Abstract

Objective:

To delineate the comprehensive phenotypic spectrum of SYNGAP1-related disorder in a large patient cohort aggregated through a digital registry.

Methods:

We obtained de-identified patient data from an online registry. Data were extracted from uploaded medical records. We reclassified all SYNGAP1 variants using American College of Medical Genetics criteria and included patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic (P/LP) single nucleotide variants or microdeletions incorporating SYNGAP1. We analyzed neurodevelopmental phenotypes, including epilepsy, intellectual disability (ID), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), behavioral disorders, and gait dysfunction for all patients with respect to variant type and location within the SynGAP1 protein.

Results:

We identified 147 patients (50% male, median age 8 years) with P/LP SYNGAP1 variants from 151 individuals with data available through the database. One hundred nine were truncating variants and 22 were missense. All patients were diagnosed with global developmental delay (GDD) and/or ID, and 123 patients (84%) were diagnosed with epilepsy. Of those with epilepsy, 73% of patients had GDD diagnosed before epilepsy was diagnosed. Other prominent features included autistic traits (n = 100, 68%), behavioral problems (n = 100, 68%), sleep problems (n = 90, 61%), anxiety (n = 35, 24%), ataxia or abnormal gait (n = 69, 47%), sensory problems (n = 32, 22%), and feeding difficulties (n = 69, 47%). Behavioral problems were more likely in those patients diagnosed with anxiety (odds ratio [OR] 3.6, p = .014) and sleep problems (OR 2.41, p = .015) but not necessarily those with autistic traits. Patients with variants in exons 1–4 were more likely to have the ability to speak in phrases vs those with variants in exons 5–19, and epilepsy occurred less frequently in patients with variants in the SH3 binding motif.

Significance:

We demonstrate that the data obtained from a digital registry recapitulate earlier but smaller studies of SYNGAP1-related disorder and add additional genotype–phenotype relationships, validating the use of the digital registry. Access to data through digital registries broadens the possibilities for efficient data collection in rare diseases.

Keywords: developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, epilepsy with eyelid myoclonia, epilepsy with myoclonic–atonic seizures, genetic generalized epilepsy, intellectual disability, SYNGAP1

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Since the initial description of SYNGAP1-related disorder in 2009, more than 200 affected individuals have been reported.1 The SYNGAP1 gene on chromosome 6p21.32 encodes the synaptic GTPase activating protein (SynGAP), which plays a role in regulating the function of synapses of excitatory neurons and in regulating neuronal development.2–4 Pathogenic SYNGAP1 variants cause SYNGAP1-related disorder through genetic haploinsufficiency. Most disease-causing SYNGAP1 variants reported to date are truncating, with a smaller proportion of missense and splice-site variants, followed by copy number variants (CNVs) that include the gene.1,5

Although initially described as a gene associated with non-syndromic intellectual disability (ID), in 2010, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) was added to the SYNGAP1 gene description. By 2013, pathogenic SYNGAP1 variants were described as a cause for developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE).6–10 Analyzing a cohort of 57 patients, Vlaskamp and colleagues described the epilepsy phenotype of SYNGAP1-related disorder as a DEE and highlighted the presence of eyelid myoclonia with absences and myoclonic–atonic seizures in patients with this disorder as well as a description of seizures triggered by eating or chewing.5,11 Some individuals may be well controlled on one anti-seizure medication (ASM), but many are refractory to ASMs.

What has become evident from these earliest descriptions of SYNGAP1-related disorder is a pattern of global developmental delay (GDD) followed by a diagnosis of epilepsy in more than 80% of patients at a median age of 2 years, with variable neurodevelopmental co-morbidities including mild to severe ID, ASD, behavioral problems, sleep problems, hypotonia, and ataxia and gait abnormalities.5

With the promise of precision and gene-specific therapies for SYNGAP1-related disorder and other genetic neurodevelopmental syndromes, the importance of prompt and accurate diagnosis and prognosis and the need for objectively measurable clinical outcomes for trials has become evident. In this study of the largest cohort of individuals with SYNGAP1-related disorder aggregated to date, we sought to comprehensively characterize the most prominent features and clinical course of individuals with SYNGAP1-related disorder. As the number of patients diagnosed with SYNGAP1 variants continues to grow in the era of next-generation sequencing, efficient measures to enroll families and aggregate high-quality data will allow for accurate delineation of key phenotypic features. Here we describe the key features of a cohort of individuals harboring SYNGAP1 variants who were enrolled by their families in a gene-specific database.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Medical record collection and data extraction

Parents or guardians of children and adults with a diagnosis of SYNGAP1-related disorder enrolled in the SynGAP Research Fund Database, hosted by Ciitizen, a wholly owned subsidiary of Invitae. In brief, Ciitizen is a patient-centric, real-world data platform that collects longitudinal medical records on behalf of participants by leveraging right of access granted by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Annotated data from unstructured medical records are transformed using internationally recognized terminologies and constrained to a standard data model: diagnoses, observations, and procedures were mapped to SNOMED CT (US Edition, version 2022_03_01); medications were mapped to RxNorm (version 20AA_220307F); and measurements were mapped to LOINC (version 273). All extracted data are verified by two clinicians with relevant training, who perform source document verification and confirm accuracy of annotation. The database has received an institutional review board (IRB) determination of exemption. Study data were collected from the Ciitizen database and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools hosted at Boston Children’s Hospital.12,13

2.2 |. Patient ascertainment and variant classification

We obtained approval from the Boston Children’s Hospital IRB to obtain de-identified clinical data from the Ciitizen database. The Ciitizen platform is available to any individual with a rare neurodevelopmental disorder. However, most participants in this study were recruited in collaboration with SynGAP Research Fund, a global patient advocacy organization. Outreach to individuals with a likely pathogenic or pathogenic SYNGAP1 variant identified at Invitae via routine clinical testing represented an additional recruitment channel.

SYNGAP1 variants were mapped onto the longest isoform 1 of SYNGAP1 (NM_006772.2). CNVs were described using the nomenclature of the Genome Reference Consortium Human Reference sequence version 37 (GRCh37/hg19).

Variant classification was determined by a genetic counselor or physician trained in the American College of Genetic and Genomics (ACMG) variant classification criteria (KNW). We included patients with pathogenic or likely pathogenic (P/LP) SYNGAP1 variants or chromosome 6p21.32 microdeletions that included SYNGAP1 and other genes. Patients with benign variants and variants of uncertain significance (VUS) in SYNGAP1 were excluded, as were patients with P/LP variants in other gene(s) associated with neurodevelopmental disorders.

2.3 |. Genotype–phenotype relationships

We analyzed genotype–phenotype relationships in patient groups according to variant type: truncating (comprising nonsense and frameshift variants), missense variants and in-frame insertions/deletions, intronic variants, and chromosome 6p21.32 microdeletions that included SYNGAP1. GDD and ID phenotypes were determined based on diagnosis codes and assessments within the medical record with corroboration of developmental milestone attainment (or lack thereof) and documentation of clinical exam findings. Epilepsy phenotypes were determined based on definitions from the 2022 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) Classification of Epilepsies.14

For a secondary analysis comparing phenotypic features between individuals with predicted loss-of-function variants in exons 1–4 vs exons 5–19, we included all truncating, frameshift, and missense variants predicted to cause loss-of-function through nonsense mediated decay based on in silico predictions in this analysis.

We performed logistic regression and fit to cumulative event transformations of Kaplan–Meier curves for phenotype analysis of the total cohort. We utilized logistic regression and Fisher’s exact tests to analyze for significant differences in proportions across dichotomous and multiple groups, respectively, and the Kruskal–Wallis test to analyze continuous outcomes (e.g., age) across the groups. All statistical analyses were conducted in Rstudio version 2021.09.1 + 372.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Cohort description

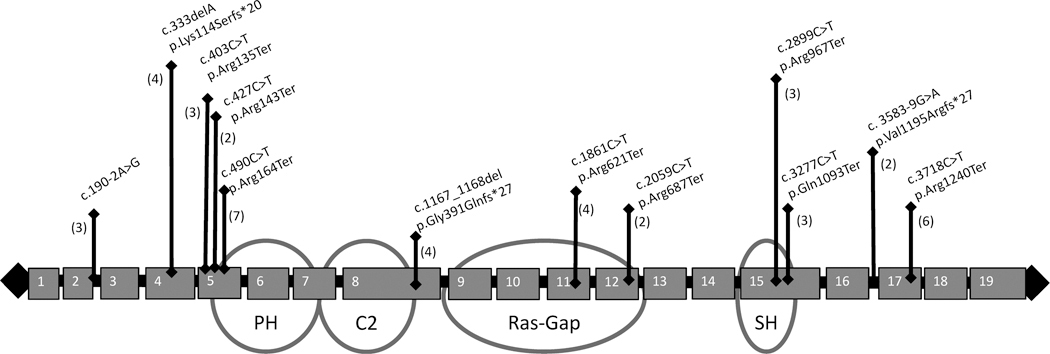

De-identified records from 151 individuals were available through the Ciitizen SYNGAP1 database, last accessed September 2023. We classified 147 individuals (50% male, median age 8 years, ethnicity unavailable) with P/LP variants in SYNGAP1. Inheritance of the SYNGAP1 variants was considered when determining variant classification, with 64 de novo variants, 65 variants of unknown inheritance, and 6 variants inherited from unaffected parents with SYNGAP1 variant mosaicism (3 maternally inherited, 2 paternally inherited, and 1 parental mosaicism with parent unspecified). These individuals’ data were further analyzed: 109 (74%) truncating variants, 22 (15%) missense/in-frame variants, 12 (8%) intronic, and 4 (3%) microdeletions. There were 12 recurrent variants (Figure 1). The recurrent variants include loss-of-function variants (amino acid substitutions generating premature stop codons, frameshift variants, and an out-of-frame deletion resulting in premature truncations), and intronic variants predicted to result in splice-site alterations. SYNGAP1 missense variants were located primarily within the C2 (n = 5) and Ras-Gap (n = 9) domains, with only one missense variant located in the PH domain and none in the SH3-binding motif (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of recurrent pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants in SYNGAP1 in this study. Note that these recurrent variants include amino acid substitutions generating premature stop codons, frameshift variants, an out-of-frame deletion resulting in premature truncations, and intronic variants predicted to result in splice-site alterations. Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of individuals with each variant in the digital registry.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic of missense variants in SYNGAP1 in the registry. Note that most SYNGAP1 missense variants affect the PH, C2, and Ras-Gap domains, and no recurrent variants were observed in this study. AA, amino acid residue.

Within this cohort of 147 individuals, the median age at SYNGAP1-r elated disorder diagnosis was 4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2–7 years). The median current age of the individuals in the cohort was 8 years (IQR 5–13 years), and the youngest individual in the cohort was 30 months of age.

3.2 |. Neurodevelopmental phenotypes

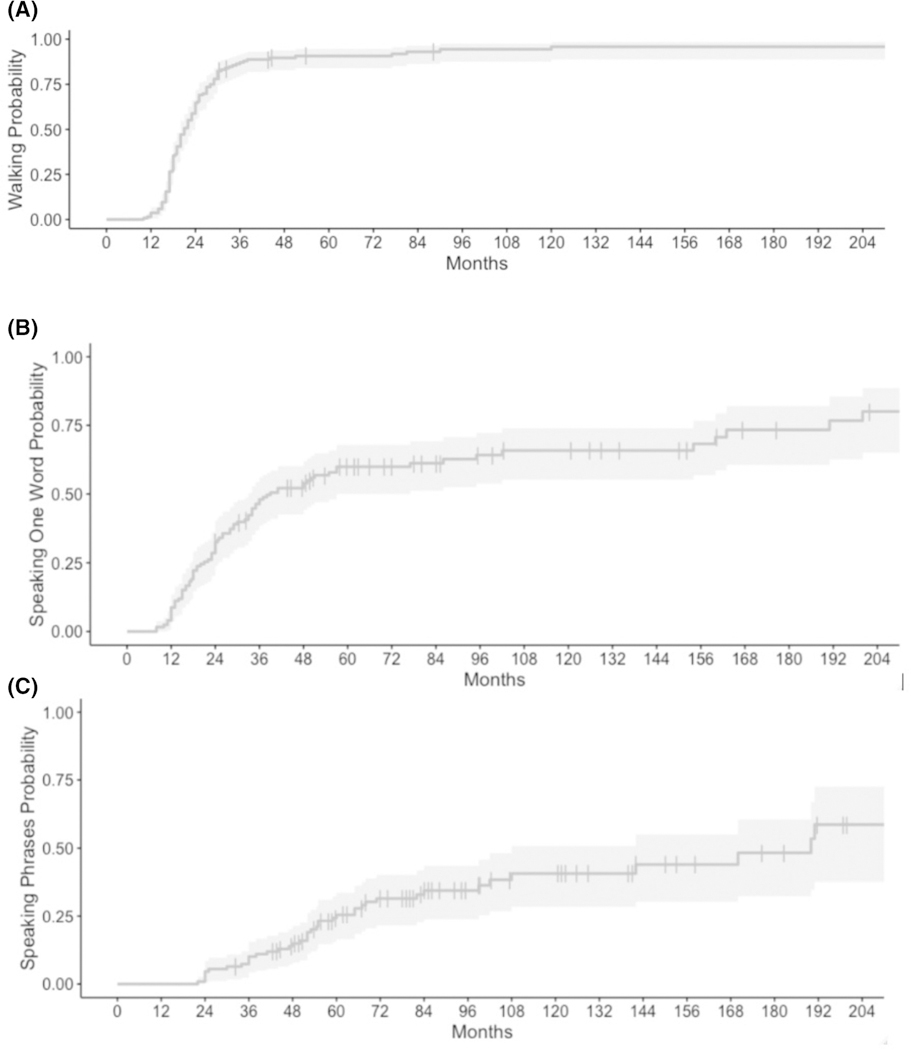

Based on the data extracted from medical records, all patients were diagnosed with GDD and/or ID, and 123 patients (84%) were diagnosed with epilepsy at a median age of 34 months for those diagnosed with epilepsy, as shown in Figure 3A, in which we demonstrate the cumulative incidence of epilepsy diagnosis as patients age. Only six patients (4%) were diagnosed with epilepsy in the first year of life, with the majority being diagnosed between 2 and 5 years of life, as shown in Figure 3A. Note that as part of this figure, vertical dashes indicate the age at which a patient was removed from the data due to not acquiring outcome at age of last data available. Of those with epilepsy, 73% percent of patients = had GDD diagnosed before epilepsy was diagnosed. During the time of the study, 127 patients (86%) had learned to walk, 85 patients (58%) had a vocabulary of at least one word, and 41 patients (28%) were speaking in phrases (Figure 4). Median age at independent walking was 20 months for the cohort (Figure 4). Median age at speaking first word was 24 months for those who are verbal, excluding those who are not verbal from this analysis. Forty-one individuals were able to speak in phrases at a median age of 53 months, including only those able to speak in this analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Probability of neurodevelopmental conditions by age in SYNGAP1-related disorder. Gray shadow indicates 95% confidence interval. Vertical lines indicate removal of an individual from analysis due to data not being available for an individual beyond age at vertical line. Number at risk in strata below graph indicate number of individuals at the age in the cohort who have not yet been diagnosed with the outcome. (A) Epilepsy. (B) Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). (C) Behavioral problems. (D) Ataxia or abnormal gait.

FIGURE 4.

Age at developmental milestone attainment in SYNGAP1-related disorder. Gray shadows indicate 95% confidence interval. Vertical lines indicate removal of an individual from analysis due to data not being available for an individual beyond age at vertical line. (A) Independent walking. (B) Speaking first word. (C) Speaking in phrases.

Autistic traits or ASD was diagnosed in 100 of 147 patients (68%) by a median age of 36 months for those diagnosed with autistic traits or ASD (Figure 3B). Other prominent neurological features included behavioral problems (n = 100 patients, 68%) reported at a median age of 45 months (Figure 5C), sleep problems (n = 90, 61%), anxiety (n = 35, 24%), and ataxia or abnormal gait (n = 69, 47%) diagnosed at a median age of 35 months (Figure 5A). Behavioral problems included unspecified behavioral problems reported by parents (n = 41), aggressive behavior (n = 55), self-injurious behavior (n = 54), and irritability (n = 30). There was not a significantly higher risk of behavioral problems in patients who had autistic traits or ASD compared to patients who did not. Behavioral problems were associated with diagnoses of anxiety (odds ratio [OR] 3.6, p = .014) and sleep problems (OR 2.41, p = .015).

FIGURE 5.

(A) Phenotype of SYNGAP1-rlated disorder associated with SYNGAP1 pathogenic or likely pathogenic single nucleotide variants and microdeletions. *Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the only phenotypic feature of those listed above that has significant difference between types of variants. No significant difference was observed between types of variants for the seizure types. (B) Seizure types seen in the cohort of individuals with SYNGAP1-related disorder. Note that 100 individuals also had seizures of unspecified classification and, because unclassified, were not included here.

Other features included sensory problems (n = 32, 22%) and difficulties with feeding (n = 69 patients, 47%), with seven patients requiring a nasogastric or gastric tube. The sensory problems included 18 individuals with high pain tolerance and 18 individuals with sensory processing disorder (4 individuals had both features). The 68 individuals with feeding difficulty included those with any combination of the following diagnoses: feeding difficulty (n = 44), dysphagia (n = 32), oral aversion (n = 22), failure to thrive (n = 18), feeding problem (n = 17), slow weight gain (n = 11), oropharyngeal dysphagia (n = 6), failure to gain weight (n = 3), and oral dyspraxia (n = 0).

3.3 |. Epilepsy phenotype

One hundred twenty-three individuals (84%) with SYNGAP1-related disorder had a history of epilepsy, with predominantly generalized seizures (Figure 5). The most frequent seizure types reported were absence (typical absence n = 50, 34% and atypical absence n = 29, 20%) and atonic seizures (n = 50, 34%). Reflex seizures, in which an individual has absence seizures with or without eyelid myoclonia in response to chewing or eating, were reported in 35 individuals (24%). Seizures tended to occur frequently, with 92 patients (63%) having at least daily seizures when seizures were at their most frequent, and of those 92 individuals, 23 patients had a maximum of 100 or more absence or atonic seizures daily, and another 38 patients had a maximum seizure frequency between 10 and 100 seizures daily. A minority of patients (n = 7, 5%) had a documented history of status epilepticus.

The patients within this cohort had one of five epilepsy phenotypes: epilepsy with eyelid myoclonia (n = 25, 17%), epilepsy with myoclonic–atonic seizures or Lennox–Gastaut syndrome (n = 31, 21%), DEE not otherwise specified (DEE NOS) (n = 70, 48%), encephalopathy (GDD/ID) without epilepsy (n = 20, 14%), and infantile epileptic spasms syndrome (IESS) (n = 1, .7%). DEE NOS was a category used if patients had clinical features and electroencephalography (EEG) findings that did not clearly fit within the other categories. The epilepsy phenotypes were not significantly different across the groups of patients with different types of SYNGAP1 variants (Fisher’s exact test p-value = .24).

EEG reports were available for 133 individuals. The majority of individuals had EEG reports of generalized spike wave abnormalities, which was seen in 92 patients (63%). The next most common finding was generalized slowing in 56 (38%), which was more commonly seen in combination with epileptiform abnormalities, with five patients having only generalized slowing seen on their first EEG. Twelve patients (8%) had only focal epileptiform discharges or focal slowing seen on EEG. Twenty-one patients (14%) had an initially normal EEG report before subsequently having an abnormal EEG with any combination of the following: generalized seizures (3), focal seizures (2), generalized spike or polyspike and wave discharges (12), generalized slowing (5), focal discharges (1), multifocal discharges (2), focal slowing (1), occipital intermittent rhythmic delta activity (OIRDA) and (5), excess beta frequency activity (1). Four patients have had persistently normal EEG results, with one patient having a normal EEG as of 19 years of age and another patient at 6 years of age.

3.4 |. Genotype–phenotype relationships

The phenotypes of patients with truncating, missense, intronic, and microdeletions were similar, with no significant differences observed between the types of variants and proportion of phenotypic features, except for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); (Figure 5). The phenotypes of patients with variants located across the three domains and SH3-binding motif were also not significantly different, except for those with variants in the SH3-binding motif having significantly lower frequency of epilepsy than the other three domains (p = .048; Table S1).

We conducted a secondary analysis, comparing phenotypic features between individuals with predicted loss-of-function variants in exons 1–4 vs exons 5–19. Eighty-three percent of individuals with variants in exons 1–4 were able to speak in phrases vs 31% of individuals with variants in exons 5–19 (p = .047; Table S2).

Age at epilepsy diagnosis was not significantly explained by variant type or variant location within the different SYNGAP1 domains, or for predicted loss-of-function variants in exons 1–4 vs exons 5–19 (p = .8, p = .5, p = .9, respectively, data not shown).

3.5 |. Imaging

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results were available for 141 patients. Ninety-four of the 141 patients (67%) had consistently normal MRI results, and 47 patients (33%) had at least one abnormal MRI result. The abnormal results were non-specific and included the following abnormalities: periventricular or subcortical white matter hyperintensities (n = 9), cerebral atrophy or gliosis (n = 8), unspecified focal hyperintensities (n = 5), arachnoid cyst (n = 4), cerebral ventriculomegaly (n = 4), Chiari I malformation (n = 4), hypomyelination/delayed myelination (n = 4), cerebral cyst (n = 3), simplified gyri or cortical dysplasia (n = 3) external hydrocephalus or prominent subarachnoid spaces (n = 2), mesial temporal sclerosis or asymmetry of hippocampus (n = 2), choroid plexus cyst (n = 2), pineal gland cyst (n = 2), corpus callosum abnormality (n = 2), intracranial hemorrhage (n = 2), macrocephaly (n = 1), microcephaly (n = 1), plagiocephaly (n = 1), subependymal nodular heterotopia (n = 1), hypoplasia of the cerebellar vermis (n = 1), and congenital vascular malformations (n = 1). Note that some individuals had multiple abnormalities.

3.6 |. Epilepsy treatment

Patients with SYNGAP1-related epilepsy initiated an average of 3.1 ASMs (range 0–13) and are currently taking on average 1.8 ASMs (range 0–5). Clobazam was most frequently continued after initiation (31% of patients currently taking), but other frequently used medications included lamotrigine (24%), valproate (23%), and levetiracetam (21%) (Table 1). Twenty-o ne patients (14%) initiated the ketogenic diet as a treatment for epilepsy and 12 patients (8%) patients were still adhering to the diet at the time of last data entry. Regarding surgical interventions and devices, five patients had a vagus nerve stimulator (VNS) implanted, three patients underwent corpus callosotomy, and one patient had a lobar resection/disconnection.

TABLE 1.

Anti-seizure medications initiated and currently prescribed to those with SYNGAP1-related disorder.

| Anti-seizure medication | Initiated in N (%) | Currently taking N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Levetiracetam | 71 (48) | 31 (21) |

| Clobazam | 58 (37) | 45 (31) |

| Valproate | 54 (37) | 35 (24) |

| Lamotrigine | 50 (34) | 35 (24) |

| Ethosuximide | 34 (23) | 15 (10) |

| Epidiolex/cannabidiol | 24 (16)/20 (14) | 22 (15)/11 (7) |

| Topiramate | 23 (16) | 6 (4) |

| Zonisamide | 17 (12) | 4 (3) |

| Clonazepam | 11 (7) | 6 (4) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 11 (7) | 2 (1) |

| Rufinamide | 8 (5) | 3 (2) |

| Perampanel | 7 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Carbamazepine | 5 (3) | – |

| Gabapentin | 5 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Felbamate | 4 (3) | 1 (.7) |

| Lacosamide | 4 (3) | 1 (.7) |

| Amantadine | 3 (2) | 1 (.7) |

| Brivaracetam | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Phenobarbital | 3 (2) | – |

| Vigabatrin | 1 (.7) | – |

| No Medications | 23 (16) | 24 (16) |

|

| ||

3.7 |. Medications for sleep, behavior, and ADHD

Sleep was the second-most common indication for medication in this cohort, with 62 patients (42%) taking medications for sleep. These medications included melatonin (n = 57, 39%), clonidine (n = 31, 21%), and trazodone (n = 10, 7%). Medications were prescribed for the indication of behavioral problems for 35 patients, and these included risperidone (n = 18), aripiprazole (n = 7), olanzapine (n = 3), clonidine (n = 10), guanfacine (n = 15), clonazepam or lorazepam (n = 6), and gabapentin (n = 5). Medications taken for an indication of ADHD included stimulants (methylphenidate or amphetamine formulations) (n = 10), atomoxetine (n = 1), and guanfacine or clonidine (n = 10). Medications taken for an indication of anxiety included citalopram (n = 4), clonidine (n = 4), escitalopram (n = 2), fluoxetine (n = 4), paroxetine (n = 1), and sertraline (n = 4).

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this retrospective longitudinal study, we delineate the phenotype of SYNGAP1-related disorder in a large cohort, assembled through a digital patient-centered platform. All patients had either GDD or ID, and in the majority of patients, the GDD was the presenting diagnosis at a median age of 17 months. Epilepsy occurred in 84% of patients at a median age of 34 months. In our study, 14% of patients had an initially normal EEG report. Ataxia or abnormal gait was diagnosed at a median age of 35 months, ASD at 36 months, and behavioral problems at 45 months for those diagnosed with these conditions. The majority of MRI reports were normal and in those with abnormalities, they were non-specific. The indication for genetic testing was not available, including for those with structural MRI abnormalities.

These findings of GDD diagnosis preceding epilepsy highlight a potential therapeutic opportunity to identify P/LP SYNGAP1 variants in patients with GDD before seizure onset and possibly develop therapies to prevent seizures. Alternatively, as previous studies have noted, the seizures in SYNGAP1-telated disorder can be subtle and misinterpreted as behaviors, so it is possible that seizure onset may occur earlier than our study reflects. In the future, it will be beneficial to identify children with SYNGAP1-t elated disorder based on global delays and monitor for seizure onset with EEG. This would require a change in current genetic testing practices to include GDD alone as an indication for genetic testing with exome sequencing or multi-gene panels. A Consensus Statement in 2019, based on expert review and analysis of yield of different genetic tests in GDD/ID and ASD, supports exome sequencing as a first-line genetic test for GDD.15 Our data regarding the disease course of SYNGAP1-related disorder, with seizures generally following recognition of GDD, support the idea that sequencing for GDD may identify genetic causes and thus allow improved surveillance for seizures and possibly earlier intervention to treat seizures. Although an intervention to prevent epilepsy has not yet been identified for SYNGAP1-related disorder, the prevention of epilepsy with vigabatrin for individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex has provided a compelling example of the possibility of developing therapies to prevent epilepsy when the genetic disorder is identified early before epilepsy onset.16

In our clinical experience, behavioral problems are often a particular concern for parents, particularly as children grow, transition through schools, and approach adulthood. We found that behavioral problems were diagnosed in 100 patients (68%), autistic traits or autism spectrum disorder in 100 of 147 patients (68%), and sleep problems were diagnosed in 90 (61%). Through the availablility of restrospective review of medical records data, we also showed the ages at onset of epilepsy, behavioral problems, autistic traits, and ataxia in individuals with SYNGAP1-related disorder, and we accounted for the absence of data available if an individual had no data available beyond a certain age (Figure 3).

We also assessed the interplay between the presence of behavioral problems and other symptoms of SYNGAP1-related disorder, and we found that behavioral problems were more likely to occur in patients with sleep problems and anxiety. These findings support the importance of recognizing and managing sleep problems and anxiety to assist with management of other symptoms such as behavioral problems. Future prospective work is needed to provide a detailed analysis of the neurobehavioral and neurodevelopmental profile of individuals with SYNGAP1-related disorder, which will improve our understanding of these potential relationships and aid in identifying ways to improve management of these symptoms.

Medications were utilized in the treatment plans for behavioral problems in 35 patients and for sleep in 62 patients. Our finding of 69% of those with sleep problems utilizing a medication for sleep was higher than the 31% in the study by Smith-Hicks et al.17 Our data did not include information on non-p harmacological treatments, such as applied behavioral analysis (ABA). Further studies are needed to analyze the efficacy of these medications and other interventions for behavior, sleep, and anxiety.

Although the retrospective data do not allow for an evaluation of the efficacy of ASMs in SYNGAP1-related disorder, clobazam was the most commonly continued medication, and valproate, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam were commonly used as well, which is not unsurprising given the generalized epilepsy phenotypes in the majority of patients with SYNGAP1-related disorder. It should be noted that over half of the patients who started levetiracetam were no longer taking it at the end of the data collection, suggesting that although it was the most initiated ASM, it may not be as efficacious or tolerable as other medications for the SYNGAP1-related disorder population.

There were some differences between our study and earlier descriptions of SYNGAP1-related disorder. In contrast to the Vlaskamp study, in which 98% of patients were diagnosed with epilepsy, in this study, 84% of patients were diagnosed with epilepsy. This apparent difference was likely due to differences in ascertainment and recruitment strategies. Specifically, we did not restrict our recruitment based on epilepsy diagnosis. Earlier studies have also suggested a milder phenotype in patients with variants in exons 1–4 vs exons 5–19, in relation to ID and response to medications.5,18 We also observed a significant difference in the language development of patients with variants located in exons 1–4 vs 5–19. This may be explained by the presence of multiple isoforms of the SynGAP1 protein, with 1 human isoform not including exons 1–4.18 Alternatively, differences in nonsense mediated decay may play a role.18 In addition, we observed a tendency for fewer epilepsy diagnoses among individuals with variants in the SH3 functional motif. Future prospectively designed studies will allow more definitive assessment of the relationships between genotypes and neurodevelopmental and epilepsy-related phenotypes.

Although the methods of data collection were different, our study yielded results that were similar to those reported in recent years by Vlaskamp et al.,5 which utilized more traditional methods of manual review of medical records and parent interviews for data collection. We highlight the feasibility of attaining longitudinal phenotypic data from a digital registry, rather than the more traditional interview and medical record review methodologies. Data collection was expedited with the digital registry methodology, and we performed variant classification to determine inclusion in our analysis for each patient included in the data set. Given that this methodology utilizes the medical record to extract data, there are important limitations to consider—namely, details not available in the medical record cannot be collected with this methodology. For instance, our assessment of seizure types and frequency was limited by the available descriptions of seizures in the record and the lack of detail on seizure variability over time.

Although this method does not replace a prospective natural history study conducted utilizing interviews and longitudinal record collection, our study supports the use of a digital registry compiled through retrospective data extraction of the medical record as an efficient adjunct method to perform genotype–phenotype analyses in rare disease. Through our use of the Ciitizen SYNGAP1 digital registry, we have recapitulated with a larger data set the results from previous studies of SYNGAP1-related DEE with smaller cohorts, and we have identified additional relationships between symptoms of SYNGAP1-related disorder.

We propose that endpoints for future clinical trials of treatments for SYNGAP1-related disorder should include measures of epilepsy, ID, behavior, sleep problems, and anxiety.

Supplementary Material

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

Key points.

Using a novel approach to data collection from data extracted from medical records by a third party (Ciitizen) and independently validating classification of genetic variants as pathogenic, we identified the following core features of SYNGAP1-related disorder: global developmental delay/intellectual disability (GDD/ID) and generalized epilepsy in most patients.

We highlighted the time course of the symptom development of SYNGAP1-related disorder, with GDD/ID generally diagnosed before seizure onset.

Additional features of SYNGAP1-related disorder included autistic traits, behavioral problems that correlated with anxiety and sleep problems, as well as ataxia or abnormal gait and feeding problems.

Variants in the SH3 domain tended to correlate with a lower likelihood of epilepsy diagnosis, whereas variants in exons 1–4 had lower severity of language delay.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many families who enrolled in the Ciitizen database to make their family members’ data available for research and the leadership at The SynGAP Research Fund for facilitating our access to the database. This study was supported by a grant from The SynGAP Research Fund.

Funding information

SYNGAP Research Fund

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Elise Brimble is employed by Invitae. Kimberly Wiltrout is a consultant for Stoke Therapeutics. Annapurna Poduri serves, without compensation, on the scientific advisory board for The SynGAP Research Fund. We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data that support the analyses presented here contain sensitive and protected health information for participants and are, therefore, not openly available. Requests for data access can be made to cii-research@invitae.com, where we can confirm that the proposed research scope is consistent with platform consent language and is reviewed and/or approved by an institutional review board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal M, Johnston MV, Stafstrom CE. SYNGAP1 mutations: clinical, genetic, and pathophysiological features. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2019;78:65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JH, Liao D, Lau LF, Huganir RL. SynGAP: a synaptic RasGAP that associates with the PSD-95/SAP90 protein family. Neuron. 1998;20:683–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen HJ, Rojas-Soto M, Oguni A, Kennedy MB. A synaptic Ras-GTPase activating protein (p135 SynGAP) inhibited by CaM kinase II. Neuron. 1998;20:895–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamache TR, Araki Y, Huganir RL. Twenty years of SynGAP research: from synapses to cognition. J Neurosci. 2020;40:1596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vlaskamp DRM, Shaw BJ, Burgess R, Mei D, Montomoli M, Xie H, et al. Encephalopathy: a distinctive generalized developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. Neurology. 2019;92:e96–e107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, Noreau A, Yang Y, Pellerin S, et al. Mutations in SYNGAP1 in autosomal non-syndromic mental retardation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinto D, Pagnamenta AT, Klei L, Anney R, Merico D, Regan R, et al. Functional impact of global rare copy number variation in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2010;466:368–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvill GL, Heavin SB, Yendle SC, McMahon JM, O’Roak BJ, Cook J, et al. Targeted resequencing in epileptic encephalopathies identifies de novo mutations in CHD2 and SYNGAP1. Nat Genet. 2013;45:825–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berryer MH, Hamdan FF, Klitten LL, Møller RS, Carmant L, Schwartzentruber J, et al. Mutations in SYNGAP1 cause intellectual disability, autism, and a specific form of epilepsy by inducing haploinsufficiency. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:385–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Writzl K, Knegt AC. 6p21.3 microdeletion involving the SYNGAP1 gene in a patient with intellectual disability, seizures, and severe speech impairment. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:1682–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von Stülpnagel C, Hartlieb T, Borggräfe I, Coppola A, Gennaro E, Eschermann K, et al. Chewing induced reflex seizures (“eating epilepsy”) and eye closure sensitivity as a common feature in pediatric patients with SYNGAP1 mutations: review of literature and report of 8 cases. Seizure. 2019;65:131–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, Riney K, Samia P, et al. International league against epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset in childhood: position paper by the ILAE task force on nosology and definitions. Epilepsia. 2022;63:1398–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srivastava S, Love-Nichols JA, Dies KA, Ledbetter DH, Martin CL, Chung WK, et al. Meta-a nalysis and multidisciplinary consensus statement: exome sequencing is a first-t ier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med. 2019;21:2413–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotulska K, Kwiatkowski DJ, Curatolo P, Weschke B, Riney K, Jansen F, et al. Prevention of epilepsy in infants with tuberous sclerosis complex in theEPISTOPTrial. Ann Neurol. 2021;89:304–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith-Hicks C, Wright D, Kenny A, Stowe RC, McCormack M, Stanfield AC, et al. Sleep abnormalities in the Synaptopathies—SYNGAP1-related intellectual disability and Phelan–McDermid syndrome. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mignot C, von Stülpnagel C, Nava C, Ville D, Sanlaville D, Lesca G, et al. Genetic and neurodevelopmental spectrum of SYNGAP1-associated intellectual disability and epilepsy. J Med Genet. 2016;53:511–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data that support the analyses presented here contain sensitive and protected health information for participants and are, therefore, not openly available. Requests for data access can be made to cii-research@invitae.com, where we can confirm that the proposed research scope is consistent with platform consent language and is reviewed and/or approved by an institutional review board.