Abstract

Purpose.

Cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) are associated with increased risk for cognitive impairment and decline in the general population, but less is known about how CVRFs might influence cognitive aging among older cancer survivors. We aimed to determine how CVRFs prior to a cancer diagnosis affect post-cancer diagnosis memory aging, compared to cancer-free adults, and by race/ethnicity.

Methods.

Incident cancer diagnoses and memory (immediate and delayed recall) were assessed biennially in the US Health and Retirement Study (N=5,736, 1998–2018). CVRFs measured at the wave prior to a cancer diagnosis included self-reported cigarette smoking, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and stroke. Multivariable-adjusted linear mixed-effects models evaluated the rate of change in standardized memory score (SD/decade) post-cancer diagnosis for those with no, medium, and high CVRFs, compared to matched cancer-free adults, overall and stratified by sex and race/ethnicity.

Results.

Higher number of CVRFs was associated with worse baseline memory for both men and women, regardless of cancer status. Cancer survivors with medium CVRFs had slightly slower rates of memory decline over time relative to cancer-free participants (0.04 SD units/decade [95% CI: 0.001, 0.08]). Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) and Hispanic cancer-free participants and cancer survivors had worse baseline memory than their Non-Hispanic White (NHW) counterparts.

Conclusions.

CVRFs were associated with worse baseline memory function, but not decline, for cancer-free adults and cancer survivors. Racial disparities were largely similar between cancer survivors and cancer-free adults.

Implications for Cancer Survivors.

These findings may inform hypotheses about pre-diagnosis multimorbidity and cognitive aging of cancer survivors from diverse groups.

Keywords: memory, cognitive impairment, cancer survivors, cardiovascular risk factors, racial disparities

Introduction

Cancer survivors often experience cognitive decline after diagnosis and treatment [1, 2]. Up to 75 percent of cancer survivors experience cognitive impairment during treatment, and up to 35 percent report experiencing lasting cognitive effects after the completion of their cancer treatment [3]. The reasons for cognitive impairment among cancer survivors are not fully understood, but may be related to cancer treatment, psychological factors associated with a cancer diagnosis, or comorbidities prior to a cancer diagnosis, all of which may interact with the experience of a cancer diagnosis and treatment to place cancer survivors at higher risk of subsequent cognitive impairment [2,4].

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and obesity are known cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs) for cognitive impairment and decline in the general population [5–8]. CVRFs may affect cognitive function by increasing inflammation and oxidative stress, which can disrupt cerebral blood flow and impair the blood-brain barrier [6,9]. In addition, many cancer treatments have cardiotoxic properties, which could exacerbate pre-existing cardiovascular disease and increase the risk for cognitive dysfunction among aging cancer survivors [10]. Although cancer survivors with CVRFs may possibly have lower cognitive function prior to diagnosis and heightened vulnerability to cognitive impairment following diagnosis, few studies have investigated the role of CVRFs in the cognitive function of older cancer survivors. Von Ah and colleagues found participants in a small cohort study of breast cancer survivors who had pre-existing cardiovascular disease were at greater risk for cognitive dysfunction after their cancer treatment [11]. However, no other studies have examined the role of CVRFs in the cognitive aging of middle-aged and older cancer survivors in a population-based cohort study and explored potential differences by sex and race/ethnicity.

CVRFs may also play an important role in health disparities amongst aging cancer survivors. Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) and Hispanic Americans are disproportionately more likely to develop and die from cancer, have a higher prevalence of CVRFs, and experience higher incidence of cognitive impairment and decline relative to non-Hispanic White (NHW) Americans [12–14]. There is also emerging evidence that NHB and Hispanic individuals are disproportionately affected by cancer-related cognitive decline, relative to their NHW counterparts [15,16]. NHB and Hispanic Americans may be more vulnerable to cognitive changes after a cancer diagnosis due to greater prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities prior to a cancer diagnosis [17–19]. However, as few studies have investigated the relationship between CVRFs and memory aging among older cancer survivors, it is unknown if this relationship differs by race/ethnicity, which limits our understanding of the contributors to health disparities among cancer survivors. Given the increasing prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, the growing cancer survivorship population, and significant racial disparities in cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment, this is a critical gap in the literature that requires further investigation [19–22].

Therefore, in an ongoing, population-based longitudinal cohort study of older adults in the United States, we aimed to determine how prevalent CVRFs prior to a cancer diagnosis may impact subsequent memory aging after a cancer diagnosis, and if this relationship varies by cancer status, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Methods

Study population

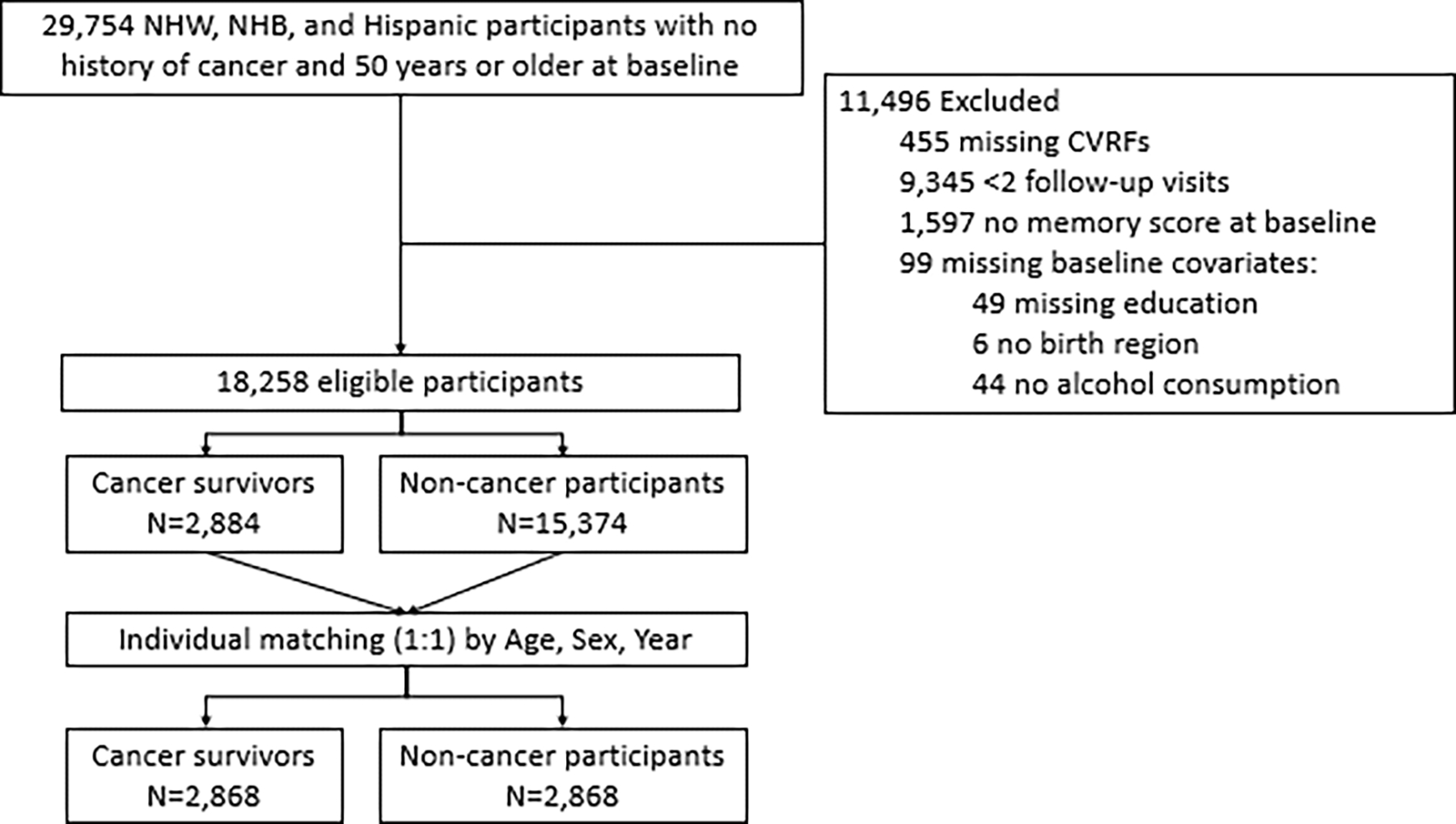

Data were from biennial interviewers with adults >50 years at baseline in the population-based US Health and Retirement Study (HRS) from 1998 to 2018. [23]. Data on incident cancer, cardiovascular risk factors, memory function, and covariates were assessed biennially from 1998 to 2018 via telephone and in-person interviews. We used the study interview wave prior to a reported cancer diagnosis as the baseline for those with cancer. Individuals with an incident cancer diagnosis were then matched to cancer-free individuals (those who did not have a cancer diagnosis over the follow-up period) in the same wave as their matched cancer survivor based on age and sex. Matching cancer survivors with cancer-free participants allowed for the estimation of how memory aging differs among those with an incident cancer diagnosis compared to memory aging of cancer-free individuals of similar age and sex. Eligible participants were aged 50 and above, with a minimum of two follow-up visits after the baseline, complete baseline covariates, and self-identified as NHW, NHB, or Hispanic. The final analytic sample was 5,736 participants, distributed between the cancer survivor cohort (N=2,868) and the matched cancer-free cohort (N=2,868) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for sample selection

Measures

Incident cancer was assessed in each biennial study interview as a new self-reported physician diagnosis of a cancer or malignant tumor, excluding non-melanoma skin cancers. Month and year of diagnosis were collected.

Memory was assessed at each biennial study interview as immediate and delayed recall of a 10-word list, whereby one point was attributed to each correctly recalled word, for a total of 20 points [24]. Proxy respondents were excluded from the analysis. We standardized memory scores at each follow-up time point using the baseline sample mean and standard deviation (SD), therefore analyses present rates of memory change relative to the baseline distribution.

Cardiovascular risk factors.

Informed by evidence from prior epidemiologic studies on CVRFs and cognitive decline [9, 19, 25–28], we defined the CVRFs of interest based on study interview measures of self-reported current cigarette smoking (yes; no), obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2, as measured by trained study interviewers) and physician-diagnosed diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and hypertension (yes; no for each). We categorized the number of CVRFs as no CVRFs (0), medium CVRFs (1, 2), and high CVRFs (≥3), consistent with previous literature [8]. CVRFs were assessed at baseline, defined as the study interview prior to each reported cancer diagnosis for cancer survivors, as well as for their matched cancer-free counterpart.

Race/ethnicity.

Self-identified race/ethnicity was collected and was categorized as NHW, NHB, and Hispanic. Due to small sample sizes (<2% of the sample), participants who reported another race were excluded.

Covariates.

Informed by prior studies of cognitive outcomes in the HRS [5,6,9,28,29], potential confounders of the relationship between CVRFs and rate of memory change were age (continuous, decades), quadratic age to account for non-linear memory aging slopes [29], and the following covariates assessed at the study interview prior to each reported cancer diagnosis: self-reported sex (male; female), educational attainment (less than high school, high school, college, and graduate school), alcohol consumption according to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism definitions (none, low risk, binge), and southern US birthplace (as defined by Census regions including locations: Maryland, Delaware, the District of Columbia, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) to account for early-life exposure to Jim Crow policies (yes; no) [30].

Statistical analyses

Differences in baseline characteristics by CVRFs for participants with and without a new cancer diagnosis over the follow-up were described using chi square statistics for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. We used multivariable-adjusted linear mixed effects models to describe longitudinal memory score trajectories. Individual participants’ memory intercepts and slopes were allowed to vary as random effects. The covariance structure of random effects was coded as unstructured, allowing the correlation between intercepts and slopes to be estimated.

The primary timescale, age at each study interview, centered at 65, described the average rate of memory decline per decade of age for participants with no cancer and no CVRFs over the follow-up period. To estimate differences in memory over time for participants with medium/high CVRFs and for those who developed cancer, we estimated a model with interaction terms between CVRFs, age, and cancer status. We included three interaction terms: (1) cancer status and CVRFs, to determine the differences in baseline memory scores across CVRF categories for cancer survivors compared to those without cancer; (2) age since baseline and CVRFs to determine the overall memory aging slopes for cancer-free individuals across CVRF categories; and (3) age since baseline and cancer status and CVRFs (a three-way interaction) to determine the differences in long-term memory slopes across CVRF categories for cancer survivors, compared to those observed among cancer-free individuals. We re-ran the model with interaction terms between CVRFs and cancer status first stratified by sex and then stratified by race/ethnicity. Due to small sample sizes within CVRFs categories, we estimated the same models as above using the continuous value of the number of CVRFs (range 0 to 6). Finally, we conducted a secondary analysis in which we re-estimated separate models using each individual CVRFs (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, current smoking, BMI, and stroke). All models adjusted for the potential confounders described above. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) and StataSE 17.0 (College Stations, TX).

Results

Sample characteristics by cancer status and CVRFs

There was a total of 5,736 participants (2,868 cancer survivors and 2,868 cancer-free participants) (Table 1). The mean age at baseline was 68.9 years (SD: 9.4) and 78.3% were NHW. The most common CVRF was hypertension (54.9%), followed by obesity (28.8%). The proportion of the sample with an incident cancer diagnosis over the follow-up was similar across CVRF categories (48.1% of those with no CVRFs, 50.4% of those with medium CVRFs, and 50.9% of those with high CVRFs; Table 1). NHB participants were more likely to have high CVRFs (23.7%) than no or medium CVRFs (9.5% and 15.3%, respectively) (Table 1). The distributions of individual CVRFs did not differ between cancer-free participants and cancer survivors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Study Population by Cancer Status and Cardiovascular Risk Factors (CVRFs), the US Health and Retirement Study, 1998–2018, n=5736

| N | Total | No CVRFs | Medium CVRFs | High CVRFs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5736 | Cancer | Cancer-free | Cancer | Cancer-free | Cancer | Cancer-free | |

| N=586 (48.1%) | N=632 (51.9%) | N=1718 (50.4%) | N=1691 (49.6%) | N=564 (50.9%) | N=545 (79.1%) | ||

|

| |||||||

| Age, mean (SD), years | 68.9 (9.4) | 68.1 (9.5) | 67.8 (9.4) | 69.3 (9.5) | 69.6 (9.5) | 68.7 (8.9) | 68.8 (8.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||

| Male | 2856 (49.8) | 281 (48.0) | 299 (47.3) | 881 (50.1) | 861 (50.1) | 286 (50.7) | 296 (54.3) |

| Female | 2880 (50.2) | 305 (52.1) | 333 (52.7) | 879 (49.1) | 857 (49.9) | 278 (48.3) | 249 (45.7) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||

| NHW | 4492 (78.3) | 524 (89.4) | 531 (84.0) | 1401 (79.6) | 1371 (79.8) | 401 (71.1) | 384 (70.5) |

| NHB | 909 (15.9) | 38 (6.5) | 60 (9.5) | 272 (15.5) | 262 (15.3) | 133 (23.6) | 129 (23.7) |

| Hispanic | 335 (5.8) | 24 (4.1) | 41 (6.5) | 87 (4.9) | 85 (5.0) | 30 (5.3) | 32 (5.9) |

| Education | |||||||

| Less than high school | 1321 (23.0) | 101 (17.2) | 102 (16.1) | 373 (21.2) | 360 (20.9) | 181 (32.1) | 164 (30.1) |

| High School | 1936 (33.8) | 157 (26.8) | 222 (35.1) | 609 (34.6) | 600 (34.9) | 183 (32.5) | 206 (37.8) |

| College | 1787 (31.2) | 213 (36.4) | 207 (32.8) | 583 (33.1) | 564 (32.8) | 156 (27.7) | 142 (26.1) |

| Graduate School | 692 (12.1) | 115 (20.0) | 101 (16.0) | 196 (11.1) | 197 (11.3) | 44 (7.8) | 33 (6.1) |

| Southern birthplace, n (%) | 1874 (32.7) | 171 (29.3) | 149 (23.7) | 568 (32.4) | 557 (32.6) | 231 (41.4) | 225 (41.4) |

| Alcohol Use, n (%) | |||||||

| None | 3658 (64.2) | 326 (55.6) | 359 (56.8) | 1109 (63.0) | 1076 (62.4) | 419 (74.3) | 419 (76.9) |

| Low Risk | 1903 (33.2) | 254 (43.3) | 263 (41.6) | 599 (34.0) | 593 (34.5) | 125 (22.2) | 110 (20.2) |

| Binge | 148 (2.6) | 6 (1.02) | 10 (1.6) | 52 (3.0) | 49 (2.9) | 20 (3.6) | 16 (2.9) |

| Individual CVRFs | |||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3228 (55.0) | - | - | 1064 (61.9) | 1048 (62.0) | 534 (94.7) | 505 (92.7) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1125 (19.2) | - | - | 185 (10.8) | 209 (12.4) | 349 (61.8) | 319 (58.5) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 1729 (29.4) | - | - | 451 (26.3) | 465 (27.5) | 371 (65.8) | 362 (66.4) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 493 (8.39) | - | - | 97 (5.7) | 94 (5.6) | 138 (24.5) | 161 (29.5) |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 3623 (62.3) | - | - | 314 (18.3) | 278 (16.4) | 145 (25.7) | 137 (25.1) |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 1453 (24.7) | - | - | 376 (21.9) | 356 (21.1) | 352 (62.4) | 334 (61.3) |

Note: CVRFs – Cardiovascular Risk Factors; SD – Standard Deviation; NHW – Non-Hispanic White; NHB – Non-Hispanic Black

Regression analyses using CVRF categories

Among cancer-free participants with no CVRFs, the mean memory score at age 65 was 0.10 SD units [95% CI: 0.01, 0.18; Table 2]. The mean memory score was lower for cancer-free participants with medium and high CVRFs than those with no CVRFs (difference in memory score for medium CVRFs: −0.09 SD units [95% CI: −0.15, −0.02] and difference in memory score for high CVRFs: −0.23 SD units [95% CI: −0.32, −0.15]; Table 2). This association was stronger among women (difference in memory score for women with high CVRFs: −0.29 SD units [95% CI: −0.42, −0.17]) than for men (difference in memory score for men with high CVRFs: −0.19 SD units [95% CI: −0.31, −0.07]; Table 2). In the study interview wave immediately prior to their diagnoses, cancer survivors had mean memory scores that were similar to those of their matched cancer-free counterparts, regardless of sex (difference for cancer survivors: −0.04 SD units [95% CI: −0.11, 0.03]; Table 2). The mean rate of memory decline over time for cancer-free participants with no CVRFs was −0.31 SD units/decade of age [95% CI: −0.35, −0.28], which was not statistically different from those with medium and high CVRFs (difference in memory slope for medium CVRFs: 0.005 SD units/decade of age [95% CI: −0.04, 0.05] and difference in memory slope for high CVRFs: 0.01 SD units/decade of age [95% CI: −0.06, 0.08]; Table 2). Cancer survivors with medium CVRFs had slightly slower rates of memory decline over time relative to their cancer-free counterparts (difference in memory slope for medium CVRFs: 0.04 SD units/decade of age [95% CI: 0.001, 0.08]; Table 2) but this association did not differ by sex (Table 3).

Table 2.

Estimated Effect of Incident Cancer and Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Memory Function and Rate of Change, Overall and By Sex, the US Health and Retirement Study, 1998–2018, n=5736

| Overall (n=5736) | Males (n=2856) | Females (n=2880) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Memory function (SD units) and memory change (SD units/decade) | |||||||||

| Participants with no cancer during follow-up | |||||||||

| Memory function at age 65 | 0.10 | 0.01, 0.18 | 0.022 | −0.56 | −0.67, −0.45 | <0.001 | −0.14 | −0.25, −0.04 | 0.008 |

| Memory slope with linear age | −0.31 | −0.35, −0.28 | <0.001 | −0.30 | −0.36, −0.24 | <0.001 | −0.32 | −0.37, −0.27 | <0.001 |

| Memory slope with quadratic age | −0.11 | −0.12, −0.09 | <0.001 | −0.10 | −0.12, −0.08 | <0.001 | −0.12 | −0.13, −0.09 | <0.001 |

| Medium and high CVRFs (vs. no CVRFs) | |||||||||

| Difference in memory function for participants with medium CVRFs | −0.09 | −0.15, −0.02 | 0.011 | −0.08 | −0.17, 0.02 | 0.125 | −0.13 | −0.22, −0.03 | 0.008 |

| Difference in memory function for participants with high CVRFs | −0.23 | −0.32, −0.15 | <0.001 | −0.19 | −0.31, −0.07 | 0.002 | −0.29 | −0.42, −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Difference in memory slope for participants with medium CVRFs | 0.005 | −0.04, 0.05 | 0.834 | 0.02 | −0.05, 0.08 | 0.590 | 0.00004 | −0.06, 0.06 | 0.999 |

| Difference in memory slope for participants with high CVRFs | 0.01 | −0.06, 0.08 | 0.754 | <0.001 | −0.10, 0.09 | 1.00 | 0.02 | −0.08, 0.11 | 0.716 |

| Participants with an incident cancer diagnosis during follow-up | |||||||||

| Memory function at age 65a | −0.04 | −0.11, 0.03 | 0.298 | 0.01 | −0.09, 0.11 | 0.841 | −0.06 | −0.16, 0.05 | 0.273 |

| Medium and high CVRFs (vs. no CVRFs) | |||||||||

| Difference in memory function for cancer survivors with medium CVRFsa | 0.01 | −0.08, 0.10 | 0.812 | −0.01 | −0.14, 0.12 | 0.892 | 0.03 | −0.10, 0.16 | 0.661 |

| Difference in memory function for cancer survivors with high CVRFsa | 0.08 | −0.04, 0.20 | 0.174 | 0.02 | −0.15, 0.18 | 0.843 | 0.11 | −0.06, 0.28 | 0.207 |

| Difference in post-cancer memory slope for cancer survivors with medium CVRFsa | 0.04 | 0.001, 0.08 | 0.043 | 0.03 | −0.03, 0.09 | 0.353 | 0.06 | −0.002, 0.11 | 0.059 |

| Difference in post-cancer memory slope for cancer survivors with high CVRFsa | 0.05 | −0.03, 0.14 | 0.203 | 0.10 | −0.02, 0.22 | 0.101 | 0.03 | −0.09, 0.14 | 0.624 |

Compared to participants with no cancer over the follow-up, as the reference group

Note: Adjusted for age, age2, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, southern birthplace, self-rated childhood health, educational attainment, and alcohol use. SD – Standard Deviation; CVRFs – Cardiovascular Risk Factors; 95% CI – 95% Confidence Interval

Overall model: Memoryij = β0 + β1 agej + β2 age2j + β3 Medium CVRFs + β4 High CVRFs + β5 Medium CVRFs*agej + β6 High CVRFs*agej + β7 cancer_diagnosis + β8 Medium CVRFs*cancer_diagnosis + β9 High CVRFs*cancer_diagnosis + β10 Medium CVRFs*cancer_diagnosis*agej + β11 High CVRFs*cancer_diagnosis*agej + Σβk covariates

Table 3.

Estimated Effect of Incident Cancer and Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Memory by Race/Ethnicity, the US Health and Retirement, 1998 – 2018, n = 5,736

| NHW (n=4492) | NHB (n=909) | Hispanic (n=335) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βa | 95% CI | p-value | βa | 95% CI | p-value | βa | 95% CI | p-value | |

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Memory function (SD units) and memory change (SD units/year) | |||||||||

| Participants with no cancer during follow-up and low baseline CVRFs | |||||||||

| Memory function at age 65 | −0.06 | −0.13, 0.02 | 0.162 | −0.70 | −0.94, −0.47 | <0.001 | −0.48 | −0.74, −0.22 | <0.001 |

| Memory slope with linear age | −0.31 | −0.35, −0.28 | <0.001 | −0.32 | −0.44, −0.20 | <0.001 | −0.37 | −0.52. −0.22 | <0.001 |

| Memory slope with quadratic age | −0.11 | −0.13, −0.09 | <0.001 | −0.08 | −0.11, −0.05 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −0.12, −0.01 | 0.031 |

| Medium and high CVRFs (vs. no CVRFs) | |||||||||

| Difference in memory function for participants with medium CVRFs | −0.10 | −0.17, −0.03 | 0.006 | 0.11 | −0.09, 0.31 | 0.296 | −0.04 | −0.28, 0.21 | 0.767 |

| Difference in memory function for participants with high CVRFs | −0.24 | −0.32, −0.15 | <0.001 | −0.05 | −0.28, 0.17 | 0.639 | −0.26 | −0.60, 0.07 | 0.126 |

| Difference in memory slope for participants with medium CVRFs | 0.004 | −0.05, 0.05 | 0.885 | 0.01 | −0.12, 0.14 | 0.871 | −0.04 | −0.21, 0.13 | 0.637 |

| Difference in memory slope for participants with high CVRFs | −0.03 | −0.11, 0.05 | 0.438 | 0.06 | −0.10, 0.21 | 0.488 | 0.20 | −0.07, 0.48 | 0.154 |

| Participants with an incident cancer diagnosis during follow-up | |||||||||

| Difference in memory function at age 65b | −0.06 | −0.14, 0.02 | 0.120 | 0.05 | −0.22, 0.34 | 0.719 | 0.11 | −0.19, 0.41 | 0.464 |

| Medium and high CVRFs (vs. no CVRFs) | |||||||||

| Difference in memory function for cancer survivors with medium CVRFsb | 0.04 | −0.05, 0.14 | 0.385 | −0.11 | −0.41, 0.19 | 0.486 | −0.16 | −0.52, 0.19 | 0.368 |

| Difference in memory function for cancer survivors with high CVRFsb | 0.11 | −0.03, 0.25 | 0.385 | 0.01 | −0.32, 0.34 | 0.957 | −0.24 | −0.72, 0.24 | 0.335 |

| Difference in post-cancer memory slope for cancer survivors with medium CVRFsb | 0.03 | −0.02, 0.07 | 0.264 | 0.07 | −0.03, 0.17 | 0.162 | 0.16 | −0.001, 0.32 | 0.052 |

| Difference in post-cancer memory slope for cancer survivors with high CVRFsb | 0.08 | −0.02, 0.17 | 0.122 | 0.01 | −0.16, 0.18 | 0.893 | −0.03 | −0.39, 0.33 | 0.871 |

Estimates are from models stratified by race/ethnicity, and adjusted for age, age2, sex/gender, southern US birthplace, educational attainment, and alcohol use.

Compared to the corresponding estimate for participants with no cancer over the follow-up.

Note: NHW – Non-Hispanic White; NHB – Non-Hispanic Black; 95% CI – 95% Confidence Interval; CVRFs – Cardiovascular Risk Factors; SD – Standard deviation

When stratified by race/ethnicity, NHB and Hispanic cancer-free participants with no CVRFs had lower memory scores at age 65 than NHW cancer-free participants with no CVRFs (−0.70 SD units [95% CI: −0.94, −0.47] for NHB participants; −0.48 SD units [95% CI: −0.74, −0.22] for Hispanic participants; and −0.06 SD units [95% CI: −0.13, 0.02] for NHW participants; Table 3). A similar racial/ethnic difference in memory scores was observed among cancer survivors (Table 3). The mean memory scores for NHW cancer-free participants with medium and high CVRFs were lower than those of NHW cancer-free participants with no CVRFs (−0.10 SD units [95% CI: −0.17, −0.03] and −0.24 SD units [95% CI: −0.32, −0.15], respectively; Table 3). There was no difference in mean memory or memory decline with increasing CVRFs for NHB and Hispanic cancer-free participants or cancer survivors (Table 3).

Regression analyses with continuous CVRF score

Due to small sample sizes in the CVRF categories, we conducted a sensitivity analysis repeating the overall and race/ethnicity stratified analyses using a continuous variable for the number of CVRFs (range: 0–6). Among cancer-free participants, each additional CVRF was significantly associated with lower memory scores at baseline (−0.07 SD units [95% CI: −0.09, −0.05]; Supplemental Table 1), but not with the rate of memory decline over time (0.001 SD units/decade of aging [95% CI: −0.02, 0.02]; Supplemental Table 1). Among cancer survivors, the association between CVRFs and baseline memory was like that observed among their matched cancer-free counterparts; however, the increasing number of CVRFs among cancer survivors was associated with slower rates of memory decline over time (0.02 SD units/decade of aging [95% CI: 0.003, 0.04]; Supplemental Table 1).

By race/ethnicity, each additional CVRF was associated with lower memory scores at baseline for NHW, but not NHB or Hispanic cancer-free participants (−0.07 SD units [95% CI: −0.09, −0.04] for NHW participants; −0.05 SD units [95% CI: −0.10, 0.01] for NHB participants; and −0.06 SD units [95% CI: −0.14, 0.02] for Hispanic participants; Supplemental Table 2). Within each racial/ethnic group, cancer survivors had similar mean memory scores at baseline and rate of memory decline over time as their matched cancer-free, according to increasing number of CVRFs (Supplemental Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses: Regression analyses by individual CVRFs

In an exploratory analysis, we estimated the association between each individual CVRFs and memory aging, separately. Cancer-free participants with baseline hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke had lower memory scores at baseline relative to those who did not have these comorbidities (difference for hypertension: −0.08 SD units [95% CI: −0.14, −0.03]; difference for diabetes: −0.14 SD units [95% CI: −0.22, −0.06]; differences for heart disease; −0.14 SD units [95% CI: −0.21, −0.06]; and difference for stroke: −0.29 SD units [95% CI: −0.41, −0.17]; Supplemental Table 3). Cancer survivors with baseline hypertension had similar mean memory at baseline relative to cancer-free participants but had slightly slower rates of memory decline over time (difference in memory slope for cancer survivors with hypertension: 0.05 SD units/decade of age [95% CI: 0.005, 0.10]; Supplemental Table 3). We did not observe any other differences in mean memory function or rate of memory decline for cancer survivors relative to cancer-free participants, according to individual CVRFs (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

In this population-based longitudinal study, we investigated the role of CVRFs in the memory aging of NHW, NHB, and Hispanic older cancer survivors, using matched cancer-free older adults as a comparison to isolate differences over and above chronological aging alone. We found that higher numbers of CVRFs were associated with worse memory at baseline for both cancer survivors and their cancer-free counterparts which was stronger among women than men. We observed that NHB and Hispanic older adults had worse memory at baseline relative to NHW older adults, and the magnitude of this disparity was similar between cancer survivors and their cancer-free counterparts. CVRFs were not associated with rate of memory decline over time for older cancer survivors or cancer-free adults when stratified by race/ethnicity or sex/gender. Finally, we found that baseline hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke were independently associated with worse memory at baseline compared to those without these comorbidities, but these associations did not differ by cancer status. The similarity of our findings between older cancer survivors and cancer-free adults suggests that there is a similar mechanism through which CVRFs affect memory aging, regardless of cancer status.

Comparison with other literature

Our finding that CVRFs are associated with worse later-life memory function among both older cancer survivors and cancer-free adults is consistent with previous research demonstrating this association among the cancer-free general population [5, 8, 9, 27, 28]. CVRFs including smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes have individually been associated with lower cognitive function and faster cognitive decline among cancer-free individuals [5,8,9,31]. We found that the association between CVRFs and memory aging did not differ by cancer status. Few studies have investigated this association in older cancer survivors compared to cancer-free individuals. Von Ah and colleagues found that the presence of pre-existing cardiovascular disease was associated with poorer performance on tests of immediate memory, and attention and working memory among a cohort of women with breast cancer, consistent with our findings [11]. Our study builds upon their findings by extending its results across several cancer types in a population-based sample with comparison to matched cancer-free individuals. Our results suggest that, at the population level, the mechanism linking CVRFs with memory aging outcomes may be similar regardless of a cancer diagnosis. Furthermore, we found that the association of having high CVRFs and lower baseline memory was stronger among women than for men, regardless of cancer status. This finding requires more investigation but may be related to differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive impairment among men and women [32].

Consistent with previous research on racial/ethnic disparities in memory aging outcomes, we found that NHB and Hispanic participants had lower memory function at baseline than NHW participants, across all CVRF categories [33]. The magnitudes of these racial differences were largely similar between older cancer survivors and their cancer-free counterparts. Racial disparities in memory aging in the United States are often attributed to historical and contemporary forms of racism including residential segregation, unequal access to quality education and employment, and unequal access to health care services [34–38]. In our cohort, approximately half of Hispanic participants and nearly forty percent of NHB participants had less than a high school education, compared to nearly two in five NHW participants. Additionally, NHB cancer-free participants and cancer survivors had higher prevalence of CVRFs, including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity than NHW cancer-free participants and cancer survivors. Our finding of racial/ethnic disparities in memory aging among older cancer survivors likely reflects multifactorial and structural factors that reflect disparities in access to health care, socioeconomic disparities, and cancer diagnosis and treatment disparities, among others. Future studies should further investigate the role of these social disparities to better disentangle this complex relationship.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has limitations. It is possible that we were underpowered to detect significant differences between racial/ethnic groups due to small sample sizes within NHB and Hispanic groups. We measured CVRFs at baseline, defined as the study interview wave prior to a reported cancer diagnosis, although CVRFs can be time-varying, and additional longitudinal measures of changes over time in CVRFs could result in stronger associations with memory aging than measuring these risk factors at a single time point. Future studies could utilize methods that account for the time-varying structure such as marginal structural models. Further, for the purpose of this study, we did not examine medication use which could affect estimates among participants with medication-controlled comorbidities. We were unable to examine differences in associations across different cancer types as this is not publicly available data or treatment modalities. There could be bias introduced due to study attrition as many cancer survivors died soon after diagnosis. Older cancer survivors with more CVRFs prior to their diagnosis may have had lower cognitive scores at baseline compared to those with fewer CVRFs, and these individuals may not have lived as long after a cancer diagnosis. As with many research studies of older cancer survivors, our sample may thus represent a selected healthier subset of all older adults diagnosed with cancer, and our results may in turn underestimate the true associations under study.

A strength of this study is its large, population-based sample of middle-aged and older US adults over a long follow-up period. The use of the HRS provided us with a population-based sampling frame, which avoids selection bias that may be present in clinic-based studies of cancer survivors [10]. While we were unable to restrict our sample to specific cancer types due to the lack of availability of cancer type and small sample sizes, a strength of our results is that they can be viewed as the associations across all cancer types that occur in the US population aged 50 and over. We matched older cancer survivors to cancer-free older adults based on age, sex/, and year, which allowed us to compare how the experience of a cancer diagnosis after age 50 might modify the effect of CVRFs on memory function and rate of decline. Additionally, we had data on memory and CVRFs prior to a cancer diagnosis, which allowed us to circumvent potential recall bias that may occur in studies of cancer survivorship that recruit and interview participants following their diagnosis [39].

Conclusion

Understanding the cognitive health of older cancer survivors is a critical need as this population is rapidly growing. In this population-based study of the memory aging of older cancer survivors, we found that pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors were associated with worse memory function among older cancer survivors and cancer-free older adults. These results indicate that similar mechanisms may link vascular health with brain health in older adults with and without cancer. In addition, we observed racial/ethnic disparities in later-life memory amongst both older cancer survivors and cancer-free older adults.

A key implication of this work is that the identification of pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors is an important clinical action during the diagnostic phase. Understanding baseline risk factors can help clinicians work with older cancer patients to reduce modifiable risk factors (e.g., tobacco) and manage comorbid conditions (e.g., through hypertension control), to help improve their memory function as they age. A second implication is the public health importance of identifying and address underlying non-clinical structural barriers to optimal memory function during aging across cancer survivors from diverse racial and ethnic groups in the United States.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging Pathway to Independence Award (K99 AG076532) to Ashly C. Westrick

Footnotes

Statements & Declarations:

Competing Interests: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.”

References

- 1.Ahles TA, Root JC, Ryan EL. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: an update on the state of the science. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3675–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahles TA, Root JC. Cognitive Effects of Cancer and Cancer Treatments . Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:425–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janelsins MC, Kohli S, Mohile SG, Usuki K, Ahles TA, Morrow GR. An update on cancer- and chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction: current status. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westrick AC, Langa KM, Eastman M, Ospina-Romero M, Mullins MA, Kobayashi LC. Functional aging trajectories of older cancer survivors: a latent growth analysis of the US Health and Retirement Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;17:1499–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Hoang T, Matthews K, Golden SH, Al Hazzouri AZ. Cardiovascular Risk Factors Across the Life Course and Cognitive Decline: A Pooled Cohort Study. Neurology. 2021;96:e2212–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olaya B, Moneta MV, Bobak M, Haro JM, Demakakos P. Cardiovascular risk factors and memory decline in middle-aged and older adults: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stabellini N, Cullen J, Cao L, Shanahan J, Hamerschlak N, Waite K, et al. Racial disparities in breast cancer treatment patterns and treatment related adverse events. Sci Rep. 2023;13:1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaffe K, Bahorik AL, Hoang TD, Forrester S, Jacobs DR, Lewis CE, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and accelerated cognitive decline in midlife: The CARDIA Study. Neurology. 2020;95:e839–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu C, Fratiglioni L. A major role for cardiovascular burden in age-related cognitive decline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenneman CG, Sawyer DB. Cardio-Oncology: An Update on Cardiotoxicity of Cancer-Related Treatment. Circ Res. 2016;118:1008–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Von Ah D, Crouch A, Arthur E, Yang Y, Nolan T. Association Between Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Dysfunction in Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2022;46:e122–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Mortality, Incidence, and Survival in the United States, 1950–2014: Over Six Decades of Changing Patterns and Widening Inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:2819372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brothers RM, Fadel PJ, Keller DM. Racial disparities in cardiovascular disease risk: mechanisms of vascular dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2019;317:H777–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weuve J, Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Rajan KB, Beck T, Aggarwal NT, et al. Cognitive Aging in Black and White Americans: Cognition, Cognitive Decline, and Incidence of Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Epidemiology. 2018;29:151–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franco-Rocha OY, Lewis KA, Longoria KD, De La Torre Schutz A, Wright ML, Kesler SR. Cancer-related cognitive impairment in racial and ethnic minority groups: a scoping review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:12561–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastman MR, Ospina-Romero M, Westrick AC, Kler JS, Glymour MM, Abdiwahab E, et al. Does a Cancer Diagnosis in Mid-to-Later Life Modify Racial Disparities in Memory Aging? Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2022;36:140–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell CN, Thorpe RJ, Bowie JV, LaVeist TA. Race disparities in cardiovascular disease risk factors within socioeconomic status strata. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:147–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kibria GMA, Crispen R, Chowdhury MAB, Rao N, Stennett C. Disparities in absolute cardiovascular risk, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, and other risk factors by income within racial/ethnic groups among middle-aged and older US people. J Hum Hypertens. 2023;37:480–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He J, Zhu Z, Bundy JD, Dorans KS, Chen J, Hamm LL. Trends in Cardiovascular Risk Factors in US Adults by Race and Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status, 1999–2018. JAMA. 2021;326:1286–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adhikary D, Barman S, Ranjan R, Stone H. A Systematic Review of Major Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Growing Global Health Concern. Cureus. 2022. Oct 10;14(10):e30119. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB & Rowland JH Anticipating the ‘Silver Tsunami’: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25, 1029–1036 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco-Rocha OY et al. Cancer-related cognitive impairment in racial and ethnic minority groups: a scoping review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol (2023) doi: 10.1007/s00432-023-05088-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JWR, Weir DR. Cohort Profile: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCammon PRJ et al. Health and Retirement Study Imputation of Cognitive Functioning Measures: 1992–2018 (Version 7.0). (2022). :576–85. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song R, Xu H, Dintica CS, Pan K-Y, Qi X, Buchman AS, et al. Associations Between Cardiovascular Risk, Structural Brain Changes, and Cognitive Decline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2525–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajjar I, Yang F, Sorond F, Jones RN, Milberg W, Cupples LA, et al. A novel aging phenotype of slow gait, impaired executive function, and depressive symptoms: relationship to blood pressure and other cardiovascular risks. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:994–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irimata KE, Dugger BN, Wilson JR. Impact of the Presence of Select Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Cognitive Changes among Dementia Subtypes. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018;15:1032–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vintimilla R, Balasubramanian K, Hall J, Johnson L, O’Bryant S. Cardiovascular Risk Factors, Cognitive Dysfunction, and Mild Cognitive Impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2020;10:154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weuve J, Proust-Lima C, Power MC, Gross AL, Hofer SM, Thiébaut R, et al. Guidelines for reporting methodological challenges and evaluating potential bias in dementia research. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1098–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamar M, Lerner AJ, James BD, Yu L, Glover CM, Wilson RS, et al. Relationship of Early-Life Residence and Educational Experience to Level and Change in Cognitive Functioning: Results of the Minority Aging Research Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:e81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitmer RA, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Volgman AS, Bairey Merz CN, Aggarwal NT, Bittner V, Bunch TJ, Gorelick PB, Maki P, Patel HN, Poppas A, Ruskin J, Russo AM, Waldstein SR, Wenger NK, Yaffe K, Pepine CJ. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Impairment: Another Health Disparity for Women? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019. Oct;8(19):e013154. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adkins-Jackson PB, George KM, Besser LM, Hyun J, Lamar M, Hill-Jarrett TG, et al. The structural and social determinants of Alzheimer’s disease related dementias. Alzheimers Dement. 2023;19:3171–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahodne LB. Biopsychosocial pathways in dementia inequalities: introduction to the Michigan Cognitive Aging Project. Am Psychol. 2021;76:1470–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avila JF, Rentería MA, Jones RN, Vonk JMJ, Turney I, Sol K, et al. Education differentially contributes to cognitive reserve across racial/ethnic groups. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:70–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vable AM, Cohen AK, Leonard SA, Glymour MM, Duarte CDP, Yen IH. Do the health benefits of education vary by sociodemographic subgroup? Differential returns to education and implications for health inequities. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:759–766.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kovalchik SA, Slaughter ME, Miles J, Friedman EM, Shih RA. Neighbourhood racial/ethnic composition and segregation and trajectories of cognitive decline among US older adults. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69:978–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, Hayward MD, Yu Y-L. Life Course Pathways to Racial Disparities in Cognitive Impairment among Older Americans. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57:184–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi LC, Westrick AC, Doshi A, Ellis KR, Jones CR, LaPensee E, et al. New directions in cancer and aging: State of the science and recommendations to improve the quality of evidence on the intersection of aging with cancer control. Cancer. 2022;128:1730–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.