Abstract

Economic choice theories usually assume that humans maximize utility in their choices. However, studies have shown that humans make inconsistent choices, leading to suboptimal behavior, even without context-dependent manipulations. Previous studies showed that activation in value and motor networks are associated with inconsistent choices at the moment of choice. Here, we investigated if the neural predispositions, measured before a choice task, can predict choice inconsistency in a later risky choice task. Using functional connectivity (FC) measures from resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rsfMRI), derived before any choice was made, we aimed to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels in a later-performed choice task. We hypothesized that rsfMRI FC measures extracted from value and motor brain areas would predict inconsistency. Forty subjects (21 females) completed a rsfMRI scan before performing a risky choice task. We compared models that were trained on FC that included only hypothesized value and motor regions with models trained on whole-brain FC. We found that both model types significantly predicted inconsistency levels. Moreover, even the whole-brain models relied mostly on FC between value and motor areas. For external validation, we used a neural network pretrained on FC matrices of 37,000 subjects and fine-tuned it on our data and again showed significant predictions. Together, this shows that the tendency for choice inconsistency is predicted by predispositions of the nervous system and that synchrony between the motor and value networks plays a crucial role in this tendency.

Keywords: choice inconsistency, decision-making, functional connectivity, predictive modeling

Significance Statement

Humans often make irrational, or inconsistent, choices in value-based decision-making. Studies have suggested potential sources for this suboptimal behavior in momentary brain activity during choice, emphasizing the role of value and motor areas in the process of inconsistent choice behavior. Here, we show that inconsistency is predicted by neural predispositions, evident even before any choice was made. We predict subjects’ inconsistency levels from brain connectivity measures derived before they perform any choice task and find that inconsistency is predicted by the synchrony between the value and motor brain networks. This suggests choice inconsistency is related to a priori constraints of the nervous system and that value and motor areas play a central role in this behavior.

Introduction

A central idea in normative economic theories of choice is that decision-makers choose the options that yield the greatest subjective value to them, known as utility maximization (von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1944; Savage, 1954). To exhibit this, choosers must follow certain axioms, so they are consistent in their choices (obey transitivity), as normatively described in the General Axiom of Revealed Preference (GARP; Afriat, 1967). Briefly, a consistent subject that prefers option A over option B, and option B over option C, should prefer option A over option C. Violation of this preference relation creates a choice cycle and is defined as choice inconsistency.

But, for several decades, studies have shown that both humans and other species systematically violate this axiom in certain contexts (Kahneman and Tversky, 1984; Shafir et al., 2002). Normatively speaking, violating choice axioms means that subjects choose suboptimally and, thus, behave irrationally. That is, they do not maximize their utility and, in essence, “leave money on the table” (Dean and Martin, 2016).

It has been shown that almost every organism tested, from slime molds (Latty and Beekman, 2011), Caenorhabditis elegans (Cohen et al., 2019), bees (Shafir, 1994), birds (Shafir et al., 2002), nonhuman primates (Parrish et al., 2015), and humans (Tversky, 1969), demonstrates suboptimal choices. This suggests that suboptimality in choices is a common feature arising from physical and biological constraints of the nervous system (Simon, 1990). Nonetheless, these violations of rationality, which are considered suboptimal according to normative economic theories, might arise from a different optimization procedure, aggregating external stimuli and neurobiological constraints. Identifying these constraints is a central effort in decision neuroscience (Glimcher et al., 2005; Louie et al., 2015).

To investigate the biological constraints leading to suboptimal decisions, recent studies have explored the neural underpinnings of choice inconsistency (Kalenscher et al., 2010; Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022). They showed that the regions associated with inconsistent choices are also involved in value-based decision-making, including the striatum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC; Levy and Glimcher, 2012; Bartra et al., 2013). This suggests that noisy neural fluctuations encoding options’ value in value-related areas might elicit choice inconsistency (Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022). This notion is related to findings showing that most fluctuations in firing rates in value-related neurons occur when monkeys were indifferent between choice options, increasing the chances for inconsistent choices (Padoa-Schioppa, 2013). Another study showed that motor dynamics of subjects’ responses predict their inconsistency levels and that activity in motor areas also correlates with inconsistent choices (Kurtz-David et al., 2022). Overall, these findings show that activity in value- and motor-related areas during choice is correlated with inconsistent choice behavior.

Previous studies that examined suboptimal behavior in general, and choice inconsistency in particular, focused on the moment of choice (Louie et al., 2013; Kurtz-David et al., 2019). However, there might be general neural mechanisms that are evident even before choice, which constrain the valuation process and contribute to inconsistency. It is unclear if and to what extent these general neural mechanisms exist. Finding these a priori neural mechanisms will provide evidence that inconsistency is also related to intrinsic brain traits.

In the last decade, ample studies have used connectivity measures from task-free brain activity, such as resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI), to successfully predict diverse individual traits. These traits range from brain age (Dosenbach et al., 2010), to intelligence (Finn et al., 2015; Gal et al., 2022), decision-making (Kable and Levy, 2015), and impulsivity (Cai et al., 2020). These results support the notion that intrinsic brain connectivity, measured before the task, can predict subsequent behavior and may represent individual traits. Whether suboptimal choice, as measured by choice inconsistency, is such a trait is currently unknown.

Here, we investigate whether choice inconsistency is predicted by inherent, functional connectivity traits, preceding any choice task. Specifically, we hypothesize that functional connectivity between previously identified value and motor areas during resting-state will predict choice inconsistency as measured in a subsequent choice task.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We recruited 43 right-handed volunteering students from various departments at Tel Aviv University (21 females; mean age, 25.60 ± 4.51). Subjects gave informed written consent before participating in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee at Tel Aviv University and by the Institutional Review Board committee of Sheba Medical Center. One participant was excluded due to excessive head motion (>3 mm in translation or 30 in rotation). Two additional subjects were excluded, one due to technical problems during her experiment and another subject who did not complete the resting-state scan. Six subjects were excluded for being fully consistent in the risky choice task (see below, Inconsistency measures). We therefore report the data of the remaining 34 subjects.

Risky choice task

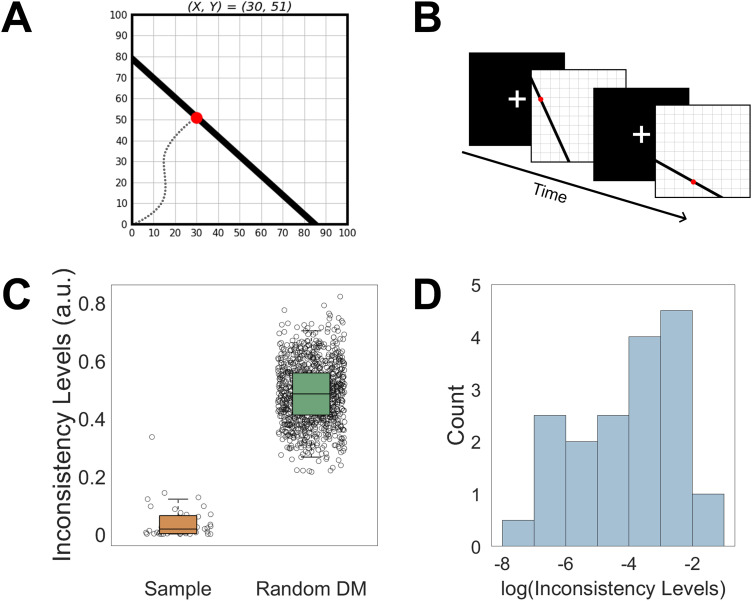

Inside the fMRI scanner, subjects made choices from linear budget sets in the context of risk (Choi et al., 2007; Kurtz-David et al., 2019). On each trial, subjects were presented with a budget line on a two-dimensional graph (Fig. 1A). Each point on the budget line corresponded to a 50–50% lottery between two amounts, X and Y. These amounts ranged between 0 and 100 and represented a token amount, where each token was worth 2 NIS (≈$0.5). Subjects could choose only points on the budget line, implying monotonicity. They were asked to choose their preferred lottery in each trial, knowing that at the end of the experiment, one trial will be selected and their selected lottery will be realized. The slope of the budget line represented the relative substitution rate (price) between X and Y. The distance of the line from the axes’ origin represented the amount of money (endowment) the subject had to spend on a given trial. The slopes and endowments were randomized across trials. Subjects made 75 unique choices, divided into three blocks of 25 trials each. On each trial, subjects had a maximum of 11 s to submit their choices, followed by a 6 s variable intertrial interval (jittered between trials; Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Task and behavioral results. A, Subjects were presented with a budget line with 50–50% lotteries between two amounts, X and Y. Each point on the line represents a different lottery between X and Y, and subjects had to choose their preferred lottery out of all possible lotteries along the budget line. For example, the red dot corresponds to a 50% chance to win 30 tokens (X) and a 50% chance to win 51 tokens (Y). The slopes and endowments of the budget lines were randomized across trials. B, Experimental design. Subjects completed 75 trials divided into three blocks of 25 trials inside the fMRI scanner. C, Subjects’ inconsistency levels measured with Afriat’s index, compared with 1,000 simulated random decision-makers. D, Subjects’ Afriat’s index distribution (log transformed).

Procedure

First, subjects read the task’s instruction sheet and then completed a questionnaire to verify they understood the task. Then, subjects completed a practice block of the task, which included a variety of slopes and endowments in a behavioral room outside the scanner. After that, subjects entered the fMRI scanner and performed a rsfMRI scan for 8 min and were asked to stay awake while staring at a fixation cross. At the end of the resting-state scan, subjects performed the experimental choice task inside the scanner. They made their choices using an MRI-compatible trackball. At the end of the experiment, one of the trials was randomly selected for monetary payment by the computer. Subjects tossed a fair coin (as the probability of getting X or Y was 50% each) to determine which account, X or Y, will be selected. Subjects received the monetary value associated with the amount of tokens they chose during the experiment to allocate for the winning account (X or Y) in the randomly selected trial. The average prize was 88.6 NIS + 100 NIS show-up fee (≈$54 total).

Inconsistency measures

Economic theory provides a set of fundamental axioms to determine the internal consistency of the choices that a subject makes within a dataset via the GARP. Briefly, a subject is said to be consistent if and only if they satisfy GARP, which means their choices do not exhibit any choice cycles (Afriat, 1967; Varian, 1982). For example, if a subject prefers option A over option B and option B over option C but prefers option C over option A, they exhibit a choice cycle and thus violate GARP. Violating GARP precludes the possibility of a subjective preference ordering and is thus considered an irrational choice. In other words, subjects violating GARP are not maximizing their utility. Several indices have been suggested to measure the intensity of GARP violations within a dataset (Afriat, 1973; Houtman and Maks, 1985; Varian, 1990; Echenique et al., 2011; Halevy et al., 2018).

Here, based on subjects’ choices in the risky choice task, we computed for each subject their Afriat’s critical cost efficiency index (Afriat’s index; Afriat, 1973), the most common index for choice inconsistency (Sippel, 1997; Harbaugh et al., 2001; Andreoni and Miller, 2002; Choi et al., 2007, 2014; Halevy et al., 2018; Dziewulski, 2020). To test for the robustness of prediction across inconsistency indices, we repeated our analyses using Varian’s index (Varian, 1990), which exhibited much lower variance than Afriat’s index ( ; Levene’s test for equal variances; see https://osf.io/j82w5/ for more details). The inconsistency measures we used to indicate the extent of GARP violations in subjects’ choices, such that a higher index indicates a higher inconsistency level (see https://osf.io/j82w5/ for a detailed description). We calculated these indices using the code package available at https://github.com/persitzd/RP-Toolkit.

To test whether our subjects were inconsistent but not random, we compared their inconsistency measures to the behavior of random decision-makers following a method developed by Bronars (1987). We generated 1,000 simulated subjects that performed 75 choices each, choosing uniformly on each budget line used in the task. We calculated Afriat’s index for each simulated subject, averaged the indices of all the simulated random choosers, and then compared the simulated average to the average of the actual subjects using a one-sided two-sample t test.

Image acquisition

Participants went through a MRI session including anatomical, rsfMRI and task fMRI scans. Note that most of the task fMRI data are not analyzed here and are reported previously (Kurtz-David et al., 2022). Scanning was performed at the Strauss Neuroimaging Center at Tel Aviv University, using a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner with a 64-channel Siemens head coil. Anatomical images were acquired using a 1 mm isotropic MPRAGE scan, which was comprised from 176 axial slices without gaps at an orientation of −30° to the AC–PC plane to reduce the signal dropout in the orbitofrontal area. The rsfMRI was acquired with a T2*-weighted functional multiband EPI pulse sequence (TR, 1 s; TE, 30 ms; flip angle, 68°; matrix, 106 × 106; FOV, 212 mm; slice thickness, 2 mm; multiband factor, 4). Sixty-four slices with no interslice gap were acquired in ascending interleaved order and aligned −30° to the AC–PC plane to reduce the signal dropout in the orbitofrontal area. The scan time of rsfMRI was 8 min, and participants were instructed to keep their eyes open. The task fMRI consisted of three runs, each lasting ∼7 min.

Preprocessing

We used the Human Connectome Project (HCP) minimal preprocessing pipeline (Glasser et al., 2013), which is a series of image processing tools designed by the HCP for optimal artifacts and distortion removal, denoising, and registration to standard space. Briefly, the fMRI data underwent gradient and EPI distortion corrections, motion correction and nonlinear alignment, and registration to the MNI standard space (Jenkinson and Smith, 2001; Jenkinson et al., 2002, 2012). The data were further denoised using FMRIB’s ICA-based Xnoiseifier (Griffanti et al., 2014; Salimi-Khorshidi et al., 2014), which identifies components of noise and motion in the functional data and removes them. Finally, the denoised data were resampled onto a surface of 91,282 “grayordinates” in standard space.

Resting-state functional connectivity analysis

To assess subjects’ intrinsic connectivity patterns, we performed two parallel analyses of functional connectivity on the fMRI surface data. The first analysis aimed to test our hypothesis about value and motor neural sources of inconsistency. We thus selected 10 hypothesized regions of interest (ROIs), including four value-related ROIs and six motor-related ROIs (henceforth, the motor–value functional connectivity). We defined the value ROIs based on previous studies and included the vmPFC, PCC, ventral striatum (Bartra et al., 2013) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (Kolling et al., 2016). We defined the motor ROIs based on the Human Motor Area Template (Mayka et al., 2006) and included the bilateral regions of M1, supplementary motor area (SMA), and pre-SMA. The second analysis was exploratory, based on a 100-node parcellation of the entire cortex (henceforth, the whole-brain functional connectivity) divided into seven distinct resting-state connectivity networks (Schaefer et al., 2018).

For both functional connectivity analyses, we averaged the resting-state BOLD signal within each region and performed a pairwise Pearson’s correlation between the average signal in each pair of regions. We then normalized the correlation coefficients using Fisher’s z transformation. Thus, for each subject, we had a 10 × 10 matrix for the motor–value functional connectivity and a 100 × 100 matrix for the whole-brain functional connectivity. As all the functional connectivity matrices were symmetrical, we used only the bottom triangle of each matrix resulting in 45 entries for the motor–value matrix and 4,950 entries for the whole-brain matrix.

Prediction models and statistical analyses

We aimed to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels from the resting-state functional connectivity matrices and explore the regions that contribute to these predictions. We thus compared three types of models with different levels of expressiveness and interpretability: Lasso regression (Tibshirani, 1996), which we used as a baseline model; Random Forest regression (Breiman, 2001), which can capture more complex relationships than the linear model but is still highly interpretable; and a pretrained neural network (meta-matching model; He et al., 2022) with high expressiveness but low interpretability. We trained the Lasso and Random Forest models for both the motor–value functional connectivity and the whole-brain functional connectivity. We trained the meta-matching model only on the whole-brain functional connectivity (as it uses a fixed-size input; see below, Meta-matching model). Overall, we trained five models. All models were implemented using Python’s scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011). We tuned the hyperparameters and evaluated all models using leave-one-out nested cross-validation. Our code is available at https://github.com/asafmm/fc_inconsistency.

Lasso and Random Forest models

Feature selection and normalization

Given the large number of features of the whole-brain functional connectivity matrix, we performed a feature selection step. We selected the top 45 features with the highest correlation in absolute value to the inconsistency levels. We selected 45 features to equate to the number of features in the motor–value functional connectivity matrix. Crucially, we selected the features using the training set and then used the same features on the test set. For the motor–value functional connectivity matrix, this step was unnecessary due to the small number of features. Next, for both matrices, we normalized the functional connectivity features within each subject to zero mean and unit variance. The normalization was done subject-wise, and not feature-wise, to account for the different ranges of connectivity features between subjects and to preserve subjects’ distinct connectivity patterns (Finn et al., 2015). Lastly, we log transformed and normalized the inconsistency levels using the mean and standard deviation of the training set and applied it on the test set.

Model evaluation

We evaluated the models using the significance of correlation between the models’ predictions and subjects’ actual inconsistency levels. We performed a one-sided permutation test for the significance of the correlation between predicted and observed measures. We permutated the predicted measures and compared the original correlation to the null correlations between observed and permuted predicted measures . We corrected these significance levels for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). To further assess and compare the prediction success between the models, we also calculated the mean squared error (MSE) and coefficient of determination for each model. Note that our permutation test is a nonparametric test for correlation significance, and not for model significance, which would have required to train thousands of models. Training thousands of models would have required months of computation time, due to the intensive nested leave-one-out cross-validation hyperparameter tuning procedure over a large grid of parameters we perform.

Feature importance analysis

To investigate the contribution of different regions to the prediction success, we calculated the feature importance of the Random Forest models using the normalized decrease in mean squared error, as implemented in Python’s scikit-learn (Pedregosa et al., 2011). The leave-one-out cross-validation resulted in 34 models, one for each subject, so we report the averaged feature importance over all 34 models. Note that each of the 34 models had different features selected in the feature selection step, so we assigned the unselected features a feature importance value of zero. Finally, we calculated a node-wise feature importance by averaging all the edge-wise feature importance, which included each node (e.g., the node importance of the PCC is the average feature importance of the edges: PCC-M1, PCC-vmPFC, etc.).

For the Lasso linear models, we performed the exact same procedure using the models’ β coefficients which were also scaled by the features’ standard deviation in each fold. We scaled the coefficients to ensure that the most important features were not selected based on their variance, as our features were not variance normalized. This scaling procedure did not affect the order of the features’ importance, as the correlation between the scaled and unscaled coefficients was very high .

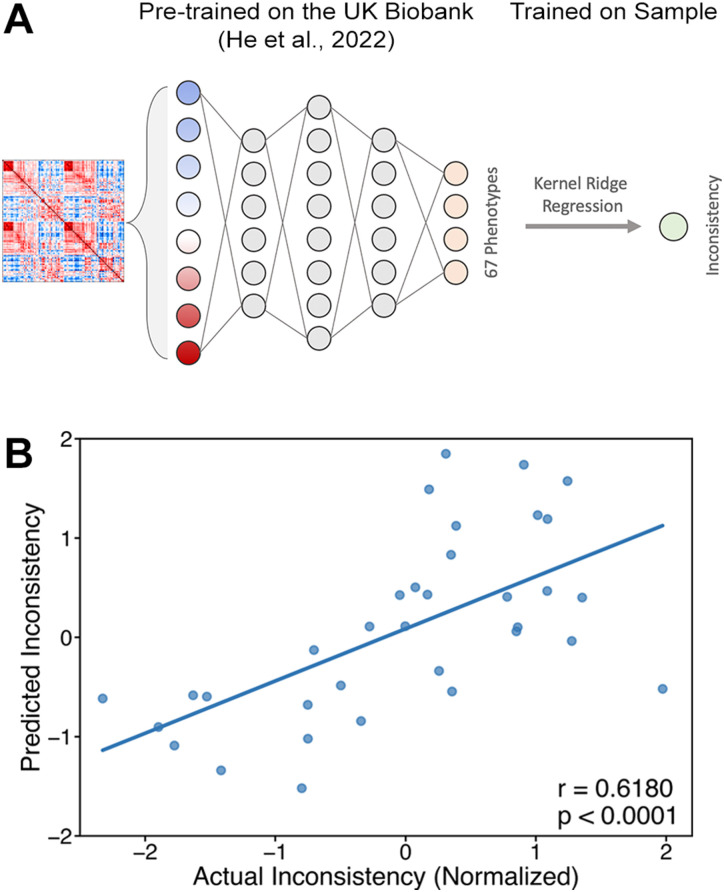

Meta-matching model

Meta-matching is a transfer-learning procedure to predict behavioral phenotypes from functional connectivity proposed and constructed by He et al. (2022). It allows to leverage the power of predictive models from large datasets such as the UK Biobank (Sudlow et al., 2015) to small “boutique” datasets like the one used in this work. Importantly, this method helps reducing the dimensionality of the brain–behavior prediction problem with an out-of-sample validated procedure (He et al., 2022). We therefore used the meta-matching framework in order to show the external validity of the prediction results in our relatively small sample.

Model structure and implementation of the meta-matching model

He et al. (2022) trained a deep neural network (DNN) using the UK Biobank to predict nonbrain-imaging phenotypes from functional connectivity. The DNN receives an input of a 419 × 419 functional connectivity matrix and yields predictions of 67 behavioral and physiological phenotypes. Then, He et al. (2022) trained a kernel Ridge regression on the DNN predictions to predict new and unseen behavioral phenotypes.

In order to apply the DNN to our data, we followed He et al.’s (2022) procedure and calculated the functional connectivity matrices with 400 cortical (Schaefer et al., 2018) and 19 subcortical (Fischl et al., 2002) parcels. Next, we applied the pretrained DNN of the meta-matching model to our functional connectivity data and got 67 predicted phenotypes for each subject. These 67 phenotypes were used as inputs to a kernel Ridge regression, which was trained to predict the inconsistency levels. We tuned the hyperparameters and evaluated the kernel Ridge regression model using nested leave-one-out procedure and then calculated the correlation between predicted and actual inconsistency levels, in an identical procedure to the one described previously.

Meta-matching feature importance analysis

Following He et al. (2022), we used the Haufe transform (Haufe et al., 2014) to interpret the results from the meta-matching model. The Haufe transform computes a feature predictive value for each input feature, such that positive values indicate the feature and predicted variable are directly proportional (higher feature value corresponds to a higher prediction) and negative values indicate an inverse proportion (higher feature value corresponds to a lower prediction). As the meta-matching model consists of two parts, we determined the predictive feature values for (1) the kernel Ridge regression based on the predicted UK Biobank phenotypes and (2) the pretrained neural network based on the functional connectivity features. For both parts, we calculated the predictive feature values for each of the 34 models (one for each fold) and then averaged them.

Task-based functional connectivity modeling

To further test the robustness of our results, we repeated our analyses on task fMRI data, using task-based functional connectivity and combined resting-state and task-based functional connectivity. To calculate task-based functional connectivity, we performed the same procedure as in the resting-state case, with an additional first step of demeaning the time series of each of the three runs and concatenating the three demeaned time series before calculating functional connectivity. For the combined resting-state and task-based functional connectivity analysis, for each subject we concatenated the bottom triangle of the two motor–value matrices (resting-state and task-based) resulting in 90 entries and the bottom triangle of the two whole-brain matrices resulting in 9,900 entries.

We then trained motor–value and whole-brain Lasso and Random Forest models in a similar procedure to the resting-state models training. For the task-based functional connectivity, the procedure was identical to the resting-state models. For the combined task-based and resting-state, we used 90 features (the entire feature set of the combined matrices) for the motor–value models, and accordingly we selected 90 features from the combined whole-brain matrices for the whole-brain models. To test the robustness of our results to modeling techniques, we also deployed the established connectome-based predictive modeling (CPM; Finn et al., 2015) method and its extensions (Gao et al., 2019), as described below.

CPM models

CPM is an established method for predicting behavioral measures from functional connectivity data (Finn et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2017). CPM includes several processing steps including (1) feature selection, based on the univariate correlations between the connectivity features and the behavioral measure, and a predefined threshold; (2) feature summarization, dividing the selected features into positively correlated and negatively correlated groups and summing each group separately; and (3) linear regression model, using the two groups’ sums as features to predict the behavioral measure. Following previous studies, we used CPM on the resting-state functional connectivity data (Finn et al., 2015), on task-based functional connectivity data (Greene et al., 2018; Feilong et al., 2021), and on the combined resting-state and task-based data (Gao et al., 2019). Specifically, on the combined data, we used two different extensions to CPM (Gao et al., 2019). The first extension uses canonical correlation analysis (CCA; cCPM) on the two functional connectivity matrices and then performs CPM on the CCA-transformed matrices, and the second uses Ridge regression CPM (rCPM) on the combined matrices instead of the feature summarization and linear regression steps of CPM. We used the default feature selection thresholds of for CPM and for cCPM and rCPM. For robustness purposes, we also tested other thresholds ( for CPM; for rCPM and cCPM).

Results

Inconsistency and choice behavior

Subjects completed a risky choice task to measure their inconsistency levels (Fig. 1A; Choi et al., 2007; Kurtz-David et al., 2019). Based on subjects’ choices, we calculated their inconsistency levels and observed an average Afriat’s index of 0.039 ( ; ; ; similar to previous studies using the same task; Halevy et al., 2018; Kurtz-David et al., 2019). Note that the higher the Afriat index, the more inconsistent the subject is. To test whether subjects chose at random, we compared their inconsistency levels with those of simulated random decision-makers and found a significant difference (Fig. 1C; p < 0.0001, one-tailed t test; Bronars, 1987), suggesting that subjects did not choose at random.

Predicting choice inconsistency from functional connectivity before the task

Our main aim was to predict choice inconsistency from neural traits that precede actual choices. To do so, we extracted functional connectivity measures from rsfMRI scans, measured before any choice task was made, and used them to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels as measured from a later choice task. We used three types of prediction models, all evaluated using leave-one-out cross-validation and present their prediction success in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between the motor–value, whole-brain, and meta-matching models

| Correlation | MSE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor–value Random Forest | 0.3631* | 0.9726 (1.0287) | 0.1226 |

| Motor–value Lasso | 0.4141** | 0.9195 (1.0127) | 0.1704 |

| Whole-brain Random Forest | 0.4238** | 0.9215 (1.2926) | 0.1687 |

| Whole-brain Lasso | 0.3514* | 1.003 (1.3963) | 0.0951 |

| Meta-matching | 0.6180*** | 0.7536 (1.1689) | 0.3201 |

Models’ performance was assessed by Pearson’s correlation (Correlation), mean squared error (MSE; standard deviation in brackets), and coefficient of determination . * , ** , *** .

Hypothesized motor–value model

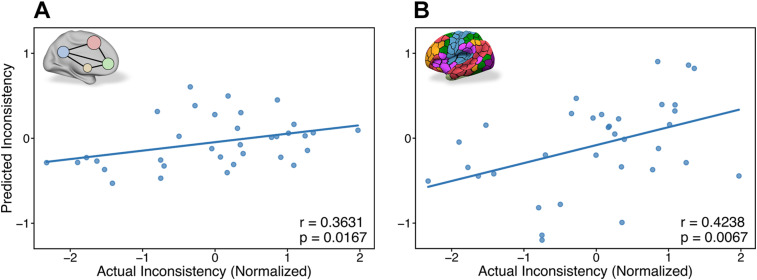

We hypothesized that the connectivity between motor and value areas preceding the task would be related to choice inconsistency, based on previous studies showing correlations between the activity in these areas and choice inconsistency during choice tasks (Kalenscher et al., 2010; Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022). We therefore trained a Random Forest model using the functional connectivity between 10 hypothesized value and motor ROIs to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels. We observed a significant correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels (Fig. 2A and Table 1; ; ). This suggests that task-free functional connectivity, which was estimated during rest, predicts inconsistency levels in the subsequent choice task. Moreover, we showed that using only the functional connectivity within motor and value regions is sufficient to predict inconsistency. We also trained a Lasso linear regression model on the same task and observed a significant correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels (Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2-1A; ; ), suggesting that the relationship between motor–value functional connectivity and inconsistency can also be captured by linear combinations. To test for the robustness of our predictions, we trained these models to predict another inconsistency measure, Varian’s index, which resulted in mixed results ( , for the Random Forest model; , for the Lasso model). However, note that Varian’s index exhibits much lower variance compared with Afriat’s index (see https://osf.io/j82w5/ for further details), therefore creating a harder prediction problem. Nevertheless, these results might not be sufficiently robust also due to the contribution of other nonhypothesized brain areas to inconsistency levels.

Figure 2.

Prediction of inconsistency from resting-state functional connectivity. Correlations between actual and predicted inconsistency levels for Random Forest models based on functional connectivity features derived before the choice task. A, Hypothesized motor–value Random Forest model predictions, using only 10 hypothesized value and motor ROIs ( ; ). B, Exploratory whole-brain Random Forest model predictions, using 100 cortical parcellation of the whole-brain ( ; ). For results of the Lasso regression models, see Extended Data Figure 2-1.

Prediction of inconsistency from resting-state functional connectivity. Correlations between actual and predicted inconsistency levels for Lasso regression models based on functional connectivity features derived before the choice task. (A) Hypothesized motor-value Lasso regression model predictions, using only 10 hypothesized value and motor ROIs ( , ). (B) Exploratory whole-brain Lasso regression model predictions, using 100 cortical parcellation of the whole-brain ( , ). Download Figure 2-1, TIF file (11.9MB, tif) .

Exploratory whole-brain model

Next, we examined whether using more brain areas in the functional connectivity model than just the predefined motor and value areas can improve our prediction of inconsistency levels. It might be that the functional connectivity between additional brain areas, which we did not hypothesize about, adds predictive power to the model. Specifically, we used a whole-brain connectivity matrix and examined if it could lead to a better prediction of choice inconsistency. We trained a Random Forest model using the functional connectivity based on a 100 cortical parcellation of the whole brain and observed a significant correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels (Fig. 2B and Table 1; ; ). We also trained a Lasso linear regression for the same task and observed a significant correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels (Table 1 and Extended Data Fig. 2-1B; ; ). As before, we repeated this analysis for Varian’s index and observed significant correlations for both the Random Forest model ( ; ) and the Lasso model ( ; ). These results show again that we can use resting-state functional connectivity to predict choice inconsistency. Moreover, it demonstrates that the whole-brain model predicts inconsistency more robustly than the restricted motor–value model, as it successfully predicts both inconsistency indices, although its predictions are not significantly different from the motor–value model’s predictions (Steiger’s Z test; ).

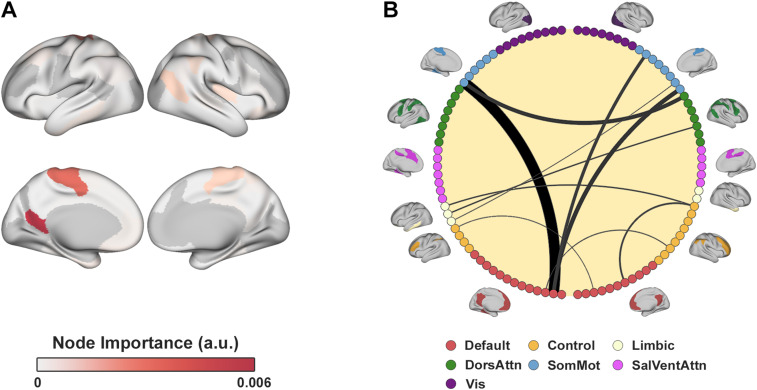

Motor and value areas are the most contributing features for inconsistency prediction

The advantage of the motor–value model is its interpretability due to the small number of features, while the whole-brain model can leverage many more features for prediction. Thus, we next sought to find the specific features used by the whole-brain model that contributed the most for predicting inconsistency. To do so, we extracted the feature importance from the whole-brain Random Forest model and depict both edge-wise and node-wise feature importance in Figure 3. The two most contributing edge-wise features were the functional connectivity between a left somatomotor area (Schaefer parcel, LH_SomMot_6) and the left PCC (Schaefer parcel, LH_Default_pCunPCC_1) and the functional connectivity between a right somatomotor area (Schaefer parcel, RH_SomMot_8) and the left PCC. Notably, the somatomotor parcels are motor related, and the PCC is one of our hypothesized value ROIs and a known region of the value network (Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014). Other contributing features included the functional connectivity between somatomotor parcels and parcels in the dorsal attention network and additional somatomotor parcels and the left PCC. Importantly, note that the motor–value model and the whole-brain model were independent from one another, meaning that there were no constraints that led the whole-brain model to select these ROIs, other than the empirical data. The whole-brain Lasso model also converged to features similar to the Random Forest model (Extended Data Table 3-1), as the correlation between the Random Forest feature importance values and the regression scaled coefficients was . These results thus show that even the whole-brain model mainly uses functional connectivity of value and motor areas to predict inconsistency, supporting our initial hypothesis.

Figure 3.

Whole-brain Random Forest model’s feature importance. A, Node-wise feature importance color-coded and projected on a brain surface. The most important nodes are the parcels in the left PCC and somatomotor areas. Node ’s importance was defined as the average of edge-wise feature importance that include node . B, Top 10 most important edge-wise features. Edge width and shade denote the feature importance. The most important features include the functional connectivity between the PCC, somatomotor areas, and a parcel in the dorsal attention network. Nodes are colored according to the seven resting-state functional networks (Yeo et al., 2011) which are also depicted on the circle’s circumference. For the feature importance of the whole-brain Lasso model, see Extended Data Table 3-1.

Top 10 functional connectivity features with the highest absolute coefficient in the whole-brain Lasso model. Features sorted by coefficient value. The bold line separates positive and negative coefficients. Download Table 3-1, DOCX file (13.4KB, docx) .

Predicting inconsistency using a model trained on a large external dataset

For external validation of our procedure, we used a model that was trained on a large external dataset, which was collected using a different scanner and includes different cognitive tasks (Sudlow et al., 2015). This model (henceforth meta-matching model) was suggested and trained by He et al. (2022) to improve the modeling of the brain–behavior relationship of small “boutique” samples like the one in this work by taking advantage of the predictive power of large datasets (Fig. 4A; see Materials and Methods for more details). Indeed, the meta-matching model resulted in a highly significant correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels (Fig. 4B and Table 1; ; ). These predictions are not statistically different from the whole-brain or motor–value models’ predictions (Steiger’s Z test; ). Here, too, we used the same model to predict Varian’s index and observed similar results ( ; ). These results show that even when using a model that was trained out-of-sample on the brain–behavior relationship, we achieve significant and robust predictions of inconsistency levels from resting-state functional connectivity. This further strengthens and validates our prediction results and suggests that task-free functional connectivity entails enough information to predict choice inconsistency.

Figure 4.

Prediction of inconsistency using the pretrained meta-matching model. A, The meta-matching framework. He et al. (2022) trained a fully connected neural network using the UK Biobank to predict 67 behavioral and physiological phenotypes from resting-state functional connectivity. Then, a kernel Ridge regression model is trained over the pretrained neural network’s prediction to predict new behavioral traits. We applied this procedure to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels. B, Correlation between actual and predicted inconsistency levels for the meta-matching model ( ; ). For the feature importance analysis of the kernel Ridge regression, see Extended Data Table 4-1. For the feature importance analysis of the neural network, see Extended Data Table 4-2.

Top 10 UKB phenotypes with the highest absolute feature predictive values (Haufe et al., 2014) in the meta-matching kernel Ridge regression model. The features are predictions of 18 UKB phenotypes (such as age) and 49 principal components of groups of phenotypes, as computed by He et al., (2022). “Breath C1” is the first principal component of the UKB spirometry measurements. “Grip C1” is the first principal component of the UKB hand grip strength measurements. “Body C1” and “Body C2” are the first two principal components of the UKB anthropometry measurements. “Blood C2” and “Blood C4” are the second and fourth principal components of the UKB blood assays results. “Alcohol 3” is the UKB average weekly beer plus cider intake. “ECG C1” is the first principal component of UKB ECG measures. “Sex G C2” is the second principal component of the UKB genotype sex inference measures. Features sorted by value. The bold line separates positive and negative values. Download Table 4-1, DOCX file (13.9KB, docx) .

Top 10 functional connectivity features with the highest absolute feature predictive values (Haufe et al., 2014) in the meta-matching neural network model. The features are based on 400 cortical (Schaefer et al., 2018) and 19 subcortical (Fischl et al., 2002) parcels. Features sorted by value. The bold line separates positive and negative values. Download Table 4-2, DOCX file (24KB, docx) .

Next, we analyzed the meta-matching model to explore the phenotypes and features that predict inconsistency using the Haufe transform (Haufe et al., 2014). First, we explored the most predictive phenotypes used by the kernel Ridge regression (Extended Data Table 4-1). These included phenotypes relating to physical strength and size such as grip strength, body size, heart activity, and breathing ability. Specifically, these have been shown to be related to hand dexterity in adults (Martin et al., 2015) and overall mobility in older adults (Sillanpää et al., 2014). This is in line with our previous results predicting inconsistency levels from subjects’ motor dynamics, showing a considerable motor component in inconsistent choice behavior (Kurtz-David et al., 2022) and provides additional support to our initial motor–value hypothesis.

Another highly contributing UKB phenotype was the predicted sex. This was surprising as there was no difference in inconsistency levels between males and females in our sample ( ), meaning that brain-derived sex is a better predictor for inconsistency than subjects’ stated sex. To explain this discrepancy, we first verified the meta-matching model predicts sex accurately and found it predicted subjects’ sex with 91.2% accuracy. Note, however, that the predicted sex is a continuous variable, ranging approximately between −1 and 1, while the reported sex is binary. This means that subjects’ predicted sex could entail more information than just their actual sex, in line with the previous findings regarding the continuum of sex-related brain features (Joel et al., 2015). For example, some male subjects are predicted with a score of 0.1, while others are predicted with a score of 0.98. This variance between subjects is used by the meta-matching model to predict inconsistency and cannot be captured by a model using their binary sex alone.

Finally, we explored the most predictive functional connectivity features that were used by the pretrained neural network. The top 10 features were almost equally weighted without any clear dominant ones and included brain areas from all functional networks (Extended Data Table 4-2). This is in contrast to the other models that relied mostly on the default and somatomotor functional networks. Note, however, that the Haufe transform assumes a linear relationship between predictions and features and is thus more suitable for linear models than for nonlinear networks (Haufe et al., 2014; He et al., 2022). Therefore, the Haufe transform might not be the most accurate representation of the network’s feature importance.

Using task-based functional connectivity to predict choice inconsistency

To further test the robustness of our results, we trained models to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels from the functional connectivity during the choice task and not only during the resting-state scan. Several previous studies have reported using task-based functional connectivity in order to predict behavioral traits, sometimes improving performance compared with resting-state–based predictions (Greene et al., 2018; Sripada et al., 2020; Feilong et al., 2021). We thus trained motor–value and whole-brain models on functional connectivity matrices based on subjects’ brain activity during the choice task. To enrich our data even further, we also trained models on the combined resting-state and task-based functional connectivity matrices (henceforth, task–rest models).

Task-based motor–value models

First, using the task-based functional connectivity between only our hypothesized motor and value areas, the task-based motor–value models showed similar results to the resting-state models with both the Random Forest and the Lasso models showing significant predictions of subjects’ inconsistency levels. Likewise, when combining resting-state and task-based functional connectivity, the task–rest motor–value models successfully predicted inconsistency once again (Random Forest, , ; Lasso, , ). Thus, our prediction pipeline produced similar results using different connectivity data, showing that the hypothesized areas and their synchronization are important predictors of choice inconsistency.

Task-based whole-brain models

Next, using task-based whole-brain functional connectivity, both task-based whole-brain models performed poorly in predicting subjects’ inconsistency levels (Random Forest, , ; Lasso, , ). Similarly, the task–rest whole-brain models failed to predict this (Random Forest, , ; Lasso, , ).

Nonetheless, in order to verify these failures are not due to our whole-brain modeling techniques, we used additional established methods to model the task-based connectomes. Specifically, we used CPM for the task-based functional connectivity (Finn et al., 2015; Greene et al., 2018). For the combined task–rest data, we also used two CPM extensions which are designed to combine several connectomes in a more principled way, including rCPM and cCPM (Gao et al., 2019).

First, as a baseline analysis, we used the CPM model on our resting-state functional connectivity data and found significant predictions of subjects’ inconsistency levels ( ; ). This shows CPM, too, captures the predictive relations between resting-state functional connectivity and choice inconsistency. Next, we trained a task-based CPM, which, like our other whole-brain models, failed to predict subjects’ inconsistency levels ( ; ), showing again the diminishing effect of our task-based data on the prediction success. However, after training the standard CPM on the combined task–rest functional connectivity, it showed significant predictions ( ; ). Likewise, when combining the two task and resting-state connectomes using rCPM ( ; ) and cCPM ( ; ), we found significant predictions of subjects’ inconsistency levels. Together, these results show that when using established methods of modeling functional connectivity, we replicated our results on whole-brain resting-state functional connectivity and extended our results for using the combined task-based and resting-state functional connectivity. These methods fail on the task data alone, further showing that only the motor–value models, and not the whole-brain models, successfully used the task-based functional connectivity to predict inconsistency, demonstrating the importance of focusing on trait-relevant regions, which are hypothesis driven.

The contrast in prediction success from the combined task–rest data between the CPM and our models shows that some methodological choices affect the prediction success. Specifically, the CPM models use almost two orders of magnitude more features than our models. To test if the number of features affects the performance, we trained our models on the task–rest data with a different feature selection threshold, selecting 1,000 features. This change resulted in significant predictions of subjects’ inconsistency levels for both the Lasso and the Random Forest models . On the other hand, selecting less features for the CPM models by raising the feature selection threshold ( for CPM; for rCPM and cCPM) provided similar results for CPM ( ; ) and rCPM ( ; ) but affected the results for cCPM ( ; ). This shows that for the task data, the choice of model and feature selection threshold fairly influences the results.

Discussion

In this work, we show that choice inconsistency can be predicted from task-free functional connectivity, before any choice was made. We successfully predicted subjects’ inconsistency levels in a risky choice task from their functional connectivity measures acquired during resting-state preceding the task. For robustness, we used three different prediction approaches. First, we showed successful predictions with an a priori hypothesized restricted model based only on functional connectivity between motor- and value-related regions that were predefined. Then, we predicted inconsistency using an exploratory unrestricted model using functional connectivity of the whole brain and showed another successful prediction. Importantly, although this model was unrestricted, we found that the most contributing features to the model’s predictions were value- and motor-related areas. Lastly, to demonstrate external validity of our findings, we used a pretrained neural network that was previously trained on a large, out-of-sample fMRI dataset (He et al., 2022) to improve the modeling of the brain–behavior relationship. Again, we significantly predicted, using functional connectivity at rest, subjects’ subsequent inconsistency levels measured during a risky choice task. Ultimately, our results suggest that choice inconsistency is related to a general trait of brain functional connectivity, preceding actual choices.

Our results emphasize the high contribution of connectivity between motor and value areas to the prediction of choice inconsistency. Previous studies have explored the neural correlates of inconsistency during choice tasks, showing that inconsistent choices correlate with brain activity in known value (Kalenscher et al., 2010; Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022) and motor (Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022) areas. These results suggest that momentary stochastic noisy activity in value and motor areas could give rise to inconsistent choices and provide two possible sources for inconsistency: motor execution and value computation errors. We extend these findings showing that not only momentary brain activity in value and motor areas can give rise to inconsistency, but also functional connectivity patterns between these brain areas, even before the task is conducted and choices are made, can predict inconsistency. This suggests that the tendency to inconsistency is related to neural predispositions, reflected here as functional connectivity, and that the synchrony of the motor and value networks plays a crucial role in this tendency.

Specifically, the PCC plays a central role in our prediction models. The PCC is regarded as a part of the default mode network during resting-state (Mak et al., 2017), a network which exhibits task-negative activity, showing high activation and synchronization at rest and low activation at times of task. However, during choice tasks, the PCC has been established as a key part of the value network, being one of the main areas that shows differential activation to the subjective value of stimuli (Levy and Glimcher, 2012; Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014). Namely, studies have shown that the PCC is activated during choices involving high-valued stimuli (Levy and Glimcher, 2012; Clithero and Rangel, 2014) and at the time of reward (Bartra et al., 2013; Clithero and Rangel, 2014). Additionally, the PCC shows greater activation when inconsistent choices occur, together with other areas of the value network (Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022), suggesting it has a special role in choice inconsistency. PCC’s role as a predictor of choice inconsistency from resting-state thus connects between its roles at rest and at the time of choice.

The connectivity patterns of motor regions also highly contributed to the prediction. This could be attributed to the substantial motor aspect of our choice task, which required subjects to move a trackball to submit their choices (see Materials and Methods). Note that some task paradigms require a simpler motor output, such as button presses (Chung et al., 2017) or verbal output. Thus, the inconsistency in these paradigms might be predicted by other brain areas and may have a smaller contribution of motor area connectivity. Future studies may use different choice task paradigms and investigate the differential predictive role of connectivity patterns to inconsistency prediction.

In the last decade, a plethora of studies have used functional connectivity to predict individual traits. These efforts span a range of domains such as physiological traits (Dosenbach et al., 2010; Weis et al., 2020), cognitive skills (Finn et al., 2015; Beaty et al., 2018; Hebling Vieira et al., 2021; Gal et al., 2022), personality traits (Dubois et al., 2018), and clinical measures (Siegel et al., 2016; Du et al., 2018). Several efforts have also been made in decision neuroscience, but most of them were focused on decision impulsivity (Schmaal et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013; Calluso et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2020; Izakson et al., 2022). Here, we extend this line of evidence for decision-making traits and show resting-state functional connectivity predicts the magnitude of deviation from normative theories in subjects’ choices.

Previous studies also used functional connectivity based on task fMRI, rather than rsfMRI, to predict behavioral traits (Greene et al., 2018; Feilong et al., 2021). Using this approach on our data, we found similar results for the hypothesized motor–value models but not for the whole-brain models, which provided more varying results. This further suggests that the hypothesized areas and their synchronization are important predictors of choice inconsistency. Additionally, this is in line with previous recent work on neural correlates of inconsistency, suggesting the activity in motor and value areas at the moment of choice are two main sources of inconsistency (Kurtz-David et al., 2019, 2022). Note that our task is unique by the significant motor element it includes, compared with the tasks used in previous studies. Consequently, our task creates high synchrony between motor and visual regions, as the relatively complex motor responses occur when the trial is presented. This might explain the discrepancy between the hypothesized and whole-brain models on the task data. Models using only the hypothesized regions are less affected by these task-specific synchronies and focus on regions which are related to the cognitive trait of interest. Alternatively, a more intensive feature selection procedure for the whole-brain models, focused on prediction success rather than univariate correlations, could have helped to resolve this issue.

Predicting any behavior from intrinsic neural traits raises the question whether this behavior is a long-term stable trait rather than a momentary changing state. A recent study has investigated the reliability and stability of behavioral choice inconsistency measures and paradigms (Nitsch et al., 2022). Specifically, the graphical paradigm (Choi et al., 2007) and inconsistency measure (Afriat, 1973) used in the current study showed moderate test–retest reliability in the time frames of few minutes and up to 5 months. Importantly, the reliability of inconsistency is similar to (if not larger than) the reported reliability of very well-known cognitive and psychological effects such as the Stroop and Flanker effects (Hedge et al., 2018). To this end, we claim that while choice inconsistency may not be a robust and stable behavioral trait over long periods of time, it also cannot be regarded merely as a momentary state. Rather, predicting inconsistency from pre-acquired functional connectivity suggests that this behavior is stable in the time frame tested in our study. Moreover, as resting-state functional connectivity properties also change over time (Noble et al., 2019), it is possible that these changes are coordinated with the changes in cognitive properties, preserving the predictive nature between the two at any timepoint.

Recently, claims have been made regarding the use of relatively small samples in brain–behavior prediction problems, leading to inflated results (Marek et al., 2022). Here, we try to overcome this limitation in several ways. First, we deploy models that use multivariate analyses and assess them using cross-validation, which prevents correlation inflations (Spisak et al., 2023). Second, we use a restricted hypothesis-driven model, which focuses our analysis on a specific set of brain regions previously identified to be related to the investigated behavior. In doing so, our prediction problem is solved in a much lower dimensional space and thus less likely to be inflated [as also suggested by Marek et al. (2022)]. Lastly, we replicated our results using the state-of-the-art “meta-matching” model (He et al., 2022), designed especially for “boutique” studies like our own. As our behavioral trait is unique, it is missing from large fMRI datasets, which contain thousands of participants. The meta-matching model uses these large fMRI datasets to translate the predictive power of thousands of participants to smaller samples in an independent out-of-sample way through dimensionality reduction of the brain–behavior prediction problem. Together, these methods control for correlation inflations.

In conclusion, this work shows that choice inconsistency can be predicted from intrinsic connectivity traits, independent and preceding actual choices. Further, we show the synchrony between areas in value and motor networks is predictive of individual levels of choice inconsistency. These results further establish the notion that suboptimal decision-making is related to predispositions of the nervous system, which are evident even at times when subjects are not engaged in any specific choice. As such, the synchrony within the value and motor neural networks could provide a mechanistic explanation for deviations from normative economic theories.

References

- Afriat SN (1967) The construction of utility functions from expenditure data. Int Econ Rev 8:67. 10.2307/2525382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afriat SN (1973) On a system of inequalities in demand analysis: an extension of the classical method. Int Econ Rev 14:460–472. 10.2307/2525934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J, Miller J (2002) Giving according to GARP: an experimental test of the consistency of preferences for altruism. Econometrica 70:737–753. 10.1111/1468-0262.00302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartra O, McGuire JT, Kable JW (2013) The valuation system: a coordinate-based meta-analysis of BOLD fMRI experiments examining neural correlates of subjective value. NeuroImage 76:412–427. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.02.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaty RE, et al. (2018) Robust prediction of individual creative ability from brain functional connectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:1087–1092. 10.1073/PNAS.1713532115/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.1713532115.SD02.TXT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B Methodol 57:289–300. 10.1111/J.2517-6161.1995.TB02031.X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45:5–32. 10.1023/A:1010933404324 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronars SG (1987) The power of nonparametric tests of preference maximization. Econometrica 55:693. 10.2307/1913608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Chen J, Liu S, Zhu J, Yu Y (2020) Brain functional connectome-based prediction of individual decision impulsivity. Cortex 125:288–298. 10.1016/J.CORTEX.2020.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calluso C, Tosoni A, Pezzulo G, Spadone S, Committeri G (2015) Interindividual variability in functional connectivity as long-term correlate of temporal discounting. PLoS ONE 10:e0119710. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0119710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Fisman R, Gale D, Kariv S (2007) Consistency and heterogeneity of individual behavior under uncertainty. Am Econ Rev 97:1921–1938. 10.1257/AER.97.5.1921 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Kariv S, Müller W, Silverman D (2014) Who is (more) rational? Am Econ Rev 104:1518–1550. 10.1257/aer.104.6.1518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HK, Tymula A, Glimcher P (2017) The reduction of ventrolateral prefrontal cortex gray matter volume correlates with loss of economic rationality in aging. J Neurosci 37:12068–12077. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1171-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clithero JA, Rangel A (2014) Informatic parcellation of the network involved in the computation of subjective value. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 9:1289–1302. 10.1093/SCAN/NST106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Teichman G, Volovich M, Zeevi Y, Elbaum L, Madar A, Louie K, Levy DJ, Rechavi O (2019) Bounded rationality in C. elegans is explained by circuit-specific normalization in chemosensory pathways. Nat Commun 10:1–12. 10.1038/s41467-019-11715-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Martin D (2016) Measuring rationality with the minimum cost of revealed preference violations. Rev Econ Stat 98:524–534. 10.1162/REST_A_00542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NUF, et al. (2010) Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI. Science 329:1358–1361. 10.1126/SCIENCE.1194144/SUPPL_FILE/DOSENBACH.SOM.REV1.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Fu Z, Calhoun VD (2018) Classification and prediction of brain disorders using functional connectivity: promising but challenging. Front Neurosci 12:525. 10.3389/FNINS.2018.00525/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois J, Galdi P, Han Y, Paul LK, Adolphs R (2018) Resting-state functional brain connectivity best predicts the personality dimension of openness to experience. Pers Neurosci 1:e6. 10.1017/PEN.2018.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziewulski P (2020) Just-noticeable difference as a behavioural foundation of the critical cost-efficiency index. J Econ Theory 188:105071. 10.1016/J.JET.2020.105071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echenique F, Lee S, Shum M (2011) The money pump as a measure of revealed preference violations. J Polit Econ 119:1201–1223. 10.1086/665011/SUPPL_FILE/2010352DATA.ZIP [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feilong M, Swaroop Guntupalli J, Haxby JV (2021) The neural basis of intelligence in fine-grained cortical topographies. ELife 10. 10.7554/ELIFE.64058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn ES, Shen X, Scheinost D, Rosenberg MD, Huang J, Chun MM, Papademetris X, Constable RT (2015) Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity. Nat Neurosci 18:1664–1671. 10.1038/nn.4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischl B, et al. (2002) Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 33:341–355. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gal S, Tik N, Bernstein-Eliav M, Tavor I (2022) Predicting individual traits from unperformed tasks. NeuroImage 249:118920. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2022.118920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S, Greene AS, Constable RT, Scheinost D (2019) Combining multiple connectomes improves predictive modeling of phenotypic measures. NeuroImage 201:116038. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2019.116038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, et al. (2013) The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage 80:105–124. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.04.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher PW, Dorris MC, Bayer HM (2005) Physiological utility theory and the neuroeconomics of choice. Games Econ Behav 52:213–256. 10.1016/J.GEB.2004.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AS, Gao S, Scheinost D, Constable RT (2018) Task-induced brain state manipulation improves prediction of individual traits. Nat Commun 9:1–13. 10.1038/s41467-018-04920-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffanti L, et al. (2014) ICA-based artefact removal and accelerated fMRI acquisition for improved resting state network imaging. NeuroImage 95:232–247. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2014.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy Y, Persitz D, Zrill L (2018) Parametric recoverability of preferences. J Polit Econ 126:1558–1593. 10.1086/697741/SUPPL_FILE/2014436DATA.ZIP [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han SD, Boyle PA, Yu L, Fleischman DA, Arfanakis K, Bennett DA (2013) Ventromedial PFC, parahippocampal, and cerebellar connectivity are associated with temporal discounting in old age. Exp Gerontol 48:1489–1498. 10.1016/J.EXGER.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbaugh WT, Krause K, Berry TR (2001) GARP for kids: on the development of rational choice behavior. Am Econ Rev 91:1539–1545. 10.1257/AER.91.5.1539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haufe S, Meinecke F, Görgen K, Dähne S, Haynes JD, Blankertz B, Bießmann F (2014) On the interpretation of weight vectors of linear models in multivariate neuroimaging. NeuroImage 87:96–110. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.10.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T, An L, Chen P, Chen J, Feng J, Bzdok D, Holmes AJ, Eickhoff SB, Yeo BTT (2022) Meta-matching as a simple framework to translate phenotypic predictive models from big to small data. Nat Neurosci 25:795–804. 10.1038/s41593-022-01059-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebling Vieira B, Dubois J, Calhoun VD, Garrido Salmon CE (2021) A deep learning based approach identifies regions more relevant than resting-state networks to the prediction of general intelligence from resting-state fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 42:5873–5887. 10.1002/HBM.25656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedge C, Powell G, Sumner P (2018) The reliability paradox: why robust cognitive tasks do not produce reliable individual differences. Behav Res Methods 50:1166–1186. 10.3758/S13428-017-0935-1/TABLES/5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtman M, Maks J (1985) Determining all maximal data subsets consistent with revealed preference. Kwantitatieve Methoden 19:89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Izakson L, Gal S, Shahar M, Tavor I, Levy DJ (2022) Similar functional networks predict performance in both perceptual and value-based decision tasks. Cereb Cortex 33:2669–2681. 10.1093/CERCOR/BHAC234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S (2002) Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage 17:825–841. 10.1016/S1053-8119(02)91132-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Woolrich MW, Smith SM (2012) FSL. NeuroImage 62:782–790. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2011.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S (2001) A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 5:143–156. 10.1016/S1361-8415(01)00036-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joel D, et al. (2015) Sex beyond the genitalia: the human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:15468–15473. 10.1073/PNAS.1509654112/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.201509654SI.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kable JW, Levy I (2015) Neural markers of individual differences in decision-making. Curr Opin Behav Sci 5:100–107. 10.1016/J.COBEHA.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A (1984) Choices, values, and frames. Am Psychol 39:341–350. 10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalenscher T, Tobler PN, Huijbers W, Daselaar SM, Pennartz C (2010) Neural signatures of intransitive preferences. Front Hum Neurosci 4:49. 10.3389/FNHUM.2010.00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolling N, Behrens TEJ, Wittmann MK, Rushworth MFS (2016) Multiple signals in anterior cingulate cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 37:36–43. 10.1016/J.CONB.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz-David V, Madar A, Hakim A, Palmon N, Levy DJ (2022) The trembling hand unraveled: the motor dynamics and neural sources of choice inconsistency. BioRxiv, 2022.12.20.521216.

- Kurtz-David V, Persitz D, Webb R, Levy DJ (2019) The neural computation of inconsistent choice behavior. Nat Commun 10:1–14. 10.1038/s41467-019-09343-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latty T, Beekman M (2011) Irrational decision-making in an amoeboid organism: transitivity and context-dependent preferences. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 278:307. 10.1098/RSPB.2010.1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy DJ, Glimcher PW (2012) The root of all value: a neural common currency for choice. Curr Opin Neurobiol 22:1027–1038. 10.1016/J.CONB.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Ma N, Liu Y, He XS, Sun DL, Fu XM, Zhang X, Han S, Zhang DR (2013) Resting-state functional connectivity predicts impulsivity in economic decision-making. J Neurosci 33:4886–4895. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1342-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie K, Glimcher PW, Webb R (2015) Adaptive neural coding: from biological to behavioral decision-making. Curr Opin Behav Sci 5:91–99. 10.1016/J.COBEHA.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie K, Khaw MW, Glimcher PW (2013) Normalization is a general neural mechanism for context-dependent decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:6139–6144. 10.1073/PNAS.1217854110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak LE, Minuzzi L, MacQueen G, Hall G, Kennedy SH, Milev R (2017) The default mode network in healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Connect 7:25–33. 10.1089/BRAIN.2016.0438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek S, et al. (2022) Reproducible brain-wide association studies require thousands of individuals. Nature 603:654–660. 10.1038/s41586-022-04492-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Ramsay J, Hughes C, Peters DM, Edwards MG (2015) Age and grip strength predict hand dexterity in adults. PLoS ONE 10:e0117598. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0117598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayka MA, Corcos DM, Leurgans SE, Vaillancourt DE (2006) Three-dimensional locations and boundaries of motor and premotor cortices as defined by functional brain imaging: a meta-analysis. NeuroImage 31:1453–1474. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2006.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch FJ, Lüpken LM, Lüschow N, Kalenscher T (2022) On the reliability of individual economic rationality measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119. 10.1073/pnas.2202070119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble S, Scheinost D, Constable RT (2019) A decade of test-retest reliability of functional connectivity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage 203. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2019.116157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padoa-Schioppa C (2013) Neuronal origins of choice variability in economic decisions. Neuron 80:1322–1336. 10.1016/J.NEURON.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish AE, Evans TA, Beran MJ (2015) Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) exhibit the decoy effect in a perceptual discrimination task. Attent Percept Psychophys 77:1715–1725. 10.3758/S13414-015-0885-6/TABLES/2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa F, et al. (2011) Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res 12:2825–2830. http://scikit-learn.sourceforge.net. [Google Scholar]

- Salimi-Khorshidi G, Douaud G, Beckmann CF, Glasser MF, Griffanti L, Smith SM (2014) Automatic denoising of functional MRI data: combining independent component analysis and hierarchical fusion of classifiers. NeuroImage 90:449–468. 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.11.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage LJ (1954) The foundations of statistics. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, Kong R, Gordon EM, Laumann TO, Zuo X-N, Holmes AJ, Eickhoff SB, Yeo BTT (2018) Local-global parcellation of the human cerebral cortex from intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Cereb Cortex 28:3095–3114. 10.1093/CERCOR/BHX179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaal L, Goudriaan AE, van der Meer J, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ (2012) The association between cingulate cortex glutamate concentration and delay discounting is mediated by resting state functional connectivity. Brain Behav 2:553–562. 10.1002/BRB3.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafir S (1994) Intransitivity of preferences in honey bees: support for “comparative” evaluation of foraging options. Anim Behav 48:55–67. 10.1006/ANBE.1994.1211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafir S, Waite TA, Smith BH (2002) Context-dependent violations of rational choice in honeybees (Apis mellifera) and gray jays (Perisoreus canadensis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 51:180–187. 10.1007/S00265-001-0420-8/METRICS [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Finn ES, Scheinost D, Rosenberg MD, Chun MM, Papademetris X, Constable RT (2017) Using connectome-based predictive modeling to predict individual behavior from brain connectivity. Nat Protoc 12:506–518. 10.1038/NPROT.2016.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JS, Ramsey LE, Snyder AZ, Metcalf Nv, Chacko Rv, Weinberger K, Baldassarre A, Hacker CD, Shulman GL, Corbetta M (2016) Disruptions of network connectivity predict impairment in multiple behavioral domains after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:E4367–E4376. 10.1073/PNAS.1521083113/SUPPL_FILE/PNAS.201521083SI.PDF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää E, et al. (2014) Associations between muscle strength, spirometric pulmonary function and mobility in healthy older adults. Age 36:9667. 10.1007/S11357-014-9667-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon HA (1990) Bounded rationality. In: Utility and probability (Eatwell J, Milgate M, Newman P, eds), pp 15–18. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Sippel R (1997) An experiment on the pure theory of consumer’s behaviour. Econ J 107:1431–1444. 10.1111/J.1468-0297.1997.TB00056.X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spisak T, Bingel U, Wager TD (2023) Multivariate BWAS can be replicable with moderate sample sizes. Nature 615:E4–E7. 10.1038/s41586-023-05745-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripada C, Angstadt M, Rutherford S, Taxali A, Shedden K (2020) Toward a “treadmill test” for cognition: improved prediction of general cognitive ability from the task activated brain. Hum Brain Mapp 41:3186–3197. 10.1002/HBM.25007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudlow C, et al. (2015) UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 12:e1001779. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PMED.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R (1996) Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc B Methodol 58:267–288. 10.1111/J.2517-6161.1996.TB02080.X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tversky A (1969) Intransitivity of preferences. Psychol Rev 76:31–48. 10.1037/H0026750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varian HR (1982) The nonparametric approach to demand analysis. Econometrica 50:945. 10.2307/1912771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varian HR (1990) Goodness-of-fit in optimizing models. J Econom 46:125–140. 10.1016/0304-4076(90)90051-T [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Neumann J, Morgenstern O (1944) Theory of games and economic behavior. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weis S, Patil KR, Hoffstaedter F, Nostro A, Yeo BTT, Eickhoff SB (2020) Sex classification by resting state brain connectivity. Cereb Cortex 30:824–835. 10.1093/CERCOR/BHZ129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo BTT, et al. (2011) The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol 106:1125–1165. 10.1152/JN.00338.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Prediction of inconsistency from resting-state functional connectivity. Correlations between actual and predicted inconsistency levels for Lasso regression models based on functional connectivity features derived before the choice task. (A) Hypothesized motor-value Lasso regression model predictions, using only 10 hypothesized value and motor ROIs ( , ). (B) Exploratory whole-brain Lasso regression model predictions, using 100 cortical parcellation of the whole-brain ( , ). Download Figure 2-1, TIF file (11.9MB, tif) .

Top 10 functional connectivity features with the highest absolute coefficient in the whole-brain Lasso model. Features sorted by coefficient value. The bold line separates positive and negative coefficients. Download Table 3-1, DOCX file (13.4KB, docx) .

Top 10 UKB phenotypes with the highest absolute feature predictive values (Haufe et al., 2014) in the meta-matching kernel Ridge regression model. The features are predictions of 18 UKB phenotypes (such as age) and 49 principal components of groups of phenotypes, as computed by He et al., (2022). “Breath C1” is the first principal component of the UKB spirometry measurements. “Grip C1” is the first principal component of the UKB hand grip strength measurements. “Body C1” and “Body C2” are the first two principal components of the UKB anthropometry measurements. “Blood C2” and “Blood C4” are the second and fourth principal components of the UKB blood assays results. “Alcohol 3” is the UKB average weekly beer plus cider intake. “ECG C1” is the first principal component of UKB ECG measures. “Sex G C2” is the second principal component of the UKB genotype sex inference measures. Features sorted by value. The bold line separates positive and negative values. Download Table 4-1, DOCX file (13.9KB, docx) .

Top 10 functional connectivity features with the highest absolute feature predictive values (Haufe et al., 2014) in the meta-matching neural network model. The features are based on 400 cortical (Schaefer et al., 2018) and 19 subcortical (Fischl et al., 2002) parcels. Features sorted by value. The bold line separates positive and negative values. Download Table 4-2, DOCX file (24KB, docx) .