Abstract

Background

Twin registries and cohorts face numerous challenges, including significant resource allocation, twins’ recruitment and retention. This study aimed to assess expert feedback on a proposed pragmatic idea for launching a continuous health promotion and prevention programme (HPPP) to establish and maintain twin cohorts.

Design

A qualitative study incorporating an inductive thematic analysis.

Setting

Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Participants

Researchers with expertise in twin studies participated in our study.

Analysis and design

Expert opinions were gathered through focus group discussions (FGDs). Thematic analysis was employed to analyse the findings and develop a model for designing a comprehensive, long-term health promotion programme using ATLAS.ti software. Additionally, a standardised framework was developed to represent the conceptual model of the twin HPPP.

Results

Eight FGDs were conducted, involving 16 experts. Thematic analysis identified eight themes and seven subthemes that encompassed the critical aspects of a continuous monitoring programme for twin health. Based on these identified themes, a conceptual framework was developed for the implementation of an HPPP tailored for twins.

Conclusion

This study presented the initial endeavour to establish a comprehensive and practical solution in the form of a continuous HPPP designed to tackle the obstacles of twins’ cohorts.

Keywords: Health Services Accessibility, Primary Health Care, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, PUBLIC HEALTH, Health policy

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

A qualitative study design and focus group discussions offer a valuable opportunity for researchers to draw out new thoughts, insights, and ideas from participants.

The thematic analysis method was employed to gather experts’ opinions about the prerequisites and requirements for creating this programme, drawing on their experiences.

This study examines the prerequisites and key characteristics of a desired programme from the perspective of these experts.

Challenges and perceived benefits of our program from the viewpoints of twins and their families have not been examined in this phase of this study.

Introduction

Twins hold a special place in medical science because of their unique genetic makeup. They offer the chance to study the impact of behaviour and genetics on disease, ageing, traits and response to medical treatments while controlling for genetic and early environmental confounding factors.1 2 Conducting such studies requires collecting data from a large number of twins, which has led to the emergence of twin registries as an effective method for recruiting a large number of twins.3 4 Despite their potential, twin registries often face common challenges such as high costs associated with registration, logistics and the difficulties in ensuring the recruitment and continuous participation of twins, which can hinder their objectives.5–13 To address these challenges, innovative solutions are needed to motivate twins, overcome these challenges and ensure their continued engagement. Given their suitability for conducting large studies with multiple exposures and outcomes,14 some prospective twin cohort studies have been implemented.11 14–17

A challenge in creating cohort studies is the long-time gap between measuring risk factors and health outcomes, particularly for many non-communicable diseases that can take years or even decades to develop.18 According to Abshire et al, offering participants a health promotion programme that benefits them and their families can help maintain their involvement in long-term studies.19 Health promotion and disease prevention are also important goals of the health system in our era, as they can help reduce the risk of getting chronic diseases and other health problems.20 21

Given these considerations, a Twin Health Promotion and Prevention Programme (HPPP) that is aligned with Sustainable Development Goal 3 for global health goals could be considered as a practical solution to improve twin health and address the common challenges of cohort studies.22 By tracking the general health status over time, a cohort may be able to identify various risk factors, including diet, physical activity, consumption habits, underlying diseases and genetic factors.23

This study aims to evaluate expert feedback on a proposed pragmatic idea for leveraging HPPP to increase the recruitment and retention of school-aged twins into a prospective cohort. Our study has additional objectives, including the design of a conceptual framework for the planning of a long-term twin general health promotion programme. This proposed framework integrates expert perspectives on the necessary prerequisites, infrastructure and data collection tools for the implementation of a twin HPPP.

The history of establishing the Persian Twin Registry

Establishing the Persian Twin Registry began with a literature review and expert consensus in 2018, which highlighted the necessity of such a registry. A systematic review in 2021 examined the challenges, information registration methods and best practices for setting up twin registries worldwide. Based on the findings, a qualitative study published a framework for creating a twin registry, including the ideal model for registering twin information, suitable age groups and data entry methods.6

Following approval from the Ministry of Health and the formation of a specialised steering committee, the population-based Persian Twin Registry was established in Iran between 2018 and 2022, covering three age groups: infants, school aged and adults. Its main purpose was to facilitate twin studies and establish a large data warehouse of twin information for further research, covering both identical twins and non-identical twins on a country-wide level. Similar to other countries, developing the twin registry at the national level has encountered various challenges in Iran. These challenges include high costs associated with data entry, non-cooperation of twins and their families, tracing twins, a shortage of skilled human resources, loss of follow-up and the need for infrastructure to support a twin health follow-up programme.6 24–26 More detailed information is available in the researchers’ recent paper.27

Our experience with the twin follow-up programme within the Persian Twin Registry showed that one of the most significant obstacles was recruiting and retaining twins in a continuous follow-up programme. This may be due to participants having direct access to specialised care in Iran, which allows them to choose their healthcare provider, potentially decreasing their motivation to participate in regular twin follow-up programmes.6 Therefore, it seems prudent to consider alternative ways to motivate twins to participate in such programmes.

Methodology

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Health Research checklist was followed in our study.28

Study design and samples

In this qualitative study, experts in twin studies were invited to face-to-face focus group discussions (FGDs) to gather their insights on the practical implementation of a long-term twin public health promotion programme to address twin registry problems. The purposive sampling method was employed to select experts who had experience cooperating in setting up the Persian Twin Registry or those working in the field of twin studies. Informed consent was obtained from all experts/participants who participated in this study.

One of the researchers (MG), who has expertise in conducting qualitative studies, invited all experts by telephone to schedule sessions. At the first session, information related to the results of similar studies, the results obtained from the first stage of the twin registry development in Iran, and the information regarding problems and challenges that arose from the previous experience of our twin registry implementation were presented by the authors. The idea of implementing a long-term health promotion and disease prevention programme for Persian twins to enhance their recruitment and retention was discussed in the first and second sessions. Experts were asked to think about this possible solution and to provide feedback on it.

Face-to-face focus group interviews were conducted from 25 February 2021 to 30 July 2021 in Tehran, Iran. Each session lasted 45–60 min and the total number of FGDs was determined based on the principle of saturation. Data saturation occurred when no new viewpoints were available.

The expert panel included four internists, four paediatricians, three psychiatrists, one prevention and social medicine specialist, one public health specialist, one epidemiologist, one clinical pharmacist, and one medical informatics specialist. All of them were from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences and were interested in the twin health promotion programme. The first session explained the study purpose, the proposed solution and the previous programme challenges. Each subsequent session discussed one or more features of the proposed programme.

Conducting interviews and focus groups

Focus groups were led by MG, who had no prior contact with participants. All discussions were conducted in the Persian language, the mother tongue of the participants. The first 5 min of the sessions was devoted to introducing the objectives of the study and the main concerns to be discussed. An interview guide consisting of open-ended questions was used to gather data on pertinent topics (online supplemental appendix 1). We began our discussions by exploring healthcare professionals’ perceptions of how twins will be recruited and how they will be followed. Throughout each FG session, we encouraged every member to share their ideas for an open discussion. As a result, we were able to formulate a conceptual model that serves as an interpretation of the healthcare professionals’ ideas.

bmjopen-2023-080443supp001.pdf (72.1KB, pdf)

The exploratory questions aimed to delve into the participants’ thoughts, views and perceptions regarding different aspects of prevention and health promotion programmes, as well as defining the proper target group of twins. Subsequently, stimulating questions were employed to encourage participants to elaborate on the meaning and nature of the different subjects. All viewpoints were transcribed by two researchers. The narrative summary of each session was written to document the main idea and thoughts of experts.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke’s approach29 was employed as the most appropriate method to extract the main concepts from the transcription in our exploratory survey. This approach is beneficial for finding people’s viewpoints, opinions, knowledge, experiences or values from a set of qualitative data. The process of identifying themes was conducted iteratively by two researchers.

All transcriptions were imported into ATLAS.ti software for coding and mapping related ideas.30 The transcriptions were read multiple times to extract the main concepts and were translated into English for codification. The first step was to review all the collected information and views to create an overview before starting the thematic analysis. In the initial coding stage, phrases and sentences were highlighted and labelled with brief labels or ‘codes’ to describe their content (online supplemental appendix figure A1). Next, potential themes were extracted from groups of codes after identifying the main patterns. The theme is usually broader than the code and most of the time is created from the combination of several codes. Ambiguous or unrelated codes were removed at this stage. After ensuring that our themes were a suitable and accurate representation of the data, we defined the final themes and subthemes to formulate exactly what we meant. Similar themes were merged to create meaningful themes.31

bmjopen-2023-080443supp002.pdf (258.6KB, pdf)

Mapping concepts and designing the conceptual model

An initial conceptual model was developed in an iterative process based on the identified key themes and subthemes. The model was refined and redesigned to achieve the optimal framework. Subsequently, researchers created a proposed pathway to explain the various stages of developing the twin health promotion programme. Two FGDs were conducted with the same experts who participated in the previous discussions to validate the developed models and provide feedback on them. This step aimed to ensure that the models accurately represented the insights and perspectives of the healthcare professionals.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in this survey.

Results

Expert profile

Eight FGDs involving 16 experts were conducted. All 16 experts attended in all FGDs. The demographic characteristics of participants are presented in table 1. The FGDs were conducted in Imam Khomeini Hospital, with each session lasting for approximately 40 min.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the expert panel

| Data | Frequency | Percentage |

| Specialist | ||

| Internist | 4 | 25.00 |

| Paediatrician | 4 | 25.00 |

| Psychiatrist | 3 | 18.75 |

| Preventive and community medicine specialist | 1 | 6.25 |

| Public health specialist | 1 | 6.25 |

| Epidemiologist | 1 | 6.25 |

| Pharmacotherapist | 1 | 6.25 |

| Medical informatician | 1 | 6.25 |

| Age | ||

| 30–45 | 7 | 43.75 |

| 45–60 | 5 | 31.25 |

| >60 | 4 | 25.00 |

| Experience | ||

| <5 years | 6 | 37.50 |

| 5–10 years | 4 | 25.00 |

| >10 years | 6 | 37.50 |

Conceptualisation of gathered opinions

Through thematic analysis, eight themes and seven subthemes were identified concerning the main features of an alternative solution to address the obstacles of twin registration. The treemap of extracted themes is depicted in online supplemental figure A2. Themes and subthemes with examples of expert quotes are summarised in online supplemental appendix table A1.

bmjopen-2023-080443supp003.pdf (147.1KB, pdf)

Theme I: perceived benefits of continuous twin health promotion and follow-up programmes

During the discussions, the majority of participants commented that implementing a twin registry alone is insufficient to achieve the desired objectives. Two mentioned problems were recruiting twins and the high cost of data entry. As a result of discussions, most experts agreed that a continuous HPPP that provides benefits to participants and their families is essential for the continuousness of twin studies.

The experts concluded that a continuous twin health monitoring centre should be established to provide specialised health promotion programmes for twins, thereby motivating their participation. This programme aims to facilitate early diagnosis in the target group and promote their overall health, thereby encouraging them to participate in continuous health screening programmes.

Theme II: target group and their facilitators

Non-response and the low proportion of eligible participants agreeing to participate in the study were discussed as the foremost challenges in implementing a national twin registry, according to previous experiences. Retaining participants and selecting an appropriate target group are also important considerations.

Most experts stated that their experiences showed that recruiting school-aged twins could enhance the proportion of eligible participants. In addition, school health experts (school nurses) play a crucial role as recruitment facilitators in school-aged twins. According to a previous study, there are approximately 189 738 twin students in Iran and 5642 twin students in Tehran.27 Similar studies have shown that schools can help children and adolescents develop healthy habits that will also benefit their families, friends and communities. That is why the WHO started the Health Promotion School (HPS) approach in 1995.32 Therefore, school-aged twins were chosen as the target group for the following reasons:

Prevention and promotion programmes are more critical for children and adolescents due to several psychiatric and medical issues associated with rapid growth rate and peripubertal issues.

Most twins in this age group live in similar environments (same family and schools), allowing for the examination of genetics and microenvironmental factors, such as the effect of different friends, food habits and social interests.

Schools and parents can facilitate twins’ participation.

Theme III: enhancing twin recruitment, participation and motivation factors

Motivating participants to remain engaged in long-term population-based studies was a widely discussed issue. Researchers suggested that an ongoing HPPP for twins could encourage them to participate willingly in the cohort.

To address the challenge of motivating twins and maintaining their scheduled visits, various solutions were proposed and discussed by the group. The following are some of the most important suggested solutions that were considered:

Providing HPPP with insurance coverage and governmental tariffs.

Building confidence among twins and their families regarding the high quality of healthcare services and the expertise of the medical team.

Ensuring prompt access to specialists and referrals when needed.

Providing an opportunity for general health assessment of twins’ parents and other companions.

The success of HPPP in recruiting twins depends on the health literacy of twins and their parents and ensuring them that high-quality services without exceeding charges are available. Parent education, including in-person meetings, calls and educational brochures about the programme’s structure and goals, should be considered to motivate twins to participate in this programme. In further studies, we will also take into account the views of parents regarding the perceived needs of school-aged twins. By engaging mothers in the study, we aim to progress towards implementing a patient-centred system with previsit planning in the future.33

Theme IV: structure, content and overall views on the programme

After reaching a consensus among healthcare professionals regarding the potential usefulness of the programme for school-aged twins, the discussion centred on the main features and characteristics of the suggested programme. This subcategory refers to the requirement of having a comprehensive plan necessary to implement health promotion goals.

Subtheme 4.1: providing a physical environment and specific time

The main concern was the physical access and providing a safe and permanent place for regular visits of clients, as well as a reliable setting to use the available opportunities. Providing physical infrastructure could ensure participants’ access to specialists and offer specialised care and consultations when needed.

I believed that establishment of a permanent health promotion and prevention clinic for school-aged twins developed a relationship of trust with the clinicians, who became a reference person for the twins for long-term follow-up.

Subtheme 4.2: service provider’s credibility and participant trust

Families typically prefer services offered by organisations with public credibility and effective monitoring systems. Well-known organisations like academic centres can provide robust support and take professional responsibility for their services, which instils a higher level of trust. Some experts have stated that due to the organisation’s trustworthiness, experience and professionalism, there is no need for additional research on the content of the services for families.

Subtheme 4.3: interprofessional collaboration and multidisciplinary clinic

All experts agreed that such collaboration would enable professionals to assess the twins at different points in time and work together to manage their different physical and psychological aspects. This allows professionals to make early diagnoses of diseases, identify risk factors and reduce the risk of patients being lost to follow-up.

Subtheme 4.4: standardisation of follow-up process and data collection protocol

In this area, the experts agreed that the cooperation of the Ministry of Education will provide the possibility of an easy invitation to the HPPP programme through schools or direct contact with the twins. However, experts agreed that a standardised data collection protocol with ethical considerations is needed. In this area, it was decided that clinical examinations and tests would be performed only if necessary to diagnose a disease or health problem based on a doctor’s diagnosis.

Subtheme 4.5: outcome measures and impacts

Preventive visits provide an opportunity for professionals to help twins and their families identify health concerns and facilitate early diagnosis of common school-age illnesses. It is generally assumed that twin students share similar living and educational environments, which helps minimise the influence of multiple confounding factors. However, researchers interested in using this platform to investigate various research topics must clearly define the conditions for entry and exit from the study, as well as establish protocols for follow-up and evaluation. Drawing from preliminary results, mental/neurological disorders, vision, and hearing problems, musculoskeletal disorders, asthma, and allergies are the most prevalent conditions during school-age years.

Theme V: data collection and twins’ registration

Subtheme 5.1: data gathering, data sources and data collection tools

Experts emphasised the importance of identifying reliable data sources and selecting appropriate tools for data collection as crucial prerequisites for conducting such a study. Drawing from past experiences in the development of twin registry projects, experts have highlighted the crucial role played by the Ministry of Education and schools as collaborators in obtaining essential information on twins and recruiting participants.

Experts suggest using two types of questionnaires for the collection of twin data: e Zygosity and a questionnaire to evaluate general physical and mental health. The ‘Pea-in-Pods’ questionnaire is considered the most reliable for determining zygosity.4 The GHQ and a 25-question questionnaire are used to evaluate the general mental and physical health of twins,34 35 respectively. These questionnaires will aid in structured information gathering, while the twin health medical record remains the primary source of health information.

Once informed consent is obtained, a twin health record will be created to serve as an information source for twin pairs. This record will include their health information and related clinical data collected through regular visits and participation in the ongoing twin health monitoring programme.

Subtheme 5.2: data security and confidentiality

Ensuring data security is crucial in the field of data recording and collection. Experts suggest that transparency about data access and exchange can increase participants' willingness to share information. In this study, twins will only be included if their parents have signed a written consent form. To ensure data security, the following policies and practices should be adopted:

Authorisation policies that specify who has access to data and what data they can access.

Authentication policies that verify the identity of users accessing the data.

Role-based access policies that limit data access based on users’ roles and responsibilities.

System access logs that record all data access and changes.

Storing data in a secure relational database such as SQL.

Deidentification of personal data.

For proper management and storage of research data, some strategies include using secure storage media, password protection and treating consent forms as confidential documents.

By adopting these policies and practices, data security can be ensured, and participants can be assured that their data is protected.

Theme VI: infrastructure for enhanced data accessibility

In summary, experts recommend a reliable web-based platform for recording data. They suggest storing all health data of the twins in a relational database through a continuous HPPP, allowing for the comparison of information of multiple pairs with each other and with their family’s medical records. An electronic medical record should be created for each pair of twins individually for follow-up, enabling doctors to record twin information in real time during clinic visits. Our previous experiences with twin data entry have shown that using an electronic questionnaire to collect information alone cannot provide us with the necessary reports. Additionally, the high cost of data entry through paper-based questionnaires or electronic forms in a long-term study was another problem. The proposed structure for recording twin data has been investigated in our previous article.6

All follow-up data will be stored in electronic medical records, allowing easy referral of twin pairs to appropriate specialists in case of a diagnosed problem. By recording twin information and tracking the health of the twins and their families, a valuable database for HPPP and further follow-up programmes for twins will be created. The database can also serve as a data source for academic researchers interested in twin studies.

Theme VII: health professionals’ views on challenges, barriers and solutions

The discussion initially revolved around the experiences of experts during the previous phase of the project, focusing on the development of the twin registry, the challenges encountered, associated obstacles and proposed solutions. Moreover, the potential impact of implementing the twin HPPP on addressing the existing challenges was thoroughly discussed (table 2). One of the most significant challenges of establishing a national twin registry is the problems related to the high costs of data collection and human resources challenges.

Table 2.

Challenges discussed in FGDs

| Challenges | Main domains | Some suggested solutions |

| High costs | Data entry | The long-term HPPP facilitates the collection of twin health information using an electronic health record for twins. |

| Labour staffing | Physicians and interested researchers can do some work. | |

| Need to the permanent clinic | Since the long-term health monitoring and prevention programme will be carried out with the support of a university centre and with the cooperation of university professors, the university clinic and government support can be used. | |

| Visits | Since the HPPP for health monitoring can be done regularly with government support and with the cooperation of interested professionals, it can reduce the costs of visiting the twins. | |

| Research bias | Loss to follow-up | Participants' direct access to specialised care to motivate twins. |

| Retention of participants and lack of motivation | To remain in the study, it is necessary to consider a specific age group and facilitators to recruit twins in this programme. | |

| Volunteer bias | Setting up programmes to prevent and promote the health of twins with low government visit costs not only improves the physical and mental health of twins but also encourages twin families to participate in such programmes. | |

| Exclusion or attrition bias |

|

|

| Infrastructure | Need for infrastructure to support a twin health follow-up programme | Considering the design of a structured model and framework at the beginning of the study with the cooperation of experts, this problem can be overcome. |

| Need a platform to enhance data accessibility | Designing and developing electronic health record. | |

| Resource limitation | Time | Considering a short period (1 year) for referring and initial evaluation of twins and considering a minimum follow-up time of 3–4 years considering the puberty and growth of school-aged twins. |

| Trained staff and logistics | The same personnel of the long-term health monitoring and prevention programme can be used to collect the health information of the twins and the medical records of the clients. |

FGDs, focus group discussions; HPPP, health promotion and prevention programme.

Theme VIII: governance and leadership

During a discussion among experts in the field, they explored ways to provide the most efficient and effective executive structure, including appropriate financial resources, dividing tasks and responsibilities, and having strong organisational leadership to manage the programme. They suggested that a multidisciplinary structure of experts from different fields in medical sciences, supported by an academic structure, can be effective.

To fully comprehend how organizations are structured and function, it is important to understand their components and their interrelationships.

The success of an organization relies on the interaction and interdependence between its subsystems, as well as the synergy created by these interactions.

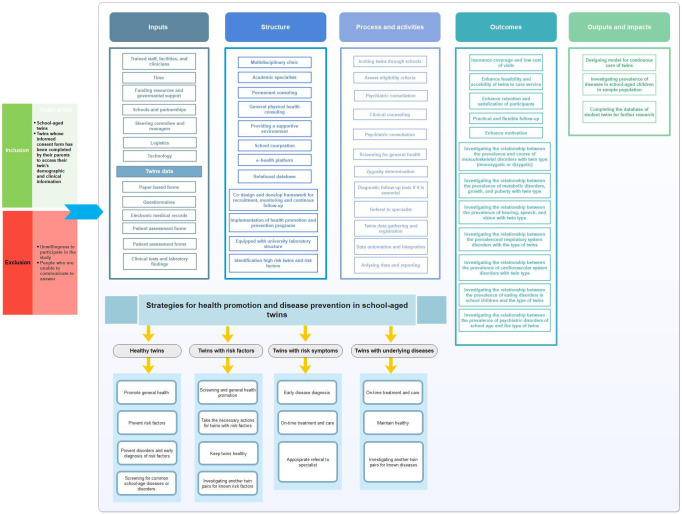

The conceptual model of HPPP for Persian twins by integrating extracted themes

Experts recommended setting up the HPPP cohort as a suitable solution for monitoring the twin health with low government visit costs. The conceptual model presented in figure 1 illustrates the characteristics of the desired programme based on the input-process-output (IPO) model which is commonly used in health studies to present a comprehensive process and causal model of the programme.36–39 Our model combines experts’ opinions and themes extracted from FGDs. The IPO model is commonly used in health studies to present a more comprehensive process and causal model of the programme.36–38 It explains the features, structure, prerequisites and infrastructure of such systems. Our proposed framework is planned based on a concept that describes the inter-professional nature of our programme. The framework was designed using the themes derived from FGDs, the empirical literature on factors and measures of interprofessional collaboration in HPPP and previous experiences. The HPPP programme incorporates all the main aspects of the IPO model, including inputs, structure, process, outcome and impacts. It also shows how prevention and health promotion strategies are integrated into our framework for different situations.

Figure 1.

The conceptual model of the twin health prevention and promotion programme.

The qualitative analysis revealed that the prospective cohort design in large populations starting in school-aged life is essential for understanding the origins of school-aged twin health. The study focuses on common non-communicable diseases and disorders in school-age twins, with the involvement of university professors. Figure 1 illustrates how this strategy helps promote health and prevent disease in twins. The evaluation of the other twin is medically indicated in case of any disorder in one twin, providing valuable information about the role of environment and genetics. The general characteristics of a continuous HPPP cohort study are summarised in table 3, which provides important insights into the initiation of primary prevention services and health promotion in twins.

Table 3.

The general characteristics of a continuous HPPP cohort study

| Overall objectives | This study aims to investigate the prevalence of various physical disorders, including musculoskeletal, metabolic, growth and maturation, nutritional, respiratory, cardiovascular, psychiatric and other disorders, among school twins. Additionally, the study seeks to examine the relationship between these disorders and the type of twins (monozygotic or dizygotic). To achieve these objectives, the study will analyse data from a sample of school twins. The prevalence of each disorder will be determined, and statistical analyses will be conducted to investigate the relationship between the disorders and twin types. Overall, this study aims to contribute to our understanding of the prevalence and relationships between various physical and mental disorders among school-aged twins, which could have implications for the prevention and treatment of these disorders. |

| Study design | Prospective cohort study |

| Target population | Monozygotic and/or dizygotic in school-aged age twins |

| Ethical consideration |

|

| Data storage (including access and confidentiality) | Providing a secure database to protect the database from unauthorised disclosure applying the processes of authentication, authorisation Role-based access control to provide proper access permissions Anonymise the information for analysis Using non-disclosure agreements |

| Selection and recruitment | Voluntary |

| Setting | National level |

| Consent to participate | Written consent from participants |

| Plan for data analysis | Various statistical tests will be used to analyse the data collected in this study. Bivariate data will be compared using tests such as t-tests, χ2 tests and non-parametric tests, depending on the distribution and type of the data. Multivariate analyses will also be conducted to examine confounding factors. As this is a long-term cohort study and the objectives may evolve, the specific statistical tests used for data analysis will be determined in consultation with statisticians. However, some of the most commonly used statistical tests in twin studies include heritability analysis, twin modelling, structural equation modelling and genome-wide association studies. Overall, the statistical tests used in this study will depend on the type of data collected and the research objectives. |

| Collaborators | Schools, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Education, |

HPPP, health promotion and prevention programme.

During this phase, we will recruit school-aged twins residing in Tehran. It is worth noting that a national hospital-based newborn twin registry is available in Iran too.40 Given the current resource limitations, we plan to follow our school-aged twins for a minimum of 4 years. However, many twins are expected to continue their follow-ups with our medical team for health-related concerns due to established trust between them.

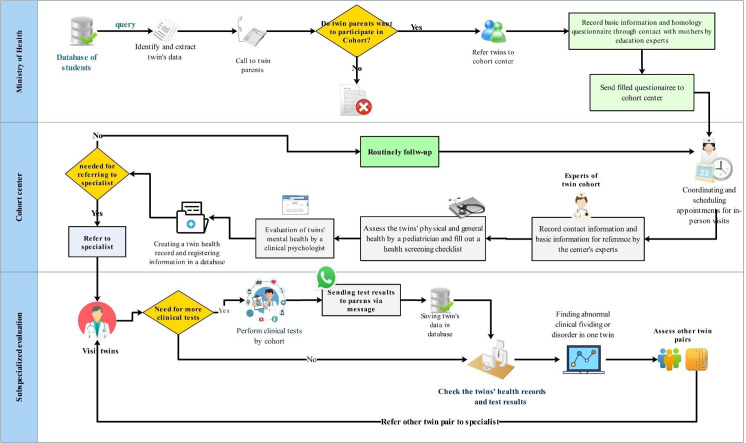

Designing the standard pathway to develop a twin’s health promotion programme based on the results of the thematic analysis

Based on the results of the thematic analysis, we have developed a standard pathway for twin recruitment, as depicted in figure 2. The model aims to provide a clear workflow for the twin follow-up process. The summary of the steps involved in our programme is detailed in online supplemental appendix table A2.

Figure 2.

Schematic model for follow-up programme in a school-aged health promotion programme.

By adhering to this pathway, researchers and healthcare professionals can effectively monitor the health and well-being of twins and provide appropriate care and interventions as needed.

Discussion

To address the challenges encountered by twin registries worldwide and highlighted in our study,5 41–43 this qualitative study explored the perspectives of experts to provide an appropriate solution for common twin cohort challenges. As a result, a continuous HPPP specifically for school-aged twins is proposed as a pragmatic plan. Our findings suggest that, with the right structure, this programme can be satisfactory for both twins and researchers.

The first national twin registry was established in 2018, with a focus on the characteristics of 5642 student twin pairs in Tehran.27 This registry had two primary objectives to determine the prevalence of various physical and mental disorders among twins and to examine the relationship between these disorders and the type of twins (monozygotic or dizygotic). The current intervention, the HPPP, is distinct from existing registry initiatives in several ways. While registry initiatives primarily focused on establishing a national twin registry for interested researchers, Twin’s HPPP aims to address unique challenges faced by twin registries, such as recruitment, retention and data collection, by simultaneously promoting the health of twins.

To address the shortage of skilled human resources, the registry plans to use existing clinical staff within the healthcare setting. By establishing a dedicated health monitoring clinic for twins, the HPPP aims to leverage the capacity and expertise of healthcare professionals already working in clinical environments. This approach not only optimises the use of available resources but also nurtures a collaborative environment among healthcare providers, researchers and twins, ultimately contributing to improved twin health and well-being.

Our project has both fundamental (assessing genetic and environmental factors in various diseases) and operational aspects. By identifying and managing various physical and mental diseases and disorders in student twins at an early stage, this programme aims to promote health and improve prognosis in these vulnerable ages.

Considering a wide age range of twin age groups can be a significant obstacle to implementing twin registries.6 Schools can play a crucial role in improving students’ well-being, as they spend a considerable amount of time there. By promoting their health, schools can enhance the quality of life of children and teenagers. School staff, such as school health experts (school nurses), could serve as recruitment facilitators to improve participant retention.27 44 Therefore, school-aged twins are considered a desirable group of twins in registries. School-based health promotion interventions (HPIs) have been widely used to promote physical and mental health in school children.45 46 Implementing WHO-recommended HPSs can integrate and coordinate a more efficient system for the healthy child development of students affected by HPIs.47–49 Well-implemented HPIs or HPSs can improve the overall health and well-being of students, mitigate risk factors, and manage detected physical and mental disorders.50

This study proposes a framework that includes the general characteristics, processes and features of a programme to address issues of twin recruitment and data collection in the Persian Twin Registry using qualitative analysis. Similar studies have employed expert opinions and past experiences to develop specific conceptual frameworks for health monitoring systems.51 We used thematic analysis52 to conceptualise our HPPP as a twins’ cohort, ensuring adherence to reflexivity, rigour and quality principles essential in all qualitative research methods.

The cohort study design facilitates early disorder detection, incentivising twins and their families to participate in regular visits as part of a long-term programme. Implementing twin HPPPs with low visit expenses not only enhances twins’ physical and mental well-being but also can encourage active participation, addressing retention bias.16 Furthermore, establishing a dedicated health monitoring clinic specifically for twins could simplify access to reliable public health services for these families.

An attempt has been made to comprehensively cover various aspects of this programme. However, as this is an evolving area, updates will most likely be necessary over time. The framework is designed as a guide for the design and implementation of twin health programmes, providing flexibility and allowing for adaptation to different potential use cases.

To evaluate the programme’s acceptability, a health prevention and promotion clinic for school-aged twins was established in Tehran, Iran, by collaboration of clinical specialists, psychiatrists and psychologists of Tehran University of Medical Sciences with an interest in twin studies. Moreover, Tehran is home to approximately one-fifth of Persian twins. All Iranian twin pairs from school-aged residing in Iran and aged 6 or above will be included in the study in further studies on obtaining their consent. We recruit twins from schools to enter our programme. We expect that after the initial recruitment and visiting by our physicians, these twins will continue their upcoming health visits with the same physicians for a longer time because of the established twins–physician relationship.

This project encountered several limitations. First, the small number of experts in the twin study field led to a non-random sampling method. Second, given the inherent limitations of qualitative research generalisability, this study focused on the public health field. However, it has the potential to be expanded to a broader context in the future. To address these limitations, the feasibility of the proposed model will be investigated in the twin clinic based on the proposed framework in further studies.

A critical limitation is the exclusion of potential participants (twins) from the study. Patient and participant involvement engagement activities are effective strategies for recruiting participants or understanding considerations relevant to recruitment.53 Thus, this study only investigates experts’ opinions on the characteristics of such a programme in the first phase. Collecting the opinions of the participants will be pursued in subsequent studies.

Conclusion

The framework is designed to highlight the key factors that could be considered when developing a longitudinal cohort study and establishing the HPPP for Persian Twins. By providing a comprehensive programme, it aims to overcome challenges such as tracking twins’ health, encouraging twins to collaborate with clinicians, and reducing the costs associated with twin study programmes. This framework can serve as a valuable resource for researchers seeking to develop similar programmes, offering a cost-effective solution for studying twins and their health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to all participating professionals.

Footnotes

Contributors: HA and MG are the guarantors of this study. MG and HA contributed to the conception and development of the study design, data analysis and interpretation of data. MG, HA, NK-R and FS prepared focus group question guides, conducted the focus groups, analysed the resulting transcripts and coded data. MG, HA, MD, NK-R and FS validated coding structure and analysis. MG, HA, MD, NK-R and FS conducted the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the last version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and the research was approved by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.128). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Twito L, Knafo-Noam A. Beyond culture and the family: evidence from twin studies on the genetic and environmental contribution to values. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2020;112:135–43. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlin JB, Gurrin LC, Sterne JA, et al. Regression models for twin studies: a critical review. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1089–99. 10.1093/ije/dyi153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nikolašević Ž, Dinić BM, Smederevac S, et al. Common genetic basis of the five factor model facets and intelligence: A twin study. Personality and Individual Differences 2021;175:110682. 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman NP, Hatoum AS, Gustavson DE, et al. Executive functions and Impulsivity are genetically distinct and independently predict psychopathology: results from two adult twin studies. Clin Psychol Sci 2020;8:519–38. 10.1177/2167702619898814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laugesen K, Ludvigsson JF, Schmidt M, et al. Nordic health Registry-based research: a review of health care systems and key registries. Clin Epidemiol 2021;13:533–54. 10.2147/CLEP.S314959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abtahi H, Gholamzadeh M, Shahmoradi L, et al. An information-based framework for development national twin Registry: Scoping review and focus group discussion. Health Planning & Management 2021;36:1423–44. 10.1002/hpm.3256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mulder DS, Spicer J. Registry-based medical research: data dredging or value building to quality of care. Ann Thorac Surg 2019;108:274–82. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy K, Lam J, Cutler T, et al. Scurrah KJ: twins research Australia: a new paradigm for driving twin research. Twin Res Hum Genet 2019;22:438–45. 10.1017/thg.2019.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen DA, Larsen LA, Nygaard M, et al. The Danish twin Registry: an updated overview. Twin Res Hum Genet 2019;22:499–507. 10.1017/thg.2019.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dongen J, Gordon SD, McRae AF, et al. Identical twins carry a persistent epigenetic signature of early genome programming. Nat Commun 2021;12:5618. 10.1038/s41467-021-25583-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verdi S, Abbasian G, Bowyer RCE, et al. Twinsuk: the UK adult twin Registry update. Twin Res Hum Genet 2019;22:523–9. 10.1017/thg.2019.65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chulada PC, Corey LA, Vannappagari V, et al. The feasibility of creating a population-based national twin Registry in the United States. Twin Res Hum Genet 2006;9:919–26. 10.1375/183242706779462705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strachan E, Hunt C, Afari N, et al. University of Washington twin Registry: poised for the next generation of twin research. Twin Res Hum Genet 2013;16:455–62. 10.1017/thg.2012.124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaprio J, Boomsma DI. Cohorts. Twin Res Hum Genet 2020;23:114–5. 10.1017/thg.2020.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbert A, Abel GA, Winters S, et al. Cancer diagnoses after emergency GP referral or A&Amp;E attendance in England: determinants and time trends in routes to diagnosis data, 2006–2015. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e724–30. 10.3399/bjgp19X705473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahrens W, Jöckel KH. The benefit of large-scale cohort studies for health research: the example of the German national cohort. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2015;58:813–21. 10.1007/s00103-015-2182-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaprio J. The Finnish twin cohort study: an update. Twin Res Hum Genet 2013;16:157–62. 10.1017/thg.2012.142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Euser AM, Zoccali C, Jager KJ, et al. Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clin Pract 2009;113:c214–7. 10.1159/000235241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abshire M, Dinglas VD, Cajita MIA, et al. Participant retention practices in longitudinal clinical research studies with high retention rates. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:30. 10.1186/s12874-017-0310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson SF, Perkins F, Khandor E, et al. Integrated health promotion strategies: a contribution to tackling current and future health challenges. Health Promot Int 2006;21 Suppl 1:75–83. 10.1093/heapro/dal054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang K-C, Nutbeam D, Kong L, et al. Building capacity for health promotion—a case study from China. Health Promot Int 2005;20:285–95. 10.1093/heapro/dai003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chotchoungchatchai S, Marshall AI, Witthayapipopsakul W, et al. Primary health care and sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ 2020;98:792–800. 10.2471/BLT.19.245613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thuesen BH, Cerqueira C, Aadahl M, et al. Cohort profile: the Health2006 cohort research centre for prevention and health. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:568–75. 10.1093/ije/dyt009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhar R, Rana S, Srivastava TP, et al. India’s opportunities and challenges in establishing a twin Registry: an unexplored human resource for the world’s second-most populous nation. Twin Res Hum Genet 2022;25:156–64. 10.1017/thg.2022.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumathipala A, Siribaddana SH, Abeysingha NMR, et al. Challenges in recruiting older twins for the Sri Lankan twin Registry. Twin Res 2003;6:67–71. 10.1375/136905203762687924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buchwald D, Kaprio J, Hopper JL, et al. International network of twin registries (INTR): building a platform for International collaboration. Twin Res Hum Genet 2014;17:574–7. 10.1017/thg.2014.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abtahi H, Gholamzadeh M, Baharii R. Iranian school-aged twin Registry: preliminary reports and project progress. BMC Pediatr 2023;23:71. 10.1186/s12887-023-03865-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soratto J, Pires D de, Friese S. Thematic content analysis using ATLAS.Ti software: potentialities for Researchs in health. Rev Bras Enferm 2020;73:S0034-71672020000300403. 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders CH, Sierpe A, von Plessen C, et al. Practical thematic analysis: a guide for Multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis. BMJ 2023;381:e074256. 10.1136/bmj-2022-074256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, Preetha G. Preetha G: health promotion: an effective tool for global health. Indian J Community Med 2012;37:5–12. 10.4103/0970-0218.94009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gholamzadeh M, Abtahi H, Ghazisaeeidi M. Applied techniques for putting pre-visit planning in clinical practice to empower patient-centered care in the pandemic era: a systematic review and framework suggestion. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:458. 10.1186/s12913-021-06456-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hjelle EG, Bragstad LK, Zucknick M, et al. The general health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) as an outcome measurement in a randomized controlled trial in a Norwegian stroke population. BMC Psychol 2019;7:18. 10.1186/s40359-019-0293-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anjara SG, Bonetto C, Van Bortel T, et al. Using the GHQ-12 to screen for mental health problems among primary care patients: Psychometrics and practical considerations. Int J Ment Health Syst 2020;14:62. 10.1186/s13033-020-00397-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khatri RB, Mengistu TS, Assefa Y. Input, process, and output factors contributing to quality of Antenatal care services: a Scoping review of evidence. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022;22:977. 10.1186/s12884-022-05331-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng J, Huang S, Wang L, et al. Conceptual framework for smart health: A multi-dimensional model using IPO logic to link drivers and outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:24:16742. 10.3390/ijerph192416742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez R, Kozlowski SWJ, Shapiro MJ, et al. Toward a definition of teamwork in emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:1104–12. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Körner M, Wirtz MA, Bengel J, et al. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in Interprofessional teams. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:243. 10.1186/s12913-015-0888-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahari Shargh R, Rostami S, Abtahi H, et al. The Iranian newborn multiples Registry (IRNMR): a Registry protocol. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2022;35:5213–6. 10.1080/14767058.2021.1875445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heins MJ, de Ligt KM, Verloop J, et al. Opportunities and obstacles in linking large health care registries: the primary secondary cancer care Registry - breast cancer. BMC Med Res Methodol 2022;22:124. 10.1186/s12874-022-01601-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desai A, Mohammed TJ, Duma N, et al. COVID-19 and cancer: a review of the Registry-based pandemic response. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:1882–90. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.4083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forsythe LP, Carman KL, Szydlowski V, et al. Patient engagement in research: early findings from the patient-centered outcomes research Institute. Health Affairs 2019;38:359–67. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pulimeno M, Piscitelli P, Colazzo S, et al. School as ideal setting to promote health and wellbeing among young people. Health Promot Perspect 2020;10:316–24. 10.34172/hpp.2020.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnaiz P, Adams L, Müller I, et al. Sustainability of a school-based health intervention for prevention of non-communicable diseases in Marginalised communities: protocol for a mixed-methods cohort study. BMJ Open 2021;11:e047296. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dabravolskaj J, Montemurro G, Ekwaru JP, et al. Effectiveness of school-based health promotion interventions Prioritized by Stakeholders from health and education sectors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med Rep 2020;19:101138. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McIsaac J-L, Penney TL, Ata N, et al. Evaluation of a health promoting schools program in a school board in Nova Scotia, Canada. Prev Med Rep 2017;5:279–84. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee A, Cheng FFK, Yuen H, et al. Achieving good standards in health promoting schools: preliminary analysis one year after the implementation of the Hong Kong healthy schools award scheme. Public Health 2007;121:752–60. 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee A, Lo A, Li Q, et al. Health promoting schools: an update. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2020;18:605–23. 10.1007/s40258-020-00575-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zurc J, Laaksonen C. Effectiveness of health promotion interventions in primary schools-A. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11:13. 10.3390/healthcare11131817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gholamzadeh M, Abtahi H, Safdari R. Suggesting a framework for preparedness against the pandemic outbreak based on medical Informatics solutions: a thematic analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage 2021;36:754–83. 10.1002/hpm.3106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:1–8. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oginni OA, Ayorinde A, Ayodele KD, et al. The challenges and opportunities for mental health twin research in Nigeria. Behav Genet 2024;54:42–50. 10.1007/s10519-023-10153-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-080443supp001.pdf (72.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-080443supp002.pdf (258.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2023-080443supp003.pdf (147.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

In summary, experts recommend a reliable web-based platform for recording data. They suggest storing all health data of the twins in a relational database through a continuous HPPP, allowing for the comparison of information of multiple pairs with each other and with their family’s medical records. An electronic medical record should be created for each pair of twins individually for follow-up, enabling doctors to record twin information in real time during clinic visits. Our previous experiences with twin data entry have shown that using an electronic questionnaire to collect information alone cannot provide us with the necessary reports. Additionally, the high cost of data entry through paper-based questionnaires or electronic forms in a long-term study was another problem. The proposed structure for recording twin data has been investigated in our previous article.6

All follow-up data will be stored in electronic medical records, allowing easy referral of twin pairs to appropriate specialists in case of a diagnosed problem. By recording twin information and tracking the health of the twins and their families, a valuable database for HPPP and further follow-up programmes for twins will be created. The database can also serve as a data source for academic researchers interested in twin studies.

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.