Abstract

Introduction:

Enteral resuscitation (EResus) is operationally advantageous to intravenous resuscitation for burn-injured patients in some low-resource settings. However, there is minimal guidance and no training materials for EResus tailored to non-burn care providers. We aimed to develop and consumer-test a training flipbook with doctors and nurses in Nepal to aid broader dissemination of this life-saving technique.

Materials and Methods:

We used individual cognitive interviews with Nepali (n=12) and international (n=4) burn care experts to define key elements of EResus and specific concepts for its operationalization at primary health centers and first-level hospitals in Nepal. Content, prototype illustrations, and wireframe layouts were developed and revised with the burn care experts. Subsequently, eight consumer testing focus groups with Nepali stakeholders (5–10 people each) were facilitated. Prompts were generated using the Questionnaire Appraisal System (QAS) framework. The flipbook was iteratively revised and tested based on consumer feedback organized according to the domains of clarity, assumptions, knowledge/memory, and sensitivity/bias.

Results and Discussion:

The flipbook elements were iterated until consumers made no additional requests for changes. Examples of consumer inputs included: clarity—minimize medical jargon, add shrunken organs and wilted plants to represent burn shock; assumptions—use locally representative figures, depict oral rehydration salts sachet instead of a graduated bottle; knowledge/memory—clarify complex topics, use Rule-of-9s and depict approximately 20% total body surface area to indicate the threshold for resuscitation; sensitivity/bias—reduce anatomic illustration details (e.g. urinary catheter placement, body contours).

Conclusion:

Stakeholder engagement, consumer testing, and iterative revision can generate knowledge translation products that reflect contextually appropriate education materials for inexperienced burn providers. The EResus Training Flipbook can be used in Nepal and adapted to other contexts to facilitate the implementation of EResus globally.

Keywords: Enteral resuscitation, Burn, Implementation, Infographic, Medical Education, Low- and middle-income countries

Introduction

Early resuscitation for major burn injuries is vital to prevent hypovolemic shock, which can lead to organ dysfunction and death if not remedied [1], [2]. Timely and effective resuscitation requires optimal resources, technical education, and experience caring for burn-injured patients [3], [4]. However, these elements are not available in much of the world, proximate to locations of injury [2]. As a result, patients with major burn injuries in many areas of low- and middle-income countries experience delays in resuscitation and unsatisfactory outcomes [5]–[7]. These delays in resuscitation contribute to three to four times higher rates of mortality in low-resourced settings due to acute kidney injury, shock, and multiple organ dysfunction [8], [9]. Therefore, a standardized resuscitation protocol and accompanying training materials are required to deliver resuscitation faster to patients in need [10].

Resuscitation can be administered either intravenously (IV) or enterally. Enteral resuscitation (EResus) is the delivery of fluids via drinking or nasogastric tube. This method of resuscitation is advocated by the World Health Organization (WHO) and other national and international burn professional societies given its efficacy and operational advantages in low-resource settings [11]–[13]. EResus does not require IV placement in field locations and, therefore, can be started immediately following the injury [6], [14], [15]. Additionally, equipment and personnel to administer and monitor large-volume IV resuscitation may be lacking, such as IV catheters and lines, sterile fluids, and trained healthcare personnel [7], [16]. Despite EResus’s advantages, there is currently minimal guidance and no training materials for this resuscitation technique tailored to stakeholders in low-resource settings with limited burn care experience.

Adapted EResus guidelines for low-income countries have been previously developed based on standardized resuscitation protocols for critically ill patients [11], [17]. Based on the content and organization of these protocols, we aimed to develop a more accessible model for training dissemination to doctors and nurses in Nepal, a country with one of the highest rates of burn injury globally and a growing burn care system [18]. Effective communication of resuscitation protocols in this model necessitates ease of distribution and comprehension of the information across education and experience differences within the healthcare system. Infographics are widely known to effectively and concisely convey complex, technical medical information to varying educational-level audiences [19]–[23]. They can be especially useful for summarizing detailed step-wise processes, such as the content of EResus protocols. Incorporation of infographics into a WHO-style training flipbook would allow for ease of readability while conveying vital information to a variety of health providers.

Methods

Development of an initial prototype of the infographic flipbook was created based on individual cognitive interviews with Nepali (n=12) and international (n=4) burn care experts to define key elements of EResus and specific concepts for its operationalization at primary health centers and first-level hospitals in Nepal. Preferences surrounding the flipbook’s content, formatting, style, and overall design were then assessed through consumer focus groups with stakeholders in Nepal until no additional revisions were requested and comprehension was optimized.

Study Setting and Population

The study was based at the Nepal Cleft and Burn Center (NCBC) at the phect-NEPAL Kirtipur Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. The NCBC is a teaching hospital and is the only burn center in Nepal with critical care capacity. NCBC admits over 600–700 acute burn-injured patients annually, accounting for over 75% of burn patients’ referrals in Nepal [18]. We recruited Nepali Bachelor of Medicine Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) students, nurses, and doctors at the NCBC and two peripheral hospitals in Pokhara, Nepal for the Nepali stakeholder focus groups. Inclusion criteria for those interviewed were age over 18 years and the ability to read, write, and speak in English. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Washington in Seattle, WA, USA, the Nepal Health Research Council, and the Ethical Review Board of Public Health Concern Trust (phect-Nepal) in Kathmandu, Nepal. Informed and written consent was obtained from all participants ahead of the interviews.

Infographic Flipbook Prototype Development

The initial prototype development process was facilitated by several video conferences for individual cognitive interviews with burn care experts (n=3) at the University of Washington in Seattle, WA, USA, and NCBC in Kathmandu, Nepal (n=12), and one medical illustrator/Narrative Medicine expert from Brown University Alpert Medical School in Providence, RI (Figure 1). The protocol and content were based on our team’s ongoing pragmatic implementation-effectiveness randomized trial of EResus versus enhanced standard of care IV resuscitation (n=30) at this same NCBC site in Nepal and a separate cluster-randomized trial of EResus versus IV resuscitation at hospitals in Ghana [24]. All experts assisted in communicating the protocol in plain language in English and designing the wireframe layout, then worked with the medical illustrator to create images to support the pertinent training material in ways that were relevant to would-be viewers of the flipbook.

Figure 1.

Study participants and setting.

The flipbook was originally designed as pocket-sized when-folded (8 × 5.5 inches) in landscape orientation with twenty-nine pages of content. Evidence-based practices for infographic design in the flipbook were employed, such as showing direct comparisons, providing clinical context, progressively modifying pictorial icons to demonstrate transitions, using symbols and images that would deliver accurate meaning even when interpreted literally, avoiding text-based infographics, and aiming for simplicity in the illustrations [19], [25], [26]. These methods were used to improve communication of key concepts outlined by the burn care experts to healthcare workers with varying levels of EResus literacy between different hospital settings. The graphics were created digitally using 2D editing software. The images were illustrated first using raster-based digital software (ProCreate®, v.5.3.5), then formatted using photo/image editing software (Adobe Illustrator®, v.27.5, and Microsoft PowerPoint®, v.16.73).

Infographic Flipbook Evaluation and Revision

After initial review and incorporating feedback from the individual interviews with the burn care experts, we assembled eight consumer testing focus groups of Nepali stakeholders (n=72) following the National Institute of Health/Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (NIH/PROMIS) Guidelines. Prompts in an infographic/flipbook assessment interview guide for the consumers were generated using the Questionnaire Appraisal System (QAS) [27]. The QAS is a tool for pretesting instruments and can account for cross-cultural and cross-linguistic differences in content validation. The QAS includes four domains that are employed for prompt generation: clarity, assumptions, knowledge and memory, and sensitivity and bias (Table 1). Each of the domains has multiple underlying themes. Clarity involves the wording, technical terms, and lack of vagueness in the text or images. Assumptions can consist of inappropriate predictions and constant or double-barreled behavior. Knowledge and memory ensure that the knowledge does exist in the cohort and attitude, recall, and computational abilities based on the information shared. Finally, sensitivity and bias require that there is no sensitive content and that the content is socially acceptable.

Table 1.

Shows the QAS four domains for focus group prompt generation: clarity, assumptions, knowledge and memory, and sensitivity and bias, in addition to their corresponding themes and sample questions based on each domain and theme.

| Clarity | Identify problems related to communicating the intent or meaning of the concepts and images in each section to the learner | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wording | Is the text lengthy, awkward, ungrammatical, too colloquial, or contains complicated syntax? | Is the explanation of indications and benefits of nasogastric tube use concise and effective? | ||

| Technical terms and concepts | Are the terms undefined, unclear, or complex? | Is resuscitation and its importance undefined, unclear, or too complex? | ||

| Vagueness | Are there multiple interpretations or understandings of the text, concepts, and/or images? | Do the images and text appropriately describe and convey the concept of resuscitation? | ||

| Time periods | Are time references missing, not well specified, or problematic? | Are the order of resuscitation steps and the time frame for following up with the patients clear? | ||

| Assumptions | Determine whether there are problems with the assumptions made/required or logic of the concepts and images | |||

| Inappropriate assumptions | Are there beliefs or concepts in text or images that are inaccurate in relation to the respondent or their situation? | Does the image of consuming ORS match the experience of ORS consumption in Nepal? | ||

| Assumes constant behavior | Do concepts or processes fail to account for situations when behaviors or experiences vary? | Does the image of the need for EResus explain the experiences of why it must be utilized in Nepal correctly? | ||

| Double-barreled | Do images, pages, or sections contain more than one implicit concept? | Is the illustration of how to place a Foley catheter helpful or redundant for the nurses’ knowledge-base? | ||

| Knowledge and memory | Check whether the learners are likely to not know or have trouble remembering the concepts and images | |||

| Knowledge | Are learners unlikely to know the details of the concepts? | Are nurses in peripheral hospitals familiar with the Parkland Formula? | ||

| Attitude or belief | Are learners likely to have formed a different attitude regarding the concepts? | Are the indications for when to utilize enteral resuscitation addressed? | ||

| Recall | Do learners remember the concepts after review? | Are the steps on how much resuscitation fluid clear enough to be remembered? | ||

| Computation | Do depicted processes require difficult mental computations? | Is portraying and suggesting the Rule of 9s acceptable for peripheral providers to estimate burn injury size to assess need for resuscitation? | ||

| Sensitivity and bias | Assess concepts and images for sensitive nature, wording and/or bias | |||

| Sensitive content | Are there phrases, images, or concepts that depict a topic or issue that is embarrassing or very private? | Is it too sensitive to show the depicted patient with large burns? | ||

| Sensitive wording | Given sensitive text, images, or concepts, should they be improved to minimize sensitivity? | Is the portrayal of active vomitting too graphic, or does it appropriately convey the concept for reader comprehension? | ||

| Socially acceptable | Are concepts implied by the text and images socially acceptable? | Is it culturally acceptable and appropriate to depict placement of a urinary catheter in a female patient? | ||

Based on these domains, we developed prompts corresponding to each flipbook page to ask the Nepali stakeholder focus group members. For example, based on the vagueness theme within the clarity domain, we asked participants, “Do the images appropriately portray resuscitation?” Based on the assumptions domain to get to the theme of inappropriate assumptions, we asked, “Does the image of consuming ORS match your experience with ORS consumption?” Based on the sensitivity and bias domain and the sensitive content theme, we asked, “Is it culturally acceptable to depict placing a urinary catheter in a female patient?” (see Table 1 for the complete list of QAS focus group questions).

We conducted the Nepali stakeholder focus groups in person in 8 groups of 5–10 people each. We gave each participant a printed flipbook copy in English to ask questions, seek clarifications, and write their feedback on. We also projected the flipbook digital version to go through each page at the same time together to seek group feedback using our interview prompts. The same QAS questions were asked in both English and Nepali to ensure comprehension and empower preferred-Nepali speakers to give input. The focus groups were approximately 1–2 hours long and hosted at NCBC in Kathmandu and two peripheral hospitals in Pokhara. The central focus groups in Pokhara included nurses and doctors from multiple health posts and hospitals in the province. We followed the same script for each focus group and asked participants for more detailed insights based on their unique feedback. Focus groups were no longer organized once no new feedback was provided. The focus groups were audio-recorded.

Data Analysis

We used a deductive approach to code the focus group data manually. Codes were discussed, and a senior investigator resolved any disagreements. The expert group manually listened to the focus group transcripts and reviewed all printed flipbook copies with notes from participants to identify answer themes—or areas of the flipbook needing improvement—within the QAS domains. We defined an answer theme as an answer to a QAS prompt mentioned or agreed upon by at least two people per focus group. The experts cross-checked each other’s chosen themes for confirmation. The focus group participants were not reimbursed financially for their time but were provided with refreshments. The flipbook content and infographics were then revised by the burn care experts and medical illustrator based on the feedback and themes from the focus groups. The final version was the one circulated amongst participants who provided no additional requests for revision.

Results

Infographic Flipbook Prototype Development: Prototype Outline

Key concepts defined by the burn care experts that needed to be conveyed in the flipbook for appropriate EResus training included care providers’ ability to understand why EResus is critical to patient recovery, administer the proper amount of EResus depending on burn size and age, monitor patients to adjust EResus for their optimal care, and adapting/troubleshooting difficult resuscitations. Based on the integration of these concepts, the flipbook is organized into five subsections:

Introduction to major burns, shock, and resuscitation

Resuscitation tools and methods

Resuscitation end-goals and monitoring

Common challenges and tips with resuscitation

Concluding resuscitation and next steps

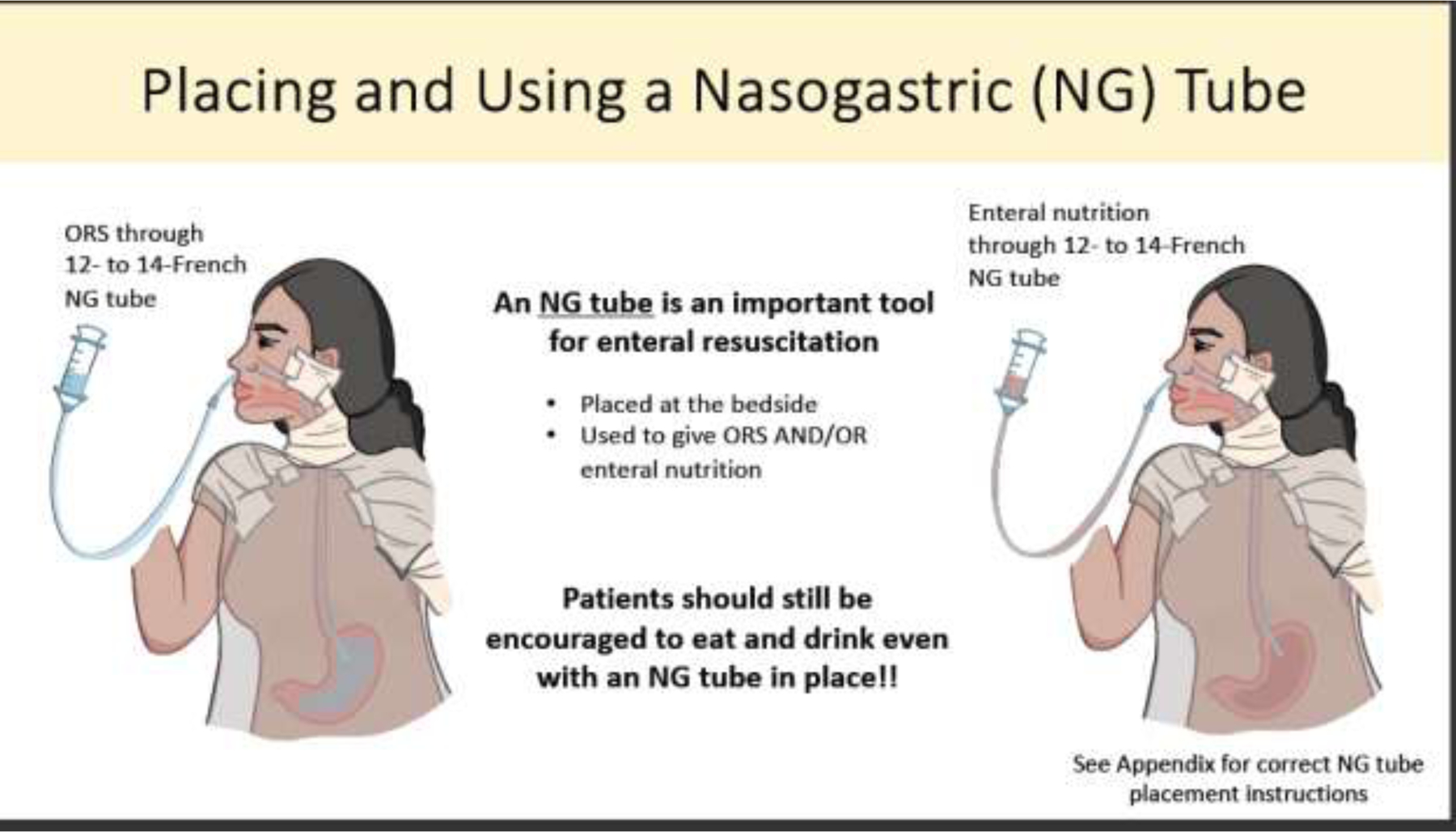

Infographics within the flipbook illustrate how to estimate burn size based on age, how to make and administer EResus, how to place and use a nasogastric tube, how to place and monitor urine output with a urinary catheter, how to determine the amount of fluid administered to patients, how to prevent and manage potential adverse events during resuscitation, and other issues (see Supplementary Material).

Infographic Flipbook Evaluation and Revision: Focus Group Feedback and Iterative Revision

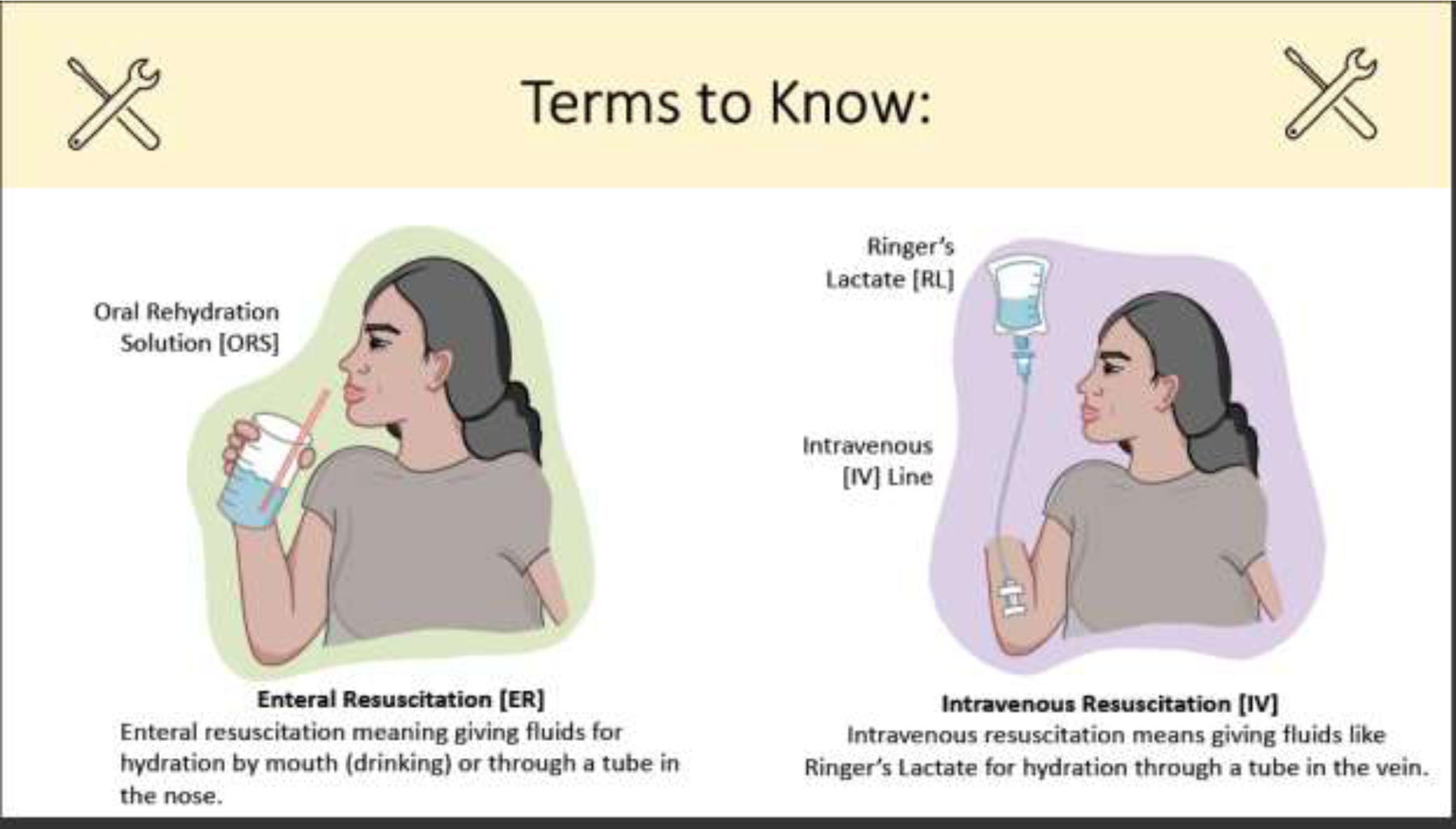

After receiving feedback from the Nepali stakeholder focus groups, we organized answers to the QAS domain questions based on the original text, concepts, and images compared to the consumer-recommended revisions (Table 2). Based on the feedback from these focus groups, we developed a revised EResus Training Flipbook with updated infographics and content layout. Some notable revision examples include depicting dehydration both in humans and symbolically to convey the concept of resuscitation with multiple visual representations that improved clarity. For example, this resulted in the creation of shrunken, shriveled organs on the person and a wilted plant to represent shock and the need for resuscitation (Figures 2A and 2B). To improve the clarity, conciseness, and effectiveness of how we portrayed nasogastric tube benefits, participants said they would like to see the text reduced to key phrases. They also noted that they would like to see the pertinence of early facilitation and overnight use of the nasogastric tube to improve EResus efforts more clearly highlighted. Therefore, we separated the flipbook pages into the importance and placement of a nasogastric tube along with the ability to use the nasogastric tube at night for more feeding (Figures 3A, 3B, and 3C). Under the assumptions domain, we asked if the image showing a cup and water with a straw depicted throughout the flipbook matches the experience of ORS consumption in Nepal. Participants emphasized that in Nepal, ORS sachets (“Jeevan Jal” in Nepali) and mineral water bottles are used as the EResus fluid instead. (Figures 4A and 4B). Under knowledge and memory, participants were asked if “portraying and suggesting the Rule of 9s is appropriate for peripheral providers to estimate burn size and assess the need for resuscitation.” Feedback included that the Rule of 9s is a helpful tool to calculate burn size, but they would also need to see a person with roughly ≥15% TBSA burn to conceptually indicate that this is the threshold burn size that would necessitate resuscitation. Also, nurses were more familiar with using the Rule of Palms, so they wanted to see this in addition to the Rule of 9s (Figures 5A, 5B, and 5C). Finally, when assessing sensitivity and bias, we asked if it is culturally acceptable and appropriate to depict the placement of a urinary catheter in a female patient. Participants responded, “As long as the image demonstrates the anatomical placement concept, it is acceptable for our medical audience.” In this case, we did not change our original depiction of urinary catheter placement (Figure 6).

Table 2.

Shows the consumer-recommended revisions from the focus groups based on specific criteria for pages of the EResus Training Flipbook.

| Clarity | Identify problems related to communicating the intent or meaning of the concepts and images in each section to the learner | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wording | Is the text lengthy, awkward, ungrammatical, too colloquial, or contains complicated syntax? | List of indications and benefits of NG tube use to facilitate enteral resuscitation and feeding | Reduced text to key phrases and focus on ‘early’ and ‘facilitation’ of enteral resuscitation | |

| Technical terms and concepts | Are the terms undefined, unclear, or complex? | Urimeter; enteral resusication; low urine output | Urobag; ORS resuscitation; dark and light urine | |

| Vagueness | Are there multiple interpretations or understandings of the text, concepts, and/or images? | Depiction of dehydrated person to represent shock | Addition of dehydration represented by both person and symbology (shrunken organs, wilted plant) | |

| Time periods | Are time references missing, not well specified, or problematic? | Description of processes and resuscitation protocol | Use of single-patient narrative to establish chronologic order | |

| Assumptions | Determine whether there are problems with the assumptions made/required or logic of the concepts and images | |||

| Inappropriate assumptions | Are there beliefs or concepts in text or images that are inaccurate in relation to the respondent or their situation? | Use of graduated cylinder and straw to depict drinking ORS | Depiction of ORS sachets (i.e, ‘Jeevan Jal’ in Nepali) and mineral water | |

| Assumes constant behavior | Do concepts or processes fail to account for situations when behaviors or experiences vary? | Simple reference to NG tube insertion | Depiction of steps of NG tube insertion and tips for safe position confirmation | |

| Double-barrelled | Do images, pages, or sections contain more than one implicit concept? | Use of shriveled organs to depict burn shock | Use of both burned skin and shriveled organs to depict burn shock | |

| Knowledge and memory | Check whether the learners are likely to not know or have trouble remembering the concepts and images | |||

| Knowledge | Are learners unlikely to know the details of the concepts? | Generally depict NG placement or NG tube already in place | Describe key NG length estimation landmarks (i.e., nose, ear, xyphoid) | |

| Attitude or belief | Are learners likely to have formed a different attitude regarding the concepts? | Goal ≥30 mL of urine output per hour for adult | Goal 0.5 mL of urine output per hour for adult | |

| Recall | Do learners remember the concepts after flipbook review? | List of indications and benefits of NG tube use not recalled | Addition of ‘life-water, lifeline’ phrase (i.e., ORS is termed Jeevan Jal and means life-water in Nepali) and infographic of resusciation volume depicted by numbers of mineral water bottles | |

| Computation | Do depicted processes require difficult mental computations? | Use of Rule of 9s to estimate size before assessing need for resuscitation | Depicting person with ≥20% body surface area burn requires resuscitation (i.e., smaller vs large burn) | |

| Sensitivity and bias | Assess concepts and images for sensitive nature, wording and/or bias | |||

| Sensitive content | Are there phrases, images, or concepts that depict a topic or issue that is embarrasing or very private? | Depiction of urinary catheter entering bladder in woman patient | Revised illustration to demonstrate concept not anatomical placement | |

| Sensitive wording | Given sensitive text, images, or concepts, should they be improved to minimize sensitivity? | Example woman patient with more visible anatomical body contours | Depicted woman with simplified body contours | |

| Socially acceptable | Are concepts implied by the text and images socially acceptable? | Example woman patient with short hair and specific facial structure (i.e., full lips, mandible projection) | Depicted woman with long hair and less pronounced facial features (i.e., thinner lips, less defined mandible) | |

Figure 2.

A. Shows the design of the flipbook page conveying the concept of resuscitation before focus group feedback.

B. Shows the design of the same page after focus group feedback was incorporated based on the question, “Do the images and text appropriately describe and convey the concept of resuscitation?”

Figure 3.

A. Shows the flipbook design conveying the importance of using a nasogastric tube and its placement in a patient.

B. Shows the revised first page of how to place and use a nasogastric tube based on consumer feedback to separate the important concepts of nasogastric tube placement, use, and importance.

C. Shows the revised second page of the importance of implementing a nasogastric tube for oral feeding after consumers noted that this should be its own page to enhance engagement.

Figure 4.

A. The initial flipbook page showing the difference between enteral and IV resuscitation.

B. The revised flipbook page still articulating the difference between enteral and IV resuscitation but tailored with a Jeevan Jal ORS packet and a water bottle instead of water in a cup with a straw to more appropriately convey the concepts used in Nepal.

Figure 5.

A. Shows the initial Rule of 9s illustrations to highlight how to calculate burn TBSA%.

B. After consumer focus groups, the calculation of burn TBSA% was split into this first page on the Rule of 9s and 1% hand rule with more apparent differences between the sizes of body parts depending on the patient’s age.

C. The second page showing an example of how to calculate burn TBSA% in an adult and child and the size of burn that would indicate the need for EResus. Focus group participants noted that the importance of teaching these concepts warranted their separation into two pages.

Figure 6.

The unchanged page on how to correctly place a Foley catheter based on consumer feedback that this concept is culturally appropriate to show and well-understood by nurses in peripheral sites of Nepal.

Participants also shared overarching feedback for the layout of the flipbook. For example, many noted that it would be more helpful to place the “Steps to Starting EResus” toward the beginning of the pages to give a preface to the purpose of the flipbook. Additionally, they noted that concepts such as urinary catheter and nasogastric tube placement are more widely known among Nepali nurses. Because of this, we placed these concepts at the end of the flipbook as an Appendix. Conversely, ways to convince patients of the importance of these instruments are lesser known. Therefore, we incorporated changes into the flipbook that emphasize these tools’ importance and ways to involve family members or other methods of implementation that can ensure providers can place these devices for patient feeding and urine output monitoring. We also learned that one of the concepts least understood is the need to resuscitate patients on the way to a burn center from the field, so we developed a new infographic on the importance of providing EResus even during transport from peripheral settings (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The added flipbook page after consumer feedback that it is crucial to involve families to encourage patients to use a nasogastric tube, so teaching this to healthcare providers is equally as important.

The number of recommendations and feedback from Nepali stakeholders suggest that consumer testing of this educational tool improved its effectiveness in this setting. The first flipbook model contained more text and fewer Nepal-specific cultural references, such as the Jeevan Jal ORS sachet, symbols for dehydration, accurate depictions of clothes or hair typically worn in Nepal, and referral information. Due to the inclusion of nurses, medical students, and doctors, we could interview a diverse population of individuals who would employ resuscitation to patients. The final flipbook drew attention to the feedback from these stakeholders to improve communication of the EResus protocol and ensure that it is an accurate training tool for healthcare providers in peripheral Nepal settings. Focus group participants also noted that they “enjoyed the illustrations more than the text” on each flipbook page, leading to revisions with less wording and more symbolic representation of concepts. We believe this implementation will allow the flipbook to be better understood by populations with different literacy levels. However, further studies are necessary to prove this concept in focus groups with documentation of differently educated participants.

The flipbook our team created employed infographics as a teaching tool, which are well-known to enhance engagement, memory retention, recall, comprehension, and development of communication skills for medical education [28]. As the team of burn care experts and medical illustrator are not the target audience of the EResus Training Flipbook, it was necessary to consumer-test the validity, usability, and reliability of the infographic designs and flipbook layout [28], [29]. To focus feedback from stakeholders, the QAS was employed to generate questions that could give concrete answers on clarity, assumptions, knowledge and memory, and sensitivity and bias [27]. Feedback from Nepali nurses, medical students, and doctors guided the revisions of the flipbook, which now has more cultural-specific, comprehensible content to teach the protocol for EResus.

Logistical Lessons Learned

In addition to the educational advantages that our study promotes in teaching EResus, we also discovered beneficial focus group practices that facilitated productive, generative group discussions with stakeholders. First, we employed our flipbook to the recommended focus group size of 6–8 participants [30], [31]. We found that these smaller groups promoted more robust discussions and a greater opportunity for each participant to share their opinions. We also found it constructive for each group to include multiple facilitators with one discussion leader and one note-taker, with additional data collection via the audio recording of each focus group to ensure we noted all the feedback and could highlight common themes on the spot. In addition to the multiple facilitators, we also used various modalities—both computer projection and individual printed copies—to display and interact with the EResus Training Flipbook. The computer projection allowed us to facilitate a cohesive group discussion, and the printed copies allowed participants to take notes as they thought of their suggestions. Finally, combining specific and broad questions within the QAS domains allowed us to receive nuanced feedback between options the expert burn care group had discussed. It allowed focus group participants to generate their own ideas for improvement of the flipbook. These practices allowed us to develop stakeholder feedback that better tailors our model to this specific hospital setting.

Discussion

We aimed to develop a contextually appropriate and consumer-tested WHO-style infographic-based EResus Training Flipbook for providers caring for those with major burn injuries in Nepal. By assessing the Nepali stakeholders’ responses to the initial flipbook prototype and incorporating their feedback into revisions, optimal understanding is possible in the final product. This product can serve as a tool for better educating on how to resuscitate burn-injured patients, preventing otherwise common unsatisfactory outcomes like organ dysfunction and death.

Burns in low-resource settings comprise greater than 95% of the 11 million burns that occur annually, with 70% of these occurring among children [32]. Additionally, less than 5% of patients with burn injuries larger than 40% TBSA in low-resource countries survive [18]. Clearly, implementing appropriate burn care is essential to decrease morbidity and mortality in these patient populations. Immediate resuscitation is required for adult patients with major burns greater than 15% TBSA and in children with burns or patients with electrical burns greater than 10% TBSA [7]. Importantly, patients in low-resource countries are typically treated outside burn centers first, not at large facilities with appropriate resources and trained burn care specialists such as the NCBC [32]. Treatment at these centers results in delays in care, preventing patients from receiving immediate resuscitation for severe burn management [2]. Providing context-appropriate and clear education for providers not well versed in EResus is a fundamental step in reducing the preventable morbidity and mortality that is caused by delayed, ineffective, or over-zealous resuscitation.

Although this flipbook is a novel product for EResus, similar tools exist for other burn injury education and have been proven effective at communication for providers and patients, improving overall outcomes. One such example includes the Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC) for burns, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injury [33] Infographics on the MSKTC website depict how to exercise, manage itchy skin, and understand wound dressings after a burn injury. These types of infographics fall under the “injury recovery” domain of research, as they prioritize direct patient education instead of provider knowledge [34]. The WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also create infographics and flipbooks for various topics. A large category of infographics from the WHO includes actions that can be taken for burn prevention and workplace safety [35]. The CDC provides an array of global health-centered infographics that illustrate common sources of violence and injury, including burns, in international settings [36]. These infographics from widely-known and trusted sources of health information are exceptionally helpful for providers and patients to learn more about the causes and cautions surrounding acute burn injury. However, none of the infographics are centered directly on improving education on resuscitation for these patients after a burn injury has already occurred.

Evaluating how this EResus Training Flipbook could be disseminated and scaled for use in other settings outside of Nepal is crucial. A paper by Hernandez-Sanches et al. outlines pertinent measures to ensure successful medical infographic understanding and distribution [37]. Tips they illustrate, such as defining the target audience, following the basic principles of graphic design, and testing the product with stakeholders, were followed in our study to ensure a final EResus flipbook catered to our interviewed population. The final step is the dissemination plan, which includes choosing a communication channel and media that reflects the audience’s visualization preferences—and even identifying ones that the audience does not have access to [37]–[39]. It has been cited that a printed press is recommended for health education if the target audience spans a broad range of ages. However, social media or an online platform is usually more readily preferred by the current generation [20], [40]. For the purposes of the EResus Training Flipbook, since the target audience would be various providers in Nepal and other countries, our dissemination plan relies on a printed press and an online PDF version that can be accessible via mobile phone, online, and via meetings of professional burn societies. Dissemination of this educational tool has the potential also to benefit other countries.

Although this study provides insight into the consumer testing process and potential further use of an EResus Training Flipbook, several limitations are worth consideration. First, the flipbook is out of the context of the EResus Bundle, which is a set of protocols and resources for EResus in Nepal. Although the Bundle certainly makes EResus more feasible, the flipbook can still serve as an educational tool in its absence. Second, the study population was sampled from three areas in Nepal. This sample is not necessarily indicative of burn care practices or EResus protocol implementation in all hospitals in Nepal or other low-resource settings. However, we attempted to sample healthcare workers from the primary burn care center in the country and two smaller satellite sites to increase our diversity of responses and reach the hospitals with the most impact on patient outcomes.

Additionally, the international experts and several participants in Nepal have extensive burn care experience in multiple countries. Finally, the initial flipbook version was written and surveyed in English. Therefore, we could not receive feedback on how the text in Nepali will impact understanding of the flipbook and infographics. Despite these limitations, we created an EResus Training Flipbook catered to the population interviewed based on stakeholder feedback. Future studies should aim to consumer-test this EResus Training Flipbook in other austere settings before implementing it as an educational tool. Subsequent studies should also validate the effectiveness of this educational tool in the Nepal hospital settings to determine if its use improves healthcare worker literacy in EResus implementation and, consequently, improves burn care patient outcomes.

Conclusion

Stakeholder engagement, consumer testing, and iterative revision can generate knowledge translation products to facilitate contextually appropriate education materials for inexperienced burn providers. The EResus Training Flipbook that our study developed can be used in Nepal and adapted to other contexts to facilitate the implementation of EResus globally.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The EResus Training Flipbook is appropriate for current use in Nepal burn centers.

Stakeholder-focused infographic flipbook generation improved cultural competency.

Visual infographics increase engagement and comprehension with educational tools.

Sources of Funding:

Barclay T. Stewart is funded by the United States Department of Defense Military Burn Research Program (W81XWH-21-1-0364). Kajal Mehta and Raslina Shrestha are funded by United States NIH/Fogarty International Center (D43 TW009345). Mission Plasticos provided travel support for Stephanie Francalancia, Sam Sharar, Barclay T. Stewart, and Gary Fudem.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: None

Supplementary Material Legend

Supplementary Material 1. Final EResus Training Flipbook with all revisions incorporated from the Nepali stakeholder focus groups.

Supplementary Material 2. Final EResus Training Flipbook with all revisions incorporated from the Nepali stakeholder focus groups translated into Nepali.

CRediT Author Statement

Stephanie Francalancia: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision. Kajal Mehta: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing, Investigation, Methodology. Raslina Shrestha: Funding acquisition, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Diwakar Phuyal: Investigation, Data curation. Bikash Das: Investigation, Data curation. Manish Yadav: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Project administration. Kiran Nakarmi: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Project administration. Shankar Rai: Supervision, Project administration. Sam Sharar: Supervision, Investigation, Validation. Barclay T. Stewart: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis. Gary Fudem: Supervision, Investigation, Methodology.

References

- [1].Gyedu A et al. , “Preferences for oral rehydration drinks among healthy individuals in Ghana: A single-blind, cross-sectional survey to inform implementation of an enterally based resuscitation protocol for burn injury.,” Burns J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 820–829, Jun. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2022.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Davé DR, Nagarjan N, Canner JK, Kushner AL, and Stewart BT, “Rethinking burns for low & middle-income countries: Differing patterns of burn epidemiology, care seeking behavior, and outcomes across four countries.,” Burns J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj, vol. 44, no. 5, pp. 1228–1234, Aug. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hu S et al. , “Pyruvate-enriched oral rehydration solution improved intestinal absorption of water and sodium during enteral resuscitation in burns,” Burns, vol. 40, no. 4, pp. 693–701, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Díez-Gandía A, Ajenjo MA, Navalón AB, Fernández RB, Sanz AB, and Diez-Domingo J, “Palatability of oral rehydration solutions (ORS) in healthy 6 to 9 year-old children. A multicentre, randomised single blind clinical trial,” in Anales de Pediatria (Barcelona, Spain: 2003), 2009, pp. 111–115. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [5].Li K et al. , “Identifying hospitals in Nepal for acute burn care and stabilization capacity development: location-allocation modeling for strategic service delivery,” J. Burn Care Res, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 621–626, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jeng J, Gibran N, and Peck M, “Burn care in disaster and other austere settings,” Surg. Clin, vol. 94, no. 4, pp. 893–907, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Peck M, Jeng J, and Moghazy A, “Burn resuscitation in the austere environment,” Crit. Care Clin, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 561–565, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hodgman EI, Subramanian M, Arnoldo BD, Phelan HA, and Wolf SE, “Future therapies in burn resuscitation,” Crit. Care Clin, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 611–619, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Khorasani EN and Mansouri F, “Effect of early enteral nutrition on morbidity and mortality in children with burns,” Burns, vol. 36, no. 7, pp. 1067–1071, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kramer GC et al. , “Oral and enteral resuscitation of burn shock the historical record and implications for mass casualty care,” Eplasty, vol. 10, 2010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lairet JR et al. , “Prehospital interventions performed in a combat zone: a prospective multicenter study of 1,003 combat wounded,” J. Trauma Acute Care Surg, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. S38–S42, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].W. H. Organization, “Oral rehydration salts: Production of the new ORS,” World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Binder HJ, Brown I, Ramakrishna BS, and Young GP, “Oral rehydration therapy in the second decade of the twenty-first century,” Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep, vol. 16, pp. 1–8, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hu S et al. , “Pyruvate is superior to citrate in oral rehydration solution in the protection of intestine via hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 activation in rats with burn injury,” J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr, vol. 40, no. 7, pp. 924–933, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gómez BI et al. , “Enteral resuscitation with oral rehydration solution to reduce acute kidney injury in burn victims: evidence from a porcine model,” PloS One, vol. 13, no. 5, p. e0195615, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hughes A et al. , “Recommendations for burns care in mass casualty incidents: WHO Emergency Medical Teams Technical Working Group on Burns (WHO TWGB) 2017–2020,” Burns, vol. 47, no. 2, pp. 349–370, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sagraves SG et al. , “A collaborative systems approach to rural burn care,” J. Burn Care Res, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 111–114, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Karki B et al. , “Clinical epidemiology of acute burn injuries at Nepal Cleft and Burn Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal,” Ann. Plast. Surg, vol. 80, no. 3, pp. S95–S97, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Arcia A et al. , “Sometimes more is more: iterative participatory design of infographics for engagement of community members with varying levels of health literacy.,” J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 174–183, Jan. 2016, doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McCrorie AD, Donnelly C, and McGlade KJ, “Infographics: Healthcare Communication for the Digital Age.,” Ulster Med. J, vol. 85, no. 2, pp. 71–75, May 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Royal KD and Erdmann KM, “Evaluating the readability levels of medical infographic materials for public consumption.,” J. Vis. Commun. Med, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 99–102, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.1080/17453054.2018.1476059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Martin LJ et al. , “Exploring the role of infographics for summarizing medical literature,” Health Prof. Educ, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 48–57, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Siricharoen WV and Siricharoen N, “Infographic utility in accelerating better health communication,” Mob. Netw. Appl, vol. 23, pp. 57–67, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mehta K et al. , “Development and Implementation of an Enterally Based Resuscitation Bundle for Major Burn Injury in an Austere Setting: Early Findings from a Pilot Hybrid II Effectiveness-Implementation Randomized Trial,” J. Am. Coll. Surg, vol. 235, no. 5, pp. S108–S109, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Balkac M and Ergun E, “Role of infographics in healthcare,” Chin. Med. J. (Engl.), vol. 131, no. 20, pp. 2514–2517, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ancker JS, Senathirajah Y, Kukafka R, and Starren JB, “Design features of graphs in health risk communication: a systematic review,” J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 608–618, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dean E, Caspar R, McAvinchey G, Reed L, and Quiroz R, “Developing a low‐cost technique for parallel cross‐cultural instrument development: The question appraisal system (QAS‐04),” Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 227–241, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Traboco L, Pandian H, Nikiphorou E, and Gupta L, “Designing Infographics: Visual Representations for Enhancing Education, Communication, and Scientific Research,” J. Korean Med. Sci, vol. 37, no. 27, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Eysenbach G, “Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the Internet,” J. Med. Internet Res, vol. 11, no. 1, p. e1157, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bernard HR and Gravlee CC, Handbook of methods in cultural anthropology Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, and Zoran AG, “A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research,” Int. J. Qual. Methods, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1–21, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stewart BT, Nsaful K, Allorto N, and Rai SM, “Burn Care in Low-Resource and Austere Settings,” Surg. Clin, vol. 103, no. 3, pp. 551–563, 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].“Infographics - Burn | MSKTC” Accessed: Jul. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://msktc.org/burn/infographics

- [34].Carrougher GJ et al. , “‘Living Well’ After Burn Injury: Using Case Reports to Illustrate Significant Contributions From the Burn Model System Research Program.,” J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 398–407, May 2021, doi: 10.1093/jbcr/iraa161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].“Infographics — WHO” Accessed: Jul. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/tools/compendium-on-health-and-environment/media

- [36].“Global Health Infographics | Global Health | CDC” Accessed: Jul. 19, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/infographics/default.html

- [37].Hernandez-Sanchez S, Moreno-Perez V, Garcia-Campos J, Marco-Lledó J, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, and Lozano-Quijada C, “Twelve tips to make successful medical infographics.,” Med. Teach, vol. 43, no. 12, pp. 1353–1359, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1855323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Murray IR, Murray AD, Wordie SJ, Oliver CW, Murray AW, and Simpson AHRW, “Maximising the impact of your work using infographics.,” Bone Jt. Res, vol. 6, no. 11, pp. 619–620, Nov. 2017, doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.611.BJR-2017-0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Giustini D, Ali SM, Fraser M, and Kamel Boulos MN, “Effective uses of social media in public health and medicine: a systematic review of systematic reviews.,” Online J. Public Health Inform, vol. 10, no. 2, p. e215, 2018, doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v10i2.8270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang AT, Sandhu NP, Wittich CM, Mandrekar JN, and Beckman TJ, “Using social media to improve continuing medical education: a survey of course participants.,” Mayo Clin. Proc, vol. 87, no. 12, pp. 1162–1170, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.