Abstract

Increased cortisol levels in the preovulatory follicular fluid suggests a role of glucocorticoid in human ovulation. However, the mechanisms through which cortisol regulates the ovulatory process remain poorly understood. In this study, we examined the upregulation of f5 mRNA by glucocorticoid and its receptor (Gr) in the preovulatory follicles of zebrafish. Our findings demonstrate a significant increase in 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (hsd11b2), a cortisol response gene, in preovulatory follicles. Additionally, hydrocortisone exerts a dose- and time-dependent upregulation of f5 mRNA in these follicles. Importantly, this stimulatory effect is Gr-dependent, as it was completely abolished in gr−/− mutants. Furthermore, site-directed mutagenesis identified a glucocorticoid response element (GRE) in the promoter of zebrafish f5. Interestingly, successive incubation of hydrocortisone and the native ovulation-inducing steroid, progestin (17α,20β-dihydroxy-4-pregnen-3-one, DHP), further enhanced f5 expression in preovulatory follicles. Overall, our results indicate that the dramatic increase of f5 expression in preovulatory follicles is partially attributable to the regulation of glucocorticoid and Gr.

Keywords: glucocorticoid, coagulation factor, glucocorticoid receptor, ovarian follicles

1. Introduction

In response to the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, preovulatory follicles undergo dramatic morphological and physiological changes necessary for ovulation. The process is tightly regulated by numerous hormones, such as progesterone and prostaglandins (1). Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones primarily produced by the adrenal gland, which regulate a large range of physiological processes, including metabolism, development, cognitive processes, stress response, homeostasis, and inflammation (2). The elevated follicular concentrations of cortisol after the LH surge, along with de novo synthesis of cortisol by ovarian granulosa cells in human preovulatory follicles, suggest a potential role of cortisol in ovulation and corpus luteum formation by acting as an anti-inflammatory factor in ovulatory follicles (3,4). Moreover, women with dysregulated cortisol levels often suffer from menstrual irregularity and anovulatory infertility. In addition, an increased cortisol production rate has been observed in women with lean polycystic ovary syndrome (5–7). In contrast to limited progress in humans, studies in fish have demonstrated that cortisol plays several roles in ovarian processes, such as ovarian aging, vitellogenesis, oocyte maturation, ovulation, and egg quality (8–14). However, the molecular mechanism of cortisol in affecting the ovulatory process remains poorly understood.

The F5 gene encodes coagulation factor V, primainly synthesized in the liver and megakaryocytes, acting as a necessary cofactor in the process of the coagulation cascade (15). Interestingly, our recent studies revealed a remarkably increases of locally produced f5 by the ovarian follicle cells prior to the ovulation in zebrafish (16). Moreover, the f5-mediated blood coagulation in blood capillaries on the surface of the ovarian follicle layer is essential for ovulation. This dramatic increase in f5 mRNA was mediated through the nuclear progesterone receptor (PGR, also known as NR3C3), a well-established initiator of vertebrate ovulation(17,18). Both PGR and glucocorticoid receptor (GR, NR3C1) belongs to the same subfamily of nuclear steroid superfamily (receptor subfamily 3, group C) (19). To activate the transcription of a cis-linked gene, activated nuclear steroid receptors must bind to a DNA element (hormone response element, HRE). It is well-established that GR and PGR share HRE to regulate a substantial number of common target genes (20–22). Interestingly, a recent study revealed the cross-regulation between PGR and GR in primary human granulosa/lutein cells (4). Given that f5 is a newly identified Pgr-mediated ovulatory gene, we hypothesized that glucocorticoids may participate in the regulation of f5 mRNA expression through Gr in the preovulatory follicles of zebrafish. Therefore, in this study, we initially investigated the influence of glucocorticoid on f5 mRNA expression in preovulatory follicles of zebrafish. Additionlly, we examined the Gr response elements (GREs) in the promoter sequence of f5. Furthermore, we investigated the combined effects of progestin and glucocorticoid on f5 mRNA expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and reagents

Maintenance of Zebrafish Tübingen strain and generation of pgr knockout (pgr−/−) were according to standard procedures described in a previous report (18). A frameshift mutant in exon 2 of gr (gr−/−) was kindly provided by Dr. Karl Clark at the Mayo Clinic (23). Fish were fed three times daily with a commercial food (Otohime B2; Marubeni Nisshin Feed) supplemented with newly hatched brine shrimp and were maintained in a recirculating system (ESEN) at 28 ± 0.5 °C under a controlled photoperiod (lights on at 08:00, off at 22:00). The daily ovulation cycle in mature adult zebrafish was established according to a previouly published protocol (16). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Xiamen University. Detailed information for key chemicals and reagents is listed in Supplemental Table 1.

2.2. Collection of ovarian follicles

Ovarian follicles were collected as described in the previously for examining the diurnal changes of target genes (16). Briefly, fully grown immature follicles (stage IVa, Φ > 650 μm, with an opaque appearance) or mature follicles (stage IVb, Φ > 650 μm, with a transparent appearance) were collected at three representative time points during a daily spawning cycle: 05:00 (stage IVa, the onset of oocyte maturation), 06:40 (stage IVb, completion of oocyte maturation but before ovulation), and 20:00 (stage IVa, full grown immature oocyte).

Before sampling, the spinal cord and blood supply behind the gill cover were cut off swiftly using sharp scissors following a lethal dose of anesthetization (MS-222, 300 mg/L buffered solutions). The ovary was immediately removed and transferred to a 60% L-15 media containing 15 mM HEPES at pH 7.2. According to the established follicle classification system, follicles at the different stages were collected using standardized methodology (16). Intact follicles with no damage were placed in a 24-well culture plate containing a 60% L-15 medium for hormone treatments. About 25 same stage follicles from each female were pooled as one sample. Four independent samples from four female fish were collected at each time point. These samples were immediately homogenized in AG RNAex Pro Reagent (ACCURATE BIOTECHNOLOGY(HUNAN)CO.,LTD, ChangSha, China) and stored in a −80 °C freezer until further processing.

2.3. Sample collection for cortisol analysis

Female fish (n ≥ 4) were euthanized with a lethal dose of anesthesia (MS-222, 300 mg/L buffered solutions) at three representative times: 05:00, 06:40, and 20:00. The whole ovary was rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for subsequent cortisol analysis. The frozen samples were homogenized in an ice-cold 1 × PBS buffer and centrifuged at 3000 g for 20 minutes. For cortisol extraction, the supernatants were transferred to glass tubes and mixed with 5 mL diethyl ether by vertexing for 1 minute. Subsequently, the tubes were frozen in a liquid nitrogen bath, and the ether layer containing cortisol was poured into another set of tubes. The diethyl ether was then evaporated off under a flow of air. The extraction procedure was repeated twice to improve the extraction efficiency, and the extract was dissolved in PBS containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin. The amount of cortisol was determined using a commercial cortisol enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit following the protocols provided by the Beijing Sinouk Institute of Biological Technology (China).

2.4. Hormone treatments

For hormone treatments, ovarian follicles at different stages were collected at 14:00 and then incubated at 28 °C with various hormones, or doses, exposure times. A range of hydrocortisone concentrations (1, 10, 100, 1000 nM) with a 2-hour incubation or varying exposure times (1, 2, 4, 6 hours) with 100 nM hydrocortisone were examined. Based on the result of dose- and time-dependent experiments, follicles at different stages were exposed to hydrocortisone (100 nM) for 2 hours. To investigate whether the stimulatory effect of hydrocortisone was mediated via Gr, stage IVa follicles collected from pgr−/−, gr−/− or WT (wild type) were incubated with hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, or 17α,20β-dihydroxy-4-pregnen-3-one (DHP) of 100 nM for 2 hours. Additionally, to study the potential combination effects of hydrocortisone and DHP on the f5 mRNA levels, stage IVa follicles were incubated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) and DHP (1 nM or 10 nM) alone or in combination for 2 hours. Furthermore, stage IVa follicles were incubated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with DHP (10 nM) for 1 hour alone. A minimum of three replicates were collected at each time point. After incubation, about 25 undamaged follicles were collected and homogenized in AG RNAex Pro Reagent and stored in a −80 °C freezer until RNA purification.

2.5. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from ovarian follicles using RNAex Pro Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and its concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop™ One Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). The reverse transcription process was conducted using the Evo M-MLV RT Mix Kit with gDNA Clean for qPCR (ACCURATE BIOTECHNOLOGY(HUNAN)CO.,LTD, ChangSha, China) using 500 ng of total RNA per sample). All quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCRs) were carried out in a 20-μL reaction on the qTOWER 2.2 real-time PCR system (Analytik Jena, German) using the SYBR® Green Pro Taq HS (ACCURATE BIOTECHNOLOGY(HUNAN)CO.,LTD, ChangSha, China). Each primer of a pair was designed to target different exons of the gene (Supplemental Table 2) (16). The expression levels of the target genes were determined as relative values using the comparative Ct method with the ef1α gene, as it remained unchanged between treatments..

2.6. Dual-Luciferase reporter assay

Detailed information on expression and reporter assay plasmid constructs is listed in Supplemental Table 3. To generate a zebrafish Gr expression vector construct, the predicted gr open reading frame (ORF) was PCR amplified using primers overlapping the start and stop codons (Supplemental Table 3), cloned into pcDNA3.1 in the correct orientation. The zebrafish Pgr expression plasmid and pGL3-zf5-Luc plasmid, which contains the f5 promoter sequence (−2081/+46) and Photinus pyralis luciferase gene, were generated in our previous study (16). Potential GREs in the f5 promoter sequence (−2081/+46) were identified using the JASPAR database (Supplemental Table 4). Site-directed mutagenesis of two potential GREs in zebrafish f5 proximal promoter sequences was conducted using a Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293T) were used for the transactivation assays (16). Briefly, cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a phenol red-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco), supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (Meilunbio) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Vivacell). Transient transfection was carried out using lipo8000 (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cells were transiently transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter plasmid (3 μg/vector/60 mm petri dish), the pRL-TK vector (150 ng/60 mm petri dish) containing the Renilla luciferase reporter gene (as an internal control for transfection efficiency), and a Pgr or a Gr expression vector (1.5 μg/vector/60 mm petri dish). After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, the medium was replaced with luciferase assay medium (DMEM without phenol red, supplemented with 10% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum) containing various concentrations of different hormones or vehicle. Following an additional 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C, the cells were washed with 1 × PBS buffer and harvested to determine firefly and Renilla luciferase activities according to the Dualucif® Firefly & Renilla Assay Kit (US EVERBRIGHT, Suzhou, China) on a luminometer (GloMax 20/20, Promega). Firefly luciferase activities were normalized using Renilla luciferase data, and induction factors were calculated as the ratios of the average luciferase value of the steroid-treated samples compared to the vehicle-treated samples.

2.7. Statistical analyses

Data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 8. Depending on the experimental setup, statistical differences compared to the control group were assessed using either the Student’s unpaired t test, or one-way analysis of variance (one-tailed) followed by the Dunnett post hoc test. Each experiment (e.g., qPCR, hormone exposure, reporter assay) was repeated at least once.

3. Results

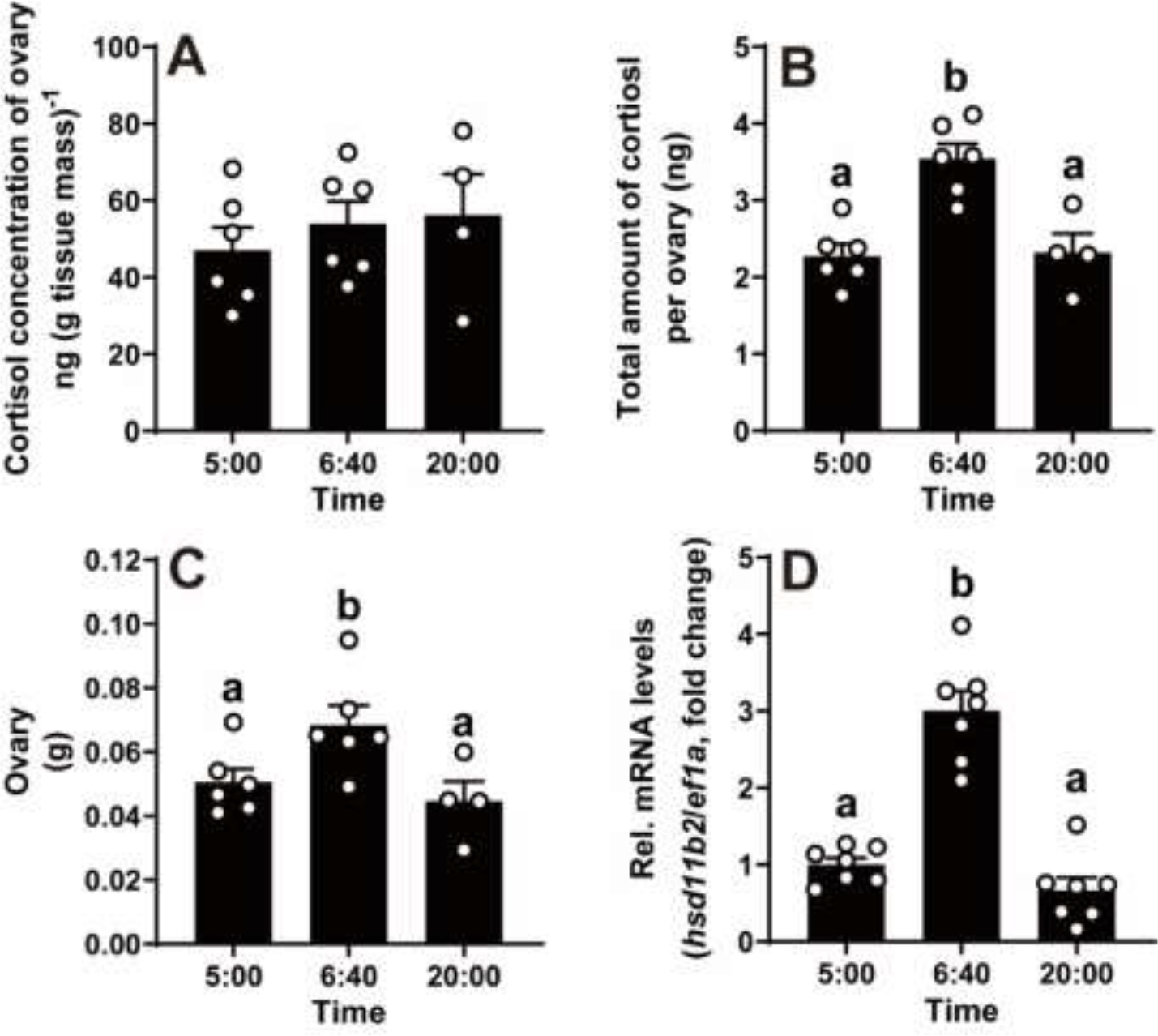

3.1. Cortisol and hsd11b2 mRNA in the ovary during a natural spawning cycle in vivo

No significant change in the ovarian cortisol concentration was observed during a natural spawning cycle (Fig 1A). However, the total amount of cortisol per ovary collected at 06:40 prior to ovulation was significantly higher than that collected at 05:00 and 20:00 (Fig. 1B). Correspondingly, ovary reached the highest weight at 06:40, while the lowest weight was observed at 05:00 and 20:00 (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. Changes in ovarian cortisol levels and hsd11b2 transcript in stage IV follicles during a daily spawning cycle in vivo in zebrafish.

Samples were collected at three representative time points: 05:00 (prior to oocyte maturation), 06:40 (after oocyte maturation but prior to ovulation), and 20:00 (12 hours after lights on). The whole ovary was weighed and collected for cortisol analysis using ELISA. Fully grown ovarian follicles (stage IVa or IVb) were collected for gene expression analysis.

A, The cortisol concentration in the ovary did not change during a daily spawning cycle. B, The total amount of cortisol per ovary peaked at 06:40. C, The ovary weight peaked at 06:40. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N ≥ 4). D, An increase of hsd11b2 mRNA in preovulatory follicles during a daily spawning cycle in vivo. Expression of hsd11b2 mRNA was determined by qPCR and normalized to an internal control (ef1α). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 7) relative to the respective transcript levels of hsd11b2 in IVa follicles collected at 05:00. Bar maked with different letters indicated significant differences between each other (P < 0.05, Student’s unpaired t test).

11β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (Hsd11b2) is an NAD+-dependent oxidase, reducing cortisol activity by converting it to the inactivate metabolite cortisone (24). Previous study has indicated that hsd11b2 mRNA levels in the ovarian follicles of zebrafish are upregulated in response to elevated cortisol stimulation in vitro (11). Therefore, we utilized hsd11b2 mRNA as an indicator of ovary cortisol level in vivo. The results showed that the expression of hsd11b2 mRNA in stage IVb (mature) follicles collected at 06:40 (just prior to ovulation), was approximately 3-fold higher than those in stage IVa (immature) follicles collected at 20:00 and 05:00 (Fig. 1D).

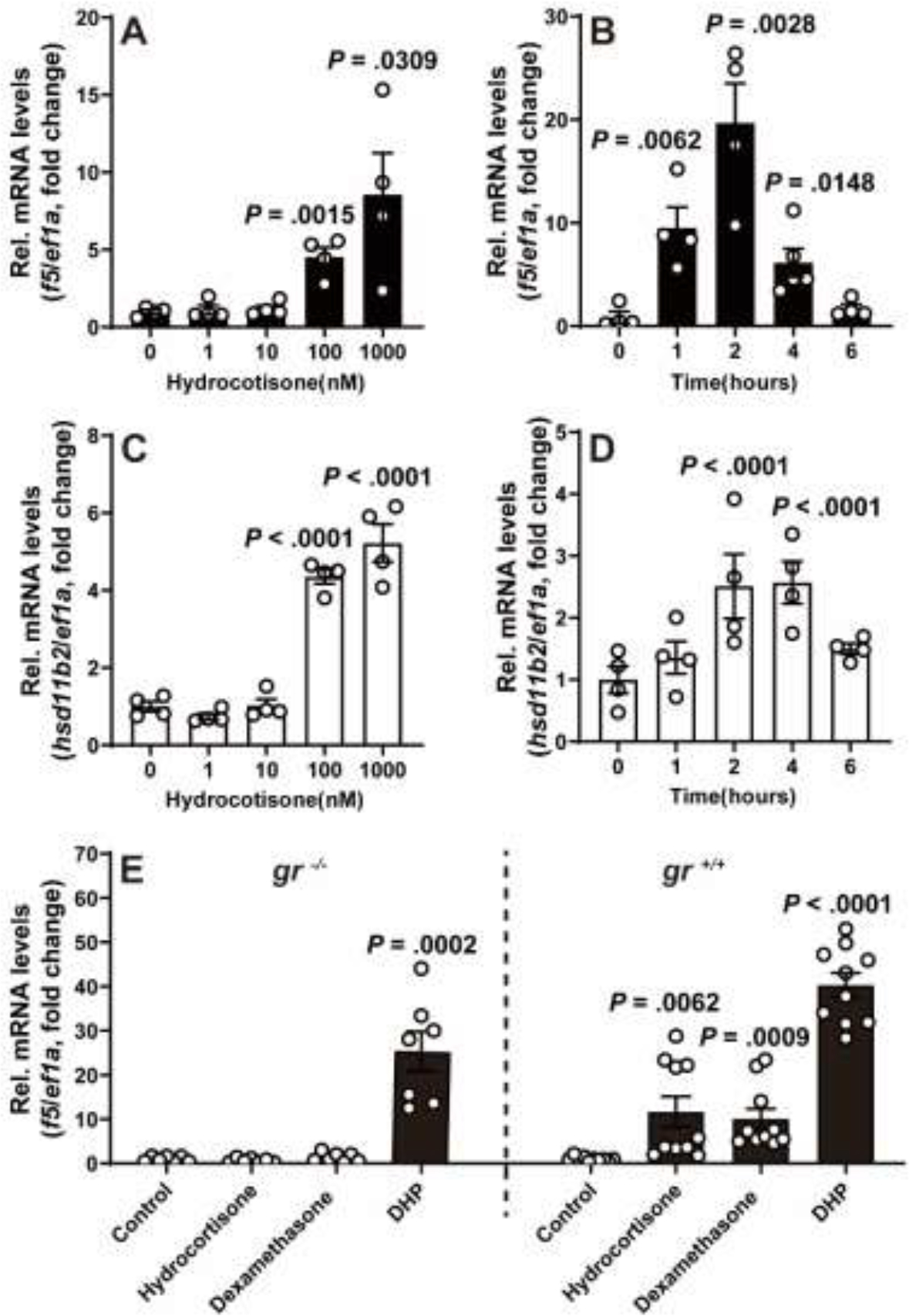

3.2. Transcripts of f5 were upregulated by hydrocortisone in preovulatory follicles in vitro

Hydrocortisone is a well-established native ligand for Gr in zebrafish (25). We observed a dose- and time-dependent the increase of f5 transcripts in stage IVa follicles exposed to external hydrocortisone (Fig. 2). Transcripts of f5 showed a significant increase in stage IVa follicles when incubated with 100 nM hydrocortisone for 2 hours in vitro, further escalating with 1000 nM hydrocortisone (Fig. 2A). The f5 mRNA level rose significantly after 1 hour exposure to 100 nM hydrocortisone, peaked around 2 hours, and then declined at 4 and 6 hours (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Transient increase of f5 and hsd11b2 mRNA expression in preovulatory follicles in response to stimulation of hydrocortisone in vitro.

A-D, Expression levels of f5 (A, B) and hsd11b2 (C, D) mRNA in response to treatment with various doses of hydrocortisone (2 hours exposure) (A, C), and hydrocortisone (100 nM) at various time points (B, D) in preovulatory follicles (IVa) in vitro. E, Effect of hydrocortisone (100 nM), dexamethasone (100 nM), and DHP (10 nM) on f5 expression in the mutants (gr−/−, left side of C panel) or their gr+/+ siblings (right side of C panel). The relative expression of f5 mRNA was determined by qPCR and normalized to an internal control (ef1α). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N ≥ 3) relative to the respective transcript levels of target gene measured in 0 time point or vehicle treatment group. P values were calculated by Student’s unpaired t test against respective controls (0 time point or vehicle treatment group).

Glucocorticoids exert their effect mainly through the GR but also could via mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). To determine the receptor responsible for the hydrocortisone-induced upregulation of f5 mRNA levels in preovulatory follicles, hsd11b2, a Gr-responsive gene, was employed as a positive control. As expected, the expression pattern of hsd11b2 mRNA is similar to that of f5 mRNA (Fig. 2C, D). To further validate, the stage IVa follicles collected from gr−/− were treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) or DHP (10 nM) for 2 hours. As a positive control, DHP was able to significantly increase f5 transcripts in stage IVa follicles regardless whether these follicles were from both gr−/− or gr+/+ fish due to the presence of Pgr (Fig. 2E). However, no significant change of f5 transcript was observed in stage IVa follicles from gr−/− fish exposed to hydrocortisone or dexamethasone was able to significantly increase f5 transcripts in stage IVa follicles from gr+/+ fish (Fig. 2E).

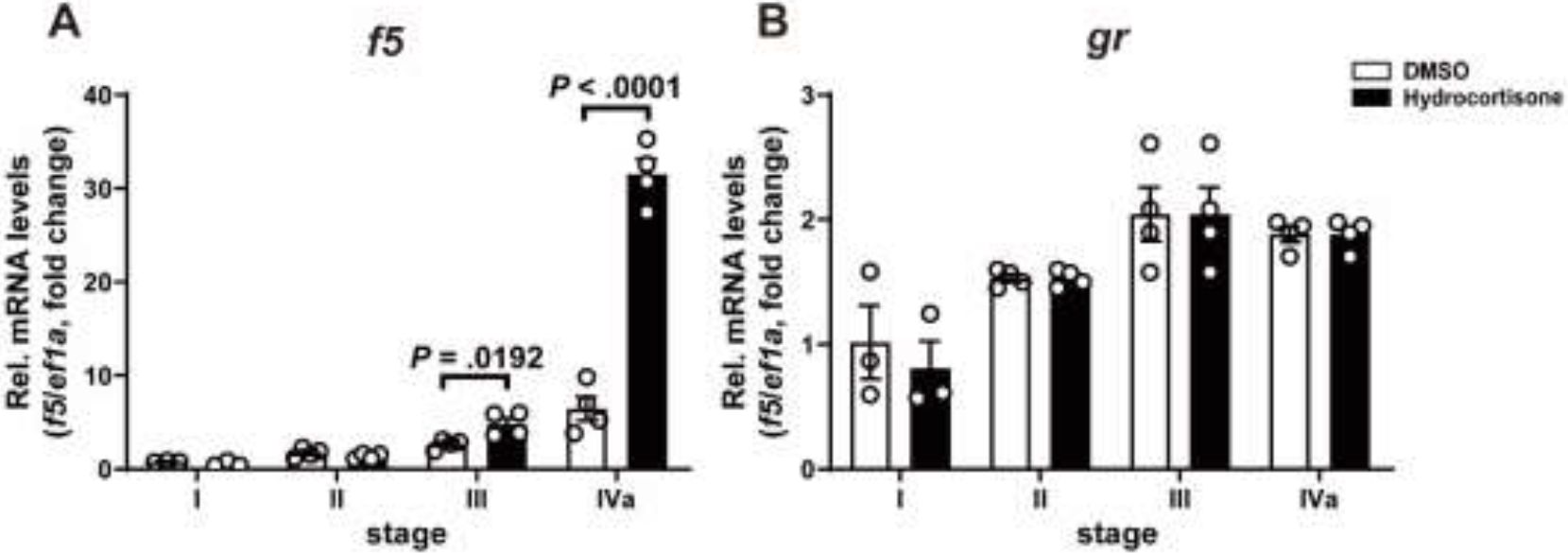

3.3. Transcripts of f5 showed stage-specific response to hydrocortisone in ovarian follicles in vitro

Hydrocortisone markedly increased f5 expression in vitellogenesis follicles (III) and exhibited its most potent stimulatory effects on fully grown immature follicles (IVa) (Fig. 3A). The expression of gr mRNA exhibited variations but did not show significant difference during folliculogenesis whether stimulated with hydrocortisone or not (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Transcripts of f5 showed stage-specific response to hydrocortisone in ovarian follicles.

Follicles at different stages were incubated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) for 2 hours in vitro, with DMSO treatment as the control group. The relative expression of f5 (A) or gr (B) mRNA expression was determined by qPCR and normalized to an internal control (ef1α). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 3) relative to the transcript levels of the target gene measured in the follicle at stage I with DMSO treatment. P values were calculated by Student’s unpaired t test.

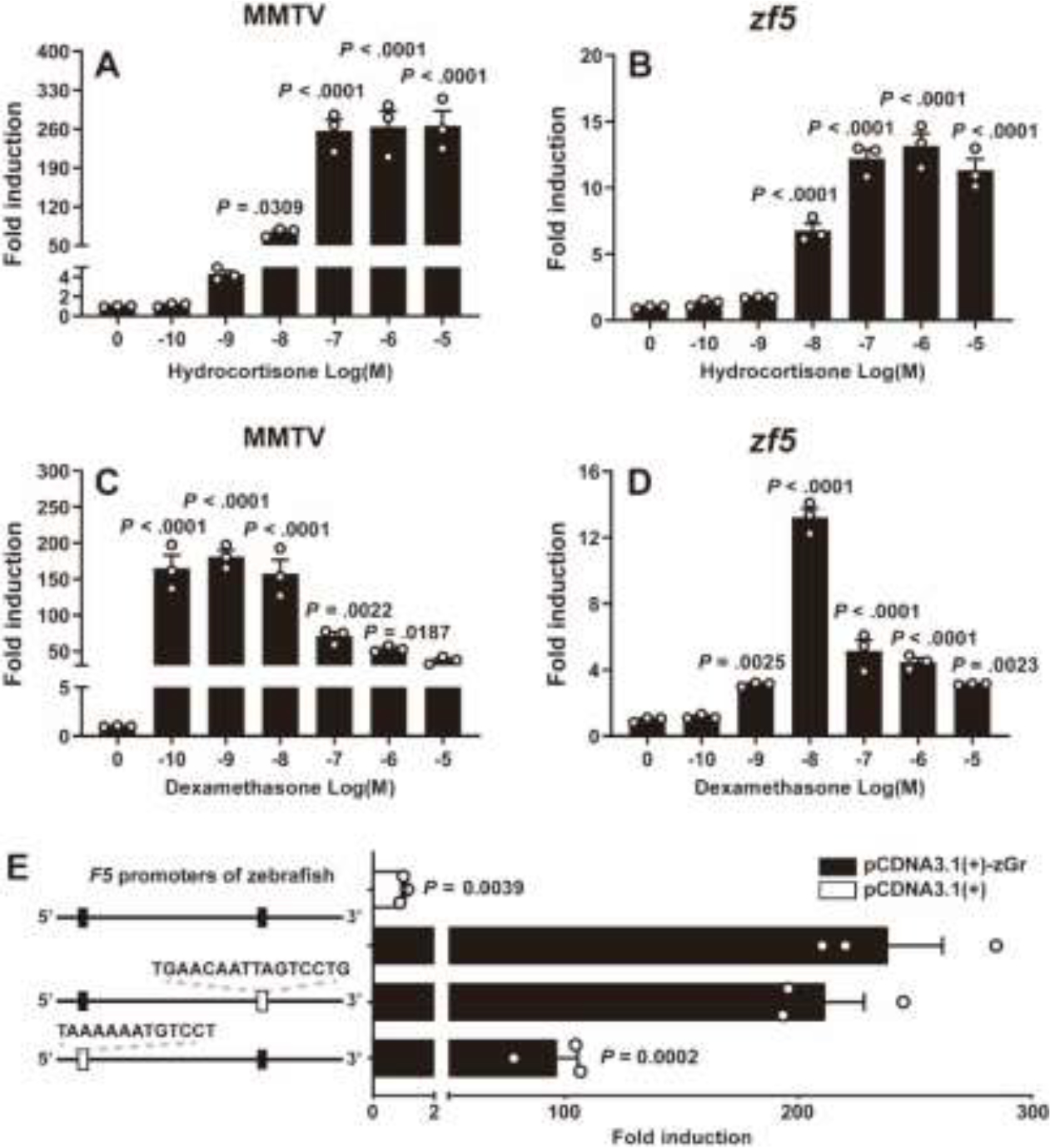

3.4. Glucocorticoids modulate promoter activities of f5 via glucocorticoid receptor

We used a dual-luciferase reporter assay to investigate the presence of GREs within the f5 promoter sequence and to determine whether glucocorticoids could directly activate these GREs through Gr. As a control, a reporter vector containing a mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter with known GREs was utilized (26). Hydrocortisone and dexamethasone were native ligands and specific agonists for zebrafish Gr, respectively (Fig. 4A, B). In the presence of Gr, hydrocortisone notabtly increased the f5 promoter activities in a dose-dependent pattern (Fig. 4C). Differently, the f5 promoter activities significantly increased and peaked at 10−8 M dexamethasone, but decreased at 10−7 to 10−5 M (Fig. 4D). A total of six potential GREs was identified in upstream (−2081/+46) of the zebrafish f5 gene (Supplemental Table 4). Given the similarity between the DNA sequences that bind to Gr and Pgr, we focused on two potential GREs that also functioned as potential PREs (16). Subsequently, we conducted site-directed mutagenesis to examined these two putative GRE/PREs in the f5 promoter region (Fig. 4E). The results indicated that a GRE/PRE (5’-TAAAAAATGTCCT-3’) located at −1438 to −1425 of zebrafish f5 appears to be the primary mediator of Gr regulation. (Fig. 4E)

Figure 4. Glucocorticoids enhance promoter activity of f5 via Gr.

HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter vector containing putative Gr binding elements, a pRL-TK vector containing the Renilla luciferase reporter gene (as a control for transfection efficiency), and a Gr expression vector. In the presence of zebrafish Gr (zGr), both hydrocortisone (A, B) and dexamethasone (C, D) significantly increased the activities of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) and zebrafish f5 promoter. E, Site-directed mutagenesis of two likely GREs decreased the zf5 promoter activity. HEK293T cells were incubated for 24 hours with increasing concentrations of glucocorticoids (hydrocortisone or dexamethasone: 100 pM to 1 μM). Luciferase activity was then assayed in cell extracts. Values are shown relative to the luciferase activity of the vehicle treatment group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 3). P values were calculated by one-tailed, one-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett test against respective controls (vehicle controls or 0 dose).

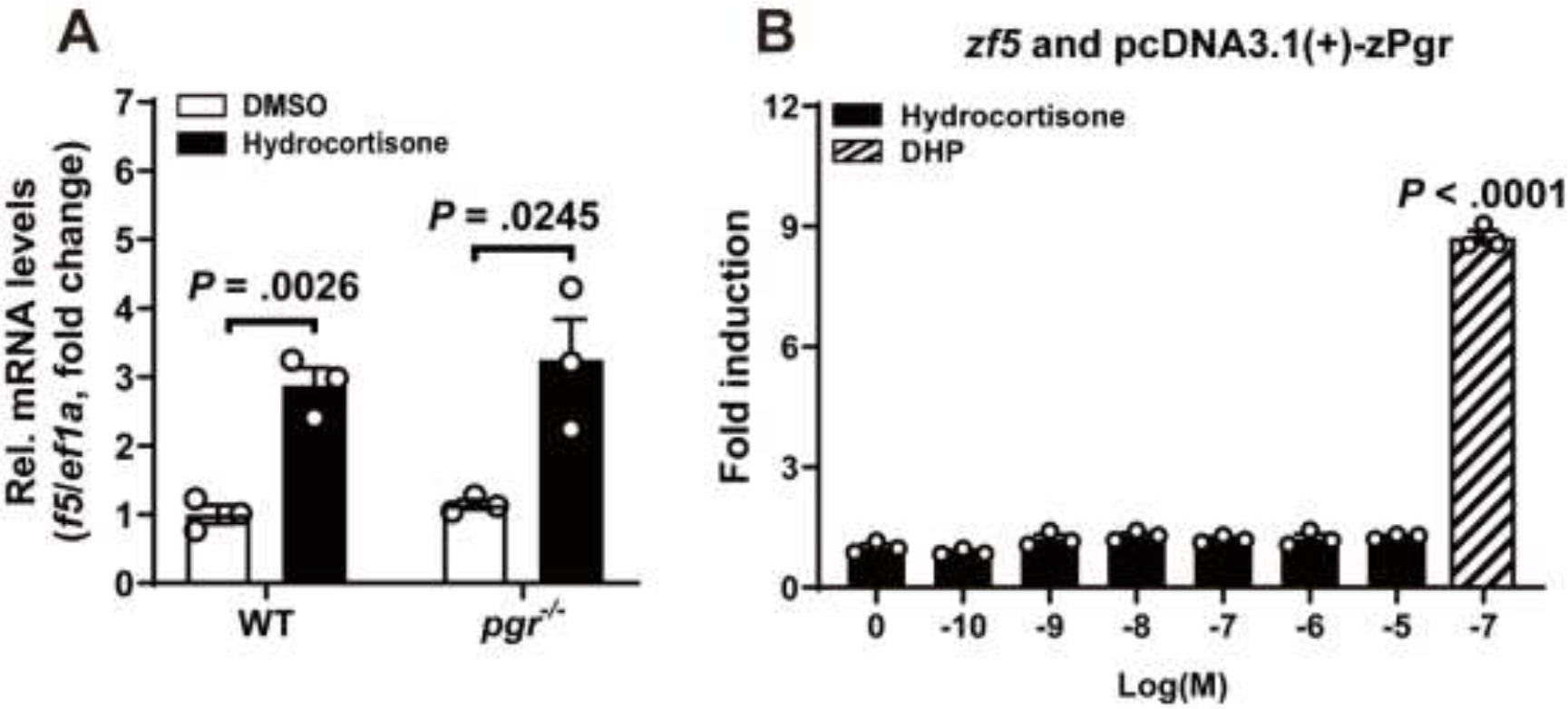

3.5. Hydrocortisone-induced upregulation of f5 mRNA levels independent of Pgr in preovulatory follicles

GR and PGR belong to a subfamily of nuclear receptor superfamily with similar structural domains, and overlapping ligand binding specificities (27). It has been reported that glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid cross-talk with PGR to produce progesterone-like effects (28). To determine whether the upregulation of f5 induced by glucocorticoid is mediated through Pgr, ovarian follicles collected from pgr−/− were treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) for 2 hours. Our results indicated that hydrocortisone was able to induce similar levels of f5 expression in stage IVa follicles from pgr−/− fish as those from wildtype control (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, results from dual-luciferase reporter assay suggested that hydrocortisone-induced f5 expression is likely mediated through Gr (Fig. 4). No promoter activity of f5 via Pgr was observed when stimulated by hydrocortisone (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Hydrocortisone-induced upregulation of f5 mRNA independent of Pgr.

A, Hydrocortisone upregulated the expression of f5 mRNA in the stage IVa follicles from pgr−/− mutants. Stage IVa follicles (from WT and pgr−/− zebrafish) were incubated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) for 2 hours in vitro. The expression of f5 transcript was determined by qPCR and normalized to an internal control (ef1α). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (N = 3) relative to the transcript levels of target gene measured in the vehicle treatment group. P values were calculated by Student’s unpaired t test.

B, Hydrocortisone did not enhance promoter activity of f5 via Pgr. HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter vector containing zebrafish f5 promoter, a pRL-TK vector containing the Renilla luciferase reporter gene (as a control for transfection efficiency), and a Pgr expression vector. After 24 hours of incubation with increasing concentrations of hydrocortisone (100 pM to 10 μM) or DHP (100 nM), luciferase activity was assayed in the HEK293T cell extracts. The values are shown relative to the luciferase activity of the vehicle treatment group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N = 3). P values were calculated by one-tailed, one-way analysis of variance followed by the Dunnett test against vehicle treatment control. P values were calculated by Student’s unpaired t test.

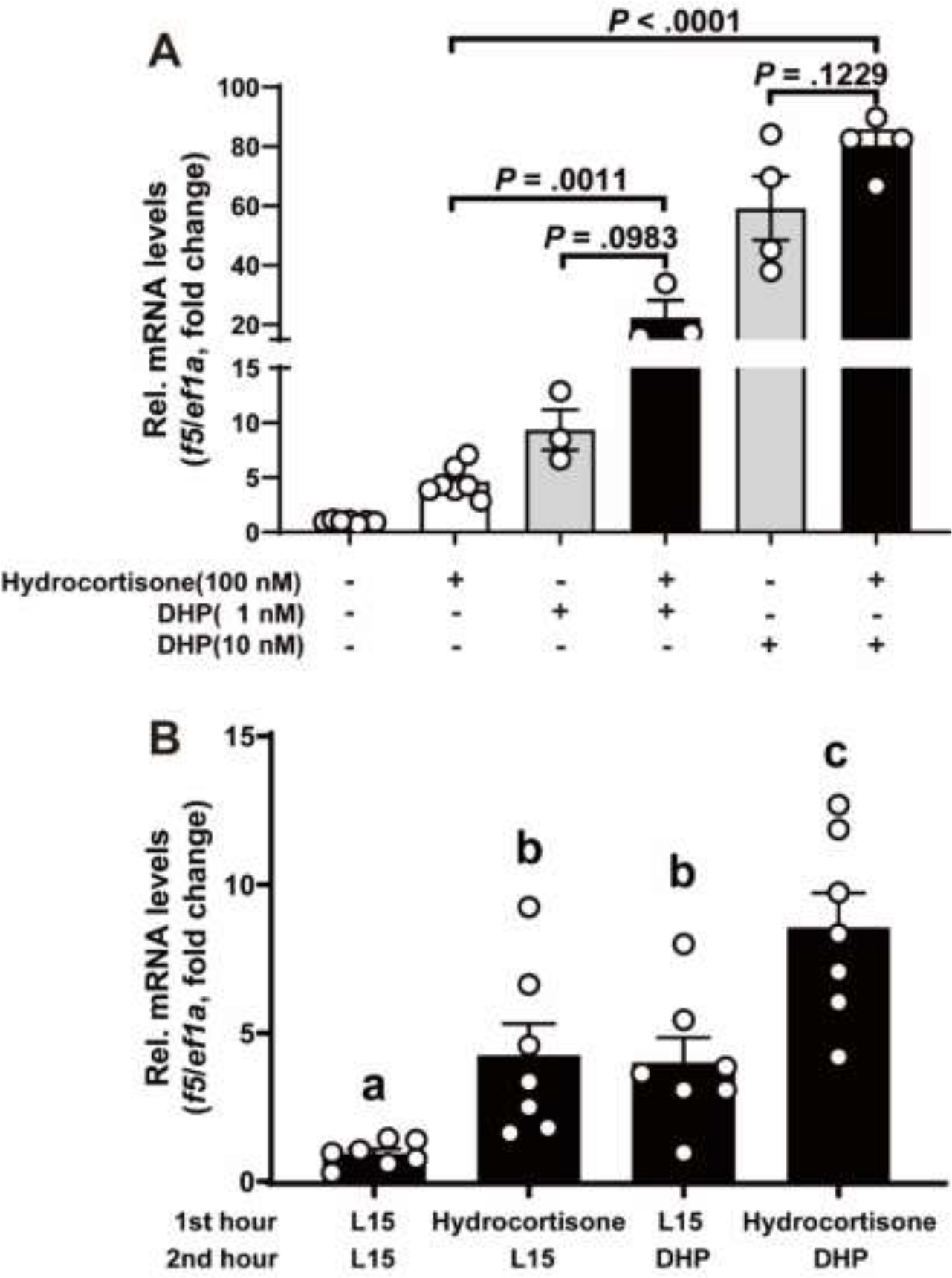

3.6. Co-incubation of hydrocortisone and DHP enhanced f5 expression in preovulatory follicles

Our previous study demonstrated that DHP, a native ligand of zebrafish Pgr, markedly increased the expression of f5 mRNA in preovulatory follicles. Consequently, we sought to investigate the potential combined effect of hydrocortisone with DHP on the expression of f5 mRNA. Our results indicated that the expression levels of f5 mRNA in stage IVa follicles treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM) and DHP (1 or 10 nM) together for 2 hours were significantly higher than those follicles treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM, 2 hours), but not significant different from those treated with DHP (1 or 10 nM, 2 hours) alone (Fig. 6A). Intriguingly, the expression levels of f5 mRNA in the stage IVa follicles treated successively with hydrocortisone (100 nM for 1 hour) and DHP (10 nM for 1 hour) were significantly higher than those follicles treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM, 1 hour) and DHP (10 nM, 1 hour) alone (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of co-incubation of hydrocortisone and DHP on the f5 mRNA expression in preovulatory follicles.

A, Stage IVa follicles were incubated with hydrocortisone (100 nM), and DHP (1nM or 10nM) alone or together for 2 hours. B, stage IVa follicles were treated successively treated with hydrocortisone (100 nM for 1 hour) and DHP (10 nM for 1 hour). The expression of f5 transcript was determined by qPCR and normalized to an internal control (ef1α). Data are presented as mean ± SEM (N ≥ 3) relative to the transcript levels of target gene measured in the vehicle treatment group. P values were calculated by Student’s unpaired t test (A). Different letters on the bar indicated significant differences between each other (P < 0.05, Student’s unpaired t test) (B).

4. Discussion

The ovulation process involves a dramatic remodeling, which shares several features with inflammatory responses. Studies have demonstrated elevated levels of cortisol in the follicular fluid of pre-ovulatory women (29–31). As an anti-inflammatory hormone, it is reasonable to assume that cortisol may play a balancing role in response to inflammatory mediators during ovulation, thereby protecting the ovary from damage while facilitating rapid tissue repair post-ovulation in women(3). Previous studies in fish have suggested a potential contribution of corticosteroids to ovulation, with significant increases in corticosteroid levels observed during this stage (13,24,32,33). Despite this, the specific role of cortisol in ovulation has received limited attention. Here, we present evidence of a mechanism wherein hydrocortisone induces the upregulation of f5 expression in preovulatory follicles via Gr.

The present study found no clear daily variation in cortisol levels in the ovary. However, we observed a significant difference in ovary weight and the total amount of cortisol per ovary between samples collected at 05:00 and 06:40. Given that oocyte maturation is the major ovarian process during this period in zebrafish, the slight but significant increase in ovary weight is likely attributed to oocyte hydration (water uptake) (34). In addition, the significant increase in the total amount of cortisol per ovary may be due to the contribution of cortisol produced in stage IV follicles during oocyte maturation. As zebrafish have asynchronous ovaries containing follicles of all stages of developmental stages, we specifically examined the expression levels of hsd11b2 mRNA in stage IV follicles. The results confirmed our hypothesis that cortisol was produced in stage IV follicles prior to ovulation in zebrafish. The increase in cortisol production, along with hydration, in stage IV follicles during the maturation process may explain the lack of clear variation in cortisol concentration in the ovary during this period.

Progestin and PGR are well-established master regulators for ovulation in vertebrates (17,18). Our previous studies have demonstrated that f5 is a sensitive and early indicator, dramatically induced by progestin via a Pgr-dependent mechanism in preovulatory follicles in zebrafish (16). Furthermore, coagulation, possibly induced by F5, is required for ovulation and female fertility, in addition to its role in hemostasis (35). Evidence has indicated that corticosteroids participate in regulating ovulation in fish (12,13). In most teleost species, circulating cortisol levels are typically <10 ng/ml. Notably, rainbow trout exhibited a several-fold increases in cortisol (26–32 ng/ml) during the spawning period (32). Zebrafish have been observed to maintain whole-body cortisol levels at 30–40 ng/g body mass (11,36), with cortisol content in the ovaries ranging from ~22 ng/g tissue mass (11) to 30–80 ng/g tissue mass based on the current study. Our results demonstrated that hydrocortisone, at a concentration of 100 nM (36.2 ng/ml), which is in the range of elevated cortisol levels found in zebrafish, could significantly increase the expression level of f5 mRNA. This suggests that elevated cortisol may induce f5 expression in preovulatory follicles during spawning, leading to coagulation and ovulation.

In the present study, we detected the upregulation of f5 mRNA in response to hydrocortisone, consistent with our previous finding that such upregulation in response to progestin (DHP) treatment, which was observed only in late-stage follicles (III and IVa) but not in early-stage follicles (I and II). Similarly, the expression pattern of hsd11b2, a Gr-response gene in zebrafish ovary (11), exhibited a clear response after hydrocortisone treatment, confirming hydrocortisone-induced upregulation of f5 mRNA is mediated by Gr. Differences in response to hydrocortisone in different follicular stages may be attributed to factors such as the availability of Gr binding sites and/or methylation of Gr binding sites in the f5 regulatory region. An increase in plasma cortisol is typically observed prior to the increase of DHP during ovulation (37). Therefore, to mimic this pattern, the preovulatory follicles were successively treated with hydrocortisone and DHP. The results revealed that such sequential treatment exhibited a stronger stimulation effect on f5 mRNA expression compared to treatment with hydrocortisone or DHP alone. These findings indicated that cortisol’s transcriptional activities may prime late-stage follicles to be prepared to respond to the progestin-Pgr signaling prior to ovulation.

The steroid receptors’ role in crosstalk is becoming increasingly relevant, although the involved mechanisms are still debated (38,39). In our previous study, f5 was identified as a sensitive Pgr-target gene in the preovulatory ovarian follicles cells of zebrafish (16). In the present study, the successive treatment of hydrocortisone and DHP demonstrated a stronger effect on the upregulating of f5 mRNA compared to hydrocortisone alone, suggesting functional crosstalk between Gr and Pgr. Unlike the functional connection between GR and estrogen receptor (ER) (40–42), few studies have addressed the influence of GR on PGR’s transcriptional activity or vice versa. In PGR+/GR+ breast cancer cell lines, ChIP-seq and sequential ChIP analyses revealed the overlapped binding of GR and PGR at key enhancer sites and confirmed co-recruitment of both receptors to shared sites, supporting the existence of PGR-GR heterocomplexes (43). In the present study, we identified two shared Pgr/Gr binding sites in the promoter sequence of the F5 gene. The results from previous and current studies indicated that a Gr/Pgr response element sequence (5’-TAAAAAATGTCCT-3’) localized at −1438 to −1425 of zebrafish f5 promoter appears to be the primary mediator of both Gr and Pgr regulation. Higher oligomerization states have been described for both PGR and GR (44). It is possible that Gr and Pgr in follicle cells may form transcriptional active heterocomplexes to enhance the upregulation of f5. However, a direct physical interaction needs to be confirmed in future studies.

Glucocorticoids, due to their potent anti-inflammatory effects, are among the most widely prescribed drugs for treating inflammatory diseases. However, these hormones have adverse effects that lead to thromboembolic events (45–49). A typical clinic model of glucocorticoid-induced hypercoagulability is represented by endogenous Cushing’s syndrome, characterized by prolonged exposure to excessive cortisol secretion due to factors such as excessive adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) production from a pituitary tumor, ectopic ACTH or excessive cortisol secretion from an adrenocortical tumor (50). The hypercoagulable state in Cushing’s syndrome is mediated by increased levels of procoagulant factors and an impaired fibrinolytic capacity (51). In hypercortisolemic patients, there is a confirmed trend toward increased serum concentrations of coagulation factors V, VIII, von Willebrand factor (vW), IX, and XI (52,53). However, evidence of glucocorticoid-induced coagulation factors is lacking. It is generally accepted that liver is the principal site of F5 biosynthesis (54). Nevertheless, F5 is also present in vascular-related cells, such as platelets and monocytes (55,56). Our recent study demonstrated that the follicle layer in the preovulatory ovarian follicle is a new extrahepatic site of f5 expression in zebrafish (16). Given the widespread expression of GR in human tissues, the hypercoagulability associated with Cushing’s syndrome may be due to prolonged exposure to excessive cortisol levels, which could induce the expression of F5.

In summary, our results demonstrate that f5 mRNA expression is induced by hydrocortisone through a Gr-dependent mechanism in preovulatory follicles. Furthermore, the successive incubation of cortisol and progestin enhanced f5 expression, suggesting that cortisol has an additive effect on the DHP-Pgr signaling pathway-induced coagulation factor and consequently ovulation. It is also plausible that long-term exposure to hydrocortisone may lead to ovarian dysfunction. Future studies on the regulation and functions of glucocorticoid-induced coagulation factors in other organs (such as the swim bladder, a homologous organ of lungs) and in other species, including mammals and humans, are likely to have substantial clinical implications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Total amount of cortisol per ovary significantly increases during oocyte maturation.

hydrocortisone stimulates f5 mRNA level in preovulatory follicles via Gr.

A Gr response element (GRE) was identified in the promoter of zebrafish f5.

Successive incubation of hydrocortisone and DHP enhances f5 mRNA levels.

Acknowledgment:

We want to thank Dr. Karl J Clark (Mayo Clinic) for providing gr knockout (gr−/−) zebrafish.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41976092 to SXC; No. 32302998 to JH), Youth Science and Technology Innovation Program of Xiamen Ocean and Fisheries Development Special Funds (No. 23YYST074QCB34 to SXC), and NIH HD109785 to YZ.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duffy DM, Ko C, Jo M, Brannstrom M, Curry TE. Ovulation: Parallels With Inflammatory Processes. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(2):369–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramamoorthy S, Cidlowski JA. Corticosteroids Mechanisms of Action in Health and Disease. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America. 2016;42(1):15-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillier SG, Tetsuka M. An anti-inflammatory role for glucocorticoids in the ovaries? J Reprod Immunol. 1998;39(1–2):21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeon H, Choi Y, Brannstrom M, Akin JW, Curry TE, Jo M. Cortisol/glucocorticoid receptor: a critical mediator of the ovulatory process and luteinization in human periovulatory follicles. Hum Reprod. 2023;38(4):671–685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caimari F, Valassi E, Garbayo P, Steffensen C, Santos A, Corcoy R, Webb SM. Cushing’s syndrome and pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review of published cases. Endocrine. 2017;55(2):555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lado-Abeal J, Rodriguez-Arnao J, Newell-Price JDC, Perry LA, Grossman AB, Besser GM, Trainer PJ. Menstrual abnormalities in women with Cushing’s disease are correlated with hypercortisolemia rather than raised circulating androgen levels. J Clin Endocr Metab. 1998;83(9):3083–3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsilchorozidou T, Honour JW, Conway GS. Altered cortisol metabolism in polycystic ovary syndrome: Insulin enhances 5 alpha-reduction but not the elevated adrenal steroid production rates. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2003;88(12):5907–5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faught E, Santos HB, Vijayan MM. Loss of the glucocorticoid receptor causes accelerated ovarian ageing in zebrafish. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2020;287(1940). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maradonna F, Gioacchini G, Notarstefano V, Fontana CM, Citton F, Dalla Valle L, Giorgini E, Carnevali O. Knockout of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Impairs Reproduction in Female Zebrafish. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao HS, Xu Z, Zhu X, Wang JR, Zheng QY, Zhang QQ, Xu CM, Tao WJ, Wang DS. Cortisol safeguards oogenesis by promoting follicular cell survival. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65(8):1563–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faught E, Best C, Vijayan MM. Maternal stress-associated cortisol stimulation may protect embryos from cortisol excess in zebrafish. Roy Soc Open Sci. 2016;3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang QF, Ye D, Wang HP, Wang YQ, Hu W, Sun YH. Knockout Reveals the Roles of 11-ketotestosterone and Cortisol in Sexual Development and Reproduction. Endocrinology. 2020;161(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faught E, Vijayan MM. Maternal stress and fish reproduction: The role of cortisol revisited. Fish Fish. 2018;19(6):1016–1030. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Milla S, Wang N, Mandiki SNM, Kestemont P. Corticosteroids: Friends or foes of teleost fish reproduction? Comp Biochem Phys A. 2009;153(3):242–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cripe LD, Moore KD, Kane WH. Structure of the Gene for Human Coagulation Factor-V. Biochemistry-Us. 1992;31(15):3777–3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Sun C, Teng Liu D, Zhao NN, Shavit JA, Zhu Y, Chen SX. Nuclear Progestin Receptor-mediated Linkage of Blood Coagulation and Ovulation. Endocrinology. 2022;163(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lydon JP, Demayo FJ, Funk CR, Mani SK, Hughes AR, Montgomery CA, Shyamala G, Conneely OM, Omalley BW. Mice Lacking Progesterone-Receptor Exhibit Pleiotropic Reproductive Abnormalities. Gene Dev. 1995;9(18):2266–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, Liu D, Shaner ZC, Chen S, Hong W, Stellwag EJ. Nuclear progestin receptor (pgr) knockouts in zebrafish demonstrate role for pgr in ovulation but not in rapid nongenomic steroid mediated meiosis resumption. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2015;6:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai MJ, Omalley BW. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Steroid/Thyroid Receptor Superfamily Members. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1994;63:451–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan YH, Nordeen SK. Overlapping but distinct gene regulation profiles by glucocorticoids and progestins in human breast cancer cells. Molecular Endocrinology. 2002;16(6):1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strahle U, Klock G, Schutz G. A DNA-Sequence of 15 Base-Pairs Is Sufficient to Mediate Both Glucocorticoid and Progesterone Induction of Gene-Expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84(22):7871–7875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von der Ahe D, Janich S, Scheidereit C, Renkawitz R, Schutz G, Beato M. Glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors bind to the same sites in two hormonally regulated promoters. Nature. 1985;313(6004):706–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HB, Schwab TL, Sigafoos AN, Gauerke JL, Krug RG 2nd, Serres MR, Jacobs DC, Cotter RP, Das B, Petersen MO, Daby CL, Urban RM, Berry BC, Clark KJ. Novel zebrafish behavioral assay to identify modifiers of the rapid, nongenomic stress response. Genes Brain Behav. 2019;18(2):e12549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mommsen TP, Vijayan MM, Moon TW. Cortisol in teleosts: dynamics, mechanisms of action, and metabolic regulation. Rev Fish Biol Fisher. 1999;9(3):211–268. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaaf MJM, Chatzopoulou A, Spaink HP. The zebrafish as a model system for glucocorticoid receptor research. Comp Biochem Phys A. 2009;153(1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hager GL, Richardfoy H, Kessel M, Wheeler D, Lichtler AC, Ostrowski MC. The Mouse Mammary-Tumor Virus Model in Studies of Glucocorticoid Regulation. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 1984;40:121–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornton JW. Evolution of vertebrate steroid receptors from an ancestral estrogen receptor by ligand exploitation and serial genome expansions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(10):5671–5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leo JCL, Guo CH, Woon CT, Aw SE, Lin VCL. Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid cross-talk with progesterone receptor to induce focal adhesion and growth inhibition in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145(3):1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fateh M, Benrafael Z, Benadiva CA, Mastroianni L, Flickinger GL. Cortisol-Levels in Human Follicular-Fluid. Fertil Steril. 1989;51(3):538–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harlow CR, Jenkins JM, Winston RML. Increased follicular fluid total and free cortisol levels during the luteinizing hormone surge. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(1):48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannsen ML, Poulsen LC, Mamsen LS, Grøndahl ML, Englund ALM, Lauritsen NL, Carstensen EC, Styrishave B, Yding Andersen C. The intrafollicular concentrations of biologically active cortisol in women rise abruptly shortly before ovulation and follicular rupture. Hum Reprod. 2024;39(3):578–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bry C Plasma-Cortisol Levels of Female Rainbow-Trout (Salmo-Gairdneri) at the End of the Reproductive-Cycle - Relationship with Oocyte Stages. Gen Comp Endocr. 1985;57(1):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barton BA. Stress in fishes: A diversity of responses with particular reference to changes in circulating corticosteroids. Integr Comp Biol. 2002;42(3):517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cerdà J, Fabra M, Raldúa D. Physiological and molecular basis of fish oocyte hydration. In: Babin PJ, Cerdà J, Lubzens E, eds. The Fish Oocyte: From Basic Studies to Biotechnological Applications. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2007:349–396. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pikulkaew S, Benato F, Celeghin A, Zucal C, Skobo T, Colombo L, Dalla Valle L. The knockdown of maternal glucocorticoid receptor mRNA alters embryo development in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(4):874–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abdollahpour H, Falahatkar B, Jafari N, Lawrence C. Effect of stress severity on zebrafish (Danio rerio) growth, gonadal development and reproductive performance: Do females and males respond differently? Aquaculture. 2020;522. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clelland E, Peng C. Endocrine/paracrine control of zebrafish ovarian development. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;312(1–2):42–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dhiman VK, Bolt MJ, White KP. Nuclear receptors in cancer - uncovering new and evolving roles through genomic analysis. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2018;19(3):160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pecci A, Ogara MF, Sanz RT, Vicent GP. Choosing the right partner in hormone-dependent gene regulation: Glucocorticoid and progesterone receptors crosstalk in breast cancer cells. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karmakar S, Jin YT, Nagaich AK. Interaction of Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) with Estrogen Receptor (ER) alpha and Activator Protein 1 (AP1) in Dexamethasone-mediated Interference of ER alpha Activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(33):24020–24034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miranda TB, Voss TC, Sung MH, Baek S, John S, Hawkins M, Grontved L, Schiltz RL, Hager GL. Reprogramming the Chromatin Landscape: Interplay of the Estrogen and Glucocorticoid Receptors at the Genomic Level. Cancer Research. 2013;73(16):5130–5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West DC, Pan D, Tonsing-Carter EY, Hernandez KM, Pierce CF, Styke SC, Bowie KR, Garcia TI, Kocherginsky M, Conzen SD. GR and ER Coactivation Alters the Expression of Differentiation Genes and Associates with Improved ER+ Breast Cancer Outcome. Molecular Cancer Research. 2016;14(8):707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogara MF, Rodriguez-Segui SA, Marini M, Nacht AS, Stortz M, Levi V, Presman DM, Vicent GP, Pecci A. The glucocorticoid receptor interferes with progesterone receptor-dependent genomic regulation in breast cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2019;47(20):10645–10661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Presman DM, Ganguly S, Schiltz RL, Johnson TA, Karpova TS, Hager GL. DNA binding triggers tetramerization of the glucocorticoid receptor in live cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113(29):8236–8241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular disease. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2007;157(5):545–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Zaane B, Nur E, Squizzato A, Gerdes VEA, Buller HR, Dekkers OM, Brandjes DPM. Systematic review on the effect of glucocorticoid use on procoagulant, anti-coagulant and fibrinolytic factors. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2010;8(11):2483–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coelho MCA, Santos CV, Neto LV, Gadelha MR. Adverse effects of glucocorticoids: coagulopathy. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2015;173(4):M11–M21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodwin JE. Glucocorticoids and the Cardiovascular System. Glucocorticoid Signaling: From Molecules to Mice to Man. 2015;872:299–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oray M, Abu Samra K, Ebrahimiadib N, Meese H, Foster CS. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2016;15(4):457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(9996):913–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Pas R, Leebeek FWG, Hofland LJ, de Herder WW, Feelders RA. Hypercoagulability in Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence, pathogenesis and treatment. Clinical Endocrinology. 2013;78(4):481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Pas R, de Bruin C, Leebeek FWG, de Maat MPM, Rijken DC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Netea-Maier RT, Hermus AR, Zelissen PMJ, de Jong FH, van der Lely AJ, de Herder WW, Lamberts SWJ, Hofland LJ, Feelders RA. The Hypercoagulable State in Cushing’s Disease Is Associated with Increased Levels of Procoagulant Factors and Impaired Fibrinolysis, But Is Not Reversible after Short-Term Biochemical Remission Induced by Medical Therapy. J Clin Endocr Metab. 2012;97(4):1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kastelan D, Dusek T, Kraljevic I, Polasek O, Giljevic Z, Solak M, Salek SZ, Jelcic J, Aganovic I, Korsic M. Hypercoagulability in Cushing’s syndrome: the role of specific haemostatic and fibrinolytic markers. Endocrine. 2009;36(1):70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson DB, Salem HH, Mruk JS, Maruyama I, Majerus PW. Biosynthesis of coagulation Factor V by a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. J Clin Invest. 1984;73(3):654–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chesney CM, Pifer D, Colman RW. Subcellular localization and secretion of factor V from human platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(8):5180–5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kappelmayer J, Kunapuli SP, Wyshock EG, Colman RW. Characterization of Monocyte-Associated Factor-V. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 1993;70(2):273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.