Abstract

Elucidating the molecular mechanism of autophagy was a landmark in understanding not only the physiology of cells and tissues, but also the pathogenesis of diverse diseases, including diabetes and metabolic disorders. Autophagy of pancreatic β‐cells plays a pivotal role in the maintenance of the mass, structure and function of β‐cells, whose dysregulation can lead to abnormal metabolic profiles or diabetes. Modulators of autophagy are being developed to improve metabolic profile and β‐cell function through the removal of harmful materials and rejuvenation of organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. Among the known antidiabetic drugs, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists enhance the autophagic activity of β‐cells, which might contribute to the profound effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists on systemic metabolism. In this review, the results from studies on the role of autophagy in β‐cells and their implication in the development of diabetes are discussed. In addition to non‐selective (macro)autophagy, the role and mechanisms of selective autophagy and other minor forms of autophagy that might occur in β‐cells are discussed. As β‐cell failure is the ultimate cause of diabetes and unresponsiveness to conventional therapy, modulation of β‐cell autophagy might represent a future antidiabetic treatment approach, particularly in patients who are not well managed with current antidiabetic therapy.

Keywords: β‐Cells, Autophagy, Lysosome

Results from previous studies on the role of autophagy of β‐cell function together with its implication in the development of diabetes are discussed. As β‐cell failure is an ultimate cause of diabetes and also that of unresponsiveness to the conventional therapy, modulation of β‐cell autophagy could be a future antidiabetic modality, particularly for patients who are not well managed with current antidiabetic therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy, which literally means ‘self‐eating’, is the process of lysosomal self degradation of cell material. There are three major types of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone‐mediated autophagy1. In addition, other types of autophagy have been described, such as crinophagy, starvation‐induced nascent granule degradation, Golgi membrane‐associated degradation (GOMED), vesicophagy, chaperone‐assisted selective autophagy and chaperone‐assisted endosomal microautophagy 2 , 3 , 4 . Among these types of autophagy that might occur in hormone‐producing cells, such as islet β‐cells, macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) has been most extensively studied.

Autophagy is an intracellular process of rearrangement of subcellular membranes that sequesters the cytoplasm and other cellular materials, including proteins and organelles, such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), leading to the formation of a specialized organelle known as the ‘autophagosome’. Thus, autophagosomes are morphologically described as target organelles (or other cellular material) surrounded by a double membrane, which is a classical hallmark of autophagy. After formation, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes, producing autolysosomes, in which lysosomal enzymes digest sequestered materials or organelles 1 , 5 . Thus, lysosome is an effector organelle in autophagy. The primary function of autophagy is to maintain intracellular (nutritional) homeostasis, and the quality or function of organelles and cellular constituents.

Although autophagy was originally described as a non‐selective process that targets bulk intracellular constituents, it is now widely accepted that autophagy can target specific organelles or molecules (selective autophagy). Thus, each specific type of autophagy has its own designation (e.g., mitophagy, ER‐phagy, pexophagy, granulophagy, ribophagy and lipophagy) and machinery in addition to the common basic machinery of autophagy.

As autophagy plays an important role in the maintenance of the organelle function, such as mitochondria or ER that are critical for the survival or function of pancreatic β‐cells and insulin sensitivity, dysregulated autophagy might result in β‐cell dysfunction or death and altered insulin sensitivity. Here, we discuss current data regarding the role of pancreatic β‐cell autophagy in the maintenance of β‐cell function, as well as in the pathogenesis and management of diabetes.

MOLECULAR MACHINERY OF AUTOPHAGY

The autophagic process can be divided into three stages: initiation/nucleation, expansion/completion and degradation/retrieval. During the initiation/nucleation stage, the Unc‐51‐like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1) and Beclin 1 complexes are important. Under nutrient‐replete conditions, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) kinase, which is incorporated into the ULK1‐Atg13‐FIP200 complex phosphorylates ULK1. In contrast, the inhibition of mTORC1 by starvation or rapamycin treatment results in the dissociation of mTORC1 from the ULK complex, which phosphorylates mAtg13 and FIP200 to initiate the autophagic process 1 . ULK1 also phosphorylates Ambra1, a Beclin 1‐interacting protein, which induces Beclin 1 translocation to ER. Beclin 1 then forms a complex with Vps34, Vps15 and Atg14L. Vps34, a class III phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase, generates phosphatidylinositol‐3‐phosphate and recruits double FYVE‐containing protein 1, WIPI2 (a phosphatidylinositol‐3‐phosphate‐binding effector) and autophagy‐related (Atg) proteins, to initiate the nucleation process.

The autophagosome expansion/completion stage comprises two ubiquitin‐like pathways, and the Atg system is important to both pathways. Atg7 is an E1‐like enzyme, and Atg10 and Atg3 act as E2‐like enzymes. The Atg12‐Atg5‐Atg16L1 complex acts as an E3‐like complex 1 . Atg8, also known as microtubule‐associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), is a ubiquitin‐like molecule. After recruitment to the isolation membrane because of the E1‐, E2‐ and E3‐like actions of other Atg members, Atg8 is conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine, a lipid target, to form LC3‐II1. There are seven LC3‐related proteins, of which LC3B in the most extensively studied, although each LC3 member might have a non‐redundant role.

Once autophagosome is formed, it fuses with lysosome, and lysosomal enzymes induce hydrolysis of entrapped organelles and macromolecules. When nutrients become available from the autophagic degradation of cellular materials, mTORC1 is reactivated and proto‐lysosomal tubule is formed. This tubule matures into functional lysosome 6 , which constitutes the final step of the degradation/retrieval stage to complete the full autophagy cycle.

MACHINERY OF SELECTIVE AUTOPHAGY

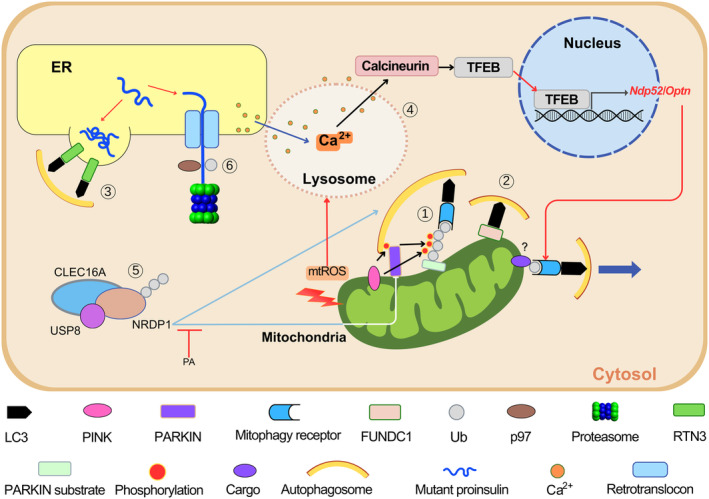

Unlike bulk autophagy, selective autophagy targets specific organelles or molecules, which is needed for the maintenance and function of cellular organelles, such as mitochondria, ER, peroxisome, lysosome or ribosome. With respect to the specific types and machinery of selective autophagy, a well‐known example is mitophagy. Among several types of mitophagy, PTEN‐induced putative kinase (PINK)–PARKIN‐dependent mitophagy is a classic example of ubiquitin‐mediated mitophagy 7 , 8 . PINK1 is rapidly imported into the mitochondrial intermembrane space and degraded by presenilin‐associated rhomboid‐like protein when the mitochondrial potential is maintained. In contrast, PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane when mitochondrial potential is disrupted 9 . PINK recruits PARKIN, an E3 ligase, which induces the ubiquitination of several outer mitochondrial membrane proteins (Figure 1①). Autophagy (mitophagy) receptors harboring the ubiquitin‐binding domain and LC3‐interacting region domain, such as p62, optineurin or NDP52, are then recruited for mitophagy progression. In addition to the PINK–PARKIN pathway, other types of mitophagy, such as receptor‐mediated mitophagy, piecemeal‐type mitophagy and micromitophagy, have been described 10 , 11 . Receptor‐mediated mitophagy is characterized by direct recruitment of LC3 to mitochondrial target proteins that are localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane, and contain LC3‐interacting region domains, such as BNIP3, NIX, FUNDC1, BCL2L13 or FKBP8 10 (Figure 1②). FUNDC1‐mediated mitophagy has been reported to contribute to metabolic homeostasis 12 . A recent study reported that FUNDC1 deficiency aggravated palmitic acid‐induced lipotoxicity 13 .

Figure 1.

Selective autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells. (①) When mitochondrial stress occurs, PTEN‐induced putative kinase (PINK) accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane of depolarized mitochondria and induces ubiquitin phosphorylation and PARKIN recruitment. PARKIN, an E3 ligase, induces the ubiquitination of target proteins recognized by mitophagy receptors, such as NDP52 or OPTN, to initiate autophagosome formation. (②) Receptor‐mediated mitophagy occurs by direct binding of LC3 to mitophagy receptor molecules on the outer mitochondrial membrane harboring LC3‐interacting region domains, such as FUNDC1. (③) Aggregates of misfolded proteins are formed and degraded by endoplasmic reticulum (ER)‐phage, which is mediated by ER‐phagy receptors, such as RTN3 when ERAD (see ⑥) is impaired or insufficient. (④) Metabolic or mitochondrial stress induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production that can activate lysosomal Ca2+ channels and induce lysosomal Ca2+ release. Transcription factor EB (TFEB) is activated by Ca2+/calcineurin‐mediated dephosphorylation, and then moves to the nuclei to promote expression of target genes including mitophagy receptor genes, such as Ndp52 or Optn. Mitophagy receptors interact with LC3 and mitophagy cargos. Lysosomal Ca2+ release is replenished by Ca2+ from ER, the largest Ca2+ reservoir (dark blue arrow). (⑤) Mitophagy through the CLEC16A–NRDP1–USP8 complex can occur. CLEC16A protects NRDP1, which degrades PARKIN. CLEC16A and NRDP1 also participate in autophagosome‐lysosome fusion. The inhibition of CLEC16A–NRDP1–USP8‐dependent mitophagy by palmitic acid (PA) might play a role in mitochondrial dysfunction caused by metabolic stress. (⑥) ER‐associated degradation (ERAD) induces the degradation of misfolded proteins, such as mutant proinsulin, through the p97‐mediated extraction of ubiquitinated proteins. mtROS, mitochondrial reactive oxygen species.

The molecular pathways for other types of selective autophagy in addition to mitophagy have also been characterized. Autophagy receptors for ER‐phagy identified so far include FAM134B, Sec62, RTN3, CCPG1, ATL3, TEX264 and CALCOCO1 14 , 15 , 16 (Figure 1③). Of these, Sec62 plays a role in recovery from ER stress in a process known as ‘recovER‐phagy’ 14 . ER stress induces FAM134B phosphorylation through CAMK2B and oligomerization, which results in ER fragmentation and ER‐phagy 17 . RTN3 is particularly important for fragmentation and autophagy of the ER tubule 15 .

β‐CELL AUTOPHAGY IN β‐CELL FUNCTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF DIABETES

As autophagy is indispensable for the maintenance of organelles including mitochondria and ER that are important to β‐cell physiology, autophagy is expected to play a critical role in β‐cell function. Murine β‐cells with targeted disruption of critical autophagy genes, such as Atg5 or Atg7 (Atg5 Δβ‐cell or Atg7 Δβ‐cell mice), show abnormal morphology and function of the mitochondria, ER, and other organelles 18 , 19 , 20 , which shows that autophagy is important for β‐cell survival and function. In addition to the physiological roles of autophagy, dysregulated β‐cell autophagy has a role in the development of diabetes. To study the role of dysregulated autophagy in the development of diabetes, Atg7 Δβ‐cell mice were crossed to ob/ob mice or fed a high‐fat diet (HFD) to induce metabolic stress. Although Atg7 Δβ‐cell mice had only mild hyperglycemia, Atg7 Δβ‐cell‐ob/ob mice and HFD‐fed Atg7 Δβ‐cell mice developed overt diabetes, indicating that autophagy plays an important role in the adaptation of β‐cells to metabolic stress 20 , 21 . In vitro studies have also shown that autophagy protects islet cells or insulinoma cells from lipotoxicity or glucolipotoxicity by restoring lysosomal function 22 , 23 . Autophagy‐deficient β‐cells were also more susceptible to ER stress imposed by metabolic stress in vitro and in vivo 20 . A recent study also reported a protective role of β‐cell autophagy induced by C3 binding to ATG16L1 against palmitic acid‐induced lipoapoptosis 24 . These results are consistent with those of previous studies, indicating a protective role of β‐cell autophagy against ER stress by proinsulin misfolding or insulin secretory defects 25 , 26 , 27 . They are also in line with recent studies showing that ER‐phagy is closely related to the unfolded protein response and susceptibility to ER stress 28 , as discussed later.

Although most previous studies reported the salutary effects of autophagy on β‐cells, contrasting results have been published. Autophagy inhibition might reduce β‐cell death resulting from Pdx1 knockdown or amino acid deprivation 29 , suggesting the possibility of autophagic cell death. Rapamycin, a representative mTORC1 inhibitor and autophagy enhancer, also could inhibit β‐cell function and viability through the upregulation of autophagy 30 . Rapamycin‐induced autophagy has also been reported to downregulate insulin release, which was abrogated by chloroquine, an autophagy inhibitor 31 . Furthermore, short‐term knockdown of autophagy genes might increase the content or release of insulin or proinsulin, which is in contrast to the results obtained using mice with targeted disruption of autophagy genes in β‐cells 32 , 33 . These results might be ascribed to the reduced autophagic degradation of proinsulin or lysosomal lipids, which negatively regulates insulin secretion. Inconsistencies between studies on the effect of autophagy on β‐cell survival, death or function might be partly the results of ambiguity regarding the definition or significance of autophagic cell death and differences in the methods and duration of genetic manipulation or drug treatment. Further studies are needed to elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms of autophagy‐associated β‐cell death and its functional consequences.

β‐CELL AUTOPHAGY IN DIABETES PATIENTS WITH ISLET AMYLOID

Most studies addressing the role of β‐cell autophagy in diabetes have used rodent models; however, human and rodent diabetes models are different in that amyloid deposition in pancreatic islets is observed in >90% of human patients with type 2 diabetes, but never occurs in rodent diabetes models 34 . This is due to the difference in the amino acid sequence of islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP) 34 . Amyloid or aggregate proteins formed from amyloidogenic human IAPP (hIAPP) are preferentially degraded by the autophagy–lysosomal pathway rather than by the proteasomal degradation pathway, whereas soluble or non‐amyloidogenic proteins, such as murine IAPP molecules, are also degraded by the proteasomal pathway 35 . Thus, autophagy is likely to play an important role in the development of human type 2 diabetes associated with islet amyloid accumulation and subsequent β‐cell dysfunction.

The role of autophagy in the clearance of hIAPP oligomer and islet amyloid in vivo was examined in transgenic mice expressing hIAPP in pancreatic β‐cells (hIAPP + mice). Although hIAPP + mice do not have diabetes, the same mice developed overt diabetes after breeding with β‐cell‐specific Atg7‐knockout (KO) mice (hIAPP + Atg7 Δβ‐cell mice) or administering an HFD 36 , 37 . Furthermore, accumulation of hIAPP oligomer and islet amyloid was observed after crossing with β‐cell‐specific Atg7‐KO mice or HFD feeding, which was accompanied by apoptotic β‐cells 36 . The death of β‐cells in these mice was ascribed to the accumulation of hIAPP oligomer, as hIAPP oligomer rather than islet amyloid would be a dominant effector molecule exerting cellular toxicity to islet cells 34 . The mechanism of β‐cell death by hIAPP oligomer is unclear, although ER stress 38 , ER translocon clogging 39 , inflammasome activation 40 or membrane pore formation 41 , 42 have been implicated. When hIAPP knock‐in mice were used instead of hIAPP + mice, essentially similar results were observed, such as more severe metabolic changes and β‐cell loss after HFD feeding 43 . Although the clearance of hIAPP oligomer might be considered a type of aggrephagy 44 , the molecular species of dominant (pro)‐hIAPP oligomers targeted by autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells, autophagic receptors involved in hIAPP oligomer clearance and the underlying mechanism or site of organelle injury by hIAPP oligomer remain unclear.

The data on hIAPP oligomer clearance in vivo have been gathered from genetic animal models expressing hIAPP to mimic human diabetes. Although direct evidence implicating the role of autophagy in the clearance of hIAPP oligomer or amyloid in human diabetes is lacking, indirect evidence supporting a role for autophagy in this regard has been reported. For example, the increased accumulation of hIAPP amyloid was observed in islets of aged subjects 45 . These data suggest the possibility that hIAPP amyloid accumulates in aged β‐cells with reduced autophagic activity. Reduced β‐cell autophagic activity associated with type 2 diabetes was suggested in previous studies showing an increase in autophagosome content in islets of type 2 diabetes patients 46 , which was likely due to the inhibition of the lysosomal steps of autophagy or fusion between autophagosome and lysosome.

As lysosome is an effector organelle in the execution of autophagic degradation of substrate molecules or organelles, lysosomal dysfunction or stress is likely to result in impaired autophagic activity. The reduced activation of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis or autophagy gene expression and downregulated expression of LAMP2, a lysosomal protein, have been observed in pancreatic islets of type 2 diabetes patients 47 . These results suggest lysosomal dysfunction and decreased autophagic activity in β‐cells of patients with type 2 diabetes.

MITOPHAGY AND ER‐PHAGY IN β‐CELLS

Although the effects of β‐cell autophagy on mitochondrial function in pancreatic β‐cells have been widely examined, β‐cell mitophagy per se has been less well studied. Previous studies examined the role of PARKIN, a well‐known player in mitophagy, in mitophagy of β‐cells. Parkin‐KO mice showed more severe impairment of glucose tolerance and reduced insulin release after treatment with streptozotocin, a β‐cell toxin, compared with wild‐type mice 18 . This suggests a protective role of Parkin‐mediated mitophagy in β‐cells under stress.

However, β‐cell‐specific Parkin‐KO mice did not have an apparent abnormality in β‐cell function or glucose homeostasis 48 , which might be the result of compensatory changes associated with Parkin deficiency. Instead, the role of mitophagy in pancreatic β‐cells has been examined using mice with β‐cell‐specific KO of Tfeb, a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy gene expression (Tfeb Δβ‐cell mice) 49 . Furthermore, Tfeb family members also play important roles in mitophagy 50 , 51 . Tfeb might be activated by mitochondrial or metabolic stress, which induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species release, subsequent lysosomal Ca2+ release and calcineurin activation (Figure 1④). This might lead to the induced expression of mitophagy receptor genes, such as Ndp52 or Optn, which are Tfeb targets 52 . Tfeb Δβ‐cell mice might not mobilize Tfeb‐dependent adaptive increases in mitophagy and mitochondrial complex activity of β‐cells in response to HFD feeding, which results in further aggravated metabolic deterioration 52 .

The importance of mitophagy in β‐cell function was also shown in mice that developed β‐cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance after treatment with FK506, a calcineurin inhibitor, which impeded activation of calcineurin and TFEB (Figure 1). Post‐transplantation diabetes mellitus developing in up to 40% of patients after transplantation and treatment with calcineurin inhibitors, such as FK506 53 , could be partly due to diminished autophagy or mitophagy, as calcineurin inhibitors, such as FK506, inhibit calcineurin‐dependent activation of TFEB and autophagy or mitophagy 54 . In addition to mitophagy inhibition, FK506 might also impair proliferation of β‐cells 55 .

In addition to PARKIN‐induced mitophagy, CLEC16A, a membrane‐associated C‐type lectin acting as an E3 ligase, regulates mitophagy of β‐cells and insulin secretion. CLEC16A forms a complex with NRDP1 and USP8, and disruption of this complex by metabolic stress reduces mitophagy and β‐cell function 56 , 57 (Figure 1⑤). The CLEC16A‐NRDP1‐USP8 complex regulates PARKIN expression and plays a role in autophagosome trafficking to lysosome 58 . In Drosophila, Ema, a Clec16A homolog, promotes the maturation of autophagosome and endosome through its interaction with the class C Vps‐HOPS tethering complex 59 , supporting a role of Clec16A in the basic process of autophagy.

In addition to mitophagy, other types of selective autophagy, such as ER‐phagy or lipophagy, occur in pancreatic β‐cells and play an important role in the pathophysiological events associated with glucose homeostasis or the development of diabetes. As changes of ER occur in autophagy‐deficient pancreatic β‐cells, ER‐phagy might occur in pancreatic β‐cells. A notable example of ER‐phagy in β‐cells is the clearance of mutant proinsulin known as Akita proinsulin‐C(A7)Y. RTN3‐mediated ER‐phagy (Figure 1③) has been shown to clear mutant proinsulin aggregates that are formed if Grp170‐mediated ER‐associated degradation (ERAD; Figure 1⑥) fails to degrade mutant proinsulin 60 . A recent study has shown that ER‐phagy occurs in β‐cells when the ERAD pathway degrading proinsulin aggregates in a manner dependent on inositol‐requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1α (IRE1α), an important branch of unfolded protein response (Figure 1⑥), is disrupted. IRE1α is a substrate of ERAD that is increased when ERAD is impaired, which results in the activation of ER‐phagy likely through the induction of RTN3, an ER‐phagy receptor on ER tubule (Figure 1③). These results suggest synergism between ERAD, unfolded protein response and autophagy machinery in the maintenance of ER homeostasis 28 . Intriguingly, a POMC‐C28F mutant associated with early‐onset obesity was reported to be cleared by RTN3‐mediated ER‐phagy 61 , which showed a similar mode of ER‐phagy in endocrine cells with secretory granules.

OTHER TYPES OF AUTOPHAGY

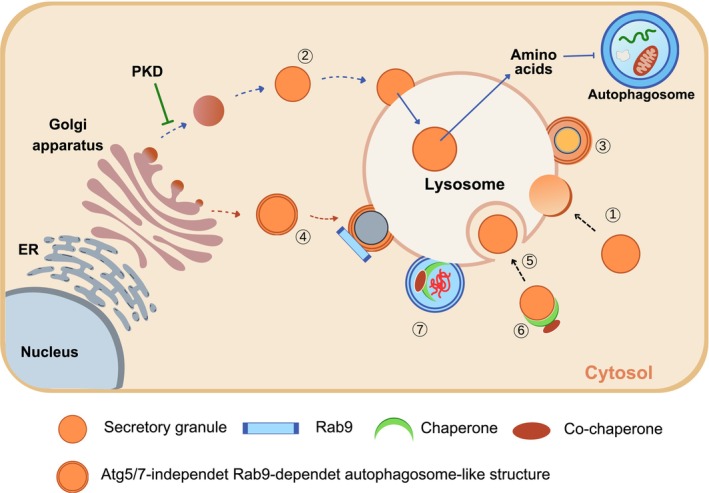

In addition to (macro)autophagy and major types of selective autophagy, other types of autophagy or lysosomal degradation pathways occurring in pancreatic β‐cells have been described. Crinophagy is a special form of autophagy that is hallmarked by the direct fusion of secretory granules into lysosome and the subsequent degradation of secretory granule components, such as insulin 62 (Figure 2①). Crinophagy might play an essential physiological role in intracellular insulin degradation 63 , and might be precisely regulated by glucose concentration 64 , in which surplus insulin degradation by crinophagy occurs to avoid hypoglycemia.

Figure 2.

Lysosomal autophagic degradation pathways other than macroautophagy that can occur in β‐cells. (①) Crinophagy: β‐cell granules directly fuse with lysosomal membrane for insulin degradation. (②) Stress‐induced nascent granule degradation (SINGD): When protein kinase D (PKD) is inactivated during starvation in the Golgi area, nascent insulin secretory granules generated in the Golgi complex directly fuse with lysosomes. Amino acids released by lysosomal degradation of insulin granules activate mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and thereby inhibit autophagy. (③) Vesicophagy: Insulin granules are surrounded by autophagosome. Autophagosome containing insulin secretory granules fuses with lysosome for degradation of insulin secretory granules. (④) Golgi membrane‐associated degradation (GOMED): When the insulin secretory process from the Golgi complex is abrogated in β‐cells, which are deficient in autophagy, an autophagosome‐like double‐membrane structure is formed from the Golgi membrane in an Atg5/7‐independent and Rab9‐dependent manner. (⑤) Microautophagy: β‐cell granules are engulfed by late endosome or multivesicular body (MVB) in a manner similar to phagocytosis of foreign or endogenous materials. (⑥) Chaperone‐assisted endosomal microautophagy (CAEMI): Target molecules or structures are conjugated to chaperones and co‐chaperones for engulfment by endosome. (⑦) Chaperone‐assisted selective autophagy (CASA): Target molecules or structures are conjugated to chaperones and co‐chaperones for autophagic degradation.

Nascent insulin secretory granules are degraded by lysosomes in a process known as stress‐induced nascent granule degradation (SINGD), and nutrients released from SINGD might prevent further autophagy. SINGD occurs in proximity to the Golgi complex, and might be inhibited by protein kinase D 2 (Figure 2②). SINGD might be a mechanism that limits insulin release during starvation. Vesicophagy is a form of autophagy occurring in β‐cells of mice with transgenic expression of Becn1 F121A, which blocks Becn1 binding to Bcl‐2 and renders Becn1 constitutively active 65 . HFD‐fed Becn1 F121A/F121A and Becn1 F121A/+ mice showed improved insulin sensitivity due to reduced ER stress in insulin target tissues, but aggravated glucose tolerance due to impaired insulin release from β‐cells 4 . These findings were attributed to the sequestration and degradation of insulin granules through ‘vesicophagy’ activation, in β‐cells 4 (Figure 2③).

GOMED is a non‐canonical bulk degradation pathway that can compensate for the absence of Atg5/Atg7‐dependent canonical autophagy 3 . When Golgi‐to‐plasma membrane anterograde trafficking is inhibited, Golgi membrane stacking occurs, followed by the formation of autophagosome‐like double‐membrane compartments in a RAB9‐dependent manner. When the insulin secretory process from the Golgi apparatus is suppressed, GOMED might be activated in response to glucose deprivation to degrade unused (pro)insulin granules in Atg5‐ or Atg7‐deficient β‐cells (Figure 2④). GOMED might be a mechanism regulating insulin release during starvation, particularly when protein degradation by conventional autophagy is sluggish due to type 2 diabetes or lipid overload 66 .

Microautophagy is another form of lysosomal degradation of insulin granules in pancreatic β‐cells in which the direct lysosomal engulfment of insulin granules typically occurs through a phagocytosis‐like mechanism (Figure 2⑤). The molecular machinery of microautophagy involves the delivery of cytosolic proteins to the late endosome or multivesicular body, which is dependent upon the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) and hsc70 67 . Chaperone‐assisted endosomal microautophagy and chaperone‐assisted selective autophagy are specialized forms of lysosomal autophagy assisted by chaperones and co‐chaperones for microautophagy and selective autophagy, respectively 68 (Figure 2⑥,⑦), whereas their occurrence in pancreatic β‐cells is unknown.

ANTIDIABETIC DRUGS AND β‐CELL AUTOPHAGY

As most studies have suggested the beneficial role of autophagy in pancreatic β‐cell survival and function, autophagy modulators or enhancers might represent new therapeutic agents against metabolic diseases or diabetes associated with lipid overload or islet amyloid accumulation. Several groups have developed such autophagy modulators, and studied the effects of novel agents or known drugs, such as berberine, imatinib, MSL‐7, rapamycin, resveratrol, spermidine, trehalose, rosiglitazone or fenofibrate, on β‐cell autophagy and diabetes. Readers are encouraged to consult recent reviews 69 . In the present review, the role of autophagy in the effects of known drugs that are already used for treating metabolic disorders and diabetes is discussed.

Metformin

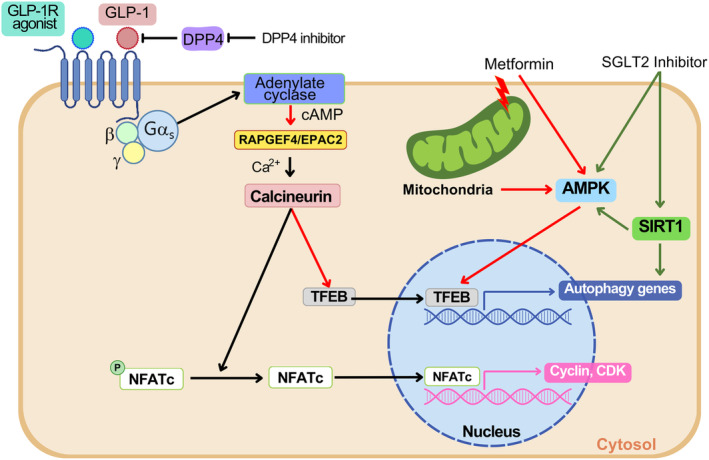

Metformin is a widely‐used antidiabetic medicine that has been recommended as the first‐line treatment for diabetes. Metformin has both adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK)‐dependent and ‐independent mechanisms for improving the metabolic profile 70 , 71 . Thus, metformin would be able to enhance autophagic activity due to AMPK activation that upregulates autophagic activity through direct phosphorylation of ULK1 and Beclin 1 72 , 73 , inhibition of mTORC1 73 , 74 , 75 or enhancement of transcriptional activity of TFEB 76 . Autophagy induction by AMPK activation is consistent with the idea that autophagy is an adaptive process in response to nutrient deficiency, and AMPK is a sensor of intracellular energy balance. Thus, well‐established AMPK activation by metformin suggests the possibility that metabolic improvement by metformin might be associated with autophagy induction through AMPK activation (Figure 3). Consistent with this concept, the protection of pancreatic β‐cells against lipoapoptosis by metformin was attributed to autophagy activation 77 , 78 . Thus, the antidiabetic effect of metformin might occur, in part, through autophagy activation. The therapeutic effect of metformin in autophagy regulation in diabetes or related metabolic diseases might be associated with restoration of impaired TFEB activation, as was shown in the liver of HFD‐fed mice 79 .

Figure 3.

Autophagy activation by current antidiabetic drugs. Metformin can enhance autophagy through direct activation of adenosine monophosphate‐activated protein kinase (AMPK), which phosphorylates transcription factor EB (TFEB) and enhances transcriptional activity. Metformin‐mediated inhibition of mitochondrial complex I would contribute to AMPK activation by metformin. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor (GLP‐1R) agonists induce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production through activation of Gαs and adenylate cyclase. cAMP produced by adenylate cyclase activates EPAC2, which can induce Ca2+ release from intracellular sources and subsequent Ca2+/calcineurin‐dependent nuclear translocation of TFEB, a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy gene expression. Ca2+/calcineurin– can also induce the growth of juvenile β‐cells through the dephosphorylation of NFATc, and induction of CDK and cyclin. SGLT2 inhibitor can activate AMPK and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). SIRT1 induces autophagy gene expression through deacetylation of PGC‐1α. Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP4) inhibitor increases the serum GLP‐1 levels.

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist

Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor (GLP‐1R) agonists could be an example of antidiabetic drugs potentially associated with β‐cell autophagy 77 , 80 . Previous studies suggested that exendin‐4, a prototypic GLP‐1R agonist, might reduce lysosomal dysfunction and defective autophagosome‐lysosome fusion caused by FK506 80 , which might contribute to the improved metabolic profile of experimental animals treated with GLP‐1R agonists. The effects of GLP‐1R agonists on autophagy have been studied in several metabolic tissues 81 , 82 , 83 . Recent studies showed that liraglutide could enhance the autophagy level of insulinoma cells or β‐cells as well 84 , 85 . The RAPGEF4–EPAC2–calcineurin–TFEB axis has been implicated in GLP‐1R agonist‐induced autophagy activation and amelioration of lysosomal stress in β‐cells imposed by glucolipotoxicity 85 (Figure 3).

It is well known that GLP‐1R agonists can increase β‐cell mass 86 ; however, the relationship between increased β‐cell mass and autophagy induction by GLP‐1R agonists is unclear. GLP‐1R agonists can enhance β‐cell mass through increased β‐cell proliferation and neogenesis 87 , which might be mediated by Pdx1, Akt, CREB and IRS2, independent of autophagy 86 , 88 . Intriguingly, calcineurin activation and NFATc dephosphorylation might also play a role in β‐cell proliferation by GLP‐1R agonists through FOXM1, CCNA1, cyclin and CDK55 (Figure 3). This result is intriguing, as calcineurin activation might also activate autophagy 49 , 89 . However, as activation of the calcineurin–NFAT downstream signal related to β‐cell growth has been observed in juvenile, but not in adult, islets, its therapeutic role needs to be further examined. Although autophagy might not directly contribute to the increased β‐cell proliferation, autophagy might still contribute to the increased β‐cell mass through inhibition of β‐cell apoptosis 88 , 90 . Molecular mechanisms of the inhibition of β‐cell apoptosis by GLP‐1R agonists include phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase or protein kinase B activation, BAD inactivation and forkhead box protein O1 inhibition 91 . Enhancement of autophagy by GLP‐1R agonists might reduce ER stress 92 , which could contribute to the reduced apoptosis of stressed β‐cells.

With respect to diabetes complications, GLP‐1R agonists have been reported to have beneficial effects on diabetic kidney disease through the promotion of autophagy 93 . As the potential autophagy‐enhancing effect of GLP‐1R agonists has been observed in tissues other than β‐cells, such as neuronal cells, cardiomyocytes or hepatocytes, GLP‐1R agonists might have therapeutic potential in the management not only of metabolic diseases, but also of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson disease, cardiomyopathy and so on 69 .

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are a novel class of antidiabetic drugs that increase the urinary loss of glucose and induce a starvation‐like state. SGLT2 inhibitors are widely used to induce weight loss, and reduce the risks of cardiovascular events and the severity of diabetic kidney disease 94 . SGLT2 inhibitors have been reported to enhance autophagic activity through AMPK activation 95 (Figure 3). SGLT2 inhibitors have also been reported to induce autophagy in diabetic heart and kidney tissues, which might be related to the cardio‐ or renoprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors 96 , 97 . For instance, empagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, has been reported to enhance mitophagy through the AMPK–ULK1–FUNDC1 pathway, contributing to the amelioration of cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion injury 98 . SGLT2 inhibitors have been reported to activate autophagy through sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) activation and reverse high‐glucose‐induced downregulation of SIRT1 in renal tubular cells 96 , 99 (Figure 3). SIRT1 can promote autophagy gene expression through deacetylation of PGC‐1α 100 .

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ agonist

Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPAR‐γ) is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of genes involved in adipogenesis and lipid uptake 101 . Rosiglitazone, a representative PPAR‐γ agonist, has been reported to protect β‐cells against lipoapoptosis by the activation of autophagy through AMPK 78 . On the contrary, inhibition of autophagy by rosiglitazone has also been reported 102 , 103 .

Pioglitazone, another PPAR‐γ agonist, has been reported to ameliorate fatty liver disease through autophagy activation 104 . Pioglitazone has also been reported to ameliorate cellular damage caused by the accumulation of advanced glycosylation end‐products in diabetes through autophagy promotion 105 .

PPAR‐α agonist

PPAR‐α activators are widely‐used drugs against hypertriglyceridemia, and enhance the transcriptional activity of genes that play crucial roles in fatty acid oxidation, lipid transport and ketosis 106 . PPAR‐α is induced by fasting 107 , suggesting a relationship with autophagy induction by fasting. PPAR‐α has been shown to bind promoters of several autophagy genes. Furthermore, GW7647, a PPAR‐α agonist, has been reported to reverse feeding‐induced autophagy suppression 108 . Fenofibrate, another well‐known PPAR‐α agonist, has also been reported to ameliorate hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in a TFEB‐dependent manner, which is associated with the reshaping of the gut microbiome 109 , 110 . In contrast, farnesoid X receptor agonist was reported to compete with PPAR‐α for binding to promoters of autophagy genes and suppress autophagy 108 .

Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors

As GLP‐1 is a substrate of dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP4), DPP‐4 inhibitors can elevate serum GLP‐1 level (Figure 3). However, the relationship between the elevation of serum GLP‐1 by DPP‐4 inhibitors and the well‐known effect of DPP‐4 in the increase of β‐cell mass 87 , 111 is unclear. The DPP‐4 inhibitor, linagliptin, used alone or in combination with SGLT2 inhibitors, has been reported to enhance the levels of autophagosome and autolysosome in glomerular cells or podocytes of diabetic mice. This is accompanied by the mitigation of renal changes, such as mesangial expansion, effacement of podocyte foot process or urinary albuminuria 112 , which might contribute to the beneficial effects of SGLT2 or DPP‐4 inhibitors.

AUTOPHAGY IN TYPE 1 DIABETES

Although most studies on autophagy in β‐cells have been carried out in the context of type 2 diabetes, changes in autophagy and lysosomal function in pancreatic β‐cells of type 1 diabetes animals or type 1 diabetes patients have also been investigated 113 . In pancreatic islets of non‐obese diabetic mice, a classical animal model of type 1 diabetes, increased numbers of autophagosomes and p62 were observed, suggesting impaired autophagic activity. LC3 co‐localization with LAMP1 was reduced in pancreatic islets of non‐obese diabetic mice and in those of patients with type 1 diabetes, which implies impairment of the lysosomal steps of autophagy. Lipofuscin accumulation was observed even in pancreatic islets of autoantibody‐positive organ donors, suggesting that autophagy is dysregulated early in type 1 diabetes before the development of overt diabetes.

In addition to global autophagy, the role of mitophagy has been studied in pancreatic β‐cells of animal models of type 1 diabetes. Clec16A, which has been reported to play a role in mitophagy, is a type 1 diabetes susceptibility gene 114 . Insulin release from islets of β‐cell‐specific Clec16A‐KO mice was impaired, which resulted in impaired glucose tolerance in vivo 58 . In contrast, overexpression of Clec16A could protect islet cells from cytokine‐induced cell death 115 . Other studies reported that the main target cells of CLEC16A are thymic epithelial cells, and knockdown of Clec16A in thymic epithelial cells results in defective autophagy and increased negative selection of T cells, leading to a reduced incidence of autoimmune diabetes 116 . Indeed, Clec16A is associated with the development not only of type 1 diabetes, but also of other autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, Addison's disease, celiac disease, primary biliary cirrhosis or Crohn's disease 117 . This suggests a role for Clec16A‐mediated autophagy or mitophagy in a broad spectrum of immune responses and lymphoid cells. Although these results suggest a role for dysregulated autophagy, mitophagy or lysosomal function in the pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes, the detailed mechanism and functional significance of Clec16A‐mediated mitophagy or autophagy in the immune regulation and in the development of autoimmune diseases remains to be determined.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Changes in autophagy associated with diabetes and their pathophysiological role have been extensively studied; however, a unanimous consensus has not been reached. The role of autophagy of pancreatic β‐cells in diabetes has also been widely studied. There appears to be a consensus regarding the homeostatic role of (macro)autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells, as it preserves the function of organelles, such as mitochondria or ER, and regulates the appropriate insulin response to a glucose challenge. However, the detailed role and regulation of autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells still remain elusive, particularly for selective autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells. The molecular mechanism and functional role of the minor types of autophagy that might occur in hormone secretory cells, including pancreatic β‐cells, such as crinophagy, are also far from clear. It should also be kept in mind that lysosomal dysfunction is prevalent in diverse diseases, including metabolic diseases or aging 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 . Excessive activation of the proximal steps of autophagy alone might result in aggravated accumulation of autophagic intermediates that can cause harmful effects.

Nevertheless, valuable new discoveries regarding the molecular machinery and regulation of diverse types of autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells are being reported. The development of clinically applicable methods for modulating autophagy of pancreatic β‐cells for the treatment of human diabetes might soon be feasible.

DISCLOSURE

M‐SL is the CEO of LysoTech, Inc. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (NRF‐2019R1A2C3002924 and Rs‐2023‐00219563). M‐S Lee is the recipient of the Korea Drug Development Fund from the Ministry of Science & ICT, Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy and Ministry of Health & Welfare (HN22C0278), and a grant from the Faculty Research Assistance Program of Soonchunhyang University (20220346).

REFERENCES

- 1. Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011; 147: 728–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goginashvili A, Zhang Z, Erbs E, et al. Insulin granules. Insulin secretory granules control autophagy in pancreatic β cells. Science 2015; 347: 878–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yamaguchi H, Arakawa S, Kanaseki T, et al. Golgi membrane‐associated degradation pathway in yeast and mammals. EMBO J 2016; 35: 1991–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yamamoto S, Kuramoto K, Wang N, et al. Autophagy differentially regulates insulin production and insulin sensitivity. Cell Rep 2018; 23: 3286–3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016; 12: 1–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yu L, McPhee CK, Zheng L, et al. Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR. Nature 2010; 465: 942–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Narendra DP, Youle RJ. Targeting mitochondrial dysfunction: Role for PINK1 and Parkin in mitochondrial quality control. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011; 14: 1929–1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wei H, Liu L, Chen Q. Selective removal of mitochondria via mitophagy: Distinct pathways for different mitochondrial stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1853: 2784–2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pickrell AM, Youle RJ. The roles of PINK1, parkin, and mitochondrial fidelity in Parkinson's disease. Neuron 2015; 85: 257–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma K, Chen G, Li W, et al. Mitophagy, mitochondrial homeostasis, and cell fate. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020; 8: 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oh S‐J, Park K, Sonn SK, et al. Pancreatic β‐cell mitophagy as an adaptive response to metabolic stress and the underlying mechanism that involves lysosomal Ca2+ release. Exp Mol Med 2023; 55: 1922–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu H, Wang Y, Li W, et al. Deficiency of mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 impairs mitochondrial quality and aggravates dietary‐induced obesity and metabolic syndrome. Autophagy 2019; 15: 1882–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tong B, Zhang Z, Li X, et al. FUNDC1 modulates mitochondrial defects and pancreatic β‐cell dysfunction under lipotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2023; 672: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fumagalli F, Noack J, Bergmann T, et al. Translocon component Sec62 acts in endoplasmic reticulum turnover during stress recovery. Nat Cell Biol 2016; 18: 1173–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grumati P, Morozzi G, Hölper S, et al. Full length RTN3 regulates turnover of tubular endoplasmic reticulum via selective autophagy. Elife 2017; 6: e25555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khaminets A, Heinrich T, Mari M, et al. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum turnover by selective autophagy. Nature 2015; 522: 354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jiang X, Wang X, Ding X, et al. FAM134B oligomerization drives endoplasmic reticulum membrane scission for ER‐phagy. EMBO J 2020; 39: e102608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoshino A, Ariyoshi M, Okawa Y, et al. Inhibition of p53 preserves Parkin‐mediated mitophagy and pancreatic β‐cell function in diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 3116–3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jung HS, Chung KW, Kim JW, et al. Loss of autophagy diminishes pancreatic b‐cell mass and function with resultant hyperglycemia. Cell Metab 2008; 8: 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quan W, Hur KY, Lim Y, et al. Autophagy deficiency in beta cells leads to compromised unfolded protein response and progression from obesity to diabetes in mice. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ebato C, Uchida T, Arakawa M, et al. Autophagy is important in islet homeostasis and compensatory increase of beta cell mass in response to high‐fat diet. Cell Metab 2008; 8: 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Choi SE, Lee SM, Lee YJ, et al. Protective role of autophagy in palmitate‐induced INS‐1 beta cell death. Endocrinology 2009; 150: 126–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zummo FP, Cullen KS, Honkanen‐Scott M, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 protects pancreatic β‐cells from death by increasing autophagic flux and restoring lysosomal function. Diabetes 2017; 66: 1272–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. King BC, Kulak K, Krus U, et al. Complement component C3 is highly expressed in human pancreatic islets and prevents β cell death via ATG16L1 interaction and autophagy regulation. Cell Metab 2018; 29: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bachar‐Wikstrom E, Wikstrom JD, Ariav Y, et al. Stimulation of autophagy improves endoplasmic reticulum stress‐induced diabetes. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1227–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bartolome A, Guillen C, Benito M. Autophagy plays a protective role in endoplasmic reticulum stress‐mediated pancreatic β cell death. Autophagy 2012; 8: 1757–1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kong FJ, Wu JH, Sun SY, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum stress/autophagy pathway is involved in cholesterol‐induced pancreatic β‐cell injury. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 44746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shrestha N, Torres M, Zhang J, et al. Integration of ER protein quality control mechanisms defines β cell function and ER architecture. J Clin Invest 2023; 133: e163584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fujimoto K, Hanson PT, Tran H, et al. Autophagy regulates pancreatic beta cell death in response to Pdx1 deficiency and nutrient deprivation. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 27664–27673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tenemura M, Ohmura Y, Deguchi T, et al. Rapamycin causes upregulation of autophagy and impairs islets function both in vitro and in vivo. Am J Transplant 2012; 12: 102–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Israeli T, Riahi Y, Garzon P, et al. Nutrient sensor mTORC1 regulates insulin secretion by modulating β‐cell autophagy. Diabetes 2022; 71: 453–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pearson GL, Mellett N, Chu KY, et al. Lysosomal acid lipase and lipophagy are constitutive negative regulators of glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2014; 57: 129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Riahi Y, Wikstrom JD, Bachar‐Wikstrom E, et al. Autophagy is a major regulator of beta cell insulin homeostasis. Diabetologia 2016; 59: 1480–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Westermark P, Andersson A, Westernark GT. Islet amyloid polypeptide, islet amyloid, and diabetes mellitus. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 795–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rubinsztein DC. The roles of intracellular protein‐degradation pathways in neurodegeneration. Nature 2006; 443: 780–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim J, Cheon H, Jeong YT, et al. Amyloidogenic peptide oligomer accumulation in autophagy‐deficient β‐cells leads to diabetes. J Clin Invest 2014; 125: 3311–3324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rivera JF, Costes S, Gurlo T, et al. Autophagy defends pancreatic β‐cells from human islet amyloid polypeptide‐induced toxicity. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 3489–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gurlo T, Rivera JF, Butler AE, et al. CHOP contributes to, but is not the only mediator of, IAPP induced β‐cell apoptosis. Mol Endocrinol 2016; 30: 446–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kayatekin C, Amasino A, Gaglia G, et al. Translocon declogger Ste24 protects against IAPP oligomer‐induced proteotoxicity. Cell 2018; 173: 62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL‐1b in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol 2010; 11: 897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Lipid membranes modulate the structure of islet amyloid polypeptide. Biochemistry 2005; 44: 12113–12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park K, Verchere CB. Identification of a heparin binding domain in the N‐terminal cleavage site of pro‐islet amyloid polypeptide. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 16611–16616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shigihara N, Fukunaka A, Hara A, et al. Human IAPP‐induced pancreatic beta‐cell toxicity and its regulation by autophagy. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 3634–3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pearson GL, Gingerich MA, Walker EM, et al. A selective look at autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells. Diabetes 2021; 70: 1229–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Su Y, Misumi Y, Ueda M, et al. The occurrence of islet amyloid polypeptide amyloidosis in Japanese subjects. Pancreas 2012; 41: 971–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Masini M, Bugliani M, Lupi R, et al. Autophagy in human type 2 diabetes pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 2009; 52: 1083–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ji J, Petropavlovskaia M, Khatchadourian A, et al. Type 2 diabetes is associated with suppression of autophagy and lipid accumulation in β‐cells. J Cell Mol Med 2018; 23: 2890–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Corsa CAS, Pearson GL, Renberg A, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin is dispensable for metabolic homeostasis in murine pancreatic β cells and adipocytes. J Biol Chem 2019; 294: 7296–7307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Settembre C, De Cegli R, Mansueto G, et al. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation‐induced autoregulatory loop. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15: 647–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nezich CL, Wang C, Fogel A, et al. MiT/TFE transcription factors are activated during mitophagy downstream of Parkin and Atg5. J Cell Biol 2015; 210: 435–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang X, Cheng X, Yu L, et al. MCOLN1 is a ROS sensor in lysosomes that regulates autophagy. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Park K, Lim H, Kim J, et al. Essential role of lysosomal Ca2+‐mediated TFEB activation in mitophagy and functional adaptation of pancreatic β‐cells to metabolic stress. Nat Commun 2022; 13: 1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jenssen T, Hartmann A. Post‐transplant diabetes mellitus in patients with solid organ transplants. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2019; 15: 172–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Park K, Sonn SK, Seo S, et al. Impaired TFEB activation and mitophagy as a cause of PPP3/calcineurin inhibitor‐induced pancreatic β‐cell dysfunction. Autophagy 2022; 19: 1444–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dai C, Hang Y, Shostak A, et al. Age‐dependent human β cell proliferation induced by glucagon‐like peptide 1 and calcineurin signaling. J Clin Invest 2017; 127: 3835–3844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pearson G, Chai B, Vozheiko T, et al. Clec16a, Nrdp1, and USP8 form a ubiquitin‐dependent tripartite complex that regulates β‐cell mitophagy. Diabetes 2018; 67: 265–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Soleimanpour SA, Ferrari AM, Raum JC, et al. Diabetes susceptibility genes Pdx1 and Clec16a function in a pathway regulating mitophagy in β‐cells. Diabetes 2015; 64: 3475–3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Soleimanpour SA, Gupta A, Bakay M, et al. The diabetes susceptibility gene Clec16a regulates mitophagy. Cell 2014; 157: 1577–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim S, Naylor SA, DiAntonio A. Drosophila Golgi membrane protein Ema promotes autophagosomal growth and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: E1072–E1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cunningham CN, Williams JM, Knupp J, et al. Cells deploy a two‐pronged strategy to rectify misfolded proinsulin aggregates. Mol Cell 2019; 75: 442–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Parashar S, Chidambaram R, Chen S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum tubules limit the size of misfolded protein condensates. Elife 2021; 10: e71642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bainton DF. The discovery of lysosome. J Cell Biol 1981; 91: 66s–76s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Orci L, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, et al. Insulin, not C‐peptide, is present in crinophagic bodies of the pancreatic b‐cell. J Cell Biol 1984; 98: 222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Schnell AH, Swenne I, Borg LA. Lysosomes and pancreatic islet function. A quantitative estimation of crinophagy in the mouse pancreatic B‐cell. Cell Tissue Res 1985; 239: 537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rocchi A, Yamamoto S, Ting T, et al. A Becn1 mutation mediates hyperactive autophagic sequestration of amyloid oligomers and improved cognition in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS Genet 2017; 13: e1006962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lim Y‐M, Lim H‐J, Hur KY, et al. Systemic autophagy insufficiency compromises adaptation to metabolic stress and facilitates progression from obesity to diabetes. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sahu R, Kaushik S, Clement CC, et al. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell 2011; 20: 131–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fernández‐Fernández R, Gragera M, Ochoa‐Ibarrola L, et al. Hsp70 ‐ a master regulator in protein degradation. FEBS Lett 2017; 591: 2648–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Park K, Lee M‐S. Current status of autophagy enhancers in metabolic disorders and other diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022; 10: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kalender A, Selvaraj A, Kim SY, et al. Metformin, independent of AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 in a rag GTPase‐dependent manner. Cell Metab 2010; 11: 390–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, et al. Role of AMP‐activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest 2003; 108: 1167–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP‐activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science 2011; 331: 456–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, et al. Differential regulation of distinct Vps34 complex by AMPK in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell 2013; 152: 290–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Howell JJ, Hellberg K, Turner M, et al. Metformin inhibits hepatic mTORC1 signaling via dose‐dependent mechanisms involving AMPK and the TSC complex. Cell Metab 2017; 25: 463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, et al. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of ULK1. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13: 132–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Paquette M, El‐Houjeiri L, Zirden LC, et al. AMPK‐dependent phosphorylation is required for transcriptional activation of TFEB and TFE3. Autophagy 2021; 17: 3957–3975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Jiang Y, Huang W, Wang J, et al. Metformin plays a dual role in MIN6 pancreatic b cell function through AMPK‐dependent autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2014; 10: 268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wu J, Wu JJ, Yang LJ, et al. Rosiglitazone protects against palmitate‐induced pancreatic beta‐cell death by activation of autophagy via 5′‐AMP‐activated protein kinase modulation. Endocrine 2013; 44: 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang D, Ma Y, Liu J, et al. Metformin alleviates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in a mouse model of high‐fat diet‐induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by promoting transcription factor EB‐dependent autophagy. Front Pharmacol 2021; 12: 689111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lim SW, Jin L, Jin J, et al. Effect of exendin‐4 on autophagy clearance in beta cell of rats with tacrolimus‐induced diabetes mellitus. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 29921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fang Y, Ji L, Zhu C, et al. Liraglutide alleviates hepatic steatosis by activating the TFEB‐regulated autophagy‐lysosomal pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020; 8: 602574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Noyan‐Ashraf MH, Shikatani EA, Schuiki I, et al. A glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog reverses the molecular pathology and cardiac dysfunction of a mouse model of obesity. Circulation 2013; 127: 74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sharma S, Mells JE, Fu PP, et al. GLP‐1 analogs reduce hepatocyte steatosis and improve survival by enhancing the unfolded protein response and promoting macroautophagy. PLoS One 2011; 6: e25269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Chen Z‐F, Li Y‐B, Han J‐Y, et al. Liraglutide prevents high glucose level induced insulinoma cells apoptosis by targeting autophagy. Chin Med J 2013; 126: 937–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Zummo FP, Krishnanda SI, Georgiou M, et al. Exendin‐4 stimulates autophagy in pancreatic β‐cells via the RAPGEF/EPAC‐Ca2+‐PPP3/calcineurin‐TFEB axis. Autophagy 2021; 18: 799–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Park S, Dong X, Fisher TL, et al. Exendin‐4 uses Irs2 signaling to mediate pancreatic β cell growth and function. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 1159–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Cho JM, Jang HW, Cheon H, et al. A novel dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor DA‐1229 ameliorates streptozotocin‐induced diabetes by increasing β‐cell replication and neogenesis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011; 91: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Li Y, Cao X, Li L‐X, et al. Beta‐cell Pdx1 expression is essential for the glucoregulatory, proliferative, and cytoprotective actions of glucagon‐like peptide‐1. Diabetes 2005; 54: 482–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Settembre C, Di Malta C, Polito VA, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science 2011; 332: 1429–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kim J, Park K, Kim MJ, et al. An autophagy enhancer ameliorates diabetes of human IAPP‐transgenic mice through clearance of amyloidogenic oligomer. Nat Commun 2021; 12: 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kapodistria K, Tsilibary E‐P, Kotsopoulou E, et al. Liraglutide, a human glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analogue, stimulates AKT‐dependent survival signalling and inhibits pancreatic β‐cell apoptosis. J Cell Mol Med 2018; 22: 2970–2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yusta B, Baggio LL, Estall JL, et al. GLP‐1 receptor activation improves beta cell function and survival following induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab 2006; 4: 391–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yamada S, Tanabe J, Ogura Y, et al. Renoprotective effect of GLP‐1 receptor agonist, liraglutide, in early‐phase diabetic kidney disease in spontaneously diabetic Torii fatty rats. Clin Exp Neurol 2021; 25: 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Vallon V, Verma S. Effects of SGLT2 inhibitors on kidney and cardiovascular function. Annu Rev Physiol 2021; 83: 503–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hawley SA, Ford RJ, Smith BK, et al. The Na+/glucose cotransporter inhibitor canagliflozin activates AMPK by inhibiting mitochondrial function and increasing cellular AMP levels. Diabetes 2016; 65: 2784–2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Packer M. Autophagy‐dependent and ‐independent modulation of oxidative and organellar stress in the diabetic heart by glucose‐lowering drugs. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2020; 19: 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Packer M. Mitigation of the adverse consequences of nutrient excess on the kidney: A unified hypothesis to explain the renoprotective effects of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. Am J Nephrol 2020; 51: 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Cai C, Guo Z, Chang X, et al. Empagliflozin attenuates cardiac microvascular ischemia/reperfusion through activating the AMPKα1/ULK1/FUNDC1/mitophagy pathway. Redox Biol 2022; 52: 102288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Umino H, Hasegawa K, Minakuchi H, et al. High basolateral glucose increases sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 and reduces Sirtuin‐1 in renal tubules through glucose transporter‐2 detection. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 6791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Morselli E, Mariño G, Bennetzen MV, et al. Spermidine and resveratrol induce autophagy by distinct pathways converging on the acetylproteome. J Cell Biol 2011; 192: 615–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Spiegelman BM. PPAR‐gamma: Adipogenic regulator and thiazolidinedione receptor. Diabetes 1998; 47: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ji J, Xue TF, Guo XD, et al. Antagonizing peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor γ facilitates M1‐to‐M2 shift of microglia by enhancing autophagy via the LKB1‐AMPK signaling pathway. Aging Cell 2018; 17: e12774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Li H, Zhang Q, Yang X, et al. PPAR‐gamma agonist rosiglitazone reduces autophagy and promotes functional recovery in experimental traumaticspinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett 2018; 650: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hsiao P‐J, Chiou H‐YC, Jiang H‐J, et al. Pioglitazone enhances cytosolic lipolysis, β‐oxidation and autophagy to ameliorate hepatic steatosis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 9030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Xu L, Xu K, Wu Z, et al. Pioglitazone attenuates advanced glycation end products‐induced apoptosis and calcification by modulating autophagy in tendon‐derived stem cells. J Cell Mol Med 2020; 24: 2240–2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Torra P, Gervois P, Staels B. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha in metabolic disease, inflammation, atherosclerosis and aging. Curr Opin Lipidol 2000; 10: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, et al. Peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor alpha mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest 1999; 103: 1489–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Lee JM, Wagner M, Xiao R, et al. Nutrient‐sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature 2014; 516: 112–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Yoo J, Jeong IK, Ahn KJ, et al. Fenofibrate, a PPARα agonist, reduces hepatic fat accumulation through the upregulation of TFEB‐mediated lipophagy. Metabolism 2021; 120: 154798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Zhang D, Ma Y, Liu J, et al. Fenofibrate improves hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and shapes the gut microbiome via TFEB‐autophagy in NAFLD mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2023; 960: 176159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Kim DH, Lee J‐C, Lee M‐K, et al. Treatment of autoimmune diabetes by toll‐like receptor 2 tolerance in conjunction with dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibition. Diabetologia 2012; 55: 3308–3317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Korbut AI, Taskaeva IS, Bgatova NP, et al. SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin and DPP4 inhibitor linagliptin reactivate glomerular autophagy in db/db mce, a model of type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21: 3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Muralidharan C, Conteh AB, Marasco MR, et al. Pancreatic beta cell autophagy is impaired in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 2021; 64: 865–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Hakonarson H, Grant SF, Bradfield JP, et al. A genome‐wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature 2007; 448: 591–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Sidarala V, Pearson GL, Parekh VS, et al. Mitophagy protects β cells from inflammatory damage in diabetes. JCI Insight 2020; 5: e141138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Schuster C, Gerold KD, Schober K, et al. The autoimmunity‐associated gene Clec16A modulates thymic epithelial cell autophagy and alters T cell selection. Immunity 2015; 42: 942–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Pandey R, Bakay M, Hakonarson H. CLEC16A‐an emerging master regulator of autoimmunity and neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24: 8224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Bordi M, Berg MJ, Mohan PS, et al. Autophagy flux in CA1 neurons of Alzheimer hippocampus: Increased induction overburdens failing lysosomes to propel neuritic dystrophy. Autophagy 2016; 12: 2467–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Fernando R, Castro JP, Flore T, et al. Age‐related maintenance of the autophagy‐lysosomal system is dependent on skeletal muscle type. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020; 2020: 4908162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hütter E, Skovbro M, Lener B, et al. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial impairment can be separated from lipofuscin accumulation in aged human skeletal muscle. Aging Cell 2007; 6: 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Kim J, Kim SH, Kang H, et al. TFEB‐GDF15 axis protects against obesity and insulin resistance as a lysosomal stress response. Nat Metab 2021; 3: 410–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Liu WJ, Shen TT, Chen RH, et al. Autophagy‐lysosome pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells is disrupted by advanced glycation end products in diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 20499–20510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Zhao Y, Zhang W, Jia Q, et al. High dose vitamin E attenuates diabetic nephropathy via alleviation of autophagic stress. Front Physiol 2019; 9: 1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]