SUMMARY

The ability to optically stimulate and inhibit neurons has revolutionized neuroscience research. Here, we present a direct, potent, user-friendly chemical approach for optically silencing neurons. We have rendered saxitoxin (STX), a naturally-occurring paralytic agent, transiently inert through chemical protection with a previously undisclosed nitrobenzyl-derived photocleavable group. Exposing the caged toxin, STX-bpc, to a brief (5 ms) pulse of light effects rapid release of a potent STX derivative and transient, spatially precise blockade of voltage-gated sodium channels (NaVs). We demonstrate the efficacy of STX-bpc for parametrically manipulating action potentials in mammalian neurons and brain slice. Additionally, we show the effectiveness of this reagent for silencing neural activity by dissecting sensory-evoked swimming in larval zebrafish. Photo-uncaging of STX-bpc is a straightforward method for non-invasive, reversible, spatiotemporally precise neural silencing without the need for genetic access, thus removing barriers for comparative research.

eTOC

Elleman et al. designed and validated a photocaged small molecule toxin, STX-bpc, for rapid and precise in vitro and in vivo block of voltage-gated sodium channels and action potentials. Requiring neither specialized equipment nor genetic engineering, STX-bpc complements available optogenetic methods for manipulating electrical activity, cellular communication, and behavior.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

A desire to understand how information is processed in the nervous system has motivated the development of methods for real-time, spatiotemporal manipulation of neuronal activity. An array of technologies1,2 now exist for controlling and characterizing the function of different brain regions, circuits, and cell types; none, however, act directly on voltage-gated sodium (NaV) channels, the proteins responsible for action potential (AP) generation and propagation. Instead, methods like optogenetics3,4 rely on the expression of exogenous ion channels that constructively (e.g., ChR2)5 or destructively (e.g., eNpHR3.0)6 interfere with endogenous currents to produce a net change in electrical output. Alternatively, optochemical approaches for modulating electrical signaling rely on selective, small molecules that undergo photo-deprotection or photo-isomerization upon light exposure. The majority of these reagents target ligand-gated channels (e.g., MNI-caged-l-glutamate7 vs. AMPA/NMDA receptors); or voltage-gated (e.g., RuBi-4-aminopyridine8 vs. KV1 and KV3) or leak (e.g., MAQ vs. TREK-1)9 potassium channels. In this report, we describe an alternative tool for manipulating APs both in vitro and in vivo that requires no genetic manipulation and directly targets endogenous NaVs to block AP initiation. Herein, we describe the design, optimization, and validation of a broadly applicable small molecule reagent (STX-bpc) for precise, light-mediated NaV inhibition and AP silencing.

The control of endogenous sodium currents requires a modulator with high efficacy and specificity towards neuronal NaV isoforms. Saxitoxin is a potent inhibitor of NaVs that acts by binding to the outer mouth of the channel pore, just above the selectivity filter, to occlude ion passage into cells.10,11 Characteristics that favor STX as opposed to other NaV inhibitors12 for NaV targeting include: (1) its high potency against all channel conformational states (open, closed, inactive) such that binding occurs independently of stimulus; (2) its fast rate of association (kon ~ 106 M−1 s−1),13 enabling rapid block; and (3) its extracellular binding site, which allows for complete, reversible inhibition of channels. Additionally, saxitoxin is potent against most vertebrate14 and insect15,16 neuronal and cardiovascular NaVs. In mammals, STX has nanomolar affinity for seven of nine NaV subtypes (NaV1.1–1.7), including all NaVs expressed in the central nervous system.12, 17 We therefore anticipated that modification of STX with a destabilizing, photocleavable protecting group would yield a small molecule tool that is completely inert upon application to cells (and tissue) and rapidly uncaged upon exposure to light.

In this report, we demonstrate the utility of a photocaged saxitoxin, STX-bpc, for both tuning electrical excitability and achieving complete AP block with focal precision in dissociated rat neurons, in mouse cortical brain slice, and in larval zebrafish. We further illustrate the practicality of this technology as an alternative to optogenetic inhibition and for the targeted manipulation of locomotor behaviors. Given its efficacy across cell, tissue, and live organism absent any genetic manipulation, STX-bpc is a valuable complement to available optogenetic methods for spatiotemporal modulation of electrical signaling.

DESIGN

Design of Photocaged Saxitoxin

We previously described the development of coumarin-caged saxitoxins (e.g., STX-eac), providing proof-of-principle that brief exposure of these compounds to light can block AP firing and slow the propagation of compound action potentials along axon fiber tracks.18 The utility of STX-eac for neural control, however, is limited by: (1) a small operating window of STX-eac solution concentrations (the result of a ~20-fold change in IC50 between caged and uncaged toxin), which limits the degree to which NaV block can be fine-tuned; and (2) the need to deliver high-powered UV light to promote photocleavage, raising concerns of phototoxicity and tissue heating, particularly in cases of prolonged neuronal silencing, when long-duration light exposure may be required. Additional optimization of this reagent was hampered by the coumarin protecting group, as derivatization is limited and can reduce the efficiency of photocleavage.18,19 We thus pursued alternative photocage designs.

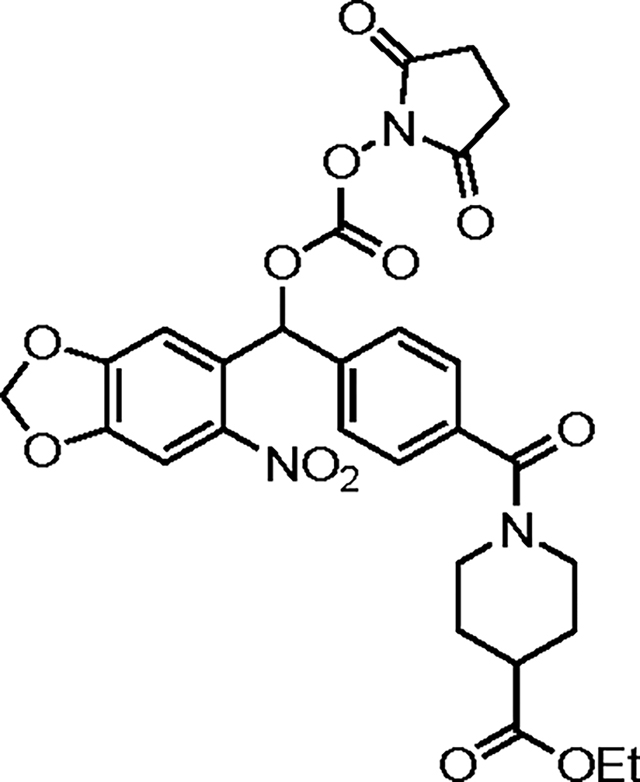

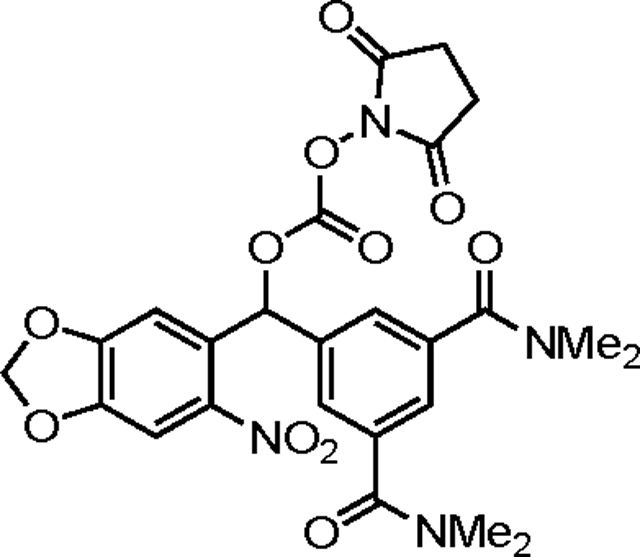

To improve the potency differential between caged and uncaged STX, we identified a photocleavable protecting group, [methyl-2-nitropiperonyl-oxy]carbonyl (MeNPOC, Figure 1A), 20, 21 amenable to chemical modifications including increase of its steric size and introduction of anionic units to destabilize toxin binding to the electronegative NaV pore.10,11 Replacement of the methyl moiety in MeNPOC with an electron-deficient group was expected to substantially improve uncaging efficiency, as demonstrated by the ~100-fold increase in quantum yield for the analogous CF3-modified cage.22,23 To maximize uncaging efficiency while minimizing the affinity of the photocaged STX for NaV, we replaced the Me-substituent in MeNPOC with a sterically large and/or negatively charged aryl amide, aryl ester, or aryl carboxylate group, thus affording a small collection of electron-deficient nitrobenzyl photocages [Hammett σ-constants(para): 0.36, CONHMe; 0.45, COOMe; 0.45, COOH; vs. 0.54, CF3].24

Figure 1: Optimized photocaged toxin enables precise control of rNaV1.2 current.

(A) MeNPOC (3,4-(methylenedioxy)-6-nitrophenylethoxycarbonyl) photo-protecting group. (B) Scheme depicting generalized synthesis and uncaging of photocaged STXs. a, i-PrMgCl•LiCl then 6-nitropiperonal (Ar = aryl); b, N,N’-disuccinimidyl carbonate, Et3N; c, saxitoxin-ethylamine 1; details are available in the Extended Data. Purple dashed line depicts location of photocleavage. (C) Generation 1 and 2 photocaged STXs. R = allyl. (D) Electrophysiological characterization of Generation 1 photocaged STXs against NaV1.2 CHO. IC50s, Hill coefficients: 1 = 14.4 ± 0.3 nM, −0.94 ± 0.02 (n = 6–7); 2 = 17.3 ± 0.7 nM, −1.17 ± 0.05 (n = 6–7); 3 = 59.8 ± 3.3 nM, −1.35 ± 0.10 (n = 3); 4 = 132.1 ± 7.3 nM, −1.35 ± 0.10 (n = 6). (E) Electrophysiological characterization of Generation 2 photocaged STXs against NaV1.2 CHO. IC50s, Hill Coefficients: 1 = 14.4 ± 0.3 nM, −0.94 ± 0.02 (n = 6–7); 8 = 67.6 ± 4.9 nM, −1.13 ± 0.09 (n = 4); 9 = 67.6 ± 3.6 nM, −1.23 ± 0.08 (n = 4–5); 10 = 507.2 ± 39.0 nM, −1.38 ± 0.15 (n = 3–4); 11 = 211.3 ± 25.7 nM, −0.93 ± 0.12 (n = 5–9); 12 = 1024.9 ± 38.6 nM, −1.01 ± 0.04 (n = 4–5); 13 = 3919.4 ± 172.6 nM, −1.02 ± 0.05 (n = 5–7). (F) Uncaging of 200 nM 13 against NaV1.2 CHO. Traces collected in the order: Initial, 200 nM 13, 0 s, 2 s, 4 s. Laser applied immediately prior to 0 s trace. Currents observed at 4 s used to calculate uncaging data described in (G). (G) Electrophysiological characterization and laser uncaging of 13 against NaV1.2 CHO. Apparent IC50s, Hill Coefficients: 1 = 14.4 ± 0.3 nM, −0.94 ± 0.02 (n = 6–7); 13 = 3919.4 ± 172.6 nM, −1.02 ± 0.05 (n = 5–7); 13 uncaged with 5 ms laser = 51.0 ± 1.9 nM, −0.98 ± 0.03 (n = 5–7); 13 uncaged with 5 × 5 ms laser = 21.3 ± 0.7 nM, −0.84 ± 0.02 (n = 5–7). Potency window highlighted in grey. See also Figures S1–S3, Tables S1–S2.

RESULTS

Synthesis and Optimization of Photocaged STXs

Caged compounds were readily prepared by 1,2-addition of the appropriate aryl Grignard reagent to 6-nitropiperonal and subsequent conjugation of the corresponding N-hydroxysuccinimide ester to STX ethylamine 125,26 (Figure 1B). [See supplemental data for full synthesis and characterization.] Photocaged STXs were then screened for potency against NaV1.2 stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with uncaging elicited by 5 ms pulses of 130 mW, 355 nm light. For clarity of discussion, caged STXs have been divided into two groups: Generation 1, comprising the ‘base model’ STX MeNPOC, 2, as well as amide-modified photocaged derivatives of varying steric bulk and electronic substitution (3–7); and Generation 2, composed of carboxylic acid-modified (i.e., anionic) structures (11, 12, 13) and their uncharged, allyl ester counterparts (8, 9, 10) (Figure 1C, Figure S1).

Examination of Generation 1 photocaged STXs revealed that steric substitution alone was insufficient to effectively destabilize toxin binding. The simplest construct, STX MeNPOC 2, was nearly equipotent to the uncaged inhibitor 1 (IC50: 17.3 nM vs. 14.4 nM; Figure 1D, Figure S2A) despite a seventy percent increase in molecular mass (582 vs. 301 Da). Whereas other, sterically larger derivatives diminished the potency of the caged toxin (IC50: 4 > 3 > 2, 132.1 nM > 58.9 nM > 17.3 nM; Figure 1D, Figure S3A–C), at best, only a nine-fold increase in the IC50 value compared to 1 could be obtained (IC50: 4 ~ 5 ~ 6 ~ 7, 132.1 nM ~ 114.2 nM ~ 128.1 nM ~ 121.9 nM; Figure 1D, Figure S2C–F, Table S1).

Among Generation 2 photocaged STXs, we found carboxylate-substituted structures (11, 12, 13) to be fifteen-fold less potent than analogous allyl esters (8, 9, 10, respectively), thus establishing the importance of anionic charge incorporation to destabilize binding of the caged compound (Figure 1E, Figure S2). Steric bulk also decreased affinity of the caged inhibitor for NaVs, as bis-piperidine carboxylate 13 (STX-bpc) is approximately four-fold less potent than bis-carboxylate 12 (IC50: 13, 3.9 μM vs. 12, 1.0 μM; also compare compounds 10, 0.5 μM vs. 9, 0.07 μM). STX-bpc was ultimately selected as the optimal probe for subsequent validation studies (vide infra).

All anionic photocaged STXs are photo-deprotected with unexpectedly high efficiency, particularly compared to the equivalent allyl ester derivatives (Figure 1F, 1G, Figure S2). Upon application of 5 × 5 ms pulses of 355 nm light, the apparent potency of esters 8–10 is minimally altered (e.g., IC50 ratio caged vs. uncaged: 8, 1.5; 9, 1.6; 10, 2.4; Table S2). In contrast, carboxylates 11–13 uncage almost completely under the same protocol, with post-exposure potencies approaching that of the parent compound 1 (IC50 following 5 × 5 ms pulses of 355 nm light: 11, 27.1 nM; 12, 25.1 nM; 13, 21.3 nM vs. IC50 1, 14.4 nM). Carboxylate incorporation thus dramatically improves uncaging efficiency, as photo-release of the ‘base model’ photocaged toxin 2 does not occur under the same photolysis conditions (Figure S2A, quantum yield for this protecting group is estimated at ϕ=0.007527). Why carboxylate substitution so profoundly enhances photocleavage is unclear, as the absorbance spectra of photocaged STXs 11–13 are unchanged from that of 2 (Figure S3A).

STX-bpc 13 is over 270-fold less potent than the parent compound 1 (IC50 = 3.9 μM vs. 14.4 nM; Figure 1E) and uncages rapidly upon application of 355 nm light (Figure 1F). The large concentration window over which this caged toxin may be employed (Figure 1G, grey) enables tuning of NaV current amplitude, as [STX-bpc] ≤ 500 nM blocks ≤ 10% of channels prior to uncaging, but as many as 90% following deprotection. As the concentration of STX-bpc can be varied, so too can the time constant (τ) for NaV block. At 200 nM STX-bpc, toxin release and inhibition of channels occurs with a τ = 1.0 ± 0.1 seconds (Figure S3B–C); at 500 nM 13, this value decreases (τ = 0.7 ± 0.07 seconds). Focal uncaging of STX-bpc thus precisely modulates NaV current, allowing the speed and degree of NaV block to be fine-tuned through changes in STX-bpc concentration, light intensity, and exposure duration.

NaV Block in Rat Dissociated Hippocampal Neurons

The advantageous properties of STX-bpc against NaV1.2 (CHO cells) are evident in experiments with embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. In electrophysiology recordings with dissociated neuronal cells, STX-bpc has an IC50 = 5.2 μM, 370-fold greater than that of 1 (14.1 nM; Figure 2A, 2B).18 Uncaging proceeds rapidly (τ = 1.6 seconds at 200 nM STX-bpc) and channel block extends for tens of seconds prior to wash-off (Figure 2A, Figure S6). A single 5 ms laser pulse releases sufficient concentrations of 1 to give an apparent IC50 = 87.6 nM. Accordingly, the magnitude of NaV currents in these cells can be modulated across a large range (e.g., 25% block of peak current following uncaging of 20 nM STX-bpc; 81% block of peak current upon uncaging 500 nM STX-bpc).

Figure 2: Uncaging of 13 rapidly blocks action potential propagation in dissociated embryonic hippocampal neurons.

(A) Uncaging of 100 nM 13. Traces collected in the order: Initial, 100 nM 13, 0 s, 2 s, etc. Laser applied immediately prior to 0 s trace. Currents observed at 10 s used to calculate uncaging data described in (B). (B) Electrophysiological characterization of 13. Apparent IC50s, Hill coefficients: 1 = 14.1 ± 0.8 nM, −0.86 ± 0.04 (n = 4–5); 13 = 5210.0 ± 409.1 nM, −0.88 ± 0.06 (n = 5–6); 13 uncaged with 5 ms laser = 87.6 ± 6.8 nM, −0.78 ± 0.05 (n = 5). (C) Representative traces depicting initial (I), laser applied (L), 200 nM 13 applied (T), 200 nM 13 and laser applied (TL), and recovered (R) after wash-off AP trains evoked by 500 ms, 50–150 pA current injections. Data taken from replicate current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). (D) Representative phase plot depicting application and uncaging of 100 nM 13. Calculated from first AP in current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). (E) Heat map summary of AP firing rate after application and uncaging of three different concentrations of 13 (100 nM, 200 nM, 500 nM) color-coded by number of action potentials per step (four replicate current steps at 0.25 Hz per condition). Equilibrated normalized AP firing rate (i.e., over current steps 2–4) compared below (n = 7–8,*p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction). Full statistical analysis is provided in Table S3. See also Figure S4.

Because uncaging proceeds efficiently, AP trains in neurons are abrogated using low concentrations of STX-bpc (e.g., 200 nM, Figure 2C). Application of 100–500 nM STX-bpc to hippocampal cells gives no observable changes in action potential shapes or firing frequencies (Figure 2D–E, Figure S4, Table S3). Photolysis of STX-bpc, however, decreases AP firing rate in a concentration-dependent manner (remaining percent of initial firing rate: 100 nM, 33%; 200 nM, 14%; 500 nM, < 1%) with uncaging of 500 nM STX-bpc (i.e., 81% peak Na+ current inhibition) blocking all APs (Figure 2E, Table S3). Photolysis of 100–200 nM STX-bpc also alters action potential shape (Figure 2C, Figure S4A), as uncaging of 200 nM STX-bpc reduces AP amplitude by 17% (p = 0.02) and shifts firing threshold to more positive potentials by approximately 12 mV (p = 0.14) (Figure S4B, S4D)—results in accordance with a decrease in the number of functional NaVs. 28 The characteristic kink at threshold voltage in the AP phase plot, ascribed to cooperativity among NaVs29 or AP initiation at the distal axon initial segment,30 disappears upon uncaging STX-bpc, also consistent with a reduction in functional NaV density (Figure S4A, S4F). Parameters describing the velocity and acceleration of AP rise similarly decrease upon uncaging STX-bpc, with the maximal rate of rise dropping by 54% (p = 0.03) and acceleration by 58% (p = 0.002; Figure S4C, S4G). AP firing recovers fully upon toxin wash-off at all concentrations (Figure 2C, Figure S4). Collectively, these data demonstrate that photo-deprotection of STX-bpc can be used to precisely tune APs in hippocampal neurons through the rapid and selective block of NaVs.

Electrical Silencing in Rat Dissociated Dorsal Root Ganglia

As with hippocampal neurons, STX-bpc displays dose-dependent effects on AP firing frequency (Figure 3A, 3E) and shape (Figure 3B–D, Figure S5A–E) in embryonic rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG) cells. These effects are fully resolved upon toxin wash-off. Application and uncaging of 200 nM STX-bpc reduces AP firing rate to 49% of the initial value; with 500 and 1000 nM STX-bpc, these values fall to 23% 13%, respectively (Figure 3E, Table S3). Photo-deprotecting 1000 nM STX-bpc almost completely blocks AP trains (6/7 cells); the first action potential spike, however, is always recorded. This finding is in contrast to STX-bpc uncaging in hippocampal neurons, which completely shuts down the generation of single action potentials at 500 nM.

Figure 3: Uncaging of 13 effects concentration-dependent changes in action potential shape and propagation in dissociated embryonic dorsal root ganglia cells.

(A) Representative traces depicting initial (I), laser applied (L), 500 nM 13 applied (T), 500 nM 13 and laser applied (TL), and recovered (R) after wash-off AP trains evoked by 500 ms, 250–550 pA current injections. Data taken from replicate current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). (B) Concentration-dependent reduction in AP amplitude after application and uncaging of 13 at listed concentrations. Data calculated from first action potential in current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). Unlisted significant p-values: 200 nM vs 500 nM, p = 0.0064; 500 nM vs 1000 nM, 0.0628 (n = 6–8). (C) Concentration-dependent reduction in AP threshold after application and uncaging of 13 at listed concentrations (n = 6–8). Data calculated from first AP in current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). (D) Representative phase plot depicting application and uncaging of 1000 nM 13. Calculated from first AP in current step 2 vis-à-vis (E). (E) Heat map summary of AP firing rate after application and uncaging of four different concentrations of 13 (100 nM, 200 nM, 500 nM, 1000 nM) color-coded by number of APs per step (four replicate current steps at 0.25 Hz per condition). Equilibrated normalized AP firing rate (i.e., over current steps 2–4) compared below (n = 7–8). (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction). Full statistical analysis is provided in Table S3. See also Figure S4.

In embryonic DRG neurons, every phase of AP shape is altered by STX-bpc uncaging at concentrations ≥500 nM (Figure 3D, Figure S5F–M). Photo-deprotection of 500 nM STX-bpc decreases AP amplitude by 15% (p = 0.005) and shifts threshold to more positive potentials by 9 mV (p = 0.02; Figure S5F, S5I). The magnitude of the maximum rate of AP rise is also diminished by 49% (p = 0.0002) and AP fall by 28% (p = 0.05; Figure S5K–L). Maximal AP acceleration is similarly reduced by 66% (p = 0.0001; Figure S5M). In control experiments, AP shape is impervious to all concentrations of STX-bpc, with the exception of a very slight decrease in AP amplitude observed at 1000 nM (2%, p = 0.008; Figure S5G). Thus, prior to light exposure STX-bpc addition to DRGs is functionally invisible, even at 1 μM concentration.

STX-bpc Performance in Mammalian Brain Tissue

To demonstrate the general utility of STX-bpc for controlling electrical excitability in tissue, we assessed the effects of uncaging this compound in acute cortical slices from mice (Figure 4). These experiments were performed with a low power, LED light source (365 nm, < 20 mW/mm2). Action potential trains were evoked by 500 ms current steps of 50–150 pA and measured by whole-cell current clamp recording. A LED-only control experiment confirmed that light exposure alone, absent toxin or depolarization, did not result in AP generation (Figure 4A–B). Application of 250 nM STX-bpc showed minimal reduction in AP generation prior to light delivery; conversely, photo-uncaging resulted in rapid and efficient block of AP generation (Figure 4A–B).

Figure 4: Activation of STX-bpc 13 abolishes action potentials in layer 4 cortical neurons.

(A) Electrophysiological response of layer 4 cortical neurons (S1bf) to 500 ms 50–150 pA current steps. APs evoked during a baseline period shown in blue, during exposure to 365 nm LED UV light alone (purple), and in the presence of 250 nM STX-bpc 13 (red). APs were blocked following exposure to both UV and 13 (green). The same color scheme is used throughout the figure. (B) Box plot showing the number of APs evoked under the conditions shown in (A). Each point represents a different cell. Dunnett’s test ***p < 0.001. (C) Phase plane plot derived from APs evoked under different experimental conditions indicated by the colored arrows. The axon initial segment (AIS) and somatodendritic (SD) peaks are shown by the black arrows. APs evoked at baseline (blue), in UV but absence of STX-bpc (UV, purple), and in the presence of caged STX-bpc but absence of UV (STX-bpc, red) are similar in shape and size indicating a minimal effect on the AP of UV light or caged STX-bpc. Three APs evoked in UV and in the presence of STX-bpc are shown in green (STX-bpc UV, Green). Green shading indicates AP order. (D) AP voltage traces (upper trace), and first (middle trace) and second (lower trace) derivative plots of the same APs in (C) are shown. The inset on the second derivative plots shows an enlarged portion of the same plot in which the AIS and SD peaks are clearly discernable (E–I). Box plots showing quantification of AP characteristics. The peak ratio (H) and peak amplitude (I) could only be plotted where both SD and AIS peaks were distinguishable (n = 3). Dunnett’s test ***p < 0.001,**p < 0.01 (J) Fast spiking cells (FS) were distinguished from regular spiking cells (RS) based on the average baseline AP firing rate and the half-width of the rhehobase AP. (K) Raster plot showing AP firing over time in the presence of 13 before and during UV light exposure (purple). 13 RS (black) and 8 FS neurons (red) are displayed. Each occurance of an AP is represented by a vertical bar aligned to the onset of UV. (L) Comparison of the time course of AP block following UV between RS and FS cells. (M) The rapidness of the rheobase AP did not predict the latency to AP block following UV in either RS or FS cells. See also Figure S6.

Further analyses of AP waveforms in slice recordings were conducted to characterize the effects of uncaging on signal propagation (Figure 4C–I). Phase plane plots depicting the first time derivative of the AP voltage (dV/dt) versus voltage (mV) were generated and reveal two peaks that appear in the initial rising phase of the action potential (Figure 4C). These data correspond to activation of NaVs in the axon initial segment (AIS, first peak) and somatodendritic NaVs (second peak) as the AP backpropagates from its initiation point in the AIS to the soma and dendritic compartments.30,31 Quantification of AP features was performed using the first and second time derivatives of individual fractionated APs (Figure 4D–I). Such data allow us to assay the effects of the uncaged toxin on the inhibition of different subpopulations of NaVs within the axon and somatodendritic compartments. Following uncaging of 250 nM STX-bpc, the amplitude and maximum first and second time derivative values decrease in APs before sufficient NaV block completely prevents AP initiation (Figure 4D–G). No difference in the relative attenuation of axonal vs somatodendritic responses (AIS/DS peak ratio) was detected, indicating NaVs in these subcompartments are blocked equivalently by uncaging of STX-bpc (Figure 4H).

To determine the duration of light exposure required to achieve complete block of AP generation in cortical neurons from 250 nM STX-bpc uncaging, we recorded from layer 4 cortical regular spiking (RS) neurons and cortical fast spiking (FS) neurons while injecting a continual depolarizing current step to elicit a sustained train of action potentials. RS and FS cells were distinguished based on the half-width of the rheobase AP and the baseline AP firing rate (Figure 4J). LED illumination was initiated after a 5 second recording of baseline AP firing and continued until AP firing terminated (Figure 4K). Histograms of each cell recording show that complete block of AP generation is achieved in most cells within seconds following exposure to LED light (Figure 4K). Analysis of the percent attenuation of AP firing rate over time following uncaging of STX-bpc in RS and FS cells showed comparable efficacy (n = 13–8 per cell type, n.s. p > 0.05, Mann-Whitney test) (Figure 4L). As expected, no relationship was observed between uncaging-effected NaV block (as approximated by the latency to AP termination) and NaV activation (as approximated by the maximum dV/dt of the AP) in either RS or FS cells (n = 13–8 per cell type, RS R2 = 0.01, FS R2 = 0.08) (Figure 4M).

To assess the effect of uncaging on cortical networks, we exposed cortical slices maintained at the air liquid interface to 250 nM STX-bpc while activating network responses through electrical stimulation within cortical layer 5 (L5) (Figure S6). Network responses were recorded by linear multielectrode arrays arranged across all cortical layers. From local field potential recordings, current source density (CSD) calculations were performed to localize current sources and sinks in response to simulation (Figure S6). Pharmacological dissection of the CSD response was used to identify CSD components that correspond to presynaptic and postsynaptic activity (Figure S6A). Using this sensitive measure of cortical network activity, slices were exposed to steps of increasing light intensity until all activity was abolished (Figure S6B–D). No significant separation between presynaptic and postsynaptic responses is observed even under conditions of partial NaV block at intermediate light exposures (4–20 mW/mm2, Figure S6C). This result indicates that the diverse cellular compartments and NaV isoforms distributed throughout the cortical network are similarly inhibited upon photo-deprotection of STX-bpc.

Comparison of Optogenetic Silencing by eNpHR3.0 to Silencing by STX-bpc

To characterize the performance of STX-bpc relative to an established tool for optically silencing neuronal activity, we expressed eNpHR3.0 in the cortex of mice using viral transfection. After 2–4 weeks, current clamp recordings were performed to elicit action potentials in neurons expressing eNpHR3.0. Optogenetic tools for inhibiting AP signaling hyperpolarize the neuron to prevent countervailing depolarizing inputs from triggering NaV activation and AP generation.32 By contrast, tools that silence neurons by specifically blocking NaVs act directly on a essential component of the AP mechanism. Accordingly, optogenetic inhibition should fail to suppress APs in response to sufficiently large inward currents whereas STX-bpc uncaging would be insensitive to such currents. To test this hypothesis, increasingly depolarizing current ramps were applied to neurons over 5 seconds, enabling precise identification of the point at which AP block fails. The effect of eNpHR3.0 on neuronal silencing was validated by recording the maximum current evoked using amber LED light (595 nm) (Figure 5A). Baseline AP generation in response to ramp currents was recorded followed by ramps under amber LED illumination to activate eNpHR3.0 but not STX-bpc, as the latter is insensitive to amber light (Figure 5B).33 To determine if uncaged STX-bpc is capable of inactivating APs that escaped silencing by eNpHR3.0, APs were recorded in response to a third ramp current under 365 nm LED irradiation (Figure 5B). Quantification of AP generation under each condition revealed a reduction in AP generation following eNpHR3.0 of 58%, whereas uncaging of STX-bpc resulted in near complete silencing (98%) (n = 4, **p<0.01, one-way ANOVA with Friedman correction, *p<0.05, Mann-Whitney test) (Figure 5C–D).

Figure 5: Comparison of STX-bpc 13 to optogenetic NpHR3.0 silencing of action potentials.

(A) Schematic of viral injection of viral vector carrying optogenetic inhibition into the cortex. Graph shows validation of eNpHR3.0-mediated hyperpolarization of L4 neurons in cortical slices exposed to 595nm light (n = 6). Imaging shown in 4x and 40x magnification (infrared and fluorescence) of whole cell patch clamp experiments. Expression of eNpHR3.0 fluorescence is visible with mCherry. (B) APs were evoked in L4 RS cells by a 5 second ramp current injection in current clamp in the presence of STX-bpc (250 nM) under conditions of 595nm light at the onset of the current ramp to activate eNpHR3.0 in isolation or 365nm with light on 20 seconds prior to the current ramp to uncage STX-bpc. (C) Quantification of AP generation in response to ramp currents at baseline compared to under optogenetic inhibition and uncaging of STX-bpc (n = 4, *p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA with Friedman correction). (D) Box plot showing the % reduction in APs evoked by ramp current injection by eNpHR3.0 activation and uncaging of STX-bpc compared to baseline (n = 4, *p < 0.05, Mann-Whitney test).

Dissection of Zebrafish Swimming by Focal Silencing of Neuronal Activity Using STX-bpc

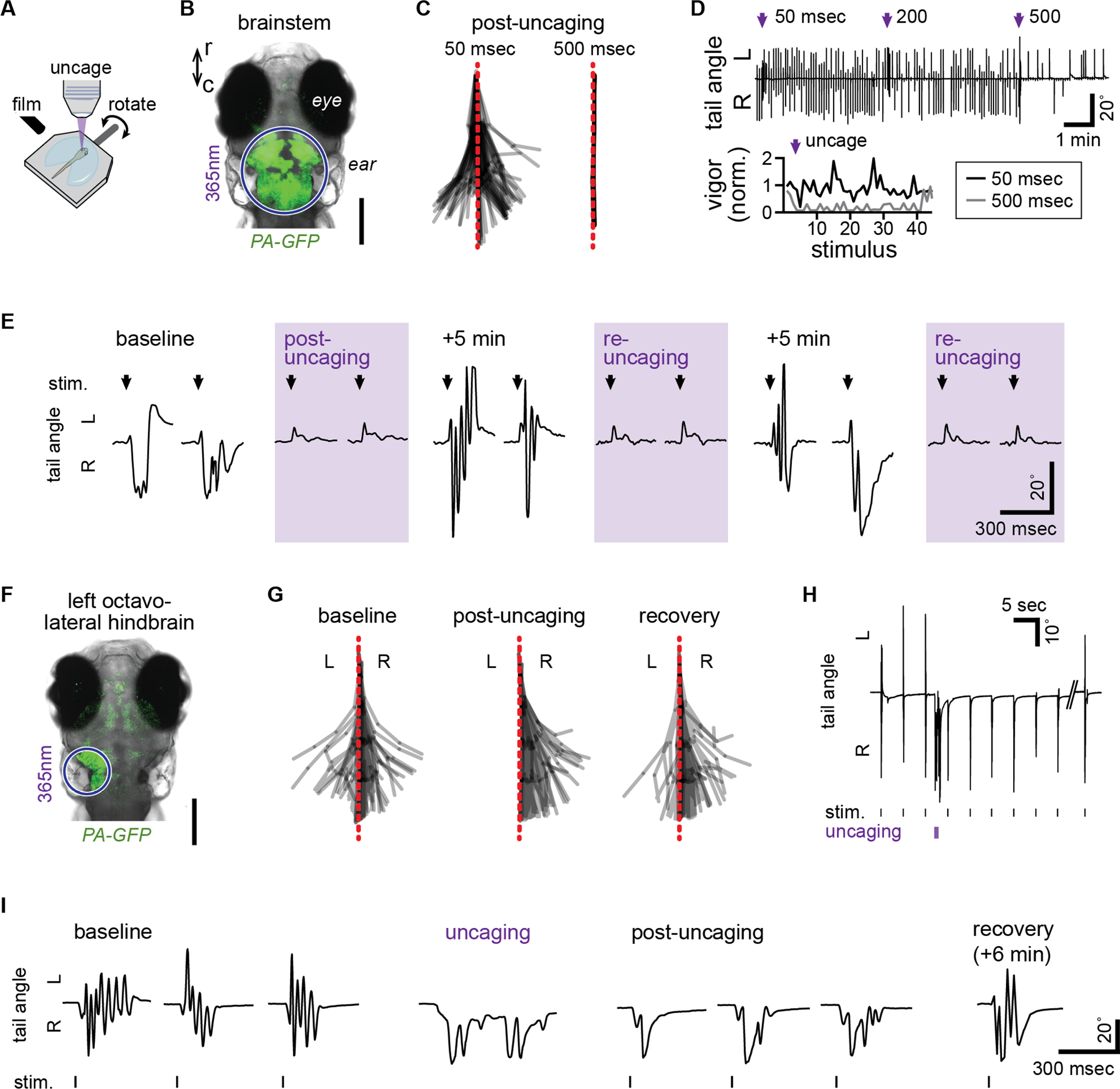

To assess the performance of STX-bpc in vivo, we examined the utility of STX-bpc uncaging for the control of locomotion in larval zebrafish. For these experiments, we tracked tail movements in response to swim-eliciting stimulation of the inner ear before and after light exposure (Figure 6A). To validate in vivo silencing of neural activity with STX-bpc, we performed a single 50 μM STX-bpc injection into the hindbrain ventricle and focused uncaging light in the brainstem, verifying localization with UV-sensitive photo-activatable GFP (Figure 6B). Injection of the caged toxin had no observable effect on behavior, but immediately after irradiating the brainstem, stimulus responses were completely abolished, indicating silencing of brainstem neurons that transform sensation into swimming (Figure 6C). The duration and probability of stimulus response interference was dependent on the duration of uncaging, with 500 ms of light exposure abolishing responses for 10 seconds and preventing most responses for the subsequent 4 minutes (Figure 6D; ***p < 0.001, F2,57 = 9.91, one-way ANOVA of integrated absolute tail deflections to 20 subsequent stimuli). Swimming responses returned within 5 minutes following irradiation, presumably due to dissociation of bound toxin. Uncaging from the available pool of STX-bpc can be repeated with recovery of block of locomotor function over several cycles (Figure 6E).

Figure 6: Uncaging of STX-bpc 13 in vivo manipulates larval zebrafish behavior.

(A) Schematic for swim tracking following rotation stimulus presentation and focal uncaging. (B) Confocal photomicrograph of dorsal perspective of a larval zebrafish head expressing photoactivatable GFP (PA-GFP), showing the region of UV light exposure (purple circle) during brainstem-wide uncaging. Scale bar = 200 μm. (C) Superimposed tail segment positions from a tracked larva across 3 stimulus presentations following 50 msec (left) or 500 msec (right) uncaging in the brainstem. (D) Tail angle (top) of a larva throughout a train of stimulus presentations every 5 sec, interspersed with brainstem uncaging of increasing duration (purple arrow). Swimming vigor (bottom) is plotted as a function of stimulus number for 3 stimuli before and 42 after uncaging for 50 and 500 msec. (E) Tail angle during the first 2 stimulus presentations (arrow) of series without uncaging or immediately following uncaging (purple shading, post-uncaging or re-uncaging). (F) Photomicrograph, as in (B), showing the location of activated PA-GFP following focal uncaging in the left octavolateral hindbrain to unilaterally inactivate sensory areas for rotation stimuli. Scale bar = 200 μm. (G) Superimposed tail positions from a tracked larva across 3 stimulus presentations at baseline, immediately following uncaging in the left octavolateral hindbrain (post-uncaging), and 6 min after uncaging (recovery). (H,I) Tail angle of the larva in (G) in response to rotation stimulus presentation before and after uncaging (H,I) and following recovery (I). See also Video S1.

We next sought to make nuanced changes to swimming behavior through focal control of neuronal function. Head rotation and auditory stimuli are transduced by both ears, eliciting bilateral activity in the brainstem that provides descending input to the spinal cord for bending the tail.34 To manipulate swimming responses to our symmetrical stimulation of the ears, we precisely localized uncaging light to the left octavolateral hindbrain (Figure 6F) to unilaterally silence sensory neurons that encode the stimulus and ultimately drive swimming. After injection but before uncaging of STX-bpc, swimming responses were symmetrical; however, following irradiation swimming was transiently and exclusively contraversive, bending to the unaffected side. The observed behavior suggests focal silencing inhibits the recruitment of muscles on the silenced side (Figure 6G–I, Video S1; *p < 0.05, Χ2(2) = 7.45, Kruskal-Wallis test on tail midline crossings comparing baseline, post-uncaging, and recovery). Swimming responses were reliably evoked and consistently asymmetric immediately following uncaging, and leftward tail bends re-emerged within 30 seconds and gradually recovered until responses were again symmetrical 6 minutes later. Uncaging also directly elicited tail bends away from the inhibited side (Figure 6H–I, Video S1), consistent with acute disinhibition of the right brainstem through loss of commissural inhibition from the site of uncaging on the left. Thus, focal uncaging of STX-bpc enables high-precision control and tuning of NaV current, electrical excitability, and finally, behavior, in a rapid, reproducible, and reversible manner.

DISCUSSION

We have designed and validated STX-bpc 13 as a NaV-selective small molecule tool for the spatiotemporal manipulation of electrical transmission in vitro and in vivo. STX-bpc incorporates multiple carboxylate groups on a modified nitrobenzyl platform to destabilize toxin binding to NaVs.18 NaV block following light-promoted deprotection of STX-bpc proceeds more rapidly than other caged toxins previously described (t1/2 ≤ 1.1 seconds at all concentrations tested; Figure S3B–E).35 The inertness of STX-bpc towards NaVs enables experiments over a sizable concentration window (≤ 500 nM), thus affording a large dynamic range over which to regulate AP signaling (Table S4).18 Brief light pulses using either a 355 nm laser or low-cost LEDs are sufficient to promote inhibitor release from STX-bpc.

The efficacy of STX-bpc uncaging in dissociated cells, tissue slice, and zebrafish establishes the utility of this tool compound. Uncaging STX-bpc elicits dose-dependent decreases in AP firing rate in both dissociated hippocampal and DRG neurons, the latter in spite of the preponderance of STX-resistant NaVs (NaV1.8, 1.9) in sensory neurons—a result likely due to the predominant role of NaV1.7, a STX-sensitive channel in rat, for effecting threshold depolarization.36 In hippocampal neurons, a comparison of NaV current block to AP frequency reduction is in keeping with our prior work18 (Figure S7A, Table S4). Our results show that AP firing rate is largely insensitive to a small percentage of NaV block (≤ 11% inhibition of peak current),28 but dramatically reduced if inhibition of peak current equals or exceeds 67%. AP firing rate in DRG neurons shows greater resistance to block by the released inhibitor (1), with >2-fold the concentration of STX-bpc required to elicit similar reductions in AP frequency (Figure S7B). Analysis of the AP waveform in both dissociated neurons and acute cortical slice reveals that STX-bpc is inert prior to uncaging, but following photolytic deprotection, 1 impacts all NaV-dependent components of the AP (firing threshold, velocity, acceleration). Additionally, analysis of the AIS/DS peak ratio shows that STX-bpc uncaging exerts similar effects on both axonal and somatodendritic NaVs, establishing the potential of this tool to target sodium channels in subcellular compartments.30

The effectiveness of STX-bpc uncaging for behavioral control is highlighted in larval D. rerio. As in experiments performed with rodent neurons and tissue slice, STX-bpc remains functionally inert prior to LED-induced uncaging, at which point the released 1 rapidly and selectively abrogates activity. Application of STX-bpc to the entire nervous system has no apparent effect on behavior, permitting inducible and focal uncaging upon light exposure. Behavioral effects are restricted to the site of uncaging, as swimming manipulations are kinematically nuanced and context-specific. Furthermore, the rapid recovery from uncaging (~5 minutes) coupled with replenishment of caged STX-bpc from the injected pool enables toggling of activity between silenced and active states and behavior from manipulated to intact. Resultant changes in zebrafish locomotion are reproducible, reversible, and spatiotemporally precise.

Limitations of the Study

Optogenetic and optochemical methods for neuronal silencing present respective drawbacks for utilization. The former requires expression of ectopic proteins, which can result in toxicity37,38,39 as well as the altered capacitance,40 electrochemical gradients,41 and pH42 of the target cells.43 Small molecule tools, on the other hand, lack the precision of genetic methods32 and can be plagued by problems stemming from off-target protein interactions44 and/or capricious binding kinetics that vary with cell/tissue type.35 With photocaged compounds, diffusion competes with binding of the uncaged ligand, thus presenting a unknown variable that influences spatiotemporal control. Finally, as for any method or protocol that relies on light stimulus, light penetration and cellular phototoxicity can be problematic.45

STX-bpc overcomes many of the challenges associated with optochemical probes, but remains imperfect. STX-bpc is non-toxic at the requisite concentrations, application is straightforward, and the response time following irradiation is rapid (seconds). The time course for STX-bpc wash-out, however, remains dependent on tissue type—seconds on dissociated neurons, minutes in slice and live zebrafish (as assessed by behavioral response). The efficacy of light-induced uncaging is easily benchmarked using voltage-clamp electrophysiology (Figure 1–3) and remains consistent across repetitive stimulation even in vivo (Figure 6E). Absolute determination of the amount of uncaged toxin, however, is not possible. Nonetheless, free toxin diffusion does not appear to compromise the focal precision of NaV block (Figure 6F–I). Moreover, although uncaging of STX-bpc necessitates UV irradiation, only brief light pulses (5 ms) are required to achieve high uncaging efficiency of the nitrobenzyl-derived protecting group, thus minimizing attendant problems with phototoxicity.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that STX-bpc enables optically-induced control of electrical activity and neuronal silencing in cells, tissue, and zebrafish. This reagent operates absent the need for specialized equipment or extensive optimization and, most importantly, without genetic engineering. Accordingly, STX-bpc should serve as a valuable complement to available optogenetic methods for blocking electrical activity to modulate cellular communication and behavior, and may find application in non-model organisms for which efficient genetic manipulation methods are not yet optimized.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Requests for additional information and/or resources and reagents should be directed to lead contact Professor Justin Du Bois (jdubois@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

STX-bpc and related derivatives can be requested from the lead contact. The availability of photocaged saxitoxins is limited due to the intensive, multi-step chemical synthesis that is required to access these reagents; however, small quantities are available upon request. And approved materials transfer agreement (MTA) is required prior to shipping.

Data and code availability

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. All synthetic characterization data generated as part of this study are included in the supplemental material. Summary data for all main and supporting figures are deposited on Mendeley, access information for which appears in the Key Resources Table.

All original code has been deposited at GitHub.com/MakinsonLab and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The version of record can be found at DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.10819300.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| AAV5::hSyn-eNpHR3.0-mCherry-WPRE | UNC Vectore Core | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| STX-bpc | Du Bois Laboratory, Stanford University | N/A |

| Deposited data | ||

| Compiled data for main and supplementary figures | Mendeley Data | DOI: 10.17632/ng6v9kh2gn.2

https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/ng6v9kh2gn/2 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| NaV1.2 CHO | Catterall Laboratory, University of Washington | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Rat: CR® (Sprague Dawley) | Charles River | Strain Code 001 |

| Mice: C57BL6/J | Jackson Laboratory | Cat. No. 000664 |

| Zebrafish: Tg(mitfa-/-) | Lister et al.49 | ZFIN: ZDB-ALT-990423–22 |

| Zebrafish: Tg(alpha-tubulin:C3PA-GFP) | Ahrens et al.57 | ZFIN: ZDB-ALT-120919–1 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| pClamp | Molecular Devices | RRID:SCR_011323 https://support.moleculardevices.com/s/article/Axon-pCLAMP-11-Electrophysiology-Data-Acquisition-Analysis-Software-Download-Page |

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 https://www.graphpad.com/features |

| Chemdraw | Perkin Elmer | RRID:SCR_016768 https://revvitysignals.com/products/research/chemdraw |

| IGOR Pro | WaveMetrics | RRID:SCR_000325 https://www.wavemetrics.com/order/order_igordownloads.htm |

| Python Programming Language 3.7 | Python | RRID:SCR_008394 https://www.python.org/downloads/ |

| DeepLabCut | DeepLabCut Project | RRID: SCR_021398 https://deeplabcut.github.io/DeepLabCut/README.html |

| Matlab | Mathworks | RRID:SCR_00162 https://www.mathworks.com/help/install/install-products.html |

| Elephant 0.7.0 | Elephant Electrophysiology Analysis Toolkit | RRID:SCR_003833 https://elephant.readthedocs.io/en/v0.7.0/developers_guide.html |

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing rat NaV 1.2

Stably-expressing NaV1.2 CHO cells were generously provided by Dr. W. A. Catterall (University of Washington, Department of Pharmacology). Cells were grown on 10 cm tissue culture dishes in RPMI 1640 medium with l-glutamine (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC, Manassas, VA), 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), and 0.2 μg/mL G418 (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). Cells were kept in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator and passaged approximately every three days. Passaging of cells was accomplished by aspiration of media, washing with phosphate-buffered saline, treatment with 1 mL of trypsin-EDTA (0.05% trypsin, Millipore Sigma, Hayward, CA) until full dissociation of cells was observed (approximately five minutes), and dilution with 4 mL of growth medium. Cells were routinely passaged at 1 in 20 to 1 in 10 dilution.

At least 1 hour prior to electrophysiology experiments, cells were trypsinized as described above and plated onto 5 mm diameter, 0.15 mm thick round glass coverslips (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Cell coverslips were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator.

Sprague Dawley rat embryonic day 18 hippocampal neurons

One day prior to dissection, 5 mm diameter, 0.15 mm thick round glass coverslips (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) were coated overnight with 1 mg/mL poly-d-lysine hydrobromide (PDL, molecular weight 70,000–150,000 Da, Millipore Sigma, Hayward, CA) in 0.1 M, pH 8.5 borate buffer in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator.

Pregnant (E18) female Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River and euthanized via carbon dioxide inhalation with subsequent cervical dislocation. All animal euthanasia and dissection procedures were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines for the use of experimental animals and approved by the Stanford Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC). Embryonic day 18 fetuses of both sexes were surgically removed and hippocampi were dissected into ice-cold Hibernate E (BrainBits, LLC, Springfield, IL) as previously described.46 Briefly, each embryo was decapitated post-mortem; the skin and skull of each head were then hemisected along the sagittal plane. These tissues were peeled back to reveal the cortices of the brain, which were rapidly transferred to a petri dish containing ice-cold Hibernate E. Hippocampi were snipped from the underside of each cortex with tweezers and transferred to fresh Hibernate E. Following dissection, cells were dissociated in 2 mL of trypsin-EDTA for 15 minutes in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator. Subsequently, trypsinized cells were quenched with 10 mL of quenching medium (DMEM high glucose (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and 1 mM MEM sodium pyruvate (Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA). Tissue was allowed to settle, supernatant was removed, and the tissue pellet was rinsed twice more with 10 mL of quenching medium. Cells were then manually dissociated into 2 mL of plating medium (DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, and 1 mM MEM sodium pyruvate) by pipetting with a fire-polished 9” borosilicate glass Pasteur pipet (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Cells were plated onto PDL-coated 5 mm glass coverslips (see above) in 35 mm tissue culture dishes containing 2 mL of plating medium at a density of 200,000 cells/dish (for voltage-clamp experiments) or 600,000 cells/dish (for current-clamp experiments). After 45 minutes, coverslips were transferred to new tissue culture dishes containing 2 mL of maintenance medium (neurobasal supplemented with 1x B-27 Supplement, 1x Glutamax, and 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA)). Cells were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator and fed every 3–4 days by changing 50% of the working medium.

Sprague Dawley rat embryonic day 15 dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons

Dissociated DRG cells were prepared in an analogous manner to hippocampal neurons, with the following exceptions. First, pregnant (E15) female Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Charles River and euthanized via carbon dioxide inhalation with subsequent cervical dislocation. Second, coverslips were coated with 10 μg/mL PDL and 2 μg/mL mouse laminin I (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN).47 Third, after treating trypsinized cells with quenching media, the working solution was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 30 s to yield a cell pellet. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was immediately dissociated into plating medium, as described above. Following dissociation, cells were plated in plating media at a density of 200,000 cells/dish for both voltage- and current-clamp experiments. After 2–3 hours, coverslips were transferred to new culture dishes containing 2 mL of DRG maintenance medium (neurobasal supplemented with 1x B-27 Supplement, 1x Glutamax, 50 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 5 mg/mL NaCl, 7.5 μg/mL 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine, 17.5 μg/ml uridine, and 100 ng/mL HPLC-purified nerve growth factor (NGF) 2.5S, beta subunit (Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada)).48 Cells were maintained in a 37 °C, 5% carbon dioxide, 96% relative humidity incubator and fed every 3–4 days by changing 50% of the working medium.

Mice

All mouse-related procedures were performed according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of Columbia University. Experiments were perforemed using wildtype P15–60 male and female animals on the C57BL6/J strain. Animals were generated by crossing C57BL6/J animals obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) at Columbia University. Animals were group housed according to sex and were not used in any previous procedures.

Zebrafish

Four to seven days post-fertilization (d.p.f.), wild-type zebrafish of the mitfa−/− transgenic line were used for experiments unless otherwise indicated.49 Zebrafish larvae do not undergo sexual differentiation by the age of experimentation. In all cases, naturally spawned eggs were collected, cleaned, and maintained at 28C in E3 solution (0.30M NaCl, 0.01M KCl, 0.03M CaCl2, 0.02M MgSO4, pH 7.1) on a 14/10 hour light/dark cycle at a density of 40 per 100-mm diameter Petri dish. Larvae without inflated swim bladders at the time of experiment were excluded. Animal handling and experimental protocols were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Letters and Sciences Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

METHOD DETAILS

Synthesis:

All reagents were obtained commercially unless otherwise noted. Organic solutions were concentrated under reduced pressure by rotary evaporation. Anhydrous CH2Cl2 and HPLC-grade CH3CN were obtained from commercial suppliers and used as is. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) was passed through two columns of activated alumina prior to use. Triethylamine was distilled from calcium hydride.

Product purification was accomplished using forced-flow chromatography on Silicycle ultrapure silica gel (40–63 μm). Semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Varian ProStar model 210. Thin layer chromatography was performed with EM Science silica gel 60 F254 plates (250 μm). Visualization of the developed chromatogram was accomplished by fluorescence quenching. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained from the Vincent Coates Foundation Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at Stanford University. Samples were analyzed with LC/ESI-MS by direct injection onto a Waters Acquity UPLC and Thermo Fisher Exactive mass spectrometer scanning m/z 100–2000. Methanol was used as the LC mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.175 mL/min. UV/Vis spectra were recorded on a Thermo NanoDrop One.

Saxitoxin derivatives were quantified by 1H NMR spectroscopy on a Varian Inova 600 MHz NMR instrument using distilled DMF as an internal standard. A relaxation delay (d1) of 20 s and an acquisition time (at) of 10 s were used for spectral acquisition. The concentration of the toxin derivative was determined by integration of 1H signals corresponding to toxin against those from a fixed concentration of the DMF standard.

Triprotected saxitoxin N21-ethylamine (14).

To an ice-cold solution of Tces- and Troc-protected decarbamoyl saxitoxin50,51 (39 mg, 0.06 mmol) in 2.5 mL of THF was added 1,1’-carbonyldimidazole (25 mg, 0.157 mmol, 2.5 equiv). After 5 min, the reaction was warmed to room temperature and stirred for 4 h. Following this time, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 2.9 mL of saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The biphasic mixture was stirred vigorously for 5 min then diluted with 10 mL of THF and transferred to a separatory funnel. The organic phase was collected and the aqueous phase was extracted with 3 × 10 mL of THF. The combined extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to a yellow foam. This material was dissolved in 2.5 mL of THF and to this solution was added N-Boc-1,2-ethylenediamine (50 μL, 0.314 mmol, 5.0 equiv). The pale yellow solution was stirred for 3 h following which time 2.9 mL of 0.5 M aqueous HCl was added. The biphasic mixture was stirred vigorously for 5 min then diluted with 10 mL of EtOAc and transferred to a separatory funnel. The organic phase was collected and the aqueous phase was extracted with 3 × 10 mL of EtOAc. The combined extracts were dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to a yellow foam. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→7:3 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded carbamate 1 (30 mg, 59%) as a white powder. Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl; Tces, 2,2,2-trichloroethoxysulfonyl; Troc, 2,2,2-trichloroethoxycarbonyl. TLC (7:3 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.51.

Yield: 30 mg (59%); 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3CN): δ 8.84 (br s, 1H), 7.30 (br s, 1H), 7.06 (br s, 1H), 5.71 (br s, 1H), 5.42 (br s, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 4.69 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 4.47 (s, 1H), 4.14–3.97 (m, 3H), 3.79–3.88 (m, 1H), 3.71–3.58 (m, 1H), 3.15–2.02 (m, 4H), 2.79–2.69 (m, 2H), 1.40 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3CN) δ 206.0, 162.5, 161.6, 158.9, 157.1, 156.7, 96.7, 94.9, 79.4, 78.8, 75.6, 75.3, 63.8, 59.7, 54.4, 41.9, 41.5, 40.7, 33.7, 28.5 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C22H30Cl6N8O10S, 809.0010, found 809.0004; IR (thin film): ν = 3310, 2929, 1706, 1586, 1530, 1391, 1230, 1179 cm−1.

Saxitoxin N21-ethylamine (1).

To a solution of carbamate 14 (15 mg, 18.5 μmol) in 4.6 mL of a 3:1 MeOH/H2O was added 212 μL of trifluoroacetic acid. The mixture was stirred for 30 min then PdCl2 (1.13 mg, 9.2 μmol, 0.5 equiv) was added. The suspension was sparged with a gentle stream of N2 for 5 min and then H2 for 5 min. The flask was fitted with a balloon of H2 (1 atm) and the contents stirred for 3.5 h. Following this time, the mixture was filtered through a Fisher 0.2 μm PTFE syringe filter. The flask and filter were rinsed with 4 mL of MeOH and 7.4 mL of 1.0 N aqueous HCl, and the combined filtrates were concentrated under reduced pressure. The isolated residue was redissolved in 2.3 mL of 1.0 N aqueous HCl and the mixture was stirred for 1 h, then frozen and lyophilized to remove all volatiles. The product was purified by reversed-phase HPLC (Silicycle SiliaChrom AQ C18, 5 μm, 10 × 250 mm column, eluting with a gradient flow of 10→20% CH3CN in 10 mM aqueous C3F7CO2H over 60 min, 214 nm UV detection). At a flow rate of 4 mL/min, 1 had a retention time of 22–30 min and was isolated as a white powder following lyophilization (6.13 μmol, 33%, 1H NMR quantitation). This compound has been characterized previously.52,53

(4-Iodophenyl)(morpholino)methanone (15).

To a solution of 4-iodobenzoic acid (248 mg, 1.0 mmol) in 6.0 mL of a 5:1 mixture of THF/CH2Cl2 was added successively 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (230 mg, 1.2 mmol, 1.2 equiv), 1-hyroxybenzotriazole hydrate (185 mg, 1.2 mmol, 1.2 equiv), and morpholine (173 μL, 2.0 mmol, 2.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 14 (286 mg, 90%) as a white foam. TLC (9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.66.

Yield: 286 mg (90%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.75 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 3.71 (br s, 4H), 3.64 (br s, 2H), 3.43 (br s, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.6, 137.8, 134.8, 128.9, 96.2, 66.9, 48.4, 42.6 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C11H12INO2 317.9985, found 317.9972; IR (thin film): ν = 2854, 1640, 1587, 1457, 1254, 1112 cm−1.

N-(tert-Butyl)-4-iodobenzamide (16).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 15 starting from 4-iodobenzoic acid (740 mg, 4.8 mmol) and substituting tert-butylamine for morpholine. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 100:0→97:3 CH2Cl2/MeOH) afforded 15 (1.06 g, 87%) as a white powder. TLC (7:3 hexanes/EtOAc): Rf = 0.62.

Yield: 1.06 g (87%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.63 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.17 (br s, 1H), 1.40 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.1, 137.4, 135.3, 128.4, 97.8, 51.7, 28.8 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C11H14INO 304.0193, found 304.0181; IR (thin film): ν = 3317, 1634, 1539, 1449, 1320, 1216, 1006 cm−1.

Ethyl 1-(4-iodobenzoyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (17).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 15 starting from 4-iodobenzoic acid (500 mg, 2.0 mmol) and substituting ethyl isonipecotate for morpholine. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 5:0→4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 17 (745 mg, 94%) as a clear oil. TLC (9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.73.

Yield: 745 mg (94%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.65 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 4.38 (br s, 1H), 4.06 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.60 (br s, 1H), 2.96 (br s, 2H), 2.48 (tt, J = 10.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (br s, 1H), 1.77 (br s, 1H), 1.61 (br s, 2H), 1.16 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 173.8, 169.2, 137.5, 135.3, 128.5, 95.6, 60.5, 46.8, 41.4, 40.7, 28.3, 27.7, 14.1 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C15H18INO3 388.0404, found 388.0393; IR (thin film): ν = 2954, 2860, 1728, 1630, 1437, 1315, 1181, 1146, 1041, 1003 cm−1.

Allyl 4-iodobenzoate (18).

To a solution of 4-iodobenzoic acid (850 mg, 3.4 mmol) in 34 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide was added i-Pr2NEt base (720 μL, 4.1 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and allyl bromide (360 μL, 4.1 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 16 h then diluted with 200 mL of CH2Cl2 and transferred to a separatory funnel containing 200 mL of saturated aqueous NaHCO3. The organic layer was collected and the aqueous layer was extracted with 2 × 200 mL of CH2Cl2. The organic fraction was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to a clear oil. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→8:2 hexanes/EtOAc) afforded 18 (780 mg, 79%) as a clear oil. TLC (9:1 hexanes/EtOAc): Rf = 0.65.

Yield: 780 mg (79%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.77–7.70 (m, 4H), 6.04–5.95 (m, 1H), 5.37 (dd, J = 17.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 4.48 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.6, 137.7, 132.0, 131.0, 129.6, 118.5, 100.9, 65.7 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C10H9IO2 288.9720, found 288.9724; IR (thin film): ν = 2943, 1724, 1587, 1393, 1267, 1177, 1102, 1008 cm−1.

(5-Iodo-1,3-phenylene)bis(morpholinomethanone) (19).

To a solution of 5-iodoisophthalic acid (500 mg, 1.7 mmol) in 12 mL of a 5:1 mixture of THF/CH2Cl2 was added successively 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (788 mg, 4.1 mmol, 2.4 equiv), 1-hyroxybenzotriazole hydrate (633 mg, 4.1 mmol, 2.4 equiv), and morpholine (591 μL, 6.8 mmol, 4.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 24 h and then concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 5:0→3:2 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 19 (620 mg, 84%) as a white foam. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.42.

Yield: 620 mg (84%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.70 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (br s, 8H), 3.52 (br s, 4H), 3.31 (br s, 3.31) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 167.3, 137.5, 136.9, 124.5, 94.2, 66.5 (2), 48.0, 42.5 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C16H19IN2O4 431.0462, found 431.0451; IR (thin film): ν = 2857, 1634, 1439, 1410, 1274, 1114, 1036 cm−1.

5-Iodo-N1,N1,N3,N3-tetramethylisophthalamide (20).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 19 starting from 5-iodoisophthalic acid (500 mg, 1.7 mmol) and substituting 2.0 M dimethylamine in THF (2.5 mL, 6.9 mmol, 4.0 equiv) for morpholine. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 5:0→2:3 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 20 (445 mg, 75%) as a white powder. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.44.

Yield: 445 mg (75%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.77 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 2H), 7.37 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 3.05 (br s, 6H), 2.95 (br s, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.0, 138.4, 136.9, 124.8, 124.7, 94.1, 39.6, 35.4 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C12H15IN2O2 347.0251, found 347.0239; IR (thin film): ν = 3482, 2932, 2360, 1635, 1506, 1394, 1270, 1187, 1103 cm−1.

Diallyl 5-iodoisophthalate (21).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 18 starting from 5-iodoisophthalic acid (1.0 g, 3.4 mmol) using 2.4 equivalents of i-Pr2NEt and allyl bromide. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→8:2 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 21 (1.04 g, 81%) as a clear oil. TLC (9:1 hexanes/EtOAc): Rf = 0.55.

Yield: 1.04 g (81%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.55 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 6.03–5.93 (m, 2H), 5.37 (dd, J = 17.1, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 5.26 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 4.78 (d, J = 5.8 Hz, 4H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.0, 142.6, 132.4, 131.8, 130.1, 119.2, 93.6, 66.4 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C14H13IO4 372.9931, found 372.9933; IR (thin film): ν = 3081, 1727, 1361, 1300, 1232, 1137, 985, 934 cm−1.

Diethyl 1,1’-(5-iodoisophthaloyl)bis(piperidine-4-carboxylate) (22).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 19 starting from 5-iodoisophthalic acid (876 mg, 3.0 mmol) and substituting ethyl isonipecotate for morpholine. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 5:0→4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 22 (1.27 g, 75%) as a clear oil. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.59.

Yield: 1.27 g (75%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.67 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.34 (br s, 2H), 4.04 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 3.55 (br s, 2H), 2.97 (br s, 4H), 2.46 (tt, J = 10.5, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (br s, 2H), 1.77 (br s, 2H), 1.64 (br s, 2H), 1.55 (br s, 2H), 1.15 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 173.7, 167.4, 138.0, 136.5, 123.9, 94.3, 60.5, 46.8, 41.4, 40.6, 28.3, 27.6, 14.1 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H31IN2O6 571.1300, found 571.1294; IR (thin film): ν = 2955, 2861, 1728, 1635, 1446, 1410, 1316, 1273, 1182, 1041 cm−1.

(4-(Hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)phenyl)(morpholino)methanone (23).

To a – 40 °C solution of i-PrMgCl•LiCl (1.5 mL of 1.3 M in THF, 1.95 mmol, 1.3 equiv) was added dropwise a solution of 15 (476 mg, 1.5 mmol) in 7.5 mL of THF. The reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at −40 °C. Following this time, a solution of 6-nitropiperonal (293 mg, 1.5 mmol) in 6.0 mL THF was added dropwise. The reaction mixture was warmed to room temperature over 2 h and quenched by the addition of 5 mL of saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The solution was transferred to a separatory funnel containing 10 mL of EtOAc. The organic layer was collected and the aqueous layer was extracted with 2 × 10 mL of EtOAc. The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 23 (306 mg, 53%) as a light yellow powder. TLC (8:2 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.39.

Yield: 306 mg (53%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (s, 1H), 6.41 (s, 1H), 6.11 (s, 2H), 3.73 (br s, 4H), 3.62 (br s, 2H), 3.42 (br s, 2H), 2.81 (br s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.3, 152.5, 147.5, 143.9, 142.2, 136.2, 134.7, 127.4, 127.2, 108.4, 105.6, 103.3, 70.8, 67.0 (2), 48.4, 42.9 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C19H18N2O7 387.1187, found 387.1176; IR (thin film): ν = 3374, 2917, 1617, 1521, 1483, 1436, 1333, 1259, 1114, 1035 cm−1.

N-(tert-Butyl)-4-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)benzamide (24).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 23 starting from 16 (305 mg, 0.82 mmol). Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→7:3 hexanes/EtOAc) afforded 24 (200 mg, 48%) as a light yellow powder. TLC (7:3 hexanes/EtOAc): Rf = 0.11.

Yield: 200 mg (48%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.64 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (s, 1H), 6.43 (s, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 5.90 (br s, 1H), 1.46 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.9, 152.4, 147.5, 145.0, 142.3, 136.1, 135.4, 127.1, 127.0, 108.5, 105.7, 103.2, 71.0, 51.9, 29.0 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C19H20N2O6 373.1394, found 373.1383; IR (thin film): ν = 3335, 2922, 1636, 1521, 1483, 1332, 1259, 1036 cm−1.

Ethyl 1-(4-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)benzoyl)piperidine-4-carboxylate (25).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 23 starting from 17 (581 mg, 1.5 mmol), but at a higher reaction concentration using 3.0 mL of THF to dissolve both 17 and 6-nitropiperonal. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 25 (295 mg, 43%) as a yellow foam. TLC (9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.38.

Yield: 295 mg (43%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 6.34 (s, 1H), 6.06 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 4.39 (br s, 1H), 4.25 (br s, 1H), 4.10 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.65 (br s, 1H), 2.98 (br s, 2H), 2.51 (tt, J = 10.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 1.94 (br s, 1H), 1.80 (br s, 1H), 1.64 (br s, 2H), 1.21 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 174.2, 170.3, 152.3, 147.1, 144.2, 141.8, 136.7, 134.7, 127.1, 126.9, 108.2, 105.2, 103.1, 70.3, 60.7, 47.1, 41.7, 40.9, 28.5, 28.0, 14.2 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C23H24N2O8 457.1605, found 457.1592; IR (thin film): ν = 3372, 2927, 1728, 1616, 1522, 1483, 1447, 1365, 1332, 1258, 1183, 1148, 1038, 930 cm−1.

5-(Hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)-N1,N1,N3,N3-tetramethylisophthalamide (26).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 23 starting from 20 (242 mg, 0.7 mmol), but at a higher reaction concentration using 1.5 mL of THF to dissolve 20 and 2 mL of THF to dissolve 6-nitropiperonal. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 2:0→1:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 26 (216 mg, 74%) as a yellow foam. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.19.

Yield: 216 mg (74%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.40 (s, 1H), 7.34 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.28 (s, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (s, 1H), 6.08 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 4.88 (br s, 1H), 3.02 (br s, 6H), 2.88 (br s, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 170.7, 152.5, 147.3, 143.6, 141.7, 136.5, 136.1, 127.2, 127.0, 125.0, 124.8, 108.2, 108.0, 105.3, 105.1, 103.3, 103.1, 102.9, 70.3, 70.1, 39.8, 39.6, 35.6, 35.4 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C20H21N3O7 416.1452, found 416.1441; IR (thin film): ν = 3358, 2360, 1617, 1506, 1484, 1396, 1334, 1259, 1034 cm−1.

(5-(Hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(morpholinomethanone) (27).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 26 starting from 19 (300 mg, 0.7 mmol). Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 2:0→1:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 27 (235 mg, 67%) as a yellow foam. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.11.

Yield: 235 mg (67%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.29 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (s, 1H), 6.34 (s, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 1.1 Hz, 2H), 4.17 (br s, 1H), 3.72 (br s, 8H), 3.57 (br s, 4H), 3.33 (br s, 4H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.4, 152.6, 147.5, 143.7, 141.9, 136.0, 135.7, 127.4, 125.1, 108.0, 105.4, 103.3, 70.3, 66.8 (2), 48.3, 42.7 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H25N3O9 500.1664, found 500.1651; IR (thin film): ν = 3384, 2969, 2916, 2859, 1628, 1521, 1483, 1426, 1334, 1252, 1115, 1036 cm−1.

Allyl 4-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)benzoate (28).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 26 starting from 18 (387 mg, 1.3 mmol). Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 20:0→19:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 28 (181 mg, 38%) as a yellow solid. TLC (19:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.67.

Yield: 181 mg (38%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.01 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.48 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (s, 1H), 6.46 (s, 1H), 6.11 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 2H), 6.07–5.97 (m, 1H), 5.40 (dd, J = 17.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 5.28 (dd, J = 10.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (br s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 166.1, 152.5, 147.6, 146.7, 142.5, 135.7, 132.3, 130.0, 129.8, 126.9, 118.4, 108.5, 105.7, 103.3, 71.0, 65.7 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C18H15NO7 358.0921, found 358.0908; IR (thin film): ν = 3444, 2917, 1718, 1611, 1521, 1504, 1483, 1421, 1361, 1332, 1261, 1118, 1035, 928 cm−1.

Diallyl 5-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)isophthalate (29).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 26 starting from 21 (500 mg, 1.3 mmol). Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 20:0→19:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 29 (217 mg, 37%) as a yellow foam. TLC (19:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.68.

Yield: 217 mg (37%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.56 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.46 (s, 1H), 7.10 (s, 1H), 6.48 (s, 1H), 6.10 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 2H), 6.01 (dddd, J = 17.3, 10.3, 5.7, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 5.39 (dd, J = 17.2, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 5.28 (dd, J = 10.4, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 4.80 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 4H), 3.56 (br s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.3, 152.5, 147.6, 143.1, 142.1, 135.4, 132.4, 131.9, 130.8, 130.1, 118.7, 108.2, 105.5, 103.2, 70.5, 66.1 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C22H19NO9 464.0952, found 464.0939; IR (thin film): ν = 3483, 3086, 2916, 1724, 1523, 1484, 1333, 1260, 1235, 1183, 1036, 986 cm−1.

Diethyl 1,1’-(5-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)isophthaloyl)bis(piperidine-4-carboxylate) (30).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 26 starting from 22 (570 mg, 1.0 mmol) using 1.2 equiv of 6-nitropiperonal. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 2:0→1:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 30 (227 mg, 35%) as a light yellow foam. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.15.

Yield: 227 mg (35%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.43 (s, 2H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 6.14 (s, 2H), 4.48 (br s, 2H), 4.16 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 3.64 (br s, 2H), 3.09 (d, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (br s, 4H), 2.56 (tt, J = 10.1, 5.3 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (br s, 2H), 1.84 (br s, 2H), 1.76 (br s, 2H), 1.65 (br s, 2H), 1.27 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 174.1, 169.4, 152.6, 147.5, 143.5, 142.0, 136.3, 136.1, 126.9, 124.6, 108.1, 105.4, 103.3, 70.5, 60.8, 47.1, 41.7, 41.0, 31.0, 28.6, 27.9 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C32H37N3O11 640.2501, found 640.2486; IR (thin film): ν = 3346, 2930, 2863, 2244, 1727, 1620, 1521, 1482, 1448, 1317, 1257, 1179, 1039, 918 cm−1.

Diallyl 1,1’-(5-(hydroxy(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)isophthaloyl)bis(piperidine-4-carboxylate) (31).

To a solution of 30 (117 mg, 0.18 mmol) in 1.8 mL of a 1:1 1,4-dioxane/water mixture was added LiOH•H2O (30 mg, 0.73 mmol, 4.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min then slowly diluted with 9 mL of 1.0 N HCl and transferred to a separatory funnel containing 10 mL of EtOAc. The organic layer was collected and the aqueous layer was extracted with 2 × 10 mL of EtOAc. The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to a white foam. This material was redissolved in 1.8 mL of DMF and to this solution were added successively i-Pr2NEt (80 μL, 0.46 mmol, 2.5 equiv) and allyl bromide (40 μL, 0.46 mmol, 2.5 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 18 h. Following this time, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 50 mL of saturated aqueous NaHCO3 and transferred to a separatory funnel containing 50 mL of EtOAc. The organic layer was collected and the aqueous layer was extracted with 2 × 50 mL of EtOAc. The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to a yellow oil. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 1:0→0:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 31 (67 mg, 54%) as a light yellow foam. TLC (8:2 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.19.

Yield: 67 mg (54%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.42 (s, 1H), 7.35 (s, 2H), 7.25 (s, 2H), 6.37 (d, J = 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.10 (s, 2H), 5.88 (ddt, J = 16.2, 10.6, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 5.29 (dd, J = 17.2, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 5.22 (dd, J = 10.5, 1.4 Hz, 2H), 4.57 (dd, J = 5.8, 1.6 Hz, 4H), 4.45 (s, 1H), 4.42 (br s, 2H), 3.60 (br s, 2H), 4.99 (br s, 4H), 2.57 (ddt, J = 10.8, 8.5, 3.9 Hz, 2H), 2.00 (br s, 2H), 1.81 (br s, 2H), 1.73 (br s, 2H), 1.63 (br s, 1H), 1.56 (br s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 173.7, 169.3, 152.5, 147.5, 143.6, 141.9, 136.3, 136.2, 132.0, 127.0, 124.6, 118.5, 108.1, 105.4, 103.2, 70.4, 65.4, 47.1, 41.7, 41.0, 28.6, 27.9 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C34H37N3O11 664.2501, found 664.2505; IR (thin film): ν = 3347, 2930, 2863, 2246, 1732, 1622, 1521, 1483, 1317, 1259, 1175, 1036 cm−1.

(1-(6-Nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)ethyl) succinimid-N-yl carbonate (32).

To a solution of 1-(6-nitro-1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)ethanol (15 mg, 70 μmol) in 355 μL of N,N-dimethylformamide was added N,N’-disuccinimidyl carbonate (36 mg, 140 μmol, 2.0 equiv) and Et3N (19.8 μL, 140 μmol, 2.0 equiv). The reaction mixture was stirred for 22 h then diluted with 5 mL of CH2Cl2 and transferred to a separatory funnel containing 5 mL of saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The organic layer was collected and the aqueous layer was extracted with 3 × 5 mL of CH2Cl2. The organic fractions were combined, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 1:0→0:1 hexanes/EtOAc) afforded 32 (29 mg, 99%) as a yellow powder. TLC (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc): Rf = 0.32.

Yield: 29 mg (99%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 7.49 (s, 1H), 7.16 (s, 1H), 6.30 (q, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 2.74 (s, 4H), 1.71 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3CN): δ 170.5, 153.8, 151.8, 149.1, 143.0, 133.0, 106.5, 105.8, 105.1, 76.8, 26.2, 21.7 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C14H12N2O9 375.0435, found 375.0423; IR (thin film): ν = 1789, 1742, 1487, 1506, 1340, 1261, 1235, 1065, 1034 cm−1.

((4-(Morpholine-4-carbonyl)phenyl)(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl) succinimid-N-yl carbonate (33).

To a solution of 23 (50 mg, 0.13 mmol) in 3.2 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide was added N,N’-disuccinimidyl carbonate (66 mg, 0.26 mmol, 2.0 equiv) and Et3N (18 μL, 0.13 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 22 h then diluted with 20 mL of EtOAc and transferred to a separatory funnel containing 20 mL of saturated aqueous NH4Cl. The organic layer was collected and washed successively with 1 × 20 mL of saturated aqueous NaCl and 2 × 20 mL of half-saturated aqueous NaCl. The organic fraction was dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. Purification of this material by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 33 (30 mg, 44%) as a yellow foam. TLC (4:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.53.

Yield: 30 mg (44%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (br s, 4H), 3.62 (br s, 2H), 3.42 (br s, 2H), 2.81 (s, 4H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.7, 168.4, 152.9, 150.8, 148.5, 142.1, 138.0, 136.3, 129.9, 128.1, 127.7, 107.2, 106.0, 103.7, 79.1, 67.0 (2), 48.2, 42.8, 25.6 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H21N3O11 528.1249, found 528.1248; IR (thin film): ν = 2921, 1789, 1743, 1631, 1525, 1486, 1428, 1337, 1263, 1225, 1114, 1034 cm−1.

(4-(tert-Butylcarbamoyl)phenyl)(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl succinimid-N-yl carbonate (34).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 33 starting from 24 (75 mg, 0.2 mmol) using CH3CN in place of N,N-dimethylformamide. Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 100:0→93:7 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 34 (58 mg, 56%) as a neon yellow film. TLC (1:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.38.

Yield: 58 mg (56%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 7.71 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.54 (s, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 6.18 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 5.90 (br s, 1H), 2.81 (s, 4H), 1.46 (s, 9H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 168.5, 166.4, 152.9, 150.8, 148.4, 142.1, 139.0, 136.8, 129.8, 127.8, 127.3, 107.2, 106.0, 103.7, 79.1, 51.9, 28.9, 25.5 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C24H23N3O10 514.1456, found 514.1419; IR (thin film): ν = 3397, 2971, 1790, 1742, 1655, 1526, 1506, 1337, 1266, 1222, 1035 cm−1.

(4-(4-(Ethylcarbonoyl)piperidine-N-carbonyl)phenyl)(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl succinimid-N-yl carbonate (35).

This compound was prepared in an analogous manner to 34 starting from 25 (50 mg, 0.11 mmol). Purification by chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:0→9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone) afforded 35 (28 mg, 43%) as a yellow film. TLC (9:1 CH2Cl2/acetone): Rf = 0.36.

Yield: 28 mg (43%); 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN): δ 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.55 (s, 1H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 6.18 (d, J = 8.8, 2H), 4.50 (br s, 1H), 4.15 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.70 (br s, 1H), 3.05 (br s, 2H), 2.81 (s, 4H), 2.57 (tt, J = 10.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.03 (br s, 1H), 1.86 (br s, 1H), 1.76 (br s, 1H), 1.67 (br s, 1H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H) ppm; 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 174.2, 169.7, 168.4, 152.9, 150.8, 148.4, 137.0, 130.1, 130.0, 128.0, 127.4, 127.1, 107.3, 106.0, 103.7, 79.2, 60.8, 47.0, 41.7, 41.1, 28.6, 28.0, 25.6, 20.3, 14.3 ppm; HRMS (ESI+) m/z: [M + H]+ calcd for C28H27N3O12 598.1667, found 598.1667; IR (thin film): ν = 2927, 1789, 1742, 1629, 1507, 1486, 1428, 1337, 1267, 1224, 1037, 917 cm−1.

(4-(Allylcarbonoyl)phenyl)(6-nitrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl succinimid-N-yl carbonate (36).