Abstract

Introduction and significance

Lymphangiomas are benign tumors that are typically found in the neck and armpit region but can also occur in other locations. The clinical presentation varies depending on their location and size, and surgical resection is the primary treatment option.

Case presentation

We present the case of a child who presented with a painless and non-obstructing abdominal mass. The mass was diagnosed and underwent complete surgical resection. Subsequent tissue analysis confirmed that the cyst was a lymphangioma.

Clinical discussion

These tumors should be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic lesions in the abdomen, and the importance of performing complete surgical resection is emphasized.

Conclusion

The importance of complete surgical resection for mesenteric lymphangioma must be emphasized. Partial resection or aspiration should not be performed due to the risk of complications associated with these procedures and the increased risk of recurrence.

Keywords: Case report, Lymphangiomas, Pediatric surgery, Lymphatic malformation

Highlights

-

•

Mesenteric lymphangiomas are considered very rare in children.

-

•

They are often asymptomatic and may present with a complication.

-

•

The gold standard treatment is complete surgical excision.

-

•

The final diagnosis is made through histological examination.

1. Introduction

Mesenteric lymphangiomas are considered rare benign tumors that originate from lymphatic vessels, with an incidence ranging from 1 in 1000 to 16,000 live births [1]. They are most commonly found in the neck, particularly in the posterior triangle (70–80 %) [2]. The remaining distribution includes 20–30 % in the axilla, upper mediastinum, mesentery, pelvis, and lower extremities [3]. Approximately 5 % of lymphangiomas are located in the abdomen, with 50 % of those occurring in the small intestine [4].

Despite their benign nature, lymphangiomas can cause complications such as abdominal obstruction, intussusception, or intestinal volvulus. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial, as the tumor mass can lead to these surgical complications [5].

Complete surgical resection is the mainstay of lymphangioma treatment.

This case is described in accordance with the criteria of SCARE [6].

2. Presentation of case

2.1. Patient information

We report the case of a 2-year-old male child who presented with an enlarged abdomen for the past 1.5 years, along with poor feeding ability. He did not experience constipation, other abdominal symptoms, fever, or jaundice. The baby was born naturally without any pregnancy complications, and the mother denied taking any medications during pregnancy. There was no family history of tumors or deformities.

3. Clinical findings

Upon arrival at the hospital, the child was in good general condition. His pulse and temperature were within normal limits, and he weighed approximately 8 kg. Upon general examination of the abdomen, there was an increase in abdominal size with visible vascular markings on the abdominal wall. Upon palpation, the abdomen was soft and distended, with a large mass palpable within the abdomen. No signs of peritoneal irritation were present. There were no jaundice signs evident upon examination.

The clinical examination of the remaining organs was within normal.

4. Diagnostic assessment

Laboratory examinations revealed a hemoglobin of 13.8 g/dL, total white blood cell count of 12,000/mm3, platelet count of 623,000/mm.

All tumor markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA 125, CA19–9, Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and B Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) were within normal ranges.

Abdominal ultrasound revealed a large cystic mass in the right upper abdomen (hypochondrium), extending down to the pelvis. The mass contained multiple fluid-filled spaces.

The CT scan confirmed the presence of a large cystic mass in the right upper abdomen, measuring approximately 12.5 cm in diameter. The mass contained multiple thin internal partitions (septa) (Fig. 1.A–C).

Fig. 1.

A: CT/cross axial view showing the beginning of the cystic formation appears with fluid content within it and compression of the bowel loops where the blue color indicates the cyst.

B: CT/cross-axial view showing the cyst extending into the pelvis, almost filling the pelvis with the cystic formation.

C: CT/cross axial view showing the cystic formation is located in front of the bladder and compresses both the bladder and rectum where the green color indicates the cyst, the blue color indicates the rectal and the yellow color indicates the bladder.

5. Therapeutic intervention

Based on the previous findings, it was decided to perform surgery.

Under general anesthesia, a transverse incision was made in the upper abdomen, right of the navel. Upon entering the abdominal cavity, a large cyst was identified at the end of the ileum, located about 20 cm from the ileocecal junction. The cyst was severely adhered to the ileum, with the ileum embedded within the cystic mass. The cyst was not clearly connected to the abdominal mesentery, and it was not possible to separate the cyst from the intestine without damaging it (Fig. 2.A).

Fig. 2.

A: Intraoperative image showing the large lymphangioma attached to the intestine on both sides.

B: Image showing complete resection of the lymphangioma with the attached intestine.

C: Intraoperative image showing ileal anastomosis in place of the lymphangioma before closing the mesenteric defect.

Due to the severe adhesion and lack of clear separation between the cyst and the ileum, a decision was made to perform resection of the entire cyst along with the attached segment of ileum (Fig. 2.B), About 10 cm of the ileum was removed, with the creation of a ileal anastomosis (Fig. 2.C) and closure of the layers.

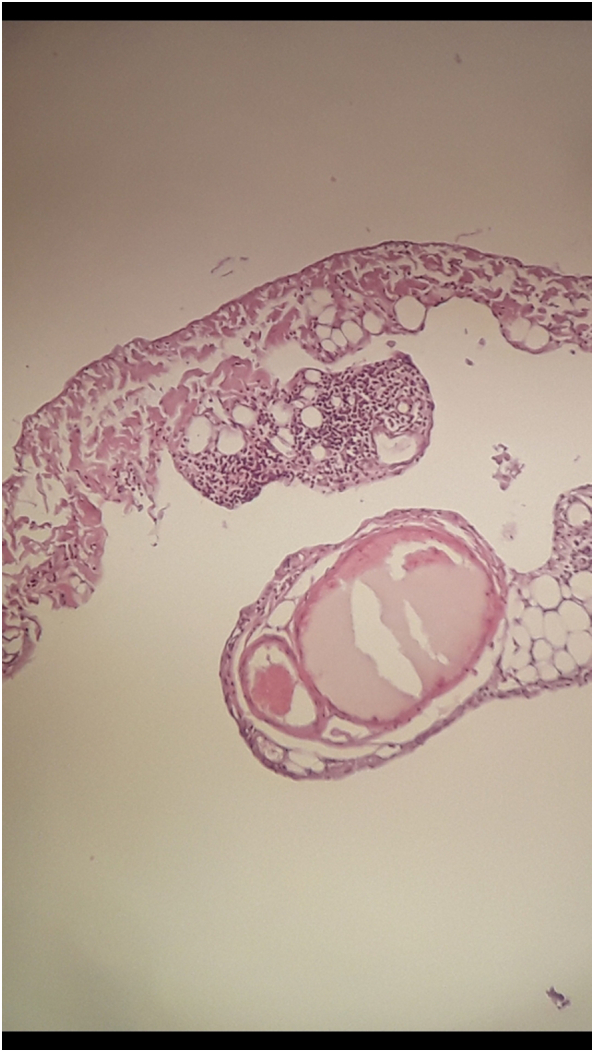

Post-operative pathological examination of the resected cyst confirmed the diagnosis of lymphangioma (Fig. 3.A).

Fig. 3.

A: Histopathologic examination of the lesion shows lymphoid aggregates and dilated lymphatic channels lined with endothelium.

The child was monitored in the hospital for a week, then she was discharged in good general condition.

6. Discussion

Lymphangiomas are benign vascular malformations, not tumors, and are fairly rare in children, constituting about 5 % of all benign pediatric tumors [7]. These lesions typically occur in the head and neck region. Mesenteric lymphangiomas are significantly less common, representing only 1 % of all lymphangiomas [8].

The precise understanding of these malformations' physiology remains elusive, and the exact cause of their formation is undetermined. Some theories suggest a genetic contribution, as lymphangiomas are often associated with specific genetic syndromes like Turner, Noonan, Down syndrome, cardiac abnormalities, and fetal hydrops [9]. Others propose that these malformations arise from the failure of proper lymphatic channel connections during development [10].

Most mesenteric lymphangiomas are painless abdominal masses but may present with symptoms like abdominal pain, obstruction, or distension, depending on the location and size of the malformation [11]. In our case, the mass was easily palpable due to its large size filling the abdomen.

The differential diagnoses for mesenteric lymphangiomas include duplication cysts, mesenteric cysts, mesotheliomas, teratomas, and lipomas [[12], [13]].

The initial radiological investigation is abdominal ultrasound because of its ease of use and low cost. Computed tomography (CT) is also employed for diagnosis, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the gold standard as it delineates these malformations more precisely, as well as their relationship to surrounding structures [14].

Regarding the treatment of mesenteric lymphangiomas, several treatment options are mentioned depending on the location. Bleomycin injection, which causes a non-specific inflammatory process that eventually leads to fibrosis in the cyst, can be used. It is used in very small doses [15]. Drainage may also be used, but it carries the risk of recurrence or perforation during the procedure. Partial resection is another option, but it comes with the risk of infection, bleeding, or lymphatic fistulas [11].

Therefore, complete surgical resection is considered the gold standard treatment for mesenteric lymphangiomas [16].

7. Conclusion

The prognosis for mesenteric lymphangiomas is generally good, With complete surgical resection, the recurrence rate is low. However, there is a risk of complications such as bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding structure.

Abbreviations

- US

Ultrasound

- CT

Computed tomography

Consent of patient

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethical approval

Not required for case reports. Single case reports are exempt from ethical approval.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Guarantor

Kamar Shaker.

Research registration number

N/A

CRediT authorship contribution statement

K.S.: Conceptualization, resources, who wrote, original drafted, edited, visualized, validated, literature reviewed the manuscript, and the corresponding author who submitted the paper for publication.

K.A.: Supervision, visualization, validation, resources, and review of the manuscript.

M.D and Z.B; Visualization, validation, and review of the manuscript

L.K.: Pediatric Specialist - Professor of Pediatric Digestive Diseases at Children's University Hospital - Professor of Pediatrics at Damascus University

N.N :MD, pediatrics surgery specialist, who performed and supervised the operation.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data were obtained from the hospital computer-based in-house system. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Kumar V., Kumar P., Pandey A., Gupta D.K., Shukla R.C., Sharma S.P., Gangopadhyay A.N. Intralesional bleomycin in lymphangioma: an effective and safe non-operative modality of treatment. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2012;5(2):133–136. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.99456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song T.B., Kim C.H., Kim S.M., Kim Y.H., Byun J.S., Kim E.K. Fetal axillary cystic hygroma detected by prenatal ultrasonography: a case report. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2002;17(3):400–402. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.3.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manikoth P., Mangalore G.P., Megha V. Axillary cystic hygroma. J. Postgrad. Med. 2004;50(3):215–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alqahtani A., Nguyen L.T., Flageole H., Shaw K., Laberge J.M. 25 years’ experience with lymphangiomas in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1999;34(7):1164–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wan Y.L., Lee T.Y., Hung C.F., Ng K.K. Ultrasound and CT findings of a cecal lymphangioma presenting with intussusception. Eur. J. Radiol. 1998;27(1):77–79. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(97)00061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Maria N., Kerwan A., Franchi T., Agha R.A., et al. The SCARE 2023 guideline: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 2023;109(5):1136–1140. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clement C., Snoekx R., Ceulemans P., Wyn I., Matheï J. An acute presentation of pediatric mesenteric lymphangioma: a case report and literature overview. Acta Chir. Belg. 2018;118(5):331–335. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2017.1379802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Botey M., Muñoz-Ramos C., Bonfill J., Roura J., Torres M., Mocanu S., Arner T., Pérez G., Salvans F., García-San-Pedro Á. Acute abdomen for lymphangioma of the small bowel mesentery: a case report and review of the literature. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2015;107(1):39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr R.F., Ochs R.H., Ritter D.A., Kenny J.D., Fridey J.L., Ming P.M. Fetal cystic hygroma and Turner’s syndrome. American Journal of Diseases of Children (1960) 1986;140(6):580–583. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200090035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosfeld J.L., Skinner M.A., Rescorla F.J., West K.W., Scherer L.R., 3rd Mediastinal tumors in children: experience with 196 cases. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 1994;1(2):121–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02303555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunadi Kashogi, Prasetya D., Fauzi A.R., Daryanto E., Dwihantoro A. Pediatric patients with mesenteric cystic lymphangioma: a case series. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019;64:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Méndez-Gallart R., Solar-Boga A., Gómez-Tellado M., Somoza-Argibay I. Giant mesenteric cystic lymphangioma in an infant presenting with acute bowel obstruction. Canadian Journal of Surgery. Journal Canadien de Chirurgie. 2009;52(3):E42–E43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alomar K., Mansour H., Qatleesh S., Eid N., Alkader M.A., Al Dalati H. Diagnosis and surgical management of a rare case of duodenal duplication cyst in a neonate: case report and literature review. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023;107 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2023.108354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perkins J.A., Manning S.C., Tempero R.M., Cunningham M.J., Edmonds J.L., Jr., Hoffer F.A., Egbert M.A. Lymphatic malformations: current cellular and clinical investigations. Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery: Official Journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;142(6):789–794. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heit J.J., Do H.M., Prestigiacomo C.J., Delgado-Almandoz J.A., English J., Gandhi C.D., Albuquerque F.C., Narayanan S., Blackham K.A., Abruzzo T., Albani B., Fraser J.F., Heck D.V., Hussain M.S., Lee S.K., Ansari S.A., Hetts S.W., Bulsara K.R., Kelly M., Arthur A.S.…SNIS Standards and Guidelines committee Guidelines and parameters: percutaneous sclerotherapy for the treatment of head and neck venous and lymphatic malformations. Journal of Neurointerventional Surgery. 2017;9(6):611–617. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steyaert H., Guitard J., Moscovici J., Juricic M., Vaysse P., Juskiewenski S. Abdominal cystic lymphangioma in children: benign lesions that can have a proliferative course. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1996;31(5):677–680. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90673-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because the data were obtained from the hospital computer-based in-house system. Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.