Summary

Background

It is known that gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)-complicated pregnancies could affect maternal cardiometabolic health after delivery, resulting in hepatic dysfunction and a heightened risk of developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Hence, this study aims to summarise existing literature on the impact of GDM on NAFLD in mothers and investigate the intergenerational impact on NAFLD in offspring.

Methods

Using 4 databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus) between January 1980 and December 2023, randomized controlled trials and observational studies that assessed the effect of maternal GDM on intergenerational liver outcomes were extracted and analysed using random-effects meta-analysis to investigate the effect of GDM on NAFLD in mothers and offspring. Pooled odds ratio (OR) was calculated using hazards ratio (HR), relative risk (RR), or OR reported from each study, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), and statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the Cochran Q-test and I2 statistic, with two-sided p values. The study protocol was pre-registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023392428).

Findings

Twenty studies pertaining to mothers and offspring met the inclusion criteria and 12 papers were included further for meta-analysis on intergenerational NAFLD development. Compared with mothers without a history of GDM, mothers with a history of GDM had a 50% increased risk of developing NAFLD (OR 1.50; 95% CI: 1.21–1.87, over a follow-up period of 16 months–25 years. Similarly, compared with offspring born to non-GDM-complicated pregnancies, offspring born to GDM-complicated pregnancies displayed an approximately two-fold elevated risk of NAFLD development (2.14; 1.57–2.92), over a follow-up period of 1–17.8 years.

Interpretation

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that both mothers and offspring from GDM-complicated pregnancies exhibit a greater risk to develop NAFLD. These findings underline the importance of early monitoring of liver function and prompt intervention of NAFLD in both generations from GDM-complicated pregnancies.

Funding

No funding was available for this research.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Intergenerational impact, Maternal postpartum, Offspring

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in pregnancy can have lasting impacts on maternal cardiometabolic health post-delivery, potentially leading to hepatic dysfunction and an increased risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) development. Before commencing this study, we conducted a brief literature review focusing on the association between GDM and the onset of NAFLD in both mothers and offspring following delivery. Specifically, on January 1, 2023, we utilized specific search terms (“gestational diabetes mellitus” OR “diabetes during pregnancy” OR “hyperglycemia in pregnancy”) AND (“fatty liver” OR “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “liver function”). This search initially identified 96 articles for screening. However, we found no systematic review that holistically summarized the research findings regarding the relationship between GDM and the development of intergenerational NAFLD. Our study aims to address this critical gap in knowledge.

Added value of this study

In this systematic review of 20 studies with a combined population of over 71 million women and 9800 offspring, 12 studies of which was further included in a meta-analysis. We observed that pregnancies complicated by GDM was associated with a 50% increased risk of developing NAFLD in mothers. This risk doubled in their offspring. These intergenerational associations extended to liver-related dysfunctions, encompassing elevated levels of circulating liver enzymes, enlarged liver size, and heightened liver stiffness.

Implications of all the available evidence

Given the susceptibility to intergenerational NAFLD even within the initial year after delivery, healthcare practitioners should consider integrating routine liver function and imaging assessments in the postnatal care of mother-offspring pairs affected by GDM, ensuring early detection and intervention.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), characterized by the development of hyperglycemia during pregnancy in mothers without pre-existing diabetes, is experiencing a significant increase in prevalence, mirroring the global obesity epidemic.1 Emerging evidence indicates that GDM affects a wide range of women, from 1% to >30% globally, with exceptionally high rates observed in Asia–Pacific and the Middle East regions.2 Similar to type 2 diabetes (T2D), modifiable risk factors attributable to GDM include advanced maternal age, excessive adiposity, inadequate physical activity prior to conception, and excessive gestational weight gain.2, 3, 4, 5 Public health awareness surrounding GDM has witnessed significant growth, primarily driven by the recognition of various adverse cardio-metabolic health outcomes in mothers (e.g., pre-eclampsia, T2D)2,3,6, 7, 8 and offspring (e.g., macrosomia, neuro-cognitive dysfunction, and juvenile T2D).9, 10, 11 These outcomes have resulted in population health concerns and an increased burden on medical resources.11 A substantial body of evidence suggests that GDM has the potential to permanently alter metabolic programming and physiology, thus contributing to metabolic disturbances in both mothers and their offspring.12 Recent studies have identified associations between GDM and adverse metabolic conditions such as obesity,13 insulin resistance,14 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).15

NAFLD, more recently coined as “metabolic associated fatty liver disease” (MAFLD) in 202016 and subsequently as “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease” (MASLD) in 2023,17 represents a significant paradigm shift aimed at more precisely encapsulating the aetiological underpinnings of this condition. This chronic liver ailment stands as a poignant testament to the intricate interplay between metabolic syndrome and hepatic health.18,19 Its hallmark feature is the aberrant accumulation of fat within the liver, and it notably afflicts individuals with no prior record of excessive alcohol consumption.18,19 Considered the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, the prevalence of NAFLD in general population is 24.4% in adults20 and 7.6% in children,21 with a markedly higher prevalence observed in populations affected by obesity, T2D, or high-income levels.20,21 Pathogenesis of NAFLD involves “multiple hits”, including fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and inflammation in the liver.22,23 Encompassing a spectrum of clinical phenotypes, manifestations range from simple macrovesicular steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).24 Furthermore, the progression of NAFLD in children is an emerging concern, as research suggests that paediatric NAFLD can lead to substantial liver injury at an earlier stage in life compared to the general population.25, 26, 27, 28

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to consolidate and update the existing literature on maternal postpartum NAFLD resulting from GDM and investigate the intergenerational impact of GDM on offspring NAFLD. Our hypothesis posits that GDM in mothers is associated with the future development of NAFLD in mothers and offspring, independent of body mass index.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

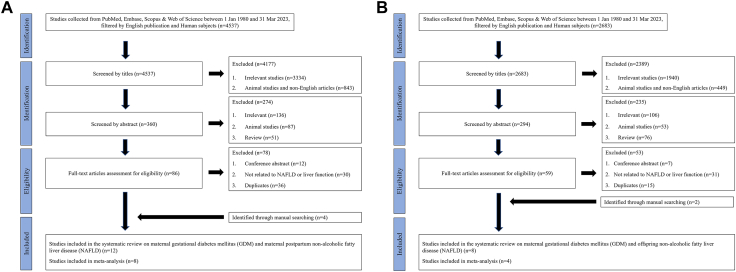

We conducted the systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement for standard protocols.29 References for this systematic review were identified through searches of four main databases (i.e., PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus) for articles published between January 1, 1980, and December 31, 2023. Since we were interested in intergenerational impact on liver adverse outcomes related to maternal GDM, we included two topics in our review. They are “Topic 1—maternal GDM and postpartum maternal NAFLD” and “Topic 2—maternal GDM and offspring NAFLD”. Search terms for Topic 1 and Topic 2 were listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Articles resulting from these searches and relevant references cited in those articles were reviewed, among which those reporting non-human subjects, written in non-English language or without full-text available were excluded. Also, studies that reported NAFLD increasing the risk of GDM, Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus increasing risk of NAFLD, and conference abstracts were excluded. Flow charts for literature searching on each topic are shown in Fig. 1A & B. This review was registered at PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) with the registration No. CRD42023392428. Ethical approval was not required for this study, as the information reviewed was publicly available and desensitised.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of systematic review literature searching scheme. Fig. 1A depicts the searching scheme of maternal postpartum NAFLD in women with a history of GDM; Fig. 1B depicts the searching scheme of offspring NAFLD born to a GDM-complicated pregnancy.

Exposure ascertainment—identify gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

In our systematic review, GDM was identified primarily through the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT), guided by various established criteria such as the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) guidelines,30 the 1999 World Health Organization guidelines,31 and the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) guidelines,32 and others where applicable. Secondary diagnoses of GDM included confirmation of medical record review using specific codes such as the International Classification of Disease (ICD)-10 codes O24.4 and O24.9, or through patient self-reported questionnaires.

Outcome ascertainment—identify non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

The primary diagnostic criteria for the outcome measures related to NAFLD were derived from abdominal ultrasonography and transient elastography (FibroScan), with a Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) (cut-off might vary).33 Secondary diagnoses of NAFLD were established through a review of medical records and application of the Fatty Liver Index (FLI), assessment via computed tomography (CT) scans, and magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy, in accordance with relevant guidelines described in respective studies.

Data extraction and assessment of quality

Double literature searching was conducted during the literature searching phase by two investigators (R.X.F. & J.J.M.) and results were verified, and discrepancies (if any) were evaluated by a third investigator (L.-J.L.). Furthermore, two investigators (R.X.F. & J.J.M.) performed the quality assessments for all papers based on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale Criteria (NOSC)34 and a third investigator (L.-J.L.) assessed the findings independently. The maximum score of 9 points in the NOSC is distributed in three aspects based on the study groups, namely selection of study groups (four points), comparability of groups (two points), and ascertainment of exposure and outcomes (three points) for case–control and cohort studies. We used the points to further categorize the publication quality with low risk of bias (between 7 and 9 points), high risk of bias (between 4 and 6 points), and very high risk of bias (between 0 and 3 points).35

With the final article count for each generation (mother and offspring), we further extracted information from each study: number of participants and those with prior GDM, mean age, race/ethnicity, follow-up duration, GDM diagnosis method, assessment of liver outcomes, effect size and adjustments for covariates. Studies which directly investigated maternal GDM in index pregnancy and intergenerational NAFLD diagnosis were included in the meta-analysis, while the systematic review also encompassed studies reporting alternative liver outcomes such as diagnosis of other liver disease, liver biomarkers or liver size. Studies identified to be at higher risk of bias were assigned a lower weightage in the calculation for overall effect size.

Statistics

We conducted data analysis by treating GDM as the independent variable and NAFLD in mothers or offspring as the dependent variable, we calculated a pooled odds ratio (OR) using random-effects meta-analysis of hazards ratio (HR), relative risk (RR), or OR from each study. The conversion between HR and OR36 and between RR and OR37 was calculated according to validated methods. We chose to apply random-effects meta-analysis over fixed-effect meta-analysis, acknowledging the concern of unexplained variance even in the presence of identifiable sources of heterogeneity.38, 39, 40 This approach allowed us to accommodate variability and inter-study differences in treatment effects, enhancing the potential for clinical decision-making and practice within a longitudinal timeline.38, 39, 40

We included the risk estimate with the most extensive statistical adjustment from individual studies in the meta-analysis. If the pooled OR along with its respective 95% confidence interval (CI) is entirely above 1.0 or entirely below 1.0, we infer a significant positive or inverse association between GDM and NAFLD in mothers or offspring. We evaluated statistical heterogeneity using the Cochran Q-test41 and I2 statistic, defining levels as mild, moderate, substantial and high heterogeneity based on I2 values falling within the ranges of 0–25%, 25–50%, 50–75%, and 75–100%, respectively.42,43 Publication bias was assessed visually with funnel plots and with the Egger44,45 (linear regression method) and Begg-Mazumdar46 regression tests (rank correction method), and a p value <0.05 was considered representative of statistically significant publication bias.45,46 All analyses were conducted with Stata, version 17.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). All p values were from 2-sided tests, and the results were deemed statistically significant at p < 0.05 unless stated otherwise.

To comprehensively explore subgroup differences and potential sources of observed heterogeneity, we conducted a series of subgroup analyses based on various study characteristics. Firstly, we stratified characteristics including study race/ethnicity (exclusive Asian or mixed population yet primarily composed of Caucasians), median duration of follow-up (>10 years or ≤ 10 years), method for ascertaining GDM (medical code or self-reporting), and study quality (low risk of bias or moderate-to-high risk of bias). To assess the potential mediating role of subsequent development of T2D underlying the association between GDM and NAFLD, we examined the ORs for NAFLD in women who had T2D comorbidity and those who did not specify. Secondly, we stratified based on the inclusion of certain confounders which are known to influence the association between GDM and NAFLD. These analyses were stratified by major covariates, including age, BMI (e.g., pre-pregnancy BMI, study entry BMI), lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption), socioeconomic status (e.g., education, household income, housing size), parity, pregnancy complications (e.g., hypertensive disorders during pregnancy), and systemic comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, T2D). Q-test based on one-way ANOVA41 were conducted using the R package (R 4.2.2) and statistical significance for any difference in estimates between subgroups was determined with a two-sided p value threshold of <0.10.

Role of funding source

No funding was available for this research.

Results

Fig. 1 presents the search and screening results across all 4 databases for GDM leading to increased risk of liver dysfunction in mothers (Fig. 1A) and in offspring (Fig. 1B), respectively. Supplementary Table S3 summarizes the characteristics and quality scores of the 12 studies in mothers (n = 71,758,188, age range: 18–>65 years) and 8 publications in offspring (n = 9832 age range: 2–35 years) related to GDM-complicated pregnancies, respectively. Within the realm of clinical liver outcomes in both mothers and offspring, including hepatic steatosis, liver fibrosis, and liver failure.

GDM and clinical liver outcomes in mothers

Among the 12 papers reporting clinical liver outcomes, eleven papers47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 reported NAFLD or NASH with various definitions (Supplementary Table S3). Four of the 11 studies were conducted in the US, two in Denmark, while the rest five were in Canada, England, Taiwan, South Korea and India, respectively. The sample sizes ranged from 89 to 70,990,695, and the ages of the study populations spanned from 18 to over 65 years. The reported incidence rates varied from 0.2 to 437 cases per 1000 person-years (Supplementary Table S3). In terms of clinical liver outcomes, clinical diagnosis or assessment included abdominal ultrasonography,48,52,54,55 Fibroscan (vibration controlled transient elastography) with the Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) score,49,53,54 and the utilization of Fatty Liver Index50 calculated using a formula incorporating waist circumference, body mass index (BMI), triglyceride, and gamma-glutamyl-transferase (GGT) levels (Supplementary Table S3). Within this context, seven articles reported a positive association between GDM and a 1.23–2.7-fold heightened risk of maternal NAFLD or NASH following the index pregnancy,47,48,50,52,54, 55, 56 while four papers reported a null association.49,51,53,57

For the three studies from India by Kubihal et al.,54 Canada by Retnakaran et al.58 and US by Ciardullo et al.49 alternative clinical liver outcomes were further reported, namely liver fibrosis and liver complications documented based on medical record during in-patient hospitalization, respectively (Supplementary Table S3). Liver fibrosis was assessed using Fibroscan (elastography) with the Liver Stiffness Measurement (LSM) score.49,54 Interestingly, Kubihal et al.54 showed an increased prevalence of liver fibrosis among mothers with a history of GDM than those without (18.1% vs. 9.4%, p = 0.04) while Ciardullo et al. did not find any difference in liver fibrosis prevalence between mothers with and without GDM (10.2% vs. 0.5%, p = 0.85).49 Moreover, Retnakaran et al., reported a 40% increased risk (HR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.94) of any type of liver disease development among mothers with a history of GDM, compared with those without.58

GDM and clinical liver outcomes in offspring

In this category, a total of eight papers59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66 reported offspring with development of NAFLD or NASH after GDM-complicated index pregnancy (Supplementary Table S3). Two of the eight studies were conducted in the UK, while the rest six were conducted in Canada, China, the Netherlands, US, Australia, and Pakistan, respectively. The sample sizes ranged from 33 to 5 104, and age of the study populations varied from 20 weeks of gestation to 35 years. The reported incidence of NAFLD rates varied from 1 to 17 cases per 1000 person-years (Supplementary Table S3). In terms of outcomes, the majority of studies assessed NAFLD or NASH using abdominal ultrasonography59,63,64,66 or magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy,61,62 while a couple of them used either Fibroscan (elastography) with the Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) score60 or pathohistological examination (i.e., H&E-stained liver slides) on stillborn subjects65 (Supplementary Table S3). Three studies by Soullane et al.,59 Geurtsen et al.61 and Patel et al.64 reported a positive association between GDM-complicated pregnancy and an 18%–6.7-fold increased risk of offspring developing NAFLD, averagely 6–18 years after birth in the Western population. On the contrary, three studies by Zeng et al.,60 Bellatorre et al.62 and Ayonrinde et al.63 reported a null association between maternal GDM and incidence of offspring NAFLD (Supplementary Table S3). In a British cross-sectional study, Patel et al.65 performed pathohistological examination of H&E stained liver slides on 81 stillborn and reported a much higher prevalence and severity of hepatic steatosis in stillborn born to mothers with a history of diabetes including GDM, compared with those without (78.8% vs. 16%, p < 0.001). Separately, a Pakistani clinical study66 performed an abdominal ultrasound on 200 patients (18–35 years old) with fatty liver and found 70% of them had maternal history of diabetes including GDM.

Meta-analysis of GDM and postpartum NAFLD development in mothers

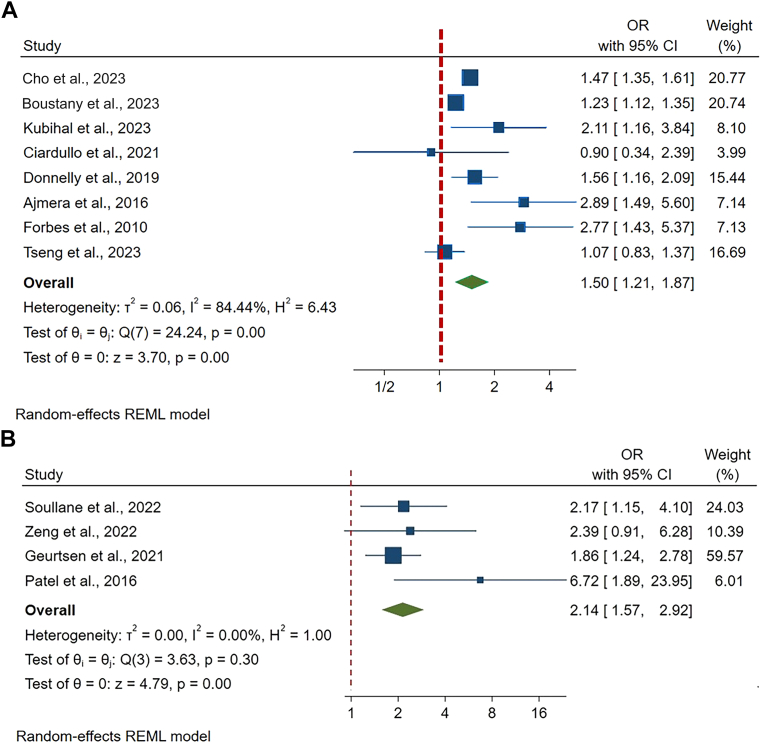

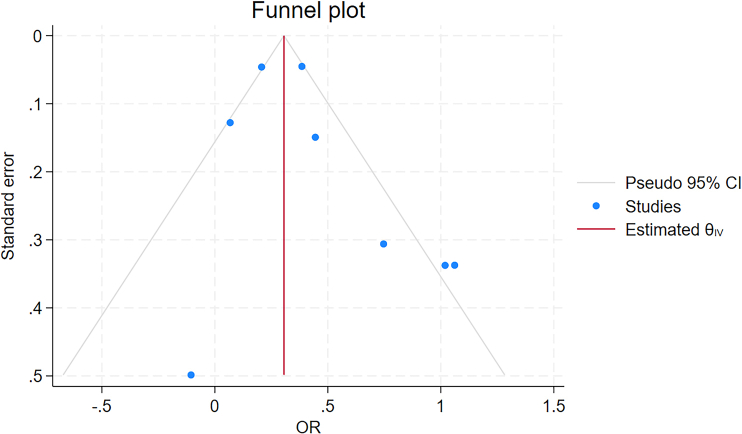

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the studies, including study population, location, follow-up years, pre-pregnancy BMI, sample size and ascertainment of GDM and NAFLD, and effect size with 95% CI. Even though statistical adjustments varied across the studies, most studies adjusted for maternal age, race/ethnicity, and BMI. Publications were weighted with different percentages when calculating overall effect size using factors including risk of publication bias and sample size. In meta-analysis conducted in eight studies, women with GDM showed an increased risk of developing NAFLD (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.21–1.87), after 16 months to 25 years of follow-up. The heterogeneity (I2) in the meta-analysis was 84.4% and Cochran's Q test p value was 0.001, which means heterogeneity is considered fairly high (Fig. 2A). Risk of publication bias was assessed using the Egger and Begg's tests and expressed in the funnel plot. Publication bias was not ascertained in both Egger's test (p = 0.08), Begg's test (p = 0.71), but in funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on maternal gestational diabetes mellitus and maternal non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) included for meta-analysis.

| Author (Year) | Study design, location | Race or ethnicity of population | Follow-up (Year) | Total samples (n) | Maternal age at index pregnancy in year, mean (SD) | Incidence rate (per 1000 person-year) | Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | GDM diagnosis and number (n cases) | NAFLD diagnosis and number (n cases) | Effect size (OR, RR, with 95% CI) | Adjustment | Grading score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tseng57 (2023) | Retrospective cohort, Taiwan | Asian | 5 | 358,055 | 31.06 (4.48) | 0.2 | Nil | Medical code N = 71,611 |

376 | HR: 1.07 (0.84, 1.37) | Age, cancer, parity, and endpoint T2D, aHTN, HL, CVDs, AMI, CKD, and PAOD. | 7 |

| Cho48 (2023) | Retrospective cohort, South Korea | Asian | 3.7 years (range 2.0–4.4) | 64,397 | GDM: 37.7 Non-GDM: 38.4 |

25 | GDM: 21.3 Non-GDM: 21.4 |

Self-reported N = 4683 |

Abdominal ultrasonography N = 6032 |

NAFLD: HR 1.46 95% CI: 1.33–1.59 |

Smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity level, BMI, history of HTN, history of CVD, lipid-lowering drug use, baseline age, center, examination year, education level, and age at first pregnancy | 8 |

| Boustany56 (2023) | Retrospective cohort, US | Mixed population, western majority | Range: 18–65 years | 70,632,640 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Medical record N = 167,510 |

Medical record N = 36,550 |

OR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.11–1.33 |

Race/ethnicity, obesity, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, T2D, PCOS and hypothyroidism | 7 |

| Kubihal54 (2021) | Prospective cohort, India | Asian | Median 16 months postpartum (IQR 9–38) | 309 | 30.57 (IQR: 29.82, 33.74) | 437 | Nil | IADPSG criteria N = 201 |

Abdominal ultrasonography with grading of hepatic steatosis severity; and Fibroscan with Controlled Attenuation Parameter ≥270 dB/m N = 180 |

OR 2.11; 95% CI: 1.16–3.85 |

Age, economic status, education, employment, number of live births, time since the index delivery, exclusive breast-feeding for ≥6 months, hyperlipidemia, HTN, metabolic syndrome, T2D, PCOS, history of GDM subclinical or overt hypothyroidism, smoking. | 5 |

| Ciardullo49 (2021) | Prospective cohort, US | Mixed population, western majority | ≥20 years | 1699 | GDM: At 1st birth: 23.4 (0.4) At last birth 28.5 (0.4) Non-GDM: At 1st birth: 24.4 (1.1) At last birth 31.3 (0.6) |

21 | Nil | Self-reported N = 144 |

Vibration-controlled transient elastography using Controlled Attenuation Parameter ≥274 dB/m N = 706 |

OR: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.34–2.40 | Age, BMI, race/ethnicity, GGT, T2D diagnosis, HBV infection, HCV infection, heavy alcohol consumption and platelet count. | 6 |

| Donnelly50 (2019) | Prospective cohort, Denmark | Mixed population, western majority | 9–16 years | 1226 | GDM: 30.5 (4.2) Non-GDM: 31.6 (4.5) |

Nil | GDM: 27.2 (5.6) Non-GDM: 22.8 (3.9) |

Medical code N = 361 |

Fatty Liver Index (FLI)-defined NAFLD ≥60 N = 174 |

RR: 1.47 95% CI: 1.15–1.87 |

Maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, parity, smoking in pregnancy, alcohol consumption in pregnancy, education level, family history of diabetes all at index pregnancy. | 8 |

| Ajmera47 (2016) | Prospective cohort, US | Mixed population, western majority | 25 years | 1115 | GDM: 26 (IQR 8) Non-GDM: 25 (IQR 6) |

3 | GDM: 23.8 (IQR 8.8) Non-GDM: 22.9 (IQR 6.2) |

Self-reported N = 124 |

Non-contrast abdominal CT scan using liver attenuation (LA) measurement ≤40 HU N = 75 |

OR: 2.89; 95% CI: 1.49–5.59 |

Age, baseline HOMA-IR, baseline TG, changes in BMI | 7 |

| Forbes52 (2011) | Retrospective cohort, UK | Mixed population, western majority | 6–7 years | 223 | Range: 20–45 | 42 | Nil | WHO 1999 guidelines N = 110 |

Ultrasound scan N = 61 |

OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 1.43–5.37 | Postpartum BMI | 5 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; NASH, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; OR, odd ratio; RR, relative ratio, HR, hazard ratio; IQR, inter-quartile range; FLI, fatty liver index; CI: confidence interval; T2D, type 2 diabetes; aHTN, arterial hypertension; HL, hyperlipidemia; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; PAOD, peripheral artery occlusive disease; US, United States; UK, United Kingdom; IADPSG, the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups; WHO, World Health Organization. FLI, fatty liver index.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis Results. Evidence of overall Odds Ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of maternal GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD (A) and offspring NAFLD (B), using unadjusted random-effects model. Heterogeneity was presented in both I2 (describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance) and T2 (reflecting the variance of the true effect sizes). Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; %, percentage.

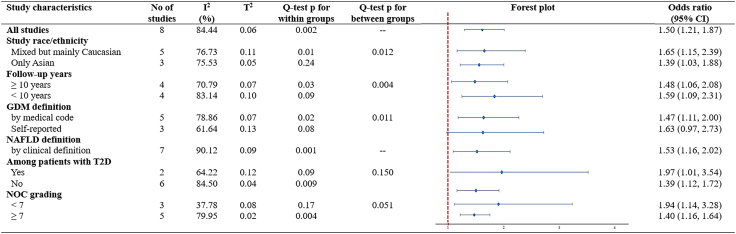

In subgroup analyses stratified by study characteristics, significant differences between subgroups were detected by study race/ethnicity (p = 0.01), follow-up years (p = 0.004), GDM definitions (p = 0.011), and quality of study (p = 0.051) (Fig. 3). Notably, the associations appeared to be more pronounced within Caucasian population, in studies with sample size less than 1000, those with follow-up duration less than 10 years, and in studies categorized as having moderate-to-high risk of bias (Fig. 3). Two out of eight studies reported a higher risk of NAFLD in women specifically with comorbidity of T2D (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.01–3.54), compared with women without specified comorbidity of T2D (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.12–1.72), even though the difference between groups did not reach a statistical significance (Fig. 3). Furthermore, subgroups analyses stratified by major confounders, significant differences between subgroups were detected by adjustment including maternal age (p = 0.002), maternal BMI (p = 0.002), socioeconomic status (p = 0.005), pregnancy complications (p = 0.002), comorbidity (p = 0.03) and lifestyle (p = 0.014), suggesting that these factors might statistically significantly modify the association between GDM and NAFLD (Supplementary Figure S2).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analyses on maternal GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD, stratified by study characteristics and adjustments. Evidence of overall Odds Ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of maternal GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD was reported in all subgroups, using unadjusted random-effects model. Heterogeneity was presented in both I2 (describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance) and T2 (reflecting the variance of the true effect sizes). Cochran's Q test is used to determine if there are differences of NAFLD within subgroups or between subgroups. p value < 0.10 for Q-test is considered significant. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; T2D, type 2 diabetes; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Meta-analysis of GDM and NAFLD development after delivery in offspring

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the studies, including study population, location, follow-up years, pre-pregnancy BMI, offspring BMI, ascertainment and sample size of GDM in mother and NAFLD in offspring, and effect size with 95% CI. Even though statistical adjustments varied across the studies, most studies adjusted for maternal age and offspring age. Publications were weighted with different percentages when calculating overall effect size using factors including risk of publication bias and sample size.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies on maternal gestational diabetes mellitus and offspring non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) included for meta-analysis.

| Author (Year) | Study design, location | Race or ethnicity of population | Follow-up (Year) | Total samples (n) | Maternal age at index pregnancy (year), (mean, SD) | Pre-pregnancy BMI at index pregnancy (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | GDM diagnosis and number (n case) | Incidence rate (per 1000 person-year) | Offspring age (year), (mean, SD) | Offspring BMI (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | Offspring NAFLD diagnosis and number (n case) | Effect size (OR/RR, with 95% CI) | Adjustment | Grading score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soullane59 (2022) | Prospective cohort, Canada | Mixed population Western majority | Range: 1–14 years | 5104 | Nil | Nil | Medical record N = 371 |

Nil | 6.7 (4.4) | Nil | Ultrasonography, liver function tests N = 104 |

OR 2.17 95% CI: 1.15–4.10 |

Maternal age at birth, child sex, birth order, maternal substance use, socioeconomic disadvantage, and period of birth | 7 |

| Zeng60 (2022) | Prospective cohort, China | Asian | 8 years (range: 7.83–8.17) | 430 maternal-child pairs | 29 (4.9) | 21.55 (3.59) | O&G Branch of Chinese Medical Association Guidelines N = 48 |

17 | 8 years old (7.83–8.17) | 15.89 (4.42) | Fibroscan with Controlled Attenuation Parameter ≥214.53 dB/m N = 60 | OR 2.39 95% CI: 0.91–6.29 |

Maternal age and nulliparity, offspring age, sex, and birth weight. | 8 |

| Geurtsen61 (2021) | Prospective cohort, The Netherlands | Mixed population Western majority | 10 years (mean 9.8 years, SD 0.4) | 1426 maternal-child European pairs | 31.7 (4.0) | Median 22.2 95% CI: 18.1, 34.3 |

Dutch Obstetrics Guidelines N = 15 |

2 | 9.8 (0.3) | Median 16.9; 95% CI: 14.0, 24.3 | MRI scanner, liver fat ≥5.0%. N = 25 |

OR 1.86 95% CI: 1.24–2.78 |

Child sex, child age, maternal education, child physical activity, maternal pp-BMI | 7 |

| Patel64 (2016) | Prospective cohort, UK | Mixed population Western majority | 17.8 years (range: 17–18) | 1215 | 29.5 (4.5) | 22.8 (3.7) | Medical record 114 (GDM + pre-existing diabetes + glycosuria during pregnancy) |

1.16 | 17.8 (0.4) | Nil | Liver ultrasound scans N = 25 |

OR 6.72 95% CI: 1.89–24.00 |

Offspring age at outcome, sex, maternal age, parity, maternal alcohol intake, highest household manual social class, maternal prepregnancy BMI, offspring birthweight for gestational age, offspring DXA-assessed fat mass, height and height squared at outcome | 7 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; OR, odd ratio; RR, relative ratio; CI: confidence interval; UK, United Kingdom.

Meta-analysis showed that offspring born to mothers with a GDM-complicated index pregnancy had a two-fold risk of developing NAFLD (OR 2.14, 95% CI: 1.57–2.92), after 1–17.8 years of follow-up. The heterogeneity (I2) in the meta-analysis was 0% and Cochran's Q test p value was 0.3042, which means heterogeneity is considered very low. The pooled result showed low heterogeneity across all four studies (Fig. 2B). Publication bias was not significant in both Egger's test and Begg's test (both p value > 0.05), but visually observed in funnel plot (Supplementary Figure S3). Due to the few publications, subgroup analysis was not successful in this topic.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we have compiled all available evidence pertaining to GDM and its effects on a greater incidence of adverse clinical liver outcomes in both mothers and offspring. Our findings demonstrated an overall 50% increase in the risk of postpartum NAFLD among mothers over a follow-up duration from 16 months to over 65 years after delivery, as well as an overall 2.14-fold increase in the risk of NAFLD development among offspring aged between 1 and 17.8 years.

Furthermore, the link between GDM and maternal NAFLD implicated from our subgroup analyses suggests that studies with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up durations, and a low risk of bias are more likely to yield reliable and precise estimates. Interestingly, adjustments for maternal BMI and comorbidities appeared to enhance the risk of maternal postpartum NAFLD. These outcomes emphasize the significance of conducting high-quality research and implementing comprehensive control measures for confounding variables, particularly focusing on factors such as BMI.

Recent evidence has proposed a series of potential pathophysiology underlying the shift from GDM to postpartum maternal NAFLD. Firstly, insulin resistance and the accumulation of liver fat are key factors. The foundation of both GDM and NAFLD rest upon the prolonged insulin resistance experienced from pregnancy to the postpartum period. A substantial proportion of women with GDM already contended with chronic insulin resistance.67,68 The additional insulin resistance triggered by pregnancy hormones exacerbates this condition, leading to an amplified overall insulin resistance during gestation.67,68 This heightened insulin resistance could prompt NAFLD by impeding the insulin-driven inhibition of lipolysis, resulting in an influx of free fatty acids transported to the liver. This cascade, in turn, prompts increased accumulation of hepatic fat, subsequently induces hepatic insulin resistance,69,70 and intensifies the generation and circulation of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA).71 Secondly, a body of evidence has suggested that women who have previously experienced GDM exhibit higher levels of liver fat while displaying diminished adiponectin concentrations. Diminished adiponectin levels have been linked to heightened inflammation in vivo, obesity and even lower in patients with hepatic steatosis.72 Along with disrupted levels of adipokines, the elevation of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1, IL-18, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) has also been observed to be parallel with increased levels of circulating ALT and AST in patients affected by NAFLD and NASH.73,74 The interplays amongst adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation could potentially prolong the duration of hyperinsulinemia from pregnancy to the postpartum phase.75 Consequently, within the context of a postpartum hyperglycemic state, the cumulative surge in inflammation and oxidative stress due to insulin resistance could potentially amplify lipogenesis, triglyceride synthesis, and the accumulation of liver fat.

It is worth mentioning that Mothers with a history of GDM confront a considerable seven-to-ten times heightened risk of developing T2D,76,77 underscoring the long-term metabolic repercussions of the condition. Beyond T2D, this population is predisposed to various metabolic disorders, encompassing central obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and an elevated lipid profile (e.g., increased levels of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, uric acid and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol).78 In fact, affected mothers exhibit a staggering six times risk of metabolic syndrome compared to their healthy counterparts, immediately after childbirth and persisting years postpartum.79,80 This heightened susceptibility underscores the enduring impact of GDM on metabolic health and highlights the need for long-term monitoring and intervention strategies in this population.

The influence of GDM on NAFLD can manifest as early as in infancy and extend to adolescence. In this context, we have undertaken an exploration of the potential pathogenic mechanisms that may underlie the development of NAFLD in offspring born to GDM-complicated pregnancies. To start, there is a possible mechanism that entails the impact of heightened maternal circulating fatty acid levels on the fetus during labour and childbirth. The elevated maternal circulating fatty acids due to maternal obesity and/or impaired glucose metabolism60 could permeate the placental barrier and reach the fetus during pregnancy. However, owing to the fetus’ relatively less developed subcutaneous fat storage, the surplus circulating fatty acids might be directed towards the fetal liver instead.81 Secondly, when excess glucose from the maternal circulation readily traverses the placenta through facilitated diffusion, the status of fetal hyperglycemia could prompt an escalation in insulin secretion from the fetal pancreatic islet cells, along with the obesity-like hypothalamic changes in the offspring, thereby predisposing them to future metabolic conditions like obesity as well as NAFLD.82,83 Subsequently, hyperinsulinemia in the fetus is compensated along with the existence of hyperglycemic condition, propelling accelerated fetal growth and the generation of adipose tissue, while simultaneously subjecting the fetal liver to oxidative stress.82 The ramifications of fetal hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia could have long-lasting consequences. Thirdly, several studies have established a link between GDM and alterations in the placenta. These GDM-induced modifications could lead to the development of a dysfunctional placenta, which in turn predisposes the offspring to an elevated risk of liver dysfunction and various other metabolic conditions including NAFLD.84 Evidence from placental samples obtained from term GDM offspring has revelated two critical findings: an increase in placental villus volume and villous immaturity, which indicates a reduced capacity for nutrient transfer from the placenta to the fetus85,86 and results in hypoxia and nutrient deficiency for the foetus.87 These combined factors significantly elevate the risk of future mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and NAFLD to the offspring.84,88

Offspring exposed to GDM-complicated pregnancies face elevated health risks beyond NAFLD. For example, they exhibit a five-fold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes89, 90, 91 and a 2.5–4 times higher likelihood of acquiring metabolic syndrome compared to their counterparts. This risk escalates with worsening antenatal glycemic control.92 Furthermore, antenatal GDM exposure exacerbates cardiovascular risk factors in offspring. A 40-year follow-up cohort study revealed a 30% increase in cardiovascular risk among children born to GDM mothers, with a higher incidence of early-onset cardiovascular disease.93 Additionally, GDM contributes slightly to childhood obesity rates, with an odds ratio of 1.41 observed at 6 years of follow-up.94 These findings underscore the multifaceted impact of GDM on offspring health, emphasizing the importance of early intervention and monitoring to mitigate long-term health risks.

The primary strength of this systematic review lies in its extensive analysis of research evidence regarding the association of GDM and NAFLD in both mothers and offspring. The robustness of our study is fortified by a meticulous search strategy, ensuring the thorough identification of all eligible studies, and subgroup analyses. However, the study is not without its limitations. Firstly, it's important to note that our paper exclusively incorporated pertinent papers procured from four distinct search engines, limited to English-language publications. This approach could potentially introduce information bias if pertinent content is present but published in languages other than English or not covered within the predetermined quartet of databases. Secondly, a notable limitation emerges from the significant heterogeneity observed across studies. This variance stems from differences in study populations, divergent follow-up durations, distinct protocols for data collection and screening methodologies, as well as variations in the diagnostic criteria for GDM and NAFLD. While our subgroup analyses were intended to investigate sources of heterogeneity, the limited sample sizes of the included studies may constrain the interpretation of our results. Thirdly, only Cho et al.48 explicitly excluded individuals with pre-existing NAFLD from their study analysis while the rest included for meta-analysis did not specify such exclusion criteria. The overall estimates of temporal relationship between GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD should be warranted by further cohorts. Lastly, it is important to note that with fewer than ten studies included in the meta-analyses for either mothers or offspring, the reliability of the Egger's and Begg's tests, along with the funnel plot interpretations, may be compromised due to potential bias.

Given the heightened susceptibility to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in both mothers and offspring of pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), it is prudent for healthcare practitioners in public health settings to incorporate routine liver function and imaging assessments as part of postpartum follow-up procedures. This should include blood tests and universal ultrasound scans for both mothers and offspring, especially within the first year following birth. Simultaneously, acknowledging the potential to mitigate the concept of “intrauterine epigenetic memory” through dietary adjustments and physical activity interventions during pregnancy, healthcare professionals should prioritize lifestyle recommendations and potentially medical interventions for mothers diagnosed with GDM. These interventions aim to improve maternal and offspring health outcomes, thereby reducing the risk of NAFLD and associated complications in the postpartum period and beyond.95, 96, 97

In summary, women affected by GDM are more susceptible to NAFLD compared to their counterparts without GDM. Furthermore, offspring born to mothers with GDM face an increased risk of NAFLD in their later years. Recognizing the potential to alleviate the concept of “intrauterine epigenetic memory” through dietary adjustments and physical activity interventions during pregnancy, healthcare professionals should prioritise lifestyle recommendations and potentially medical interventions for mothers diagnosed with GDM during gestation.

Contributors

L.-J.L. conceived the idea of the study; R.X.F., J.J.M. & L.-J.L. screened the studies and extracted the data; R.D. carried out the statistical analysis; L.-J.L. supervised the analysis. R.X.F., J.J.M. & L.-J.L. interpreted the findings and drafted the manuscript. G.B.B.G., C.Z. and L.-J.L. edited and revised the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for final submission. R.X.F., J.J.M., R.D & L.-J.L have verified the underlying data. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. L.-J.L. is guarantor. L.-J.L accepts full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Data sharing statement

No additional data available, all data are in the manuscript and supplementary information files.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests, or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

The research is supported by the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102609.

Contributor Information

Cuilin Zhang, Email: obgzc@nus.edu.sg.

Ling-Jun Li, Email: obgllj@nus.edu.sg.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure S1.

Funnel plot regarding MA of maternal GDM and maternal NAFLD.

Supplementary Figure S2.

Subgroup analysis of study adjustment in meta-analysis results of association between GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD. Evidence of overall Odds Ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of maternal GDM and maternal postpartum NAFLD was reported in all subgroups, using unadjusted random-effects model. Heterogeneity was presented in both I2 (describing the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance) and T2 (reflecting the variance of the true effect sizes). Cochran's Q test is used to determine if there are differences of NAFLD within subgroups or between subgroups. P value < 0.10 for Q-test is considered significant. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index, HDP, hypertensive disorder during pregnancy; HTN, hypertension; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Figure S3.

Funnel plot regarding MA of maternal GDM and offspring NAFLD.

References

- 1.American Diabetes A 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S13–S27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McIntyre H.D., Catalano P., Zhang C., Desoye G., Mathiesen E.R., Damm P. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):47. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenzo-Almoros A., Hang T., Peiro C., et al. Predictive and diagnostic biomarkers for gestational diabetes and its associated metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0935-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters R.K., Kjos S.L., Xiang A., Buchanan T.A. Long-term diabetogenic effect of single pregnancy in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Lancet. 1996;347(8996):227–230. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang C., Rawal S., Chong Y.S. Risk factors for gestational diabetes: is prevention possible? Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1385–1390. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3979-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rayanagoudar G., Hashi A.A., Zamora J., Khan K.S., Hitman G.A., Thangaratinam S. Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1403–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3927-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Retnakaran R., Shah B.R. Mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2009;181(6-7):371–376. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer C.K., Campbell S., Retnakaran R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2019;62(6):905–914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-019-4840-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tam W.H., Ma R.C.W., Ozaki R., et al. In utero exposure to maternal hyperglycemia increases childhood cardiometabolic risk in offspring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(5):679–686. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damm P., Houshmand-Oeregaard A., Kelstrup L., Lauenborg J., Mathiesen E.R., Clausen T.D. Gestational diabetes mellitus and long-term consequences for mother and offspring: a view from Denmark. Diabetologia. 2016;59(7):1396–1399. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-3985-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Bernardo S., Mivelaz Y., Epure A.M., et al. Assessing the consequences of gestational diabetes mellitus on offspring's cardiovascular health: MySweetHeart Cohort study protocol, Switzerland. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godfrey K.M., Reynolds R.M., Prescott S.L., et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(1):53–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30107-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puhkala J., Raitanen J., Kolu P., Tuominen P., Husu P., Luoto R. Metabolic syndrome in Finnish women 7 years after a gestational diabetes prevention trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clausen T.D., Mathiesen E.R., Hansen T., et al. High prevalence of type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes in adult offspring of women with gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes: the role of intrauterine hyperglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):340–346. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rager S.L., Zeng M.Y. The gut-liver Axis in pediatric liver health and disease. Microorganisms. 2023;11(3):597. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms11030597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eslam M., Sanyal A.J., George J., International Consensus P MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1999–2014.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinella M.E., Lazarus J.V., Ratziu V., et al. A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J Hepatol. 2023;79(3):E93–E94. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(16):1221–1231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankowski R., Kobierecki M., Wittczak A., et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and metabolic repercussions: the vicious cycle and its interplay with inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9677. doi: 10.3390/ijms24119677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le M.H., Yeo Y.H., Li X., et al. 2019 Global NAFLD prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(12):2809–2817.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eslam M., Alkhouri N., Vajro P., et al. Defining paediatric metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(10):864–873. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell E.E., Wong V.W., Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet. 2021;397(10290):2212–2224. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32511-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buzzetti E., Pinzani M., Tsochatzis E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Metabolism. 2016;65(8):1038–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Byrne C.D., Targher G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol. 2015;62(1 Suppl):S47–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldstein A.E., Charatcharoenwitthaya P., Treeprasertsuk S., Benson J.T., Enders F.B., Angulo P. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut. 2009;58(11):1538–1544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.171280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Molleston J.P., White F., Teckman J., Fitzgerald J.F. Obese children with steatohepatitis can develop cirrhosis in childhood. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(9):2460–2462. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A-Kader H.H., Henderson J., Vanhoesen K., Ghishan F., Bhattacharyya A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a single center experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):799–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann J.P., Vreugdenhil A., Socha P., et al. European paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease registry (EU-PNAFLD): design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;75:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.International Association of D., Pregnancy Study Groups Consensus P., Metzger B.E., et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):676–682. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alberti K.G., Zimmet P.Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15(7):539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. National diabetes data group. Diabetes. 1979;28(12):1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao Y.T., Xiang L.L., Qi F., Zhang Y.J., Chen Y., Zhou X.Q. Accuracy of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) for assessing steatosis and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;51 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 35.NOSC coding manual. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/nos_manual.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2023.

- 36.Shor E., Roelfs D., Vang Z.M. The "Hispanic mortality paradox" revisited: meta-analysis and meta-regression of life-course differentials in Latin American and Caribbean immigrants' mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2017;186:20–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J., Yu K.F. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280(19):1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riley R.D., Higgins J.P., Deeks J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342:d549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borenstein M., Hedges L.V., Higgins J.P., Rothstein H.R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ades A.E., Lu G., Higgins J.P. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making. 2005;25(6):646–654. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05282643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoaglin D.C. Misunderstandings about Q and ‘Cochran's Q test' in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2016;35(4):485–495. doi: 10.1002/sim.6632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie W., Wang Y., Xiao S., Qiu L., Yu Y., Zhang Z. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus with overall and type specific cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters J.L., Sutton A.J., Jones D.R., Abrams K.R., Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(6):676–680. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M., Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Begg C.B., Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ajmera V.H., Gunderson E.P., VanWagner L.B., Lewis C.E., Carr J.J., Terrault N.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus is strongly associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(5):658–664. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cho Y., Chang Y., Ryu S., Kim C., Wild S.H., Byrne C.D. History of gestational diabetes and incident nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the kangbuk samsung health study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118(11):1980–1988. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ciardullo S., Bianconi E., Zerbini F., Perseghin G. Current type 2 diabetes, rather than previous gestational diabetes, is associated with liver disease in U.S. Women. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;177 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Donnelly S.R., Hinkle S.N., Rawal S., et al. Prospective study of gestational diabetes and fatty liver scores 9 to 16 years after pregnancy. J Diabetes. 2019;11(11):895–905. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foghsgaard S., Andreasen C., Vedtofte L., et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is prevalent in women with prior gestational diabetes mellitus and independently associated with insulin resistance and waist circumference. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):109–116. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forbes S., Taylor-Robinson S.D., Patel N., Allan P., Walker B.R., Johnston D.G. Increased prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in European women with a history of gestational diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54(3):641–647. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussain F.N., Rosenbluth E., Feldman K.M., et al. Transient elastography and controlled attenuation parameter to evaluate hepatic steatosis and liver stiffness in postpartum patients. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023;36(1) doi: 10.1080/14767058.2023.2190838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kubihal S., Gupta Y., Shalimar, et al. Prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and factors associated with it in Indian women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12(5):877–885. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mehmood S., Margolis M., Ye C., et al. Hepatic fat and glucose tolerance in women with recent gestational diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2018;6(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2018-000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boustany A., Onwuzo S., Zeid H.K.A., et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis is independently associated with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;38(6):984–988. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tseng S.T., Lee M.C., Tsai Y.T., et al. Risks after gestational diabetes mellitus in Taiwanese women: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Biomedicines. 2023;11(8):2120. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11082120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Retnakaran R., Luo J., Shah B.R. Gestational diabetes in young women predicts future risk of serious liver disease. Diabetologia. 2019;62(2):306–310. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4775-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soullane S., Willems P., Lee G.E., Auger N. Early life programming of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children. Early Hum Dev. 2022;168 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2022.105578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zeng J., Shen F., Zou Z.Y., et al. Association of maternal obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus with overweight/obesity and fatty liver risk in offspring. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(16):1681–1691. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v28.i16.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geurtsen M.L., Wahab R.J., Felix J.F., Gaillard R., Jaddoe V.W.V. Maternal early-pregnancy glucose concentrations and liver fat among school-age children. Hepatology. 2021;74(4):1902–1913. doi: 10.1002/hep.31910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bellatorre A., Scherzinger A., Stamm E., Martinez M., Ringham B., Dabelea D. Fetal overnutrition and adolescent hepatic fat fraction: the exploring perinatal outcomes in children study. J Pediatr. 2018;192:165–170.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ayonrinde O.T., Adams L.A., Mori T.A., et al. Sex differences between parental pregnancy characteristics and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):108–122. doi: 10.1002/hep.29347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patel S., Lawlor D.A., Callaway M., Macdonald-Wallis C., Sattar N., Fraser A. Association of maternal diabetes/glycosuria and pre-pregnancy body mass index with offspring indicators of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:47. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0585-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel K.R., White F.V., Deutsch G.H. Hepatic steatosis is prevalent in stillborns delivered to women with diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60(2):152–158. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ahmad S.J., Ahmad M.W. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease: association with maternal diabetes. PJMHS. 2012;6 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Homko C., Sivan E., Chen X., Reece E.A., Boden G. Insulin secretion during and after pregnancy in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):568–573. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.2.7137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kautzky-Willer A., Prager R., Waldhausl W., et al. Pronounced insulin resistance and inadequate beta-cell secretion characterize lean gestational diabetes during and after pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(11):1717–1723. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.11.1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bugianesi E., Gastaldelli A., Vanni E., et al. Insulin resistance in non-diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: sites and mechanisms. Diabetologia. 2005;48(4):634–642. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chalasani N., Deeg M.A., Persohn S., Crabb D.W. Metabolic and anthropometric evaluation of insulin resistance in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(8):1849–1855. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donnelly K.L., Smith C.I., Schwarzenberg S.J., Jessurun J., Boldt M.D., Parks E.J. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buechler C., Wanninger J., Neumeier M. Adiponectin, a key adipokine in obesity related liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(23):2801–2811. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stojsavljevic S., Gomercic Palcic M., Virovic Jukic L., Smircic Duvnjak L., Duvnjak M. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the key mediators in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(48):18070–18091. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tasci I., Dogru T., Ercin C.N., Erdem G., Sonmez A. Adipokines and cytokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(2):266–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramachandrayya S.A., D'Cunha P., Rebeiro C. Maternal circulating levels of Adipocytokines and insulin resistance as predictors of gestational diabetes mellitus: preliminary findings of a longitudinal descriptive study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2020;19(2):1447–1452. doi: 10.1007/s40200-020-00672-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moon J.H., Jang H.C. Gestational diabetes mellitus: diagnostic approaches and maternal-offspring complications. Diabetes Metab J. 2022;46(1):3–14. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vounzoulaki E., Khunti K., Abner S.C., Tan B.K., Davies M.J., Gillies C.L. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Di Cianni G., Lencioni C., Volpe L., et al. C-reactive protein and metabolic syndrome in women with previous gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2007;23(2):135–140. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lauenborg J., Mathiesen E., Hansen T., et al. The prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a Danish population of women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus is three-fold higher than in the general population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):4004–4010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ghomian N., Vahed S.H.M., Firouz S., Yaghoubi M.A., Mohebbi M., Sahebkar A. The efficacy of metformin compared with insulin in regulating blood glucose levels during gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized clinical trial. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(4):4695–4701. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Brumbaugh D.E., Tearse P., Cree-Green M., et al. Intrahepatic fat is increased in the neonatal offspring of obese women with gestational diabetes. J Pediatr. 2013;162(5):930–936.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dalrymple K.V., El-Heis S., Godfrey K.M. Maternal weight and gestational diabetes impacts on child health. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2022;25(3):203–208. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Page K.A., Luo S., Wang X., et al. Children exposed to maternal obesity or gestational diabetes mellitus during early fetal development have hypothalamic alterations that predict future weight gain. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1473–1480. doi: 10.2337/dc18-2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wesolowski S.R., Kasmi K.C., Jonscher K.R., Friedman J.E. Developmental origins of NAFLD: a womb with a clue. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(2):81–96. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Higgins M., Felle P., Mooney E.E., Bannigan J., McAuliffe F.M. Stereology of the placenta in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Placenta. 2011;32(8):564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Taricco E., Radaelli T., Rossi G., et al. Effects of gestational diabetes on fetal oxygen and glucose levels in vivo. BJOG. 2009;116(13):1729–1735. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li Y., Hadden C., Singh P., et al. GDM-associated insulin deficiency hinders the dissociation of SERT from ERp44 and down-regulates placental 5-HT uptake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(52):E5697–E5705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416675112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rueda-Clausen C.F., Dolinsky V.W., Morton J.S., Proctor S.D., Dyck J.R., Davidge S.T. Hypoxia-induced intrauterine growth restriction increases the susceptibility of rats to high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):507–516. doi: 10.2337/db10-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dabelea D., Mayer-Davis E.J., Lamichhane A.P., et al. Association of intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes and obesity with type 2 diabetes in youth: the SEARCH Case-Control Study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):1422–1426. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sheiner E. Gestational diabetes mellitus: long-term consequences for the mother and child grand challenge: how to move on towards secondary prevention? Front Clin Diabetes Healthc. 2020;1 doi: 10.3389/fcdhc.2020.546256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Holder T., Giannini C., Santoro N., et al. A low disposition index in adolescent offspring of mothers with gestational diabetes: a risk marker for the development of impaired glucose tolerance in youth. Diabetologia. 2014;57(11):2413–2420. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Clausen T.D., Mathiesen E.R., Hansen T., et al. Overweight and the metabolic syndrome in adult offspring of women with diet-treated gestational diabetes mellitus or type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(7):2464–2470. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yu Y., Arah O.A., Liew Z., et al. Maternal diabetes during pregnancy and early onset of cardiovascular disease in offspring: population based cohort study with 40 years of follow-up. BMJ. 2019;367 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li W., Wang L., Liu H., et al. Maternal gestational diabetes and childhood adiposity risk from 6 to 8 years of age. Int J Obes (Lond) 2023;48(3):414–422. doi: 10.1038/s41366-023-01441-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Antoun E., Kitaba N.T., Titcombe P., et al. Maternal dysglycaemia, changes in the infant's epigenome modified with a diet and physical activity intervention in pregnancy: Secondary analysis of a randomised control trial. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hagstrom H., Simon T.G., Roelstraete B., Stephansson O., Soderling J., Ludvigsson J.F. Maternal obesity increases the risk and severity of NAFLD in offspring. J Hepatol. 2021;75(5):1042–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thompson M.D. Developmental programming of NAFLD by parental obesity. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4(10):1392–1403. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.