Abstract

Suicide is a leading cause of death among youth, and emergency departments (EDs) play an important role in caring for youth with suicidality. Shortages in outpatient and inpatient mental and behavioral health capacity combined with a surge in ED visits for youth with suicidal ideation (SI) and self‐harm challenge many EDs in the United States. This review highlights currently identified best practices that all EDs can implement in suicide screening, assessment of youth with self‐harm and SI, care for patients awaiting inpatient psychiatric care, and discharge planning for youth determined not to require inpatient treatment. We will also highlight several controversies and challenges in implementation of these best practices in the ED. An enhanced continuum of care model recommended for youth with mental and behavioral health crises utilizes crisis lines, mobile crisis units, crisis receiving and stabilization units, and also maximizes interventions in home‐ and community‐based settings. However, while local systems work to enhance continuum capacity, EDs remain a critical part of crisis care. Currently, EDs face barriers to providing optimal treatment for youth in crisis due to inadequate resources including the ability to obtain emergent mental health consultations via on‐site professionals, telepsychiatry, and ED transfer agreements. To reduce ED utilization and better facilitate safe dispositions from EDs, the expansion of community‐ and home‐based services, pediatric‐receiving crisis stabilization units, inpatient psychiatric services, among other innovative solutions, is necessary.

Keywords: mental and behavioral health, pediatric emergency, psychiatric emergency, suicide

1. BACKGROUND

The United States has a youth suicide crisis. Suicide is in the top three causes of death among 10–24‐year olds, 1 with death by suicide rates surging 62% from 2007 to 2021. 2 In 2021, 9% of US high school students reported a suicide attempt in the preceding year. In 2020, there were 224,341 emergency department (ED) visits for self‐harm for 10–24‐year olds, 3 with ED visit rates doubling for girls from 2001 to 2020. 3 Increased mental and behavioral health (MBH)‐related ED visits, 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 combined with limited inpatient and outpatient MBH resources, are straining US EDs. Most youth present to general EDs with variable access to both pediatric‐specific and MBH resources. 8 A study including 3612 US EDs found that most do not have defined policies for the care of youth with MBH conditions. 9 Additionally, an Emergency Nurses Association report found that emergency clinicians are often not comfortable with the care of patients with MBH conditions. 10 Over half of youth in MBH crisis in the ED require inpatient psychiatric care. Many experience boarding or a prolonged ED length of stay (LOS) after a disposition decision. 11 The lack of resources and barriers to optimal care for youth with MBH conditions are not only distressing to patients and families, but also cause moral distress to ED staff. 12

1.1. Current state of outpatient pediatric MBH care

As of 2016, most US states had fewer than 10 child psychiatrists for every 100,000 children, and 70% of counties had none. 13 In a national survey, 85% of primary care practices reported struggling to obtain advice and services for patients with MBH conditions. 14 Only 20–50% of youth with a MBH condition receive treatment from a MBH professional, 15 , 16 and those receiving services often wait months for appointments. 17 Additionally, specific populations within the US experience added challenges to accessing outpatient MBH care. Youth in rural or low‐income areas are less likely to have access to child psychiatrists, including via telehealth. 13 , 18 Although not pediatric specific, research conducted in New York City found a particular shortage of MBH providers for patients who do not speak English. 19 Sexual and gender minority populations have a high rate of suicide attempts and face additional obstacles, including fear of discrimination, when accessing MBH care. 20 Furthermore, financial barriers for some youth exist; MBH providers may not accept Medicaid or other forms of insurance payment. 19 Transportation and caregiver lost wages may also serve as barriers to appointment attendance. 21 Lack of access to outpatient MBH services likely contributes to patients presenting for ED care and complicates ED disposition, potentially resulting in hospitalization of some patients who could have been discharged if prompt outpatient MBH services were available.

1.2. Current state for patients requiring inpatient MBH care

Acute MBH inpatient bed numbers have been declining for decades in the US, contributing to increased ED MBH boarding. 11 , 22 , 23 ED boarding is common despite the detrimental effects on patients, families, and staff. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Youth can wait for days, weeks, and at times, months, in both children's hospital and general EDs. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 In one systematic review, 23–58% of youth requiring inpatient psychiatric care experienced boarding, and average ED boarding time ranged from 5 to 41 hours. 11

Certain groups of patients are disproportionally impacted by a lack of inpatient beds. Many facilities are not equipped to care for youth with special healthcare needs and chronic disorders, such as diabetes and epilepsy, resulting in additional barriers to inpatient psychiatric placement and longer ED stays. 34 Youth with autism spectrum disorder and developmental delay face increased ED LOS. 35 Additionally, racial and ethnic disparities exist; in one study, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with an almost threefold odds of an ED LOS >12 hours. 23 Prolonged boarding times and disparities are concerning as youth boarding in EDs or pediatric medical units while awaiting inpatient psychiatric placement are unlikely to receive optimal MBH treatment. 36 , 37 , 38

1.3. Scope of this review

In 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) declared a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. 39 Until significant systems changes occur, the ED may serve as the only point of care for youth struggling with self‐harm or suicidal ideation (SI). We therefore conducted a review of existing literature of ED care of youth (<18 years) and present currently identified best practices in suicide screening, assessment of youth with SI, care for patients awaiting inpatient psychiatric care, and discharge planning for youth that all EDs can implement. We also highlight several controversies and challenges in implementation of these best practices and offer possible next steps in research and advocacy.

2. ED SUICIDE SCREENING

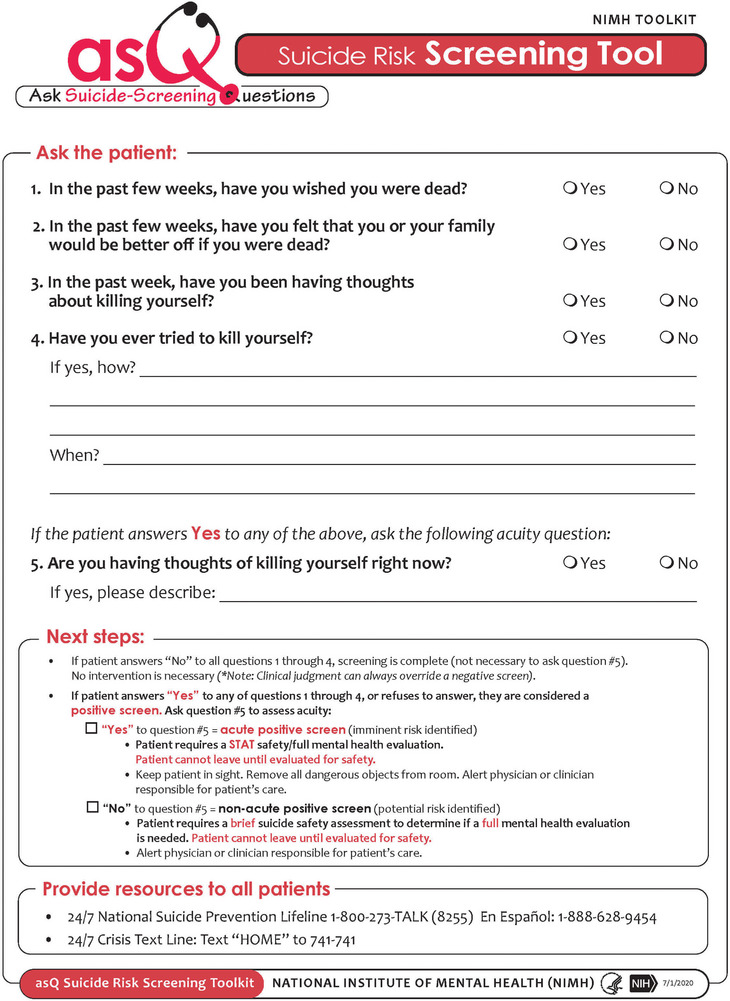

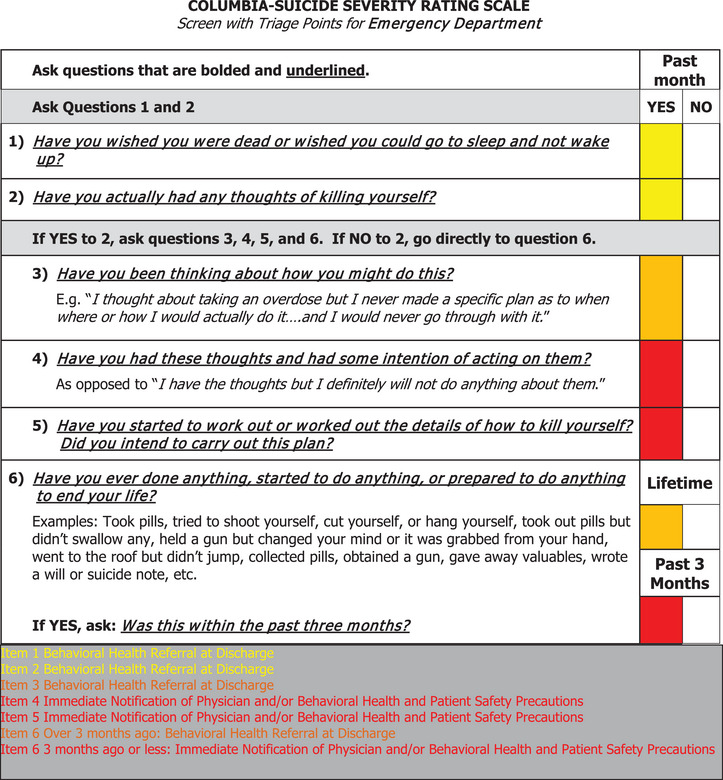

The Joint Commission requires EDs to screen for suicide risk using a validated tool in patients 12 years of age and older presenting for evaluation or treatment of MBH symptoms. 40 Two brief validated tools commonly used in the ED setting are the Ask Suicide–Screening Questions (ASQ) instrument and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C‐SSRS). The ASQ, designed to screen 10–24‐year olds, has been demonstrated to have high sensitivity and negative predictive value (Figure 1). 41 The full toolkit is available at https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials. The C‐SSRS (Figure 2), useful in children as young as 6 years old, 42 is available at https://cssrs.columbia.edu/. A more recently validated tool, the Computerized Adaptive Screen for Suicidal Youth (CASSY), predicts probability of a suicide attempt in the next 3 months. 43 , 44 The CASSY holds promise for suicide screening and risk stratification but requires set up and annual fees for use. 45

FIGURE 1.

Ask Suicide–Screening Questions (ASQ) suicide risk screening tool.

FIGURE 2.

Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale.

2.1. Universal suicide screening

Implementation of universal ED suicide screening is controversial and recommendations vary among different national medical organizations. In 2022, the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded that evidence was inadequate to recommend universal screening for suicide risk in youth. However, some experts call for universal suicide screening of adolescents 46 , 47 given that most youth with a suicide attempt had a healthcare visit in the prior year. 48 A major concern about universal suicide screening in the ED is the negative impact on patient LOS. A modeling study concluded that although universal screening would likely not negatively impact ED LOS, abrupt implementation could significantly stress already stretched ED resources. 49 Further study is needed on universal suicide screening efficacy and impact on ED flow.

3. ED ASSESSMENT OF YOUTH WITH SI

3.1. Legal considerations

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) mandates that even EDs without dedicated MBH services conduct medical screening examinations and provide stabilizing care for patients presenting with MBH symptoms. 50 , 51 Stabilizing patients with SI may include evaluating and treating self‐harm, determining if MBH consultation is needed, and potentially arranging for an involuntary psychiatric hold for patients presenting with concern for danger to themselves or others, or with grave disability. Variability in state involuntary psychiatric hold laws, 52 including criteria for initiating holds, which medical professionals can initiate holds, and patient rights during holds, 52 present a challenge to EDs. Therefore, emergency physicians (EPs) must understand local laws and institutional policies. 53 Caregivers sometimes want to leave the ED with their child, either because they disagree with the need for hospitalization or because of delays in the admission or transfer process. If careful discussion with the caregivers fails to resolve the situation, hospital risk management, law enforcement, and child protective services may need to be involved.

3.2. Laboratory assessment

Historically, inpatient facilities required laboratory testing as part of the medical evaluation (colloquially known as “medical clearance”) prior to psychiatric evaluation or admission. 54 Routine laboratory testing is costly in terms of resources and ED LOS with an extremely low yield of unexpected, clinically important findings requiring a change in medical management. 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 The AAP and the Choosing Wisely Campaign recommend against screening laboratory testing in pediatric patients before psychiatric admission unless clinically indicated. 60 EPs can advocate to end requirements in their systems for routine laboratory evaluation and instead allow clinical evaluation to guide the need for testing. 61

3.3. Initial safety assessment

There is a lack of consensus on when MBH clinicians should be involved in the assessment of pediatric suicide risk in the ED. Some experts suggest that EPs should receive training in suicide risk assessment, collaborating with MBH professionals when needed. 62 , 63 , 64 Additional resources are needed, however, to support EPs in assessments. One risk assessment tool, the Suicide Assessment Five‐step Evaluation and Triage, 65 helps identify risk factors and protective factors, determine risk level, and guide the level of intervention. It is available at https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma09-4432.pdf and as a phone application. Another risk assessment tool, the ASQ Brief Suicide Safety Assessment, is available as part of the ASQ toolkit, 66 with free online training available. 67

3.4. MBH consultation

Most US EDs lack adequate MBH clinician coverage to assess all youth with SI and other MBH emergencies. 68 Options for obtaining emergent MBH consultation for EDs without on‐site MBH clinicians include telepsychiatry and transfer. Telepsychiatry enables off‐site MBH professionals to provide comprehensive screening and safety assessments, determine acuity, and assist with disposition. 69 Telepsychiatry services require set‐up and maintenance costs. 70 , 71 Additional considerations are licensing, insurance, and wireless service availability, which may be a particular challenge in rural and low‐resourced areas. 71 Alternatively, EDs may arrange transfer for psychiatric evaluation and safety assessment, ensuring compliance with EMTALA‐mandated transfer requirements, including arrangements for safe transport to the receiving facility. 72 , 73

4. ED CARE FOR YOUTH AWAITING INPATIENT MBH TREATMENT

Best practices for youth awaiting inpatient MBH care include ensuring a safe ED environment and implementing a patient daily schedule.

4.1. Safe environment

Since ED LOS for youth with MBH conditions has substantially increased over time, development of standardized local processes for youth at risk of suicide is imperative to keep youth awaiting inpatient care safe. If available, patients should be in a specific safe room with potentially dangerous items such as cords either removed or secured to prevent self‐harm or use as a weapon to harm others. A sample room safety checklist is available on the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) Innovation and Improvement Center New England Regional Behavioral Health Toolkit website. 74

4.2. Daily schedule

EDs may consider implementing a daily schedule to provide a routine and expectations for patients with prolonged ED stays. Daily schedules can be reviewed with youth and families and can enhance patient‐centered care. Further information including a templated daily schedule that can be modified based on local needs is available at EMSC Innovation and Improvement Center New England Regional Behavioral Health Toolkit website. 74

4.3. Daily psychiatric evaluation

A pediatric psychiatry expert group conducted a Delphi consensus study and recommended daily evaluation by a psychiatry team on all youth boarding in EDs awaiting an inpatient psychiatric bed. 38 Although it is optimal for youth experiencing ED boarding to be re‐evaluated by MBH professionals, this is not feasible in many ED settings. A 2008 American College of Emergency Physicians survey found that 62% of 328 ED directors reported having no formal psychiatric involvement with ED patients boarding while awaiting psychiatric admission or transfer. 25 Access to pediatric MBH specialists is an even greater challenge for rural EDs. 9 Given the immense challenge of ensuring that all EDs have the resources to provide daily psychiatric re‐evaluations and the known problems of boarding, efforts to address underlying causes of ED boarding are needed.

5. DISCHARGE PLANNING

Discharge planning for youth with SI who are determined not to require inpatient levels of care can be challenging. One practice that is no longer recommended is the “no suicide contract” (also known as a “no harm contract” or “safety contract”). 41 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 A “no suicide contract” is an agreement in which the patient pledges not to self‐harm or attempt suicide, with a contingency plan if a situation develops where they feel that they would not be able to honor this contract. Previously, patient willingness to engage in a contract was felt to be one method of risk assessment. Most recent research suggests that these contracts do not reduce suicide risk and may actually increase suicidal behavior and medicolegal liability. 79 , 80

5.1. Safety planning

Currently recommended best practices for brief ED‐based interventions intended to prevent suicide attempts are safety planning, including lethal means counseling, as well as connecting patients to outpatient resources. Safety planning has shown potential to decrease suicidal behaviors in adults 81 , 82 , 83 and may help reduce the risk of suicide in youth. 84 Components of safety planning include: recognizing warning signs of an impending crisis; employing internal coping strategies; utilizing social contacts as a means of distraction from suicidal thoughts; contacting family members or friends who may help to resolve the crisis; contacting MBH professionals. 82 , 85 Tools such as the Stanley–Brown Safety Plan can assist EPs with discharge planning. 82 , 86 Safety planning seems especially effective when paired with structured outpatient follow‐up. 83

Safety planning includes counseling on lethal means restriction 87 , 88 , 89 or decreasing access to lethal means such as firearms, sharp objects, and medications. 90 The sometimes transient nature of SI and the impulsivity of youth suggests that limiting access to lethal methods may deter some youth from suicide. 91 One study found that most youth with nonfatal suicide attempts progressed from deciding to attempt suicide to implementing their plan under 1 h. 92 There is significant variability in lethal means counseling in EDs. 90 , 93 Formal training such as the Counseling on Access to Lethal Means program may lower provider barriers to providing this intervention. 94 , 95

5.2. Challenges in ED delivery of safety planning

In addition to the paucity of data on efficacy of suicide prevention interventions, many EDs lack resources 96 to provide these interventions. Payment is variable; insurance companies do not reimburse all billing codes. 97 Even low‐cost interventions require a health system or societal investment. Implementation of suicide prevention services requires funding to train staff in services such as suicide risk screening and safety planning, and institutional electronic medical record system changes. 98 EPs can advocate to improve payment for ED‐based suicide assessment and brief suicide prevention interventions. Additionally, further research on efficacy and how best to implement suicide prevention services is needed.

5.3. Outpatient MBH follow‐up

Close outpatient follow‐up with a MBH professional after an ED visit for MBH symptoms may increase engagement with MBH care. 99 Rates of follow‐up with a MBH professional within 7 and 30 days are currently part of the National Child Core set of quality measures by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 100 , 101 However, ensuring rapid access to outpatient MBH follow‐up is extraordinarily challenging: only 31.2% of pediatric patients had an outpatient MBH visit within 7 days after an ED MBH‐related visit, and only 55.8% had a visit within 30 days. 102 One institution addressed the MBH follow‐up challenge by creating a Bridge Clinic and Intensive Outpatient Therapy Clinic. These services allow youth who are in crisis but not actively suicidal to be diverted from the ED to outpatient care and provide next day follow‐up for youth in MBH crisis after ED discharge. The Bridge Clinic allows for outpatient therapy until a longer‐term outpatient therapist can be scheduled. 103 Additional strategies to improve access to outpatient follow‐up may include enhancing school‐based MBH services and providing support and training to primary pediatricians who may then be able to serve as follow‐up providers. 103

6. A NEW MODEL—A COMPREHENSIVE CRISIS RESPONSE SYSTEM

A novel strategy to address the MBH crisis is development of a more robust crisis continuum of care to meet the needs of youth and families available to anyone, anywhere, and anytime. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration suggests essential elements of a crisis continuum for youth are “someone to talk to” (crisis line services), “someone to respond” (mobile crisis units), and “a safe place to be” (including options for crisis stabilization locations, ED, psychiatric inpatient care, or home‐based stabilization services). 104 This model is different than adult crisis systems, with a significant effort to keep youth in their current living environment and in a family‐based setting, with engagement from family and community members. 105

One recent improvement in “someone to talk to” is the creation of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (9‐8‐8). EDs can provide this resource as part of a safety plan or even to all adolescents as anticipatory guidance. People can access the lifeline by calling or texting 9‐8‐8 or visiting the website 988lifeline.org to communicate with trained individuals who are able to resolve approximately 80% of crisis calls remotely. 106 For calls requiring in‐person intervention, mobile crisis units (someone to respond) can aid youth and families in their own environment. Mobile crisis units can perform brief safety assessments and engage youth and families in care planning with a goal to divert youth from restrictive levels of care and unnecessary contact with law enforcement. 107 Mobile crisis services have been shown to have the potential to decrease ED/hospital utilization and connect patients to outpatient resources. 108 , 109 , 110 For patients requiring further acute care, crisis stabilization units, also known as “23‐hour units,” or emergency psychiatry assessment, treatment, and healing units (EmPATH units), can provide urgent diagnostic assessment, crisis intervention, treatment, and support. 111 Crisis stabilization units have been shown in adults to reduce psychiatric holds, increase outpatient follow‐up, reduce ED LOS, and reduce inpatient MBH admissions. 111 Further study exploring how existing infrastructure can be tailored to serve youth and greater understanding of how the crisis continuum model impacts outcomes for youth is needed.

7. CONCLUSIONS

The entire continuum of care for youth in need of MBH treatment must be strengthened to address the US youth suicide crisis. Availability of more MBH professionals comfortable with the care of youth and availability of inpatient psychiatric services for all patients would help to alleviate the current crisis. Although improved access to outpatient MBH and crisis services might decrease ED visits for SI, the ED will continue to be part of this continuum of care. We have highlighted several best practices that can be employed to improve care for youth with SI (Table 1). Further research is necessary on ED‐based suicide prevention interventions and ED risk stratification tools. Additionally, resources are needed to support EDs in implementing these strategies and facilitate safe discharge when possible, and transfer or admission to appropriate services, when necessary.

TABLE 1.

Recommendations for emergency department care of youth who present with self‐harm or suicidal behaviors.

Suicide screening

|

ED assessment

|

ED care of patients who require inpatient mental and behavioral health treatment

|

Discharge planning

|

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This work was the product of a subcommittee of the American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee. All authors contributed to writing a section of the manuscript and all authors had the opportunity to critically review and edit the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the American College of Emergency Physicians Pediatric Emergency Medicine Committee for review of this manuscript.

Biography

Genevieve Santillanes, MD is an associate professor of emergency medicine at Keck School of Medicine of USC. She practices pediatric emergency medicine at Los Angeles General Hospital in Los Angeles, CA.

Santillanes G, Foster AA, Ishimine P, et al. Management of youth with suicidal ideation: Challenges and best practices for emergency departments. JACEP Open. 2024;5:e13141. 10.1002/emp2.13141

Supervising Editor: Matthew Hansen, MD, MCR

REFERENCES

- 1. WISQARS—Leading Cause of Death Reports, 1981–2020. In: Center for Disease Control and Prevention NCfIPaC, ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Curtin SC, Garnett MF. Suicide and homicide death rates among youth and young adults aged 10–24: United States, 2001–2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023(471):1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones SE, Ethier KA, Hertz M et al. Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID‐19 pandemic — adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR Supplements. 2022;71(3):16–21. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emergency department visits by patients with mental health disorders–North Carolina, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(23):469‐472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mapelli E, Black T, Doan Q. Trends in pediatric emergency department utilization for mental health‐related visits. J Pediatr. 2015;167(4):905‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sheridan DC, Spiro DM, Fu R, et al. Mental health utilization in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(8):555‐559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Emergency department visits for mental health conditions among US children, 2001–2011. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(14):1359‐1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):598‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cree RA, So M, Franks J, et al. Characteristics associated with presence of pediatric mental health care policies in emergency departments. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(12):e1116‐e1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A. M. Care of the psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Emergency Nurses’ Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. McEnany FB, Ojugbele O, Doherty JR, et al. Pediatric mental health boarding. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e20201174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foster AA, Sundberg M, Williams DN, et al. Emergency department staff perceptions about the care of children with mental health conditions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;73:78‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McBain RK, Kofner A, Stein BD, et al. Growth and distribution of child psychiatrists in the United States: 2007–2016. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chien AT, Leyenaar J, Tomaino M, et al. Difficulty obtaining behavioral health services for children: a national survey of multiphysician practices. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(1):42‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Best Principles for Integration of Child Psychiatry into the Pediatric Health Home. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Whitney DG, Peterson MD. US national and state‐level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):389‐391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cama S, Malowney M, Smith AJB, et al. Availability of outpatient mental health care by pediatricians and child psychiatrists in five U.S. cities. Int J Health Serv. 2017;47(4):621‐635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McBain RK, Cantor JH, Kofner A, et al. Ongoing disparities in digital and in‐person access to child psychiatric services in the United States. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61(7):926‐933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Breslau J, Barnes‐Proby D, Bhandarkar M, et al. Availability and accessibility of mental health services in New York City. Rand Health Q. 2022;10(1):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoffmann JA, Alegría M, Alvarez K, et al. Disparities in pediatric mental and behavioral health conditions. Pediatrics. 2022;150(4):e2022058227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, et al. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(6):623‐647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuller DA, Sinclair E, Geller J, et al. Going, Going, Gone: Trends and Consequences of Eliminating State Psychiatric Beds. Treatment Advocacy Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nash KA, Zima BT, Rothenberg C, et al. Prolonged emergency department length of stay for US pediatric mental health visits (2005‐2015). Pediatrics. 2021;147(5):e2020030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. The “patient flow standard” and the 4‐hour recommendation. Jt Comm Perspect. 2013;33(6):1, 3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ethics Committee . The Impact of Boarding Psychiatric Patients on the Emergency Department: Scope, Impact and Proposed Solutions. American College of Emergency Physicians; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guzmán EM, Tezanos KM, Chang BP, et al. Examining the impact of emergency care settings on suicidal patients: a call to action. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;63:9‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kraft CM, Morea P, Teresi B, et al. Characteristics, clinical care, and disposition barriers for mental health patients boarding in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;46:550‐555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nordstrom K, Berlin JS, Nash SS, et al. Boarding of mentally ill patients in emergency departments: American Psychiatric Association resource document. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(5):690‐695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Krass P, Dalton E, Doupnik SK, et al. US pediatric emergency department visits for mental health conditions during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e218533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, et al. Mental health‐related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the covid‐19 pandemic—United States, January 1‐October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675‐1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leyenaar JK, Freyleue SD, Bordogna A, et al. Frequency and duration of boarding for pediatric mental health conditions at acute care hospitals in the US. Jama. 2021;326(22):2326‐2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marquis T, Callas P, Schweitzer N, et al. Characteristics of children boarding in emergency departments for mental health conditions in a rural state. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(8):1024‐1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Richtel M. Hundreds of Suicidal Teens Sleep in Emergency Rooms. Every Night. The New York Times; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vostanis P. Mental health services for children in public care and other vulnerable groups: implications for international collaboration. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;15(4):555‐571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoffmann JA, Stack AM, Monuteaux MC, et al. Factors associated with boarding and length of stay for pediatric mental health emergency visits. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(10):1829‐1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alakeson V, Pande N, Ludwig M. A plan to reduce emergency room ‘boarding’ of psychiatric patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1637‐1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Claudius I, Donofrio JJ, Lam CN, et al. Impact of boarding pediatric psychiatric patients on a medical ward. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):125‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feuer V, Mooneyham GC, Malas NM. Addressing the pediatric mental health crisis in emergency departments in US: findings of a national pediatric boarding consensus panel. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pediatrics AAP . AAP‐AACAP‐CHA Declaration of a National Emergency in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2021.

- 40. Suicide Risk Screening in Healthcare Organizations. The Joint Commission at https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news‐and‐multimedia/blogs/dateline‐tjc/2022/03/suicide‐risk‐screening‐in‐healthcare‐organizations/

- 41. Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, et al. Ask suicide‐screening questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1170‐1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. The Columbia Protocol—Using the Scale.The Columbia Lighthouse Project at https://cssrs.columbia.edu/the‐columbia‐scale‐c‐ssrs/faq/#using‐the‐scale3 on 17 July 2023

- 43. Brent DA, Horowitz LM, Grupp‐Phelan J, et al. Prediction of suicide attempts and suicide‐related events among adolescents seen in emergency departments. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. King CA, Brent D, Grupp‐Phelan J, et al. Prospective development and validation of the computerized adaptive screen for suicidal youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):540‐549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grazier KL, Grupp‐Phelan J, Brent D, et al. The cost of universal suicide risk screening for adolescents in emergency departments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(19):6843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bridge JA, Birmaher B, Brent DA. The case for universal screening for suicidal risk in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2023;151(6):e2022061093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goldstein Grumet J, Boudreaux ED. Universal suicide screening is feasible and necessary to reduce suicide. Psychiatr Serv. 2023;74(1):81‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sarin A, Conners GP, Sullivant S, et al. Academic medical center visits by adolescents preceding emergency department care for suicidal ideation or suicide attempt. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(7):1218‐1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McKinley KW, Rickard KNZ, Latif F, et al. Impact of universal suicide risk screening in a pediatric emergency department: a discrete event simulation approach. Healthc Inform Res. 2022;28(1):25‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lindor RA, Campbell RL, Pines JM, et al. EMTALA and patients with psychiatric emergencies: a review of relevant case law. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(5):439‐444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Terp S, Wang B, Burner E, et al. Civil monetary penalties resulting from violations of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) involving psychiatric emergencies, 2002 to 2018. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(5):470‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hedman LC, Petrila J, Fisher WH, et al. State laws on emergency holds for mental health stabilization. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):529‐535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Critical Crossroads Pediatric Mental Health Care in the Emergency Department: A Care Pathway Resource Toolkit. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Donofrio JJ, Horeczko T, Kaji A, et al. Most routine laboratory testing of pediatric psychiatric patients in the emergency department is not medically necessary. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(5):812‐818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berg JS, Payne AS, Wavra T, et al. Implementation of a medical clearance algorithm for psychiatric emergency patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2023;13(1):66‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cunqueiro A, Durango A, Fein DM, et al. Diagnostic yield of head CT in pediatric emergency department patients with acute psychosis or hallucinations. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(2):240‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Donofrio JJ, Santillanes G, McCammack BD, et al. Clinical utility of screening laboratory tests in pediatric psychiatric patients presenting to the emergency department for medical clearance. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(6):666‐675.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fortu JM, Kim IK, Cooper A, et al. Psychiatric patients in the pediatric emergency department undergoing routine urine toxicology screens for medical clearance: results and use. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(6):387‐392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Santiago LI, Tunik MG, Foltin GL, et al. Children requiring psychiatric consultation in the pediatric emergency department: epidemiology, resource utilization, and complications. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(2):85‐89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Choosing Wisely. American Board of Internal Medicine at https://choosingwisely.org/on 17 July 2023

- 61. Santillanes G, Donofrio JJ, Lam CN, et al. Is medical clearance necessary for pediatric psychiatric patients? J Emerg Med. 2014;46(6):800‐807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dolan MA, Fein JA. Pediatric and adolescent mental health emergencies in the emergency medical services system. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1356‐e1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. “American Academy of Pediatrics” and “American Foundation for Suicide Prevention” . Suicide: Blueprint for Youth Suicide Prevention.

- 64. Shain B. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. SAFE‐T Pocket Card: Suicide Assessment Five‐Step Evaluation and Triage for Clinicians. In: Administration SAaMHS , ed. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Youth ASQ Toolkit. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research‐conducted‐at‐nimh/asq‐toolkit‐materials/youth‐asq‐toolkit#emergency

- 67. Suicide Risk Screening Training: How to Manage Patients at Risk for Suicide. YouTube: National Institute of Mental Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Grupp‐Phelan J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Trends in mental health and chronic condition visits by children presenting for care at U.S. emergency departments. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):55‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wright S, Thompson N, Yadrich D, et al. Using telehealth to assess depression and suicide ideation and provide mental health interventions to groups of chronically ill adolescents and young adults. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44(1):129‐137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fairchild RM, Ferng‐Kuo SF, Rahmouni H, et al. Telehealth increases access to care for children dealing with suicidality, depression, and anxiety in rural emergency departments. Telemed J E Health. 2020;26(11):1353‐1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Gajarawala SN, Pelkowski JN. Telehealth benefits and barriers. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17(2):218‐221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moffat JC. The EMTALA Answer Book—Chapter 5; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Warby R, J. B. EMTALA And Transfers. [Updated 2023 Feb 13]. StatPearls Publishing; StatPearls [Internet]. 2023 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Comprehensive Care Bundle.EMSC Innovation and Improvement Center. at https://emscimprovement.center/state‐organizations/new‐england/new‐england‐behavioral‐health‐toolkit/comprehensive‐care‐bundle/

- 75. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(4):495‐499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kroll J. Use of no‐suicide contracts by psychiatrists in Minnesota. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1684‐1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Range LM, Campbell C, Kovac SH, et al. No‐suicide contracts: an overview and recommendations. Death Stud. 2002;26(1):51‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rozek DC, Tyler H, Fina BA, et al. Suicide intervention practices: what is being used by mental health clinicians and mental health allies? Arch Suicide Res. 2022:1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Garvey KA, Penn JV, Campbell AL, et al. Contracting for safety with patients: clinical practice and forensic implications. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37(3):363‐370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rudd MD, Mandrusiak M, Joiner TE, Jr. The case against no‐suicide contracts: the commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62(2):243‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Bryan CJ, Mintz J, Clemans TA, et al. Effect of crisis response planning vs. contracts for safety on suicide risk in U.S. Army Soldiers: a randomized clinical trial. J Affect Disord. 2017;212:64‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Stanley B, Brown GK. Safety planning intervention: a brief intervention to mitigate suicide risk. Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):256‐264. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Stanley B, Brown GK, Brenner LA, et al. Comparison of the safety planning intervention with follow‐up vs usual care of suicidal patients treated in the emergency department. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):894‐900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Abbott‐Smith S, Ring N, Dougall N, et al. Suicide prevention: what does the evidence show for the effectiveness of safety planning for children and young people?—A systematic scoping review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pettit JW, Buitron V, Green KL. Assessment and management of suicide risk in children and adolescents. Cogn Behav Pract. 2018;25(4):460‐472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stanley‐Brown Safety Plan. Stanley‐Brown Safety Planning Intervention at https://suicidesafetyplan.com/forms/on 18 May 2023

- 87. Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. Jama. 2005;293(6):707‐714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Goyal MK, et al. Firearm‐related injuries and deaths in children and youth. Pediatrics. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pallin R, Barnhorst A. Clinical strategies for reducing firearm suicide. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hunter AA, DiVietro S, Boyer M, et al. The practice of lethal means restriction counseling in US emergency departments to reduce suicide risk: a systematic review of the literature. Inj Epidemiol. 2021;8(Suppl 1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Daigle MS. Suicide prevention through means restriction: assessing the risk of substitution. A critical review and synthesis. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(4):625‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Simon OR, Swann AC, Powell KE, et al. Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2001;32(1 Suppl):49‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Betz ME, Kautzman M, Segal DL, et al. Frequency of lethal means assessment among emergency department patients with a positive suicide risk screen. Psychiatry Res. 2018;260:30‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Mueller KL, Chirumbole D, Naganathan S. Counseling on access to lethal means in the emergency department: a script for improved comfort. Community Ment Health J. 2020;56(7):1366‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Sale E, Hendricks M, Weil V, et al. Counseling on access to lethal means (CALM): an evaluation of a suicide prevention means restriction training program for mental health providers. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(3):293‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bowden CF, True G, Cullen SW, et al. Treating pediatric and geriatric patients at risk of suicide in general emergency departments: perspectives from emergency department clinical leaders. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78(5):628‐636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Billing and Financing Behavioral Health Integration and Collaborative Care University of Washington at https://aims.uw.edu/resources/billing‐financing on 17 May 2023

- 98. Richardson J, Johnson K, DeLisle D, et al. Implementing and Sustaining Zero Suicide: Health Care System Efforts to Prevent Suicide. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE): U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don't patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Adv Psychiatric Treat. 2007;13(6):423‐434. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Children's Health Care Quality Measures. Core Set of Children's Health Care Quality Measures. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- 101. State Readiness to Report Mandatory Core Set Measures. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Hoffmann JA, Krass P, Rodean J, et al. Follow‐up after pediatric mental health emergency visits. Pediatrics. 2023;151(3):e2022057383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Sorter M, Stark LJ, Glauser T, et al. Addressing the pediatric mental health crisis: moving from a reactive to a proactive system of care. J Pediatr. 2023:113479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: National Guidelines for Child and Youth Behavioral Health Crisis Care. Publication No. PEP22‐01‐02‐001 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2022.

- 105. Schober M, Harburger DSS, et al. A Safe Place to Be: Crisis Stabilization Services and Other Supports for Children and Youth. Technical Assistance Collaborative Paper No. 4. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 106. National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care: Best Practice Toolkit . Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Manley E, Schober M, Sulzbach D, et al. Mobile Response and Stabilization Best Practices. [Fact Sheet]. In: Implementatio IfI, ed; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Fendrich M, Ives M, Kurz B, et al. Impact of mobile crisis services on emergency department use among youths with behavioral health service needs. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(10):881‐887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Guo S, Biegel DE, Johnsen JA, et al. Assessing the impact of community‐based mobile crisis services on preventing hospitalization. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(2):223‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Oblath R, Herrera CN, Were LPO, et al. Long‐term trends in psychiatric emergency services delivered by the Boston Emergency Services team. Community Ment Health J. 2023;59(2):370‐380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Anderson K, Goldsmith LP, Lomani J, et al. Short‐stay crisis units for mental health patients on crisis care pathways: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BJPsych Open. 2022;8(4):e144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]