Abstract

Introduction:

Guided by Opara et al.’s (2022), Integrated Model of the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide and Intersectionality Theory, the current study examined contextual stressors experienced disparately by Black youth (racial discrimination, poverty, and community violence) as moderators of the association between individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and hopelessness) and active suicidal ideation.

Method:

Participants were 457 Black adolescent boys (mean age = 15.31, SD = 1.26) who completed self-report surveys.

Results:

As predicted, the association between perceived burdensomeness and active suicidal ideation was significantly moderated by economic stress. In addition, the association between peer belongingness and suicidal ideation was significantly moderated by racial discrimination, but there were no moderating effects for school belongingness. Finally, the association between hopelessness and suicidal ideation was significantly moderated by both racial discrimination and witnessing community violence.

Conclusion:

These findings highlight the need for research, interventions, and policy work devoted to using integrated approaches of individual and socioeconomically relevant patterns of suicidal thoughts and behaviors to support Black youth exposed to various forms of structural oppression.

Keywords: Black youth, interpersonal theory of suicide, intersectionality

INTRODUCTION

Youth suicide is the second leading cause of death and the fourth leading cause of years of potential life lost for adolescents in the United States (Fortgang & Nock, 2021; Goldstein et al., 2022; Kegler et al., 2022). From 2003 to 2017, the rate of suicide attempts for Black youth increased by 73% (Lindsey et al., 2019), with Black youth ages 15 to 17 experiencing the largest annual increase (Sheftall et al., 2022). The alarming increase in suicide rates of Black youth comes at a time when rates of suicide attempts have decreased among youth from other racial/ethnic groups (Lindsey et al., 2019). Although rates are rising for both Black boys and girls, Black boys seem to be particularly vulnerable, as research examining longitudinal trends of suicidal behavior among Black youth have found significant increases in injury by attempt for Black boys and higher proportions of suicide deaths by firearm use for Black boys compared to Black girls, suggesting that Black boys are more likely to engage in more lethal methods of suicide that increase likelihood of death (Ali et al., 2021; Lindsey et al., 2019; Ruch et al., 2019; Sheftall et al., 2022). Indeed, Black boys showed a 60% increase in suicide between 2001 and 2017 (Price & Khubchandani, 2019), as well as a 122% increase in injury by suicide attempts between 1991 and 2017 (Lindsey et al., 2019). The most alarming statistic is that Black boys accounted for over 70% of Black youth suicide deaths between 2001 and 2017 (Bridge et al., 2018; Sheftall et al., 2022). However, when comparing the profiles Black boys and Black girls who died from suicide, Black boys were significantly less likely than girls to report mental health problems, especially depression, or mental health treatment, suggesting an urgent need to understand suicidal thoughts and behaviors among Black boys. As such, the current study examined associative patterns between individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors and active suicidal ideation among Black male adolescents and investigated the moderating role of socio-cultural risk factors.

Most research on suicide focuses on fatal and nonfatal suicidal behavior; however, suicidal ideation is approximately seven times more prevalent than suicidal behavior (Jobes & Joiner, 2019) and increases the risk for later suicide attempts (Large et al., 2021; McHugh et al., 2019; Rossom et al., 2017). Suicidal ideation includes cognitions such as thinking about or considering suicide and is distinguished from fatal and nonfatal suicidal behaviors (Crosby et al., 2011; Klonsky et al., 2016). Compared to other age groups, adolescents show the highest prevalence of suicidal ideation (Evans et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2015), with rates ranging from 20% to 30% (Evans et al., 2005; Georgiades et al., 2019; Nock et al., 2013; Orri et al., 2020).

Regarding rates of suicidal ideation by race, temporal trends among US adolescents from 1991 through 2019 revealed that Black male youth had the greatest increase in the prevalence of nonfatal suicide attempts compared to Black female, non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian, American Indian/Alaska Native, and their interactions sex × race/ethnicity (APC = 0.7%, 95% CI, −0.5 to 2.0%) but had nonsignificant changes in suicidal ideation compared to these other groups (APC = −0.3%, 95% CI, −2.1% to 1.4%; Xiao et al., 2021). Importantly, compared to White or Non-Black Latinx youth, Black youth tend to have lower prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation, but have the highest prevalence estimates of suicidal attempts compared to their peers (Ivey-Stephenson et al., 2020). Contrary to what is known about other adolescents, only 50% of Black adolescents who have attempted suicide had a diagnosed psychiatric disorder before the attempt (Joe et al., 2009). Importantly, Black youth may choose not to disclose suicidal thoughts and behaviors or seek social and mental health support due to stigmas surrounding mental health in their communities and fear of receiving disciplinary action from biased authority figures, such as police officers, school administrators, or their teachers (Akouri-Shan et al., 2022; Talley et al., 2021).

The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide

Understanding motivating factors for youth suicidal ideation and suicide-related behaviors is essential for addressing and preventing youth deaths by suicide. One widely used theoretical framework of motivational factors is Joiner’s (2005) Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS), which posits that motives for suicidal thoughts and behaviors derive from two interpersonal factors: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Thwarted belongingness describes an emotional state in which the fundamental human need for social connectedness is unmet due to a lack of social interaction and support (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Van Orden et al., 2012), leading to feelings of being emotionally disregarded and beliefs that one is alone (Joiner, 2005). Perceived burdensomeness is the belief that one’s life is a burden or liability to others (e.g., family and friends; Van Orden et al., 2010) and illustrates one’s belief that others would be better off without them (Joiner, 2005). It is proposed that the simultaneous presence of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are most likely to result in an increased potential for active suicidal ideation when an individual also feels a sense of hopelessness about the pervasiveness of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Van Orden et al., 2010). In general, feelings of hopelessness involve having negative or low expectations for the future or lack of hope that life will improve, but for the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, feelings of hopelessness are specific to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) can aid in explaining suicidal ideation among Black boys. However, the interpersonal risk for suicidal ideation among Black boys may be exacerbated by their unique contextual and cultural experiences in society (Musci et al., 2016; Robinson et al., 2022; Talley et al., 2021).

Toward a more culturally and contextually relevant model of suicidal thoughts and behaviors

Given that Black youth have an increased likelihood of experiencing racial, economic, social, and community oppression compared to their White and Latino peers (Child Trends, 2019; Gibson et al., 2022; Kelly & Varghese, 2018), it is pivotal to investigate the contributing impact of these systems on suicidal thoughts and behaviors among this population. A recently proposed theoretical model of suicidal thoughts and behaviors for Black youth integrates the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005) with tenets of Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw, 1991) to highlight the social, economic, and cultural factors that can contribute to links between individual motivating factors for suicide and suicidal ideation and behaviors among Black youth (Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020). Intersectionality theory describes how multiple systems of oppression can produce undesirable outcomes (Carastathis, 2014; Crenshaw, 1991). Indeed, a growing body of research has established that, as minoritized youth, Black adolescents must navigate multiple sources of structural oppression and power structures (Cooper et al., 2022; Del Toro et al., 2022; Standley & Foster-Fishman, 2021). By integrating Intersectionality Theory (Crenshaw, 1991) and the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005), the resulting integrated model (Opara, Assan, et al., 2020) conceptualizes that individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors are experienced by Black youth within a broader system of contextual stressors, and these contextual stressors may exacerbate the impact of individual motivating factors. In Opara’s article, the authors note that Black youth’s feelings of hopelessness, thwarted belongingness, or perceived burdensomeness can be amplified by factors in their immediate environments (e.g., poverty, trauma, sexism, or racism) or community risk factors (e.g., exposure to community violence, excessive punishment within school, and substance use exposure). In other words, socioecological factors may moderate the association between individual factors and suicidal ideation. Specifically, individual factors may be most strongly associated with suicidal ideation when socioecological risk factors in adolescents’ immediate environment are high. The model denotes specific systems that fit into the integrated framework based on socio-ecological conceptualizations of health factors. These systems include individual, immediate environment, community, and culture/society. Examples of Individual factors include hopelessness, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, family, peer group, and mental health. Immediate environment includes family support, peer groups, and exposure to discrimination and racism. Community includes exposure to violence, gang activity, drug usage, poverty, and exposure to discrimination and racism. Finally, Culture and Society includes racism, sexism, classism, and sexual orientation. The integrated model provides a roadmap for moving beyond individual factors to exploring how socio-cultural vulnerability factors (e.g., racial discrimination, poverty, and community violence) can exacerbate the influence of individual motivating factors (belongingness, burdensomeness, and hopelessness) on active suicidal ideation (Hjelmeland & Knizek, 2020). Racial discrimination, defined as poor and unfair treatment because one’s race, is an underlying factor in racial health disparities for Black youth (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Up to 90% of Black American youth experience racial discrimination (Pachter et al., 2018; Seaton et al., 2008), and it is associated with negative affect (e.g., Cheeks et al., 2020), major depression and anxiety (Pachter et al., 2018) and higher odds of suicidal ideation in Black adolescents (Assari et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2017). Racial discrimination can function as a way to exclude others and can be associated with feelings of “otherness” by those who experience it (Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020). The resulting lack of social connectedness and social support may exacerbate existing feelings of thwarted belongingness among Black youth and strengthen the relationship between thwarted belongingness and active suicidal ideation.

Economic stress refers to not having access to resources to meet basic needs or having caregivers with incomes at the lower end of income distribution (Ponnet et al., 2014). Due to structural inequalities, Black youth are disproportionately represented among households classified as low socioeconomic and are more likely to experience neighborhood disinvestment and poverty, compared to other ethnoracial groups (Murry et al., 2018). Approximately 63% of Black youth in the U.S live in families that are classified as economically disadvantaged (Hostinar & Miller, 2019). Consequently, Black youth are more likely to experience the stress of severe economic and material hardship within their household (Conger et al., 2002). The integrated model proposes that perceived burdensomeness may be associated with these experiences of poverty and material hardship as Black youth may perceive themselves as a contributor to their family’s economic stress (Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020). As such, economic stress may heighten associations between perceived burdensomeness and active suicidal ideation.

Community violence is defined as witnessing or being the direct victim of acts of violence in public areas intended to cause physical harm against persons within one’s shared community (Cooley-Strickland et al., 2009; Finigan-Carr & Sharpe, 2022; Kennedy & Ceballo, 2014). While community violence exposure predicts higher levels of suicidal ideation across various populations (e.g., Castellví et al., 2017; Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019; Pastore et al., 1996; Voisin, 2007), there is limited research regarding the direct relationship between community violence and suicidal ideation for Black youth in particular. This is surprising given that community violence exposure disproportionately affects Black youth compared to other youth (Chen, 2010; Elsaesser & Voisin, 2015; Lambert et al., 2012; Outland, 2021), and there are links between community violence exposure and hopelessness among youth of color (Bolland et al., 2001; Burnside et al., 2018; Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020). Given the uncontrollable and chronic nature of community violence exposure, and risk for injury or death, adolescents exposed to violence may be less able to perceive a future for themselves (Stoddard et al., 2011), which may heighten the risk for active suicidal ideation.

The current study

Using the Integrated Model of Interpersonal-Psychological Theory and Intersectionality Theory (Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020) as a framework, the current study examined associative patterns between individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, hopelessness) and active suicide ideation among Black male adolescents, and investigate the moderating role of socio-cultural risk factors (exposure to community violence, racial discrimination, and poverty). Adolescence represents a critical developmental period to assess the patterns of suicidal ideation, as the prevalence of ideation is higher during adolescence compared to other developmental periods (e.g., Evans et al., 2005; Nock et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2015). In addition, experiences of discrimination and community violence exposure increase during adolescence (Benner et al., 2018; Fowler et al., 2009), particularly for Black boys. The current study hypothesized that racial discrimination would moderate the relationship between thwarted belongingness and active suicidal ideation, poverty would moderate the relationship between perceived burdensomeness and active suicidal ideation, and community violence exposure would moderate the relationship between hopelessness and active suicidal ideation among Black youth.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were part of a larger study designed to identify the individual, school, peer, family, and community factors that predict academic functioning and social–emotional behavior in African American male high school students. Participants were 9th through 11th grade students from three campuses of an all-boys charter school system in disinvested (Economically Disconnected Areas, EDAs; Zaimi, 2022), urban communities of a large Midwestern city. At the time of data collection, 99.5% of the students in the school system were African American students, and 86% of the students were eligible for free/reduced school lunch. A total of 568 boys participated in the larger study, and the current sample included 451 boys with complete data on the study variables for the current study (mean age = 15.31, SD = 1.26). Ninth grade students comprised 54% of the sample, tenth grade students comprised 23%, and eleventh grade comprised 23%. Approximately 43% resided with their mother and father, 46% resided with their mother only, 3% resided with their father only, and the remaining 8% resided with other relatives (e.g., grandparent). There were no differences between excluded subjects (n = 110) and subjects included in current analyses (n = 457) on participant age or grade, or family structure, with the exception of excluded boys being more likely to live with dad only than included boys.

Procedure

The current study was granted ethical approval by a university-based institutional review board (IRB). Researchers visited the selected schools and met with staff to introduce the project and describe the procedures. A recruitment letter and consent/assent form were sent home with all ninth- through eleventh-grade students. Active parental consent and youth assent were obtained for all study participants. Parents provided written consent at home and returned the signed consent form to school with students. The recruitment letter and consent form included contact information for the primary investigator and encouraged parents to contact the primary investigator if they had any questions prior to signing. Student participants provided written assent at the beginning of data collection with research assistants. The participation rate for the study was approximately 59%. Youth completed a packet of questionnaires in a classroom setting. At least two (2) research assistants were available to administer the surveys and monitor the progress of participants. Each participant received a movie pass as compensation. Research assistants also reviewed all suicide screening measures in real-time to ensure any youth at high risk were appropriately assessed for safety and linked to therapeutic resources.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic information was collected, including race/ethnicity, grade, participant employment status, primary caretaker, and parental college attendance (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Sample.

| Demographics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black or African American | 438 | 99% |

| Biracial | 6 | 1% |

|

| ||

| Grade | ||

| Nineth | 245 | 54% |

| Tenth | 103 | 23% |

| Eleventh | 103 | 23% |

|

| ||

| Employment Statusa | 119 | 26% |

|

| ||

| Primary Caretaker | ||

| Mother and Father | 196 | 43% |

| Mother only | 209 | 46% |

| Father only | 12 | 3% |

| Other | 40 | 8% |

|

| ||

| Parental College Attendancea | 427 | 93% |

Note: N = 457. Participants were on average 15.31 years old (SD = 1.26).

Reflects the number and percentage of participants answering “yes” to this question.

Predictors

Perceived Burdensomeness was assessed using items from the Suicidal ideation Questionnaire, Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1988). This 15-item self-report questionnaire assesses the frequency of suicidal thoughts over the past month on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “I never had this thought,” “I had this thought before, but not in the past month,” “About once a month,” “Couple of times a month,” “About once a week,” “Couple of times a week,” and “Almost every day.” Three items within the scale are used to assess perceived burdensomeness (“I thought it would be better if I was not alive,” “I thought that others would be happier if I was dead,” and “I thought no one cared if I lived or died”). The mean score of these three items was used in the current study. The SIQ-Jr has demonstrated reliability and validity when administered within schools to Black youth (Mazza & Reynolds, 1999). The Cronbach’s alpha for the three items measuring perceived burdensomeness for the current sample was 0.89. Further, a study by Storch et al. (2015), utilized these three items to classify youth exhibiting clinically significant active suicidal ideation, such as in the current study. Good psychometric properties have been established for the use of these SIQ-JR items as a measure of active suicidal ideation (King et al., 2014).

Hopelessness.

Youth’s attitude and beliefs about their outlook on the future and feelings of hopelessness about the future were assessed using the Future Orientation Scale (FOS; Whitaker et al., 2000). The FOS includes 7 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “disagree a lot” to “agree a lot,” that ask about perceptions of perceived control (e.g., I have little control over the things that happen to me), positive future outlook (e.g., What happens to my future mostly depends on me), and hopelessness (e.g., Sometimes I feel there is nothing to look forward to in the future) within the last 6 months. The internal consistency for the current sample was 0.92.

Belongingness.

Peer belongingness was assessed using the peer support subscale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987). The IPPA is a self-report measure used to assess the strength of the relationship between youth and their parents, and youth and their friends. This 75-item scale is fragmented into three subscales that measure maternal, paternal, and peer support. The peer support subscale included 25 items (e.g., “I feel my friends are good friends”) rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “almost never or never true” to “almost always or always true” now. The internal consistency for the peer support subscale for the current sample was 0.93. The peer belongingness variable was reverse coded in the current analysis to represent lack of belonging or thwarted belongingness.

School Belongingness was assessed using the Psychological Sense of School Membership Scale (PSSMS; Goodenow, 1993). This 18-item measure assesses students’ current general and specific aspects of thoughts and feelings toward school, including asking what each student thinks about classes, teachers, other students, and overall sense of belongingness in the school environment. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “not at all true” to 5 “completely true.” The study variable was calculated from a mean score of the items. Initial tests of construct reliability were strong (Goodenow, 1993), and internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable (α = 0.73). The school belongingness variable was reverse coded in the current analysis to represent lack of belonging or thwarted belongingness.

Moderators

Racial Discrimination and Financial Stress.

Participants’ experiences of racial discrimination were assessed using the 6-item discrimination stress subscale items from the Multicultural Events Schedule for Adolescents (MESA; Gonzales et al., 1995). The MESA is an 82-item self-report measure of stress for adolescents living in urban communities in the past 3 months. The items are grouped into eight stress categories. The 6-item perceived discrimination subscale (“You were unfairly accused of doing something bad because of your race or ethnicity”) was used to determine racial discrimination. Participants’ experiences of economic stress were assessed using the 11-item economic stress subscale items (“Your parent(s) talked about having serious money problems”). The MESA items were generated by ethnically diverse youth from urban communities (Gonzales et al., 1995). In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the racial discrimination subscale was 0.67 and the economic stress subscale was 0.75.

Given the internal consistency estimate of the racial discrimination measure, An EFA, using principal components analysis as an extraction method, was conducted to explore the underlying factor structure of the six items on the discrimination measure. The fit of the factor model was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The overall KMO was 0.769, and Barlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2(15) = 341.81, p < 0.001. The scree test gave a one-factor solution that accounted for 38.77% of the variance. Inspection of the component matrix indicated that all six variables had factor loadings that ranged from 0.57 to 0.67 and exceeded recommended value of 0.32 for individual items in exploratory factor analysis, which equates to approximately 10% overlapping variance with the other items in that factor (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001). Further, recommendations also indicate that five or more strongly loading items (0.50 or better) are desirable and indicate a solid factor (Costello & Osborne, 2019).

Community Violence Exposure.

Lifetime exposure to community violence was assessed with the My Exposure to Violence Scale (MEV; Selner-O’Hagan et al., 1998). The MEV assesses a participant’s exposure to 18 different violent events. Of the 18 items, eight items assessed direct victimization (e.g., “Been attacked with a weapon”) and 10 items assessed witnessing violence (e.g., “Witnessed a shooting”). Frequency of exposure was measured on a 6-point scale from “never” to “more than 50 times.” The internal consistency estimates for the victimization and witnessing subscales, as determined by Cronbach’s alpha were 0.71 and 0.89, respectively.

Outcomes

Active Suicidal Ideation.

Active suicidal ideation was assessed using active suicide ideation items of the Suicidal ideation Questionnaire, Junior (SIQ-JR; Reynolds, 1988). This 15-item self-report questionnaire assesses the occurrence of suicidal thoughts over the past month on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “I never had this thought” to “Almost every day.” Three items that evaluate active suicidal thoughts (e.g., “I thought about killing myself,” “I thought about how I would kill myself” and “I thought about when I would kill myself”) were utilized in the current analyses. The SIQ-Jr has demonstrated reliability and validity when administered to Black youth as determined by an internal consistency reliablity coefficient of r = 0.91 and test–retest reliability coefficient of 0.89 (Mazza & Reynolds, 1999). The internal consistency for the three items measuring active suicidal thoughts within the current sample, determined by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.94 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Frequencies of Scores for Active Ideation, (N = 457).

| Scores | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 356 | 78% |

| 0.33 | 23 | 5% |

| 0.67 | 15 | 3% |

| 1.00 | 23 | 5% |

| 1.33 | 6 | 1% |

| 1.50 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 1.67 | 3 | 0.7% |

| 2.00 | 6 | 1% |

| 2.33 | 3 | 0.7% |

| 2.50 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 2.67 | 2 | 0.4% |

| 3.00 | 4 | 0.9% |

| 3.33 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 3.67 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 4.00 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 4.33 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 5.00 | 5 | 1% |

| 5.33 | 1 | 0.2% |

| 5.67 | 2 | 0.4% |

| 6.00 | 2 | 0.4% |

DATA ANALYSIS

Preliminary analyses were conducted using Pearson correlations to assess for associations among study variables. PROCESS version 4.1 bootstrapping procedure for SPSS (n = 10,000 bootstrap samples; Hayes, 2022) was used to examine conditional main effects models, in which individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, hopelessness) interacted with socio-cultural risk factors (racial discrimination, economic stress, and exposure to community violence) to predict active suicidal ideation. Bootstrapping is a nonparametric approach to statistical inference that uses variability within a sample to estimate the sampling distribution (Hayes, 2022). Specifically, bootstrapping is a type of resampling where several smaller, equal-sized samples are repeatedly drawn, with replacement, from a single original sample, and the resulting bootstrap statistics are compiled into a bootstrap distribution (Efron & Tibshirani, 1994). If a two-way interaction was present, it was probed with the Johnson-Neyman technique (Hayes, 2013) to determine where the interaction between predictor and outcome variable is significant along the distribution of the moderator. The Johnson-Neyman technique provides a continuous range of values, rather than arbitrary points (i.e., mean ± 1SD; Hayes, 2009).

RESULTS

Descriptive analyses

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for the study variables are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Pearson Correlations among the Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Active Ideation | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Burdensomeness | 0.672b | 1 | |||||||

| 3. School Belongingness | −0.182b | −0.111a | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Peer Belongingness | −0.078 | −0.033 | 0.293b | 1 | |||||

| 5. Hopelessness | 0.188b | 0.112a | −0.183b | −0.282b | 1 | ||||

| 6. Economic Hassles | 0.193b | 0.215b | −0.054 | −0.012 | 0.104a | 1 | |||

| 7. Racial Discrimination | 0.097a | 0.079 | −0.078 | −0.053 | 0.044 | 0.469b | 1 | ||

| 8. Witnessing | 0.186b | 0.221b | −0.074 | 0.003 | 0.041 | 0.243b | 0.297b | 1 | |

| 9. Victimization | 0.244b | 0.282b | −0.117a | −0.103a | 0.096a | 0.239b | 0.278b | 0.695b | 1 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.98) | 0.44 (1.16) | 3.42 (0.51) | 98.81 (18.17) | 1.77 (0.48) | 11.11 (1.81) | 7.16 (1.46) | 1.42 (0.97) | 0.61 (0.64) |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Moderating analyses

Moderator: Economic stress

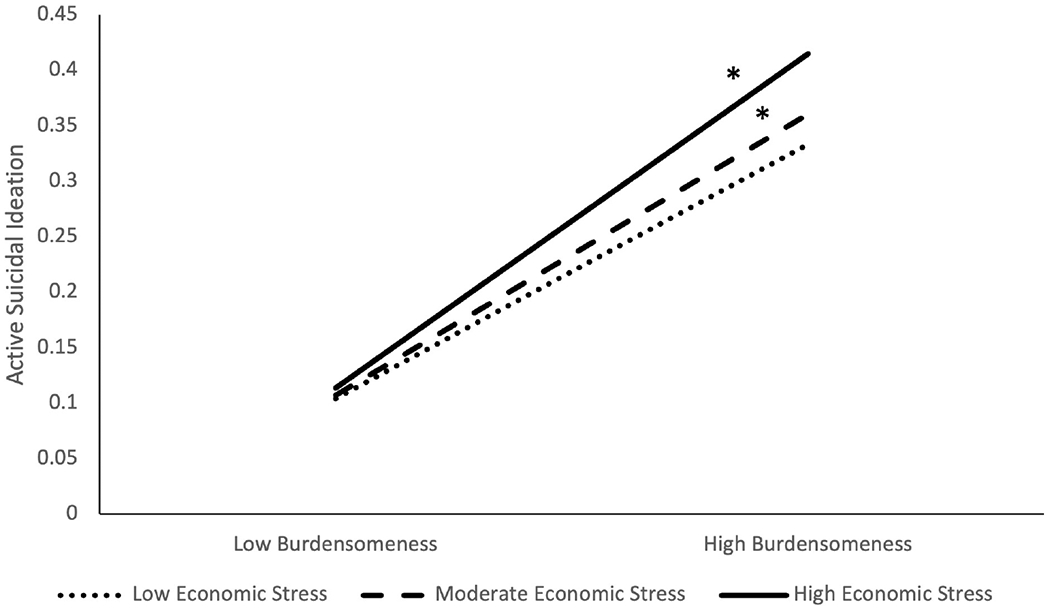

One model examined economic stress as the moderator of the association between burdensomeness and suicidal ideation. Results of the model revealed a significant interaction between burdensomeness and economic stress in the prediction of active suicidal ideation (B = 0.05, SE = 0.01, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.02, 0.08]). To understand the significant interaction effect, the Johnson-Neyman Technique was utilized to identify points along a continuous moderator where the relation between the independent variable and the outcome variable transition between being statistically significant to nonsignificant. The Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that the significance region for the interaction between burdensomeness and economic stress was defined at moderate and high levels of economic stress, such that the positive association between burdensomeness and active ideation was significant at values of economic stress −5.37 and larger (95% CI [0.05, 0.46]), but not for values less than −5.37. Specifically, burdensomeness significantly predicted higher levels of active ideation at moderate and high levels of economic stress, but not at low levels of economic stress (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conditional Effect of Burdensomeness on Active Suicidal Ideation as a Function of Economic Stress. Asterisks denote statistically significant slopes.

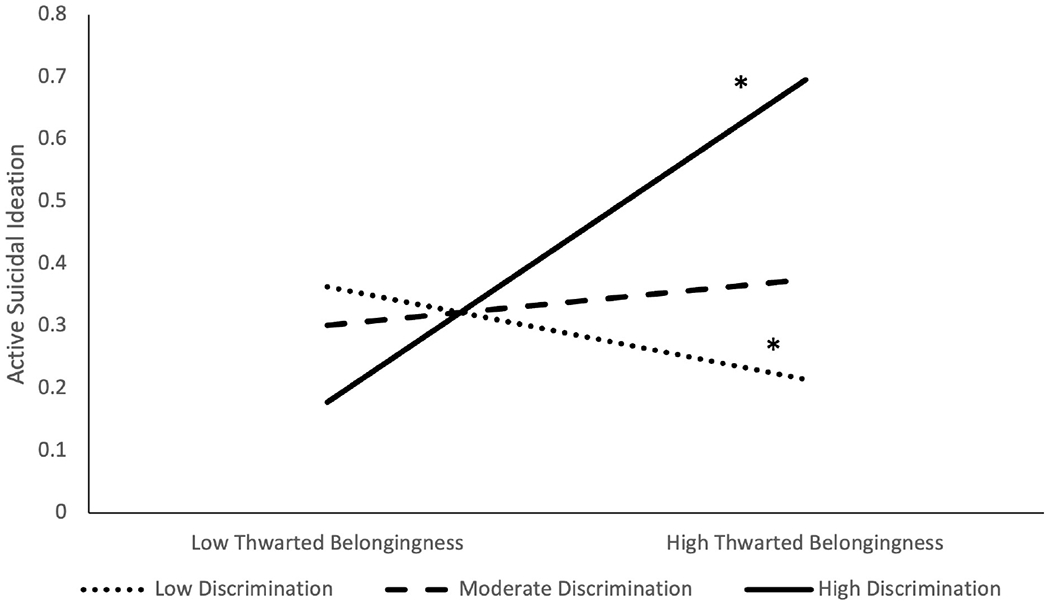

Moderator: Racial discrimination

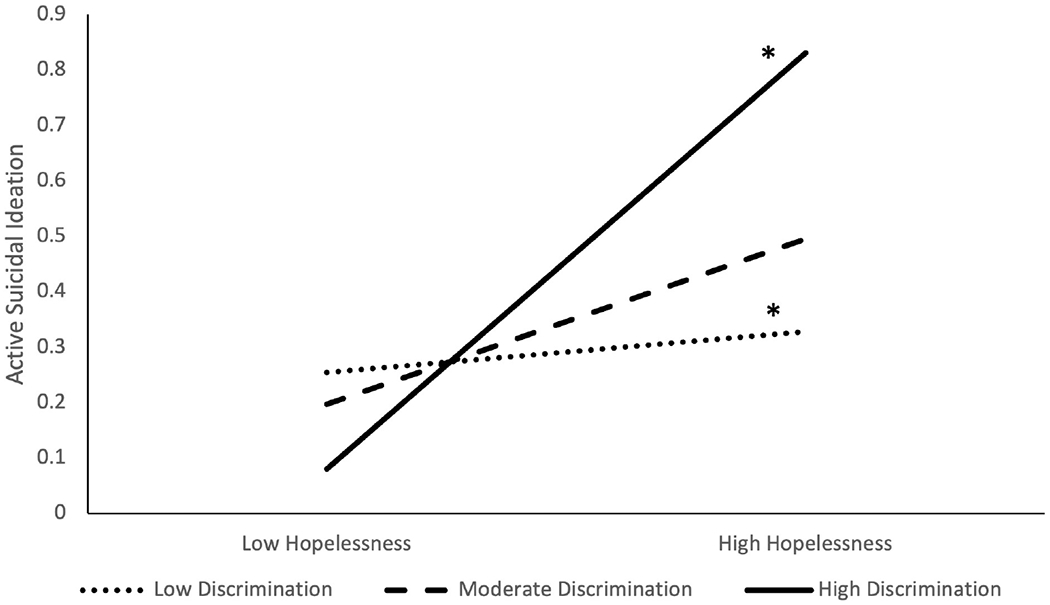

Two models were tested examining racial discrimination as a moderator: one for peer belongingness as a predictor, one for school belongingness as a predictor, and one for hopelessness as a predictor. Results of the peer belongingness model revealed a significant interaction between thwarted peer belongingness and racial discrimination in the prediction of active suicidal ideation (B = 0.0058 SE = 0.001, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.002, 0.009]). The Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that the significance region for the interaction between thwarted peer belongingness and racial discrimination was defined at both low levels and high levels of racial discrimination, such that there was a significant positive association between thwarted peer belongingness and active ideation at values of racial discrimination 0.786 (95% CI [0.001, 0.013]) and larger, and a significant inverse association at values of racial discrimination −2.108 (95% CI [−0.018, −0.0002]) and lower. Specifically, higher levels of thwarted peer belongingness significantly predicted higher levels of active ideation at high racial discrimination, but higher levels of thwarted peer belongingness predicted lower levels of active ideation at low levels of racial discrimination. The association between ideation and thwarted peer belongingness was not significant at moderate levels of racial discrimination (Figure 2). Results of the school belongingness model revealed that racial discrimination did not significantly moderate the association between thwarted school belongingness and active ideation, (B = 0.003, SE = 0.06, p = 0.95, 95% CI [−0.123, 0.130]). Results of the hopelessness model revealed a significant interaction between hopelessness and racial discrimination in the prediction of active suicidal ideation (B = 0.22, SE = 0.06, p = < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.34]). The Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that the significance region for the interaction between hopelessness and racial discrimination was defined at very low levels and high levels of racial discrimination, such that there was a significant inverse association between hopelessness and active ideation at values of racial discrimination −3.84 (95% CI [−1.03, −0.03]) and smaller, and a significant positive association at values of racial discrimination −0.37 (95% CI [0.05, 0.44]) and larger. Specifically, hopelessness predicted lower levels of active ideation at low levels of racial discrimination, but hopelessness predicted higher levels of active ideation at high levels of racial discrimination (Figure 3). The association was not significant at moderate levels of racial discrimination.

FIGURE 2.

Conditional Effect of Peer Belongingness on Active Suicidal Ideation as a Function of Racial Discrimination. Asterisks denote statistically significant slopes.

FIGURE 3.

Conditional Effect of Hopelessness on Active Suicidal Ideation as a Function of Racial Discrimination. Asterisks denote statistically significant slopes.

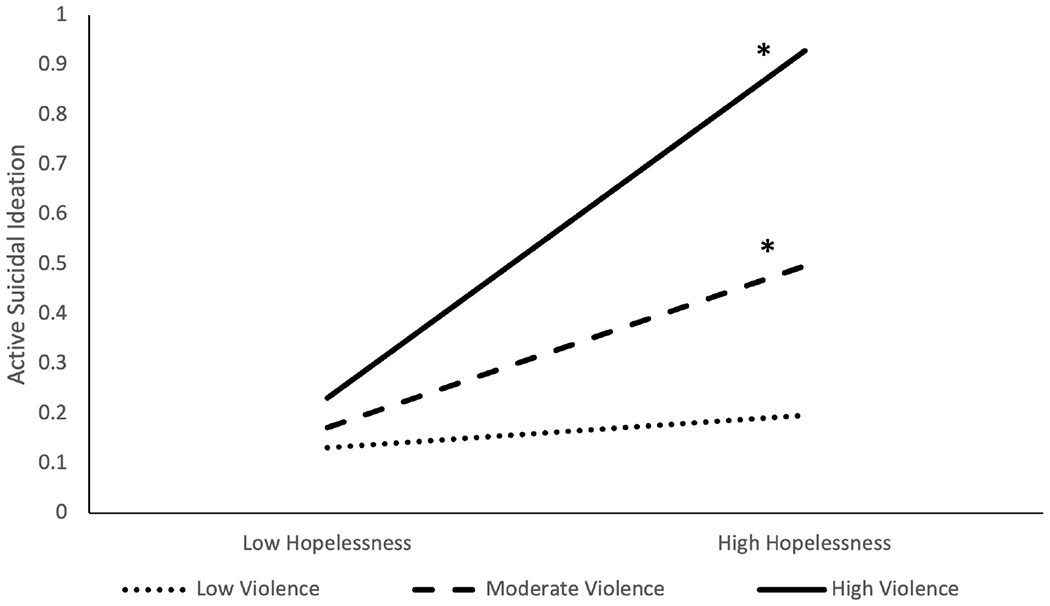

Moderators: Community violence exposure as witness and victim

Two models were tested examining community violence exposure as a moderator. One model examined witnessing violence as a moderator of the association between hopelessness and suicidal ideation. A second model examined violent victimization as a moderator of the association between hopeless and suicidal ideation. Results of the second model revealed a significant interaction between hopelessness and witnessing violence in the prediction of active suicidal ideation (B = 0.29, SE = 0.10, p = 0.003, 95% CI [0.10, 0.48]). The Johnson-Neyman technique revealed that the significance region for the interaction between hopelessness and witnessing violence was defined at moderate and high levels of witnessing violence, such that the association between hopelessness and active ideation were significant at values of witnessing violence −0.30 and larger (95% CI [0.08, 0.47]), but not for values less than −0.30. Specifically, hopelessness predicted higher levels of active ideation at moderate and high levels of witnessing violence, but not at low levels of witnessing violence (Figure 4). In the third model, violent victimization did not significantly moderate the association between hopelessness and active ideation, (B = 0.23, SE = 0.14, p = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.51]).

FIGURE 4.

Conditional Effect of Hopelessness on Active Suicidal Ideation as a Function of Witnessing Community Violence. Asterisks denote statistically significant slopes.

DISCUSSION

The current study examined the moderating effects of socio-cultural risk factors (economic stress, racial discrimination, and community violence) on the association between individual motivating factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and hopelessness) and active suicidal ideation among Black male adolescents. Consistent with predictions, economic stress moderated the association between perceived burdensomeness and active suicidal ideation, with perceived burdensomeness predicting higher levels of active ideation at high levels of economic stress but not at moderate and low levels of economic stress. Also consistent with hypotheses, racial discrimination moderated the association between peer belongingness and suicidal ideation, with thwarted peer belongingness predicting higher levels of active ideation at high levels of racial discrimination, and thwarted peer belongingness predicting lower levels of ideation at low levels of discrimination. However, racial discrimination did not moderate the association between school belongingness and active ideation. Finally, as predicted, the association between hopelessness and suicidal ideation was significantly moderated by both racial discrimination and witnessing community violence, with higher levels of hopelessness predicting more active ideation at high levels of racial discrimination and witnessing community violence. Inconsistent with predictions, violent victimization was not a significant moderator.

In the family systems literature, adolescents’ self-perceptions of burdensomeness derive from feelings of liability and expendability to the family to the extent that they feel as though their families would be better off without them (Prabhu et al., 2010; Woznica & Shapiro, 1990). When asked about their feelings of burdensomeness to their families, adolescents with elevated levels of perceived burdensomeness commonly described themselves as a drain on their family’s time and finances (Hill et al., 2019). Given the disproportionate relegation of Black youth to low socioeconomic communities, it can be understood that the impact of feelings of burdensomeness among Black youth may be exacerbated by the real economic strains that their families may be experiencing (Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020), and also suggests that family economic stress should be considered when screening for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in Black boys. Compared to thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness not only has a more robust association with suicidal ideation, but it is also more resistant to change (King et al., 2018), underscoring the need for additional research to better understand this construct among Black youth.

The findings for peer connectedness build on previous research with Black youth (Assari et al., 2017; Opara, Lardier, et al., 2020; Pierre, et al., 2020). Social connectedness satisfies a fundamental human need for stable, positive, and pleasant interactions with others (Van Orden et al., 2010). Feeling a sense of connectedness and belongingness among peers, family, and community can heavily buffer multidimensional risk factors on psychological well-being by making adolescents feel acknowledged, important, and cared for (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Racial discrimination is an act that diminishes opportunities for this need to be met by increasing feelings of marginalization, ostracism, social isolation (English et al., 2014). Thus, the effects of low levels of connectedness on suicidal ideation are exacerbated by experiences of social exclusion or rejection produced from racial discrimination. Interestingly, it was found that thwarted peer belongingness predicted lower active ideation when racial discrimination was low. This unexpected finding could be due to the fact that when racial discrimination is not a stressor for Black youth, they may experience less ideation even at lower levels of peer belongingness. We suspect the direct relationship, without the inclusion of racial discrimination as a moderator, may produce a direct inverse association similarly found in other studies (Matlin et al., 2011). Further, this finding may also suggest that even at lower levels of social support, Black male youth may be less likely to experience active ideation, as they tend to have lower prevalence estimates of suicidal ideation but have the highest prevalence estimates of suicidal attempts compared to their peers. Future research should explore these associations while looking at suicidal attempts as an outcome. Interestingly, the moderating role of racial discrimination on the association between belongingness and active suicidal ideation was specific to peer belongingness and not school belongingness. There was a main effect of school belongingness on ideation, with higher school belongingness predicting less active ideation. It is not clear why the association between school belongingness and active suicidal ideation was not dependent on levels of racial discrimination. One possibility may be that the sample was recruited from a charter school system in which the overwhelming majority of students, teachers, and administrators were Black, which may have allowed students to feel more connected with their peers and teachers in ways that reduced the possible influence of racial discrimination. Another explanation may be the strong emphasis on school belongingness within this charter school system, including intentional, staff-led, daily activities to strengthen peer mentoring and connection to teachers. As such, participants may have high levels of school belongingness that are less likely to be influenced by discrimination.

The association between hopelessness and active suicidal ideation was influenced by higher levels of both racial discrimination and witnessing community violence. These results suggest that fatalistic views of the future in response to chronic neighborhood conditions and race-related stressors could be socio-cultural markers for suicide risk (Chu et al., 2013; Umlauf et al., 2015). Black boys who witness community violence may be more likely to feel more hopeless about their future and may, in turn, engage in behaviors that result in harm (Burnside et al., 2018). Chronic exposure to racial discrimination and rejection from peers, could impact Black youth’s ability to perceive a positive future, partially due to the lack of affirmation about their skills and abilities and reinforced negative messages about themselves and their communities.

Contrary to our hypothesis, violence victimization did not significantly moderate the association between hopelessness and active ideation. In meta-analytic findings, violent victimization was a stronger predictor of internalizing problems than witnessing community violence (Fowler et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2003). However, compared to violent victimization, witnessing violence may be more likely to lead to diffused feelings of fear and vulnerability, as youth may feel that violence is pervasive and everyone is at risk of exposure (Fowler et al., 2009). A generalized fear may mean a more robust association between hopelessness and witnessing violence than between hopelessness and violent victimization, making it less likely that victimization may interact with hopelessness in the prediction of ideation. Future research should seek to delineate the nuanced impacts of witnessing violence and violent victimization on hopelessness and active ideation among Black youth.

Limitations and strengths

The current study is not without limitations. The current study utilized cross-sectional data, and therefore could not capture causal associations or rule-out reciprocal associations among variables. Future research would benefit from longitudinal designs that include tests of mediation, to gain a better understanding of how the study variables influence one another and suicidal ideation over time. Another limitation is the relatively low internal consistency estimate for the racial discrimination subscale. Although researchers are usually interested in the aggregate effects of stressful life events, these stressors can be relatively independent (e.g., Baldwin & Hoffmann, 2002), resulting in lower reliability estimates. In other words, specific events derived from stress measures may or may not co-occur for participants and greater frequency of stressors, such as racial discrimination, is not dependent upon endorsement of every item in the scale (e.g., Figueroa et al., 2021). Indeed, in other studies using the discrimination subscale of the MESA with other samples of Black youth, findings demonstrate that the internal consistency estimate is lower than typical thresholds of acceptance (e.g., Gaylord-Harden et al., 2011).

Additionally, this study relied on youth self-report, which allows for the possibility of shared method-variance. It should also be noted that perceived burdensomeness was measured with three items from the Suicide Ideation Questionnaire-Jr (Reynolds, 1988), rather than a specific measure of burdensomeness. However, previous research has utilized the same items of the SIQ-Jr to assess perceived burdensomeness (Czyz et al., 2015), and the three items has an internal consistency of 0.81 and correlated adequately (0.59, p < 0.001) with six items assessing the construct of burdensomeness from the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden et al., 2008) in a sample of adolescents (Van Orden et al., 2012). Further, our measure of hopelessness focused on general forms of hopelessness instead of interpersonal hopelessness. Although the internal consistency and predictive validity of both perceived burdensomeness and hopelessness were adequate in the current study, future work in this area may consider including more specific measures of perceived burdensomeness and more specific forms of interpersonal hopelessness (i.e., the Interpersonal Hopelessness Scale; Tucker et al., 2018), related to suicidal ideation to fully test the hypotheses of the Integrated Model (Hagan et al., 2015; Mandracchia, Sunderland, & To, 2021; Mitchell et al., 2023). Future studies may also benefit from including reports from youths’ caregivers and teachers to gain a more holistic understanding of youth’s experiences (Rescorla et al., 2013). Additionally, we utilized two measures as proxies for thwarted belongingness within this study, school belonginess and peer belonginess. It is pivotal to note that Van Orden et al. (2010) state that while social connectedness is a central component of thwarted belongingness, other components, such as the absence of reciprocally caring relationships, “ones in which individuals both feel cared about and demonstrate care of another” is another pivotal aspect of belongingness. Future studies should utilize measures that directly address the absence of positive social interactions and the absence of reciprocally caring relationships to fully capture the concept of thwarted belongingness (Gill et al., 2023).

Further, this study utilized data focused on the experiences of Black male adolescents to highlight the risks associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors among a population with a heightened likelihood to engage in more lethal means of suicide. However, Black youth who live at the intersections of other oppressed identities, including sexual and gender minorities, may be at an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors due to other forms of discrimination. For instance, in a national U.S study by James et al. (2016) results found that transgender adults were nine times more likely (40% compared to 4.6%) to attempt suicide in their lifetime compared to cisgender adults. Further, suicidal ideation and attempts has also been shown to be higher among transgender youth than non-transgender youth (The Trevor Project, 2019). Finally, a study by Vance et al. (2021) found that Black and Latine transgender youth tend to report higher depressive symptoms and suicidality than white transgender youth. However, research is severely limited on the experiences of suicidality among sexual minority and transgender Black girls and boys exposed to community violence and is needed in order to address this important public health issue. Future research should investigate how gender and sexuality-based discrimination may influence active ideation, hopelessness, and thwarted belongingness among Black youth.

In light of these limitations, the current study provides a multi-dimensional understanding of sociocultural risk factors pertinent to suicidal ideation among Black youth. It explores the ways in which contextual factors within ecological systems intersect with interpersonal factors to influence suicidal ideation among an underrepresented and underserved population. Utilizing the bootstrapping method for moderation models also allowed for more accurate estimates of statistics, such that the distribution of the sample was based on consecutively resampled data from the original sample instead of assumptions about the distribution.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The results demonstrate that the Opara, Lardier, et al. (2020) integrated model is a relevant framework for a more refined understanding of the complex relations between individual motivating factors, socio-cultural stressors, and suicidal ideation among Black youth. By highlighting the sociocultural factors that can influence suicidal thoughts and behaviors, the findings serve as a call to action for revised suicide screening measures for Black youth. Current screening measures may not appropriately capture the socio-cultural risk and vulnerability factors of suicidal thoughts and behaviors for Black youth. Additionally, previous work suggests that the lack of identification of active suicide ideation among Black youth exposed to traumatic stressors may be due to implicit biases that lead practitioners to normalize high-risk (cutting, self-injury, substance misuse) and violent behavior among Black youth in ways that would be considered red flags among White youth (Talley et al., 2021). It is pivotal that future training for clinicians, and the development of interventions targeting suicidal ideation address the potential of racial biases affecting the accurate assessment of suicidal ideation among Black youth. As suggested by Standley (2022) it is pivotal to incorporate minority stress models into suicidality risk assessments to provide more nuanced support for youth who live at these intersections. Additionally, Standley suggests that intersectional and socioecological research on suicidality should also explore potential protective factors through socioecological models to more holistically study, analyze, and address suicidality among youth with intersecting marginalized identities. Standley and Foster-Fishman (2021) found that family support significantly reduced the relationship between youth with intersecting marginalized identities and suicidality. This suggests that there are likely pivotal contextually relevant risk and prevention factors for youth who are at risk of suicidality due to their intersecting marginalized identities.

Given the findings that racial discrimination can exacerbate the effects of individual motivating factors on active ideation, future research should explore the impact of protective factors such as racial socialization and racial identity (Gibson et al., 2022). The role of economic stress highlights the need for interventions that involve youth’s caregivers in treatment and empower Black youth to recognize their positive contributions to their family system to help decrease feelings of burdensomeness (Zullo et al., 2022). Furthermore, it may be beneficial to expand the support network of Black adolescents to include community interveners (e.g., mentors, outreach workers, advocates) who specialize in disrupting community violence (Pynoos & Nader, 1988; Stone et al., 2017). Black youth who feel hopeless or traumatized by their environmental conditions and discrimination can be provided opportunities to engage in collective social action (e.g., political organizing and protest, organizing town hall meetings, engaging in community participatory action research, and volunteering with service organizations) to produce social change and address community needs (Walker et al., 2017). Using the Integrated Model may improve research, intervention, and suicide prevention efforts for Black youth in novel ways that are more contextually and culturally relevant.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Akouri-Shan L, Jay SY, DeLuca JS, Petti E, Klaunig MJ, Rakhshan Rouhakhtar P, Martin EA, Reeves GM, & Schiffman J (2022). Race moderates the relation between internalized stigma and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with psychosis-risk syndromes and early psychosis. Stigma and Health, 7(4), 375–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali B, Rockett I, & Miller T (2021). Variable circumstances of suicide among racial/ethnic groups by sex and age: A national violent-death reporting system analysis. Archives of Suicide Research, 25(1), 94–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, & Greenberg MT (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2017). Racial discrimination during adolescence predicts mental health deterioration in adulthood: Gender differences among Blacks. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, & Hoffmann JP (2002). The dynamics of self-esteem: A growth-curve analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, & Leary MR (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Wang Y, Shen Y, Boyle AE, Polk R, & Cheng YP (2018). Racial/ethnic discrimination and well-being during adolescence: A meta-analytic review. American Psychologist, 73(7), 855–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland JM, McCallum DM, Lian B, Bailey CJ, & Rowan P (2001). Hopelessness and violence among inner-city youths. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 5(4), 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Horowitz LM, Fontanella CA, Sheftall AH, Greenhouse J, Kelleher KJ, & Campo JV (2018). Age-related racial disparity in suicide rates among US youths from 2001 through 2015. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(7), 697–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnside AN, Gaylord-Harden NK, So S, & Voisin DR (2018). A latent profile analysis of exposure to community violence and peer delinquency in African American adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Carastathis A. (2014). The concept of intersectionality in feminist theory. Philosophy Compass, 9(5), 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Castellví P, Miranda-Mendizábal A, Parés-Badell O, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, Cebrià A, Gabilondo A, Gili M, Lagares C, Piqueras JA, Roca M, Rodríguez-Marín J, Rodríguez-Jimenez T, Soto-Sanz V, & Alonso J (2017). Exposure to violence, a risk for suicide in youths and young adults. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(3), 195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeks BL, Chavous TM, & Sellers RM (2020). A daily examination of African American adolescents’ racial discrimination, parental racial socialization, and psychological affect. Child Development, 91(6), 2123–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WY (2010). Exposure to community violence and adolescents’ internalizing behaviors among African American and Asian American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(4), 403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. (2019). Adverse experiences. Retrieved January 12, 2024 from https://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=adverse-experiences

- Chu J, Floyd R, Diep H, Pardo S, Goldblum P, & Bongar B (2013). A tool for the culturally competent assessment of suicide: The cultural assessment of risk for suicide (CARS) measure. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, & Brody GH (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley-Strickland M, Quille TJ, Griffin RS, Stuart EA, Bradshaw CP, & Furr-Holden D (2009). Community violence and youth: Affect, behavior, substance use, and academics. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(2), 127–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper SM, Hurd NM, & Loyd AB (2022). Advancing scholarship on anti-racism within developmental science: Reflections on the special section and recommendations for future research. Child Development, 93(3), 619–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello AB, & Osborne J (2019). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 10(1), 7. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Identity politics, intersectionality, and violence against women. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby AE, Ortega L, & Melanson C (2011). Self-directed violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Czyz EK, Berona J, & King CA (2015). A prospective examination of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among psychiatric adolescent inpatients. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 45(2), 243–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Toro J, Wang MT, Thomas A, & Hughes D (2022). An intersectional approach to understanding the academic and health effects of policing among urban adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, & Tibshirani RJ (1994). An introduction to the bootstrap. CRC press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsaesser CM, & Voisin DR (2015). Correlates of polyvictimization among African American youth: An exploratory study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(17), 3022–3042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English D, Lambert SF, Evans MK, & Zonderman AB (2014). Neighborhood racial composition, racial discrimination, and depressive symptoms in African Americans. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54, 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K, & Deeks J (2005). The prevalence of suicidal phenomena in adolescents: A systematic review of population-based studies. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 35(3), 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa WS, Zoccola PM, Manigault AW, Hamilton KR, Scanlin MC, & Johnson RC (2021). Daily stressors and diurnal cortisol among sexual and gender minority young adults. Health Psychology, 40(2), 145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finigan-Carr NM, & Sharpe TL (2022). Beyond systems of oppression: The syndemic affecting Black Youth in the US. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal: C & A, 1–8. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s10560-022-00872-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortgang RG, & Nock MK (2021). Ringing the alarm on suicide prevention: A call to action. Psychiatry, 84(2), 192–195. 10.1080/00332747.2021.1907871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, & Baltes BB (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathologtucy, 21(1), 227–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Cunningham JA, & Zelencik B (2011). Effects of exposure to community violence on internalizing symptoms: Does desensitization to violence occur in African American youth? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Boylan K, Duncan L, Wang L, Colman I, Rhodes AE, Bennett K, Comeau J, Manion I, Boyle MH, & Ontario Child Health Study Team. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of youth suicidal ideation and attempts: Evidence from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(4), 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson SM, Bouldin BM, Stokes MN, Lozada FT, & Hope EC (2022). Cultural racism and depression in Black adolescents: Examining racial socialization and racial identity as moderators. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 32(1), 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill PR, Arena M, Rainbow C, Hosking W, Shearson KM, Ivey G, & Sharples J (2023). Social connectedness and suicidal ideation: The roles of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in the distress to suicidal ideation pathway. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein EV, Prater LC, & Wickizer TM (2022). Preventing adolescent and young adult suicide: Do states with greater mental health treatment capacity have lower suicide rates? Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(1), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Gunnoe ML, Samaniego R, & Jackson K (1995). Validation of a multicultural event schedule for adolescents [Paper presentation]. Fifth Biennial Conference of the Society for Community Research and Action, Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools, 30(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan CR, Podlogar MC, Chu C, & Joiner TE (2015). Testing the interpersonal theory of suicide: The moderating role of hopelessness. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. In Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (Vol. 1, pp. 20). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Hunt QA, Oosterhoff B, Yeguez CE, & Pettit JW (2019). Perceived burdensomeness among adolescents: A mixed-methods analysis of the contexts in which perceptions of burdensomeness occur. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 38(7), 585–604. [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmeland H, & Knizek BL (2020). The emperor’s new clothes? A critical look at the interpersonal theory of suicide. Death Studies, 44(3), 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostinar CE, & Miller GE (2019). Protective factors for youth confronting economic hardship: Current challenges and future avenues in resilience research. American Psychologist, 74(6), 641–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, Stone DM, Gaylor E, Wilkins N, Lowry R, & Brown M (2020). Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—Youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Supplements, 69(1), 47–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James P, Hart JE, Banay RF, & Laden F (2016). Exposure to greenness and mortality in a nationwide prospective cohort study of women. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(9), 1344–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobes DA, & Joiner TE (2019). Reflections on suicidal ideation. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 40(4), 227–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe S, Baser RS, Neighbors HW, Caldwell CH, & Jackson JS (2009). 12-month and lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among black adolescents in the National Survey of American life. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(3), 271–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegler SR, Simon TR, Zwald ML, Chen MS, Mercy JA, Jones C, Mercado-Crespo MC, Blair JM, Stone DM, Ottley PG, & Dills J (2022). Vital signs: Changes in firearm homicide and suicide rates—United States, 2019-2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(19), 656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DC, & Varghese R (2018). Four contexts of institutional oppression: Examining the experiences of Blacks in education, criminal justice and child welfare. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 28(7), 874–888. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy TM, & Ceballo R (2014). Who, what, when, and where? Toward a dimensional conceptualization of community violence exposure. Review of General Psychology, 18(2), 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Elder GH Jr., & Lorenz FO (2003). Reciprocal influences between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Child Development, 74(1), 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CA, Woolley ME, Kerr DCR, & Vinokur A (2014). Factor structure, internal consistency, and predictive validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ-JR) in a sample of suicidal adolescents. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar].

- King JD, Horton SE, Hughes JL, Eaddy M, Kennard BD, Emslie GJ, & Stewart SM (2018). The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide in adolescents: A preliminary report of changes following treatment. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 48(3), 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, & Saffer BY (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. The Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 307–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Boyd RC, Cammack NL, & Ialongo NS (2012). Relationship proximity to victims of witnessed community violence: Associations with adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large M, Corderoy A, & McHugh C (2021). Is suicidal behaviour a stronger predictor of later suicide than suicidal ideation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(3), 254–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey MA, Sheftall AH, Xiao Y, & Joe S (2019). Trends of suicidal behaviors among High School Students in the United States: 1991-2017. Pediatrics, 144(5), e20191187. 10.1542/peds.2019-1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandracchia JT, Sunderland MN, & To YM (2021). Evaluating the role of interpersonal hopelessness in the interpersonal theory of suicide. Death Studies, 45(9), 746–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin SL, Molock SD, & Tebes JK (2011). Suicidality and depression among african american adolescents: The role of family and peer support and community connectedness. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(1), 108–117. 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01078.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza JJ, & Reynolds WM (1999). Exposure to violence in young inner-city adolescents: Relationships with suicidal ideation, depression, and PTSD symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(3), 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh CM, Corderoy A, Ryan CJ, Hickie IB, & Large MM (2019). Association between suicidal ideation and suicide: Meta-analyses of odds ratios, sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value. BJPsych Open, 5(2), E18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, Alayo I, Almenara J, Alonso I, Blasco MJ, Cebrià A, Gabilondo A, Gili M, Lagares C, Piqueras JA, Rodríguez-Jiménez T, Rodríguez-Marín J, Roca M, Soto-Sanz V, Vilagut G, & Alonso J (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 265–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SM, Brown SL, Moscardini EH, LeDuc M, & Tucker R (2024). A psychometric evaluation of the interpersonal hopelessness scale among individuals with elevated suicide risk. Assessment, 31(2), 304–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Butler-Barnes ST, Mayo-Gamble TL, & Inniss-Thompson MN (2018). Excavating new constructs for family stress theories in the context of everyday life experiences of Black American families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(2), 384–405. [Google Scholar]

- Musci RJ, Hart SR, Ballard ED, Newcomer A, van Eck K, Ialongo N, & Wilcox H (2016). Trajectories of suicidal ideation from sixth through tenth grades in predicting suicide attempts in young adulthood in an urban African American cohort. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 46(3), 255–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, & Lee S (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30(1), 133–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara I, Assan MA, Pierre K, Gunn JF III, Metzger I, Hamilton J, & Arugu E (2020). Suicide among black children: An integrated model of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and intersectionality theory for researchers and clinicians. Focus, 20(2), 232–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opara I, Lardier DT Jr., Metzger I, Herrera A, Franklin L, Garcia-Reid P, & Reid RJ (2020). “Bullets have no names”: A qualitative exploration of community trauma among Black and Latinx youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(8), 2117–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orri M, Scardera S, Perret LC, Bolanis D, Temcheff C, Séguin JR, Bolvin M, Turecki G, Tremblay RE, Cote SM, & Geoffroy MC (2020). Mental health problems and risk of suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics, 146(1), 20193823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outland R. (2021). Why Black and Brown youth fear and distrust police: An exploration of youth killed by police in the US (2016/2017), implications for counselors and service providers. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 9(04), 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Pachter LM, Caldwell CH, Jackson JS, & Bernstein BA (2018). Discrimination and mental health in a representative sample of African American and Afro-Caribbean youth. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(4), 831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastore DR, Fisher M, & Friedman SB (1996). Violence and mental health problems among urban high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 18(5), 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre C, Burnside A, & Gaylord-Harden NK (2020). A longitudinal examination of community violence exposure, school belongingness, and mental health among African American adolescent males. School Mental Health, 12(2), 388–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ponnet K, Van Leeuwen K, & Wouters E (2014). Examining mediating pathways between financial stress of mothers and fathers and problem behaviour in adolescents. Journal of Family Studies, 20(1), 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu SL, Molinari V, Bowers T, & Lomax J (2010). Role of the family in suicide prevention: An attachment and family systems perspective. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 74(4), 301–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JH, & Khubchandani J (2019). The changing characteristics of African American adolescent suicides, 2001–2017. Journal of Community Health, 44(4), 756–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pynoos RS, & Nader K (1988). Psychological first aid and treatment approach to children exposed to community violence: Research implications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 1(4), 445–473. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla LA, Ginzburg S, Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, Almqvist F, Begovac I, Bilenberg N, Bird H, Chahed M, Dobrean A, Döpfner M, Erol N, Hannesdottir H, Kanbayashi Y, Lambert MC, Leung PW, Minaei A, Novik TS, Oh KJ, … Verhulst FC (2013). Cross-informant agreement between parent-reported and adolescent self-reported problems in 25 societies. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(2), 262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM (1988). SIQ, Suicidal ideation questionnaire: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson WL, Whipple CR, Keenan K, Flack CE, & Wingate L (2022). Suicide in African American adolescents: Understanding risk by studying resilience. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 359–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossom RC, Coleman KJ, Ahmedani BK, Beck A, Johnson E, Oliver M, & Simon GE (2017). Suicidal ideation reported on the PHQ9 and risk of suicidal behavior across age groups. Journal of Affective Disorders, 215, 77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruch DA, Sheftall AH, Schlagbaum P, Rausch J, Campo JV, & Bridge JA (2019). Trends in suicide among youth aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1975 to 2016. JAMA Network Open, 2(5), 193886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott LN, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, Keenan K, & Stepp SD (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation as predictors of suicide attempts in adolescent girls: A multi-wave prospective study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, & Jackson JS (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selner-O’Hagan MB, Kindlon DJ, Buka SL, Raudenbush SW, & Earls FJ (1998). Assessing exposure to violence in urban youth. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 39(2), 215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheftall AH, Vakil F, Ruch DA, Boyd RC, Lindsey MA, & Bridge JA (2022). Black youth suicide: Investigation of current trends and precipitating circumstances. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(5), 662–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley CJ (2022). Expanding our paradigms: Intersectional and socioecological approaches to suicide prevention. Death Studies, 46(1), 224–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Standley CJ, & Foster-Fishman P (2021). Intersectionality, social support, and youth suicidality: A socioecological approach to prevention. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 51(2), 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard SA, Zimmerman MA, & Bauermeister JA (2011). Thinking about the future as a way to succeed in the present: A longitudinal study of future orientation and violent behaviors among African American youth. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DM, Holland KM, Bartholow B, Crosby AE, Davis S, & Wilkins N (2017). Preventing suicide: A technical package of policies, programs, and practices. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Bussing R, Jacob ML, Nadeau JM, Crawford E, Mutch PJ, Mason D, Lewin AB, & Murphy TK (2015). Frequency and correlates of suicidal ideation in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 46, 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, & Fidell LS (2001). Cleaning up your act: Screening data prior to analysis. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5, 61–116. [Google Scholar]

- Talley D, Warner ŞL, Perry D, Brissette E, Consiglio FL, Capri R, Violano P, & Coker KL (2021). Understanding situational factors and conditions contributing to suicide among Black youth and young adults. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 58, 101614. [Google Scholar]

- The Trevor Project. (2019). National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/The-Trevor-ProjectNational-Survey-Results-2019.pd

- Tucker RP, Hagan CR, Hill RM, Slish ML, Bagge CL, Joiner TE Jr., & Wingate LR (2018). Empirical extension of the interpersonal theory of suicide: Investigating the role of interpersonal hopelessness. Psychiatry Research, 259, 427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umlauf MG, Bolland AC, Bolland KA, Tomek S, & Bolland JM (2015). The effects of age, gender, hopelessness, and exposure to violence on sleep disorder symptoms and daytime sleepiness among adolescents in impoverished neighborhoods. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(2), 518–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]