Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a global autoimmune disease that requires long-term management. Ambulatory monitoring and treatment of RA favors remission and rehabilitation. Here, we developed a wearable reconfigurable integrated smart device (ISD) for real-time inflammatory monitoring and synergistic therapy of RA. The device establishes an electrical-coupling and substance delivery interfaces with the skin through template-free conductive polymer microneedles that exhibit high capacitance, low impedance, and appropriate mechanical properties. The reconfigurable electronics drive the microneedle-skin interfaces to monitor tissue impedance and on-demand drug delivery. Studies in vitro demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of electrical stimulation on macrophages and revealed the molecular mechanism. In a rodent model, impedance sensing was validated to hint inflammation condition and facilitate diagnosis through machine learning model. The outcome of subsequent synergistic therapy showed notable relief of symptoms, elimination of synovial inflammation, and avoidance of bone destruction.

An integral wearable system uses reconfigurable circuit and conductive microneedles for rheumatoid arthritis management.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) has become a major cause of disability affecting 24.5 million patients and 1.2 million new cases worldwide (1, 2). This chronic autoimmune disease primarily manifests with symmetrical stiffness, joint swelling, and tenderness caused by synovitis that, if untreated, can cause irreversible damage to cartilage and bone (3). Precise and personalized management is critical for patients to improve clinical symptoms, delay progression, and reduce disability (4, 5). Common treatments include disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications, physical therapy, and surgery (6–9). Methotrexate (MTX) is the most commonly prescribed antirheumatic drug, but there are still many limitations: (i) More than 40% of patients respond suboptimally to monotherapy, requiring adjunctive therapies (3, 6); (ii) Systemic side effects are common and inevitable, particularly on the bone marrow, liver, and gastrointestinal function (10–13). Low and frequent doses of MTX with long-term monitoring may reduce side effects and improve outcomes (14–17); (iii) long-term disease monitoring and treatment is a huge burden for more than 80% of patients, may lead to negative compliance, and affect the treatment outcome (18, 19). Therefore, the search for new monitoring and management methods for RA has become a meaningful target of research (see more detailed explanation in the Supplementary Materials).

Wearable device with disease activity monitoring and localized, controllable drug delivery, is a promising approach to meet the needs of clinical management in RA patients. Besides, to improve the outcome of treatment, some adjunctive therapies are also required. Electrotherapy is a promising treatment for RA to relieve pain and reduce inflammation (20–22), but poorly understood mechanisms of electrical stimulation and cumbersome administration limit its widespread clinical use (23). However, there is still a lack of highly integrated wearable solutions for RA. To solve the above disadvantages, a reasonable module-level circuit structure is essential for functional implementation, high integration, and lightweight. We thus attempted to design a versatile and lightweight architecture to meet the requirements of RA monitoring and treatment.

To realize real-time monitoring and efficient synergistic therapy of RA through a wearable system, a substance with specific mechanical, chemical, and electrical properties is expected to interface with the tissue. This material requires appropriate mechanical strength, large volume, and volumetric capacitance for drug delivery, enabling drug storage and on-demand release (24, 25). It should provide high electronic conductivity for applications involving impedance sensing and electrical stimulation to ensure electrical coupling and high fidelity (26, 27).

Here, we developed a reconfigurable integrated smart device (ISD) using reconfigurable electronics and conductive polymer-based microneedles for real-time inflammation monitoring as well as controlled synergistic therapeutic of RA. The reconfigurable electronics (Fig. 1A) incorporates a digital module and an analog front-end (AFE) module that enabled dynamic reprogramming of the circuit. Meanwhile, a microneedle array based on template-free pure conducting polymer hydrogel (Fig. 1B) was constructed for high volume, expected mechanical nature, ideal electrochemical properties, and biocompatibility. The device was designed to achieve (i) reconfigurable circuit architecture and module-level integration; (ii) impedance-based inflammation monitoring and machine learning-assisted inflammatory prediction; (iii) precise control of the transdermal delivery of MTX; and (iv) synergistic therapy with electrical stimulation (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. The wearable system with reconfigurable electronics and conducting polymer-based microneedles for real-time monitoring and synergistic treatment of RA.

(A) Treatment protocols sent to the system are processed by the digital module and converted into hardware configuration and drive signal of the AFE. (B) Mechanism of drug and electrical stimulation synergistic therapy using ISD. (C) Rodent models are used to collect clinical parameters to train and validate machine learning models and to evaluate the outcomes of synergistic treatments. GPIO, general-purpose input/output; CPU, central processing unit.

RESULTS

System overview

Figure 2A presents the structure of the ISD device described above, which measures 49 mm by 15 mm by 18 mm. The system consists of two microneedle arrays (12 mm by 12 mm by 2 mm), mechanical structure (encapsulation and holders for microneedle arrays), and electronics. The electronics include an AFE module, digital module, and power management components (Fig. 2B). Two microneedle arrays are mounted on the device and puncture into the skin when worn. The device can be comfortably worn on the wrist, ankle, or finger and controlled by a mobile application (Fig. 2, C and D).

Fig. 2. Overview of the ISD and the structure of the reconfigurable electronics.

(A) Schematic diagram of the ISD. (B) Exploded layer view of the designed system including AFE, digital module, LCD screen, microneedle, mechanical supports, solar cell, etc. (C) Photographs of the bottom and top view of the ISD. (D) ISD was worn on the wrist, ankle and finger comfortably and accessed through a mobile application. (E) Block diagram of the reconfigurable integral electronics. The left panel shows the function blocks of the AFE module, including two symmetrical programmable signal channels. The right panel shows the architecture of the digital module, involving power management, system-on-chip, and wireless transmission on the digital module. (F) Photographs of the top and bottom of the assembled printed circuit board of the digital module and AFE module. Scale bar, 5 mm. Calibration curve for ADC values at defined (G) potentials and (H) currents. (I) Calibration curve of DAC. RE, reference electrode; MNs, microneedles; TIA, transimpedance amplifier; LPF, low-pass filter; a.u., arbitrary units; RAM, random access memory; FPC, flexible printed cable; I/O, input/output.

Integral reconfigurable electronics

The architecture diagram of the electronics is shown in Fig. 2E. In the AFE module, two symmetrical signal channels are designed to provide two equivalent ports, each connected to a microneedle electrode and sharing a common reference electrode. Each signal channel contains a differential amplifier, a transimpedance amplifier (TIA), and a noninverting amplifier connected to a digital-to-analog converter (DAC). The differential amplifier is used to measure the potential difference between the reference electrode and the microneedle. TIA converts the current through the microneedle into a potential signal. The multiplexer in each signal channel is configured by the logic signals of the digital module, thus switching between four modes: digital-to-analog (DAC), grounding (GND), reference signal (REF), and current signal (CUR). In DAC mode, the channel outputs the drive signal. In GND mode, the microneedle is connected to the internal potential ground. In REF mode, the microneedle is used as a reference signal electrode. The CUR mode is applied to record the current through the microneedle. The mode configuration of the two channels on the AFE enables this device to perform transdermal drug delivery, electrical stimulation, impedance sensing, etc. (fig. S1).

In the digital module, the microcontroller changes the mode of the AFE channels. The signals from the microneedles interface are routed and digitized by the analog-digital converter (ADC), and similarly, the signals analogized by DAC change the potential of microneedles. Meanwhile, human-computer interaction and communication features are also integrated, including a liquid crystal display (LCD) screen, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, etc. A power management system supplied the +3.3-V rail for the digital circuit and ±5-V rail for the analog circuit. It also harvested energy from two solar cells and stored power in a Li-polymer battery for self-powering. The electronics are assembled on two printed circuit boards (Fig. 2F). The differential amplifier, TIA, and DAC in the integral electronics were calibrated (Fig. 2, G to I). The linearities of the calibrations were 0.9957, 0.9631, and 0.9994, respectively. To verify the reconfigurable features of the AFE, the circuit timing and waveform curves were recorded (fig. S2). The endurance of ISD was also evaluated. ISD was able to sustain electrical stimulation for up to 40 min, which is sufficient for one synergistic treatment (fig. S3). In standby mode, ISD can support 15 hours of endurance (fig. S4). Temperature rises during operation are also measured (fig. S5).

Fabrication and Characteristics of template-free conducting polymer

To establish an ideal electro-coupled, electro-responsive drug delivery interface with the skin, a substance with specific intrinsic electrical conductivity, charge storage/injection characteristics, high drug loading capacity and appropriate mechanical properties is essential. Conducting polymer is used to fabricate the conductive microneedle. However, the inherent poor solubility of conducting polymer chain and the strong inter- and intrachain interactions inhibits the favorable interaction between the polymer chain and solvent (28, 29). A strategy for incorporating functional surfactant anions to improve solubility and provide active anchors for crosslinking was developed (Fig. 3A). The doping of the polymer chain was achieved by the addition of the counter ion 3-hydroxypropane-1-sulfonate (confirmed by 1H NMR; fig. S6) in the polymerization reaction of polypyrrole (PPy) to yield the soluble PPy (PPy-OH). The PPy-OH had an average molecular weight of 127,633 g mol−1 and a polydispersity index of 2.67 (fig. S7).

Fig. 3. Conducting polymer-based microneedle as a transdermal coupling interface.

(A) Schematic diagram of the synthesis of PPy-mesh and the fabrication process of the microneedle. (B) Close-up image of the microneedles. Scale bar, 800 μm. Insert: Macrophotography of PPy-mesh microneedles. Scale bar, 3 mm. (C) SEM image of a single needle. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) A magnified SEM image showed the microstructure of PPy-mesh. Scale bar, 1 μm. (E) Representative image of porcine skin after treatment of the rhodamine B–loaded PPy-mesh. Scale bar, 2 mm. (F) Reconstructed 3D fluorescent images. Scale bar, 200 μm. (G) Stress-strain curve of the PPy-mesh microneedle. (H) Cyclic voltammetry of the conductive microneedle and Pt electrode. (I) Bode plot of the PPy-mesh microneedle and Pt electrode. Line denotes complex impedance plots, and dashed line denotes phase plots. (J) Nyquist plot and equivalent circuit, where Re represents the electronic resistance, Ri represents the ionic resistance, Rc represents the total ohmic resistance of the electrochemical cell assembly, Gdl represents the constant phase element of electric double-layer capacitance, and Gg is the constant phase element of the geometric capacitance. (K) Representative AFM topography image of PPy-mesh and line-cut profile of the surface. (L) Peakforce QNM images of the same region of the surface. DMT (Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov) modulus, adhesion, and deformation map of PPy-mesh obtained in air. (M) Current image obtained by tunneling AFM. Scale bars, 500 nm [(K) to (M)]. PEGDA, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate; TPO-L, photoinitiator ethyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phenylphosphinate; MAA, methacrylic anhydride; DAC, digital-to-analog mode; GND, grounding mode; REF, reference signal mode; CUR, current signal mode.

The prepolymer solution is prepared by incorporating crosslinker poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) and photoinitiator into methacryloyl group substituted PPy-OH (PPy-acrylate) solution. The mixture forms a porous gel (PPy-mesh) after photocuring for the fabrication of microneedle arrays. The optic photographs (Fig. 3B) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images show the morphology of the microneedle array and its network structure (Fig. 3, C and D). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirmed the elements and their valence states (figs. S8 to S10). The chemical structure of PPy, PPy-OH, and PPy-mesh was further verified by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The spectra (fig. S11) showed that bands located at 1284 and 1548 cm−1 are assigned to N─C stretching band and C═C in-ring stretching, respectively. Bands at 1020 cm−1 in PPy-OH and PPy-mesh are assigned to vibrations of sulfone groups. A band at 1630 cm−1 in PPy-mesh is assigned to O═C stretching (30).

To investigate the effect of doping on the polymer backbone, x-ray diffraction was used to analyze the microstructures of PPy, PPy-OH, and PPy-mesh (fig. S12). The peak in PPy-OH associated with the interplanar distance of the backbone is shifted to 23.4°, indicating that the doping increases the interplanar spacing, and avoids the tight packing of PPy chains.

Conducting polymer-based microneedle as bioelectronic interface

To demonstrate the epidermal penetrability of the conductive microneedle, fluorescent dye (rhodamine B)–loaded microneedles were inserted into porcine skin (Fig. 3E). Confocal laser scanning microscope showed that microneedles can penetrate the stratum corneum so that the fluorescent dye diffused in the deep tissue and leaves cone-shape zones of the fluorescence signal (Fig. 3F). The mechanical test showed that the single-needle failure stress of the array is about 1.5 N (Fig. 3G). The compressive modulus obtained from the stress-strain curve is about 18.75 MPa. The swelling ratio of the PPy-mesh microneedles is 146.81% (fig. S13), suggesting that PPy-mesh has a relatively high crosslinking density. To determine the drug loading capacity, drug release profiles were constructed by plotting the amount of rhodamine B and MTX released from the PPy-mesh microneedle over time (fig. S14). The microneedles exhibit a high drug loading capacity (1.12 ± 0.10 mg and 0.78 ± 0.0035 mg per patch, respectively).

The conductivity of PPy-mesh measured by the dual-probe method is approximately 23.1 S cm−1, which is several orders of magnitude higher than most ionic or hybrid conductive hydrogel without compromising mechanical strength (31). Cyclic voltammetry presented broad and stable anodic and cathodic peaks (Fig. 3H) from −0.4 to 0.9 V. Compared to Pt electrodes, PPy-mesh microneedles have a high capacity for storing charge, which is favorable for drug delivery and electrical stimulation. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy was performed to analyze the impedance feature in the bioelectric frequency range (0.1 to 105 Hz). The impedance of PPy-mesh at the frequency range is stable. At the frequency of 1 Hz, the impedance of PPy-mesh is 493.4 ohm, which is lower than that of the Pt electrode (1034.1 ohm). The phase delay caused by PPy-mesh is also unremarkable (Fig. 3I). At the frequency of 105 Hz, PPy-mesh shows low charge transfer resistance, which is beneficial for electrical stimulation and sensing (32). The Nyquist plot (Fig. 3J) reveals ionic and electronic impedance in the PPy-mesh. The equivalent circuit model (Rc = 173.7 ohm, Gg = 0.3101 × 10−3 F sn−1, ng = 0.4281, Re = 1487 ohm, Gdl = 2.69 × 10−3 F sn−1, ndl = 0.8734, and Ri = 541.2 ohm) confirm the comparatively low ionic and electronic impedance and high interfacial capacitance (33, 34).

The mechanical and electrical features of the PPy-mesh originate from the nanostructure. The topography, mechanical properties, and conductivity mapping of PPy-mesh were evaluated by an atomic force microscope. The arithmetic roughness average of the surface calculated by topography (Fig. 3K) is 357 ± 48 nm. The SEM image (Fig. 3D) also demonstrates the rough surface. The quantitative nanomechanical mapping provided Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) modulus, adhesion, and deformation images (Fig. 3L). The DMT modulus of the surface is 26.00 ± 11.53 MPa, which is consistent with the results of the strain-stress curve. The PPy-mesh sample was applied +1-V potential, and the surface conductivity was mapped using tunneling atomic force microscopy, indicating the conductive regions in the PPy-mesh (Fig. 3M). Collectively, the PPy-mesh–based microneedle array has low impedance, high capacitance, and appropriate mechanical properties to penetrate the epithelium and establish an ideal transdermal interface.

Features and applications of ISD system

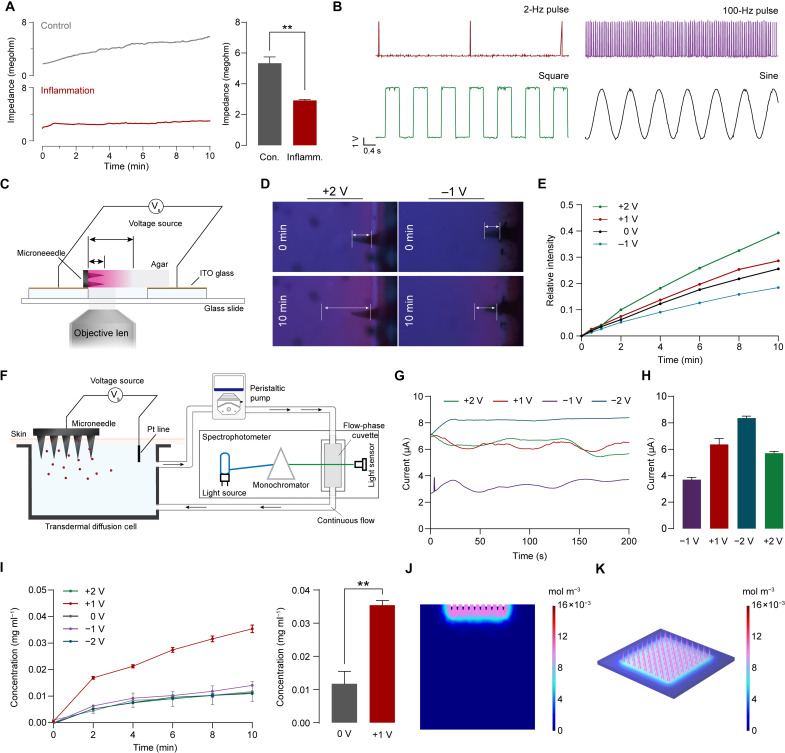

The reconfigurable feature of ISD allows for multimodality. The configuration of these modalities—including DAC, CUR, GND, and REF—enables the ISD to perform impedance sensing, electrical stimulation, and drug delivery. In the impedance sensing (DAC-CUR) configuration, the current–time curve allows for the extraction of tissue DC impedance, which provides the basis for real-time monitoring of RA activity. We found differences in impedance between inflammatory and normal tissues (Fig. 4A). In the electrical stimulation (DAC-GND) configuration, ISD can output short pulses with tunable frequency (from 2 to 100 Hz), sine, and square waveform for subsequent application (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Multimodal reconfigurable features of ISD for impedance sensing, electrical stimulation, and transdermal drug delivery.

(A) Representative transdermal impedance curve and the comparison of the normal and inflammatory tissue. (B) Characterization of the pulse, square and sine waveform generated. (C) Illustration of the device for observing the transport process. (D) Fluorescence images of the dye transport under +2- and −1-V bias voltage. (E) Quantification of fluorescence intensity with different times and voltages. (F) Illustration of a circulation device for real-time transdermal simulation. (G) Current-time curves (in absolute value) of the transdermal delivery in different potential biases. (H) Comparison of current at different bias voltages. (I) Concentration profiles versus time for different potential biases and comparison of concentrations after 10 min of transdermal delivery at 0-V and +1-V bias. (J) Distribution of the substance concentration in the tissue at +1-V bias. (K) Distribution of substance concentration in the microneedle at +1-V bias. ITO, indium tin oxide. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01

Transdermal substance delivery based on iontophoresis through the skin-microneedle interface is essential for drug treatment of RA under the control of reconfigurable electronics. First, the transport process was observed spatially and temporally through a device (Fig. 4C and fig. S15). Microneedles loaded with rhodamine B are placed on an indium tin oxide (ITO) conductive glass and inserted into a clear agar attached to another ITO glass. The ITO glass is applied to a constant voltage offset. The transport process in the agar is observed under the fluorescence microscope. The rate of delivery of rhodamine B in the agar varied with time and voltage. The intensity of the fluorescent signal and the depth of transport in agar increase with time and increase substantially with voltage (Fig. 4, D and E).

To simulate the drug delivery and drug content in circulation in vivo, a modified Franz diffusion cell was constructed (Fig. 4F). In this device, a diffusion cell is connected to a peristaltic pump and filled with phosphate-buffered solution to establish circulation. Fresh rat skin is fixed on the module and kept in contact with the liquid below. A quartz flow cell is introduced into the circulation and inserted into an ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer to analyze the concentration of substances in the circulating liquid. The concentrations of drugs were calibrated by standard curves (fig. S16). A voltage offset is applied to the microneedles to control the iontophoresis transport of small-molecule drug (rhodamine B). The current through the circuit varies at different voltages bias (Fig. 4G), which are correlated with voltage values from −2 to +1 V, however, when the voltage increased to +2 V, the current decreased (Fig. 4H). The concentration–time curves show that the drug concentration increased only slightly in 10 min when the voltage changed from −2 to 0 V and reaches the plateau at 4 min (Fig. 4I). The delivery rate increased substantially when +1-V bias was applied and did not show a notable decrease within 10 min. The concentration in the circulating fluid after 10 min is three times higher than that in the 0-V group. Notably, there is an unremarkable difference in delivery rate when the voltage was increased to +2 V. This is probably attributed to the oxidation of the conducting polymer at the interface by excessive voltage, resulting in a decrease in conductivity and mobility. The concentration profile of transdermal delivery of MTX under the same condition was also recorded (fig. S17).

To investigate the specific transport behavior of the system under certain thermodynamic and electric field conditions, a three-dimensional finite element model was developed and solved (table S1). In this model, the electric field is anisotropic (fig. S18). The drug distributed in the tissue shows a concentration gradient, while a small amount of drug remains in the microneedle (Fig. 4, J and K). On computational time scales, the drug concentration in the tissue at +1-V bias is substantially higher than that at 0-V bias (fig. S19).

Biocompatibility and biodegradability

Mouse fibroblasts (L929), mouse macrophage leukemia cells (RAW 264.7), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) are used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of PPy-mesh in vitro. The cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was performed, showing that the viability of the cells is maintained after coculture with different concentrations of PPy-mesh (fig. S20).

The PPy-mesh microneedle arrays were implanted subcutaneously in rats to assess biodegradability. Most of the PPy-mesh microneedle array was eliminated in 4 weeks, indicating the biodegradability properties of PPy-mesh (fig. S21). The biodegradation, local tissue, and systemic responses of PPy-mesh were evaluated in detail at 2 weeks after implantation (figs. S22 and S27, and table S2 and S3).

Anti-inflammatory mechanism of electrical stimulation

Macrophage is a crucial member in the pathogenesis of RA (35, 36). Many studies have demonstrated that electrical stimulation induces anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages (37). However, the mechanism of electrical stimulation-induced macrophage polarization to reduce inflammation is not well understood. To demonstrate the effectiveness of electrical stimulation to induce anti-inflammation in macrophages, RAW264.7 cells were cultured using a cell stimulator (Fig. 5A). Before electrical stimulation, M1-type macrophages were induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Macrophages were then stimulated at identical current densities for different durations: 0, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15 min. The cell viability (Fig. 5B) and live/dead cell staining (figs. S28 to S31) were used to measure the cytotoxicity of electrical stimulation. No notable cell death was observed after different times of electrical stimulation.

Fig. 5. Electrical stimulation regulates macrophage polarization.

(A) Schematic diagram of electrical stimulation of the cell. (B) Cytotoxicity of electrical stimulation. (C) Schematic diagram of macrophage polarization. (D) Pro-inflammatory factors under different electrical stimulation times. (E) Anti-inflammatory factors under different electrical stimulation time. (F) Western blot of the expression of key macrophage proteins (CD86, the label of M1 macrophage; CD206, the label of M2 macrophage) and band quantitative analysis. (G) Representative immunofluorescence images of labeled macrophages under different stimulation times. Scale bars, 200 μm. (H) Flow cytometry to detect the polarization of macrophages under different stimulation times. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. ns, not significant.

The initiation and progression of RA are closely related to the macrophage-mediated continuous accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the local microenvironment, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), as well as the reduction of anti-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-4 and IL-10 (3, 35, 38). Unpolarized macrophages are induced into M1 macrophages by LPS, followed by electrical stimulation to induce M2 polarization (Fig. 5C). The inflammatory factors of different groups were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Fig. 5, D and E show that 5 min of electrical stimulation promotes anti-inflammatory factors (IL-4 and IL-10) expression and inhibits the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-6). Western blot and immunofluorescence staining for the M1 macrophage marker CD86 and M2 macrophage maker CD206 (Fig. 5, F and G) confirm that 5 min of electrical stimulation up-regulates the expression of CD206 and down-regulates the expression of CD86, indicating that 5 min of electrical stimulation promotes the macrophage M2-type polarization, which is consistent with the results of flow cytometry (Fig. 5H).

Molecular mechanisms

To further explore the potential biological mechanisms of electrical stimulation for the treatment of RA, macrophages treated with LPS alone and electrical stimulation after LPS induction were then collected for transcriptome sequencing. The volcano plot shows the differentially expressed genes between the two groups (Fig. 6A), where the level of inflammatory genes had remarkable changes. The same trend is consistent with the cluster analysis in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6. The anti-inflammatory mechanism of electrical stimulation.

(A) Transcriptome sequencing analysis of differential genes in volcano plot. Gray is nonsignificantly differential genes, and yellow and blue are significantly different genes. (B) Clustering analysis of differential gene expression levels, where yellow indicates highly expressed protein-coding genes, and blue indicates relatively underexpressed protein-coding genes. (C) KEGG functional enrichment analysis. Larger bubbles contain more differentially encoded genes. The yellow-blue change in bubble color indicates that the smaller the P value for enrichment, the greater the significance. (D) Expression analysis of key genes in JAK/STAT signaling pathway. (E) Schematic diagram of the current stimulation regulation of macrophage polarization through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Normalized gene expression: (F) inflammatory effector genes and (G) inflammatory effector regulatory genes. Data are means ± SEM. (n = 3).

In Fig. 6C, we focus on the analysis of gene categories related to inflammatory immune regulation in the differential gene data: nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, NF-κB transcription factor activity, cell activation, etc. The results show that the biological effect of the electrical stimulation is related to the inflammatory pathways. Studies have shown that among the inflammatory pathways related to macrophage polarization, the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway can be activated under the stimulation of various inflammatory factors, thereby exerting signal transduction and transcriptional regulatory functions, affecting the differentiation and inflammation progression of macrophages (39, 40). We then analyzed the key genes in the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, which is associated with macrophage-mediated inflammatory response processes, and the results showed that current stimulation could inhibit its activation (Fig. 6, D and E). Figure 6F shows that the genes related to inflammation can be inhibited after electrical stimulation: Tnf, Cxcl10, and Mapkapk2 genes, their relative expression levels are reduced by 2.47-folds, 13.39-folds, and 2.29-folds, respectively. Among them, Cxcl10 is involved in the chemotaxis of cells and monocytes and promotes T cell adhesion and new blood vessel formation (41). Figure 6G shows that electrical stimulation promotes the expression of inflammation-regulated genes: The relative expressions of Il16 and Il17ra are increased by 3.01-folds and 3.84-folds. Il17ra is a pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by T lymphocytes and plays an important role in immune progression (42, 43). In summary, electrical stimulation inhibits the M1-type polarization of macrophages, regulates the expression of inflammation-related genes, and reduces the inflammatory response through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Compared to other stimulation modalities, such as drugs (44), pathogens (45), and cytokines (46), which modulate macrophages through inflammatory signaling pathways, electrical stimulation provides a local, controlled, and highly efficient approach.

Impedance sensing and machine learning model

Tissue impedance changes in the inflammatory condition and may indicate arthritic activity (23, 24, 47). We hypothesize that this impedance change in RA can be considered as an indicator for assessment of inflammation. To verify this, an adjuvant-induced arthritic (AIA) rat model was established to induce a local inflammatory response (Fig. 7A) (48). The clinical scores, paw thickness, and local temperature of the rats were continuously recorded during the experiment (Fig. 7, B to F). The thickness of the paw was measured as shown in Fig. 7E to quantitatively assess the swelling of the joint. Starting from day 0 after induction of inflammation, temperature, clinical score, and paw thickness increased, indicating that the immune adjuvant triggered an inflammatory response. Transdermal DC impedance was measured by ISD (Fig. 7G). In the experiment, the tissue impedance gradually increased until day 5, which may be related to the accumulation of interstitial fluid and inflammatory infiltration.

Fig. 7. Impedance sensing and synergistic treatment of RA on ISD.

(A) Schematic of the study design for inflammation model and the datasets. (B) Schematic diagram of the measurement of paw temperature of rats. (C) Paw temperature during the study. (D) Schematic diagram of the measurement of paw thickness of rats. (E) Paw thickness and (F) clinical score during the experiment. (G) Heatmap of the impedance of both groups. (H) Spearman correlation matrix of all variables included in the analyses. Blue shows significant positive correlations, white shows insignificant correlations, and red shows positive correlations. Values show the Spearman rank results. (I) Forest plot summarizing multivariable logistic regression evaluating odds ratio value for inflammation condition. (J) Predicted probability of the output of the regression model. (K) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plot with the area under the curve (AUC) values representing the prediction performance of inflammation using our model. (L) Schematic of the study design for the synergistic treatment of RA. (M) Photograph of the treatment procedure. (N) Body weight during treatment. (O) Paw thickness curve during animal treatment and comparison between synergistic treatment and control group. (P) Clinical score. (Q) Paw temperature. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns, not significant. ES, electrical stimulation; CI, confidence interval; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Spearman correlation matrix (Fig. 7H) shows a positive correlation between clinical score, thickness, temperature, and disease duration and no significant correlation between impedance and paw thickness or temperature. Therefore, the impedance parameter in this experiment was involved in the training dataset, along with temperature, thickness, and clinical score as independent variables to train a multivariate logistic regression model for inflammatory condition classification. The forest plot shows the odds ratio values of each variable on inflammatory condition (Fig. 7I). The classifier had an accuracy of 76.74% in distinguishing the inflammatory group from the control group by impedance (Fig. 7J). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve shows sensitivity and specificity of the model predictions in the test dataset, where the area under the curve value is 0.787 (Fig. 7K).

Synergistic treatment of arthritic rat model

Next, we evaluate the outcome of ISD for synergistic treatment of RA with electrical stimulation and drug delivery. An AIA rat model was established by subcutaneously injecting complete Freund’s adjuvant at the right hind paw (48). After 7 days of immunization, the paws of both hind limbs were swollen and warm (fig. S32). All arthritic rats were randomly divided into four groups and treated using the ISD with sham intervention (control), electrical stimulation (ES), methotrexate (drug), and MTX combined with electrical stimulation (ES and Drug) for 5 weeks (Fig. 7, L and M).

The weight, clinical score, and local temperature of rats were continuously recorded during the treatment. The thermographs of hind limbs were captured with an infrared thermal camera (fig. S33). During the 5-week treatment period, there is unremarkable difference in body weight between these groups (Fig. 7N). Paw thickness continued to improve in the ES and Drug group (Fig. 7O), with a remarkable decrease in clinical scores and local temperature (Fig. 7, P and Q). These results indicate that synergistic therapy through ISD could effectively reduce the inflammatory response, alleviate the symptoms of local joint inflammation, and improve clinical symptoms.

Histological evaluation and bone analysis

At the end of the treatment, all rats were euthanized, and the tissues were collected for histologic and immunohistochemistry (IHC) evaluation. Systematic biocompatibility was evaluated by histopathologic examination of the heart, liver, kidney, and lung. No notable pathological changes are found in the organs of all groups (figs. S34 to S36). Inflammatory factors (IL-4, IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α) in blood (Fig. 8, A to C) and tissues (Fig. 8, D to F) of rats were measured by ELISA, showing that drug, electrostimulation, and synergistic treatment all reduce the expression of pro-inflammatory factors and up-regulate the expression of anti-inflammatory in locally and systematically. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of bone-synovial tissue shows that the synergistic treatment substantially inhibits the structural damage and inflammatory infiltration of joint synovial tissue (Fig. 8G). IHC of macrophage markers in joint synovial tissue shows decreased expression of the M1 macrophage marker CD86 in the synergistic treatment group (Fig. 8H and fig. S37), while the expression of M2 macrophage marker CD206 increased (Fig. 8I). Micro–computed tomography was conducted to analyze bone and joint damage. Parameters including trabecular bone ratio, bone volume fraction, bone density, and trabecular separation/spacing were analyzed. Compared with the severe bone damage in the control group, the joints of the rats in the ES and Drug group are substantially improved after the synergistic treatment (Fig. 8J), and the bone damage is also controlled (Fig. 8K). The synergistic treatment combined transdermal MTX delivery with electrical stimulation of a ISD device exhibited more potent antirheumatic effects than that of traditional DMARDs, with notable symptom relief, reduced inflammatory response, and less damage in synovium and bone.

Fig. 8. Histopathology analysis.

(A) Schematic diagram of the analysis of inflammatory factors in blood samples by ELISA. (B) Pro-inflammatory and (C) anti-inflammatory factors in blood. (D) Schematic diagram of the analysis of inflammatory factors in synovium. (E) Pro-inflammatory and (F) anti-inflammatory factors in synovium tissue. (G) hematoxylin and eosin staining of the bone-synovial tissue. Scale bars, 100 μm. Synovial IHC analyses of the expression of (H) CD86 and (I) CD206. Scale bars, 100 μm. (J) 3D reconstructions of bone tissue via micro–computed tomography of right hind paws. Scale bar, 5 mm. (K) Bone analysis (trabecular bone ratio, bone volume fraction, bone density, and trabecular separation/spacing). ES, electrical stimulation. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

This work reported an integral wearable smart device consisting of reconfigurable electronics and conducting polymer-based microneedles. This device was applied for monitoring inflammation through impedance sensing and performing transdermal electrical stimulation and drug delivery. We demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of electrical stimulation, revealed its molecular mechanism, and verified that synergistic treatment with electrical stimulation and drugs substantially reduced inflammation in arthritic rats. Macroscopically, the concept of reconfigurable electronic hardware makes the signal control dynamic and flexible. The close coordination between material properties and electronic design allows for more comprehensive applications, enabling clinically diverse and complex therapies to be integrated into wearable systems. Notably, this system architecture is developed as a paradigm whose hardware and software flexibility offers therapeutic potential for many diseases, especially chronic diseases. After more experimental and clinical practices, complex diagnoses and treatment modalities for diseases can potentially be described and defined.

However, in this paper, some challenges remained. First, impedance sensing and corresponding machine learning models can only produce incomplete predictions about inflammatory conditions. It still does not satisfy clinical needs. Molecular mechanisms at the tissue level have yet to be explored. In the future, the therapeutic effect of this system also needs to be systemically evaluated in clinical experiments as the rat model cannot completely mimic the pathophysiology of human RA. For diseases with complicated pathophysiology, closed-loop diagnosis and treatment are to develop to validate the applications in other chronic diseases including diabetes, depression, etc.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of the circuit

Schematic diagrams and the circuit layouts for ISD circuit were designed using EasyEDA software (6.4.25). The components on the AFE include passive components (capacitors and resistors), amplifiers (OPA2378, OPA2251, OPA299, and INA317), multiplexers (TMUX1209 and ADG1604), and reference voltage source (REF3030). The components on the digital module include passive components (capacitors, resistors, inductors, and Zener diodes), radiofrequency devices (AN6520 multilayer chip antenna), and power converters (TPS65133 and TPS63001). The AFE connected to the digital module via a flexible PFC cable. Display (0.42″) and solar cell (KXOB25-04X3F) were connected to the digital module using customized connectors. The device encapsulation and the microneedle holder were designed using SolidWorks and AutoCAD. The models were sliced using Photon Workshop Software (2.1.26) with a layer thickness of 50 μm and fabricated with a digital light processing 3D printer (Anycubic Mono).

Synthesis of sodium 3-hydroxypropane-1-sulfonate

1,3-Propane sultone (2.50 g, 20 mmol) was added to a 50-ml flask. Then, 10 ml of NaOH (0.80 g, 20 mmol) solution was added dropwise. The mixture was heated to 60°C and maintained for 4 hours. The product was purified by recrystallization in ethanol.

Synthesis of PPy-OH

Pyrrole (0.71 ml, 10 mmol) and sodium 3-hydroxypropane-1-sulfonate (3.24 g, 20 mmol) were dissolved in 100 ml 50% (v/v) ethanol solution. Ammonium persulfate (APS) (4.56 g, 20 mmol) solution was slowly added under vigorous magnetic stirring. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours at 0°C and then quenched by 50% ethanol. The filtered precipitates were washed with distilled water, ethanol, and acetone three times. The resulting 3-hydroxypropane-1-sulfonate–doped PPy (PPy-OH) powder was dried in a vacuum oven at 50°C for 48 hours. After trituration, the PPy-OH powder was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide under ultrasound and vortex.

Synthesis of PPy-mesh

The precrosslinked PPy-acrylate solution was prepared by adding methacrylic anhydride (0.6 ml) to 10 ml of PPy-OH solution and stirring for 72 hours. The finished mixture was stored at 4°C for avoiding crosslinking spontaneously. For each microneedle, 160 μl of PEGDA and 40 μl of photoinitiator ethyl (2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phenylphosphinate were added into 2 ml of PPy-acrylate solution. The mixture was poured into the polydimethylsiloxane mold and stored under vacuum to fill the hole for times and then cured under 365-nm UV light for 40 min. The cured microneedle was washed with ethanol followed by solvent exchange with water to generate hydrogels.

Drug loading

The fluorescent dye (rhodamine B) and antirheumatic drug (MTX) can be loaded through the swelling effect. Aqueous solutions of rhodamine B and MTX were prepared with 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and diluted to a concentration of 10 and 5 mg ml−1, respectively. The prepared PPy-mesh microneedle was incubated in these solutions (5 ml) for 48 hours. The PPy-mesh microneedle was taken out and allowed to dry at room temperature.

Transdermal delivery

A modified Franz flow-through transdermal diffusion cell was used for in vitro transdermal iontophoresis. In a flow-through cell, the receptor fluid (1× PBS) is circulated through a peristaltic pump (NKCP-C-S10B, Kamoer) at a rate of 20 ml min−1. After leaving the cell, the fluid enters a quartz flow cuvette cell, which allows a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to acquire spectra of the receptor fluid simultaneously. The total volume of receptor fluid is 14 ml. The abdominal and dorsal skin with complete epidermal, dermal, and hypodermal tissue were obtained from euthanized rats (Sprague-Dawley, 6 to 8 weeks, no pigmented). The obtained skin was washed with 0.9% saline three times and stored at 4°C. The skin surface temperature in the diffusion cell was maintained at 32° ± 1°C. The ISD mounted with rhodamine B–loaded microneedles was positioned on the surface of obtained rat skin. A consistent force of ~10 N was applied to penetrate the skin. Under physiological conditions, rhodamine B is positively charged and MTX is negatively charged (49, 50). To simplify discussion, the voltage bias when delivering the MTX is shown as the inverse of the actual value.

Cell culture

High-glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, USA) and RPMI 1640 (Gibco, USA) were used to culture mouse macrophage leukemia cells (RAW 264.7), HUVECs, and mouse fibroblast (L929). The cell culture medium contained streptomycin and penicillin. All cell lines were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Cell Medicine, Chinese Academy of Sciences and cultured in a cell incubator at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide.

Cell electrical simulation

Platinum electrodes were mounted on the lid of a six-well plate and extended to the bottom of the wells. Two electrodes were connected to the function generator. The pulse amplitude used in this study was 1000 mV at a frequency of 10 Hz. In the experimental group, RAW264.7 cells were stimulated for different durations. Subsequent analyses were performed after 24 hours.

Animals

Sprague-Dawley male rats (10 to 12 weeks old) were initially purchased from the Hunan STA Laboratory Animal Co. LTD and bred in the animal facility of Nanchang University. The rats were housed three to five rats per cage with ad libitum access to food and water and were maintained in a room (22 ± 2°C) under a 12-hour light and 12-hour dark cycle (light on at 7:00 a.m. and off at 7:00 p.m.). All animal experiments were performed under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China (SYXK 2018-0006).

Local inflammation models and regression prediction

The unilateral adjuvant-induced arthritis models (n = 12) were via subcutaneous injection of 10 μl of complete Freund’s adjuvant of the right hind paw. In the control group, 10 μl of saline was injected subcutaneously into the right hind paw. The weight, clinical score, transdermal impedance, temperature, and paw thickness were routinely recorded until the experiment was terminated after 9 days. The collected dataset was labeled and randomly divided into 70% training dataset and 30% testing dataset. The training dataset of signs and impedances was used for the training of multivariable logistic regression prediction models. The multiple logistic regression model can be represented by the following equation

| (1) |

where is the expected probability that the outcome is present, Xn are distinct independent variables, and βn are the regression coefficients.

AIA models

AIA models (n = 3) in this experiment were performed according to previous studies (48). Arthritis was induced via subcutaneous injection of 100 μl of complete Freund’s adjuvant at the plantar surface of the right hind paw. After 7 days, a booster dose of complete Freund’s adjuvant injection (20 μl) was administered. Animals were assigned to the following groups: blank group, control group, drug group, electrical stimulation (ES) group, and synergistic treatment (ES and Drug) group. Each group was treated as follows: The blank group did not have complete Freund’s adjuvant or ISD treatment. The control group did not have ISD treatment. The drug group was administered approximately 1 mg/kg dose of MTX every 2 days using the ISD transdermal drug delivery, and the administration parameters (10 min, +1 V) were based on the results of in vitro transdermal delivery. ES group received electrical stimulation (10 Hz) via ISD every 2 days. The ES and Drug group received electrical stimulation and transdermal MTX delivery using ISD every 2 days. During treatment, the ISD mounted with microneedles was positioned on the plantar aspect of the rat’s hind paw. A force of approximately 10 N was applied to the device to penetrate the skin and secured with medical tape. The weight, clinical score, temperature, and paw thickness were routinely recorded until the experiment was terminated after 5 weeks.

Statistical analysis

All the data obtained in this study were described as means ± SD and analyzed by GraphPad Prism 9. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the normality. Normally distributed data were analyzed by Student’s t test, while data not normally distributed were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The probability value (P value) < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to appreciate the support of D. Zhong in the development of conductive polymers.

Funding: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31860263 to X.W. and 81760408 to J.L.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2020YFC2005800 to J.L.), Key Youth Project of Jiangxi Province (20202ACB216002 to X.W.), Key Research and Development Program of Jiangxi Province (20212BBG73004 to X.W.), and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20113BCB22005 and 20181BCG42001 to J.L.).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Y.L. and W.X. Methodology: Y.L., W.X., Z.Tang, Z.Tan, and Y.H. Investigation: Y.L., W.X., and Z.Tang. Visualization: W.X. Supervision: X.W. and J.L. Writing—original draft: Y.L. and W.X. Writing—review and editing: X.W., Y.L., and W.X.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S37

Tables S1 to S3

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Safiri S., Kolahi A. A., Hoy D., Smith E., Bettampadi D., Mansournia M. A., Almasi-Hashiani A., Ashrafi-Asgarabad A., Moradi-Lakeh M., Qorbani M., Collins G., Woolf A. D., March L., Cross M., Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 78, 1463–1471 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matteo A. D., Bathon J. M., Emery P., Rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet 402, 2019–2033 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen J. S., Aletaha D., Barton A., Burmester G. R., Emery P., Firestein G. S., Kavanaugh A., McInnes I. B., Solomon D. H., Strand V., Yamamoto K., Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18001 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikiphorou E., Santos E. J. F., Marques A., Böhm P., Bijlsma J. W., Daien C. I., Esbensen B. A., Ferreira R. J. O., Fragoulis G. E., Holmes P., McBain H., Metsios G. S., Moe R. H., Stamm T. A., de Thurah A., Zabalan C., Carmona L., Bosworth A., 2021 EULAR recommendations for the implementation of self-management strategies in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 80, 1278–1285 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodenheimer T., Patient Self-management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA 288, 2469 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraenkel L., Bathon J. M., England B. R., Clair E. W. S., Arayssi T., Carandang K., Deane K. D., Genovese M., Huston K. K., Kerr G., Kremer J., Nakamura M. C., Russell L. A., Singh J. A., Smith B. J., Sparks J. A., Venkatachalam S., Weinblatt M. E., Al-Gibbawi M., Baker J. F., Barbour K. E., Barton J. L., Cappelli L., Chamseddine F., George M., Johnson S. R., Kahale L., Karam B. S., Khamis A. M., Navarro-Millán I., Mirza R., Schwab P., Singh N., Turgunbaev M., Turner A. S., Yaacoub S., Akl E. A., 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 73, 1108–1123 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pelland L., Brosseau L., Casimiro L., Welch V., Tugwell P., Wells G. A., Electrical stimulation for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavuncu V., Evcik D., Physiotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. MedGenMed 6, 3 (2004). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikiphorou E., Konan S., MacGregor A. J., Haddad F. S., Young A., The surgical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Bone Joint J. 96-B, 1287–1289 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoekstra M., Haagsma C., Neef C., Proost J., Knuif A., van de Laar M., Bioavailability of higher dose methotrexate comparing oral and subcutaneous administration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 31, 645–648 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon D. H., Glynn R. J., Karlson E. W., Lu F., Corrigan C., Colls J., Xu C., MacFadyen J., Barbhaiya M., Berliner N., Dellaripa P. F., Everett B. M., Pradhan A. D., Hammond S. P., Murray M., Rao D. A., Ritter S. Y., Rutherford A., Sparks J. A., Stratton J., Suh D. H., Tedeschi S. K., Vanni K. M. M., Paynter N. P., Ridker P. M., Adverse effects of low-dose methotrexate: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, 369–380 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam J. L., Takase-Minegishi K., Ramiro S., Chatzidionysiou K., Smolen J. S., van der Heijde D., Bijlsma J. W., Burmester G. R., Dougados M., Scholte-Voshaar M., van Vollenhoven R., Landewé R., Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: A systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 76, 1113–1136 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolen J. S., Landewé R. B. M., Bijlsma J. W. J., Burmester G. R., Dougados M., Kerschbaumer A., McInnes I. B., Sepriano A., van Vollenhoven R. F., de Wit M., Aletaha D., Aringer M., Askling J., Balsa A., Boers M., den Broeder A. A., Buch M. H., Buttgereit F., Caporali R., Cardiel M. H., De Cock D., Codreanu C., Cutolo M., Edwards C. J., van Eijk-Hustings Y., Emery P., Finckh A., Gossec L., Gottenberg J.-E., Hetland M. L., Huizinga T. W. J., Koloumas M., Li Z., Mariette X., Müller-Ladner U., Mysler E. F., da Silva J. A. P., Poór G., Pope J. E., Rubbert-Roth A., Ruyssen-Witrand A., Saag K. G., Strangfeld A., Takeuchi T., Voshaar M., Westhovens R., van der Heijde D., EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 79, 685–699 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koyama A., Tanaka A., H. To , Daily oral administration of low-dose methotrexate has greater antirheumatic effects in collagen-induced arthritis rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 69, 1145–1154 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas C. J., Dimmitt S. B., Martin J. H., Optimising low-dose methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis—A review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 85, 2228–2234 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson J., Caplan L., Yazdany J., Robbins M. L., Neogi T., Michaud K., Saag K. G., O'dell J. R., Kazi S., Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res. 64, 640–647 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konijn N. P. C., van Tuyl L. H. D., Bultink I. E. M., Lems W. F., Earthman C. P., van Bokhorst-de van der Scheren M. A. E., Making the invisible visible: Bioelectrical impedance analysis demonstrates unfavourable body composition in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical practice. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 43, 273–278 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yılmaz V., Umay E., Gündoğdu İ., Karaahmet Z. Ö., Öztürk A. E., Rheumatoid Arthritis: Are psychological factors effective in disease flare? Eur. J. Rheumatol. 4, 127–132 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Margaretten M., Julian L., Katz P., Yelin E., Depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Description, causes and mechanisms. Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 6, 617–623 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yetisen A. K., Martinez-Hurtado J. L., Ünal B., Khademhosseini A., Butt H., Wearables in Medicine. Adv. Mater. 30, e1706910 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee M. S., Shin B.-C., Ernst E., Acupuncture for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Rheumatology 47, 1747–1753 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng C., Li H., Yang T., Deng Z.-H., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Lei G.-H., Electrical stimulation for pain relief in knee osteoarthritis: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 23, 189–202 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song J. W., Ryu H., Bai W., Xie Z., Vázquez-Guardado A., Nandoliya K., Avila R., Lee G., Song Z., Kim J., Lee M.-K., Liu Y., Kim M., Wang H., Wu Y., Yoon H.-J., Kwak S. S., Shin J., Kwon K., Lu W., Chen X., Huang Y., Ameer G. A., Rogers J. A., Bioresorbable, wireless, and battery-free system for electrotherapy and impedance sensing at wound sites. Sci. Adv. 9, eade4687 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim C., Hong Y. J., Jung J., Shin Y., Sunwoo S.-H., Baik S., Park O. K., Choi S. H., Hyeon T., Kim J. H., Lee S., Kim D.-H., Tissue-like skin-device interface for wearable bioelectronics by using ultrasoft, mass-permeable, and low-impedance hydrogels. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd3716 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D., Chen K., Tang H., Hu S., Xin L., Jing X., He Q., Wang S., Song J., Mei L., Cannon R. D., Ji P., Wang H., Chen T., A logic-based diagnostic and therapeutic hydrogel with multistimuli responsiveness to orchestrate diabetic bone regeneration. Adv. Mater. 34, e2108430 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piech D. K., Johnson B. C., Shen K., Ghanbari M. M., Li K. Y., Neely R. M., Kay J. E., Carmena J. M., Maharbiz M. M., Muller R., A wireless millimetre-scale implantable neural stimulator with ultrasonically powered bidirectional communication. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 207–222 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuk H., Lu B., Zhao X., Hydrogel bioelectronics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 1642–1667 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheah K., Forsyth M., Truong V.-T., Ordering and stability in conducting polypyrrole. Synth. Met. 94, 215–219 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanches E. A., Alves S. F., Soares J. C., da Silva A. M., da Silva C. G., de Souza S. M., da Frota H. O., Nanostructured polypyrrole powder: A structural and morphological characterization. J. Nanomater. 2015, e129678 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tabačiarová J., Mičušík M., Fedorko P., Omastová M., Study of polypyrrole aging by XPS, FTIR and conductivity measurements. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 120, 392–401 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C., Suo Z., Hydrogel ionotronics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 125–142 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aziz B., Employing of Trukhan model to estimate ion transport parameters in PVA based solid polymer electrolyte. Polymers 11, 1694 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuk H., Lu B., Lin S., Qu K., Xu J., Luo J., Zhao X., 3D printing of conducting polymers. Nat. Commun. 11, 1604 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feig V. R., Tran H., Lee M., Bao Z., Mechanically tunable conductive interpenetrating network hydrogels that mimic the elastic moduli of biological tissue. Nat. Commun. 9, 2740 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang X., Chang Y., Wei W., Emerging role of targeting macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis: Focus on polarization, metabolism and apoptosis. Cell Prolif. 53, e12854 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinne R. W., Bräuer R., Stuhlmüller B., Palombo-Kinne E., Burmester G.-R., Macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2, 189–202 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C., Levin M., Kaplan D. L., Bioelectric modulation of macrophage polarization. Sci. Rep. 6, 21044 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malmström V., Catrina A. I., Klareskog L., The immunopathogenesis of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: From triggering to targeting. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17, 60–75 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan Z., Gibson S. A., Buckley J. A., Qin H., Benveniste E. N., Role of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway in regulation of innate immunity in neuroinflammatory diseases. Clin. Immunol. 189, 4–13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McInnes I. B., Schett G., Pathogenetic insights from the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The Lancet 389, 2328–2337 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antonelli A., Ferrari S. M., Giuggioli D., Ferrannini E., Ferri C., Fallahi P., Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL)10 in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 13, 272–280 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corneth O. B. J., Mus A. M. C., Asmawidjaja P. S., Klein Wolterink R. G. J., van Nimwegen M., Brem M. D., Hofman Y., Hendriks R. W., Lubberts E., Absence of interleukin-17 receptor a signaling prevents autoimmune inflammation of the joint and leads to a Th2-like phenotype in collagen-induced Arthritis. Rheumatology 66, 340–349 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gaffen S. L., Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 556–567 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Y., Liang Q., Zhou L., Cao Y., Yang J., Li J., Liu J., Bi J., Liu Y., An ROS-responsive artesunate prodrug nanosystem co-delivers dexamethasone for rheumatoid arthritis treatment through the HIF-1α/NF-κB cascade regulation of ROS scavenging and macrophage repolarization. Acta Biomater. 152, 406–424 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stapels D. A. C., Hill P. W. S., Westermann A. J., Fisher R. A., Thurston T. L., Saliba A.-E., Blommestein I., Vogel J., Helaine S., Salmonella persisters undermine host immune defenses during antibiotic treatment. Science 362, 1156–1160 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faas M., Ipseiz N., Ackermann J., Culemann S., Grüneboom A., Schröder F., Rothe T., Scholtysek C., Eberhardt M., Böttcher M., Kirchner P., Stoll C., Ekici A., Fuchs M., Kunz M., Weigmann B., Wirtz S., Lang R., Hofmann J., Vera J., Voehringer D., Michelucci A., Mougiakakos D., Uderhardt S., Schett G., Krönke G., IL-33-induced metabolic reprogramming controls the differentiation of alternatively activated macrophages and the resolution of inflammation. Immunity 54, 2531–2546.e5 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pineda-Juárez J. A., Lozada-Mellado M., Ogata-Medel M., Hinojosa-Azaola A., Santillán-Díaz C., Llorente L., Orea-Tejeda A., Alcocer-Varela J., Espinosa-Morales R., González-Contreras M., Castillo-Martínez L., Body composition evaluated by body mass index and bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrition 53, 49–53 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choudhary N., Bhatt L. K., Prabhavalkar K. S., Experimental animal models for rheumatoid arthritis. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 40, 193–200 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rasouli S., Davaran S., Rasouli F., Mahkam M., Salehi R., Synthesis, characterization and pH-controllable methotrexate release from biocompatible polymer/silica nanocomposite for anticancer drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 21, 155–163 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kornprobst T., Plank J., Photodegradation of Rhodamine B in Presence of CaO and NiO-CaO Catalysts. Int. J. Photoenergy 2012, 398230 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brosseau L., Judd M. G., Marchand S., Robinson V. A., Tugwell P., Wells G., Yonge K., Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in the hand. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD004377 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tada M., Inui K., Okano T., Mamoto K., Koike T., Nakamura H., Safety of intra-articular methotrexate injection with and without electroporation for inflammatory small joints in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Med. Insights: Arthritis Musculoskelet. Disord. 12, 1179544119886303 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanaka Y., Subcutaneous injection of methotrexate: Advantages in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 33, 633–639 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee H., Song C., Baik S., Kim D., Hyeon T., Kim D.-H., Device-assisted transdermal drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 127, 35–45 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jiang Y., Trotsyuk A. A., Niu S., Henn D., Chen K., Shih C.-C., Larson M. R., Mermin-Bunnell A. M., Mittal S., Lai J.-C., Saberi A., Beard E., Jing S., Zhong D., Steele S. R., Sun K., Jain T., Zhao E., Neimeth C. R., Viana W. G., Tang J., Sivaraj D., Padmanabhan J., Rodrigues M., Perrault D. P., Chattopadhyay A., Maan Z. N., Leeolou M. C., Bonham C. A., Kwon S. H., Kussie H. C., Fischer K. S., Gurusankar G., Liang K., Zhang K., Nag R., Snyder M. P., Januszyk M., Gurtner G. C., Bao Z., Wireless, closed-loop, smart bandage with integrated sensors and stimulators for advanced wound care and accelerated healing. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 652–662 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu J., Wu C., He X., Chen X., Dong L., Weng W., Cheng K., Wang D., Chen Z., Enhanced M2 polarization of oriented macrophages on the P(VDF-TrFE) film by coupling with electrical stimulation. ACS Biomater Sci. Eng. 9, 2615–2624 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu H., Dong H., Tang Z., Chen Y., Liu Y., Wang M., Wei X., Wang N., Bao S., Yu D., Wu Z., Yang Z., Li X., Guo Z., Shi L., Electrical stimulation of piezoelectric BaTiO3 coated Ti6Al4V scaffolds promotes anti-inflammatory polarization of macrophages and bone repair via MAPK/JNK inhibition and OXPHOS activation. Biomaterials 293, 121990 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Franz S., Rammelt S., Scharnweber D., Simon J. C., Immune responses to implants – A review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials. Biomaterials 32, 6692–6709 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adusei K. M., Ngo T. B., Sadtler K., T lymphocytes as critical mediators in tissue regeneration, fibrosis, and the foreign body response. Acta Biomater. 133, 17–33 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Materials and Methods

Supplementary Text

Figs. S1 to S37

Tables S1 to S3

References