Abstract

Cryptosporidium species cause watery diarrhea in several vertebrate hosts, including humans. Most apparently, immunocompetent-infected individuals remain asymptomatic, whereas immunocompromised may develop severe or chronic cryptosporidiosis. We report here the case of a 6-year-old girl undergoing chemotherapy for Burkitt lymphoma who experienced multiple episodes of watery diarrhea during her hospital stay. Microscopic examination of her stool sample revealed oocysts of Cryptosporidium species. The rapid immunochromatographic test was also positive for Cryptosporidium species. She was treated with nitazoxanide for 3 weeks, which failed to provide both clinical improvement and parasitological clearance. This case highlights the importance of treatment failure in human cryptosporidiosis.

Keywords: Burkitt lymphoma, Cryptosporidium species, nitazoxanide, refractory

THE STUDY

Cryptosporidiosis, a watery diarrheal disease that infects a wide range of vertebrates, is caused by different species of Cryptosporidium, an intestinal coccidian parasite belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa.[1,2] The first human case of cryptosporidiosis was reported in 1976 in an immunosuppressed host.[2] Over 40 species of Cryptosporidium are known to infect vertebrate hosts, of which Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis are the most common species that cause human infections.[3] Cryptosporidium species are ubiquitous and have been increasingly implicated in the pathogenesis of diarrhea over the years.[4] The consumption of contaminated food or water, person-to-person spread, and zoonotic transmission may infect humans.[5] Although more common in immunocompromised individuals such as people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cancer, infection is also increasingly being reported among immunocompetent individuals. The disease may range from generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals to more severe and chronic in immunocompromised patients.[2] Large-scale outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis have been documented globally, which may have considerable effects on health and the economy.[3,6] Thick-walled oocysts, the infective stage, are intermittently shed in the faces of the infected hosts.[7] Management of cryptosporidiosis varies depending on the infected host (s), and the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug is nitazoxanide (NTZ), whose efficacy is also variable and not wholly adequate.[6,8] There is a growing concern regarding increasing resistance to already limited therapeutic options for treating cryptosporidiosis and the need for newer approved drugs.

On December 30, 2022, a 6-year-old girl was referred to the Medical Oncology Department of the National Cancer Institute of our tertiary care hospital with fever, myalgia, and chills following cancer chemotherapy. She was admitted, and after the initial workup, a clinical diagnosis of febrile neutropenia was made, and she was treated with antibiotics.

The patient was previously treated in another hospital, where she had undergone an exploratory laparotomy for an ileocecal mass. Histological examination of the mass so obtained had suggestive features of malignant B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Subsequent repeat diagnostic workup was confirmatory of high-grade B-cell lymphoma that was positive for leukocyte common antigen, CD10 (weak), CD20, CD79, and Ki-67 (80%–90%). A diagnosis of Burkitt lymphoma was made. The patient was under treatment according to the Berlin–Frankfurt–Münster-95 (BFM-95) protocol since September 8, 2022, and had undergone multiple treatment cycles with chemotherapeutic agents such as methotrexate, cytarabine, etoposide, ifosfamide, and vincristine. The patient also completed the CC2 cycle with rituximab. During chemotherapy, she also suffered from multiple episodes of diarrhea, fever, idiopathic hypertension, and seizures, which were managed with appropriate medications.

The patient developed three to four episodes of passing loose stools during the hospital stay. Diarrhea was of acute onset and was associated with pain in the abdomen of moderate intensity. The pain was subsiding by passing stool and not by any medications. Upon clinical evaluation/examination, she was stable with no signs of dehydration. On palpation, the abdomen was soft and nontender. Examination of other systems revealed no significant abnormalities. Ultrasound examination of kidneys, ureters, and bladder was normal. Her complete hemogram revealed severe anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio were raised. She also tested negative for HIV infection.

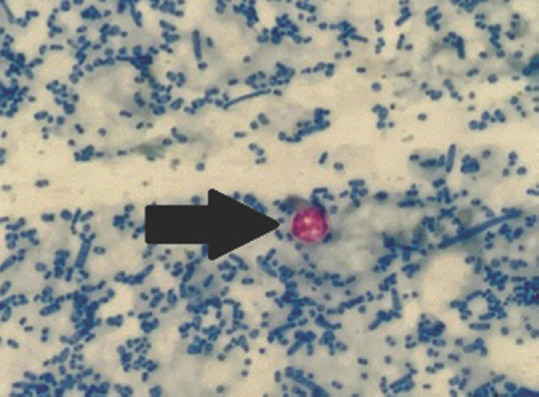

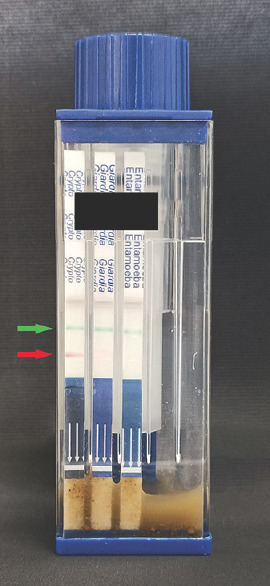

The patient’s stool samples were received for the diagnostic workup for diarrhea. On gross examination, the stool was greenish in color, loose in consistency, without mucous, blood, or parasitic elements visible under the naked eye. Microscopic examination of stool revealed small round refractile structures at ×400. Modified acid-fast stained smears showed round, approximately 4–6 μm in size, nonuniformly stained, acid-fast forms suggestive of oocysts of Cryptosporidium species [Figure 1]. The stool specimen tested positive for Cryptosporidium species [Figure 2] by rapid immunochromatographic test (ICT) (Vitassay, Huesca, Spain). Aerobic culture from stool did not yield any pathogenic organisms. Anaerobic culture and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were negative for Clostridioides difficile and its toxin, respectively.

Figure 1.

Oocyst of Cryptosporidium species (black arrow) in modified acid-fast stained smear of stool specimen (×400)

Figure 2.

Rapid immunochromatographic test showing positive test band for Cryptosporidium species (red arrow) and control band (green arrow)

The patient was started on NTZ 200 mg orally, twice daily for 3 days. Diarrhea did not subside. Follow-up stool microscopy was carried out for 3 weeks and was positive for oocysts Cryptosporidium species. Azithromycin was added in anticipation of the failure of NTZ monotherapy. The patient’s condition started worsening, and she developed altered sensorium and septic shock, which was refractory to optimal fluid, vasoactive, inotrope support, and anti-Cryptosporidium treatment. Unfortunately, the patient succumbed to her illness after 4 weeks.

Our patient had multiple episodes of diarrhea along with pain in the abdomen and mild fever with an underlying condition of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Various studies have suggested the role of C. parvum in causing cancer by inducing cytoskeleton remodeling, actin polymerization, and activating proto-oncogenes like c-Src.[9,10,11] In the present case, cancer coupled with therapeutic immunosuppression looks to be the risk factor for acquiring the Cryptosporidium infection. However, the possibility of carcinogenesis linked to chronic cryptosporidiosis cannot be ruled out.

In the present case, the organism was identified with the help of microscopy (using modified Ziehl–Neelsen staining) and a rapid ICT (Vitassay, Huesca, Spain). Although conventional microscopy has relatively lower sensitivity, it remains the most commonly performed test, owing to its lower cost.[12] Various rapid kits based on immunochromatography are available to detect single or combined antigens of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species and Entamoeba histolytica.[13] These rapid tests offer a shorter turn-around time and a comparable sensitivity and specificity to previously available tests.[7] El-Moamly and El-Sweify, in their study, showed the sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of ICT to be 96%, 98%, and 97%, respectively.[14] Other methods available are polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) test. Still, these are relatively expensive and are often a constraint to use in routine diagnosis and more so in resource-limited settings.

In 2004, the FDA approved NTZ, a nitrothiazole benzamide compound, to treat cryptosporidiosis for all individuals aged 1 year or more. A dose of 200 mg two times daily for 3 days is recommended for immunocompetent patients aged 4–11 years. In a double-blind placebo-control study by Rossignol et al., AIDS patients with Cryptosporidium-associated diarrhea were effectively managed with NTZ for up to 28 days.[15] Our patient received oral NTZ for 18 days but did not show significant improvement in diarrheal symptoms or parasitological clearance of infection. The rate of clinical cure by NTZ has been reported to be 72%–80% and parasite clearance up to 60%–75%.[8] A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reported that out of 49 patients in the NTZ treatment group, 39 (80%) showed clinical improvement after 7 days, compared with 20 (41%) of 49 in the placebo group.[16] Furthermore, 33 (67%) of 49 patients in the NTZ group had no oocysts in either of the two posttreatment stool samples, compared with 11 (22%) of 49 in the placebo group.[16] Nevertheless, NTZ has not been approved in immunodeficient patients due to unsatisfactory performance in placebo-controlled studies.[8] A study with 100 patients (50 HIV seropositives and 50 HIV seronegatives) from Zambia showed higher clinical improvement and parasitological clearance in seronegative patients on NTZ than on placebo. In contrast, the efficacy of NTZ was inferior to placebo in seropositive individuals.[17] Another study from Egypt, which assessed the effectiveness of NTZ on clearing the oocysts of C. parvum among infected children using PCR techniques, reported that diarrhea was resolved in immunocompetent patients receiving NTZ within 3–5 days. In contrast, it took 21–28 days to be resolved in the immunocompromised group.[18]

Besides NTZ, several other therapeutic agents have also been studied and tried to treat cryptosporidiosis, such as azithromycin, paromomycin, rifaximin, clofazimine, miltefosine, and albendazole.[2] Our patient was started on azithromycin, besides NTZ, because of the failure of monotherapy but had a bad outcome on the same day. Cryptosporidiosis refractory to multiple anti-parasitic drugs has been sparsely mentioned in the literature. A recently published case report from Boston, Massachusetts, described that a patient of lymphoma after chimeric antigen receptors T-cell therapy suffered from the persistent symptom (diarrhea) for 9 months with repeated positivity for Cryptosporidium species in stool examination despite receiving multiple anti-parasitic agents (azithromycin, paromomycin, clofazimine, and rifaximin), including a prolonged course of NTZ.[19]

CONCLUSION

Much awareness is sought among all treating clinicians regarding the lethality of cryptosporidiosis in immunocompromised patients presenting with persistent diarrhea. Routine modified acid-fast staining should be performed for a timely, accurate diagnosis, followed by administering appropriate antimicrobials to prevent complications. There is a need for newer approved antimicrobials for treating complicated refractory cases.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the legal guardian has given consent for images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The guardian understands that name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal the patient’s identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gharpure R, Perez A, Miller AD, Wikswo ME, Silver R, Hlavsa MC. Cryptosporidiosis outbreaks –United States, 2009-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:568–72. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6825a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diptyanusa A, Sari IP. Treatment of human intestinal cryptosporidiosis: A review of published clinical trials. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2021;17:128–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Innes EA, Chalmers RM, Wells B, Pawlowic MC. A one health approach to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2019.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Checkley W, White AC, Jr, Jaganath D, Arrowood MJ, Chalmers RM, Chen XM, et al. Areview of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:85–94. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70772-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Alfy ES, Nishikawa Y. Cryptosporidium species and cryptosporidiosis in Japan: A literature review and insights into the role played by animals in its transmission. J Vet Med Sci. 2020;82:1051–67. doi: 10.1292/jvms.20-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Widmer G, Carmena D, Kváč M, Chalmers RM, Kissinger JC, Xiao L, et al. Update on Cryptosporidium spp.: Highlights from the seventh international Giardia and Cryptosporidium conference. Parasite. 2020;27:14. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2020011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention CC for DC and. CDC – Cryptosporidiosis – Treatment. Atlanta, USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. [[Last accessed on 2023 Nov 03]]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/diagnosis.html . [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention CC for DC and. CDC – Cryptosporidiosis – Treatment. Atlanta, USA: 2021. [[Last accessed on 2023 Nov 03]]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/crypto/treatment.html . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Certad G. Is Cryptosporidium a hijacker able to drive cancer cell proliferation? Food Waterborne Parasitol. 2022;27:e00153. doi: 10.1016/j.fawpar.2022.e00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawant M, Baydoun M, Creusy C, Chabé M, Viscogliosi E, Certad G, et al. Cryptosporidium and colon cancer: Cause or consequence? Microorganisms. 2020;8:1665. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8111665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalantari N, Gorgani-Firouzjaee T, Ghaffari S, Bayani M, Ghaffari T, Chehrazi M. Association between Cryptosporidium infection and cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parasitol Int. 2020;74:101979. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2019.101979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan UM, Pallant L, Dwyer BW, Forbes DA, Rich G, Thompson RC. Comparison of PCR and microscopy for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in human fecal specimens: Clinical trial. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:995–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.995-998.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minak J, Kabir M, Mahmud I, Liu Y, Liu L, Haque R, et al. Evaluation of rapid antigen point-of-care tests for detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium species in human fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:154–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01194-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Moamly AA, El-Sweify MA. Immunocard STAT!Cartridge antigen detection assay compared to microplate enzyme immunoassay and modified Kinyoun's acid-fast staining technique for detection of Cryptosporidium in fecal specimens. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1037–41. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2585-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossignol JF, Hidalgo H, Feregrino M, Higuera F, Gomez WH, Romero JL, et al. A double-'blind'placebo-controlled study of nitazoxanide in the treatment of cryptosporidial diarrhoea in AIDS patients in Mexico. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:663–6. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)90804-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossignol JF, Ayoub A, Ayers MS. Treatment of diarrhea caused by Cryptosporidium parvum: A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Nitazoxanide. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:103–6. doi: 10.1086/321008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amadi B, Mwiya M, Musuku J, Watuka A, Sianongo S, Ayoub A, et al. Effect of nitazoxanide on morbidity and mortality in Zambian children with cryptosporidiosis: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1375–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11401-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atia MM, Fattah MM, Rahman HA, Mohammed FA, Ghandour AM. Assessing the efficacy of nitazoxanide in treatment of cryptosporidiosis using PCR examination. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2016;46:683–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trottier CA, Yen CF, Malvar G, Arnason J, Avigan DE, Alonso CD. Case report: Refractory cryptosporidiosis after CAR T-cell therapy for lymphoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105:651–3. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.21-0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]