Abstract

Advances in fetal brain neuroimaging, especially fetal neurosonography and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), allow safe and accurate anatomical assessments of fetal brain structures that serve as a foundation for prenatal diagnosis and counseling regarding fetal brain anomalies. Fetal neurosonography strategically assesses fetal brain anomalies suspected by screening ultrasound. Fetal brain MRI has unique technological features that overcome the anatomical limits of smaller fetal brain size and the unpredictable variable of intrauterine motion artifact. Recent studies of fetal brain MRI provide evidence of improved diagnostic and prognostic accuracy, beginning with prenatal diagnosis. Despite technological advances over the last several decades, the combined use of different qualitative structural biomarkers has limitations in providing an accurate prognosis. Quantitative analyses of fetal brain MRIs offer measurable imaging biomarkers that will more accurately associate with clinical outcomes. First-trimester ultrasound opens new opportunities for risk assessment and fetal brain anomaly diagnosis at the earliest time in pregnancy. This review includes a case vignette to illustrate how fetal brain MRI results interpreted by the fetal neurologist can improve diagnostic perspectives. The strength and limitations of conventional ultrasound and fetal brain MRI will be compared with recent research advances in quantitative methods to better correlate fetal neuroimaging biomarkers of neuropathology to predict functional childhood deficits. Discussion of these fetal sonogram and brain MRI advances will highlight the need for further interdisciplinary collaboration using complementary skills to continue improving clinical decision-making following precision medicine principles.

Keywords: Fetal brain anomaly, fetal brain MRI, a single-shot fast spin echo T2 technique, prenatal diagnosis, neurodevelopmental prognosis

Fetal neuroimaging is critical in anatomical diagnosis and neurodevelopmental prognostic counseling regarding brain anomalies. Obstetric ultrasound during routine maternal care across three trimesters screens for possible fetal brain anomalies. Advances in fetal neurosonography enable more precise anatomical assessments of specific fetal brain structures. Fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is presently the highest standard for tissue resolution and anatomical diagnostic accuracy in confirmatory diagnosis. Fetal MRI is available in a high-income countries (HIC) such as the United States, with greater challenges of maternal health care delivery in low to middle-income countries, which contribute to 94% of the world’s children with neurodevelopmental disorders1. This review focuses on neurosonography and fetal brain MRI and their utilization in prenatal diagnosis and counseling of fetal brain anomalies. Through a case, we present the strengths and limitations of fetal brain MRI studies. Current roles of fetal brain MRI for prenatal diagnosis and counseling of fetal brain anomalies, basics and relevant technical features of fetal brain MRI, current clinical evidence of fetal brain MRI, and lastly, the future diagnostic strategies using fetal neurosonography and fetal brain MRI such as first-trimester ultrasound and quantitative analyses of fetal neuroimaging.

Case review

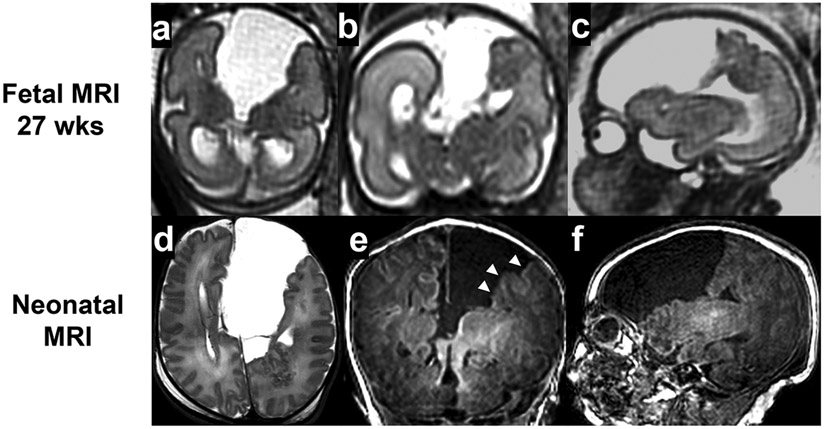

A twenty-one-year-old primigravida was referred to the fetal neurology program given concerns for her singleton fetus who had an interhemispheric cyst in the brain detected during the second-trimester anatomical survey ultrasound performed at 26 weeks’ gestational age (GA). The fetal brain MRI study at 27 weeks (GA) (Fig 1a-c) documented a large left interhemispheric cyst with complete agenesis of the corpus callosum. Irregular cortical margins in the parietal lobe adjacent to the centralized concerns for associated malformations of cortical development involving the left hemisphere. The working differential diagnosis was isolated agenesis or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum with asymmetric ventriculomegaly, interhemispheric cyst, and cortical dysgenesis (AVID). The woman was counseled that children with isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum may have a 15-30% chance of having mild to moderate cognitive or motor impairments6-9. Assuming a diagnosis of AVID, higher risks of impairments were suspected10.

Fig 1.

Case 27 wks interhemispheric cyst

A male infant was born at 38 weeks (GA) with unremarkable physical and neurological examinations. A neonatal brain MRI study (Fig 1d-f) confirmed the above-described anomalies previously diagnosed by fetal brain MRI. Thickened and irregular cortical margins in the left frontal and parietal lobes adjacent to the cyst were also suspected of polymicrogyria. The parents received updated counseling on the child’s increased risks of cognitive or motor impairments and seizures based on the additional findings of complex agenesis of the corpus callosum. Chromosomal microarray and a selected gene panel studies targeted for known brain malformations were negative. The neonatal course was complicated with establishing feeding, re-counseling the future neurodevelopmental prognosis, and organizing home care. The infant received early intervention as well as follow-up with pediatric neurology. At 18 months, the child had macrocephaly, hypertonia, and age-appropriate development. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Changes in diagnosis and prediction of neurodevelopmental prognosis in the case of fetus

| Neuroimaging | Diagnosis | Neurodevelopmental prognosis counseling |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal ultrasound | Interhemispheric cyst | |

| Fetal MRI | Interhemispheric cyst + complete agenesis of corpus callosum | Cognitive or motor impairment (15-30%) Seizures |

| Neonatal MRI | Interhemispheric cyst + complete agenesis of corpus callosum | Increased risks |

The case reiterates the limitations in diagnostic accuracy with challenges based on fetal brain MRI interpretations. The fetal MRI detected agenesis of the corpus callosum, which was not noted on the fetal ultrasound. While associated malformations of cortical development were suspected, these findings remained inconclusive. The neonatal brain MRI later confirmed polymicrogyria in these regions. The neurodevelopmental prognosis subsequently predicted both this child’s motor and cognitive impairments as well as their seizures. Fortunately, the child’s functionally remains developmentally age-appropriate as of 18 months of age. The case reiterates both interpretive and prognostic challenges of fetal brain MRI studies, influencing prenatal and postnatal diagnosis and counseling.

Obstetric ultrasound studies to screen and assess fetal brain anomalies

Obstetric ultrasound studies have been playing central and critical roles in screening and diagnosing fetal central nervous system (CNS) anomalies for over 30 years. Well-established practice guidelines have made generations of iterations to improve the detection and diagnosis of fetal CNS anomalies11,12.

Sonographic screening of fetal CNS anomalies

After a standard anatomical survey, the next step in the evaluation of the fetal brain is the fetal neurosonogram, which is usually performed by an imaging specialist, such as a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist or a neuroradiologist. It is distinguished from anatomical survey in that it is usually performed using transvaginal ultrasonography (if the fetus is in a cephalic presentation) to improve imaging, includes the coronal and sagittal planes, utilizes color Doppler to image cystic structures or vasculature, and includes 3-dimensional ultrasonography (if available) to view planes and reconstructions not available with 2-dimensional imaging. Evaluation of the spine in the axial, coronal, and sagittal views is part of the assessment of the fetal central nervous system.

One of the most recent advanced practice guidelines is ISUOG (International society of ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology) “Practice Guidelines Part 1: performance of screening examination and Indications for targeted neurosonography”11. The guidelines review and update the technical aspects of the screening evaluation of the fetal brain as a part of the midtrimester anomaly scan. It also presents indications for further detailed fetal CNS evaluation by targeted fetal neurosonography.

In the midtrimester (usually described as 18-22 weeks) fetal anomaly scan, the guideline recommends a transabdominal scan of the fetal brain and spine in low-risk pregnancies and transvaginal scan in high-risk pregnancies.

Qualitative assessment includes three planes (transventricular, transcerebellar, transthalamic) of the fetal brain and long sagittal views and axial views of the fetal spine with the following assessment foci – the presence of cavum septum pellucidi, ventricular shape/symmetry, presence and shape of the choroid plexus, presence and shape of the cerebellum and vermis, cisterna magna, thalami, and hippocampal gyri.

Quantitative assessment includes lateral atrial width, transverse cerebellar diameter, and the general fetal cranial/brain biometry (biparietal diameter and head circumference).

For earlier screening (before 18 weeks), the guideline recommends visualization of transventricular and transcerebellar planes. Notably, there is a deficit of clinical guidelines regarding first trimester neurosonography due to technical and knowledge limitations.

The screening sonogram aims to evaluate fetuses with increased risks of fetal CNS anomalies. Fetuses identified with increased risks should undergo targeted fetal neurosonography. Indications for targeted fetal neurosonography include suspicion of CNS malformations at routine screening ultrasound or nuchal translucency scan, positive family history, previous pregnancy with CNS anomaly, a fetus with congenital heart disease, monochorionic twin gestation, suspected congenital intrauterine infection, teratogen exposure, known or suspected aneuploidy, and chromosomal microarray findings of unknown significance. Examples of fetal neurological conditions referred to the maternal fetal medicine specialists and fetal neurology consultations are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Examples of fetal neurological conditions referred to the maternal fetal medicine specialists and fetal neurology consultation

| Developmental anomaly (malformation) | |

|---|---|

| Developmental stage of the primary anomaly | Fetal neurological conditions |

| Neural tube formation | Meningocele, myelomeningocele, encephalocele |

| Midline formation | Absent septum pellucidum, agenesis of corpus callosum, septo-optic dysplasia |

| Neurogenesis/apoptosis | Microcephaly, megalencephaly, tuberous sclerosis, focal cortical dysplasia |

| Neuronal migration | Neuronal migration disorder (lissencephaly, pachygyria, cobble stone malformation, grey matter heterotopia) |

| Post-migrational cortical organization | Polymicrogyria Focal cortical dysplasia |

| Non-developmental anomaly | |

| Infections | Cytomegalovirus, toxoplasma, Zika virus |

| Vascular injury | Cerebral/cerebellar parenchymal hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, ischemic infarction, polencephaly, cystic encephalopmalacia, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, |

| Hydrocephalus | Developmental (aqueductal stenosis), post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus |

Targeted neurosonography for high-risk fetuses

ISUOG also published “Practice Guideline Part 2: for the performance of targeted neurosonography” to describe the diagnostic ultrasound study protocol in cases with increased risk of CNS malformations suspected with screening ultrasound or other indications12. The guideline recommends that targeted neurosonography systematically evaluates continual visualization of the fetal brain's four coronal and three sagittal planes. Coronal planes include transfrontal, transcaudate, transthalamic, and transcerebellar planes. Sagittal planes include midsagittal (or median) anterior and posterior planes and bilateral parasagittal planes. Through those planes, the neurosonography assesses the detailed morphology of ventricles, cavum septi pellucidi, corpus callosum, cerebral parenchyma, basal ganglia, and cerebellum.

Spinal assessment includes transverse (or axial) and sagittal planes of the fetal spine to assess spinal cord and vertebral morphology and any disruption of the spinal column and overline tissues with signs of neural tube defect and vertebral anomaly.

While a transabdominal scan is standard, transvaginal sonography offers higher image resolution than a transabdominal scan if the fetal head is near the probe (cephalic position). 3D ultrasound may also be beneficial in certain circumstances (if available), especially when a reconstruction of a 3D structure is useful for diagnosis.

In systematic review and meta-analysis, the ENSO (European Neurosonography) Working Group stated that dedicated neurosonography operated by trained practitioners could detect as many as associated anomalies that were detected in fetal brain MRI in isolated ventriculomegaly13 and isolated agenesis of corpus callosum14. It is also recognized that the specificity and sensitivity of neurosonography is operator dependent on most clinical assessment tools.

Advances in ultrasound probes, machine setting protocols, and post-acquisition software have provided increased resolution and tissue contrast resulting in finer anatomical assessment which enables to detection of subtle anomalies that were not detectable before.

Technical overview of fetal brain MRI

Safety of Fetal MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the fetus (as well as the pregnant person for other clinical purposes) has been performed for over four decades, with the preponderance of evidence documenting no known risks to the fetus after applying 1.5 Tesla or less at any gestational age. More recent data has also shown safety at 3 Tesla, especially when study durations are less than 30 minutes in length15.

While it is considered a safe procedure, theoretical concerns for the fetus remain including nerve stimulation (related to magnetic gradient changes), teratogenicity, heating (related to radiofrequency energy deposition)16, and acoustic effects related to the scanner's noise17.

Maternal concerns about the procedure include discomfort after prolonged periods remaining supine or lateral (more of a concern at later gestational ages), claustrophobia, and the adverse effects of ambient heating related to the MR suite environment.

MR access varies depending in LMIC or HIC healthcare systems in HIC or LMIC relative to availability, cost, and safety18. Abdominal ultrasound has been the preferred fetal screening test because of cost, availability, and safety. Fetal MRI is typically considered, if available, to further assess equivocal sonographic findings. Evidence that gadolinium crosses the maternal-placental barrier with entry into fetal circulation remains an additional safety concern. Gadolinium-based contrast agents are concerned in use during pregnancy, given potential teratogenic and/or toxic concerns to the developing fetus19,20. However, there are no clear data to either prove contrast harm or safety at this time.

Technical Considerations

Fetal MRI requires imaging protocols performed by technologists and radiologists who are experienced with the procedure. While some reviews have advocated for specific requirements regarding preparation (e.g., feeding or withholding food, withholding stimulants such as caffeinated beverages), others have found no effect of the diet21. Additionally, as it can be challenging to see the critical structures such as sizeable cerebral parenchyma or primary sulcal development, fetal MRI is usually not performed until after 17 weeks of gestation to maximize the evaluation of the brain structures. Serial fetal MRI studies into the third trimester can help elucidate areas of concern based on earlier MRI findings. Variability from the vendor to vendor exists regarding available standard sequences with different imaging parameters. However, across all systems, the mainstay of fetal MRI is a single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) T2 technique. Standard MRI sequences acquire information concerning the entire volume of tissue simultaneously, which typically takes several minutes; maternal or fetal movements during this acquisition degrade the images. The SSFSE technique acquires all information in a single image over a short duration before moving to the following image. Typical SSFSE sequences take 30-40 seconds to acquire, with a stack of 20-30 images. Each image requires just over a second to acquire. Movement can affect a single image or the entire stack but not consistently, making motion correction difficult. While some argue for interleaving the images to prevent crosstalk between images (one image acquisition affecting the image next to it), others argue that continuous imaging can help improve image review between images, with minimal effects of cross-talk using modernized scanners. Because of the intrinsic increased water content of the fetal brain compared to neonates and older children, increasing the time to echo (TE) duration to 170-220 msec can help improve gray-white brain matter contrast. Other parameters should be set per the specific vendor.

Typically, the SSFSE T2 is the mainstay of fetal neuroimaging and highlights CSF spaces and the brain parenchyma. Triplanar 3 mm image acquisitions are necessary to fully evaluate the fetal brain, 2 mm thick images can better delineate anatomical details. Because the fetus frequently moves, the technologist must adjust the image angle based on the most recently acquired images.

As with routine brain imaging done in the neonate, other sequences can be complementary to the T2 acquisitions. There are different ways in which routine sequences are adopted for fetal imaging done in the neonate, other sequences can be complementary to the T2 acquisitions depending on the vendor. This includes using faster imaging base sequences (though these frequently compromise image resolution) and acceleration factors. Current research is looking at ways in which fetal motion correction can be done in real-time to improve image quality further.

A T1 weighted image can be performed in a number of ways, including as a T1 2D gradient echo (GRE), inversion recovery (IR), or fast spin echo (FSE) technique versus a 3d acquisitions derived from abdominal imaging such as THRIVE (T1 weighted High-Resolution Isotropic Volume Examination) or utilizing a volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination (VIBE)22. Regardless of the imaging acquisition technique, T1 sequences are most helpful in looking for abnormalities with intrinsic T1 hyperintensity – which can help identify fat, calcium, and hemorrhage in utero. A T2* GRE-based sequence can also be complementary for looking for hemorrhage and calcium. State-free precession (SSFP, also known as BFFE, FIESTA, or CISS/trueFISP) imaging can be extremely helpful in evaluating small structures when there is high contrast between fluid and soft tissues, with movement-induced degradation.

Finally, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) can improve the detection of ischemic tissue changes (such as with the complication of twin-twin transfusion during monochorionic/monoamniotic multiple gestation pregnancies) as well as documentation of hemorrhage or calcification. Both DWI and DTI can be performed rapidly, along with other acquisitions. However, directionality information using tensor imaging is more prone to motion artifacts and technically more difficult to execute.

Additional newer techniques, including magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and arterial spin labeling (ASL), continue to be investigated.

While qualitative fetal MRI studies continue to improve technically, there will always remain limitations given the small sizes of fetal brain structures and the technical limitations in image resolution.

Fetal brain MRI in prenatal diagnosis and counseling

In prenatal diagnosis and counseling of fetal brain anomalies, neuroimaging such as sonography and MRI play critical roles in providing anatomical diagnosis and prognostic information to expectant parents about the neurodevelopmental prognosis of their children. Such information is essential to plan perinatal care, such as delivery mode, delivery timing, selection of appropriate hospital for the birth,, birth resuscitative strategies, neonatal diagnostic evaluations, and postnatal care.

Fetal brain MRI remains the current gold standard for providing the anatomical diagnosis of fetal brain anomalies. Since the 1980s, MRI has been used to assess fetal brain anatomy 23,24 because it is safe for the fetus and pregnant woman, providing high tissue contrast to identify internal regional structures. The clinical utility of fetal MRI has improved using fast scan protocols (see previous section) to overcome motion artifacts. Fetal brain MRI has been complementary to fetal sonography to refine the anatomical diagnosis of fetal brain anomaly.

Multiple studies have been conducted to test the accuracy of fetal brain MRI in diagnosing fetal brain anomalies. The MERIDIAN Study was the first multi-centered clinical trial to determine its diagnostic accuracy and compare that of ultrasound25. This study consisted of a sixteen multicenter prospective cohort of 565 fetuses with brain anomalies and the findings showed that the accuracy of fetal MRI was 93% compared to 68% of the ultrasound when neonatal MRI was the accurate diagnosis25. Fetal MRI provided additional diagnostic information in 387 (49%) cases, which changed prognostic information in at least 157 (20%) of the cases and led to changes in clinical management in more than one in three cases25.

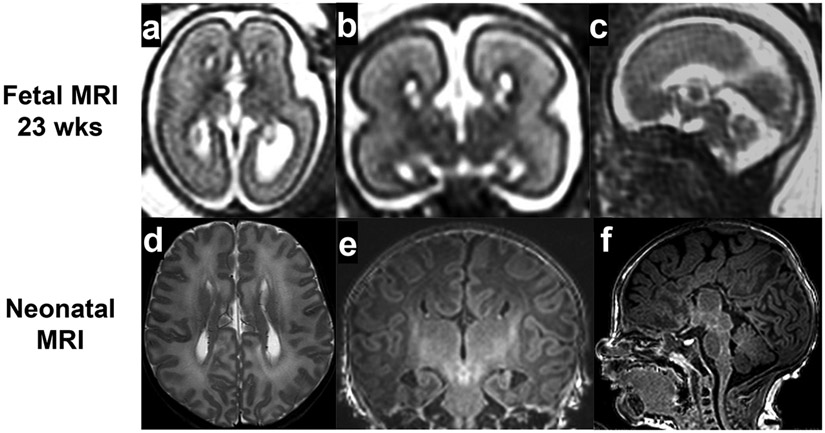

In a subgroup analysis of the MERIDIAN study, fetal MRI had higher diagnostic accuracy than fetal sonography in the diagnosis of fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly (MRI 98.7% and sonography 89.9%)26, failed commiseration (MRI 94.9% and sonography 34.2%)27, and posterior fossa abnormalities (MRI 87.7% and sonography 65.4%)28. The utility of fetal brain MRI can be reviewed using agenesis of the corpus callosum as an example. Agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC) is a congenital anomaly of the callosal development, classified as either complete or partial agenesis, dysplastic or hypoplastic, isolated (Fig. 2) or complex (syndromic, Fig. 3a-c). The 22 weeks fetus in Fig. 3 had ACC, Dandy-Walker malformation, and multiple other congenital anomalies, including double outlet right ventricle, skeletal anomalies, and chromosome 9 trisomy mosaicism. ACC is a relatively common fetal brain anomaly with an incidence of 0.2-0.35% of all pregnancies29,30. ACC has vast etiological heterogeneity and is frequently associated with multiple congenital anomalies (in 25% of cases), chromosomal anomalies (16%), and genetic syndrome (13%)30. Therefore, fetal brain MRI plays a critical role because detecting associated brain anomalies directly affects the diagnosis and prognosis of affected fetuses. Many studies support the benefit of fetal brain MRI in addition to sonography. Most studies are retrospective 31-41. Two studies are prospective27,42. All studies found that fetal brain MRI detected additional brain anomalies that were not detected by the ultrasound.

Fig 2.

Isolated agenesis of corpus callosum

Fig 3.

Complex agenesis of corpus callosum (with Dandy Walker malformation)

Two systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses of the above studies assessed the utility of fetal brain MRI in prenatal diagnosis of ACC14,43. A meta-analysis reviewed 14 studies, including 798 fetuses with a prenatal diagnosis of isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum, found that fetal brain MRI detected additional brain lesions in comparison to the original fetal neurosonography.43 In the case of complete agenesis of the corpus callosum, fetal MRI detected additional brain pathologies in 18.5% of standard sonography diagnoses and 5.7% of neurosonography diagnoses. Similarly, in fetuses with partial agenesis of the corpus callosum, fetal MRI detected additional brain pathologies in 16.2% of standard sonography diagnoses and 13.4% of neurosonography diagnoses. A retrospective 14 multicentered cohort study including 269 fetuses with prenatally diagnosed isolated agenesis of corpus callosum found that fetal MRI detected additional brain pathologies to neurosonography study findings in 11.6% of complete agenesis of the corpus callosum and 9.7% of partial agenesis of the corpus callosum14.

While ventriculomegaly and callosal anomalies are common and well-studied, fetal brain anomalies indicative of neurosonography and fetal brain MRI are robust.

Fetal brain MRI and prenatal prediction of neurodevelopmental prognosis

Fetal brain MRI also provides valuable information to predict the neurodevelopmental prognosis of affected fetuses. In the follow-up study of children who participated in the MERIDIAN Study, diagnostic accuracy of fetal MRI remained higher (529 of 574, 92%) than that of fetal sonography (387 of 574, 67%)44. Of 156 participants with developmental outcomes, the prediction of "normal prognosis" was accurate in 67% with fetal MRI, higher than that of ultrasound (51%). The study reconfirmed the diagnostic accuracy of the fetal brain MRI but less prognostic accuracy for identifying children with normal outcomes44.

Correlations between fetal brain MRI findings and neurodevelopmental prognosis have been reported in many studies. Here we present cases of ACC because of its difficulty in predicting prognosis. Prenatally diagnosed ACC has variable neurodevelopmental outcomes ranging from typical development to severe developmental delay involving multiple domains of development, language, cognitive, motor, and seizures6-9,45. Regardless of the subtypes of complete or partially isolated ACC, 15-30% of patients have significant neurodevelopmental impairment after birth6-9,45.

A meta-analysis of 27 articles reported neurodevelopmental outcomes of 484 fetuses with fetal MRI diagnosis of isolated ACC. The study reported risks of borderline/moderate neurodevelopmental impairments in 16% of children with complete ACC and 15% with partial ACC. Severe neurodevelopmental impairments were seen in 8 and 13% of children. The study reported normal outcomes in 76 and 71% of children with complete or partial ACC, which were relatively favorable numbers8. The follow-up periods varied from 3 months to 16 years in the studies.

In contrast, a recent study reporting long-term (school-age) neurodevelopmental outcomes of prenatally diagnosed isolated ACC has revealed a higher incidence of learning disorders. 29% had borderline intellectual impairment (intellectual quotient < 1SD lower than mean), and 21% had intellectual disability (IQ<2SD lower than mean), which left only 50% of children to be with typical developmental outcomes46. Those studies revealed that although fetal brain MRI is accurate in diagnosing ACC anatomically, prognosis prediction remains challenging with current imaging technology and limited long-term outcomes knowledge. In cases of ACC, fetal MRI and even postnatal MRI diagnosis of isolated/complex, complete/partial ACC would not lead to a specific prognosis.

As seen in above case , the neurodevelopmental phenotype may only appear later childhood, which makes prenatal prognosis prediction challenging. On the other hand, early involvement of specialists such as pediatric neurologists and early intervention, provide the opportunity to continuously monitor a child’s neurodevelopmental status and comorbidities, which may not appear in earlier childhood.

In the current prenatal diagnosis of fetal brain anomalies, fetal brain MRI plays the most prominent role in diagnosis and prognosis counseling. Further development of neurodevelopmental prognosis markers and increasing knowledge of long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of affected children are needed. Relatively rare and etiologically heterogeneous fetal brain anomalies would require large-scale registry-based study to reveal comprehensive clinical pictures of the affected fetuses and children. Though there are no clear practice guidelines, most US practitioners utilize fetal brain MRI. The Fetal Neurology Consortium, a group of fetal neurologists from eight US children’s hospitals, conducted a web-based, self-administered survey of 41 US institutions practicing fetal neurology consultation. All institutions used fetal brain MRI for their practice not only to diagnose the fetal condition but to present the image to pregnant women to counsel the fetal condition47. Therefore, there is a foundation of collaborative multi-centered fetal neurology registry to conduct large-size long-term cohort studies to facilitate the above research.

Current challenges and opportunities using fetal brain MRI

The challenges and opportunities of fetal brain MRI to provide anatomical diagnosis and prognosis have three aspects. Firstly, the technical challenges are based on motion artifacts, and a small-sized fetal brain has limited tissue contrast due to pre- or ongoing myelination. Secondly, there are inherent challenges because of the timing of fetal MRI acquisition and ongoing dynamic brain development. Especially, cortical development is ongoing with dynamic changes in morphology. Disorders of cortical development might not reveal all features in the second or early third trimesters because robust cortical development is ongoing. As shown in cases of ACC, an anatomical diagnosis does not specify an individual’s future neurodevelopmental prognosis. To overcome such limitations, investigators have been to improve the fetal brain MRI technology and extract diagnostic and prognostic information using quantitative analysis of fetal brain MR imaging. Lastly, access to maternal levels of care involves social determinants, such as race, poverty, and geographic access. New technologies, such as portable, low-cost, low magnetic field strength MRI may become practical alternatives to the current MRI setting, as studied in adult hemorrhagic48 and ischemic stroke49.

Future Diagnostic Strategies

First-trimester ultrasound, the earliest detection of fetal CNS anomaly

The evolution of first-trimester ultrasound has been changing the diagnostic strategy of fetal anomalies, including CNS anomalies. While clinical guidelines are yet to be established, ISUOG screening guidelines recommend visualizing the transventricular and transcerebellar planes11,12. It could detect acrania, alobar holoprosencephaly, and cephalocele50. One study also showed that detecting the cystic posterior fossa in the first trimester would increase fetal risks of chromosomal and structural defects detected in later ultrasounds51. Development of earlier biomarkers may affect the following screening and diagnostic strategy, while targeted neurosonography in second trimester is recommended to have a more specific diagnosis12.

Quantitative analysis of fetal brain MRI

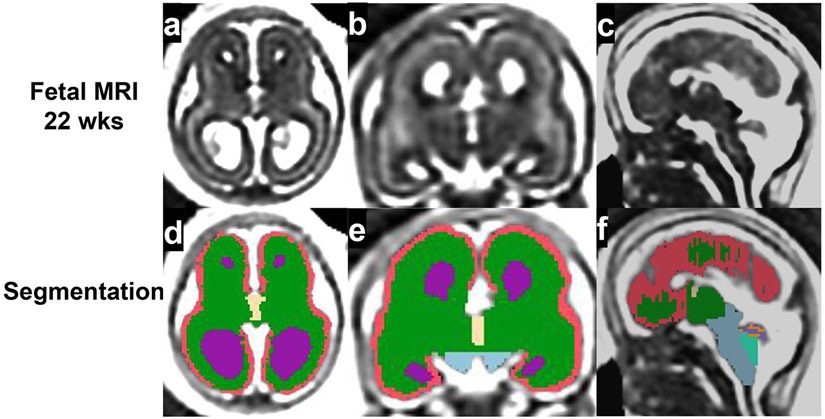

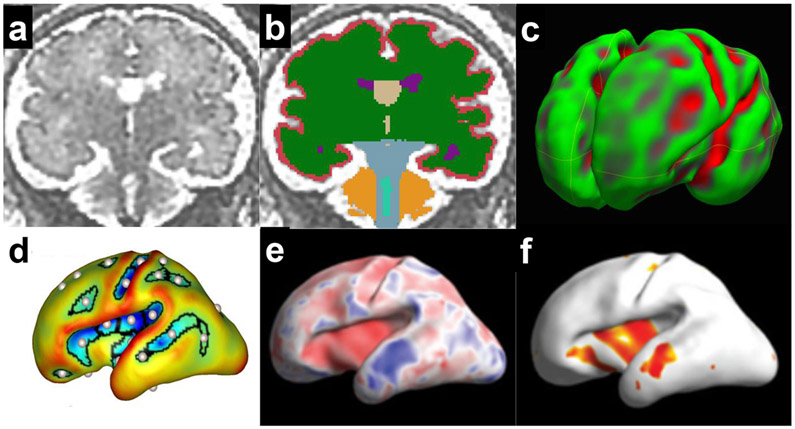

Fetal brain MRI’s high tissue resolution enables further post-acquisition analysis of the digital images. Computational imaging processing allows for correcting motion artifacts for further post-acquisition imaging analysis. High tissue contrast enables precise bordering of the structures and segmentation of regional brain structures. Using such a segmentation method, three-dimensional (3D) cerebral surface models can be reconstructed for surface analysis. Here, we briefly introduce relatively well-used analytic methods of fetal brain MRI. Quantitative analysis of fetal brain MRI has successfully revealed unique precise intrauterine brain development of various conditions such as isolated ventriculomegaly52-56, isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum 57,58, posterior fossa malformation59, congenital heart disease60,61, or Down syndrome62-64. Those studies showed the feasibility of quantifying regional structural growth, white matter maturation, and cerebral surface development of the fetuses.

Volumetric analysis of regional brain structure

is the most widely used method to quantify regional structural volume in three-dimensional (3D) reconstructed MRI images. The process generally involves manual or automated segmentation of recognizable structures in the image and 3D volumetric calculation by reconstructing segmented structures56,59,62 (Fig 3a-f, 4a-b).

Fig 4.

Quantitative analysis of fetal brain MRI

Cerebral surface development

uses reconstructed cerebral surface (usually grey-white matter border surface) of the fetal brain MR images (Fig 4c, d). The reconstructed 3D surface is studied using surface area calculation, curvature analysis (Fig 4c) of whole or regional surface53,65, sulcal developmental pattern analysis56,58 (Fig 4d), or regional sulcal depth analysis64 (Fig 4e, f). The latest regional sulcal depth analysis enables precise regional sulcal developmental assessment, which could associate with future regional functionality64. The regional sulcal developmental analysis of fetuses with Down syndrome discovered a region-specific reduction in bilateral Sylvian, the right central, and parieto-central sulcal depth and increased depth in the left supratemporal sulcus64. These affected regions associate with specifically impaired regional functionality in Down syndrome, such as multi-modal sensory processing (insula in Sylvian fissure)66, visual-motor processing (parieto-occipital)67, primary somatic motor/sensory areas (central), auditory working memory, and auditory processing (supratemporal sulcus).

Alterations in fetal sulcal development may persist into later childhood. In sulcal developmental pattern analysis of school-age children with isolated ACC, sulcal positional alterations similar to the fetal brain were identified. The degrees of alterations may associate with their neurodevelopmental impairments68.

Functional fetal brain MRI

Application of functional brain MRI methods utilized in infants and children to the intrauterine fetal brain. It uses BOLD signals to reflect regional oxygen consumption, thus the regional metabolic activity of the fetal brain. In contrast to task-based functional MRI used in postnatal subjects, investigators use a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging the fetal subjects to analyze spontaneous fluctuations in the BOLD signal. A recent resting-state functional MRI study detected correlations between fetal motor behavior and activation of supplementary motor area 69. A resting-state functional MRI study of fetuses from 19 to 40 weeks GA identified temporal development of the functional thalamocortical connectome and the associated cortical-cortical connectivity in the living fetuses70. Thalamocortical connectivity had peak increase of connection strength between 29- and 31-weeks GA consistent with the timing of densely innervation and penetration of thalamocortical afferent fibers into the cortical plate revealed in the fetal histopathological studies71,72. Cortico-cortico connectivity also had peak increase of connection strength around 29 weeks GA, which was also consistent with histopathological assessment71,72. The study also showed initially symmetrical then later lateralized (asymmetrical) connectivity development, that could suggest increasingly diverse connectivity landscape of the two hemispheres70. Functional fetal MRI assess novel aspects of connectivity in fetal brain which may provide high-resolution anatomical and functional correlations to understand fetal behavior.

The utilization of machine learning facilitates fetal brain MR image analytic processes. Machine learning technique has been implemented for the automated fetal brain quality assessment73, gestational age determination74, or fetal diffusion-weighted MR image reconstruction75.

Innovative computational imaging analytic techniques enable quantitative assessment of fetal brain development to facilitate understanding of normal and pathological fetal brain development. Precise quantitative assessment of the fetal brain may provide potential neuroimaging biomarkers to assess the well-being of fetal brain development, disease markers, and prognostic markers.

Regional and global aspects of fetal neuroimaging in prenatal diagnosis and counseling of fetal brain anomaly

Clinical decision-making to utilize fetal neurosonography and fetal brain MRI in countries such as the United States is being revised based on state and region-specific capabilities to train specialized practitioners and support imaging facilities with access to all pregnant women regardless of healthcare disparities. Earlier decisions based on fetal brain MRI can assist women and their partners in reaching more time-sensitive decisions to continue or terminate the pregnancy and plan post-pregnancy strategies for pediatric healthcare.

The environment where pregnant women and fetuses receive prenatal care varies regionally and globally. Social determinants of pregnant women’s health also impact any environment. Advances in fetal neuroimaging are robust. However, the implementation of such technology may be influenced by regional and global factors. The First Look Study - a Cluster randomized trial at five low- and middle-income countries - compared the prevalence of antenatal care and hospital delivery rates of complicated pregnancies between standard antenatal care (28 control clusters, n=24,263 births) and standard care plus two ultrasounds and referral for complications (28 intervention clusters, n=23,160 births) groups76. Despite the availability of ultrasound at antenatal care in the intervention group, it did not increase prevalence of antenatal care, hospital delivery, or referral for additional care. The investigator analyzed potential reasons77. They analyzed structured interview data administered during the trial to the women who received an ultrasound that identified a possible pregnancy complication. The responses from 700 women revealed preciseness of referral instructions increased the likelihood to attend their referral. Identified barriers to attending referrals were cost, transportation, and distance to the referral sites, not connecting with an appropriate provider, not knowing where to go, and being told to return later77. The study concluded better communication between the sonographer and the patient increases the likelihood of a completed referral, including describing ultrasound findings, reason for the referral, referral card, describing where to go in the hospital, and explaining the procedures at the hospital. Three levels of communication – between the sonographer and the patient, the sonographer and the clinic staff, and the sonographer and the hospital77. As shown in this study, the strategy to utilize fetal neuroimaging and to train multiple discipline specialists (maternal fetal medicine specialists, geneticists, radiologists, neonatologists, pediatric neurologists), local referral and hospital systems, should be tailored and designed based on regional and global factors. The dissemination of fetal neuroimaging technology would involve implementing training, equipment, and systemic clinical resource organization suitable to the specific regional environments.

Conclusion

Increasing evidence supports the high accuracy of fetal brain MRI in the prenatal anatomical diagnosis of fetal brain anomalies. Advances in MRI technologies, including a single-shot fast spin echo T2 technology, allow high-quality fetal brain MRI to overcome motion artifact. While diagnostic accuracy is high, fetal brain MRI still faces challenges in predicting the future neurodevelopmental prognosis of affected fetuses. A large-scale, multi-center registry study will comprehensively characterize long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of prenatally diagnosed fetal brain anomalies, which are rare and heterogeneous in etiology. As a future landscape, quantitative analyses of fetal brain MRI detects subtle and potentially clinically relevant developmental aberrations in the living fetal brain, which may become potential neurodevelopmental biomarkers impacting prenatal counseling of fetal brain anomalies. To maximize its benefit, implementation of fetal neuroimaging should consider unique regional and global aspects of maternal and fetal care.

Table 3.

General characteristics of ultrasound and MRI in assessing fetal brain An overview of compared characteristics between fetal neuroimaging modalities. The comparison reflects current common practice status and may not include evolving features not yet distributed, such as significantly high-resolution ultrasound or functional MRI.

| Ultrasound | MRI | |

|---|---|---|

| Modality | Ultrasound | Magnetic resonance |

| Tissue resolution | Gross anatomy level | Gross anatomy ~ tissue level Higher tissue resolution |

| What to assess | Structures Tissue textures: bleeding, Superior to detect calcification. Function: Fetal movement, blood flow (doppler) |

Primarily structures Tissue textures: bleeding, Superior to detect ischemia, inflammation |

| Quantitative assessment | Fetal biometric growth assessment | Less quantitative in clinical practice |

| Cost* | Cost: comparable to MRI | Cost: Comparable to US |

| Access | More available than MRI | Less available than US |

| Equipment | Portable | Not portable More expensive than US |

| Longitudinal study | Repeat exam is easier than MRI | Possible, but more laborious than US |

Cost: Operational cost based on Medicare cost in the United States.

Summary.

Fetal sonography and brain MRI provide safe and accurate anatomical diagnosis of fetuses with brain anomalies.

Recent studies of fetal brain MRI provide evidence of improved diagnostic and prognostic accuracy, beginning with prenatal diagnosis.

Despite advances in fetal neuroimaging and accuracy of diagnosis, providing accurate neurodevelopmental prognosis remains challenging.

Quantitative analyses of fetal brain MRIs offer measurable imaging biomarkers that may more accurately associate with clinical outcomes.

Dissemination of fetal neuroimaging technology would involve implementing training, equipment, and systemic clinical resource organization suitable to the specific regional environments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Olusanya BO, Wright SM, Nair MKC, et al. Global Burden of Childhood Epilepsy, Intellectual Disability, and Sensory Impairments. Pediatrics. Jul 2020;146(1)doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, et al. Updated International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Diagnostic Criteria and Surveillance and Management Recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. Oct 2021;123:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malinger G, Prabhu A, Maroto Gonzalez A, et al. Fetal neurosonography as an accurate tool for diagnosis of brain involvement in tuberous sclerosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Apr 6 2023;doi: 10.1002/uog.26213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goergen SK, Fahey MC. Prenatal MR Imaging Phenotype of Fetuses with Tuberous Sclerosis: An Institutional Case Series and Literature Review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. Apr 2022;43(4):633–638. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A7455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelot AB, Represa A. Progression of Fetal Brain Lesions in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:899. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadie A, Radi S, Trestard L, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in prenatally diagnosed isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum. Acta Paediatr. Apr 2008;97(4):420–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00688.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangione R, Fries N, Godard P, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome following prenatal diagnosis of an isolated anomaly of the corpus callosum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Mar 2011;37(3):290–5. doi: 10.1002/uog.8882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Antonio F, Pagani G, Familiari A, et al. Outcomes Associated With Isolated Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. Sep 2016;138(3)doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folliot-Le Doussal L, Chadie A, Brasseur-Daudruy M, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome in prenatally diagnosed isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum. Early Hum Dev. Jan 2018;116:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh KY, Gibson TJ, Pinter JD, et al. Clinical outcomes following prenatal diagnosis of asymmetric ventriculomegaly, interhemispheric cyst, and callosal dysgenesis (AVID). Prenat Diagn. Jan 2019;39(1):26–32. doi: 10.1002/pd.5393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malinger G, Paladini D, Haratz KK, Monteagudo A, Pilu GL, Timor-Tritsch IE. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): sonographic examination of the fetal central nervous system. Part 1: performance of screening examination and indications for targeted neurosonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2020;56(3):476–484. doi: 10.1002/uog.22145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paladini D, Malinger G, Birnbaum R, et al. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): sonographic examination of the fetal central nervous system. Part 2: performance of targeted neurosonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2021;57(4):661–671. doi: 10.1002/uog.23616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Group EW. Role of prenatal magnetic resonance imaging in fetuses with isolated mild or moderate ventriculomegaly in the era of neurosonography: international multicenter study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2020;56(3):340–347. doi: 10.1002/uog.21974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Group EW. Role of prenatal magnetic resonance imaging in fetuses with isolated anomalies of corpus callosum: multinational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Jul 2021;58(1):26–33. doi: 10.1002/uog.23612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safety ACoM. ACR Manual on MR Safety.: American College of Radiology; 2020.

- 16.Cannie MM, De Keyzer F, Van Laere S, et al. Potential Heating Effect in the Gravid Uterus by Using 3-T MR Imaging Protocols: Experimental Study in Miniature Pigs. Radiology. Jun 2016;279(3):754–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaimes C, Delgado J, Cunnane MB, et al. Does 3-T fetal MRI induce adverse acoustic effects in the neonate? A preliminary study comparing postnatal auditory test performance of fetuses scanned at 1.5 and 3 T. Pediatr Radiol. Jan 2019;49(1):37–45. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4261-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulas D, Egloff A. Benefits and risks of MRI in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. Oct 2013;37(5):301–4. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh KY, Roberts VH, Schabel MC, Grove KL, Woods M, Frias AE. Gadolinium Chelate Contrast Material in Pregnancy: Fetal Biodistribution in the Nonhuman Primate. Radiology. Jul 2015;276(1):110–8. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15141488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Bharatha A, Montanera WJ, Park AL. Association Between MRI Exposure During Pregnancy and Fetal and Childhood Outcomes. JAMA. Sep 6 2016;316(9):952–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yen CJ, Mehollin-Ray AR, Bernardo F, Zhang W, Cassady CI. Correlation between maternal meal and fetal motion during fetal MRI. Pediatr Radiol. Jan 2019;49(1):46–50. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-4254-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Y, Li X, Jia F, et al. Optimization of the image contrast for the developing fetal brain using 3D radial VIBE sequence in 3 T magnetic resonance imaging. BMC Med Imaging. Jan 20 2022;22(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12880-022-00737-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith FW, MacLennan F, Abramovich DR, MacGilivray I, Hutchison JM. NMR imaging in human pregnancy: a preliminary study. Magn Reson Imaging. 1984;2(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(84)90126-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thickman D, Mintz M, Mennuti M, Kressel HY. MR imaging of cerebral abnormalities in utero. J Comput Assist Tomogr. Dec 1984;8(6):1058–61. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198412000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths PD, Bradburn M, Campbell MJ, et al. Use of MRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities in utero (MERIDIAN): a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet. Feb 4 2017;389(10068):538–546. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31723-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffiths PD, Brackley K, Bradburn M, et al. Anatomical subgroup analysis of the MERIDIAN cohort: ventriculomegaly. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Dec 2017;50(6):736–744. doi: 10.1002/uog.17475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths PD, Brackley K, Bradburn M, et al. Anatomical subgroup analysis of the MERIDIAN cohort: failed commissuration. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Dec 2017;50(6):753–760. doi: 10.1002/uog.17502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffiths PD, Brackley K, Bradburn M, et al. Anatomical subgroup analysis of the MERIDIAN cohort: posterior fossa abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Dec 2017;50(6):745–752. doi: 10.1002/uog.17485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glass HC, Shaw GM, Ma C, Sherr EH. Agenesis of the corpus callosum in California 1983-2003: a population-based study. Am J Med Genet A. Oct 1 2008;146A(19):2495–500. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JK, Wellesley DG, Barisic I, et al. Epidemiology of congenital cerebral anomalies in Europe: a multicentre, population-based EUROCAT study. Arch Dis Child. Dec 2019; 104(12):1181–1187. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ismail KM, Ashworth JR, Martin WL, et al. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging in prenatal diagnosis of central nervous system abnormalities: 3-year experience. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. Sep 2002;12(3):185–90. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.3.185.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glenn OA, Goldstein RB, Li KC, et al. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of fetuses referred for sonographically suspected abnormalities of the corpus callosum. J Ultrasound Med. Jun 2005;24(6):791–804. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.6.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Volpe P, Paladini D, Resta M, et al. Characteristics, associations and outcome of partial agenesis of the corpus callosum in the fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. May 2006;27(5):509–16. doi: 10.1002/uog.2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fratelli N, Papageorghiou AT, Prefumo F, Bakalis S, Homfray T, Thilaganathan B. Outcome of prenatally diagnosed agenesis of the corpus callosum. Prenat Diagn. Jun 2007;27(6):512–7. doi: 10.1002/pd.1719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghi T, Carletti A, Contro E, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of partial agenesis and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Jan 2010;35(1):35–41. doi: 10.1002/uog.7489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozyuncu O, Yazicioglu A, Turgal M. Antenatal diagnosis and outcome of agenesis of corpus callosum: A retrospective review of 33 cases. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2014;15(1):18–21. doi: 10.5152/jtgga.2014.84666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruland AM, Berg C, Gembruch U, Geipel A. Prenatal Diagnosis of Anomalies of the Corpus Callosum over a 13-Year Period. Ultraschall Med. Dec 2016;37(6):598–603. Pranatale Diagnostik von Corpus-Callosum-Anomalien in einem 13 Jahreszeitraum. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Wit MC, Boekhorst F, Mancini GM, et al. Advanced genomic testing may aid in counseling of isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum on prenatal ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. Dec 2017;37(12):1191–1197. doi: 10.1002/pd.5158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masmejan S, Blaser S, Keunen J, et al. Natural History of Ventriculomegaly in Fetal Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum. J Ultrasound Med. Mar 2020;39(3):483–488. doi: 10.1002/jum.15124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santirocco M, Rodo C, Illescas T, et al. Accuracy of prenatal ultrasound in the diagnosis of corpus callosum anomalies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. Feb 2021;34(3):439–444. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1609931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turkyilmaz G, Sarac Sivrikoz T, Erturk E, et al. Utilization of neurosonography for evaluation of the corpus callosum malformations in the era of fetal magnetic resonance imaging. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. Aug 2019;45(8):1472–1478. doi: 10.1111/jog.13995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasprian G, Brugger PC, Schopf V, et al. Assessing prenatal white matter connectivity in commissural agenesis. Brain. Jan 2013;136(Pt 1):168–79. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sileo FG, Di Mascio D, Rizzo G, et al. Role of prenatal magnetic resonance imaging in fetuses with isolated agenesis of corpus callosum in the era of fetal neurosonography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. Jan 2021;100(1):7–16. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hart AR, Embleton ND, Bradburn M, et al. Accuracy of in-utero MRI to detect fetal brain abnormalities and prognosticate developmental outcome: postnatal follow-up of the MERIDIAN cohort. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. Feb 2020;4(2):131–140. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30349-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shwe WH, Schlatterer SD, Williams J, du Plessis AJ, Mulkey SB. Outcome of Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum Diagnosed by Fetal MRI. Pediatr Neurol. Oct 2022;135:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romaniello R, Arrigoni F, De Salvo P, et al. Long-term follow-up in a cohort of children with isolated corpus callosum agenesis at fetal MRI. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. Dec 2021;8(12):2280–2288. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarui T, Venkatesan C, Gano D, et al. Fetal Neurology Practice Survey: Current Practice and the Future Directions. Pediatr Neurol. Apr 25 2023;145:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2023.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mazurek MH, Cahn BA, Yuen MM, et al. Portable, bedside, low-field magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of intracerebral hemorrhage. Nat Commun. Aug 25 2021;12(1):5119. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25441-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yuen MM, Prabhat AM, Mazurek MH, et al. Portable, low-field magnetic resonance imaging enables highly accessible and dynamic bedside evaluation of ischemic stroke. Sci Adv. Apr 22 2022;8(16):eabm3952. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm3952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volpe N, Dall'Asta A, Di Pasquo E, Frusca T, Ghi T. First-trimester fetal neurosonography: technique and diagnostic potential. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2021;57(2):204–214. doi: 10.1002/uog.23149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcia-Rodriguez R, Garcia-Delgado R, Romero-Requejo A, et al. First-trimester cystic posterior fossa: reference ranges, associated findings, and pregnancy outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. Mar 2021;34(6):933–942. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1622673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grossman R, Hoffman C, Mardor Y, Biegon A. Quantitative MRI measurements of human fetal brain development in utero. Neuroimage. Nov 1 2006;33(2):463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scott JA, Habas PA, Rajagopalan V, et al. Volumetric and surface-based 3D MRI analyses of fetal isolated mild ventriculomegaly: brain morphometry in ventriculomegaly. Brain Struct Funct. May 2013;218(3):645–55. doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0418-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keunen K, Isgum I, van Kooij BJ, et al. Brain Volumes at Term-Equivalent Age in Preterm Infants: Imaging Biomarkers for Neurodevelopmental Outcome through Early School Age. J Pediatr. May 2016;172:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kyriakopoulou V, Vatansever D, Elkommos S, et al. Cortical overgrowth in fetuses with isolated ventriculomegaly. Cereb Cortex. Aug 2014;24(8):2141–50. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tarui T, Madan N, Graham G, et al. Comprehensive quantitative analyses of fetal magnetic resonance imaging in isolated cerebral ventriculomegaly. Neuroimage Clin. Feb 24 2023;37:103357. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jakab A, Kasprian G, Schwartz E, et al. Disrupted developmental organization of the structural connectome in fetuses with corpus callosum agenesis. Neuroimage. May 1 2015;111:277–88. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarui T, Madan N, Farhat N, et al. Disorganized Patterns of Sulcal Position in Fetal Brains with Agenesis of Corpus Callosum. Cereb Cortex. Sep 1 2018;28(9):3192–3203. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akiyama S, Madan N, Graham G, et al. Regional brain development in fetuses with Dandy- Walker malformation: A volumetric fetal brain magnetic resonance imaging study. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263535. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0263535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ortinau CM, Mangin-Heimos K, Moen J, et al. Prenatal to postnatal trajectory of brain growth in complex congenital heart disease. Neuroimage Clin. Sep 27 2018;20:913–922. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peyvandi S, Latal B, Miller SP, McQuillen PS. The neonatal brain in critical congenital heart disease: Insights and future directions. Neuroimage. Jan 15 2019;185:776–782. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tarui T, Im K, Madan N, et al. Quantitative MRI Analyses of Regional Brain Growth in Living Fetuses with Down Syndrome. Cereb Cortex. Jan 10 2020;30(1):382–390. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhz094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patkee PA, Baburamani AA, Kyriakopoulou V, et al. Early alterations in cortical and cerebellar regional brain growth in Down Syndrome: An in vivo fetal and neonatal MRI assessment. Neuroimage Clin. Dec 23 2020;25:102139. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yun HJ, Perez JDR, Sosa P, et al. Regional Alterations in Cortical Sulcal Depth in Living Fetuses with Down Syndrome. Cereb Cortex. Jan 5 2021;31(2):757–767. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhaa255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Benkarim OM, Hahner N, Piella G, et al. Cortical folding alterations in fetuses with isolated non-severe ventriculomegaly. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;18:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gogolla N. The insular cortex. Curr Biol. Jun 19 2017;27(12):R580–R586. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pitzalis S, Fattori P, Galletti C. The human cortical areas V6 and V6A. Vis Neurosci. Jan 2015;32:E007. doi: 10.1017/S0952523815000048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vasung L, Yun HJ, Feldman HA, Grant PE, Im K. An Atypical Sulcal Pattern in Children with Disorders of the Corpus Callosum and Its Relation to Behavioral Outcomes. Cereb Cortex. Jul 30 2020;30(9):4790–4799. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ji L, Majbri A, Hendrix CL, Thomason ME. Fetal behavior during MRI changes with age and relates to network dynamics. Hum Brain Mapp. Mar 2023;44(4):1683–1694. doi: 10.1002/hbm.26167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taymourtash A, Schwartz E, Nenning KH, et al. Fetal development of functional thalamocortical and cortico-cortical connectivity. Cereb Cortex. Apr 25 2023;33(9):5613–5624. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhac446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kostovic I, Judas M. Prolonged coexistence of transient and permanent circuitry elements in the developing cerebral cortex of fetuses and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. May 2006;48(5):388–93. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kostovic I, Judas M. The development of the subplate and thalamocortical connections in the human foetal brain. Acta Paediatr. Aug 2010;99(8):1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Largent A, Kapse K, Barnett SD, et al. Image Quality Assessment of Fetal Brain MRI Using Multi-Instance Deep Learning Methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. Sep 2021;54(3):818–829. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kojita Y, Matsuo H, Kanda T, et al. Deep learning model for predicting gestational age after the first trimester using fetal MRI. Eur Radiol. Jun 2021;31(6):3775–3782. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-07915-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karimi D, Jaimes C, Machado-Rivas F, et al. Deep learning-based parameter estimation in fetal diffusion-weighted MRI. Neuroimage. Nov 2021;243:118482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goldenberg RL, Nathan RO, Swanson D, et al. Routine antenatal ultrasound in low- and middle-income countries: first look - a cluster randomised trial. BJOG. Nov 2018;125(12):1591–1599. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Franklin HL, Mirza W, Swanson DL, et al. Factors influencing referrals for ultrasound-diagnosed complications during prenatal care in five low and middle income countries. Reprod Health. Dec 12 2018;15(1):204. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0647-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]