Abstract

Introduction:

This study aimed to report the safety and efficacy of off-label intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) with alteplase after sequentially liberalizing our institutional guidelines allowing IVT for patients under direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) regardless of plasma levels, time of last intake, and without prior anticoagulation reversal therapy.

Patients and methods:

We utilized the target-trial methodology to emulate hypothetical criteria of a randomized controlled trial in our prospective stroke registry. Consecutive DOAC patients (06/2021–11/2023) otherwise qualifying for IVT were included. Safety and efficacy outcomes (symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage [ICH], any radiological ICH, major bleeding, 90-day mortality, 90-day good functional outcome [mRS 0–2 or return to baseline]) were assessed using inverse-probability-weighted regression-adjustment comparing patients with versus without IVT.

Results:

Ninety eight patients fulfilled the target-trial criteria. IVT was given in 49/98 (50%) patients at a median of 178 (interquartile range 134–285) min after symptom onset with median DOAC plasma level of 77 ng/ml (15 patients had plasma levels > 100 ng/ml; 25/49 [51%] were treated within 12 h after last DOAC ingestion). Endovascular therapy was more frequent in patients without IVT (73% vs 33%). Symptomatic ICH occurred in 0/49 patients receiving IVT and 2/49 patients without IVT (adjusted difference −2.5%; 95% CI −5.9 to 0.8). The rates of any radiological ICH were comparable. Patients receiving IVT were more likely to have good functional outcomes.

Discussion and conclusion:

After liberalizing our approach for IVT regardless of recent DOAC intake, we did not experience any safety concerns. The association of IVT with better functional outcomes warrants prospective randomized controlled trials.

Keywords: therapeutic thrombolysis, stroke, anticoagulants, atrial fibrillation

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are approved for primary and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. 1 The increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation due to the aging population 2 as well as a continuous expansion of indications (e.g. cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism, and the prevention of major cardiovascular events in patients with stable atherosclerotic disease) constantly increases the number of DOAC prescriptions. 3 It is estimated that at least one in six acute ischemic stroke patients otherwise meeting the criteria for the application of intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) is anticoagulated with a DOAC.4,5 International guidelines mostly recommend against the use of IVT in unselected patients with a DOAC ingestion within 48 h prior to the index event.6,7 This is due to theoretical safety concerns– mainly the fear of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (sICH). 8

Given the lack of a safety signal in preclinical,9–11 preliminary clinical data 12 and no increased risk of sICH in randomized controlled trials with argatroban given in addition to IVT, 13 we sequentially liberalized the approach regarding IVT in patients with recent DOAC intake. Starting from using a plasma-level cut-off of 100 ng/ml in 2021, we began offering IVT to patients with recent DOAC intake based on an individualized risk-benefit assessment regardless of plasma levels, time of last intake or the application of reversal agents in 2023. 14

In this target trial analysis, we aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of those increasingly liberal IVT decisions. According to hypothetical criteria of a randomized controlled trial,15,16 we compared patients with recent DOAC ingestion receiving IVT versus those not receiving IVT. Our hypothesis was that more liberal IVT decisions are not associated with an increase in hemorrhagic complications (sICH) and might lead to better functional outcomes.

Patients and methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective, single-center, observational cohort study. The target-trial methodology15,16 was used to emulate the hypothetical criteria of a randomized controlled trial in the prospective stroke registry of our comprehensive stroke center. There is an approval by the local ethics committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern, 231/14). We used the STROBE guidelines to ensure the appropriate reporting of study results.

Patient selection

Consecutive code stroke patients with an ongoing DOAC prescription presenting to the emergency department of our comprehensive stroke center between June 2021 and November 2023 were retrospectively screened for eligibility. The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) clinical diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke with an indication for IVT according to international guidelines; (2) time from symptom onset/last seen well until admission < 12 h; (3) admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 2 points or more indicating a disabling deficit; (4) DOAC ingestion within 48 h prior to the expected IVT bolus, or patient with an ongoing prescription of DOAC (but the exact time point of last intake was not verifiable in the emergency setting). Patients were excluded for the following criteria: (1) any acute or subacute ICH identified by admission brain scan; (2) any other absolute contraindication for IVT; (3) significant pre-stroke disability defined as an mRS score of 5 or advanced dementia; (4) known sensitivity or previous adverse reaction to alteplase or any of the excipients; (5) pregnancy or lactating women, a negative pregnancy test was required for all women with child-bearing potential (up to 55 years of age). We chose a time window of 12 h from symptom onset/last seen well until admission as we aimed to include patients in an advanced time window as well as wake-up stroke but hoped to limit the likelihood of symptoms being present before the patients went to bed. Two senior stroke neurologists (PB and TRM) screened all patients for eligibility according to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Included patients were divided into two groups: patients receiving IVT versus patients not receiving IVT.

Policy regarding IVT in DOAC patients

IVT (alteplase; 0.9 mg/kg body weight; maximum dosage 90 mg) was administered following our institutional guidelines accompanied by recommended targets for blood pressure, monitoring and avoiding antithrombotics for at least 24 h. During the study period, our local recommendations regarding IVT in patients with recent DOAC intake were adapted: until autumn 2021, IVT was considered an option in case of plasma levels (calibrated anti-IIa-activity for dabigatran; calibrated anti-Xa-activity for apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban) below a threshold of 100 ng/ml. Antagonizing dabigatran (idarucizumab) given plasma levels higher than 100 ng/ml prior to IVT was optional. After autumn 2021, our 2022 institutional guidelines enabled IVT in selected patients with plasma levels above 100 ng/ml: a disabling deficit had to be documented and an expert opinion (stroke neurologist on call) was necessary. The 2024 institutional guidelines (in use since summer 2023) allowed IVT on the basis of an individualized risk – benefit calculation, considering factors such as the presence of a large vessel occlusion directly amenable to endovascular treatment (EVT), clinical deficit, expected efficacy of IVT, time since onset and DOAC dose. DOAC plasma levels were measured, but were not needed for the decision whether or not to perform IVT. 14 While IVT was an option according to these sequentially more liberal criteria, IVT initiation was not compulsory. The final decision was at the discretion of the neurologist on call. This allowed for both proactive and conservative approaches according to the treating physician.

Patient selection for IVT was based on time (<4.5 h after last known well) or imaging criteria in case of a prolonged or unknown time-window.6,7 MRI was the preferred imaging modality (including MR-angiography and MR-perfusion). CT (CT-angiography, CT-perfusion) was chosen in case of MR contraindications. If clinically indicated, EVT was performed. Follow-up imaging (MRI, if possible) was routinely performed at day 1 after the index event as well as in case of any clinical deterioration.

Data collection

Baseline characteristics and the following DOAC-specific information were extracted from the electronic health record: (1) DOAC agent and dosage; (2) time of last ingestion (time known; time not exactly known, but <12 h before onset; time not exactly known, but 12–24 h before onset; time not exactly known, but 24–48 h before onset; time not verifiable in the emergency setting); (3) DOAC plasma levels (ng/ml). Imaging findings were extracted from the written neuroradiological reports: (1) location of the vessel occlusion (if applicable); (2) Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS; in case of CT), DWI-ASPECTS (MRI patients) or posterior circulation ASPECTS for patients with vertebrobasilar stroke; (3) age-related white matter changes scale to quantify white matter disease (Fazekas et al. scale).17–20

Outcome measures

The primary binary safety outcome variable was sICH according to the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III) and The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group criteria (NINDS).21,22 Secondary safety outcomes included any radiological ICH until 36 h after IVT according to the Heidelberg classification (no hemorrhagic transformation; hemorrhagic transformation type 1 and type 2; parenchymal hemorrhage type 1 and type 2; subarachnoid hemorrhage), 23 major bleeding (see Supplemental Table S1 for definitions) 24 and the development of orolingual edema.

The secondary efficacy outcome was good functional outcome defined as a score of 2 or less on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 90 days or return to baseline mRS. The follow-up was assessed by a stroke neurologist during a clinical visit.

In addition, outcome variables were collected for all DOAC patients receiving IVT. Therefore, (safety) data on patients that were thrombolyzed outside the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria could be analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Medians (interquartile ranges (IQRs)) or means (standard deviation (SD)) were used to present the distribution of ordinal, continuous, and categorical variables. We compared baseline characteristics across groups using the Pearson chi-squared test for categorical variables and Student’s T-test or the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate, for continuous and ordinal variables.

For safety and efficacy outcomes, we used the inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) method to minimize the confounding effects of baseline NIHSS (continuous), age (continuous), EVT (binary), and significant differences in baseline characteristics. 25 IPTW was applied using stabilized weights to adjust for the above-mentioned covariates to minimize the imbalance between the groups in the propensity scores. 26 Due to an expected imbalance in baseline characteristics (e.g. NIHSS, large vessel occlusion), a pre-specified sensitivity analysis regarding safety and efficacy outcomes was conducted in patients not eligible for EVT. Adjusted differences (percentages) for IVT versus no IVT were reported with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). Complete case analysis was used and all p-values are two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant without adjustments for multiple testing. With this pilot safety data, we wanted to exclude an intolerable excess of sICH with liberal IVT decisions in DOAC patients. We thus calculated with the current rate of sICH at our center in non-DOAC IVT patients (2%) and a non-inferiority margin of 7% (alpha 0.05, power 80%) yielding a sample size of 100 patients.

Results

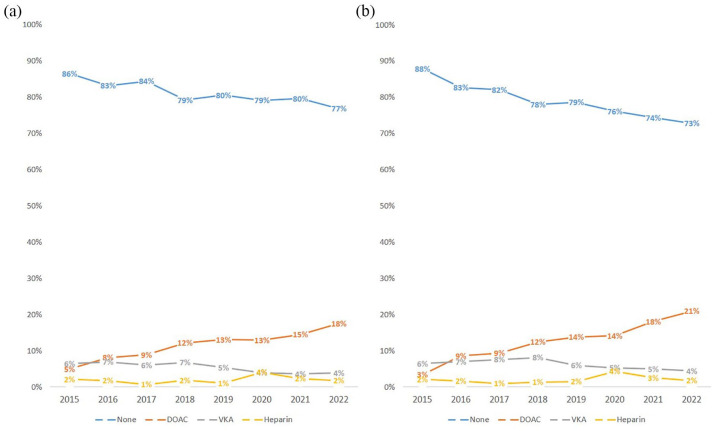

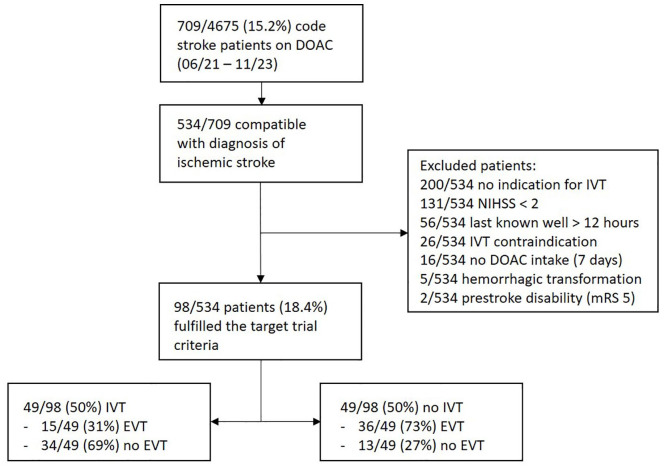

Between June 2021 and November 2023, 709/4675 (15.2%) of code stroke patients were on a DOAC with increasing rates over time (Figure 1). Of these 709 patients, 534 were compatible with the diagnosis of ischemic stroke and were checked for eligibility. Out of those, 98/534 (18.4%) patients could be included: 49/98 (50%) patients received IVT, while 49/98 (50%) did not receive IVT (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Yearly distribution (2015–2022) of the spectrum of preceding anticoagulation in: (a) all code stroke patients and (b) those with a minimum NIHSS of 4 points at our comprehensive stroke center. Note the overall decrease in patients without anticoagulation. This is due to an increase of patients on DOACs since patients on VKA were also declining over time. Patients with parenteral anticoagulation (heparins) represent a minority of all patients on anticoagulation. DOAC: direct oral anticoagulants; VKA: vitamin-K antagonists.

Figure 2.

Study flowchart.

Demographic and baseline characteristics are shown in the online supplement (table S2). The median age was 82 (IQR 76–88) years, 46% were female, with no significant differences between groups. Patients with versus without IVT did not differ in the rate of cardiovascular risk factors or imaging findings such as (posterior circulation) ASPECTS or white matter hyperintensities. The median baseline NIHSS was higher in no IVT patients (10 [IQR 6–18] vs 6 [IQR 3–10]; p < 0.001. No IVT patients had more often large vessel occlusions (63% vs 31% for IVT patients; p = 0.001) and EVT was more frequently performed (73% vs 33%; p < 0.001).

DOAC levels were available in 46/49 patients in each group. The overall median DOAC plasma level was 93 ng/ml. It was lower in IVT versus no IVT patients (77 ng/ml vs 125 ng/ml; p = 0.008). Of the 49 patients receiving IVT, 15 (31%) had a plasma level of >100 ng/ml. Last documented in take was reported within 12 h for 25/49 (51%) and within 24 h for 40/49 (82%) patients. No specific or unspecific reversal agents were applied prior to IVT. DOAC specific information of both groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

DOAC-specific baseline characteristics.

| Overall | No IVT | IVT | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of DOAC (n [%]) | ||||

| Apixaban | 53 (54) | 29 (59) | 24 (49) | 0.31 |

| Edoxaban | 6 (6) | 2 (4) | 4 (8) | |

| Rivaroxaban | 38 (39) | 17 (35) | 21 (43) | |

| Dabigatran | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Last DOAC intake (n [%]) (h) | ||||

| <12 | 53 (54) | 28 (57) | 25 (51) | 0.70 |

| <24 | 85 (87) | 45 (92) | 40 (82) | 0.22 |

| <48 | 92 (94) | 47 (96) | 45 (92) | 0.15 |

| Blood sample analysis (mean [IQR]) | ||||

| DOAC plasma levels (ng/ml) | 93 (53–154) | 125 (63–191) | 77 (47–117) | 0.01 |

DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant; IVT: intravenous thrombolysis; IQR: interquartile range; INR: international normalized ratio.

The primary outcome was assessable in all 98 patients. None of the 49 patients experienced sICH (ECASS-III criteria) after IVT versus 2/49 (4.1%) without IVT (adjusted difference for IVT −2.5%; 95% CI −5.9 to 0.8). sICH (NINDS criteria) was observed in 1/49 (2%) IVT patients versus 4/47 (9%) without IVT (adjusted difference for IVT −3.9%; 95% CI −9.7 to 1.8). The rates of any radiological ICH did not differ between IVT versus no IVT (Table 2). We observed no orolingual edema and no major bleeding after IVT.

Table 2.

Safety and efficacy outcomes.

| IVT versus not IVT |

IVT versus no IVT (no indication for EVT) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVT | No IVT | Adjusted difference (%, 95% CI) | IVT | No IVT | Adjusted difference (%, 95% CI) | |

| Number (%) | 49 (50) | 49 (50) | 34 (72) | 13 (28) | ||

| Safety outcomes (n [%]) | ||||||

| sICH (ECASS III) | 0/49 (0) | 2/49 (4) | −2.5 (−5.9 to +0.8) | 0/34 (0) | 0/13 (0) | n.a. |

| sICH (NINDS) | 1/48 (2) | 4/47 (9) | −3.9 (−9.7 to +1.8) | 1/33 (3) | 0/11 (0) | 3.1 (−2.8 to +9.0) |

| Any radiological ICH | ||||||

| HI 1 | 3/48 (6) | 3/47 (6) | −10.2 (−61.7 to +41.2) | 3/33 (9) | 0/11 (0) | 56.3 (21.8 to 90.8) |

| HI 2 | 7/48 (15) | 1/47 (2) | 4/33 (12) | 0/11 (0) | ||

| PH 1 | 1/48 (2) | 2/47 (4) | 1/33 (3) | 0/11 (0) | ||

| PH 2 | 1/48 (2) | 4/47 (9) | 1/33 (3) | 0/11 (0) | ||

| SAH | 0/48 (0) | 5/47 (11) | 0/33 (0) | 0/11 (0) | ||

| Any major bleeding | 0/48 (0) | 3/47 (6) | −4.4 (−9.5 to +0.5) | 0/33 (0) | 0/13 (0) | n.a. |

| Mortality (90 days) | 5/49 (10) | 19/49 (39) | −16.4 (−37.5 to +4.7) | 3/34 (9) | 4/13 (31) | −18.9 (−40.1 to +2.2) |

| Efficacy outcome (n [%]) | ||||||

| mRS 0–2 (90 days) | 39/48 (81) | 13/47 (28) | 56.7 (39.8 to 73.6) | 26/33 (79) | 2/12 (17) | 61.4 (36.8–86.1) |

IVT: intravenous thrombolysis; EVT: endovascular therapy; CI: confidence interval; (s)ICH, (symptomatic) intracranial hemorrhage; ECASS III: European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III; NINDS: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; HI: hemorrhagic transformation; PH: parenchymal hemorrhage; SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage; n.a.: not applicable; mRS: modified Rankin Scale.

Mortality at 90 days was numerically lower in IVT (5/49 [10%]) versus no IVT (19/49 [39%]) (adjusted difference −16.4%; 95% CI −37.5 to 4.7). Good outcome was more frequent in IVT 39/48 (81%) versus no IVT 13/47 (28%); adjusted difference for IVT + 56.7%; 95% CI 39.8–73.6).

In addition to the 49 patients receiving IVT within this target trial analysis, 11 further patients with recent DOAC intake received IVT (2 not clearly disabling, 7 presenting >12 h after last known well, 1 pre-stroke mRS 5 and 1 with another contraindication). Of those, 1/56 (1.8%) suffered sICH (ECASS-III criteria). This patient had a plasma level of 93 ng/ml and presented >12 h after last known well. About 2/50 patients (4%) experienced sICH according to the NINDS criteria). Patient characteristics are presented in the online supplement (Table S3).

Subgroup analysis excluding EVT patients

Overall, 47/98 (48%) patients were not eligible for EVT. Out of those, 34/47 (72%) received IVT, 13/47 (28%) did not receive IVT. Baseline characteristics (IVT vs no IVT) did not differ (online supplement; Tables S4 and S5). There was no sICH (ECASS-III) in the entire subgroup of patients without indication for EVT (Table 2). According to NINDS, 1/31 (3.2%) in the IVT group versus 0/11 patients in the no IVT group (+3.1%; 95% CI −2.8 to 9.0) had sICH. Any radiological ICH was more frequent after IVT (adjusted difference + 56.3%; 95% CI 21.8–90.8). There was a higher rate of good functional outcome in the IVT group (26/33 [79%]) vs the no IVT group (2/12 [17%]). The adjusted difference in good functional outcome for IVT was +61.4% (95% CI 36.8–86.1).

Discussion

There is an increasing rate of DOAC-pretreatment in patients otherwise qualifying for IVT. After consecutively liberalizing our approach offering IVT to patients with recent DOAC intake, we found no safety concerns associated with off-label IVT regarding sICH or mortality. IVT patients experienced higher rates of good functional outcomes.

According to current international guideline recommendations, the beneficial effect of a safe application of IVT has to be withheld from the majority of DOAC patients.6,7,27–29 These recommendations are based on the presumption of an increase in harmful hemorrhagic complications. 30 Higher bleeding risks observed in patients anticoagulated with VKAs are subsequently extrapolated on DOAC patients.8,30 However, experimental studies suggest that VKAs and DOACs differ in terms of hemorrhagic complications.9–11,31,32 Preliminary clinical data support this assumption.12,33 In our cohort, there was no sICH after IVT in DOAC patients. Overall, IVT versus no IVT did not differ in terms of sICH, major bleeding or any radiological ICH. Besides higher DOAC levels in patients without IVT, cardiovascular risk factors, time of last DOAC intake (<12 h prior to IVT in more than 50% of patients) or imaging findings such ASPECTS or white matter hyperintensities were comparable. Pathophysiological explanations for these observations have to remain speculative. Liu et al. 34 hypothesized that both direct or indirect thrombin inhibition might minimize disruptions of the blood–brain barrier and thus reduce the risk of hemorrhage. Likewise, IVT combined with argatroban – a direct thrombin inhibitor – was not associated with increased odds of sICH in a Phase II trial. 35 These results were confirmed in the Multi-arm Optimization of Stroke Thrombolysis (MOST) trial as presented at the International Stroke Conference 2024 (Phoenix, Arizona, USA). It is of note that in patients not eligible for EVT, any radiological ICH was more frequent after IVT. Yet, the overall rate of any radiological ICH is comparable to the available literature analyzing follow-up brain imaging after IVT in patients without anticoagulation. 36

Selection strategies aiming to identify candidates for IVT remain controversial and are limited by availability. 37 The use of reversal agents prior to IVT was shown to be feasible in retrospective cohorts and case reports.38,39 DOAC plasma level measurement was suggested as an alternative approach. While some authors consider IVT in plasma levels <30 ng/ml to be safe, others opt for thresholds <50 ng/ml with individualized approaches in plasma levels up to 100 ng/ml.40,41 The median plasma concentration in a recent publication supporting the safety of DOAC IVT was below the above-mentioned cut-offs (21 ng/ml). 12 In our study, the median DOAC plasma level in IVT patients was within the assumed therapeutic range (77 ng/ml; maximum activity level 334 ng/ml). In accordance with the published literature, we could not observe an excess of harm.

Available publications on off-label IVT in DOAC patients focused on safety outcomes. Data on potentially beneficial effects of IVT in this patient population are scarce. In a meta-analysis by Behnoush et al., 42 DOAC patients receiving IVT were at a higher risk of functional dependence compared to patients without anticoagulation. However, the lack of information on (assumed differences in) baseline characteristics and stroke severity makes an interpretation difficult. In contrast, adjusted analyses reported by Kam et al. 4 suggest better functional outcomes for IVT in DOAC patients (vs IVT without DOAC). In our cohort, good functional outcome was more frequent in patients receiving IVT. It is of note that baseline NIHSS and the presence of a large vessel occlusion were significantly higher in the no IVT group. This reflects our internal guidelines highlighting direct EVT in case of an expected groin puncture within 30 min after confirmed large vessel occlusions. 14 Analyzing patients without EVT only, the adjusted difference in functional outcome (in favor of IVT vs no IVT) did not change.

Our results emphasize the need of a randomized controlled trial addressing the question of IVT in patients with recent DOAC intake. We did not experience safety concerns even in case of very recent DOAC ingestion and in the presence of therapeutic plasma levels. Until the results of such a trial can be expected, the question arises whether – unlike in myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism – IVT should remain an absolute contraindication in DOAC patients.43,44

This study has limitations. First, due to the retrospective design, all associated biases apply. While these might have been reduced by the target trial methodology, we cannot exclude that other factors might have prompted the decision whether or not to perform IVT. However, the only identifiable arguments for not giving IVT were (1) DOAC with recent intake, and (2) DOAC with therapeutic plasma levels. We could not detect specific medical conditions associated with the decision against IVT in our records. Differences in the mortality rate (numerically higher in no IVT patients) suggest bias by indication. Second, the single center design may limit generalizability. Third, due to sample size limitations, we were unable to perform relevant subgroup analyses (e.g. patients with DOAC plasma levels above 100 ng/ml). Finally, there was a higher rate of large vessel occlusions (associated with a higher NIHSS and subsequent EVT) in no IVT patients. While IPTW matching and a subgroup analysis excluding EVT patients were performed, we cannot exclude that this imbalance might have influenced our results.

Conclusion

After the liberalization of our internal approach to provide IVT regardless of recent DOAC intake or DOAC plasma levels, we did not experience any safety concerns. The association of IVT with better functional outcomes warrants prospective randomized controlled trials.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-eso-10.1177_23969873241252751 for Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with recent intake of direct oral anticoagulants: A target trial analysis after the liberalization of institutional guidelines by Philipp Bücke, Simon Jung, Johannes Kaesmacher, Martina B Goeldlin, Thomas Horvath, Ulrike Prange, Morin Beyeler, Urs Fischer, Marcel Arnold, David J Seiffge and Thomas R Meinel in European Stroke Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241252751 for Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with recent intake of direct oral anticoagulants: A target trial analysis after the liberalization of institutional guidelines by Philipp Bücke, Simon Jung, Johannes Kaesmacher, Martina B Goeldlin, Thomas Horvath, Ulrike Prange, Morin Beyeler, Urs Fischer, Marcel Arnold, David J Seiffge and Thomas R Meinel in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: MBG reports grants from the Bangerter-Rhyner-Foundation, Swiss Stroke Society, European Stroke Organisation, European Academy of Neurology and Insel Gruppe AG (all outside the submitted work). MA reports speaker honoraria from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Covidien, Medtronic, Sanofi and honoraria for scientific advisory boards from Amgen, Bayer, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Medtronic, Pfizer, and research funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), and the Swiss Heart Foundation (SHF). UF reports financial support for the SWIFT DIRECT trial (Medtronic), research grants from Medtronic BEYOND SWIFT registry, SNSF, SHF, consulting fees from Medtronic, Stryker and CSL Behring (fees paid to institution); membership of a Data Safety Monitoring Board for the IN EXTREMIS trial and TITAN trial and Portola (Alexion) Advisory board (fees paid to institution). DS is on the advisory board of Bayer Switzerland AG and Portola/Alexion. He reports research funding from SNSF, SHF, Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, Bayer Foundation, and Portola/Alexion. TRM reports grants from the Bangerter-Rhyner Foundation, the Baasch-Medicus Foundation, the University of Bern, the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Heart Foundation. All other authors report no competing interests.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: There is an approval by the local ethics committee (Kantonale Ethikkommission Bern, 231/14).

Informed consent: According to the regulations of the Swiss Stroke Registry and the ethics committee, no informed consent was required.

Guarantor: PB

Contributorship: PB and TRM conceived the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. SJ, JK, MBG, TH, UP, MB, UF, MA and DJS reviewed and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Philipp Bücke  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5204-2016

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5204-2016

Morin Beyeler  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5911-7957

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5911-7957

Urs Fischer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0521-4051

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0521-4051

David J Seiffge  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3890-3849

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3890-3849

Thomas R Meinel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0647-9273

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0647-9273

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 2014; 383: 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Di Carlo A, Bellino L, Consoli D, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the Italian elderly population and projections from 2020 to 2060 for Italy and the European union: the FAI project. Europace 2019; 21: 1468–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moras E, Gandhi K, Khan M, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants: an overview of indications, pharmacokinetics, comorbidities, and perioperative management. Cardiol Rev Epub ahead of print 27 September 2023. DOI: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kam W, Holmes D, Hernandez A, et al. Association of recent use of non–Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants with intracranial hemorrhage among patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with alteplase. JAMA 2022; 327: 760–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meinel TR, Branca M, De Marchis GM, et al. Prior anticoagulation in patients with ischemic stroke and atrial fibrillation. Ann Neurol 2021; 89: 42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019; 50: E344–E418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, et al. European stroke organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J 2021; 6: I–LXII. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xian Y, Liang L, Smith EE, et al. Risks of intracranial hemorrhage among patients with acute ischemic stroke receiving warfarin and treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. JAMA 2012; 307: 2600–2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ploen R, Zorn M, Sun L, et al. Anticoagulation with dabigatran does not increase secondary intracerebral haemorrhage after thrombolysis in experimental cerebral ischaemia. Thromb Haemost 2013; 110: 153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kono S, Yamashita T, Deguchi K, et al. Rivaroxaban and apixaban reduce hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolysis by protection of neurovascular unit in rat. Stroke 2014; 45: 2404–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ploen R, Sun L, Zhou W, et al. Rivaroxaban does not increase hemorrhage after thrombolysis in experimental ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 34: 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meinel T, Wilson D, Gensicke H, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with ischemic stroke and recent ingestion of direct oral anticoagulants. JAMA Neurol 2023; 80: 233–243. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen HS, Cui Y, Zhou ZH, et al. Effect of argatroban plus intravenous alteplase vs intravenous alteplase alone on neurologic function in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the ARAIS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2023; 329: 640–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jung S, Meinel T, Bern T. Stroke Guidelines of the Bern Stroke Network, https://www.google.com/search?q=Stroke_Richtlinien_2024_EN_20240326.pdf+(insel.ch)&oq=Stroke_Richtlinien_2024_EN_20240326.pdf+(insel.ch)&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOdIBBzM2MmowajSoAgCwAgE&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 (2024, accessed 15 March 2024).

- 15. Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available: Table 1. Am J Epidemiol 2016; 183: 758–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hernán MA, Sauer BC, Hernández-Díaz S, et al. Specifying a target trial prevents immortal time bias and other self-inflicted injuries in observational analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 79: 70–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, et al. Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome of hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. ASPECTS study group. Alberta stroke programme early CT score. Lancet 2000; 355: 1670–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sang H, Li F, Yuan J, et al. Values of baseline posterior circulation acute stroke prognosis early computed tomography score for treatment decision of acute basilar artery occlusion. Stroke 2021; 52: 811–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoshimoto T, Inoue M, Yamagami H, et al. Use of diffusion-weighted imaging-Alberta stroke program early computed tomography score (DWI-ASPECTS) and ischemic core volume to determine the malignant profile in acute stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2019; 8: e012558–e012559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fazekas F, Chawluk J, Alavi A, et al. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer’s dementia and normal aging. Am J Roentgenol 1987; 149: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 2008; 359: 1317–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. New Engl J Med 1999; 341: 1240–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. von Kummer R, Broderick JP, Campbell BC, et al. The heidelberg bleeding classification: classification of bleeding events after ischemic stroke and reperfusion therapy. Stroke 2015; 46: 2981–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005; 3: 692–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol 2006; 163: 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chesnaye NC, Stel VS, Tripepi G, et al. An introduction to inverse probability of treatment weighting in observational research. Clin Kidney J 2022; 15: 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zi W, Qiu Z, Li F, et al. Effect of endovascular treatment alone vs intravenous alteplase plus endovascular treatment on functional independence in patients with acute ischemic stroke: the DEVT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021; 325: 234–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LeCouffe NE, Kappelhof M, Treurniet KM, et al. Trial of intravenous alteplase before endovascular treatment for stroke. New Engl J Med 2022; 386: 496–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Turc G, Tsivgoulis G, Audebert HJ, et al. European stroke organisation - European society for minimally invasive neurological therapy expedited recommendation on indication for intravenous thrombolysis before mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischaemic stroke and anterior circulation large vessel occlusion. Eur Stroke J 2022; 7: I–XXVI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mazya MV, Lees KR, Markus R, et al. Safety of intravenous thrombolysis for ischemic stroke in patients treated with warfarin. Ann Neurol 2013; 74: 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pfeilschifter W, Bohmann F, Baumgarten P, et al. Thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator under dabigatran anticoagulation in experimental stroke. Ann Neurol 2012; 71: 624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pfeilschifter W, Spitzer D, Czech-Zechmeister B, et al. Increased risk of hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke occurring during warfarin anticoagulation: an experimental study in mice. Stroke 2011; 42: 1116–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shahjouei S, Tsivgoulis G, Goyal N, et al. Safety of intravenous thrombolysis among patients taking direct oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2020; 51: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu DZ, Ander BP, Xu H, et al. Blood-brain barrier breakdown and repair by SRC after thrombin-induced injury. Ann Neurol 2010; 67: 526–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barreto AD, Ford GA, Shen L, et al. Randomized, multicenter trial of ARTSS-2 (argatroban with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute stroke). Stroke 2017; 48: 1608–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schurig J, Haeusler KG, Grittner U, et al. Frequency of hemorrhage on follow up imaging in stroke patients treated with rt-PA depending on clinical course. Front Neurol 2019; 10: 368–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seiffge DJ. Intravenous thrombolytic therapy for treatment of acute ischemic stroke in patients taking non–Vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants. JAMA 2022; 327: 725–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kermer P, Eschenfelder CC, Diener HC, et al. Antagonizing dabigatran by idarucizumab in cases of ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage in Germany – a national case collection. Int J Stroke 2020; 15: 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Karaszewski B, Szczyrba S, Jabłoński B, et al. Case report: first treatment of acute ischaemic stroke in a patient on active rivaroxaban therapy using andexanet alfa and rtPA combined with early complete recovery. Front Neurol 2023; 14: 1269651. DOI: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1269651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Marsch A, Macha K, Siedler G, et al. Direct oral anticoagulant plasma levels for the management of acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2019; 48: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ebner M, Birschmann I, Peter A, et al. Limitations of specific coagulation tests for direct oral anticoagulants: a critical analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2018; 7: e009807–e009811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Behnoush AH, Khalaji A, Bahiraie P, et al. Meta-analysis of outcomes following intravenous thrombolysis in patients with ischemic stroke on direct oral anticoagulants. BMC Neurol 2023; 23: 440–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the task force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 119–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European respiratory society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 543–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-eso-10.1177_23969873241252751 for Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with recent intake of direct oral anticoagulants: A target trial analysis after the liberalization of institutional guidelines by Philipp Bücke, Simon Jung, Johannes Kaesmacher, Martina B Goeldlin, Thomas Horvath, Ulrike Prange, Morin Beyeler, Urs Fischer, Marcel Arnold, David J Seiffge and Thomas R Meinel in European Stroke Journal

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241252751 for Intravenous thrombolysis in patients with recent intake of direct oral anticoagulants: A target trial analysis after the liberalization of institutional guidelines by Philipp Bücke, Simon Jung, Johannes Kaesmacher, Martina B Goeldlin, Thomas Horvath, Ulrike Prange, Morin Beyeler, Urs Fischer, Marcel Arnold, David J Seiffge and Thomas R Meinel in European Stroke Journal