Abstract

Primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) affects people all over the world. Circular RNAs are involved in the growth and development of several malignancies and regulate a number of biological processes. However, the roles of has-circ-0009158 in HCC remain unknown. This study explored the expression and associated miRNA-mRNA network of has-circ-0009158 in HCC. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was used to measure the expression of hsa-circ-0009158 in the HCC tissues of 143 patients and four human HCC cell lines. Then, the potential relationship of hsa-circ-0009158 expression with clinical characteristics and prognosis of patients was analyzed using the GO and KEGG databases. Correlated miRNA-mRNA networks were forecasted using the TCGA database and Cytoscape software. The hsa-circ-0009158 expression was significantly upregulated in HCC tissues and cell lines (P<0.001). The multivariate Cox analysis revealed that HCC patients were associated with high hsa-circ-0009158 expression. The bioinformatics analysis screened 1 miRNA, and 248 mRNAs associated with the circRNA in HCC. A pathway analysis suggested that the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) may be linked to the development and growth of HCC tumors. Ten hub genes (MELK, NCAPG, BUB1B, BIRC5, CDCA8, CENPF, BUB1, CDK1, TTK, TPX2) were identified from the PPI network based on the 248 genes. Additionally, the 10 hub genes that were verified had an association between high expression levels and low overall survival rates. As a result, the high expression of hsa-circ-0009158 was found to be a separate risk factor for recurrence and a poor prognosis in HCC patients.

Keywords: Circular RNA, hsa-circ-0009158, hepatocellular carcinoma, recurrence, poor prognosis

Introduction

Based on the Global Cancer Statistics in 2020, cancer of the liver is the sixth most common cancer (approximately 906,000 new cases per year) and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths (approximately 830,000 deaths every year) [1]. HCC is the most common kind of primary liver cancer, accounting for 75%-85% of all cases [1]. Due to the absence of early symptoms, most patients receive their diagnoses when they are in the middle or advanced stages, leading to high incidence and mortality of HCC patients. It is worth noting that owing to the high recurrence rate (5-year recurrence rate of up to 70%), the patient’s long-term survival rate for HCC is not satisfactory [2]. However, none of the molecular biomarkers proposed can be used to predict HCC recurrence or prognosis [3]. It is urgent to identify sensitive molecular biomarkers that are specific to the assessment of the prognosis of HCC.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are presented in a wide range of species [4,5]. In the past, due to the lack of protein-coding function, circRNAs were considered as by-products of mRNA processing related to mis-splicing and thus have been neglected [6,7]. However, subsequent studies have found that circRNAs control a number of biological activities [8,9]. Some circRNAs have been identified as functional biomarkers of HCC, which can influence the development of HCC by controlling a number of biological processes, such as cell division, migration, invasion, apoptosis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, etc. [10-13].

Hsa-circ-0009158 is found on chromosome 8:52546241-62566219, with its corresponding gene symbol Aspartyl/Asparaginyl-hydroxylase (ASPH), which is a member of the -ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family as well as an 86 KD Type II transmembrane protein [14]. ASPH is overexpressed in HCC and can promote the occurrence, proliferation, invasion, and migration of tumor cells by increasing motility and invasiveness, resulting in high recurrence and low survival rate of HCC patients, that has been proven in studies [15,16]. However, no reports are currently available regarding how hsa-circ-0009158 manifests and what it means clinically for the prognosis of HCC.

Therefore, in this research, we want to look into the expression and clinical significance of hsa-circ-0009158 in HCC, and to explore the prediction ability of hsa-circ-0009158 for recurrence and prognosis of HCC patients.

Materials and methods

Data collection

We obtained hepatocellular carcinoma-associated miRNA and mRNA sequencing from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database is available at https://cancergenome.nih.gov. There were 50 matched normal samples and 374 liver cancer samples, totaling 424 total samples.

Patient data and specimens

HCC samples and comparable neighboring normal tissues (>3 cm from the tumor margin) were collected from 143 patients undergoing hepatectomy at the Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The samples were obtained between May 2013 and May 2015. To ensure preservation, all tissues were promptly placed in liquid nitrogen and delivered to the lab within 30 minutes. The HCC diagnosis was confirmed through postoperative pathological examination. Prior to surgery, there had been no chemotherapy, radiation, or immunotherapy for any of the patients. Comprehensive clinical data, including age, gender, presence of cirrhosis, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, tumor characteristics, and TNM stage, were collected. The patients received 60 months of follow-up care, during which valid survival data and information on tumor recurrence were recorded for all patients.

Differential expression analysis

We employed the EdgeR software package to determine the mRNAs and miRNAs that are differentially expressed. To predict the interactions of miRNAs, we utilized the Circular RNA Interactome (https://circinteractome.nia.nih.gov) and data from the TCGA database. Furthermore, we employed TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_80/) and the TCGA database to predict the crucial mRNA targets of the identified miRNAs.

Bioinformatic DEG analysis

We conducted gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Gene and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses using the Cluster Profiler package (version 3.14.3). If the corrected p-value was less than 0.05, the difference was statistically noteworthy.

PPI network construction and topological analysis

To evaluate the interaction of DEmRNAs and build a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, we used the String database (https://string-db.org/). A combined score threshold of greater than 0.4 was applied to determine the interactions in the PPI network. To evaluate the interaction of DEmRNAs and build a PPI network, we used the String database (https://string-db.org/). Finally, we visualized the interactive network using Cytoscape version 3.9.0 software.

Validation of hub genes

We validated the identified hub genes using the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (http://www.proteinatlas.org/). Clinical statistics of the TCGA database were applied for survival analyses of 10 key genes.

Cell culture

Four human HCC cell lines (PLC, Huh7, Hep3B, and SMMC-7721) and one human normal hepatocyte (QSG-7701) were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, USA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin. In a humidified incubator, the cell cultures were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to extract RNA from HCC tumors, surrounding normal tissues, and cells. A Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure the concentration of RNA. Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was performed using the HiScript II Reverse Transcriptase SuperMix with gDNA wiper (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

With the use of the Fast Start Universal SYBR Green Master ROX (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), the expression level of hsa-circ-0009158 was discovered. The primers for hsa-circ-0009158 and GAPDH were as follows (5’-3’): hsa-circ-0009158: GAAGTAAGCATTTTTCCTGTGG (forward), GGGACTGCTGGCTCTGAA (reverse); GAPDH: CAGGAGGCATTGCTGATGAT (forward), GAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT (reverse). The housekeeping gene GAPDH was utilized for internal normalization. The 2-Ct technique was used to examine the data.

Statistical analysis

The data was evaluated statistically using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Each experiment was performed three times. The standard deviation (SD) and the mean are used to present continuous data. One-way ANOVA or the Student’s t-test was used to analyze group differences. Using the chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test, the relationships between clinicopathological traits and hsa-circ-0009158 expression were examined. The curves for overall survival (OS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS), which were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method, and were compared using the log-rank test. Using the Cox proportional hazard regression model, survival analysis was conducted both in a single-factor and multi-factor fashion. If the p-value was less than 0.05, the difference was declared to be significantly different. P values of 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001 were used as the criteria for statistical significance (*, **, ***). Correlations were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The comparisons of gene expression between the cancer and normal groups of samples were carried out using t-tests.

Results

Hsa-circ-0009158 expression is upregulated in HCC tissues

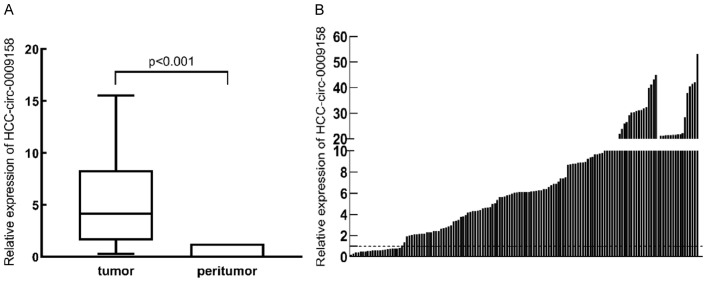

We employed RT-PCR to look at hsa-circ-0009158 expression in HCC tumors and nearby healthy tissues. When compared to the nearby normal tissues, the HCC tissues had a significant overexpression of hsa-circ-0009158, according to the findings (P<0.001; Figure 1A). Besides, the waterfall plot revealed that 85.3% of the HCC tissues had much higher expression of the gene hsa-circ-0009158 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Relative expression of hsa-circ-0009158 in HCC and adjacent normal tissues. A. Hsa-circ-0009158 expression was significantly upregulated in HCC tissues compared with the adjacent normal tissues (P<0.001). B. The waterfall plot showed that hsa-circ-0009158 was significantly and highly expressed in 85.3% of the HCC tissue.

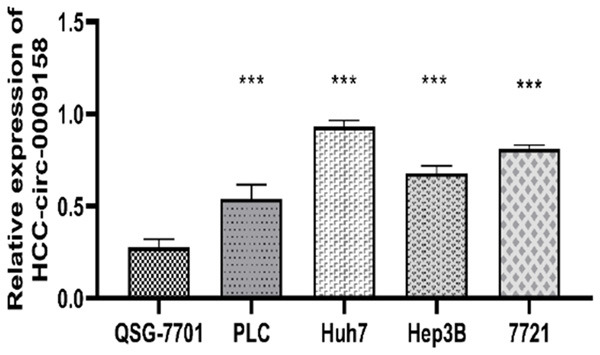

Hsa-circ-0009158 expression is also upregulated in HCC cell lines

To further validation of our findings, we detected the expression levels of hsa-circ-0009158 in HCC cell lines. Naturally, hsa-circ-0009158 was also notably increased in four human HCC cell lines (PLC, Huh7, Hep3B, and SMMC-7721) when compared to the QSG-7701 human normal hepatocyte (P<0.001, Figure 2). Together, our findings support the finding that hsa-circ-0009158 expression exhibited an overexpression pattern in HCC tissues and cells, indicating that it may play a part in promoting the development and spread of HCC.

Figure 2.

Hsa-circ-0009158 expression in HCC cells and normal hepatocyte lines. Hsa-circ-0009158 was significantly up regulated in four HCC cell lines (PLC, Huh7, Hep3B, and SMMC-7721) compared to normal l-hepatocyte QSG-7701 (***P<0.001).

The connection between the hsa-circ-0009158 gene and clinicopathological traits in HCC patients

To understand the impact of hsa-circ-0009158 on the progression of HCC, we investigated how it related to the clinicopathological traits of HCC patients. In our study involving 143 HCC cases, there were 112 males (78.3%) and 31 females (21.7%), aged 54.41 years on average (with a range of 37 to 79 years). Table 1 provides an overview of the clinical features of HCC patients.

Table 1.

Hsa-circ-0009158 expression and clinical characteristics in 143 HCC patients

| Characteristics | Total | Circ-0009158 expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Low (n=71) | High (n=72) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.284 | |||

| <70 | 135 | 69 (0.97) | 66 (0.92) | |

| ≥70 | 8 | 2 (0.03) | 6 (0.08) | |

| Gender | 0.874 | |||

| Male | 112 | 56 (0.79) | 56 (0.78) | |

| Female | 31 | 15 (0.21) | 16 (0.22) | |

| Cirrhosis | 0.172 | |||

| Positive | 104 | 48 (0.68) | 56 (0.78) | |

| Negative | 39 | 23 (0.32) | 16 (0.22) | |

| AFP (ng/mL) | 0.943 | |||

| ≥400 | 60 | 30 (0.42) | 30 (0.42) | |

| <400 | 83 | 41 (0.58) | 42 (0.58) | |

| Tumor diameter | 0.275 | |||

| ≥5 cm | 85 | 39 (0.55) | 46 (0.64) | |

| <5 cm | 58 | 32 (0.45) | 26 (0.36) | |

| Multiple lesions | 0.874 | |||

| Positive | 31 | 15 (0.21) | 16 (0.22) | |

| Negative | 112 | 56 (0.79) | 56 (0.78) | |

| Tumor thrombosis | 0.017* | |||

| Positive | 20 | 5 (0.07) | 15 (0.21) | |

| Negative | 123 | 66 (0.93) | 57 (0.79) | |

| Microvascular invasion | 0.060 | |||

| Positive | 15 | 4 (0.06) | 11 (0.15) | |

| Negative | 128 | 67 (0.94) | 61 (0.85) | |

| TNM stage | 0.813 | |||

| I-II | 96 | 47 (0.66) | 49 (0.68) | |

| III-IV | 47 | 24 (0.34) | 23 (0.32) | |

| Differentiation | 0.000*** | |||

| High/moderate | 126 | 71 (1.00) | 55 (0.76) | |

| Low | 17 | 0 (0.00) | 17 (0.24) | |

| Tumor recurrence | 0.000*** | |||

| Positive | 112 | 44 (0.62) | 68 (0.94) | |

| Negative | 31 | 27 (0.38) | 4 (0.06) | |

Abbreviations: AFP: alpha fetal protein; TNM: tumor-node-metastasis.

P<0.05;

P<0.001.

Based on the median values of relative hsa-circ-0009158 expression, we divided the HCC patients into two groups based on the levels of hsa-circ-0009158 expression: a low-expression group (n=71) or a high-expression group (n=72). According to our findings, patients in the group with high expression of the hsa-circ-0009158 had a considerably greater incidence of tumor thrombosis (P<0.05) and decreased differentiation compared to those in the group with low expression (P<0.001). Additionally, a higher likelihood of tumor recurrence was positively associated with the expression of hsa-circ-0009158 (P<0.001) (Table 1). However, no real relationship was found between hsa-circ-0009158 expression and age, gender, cirrhosis, serum AFP, tumor diameter, microvascular invasion and TNM stage. Therefore, we considered that hsa-circ-0009158 overexpression is linked to unfavorable clinicopathological characteristics and bleak prognosis for those with HCC.

Patients with HCC who have elevated expression of hsa-circ-0009158 have a worse prognosis

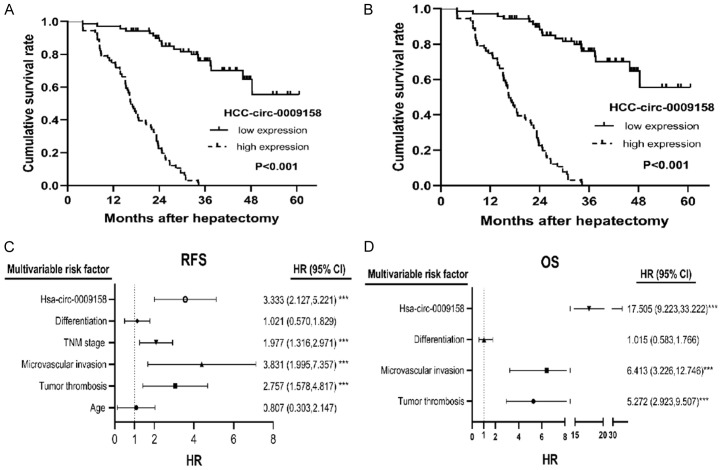

To investigate how HSA-circ-0009158 affects HCC patients’ survival, we conducted a Kaplan-Meier analysis. Figure 3A, 3B demonstrates that patients with HCC patients in the hsa-circ-0009158 high expression group had substantially shorter RFS and OS than those in the low expression group (P<0.001). The low-expression group’s median RFS time was 17.2 months, compared to the median RFS duration of 5.5 months in the high-expression group. To assess the independent prognostic value of hsa-circ-0009158, we conducted a Cox analysis using single and multiple variables. With the findings presented in Table 2. Univariate Cox analysis revealed that age, tumor thrombosis, microvascular invasion, TNM stage, differentiation and has-circ-0009158 were significantly related to RFS. Multivariate Cox analysis validated that tumor thrombosis, microvascular invasion, TNM stage, and hsa-circ-0009158 were independent high-risk factors of RFS (Table 2). Furthermore, univariate Cox analysis revealed variables such as tumor thrombosis, microvascular invasion, differentiation, and hsa-circ-0009158 were associated with OS, while differentiation was not found to be associated with OS in multivariate Cox analysis (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Prognostic significance of hsa-circ-0009158 expression in HCC patients. By multivariate Cox regression analysis, high hsa-circ-0009158 expression was identified as an independent prognostic factor in HCC patients. A. Cumulative recurrence-free survival curves of patients in high and low hsa-circ-0009158 expression groups. B. Cumulative survival curves of patients in high and low hsa-circ-0009158 expression groups. C. Forest plot of the results of multivariate Cox analysis for RFS. D. Forest plots of the results of multivariate Cox analysis for OS.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for hsa-circ-0009158 and survival of HCC patients

| Variables | RFS | OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| Age (≥70 years vs <70 years) | 3.077 (1.308, 7.239)** | 0.807 (0.303, 2.147) | 2.395 (0.957, 5.999) | - |

| Gender (male vs female) | 0.698 (0.451, 1.080) | - | 0.958 (0.592, 1.637) | - |

| Cirrhosis (+ vs -) | 1.322 (0.869, 2.010) | - | 1.329 (0.820, 2.153) | - |

| AFP (≥400 ng/mL vs <400 ng/mL) | 1.397 (0.959, 2.036) | - | 1.052 (0.688, 1.609) | - |

| Tumor diameter (≥5 cm vs <5 cm) | 1.175 (0.801, 1.723) | - | 1.179 (0.766, 1.816) | - |

| Multiple lesions (+ vs -) | 1.491 (0.967, 2.298) | - | 1.154 (0.693, 1.921) | - |

| Tumor thrombosis (+ vs -) | 2.978 (1.778, 4.988)*** | 2.757 (1.578, 4.817)*** | 3.665 (2.137, 6.286)*** | 5.272 (2.923, 9.507)*** |

| Microvascular invasion (+ vs -) | 4.357 (2.430, 7.812)*** | 3.831 (1.995, 7.357)*** | 4.279 (2.336, 7.838)*** | 6.413 (3.226, 12.746)*** |

| TNM stage (I/II vs III/IV) | 1.691 (1.154, 2.479)** | 1.977 (1.316, 2.971)*** | 1.144 (0.733, 1.786) | - |

| Differentiation (low vs high/moderate) | 1.686 (0.999, 2.847)* | 1.021 (0.570, 1.829) | 2.955 (1.713, 5.097)*** | 1.015 (0.583, 1.766) |

| Hsa-circ-0009158 (high vs low) | 3.545 (2.351, 5.346)*** | 3.333 (2.127, 5.221)*** | 14.184 (7.744, 25.980)*** | 17.505 (9.223, 33.222)*** |

Abbreviations: RFS: recurrence-free survival; OS: overall survival; HR: hazard ratio.

P<0.05;

P<0.01;

P<0.001.

Taken together, high has-circ-0009158 expression constituted a separate risk factor for shorter RFS (HR: 3.333, 95% CI: 2.127, 5.221, P<0.001) and poor OS (HR: 17.505, 95% CI: 9.223, 33.222, P<0.001) in HCC patients, as shown in the forest plots (Figure 3C, 3D).

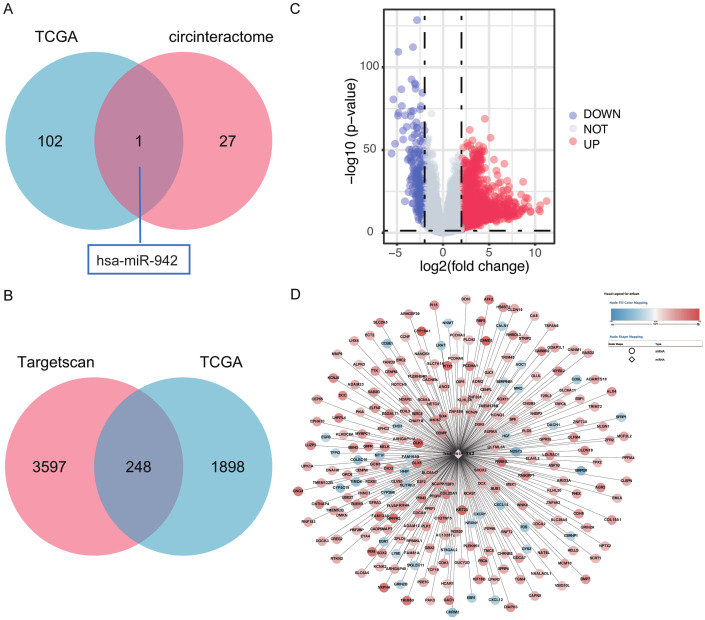

Prediction and analysis of miRNA and mRNA that interacted with the circRNA in HCC

To study whether the downstream mRNA of hsa-circ-0009158 exhibits differential expression and can provide a signal for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) diagnosis, we constructed a network pathway to examine the target genes downstream of hsa-circ-0009158 in a precise manner.

Initially, we utilized CircInteractome and TCGA databases the miRNAs that link to hsa-circ-0009158 are predicted. The intersection of 103 differential miRNAs in the TCGA database and 28 potential miRNAs predicted to bind hsa-circ-0009158 in the CircInteractome database were used to obtain only one miRNA, hsa-miR-942 (Figure 4A). Then, using the TCGA database, we discovered 26,379 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). In contrast to normal HCC tissues, 1,882 of these genes were elevated and 264 were downregulated (Figure 4B). We used the TCGA and TargetScan databases (Figure 4C) to estimate the downstream target genes of hsa-miR-942. Finally, we used Cytoscape (Figure 4D) to build a co-expression network of the miRNA-mRNA relationships.

Figure 4.

Prediction and prognosis of miRNA that interacted with has-circ-0009158. A. Venn diagram displaying the overlaps of miRNA predicted by the intersection of differential miRNAs in TCGA and prediction of in CircInteractome database. B. Volcano map displaying the differential genes present in the TCGA database. C. Venn diagram displaying the overlaps of mRNA predicted by the intersection of differential mRNAs in TCGA and prediction of in TargetScan database. D. Correlation between has-miR-942 and overlaps of mRNAs, the color red signifies a significant level of expression, and the color blue is a low level of expression.

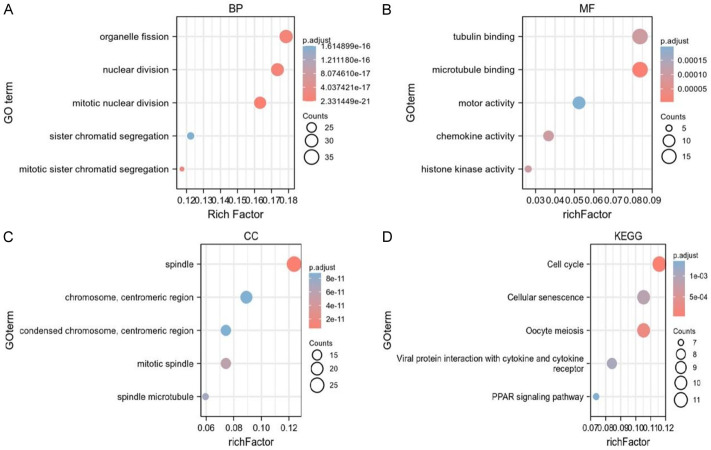

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

To evaluate the deg’s role in the network, we employed GO and KEGG analysis on the 248 overlapping genes. Regarding the GO biological process (BP), we observed enrichment in GO:0140014 mitotic nuclear division and GO:0000280 nuclear division. For cellular components (CC), the top three enriched terms were GO:0005819 spindle, GO:0072686 mitotic spindle, and GO:0000775 chromosome, centromeric region. In terms of molecular function (MF), the enriched terms were GO:0008017 microtubule binding, GO:0015631 tubulin binding, and GO:0003774. Additionally, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed a number of strongly enriched pathways, including the cellular senescence, oocyte meiosis, the PPAR signaling pathway, viral protein interactions with cytokines and cytokine receptors, and the cell cycle are all shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

GO and KEGG pathway analyses of DEGs. Bubble plot of DEGs GO analysis: BP (A), MF (B) and CC (C). (D) Bubble maps depicting the top 5 signaling pathways in the KEGG enrichment analysis of differential genes.

Reconstruction of miRNA-mRNA in sub-network

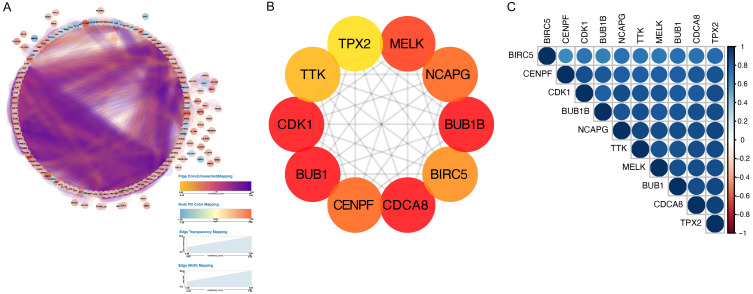

We inputted the 248 differentially expressed genes into the String database to retrieve the gene interactions. Using Cytoscape software, we created a PPI network diagram (Figure 6A) based on this information. In order to further study the intersection of differential genes, the cytoHubba app and MCC algorithm, which is a topological algorithm, were used to generate sub network and then obtained the top 10 key genes with the strongest interaction (Figure 6B). The top ten hub genes were Maternal Embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK), NCAPG stands for non-structural maintenance of the condensin I complex subunit G of chromosomes, budding uninhibited by benzimidazole 1B (BUB1B), Baculovirus IAP repeat containing 5 (BIRC5), cell cycle division associated 8 (CDAC8), centromere binding protein F (CENPF), budding uninhibited by benzimidazole 1 (BUB1), Cyclindependent kinase 1 (CDK1), threonine tyrosine kinase (TTK). Then corplot was used to verify the correlation among the 10 top genes (Figure 6C). There was a strong correlation between these 10 genes. Both methods yielded consistent results.

Figure 6.

The PPI network is constructed based on DEmRNAs in cytoscape. A. PPI network of all DEGs, the color of nodes stands for the expression of the gene, dark orange signifies high expression, and blue colors suggest that a gene is expressed at low levels. Edges stand for the relevance of two genes to each other, dark purple represents a high level of correlation, and orange indicates a weak correction margin. B. The top 10 genes are ordered by the approaches of MCC, darker red means higher correlated genes. C. Corplot of the top 10 genes in TCGA, the blue color implies a higher degree of correlation.

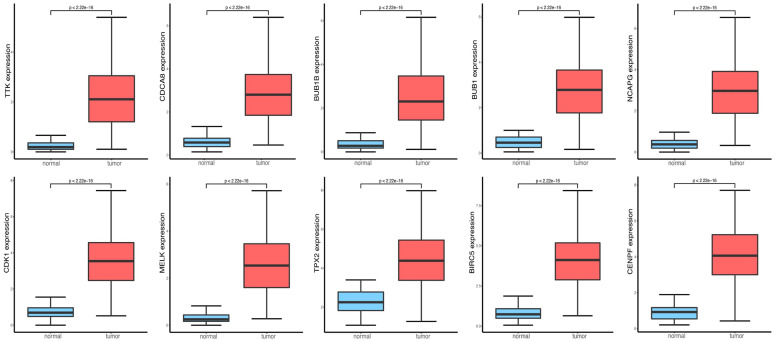

Relative mRNA expression of ten hub genes by TCGA

We obtained box plots of the top 10 genes from the TCGA database. Figure 7 shows that all of these genes had considerably greater levels of mRNA expression in HCC tissues than in normal tissues.

Figure 7.

The different expressions of the top 10 mRNAs from TCGA, the box plots in red refer to tumors, the blue box plots reflect normal samples.

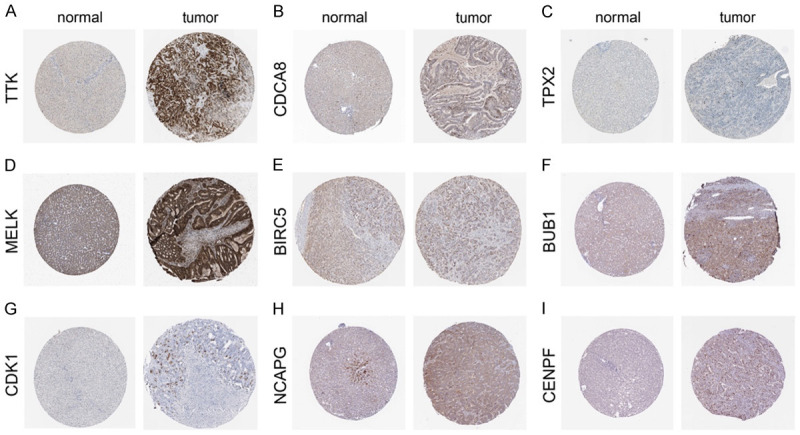

HPA database’s analysis of 9 hub genes’ relative expression in tissues

In addition, the HPA database’s immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining data showed that, with the exception of BUB1B, the expression levels of 9 hub genes were considerably greater in hepatocellular carcinoma cells than in healthy liver tissues. However, there was no available record for BUB1B in the HPA database (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Validation of the hub genes at the translational level by means of the HPA database. (A) TTK, (B) CDCA8, (C) TPX2, (D) MELK, (E) BIRC5, (F) BUB1, (G) CDK1, (H) NCAPG, (I) CENPF.

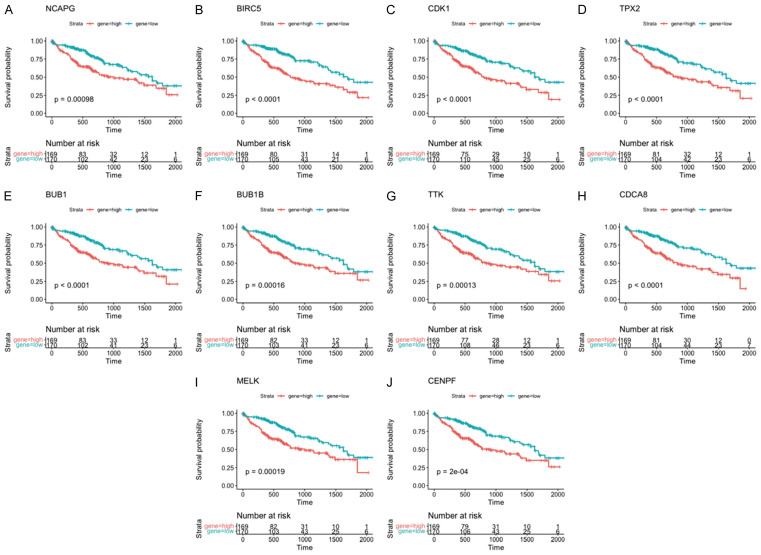

High expression of the top 10 hub genes is associated with poor prognosis

To examine the survival prospects of the top 10 hub genes, we used the ggsurvplot R program. Figure 9’s results showed a statistically significant positive connection between higher hub gene expression levels and worse overall survival.

Figure 9.

Overall survival of the top 10 hub genes in HCC patients from TCGA. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing the association between (A) NCAPG, (B) BIRC5, (C) CDK1, (D) TPX2, (E) BUB1, (F) BUB1B, (G) TTK, (H) CDCA8, (I) MELK, (J) CENPF, and overall survival in TCGA HCC patients.

Discussion

A complex, multi-step process involving the abnormal expression of a large number of genes leads to the formation of HCC. So far, the genes associated with the growth of HCC are still not completely understood. CircRNAs have emerged as potential biomarkers for tumors, with numerous studies highlighting their regulatory role in various diseases [17-19]. Research conducted by Wei Y et al. revealed a hidden network of circRNA-centric noncoding regulatory RNAs that are active in the early stages of HCC. They found that circ-CDYL affected the network to promote HCC tumorigenesis, promoting the tumorigenesis of HCC. This discovery opens up possibilities for early treatment of HCC, and a promising biomarker for early HCC surveillance may be created by combining AFP, circ-CDYL, HDGF, and HIF1AN [20]. By controlling the miR-338-3p/PKM2 axis both in vitro and in vivo, Li Q et al. found that circMAT2B increases glycolysis and malignancy of HCC cells under hypoxia. They also demonstrated that circMAT2B is considerably enhanced in HCC tissues and related to clinical characteristics. This suggests that circMAT2B could potentially provide a therapeutic target for HCC [21]. Han D et al. [22] discovered that circMTO1 promotes p21 expression by serving as a sponge for the oncogenic miR-9, which inhibits the progression of HCC. These results suggest that circMTO1 may be a therapeutic target for HCC. A predictive marker for poor patient survival may also be the decreased expression of circMTO1 in HCC tissues. Therefore, due to different functions, the selection of different circRNAs for the diagnosis, treatment and evaluation of patients is conducive to personalized treatment.

We carried out a study to look at the relationship between HCC and has-circ-0009158 expression levels. According to our research, HCC tissues and cell lines have significantly higher levels of hsa-circ-0009158 expression than the tissues next to them. Additionally, increased expression of hsa-circ-0009158 was linked to greater postoperative recurrence rates, weaker differentiation, and a higher prevalence of tumor thrombosis in HCC patients. This shows that hsa-circ-0009158 could enhance tumor growth during the development of HCC. Tumor thrombosis and microvascular invasion have been established as critical factors contributing to the poor prognosis of HCC patients [23,24]. Consistently, multivariate COX analysis confirmed that microvascular invasion and tumor thrombosis were separate risk factors for OS and RFS. More importantly, we found that high hsa-circ-0009158 expression independently predicted shorter RFS and poor OS in HCC patients. These findings have significant implications for accurately predicting recurrence and evaluating prognosis in HCC patients. However, to completely understand the intricate methods by which hsa-circ-0009158 affects HCC, more study is required. Larger-scale prospective studies will be crucial in achieving this goal.

The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis suggests that mRNA expression can be regulated by circRNAs to interact with miRNAs through miRNA response elements [25]. Thus, the miRNAs that bind to circ009158 were discovered. CircInteractome software and TCGA database were used to identify circRNA potential target miRNA. It was discovered that only one miRNA (hsa-miR-942) has been linked to hsa-circ-0009158. In increasing evidence, miRNAs bind to mRNA 3’UTRs and affect mRNA expression. Furthermore, the target mRNAs of miRNA were obtained using TargetScan. The prediction of miRNA target genes generated 3845. Moreover, we identified 2146 DEGs, including 1882 upregulated mRNAs and 264 downregulated mRNAs, from the TCGA database when comparing HCC and normal liver tissues. To narrow down our focus, we finally identified 248 mRNAs as the common DEGs from these two groups for further analysis, we constructed a miRNA-mRNA consisting of one miRNA and identified 248 mRNAs to gain deeper insights into the potential functions of circRNA.

In order to comprehend the function of circRNA in liver cancer cells better, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG analysis to analyze the protein-protein functional associations of the DEGs. The results of the GO analysis showed that the DEGs participated in mitotic nuclear division (GO:0140014), and tubulin binding (GO:0015631). Furthermore, the DEGs were primarily linked to the cell cycle, according to the KEGG pathway analysis.

To identify cancer-specific genes, we integrated gene regulatory networks and established a complex PPI network of the DEGs. Subsequently, the top ten hub genes were found within this network, which included MELK, NCAPG, BUB1B, BIRC5, CDCA8, CENPF, BUB1, CDK1, TTK, and TPX2. We evaluated the expression levels of these ten hub genes using information from the TCGA and HPA databases to confirm their importance. Results showed that all of these top 10 genes had significantly greater levels of mRNA expression in HCC tissues than in healthy liver tissues. With the exception of BUB1B, liver cancer tissues showed considerably higher levels of these genes’ expression. Hub gene survival results were verified using the TCGA clinical database. Hub gene expression showed a strong connection with the outcome of HCC patients in each case.

MELK (maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase), which belongs to the family of the AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase)-related kinase [26], suppressing MELK expression prevents the growth, invasion, stemness, and tumorigenic potential of HCC cells [27]. NCAPG, also referred to as non-SMC condensin I complex subunit G, was initially discovered in the nuclei of HeLa cell and has been shown to play a role in the organization of DNA with chromosomes [28]. Previous studies have highlighted the important roles of several hub genes in liver cancer. For instance, NCAPG has been discovered to have a major impact on cell migration and invasion of liver cancer [29]. Baculovirus IAP repeat containing 5 (BIRC5), located on human chromosome 17q25, is the inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAPs) family member [30]. By influencing cell division and proliferation and preventing apoptosis, it plays a significant part in the development of cancer [31]. CDAC8 is a member of the cell cycle division associated (CDCA) protein family [32], is prominently expressed in malignancies, and is connected to poor prognosis in bladder and breast cancer [33]. On chromosome 1q41, centrosome protein F (CENPF) encodes a protein that, as a component of the centrosome kinasome complex during interphase G2, is a constituent of the nuclear matrix [34]. Numerous studies have confirmed that CENPF is involved in tumor progression and metastasis [35]. BUB1 (budding uninhibited by benzimidazole 1) is essential for maintaining proper chromosome separation during mitosis and plays a role in reducing aneuploidy [36,37]. CDK1 (Cyclindependent kinase 1), an essential regulator of cell cycle progression, especially in mitosis [38], is involved in a number of biological functions, such as apoptosis, pluripotency, and maintaining genomic stability [39]. Monopole spindle 1 (MPS1), a protein kinase known as TTK (threonine tyrosine kinase), is a vital control mechanism for spindle assembly checkpoints and is in charge of preserving genomic integrity [40]. TTK has demonstrated its potential as a tumor therapeutic target [41]. TTK has been reported to modulate the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma [42]. TPX2 (targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2), has been reported as a marker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis [43].

It should be noted that this study revealed the prognostic significance of hsa-circ-0009158 in HCC, but there are several limitations. First, postoperative tissue specimens from HCC patients were collected. The expression of hsa-circ-0009158 was heterogeneous and variable in the tissue to some extent. Second, hsa-circ-0009158 expression in blood was not detected. In future studies, we will detect the expression of hsa-circ-0009158 in the blood, further exploring its potential role as a liquid biopsy diagnostic marker or its potential role as a therapeutic target. Clarification of the roles and mechanisms of circRNAs in cancer needs a lot more work, which will enhance our understanding of disease development and lead to improved prevention and treatment strategies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hsa-circ-0009158 is elevated in HCC and may be used as a biomarker to identify individuals having an unfavorable outlook and a significant likelihood of recurrence. The miRNA-mRNA network associated with hsa-circ-0009158 helps to understand the mechanism.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Key Laboratory Open Project (2022D04021), and Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region “Tian chi Talent” Program (2022TCYCDXG).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, Lencioni R, Koike K, Zucman-Rossi J, Finn RS. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidencebased diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:835–853. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Memczak S, Jens M, Elefsinioti A, Torti F, Krueger J, Rybak A, Maier L, Mackowiak SD, Gregersen LH, Munschauer M, Loewer A, Ziebold U, Landthaler M, Kocks C, le Noble F, Rajewsky N. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature. 2013;495:333–338. doi: 10.1038/nature11928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang PL, Bao Y, Yee MC, Barrett SP, Hogan GJ, Olsen MN, Dinneny JR, Brown PO, Salzman J. Circular RNA is expressed across the eukaryotic tree of life. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanger HL, Klotz G, Riesner D, Gross HJ, Kleinschmidt AK. Viroids are single-stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base-paired rod-like structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3852–3856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocquerelle C, Mascrez B, Hetuin D, Bailleul B. Mis-splicing yields circular RNA molecules. FASEB J. 1993;7:155–160. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.7678559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK, Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF, Sharpless NE. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141–157. doi: 10.1261/rna.035667.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salzman J. Circular RNA expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends Genet. 2016;32:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin J, Liu H, Jin M, Li W, Xu H, Wei F. Silencing of hsa_circ_0101145 reverses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma via regulation of the miR-548c-3p/LAMC2 axis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12:11623–11635. doi: 10.18632/aging.103324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song LN, Qiao GL, Yu J, Yang CM, Chen Y, Deng ZF, Song LH, Ma LJ, Yan HL. Hsa_ circ_0003998 promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma by sponging miR-143-3p and PCBP1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:114. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01576-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao Z, Luo J, Hu K, Lin J, Huang H, Wang Q, Zhang P, Xiong Z, He C, Huang Z, Liu B, Yang Y. ZKSCAN1 gene and its related circular RNA (circZKSCAN1) both inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth, migration, and invasion but through different signaling pathways. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:422–437. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai N, Peng E, Qiu X, Lyu N, Zhang Z, Tao Y, Li X, Wang Z. circFBLIM1 act as a ceRNA to promote hepatocellular cancer progression by sponging miR-346. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2018;37:172. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0838-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia S, VanDusen WJ, Diehl RE, Kohl NE, Dixon RA, Elliston KO, Stern AM, Friedman PA. cDNA cloning and expression of bovine aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14322–14327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue T, Su J, Li H, Xue X. Evaluation of HAAH/humbug quantitative detection in the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:329–337. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zou Q, Hou Y, Wang H, Wang K, Xing X, Xia Y, Wan X, Li J, Jiao B, Liu J, Huang A, Wu D, Xiang H, Pawlik TM, Wang H, Lau WY, Wang Y, Shen F. Hydroxylase activity of ASPH promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition pathway. EBioMedicine. 2018;31:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng S, Zhou H, Feng Z, Xu Z, Tang Y, Li P, Wu M. CircRNA: functions and properties of a novel potential biomarker for cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:94. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0663-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhong Y, Du Y, Yang X, Mo Y, Fan C, Xiong F, Ren D, Ye X, Li C, Wang Y, Wei F, Guo C, Wu X, Li X, Li Y, Li G, Zeng Z, Xiong W. Circular RNAs function as ceRNAs to regulate and control human cancer progression. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:79. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0827-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han B, Chao J, Yao H. Circular RNA and its mechanisms in disease: from the bench to the clinic. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;187:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei Y, Chen X, Liang C, Ling Y, Yang X, Ye X, Zhang H, Yang P, Cui X, Ren Y, Xin X, Li H, Wang R, Wang W, Jiang F, Liu S, Ding J, Zhang B, Li L, Wang H. A noncoding regulatory RNAs network driven by circ-CDYL acts specifically in the early stages hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2020;71:130–147. doi: 10.1002/hep.30795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Pan X, Zhu D, Deng Z, Jiang R, Wang X. Circular RNA MAT2B promotes glycolysis and malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma through the miR-338-3p/PKM2 axis under hypoxic stress. Hepatology. 2019;70:1298–1316. doi: 10.1002/hep.30671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han D, Li J, Wang H, Su X, Hou J, Gu Y, Qian C, Lin Y, Liu X, Huang M, Li N, Zhou W, Yu Y, Cao X. Circular RNA circMTO1 acts as the sponge of microRNA-9 to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2017;66:1151–1164. doi: 10.1002/hep.29270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rastogi A. Changing role of histopathology in the diagnosis and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4000–4013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i35.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang YK, Bi XY, Li ZY, Zhao H, Zhao JJ, Zhou JG, Huang Z, Zhang YF, Li MX, Chen X, Wu XL, Mao R, Hu XH, Hu HJ, Liu JM, Cai JQ. A new prognostic score system of hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatectomy. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2017;39:903–909. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3766.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi X, Zhang DH, Wu N, Xiao JH, Wang X, Ma W. ceRNA in cancer: possible functions and clinical implications. J Med Genet. 2015;52:710–718. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hardeman AA, Han YJ, Grushko TA, Mueller J, Gomez MJ, Zheng Y, Olopade OI. Subtypespecific expression of MELK is partly due to copy number alterations in breast cancer. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0268693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia H, Kong SN, Chen J, Shi M, Sekar K, Seshachalam VP, Rajasekaran M, Goh BKP, Ooi LL, Hui KM. MELK is an oncogenic kinase essential for early hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. Cancer Lett. 2016;383:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun H, Zhang H, Yan Y, Li Y, Che G, Zhou C, Nicot C, Ma H. NCAPG promotes the oncogenesis and progression of non-small cell lung cancer cells through upregulating LGALS1 expression. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:55. doi: 10.1186/s12943-022-01533-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu W, Liang B, Liu H, Huang Y, Yin X, Zhou F, Yu X, Feng Q, Li E, Zou Z, Wu L. Overexpression of non-SMC condensin I complex subunit G serves as a promising prognostic marker and therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Med. 2017;40:731–738. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao L, Li C, Shen S, Yan Y, Ji W, Wang J, Qian H, Jiang X, Li Z, Wu M, Zhang Y, Su C. OCT4 increases BIRC5 and CCND1 expression and promotes cancer progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harao M, Hirata S, Irie A, Senju S, Nakatsura T, Komori H, Ikuta Y, Yokomine K, Imai K, Inoue M, Harada K, Mori T, Tsunoda T, Nakatsuru S, Daigo Y, Nomori H, Nakamura Y, Baba H, Nishimura Y. HLA-A2-restricted CTL epitopes of a novel lung cancer-associated cancer testis antigen, cell division cycle associated 1, can induce tumor-reactive CTL. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2616–2625. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qi G, Zhang C, Ma H, Li Y, Peng J, Chen J, Kong B. CDCA8, targeted by MYBL2, promotes malignant progression and olaparib insensitivity in ovarian cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11:389–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahid M, Lee MY, Piplani H, Andres AM, Zhou B, Yeon A, Kim M, Kim HL, Kim J. Centromere protein F (CENPF), a microtubule binding protein, modulates cancer metabolism by regulating pyruvate kinase M2 phosphorylation signaling. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:2802–2818. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1557496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahid M, Kim M, Lee MY, Yeon A, You S, Kim HL, Kim J. Downregulation of CENPF remodels prostate cancer cells and alters cellular metabolism. Proteomics. 2019;19:e1900038. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201900038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts BT, Farr KA, Hoyt MA. The saccharomyces cerevisiae checkpoint gene BUB1 encodes a novel protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8282–8291. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leontiou I, London N, May KM, Ma Y, Grzesiak L, Medina-Pritchard B, Amin P, Jeyaprakash AA, Biggins S, Hardwick KG. The Bub1-TPR domain interacts directly with Mad3 to generate robust spindle checkpoint arrest. Curr Biol. 2019;29:2407–2414. e2407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhong L, Hu MM, Bian LJ, Liu Y, Chen Q, Shu HB. Phosphorylation of cGAS by CDK1 impairs self-DNA sensing in mitosis. Cell Discov. 2020;6:26. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neganova I, Tilgner K, Buskin A, Paraskevopoulou I, Atkinson SP, Peberdy D, Passos JF, Lako M. CDK1 plays an important role in the maintenance of pluripotency and genomic stability in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1508. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musacchio A. The molecular biology of spindle assembly checkpoint signaling dynamics. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R1002–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia P, Liang J, Jin D, Jin Z. Reversine inhibits proliferation, invasion and migration and induces cell apoptosis in gastric cancer cells by downregulating TTK. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22:929. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu N, Ren LX. TTK (threonine tyrosine kinase) regulates the malignant behaviors of cancer cells and is regulated by microRNA-582-5p in ovarian cancer. Bioengineered. 2021;12:5759–5768. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2021.1968778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gruss OJ, Wittmann M, Yokoyama H, Pepperkok R, Kufer T, Silljé H, Karsenti E, Mattaj IW, Vernos I. Chromosome-induced microtubule assembly mediated by TPX2 is required for spindle formation in HeLa cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:871–879. doi: 10.1038/ncb870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]