals | 3 | 9 |

| Clarity around definitions of care (9) | Changed identified goals after learning more about different care types | 5 | 4 |

| Shifting goals in future (9) | Clarified current priorities from expected changes to priorities in the future as disease progresses/health worsens | 6 | 3 |

| Clarity around goals (7) | Identified priorities for care made clear | 3 | 4 |

| Knowledge or additional information (1) | Did research to learn more about CPR/ventilation | 1 | 0 |

| Care-related experiences (9) | |||

| Disease experience (5) | Shift in goals related to change in cancer prognosis or treatment | 3 | 2 |

| Quality of life (4) | Wanting to prioritize good time, including considerations of symptoms/side effects | 3 | 1 |

| Lack of clarity (11) | |||

| Goals unchanged (7) | No actual change in goals at this time, some variance in understanding/goals based on when the question was asked | 6 | 1 |

| Unclear goals/priorities (4) | Not sure about current preferences | 1 | 3 |

| Unclear definitions of care (1) | Descriptions of care types are not entirely clear leading to confusion around choices | 1 | 0 |

Frequencies refer to the number of transcripts containing a given code/category. Total Ns represent the number of documents containing a coded segment for this question included in this table

ACP conversations

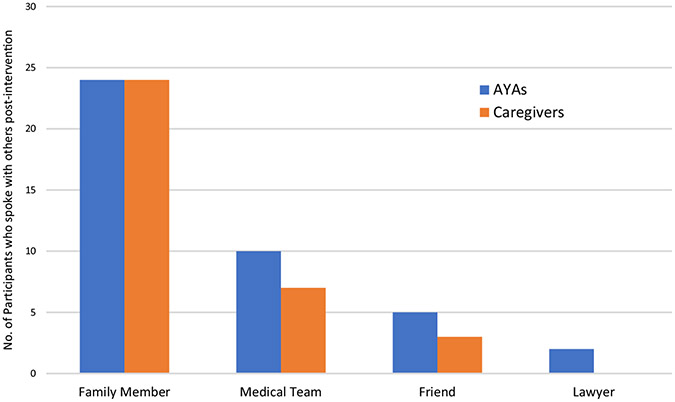

Within the 3 months after the baseline study visit, 60% (27 out of 45) of AYAs engaged in ACP conversations. Of these, 24 talked to their family, 10 to their healthcare team, 5 to a friend, and 2 to a lawyer. Among caregivers, 65% (26 out of 40) participated in ACP discussions, with 23 talking to the AYA, 5 to another family member, 7 to the AYA’s healthcare team, and 3 to a friend (Fig. 1). The intervention arm did not impact ACP conversations; roughly half of those who engaged in ACP conversations (13 of 27 AYAs and 13 of 25 caregivers) were randomized to the video intervention.

Fig. 1.

People with whom participants engaged in advance care planning discussions following the intervention for n = 27 adolescents and young adults (AYAs) and n = 24 caregivers

Table 4 presents AYAs’ and caregivers’ reasons for engaging or not engaging in ACP discussions during the 3-month period. Eight AYAs and 11 caregivers provided reasons for engaging in these conversations. Common reasons factors included disease-related considerations (n = 8), study participation (n = 6), and a desire to clarify goals and achieve a shared understanding with their care partner (n = 6). Conversely, 26 AYAs and 21 caregivers explained reasons why they did not engage in ACP discussions. The primary reasons included disease-related factors (n = 14), with some feeling that the conversation was irrelevant or untimely given their prognosis or treatment course. Time constraint (n = 12) was also frequently cited as an issue by AYAs and caregivers. Some participants did not find the conversation necessary because they had already discussed their preferences (n = 7) or believed their caregiver understood their preferences (n = 3). Additional reasons included poor receptivity (n = 8) from either the AYA or caregiver, emotional factors like fear or anxiety (n = 8), perceptions of the AYA being too young (n = 2), or simply not thinking about these topics over 3-month timeframe (n = 3).

Table 4.

Factors influencing advance care planning discussions among AYAs and caregivers

| Category (N) | Description | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 30) |

Caregivers (N = 31) |

||

| Reasons for engaging in ACP discussions (19) | 8 | 11 | |

| Disease (8) | Clinical factors/illness stage influence conversation | 2 | 6 |

| Study-prompted (6) | Research participation initiated the conversation | 3 | 3 |

| Shared understanding/planning (6) | Participants wanted to clarify goals with each other | 1 | 5 |

| Experience (2) | Conversation was triggered by viewing similar decisions/circumstances in the media or in real life among others | 2 | 0 |

| Emotion (1) | Experience prompted powerful feelings of fear and anxiety for the future that led to discussion | 0 | 1 |

| Reasons for not engaging in ACP discussions (47) | 26 | 21 | |

| Disease (14) | Some aspect of prognosis/treatment/hospital admission that affects why they do not talk, like stable disease status and lack of urgency | 8 | 6 |

| Timing (13) | Difficulties finding the right setting for the conversation: too busy, going through a hard time, the topic has not come up or been at the forefront | 7 | 6 |

| Receptivity (8) | AYA or caregiver is unwilling to have conversation | 1 | 7 |

| Emotion (8) | Feelings like fear, general emotional readiness, or trying to stay positive inhibit the conversation | 4 | 4 |

| Already done (7) | The AYA and caregiver have discussed preferences with each other in the past | 5 | 2 |

| Goals are clear (3) | The caregiver already feels they know the AYA’s preferences, or the AYA feels their caregiver already knows their goals | 1 | 2 |

| No thought (3) | This discussion has not been on their mind, so the conversation has not occurred | 3 | 0 |

| Too young (2) | Feeling that the AYA is not at the right age/life stage for this conversation | 1 | 1 |

Frequencies refer to the number of documents containing a given code/category. Total Ns represent the number of documents containing a coded segment for this question included in this table

Discussion contents and reflections

Table 5 contains information shared by the 24 AYAs and 21 caregivers regarding the content of their ACP discussions (Table 5). Most participants (n = 26) discussed their specific preferences for future treatment, while others engaged in a more general conversations about their goals and values (n = 18). Many conversations focused on establishing a mutual understanding of goals (n = 13). Other topics included discussions about decision-making roles (n = 5), sharing similar experiences (n = 4), exploring treatment options (n = 3), expressing emotions (n = 3), and preparing for acute clinical changes (n = 2).

Table 5.

Content and reflections on advance care planning conversations among n = 27 adolescents and young adults and n = 25 caregivers

| Category | Description | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AYAs (N = 27) |

Caregivers (N = 25) |

||

| Contents of ACP discussions (45) | 24 | 21 | |

| Specific wishes (26) | More precise discussion about the kind of care they would want—overall goals (13), intensive interventions (5), quality of life (4), EOL circumstances and wishes (3) | 14 | 12 |

| General conversation (18) | Broader discussion about wishes, nothing specifically about preference for treatments/interventions | 11 | 7 |

| Shared understanding (13) | Conversations to get everyone “on the same page” | 4 | 9 |

| Roles (5) | Negotiating who makes important decisions, trying to listen to and respect the AYA while discussing disagreements | 1 | 4 |

| Shared experience (4) | Talking with or about someone who went through something similar in terms of these types of decisions | 2 | 2 |

| Information (3) | Telling each other about and understanding the potential treatment options, sharing research | 1 | 2 |

| Emotion (3) | Discussion around the feelings surrounding these kinds of decisions, like anxiety or relief | 1 | 2 |

| Preparation (2) | Discussion of goals in case of acute clinical changes | 1 | 1 |

| Reflections on conversation (27) | 16 | 11 | |

| Emotion around conversation (13) | Feelings like fear, sadness, anxiety, and relief that surround ACP discussions | 8 | 5 |

| Interest (7) | Desire to have this conversation and talk more with someone, sometimes with a specific timeframe in mind | 4 | 3 |

| Paperwork (6) | Mention of ACP documentation in process or actively considering completing documentation | 4 | 2 |

| Helpfulness (5) | Feeling that this conversation was useful or would be beneficial to have in the future | 2 | 3 |

Participants shared their emotions surrounding their ACP discussions (n = 13), describing feelings such as fear, sadness, anxiety, and even relief. Five participants found the conversation helpful. Additionally, many participants considered future steps, with 7 expressing interest in further discussing their preferences, and 6 planning to begin or finalize ACP documentation.

Discussion

In this analysis of the subset of participants from a pilot RCT of a video-based ACP tool that completed the 3-month follow-up, nearly half reported a change in care preference from the post questionnaire to the 3-month follow-up, often towards more intensive care. AYAs and caregivers attributed these changes to increased reflection on preferences and learning about care options. Many participants had ACP discussions, regardless of whether they watched the video or not. These discussions were primarily with close family members, motivated by disease-related considerations, study participation, and a desire for shared understanding with their care partner. Some AYAs and caregivers chose not to participate in ACP discussions, noting disease-related factors such as stable disease and lack of time. Both general and specific discussions about care preferences were common, with some participants planning to discuss these matters with others and complete ACP documentation. Overall, participants recognized the complexity of ACP discussions and treatment decisions, acknowledging the nuanced and context-specific nature of these choices and the emotions they evoke.

In our pilot RCT study, we found a shift in care preferences to less intensive care from baseline to post questionnaire in most participants, regardless of study arm [17]. However, our current analysis reveals that many participants indicated an additional change in care preference from post questionnaire to 3-month follow up, with many again preferring more intensive care. These findings align with prior research in adults with serious illnesses, which also showed fluctuations in EOL care preferences over time [21-23]. Changing views may be especially common among AYAs as they navigate evolving decision-making roles and levels of independence [12]. Moreover, the discrete care categories we provided in our questionnaires lacked complexity and nuance, further complicating the ability to note change over time.22,23 Some participants in this cohort expressed confusion and difficulty in selecting care preferences, either due to under definitions or because they believed their responses were context-specific, and did not neatly fit into the provided categories. These findings underscore the importance of viewing ACP as a continuous and iterative process, allowing for shift and change over time, rather than a one-time, rigid decision about care preferences [24, 25]. Clinicians can play a vital role in helping patients understand care options and explore care preferences, with a need to revisit these discussions over time.

ACP discussions can promote shared understanding of care preferences, improve satisfaction with communication, prepare participants for future decision-making, and ultimately, support surrogate decision-makers during EOL decision-making [26-28]. However, initiating these discussions can be challenging. Our results reveal common reasons for and obstacles to ACP discussions among AYAs and their caregivers. Notably, participants often mentioned their involvement in the study as a motivation for engaging in ACP discussions, regardless of study arm, consistent with a previous study examining a brief ACP intervention in AYAs [29]. Simple interventions that introduce the topic of ACP can effectively stimulate further thought and deeper discussions, motivating participants to continue these conversations over time [29, 30]. Common barriers to having ACP discussions in our sample included the belief that such conversation were unnecessary or difficulty finding the time for them. These barriers echo prior research on AYAs’ attitudes towards ACP [31]. Given that ACP is most effective when initiated early, often, and before particularly acute clinical changes [25, 32], providing a gentle nudge through ACP interventions, even among groups where ACP may not seem immediately necessary, can be valuable in prompting thought and discussion around preferences.

Public understanding of ACP remains poor [33] and considerable debate exists involving the definition and intent of ACP [34, 35]. Many study participants reported having discussions regarding specific wishes for treatment, while others spoke more broadly about their wishes and what mattered to them. Conversation topics ranged from sharing stories of others with similar experiences (grandparents, friends, etc.), to discussing potential care options and the emotional aspects of EOL decision-making. ACP can encompass both specific preferences as well as overall values and life goals; notably, a consensus Delphi definition does not reference documentation or clinician involvement as essential to ACP [33, 36]. Our findings support a broader understanding of what constituents ACP, as reflected in the diverse topics covered in the ACP discussions shared by participants, as well as a predominance of ACP discussions between family members rather than with the clinical team. This is consistent with the observation that, despite engaging in ACP discussions, very few participants had ACP documentation in the medical records.

These results have several implications for future practice and research. First, our findings underscore the effectiveness of brief and simple ACP interventions in prompting ACP discussions. A variety of ACP interventions, including the 10-min video used in this study, have been well-received and considered beneficial by AYAs, without any notable increase in distress [7-9, 17]. Clinicians can take advantage of the “nudge” these interventions provide to engage in ACP conversations with AYAs and their caregivers. Second, these results affirm the emotional complexity inherent in AYA ACP discussions, laden with emotions like fear, anxiety, and relief [29]. Clinicians can name, validate, and normalize these emotions while emphasizing the importance of engaging in these discussions [37, 38]. Furthermore, EOL care decisions are complex and context-specific. When asked about their care preferences, many participants answered “it depends” on factors such as timing and clinical circumstances. As such, ACP should be viewed as an ongoing communication process that encompasses broader goals, values, and preferences with plans to regularly revisit these aspects as they evolve over time [24, 34]. Future research can delve deeper into these nuances within ACP, and explore how to support AYAs in navigating decisions as their clinical situation changes.

While this study provides valuable insights into ACP among AYAs, it has some limitations. The responses collected during the follow-up phone call were recorded as real-time notes, which might lack the completeness of an audio recording [39]. Future studies could enhance understanding by combining real-time notes with recorded in-depth interviews. Additionally, six AYAs and 11 caregivers initially participated but were unreachable for the 3-month follow-up call, potentially missing perspectives from those who disengaged and might have different attitudes towards ACP. Lastly, our study sample was predominantly White, non-Hispanic, and entirely English-speaking, which limits the generalizability of our findings. Given that ACP patterns vary by race and ethnicity [40, 41], future research should strive to amplify underrepresented voices and experiences.

Conclusion

Overall, many participants reported changes in care preference over time, often driven by deeper reflection and learning about their preferences. Common motivations for engaging in ACP discussions included disease-related factors, study participation, and a desire for shared understanding with their care partner. Conversely, barriers included disease status and time constraints. ACP discussions encompass both general and specific conversations regarding care preferences. Both AYAs and caregivers recognized the complexity, nuance, and context-specific nature of ACP decisions, along with the associated emotional aspects. Future research can explore how clinicians can support these nuances among AYAs and promote ACP as an ongoing, longitudinal process.

Funding

This project was supported by the National Institute of Health National Cancer Institute grant 1R21CA234708-01A1 (MPI: Volandes; Wolfe).

Footnotes

Ethical approval This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at DFCI and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT0414907).

Competing interests Dr. Volandes is a co-founder of and receives income from ACP Decisions, a nonprofit foundation developing the advance care planning video decision support tools that was evaluated in this study. No other authors have disclosures or conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Snaman JM et al. (2017) Palliative care involvement is associated with less intensive end-of-life care in adolescent and young adult oncology patients. J Palliat Med 20(5):509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW et al. (2015) High intensity of end-of-life care among adolescent and young adult cancer patients in the New York State Medicaid Program. Med Care 53(12):1018–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW et al. (2015) End-of-life care intensity among adolescent and young adult patients with cancer in Kaiser Permanente Southern California. JAMA Oncol 1(5):592–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyon ME et al. (2013) Family-centered advance care planning for teens with cancer. JAMA Pediatr 167(5):460–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener L et al. (2012) Allowing adolescents and young adults to plan their end-of-life care. Pediatrics 130(5):897–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack JW et al. (2021) Patient, family, and clinician perspectives on end-of-life care quality domains and candidate indicators for adolescents and young adults with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 4(8):e2121888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fladeboe KM et al. (2021) A novel combined resilience and advance care planning intervention for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: a feasibility and acceptability cohort study. Cancer 127(23):4504–4511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiener L et al. (2008) How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med 11(10):1309–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyon ME et al. (2014) A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J Adolesc Health 54(6):710–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr K et al. (2021) Factors associated with health professionals decision to initiate paediatric advance care planning: a systematic integrative review. Palliat Med 35(3):503–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pyke-Grimm KA et al. (2019) Treatment decision-making involvement in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 46(1):E22–E37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver MS et al. (2015) Adolescents’ preferences for treatment decisional involvement during their cancer. Cancer 121(24):4416–4424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pyke-Grimm KA et al. (2020) 3 dimensions of treatment decision making in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancer Nurs 43(6):436–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sisk BA et al. (2019) Ethical issues in the care of adolescent and young adult oncology patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(5):e27608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weaver MS et al. (2016) “Being a good patient” during times of illness as defined by adolescent patients with cancer. Cancer 122(14):2224–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs S et al. (2015) Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62(4):710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snaman JM et al. (2023) A pilot randomized trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 21(7):715–723 e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krippendorff K (2018) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. SAGE Publications, India [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bengtsson M (2016) How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open 2:8–14 [Google Scholar]

- 20.VERBI Software (2021) MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany. Available from maxqda.com [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janssen DJA et al. (2012) Predicting changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among patients with advanced chronic organ failure. Chest 141(5):1251–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mukamel DB, Ladd H, Temkin-Greener H (2013) Stability of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and do-not-resuscitate orders among long-term nursing home residents. Med Care 51(8):666–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wittink MN et al. (2008) Stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment after 3 years of follow-up: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Arch Intern Med 168(19):2125–2130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenberg LB, Greenwald JL, Jacobsen JC (2019) To prepare patients better: reimagining advance care planning. Am Fam Physician 99(5):278–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg AR et al. (2020) Now, more than ever, is the time for early and frequent advance care planning. J Clin Oncol 38(26):2956–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudore RL, Fried TR (2010) Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 153(4):256–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McMahan RD, Tellez I, Sudore RL (2021) Deconstructing the complexities of advance care planning outcomes: what do we know and where do we go? A scoping review. J Am Geriatr Soc 69(1):234–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song MK, Metzger M, Ward SE (2017) Process and impact of an advance care planning intervention evaluated by bereaved surrogate decision-makers of dialysis patients. Palliat Med 31(3):267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bedoya SZ et al. (2022) Adolescent and young adult initiated discussions of advance care planning: family member, friend and health care provider perspectives. Front Psychol 13:871042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morgan B, Tarbi E (2019) Behavioral economics: applying defaults, social norms, and nudges to supercharge advance care planning interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage 58(4):e7–e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiener L et al. (2022) Voicing their choices: advance care planning with adolescents and young adults with cancer and other serious conditions. Palliat Support Care 20(4):462–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Billings JA, Bernacki R (2014) Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med 174(4):620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Dyck LI et al. (2021) Understanding the role of knowledge in advance care planning engagement. J Pain Symptom Manage 62(4):778–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosa WE et al. (2023) Advance care planning in serious illness: a narrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage 65(1):e63–e78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Periyakoil VS et al. (2022) Caught in a loop with advance care planning and advance directives: how to move forward? J Palliat Med 25(3):355–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudore RL et al. (2017) Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 53(5):821–832 e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sisk BA et al. (2020) Emotional communication in advanced pediatric cancer conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage 59(4):808–817 e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg AR et al. (2016) Ethics, emotions, and the skills of talking about progressing disease with terminally ill adolescents: a review. JAMA Pediatr 170(12):1216–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tessier S (2012) From field notes, to transcripts, to tape recordings: evolution or combination? Int J Qual Methods 11(4):446–460 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carr D (2012) Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning: identifying subgroup patterns and obstacles. J Aging Health 24(6):923–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Vries K et al. (2019) Advance care planning for older people: the influence of ethnicity, religiosity, spirituality and health literacy. Nurs Ethics 26(7–8):1946–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]