Abstract

Context

The relationship between the genomic profile and prognosis of advanced thyroid carcinoma requiring drug therapy has not been reported.

Objective

To evaluate the treatment period and overall survival time for each genetic alteration in advanced thyroid carcinoma that requires drug therapy.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational study using a national database in Japan, which included 552 cases of thyroid carcinoma out of 53 543 patients in the database.

Results

The database included anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (23.6%), poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (10.0%), and differentiated thyroid carcinoma (66.4%). The most common genetic abnormalities were TERT promoter (66.3%), BRAF (56.7%), and TP53 (32.2%). The typical driver genes were BRAF V600E (55.0%), RAS (18.5%), RET fusion (4.7%), NTRK fusion (1.6%), and ALK fusion (0.4%). The most common regimen was lenvatinib, and the time to treatment failure was not different despite the presence of BRAF or RAS mutations. In differentiated thyroid carcinoma and poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma, TP53 alterations independently predicted worse overall survival (hazard ratio = 2.205, 95% confidence interval: 1.135-4.283). In anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, no genetic alterations were associated with overall survival.

Conclusion

Genetic abnormalities with treatment options were found in 62.7% of advanced thyroid carcinomas. TP53 abnormality was an independent poor prognostic factor for overall survival in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. The time to treatment failure for lenvatinib was not different based on genetic profile.

Keywords: thyroid carcinoma, gene, comprehensive genetic profiling test, mutations, fusions, targeted therapy

Tumors originating from thyroid follicular cells are the most common type of thyroid carcinoma and are classified into BRAF-like malignancies, represented by papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs) with many morphological subtypes, and RAS-like malignancies, represented by invasive encapsulated follicular variant PTC and follicular thyroid carcinoma (1). In addition to BRAF and RAS mutations, RET and NTRK fusion genes are typical driver genes that are acquired early during PTC (2). However, RAS mutations are observed in 30% to 45% of follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) cases, and PAX8/PPAR fusion is the second most common genetic abnormality in approximately 30% of cases (3, 4). In addition to these early-acquired genetic abnormalities, accumulation of TERT promoter mutations and TP53 abnormalities are thought to increase the malignancy of the tumor and result in anaplastic transformation (5).

Most thyroid carcinomas can be controlled with surgery and radioactive iodine therapy. However, in a small number of patients, the disease progresses despite these treatments, and drug therapy is required. Multikinase inhibitors, such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, have been used successfully to treat thyroid carcinoma (6, 7), and specific inhibitors for genetic abnormalities acquired early, such as BRAF, RET, and NTRK alterations, are effective (8-12). Thyroid carcinoma is characterized by many genetic abnormalities that can be therapeutic targets. However, large-scale studies of drug treatments and genetic profiles have not been reported.

A national database in Japan, the C-CAT, was established to register advanced cancer cases wherein comprehensive genetic profiling (CGP) tests were performed. The C-CAT includes clinical data sent by the participating hospitals and the sequence data of CGP tests. It also facilitates the appropriate secondary use of repository data for researchers in academic institutions and industries upon the consent of the patients (13, 14). Most thyroid carcinomas have a good prognosis, and genetic profile information in advanced cases is valuable. Therefore, we decided to use the C-CAT database to search for the relationship between prognosis and genetic abnormalities in advanced thyroid carcinomas that require drug therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This retrospective observational study collected clinical and genomic data from the C-CAT database (ver. 20230622) in July 2023. All data used for the analysis were obtained from patients who provided written informed consent and consent for future research use when registering for the database. In Japan, national health insurance coverage for the CGP tests was introduced in June 2019 for patients with solid cancers wherein no standard treatment is available or standard treatment is expected to be completed. In thyroid cancer patients, the main targets for CGP tests are differentiated thyroid carcinomas (DTCs) that cannot be controlled by surgery, radioactive iodine therapy, or multikinase inhibitors and unresectable anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). Therefore, patients registered in the database include only those with advanced cancer. At the time of data collection, 3 CGP tests had been approved; OncoGuide™ NCC Oncopanel System (NCC) (Sysmex Co., Ltd., Kobe, Japan), FoundationOne® CDx (F1CDx), and FoundationOne® Liquid CDx (F1L) (Foundation Medicine Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA). F1CDx and F1L are DNA-based next-generation sequencing panel tests that include 324 genes and use tumor tissues and blood, respectively. NCC is also a DNA-based next-generation sequencing panel test that includes 124 genes using tumor tissue and blood.

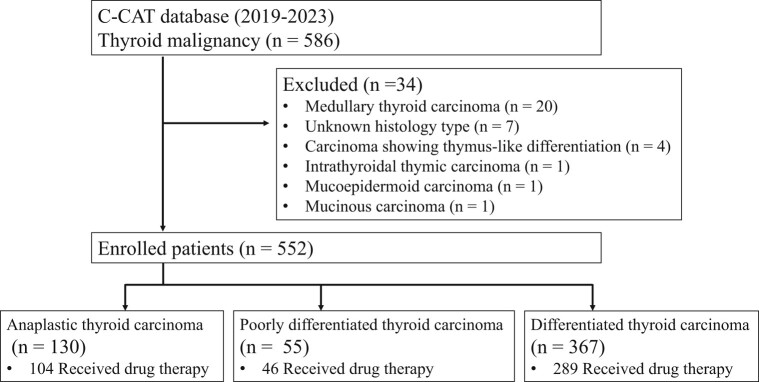

From June 2019 to June 2023, 586 out of 53 543 cases registered in the C-CAT database cases had thyroid malignancy. Medullary thyroid carcinoma, carcinoma showing thymus-like differentiation, intrathyroidal thymic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, or with unknown histology type were excluded to qualify malignant tumors derived from the follicular epithelium. The remaining 552 cases consisting of ATC, DTC, and poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma (PDTC) were analyzed. This study was approved by the Kanagawa Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (no. 2022-144) and by the review board of C-CAT (C-CAT control no. CDU2023-005N).

Methods

The following background characteristics were collected from the C-CAT database: pathological diagnosis, age, sex, smoking history, excessive alcohol use, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), metastatic organs, pharmacotherapy history, and CGP testing methods. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) status were estimated via the CGP tests. Cases with a TMB of level 10 or with high mutations per megabase were defined as TMB-high. Druggable gene alterations include NTRK fusions, RET fusions, ALK fusions, BRAF V600E mutation, TMB-high, or MSI-high.

To evaluate treatment efficacy, the overall response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), and time to treatment failure (TTF) were estimated. ORR was defined as the proportion of the patients with a complete or partial response. DCR was defined as the proportion of the patients with a complete response, partial response, or stable disease. These were evaluated by the physicians according to the Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors version 1.1. TTF was defined as the time from the start of treatment to the end of treatment or death due to any cause. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the start of treatment to the date of death, regardless of cause.

The clinical annotations provided by C-CAT were used to assess genomic alterations (14). To analyze each alteration, we consulted the Evidence Database of C-CAT, which contains clinical evidence for specific mutations, encompassing categories such as predictive, prognostic, diagnostic, predisposing, pathogenic, and oncogenic information. The data are acquired from C-CAT's proprietary and from publicly accessible databases, including Clinical Interpretation of Variants in Cancer (15), BRCA Exchange (16), ClinVar (17), and Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (18). Genes annotated as “oncogenic,” “pathogenic,” “likely oncogenic,” and “likely pathogenic” were extracted. For some patients, clinical data were missing, likely from encoding errors from each attending physician. Therefore, the analyses included patients with fixed data.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher's exact test was used to compare all categorical variables. Survival analysis was performed with 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. A Cox proportional hazard regression model was used for multivariable analysis to estimate the association between genetic alterations and OS, using variables with P < .2 on univariable analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The oncoplot was drawn using maftools (version 2.17.0) (19).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Among 552 patients in this study, 130 (23.6%) had ATC, 307 (55.6%) had PTC, 55 (10.0%) had FTC, 5 (0.9%) had well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma, and 55 (10.0%) had PDTC. Drug therapy was received by 104 (80.0%) patients with ATC, 289 (78.7%) with DTC, and 46 (83.6%) with PDTC (Fig. 1). The clinical characteristics of all patients at the time of registration according to their pathological types are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 71 years (minimum: 4, first quartile: 61, third quartile: 75, maximum: 89), with 310 (56.2%) females 242 (43.8%) males. ECOG-PS was 0 or 1 in most cases. Metastasis was seen in 522 (94.5%) patients, with the most common metastatic sites being the lung in 381 patients (73%), lymph node in 306 patients (58.6%), and bone in 143 patients (27.4%).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| ATC | PTC | FTC | WDTC | PDTC | Total | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 130 | n = 307 | n = 55 | n = 5 | n = 55 | n = 552 | ||

| Age (median) | 72 | 70 | 67 | 61.5 | 72 | ||

| Sex, n (%) | .129 | ||||||

| Male | 49 (37.7) | 142 (46.3) | 25 (45.5) | 2 (40) | 24 (43.6) | 242 (43.8) | |

| Female | 81 (62.3) | 165 (53.7) | 30 (54.5) | 3 (60) | 31 (56.4) | 310 (56.2) | |

| Smoking history, n (%) | 52 (40) | 114 (37.1) | 15 (27.3) | 1 (20) | 25 (45.5) | 207 (37.5) | .535 |

| Excessive alcohol use, n (%) | 20 (15.4) | 35 (11.4) | 4 (7.3) | 0 | 6 (10.9) | 65 (11.8) | .116 |

| ECOG-PS, n (%)b | .748 | ||||||

| 0, 1 | 122 (93.8) | 299 (97.4) | 53 (96.4) | 5 (100) | 52 (94.5) | 531 (96.2) | |

| 2, 3 | 4 (3.1) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 14 (2.5) | |

| Presence of metastasis, n (%) | 116 (89.2) | 293 (95.4) | 54 (98.2) | 5 (100) | 54 (98.2) | 522 (94.6) | .006 |

| Metastatic organs, n (%) | |||||||

| Lung | 82 (70.7) | 224 (76.5) | 31 (57.4) | 4 (80) | 40 (74.1) | 381 (73) | .104 |

| Lymph node | 67 (57.8) | 188 (64.2) | 18 (33.3) | 2 (40) | 31 (57.4) | 306 (58.6) | .315 |

| Bone | 12 (10.3) | 64 (21.8) | 40 (74.1) | 3 (60) | 24 (44.4) | 143 (27.4) | <.001 |

| Liver | 6 (5.2) | 13 (4.4) | 7 (13) | 0 | 4 (7.4) | 30 (5.7) | .825 |

| Pleura | 4 (3.4) | 22 (7.5) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (20) | 2 (3.7) | 31 (5.9) | .192 |

| Brain | 1 (0.9) | 19 (6.5) | 2 (3.7) | 1 (20) | 4 (7.4) | 27 (5.2) | .009 |

| Number of regimens, n (%) | .002 | ||||||

| 0, 1 | 120 (92.3) | 252 (82.1) | 45 (81.8) | 4 (80) | 41 (74.6) | 462 (83.7) | |

| >2 | 10 (7.7) | 55 (17.9) | 10 (18.2) | 1 (20) | 14 (25.4) | 90 (16.3) | |

| Genomic profiling test, n (%) | .155 | ||||||

| F1CDx | 111 (85.4) | 254 (82.7) | 39 (70.9) | 3 (60) | 43 (78.2) | 450 (81.5) | |

| F1L | 7 (5.4) | 28 (9.1) | 11 (20) | 2 (40) | 6 (10.9) | 54 (9.8) | |

| NCC | 12 (9.2) | 25 (8.1) | 5 (9.1) | 0 | 6 (10.9) | 48 (8.7) | |

| Sample collection method, n (%) | .017 | ||||||

| Surgery | 86 (66.2) | 230 (74.9) | 31 (56.4) | 1 (20) | 40 (72.7) | 388 (70.3) | |

| Biopsy | 37 (28.5) | 49 (16) | 13 (23.6) | 2 (40) | 9 (16.4) | 110 (19.9) | |

| Specific collection site, n (%) | <.001 | ||||||

| Thyroid | 94 (72.3) | 88 (28.7) | 18 (32.7) | 0 | 26 (47.3) | 226 (40.9) | |

| Lymph node | 19 (14.6) | 107 (34.9) | 8 (14.5) | 2 (40) | 14 (25.5) | 150 (27.2) | |

| Lung | 3 (2.3) | 27 (8.8) | 5 (9.1) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 38 (6.9) | |

| Soft tissue | 3 (2.3) | 20 (6.5) | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 27 (4.9) | |

| Bone | 0 (0) | 5 (1.6) | 9 (16.4) | 0 | 0 | 14 (2.5) | |

| Liver | 2 (1.5) | 5 (1.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 10 (1.8) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5) | 27 (8.8) | 1 (1.8) | 1 (20) | 2 (3.6) | 33 (6) |

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; F1CDx, FoundationOne® CDx; F1L, FoundationOne® Liquid CDx; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; NCC OncoGuide™, NCC Oncopanel System; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; WDTC, well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma.

P < .05 are shown in bold.

a ATC vs non-ATC.

b Data available for 126 patients with ATC and 304 patients with PTC.

When comparing ATC to DTC and PDTC, we noted no significant differences in terms of sex, smoking history, excessive alcohol use, or ECOG-PS. Metastasis, particularly to the bone and brain, was significantly less frequent in ATC. Patients with ATC also had fewer prior treatment regimens. In terms of CGP testing, F1CDx, F1L, and NCC tests were performed in 450 (81.5%), 54 (9.8%), and 48 (8.7%) cases, respectively. As a method of tissue collection, biopsies were performed most frequently in ATC, with the thyroid being the most common site for tissue collection. For PTC, the most common site of tissue collection was the lymph nodes.

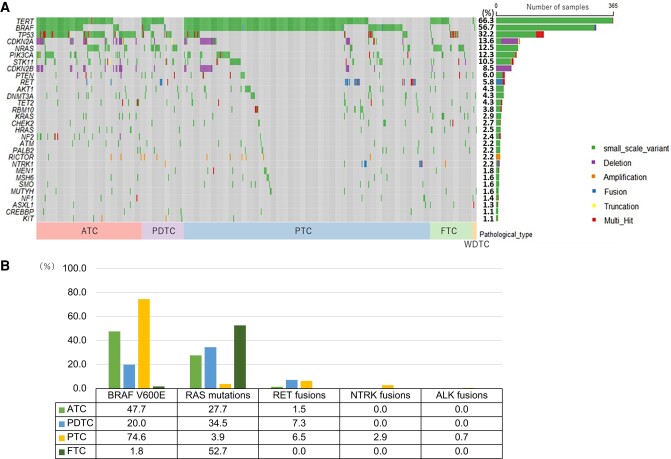

Genomic Characteristics

The most common genetic abnormalities across all tissue types were TERT promoter (n = 336, 66.3%), BRAF (n = 313, 56.7%), and TP53 (n = 178, 32.2%) (Fig. 2A). The typical driver genes were BRAF V600E mutation (n = 304, 55.1%), RAS mutation (n = 102, 18.5%), RET fusion (n = 26, 4.7%), NTRK fusion (n = 9, 1.6%), and ALK fusion (n = 2, 0.4%). Among patients with PTC, BRAF V600E mutation was the most common (in 229 cases, 74.6%), followed by RET fusion (in 20, 6.5%), RAS mutation (in 12, 3.9%), and NTRK fusion (in 9, 2.9%). Of the patients with FTC, 19 cases (34.5%) had NRAS mutations, 6 cases (10.9%) had KRAS mutations, and 4 cases (7.3%) had HRAS mutations. Because the gene panel tests in this study could not reveal PPARγ/PAX8 fusion, other frequently occurring driver genes were not detected. Of the patients with PDTC, 19 cases (34.5%) had RAS mutations, 11 cases (20%) had BRAF V600E mutation, and 4 cases (7.3%) had RET fusion. Of the patients with ATC, 62 cases (47.7%) had BRAF V600E mutation, 36 cases (27.7%) had RAS mutations, and 2 cases (1.5%) had RET fusion, which suggests that some cases of PTC and FTC transformed into ATC as inheriting driver genes (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Overview of the most common genomic alterations. The right bar shows the number and the frequency of cases with gene alterations in each gene. (B) The frequency of representative driver genes.

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; WDTC, well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma.

Genetic alterations that were significantly common in ATC included tumor suppression genes (eg, TP53, NF2, and RB1), PI3K/AKT pathway genes, cell cycle pathway genes, and epigenetic modification genes (eg, TET2) (Table 2). No genetic alterations had significantly higher frequency in PDTC and DTC, except for RBM10, which is an RNA-binding protein that regulates the alternative splicing of pre-mRNA, suggesting that gene mutations are accumulated more in ATC. Additionally, TMB was significantly higher in ATC than the others, suggesting genomic instability of ATC (mean: 3.02 vs 1.95, P < .001). TMB-high was seen in 12 cases (2.2%) of all thyroid carcinomas including 8 cases (6.2%) of ATC, 1 case (1.8%) of PDTC, and 3 cases (1.0%) of PTC. However, MSI-high cancer was not seen in any pathological type. The frequency of druggable gene alterations was 52.3% (68/130) in ATC, 29.1% (16/55) in PDTC, 84.7% (260/307) in PTC, and 1.8% (1/55) in FTC.

Table 2.

Genes more frequently altered in ATC than in differentiated and PDTC

| Gene | Prevalence, n (%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATC | DTC and PDTC | ||

| TP53 | 103 (79.2) | 75 (17.8) | <.001 |

| CDKN2A | 34 (26.2) | 41 (9.7) | <.001 |

| PIK3CA | 27 (20.8) | 41 (9.7) | .002 |

| NRAS | 24 (18.5) | 45 (10.7) | .023 |

| CDKN2B | 22 (16.9) | 25 (5.9) | <.001 |

| NF2 | 14 (10.8) | 1 (0.2) | <.001 |

| TET2 | 10 (7.7) | 14 (3.3) | .046 |

| RB1 | 5 (3.8) | 1 (0.2) | .003 |

| TSC1 | 4 (3.1) | 2 (0.5) | .03 |

| KDR | 3 (2.3) | 1 (0.2) | .042 |

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; DTC, differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma.

Treatment

Among the registered treatment regimens, the most common treatment was lenvatinib, followed by sorafenib. In ATC, lenvatinib was the most common, followed by paclitaxel. Although details of the investigational drugs are unknown, there was little use of combined therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors, which were not approved in Japan (Table 3). We investigated the response rate for lenvatinib, which is the most common first-line regimen. The ORR was 17.4% (12/69) in ATC, 51.9% (84/162) in PTC, 41.0% (16/39) in FTC, and 50.0% (14/28) in PDTC. The DCR was 52.2% (36/69) in ATC, but this was 82.8% (192/232) in DTC and PDTC. ORR and DCR are significantly lower in ATC than in DTC and PDTC (P < .001, Table 4).

Table 3.

Administered regimen

| Number of patients who received drug therapy, n (%) | ATC | PTC | FTC | WDTC | PDTC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 104 | n = 237 | n = 48 | n = 4 | n = 46 | n = 439 | |

| Lenvatinib | 75 (72.1) | 186 (78.5) | 41 (85.4) | 3 (75) | 36 (78.3) | 341 (77.7) |

| Sorafenib | 1 (1) | 59 (24.9) | 11 (22.9) | 1 (25) | 14 (30.4) | 86 (19.6) |

| Selpercatinib | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (0.7) |

| Larotrectinib | 0 (0) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.7) |

| Pembrolizumab | 2 (1.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 4 (0.9) |

| Nivolumab + lenvatinib | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Dabrafenib + trametinib | 3 (2.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.9) |

| Encorafenib + binimetinib | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Paclitaxel | 15 (14.4) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 2 (4.3) | 20 (4.6) |

| Other chemotherapy | 4 (3.8) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.2) | 7 (1.6) |

| Investigated agent | 5 (4.8) | 25 (10.5) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (13) | 37 (8.4) |

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; WDTC, well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma.

Table 4.

Best overall response of first-line lenvatinib

| Response, n (%) | ATC | PTC | FTC | PDTC | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 69 | n = 162 | n = 39 | n = 28 | ||

| Complete response | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Partial response | 10 (14.5) | 84 (51.9) | 16 (41) | 14 (50) | |

| Stable disease | 24 (34.8) | 51 (31.5) | 16 (41) | 8 (28.6) | |

| Progressive disease | 8 (11.6) | 7 (4.3) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Not evaluable | 25 (36.2) | 20 (12.3) | 6 (15.4) | 5 (17.9) | |

| Overall response rate | 12 (17.4) | 84 (51.9) | 16 (41.0) | 14 (50.0) | <.001 |

| Disease control rate | 36 (52.2) | 135 (83.3) | 32 (82.1) | 22 (78.6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma.

a ATC vs non-ATC.

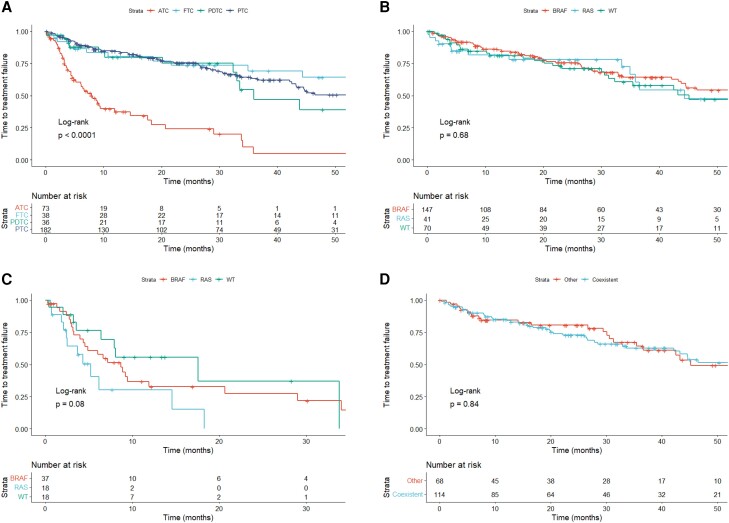

Afterward, we examined TTF for first-line lenvatinib. The TTF was significantly shorter in cases with ATC than with DTC and PDTC (P < .0001, Fig. 3A). In DTC and PDTC patients, the median TTF was not significantly different among cases with specific genetic mutations (P = .68, Fig. 3B). The median TTF across ATC cases with genetic mutations also had no significant differences (P = .08, Fig. 3C). In PTC, TTF for first-line lenvatinib had no significant differences according to concurrent of BRAF and TERT promotor mutations (P = .84, Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves of TTF according to first-line lenvatinib therapy. (A) TTF by histological types; (B) TTF of DTC and PDTC classified as BRAF-positive, RAS-positive, and both negative; (C) TTF of ATC classified as BRAF-positive, RAS-positive, and both negative; (D) TTF of PTC by BRAF and TERT promoter mutations.

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; DTC, differentiated thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; TTF, time to treatment failure; WT, wild-type.

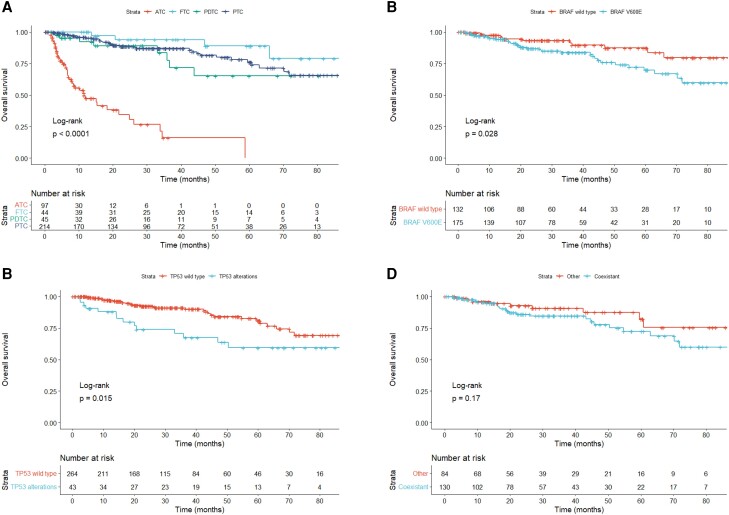

OS

The Kaplan–Meier curves of OS for each pathological type are shown in Fig. 4A. OS was significantly shorter in ATC, with a median OS of 11.5 months (95% CI 7.9-21.7), compared to FTC [not accessible (NA), 95% CI 66.0–NA], PDTC (107.5 months, 95% CI 36.6–NA), and PTC (94.0 months, 95% CI 94.0–NA). To examine the association between genetic alterations and OS, age (<65 and ≥65 years), sex, presence of lung or bone metastasis, pathological types, BRAF mutation, RAS mutations, RET or NTRK fusion genes, TERT promoter mutations, and TP53 alterations were compared via log-rank test. In DTC and PDTC, cases with BRAF V600E mutation and TP53 alterations had significantly shorter OS: the median OS was 107.5 months (95% CI NA–NA) in wild-type BRAF, 94.0 months (95% CI 70.2–NA) in BRAF V600E, 107.5 months (95% CI 94.0–NA) in wild-type TP53, and NA (95% CI 35.9–NA) in TP53 alterations (Fig. 4B and 4C). Factors with log-rank test P < .2 in the Kaplan–Meier method were used to construct the Cox proportional hazards regression model. As shown in Table 5, TP53 alterations remained an independent predictor of worse OS (hazard ratio = 2.205, 95% CI 1.135-4.283). Furthermore, we investigated whether the coexistence of BRAF and TERT promotor mutations affected OS in PTC; however, no significant difference was observed (P = .17, Fig. 4D). In ATC, there were no significant differences in any variables, and no genetic alterations associated with OS were observed.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves of OS. (A) OS by histological types; (B) OS of DTC and PDTC by BRAF V600E mutation status; (C) OS of DTC and PDTC by TP53 abnormality; (D) OS of PTC by BRAF and TERT promoter mutations.

Abbreviations: ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; DTC, differentiated thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; OS, overall survival; PDTC, poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazards regression modeling details in differentiated and poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma

| Overall survival | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | ||

| Age (<65 vs ≥65) | 1.543 (0.722-3.295) | .263 |

| Bone metastasis (yes vs no) | 0.626 (0.309-1.269) | .194 |

| BRAF V600E mutation (yes vs no) | 1.568 (0.761-3.230) | .223 |

| TERT promoter mutation (yes vs no) | 1.492 (0.734-3.034) | .269 |

| TP53 alterations (yes vs no) | 2.205 (1.135-4.283) | .020 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

P < .05 are shown in bold.

Discussion

In this study, we used the C-CAT database, which is a national repository that contains information about only patients who underwent CGP testing (14). Because Japan has a public insurance system, CGP testing is performed for only in cases of advanced cancers that necessitate drug therapy. Therefore, DTC is classified as an advanced cancer with distant metastasis or an unresectable locally advanced cancer. Approximately 80% of patients with DTC and PDTC were treated with drugs including multikinase inhibitors. However, because ATC progresses rapidly and treatment options are limited, CGP testing is often performed at the time of diagnosis. Patients with ATC were therefore less likely than those with DTC to have distant metastases and a history of prior treatment at the time of registry.

The most common genetic abnormality in advanced thyroid cancer is TERT promoter mutations, which were observed in 66% of cases. According to a previous report, TERT promoter mutations were found in approximately 10% of patients with PTC, 17% of those with FTC, and 40% of those with ATC (20); these rates were lower than those in our study. TERT promoter mutations have a significantly high prevalence among cancers with aggressive histologic features, those in advanced stages, and those with distant metastases (20). The frequency of TERT promoter mutations may have been high in this study because we assessed only patients with advanced cancer. TERT promoter mutations were common in advanced cancers, both DTC and ATC, whereas TP53 alterations were more abundant in ATC than in DTC. Oishi et al reported that TP53 alterations are more frequently expressed in ATC components than in PTC components in cases of concurrent ATC and PTC (21). Furthermore, in a study of the gene profile of advanced cancers in the United States, TERT promoter mutations were common in DTC and ATC whereas TP53 was abundant only in ATC (5); this gene profile was similar to that in this study. Comparing ATC and non-ATC, gene alterations such as tumor suppression genes or PI3K/AKT pathway genes were significantly more common in ATC, suggesting that gene mutations are accumulated more in ATC as previously reported (5). On the other hand, RBM10, which codes a RNA-binding protein that regulates the alternative splicing of pre-mRNA, was the only gene that was frequently mutated in DTC and PDTC. RBM10 mutations have been reported to occur frequently in advanced DTC and PDTC, at a frequency of 7% to 11% (22), although they are infrequent in ATC (23). Furthermore, RBM10 abnormalities are associated with RAI refractory and poorer survival in DTC (24). In this study, most cases with DTC were refractory to RAI, were treated with drug therapy, and were fatal. Therefore, RBM10 mutations were more common in DTC and PDTC, similar to the previous reports.

Genetic abnormalities in thyroid carcinoma that appear early include many therapeutic targets. Of the patients with PTC, 84.7% had therapeutic targets, including BRAF V600E mutation (in 74.6%), RET fusion (in 6.5%), and NTRK fusion (in 2.9%). In the Cancer Genome Atlas study, RET and NTRK fusions were found in 6.8% and 1.2% cases, respectively, of mostly nonmetastatic thyroid cancers (25) and thus were as frequent as in our study. In another study, RET and NTRK fusions were found in 28% and 18%, respectively, of pediatric patients with PTC (26). The median age in this study was 71 years, which reflects the prevalence of cases among older adults who require drug therapy. Combined therapy with dabrafenib and trametinib has been reported to be effective in cases of ATC involving BRAF V600E mutation (8). BRAF V600E mutation was found in 47.7% of the patients with ATC in our study; this frequency is similar to that previously reported (5, 27). On the other hand, approximately half of the patients with ATC had no drug-therapeutic targets; thus, drugs must be developed for such cases. Another problem is that only 1.8% of patients with FTC with mainly RAS mutations have drug-therapeutic targets, and treatment options other than multikinase inhibitors are limited.

The most commonly used drug was lenvatinib, which was administered to 78% of patients who underwent drug therapy. In Japan, lenvatinib is also approved for ATC. Although lenvatinib was administered to 72% of the patients with ATC in this study who received drug therapy, their response rate was worse than that among patients with DTC. In the phase 3 SELECT study, lenvatinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival compared to placebo (7). The analysis of the SELECT study reported that cases with wild-type BRAF had a shorter progression-free survival than those with BRAF V600E mutation (28). However, in this study, TTF showed no difference regardless of the presence of BRAF or RAS mutations. This suggests that lenvatinib is effective regardless of the driver genes.

It has been reported that BRAF and TERT promoter mutations are associated with a high rate of malignancy in PTC (20). When OS from the start of drug therapy was evaluated, BRAF and TP53 alterations were found to be factors for poor prognostics in DTC and PDTC. Furthermore, according to the Cox proportional hazards regression model, the presence of TP53 alterations was an independent factor for poor prognosis. Although TP53 alterations are known to be significantly abundant in cases of ATC (5), DTC with TP53 alterations may reflect a state close to anaplastic transformation. Moreover, TERT promoter mutations have been shown to interact with BRAF mutations (29), and the coexistence of BRAF and TERT promoter mutations is a factor for poor prognosis in PTC (30, 31). This study is, to our knowledge, the first investigation of the influence of the coexistence of BRAF and TERT promoter mutations in patients with advanced thyroid carcinoma who require drug therapy, but we found no significant differences between patients with and without these coexisting mutations. The patients in this study had extremely advanced cancer, and TERT promoter mutations were observed in more than 60% of cases. The aggressiveness of these tumors may be associated with TP53 alterations. In this study, the prognosis of patients with ATC did not differ between those who had and did not have BRAF V600E mutation, but the data were obtained in a situation in which access to BRAF inhibitors was limited. According to a single-center retrospective analysis, OS improved with the introduction of BRAF-directed therapy (27), and we hope that the approval of BRAF inhibitors will help improve prognosis.

One limitation of this observational study was that we used nonrandomized real-world data and did not intervene in cases of cancer at the time of database registration or treatment strategy. In the information registered by each medical institution, some data were missing, and it was not possible to match patient backgrounds and treatment strategies. Another limitation was selection bias, which occurred because we studied only patients who underwent CGP testing. However, in Japan, examination and treatment are restricted by the public insurance system; therefore, our real-world data included data from only patients with advanced cancers. Furthermore, all patients who underwent CGP tests within the public insurance system are registered in this database, which is quite large. Another feature of this database is that prognosis information is also registered.

In conclusion, we conducted a cohort study of advanced thyroid carcinoma in patients requiring drug therapy. The most common genetic abnormality was TERT promoter mutations, but we found no difference in prognosis with regard to the presence or absence of TERT promoter mutations or whether they coexisted with BRAF V600E mutation. The presence of TP53 alterations was an independent factor for poor prognosis in advanced DTC and PDTC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank C-CAT for the clinical and genomic data.

Abbreviations

- ATC

anaplastic thyroid carcinoma

- CGP

comprehensive genetic profiling

- CI

confidence interval

- DCR

disease control rate

- DTC

differentiated thyroid carcinoma

- ECOG-PS

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status

- F1CDx

FoundationOne® CDx

- F1L

FoundationOne® Liquid CDx

- FTC

follicular thyroid carcinoma

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- NA

not assessable

- NCC

OncoGuide™ NCC Oncopanel System

- ORR

overall response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PDTC

poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma

- PTC

papillary thyroid carcinoma

- TMB

tumor mutation burden

- TTF

time to treatment failure

Contributor Information

Soji Toda, Department of Endocrine Surgery, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Kanagawa 241-8515, Japan; Department of Breast and Thyroid Surgery, Yokohama City University Medical Center, Kanagawa 232-0024, Japan.

Yukihiko Hiroshima, Department of Cancer Genome Medicine, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Kanagawa 241-8515, Japan; Research Institute Division of Advanced Cancer Therapeutics, Kanagawa Cancer Center Research Institute, Kanagawa 241-8515, Japan.

Hiroyuki Iwasaki, Department of Endocrine Surgery, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Kanagawa 241-8515, Japan.

Katsuhiko Masudo, Department of Endocrine Surgery, Kanagawa Cancer Center, Kanagawa 241-8515, Japan.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T., H.I., and Y.H.; methodology, S.T., K.M., and Y.H.; data curation, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T.; writing—review and editing, H.I., K.M., and Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Baloch ZW, Asa SL, Barletta JA, et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of thyroid neoplasms. Endocr Pathol. 2022;33(1):27‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Landa I, Cabanillas ME. Genomic alterations in thyroid cancer: biological and clinical insights. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2024;20(2):93‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raman P, Koenig RJ. Pax-8-PPAR-γ fusion protein in thyroid carcinoma. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(10):616‐623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xing M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(3):184‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pozdeyev N, Gay LM, Sokol ES, et al. Genetic analysis of 779 advanced differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(13):3059‐3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brose MS, Nutting CM, Jarzab B, et al. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9940):319‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schlumberger M, Tahara M, Wirth LJ, et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(7):621‐630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Subbiah V, Kreitman RJ, Wainberg ZA, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic BRAF V600-mutant anaplastic thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):7‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Falchook GS, Millward M, Hong D, et al. BRAF inhibitor dabrafenib in patients with metastatic BRAF-mutant thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2015;25(1):71‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wirth LJ, Sherman E, Robinson B, et al. Efficacy of selpercatinib in RET-altered thyroid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):825‐835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hong DS, DuBois SG, Kummar S, et al. Larotrectinib in patients with TRK fusion-positive solid tumours: a pooled analysis of three phase 1/2 clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(4):531‐540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271‐282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mukai Y, Ueno H. Establishment and implementation of cancer genomic medicine in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(3):970‐977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kohno T, Kato M, Kohsaka S, et al. C-CAT: the national datacenter for cancer genomic medicine in Japan. Cancer Discov. 2022;12(11):2509‐2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Griffith M, Spies NC, Krysiak K, et al. CIVic is a community knowledgebase for expert crowdsourcing the clinical interpretation of variants in cancer. Nat Genet. 2017;49(2):170‐174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cline MS, Liao RG, Parsons MT, et al. BRCA challenge: BRCA exchange as a global resource for variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(12):e1007752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landrum MJ, Chitipiralla S, Brown GR, et al. ClinVar: improvements to accessing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D835‐D844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, et al. COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D941‐D947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mayakonda A, Lin DC, Assenov Y, Plass C, Koeffler HP. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28(11):1747‐1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chung JH. BRAF and tert promoter mutations: clinical application in thyroid cancer. Endocr J. 2020;67(6):577‐584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oishi N, Kondo T, Ebina A, et al. Molecular alterations of coexisting thyroid papillary carcinoma and anaplastic carcinoma: identification of TERT mutation as an independent risk factor for transformation. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(11):1527‐1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ibrahimpasic T, Xu B, Landa I, et al. Genomic alterations in fatal forms of non-anaplastic thyroid cancer: identification of MED12 and RBM10 as novel thyroid cancer genes associated with tumor virulence. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(19):5970‐5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landa I, Ibrahimpasic T, Boucai L, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic hallmarks of poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid cancers. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(3):1052‐1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boucai L, Saqcena M, Kuo F, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic characteristics of metastatic thyroid cancers with exceptional responses to radioactive iodine therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(8):1620‐1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network . Integrated genomic characterization of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Cell. 2014;159(3):676‐690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pekova B, Sykorova V, Dvorakova S, et al. RET, NTRK, ALK, BRAF, and MET fusions in a large cohort of pediatric papillary thyroid carcinomas. Thyroid. 2020;30(12):1771‐1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maniakas A, Dadu R, Busaidy NL, et al. Evaluation of overall survival in patients with anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, 2000-2019. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(9):1397‐1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tahara M, Schlumberger M, Elisei R, et al. Exploratory analysis of biomarkers associated with clinical outcomes from the study of lenvatinib in differentiated cancer of the thyroid. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:213‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Song YS, Yoo SK, Kim HH, et al. Interaction of BRAF-induced ETS factors with mutant TERT promoter in papillary thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019;26(6):629‐641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moon S, Song YS, Kim YA, et al. Effects of coexistent BRAF(V600E) and TERT promoter mutations on poor clinical outcomes in papillary thyroid cancer: a meta-analysis. Thyroid. 2017;27(5):651‐660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu R, Bishop J, Zhu G, Zhang T, Ladenson PW, Xing M. Mortality risk stratification by combining BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations in papillary thyroid cancer: genetic duet of BRAF and TERT promoter mutations in thyroid cancer mortality. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):202‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.