Abstract

BACKGROUND

The fourth industrial revolution has brought about developments in information and communication technologies for interventions in older adults with dementia. Currently, most interventions focus on single interventions. However, community-dwelling older adults with dementia require comprehensive cognitive interventions, and clinical studies analyzing the effects of comprehensive interventions based on randomized controlled trials are lacking.

AIM

The aim of the study was to examine the effects of an information and communication technology-based comprehensive cognitive training program, Smart Brain, on multi-domain function among community-dwelling older adults with dementia.

DESIGN

This was a two-group, randomized, controlled trial.

SETTING

This study was conducted at participant’s home.

POPULATION

We analyzed older adults with dementia.

METHODS

Participants were randomly allocated to either the intervention group (N.=30) or the control group (N.=30). Older adults with dementia in the intervention group received 8 weeks of Smart Brain comprehensive cognitive training using a tablet, whereas the control group received a similar tablet but without the training. We measured the outcomes at baseline, and at 4 and 8 weeks. Cognitive function, depression, quality of life, balance confidence, physical ability, nutrition, and caregiver burden were compared between groups.

RESULTS

In the intervention group, cognitive function statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (2.03; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.81) and week 8 (2.70; 95% CI 1.76 to 3.64). Depression was statistically different from week 0 to week 8 (-1.67, 95% CI -2.85 to -0.48). Physical ability statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (-0.85; 95% CI 1.49 to -0.20) and week 8 (-1.44; 95% CI -2.29 to -0.59). Nutrition statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (0.67; 95% CI 0.05 to 1.28) and week 8 (1.10; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.84).

CONCLUSIONS

Smart Brain significantly improved cognitive function, reduced depression, and enhanced physical and nutritional status in older adults with dementia. This demonstrates its potential as an effective non-pharmacological intervention in community-based dementia care.

CLINICAL REHABILITATION IMPACT

Smart Brain’s personalized approach, which integrates user-specific preferences and expert guidance, enhances engagement and goal achievement in dementia care. This enhances self-esteem and clinical outcomes, demonstrates the application’s potential to innovate rehabilitation practices.

Key words: Cognitive dysfunction, Community health nursing, Dementia, Mobile applications, Information technology

Dementia is a syndrome wherein cognitive function deteriorates with age. Dementia has physical, psychological, social, and economic effects not only on the person experiencing dementia, but also on caregivers, families, and society at large.1 Since the increase in the number of patients with dementia places a burden not only on patients but also on their families and social systems, intervention is necessary.2 Dementia treatment can be divided into pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.3 Pharmacological treatments include atypical antipsychotic drugs such as donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine,4 and non-pharmacological treatments include cognitive training, physical exercise, and diet.5 However, non-pharmacological treatment methods should be implemented first because they are cheaper than pharmacological treatment methods and have no side effects.6, 7 The fourth industrial revolution has led to the development of information and communication technology and the platforms using such technology. Advanced technologies such as the Internet, personal digital assistants, computer kiosks, and mobile phones8, 9 have largely replaced pen-and-paper-based learning.10 Additionally, a recent surge in the development of information and communication technology is because of the rapid increase in the number of patients with dementia, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and existing health and social welfare systems that cannot meet people’s needs.11 Digitalized content focused on older adults can increase the participation of older adults with visual and auditory cognitive disabilities12 and has the advantage of enabling learning for older adults who live far away or have difficulties in the face-to-face intervention.13 According to previous studies, various online-based cognitive programs designed for older adults with dementia are being developed and verified. Cognitive function was improved through a cognitive game using information and communication technology in patients with dementia,14-16 and depression in older adults with dementia was reduced through an online program.17 In addition, quality of life was improved through online assistive technology,18 physical function was improved through an online walking program,19, 20 and nutritional status was improved through a web-based program.21 Moreover, in several systematic literature review,22, 23 information and communication technology-based cognitive training group was more helpful in improving cognitive function than the active control group that did not use computer or devices but underwent cognitive training. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct an online-based training for older adults with MCI or dementia. Until now, many online intervention studies for patients with dementia have focused on single interventions, such as cognitive, emotional, and physical interventions. However, according to the results of a systematic review, online cognitive programs were found to be more effective when integrated.22 Therefore, we developed Smart Brain, an online comprehensive cognitive program, the effectiveness of which requires verification. This study aimed to verify the effects of the comprehensive online program, Smart Brain, developed by us based on the cognition, emotion, and physical status of older adults with dementia.

Materials and methods

Ethics committee approval statement

This randomized, single-blind, controlled study was conducted between July 2022 and October 2022 in Incheon Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea. This study was approved by the Gachon University Institutional Review Board (1044396-202203-HR-070-01) and was registered on the cris.org website (KCT0007287). The study has been approved by the institutional research ethics committee before experiment was started and that has been conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Helsinki Declaration. Participants were briefed on the purpose of the study and the measures taken to protect their privacy before conducting the study. All participants signed an informed consent form.

Participants

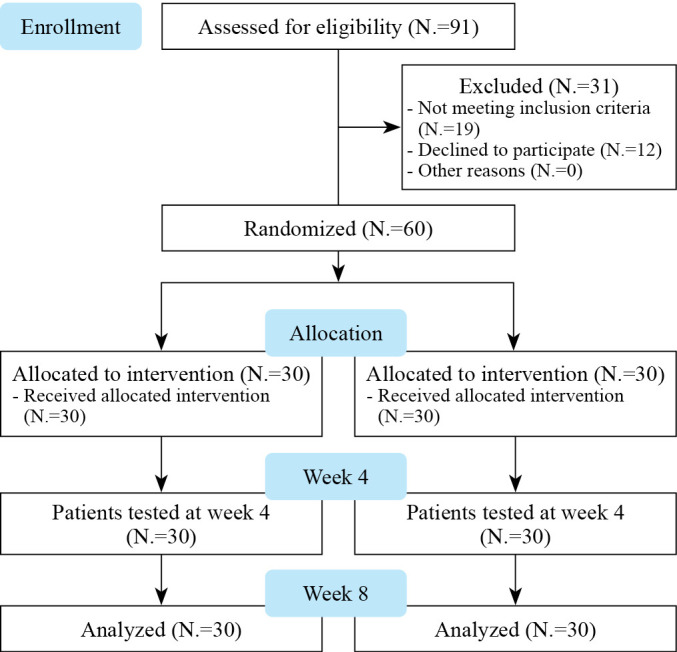

A total of 91 participants were enrolled in this study between May 2021 and July 2021. Individuals aged 60 years or older who were registered as dementia care subjects at the N-gu Public Health Center were included. Those with neuropsychiatric problems (excluding depression and anxiety), hearing or sight difficulties, a history of alcohol or drug abuse, and cognitive interventions within the previous 3 months were excluded. Of the 91 patients, 19 did not meet the inclusion criteria and 12 declined study participation. Finally, 60 patients (mean age 73.6 years, 66.7% female) were included in the study. These patients were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (N.=30) or the control group (N.=30) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

—Flow chart of the study.

Randomization and blinding

Simple randomization and concealed assignments were performed using computer-generated randomization tables before data collection. Participants were randomized into two groups: 1) intervention group; and 2) control group. The allocation sequence was concealed from the participants until the intervention was completed. To reduce bias, the control group was also given a tablet (Lenovo, 10.1 inches, 1920×1200; Lenovo Ltd, Beijing, China), blood pressure monitor (Omron, Japan), blood glucose meter (i-SENS; Korea, South Korea), weight scale (SolFit, Penrith, UK), and smartwatch (Story4you, Yongin, South Korea), and trained on basic device use.

Intervention

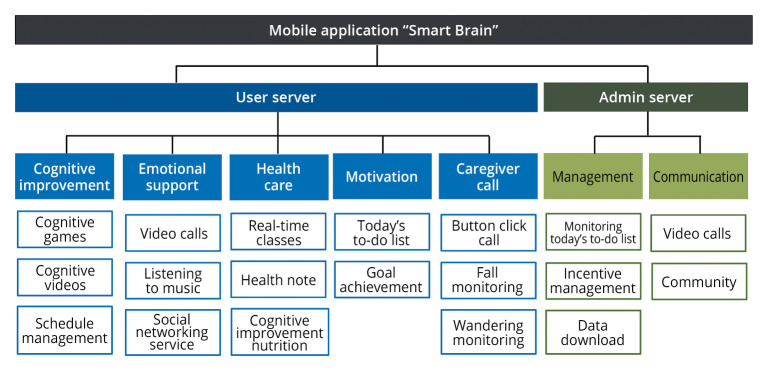

For 8 weeks from July 2022, a comprehensive cognitive program using a tablet, blood pressure monitor, blood glucose meter, and weight scale was applied to the intervention group five times a week for 30 to 50 min per session. According to the results of systematic literature reviews,22, 24 cognitive intervention for at least 6 weeks was effective, and an additional 2 weeks was calculated considering the adaptation period of older adults with dementia. The smart Brain program installed in the tablet is largely divided into motivation, cognitive improvement, healthcare, emotional support, and caregiver sections (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

—Information architecture of user and administrator server.

The motivation section includes a to-do list for the day and goal achievement. The to-do list consists of eight important missions among several programs over 8 weeks: six missions were performed Monday to Friday in turns (Table I), and five or more completed missions were awarded a stamp of completion. Patients could check the current status of stamps for goal achievement, and incentives were provided according to the number of stamps collected. Researchers could encourage patients by viewing the day’s to-do list or goal achievement status on the administrator’s server. The cognitive improvement component of the day’s to-do list consists of cognitive games and videos (Table I).

Table I. —A description of Smart Brain to-do list and its uses.

| Item | Times/week | Completion criteria | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive improvement part | Cognitive games | 3 | ≥30 min | Consists of five parts: concentration, memory, verbal thinking, time and space, and calculation |

| Cognitive videos | 4 | ≥30 min | Conducted cognitive exercises and played simple educational videos for the caregivers of patients with dementia | |

| Emotional support part | Listening to music | 5 | ≥5 min | Through a demand survey of 100 older adults, trot, hymns, and popular songs were played |

| Social networking service | 5 | One like or one post | Communication with other participants and administrators enabled | |

| Healthcare part | Real-time classes | 1 | ≥30 min | Conducted real-time cognitive function improvement exercises using a video call app that allowed bidirectional visualization |

| Meal record | 5 | Recording meal intake | Recorded the amount of food eaten by the participants in a day | |

| Nutrition video | 2 | ≥30 min | Played educational videos on essential nutrient intake and how to cook food | |

| Walk 7000 steps | 5 | ≥7000 steps or ≥40 min | Walking after wearing the smartwatch | |

Cognitive games were played thrice a week to improve concentration, memory, verbal thinking, time and space, and calculation. The game is designed such that it takes more than 30 min to complete all cognitive game missions for a day. When all the missions were completed, the patients could play additional games they wanted. The cognitive videos were made by specialists in older adults with dementia and included muscle strength exercises and cognitive function improvement exercises. The emotional support component consists of listening to music and social networking services (see Table I). Patients were asked to listen to music five times a week for five min or more, and they could choose the genre they wanted from among trots, hymns, and popular songs. On the social networking service, they had to express at least one “like” or upload one post five times a week. Patients could communicate with other patients and administrators and share their personal daily lives. The healthcare section consists of real-time classes, meal records, nutrition videos, and walk 7000 steps components (Table I). Real-time classes were held weekly, with each session lasting for more than 30 min. The administrator performed exercises that could improve dementia symptoms along with a song, and the patient followed the administrator by watching the screen. The administrator and the patient could see each other on the screen. Cognitive improvement nutrition includes meals and nutritional records. The meal records provided an automatic alarm every evening to record daily meal intake. The contents recorded by the patients were checked on the administrator’s screen and used as feedback. Nutritional videos related to essential nutrient intake and food recipes were watched twice a week for 30 min. The walk 7000 steps component involved a daily requirement for older adults with dementia to walk more than 7000 steps after wearing a smartwatch or for people with walking difficulties to walk for more than 40 min. Both the intervention group and the control group were trained at the same date as baseline measurements. The control group was instructed on how to turn the tablet on and off and how to use the blood pressure monitor and blood sugar meter. Additionally, leaflets on the characteristics of dementia, proper eating habits, and communication skills were provided. The control group underwent intervention after 8 weeks of retraining. In addition to this, the intervention group was specifically trained on how to use the Smart Brain program, including the day’s to-do list and goal achievement system.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of this study was cognitive function measured using the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination 2: Standard Version (K-MMSE~2: SV), which was developed and translated by Kang et al.25 based on Mini-Mental State Examination 2 (MMSE-2) developed by Folstenin et al.26 tool was used. The K-MMSE~2:SV consists of seven items: memory registration (3 points), time orientation (5 points), place orientation (5 points), memory recall (3 points), attention and calculation (5 points), language (8 points), and drawing (1 point). The total score is 30 points, with a higher score indicating higher cognitive function. The secondary outcomes included depression, quality of life, balance confidence, physical ability, nutritional status, and caregivers’ burden, measured using the Short Form of Geriatric Depression Scale-Korean (SGDS-K), Euro-Quality of Life-5 Dimension (EQ-5D), Activities-Specific Balance Confidence (ABC) scale, Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA), and Korean version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-K). Based on the SGDS produced by Sheikh et al., the tool translated by Maeng et al.27 was used. The total score is 15 points; the higher the score, the higher the level of depression.28 The EQ-5D is a five-item tool developed to measure health-related quality of life and consists of five items. Each item is scored on a 5-point scale, with a total score of one point.29 The ABC scale was developed by Powell et al.30 and translated by Jang et al.31 It consists of 16 questions, each of which can be scored from 0% (not at all confident) to 100% (completely confident), and the average of all questions is calculated. The TUG test measures the time from sitting in a chair to standing up with a signal, turning around the target point 3 m ahead, and sitting on the chair again. The MNA was developed by Rubenstein et al.32 and is an easy and quick tool to screen older adults. The total score is 15 points, and the higher the score, the better the patient’s nutritional status. The ZBI was developed by Zarit et al.33 and translated by Bae et al.34 was used. The total possible score is 88 points: the higher the score, the greater the burden of support. All assessments were performed in the same week for both the intervention group and control groups: baseline (week 0), week 4, and week 8.

Sample size

To determine the sample size, G power 3.1.9.7 software (Helsinki Heine University, Dusseldorf, Germany) was used. To calculate the sample size, the probability of alpha error and power were set at 0.05 and 0.95, respectively. In addition, a moderate effect size (0.25 was set based on Cohen’s method.35 Therefore, a sample size of 44 participants was required. A total of 25% of the participants were recruited in case of unanticipated attrition.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed based on an intent-to-treat principle using the IBM SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data are summarized as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The normality of the distribution was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. Pearson’s χ2 and independent t-tests were conducted for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, to compare the general characteristics of the participants and baseline data between the groups. To analyze the average differences between groups and time, a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted for cognitive function, depression, quality of life, balance confidence, physical ability, nutrition, and caregiver burden. A paired t-test was used to compare changes over time at baseline. Subgroup analysis was performed by dividing the active group with more than 30% participation into the intervention group and the inactive group with less than 30% participation. The statistical significance level was set at P=0.05.

Results

Of the 91 participants, 31 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria or refused to participate. Thirty participants were randomized into either the intervention group (N.=30) or the control group (N.=30). There were no dropouts. There were no serious side effects, but in rare cases the device was disconnected or lost. A repair technician personally visited the participant, inspected the condition of the device, solved the problem, and provided device back. The baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table II).

Table II. —Baseline characteristics of study participants.

| Intervention group (N.=30) |

Control group (N.=30) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73.87±6.15 | 73.27±6.92 | 0.724 |

| Women, N. (%) | 20 (66) | 20 (66) | >0.99 |

| National long-term care insurance, N. (%) | 0.983 | ||

| None | 16 (53) | 16 (53) | |

| Cognitive support | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | |

| Level 5 | 7 (23) | 6 (20) | |

| Level 4 | 5 (17) | 6 (20) | |

| Education, N. (%) | 0.840 | ||

| Illiterate | 5 (16) | 7 (23) | |

| Elementary school | 13 (43) | 13 (43) | |

| Middle school | 6 (20) | 3 (10) | |

| High school | 5 (16) | 6 (20) | |

| ≥ College | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Living state, N. (%) | 0.901 | ||

| Alone | 8 (27) | 8 (27) | |

| With spouse | 13 (43) | 14 (47) | |

| With spouse and children | 3 (10) | 4 (13) | |

| With children, without spouse | 6 (20) | 4 (13) | |

| Taking medication for dementia, N. (%) | >0.99 | ||

| Yes | 22 (27) | 8 (73) | |

| No | 22 (27) | 8 (73) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.12±4.10 | 22.88±2.79 | 0.177 |

| MMSE | 19.50±4.47 | 18.73±4.48 | 0.510 |

| SGDS | 7.77±3.79 | 6.57±4.53 | 0.270 |

| ABC | 59.29±23.28 | 56.48±24.20 | 0.648 |

| TUG | 12.18±3.26 | 12.09±3.29 | 0.915 |

| EQ-5D | 0.70±0.16 | 0.70±0.20 | 0.908 |

| MNA | 9.00±2.26 | 8.17±2.65 | 0.195 |

| Intervention group (N.=24) |

Control group (N.=26) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZBI (only for caregiver) | 32.38±16.62 | 38.50±20.56 | 0.255 |

ABC: Activities-Specific Balance Confidence; BMI: Body Mass Index; EQ-5D: Euro-Quality of Life-5 Dimension; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA: Mini-Nutritional Assessment; SGDS: Short Form of Geriatric Depression Scale; TUG: Timed Up and Go.

The average age of the participants was 73.57 years (SD=6.50), and the mean Body Mass Index was 23.5 kg/m2, with 40 women (66.0%) and 20 men (34.0%). There was no difference in the long-term care insurance grade, which provides services for substantial activities and daily life support to those who have difficulty performing daily life by themselves because of old age or geriatric disease, educational background, residence status, or medication for dementia. The initial K-MMSE~2, SGDS, EQ-5D, ABC, TUG, and MNA scores were 19.12 (SD=4.45), 7.17 (SD=4.18), 0.70 (SD=0.18), 57.89 (SD=23.59), 12.14 (SD=3.25), and 8.58 (SD=2.48), respectively. The primary and secondary outcomes of the intervention are shown in Table III.

Table III. —Primary and secondary outcomes.

| Mean±SD | Change from baseline, mean (95% CI) | Time × group interaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 4 | Week 8 | ||

| MMSE | <0.001 | ||||

| Intervention | 21.53±4.90 | 22.20±4.46 | 2.03 (1.26 to 2.81) | 2.70 (1.76 to 3.64) | |

| Control | 17.60±4.20 | 16.57±5.10 | -1.13 (-1.91 to 0.36) | -2.17 (-3.25 to -1.08) | |

| SGDS | 0.001 | ||||

| Intervention | 7.27±3.81 | 6.10±3.90 | -0.50 (-1.53 to 0.53) | -1.67 (-2.85 to -0.48) | |

| Control | 6.67±4.33 | 7.60±4.65 | 0.10 (-0.90 to 1.10) | 1.03 (-0.22 to 2.29) | |

| EQ-5D | 0.130 | ||||

| Intervention | 0.71±0.17 | 0.73±0.19 | 0.01 (-0.05 to 0.08) | 0.02 (-0.05 to 0.10) | |

| Control | 0.72±0.17 | 0.66±0.20 | -0.01 (-0.03 to 0.06) | -0.05 (-0.12 to 0.03) | |

| ABC | 0.129 | ||||

| Intervention | 63.79±24.23 | 64.10±26.00 | 4.50 (-1.68 to 10.68) | 4.81 (-4.50 to 14.12) | |

| Control | 54.58±25.53 | 50.77±25.91 | -1.90 (-9.03 to 5.23) | -5.71 (-14.46 to 3.04) | |

| TUG | <0.001 | ||||

| Intervention | 11.34±3.11 | 10.74±3.35 | -0.85 (-1.49 to -0.20) | -1.44 (-2.29 to -0.59) | |

| Control | 12.97±3.34 | 14.27±3.70 | 0.86 (0.29 to 1.46) | 2.18 (0.27 to 3.08) | |

| MNA | 0.022 | ||||

| Intervention | 9.67±1.77 | 10.10±1.52 | 0.67 (0.05 to 1.28) | 1.10 (0.36 to 1.84) | |

| Control | 8.43±2.16 | 8.00±2.35 | 0.27 (-0.30 to 0.83) | -0.17 (-0.93 to 0.60) | |

| ZBI | 0.003 | ||||

| Intervention | 36.46±19.84 | 31.71±14.16 | 4.08 (-2.86 to 11.03) | -0.67 (-5.16 to 3.83) | |

| Control | 44.77±20.16 | 49.96±23.20 | 6.30 (2.00 to 10.54) | 11.46 (5.48 to 17.45) | |

ABC: Activities-Specific Balance Confidence; EQ-5D: Euro-Quality of Life-5 Dimension; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MNA: Mini-Nutritional Assessment; SGDS: Short Form of Geriatric Depression Scale; TUG: Timed Up and Go; ZBI: Zarit Burden Interview.

The average ZBI score was 35.65 (SD=18.84), with no statistically significant difference between the two groups. The ZBI was not measured for accuracy when the main caregiver changed during the study period or could not visit the public health center.

Comparative effect (intervention vs. control group)

The intervention group showed statistically significant differences in MMSE (P<0.001), SGDS (P=0.001), TUG (P<0.001), MNA (P=0.022), and ZBI (P=0.003) scores. However, the EQ-5D (P=0.130) and ABC (P=0.129) scores were not statistically significant (Table III). The MMSE score statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (2.03; 95% CI 1.26 to 2.81) and week 8 (2.70; 95% CI 1.76 to 3.64). The SGDS score showed no statistical difference from week 0 to week 4 (-0.50; 95% CI -1.53 to 0.53) but showed a statistical difference from week 0 to week 8 (-1.67; 95% CI -2.85 to -0.48). The TUG score statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (-0.85; 95% CI -1.49 to -0.20) and week 8 (-1.44; 95% CI -2.29 to -0.59). The MNA score statistically increased from baseline to both week 4 (0.67; 95% CI 0.05 to 1.28) and week 8 (1.10; 95% CI 0.36 to 1.84). The ZBI score showed no statistical difference from week 0 to week 4 (4.08; 95% CI -2.86 to 11.03) but was statistically different from week 0 to week 8 (-0.67; 95% CI -5.16 to -3.83). The EQ-5D score indicated no statistically significant improvement, but the intervention group score tended to increase from baseline to week 4 (0.02; 95% CI -0.05 to 0.08) and week 8 (0.02; 95% CI -0.05 to 0.10), whereas that of the control group tended to decrease. The ABC score also indicated no statistically significant improvement in the time-by-group interaction, but the intervention group score tended to increase from baseline to week 4 (4.50; 95% CI -1.68 to 10.68) and week 8 (4.81; 95% CI -4.50 to 14.12), whereas that of the control group tended to decrease.

Subgroup analysis by program participation (active vs. inactive group)

Regarding listening to music, the active group showed no difference in the SGDS score between baseline and week 4 (3.23; 95% CI -0.99 to 2.59), but a statistically significant decrease at week 8 (3.42; 95% CI 0.57 to 4.36). Regarding cognitive videos, the active group showed no difference in the TUG score between baseline and week 4 (1.81; 95% CI -0.30 to 1.80), but a statistically significant increase at week 8 (2.23; 95% CI 0.39 to 2.97). Regarding meal records, the active group showed a statistically significant increase in the MNA score from baseline to both week 4 (1.31; 95% CI 0.29 to 1.54) and week 8 (1.98; 95% CI 0.14 to 2.43). Table IV presents the results of the study.

Table IV. —Subgroup analysis according to program participation.

| Mean±SD | Change from baseline, mean (95% CI) | Time × group interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 8 | Week 4 | Week 8 | ||

| Listening to music- SGDS | 0.278 | |||||

| Active group (N.=15) | 8.40±3.92 | 7.60±3.87 | 5.93±4.28 | 3.23 (-0.99 to 2.59) | 3.42 (0.57 to 4.36) | |

| Inactive group (N.=15) | 7.13±3.66 | 6.93±3.85 | 6.27± 3.63 | 2.27 (-1.06 to 1.46) | 2.77 (-0.67 to 2.40) | |

| Cognitive videos-TUG | 0.592 | |||||

| Active group (N.=14) | 12.82±3.62 | 12.07±3.62 | 11.13±3.62 | 1.81 (-0.30 to 1.80) | 2.23 (0.39 to 2.97) | |

| Inactive group (N.=16) | 11.63±2.91 | 10.70±2.54 | 10.40±3.18 | 1.70 (0.02 to 1.84) | 2.35 (-0.03 to 2.48) | |

| Meal record-MNA | 0.865 | |||||

| Active group (N.=14) | 8.71±2.43 | 9.50±2.10 | 10.00±1.71 | 1.31 (0.29 to 1.54) | 1.98 (0.14 to 2.43) | |

| Inactive group (N.=16) | 9.25±2.15 | 9.81±1.47 | 10.19±1.38 | 1.93 (-0.46 to 1.59) | 2.02 (-0.14 to 2.01) | |

MNA: Mini-Nutritional Assessment; SGDS: Short Form of Geriatric Depression Scale; TUG: Timed Up and Go.

Discussion

In this study, an 8-week application of a comprehensive cognitive improvement program, Smart Brain, to community-dwelling older adults with dementia was effective in improving cognitive function, depression, physical ability, nutritional status, and caregiver burden. We confirmed that Smart Brain, a comprehensive cognitive training system, served as a customized system that could be used at home by older adults with dementia, enabling continued social participation and providing motivation.

Effects on cognitive function

First, cognitive function improved when Smart Brain was used for community-dwelling older adults with dementia. This finding is consistent with the results of previous studies on older adults with dementia.17, 36 However, whereas the study by Byeon was conducted in a facility, the current study was conducted at home. The quality of life and physical function of older adults with dementia are better and they are more socially connected when cared for at home than at a facility.37 Therefore, intervention through the Smart Brain will be helpful not only for the emotional aspect of older adults with dementia but also for those who do not want to use daycare centers or who experience inconvenience in moving. In addition, in the study by Lee et al., if some participants had difficulty playing the game, the therapist should have provided additional guidance and support. In contrast, the Smart Brain’s cognitive game has an advantage in that the level is automatically adjusted according to the patient’s cognitive level. Automatic adjustment of the difficulty of the cognitive game according to the level of cognitive function will induce older adults with dementia not to lose interest and reduce the burden of individual guidance.

Effects on depression

Depression decreased when Smart Brain was used for community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Unlike the results of this study, another study38 that used wearable devices to help older adults with dementia in their daily lives found that depression decreased after a week, although there was no statistically significant difference after 6 months. Patients with dementia are likely to be excluded from social roles and activities owing to memory loss and difficulty remembering names and recent events;39 however, they also seek opportunities to participate in meaningful activities.40 Therefore, a comprehensive intervention is needed rather than simply supplying devices or emotional management using devices. The reason why Smart Brain improved depression in older adults with dementia is that it enabled patients to participate in various activities and maintain social exchanges by using social networking services and real-time programs for interactive communication. In addition, the active group in the music-listening program showed a greater decrease in depression. This suggests that music programs should be actively utilized when developing an upgraded Smart Brain model. Participants provided feedback on the use of listening to music, which will be reflected and applied to the Smart Brain model in the future.

Effects on physical ability

Physical ability measured by the TUG test was improved using Smart Brain for community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Similar results have been reported in previous studies through health management.19, 20 Thapa et al. also found an improvement in physical ability and cognitive function, but older adults with vertigo or otolaryngologic problems could not participate in the virtual reality-based program. Vertigo is a common phenomenon in older adults. By 75 years of age, approximately one-third of older adults complain of balance disorders or dizziness, which increases with age.41, 42 Therefore, considering the characteristics of older adults, more older adults with dementia can use Smart Brain programs rather than virtual reality-based programs. In a study by Kwan et al., people who walked a lot originally participated, while those who had difficulty in physical activity did not participate. However, Smart Brain provided a video that could be followed in a sitting position to improve the strength and cognition of older adults with walking difficulties. In addition, subgroup analysis confirmed that the active group, which performed better in the cognitive videos, had better physical abilities. The advantage of Smart Brain is that not only older adults with dementia who can perform normal activities but also older adults who are physically vulnerable can participate.

Effects on nutritional status

The nutritional scores of community-dwelling older adults with dementia were improved using Smart Brain. In the study by de Souto Barreto et al.,21 participants watched a video and, if necessary, were provided nutritional advice directly; however, there was no statistically significant difference in nutritional status. With Smart Brain, participants were allowed to record their nutrition every day while watching nutrition educational videos, and they were able to provide simple feedback when they completed the nutrition record. Unlike the study by de Souto Barreto et al.,21 older adults with dementia could participate more actively in the program by recording their nutritional intake. Older adults with dementia responded positively to self-recordings and simple feedback, which led to an increase in nutritional scores. The nutritional score of the active group, which had a high participation rate in nutrition records, was higher than that of the inactive group.

Effect of today’s to-do list

There are various motivation systems, such as the day’s to-do list, which was advantageous in Smart Brain for community-dwelling older adults with dementia. In one study, participants were allowed to use the program freely and there was no statistically significant outcome.43 Conversely, in Smart Brain, the to-do list was given every day from Monday to Friday, and participants could directly check whether there was a completion stamp. The day’s to-do list was created with customized based on participants preferences and feedback when designing application to increase user participation. This system played a significant role in making participants feel more connected to the tasks, enhancing their engagement. Goals were set through professional discussions with public health center dementia experts, exercise prescribers, and nurses, and they monitored the achievement of goals on the administrator page and provided feedback. In addition, participants were able to check how many goals they had achieved on the day’s to-do list and were able to self-monitoring and self-evaluation on a weekly basis. This professional involvement ensured that the goals were tailored to each participant’s capabilities and health status, thereby enhancing the program’s effectiveness and relevance. This feature was important for promoting self-directed learning and engagement, as participants could visually see their achievements through the number of completion stamps received and regular feedback provided by the administrators. The motivational impact of these features was highlighted in the postintervention satisfaction survey, where participants identified receiving the completion stamp and the pop-up reminders as the most motivating factors. This feedback underscores the effectiveness of incorporating user preferences, professional guidance, and self-monitoring mechanisms in enhancing user engagement and participation. Through this system, participants could see visualized data and were motivated to achieve their goals. Participants considered the effects of the program on their health and reinforce behavior change. Therefore, data and actions circulated positively, leading to positive results. There were no dropouts in this study, possibly because the motivational systems serve as means to enhance the achievement and self-esteem among older adults with dementia, thereby maximizing the effectiveness of Smart Brain in this study.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of this study is that it used a comprehensive cognitive training program that specialized in social communication. Although a previous study21 reported on multi-domain interventions, they focused on providing interventions and feedback to participants. However, Smart Brain is not only a comprehensive cognitive training program but can also communicate with older adults, caregivers, and managers to encourage social participation. In addition, the motivational system led to patient participation, and the dropout rate was low compared to that in other studies.21, 43 In future studies, when upgrading the Smart Brain or conducting other studies, motivation systems should be actively utilized. Nevertheless, this study has a few limitations. Owing to the small sample size, further studies should be conducted with larger sample sizes to achieve more clinically significant results. Additionally, the intervention period was short; therefore, long-term studies should be conducted. Finally, there was a difference in the participation rate between the active and inactive groups. Since there are still many older adults who are unfamiliar with smart devices or have difficulty using devices, face-to-face and non-face-to-face interventions should be combined.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed that comprehensive cognitive training using Smart Brain for 8 weeks improved cognitive function, depression, physical ability, and nutritional status of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and reduced the burden on caregivers. Therefore, Smart Brain can be widely applied to community-dwelling older adults with dementia. This will enable community nurses to manage patients with dementia more effectively. However, future research needs to be conducted with a longer duration and larger sample size to achieve more clinically significant results.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI21C0575).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia; 2021 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia1 [cited 2024, Apr 8].

- 2.Mielke MM, Leoutsakos JM, Corcoran CD, Green RC, Norton MC, Welsh-Bohmer KA, et al. Effects of Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for Alzheimer’s disease on clinical progression. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:180–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22301194&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epperly T, Dunay MA, Boice JL. Alzheimer Disease: Pharmacologic and Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Cognitive and Functional Symptoms. Am Fam Physician 2017;95:771–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28671413&dopt=Abstract [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyer SM, Harrison SL, Laver K, Whitehead C, Crotty M. An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30:295–309. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=29143695&dopt=Abstract 10.1017/S1041610217002344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lissek V, Suchan B. Preventing dementia? Interventional approaches in mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021;122:143–64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33440197&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballard C, Khan Z, Clack H, Corbett A. Nonpharmacological treatment of Alzheimer disease. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:589–95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22014691&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/070674371105601004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cammisuli DM, Danti S, Bosinelli F, Cipriani G. Non-pharmacological interventions for people with Alzheimer’s Disease: A critical review of the scientific literature from the last ten years. Eur Geriatr Med 2016;7:57–64. 10.1016/j.eurger.2016.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcus BH, Nigg CR, Riebe D, Forsyth LH. Interactive communication strategies: implications for population-based physical-activity promotion. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:121–6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=10913903&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00186-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nigg CR. Technology’s influence on physical activity and exercise science: the present and the future. Psychol Sport Exerc 2003;4:57–65. 10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00017-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kueider AM, Parisi JM, Gross AL, Rebok GW. Computerized cognitive training with older adults: a systematic review. PLoS One 2012;7:e40588. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22792378&dopt=Abstract 10.1371/journal.pone.0040588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neal D, van den Berg F, Planting C, Ettema T, Dijkstra K, Finnema E, et al. Can Use of Digital Technologies by People with Dementia Improve Self-Management and Social Participation? A Systematic Review of Effect Studies. J Clin Med 2021;10:604. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33562749&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/jcm10040604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramaniam P, Woods B. Digital life storybooks for people with dementia living in care homes: an evaluation. Clin Interv Aging 2016;11:1263–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=27698556&dopt=Abstract 10.2147/CIA.S111097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peretti A, Amenta F, Tayebati SK, Nittari G, Mahdi SS. Telerehabilitation: Review of the State-of-the-Art and Areas of Application. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2017;4:e7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28733271&dopt=Abstract 10.2196/rehab.7511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park K, Lee S, Yang J, Song T, Hong GS. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of reminiscence therapy for people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 2019;31:1581–97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=30712519&dopt=Abstract 10.1017/S1041610218002168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts R, Knopman DS. Classification and epidemiology of MCI. Clin Geriatr Med 2013;29:753–72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24094295&dopt=Abstract 10.1016/j.cger.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savulich G, Piercy T, Fox C, Suckling J, Rowe JB, O’Brien JT, et al. Cognitive Training Using a Novel Memory Game on an iPad in Patients with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (aMCI). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:624–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28898959&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ijnp/pyx040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee GY, Yip CC, Yu EC, Man DW. Evaluation of a computer-assisted errorless learning-based memory training program for patients with early Alzheimer’s disease in Hong Kong: a pilot study. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:623–33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=23766638&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard R, Gathercole R, Bradley R, Harper E, Davis L, Pank L, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of assistive technology and telecare for independent living in dementia: a randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 2021;50:882–90. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33492349&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/ageing/afaa284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwan RY, Lee D, Lee PH, Tse M, Cheung DS, Thiamwong L, et al. Effects of an mHealth brisk walking intervention on increasing physical activity in older people with cognitive frailty: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8:e16596. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32735218&dopt=Abstract 10.2196/16596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thapa N, Park HJ, Yang JG, Son H, Jang M, Lee J, et al. The effect of a virtual reality-based intervention program on cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A randomized control trial. J Clin Med 2020;9:1283. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=32365533&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/jcm9051283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Souto Barreto P, Pothier K, Soriano G, Lussier M, Bherer L, Guyonnet S, et al. A web-based multidomain lifestyle intervention for older adults: the eMIND randomized controlled trial. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2021;8:142–50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33569560&dopt=Abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chae HJ, Lee SH. Effectiveness of online-based cognitive intervention in community-dwelling older adults with cognitive dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2023;38:e5853. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=36468299&dopt=Abstract 10.1002/gps.5853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung AR, Kim D, Park EA. Cognitive intervention using information and communication technology for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:11535. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=34770049&dopt=Abstract 10.3390/ijerph182111535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pang SH, Lim SF, Siah CJ. Online memory training intervention for early-stage dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2021;77:1141–54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33259701&dopt=Abstract 10.1111/jan.14664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang YW, Jahng SM, Kim SY; Korean Dementia Association. Korean-Mini Mental State Examination, 2nd Edition (K-MMSE~2) user’s guide. Seoul: Korean Dementia Association; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein M, Folstein S, White T, Messer M. MMSE-2: Mini-mental state examination. Second Edition. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho MJ, Bae JN, Suh GH, et al. Validation of Geratric Depression Sclae, Korean Version (GDS) in the Assessment of DSM-III-R Major Depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1999;38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol 1986;5:165–73. 10.1300/J018v05n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Group E. EQ-5D-5L; 2021 [Internet]; Available from: https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/ [cited 2024, Apr 8].

- 30.Powell LE, Myers AM. The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A:M28–34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7814786&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/gerona/50A.1.M28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jang SN, Cho SI, Ou SW, Lee ES, Baik HW. The validity and reliability of Korean fall efficacy scale (FES) and activities-specific balance confidence scale (ABC). J Korean Geriatr Soc 2003;7:255–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M366–72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=11382797&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/gerona/56.6.M366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist 1980;20:649–55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=7203086&dopt=Abstract 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bae K. Care burden of caregivers according to cognitive function of older persons. J Korean Soc Biol Ther Psychiatry 2006;12:66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen J. Stafisfical power analysis for the social sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byeon H. The effect of computer based cognitive rehabilitation program on the improvement of generative naming in the elderly with mild dementia: preliminary study. J Korea Converg Soc. 2019;10:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikmat AW, Hawthorne G, Al-Mashoor SH. The comparison of quality of life among people with mild dementia in nursing home and home care—a preliminary report. Dementia (London) 2015;14:114–25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=24339093&dopt=Abstract 10.1177/1471301213494509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva AR, Pinho MS, Macedo L, Moulin C, Caldeira S, Firmino H. It is not only memory: effects of sensecam on improving well-being in patients with mild alzheimer disease. Int Psychogeriatr 2017;29:741–54. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=28124633&dopt=Abstract 10.1017/S104161021600243X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Batsch N, Mittelman M. World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia; 2012 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf [cited 2024, Apr 8].

- 40.Mountain GA, Craig CL. What should be in a self-management programme for people with early dementia? Aging Ment Health 2012;16:576–83. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=22360274&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/13607863.2011.651430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernández L, Breinbauer HA, Delano PH. Vertigo and Dizziness in the Elderly. Front Neurol 2015;6:144. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=26167157&dopt=Abstract 10.3389/fneur.2015.00144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jönsson R, Sixt E, Landahl S, Rosenhall U. Prevalence of dizziness and vertigo in an urban elderly population. J Vestib Res 2004;14:47–52. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=15156096&dopt=Abstract 10.3233/VES-2004-14105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beentjes KM, Neal DP, Kerkhof YJ, Broeder C, Moeridjan ZD, Ettema TP, et al. Impact of the FindMyApps program on people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia and their caregivers; an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol 2023;18:253–65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&list_uids=33245000&dopt=Abstract 10.1080/17483107.2020.1842918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]