Abstract

Introduction

Vaginal surgery has a superior outcome profile compared with other surgical routes, yet skills are declining because of low case volumes. Graduating residents' confidence and preparedness for vaginal surgery has plummeted in the past decade. The objective of the present study was to investigate whether procedure‐specific simulation skills, vs usual training, result in improved operative competence.

Material and methods

We completed a randomized controlled trial of didactic and procedural training via low fidelity vaginal surgery models for anterior repair, posterior repair (PR), vaginal hysterectomy (VH), recruiting novice gynecology residents at three academic centers. We evaluated performance via global rating scale (GRS) in the real operating room and for corresponding procedures by attending surgeon blinded to group. Prespecified secondary outcomes included procedural steps knowledge, overall performance, satisfaction, self‐confidence and intraoperative parameters. A priori sample size estimated 50 residents (20% absolute difference in GRS score, 25% SD, 80% power, alpha 0.05). Clinicaltrials.gov: Registration no. NCT05887570.

Results

We randomized 83 residents to intervention or control and 55 completed the trial (2011–23). Baseline characteristics were similar, except for more fourth‐year control residents. After adjustment of confounders (age, level, baseline knowledge), GRS scores showed significant differences overall (mean difference 8.2; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.2–16.1; p = 0.044) and for VH (mean difference 12.0; 95% CI: 1.8–22.3; p = 0.02). The intervention group had significantly higher procedural steps knowledge and self‐confidence for VH and/or PR (p < 0.05, adjusted analysis). Estimated blood loss, operative time and complications were similar between groups.

Conclusions

Compared to usual training, procedure‐specific didactic and low fidelity simulation modules for vaginal surgery resulted in significant improvements in operative performance and several other skill parameters.

Keywords: gynecologic surgery, low fidelity simulation, surgical education, vaginal hysterectomy

Vaginal surgery has a superior outcome profile compared with other surgical routes, yet vaginal surgery skills are declining because of low case volumes. Our randomized controlled trial showed operative transferability of skills acquired through procedure‐specific low‐fidelity simulation in novice gynecology residents. Several other skill parameters also improved through training.

Abbreviations

- AR

anterior repair

- CI

confidence interval

- GRS

global rating scale

- ObGyn

Obstetrics and Gynecology

- OR

operating room

- PR

posterior repair

- VH

vaginal hysterectomy

Key message.

Procedure‐specific didactic and low fidelity vaginal surgery simulation modules designed for junior gynecology residents result in improved self‐confidence and skill transferability to the real operating room.

1. INTRODUCTION

Vaginal surgery is a core competency of a newly graduating obstetrician gynecologist. The United States Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education‐required minimum of 15 vaginal hysterectomy (VH) cases per resident, for achieving competency, has stayed stable over time. 1 Evidence shows that residents are, for the most part, achieving these numbers. 2 While 90% of residency program directors feel graduates can independently perform a VH, 3 fellowship directors display a perception of considerable deficiency, stating only 20% of their first‐year fellows are able to perform an independent VH, 23% an anterior repair (AR) and 30% a posterior repair (PR). 4

A survey of Canadian surgical specialties, including 5‐year Obstetrics and Gynecology (ObGyn) residency programs, showed ObGyn residents had fewer surgical training months per year than other surgical residents (4.9 vs. 8.5 months; p = 0.001). 5 Additionally, only 40% of ObGyn programs vs 76% of other programs used a local program‐specific surgical training curriculum (p = 0.054). 5 Most program directors who did not have access to a standard training curriculum wished to have one implemented that would allow novice surgeons to practice basic surgical skills in simulation laboratories, where errors and directed feedback in a safe environment catalyze learning. 5 There is ample evidence that simulation improves students' basic skills, satisfaction, and confidence 6 while increasing the numbers of performed procedures. 7 However, existing surgical training models or curricula, with the exception of fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery 8 and related laparoscopic training models, 9 do not have level one evidence of skill transferability to the real operating room (OR) environment. We hypothesized that procedure‐specific training modules consisting of didactic teaching, procedural training and independent practice on low fidelity simulation models could fill this gap. Our objective was to investigate whether these procedure‐specific training modules result in improved operative performance by junior gynecology residents on corresponding procedures in the real OR, when compared to usual training.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Design

We performed a randomized controlled single‐blind trial of a procedural intervention vs usual training in junior gynecology residents for three index vaginal surgery procedures: VH, AR, and PR.

2.2. Participants, sites and randomization

Participants were eligible if they had completed fewer than five of each index procedure during residency prior to enrollment. Residents were invited to participate at three Canadian academic training sites (2011–2023). Training sites had to fulfill the requirement of a mandatory ObGyn resident rotation in urogynecology, with preceptor academic surgeon educators (urogynecologists) dedicated to routine instruction and a clinical practice in vaginal surgery. Prior to administering the teaching intervention, they watched instructional videos describing the low fidelity simulation and reviewed the scoring system designed for each procedure (consisting of a total score minus time and predetermined errors). Participants were recruited by research coordinators during resident events such as academic day and randomized using opaque sealed sequentially numbered envelopes via computer‐generated random allocation software to intervention or control. At a later date, the randomized participants were asked to provide demographic data including resident age, sex, residency level, and previous surgical experience defined as index procedures previously performed independently in the OR. A baseline pretest consisting of multiple choice and knowledge questions was administered to all recruited residents. The trial was approved by institutional research ethics boards at all participating institutions and all participants signed informed consent.

2.3. Intervention

We previously published initial validation of our intervention. 10 The intervention consisted of the following:

Procedure‐specific didactic online module, including a description of theory, informed consent, patient positioning, antibiotics and wound basics, anesthesia, relevant anatomy, procedural steps, videos of the models as well as videos of actual OR procedures. Completion of the module was followed by a written post‐test. A passing grade was required for intervention residents to proceed to the next step of

Training on procedure‐specific low fidelity models, designed at our institution specifically for this trial. 10 This training consisted of both independent and supervised practice by the surgeon preceptors at each site, who determined operative readiness via direct observation of surgical skills on the models. Intervention residents who had been deemed competent, and control residents (usual preparation for OR performance) proceeded to supervised cases of each index surgery in the OR. Blinding: Attending surgeon proctors who rated OR performance were different from surgeon preceptors and were blinded to residents' group allocation.

2.4. Outcomes

Post‐training proctor evaluation in the OR consisted of:

-

1

A global rating scale (GRS) of surgical skill, 11 , 12 validated for use in gynecological procedures 13 , 14 , 15 and evaluating seven components of surgical performance including respect for tissue, time and motion, instrument handling, knowledge of instruments, use of assistants, flow of operation, knowledge of specific procedure (5‐point Likert scale, maximum attainable score 35);

-

2

A procedure‐specific steps scale, for each index procedure. It was developed by expert consensus and based on a standard gynecologic surgical textbook. Proctors rated the resident's performance in following the surgical steps, as NO (score of 0), PROMPTED (score of 1) and YES (score of 2);

-

3

An overall impression of resident surgical independence in performance that was assessed by one question, on a 4‐point Likert scale, with questions stems ranging from “unable to perform” = 0 to “competent to perform unsupervised” = 4. Participants rated their own performance via

-

1

A validated resident self confidence rating scale, evaluating six components of surgical self‐confidence in the OR on a five‐point Likert scale (maximum attainable score 30) 16 ;

-

2

Resident satisfaction with procedural training (one question, 5‐point Likert scale, with possible answers ranging from “very unsatisfied” = 0 to “very satisfied” = 5).

Primary outcome measure was the GRS score of intervention vs control participants, as rated by attending staff during performance of VH, AR and PR respectively, in the real OR.

Secondary outcome measures included attending staff‐rated procedural steps scale scores and overall impression of performance scores (intervention vs. control) and resident‐rated self‐confidence and satisfaction during performance of VH, AR, and PR respectively, in the real OR. Additionally, we compared intraoperative parameters of OR time (minutes), estimated blood loss (mL) and complications of intervention vs control participants.

2.5. Sample size

We used the GRS developed by Reznick et al. 11 and previously used to compare gynecology residents trained on an episiotomy repair module vs controls. Banks et al established a 21% significant difference in scores for the episiotomy repair module vs controls. 17 As our index procedures are more advanced then episiotomy repair, we determined that 50 residents (25 per group) were required to find a 20 point overall difference (out of 100) in mean GRS score between intervention and control residents, with a standard deviation of 25 points (to account for the variation in surgical skill of residents), 80% power and a significance level of 0.05.

2.6. Statistical analyses

For each procedure, t‐test was used to compare the continuous scales between intervention and control groups. All continuous scales were rescaled to have a range of 0 to 100 for ease of interpretation. Ordinal scales (i.e., overall impression of performance scale and resident satisfaction scale) were compared between group using chi‐square test and were analyzed as binary variable (<3 vs. ≥3) as few participants (n ≤ 3) had a score of 1 or 4. Supplemental analysis adjusted for age, residency level and pretest score (factors that were expected to correlate with the scales based on prior knowledge and/or factors that were different between groups) was performed for all the scales using linear or logistic regression. Results are presented as differences in mean and odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (CI). For GRS and self confidence rating scale, as the components of the scale were not procedure specific, we further performed an analysis by combining all the procedures together to estimate the overall effect of the intervention. Mixed effects linear regression with subject‐specific random intercept term was used. OR time and estimated blood loss were compared between groups by Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Due to moderate dropout rates in this study, we performed a sensitivity analysis by imputing the missing data (i.e., an intention‐to‐treat [ITT] analysis). We imputed missing data points using multiple imputation (200 imputations) by the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Variables included in the imputation model were age, sex, residency level, pretest score and the scores from all the scales considered.

Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding fourth year residents as it was believed that the intervention might not benefit more senior residents. Subgroup analysis by residency level was also considered. Analysis was performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

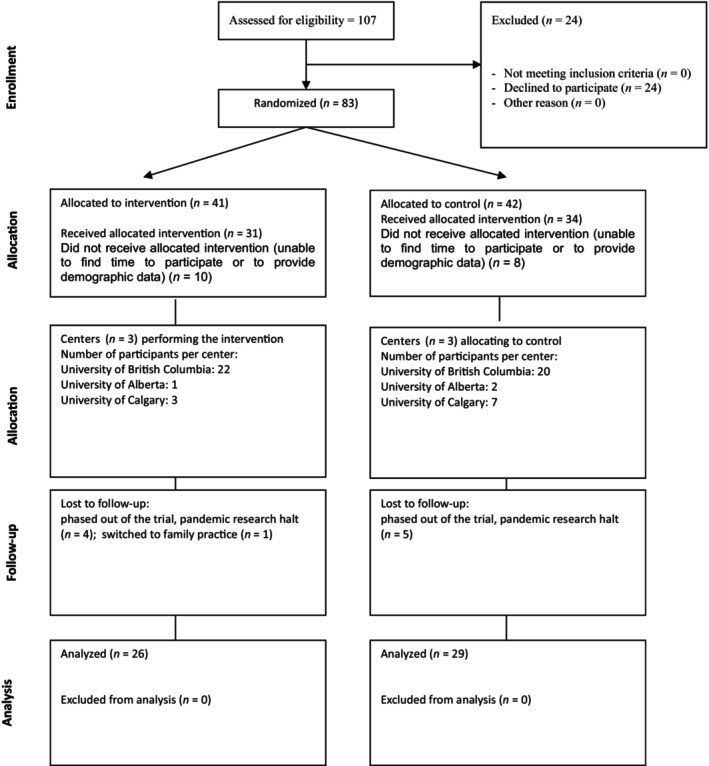

Out of 107 eligible residents (June 2011–July 2023), 83 were randomized and 55 completed the trial (26 intervention and 29 control, Figure 1). A total of 18 were unable to participate because of time constraints and were lost to follow‐up prior to the start of the trial (10 intervention and 8 control). They did not provide any demographic data. Dropout rate of residents who started the trial was 10/65 (15%). Most residents completed more than one index procedure for the trial (total number of OR events 63 intervention and 61 control). The majority of participants were female and there were more participants in the fourth year of residency in the control than intervention group (20.7% vs. 7.7% respectively), with no other demographic differences between those who did and did not complete the trial protocol (Table 1). The various descriptive scale scores by group and index procedure are detailed in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | Per‐protocol analysis a | ITT analysis b | Completed protocol | p‐value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 29) | Intervention (n = 26) | Control (n = 34) | Intervention (n = 31) | Yes (n = 55) | No (n = 10) | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Missing, n | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.389 |

| Mean (SD) | 28.0 (27.0, 30.0) | 28.0 (27.5, 29.0) | 28.6 (2.5) | 28.3 (2.0) | 28.6 (2.4) | 27.9 (1.4) | |

| Range | (25.0, 36.0) | (25.0, 34.0) | (25.0, 36.0) | (25.0, 34.0) | (25.0, 36.0) | (25.0, 30.0) | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||

| Female | 25 (86.2) | 23 (88.5) | 30 (88.2) | 28 (90.3) | 48 (87.3) | 10 (100.0) | 0.232 |

| Male | 4 (13.8) | 3 (11.5) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Residency level, n (%) | |||||||

| 1 | 6 (20.7) | 9 (34.6) | 8 (23.5) | 11 (35.5) | 15 (27.3) | 4 (40.0) | 0.712 |

| 2 | 10 (34.5) | 6 (23.1) | 11 (32.4) | 8 (25.8) | 16 (29.1) | 3 (30.0) | |

| 3 | 7 (24.1) | 9 (34.6) | 9 (26.5) | 10 (32.3) | 16 (29.1) | 3 (30.0) | |

| 4 | 6 (20.7) | 2 (7.7) | 6 (17.6) | 2 (6.5) | 8 (14.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Performed the procedure independently, n (%) | |||||||

| Any of the following | 9/28 (32.1) | 5/22 (22.7) | 10/32 (31.3) | 5/26 (19.2) | 14/50 (28.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 0.353 |

| Anterior repair | 5/27 (18.5) | 1/23 (4.3) | 6/31 (19.4) | 1/27 (3.7) | 6/50 (12.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Posterior repair | 4/27 (14.8) | 2/23 (8.7) | 5/31 (16.1) | 2/27 (7.4) | 6/50 (12.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 4/27 (14.8) | 2/23 (8.7) | 5/31 (16.1) | 2/27 (7.4) | 6/50 (12.0) | 1/8 (12.5) | 1.000 |

| Anal sphincteroplasties/fourth degree tear repairs | 3/28 (10.7) | 1/23 (4.3) | 3/33 (9.1) | 1/28 (3.6) | 4/51 (7.8) | 0/10 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Pretest score, % | |||||||

| Missing, n | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0.841 |

| Mean (SD) | 60.2 (13.4) | 58.3 (11.6) | 59.5 (13.3) | 58.8 (11.3) | 59.3 (12.5) | 58.3 (10.3) | |

| Range | (35.0, 90.0) | (35.0, 90.0) | (35.0, 90.0) | (35.0, 90.0) | (35.0, 90.0) | (45.0, 75.0) | |

| Pretest score ≥60%, n (%) | 14/28 (50.0) | 12/26 (46.2) | 14/30 (46.7) | 14/30 (46.7) | 26/54 (48.1) | 2/6 (33.3) | 0.675 |

Per‐protocol analysis included individuals who completed the protocol, that is, they have been assessed for at least one index procedure in the OR.

ITT analysis included all individuals who were randomized.

p‐value was based on t‐test, chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate.

Abbreviation: ITT, intention‐to‐treat; SD, standard deviation.

TABLE 2.

Unadjusted comparison (per protocol) of scales for each index procedure between the groups.

| Variable | Anterior repair | Posterior repair | Vaginal hysterectomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 22) | Intervention (n = 22) | p‐value | Control (n = 23) | Intervention (n = 21) | p‐value | Control (n = 16) | Intervention (n = 20) | p‐value | |

| Global rating scale (GRS), % | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 56.5 (20.6) | 60.6 (18.6) | 0.498 | 52.4 (21.2) | 51.2 (17.7) | 0.844 | 42.2 (19.7) | 50.9 (14.1) | 0.132 |

| Range | (17.9, 96.4) | (25.0, 89.3) | (21.4, 96.4) | (21.4, 89.3) | (7.1, 71.4) | (21.4, 82.1) | |||

| GRS*, n (%) | |||||||||

| Q1 ≥ 3 | 20 (95.2) | 21 (95.5) | 1.000 | 19 (86.4) | 19 (90.5) | 1.000 | 14 (87.5) | 20 (100.0) | 0.190 |

| Q2 ≥ 3 | 14 (66.7) | 17 (77.3) | 0.438 | 15 (68.2) | 11 (52.4) | 0.289 | 10 (62.5) | 11 (55.0) | 0.650 |

| Q3 ≥ 3 | 15 (71.4) | 18 (81.8) | 0.420 | 15 (68.2) | 15 (71.4) | 0.817 | 10 (62.5) | 15 (75.0) | 0.418 |

| Q4 ≥ 3 | 20 (95.2) | 20 (90.9) | 1.000 | 17 (77.3) | 20 (95.2) | 0.185 | 12 (75.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.675 |

| Q5 ≥ 3 | 15 (71.4) | 20 (90.9) | 0.132 | 15 (68.2) | 14 (66.7) | 0.916 | 6 (37.5) | 15 (75.0) | 0.023 |

| Q6 ≥ 3 | 13 (61.9) | 18 (81.8) | 0.146 | 9 (42.9) | 13 (61.9) | 0.217 | 6 (37.5) | 12 (60.0) | 0.180 |

| Q7 ≥ 3 | 17 (81.0) | 20 (90.9) | 0.412 | 16 (76.2) | 18 (85.7) | 0.697 | 10 (62.5) | 20 (100.0) | 0.004 |

| Procedure specific scale, % | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 84.1 (13.7) | 87.8 (12.2) | 0.365 | 75.3 (18.5) | 84.8 (13.7) | 0.061 | 70.6 (20.4) | 82.6 (15.3) | 0.055 |

| Range | (50.0, 100.0) | (55.6, 100.0) | (18.2, 100.0) | (54.5, 100.0) | (35.0, 100.0) | (45.0, 100.0) | |||

| Resident self confidence rating scale, % | |||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 48.7 (15.0) | 54.6 (13.6) | 0.202 | 46.4 (17.9) | 55.0 (12.0) | 0.078 | 44.3 (17.9) | 59.2 (10.4) | 0.005 |

| Range | (8.3, 75.0) | (25.0, 75.0) | (8.3, 75.0) | (29.2, 75.0) | (8.3, 70.8) | (37.5, 83.3) | |||

| Surgical performance scale ≥3 a | 13/22 (59.1) | 16/22 (72.7) | 0.340 | 11/23 (47.8) | 8/21 (38.1) | 0.515 | 3/16 (18.8) | 8/20 (40.0) | 0.169 |

| Resident satisfaction scale ≥3 a | 15/21 (71.4) | 15/21 (71.4) | 1.000 | 10/22 (45.5) | 15/21 (71.4) | 0.084 | 3/13 (23.1) | 17/19 (89.5) | <0.001 |

Few participants (n = 3) had a score of 1 or 4 and so the scale was considered as a binary variable.

For global rating, procedure specific and resident self confidence rating scales, they were rescaled to have a range of 0 to 100 for ease of interpretation. p‐value was based on t‐test, chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. Q1: respect for tissue; Q2: time and motion; Q3: instrument handling; Q4: knowledge of instruments; Q5: use of assistants; Q6: flow of operation Q7: knowledge of specific procedure.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

For the primary outcome of skill transferability, the mean overall GRS scores were not significantly different between intervention and control groups, in a per‐protocol unadjusted analysis (Table 2). When broken down into individual components of skill, “Use of assistants” (p = 0.023) and “Knowledge of specific procedure” (p = 0.004) were significantly improved in the intervention group and for VH in the per‐protocol unadjusted analysis (Table 2).

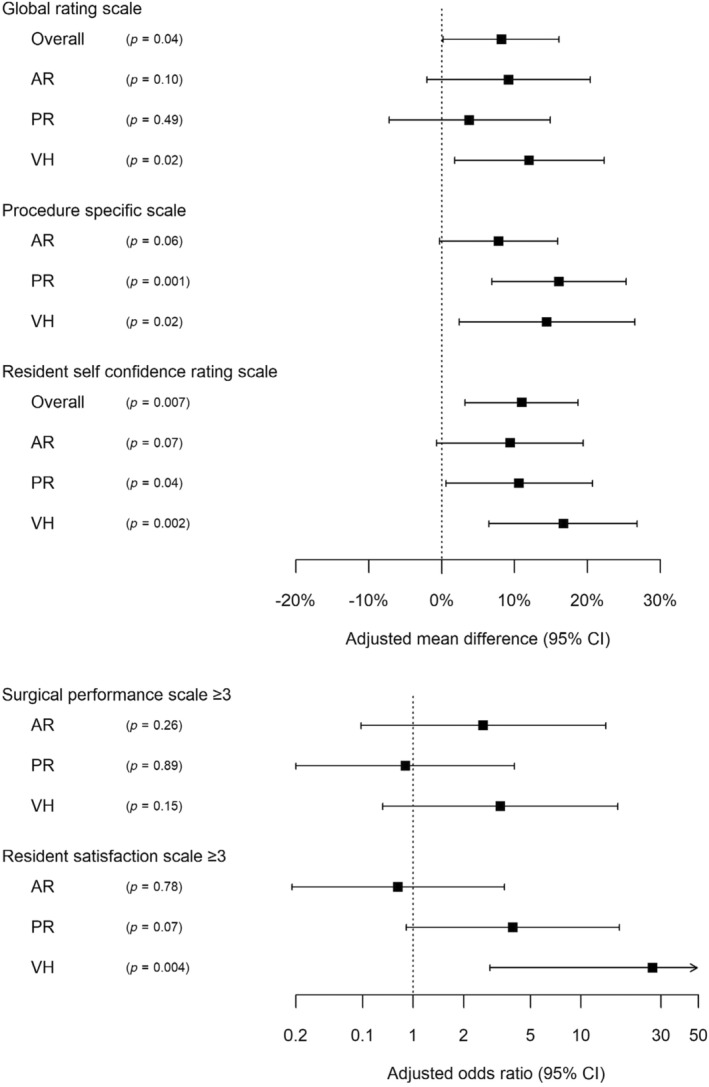

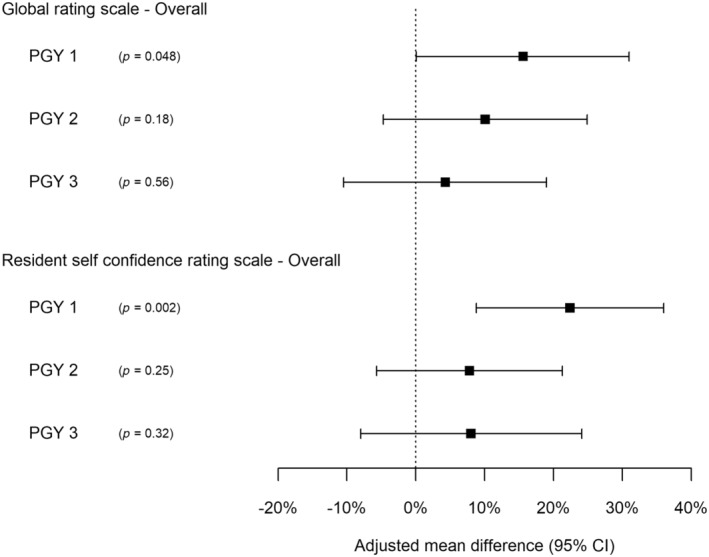

GRS scores were statistically significant after adjusting for potential confounders, overall (8.2% mean difference, 95% CI: 0.2–16.1, p = 0.044) and for VH (12.0% mean difference, 95% CI: 1.8–22.3, p = 0.023) but not for AR or PR (Figure 2). This difference was greatest in the most junior (PGY‐1) residents overall (15.6% mean difference, 95% CI: 0.1–31.0, p = 0.048; Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Estimated difference between intervention and control residents by adjusted regression analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Estimated difference between intervention and control residents stratified by residency year by adjusted regression analysis*. *: Analysis within PGY‐4 was not considered as there were too few PGY‐4 residents randomized to receive the intervention.

For the secondary outcome of procedure‐specific steps knowledge in a per‐protocol analysis, scores were not significantly different between groups in the unadjusted analysis (Table 2), but were higher in intervention vs control residents for VH (14.4% mean difference, 95% CI: 2.4–26.5, p = 0.021) and PR (16.1% mean difference, 95% CI: 6.9–25.3, p = 0.001), but not for AR (7.8% mean difference, 95% CI: −0.3 to 15.9, p = 0.06) in the adjusted analysis (Figure 2).

For the secondary outcome of surgical performance scale ≥3, there were no significant intervention improvements in any of the index procedures (Table 2; Figure 2).

Self‐confidence improved significantly for VH in the unadjusted analysis (p = 0.005; Table 2). In the adjusted analysis, it improved significantly overall and for VH and PR (p < 0.05 for all), with greatest improvement in the most junior PGY‐1 residents (mean difference overall 22.4%, 95% CI: 8.8–36.0, p = 0.002; Figures 2 and 3).

For the secondary outcome of resident satisfaction scale ≥3, scores were significantly higher in intervention vs control residents for VH only (aOR 26.7, 95% CI: 2.9–249.56, p = 0.004) and not for AR or PR (Table 2; Figure 2).

Results from the intention‐to‐treat analysis were similar for the primary and secondary outcomes. Analysis excluding fourth year residents tended to result in slightly larger estimated effect of the intervention when compared to the main adjusted analysis, but with no major changes in findings.

Intraoperative parameters of OR time, estimated blood loss and complications were similar between groups (Table 3). The only complication recorded in the trial was a bladder suture during AR in the control group, recognized and removed intraoperatively.

TABLE 3.

Operating room time and estimated blood loss for each index procedure.

| Variable | Anterior repair | Posterior repair | Vaginal hysterectomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 22) | Intervention (n = 22) | p‐value* | Control (n = 23) | Intervention (n = 21) | p‐value* | Control (n = 16) | Intervention (n = 20) | p‐value* | |

| OR time | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 44 (33, 55) | 35 (25, 49) | 0.219 | 59 (40, 72) | 50 (40, 69) | 0.981 | 55 (50, 75) | 60 (50, 74) | 0.738 |

| Range | (20, 154) | (13, 150) | (20, 154) | (20, 150) | (35, 83) | (23, 150) | |||

| Estimated blood loss | |||||||||

| Median (IQR) | 50 (50, 100) | 63 (50, 100) | 0.433 | 75 (50, 150) | 100 (75, 150) | 0.319 | 100 (50, 125) | 150 (88, 175) | 0.098 |

| Range | (10, 500) | (20, 250) | (10, 500) | (20, 300) | (25, 500) | (50, 300) | |||

p‐value was based on Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; OR, operating room.

4. DISCUSSION

Our randomized controlled trial of vaginal surgical education showed that training on procedure‐specific low fidelity simulation models results in transferability of skills to the OR. The greatest benefits were for the highest stakes procedure of VH and in the most junior residents. Additionally, training resulted in selected improvements in knowledge of procedural steps, self‐confidence and satisfaction.

Although we reached the a priori total number of 50 residents to complete the trial, recruitment and retention were extremely challenging due to several factors. As this was a research trial, outside accepted educational standards, residents were not afforded protected time for didactic learning, low fidelity model practice, or for OR assistance. Preceptors expressed that in an ideal world without competing clinical responsibilities, intervention participants could have practiced more. Moreover, the COVID pandemic halted study recruitment which did not resume post COVID, due to a rebound in clinical care duties for residents. Although teaching on the models was standardized, we did not standardize the amount of time spent in individual practice and such variations may have accounted for increased benefits in more junior residents. However, we also hoped our intervention would raise awareness of individual limitations and guide practice in adult learners. We did not account for baseline skill level and did not capture difficulty of the procedure as potential additional confounders. We believe that, although control residents were blinded to the details of surgical education intervention and did not have access to alternative low fidelity simulation, participation in this trial could have prompted more effort to prepare for the OR. This may explain the lack of significant differences between intervention and control participants for some of the scale scores. Despite the randomized controlled trial design, there was an unexpected imbalance in the residency level between the randomized groups and hence we added a supplemental adjusted regression analysis to account for that. Blinding proctors who assessed residents in the OR to group allocation required different surgeons as preceptors in simulation. To increase generalizability, proctors were attending surgeons who generally use scales such as GRS for routine resident education. Some of the proctors were unwilling or unable to complete the resident performance assessments, which explains a proportion of our dropout rates. Moreover, proctor surgeons not familiar with details of the simulation may have been more critical of surgical technique for specific index procedures, because of variability in surgical technique between supervising attending surgeons. This may explain the lack of improvement in the overall 4‐item surgical performance scale, and differences in global improvement between VH (fairly standard operative technique from surgeon to surgeon) and AR or PR (different techniques). Despite these limitations, this was a rigorously conducted randomized controlled trial with validated assessment tools and blinded assessments. It showed significant improvements in many areas of resident performance. Our overall improvement scores were comparable to another surgical education trial of skill transferability in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, which included module didactic teaching and low fidelity simulation, and resulted in an overall 15% improvement in technical skill measured via global assessment scale. 9 We conducted the research in three different academic centers, exposed to multiple real life constraints, rendering our findings generalizable across gynecologic surgery training programs. Based on this study and our results, we recommend inclusion of our vaginal surgical models in the surgical teaching curricula for ObGyn residency programs. We do not anticipate implementation to take nearly as much time as the research into our models; as a matter of fact we were entreated to share our models and curriculum for standard education at our center, but were unable to release them prior to completion of data collection and analysis. We plan to implement our curriculum locally in the near future and continue to monitor its uptake in order to refine educational efforts moving forward.

Inadequate surgical exposure to certain procedures is a recognized challenge for resident education in ObGyn, 18 and simulation has been proposed as a solution to prepare residents for operative opportunities earlier in residency. VH in particular, despite its superior patient outcomes compared with other surgical routes of hysterectomy, has been associated with the most vertiginous and worrisome drop in self‐perceived trainee preparedness for its execution at graduation (from 31.8% to 12.1%, 2014 to 2021, p = 0.03). 19 More recently, the emergence of a worldwide pandemic exerted significant pressure on existing training infrastructure, underlining the need for standard surgical training curricula independent of external influences. Our trial has shown that, with supervised practice, it is possible to initiate first‐year residents into the practice of advanced vaginal surgery procedures with no additional complications. This is consistent with prior research showing that adequately supervised surgical trainees do not cause more surgical complications. 20 Existing model‐based vaginal surgery training curricula improve learner satisfaction and increase the number of performed hysterectomies, 7 , 21 yet they are not widely implemented because they lack evidence of improved performance in real clinical scenarios.

The practice of surgery requires the development of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Knowledge can be successfully acquired through didactic instruction. Basic skills can be taught in a skills laboratory and our trial shows a surgical preceptorship model designed to encourage deliberate practice. However, surgical attitudes of an expert surgeon are traditionally thought to be acquired through trial, error and repetition. Low fidelity models, by their lack of realism, fail to capture the complexity of clinical problems and the stressful environment of the real OR. The Dreyfuss model describes an expert as someone who uses pattern recognition to deal with stressful situations, without need for extensive analysis or planning. 22 It is unclear how much repetition in a simulation lab is required for pattern recognition to emerge.

Our trial showed clear separation between skill acquisition of junior vs senior residents. This reinforces the fact that early and advanced learners have varied needs within a training curriculum, and surgical educators must plan to accommodate these different needs accordingly. 23 While junior learners may benefit from surgical preceptorship and proctorship, senior learners may better advance their skills through a coaching model, in which guided discovery serves to achieve progressive improvement of a highly specific skill, according to individual needs. 24 Refining existing skills and taking them to the next level also requires adaptive learner practices on the part of surgical trainees. 25

Cultivating surgical autonomy is a prerequisite for independent surgical practice. In a survey study of factors contributing to attending surgeons' allocation of operative autonomy to trainees, self‐confidence was rated as important by almost half. 26 A majority of gynecologic surgery trainees are currently female. With known gender differences in worry and interpretation of uncertainty, 27 increasing generational risk aversion, 28 and recent evidence of disparities in operative experience of female and male surgical residents, 29 educational interventions that improve early trainee self‐confidence are a valuable tool to pursue gender equity and adapt to changing learner needs in surgical education.

5. CONCLUSION

Our randomized controlled trial showed transferability of skills acquired in a low fidelity simulation environment to the real OR. Further research will define vaginal model pass‐fail scores for summative assessments in each index procedure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, data curation: Roxana Geoffrion, Nicole A. Koenig, Geoffrey W. Cundiff and Nicole J. Todd. Investigation, writing: Roxana Geoffrion, Nicole A. Koenig, Geoffrey W. Cundiff, Catherine Flood, Momoe T. Hyakutake, Jane Schulz and Erin A. Brennand. Methodology, formal analysis, writing (original draft, review and editing): Terry Lee and, Joel Singer.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Medical Education Research Grant, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, awarded to R. Geoffrion.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Geoffrey W. Cundiff received royalties as first author from Wolters Kluwer for TeLinde's Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery and had unpaid leadership roles as Past President and Board Member (American Urogynecologic Society), International Advisory Board Member, (International Urogynecologic Association). Geoffrey W. Cundiff, Catherine Flood and Roxana Geoffrion had unpaid leadership roles as Board Members (Canadian Society of Pelvic Medicine). All other authors have no relevant disclosures.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Approved by the Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board, H11‐00779 (2011‐06‐13 to 2024‐06‐23). Registered with clinicaltrials.gov NCT05887570 (2023‐05‐24).

Geoffrion R, Koenig NA, Cundiff GW, et al. Procedure‐specific simulation for vaginal surgery training: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103:1165‐1174. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14810

REFERENCES

- 1.Accessed May 26, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programresources/obgyncaseloginfo.pdf

- 2. Hall EF, Raker CA, Hampton BS. Variability in gynecologic case volume of obstetrician‐gynecologist residents graduating from 2009 to 2017. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:617.e1‐617.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banks E, Gressel G, George K, Woodland M. Resident and program director confidence in resident surgical preparedness in obstetrics and gynecologic training programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136:369‐376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guntupalli SR, Doo DW, Guy M, et al. Preparedness of obstetrics and gynecology residents for fellowship training. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:559‐568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Geoffrion R, Choi JW, Lentz GM. Training surgical residents: the current Canadian perspective. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:547‐559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Goff BA. A six‐year study of surgical teaching and skills evaluation for obstetric/gynecologic residents in porcine and inanimate surgical models. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:2056‐2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crouss T, Sharma S, Smith D, Hunter K, Perry R, Lipetskaia L. Vaginal hysterectomy rates before and after implementation of a multiple‐tier intervention. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:641‐647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sroka G, Feldman LS, Vassiliou MC, Kaneva PA, Fayez R, Fried GM. Fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery simulator training to proficiency improves laparoscopic performance in the operating room‐a randomized controlled trial. Am J Surg. 2010;199:115‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zendejas B, Cook DA, Bingener J, et al. Simulation‐based mastery learning improves patient outcomes in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2011;254:502‐511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geoffrion R, Suen MW, Koenig NA, et al. Teaching vaginal surgery to junior residents: initial validation of 3 novel procedure‐specific low‐fidelity models. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:157‐161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin JA, Regehr G, Reznick R, et al. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg. 1997;84:273‐278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Winckel CP, Reznick R, Cohen R, Taylor B. Reliability and construct validity of a structure technical skills assessment form. Am J Surg. 1994;167:423‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mandel LS, Goff BA, Lentz GM. Self‐assessment of resident surgical skills: is it feasible? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1817‐1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Goff BA, Nielsen PE, Lentz GM, et al. Surgical skills assessment: a blinded examination of obstetrics and gynecology residents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:613‐617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lentz GM, Mandel LS, Lee D, Gardella C, Melville J, Goff BA. Testing surgical skills of obstetric and gynecologic residents in a bench laboratory setting: validity and reliability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1462‐1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Geoffrion R, Lee T, Singer J. Validating a self‐confidence scale for surgical trainees. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2013;35:355‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Banks E, Pardanani S, King M, Chudnoff S, Damus K, Freda MC. A surgical skills laboratory improves residents' knowledge and performance of episiotomy repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1463‐1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ruple S, Forstein D, Barrow J. Where is the surgical education of obstetrics and gynecology residents headed? Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:46S. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galvin D, O'Reilly B, Greene R, O'Donoghue K, O'Sullivan O. A national survey of surgical training in gynaecology: 2014‐2021. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2023;288:135‐141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lababidi S, Winfrey OK, Shammout F. The impact of resident education on clinical outcomes in vaginal hysterectomies [3F]. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:62S‐63S. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balgobin S, Owens DM, Florian‐Rodriguez ME, Wai CY, McCord EH, Hamid CA. Vaginal hysterectomy suturing skills training model and curriculum. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:553‐558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dreyfus S. The five‐stage model of adult skill acquisition. Bull Sci Technol Soc. 2004;24:177‐181. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen X, Go M, Harzman A, et al. Operative coaching for general surgery residents: review of implementation requirements. J Am Coll Surg. 2022;235:361‐369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sachdeva AK. Preceptoring, proctoring, mentoring, and coaching in surgery. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124:711‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cutrer WB, Miller B, Pusic MV, et al. Fostering the development of master adaptive learners: a conceptual model to guide skill acquisition in Medical Education. Acad Med. 2017;92:70‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen XP, Williams RG, Smink DS. Dissecting attending Surgeons' operating room guidance: factors that affect guidance decision making. J Surg Educ. 2015;72:e137‐e144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robichaud M, Dugas MJ, Conway M. Gender differences in worry and associated cognitive‐behavioral variables. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:501‐516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmidt LA, Brook CA, Hassan R, MacGowan T, Poole KL, Jetha MK. iGen or shyGen? Generational differences in shyness. Psychol Sci. 2023;34:705‐713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Winer LK, Kader S, Abelson JS, et al. Disparities in the operative experience between female and male general surgery residents: a multi‐institutional study from the US ROPE consortium. Ann Surg. 2023;278:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]