Considerable advances have been made in overdose surveillance since the article “COVID-19 and the Drug Overdose Crisis: Uncovering the Deadliest Months in the United States, January‒July 2020” was published online by AJPH in April 2021.1

At the pandemic’s outset, there was ample concern that overdose deaths were spiking. However, this could not be confirmed using publicly available statistics, as detailed overdose death records were released through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) WONDER platform in yearly batches, creating a one- to two-year lag. More updated provisional trends were available, but only in rolling 12-month sums that masked month-to-month shocks.1

The analysis in AJPH cross-referenced monthly death totals through December 2019 with rolling 12-month cumulative sums ending in July 2020, to recover and make public the original monthly rates for January to July 2020.1

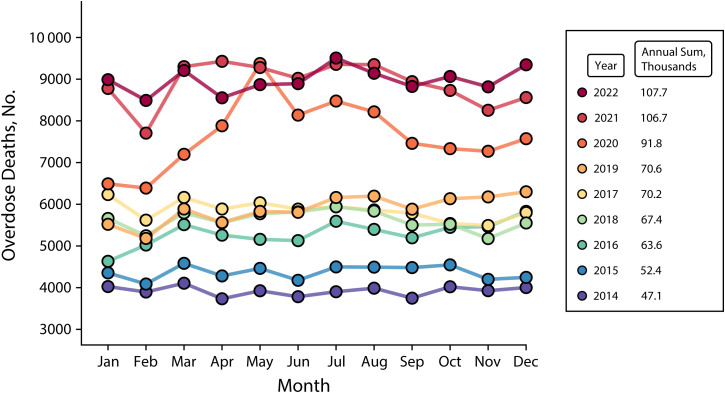

The recovered numbers revealed very sharp increases in overdose deaths in the early months of the pandemic. In May 2020, a devastating 9375 individuals died of drug overdose in the United States (Figure 1). This was a staggering sum, considering that as of 2019 the highest monthly death toll had been 6299 people.

FIGURE 1—

Monthly Overdose Deaths: United States, January 2014–December 2022

Note. One trend line is shown per year, indicated by color. The legend shows the color corresponding to each year, as well as the annual total number of deaths for that year. All values from the year 2022 are provisional and may be revised to a minor degree in subsequently released final values. Drug overdose deaths were defined using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1992) codes for underlying cause of death, including unintentional, suicide, homicide, or undetermined intent (X40–44, X60–64, X85, or Y10–14, respectively). All data can be accessed publicly at wonder.cdc.gov. This figure highlights rising counts from year to year, as well as a sharp spike in deaths during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

A NEW NORMAL FOR A WORSENING CRISIS

Unfortunately, this new level of mortality did not prove to be transient. Updated numbers show that, although death rates did decrease in the latter half of 2020 to about 7500 monthly deaths, they increased again in 2021 (Figure 1). The United States seems to have settled into a “new normal,” with a baseline rate of about 9000 overdose deaths per month during 2021 and 2022.

The total annual death toll also increased significantly during these years, rising 30.0% between 2019 and 2020, from 70 630 to 91 799 (Figure 1). It grew by an additional 16.2% in 2021, to 106 699. According to provisional data, overdose deaths stabilized in 2022, at 107 699.

The time pattern of shifts deserves careful consideration to understand possible etiologies. As spikes in overdose mortality during the pandemic were first detected, hypothesized causes included the following: (1) increased social isolation, with individuals more likely to use drugs alone, reducing naloxone provision2; (2) psychological stress leading to increased chaotic drug use3; (3) disruptions to treatment, leading to a return to drug use3,4; and (4) disruptions to the drug supply, leading to fluctuating potency and the proliferation of more dangerous drug formulations.4,5 Each of these explanations has been at least partially supported by subsequent research.

The initial pattern of increases during February through May 2020 aligns with pandemic-related disruptions to normal societal functioning, which can be measured by proxy through cellphone-derived mobility data.6 US population mobility decreased sharply between March and May 2020 and slowly increased over the remainder of the year, albeit never returning to 2019 levels.6 This closely matched shifts in overdose deaths in 2020, suggesting that short-term disruptions likely played a key role. During the pandemic, an increased rate of solitary drug use was reported.2 Disruptions to local drug supplies (e.g., through law enforcement interventions) have been shown to be associated with sharp increases in overdose deaths,7 and such disruptions were likely widespread during the early portion of the pandemic.4,5

Nevertheless, as mobility returned to normal in 2021 and 2022 and these short-term factors were largely resolved, overdose deaths reached a new, elevated baseline in the United States. It is therefore likely that the underlying longitudinal factors that worsened during the pandemic years—especially the increasingly toxic and unpredictable illicit drug supply—represent key drivers of the escalating crisis, outweighing short-term disruptions.

The increasingly varied presentations of fentanyl analogs is a key vector of risk. Counterfeit pills have widened the market of individuals exposed to fentanyls, including adolescents and individuals seeking prescription medications. Fentanyls are increasingly mixed with other synthetic and previously uncommon substances, such as the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine, novel synthetic benzodiazepines such as etizolam, other nonfentanyl synthetic opioids such as nitazenes, stimulants such as methamphetamine, and others. Polysubstance fentanyl-stimulant use is strongly on the rise, with many individuals intentionally using fentanyl and methamphetamine concurrently, and other individuals being exposed to fentanyl unknowingly through the systematic contamination of stimulants. These shifts have led to an overall context of an extremely unreliable drug market, with fluctuations in potency and drug composition driving overdose.

In response to increased risks, many individuals have sought to protect themselves by engaging with drug-checking services to better understand the nature of the drugs they consume. Also, the widespread shift from injecting to smoking opioids is likely having a protective effect against overdose risk.

Beyond overdose, other drug-related harms have also escalated before and during the pandemic. Skin and soft tissue infections have risen sharply, related to shifting injection patterns and the composition of the drug supply, especially the proliferation of xylazine mixed with fentanyls.8,9 The increasingly unpredictable sedating effects of polysubstance formulations can also render people who consume them more vulnerable to forms of victimization such as theft, or physical or sexual assault.9

Although the apparent leveling-off of overdose deaths between 2021 and 2022 is encouraging, the United States continues to suffer from an overdose death rate many times that of any other nation, and other drug-related harms remain prevalent. Restrictions on access to medications for opioid use disorder were, laudably, loosened during the pandemic, including widespread adoption of telehealth-based prescription and removal of the x-waiver requirement to prescribe buprenorphine. Nevertheless, many individuals still do not have access to treatment in a timely and low-barrier fashion, and new clinical tools are needed to respond to the unique challenges of fentanyl and polysubstance withdrawal syndromes. It is essential to continue investing in evidence-based responses, such as improved access to substance use treatment, expansion of community-based harm reduction centers, low-cost naloxone, and comprehensive housing, health care, and social support interventions.

ADVANCES IN PUBLIC ACCESS AND TRACKING OVERDOSE DEATHS

The COVID-19 pandemic also brought increased scrutiny to data transparency in health surveillance, including for overdose. In response, the CDC shortened the release delay for provisional overdose trends to six to eight months, including trends stratified by demographics and race/ethnicity—especially important given sharply rising inequalities.

Other improvements in surveillance have also been galvanized during the pandemic, including investments for state and local governments, and medical examiners and coroners, to improve the timeliness and comprehensiveness of overdose investigations.10 However, further reducing reporting delays may be difficult. A key limitation is that the underlying investigations of overdose deaths, including toxicological analysis, have historically involved long delays in many jurisdictions. For instance, in 2015 to 2016, only 82.7% of overdose deaths were registered and available for analysis by six months after occurrence—far behind reporting for other causes of death.11

Nevertheless, in the context of a constantly evolving illicit drug supply and overdose crisis, more rapid surveillance would be highly valuable. Numerous approaches have been suggested, including decreasing bureaucratic delays at the local, state, and federal levels, identifying lagging jurisdictions, and funding and incentivizing timely autopsy and toxicology processing.12 Another promising avenue can be found in provisionally coding suspected overdose deaths at the time of first contact, within days of death, supported by qualitative rapid testing that can be subsequently confirmed with quantitative toxicological testing.12

Additional data sources—not based on autopsy—offer opportunities for more rapid surveillance, yet are not always publicly available in a rapid and detailed fashion. For instance, the National Emergency Medical Services Information System offers a reliable and nationally representative measure of overdose trends with only a few-weeks lag6; however, identifiers below the level of census division are not publicly available, limiting the usefulness for state and local-level intervention. Syndromic surveillance (i.e., tracking records of nonfatal overdoses from emergency departments) also represents a powerful data stream, but improvements to public reporting are needed to guarantee timely access to detailed records.

In sum, the United States has reached a new baseline of extremely elevated drug overdose deaths in the wake of the pandemic. Great progress has been made in the speed and transparency of surveillance, yet continued efforts are required to further reduce lag times, ensure public access to novel data streams, and equip the public and policymakers with updated information to best respond to this escalating crisis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

J. Friedman received support from the UCLA Medical Scientist Training Program (National Institute of General Medical Sciences training grant GM008042).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Friedman J , Akre S. COVID-19 and the drug overdose crisis: uncovering the deadliest months in the United States, January‒July 2020. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(7):1284‒1291. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider KE , Allen ST , Rouhani S , et al. Increased solitary drug use during COVID-19: an unintended consequence of social distancing. Int J Drug Policy. 2023;111:103923. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanz LJ , Dinwiddie AT , Snodgrass S , O’Donnell J , Mattson CL. A qualitative assessment of circumstances surrounding drug overdose deaths during early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. SUDORS Data Brief. August 2022. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/databriefs/sudors-2.html. Accessed September 1, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronowitz SV , Carroll JJ , Hansen H , et al. Substance use policy and practice in the COVID-19 pandemic: learning from early pandemic responses through internationally comparative field data. Glob Public Health. 2022;7(12): 3654‒3669. 10.1080/17441692.2022.2129720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali F , Russell C , Nafeh F , Rehm J , LeBlanc S , Elton-Marshall T. Changes in substance supply and use characteristics among people who use drugs (PWUD) during the COVID-19 global pandemic: a national qualitative assessment in Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93:103237. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman J , Beletsky L , Schriger DL. Overdose-related cardiac arrests observed by emergency medical services during the US COVID-19 epidemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):562–564. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray B , Korzeniewski SJ , Mohler G , et al. Spatiotemporal analysis exploring the effect of law enforcement drug market disruptions on overdose, Indianapolis, Indiana, 2020–2021. Am J Public Health. 2023;113(7):750–758. 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciccarone D , Unick GJ , Cohen JK , Mars SG , Rosenblum D. Nationwide increase in hospitalizations for heroin-related soft tissue infections: associations with structural market conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:126–133. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montero F , Bourgois P , Friedman J. Potency-enhancing synthetics in the drug overdose epidemic: xylazine (“tranq”), fentanyl, methamphetamine, and the displacement of heroin in Philadelphia and Tijuana. J Illicit Econ Dev. 2022;4(2):204–222. 10.31389/jied.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Injury Center . Drug overdose. Enhanced state opioid overdose surveillance. October 15, 2020. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/foa/state-opioid-mm.html . Accessed February 13, 2021.

- 11. Spencer MR. Timeliness of death certificate data for mortality surveillance and provisional estimates. CDC Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Published online 2016:8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR009-508.pdf . Accessed September 1, 2023. .

- 12.Fliss MD , Cox ME , Dorris SW , Austin AE. Timely overdose death reporting is challenging but we must do better. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(7): 1194–1196. 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]