Abstract

The relationship among gut microbiota, mitochondrial dysfunction/neuroinflammation, and diabetic neuropathic pain (DNP) has received increased attention. Ginger has antidiabetic and analgesic effects because of its anti-inflammatory property. We examined the effects of gingerols-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation on pain-associated behaviors, gut microbiome composition, and mitochondrial function and neuroinflammation of colon and spinal cord in DNP rats. Thirty-three male rats were randomly divided into 3 groups: control group, DNP group (high-fat diet plus single dose of streptozotocin at 35 mg/kg body weight, and GEG group (DNP+GEG at 0.75% in the diet for 8 weeks). Von Frey and open field tests were used to assess pain sensitivity and anxio-depressive behaviors, respectively. Colon and spinal cord were collected for gene expression analysis. 16S rRNA gene sequencing was done from cecal samples and microbiome data analysis was performed using QIIME 2. GEG supplementation mitigated mechanical hypersensitivity and anxio-depressive behavior in DNP animals. GEG supplementation suppressed the dynamin-related protein 1 protein expression (colon) and gene expression (spinal cord), astrocytic marker GFAP gene expression (colon and spinal cord), and tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression (colon, P < .05; spinal cord, P = .0974) in DNP rats. GEG supplementation increased microglia/macrophage marker CD11b gene expression in colon and spinal cord of DNP rats. GEG treatment increased abundance of Acinetobacter, Azospirillum, Colidextribacter, and Fournierella but decreased abundance of Muribaculum intestinale in cecal feces of rats. This study demonstrates that GEG supplementation decreased pain, anxio-depression, and neuroimmune cells, and improved the composition of gut microbiomes and mitochondrial function in rats with diabetic neuropathy.

Keywords: Ginger root extract, Gut microbiome, Mitochondria, Diabetic neuropathy, Neuroinflammation

1. Introduction

Chronic pain can be neuropathic or inflammatory. Neuropathic pain (NP) arises from damage to the nervous system, such as peripheral fibers or central neurons [1]. Chronic NP is a complex conditions with sensory and affective symptoms, including anxiety and depression. Among different types of NP, diabetic NP (DNP) is 1 of the most painful complications of type 2 diabetes (T2DM), involving progressive neuronal damage and dysfunction with decreased nerve conduction velocity, mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia, and cold allodynia [2].

Although the mechanisms of DNP are not entirely clear, a novel concept centered on oxidative stress as a potential causative factor of DNP has received great attention. Oxidative stress is caused by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant systems. Impaired glucose metabolism in T2DM, a critical mechanism to induce oxidative stress, causes shunting of excess glucose to other metabolic and nonmetabolic pathways that increase intracellular redox stress and abnormal modifications on proteins, lipids, and DNA of nerve cells [3]. Both hyperglycemia and associated production of ROS can increase pain induction (1) directly by facilitating pain signaling and activating sensory neurons (nociceptors) or (2) indirectly by damaging mitochondrial function or forming advanced glycation end products to enhance neuroinflammation [4]. Although DNP primarily affects the peripheral nervous system (PNS), the central nervous system (CNS) also plays an important role in the progression of DNP [5]. Thus, understanding the impact of oxidative stress on mitochondrial dysfunction and glial cell activation in the CNS could advance the management of DNP.

Accumulating evidence has revealed the capacity of gut microbiota to directly or indirectly regulate the functions of distant organs, such as PNS and CNS [6]. Gut microbiota have been shown to modulate the development and homeostasis of CNS through the “microbiota–gut–CNS axis” that generally refers to the interactions among microbiota, gut, and CNS through circulation of microbial metabolites/metabolic signaling pathways (indirectly) or through neural pathways such as vagus nerve transmission/gut hormones (directly) to regulate neurodevelopment, neurotransmitter release, and glial function in the CNS [7,8]. Such cross-talk seems to play an important role in neuropathic pain progression [9,10]. However, there is a knowledge gap with regard to pain and pain-associated anxio-depressive behaviors in animals with DNP [11]. Ma et al. recently reported that (1) continuous feeding of antibiotics to mice with streptozocin (STZ)-induced DNP blocked thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia, (2) gut microbiota depletion with antibiotics prevented STZ-induced glial cell activation in the spinal cord of mice, and (3) transplantation of fecal bacteria from normal mice to antibiotic-treated mice partially restored the gut microbiota and blocked DNP-associated pain behaviors, suggesting gut microbiota may play a key role in DNP development [8]. On the other hand, mitochondrial dysfunction (i.e., imbalance between mitochondrial fission and fusion, microglial overactivation, and astrocyte overaction) in both the PNS and the CNS plays a significant role in the etiology of DNP [12].

Ginger and its bioactive compounds have been shown to improve blood sugar regulation in T2DM animals [13,14]. Previously, we reported that (1) gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG; active bioactive compounds in ginger) supplementation into the diet decreased mechanical hypersensitivity of animals with spinal nerve ligation-induced NP and favorably modified their gut microbiome composition and function [15] and (2) GEG improved glucose tolerance and increased pancreatic insulin content in diabetic rats [16]. However, it is not known if GEG has beneficial effects on behaviors and the microbiota–gut–CNS axis in animals with DNP. Thus, this study was designed to address the effects of GEG on microbiota and mitochondrial function and neuroinflammation in gut (colon) and spinal cord (CNS) in animals with DNP. We hypothesized that GEG supplementation would reduce mechanical hypersensitivity and anxio-depressive behaviors in rats with DNP, and this effect would involve improvement of gut microbiome composition and mitochondrial function, as well as suppression of inflammation in the gut (colon) and CNS (spinal cord). We used a well-established T2DM rat model induced by high-fat diet (HFD) plus STZ injection that produces typical symptoms associated with DNP [17–19]. The HFD+STZ rats have significantly increased mechanical sensitivity at 21 days after STZ injection that lasts up to 120 days [20].

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Animals and treatments

Thirty-three male Sprague-Dawley rats (6–7 weeks old, 150–180 g body weight) were purchased from Envigo (Cumberland, VA) and housed individually under a 12-hour light-dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. All experiments were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee #19175).

After a 5-day acclimation, rats were randomly stratified by weight and assigned to 3 groups (n = 11/group): a control group in an AIN-93G diet, an HFD+STZ group (the DNP group), and an HFD+STZ+GEG (0.75% wt/wt GEG) group (the GEG group) for 8 weeks. The DNP model was induced by a single STZ dose (35 mg/kg body weight, intraperitoneally) after 2 weeks of an HFD. In the control group, the animals received vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]), instead of STZ. We started with n = 11 per group for this study. After 1 week of a single STZ dose, we measured 4-hour fasting blood glucose concentrations to confirm diabetic status in the STZ-treated groups (both DNP and GEG groups) and removed any rats (DNP [n = 2] and GEG [n = 3]) with fasting glucose concentrations <200 mg/dL (nondiabetic/nonrespondent) from the study. In addition, 1 rat in the GEG group died before sample collection. Therefore, there were n = 11, n = 9, and n = 7 in the control, DNP, and GEG groups, respectively, throughout the study period.

Throughout the study period, the animals in the DNP and GEG groups were fed an HFD consisting of 20%, 22%, and 58% of energy from carbohydrates, protein, and fat, respectively, and fat mainly from lard (catalog #D12492, Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ). Animals had free access to water and food during the study period. Based on the results of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, GEG consists of 18.7% 6-gingerol, 1.81% 8-gingerol, 2.86% 10-gingerol, 3.09% 6-shogoal, 0.39% 8-shogaol, and 0.41% 10-shogaol. The GEG used was a gift from Sabinsa Corporation, East Windsor, NJ. Body weight, food intake, and water consumption were recorded weekly.

At doses in the range of 100 mg/kg to 500 mg/kg, GEG has been shown to ameliorate diabetes complications in rats in various diabetic models [21–24]. In terms of GEG’s effects on pain-associated behaviors in spinal nerve ligation-induced NP rats, we showed that (1) GEG was antinociceptive and improved anxiety-like behaviors at 0.75% (wt/wt diet), corresponding to ~300 mg/kg body weight for rats [15] and (2) there was no GEG dose-response in pain sensitivity between 200, 400, and 600 mg GEG/kg body weight (unpublished data). Based on these studies [15,21–24], instead of a dose-response, a 0.75% (wt/wt in diet) single dose was tested in the HFD+STZ rats with NP. The dose of 0.75% wt/wt diet corresponds to ~300 mg/kg body weight for rat and ~90 g raw ginger for human daily consumption. Weekly body weight (Supplemental Figure S1) and weekly food intake (Supplemental Figure S2) are presented as supplemental data.

2.2. Assessment of mechanosensitivity

Mechanical withdrawal thresholds of spinal nocifensive reflexes were measured on the left paw using Electronic von Frey Aesthesiometer (IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, CA) with a plastic tip (catalog number 76–0488, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) in an exclusive testing area at baseline (before an HFD feeding and STZ injection) and the end of study (1 week before the sample collection) after respective treatments. The average of 6 measurements per subject, taken at least 30 seconds apart, was calculated.

2.3. Assessment of anxio-depressive behavior

Open field test (OFT) was used to measure exploratory behavior of the animal in an arena (70 cm × 70 cm) with acrylic walls (height, 45 cm) for 15 minutes, using a computerized video tracking and analysis system (EthoVisionXT 11 software, Noldus Information Technology). Duration and entries in the center area (35 cm × 35 cm) were calculated for the first 5 minutes [25]. Avoidance of the center area in the OFT suggests anxio-depressive behavior. Anxio-depressive behavior was assessed at baseline (before an HFD feeding and STZ injection) and the end of study (1 week before the sample collection) after respective treatments.

2.4. Sample collection

At the end of the experiment, animals fasted for 4 hours before sample collection. The animals were anesthetized with isoflurane before euthanization. The colon, spinal cord, and cecal feces were collected, immersed in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for later analysis. The colon tissues were also fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS, transferred to 30% sucrose with 1X PBS, and embedded in optimal cutting tempeature compound (OCT) for subsequent frozen sectioning and immunohistochemistry (IHC).

2.5. RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in colon and spinal cord

Total RNA was isolated from the colon (distal) and spinal cord (lower region) using the RNAzol RT (RN190, Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio, USA) and BAN ratio 1:200 (BN191, Molecular Research Center). Total RNA was quantified, reverse transcribed into cDNA, and target genes were amplified. Table 1 lists the genes tested, including DRP1 (mitochondria fission), MFN2 (mitochondria fusion), GFAP (critical role in astroglia activation), CD11b (control anti-inflammatory macrophage polarization through the activation of transcription factors such as Stat3), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α; inflammatory cytokine), and β-actin. All gene expressions were normalized to β-actin. Gene expression was calculated by the following formula: 2 − (ΔCT × 1000).

Table 1 –

List of primers for mRNA

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| DRP1 | 5’- ACA ACA GGA GAA GAA AAT GGA GTT G-3’ | 5’- AGA TGG ATT GGC TCA GGG CT-3’ |

| MFN2 | 5’- TCC TGA ACA ACC GCT GGG AT-3’ | 5’-GAT CCA CCA CGC CTA GCT CA-3’ |

| GFAP | 5’- AAT CTC ACA CAG GAC CTC GGC-3’ | 5’- AGC CAA GGT GGC TTC ATC CG-3’ |

| TNF-α | 5’-GAA CTC CAG GCG GTG TCT GT-3’ | 5’-CTG AGT GTG AGG GTC TGG GC-3’ |

| CD11b | 5’- TCC AAC CTG CTG AGG AAG CC-3’ | 5’- TCG ATC GTG TTG ATG CTA CCG-3’ |

| β-actin | 5’-ACA ACC TTC TTG CAG CTC CTC C-3’ | 5’-TGA CCC ATA CCC ACC ATC ACA-3’ |

Abbreviations: CD11b, cluster of differentiation molecule 11b; DRP1, dynamin related protein 1; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; MFN2, mitofusin 2; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha.

2.6. IHC for DRP1 and GFAP in the colon

The OCT-embedded colon tissues were sectioned using a Cryostat (ThermoFisher Shandon Cryotome E) (10 μm), and the sections were stored in 1X PBS at 4 °C before staining. Sections were washed in 1X PBS (3 times × 10 minutes) and then permeabilized for 10 minutes in 1X PBS containing 0.3% Triton-x. Sections were washed in 1X PBS (3 × 5 minutes), incubated with a blocking solution containing 10% goat serum in PBS for 1 hour, and washed in 1X PBS (3 × 5 minutes). PBS was removed from the wells and sections were incubated in primary antibody diluted in 1% goat serum in PBS 1X on a shaker at 4 °C overnight. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: DRP1 antibody (Novus Biologicals, NB110–55288 rabbit polyclonal, dilution 1:500) and GFAP antibody (Invitrogen, MA5–12023 mouse monoclonal, dilution 1:500) On the next day, sections were washed in PBS (3 × 5 minutes) and then incubated with secondary antibody (Invitrogen, Goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor Plus 594, A32740, dilution 1:2000 for DRP1; Invitrogen Goat antimouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor Plus 594, A32742, dilution 1:2000 for GFAP) for 1 hour in darkness. Sections were rinsed with 1X PBS (3 × 5 minutes), cover-slipped with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole mounting solution, and stored at 4 °C. Images of the sections were acquired using an Olympus Confocal Microscope (Fluoview FV2000) at 60×. Fluorescence mean intensity was quantified by selecting a specific region of interest for each cell using the FIJI software (ImageJ).

2.7. Gut microbiota profiling via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

Fecal DNA was isolated using PowerFecal DNA isolation kit (Qiagen Inc., Germantown, MD, USA). Amplicon sequencing of V4 variable region of the16S rRNA gene was performed by MR DNA (Molecular Research LP, Shallowater, TX, USA). Briefly, V4 variable region was amplified using polymerase chain reaction primers 515F/806R. Samples were multiplexed and pooled in equal proportions based on their molecular weight and DNA concentrations. Pooled samples were purified using calibrated Ampure XP beads, then used in Illumina DNA library preparation. Sequencing was performed at MR DNA (www.mrdnalab.com, Shallowater, TX, USA) on a MiSeq following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Raw sequencing data have been deposited under BioProject accession numbers PRJNA936631 in the National Center for Biotechnology Information BioProject database.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The data of behavioral outcomes and mRNA expression were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and analyzed by 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, followed by post hoc Fisher least significant difference test using GraphPad Prism software version 9.0. A significance of P < .05 applied to all statistical tests.

Microbiome data analysis: 16S rRNA gene sequencing data were analyzed using QIIME 2. Briefly, reads were filtered, denoised, and merged. Then, the DADA2 plugin (within QIIME 2) was used to determine the exact amplicon sequence variants. For the taxonomy assignment, Greengenes database version 13.8 was used. For redundancy analysis, we used Calypso software, which generated the redundancy analysis plot and measured the statistical significance of the group effect on microbial community composition. We used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn test for multiple comparisons. Results were regarded as significant when the P value < .05.

3. Results

3.1. GEG supplementation mitigated pain and anxio-depressive behaviors in DNP

The effects of GEG supplementation on DNP-associated behaviors were assessed using von Frey test (Fig. 1A) and OFT (Fig. 1B and C). There were no statistical differences in pain and anxio-depressive behaviors among the 3 different groups at the baseline (data not shown). At the end of study, (1) the DNP group had significantly greater sensitivity to mechanical stimuli than the control group; (2) GEG supplementation for 5 weeks significantly reduced pain sensitivity in DNP-treated animals, as shown by increased mechanical thresholds; and (3) the order of pain sensitivity was DNP group > GEG group > control group (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation reduced pain sensitivity (A) and anxio-depressive behaviors, as assessed in the open field test as time spent (duration) in the central area (B) and frequency of entering the central area (C). Bar histograms shown mean ± SEM. n =6–8 per group. Data were analyzed by a-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; LSD, least significant difference; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Regarding anxio-depressive behaviors, at the end of study, compared with the control group, the DNP group moved less frequently into the central area of the open field, and showed shorter durations once inside it (Fig. 1 B and C). Relative to the animals in the DNP group without GEG supplements, the addition of GEG to the diet significantly improved DNP-associated anxio-depressive behaviors, as shown by increased center duration and frequency at the end of study (Fig. 1 B and C).

3.2. GEG supplementation altered mRNA expression of mitochondrial fusion and fission markers

Effects of GEG supplementation on the mRNA expression of mitochondrial fusion marker, namely DRP1, was assessed on colon and spinal cord tissues (Fig. 2). Compared with the control group, the DNP group showed a significant increase in DRP1 mRNA expression in the colon (Fig. 2A) and an increased trend in the spinal cord (P = .0717) (Fig. 2B). Compared with the DNP group, the GEG group had decreased DNP1 mRNA expression in the spinal cord (P = .0172) (Fig. 2B). However, the difference in DRP1 mRNA expression between the DNP group and GEG group in the colon did not reach statistical significance (P = .120). The DNP group had higher DRP1 protein expression, measured with immunohistochemistry, in the colon than the control group, and the GEG group had significantly lower DRP1 protein expression than the DNP group (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation decreased gene expression of DRP1 in colon (A) and spinal cord (B) of rats. Quantification of DRP1 fluorescence intensity in colon tissue sections, pictures acquired at 60× (C). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 per group. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05, #.05 < P < .1. ANOVA, analysis of variance; DRP1, dynamin related protein 1; LSD, least significant difference; SEM, standard error of the mean.

We investigated the effects of GEG supplementation on mitochondrial fission (MFN2) gene expression in the colon and spinal cord of rats (Fig. 3). Compared with the control group, the DNP group had significantly greater MFN2 mRNA expression in both the colon (Fig. 3A) and spinal cord (Fig. 3B). GEG supplementation tended to suppress MFN2 mRNA expression in the spinal cord (P = .0544) (Fig. 3B), but GEG’s effect did not reach the degree of statistical significance for the colon (Fig. 3A) (P = .1728).

Fig. 3 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation had no effect on MFN2 gene expression in colon (A) but tended to suppress MFN2 in spinal cord (B) of rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 per group. were. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05, #.05 < P < .1. ANOVA, analysis of variance; LSD, least significant difference; MFN2, mitofusin 2; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.3. GEG supplementation suppressed mRNA expression of neuroinflammation markers in the colon and spinal cord

We evaluated the effects of GEG supplementation on GFAP gene expression, a marker of CNS astrocytes and enteric glia cells, in the colon and spinal cord of HFD+STZ–treated rats (Fig. 4). Relative to the control rats, the gene expression of GFAP was significantly higher in the colon (Fig. 4A) and spinal cord (Fig. 4B) of DNP rats (P < .05). GEG administration resulted in significantly lower GFAP gene expression in both tissues compared with untreated DNP rats. The IHC results of GFAP protein expression confirmed the findings for the GFAP mRNA gene expression in the colon of rats (P = .0413) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4–

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation lowered GFAP gene expression in colon (A) and spinal cord (B) of rats. Quantification of GFAP fluorescence intensity in colon tissue sections, pictures acquired at 60× (C). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 per group. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; LSD, least significant difference; SEM, standard error of the mean.

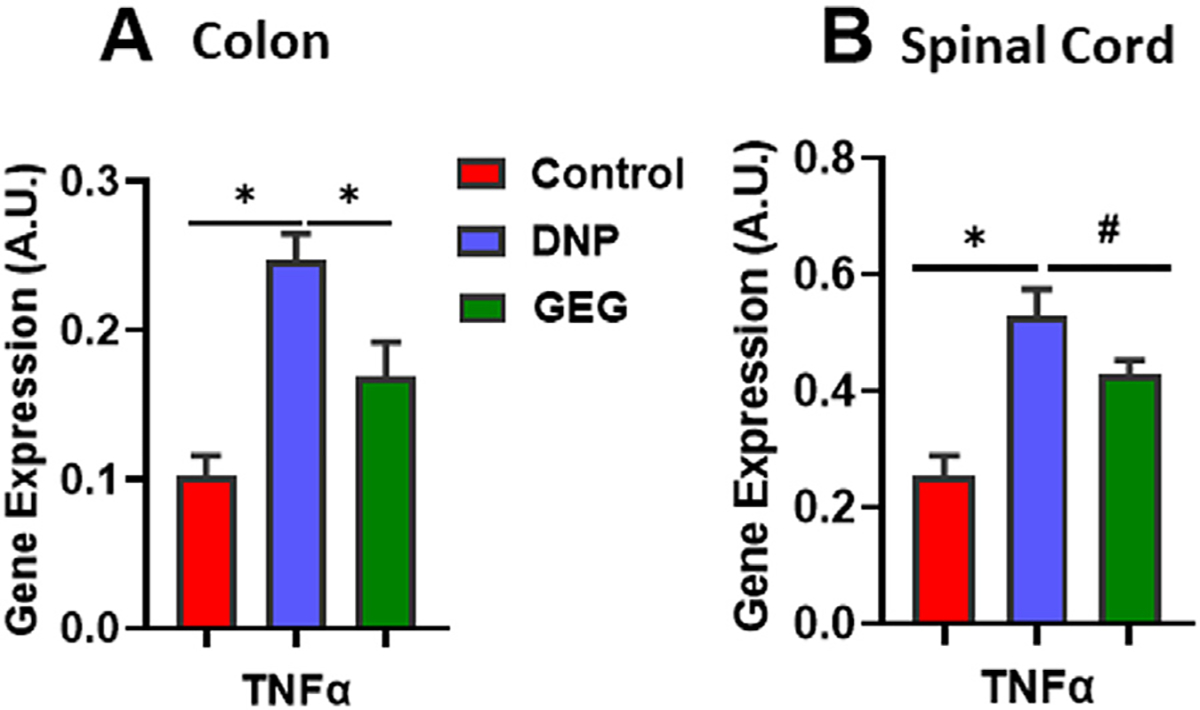

Figure 5 shows the effect of GEG supplementation on gene expression of TNF-α, pro-inflammatory cytokine, in the colon and spinal cord of DNP rats. DNP rats had significantly increased TNF-α gene expression in the colon (Fig. 5A) and spinal cord (Fig. 5B) compared with the control group. Supplementation of GEG led to decreased gene expression of TNF-α in the colon. GEG supplementation showed a trend toward decreased TNF-α mRNA expression in the spinal cord (P = .0974) (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation lowered TNF-α gene expression in colon (A) and spinal cord (B) of rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 6–8 per group. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05, #.05 < P < .1. ANOVA, analysis of variance; LSD, least significant difference; SEM, standard error of the mean; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-alpha.

Figure 6 presents the effect of GEG supplementation on gene expression of CD11b in the colon and spinal cord of DNP rats. Relative to the control group, the DNP group had significantly lower CD11b gene expression in both colon (Fig. 6A) and spinal cord (Fig. 6B). Supplementation of GEG into the diet significantly increased the CD11b mRNA expression in the colon (Fig. 6A) and spinal cord (Fig. 6B) of DNP rats.

Fig. 6 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation increased CD11b gene expression in colon (A) and spinal cord (B) of rats. Data are expressed as mean ±SEM. n = 6–8 per group. Data were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Fisher LSD tests, *P < .05. ANOVA, analysis of variance; CD11b, cluster of differentiation molecule 11b; LSD, least significant difference; SEM, standard error of the mean.

3.4. GEG supplementation favored gut microbiome composition

Microbiome richness refers to the number of species observed in a sample, whereas evenness describes the differences in the relative abundance of different species between samples. Relative to the DNP group, the GEG group showed an increase in microbiome evenness but not richness (Fig. 7). Then, we identified taxa of which relative abundance was altered by GEG supplementation. To achieve this, we used the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post hoc Dunn multiple comparison tests. Compared with the control group, the DNP group had decreased abundance of [Eubacterium] coprostanoligenes, Lachnospiraceae, Oscillospiraceae, and Peptococcaceae (Fig. 8). In contrast, the spinal nerve ligation group showed an increase in the abundance of Muribaculum intestinale compared with the control group (Fig. 8). GEG supplementation modified the composition of cecal microbiomes in DNP animals. For example, relative to the DNP group, the GEG group had an increased abundance of Acinetobacter, Azospirillum, Colidextribacter, and Fournierella, but a decrease of M intestinale in cecal feces (Fig. 8). We found that the abundance of E coprostanoligenes, Lachnospiraceae, Oscillospiraceae, and Peptococcaceae in the GEG group was below that of the control group, whereas the abundance of Acinetobacter, Azospirillum, Colidextribacter, and Fournierella in the GEG group was higher that in the control group (Fig. 8). Importantly, DNP increased the relative abundance of M intestinale, but this was reversed by GEG supplementation, which suggests its putative link to mechanical hypersensitivity.

Fig. 7 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation increased microbiome evenness but not richness. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn multiple comparison post hoc tests, * P < .05. n = 7 for control group, n = 9 for DNP group, and n = 7 for GEG group. DNP, diabetic neuropathic pain.

Fig. 8 –

Gingerol-enriched ginger (GEG) supplementation modified the composition of cecal microbiome. Data were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn multiple comparison post hoc tests, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. n = 7 for control group, n = 9 for DNP group, and n = 7 for GEG group. DNP, diabetic neuropathic pain.

4. Discussion

In the current study, the HFD+STZ model of DNP was successfully employed to examine the effects of GEG supplementation on pain and anxio-depressive behaviors. The present study shows for the first time that dietary GEG supplementation mitigates DNP-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and anxio-depressive behaviors. These outcomes may be a result of GEG’s impacts on mitochondrial function and neuroinflammation in the colon and spinal cord, as well as gut microbiota composition. The results of present study confirm our hypothesis and provide evidence for the beneficial behavioral effects of GEG supplementation through the alteration of the microbiota–gut–CNS axis.

Ginger and its bioactive compounds (i.e., Zingiber officinale Roscoe rhizome extract, 6-gingerol, GEG, and shogaol-enriched ginger) have been shown to decrease mechanical hypersensitivity in animals afflicted with surgically induced NP [15,26–29]. The current study corroborates a previous study using Boesenbergia rotunda (Chinese ginger) polyphenol extract to show beneficial effects of ginger bioactive compounds on pain behaviors in DNP rats [30]. Boesenbergia rotunda polyphenol extract (1) alleviated thermal hyperalgesia, as well as cold and mechanical allodynia, and (2) ameliorated problems with motor coordination in DNP rats because of its anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects [30]. Our previous work with GEG [15], confirmed in the present study, also detected inhibitory effects on mechanical hypersensitivity components in DNP, and expanded our understanding of the range of GEG effects by showing anxio-depression–like behavioral improvements on DNP. These positive responses of GEG on anxio-depression–like behaviors in the HFD+STZ–treated rats may be due to its ability to penetrate the blood–brain barrier via passive diffusion, consistent with GEG impacts on the CNS [31].

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a significant role in the etiology of DNP [12] through oxidative stress and alterations of the oxidative phosphorylation in both CNS and PNS [4,32,33]. Previous studies linked STZ-induced DNP in mice to shifted cellular calcium and mitochondrial dysfunction [34–36]. The STZ-induced DNP in mice led to (1) increased sensitivity to painful stimuli, (2) upregulated motor and sensory nerve conduction velocity deficits, and (3) mitochondrial bioenergetic dysfunction in spinal [34], dorsal root ganglion, and hippocampal neurons [36]. The present study validates that supplementation of GEG into the diet decreased mitochondrial dysfunction seen from DRP1 protein expression in the colon and DRP1 gene expression in the spinal cord. We noted that the GEG effects on DRP1 only appear at the protein expression as assessed by IHC but not at the gene expression as assessed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction PCR (P = .120) in colon tissues. Such discrepancy between the protein expression and gene expression in colon tissues could be due to sample size.

Fusion and fission are vital tasks that maintain mitochondrial function when cells experience metabolic or environmental stresses. Elevated fusion activity leads to mitochondrial elongation, whereas escalated fission results in mitochondrial fragmentation [37]. The components of the fusion/fission mechanisms can impact programmed cell death and lead to neuro-associated disorders, and disruptions in the fission/fusion process have been implicated in NP [38,39]. MFN2 predominately mediates fusion between outer mitochondrial membranes and has emerged as a crucial regulator of mitochondrial homeostasis (cellular energy and metabolism) in a neuropathy model in which enhanced mitochondrial fusion activity resulted in the formation of enlarged mitochondria and also impaired locomotor activity in Drosophila [39]. In the present study, the observation that DNP animals had enhanced MFN2 gene expression in both the colon and spinal cord of rats along with mechanical hypersensitivity suggests a critical role for MFN2 elevation in NP development. On the other hand, DRP1 (a mitochondrial fission marker) is essential to the segregation of damaged mitochondria for degradation of NP and has a role in mechanical hyperalgesia induced by pronociceptive mediators implicated in NP, including cytokines and growth factors [38]. Ferrari et al. demonstrated that (1) excessive oxidative stress/ROS-induced mitochondrial fragmentation (i.e., fission) and (2) increased DRP1 protein expression resulted in ROS-induced mechanical hyperalgesia through the upregulation of neuroinflammatory factors (i.e., TNF-α, glial-derived neurotrophic factor, and nitric oxide) in animals with NP [38]. Mitochondrial fission is upstream of caspase activation in the signaling pathway of apoptosis [40] and could perturb neuronal function through this signaling mechanism [41]. In the present study, the finding that DRP1 gene expression was upregulated in the colon of DNP rats with mechanical hypersensitivity is consistent with the involvement of DRP1 elevation in NP-induced hypersensitivity [38]. The present study provides evidence that GEG can benefit mitochondrial function in the DNP model as shown by reduced gene expression of DRP 1 (P < .05) and MFN2 (P = .0544) in the spinal cord.

There is evidence to suggest that microglial activation occurs at early stages of NP, whereas astrocyte activation begins at a relatively later stage of NP in the spinal cord [42–45]. The 8-week study period is considered as a later stage of NP, which may involve astrocyte rather than microglial activation [42–45]. A relationship has been established between astrocyte activation in spinal segments and pain hypersensitivity [42]. Astrocyte activation shown by overexpression of GFAP and the release of proinflammatory cytokines plays a crucial role in the development of NP [46]. Enhanced GFAP expression in the spinal cord has been reported consistently in the STZ-treated DNP rats [44,45]. Hypersensitivity is sustained by activated astrocytes that overexpress GFAP, nitric oxide, and several other cytokines (i.e., interleukin-1β and TNF-α) in a variety of chronic pain models [47,48], including DNP [49]. In the present study, HFD+STZ–treated rats had enhanced astrocyte activation, as shown by increased GFAP gene and protein expression in the colon and spinal cord, in combination with mechanical hypersensitivity, which is consistent with previous studies [44,45,50]. GEG supplementation into the diet significantly decreased the expression of GFAP in the colon and spinal cord of DNP rats, suggesting that blockage of astrocyte activation may be involved in the beneficial effects of GEG on pain-associated behaviors. Interestingly, GEG’s mitigation of GFAP expression was also observed in the glial-like cell types of colons of HFD+STZ rats. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate inhibitory effects of GEG on glial GFAP in the gut–CNS–axis as a mechanism of (DNP) pain inhibition.

CD11b is linked to beneficial functions of neuroimmune cells and is highly expressed on monocytes/macrophages, common dendritic cells, and microglia cells [51,52]. CD11b on macrophages could suppress toll-like receptor activation-induced inflammatory responses [53]. During the development of NP, the balance between pattern-recognition receptor-induced pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is critical for neuroinflammation homeostasis. Thus, the regulatory function of the CD11b-Src signal pathway on both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in neuroimmune cells is a potential target in NP treatment [53]. In the present study, the results that GEG supplementation significantly increased CD11b gene expression in both colon and spinal cord of DNP rats corroborate with a published study showing that 6-gingerol increased surface expression of neutrophil activation marker, CD11b, in primary human neutrophils [54].

Though the brain was not studied here, this study on the colon and spinal cord may point to a connective role between the gut and brain as a mechanism of NP-associated anxio-depression. Patients with chronic NP frequently suffer from symptoms of anxio-depression. Accumulating evidence suggests that gut microbiota may be involved with anxio-depression in both human [55,56] and animal models via the gut–microbiota–brain axis [57–59]. For example, fecal transplants from humans with major depressive disorder resulted in the development of depressive symptoms in a germ-free mouse model [55]. Treating rats with high-anxiety behavior with antibiotics altered gut microbiota while also alleviating anxiety behaviors [60,61]. Gut dysbiosis contributes to anhedonia susceptibility in surgically induced NP, and fecal microbiota transplantation from resilient rats into antibiotics-treated pseudo-germ-free mice exhibited fewer pain and depression-like phenotypes [62].

In the present study, the observation that GEG administration improved anxio-depressive behavior and reduced the abundance of M intestinale are consistent with a previous study showing M intestinale is 1 of the most important intestinal bacteria involved in the pathogenesis of anhedonia and depression [63]. Administration of Hypericum perforatum (an antidepressant herb) prevented anhedonia in mice along with the increased abundance of M intestinale [63]. Furthermore, M intestinale also seems to be a probiotic with anti-inflammatory properties. The ileal microbiome in mice with Crohn disease showed a prominent reduction of M intestinale [64]. Typical Western dietary patterns are associated with decreased abundance of M intestinale [65] and increased risk of depression [56,66]. However, it is not known whether (or how) M intestinale may contribute to diabetic neuropathy. This is an exciting area of research that requires further investigation. In the present study, we show that the GEG analgesia is associated with microbiome changes in DNP animals. However, we do not have direct evidence that the GEG analgesia is mediated through the microbiome. Further investigations are needed to evaluate this hypothesis.

In summary, this study suggests a prebiotic potential for dietary ginger root intake in the management of DNP with anxio-depressive behavior, possibly through beneficial effects on gut microbiota as well as mitochondrial function and neuroimmune cells of colon and spinal cord.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Jacob Lovett for editorial work.

Sources of Support

This work is supported by USDA-NIFA 2021-67017-34026 (C.L.S./V.N.), NIH grant R01NS038261 (V.N.), and Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, TX.

Abbreviations:

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CNS

central nervous system

- DNP

diabetic neuropathic pain

- GEG

gingerol-enriched ginger

- HFD

high-fat diet

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MFN2

mitochondrial fission

- NP

neuropathic pain

- OFT

open field test

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- STZ

streptozocin

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chwan-Li Shen: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rui Wang: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Julianna Maria Santos: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Moamen M. Elmassry: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Emily Stephens: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation. Nicole Kim: Data curation, Methodology. Volker Neugebauer: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2024.01.014.

REFERENCES

- [1].Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17002. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Heltianu C Role of nitric oxide synthase family in diabetic neuropathy. J Diabetes Metab 2011;S:5. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.S5-002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pang L, Lian X, Liu H, Zhang Y, Li Q, Cai Y, et al. Understanding diabetic neuropathy: focus on oxidative stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020;2020:9524635. doi: 10.1155/2020/9524635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ye D, Fairchild TJ, Vo L, Drummond PD. Painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: role of oxidative stress and central sensitisation. Diabet Med 2022;39:e14729. doi: 10.1111/dme.14729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Calcutt NA. Diabetic neuropathy and neuropathic pain: a (con)fusion of pathogenic mechanisms? Pain 2020;161(suppl 1):S65–86. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schroeder BO, Backhed F. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nat Med 2016;22:1079–89. doi: 10.1038/nm.4185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tremlett H, Bauer KC, Appel-Cresswell S, Finlay BB, Waubant E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: a review. Ann Neurol 2017;81:369–82. doi: 10.1002/ana.24901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ma P, Mo R, Liao H, Qiu C, Wu G, Yang C, et al. Gut microbiota depletion by antibiotics ameliorates somatic neuropathic pain induced by nerve injury, chemotherapy, and diabetes in mice. J Neuroinflammation 2022;19:169. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02523-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lin B, Wang Y, Zhang P, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Chen G. Gut microbiota regulates neuropathic pain: potential mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. J Headache Pain 2020;21:103. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01170-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen P, Wang C, Ren YN, Ye ZJ, Jiang C, Wu ZB. Alterations in the gut microbiota and metabolite profiles in the context of neuropathic pain. Mol Brain 2021;14:50. doi: 10.1186/s13041-021-00765-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yang Z, Li J, Gui X, Shi X, Bao Z, Han H, et al. Updated review of research on the gut microbiota and their relation to depression in animals and human beings. Mol Psychiatry 2020;25:2759–72. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-0729-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Areti A, Yerra VG, Komirishetty P, Kumar A. Potential therapeutic benefits of maintaining mitochondrial health in peripheral neuropathies. Curr Neuropharmacol 2016;14:593–609. doi: 10.2174/1570159x14666151126215358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Saravanan N, Patil MA, Kumar PU, Suryanarayana P, Reddy GB. Dietary ginger improves glucose dysregulation in a long-term high-fat high-fructose fed prediabetic rat model. Indian J Exp Biol 2017;55:142–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li Y, Tran VH, Kota BP, Nammi S, Duke CC, Roufogalis BD. Preventative effect of zingiber officinale on insulin resistance in a high-fat high-carbohydrate diet-fed rat model and its mechanism of action. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2014;115:209–15. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shen CL, Wang R, Ji G, Elmassry MM, Zabet-Moghaddam M, Vellers H, et al. Dietary supplementation of gingerols- and shogaols-enriched ginger root extract attenuate pain-associated behaviors while modulating gut microbiota and metabolites in rats with spinal nerve ligation. J Nutr Biochem 2022;100:108904. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2021.108904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang R, Santos JM, Dufour JM, Stephens ER, Miranda JM, Washburn RL, et al. Ginger root extract improves GI health in diabetic rats by improving intestinal integrity and mitochondrial function. Nutrients 2022;14:4384. doi: 10.3390/nu14204384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dang JK, Wu Y, Cao H, Meng B, Huang CC, Chen G, et al. Establishment of a rat model of type II diabetic neuropathic pain. Pain Med 2014;15:637–46. doi: 10.1111/pme.12387_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ahlawat A, Sharma S. A new promising simultaneous approach for attenuating type II diabetes mellitus induced neuropathic pain in rats: iNOS inhibition and neuroregeneration. Eur J Pharmacol 2018;818:419–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Holmes A, Coppey LJ, Davidson EP, Yorek MA. Rat models of diet-induced obesity and high fat/low dose streptozotocin type 2 diabetes: effect of reversal of high fat diet compared to treatment with enalapril or menhaden oil on glucose utilization and neuropathic endpoints. J Diabetes Res 2015;2015:307285. doi: 10.1155/2015/307285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Byrne FM, Cheetham S, Vickers S, Chapman V. Characterisation of pain responses in the high fat diet/streptozotocin model of diabetes and the analgesic effects of antidiabetic treatments. J Diabetes Res 2015;2015:752481. doi: 10.1155/2015/752481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li XH, McGrath KC, Nammi S, Heather AK, Roufogalis BD. Attenuation of liver pro-inflammatory responses by zingiber officinale via inhibition of NF-kappa B activation in high-fat diet-fed rats. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2012;110:238–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2011.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mansour DF, Abdallah HMI, Ibrahim BMM, Hegazy RR, Esmail RSE, LO Abdel-Salam. The carcinogenic agent diethylnitrosamine induces early oxidative stress, inflammation and proliferation in rat liver, stomach and colon: protective effect of ginger extract. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2019;20:2551–61. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.8.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Azizidoost S, Nazeri Z, Mohammadi A, Mohammadzadeh G, Cheraghzadeh M, Jafari A, et al. Effect of hydroalcoholic ginger extract on brain HMG-CoA reductase and CYP46A1 levels in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 2019;11:234–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marefati N, Abdi T, Beheshti F, Vafaee F, Mahmoudabady M, Hosseini M. Zingiber officinale (ginger) hydroalcoholic extract improved avoidance memory in rat model of streptozotocin-induced diabetes by regulating brain oxidative stress. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2021;43:15–26. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2021-0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ji G, Yakhnitsa V, Kiritoshi T, Presto P, Neugebauer V. Fear extinction learning ability predicts neuropathic pain behaviors and amygdala activity in male rats. Mol Pain 2018;14 1744806918804441. doi: 10.1177/1744806918804441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gauthier ML, Beaudry F, Vachon P. Intrathecal [6]-gingerol administration alleviates peripherally induced neuropathic pain in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1251–4. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mata-Bermudez A, Izquierdo T, de Los Monteros-Zuniga E, Coen A, Godinez-Chaparro B. Antiallodynic effect induced by [6]-gingerol in neuropathic rats is mediated by activation of the serotoninergic system and the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine triphosphate-sensitive K(+) channel pathway. Phytother Res 2018;32:2520–30. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Borgonetti V, Governa P, Biagi M, Pellati F, Galeotti N. Zingiber officinale roscoe rhizome extract alleviates neuropathic pain by inhibiting neuroinflammation in mice. Phytomedicine 2020;78:153307. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shen CL, Wang R, Yakhnitsa V, Santos JM, Watson C, Kiritoshi T, et al. Gingerol-enriched ginger supplementation mitigates neuropathic pain via mitigating intestinal permeability and neuroinflammation: gut-brain connection. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:912609. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.912609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wang P, Wen C, Olatunji OJ. Anti-Inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of boesenbergia rotunda polyphenol extract in diabetic peripheral neuropathic rats. J Pain Res 2022;15:779–88. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S359766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Simon A, Darcsi A, Kery A, Riethmuller E. Blood-brain barrier permeability study of ginger constituents. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2020;177:112820. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.112820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Duggett NA, Griffiths LA, McKenna OE, de Santis V, Yongsanguanchai N, Mokori EB, et al. Oxidative stress in the development, maintenance and resolution of paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy. Neuroscience 2016;333:13–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Khuankaew C, Sawaddiruk P, Surinkaew P, Chattipakorn N, Chattipakorn SC. Possible roles of mitochondrial dysfunction in neuropathy. Int J Neurosci 2021;131:1019–41. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1765777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Ma J, Pan P, Anyika M, Blagg BS, Dobrowsky RT. Modulating molecular chaperones improves mitochondrial bioenergetics and decreases the inflammatory transcriptome in diabetic sensory neurons. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015;6:1637–48. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Evans CG, Chang L, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock protein 70 (hsp70) as an emerging drug target. J Med Chem 2010;53:4585–602. doi: 10.1021/jm100054f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kahya MC, Naziroglu M, Ovey IS. Modulation of diabetes-induced oxidative stress, apoptosis, and Ca(2+) entry through TRPM2 and TRPV1 channels in dorsal root ganglion and hippocampus of diabetic rats by melatonin and selenium. Mol Neurobiol 2017;54:2345–60. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in mammals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2006;22:79–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ferrari LF, Chum A, Bogen O, Reichling DB, Levine JD. Role of Drp1, a key mitochondrial fission protein, in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 2011;31:11404–10. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2223-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ueda E, Ishihara N. Mitochondrial hyperfusion causes neuropathy in a fly model of CMT2A. EMBO Rep 2018;19:e46502. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Li J, Li Y, Qin D, von Harsdorf R, Li P. Mitochondrial fission leads to Smac/DIABLO release quenched by ARC. Apoptosis 2010;15:1187–96. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cheng C, Zochodne DW. Sensory neurons with activated caspase-3 survive long-term experimental diabetes. Diabetes 2003;52:2363–71. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.9.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Garrison CJ, Dougherty PM, Kajander KC, Carlton SM. Staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in lumbar spinal cord increases following a sciatic nerve constriction injury. Brain Res 1991;565:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91729-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li W, Li Y, Zhu S, Ji Q, Shu Y, Zhang L, et al. Rosuvastatin attenuated the existing morphine tolerance in rats with L5 spinal nerve transection through inhibiting activation of astrocytes and phosphorylation of ERK42/44. Neurosci Lett 2015;584:314–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang S, Wang Z, Li L, Zou L, Gong Y, Jia T, et al. P2Y12 shRNA treatment decreases SGC activation to relieve diabetic neuropathic pain in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats. J Cell Physiol 2018;233:9620–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhu D, Fan T, Chen Y, Huo X, Li Y, Liu D, et al. CXCR4/CX43 regulate diabetic neuropathic pain via intercellular interactions between activated neurons and dysfunctional astrocytes during late phase of diabetes in rats and the effects of antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022;2022:8547563. doi: 10.1155/2022/8547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Liu F, Yuan H. Role of glia in neuropathic pain. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2014;19:798–807. doi: 10.2741/4247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Ji RR, Kawasaki Y, Zhuang ZY, Wen YR, Decosterd I. Possible role of spinal astrocytes in maintaining chronic pain sensitization: review of current evidence with focus on bFGF/JNK pathway. Neuron Glia Biol 2006;2:259–69. doi: 10.1017/S1740925x07000403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tang J, Bair M, Descalzi G. Reactive astrocytes: critical players in the development of chronic pain. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:682056. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.682056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Tawfik MK, Helmy SA, Badran DI, Zaitone SA. Neuroprotective effect of duloxetine in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathy: role of glia suppressing mechanisms. Life Sci 2018;205:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Takeura N, Nakajima H, Watanabe S, Honjoh K, Takahashi A, Matsumine A. Role of macrophages and activated microglia in neuropathic pain associated with chronic progressive spinal cord compression. Sci Rep 2019;9:15656. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-52234-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kourtzelis I, Mitroulis I, von Renesse J, Hajishengallis G, Chavakis T. From leukocyte recruitment to resolution of inflammation: the cardinal role of integrins. J Leukocyte Biol 2017;102:677–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Paolillo M, Serra M, Schinelli S. Integrins in glioblastoma: still an attractive target? Pharmacol Res 2016;113:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yang M, Xu W, Wang Y, Jiang X, Li Y, Yang Y, et al. CD11b-activated Src signal attenuates neuroinflammatory pain by orchestrating inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in microglia. Mol Pain 2018;14 1744806918808150. doi: 10.1177/1744806918808150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Andersen G, Kahlenberg K, Krautwurst D, Somoza V. [6]-Gingerol facilitates CXCL8 secretion and ROS production in primary human neutrophils by targeting the TRPV1 channel. Mol Nutr Food Res 2023;67:e2200434. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.202200434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Zheng P, Zeng B, Zhou C, Liu M, Fang Z, Xu X, et al. Gut microbiome remodeling induces depressive-like behaviors through a pathway mediated by the host’s metabolism. Mol Psychiatry 2016;21:786–96. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Huang TT, Lai JB, Du YL, Xu Y, Ruan LM, Hu SH. Current understanding of gut microbiota in mood disorders: an update of human studies. Front Genet 2019;10:98. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Melancholic microbes: a link between gut microbiota and depression? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2013;25:713–19. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Evrensel A, Ceylan ME. The gut-brain axis: the missing link in depression. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2015;13:239–44. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2015.13.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lach G, Schellekens H, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Anxiety, depression, and the microbiome: a role for gut peptides. Neurotherapeutics 2018;15:36–59. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0585-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Schmidtner AK, Slattery DA, Glasner J, Hiergeist A, Gryksa K, Malik VA, et al. Minocycline alters behavior, microglia and the gut microbiome in a trait-anxiety-dependent manner. Transl Psychiatry 2019;9:223. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0556-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Husain MI, Chaudhry IB, Husain N, Khoso AB, Rahman RR, Hamirani MM, et al. Minocycline as an adjunct for treatment-resistant depressive symptoms: a pilot randomised placebo-controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol 2017;31:1166–75. doi: 10.1177/0269881117724352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Yang C, Fang X, Zhan G, Huang N, Li S, Bi J, et al. Key role of gut microbiota in anhedonia-like phenotype in rodents with neuropathic pain. Transl Psychiatry 2019;9:57. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0379-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhang Z, Yao C, Li M, Wang LC, Huang W, Chen QJ. Prophylactic effects of hyperforin on anhedonia-like phenotype in chronic restrain stress model: a role of gut microbiota. Lett Appl Microbiol 2022;75:1103–10. doi: 10.1111/lam.13710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Dobranowski PA, Tang C, Sauve JP, Menzies SC, Sly LM. Compositional changes to the ileal microbiome precede the onset of spontaneous ileitis in SHIP deficient mice. Gut Microbes 2019;10:578–98. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1560767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].McNamara MP, Singleton JM, Cadney MD, Ruegger PM, Borneman J, Garland T. Early-life effects of juvenile Western diet and exercise on adult gut microbiome composition in mice. J Exp Biol 2021;224(Pt 4). doi: 10.1242/jeb.239699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Lang UE, Beglinger C, Schweinfurth N, Walter M, Borgwardt S. Nutritional aspects of depression. Cell Physiol Biochem 2015;37:1029–43. doi: 10.1159/000430229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.