Abstract

目的

青光眼是不可逆性致盲性眼病的主要病因,目前尚无有效疗法逆转青光眼的视觉系统损害。最近发现干细胞疗法有望使受损的视网膜神经元修复和再生,但是在干细胞来源方面仍然存在较大挑战。本研究探寻一种将视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,进一步高效定向分化为视网膜神经节细胞的方案,以期为青光眼的干细胞治疗提供新的细胞获取途径。

方法

用表皮细胞生长因子和成纤维细胞生长因子2诱导大鼠视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞。构建Trim9过表达慢病毒(PGC-FU-Trim9-GFP),感染由Müller细胞诱导去分化而来的视网膜干细胞,通过荧光显微镜观察和流式细胞术评估病毒感染效率。用视黄酸和脑源性神经营养因子处理过表达或未过表达Trim9的视网膜干细胞以诱导其分化为神经元和神经胶质细胞。采用免疫荧光、PCR/real-time RT-PCR和蛋白质印迹法检测各细胞标志物(GLAST、GS、rhodopsin、PKC、HPC-1、Calbindin、Thy1.1、Brn-3b、Nestin、Pax6)的表达。

结果

表皮细胞生长因子和成纤维细胞生长因子2处理后的大鼠视网膜Müller细胞表达视网膜干细胞标志物Nestin和Pax6。视黄酸和脑源性神经营养因子处理后的过表达Trim9的视网膜干细胞Thy1.1阳性细胞明显增多,表明其定向分化为视网膜神经节细胞。

结论

本研究成功将大鼠视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,并发现Trim9可有效促进由视网膜Müller细胞去分化而来的视网膜干细胞定向分化为视网膜神经节细胞。

Keywords: 青光眼, Müller细胞, Trim9, 视网膜干细胞, 视网膜神经节细胞

Abstract

Objective

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness, and effective therapies to reverse the visual system damage caused by glaucoma are still lacking. Recently, the stem cell therapy enable the repair and regeneration of the damaged retinal neurons, but challenges regarding the source of stem cells remain. This study aims to investigate a protocol that allows the dedifferentiation of Müller cells into retinal stem cells, following by directed differentiation into retinal ganglion cells with high efficiency, and to provide a new method of cellular acquisition for retinal stem cells.

Methods

Epidermal cell growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2 were used to induce the dedifferentiation of rat retinal Müller cells into retinal neural stem cells. Retinal stem cells derived from Müller cells were infected with a Trim9 overexpression lentiviral vector (PGC-FU-Trim9-GFP), and the efficiency of viral infection was assessed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Retinoic acid and brain-derived neurotrophic factor treatments were used to induce the differentiation of the retinal stem cells into neurons and glial cells with or without the overexpression of Trim9. The expressions of each cellular marker (GLAST, GS, rhodopsin, PKC, HPC-1, Calbindin, Thy1.1, Brn-3b, Nestin, Pax6) were detected by immunofluorescence, PCR/real-time RT-PCR or Western blotting.

Results

Rat retinal Müller cells expressed neural stem cells markers (Nestin and Pax6) with the treatment of epidermal cell growth factor and fibroblast growth factor 2. The Thy1.1 positive cell rate of retinal stem cells overexpressing Trim9 was significantly increased, indicating their directional differentiation into retinal ganglion cells after treatment with retinoic acid and brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

Conclusion

In this study, rat retinal Müller cells are dedifferentiated into retinal stem cells successfully, and Trim9 promotes the directional differentiation from retinal stem cells to retinal ganglion cells effectively.

Keywords: glaucoma, Müller cells, Trim9, retinal stem cells, retinal ganglion cells

青光眼是全球不可逆失明的主要原因[1],全球40~80岁人群的青光眼患病率约为3.5%,预计2040年将有1.118亿人患青光眼[2]。青光眼在中国致单眼盲者约520万,致双眼盲者约170万[3-4],对中国社会医疗体系的危害不容小觑。

青光眼是以视网膜神经节细胞(retinal ganglion cell,RGC)进行性丧失以及视盘进行性凹陷为共同特征的进行性视神经疾病[1, 5-6]。眼压升高是青光眼的主要危险因素[7-10]。目前唯一可预防青光眼视觉损害进展的方法就是降低眼内压[5, 11-12]。由于成人无正常再生视网膜神经元的内源性干细胞,RGC的丧失会导致永久性视力丧失[5, 13-14]。因此,寻找干细胞疗法修复和再生RGC有望成为逆转青光眼视觉损伤的治疗方案[15]。目前用于视网膜移植的干细胞主要包括视网膜自身干细胞和来源于其他部位的干细胞及体细胞诱导形成的诱导性多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cell,iPSC)[14, 16-19]。然而,视网膜自身干细胞来源有限[20],而其他干细胞和体细胞来源的iPSC的临床应用存在伦理限制和排斥反应[21-22]。若能将一种自身来源且数量丰富的视网膜干细胞定向诱导分化为RGC,将为青光眼的治疗提供更为行之有效的方案。

Müller细胞是视网膜的放射状胶质细胞,占视网膜神经胶质细胞的90%[23],对于维持视网膜的结构和功能至关重要[24]。Müller细胞也被认为是潜在的视网膜干细胞[25-28]。研究[27, 29-33]表明:斑马鱼、鸡和大鼠的视网膜Müller细胞可被多种因素诱导去分化,呈现出干细胞特征。若能将视网膜中丰富的Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,再将其定向诱导分化为RGC,或许可达到治疗青光眼的目的。但视网膜干细胞受细胞外微环境和内在细胞因子的共同调控,定向分化机制复杂[34-37]。因此,探寻增强Müller细胞定向分化为RGC的手段以获得更高比例的RGC,对青光眼的治疗至关重要。

Trim9是三结构域蛋白(tripartite motif,TRIM) 家族成员[38-40],被鉴定为皮层神经元中神经元形态发生的调节因子[39],可调控成年新生的神经元的形态发生[41]。Trim9不足可导致神经轴突导向功能缺陷[42],并影响小鼠的空间认知与记忆能力[41]。研究[43]发现在转录了RGC分化必需的调控因子Atoh7后,小鼠视网膜高度表达Trim9,表明RGC的分化过程可能受到Trim9蛋白的调控。由此推测,具有视网膜干细胞潜质的Müller细胞向RGC的定向分化很可能也受Trim9的调控。然而Trim9与视网膜Müller细胞定向分化为RGC的关系尚不明确,需要进一步的研究来揭示。

本研究拟通过表皮细胞生长因子(epidermal growth factor,EGF)和成纤维细胞生长因子2(fibroblast growth factor 2,FGF2)处理将高度表达谷氨酸/天冬氨酸转运体(glutamate/aspartate transporter,GLAST)和谷氨酰胺合成酶(glutamine synthetase,GS)的大鼠视网膜Müller细胞去分化为表达Nestin和Pax6(视网膜干细胞标志物[44])的视网膜干细胞,再在由Müller细胞去分化而来的视网膜干细胞中过表达Trim9,并采用视黄酸(retinoic acid,RA)和脑源性神经营养因子(brain-derived neurotrophic factor,BDNF)处理以诱导分化为神经元和神经胶质细胞。本研究提出的这种将视网膜Müller细胞定向分化为RGC的方案,可为青光眼的视网膜损伤治疗提供一条崭新的基因治疗和视神经再生途径。

1. 材料与方法

1.1. 主要试剂

EGF(美国MCE公司产品,货号HY-P71171)、FGF2(美国MCE公司产品,货号HY-P7331A)、谷氨酰胺(美国MCE公司产品,货号HY-100587)、青霉素-链霉素溶液(上海生工生物工程股份有限公司产品,货号E607011)、BDNF(美国MCE公司产品,货号HY-P7116A)和DMEM/F12(美国Gibco公司产品,货号C11330500BT)均购自赛默飞世尔科技(中国)有限公司。抗体GLAST(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab181036)、GS(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab176562)、Nestin(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab221660)、Pax6(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab195045)、Thy1.1(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab181469)、Brn-3b(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab128849)、rhodopsin(德国CST公司产品,货号#14825)、蛋白激酶C(protein kinase C,PKC,德国CST公司产品,货号#59090)、造血祖细胞(hematopoietic progenitor cell,HPC-1,英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab154160)、Calbindin(英国Abcam公司产品,货号ab229915)、β-actin(美国Proteintech公司产品,货号66009-1-Ig)、TRIzol(美国Invitrogen公司产品,货号GT1402)、RevertAid RT(美国Thermo Fisher Scientific公司产品,货号K1691)和SYBR® Green Realtime PCR Master Mix(美国GENVIEW公司产品,货号GR1201)均购自长沙维世尔生物科技公司。OE-Trim9-NC慢病毒购自湖南丰晖生物科技有限公司。大鼠Müller细胞(CP-R117)购自武汉普诺赛生命科技公司。

1.2. 视网膜Müller细胞的培养和去分化

将购买的Müller细胞在含10% FBS、青霉素、链霉素的DMEM中培养5~7 d以获得状态良好的细胞群。采用免疫荧光和PCR法鉴定所购细胞是否为Müller细胞。将鉴定后的Müller细胞在含有20 ng/mL EGF、10 ng/mL FGF2、1×N2补充液、2 mmol/L谷氨酰胺、100 U/mL青霉素和100 μg/mL链霉素的DMEM/F12培养基中培养3~5 d,以诱导Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞。

1.3. 慢病毒感染预实验

取对数生长期的Müller细胞,用0.25%的胰蛋白酶消化,接种于24孔板[每孔(1~5)×103个细胞],于37 ℃、5% CO2培养箱中培养过夜。根据病毒感染复数(multiplicity of infection,MOI)以及细胞接种量计算所需病毒液体积。病毒液体积=(MOI×细胞数目)/病毒滴度。根据感染增强剂说明书的比例计算感染增强剂用量,将OE-NC空载慢病毒与增强剂进行混合。弃去24孔板中原有培养基,加入100 μL含4%感染增强剂的无双抗培养基到细胞培养板中,24 h后镜下观察荧光,并换完全培养基继续培养48 h。72 h时,荧光显微镜下观察荧光强度确定感染效率。感染效率高且细胞生长良好所对应的增强剂和MOI即可作为后续实验的感染条件。

1.4. 流式细胞术分析病毒感染效率

将慢病毒感染的细胞经2%的多聚甲醛固定后直接上机检测。流式细胞仪建立前向角散射(forward scatter,FSC)/异硫氰酸荧光素(fluorescein isothiocyanate,FITC)双参数散点图,根据其信号调节光电倍增管(photornultiplier tube,PMT)电压,得到合适的流式图。流式细胞仪选用70 µm的喷嘴,设置FSC电压值为10 V,侧向角散射(side scatter,SSC)为250 V,荧光通道PMT电压调整至合适值,确保经0.1 μm滤头过滤后的PBS上样后,在最低流速下的颗粒数<10 events/s。在双参数FSC/SSC散点图中找到病毒感染的细胞最集中区域,圈出所需要分析的细胞,并采用FlowJo v10.0.8软件进行数据分析。

1.5. 去分化的视网膜干细胞定向分化为RGC

参照文献[45]的方法,将由Müller细胞去分化而来的视网膜干细胞以104/孔的初始密度接种在含 1 μmol/L RA和1% FBS的DMEM/F12培养基的6孔板中,于37 ℃、5% CO2培养箱中培养5 d。用DMEM洗涤细胞3次,并加入含1 ng/mL BDNF的DMEM/F12(无血清)培养基,于37 ℃、5% CO2培养箱中孵育5、7或14 d,以诱导分化为RGC。

1.6. 免疫荧光检测

用4%的多聚甲醛固定待测细胞15 min,然后用生理盐水浸洗玻片3次。用0.5% Triton X-100在室温下通透15 min,再用生理盐水浸洗玻片3次。玻片滴加适量一抗(GLAST,1꞉50;GS,1꞉500;Nestin,1꞉100;Thy1.1,1꞉250),4 ℃下孵育过夜。用生理盐水浸洗玻片3次,每次3 min,后滴加适量荧光二抗,于湿盒中37 ℃下孵育1 h。用生理盐水浸洗3次,滴加DAPI避光孵育5 min。用生理盐水浸洗玻片4次,洗去多余的DAPI,在荧光显微镜下采集图像。

1.7. 聚合酶链式反应/实时荧光定量

在对Müller细胞进行胰蛋白酶消化后,使用TRIzol试剂从细胞中分离出总RNA,并使用RevertAid RT试剂盒进行反转录。聚合酶链式反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR)检测:将反转录的cDNA和引物配置成反应体系,置于PCR仪中,95 ℃变性3 min、60 ℃退火15 s,72 ℃延伸10 s,循环40次。将PCR扩增产物在1.5%的琼脂糖凝胶上120 V的电压下电泳20 min,用凝胶成像系统观察并拍照记录。实时荧光定量PCR(real-time RT-PCR)检测:按照SYBR® Green Realtime PCR Master Mix试剂盒说明书,将反转录的cDNA、引物和SYBR Green I mix (2×)配置成反应体系,将反应体系置于PCR仪中,95 ℃变性3 min、60 ℃退火15 s,72 ℃延伸10 s,循环40次。GAPDH被用作内部对照进行归一化。目标基因的相对表达量用2-ΔΔCt方法测定。引物信息见表1。

表1.

用于PCR/real-time PCR检测的引物信息

Table 1 Primer information for PCR/real-time PCR detection

| 引物名称 | 引物序列(5'-3') | 引物大小/bp |

|---|---|---|

| Rhodopsin |

Forward: GCTGTGGCTGACCTCTTCAT Reverse: AGGCCGATTTCACCTCCAAG |

137 |

| PKC |

Forward: GGCCTGCAATGTCAAGTCTG Reverse: GTAGCTGTGCAGACGGAACT |

138 |

| HPC-1 |

Forward: GTGAGATCGAGACCAGGCAC Reverse: TCAATCATCTCCCCCTGGCT |

115 |

| Calbindin |

Forward: TGTGTGAGAAAAACAAACAGGAAT Reverse: GTCCCCAGCAGAGAGAATAAGG |

128 |

| Thy1.1 |

Forward: GGACTGCCGCCATGAGAATA Reverse: GTATCCCAAGGGTGCCTGAG |

101 |

| Brn-3b |

Forward: AGAAATCCCACCGCGAGAAG Reverse: TTGGCTGGATGGCGAAGTAG |

126 |

| Nestin |

Forward: GGTAGGGCTAGAGGACCCAA Reverse: TGGGCAATTCAAGGATCCCC |

161 |

| Pax6 |

Forward: CCGAATTCTGCAGGTGTCCA Reverse: GTCGCCACTCTTGGCTTACT |

111 |

| GLAST |

Forward: CTGTCATTGTGGGAATGGCG Reverse: TATGCCGATCACCACAGCAA |

110 |

| GS |

Forward: GAGATCGCGACGTACCTGAA Reverse: CACTTGCAGCTTGCGTGATT |

122 |

| GAPDH |

Forward: GCAAGTTCAACGGCACAG Reverse: GCCAGTAGACTCCACGACAT |

140 |

1.8. 蛋白质印迹法

根据目的蛋白质分子量大小,配置分离胶和5%的浓缩胶。上样时保证每孔体积相同,各含20 μg蛋白质。然后在80 V电压下电泳40 min,在120 V电压下电泳30~50 min。待溴酚蓝跑至胶底时终止电泳,在100 V电压下将蛋白质转移到0.45 μm的PVDF膜上。转膜完成后将PVDF膜完全浸没在5%的BSA-PBST中,在室温下轻摇1 h。然后在4 ℃下与5% BSA-PBST稀释的一抗(Pax6,1꞉1 000;Brn-3b,1꞉100;Nestin,1꞉1 000;rhodopsin,1꞉1 000;HPC-1,1꞉500;Thy1.1,1꞉500;GLAST,1꞉1 000;PKC,1꞉1 000;Calbindin,1꞉1 000;GS,1꞉1 000;β-actin,1꞉1 000)孵育过夜。次日取出PVDF膜,用PBST洗膜5次,每次6 min。然后与PBST稀释的二抗在室温下孵育1 h。用PBST洗膜5次,每次6 min。将ECL A、B液按体积1꞉1混合后均匀滴加在膜上,设置曝光时间及曝光类型并曝光。保存并导出图片,用图像分析软件Image J对图像进行灰度分析。

1.9. 统计学处理

采用GraphPad Prism 8.0及SPSS 23.0统计学软件进行数据分析和图像绘制。2组比较采用独立样本t检验,3组或3组以上比较采用单因素方差分析,若组间差异有统计学意义,采用Bonferroni检验进行多重比较。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结 果

2.1. 大鼠视网膜Müller细胞的鉴定及诱导去分化

免疫荧光检测结果显示待鉴定细胞中Müller细胞的特征标志物GLAST和GS具有较强的表达(图1A)。PCR琼脂糖凝胶电泳结果显示:待鉴定细胞中GLAST和GS的条带清晰,表达呈阳性,而rhodopsin(视杆细胞标志物)、PKC(双极细胞标志物)、Calbindin(水平细胞标志物)、Nestin(视网膜干细胞标志物)、Thy1.1(RGC标志物)、Pax6(视网膜干细胞标志物)、HPC-1(无长突细胞标志物)和Brn-3b(RGC标志物)无明显条带,表达呈阴性(图1B)。以上结果表明,所鉴定细胞为高纯度的Müller细胞,未被其他视网膜细胞污染。

图1.

大鼠视网膜Müller细胞的鉴定及诱导去分化

Figure 1 Identification and dedifferentiation induction of rat retinal Müller cells

A: Immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression of glutamate/aspartate transporter (GLAST) and glutamate synthase (GS) in the cells. Scale bar: 50 μm. B: PCR assay was performed to detect the expression of GLAST, rhodopsin, protein kinase C (PKC), GS, Calbindin, Nestin, Thy1.1, Pax6, hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC)-1 and Brn-3b in the cells. C: PCR assay was performed to detect the expression of Nestin and Pax6 in Müller cells treated with or without epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2). D: Western blotting was performed to detect the expression of Nestin and Pax6 in Müller cells treated with or without EGF and FGF2. E: Immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression of Nestin in Müller cells treated with or without EGF and FGF2. Scale bar: 50 μm.

PCR和蛋白质印迹法结果显示:未经EGF和FGF2处理的Müller细胞Nestin和Pax6的表达呈阴性,而经EGF和FGF2诱导后的Müller细胞Nestin和Pax6的表达呈阳性(图1C、1D)。免疫荧光法检测经EGF和FGF2诱导去分化后的Müller细胞内Nestin具有较强的阳性表达(图1E)。以上结果表明EGF和FGF2处理成功将Müller细胞定向诱导去分化为视网膜干细胞。

2.2. Trim9促进大鼠视网膜Müller细胞定向分化为RGC

构建Trim9过表达慢病毒PGC-FU-Trim9-GFP,感染Müller细胞诱导去分化而来的视网膜干细胞中,荧光显微镜下观察和流式细胞术评估病毒感染效率。病毒感染预实验结果显示MOI=50时感染效率最高(图2)。因此,后续研究采用MOI=50来感染由Müller细胞诱导去分化而来的视网膜干细胞,构建Trim9过表达的视网膜干细胞稳定细胞株。

图2.

荧光显微镜观察和流式细胞术评估病毒感染效率

Figure 2 Efficiency of viral infection was observed using fluoresence microscopy and assessed by flow cytometry asssay

A: Fluorescence microscopy was used to observe the efficiency of viral infection. B: Flow cytometry assay was performed to test the efficiency of viral infection.

PCR检测结果显示:与Control和OE-NC组相比,OE-Trim9组细胞内Brn-3b、rhodopsin、HPC-1、PKC、Calbindin和Thy1.1 mRNA的表达均显著上调;而Nestin的mRNA表达下调,且随时间延长下调趋势更显著(图3A)。此外,在Control、OE-NC和OE-Trim9组细胞中均未检出GLAST和GS的蛋白质表达(图3B)。

图3.

PCR和蛋白质印迹法检测Trim9对大鼠视网膜Müller细胞定向分化为神经节细胞的调控作用

Figure 3 Regulation of Trim9 on the directional differentiation of rat retinal Müller cells into ganglion cells was detected by PCR and Western blotting

A: PCR assay was used to detect the mRNA expression of Brn-3b, rhodopsin, HPC-1, protein kinase C (PKC), Calbindin, Thy1.1, and Nestin in Trim9 overexpressing retinal stem cells after brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), retinoic acid (RA) and DMEM/F12 treatment for 5, 7 or 14 days. B: Western blotting was used to test the protein expression of Brn-3b, GLAST, rhodopsin, HPC-1, PKC, Calbindin, Thy1.1, glutamine synthetase (GS), and Nestin in Trim9 overexpressing retinal stem cells after BDNF, RA and DMEM/F12 treatment for 5, 7 or 14 days. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

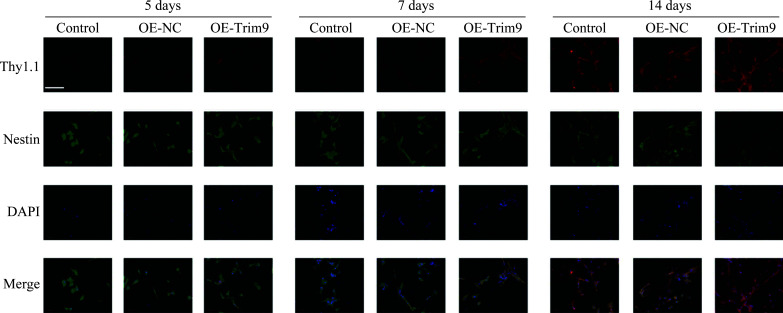

免疫荧光检测结果显示:与Control和OE-NC组相比,感染OE-Trim9病毒的视网膜干细胞中Thy1.1的阳性表达更强,且随诱导时间增长而增强,而Nestin的阳性表达更弱,且随时间延长而减弱。经5、7和14 d诱导处理后的OE-Trim9组细胞中Thy1.1阳性细胞明显增多(图4)。

图4.

免疫荧光法检测Trim9对大鼠视网膜Müller细胞定向分化为神经节细胞的调控作用

Figure 4 Regulation of Trim9 on the directional differentiation of rat retinal Müller cells into ganglion cells was detected by immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed to detect the expression of Thy1.1 and Nestin in Trim9 overexpressing retinal stem cells after brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), retinoic acid (RA), and DMEM/F12 treatment for 5, 7 or 14 days. Scale bar: 100 μm.

3. 讨 论

视网膜Müller细胞是具有视网膜干细胞潜力的神经胶质细胞,可为视网膜损伤的细胞替代疗法提供丰富的细胞来源[24]。在脊椎动物的视网膜发生过程中,视网膜的6种主要细胞类型均来源于一个共同的多能祖细胞群[46-48]。转录因子Pax6的表达在眼发育和视网膜形态发生过程中必不可少[48-49],也是公认的视网膜祖细胞标志物[32, 44, 48]。Nestin蛋白是神经元分化的早期标志物[50],已被广泛用作不同环境中神经系统祖细胞的标志物[51-54]。本研究通过EGF和FGF2处理,成功地将体外培养的Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,主要表现为标志物Nestin和Pax6的高度表达,进一步验证了Müller细胞的视网膜干细胞潜能。

EGF是一种影响多种细胞类型的生长和分化功能的表皮生长因子[55],可诱导成人胰岛细胞、胎儿心室心肌细胞以及脊髓组织中星形胶质细胞的去分化[56-58]。FGF2也可诱导多种细胞的去分化,包括成熟的少突胶质细胞、人胚肾细胞(human embryonic kidney cell,HEK细胞)、人表皮角质形成细胞和血管平滑肌细胞[59-62]。EGF和FGF2还是干细胞培养基的关键成分,对维持干细胞未分化状态至关重要[63]。此外,对EGF和FGF2的反应性是神经祖细胞的基本特性[64],且EGF和FGF2被证明可刺激视网膜神经细胞的增殖[65]。因此,EGF和FGF2具有诱导视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞的能力。曾琦等[33]曾在含有N2、FGF2和EGF的DMEM/F12培养基中将大鼠视网膜Müller细胞成功去分化为Nestin呈阳性的视网膜干细胞,本研究也进一步验证了EGF和FGF2对视网膜Müller细胞的去分化诱导作用,为视网膜干细胞的来源提供了可靠依据。

Trim9在正常的大脑皮层和海马中高度表达,而在记忆丧失的患者大脑中低表达[38],表明Trim9在调节神经发育方面具有重要作用。另外,Trim9在发育的RGC中表达,而在无长突细胞中完全不表达,说明其具有特异性调节RGC发育的潜能[43]。本研究采用含RA和BDNF的DMEM/F12培养基的序贯培养方式,诱导过表达Trim9的Müller细胞去分化为干细胞,并进一步向神经元和神经胶质细胞分化。结果发现Trim9基因有效促进视网膜干细胞向RGC、双极细胞、无长突细胞、视杆细胞和水平细胞分化,其中分化为RGC的比例更高,表现为过表达Trim9的细胞中Thy1.1的阳性表达更强,Nestin的阳性表达更弱,说明Trim9的过表达促进了由视网膜Müller细胞去分化而来的干细胞向RGC定向分化。

为了恢复视觉功能,RGC需与视网膜中的突触前无长突细胞和双极细胞整合,使其轴突沿着受损的视神经生长,并正确连接外侧膝状体核和大脑的其他区域[66]。迄今为止,RGC移植后的视网膜神经整合仍然受到限制[67]。Netrin-1由视神经盘中与RGC轴突紧密接触的神经上皮细胞表达[68],而Trim9可通过调控Netrin-1在神经元分支和轴突引导方面发挥重要作用[39, 42]。Netrin-1信号促进神经元系统中的神经元树枝状结构和突触形成[39, 69],且在视神经盘局部介导轴突引导,其功能丧失可导致视神经发育不全[68]。因此,Netrin-1在Trim9调控的RGC分化和轴突延伸中的作用亦值得进一步探讨。

Math5是早期视网膜神经元分化和细胞周期进程中的必需因子[36, 70-71]。尽管Trim9与Math5显著相关[43],但Trim9是否通过Math5来调控这种定向分化过程尚未明确。后续的研究或许可以Trim9对Math5或Netrin-1的调控作用为切入点,深入探讨Trim9促进视网膜干细胞定向分化为RGC以及促进RGC轴突延伸的分子机制,以寻找将视网膜Müller细胞高效诱导分化为RGC并顺利与视网膜神经整合的更优方案。

综上,本研究成功将视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,且进一步将其定向分化为RGC。本研究验证了视网膜Müller细胞的视网膜干细胞潜力,首次报道了Trim9促进大鼠视网膜Müller细胞去分化为视网膜干细胞,并定向分化为RGC,为过渡到体内实验并进一步研究其调控机制提供了理论依据。

基金资助

湖南省卫生健康委员会科研计划项目(20200757);湖南省自然科学基金(2021JJ30397);湖南省科技厅重点研发项目(2020SK2119)。

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Program of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (20200757), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ30397), and the Hunan Provincial Science and Technology Department Focuses on Research and Development Project (2020SK2119), China.

利益冲突声明

作者声称无任何利益冲突。

作者贡献

李金香 研究选题和设计,实验操作,论文撰写;曾琦 研究选题和设计,数据采集及统计分析,论文修改。所有作者阅读并同意最终的文本。

原文网址

http://xbyxb.csu.edu.cn/xbwk/fileup/PDF/2023101561.pdf

参考文献

- 1. Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review[J]. JAMA, 2014, 311(18): 1901-1911. 10.1001/jama.2014.3192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kang JM, Tanna AP. Glaucoma[J]. Med Clin N Am, 2021, 105(3): 493-510. 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. 张青, 曹凯, 康梦田, 等. 青光眼临床诊疗若干问题问卷调查(2016年)[J]. 中华眼科杂志, 2017, 53(2): 115-120. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4081.2017.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; ZHANG Qing, CAO Kai, KANG Mengtian, et al. The questionnaire survey on glaucoma diagnosis and treatment in China (2016)[J]. Chinese Journal of Ophthalmology, 2017, 53(2): 115-120. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4081.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. 韩冰, 吴志鸿. 青光眼数据库在临床的应用及现状[J]. 中国实用眼科杂志, 2016, 34(11): 1137-1139. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-4443.2016.11.004. 27824848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]; HAN Bing, WU Zhihong. Clinical application and present situation of glaucoma database[J]. Chinese Journal of Practical Ophthalmology, 2016, 34(11): 1137-1139. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-4443.2016.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuster AK, Erb C, Hoffmann EM, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma[J]. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2020, 117(13): 225-234. 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jonas JB, Aung T, Bourne RR, et al. Glaucoma[J]. Lancet, 2017, 390(10108): 2183-2193. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31469-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramdas WD, Wolfs RC, Hofman A, et al. Ocular perfusion pressure and the incidence of glaucoma: real effect or artifact? The Rotterdam Study[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2011, 52(9): 6875-6881. 10.1167/iovs.11-7376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ekström C. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: a population-based 20-year follow-up study[J]. Acta Ophthalmol, 2012, 90(4): 316-321. 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Le A, Mukesh BN, McCarty CA, et al. Risk factors associated with the incidence of open-angle glaucoma: the visual impairment project[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2003, 44(9): 3783-3789. 10.1167/iovs.03-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Czudowska MA, Ramdas WD, Wolfs RC, et al. Incidence of glaucomatous visual field loss: a ten-year follow-up from the Rotterdam Study[J]. Ophthalmology, 2010, 117(9): 1705-1712. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, et al. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial[J]. Arch Ophthalmol, 2002, 120(10): 1268-1279. 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garway-Heath DF, Crabb DP, Bunce C, et al. Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2015, 385(9975): 1295-1304. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erb C. Functional disorders in the chronological progression of glaucoma[J]. Ophthalmologe, 2015, 112(5): 402-409. 10.1007/s00347-015-0005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stern JH, Tian YZ, Funderburgh J, et al. Regenerating eye tissues to preserve and restore vision[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2018, 23(3): 453. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shen YN. Stem cell therapies for retinal diseases: from bench to bedside[J]. J Mol Med, 2020, 98(10): 1347-1368. 10.1007/s00109-020-01960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mandai M, Watanabe A, Kurimoto Y, et al. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration[J]. N Engl J Med, 2017, 376(11): 1038-1046. 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su ZD, Chen JJ, Qiu Y, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells: the primary innate immunocytes in the olfactory pathway to engulf apoptotic olfactory nerve debris[J]. Glia, 2013, 61(4): 490-503. 10.1002/glia.22450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dai C, Khaw PT, Yin ZQ, et al. Olfactory ensheathing cells rescue optic nerve fibers in a rat glaucoma model[J]. Transl Vis Sci Technol, 2012, 1(2): 3. 10.1167/tvst.1.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yuan F, Wang MW, Jin KX, et al. Advances in regeneration of retinal ganglion cells and optic nerves[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(9): 4616. 10.3390/ijms22094616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tropepe V, Coles BLK, Chiasson BJ, et al. Retinal stem cells in the adult mammalian eye[J]. Science, 2000, 287(5460): 2032-2036. 10.1126/science.287.5460.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharma R, Khristov V, Rising A, et al. Clinical-grade stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium patch rescues retinal degeneration in rodents and pigs[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2019, 11(475): eaat5580. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat5580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Costa LA, Eiro N, Fraile M, et al. Functional heterogeneity of mesenchymal stem cells from natural niches to culture conditions: implications for further clinical uses[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2021, 78(2): 447-467. 10.1007/s00018-020-03600-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Vecino E, Rodriguez FD, Ruzafa N, et al. Glia-neuron interactions in the mammalian retina[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2016, 51: 1-40. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bringmann A, Pannicke T, Grosche J, et al. Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina[J]. Prog Retin Eye Res, 2006, 25(4): 397-424. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fischer AJ, Reh TA. Potential of Müller glia to become neurogenic retinal progenitor cells[J]. Glia, 2003, 43(1): 70-76. 10.1002/glia.10218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bernardos RL, Barthel LK, Meyers JR, et al. Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Müller glia that function as retinal stem cells[J]. J Neurosci, 2007, 27(26): 7028-7040. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1624-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ooto S, Akagi T, Kageyama R, et al. Potential for neural regeneration after neurotoxic injury in the adult mammalian retina[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2004, 101(37): 13654-13659. 10.1073/pnas.0402129101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fischer AJ, Bongini R. Turning Müller glia into neural progenitors in the retina[J]. Mol Neurobiol, 2010, 42(3): 199-209. 10.1007/s12035-010-8152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fimbel SM, Montgomery JE, Burket CT, et al. Regeneration of inner retinal neurons after intravitreal injection of ouabain in zebrafish[J]. J Neurosci, 2007, 27(7): 1712-1724. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5317-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abrahan CE, Insua MF, Politi LE, et al. Oxidative stress promotes proliferation and dedifferentiation of retina glial cells in vitro[J]. J Neurosci Res, 2009, 87(4): 964-977. 10.1002/jnr.21903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Das AV, Mallya KB, Zhao X, et al. Neural stem cell properties of Müller glia in the mammalian retina: regulation by Notch and Wnt signaling[J]. Dev Biol, 2006, 299(1): 283-302. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lawrence JM, Singhal S, Bhatia B, et al. MIO-M1 cells and similar muller glial cell lines derived from adult human retina exhibit neural stem cell characteristics[J]. Stem Cells, 2007, 25(8): 2033-2043. 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. 曾琦, 夏晓波. 体外诱导大鼠视网膜Müller细胞向神经节细胞定向分化的研究[J]. 中华眼科杂志, 2010, 46(7): 615-620. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4081.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ZENG Qi, XIA Xiaobo. Study on the differentiation of retinal ganglion cells from rat Müller cells in vitro[J]. Chinese Journal of Ophthalmology, 2010, 46(7): 615-620. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0412-4081.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Singhal S, Bhatia B, Jayaram H, et al. Human Müller glia with stem cell characteristics differentiate into retinal ganglion cell (RGC) precursors in vitro and partially restore RGC function in vivo following transplantation[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2012, 1(3): 188-199. 10.5966/sctm.2011-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guimarães RPM, Landeira BS, Coelho DM, et al. Evidence of Müller glia conversion into retina ganglion cells using Neurogenin2[J]. Front Cell Neurosci, 2018, 12: 410. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brown NL, Patel S, Brzezinski J, et al. Math5 is required for retinal ganglion cell and optic nerve formation[J]. Development, 2001, 128(13): 2497-2508. 10.1242/dev.128.13.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lust K, Sinn R, Pérez Saturnino A, et al. De novo neurogenesis by targeted expression of atoh7 to Müller glia cells[J]. Development, 2016, 143(11): 1874-1883. 10.1242/dev.135905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tanji K, Kamitani T, Mori F, et al. TRIM9, a novel brain-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, is repressed in the brain of Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies[J]. Neurobiol Dis, 2010, 38(2): 210-218. 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Winkle CC, McClain LM, Valtschanoff JG, et al. A novel Netrin-1-sensitive mechanism promotes local SNARE-mediated exocytosis during axon branching[J]. J Cell Biol, 2014, 205(2): 217-232. 10.1083/jcb.201311003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li Y, Chin LS, Weigel C, et al. Spring, a novel RING finger protein that regulates synaptic vesicle exocytosis[J]. J Biol Chem, 2001, 276(44): 40824-40833. 10.1074/jbc.M106141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Winkle CC, Olsen RH, Kim H, et al. Trim9 deletion alters the morphogenesis of developing and adult-born hippocampal neurons and impairs spatial learning and memory[J]. J Neurosci, 2016, 36(18): 4940-4958. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3876-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Menon S, Boyer NP, Winkle CC, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM9 is a filopodia off switch required for netrin-dependent axon guidance[J]. Dev Cell, 2015, 35(6): 698-712. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chowdhury R, Laboissonniere LA, Wester AK, et al. The Trim family of genes and the retina: expression and functional characterization[J/OL]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(9): e0202867[2023-02-17]. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen MF, Chen Q, Sun XR, et al. Generation of retinal ganglion-like cells from reprogrammed mouse fibroblasts[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2010, 51(11): 5970. 10.1167/iovs.09-4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Encinas M, Iglesias M, Liu Y, et al. Sequential treatment of SH-SY5Y cells with retinoic acid and brain-derived neurotrophic factor gives rise to fully differentiated, neurotrophic factor-dependent, human neuron-like cells[J]. J Neurochem, 2000, 75(3): 991-1003. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Turner DL, Cepko CL. A common progenitor for neurons and glia persists in rat retina late in development[J]. Nature, 1987, 328(6126): 131-136. 10.1038/328131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turner DL, Snyder EY, Cepko CL. Lineage-independent determination of cell type in the embryonic mouse retina[J]. Neuron, 1990, 4(6): 833-845. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Marquardt T, Ashery-Padan R, Andrejewski N, et al. Pax6 is required for the multipotent state of retinal progenitor cells[J]. Cell, 2001, 105(1): 43-55. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Halder G, Callaerts P, Gehring WJ. Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila [J]. Science, 1995, 267(5205): 1788-1792. 10.1126/science.7892602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RDG. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein[J]. Cell, 1990, 60(4): 585-595. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dahlstrand J, Lardelli M, Lendahl U. Nestin mRNA expression correlates with the central nervous system progenitor cell state in many, but not all, regions of developing central nervous system[J]. Dev Brain Res, 1995, 84(1): 109-129. 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00162-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kukekov VG, Laywell ED, Thomas LB, et al. A nestin-negative precursor cell from the adult mouse brain gives rise to neurons and glia[J]. Glia, 1997, 21(4): 399-407. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mayer EJ, Hughes EH, Carter DA, et al. Nestin positive cells in adult human retina and in epiretinal membranes[J]. Br J Ophthalmol, 2003, 87(9): 1154-1158. 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bernal A, Arranz L. Nestin-expressing progenitor cells: function, identity and therapeutic implications[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2018, 75(12): 2177-2195. 10.1007/s00018-018-2794-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Stoscheck CM, King Jr LE. Functional and structural characteristics of EGF and its receptor and their relationship to transforming proteins[J]. J Cell Biochem, 1986, 31(2): 135-152. 10.1002/jcb.240310206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hanley SC, Assouline-Thomas B, Makhlin J, et al. Epidermal growth factor induces adult human islet cell dedifferentiation[J]. J Endocrinol, 2011, 211(3): 231-239. 10.1530/JOE-11-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goldman B, Mach A, Wurzel J. Epidermal growth factor promotes a cardiomyoblastic phenotype in human fetal cardiac myocytes[J]. Exp Cell Res, 1996, 228(2): 237-245. 10.1006/excr.1996.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Liu XY, Li CH, Li J, et al. EGF signaling promotes the lineage conversion of astrocytes into oligodendrocytes[J]. Mol Med, 2022, 28(1): 50. 10.1186/s10020-022-00478-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grinspan JB, Stern JL, Franceschini B, et al. Trophic effects of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on differentiated oligodendroglia: a mechanism for regeneration of the oligodendroglial lineage[J]. J Neurosci Res, 1993, 36(6): 672-680. 10.1002/jnr.490360608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. 孙晓艳, 刘惠玲, 付小兵. bFGF诱导表皮细胞去分化形成短暂扩充细胞[J]. 南方医科大学学报, 2010, 30(9): 2041-2046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; SUN Xiaoyan, LIU Huiling, FU Xiaobing. Dedifferentiation of epidermal cells into transit amplifying cells induced by bFGF[J]. Journal of Southern Medical University, 2010, 30(9): 2041-2046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sun XY, Fu XB, Han WD, et al. Dedifferentiation of human terminally differentiating keratinocytes into their precursor cells induced by basic fibroblast growth factor[J]. Biol Pharm Bull, 2011, 34(7): 1037-1045. 10.1248/bpb.34.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tsuji-Tamura K, Tamura M. Basic fibroblast growth factor uniquely stimulates quiescent vascular smooth muscle cells and induces proliferation and dedifferentiation[J]. FEBS Lett, 2022, 596(13): 1686-1699. 10.1002/1873-3468.14345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Soeda A, Inagaki A, Oka N, et al. Epidermal growth factor plays a crucial role in mitogenic regulation of human brain tumor stem cells[J]. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(16): 10958-10966. 10.1074/jbc.M704205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kitchens DL, Snyder EY, Gottlieb DI. FGF and EGF are mitogens for immortalized neural progenitors[J]. J Neurobiol, 1994, 25(7): 797-807. 10.1002/neu.480250705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Anchan RM, Reh TA, Angello J, et al. EGF and TGF-alpha stimulate retinal neuroepithelial cell proliferation in vitro[J]. Neuron, 1991, 6(6): 923-936. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90233-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Moore DL, Goldberg JL. Four steps to optic nerve regeneration[J]. J Neuro Ophthalmol, 2010, 30(4): 347-360. 10.1097/wno.0b013e3181e755af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang KY, Tuffy C, Mertz JL, et al. Role of the internal limiting membrane in structural engraftment and topographic spacing of transplanted human stem cell-derived retinal ganglion cells[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2021, 16(1): 149-167. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Deiner MS, Kennedy TE, Fazeli A, et al. Netrin-1 and DCC mediate axon guidance locally at the optic disc: loss of function leads to optic nerve hypoplasia[J]. Neuron, 1997, 19(3): 575-589. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Barallobre MJ, Del Río JA, Alcántara S, et al. Aberrant development of hippocampal circuits and altered neural activity in netrin 1-deficient mice[J]. Development, 2000, 127(22): 4797-4810. 10.1242/dev.127.22.4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kay JN, Finger-Baier KC, Roeser T, et al. Retinal ganglion cell genesis requires lakritz, a Zebrafish atonal homolog[J]. Neuron, 2001, 30(3): 725-736. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Le TT, Wroblewski E, Patel S, et al. Math5 is required for both early retinal neuron differentiation and cell cycle progression[J]. Dev Biol, 2006, 295(2): 764-778. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]