Abstract

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most frequent inherited bleeding disorder, with an estimated symptomatic prevalence of 1 per 1000 in the general population. VWD is characterized by defects in the quantity, quality, or multimeric structure of von Willebrand factor (VWF), a glycoprotein being hemostatically essential in circulation. VWD is classified into 3 principal types: low VWF/type 1 with partial quantitative deficiency of VWF, type 3 with virtual absence of VWF, and type 2 with functional abnormalities of VWF, being classified as 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N. A new VWD type has been officially recognized by the ISTH SSC on von Willebrand factor which has also been discussed by the joint ASH/ISTH/NHF/WFH 2021 guidelines (ie, type 1C), indicating patients with quantitative deficiency due to an enhanced VWF clearance. With the advent of next-generation sequencing technologies, the process of genetic diagnosis has substantially changed and improved accuracy. Therefore, nowadays, patients with type 3 and severe type 1 VWD can benefit from genetic testing as much as type 2 VWD. Specifically, genetic testing can be used to confirm or differentiate a VWD diagnosis, as well as to provide genetic counseling. The focus of this manuscript is to discuss the current knowledge on VWD molecular pathophysiology and the application of genetic testing for VWD diagnosis.

Keywords: genetic testing, molecular diagnosis, NGS, VWD, VWF

1 |. INTRODUCTION

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most frequent inherited bleeding disorder, with an estimated symptomatic prevalence of 1 per 1000 in the general population [1–3]. A recent genetic epidemiologic population-based study newly estimated the possible prevalence as being even more than 10 times higher based on VWF gene variant frequencies [4]. VWD is characterized by defects in the quantity, quality, or multimeric structure of von Willebrand factor (VWF), a glycoprotein being hemostatically essential in circulation [5]. Most common bleeding manifestations of this condition include nosebleeds, bruising, bleeding from minor wounds, and menorrhagia or postpartum bleeding in women and bleeding after surgery. Other less frequent bleeding symptoms include gastrointestinal bleeding, hematomas or hemarthroses, and central nervous system bleeding [5–7]. VWD is classified into 3 principal types: low VWF/type 1 with partial quantitative VWF deficiency, type 3 with the virtual absence of VWF, and type 2 with functional abnormalities of VWF, being further classified as 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N [5]. A new VWD type has been officially recognized by the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) SSC on von Willebrand factor (ie, type 1C). It was also discussed by the joint 2021 VWD guidelines of the American Society of Hematology (ASH), the ISTH, the National Hemophilia Foundation (NHF), and the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) to identify patients with quantitative deficiency due to an enhanced VWF plasma clearance [8,9]. The focus of this manuscript is to discuss the current knowledge on VWD molecular pathophysiology and the application of genetic testing for VWD diagnosis.

2 |. VWF GENE AND PROTEIN

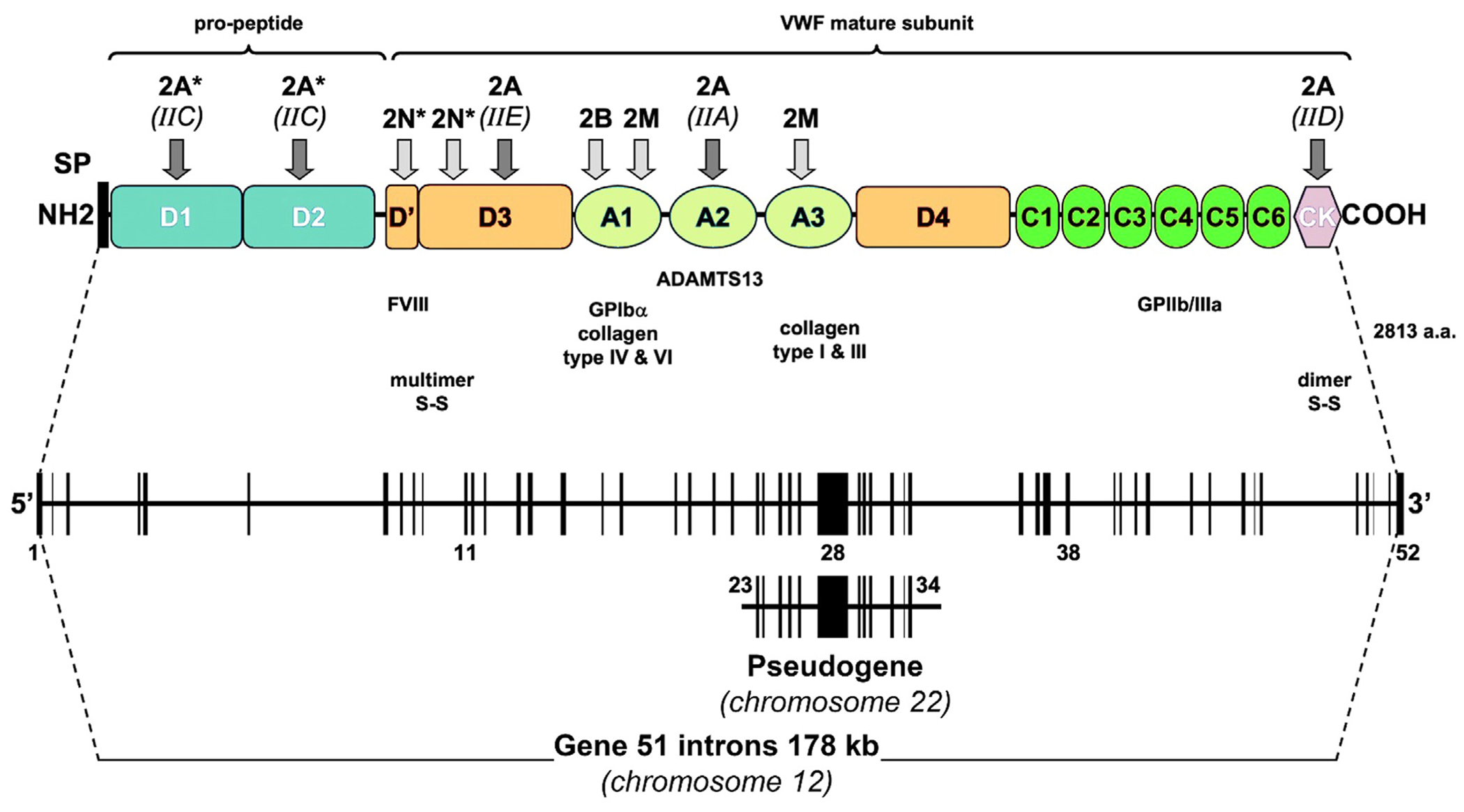

The VWF gene (VWF) is located on the short arm of chromosome 12 (12p13.2), contains 178 kb of genomic DNA and consists of 52 exons ranging in size from 40 to 1379 bases [10,11]. A partial nontranscribed VWF pseudogene is present in chromosome 22q11.2, spanning 25 kb, and has 97% sequence homology with exons 23 to 34 of VWF [11]. The transcriptionally expressed messenger RNA of VWF is approximately 8.7 kb in length (Figure 1). Initially, VWF is synthesized from a 2813-amino acid (aa) prepromonomer that contains 22 aa as a signal peptide, 741 aa as propeptide VWF (VWFpp), and 2050 aa as the mature subunit (Figure 1). Before secretion, pro-VWF undergoes a series of posttranslational modifications, including dimerization, multimerization, N- and O-glycosylation, sialylation, and sulfation, to form a fully functional protein with high-molecular-weight multimers (HMWM) [12]. Pro-VWF is composed of the following repeated domains: D1-D2 (VWFpp) -D’-D3-A1-A2-A3-D4-C1-C2-C3-C4-C5-C6-CK (mature subunit; Figure 1) [12,13]. VWF, as an adhesive glycoprotein, has multiple functional interactions with a wide range of ligands. These interactions include the D’-D3 domains interacting with coagulation factor (F)VIII, the A1 domain interacting with platelet glycoprotein Ib alpha (GPIbα) receptor and collagens IV and VI, and the A3 domain interacting with collagens I and III (Figure 1) [14,15]. Therefore, VWF is essential for both primary (platelet-mediated) and secondary (coagulation-mediated) hemostasis [16].

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) gene, pseudogene, and protein precursor. A schematic representation of the pre-pro-VWF is presented along with its homologous repeated domain. Disulfide bonds between subunits that are involved in dimerization and multimerization are shown along with ligand binding sites. The arrows indicate the major location of mutations that cause various type 2 von Willebrand disease. Recessive type 2 von Willebrand disease variants are shown by an asterisk (*). ADAMTS13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 13; FVIII, factor VIII; GP, glycoprotein; SP, signal peptide.

3 |. GENETIC CHARACTERIZATION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF TYPE 1 VWD

Type 1 VWD, caused by mild to moderately severe quantitative VWF deficiency, is the most common type, comprising about 60% to 70% of cases [5]. However, with the introduction of the “low VWF” category, the proportion of type 1 VWD cases has decreased, perhaps to 40% to 50% of all VWD cases (see below). This type is characterized by proportionately decreased levels of VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) and activities (platelet-dependent VWF activity and VWF collagen binding [VWF:CB]) and a normal multimeric structure (Table 1) [5]. However, in some type 1 patients, minor multimer abnormalities might be present depending on the sensitivity of the multimer analysis and/or the expertise of the testing laboratory [17]. Establishing a mild type 1 VWD diagnosis from normal is challenging due to several contributing factors, such as natural variations in VWF plasma levels caused by environmental/acquired (eg, exercise, thyroid hormones, estrogens, and aging) and genetic (ABO blood types) influences. For example, VWF levels are 25% to 30% lower in individuals with blood group O compared with those with other blood types [18,19]. Besides, the lack of a clear diagnostic cutoff value for VWF levels and a complex VWD diagnostic panel have further complicated type 1 diagnosis until recently, when the joint ASH/ISTH/NHF/WFH 2021 guidelines helped to clarify the diagnosis of type 1 VWD [8]. Accordingly, type 1 is considered when the VWF level is <30 International Units (IU)/dL regardless of bleeding and in patients with a VWF level of <50 IU/dL but with abnormal bleeding [8].

TABLE 1.

Current classification of von Willebrand disease.

| Type | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1 | Quantitative decrease in VWF with preserved ratios between VWF:Ag, VWF activity, and FVIII:C; normal multimer distribution. |

| 1C | Quantitative decrease in VWF with preserved ratios between VWF:Ag, VWF activity, and FVIII:C; normal multimer distribution; increased VWF clearance. |

| 2A | Decreased VWF-dependent platelet adhesion with loss of high-molecular-weight multimers. |

| 2B | Increased binding of VWF to GPIbα, often leading to thrombocytopenia. |

| 2M | Decreased VWF-dependent platelet adhesion with preserved multimer pattern. |

| 2N | Decreased binding of VWF to FVIII. |

| 3 | Absence or near absence of VWF. |

VWF-dependent platelet adhesion refers to both VWF-GPIbα and VWF collagen binding activities.

FVIII, factor VIII; FVIII:C, factor VIII clotting activity; GPIbα, glycoprotein Ib alpha; VWF, von Willebrand factor; VWF:Ag, VWF antigen.

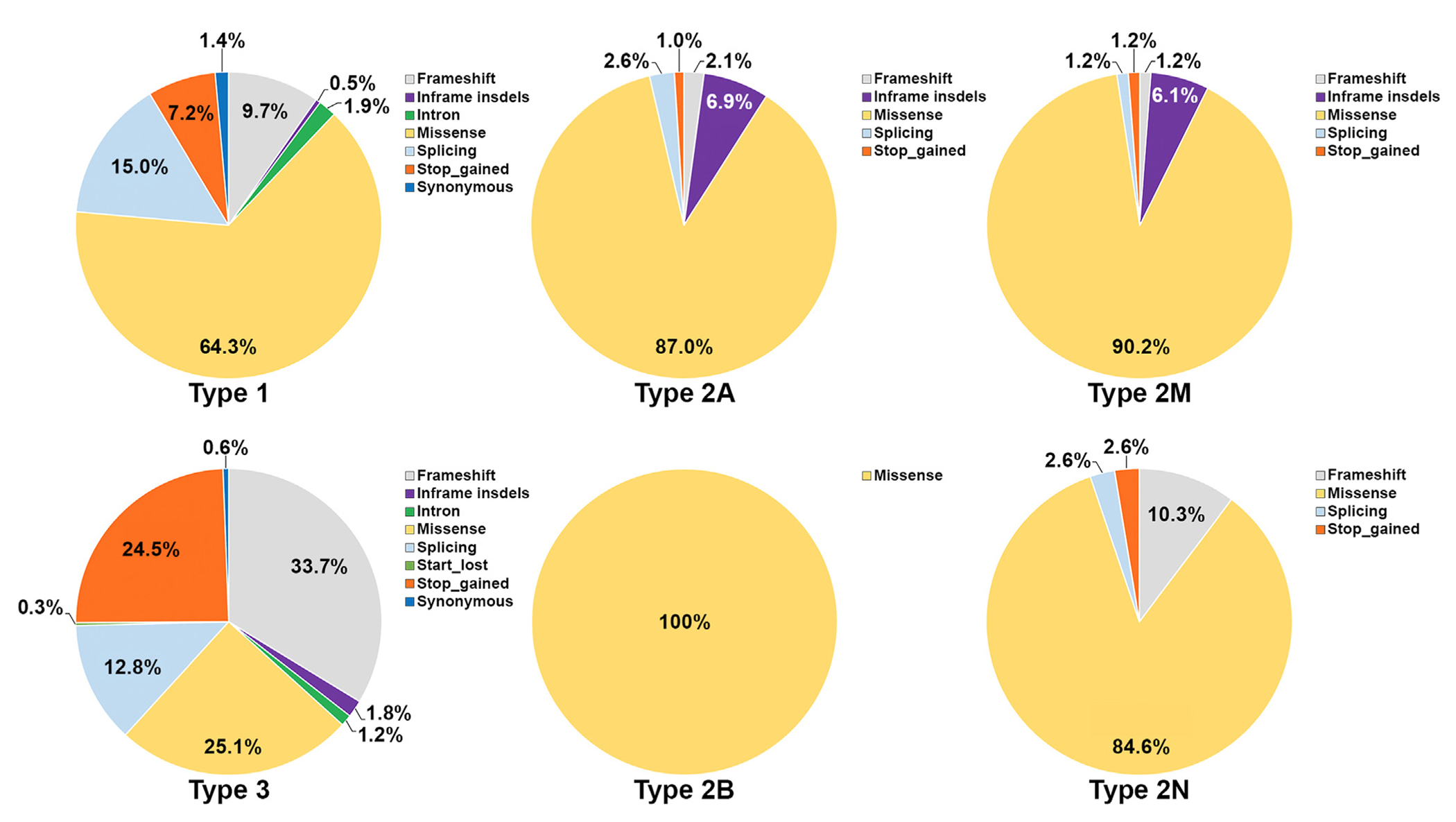

Our understanding of type 1 VWD, particularly its genetic basis and etiology, has improved significantly through molecular epidemiologic studies of more than 800 index cases over the past 2 decades [20–31]. Almost 250 different VWF variants have been reported to be associated with type 1 VWD [4], mainly missense (64%), followed by splicing (15%) variants. Frameshift, in-frame indels, intronic, stop-gain, and synonymous variants were also reported (Figure 2). Variants identified in patients with type 1 with severely reduced VWF levels are usually fully penetrant. Investigation of several large cohorts of VWD patients indicated that it is more likely to detect pathogenic VWF variants in type 1 cases with lower VWF levels. Approximately 80% to 90% of patients carried pathogenic VWF variants when the VWF level was <30 IU/dL [25,29], in contrast to cases with a VWF level of 30 to 50 IU/dL in whom only 50% to 60% have evidence of VWF variants [25,32]. This highlights the fact that type 1 VWD represents a complex genetic trait with heterogeneity at both allelic and locus levels.

FIGURE 2.

Type of von Willebrand factor genetic variants stratified for each von Willebrand disease type. The majority of types 1, 2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N variants reported so far are missense, differently from type 3 von Willebrand disease with only 25% missense variants.

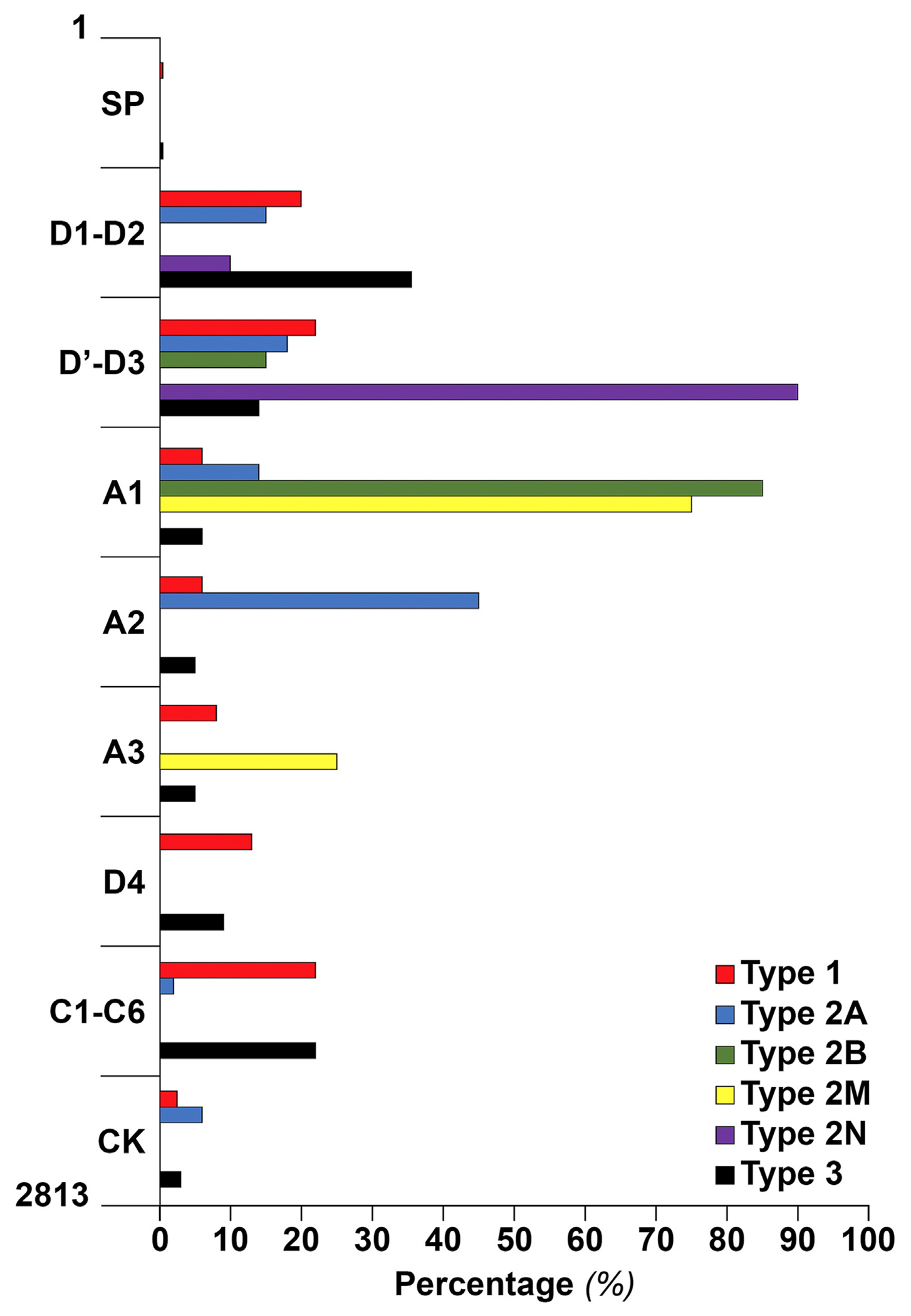

Type 1 variants are scattered throughout all VWF exons, in the VWF promoter, and in the intronic regions near the exons, with no evident hotspot (Figure 3) [33,34]. With strong evidence indicating the contribution of genes other than VWF in the pathogenesis of type 1 VWD and the presence of many benign variants at the VWF locus, the molecular genetic diagnosis of type 1 disease remains challenging despite the wide availability of next-generation sequencing (NGS).

FIGURE 3.

von Willebrand factor (VWF) domain distribution and the type of von Willebrand disease (VWD) for all the reported variants so far. Variants of VWD types 1 and 3 were found all over the VWF domains, mainly propeptide VWF (D1-D2 domain), D′-D3, D4, and C1-C6. In type 2A, 45% of variants were in the A2 domain, and the rest were in the D1-D2 (15%), D′-D3 (20%), A1 (14%), and cystine-knot (CK) domain (6%). All variants of type 2B were in the A1 domain (85%) or D3-A1 junction (15%). Type 2M variants were located mostly in the A1 (75%) but also in the A3 domains (25%). A majority of type 2N variants were in the D′-D3 (89%), and the rest, 11%, were in the D2 domain. SP, signal peptide.

Type 1 VWD is often caused by only 1 affected allele and is inherited in an autosomal-dominant manner. Nevertheless, in approximately 15% of patients, more than 1 pathogenic variant, either in a homozygous or compound heterozygous arrangement, is identified [33,34]. It may be challenging to distinguish between type 3 and type 1 in these situations because the latter condition frequently results in a “severe” type 1 VWD with VWF values that are similar to those of type 3 [35]. Establishing the differential diagnosis may benefit from the examination of the VWFpp level, which is detectable in type 1 patients but not in type 3 patients. This differential diagnosis is clinically important because patients with no VWF but detectable VWFpp have clinical characteristics different from those with the absence of both VWF and VWFpp [35].

The underlying molecular mechanisms causing type 1 VWD can be divided into 3 primary categories: (i) decreased VWF synthesis, (ii) impaired VWF storage and secretion, and (iii) accelerated VWF clearance [5,33]. (i) Decreased VWF synthesis is usually the result of heterozygous nonsense, frameshift (caused by small deletions/insertions), or splice-site (that ultimately creates a null allele) VWF variants [33]. It is expected that the synthesis of protein will be decreased to about 50% of the normal VWF production in the case of heterozygosity for a null allele because VWF protein is only produced from the non-mutated allele. Of note, a heterozygous VWF promoter pathogenic variant removed key transcription binding sites and resulted in a VWF level of 49 IU/dL [36]. Given that the normal range of VWF levels in the general population is about 50 to 150 IU/dL, being heterozygous for a null allele variant, in combination with other VWF level modulators like blood group, may create levels of about 25 to 75 IU/dL. This can result in type 1 VWD in some cases [37] (ie, haploinsufficiency), but in most cases, these VWF levels still fall within the normal range.

(ii) The impaired storage/secretion is caused by VWF variants that create substantial structural changes in VWF, resulting in its retention in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi, proteasome degradation of mutant VWF, and ultimately decreased Weibel–Palade bodies exocytosis [38]. The dominant-negative effect of some heterozygous VWF variants (eg, p.Cys1149Arg and p.Cys1130Phe) plays a significant role in type 1 VWD etiology. In this instance, the mutant subunits endanger the intracellular survival of roughly 50% of the wild-type subunits, which lowers the amount of VWF produced. Several variants, including p.Arg782Gln, p.Cys1130Phe, p.Cys1149Arg, p.Ser1285Pro, p.Val1822Gly, and p.Cys2693Tyr were reported to cause a reduced VWF secretion [33,39]. Other variants, such as p.Cys2190Tyr and p.Ala1716Pro, prevent the tubule formation and storage of VWF, leading to less exocytosis of Weibel–Palade bodies and less VWF released [40]. (iii) Enhanced VWF plasma clearance is reported in 30% to 40% of type 1 VWD cases [28,35,41,42], which led to assigning them to a new official VWD type (type 1C) by the ISTH SSC on VWF [8]. Essentially, missense variants are responsible for this elevated VWF clearance and are often located in the VWF D3 domain (eg, p.Arg1205His/Cys/Ser, p.Cys1130Phe/Gly/Arg, p.Trp1144Gly, and p.Cys1149Arg) [28,43]. Nevertheless, some variants in the A1, A3, and D4 domains have also been associated with increased clearance in VWD [28,43].

4 |. GENETIC CHARACTERIZATION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF LOW VWF (30-50 IU/DL)

The term “low VWF” was formerly used to describe all cases with VWF values of 30 to 50 IU/dL, as it was thought that these levels were only associated with a risk of bleeding [18,44]. However, in accordance with the recent joint guidelines, low VWF cases with significant bleeding are defined as type 1 VWD [8]. Low VWF is the most common form of partial VWF deficiency, and emerging studies showed the presence of VWF disease-causing variants in only 40% to 50% of these cases, with a majority of subjects not possessing VWF pathogenic variants [25,32]. Notwithstanding that abnormal bleeding occurs in a significant proportion of cases [32,45], it seems increasingly plausible that the low VWF in most of these individuals is the result of contributions from several (?many) genes and coincident environmental factors. In addition, the bleeding observed in most of these cases appears not to be associated with low VWF levels [25,32,45]. A number of genes outside the VWF locus have been implicated in altering VWF levels, with the ABO blood group being the most prominent example [46,47]. Besides the ABO blood group, 17 other genes have been identified to influence VWF levels by genome-wide association studies [47,48]. These genes, involved in different stages of the VWF life cycle such as secretion (eg, STXBP5 and STX2) and clearance (eg, CLEC4M and STAB2), are likely contributing to low VWF and possibly also to type 1 VWD phenotypes [46]. Furthermore, the role of several other loci (eg, SCARA5, LRP1, UFM, GPCR, AVPR2, and Siglec-5) needs to be determined in patients with mildly reduced VWF levels [46]. As one prominent example, the variant p.Tyr1584Cys is frequently documented in patients with low VWF/type 1 VWD and is associated with low VWF levels (~30-40 IU/dL), often coincident with blood group O and incomplete penetrance, with variable bleeding severity [21,28,49,50].

5 |. GENETIC CHARACTERIZATION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF TYPE 2 VWD

Type 2 VWD results from various qualitative defects of VWF and accounts for approximately 25% to 30% of all VWD cases. The distinct etiology of each type 2 VWD requires a battery of phenotypic laboratory tests or genetic analysis to establish the correct diagnosis. In contrast to types 1 and 3, VWF pathogenic variants are usually located in specific functional domains and similar to those of type 3, but in contrast to type 1/low VWF, pathogenic variants are identified in almost all patients [51].

5.1 |. Type 2A

Type 2A VWD is characterized by reduced VWF-dependent platelet adhesion as a result of reduced or absence of the high- and intermediate-molecular-weight multimers, the most biologically active forms of VWF [5]. Over 180 type 2A variants have been described so far in the literature, and the majority of them are missense with few exceptions of small in-frame deletions or splice variants (Figure 2) [4,33]. Current classifications of VWD categorize several different phenotypes as type 2A [5], which share a similar defect in the VWF multimeric pattern. Notwithstanding, these distinct phenotypes, described in the previous VWD classification as IIA, IIC, IID, and IIE [52], stem from different molecular etiologies.

The most common form of the type 2A phenotype is 2A(IIA), caused by VWF variants in the major binding site of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 13 (ADAMTS-13) on VWF (A2 domain, exon 28) and is dominantly inherited (Figure 3). Patients show a lack of high- and intermediate-molecular-weight VWF multimers and markedly pronounced multimeric satellite bands [53]. The ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination (RIPA) assay or molecular testing of VWF gene is fundamental to discriminate between type 2B patients who show a similar pattern of multimer loss and type 2A. Platelet-rich plasma of type 2B patients agglutinates at lower concentrations of ristocetin (<0.8 mg/mL; normal range, 0.8-1.2 mg/mL), whereas platelet-rich plasma of type 2A patients requires a higher concentration of ristocetin to agglutinate (>1.2 mg/mL) [54]. Two mechanisms have been reported to explain the 2A(IIA) phenotype, subclassified as group 1 and group 2 [5]. VWF subunits with group 1 variants (eg, p.Gly1505Arg, p.Leu1540Pro, and p.Ser1506Leu) show an impaired multimer assembly and enhanced proteolysis. Group 2 variants (eg, p.Arg1597Trp, p.Glu1638Lys, and p.Gly1505Glu) do not interfere with normal VWF secretion but instead render the mutant A2 domain subunit more susceptible to being proteolytically cleaved by ADAMTS-13 at the peptide bond between Tyr1605-Met1606 [5]. This enhanced plasma proteolysis results in the selective loss of the largest form of VWF multimers and thus accelerated loss of VWF activity.

The second most frequent type 2A phenotype is 2A(IIE), caused by VWF variants located in the multimerization sequences of VWF (D3 domain) and is dominantly inherited. Most of the type 2A(IIE) variants involve a cysteine residue (eg, p.Cys1130Arg, p.Cys1130Trp, p.Tyr1146Cys, p.Cys1153Tyr, and p.Cys1173Phe) [55]. These variants are often correlated with a moderate-to-severe defect in VWF secretion and compromise the multimerization process, leading to lack/decreased levels of HMWM [55]. The significant proportion of type 2A(IIE) variants among type 2A patients has also been demonstrated by the French VWD cohort (42 cases of 122 type 2A patients) [30] and recent Italian findings (32 of 98 type 2A patients) [53]. It is noteworthy that the type 2A(IIE) mutational spectrum is partly overlapping with that of type 1 VWD, indicating problems resulting from nonstandardized multimer analysis or interindividual phenotypic differences despite having the same VWF genotype. Several variants with a significantly enhanced VWF clearance are reported in type 2A(IIE) [28]. Genetic testing could be focused on VWF exons 22 and 25 to 27 and 5′ portion of exon 28.

A rarer type 2A phenotype, 2A(IIC), arises from VWF variants in the D1-D2 domains (exons 2-17), being characterized by lack of HMWM, absence of the triplet structure with only the main band present, and recessive inheritance [5]. Given the central role of the propeptide for the proper formation of VWF multimers and VWF sorting to storage granules, type 2A(IIC) variants compromise the multimerization process and hence cause the lack of HMWM [5]. Only a few variants have been identified associated with type 2A(IIC), mainly in the D2 domain (eg, p.Gly550Arg, p.Asn528Ser, and p.Cys623Trp) [33].

Type 2A(IID) is the least common phenotype of type 2A caused by variants located in the dimerization sequences of VWF, ie, the cystine knot, VWF exons 51 to 52 [5]. The intermolecular disulfide bonds of Cys2771–2773′, Cys2771′–2773, and Cys2811–2811′ are critical for VWF dimerization. Nucleotide changes at codon 2771 or 2773 that result in variants such as p.Cys2771Tyr, p.Cys2771Ser, and p.Cys2773Arg, impair the pro-VWF dimerization and, therefore, the multimerization process, leading to type 2A(IID) VWD [33]. This type 2A is defined by a decreased proportion of HMWM, the presence of uneven bands in the multimeric pattern, and dominant inheritance [56].

5.2 |. Type 2B

Type 2B VWD is the result of gain-of-function VWF variants leading to an enhanced affinity of the VWF A1 domain for binding to the platelet GPIbα receptor [5]. Type 2B is often associated with the loss of the HMWM in plasma but not in platelets. Thereby, variants of type 2B do not impair VWF production nor the assembly of large VWF multimers, but the spontaneous binding of plasma VWF to platelets results in low VWF plasma levels [5]. In addition, this enhanced interaction of type 2B VWF and GPIbα accelerates the cleavage of VWF by ADAMTS-13, further depleting the HMWM and enriching VWF multimeric satellite bands in the so-called triplet structure. The mild-moderate thrombocytopenia in these patients, which worsens with stress, is associated with severe type 2B variants, for example, p.Val1316Met and p.Arg1306Trp [57]. Type 2B is inherited as a fully penetrant dominant trait, and all variants responsible for this type are located in the A1 domain (85%) or in the D3-A1 junction (15%; Figure 3) [4]. The only exception so far reported of type 2B phenotype with no variant in the A1 domain is p.Arg924Gln/p.Ala2178Ser located in D’D3 and D4 domains, respectively [58]. More than 45 different VWF variants have been reported to cause type 2B [4]. Several studies have shown that p.Val1316Met variant might affect megakaryopoiesis and platelet function [59–62]. Despite some heterogeneity, type 2B variants were shown to frequently affect regions of A1 domain with enhanced dynamics and reduced mechanical stability [63]. The loss of large VWF multimers and thrombocytopenia is not constantly seen in all type 2B patients. For instance, variants p.Pro1266Leu and p.Pro1266Gln show an enhanced GPIbα binding but with no loss of HMWM or thrombocytopenia before and after desmopressin [57]. Patients carrying such variants usually have mild bleeding symptoms and, in some cases, may have none, highlighting the role of genetic testing. Platelet-type VWD is a rare, dominantly inherited platelet disorder due to gain-of-function variants in the GP1BA gene (eg, p.Gly233Val and p.Met239Val) [64]. These variants cause spontaneous platelet GPIbα-VWF A1 domain binding and result in enhanced RIPA similar to type 2B [64]. Therefore, establishing a differential diagnosis between type 2B and platelet-type VWD is crucial for selection of appropriate transfusion therapy (VWF concentrate vs platelets, respectively). The accurate diagnosis can be achieved by performing platelet/plasma mixing studies, but in 2024, analysis of the VWF (exon 28) and GP1BA genes is the most efficient and definitive testing strategy [8].

5.3 |. Type 2M

Type 2M VWD refers to all qualitative VWF variants that result in decreased VWF-GPIbα or VWF:CB (types I, III, IV, and VI) activities without a selective deficiency of HMWM [5]. More than 80 VWF variants have been identified to cause type 2M, most of them being missense with a few exceptions of in-frame deletions or gene conversions (Figure 2) [4,39].

In the first group, type 2M patients present a reduced VWF-GPIbα binding activity/VWF:Ag ratio, notwithstanding a normal multimer distribution [5]. Some type 2M patients may also show evidence of ultralarge-VWF [5]. These type 2M cases are inherited dominantly, and the heterozygous variants are located in the VWF A1 domain (exon 28, Figure 3), such as p.Ser1285Phe, p.Phe1293Leu, p.Arg1315Cys, p.Val1360Ala, p.Arg1399Cys, and p.Lys1408Leu. The variants affect either the direct binding of VWF to GPIbα (eg, p.Ser1285Phe) or, by enhancing the stability of the A1 domain, reduce the A1 unfolding under the shear conditions required to mediate binding to GPIbα (eg, p.Gly1324Ala and p.Gly1324Ser) [33]. As with type 2A patients, platelet-rich plasma from these patients agglutinates at a concentration of ristocetin >1.2 mg/mL (normal range, 0.8-1.2 mg/mL). Three frequent type 2 VWD variants (p.Arg1374Cys, p.Arg1374His, and p.Arg1315Leu) have often been reported as type 2M variants [53]. However, their classification as type 2M has been controversial [53]. Seidizadeh et al. [65] recently proposed a new classification of VWD type 2M/2A for these variants because these 3 variants clearly shared a common phenotype with 2M and 2A.

The second group of type 2M patients presents a decreased VWF:CB/VWF:Ag ratio with a normal multimer distribution [5]. As VWF physiologically binds collagen types I and III through the A3 domain and collagen types IV and VI through the A1 domain, a defective A1 or A3 collagen binding can result in type 2M VWD. Being inherited dominantly, VWF variants causing a collagen binding defect have been identified primarily in the A3 domain (exons 29-32) such as p.Ser1731Thr, p.Ser1738Ala, p.Trp1745Cys, p.Met1761Lys, p.His1786Asp, and p.Ser1783Ala (Figure 3) [53]. Although few variants were found in the A1 domain (exon 28), such as p.Arg1399His, p.Gln1402Pro, and p.Arg1392_Gln1402del [66,67]. Type 2M VWD with defective collagen binding is less frequent than type 2M with defective GPIbα binding, and patients also seem to have milder bleeding symptoms. Two independent studies on large cohorts of VWD patients from France [30] and Italy [53] found that about 22% and 26% of patients with type 2M have VWF:CB defects, respectively.

5.4 |. Type 2N

Type 2N VWD refers to qualitative VWF variants that lead to a decreased affinity of this moiety for FVIII [68]. This less frequent VWD subtype is characterized by low plasma levels of FVIII, similar to mild or moderate hemophilia A. However, VWF levels are often normal and affected patients usually have an intact VWF multimeric profile [68]. Therefore, type 2N may easily be misdiagnosed as hemophilia A or its carrier state, making the differential diagnosis essential in order to reduce incorrect diagnosis and inappropriate treatment [69,70]. While hemophilia is an X-linked disease, type 2N is inherited as an autosomal recessive disease. The differential and definite diagnosis of type 2N is straightforward by measuring the capacity of VWF to bind FVIII (VWF:FVIIIB) [68], although this test is not available in many laboratories. Nevertheless, because almost all type 2N variants are located in the D’-D3 domains of VWF, diagnosis can be established or confirmed by targeted genetic testing of VWF exons 17 to 26 (Figure 3) [68,71], as suggested by the recent joint guidelines on VWD [8]. Three variants (p.Thr791Met, p.Arg816Trp, and p.Arg854Gln) account for the majority of the identified variants in patients with type 2N [68].

More than 50 VWF variants have been reported to cause type 2N, mainly missense (Figure 2) [33]. Type 2N patients may be homozygotes for a single type 2N variant, compound heterozygotes for 2 distinct 2N missense variants (this rarely occurs), or compound heterozygotes for a type 2N variant and a quantitative VWF variant. Type 2N VWD owing to a type 2N variant and a quantitative VWF variant exhibits diminished levels of VWF in addition to FVIII. Thus, a normal FVIII/VWF:Ag ratio is expected and makes a VWF:FVIIIB assay or molecular testing crucial for diagnosis [72]. Two interesting type 2N variants were identified to disrupt the furin cleavage site at the carboxyl terminus of the VWFpp (p.Arg760Cys and p.Arg763Gly), hence leading to the persistence of the propeptide that sterically inhibits binding of FVIII to the mature VWF subunit [73,74].

6 |. GENETIC CHARACTERIZATION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF TYPE 3 VWD

Type 3, being the most rare and severe form of VWD, only accounts for about 5% of all VWD cases and is characterized by virtually complete VWF deficiency (<5 IU/dL) in both plasma and platelets [5]. These patients have a defect in both primary hemostasis and intrinsic coagulation due to the deficiency of VWF and markedly reduced FVIII plasma levels [5]. Type 3 VWD is inherited as a recessive or semidominant trait, and variants are located in all exons of VWF, similar to the pattern of variants in type 1 VWD (Figure 3) [37,75,76]. As a result of the introduction of NGS technology, more than 400 different genetic variants have been identified among patients with type 3 despite its low prevalence [4,29,30,37,75]. Most of these genetic defects result in null alleles, particularly nonsense variants, followed by small deletions, splice-site variations, duplications, large deletions, gene conversions, and small insertions (Figure 2). In spite of this, approximately 25% of the variants identified in these patients were missense [37]. A few hotspot nonsense variants at the arginine codons such as p.Arg365*, p.Arg1659*, p.Arg1853*, and p.Arg2535* have been repeatedly found in various populations [33]. Although type 3 inheritance has usually been considered recessive, some studies reported evidence for semidominant inheritance, with almost 50% of the obligate carriers (parents and offspring) having reduced VWF levels and bleeding symptoms [37,76]. Interestingly, null variants were common among these type 1 VWD patients or low VWF subjects (ie, haploinsufficiency) [37], suggesting the role of other modifying genes affecting VWF levels. Despite the significant improvement of the techniques to detect genetic variants, in most type 3 studies, disease-causing variants are identified only in 80% to 95% of cases. The unidentified variants in these patients are expected to be in the VWF gene promoter, distant regulatory sequences, deep intronic sequences, or other modifying genes.

Patients with type 3 VWD may develop neutralizing alloantibodies to VWF, which will render replacement therapy ineffective and may result in anaphylactic reactions [77]. This severe complication is often associated with homozygous large gene deletions, making genetic testing a useful tool to predict this event. The largest type 3 VWD investigation on patients from Europe and Iran reported a prevalence of 8.4% for anti-VWF antibodies and 6% for neutralizing VWF inhibitors [78].

7 |. ASSESSMENT OF VARIANT PATHOGENICITY

For VWF variants that have been previously reported in patients with VWD, reviewing the scientific literature and available mutation databases could be beneficial to determine the genotype-phenotype association of these variants by using the experience of other international centers. The European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders (EAHAD) Coagulation Factor Variant Databases (https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/VWF) and the Human Gene Mutation Database (https://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php) are the 2 main databases containing VWF variants. ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) is another useful and freely accessible database that archives reports of the relationships among human genetic variations and phenotypes.

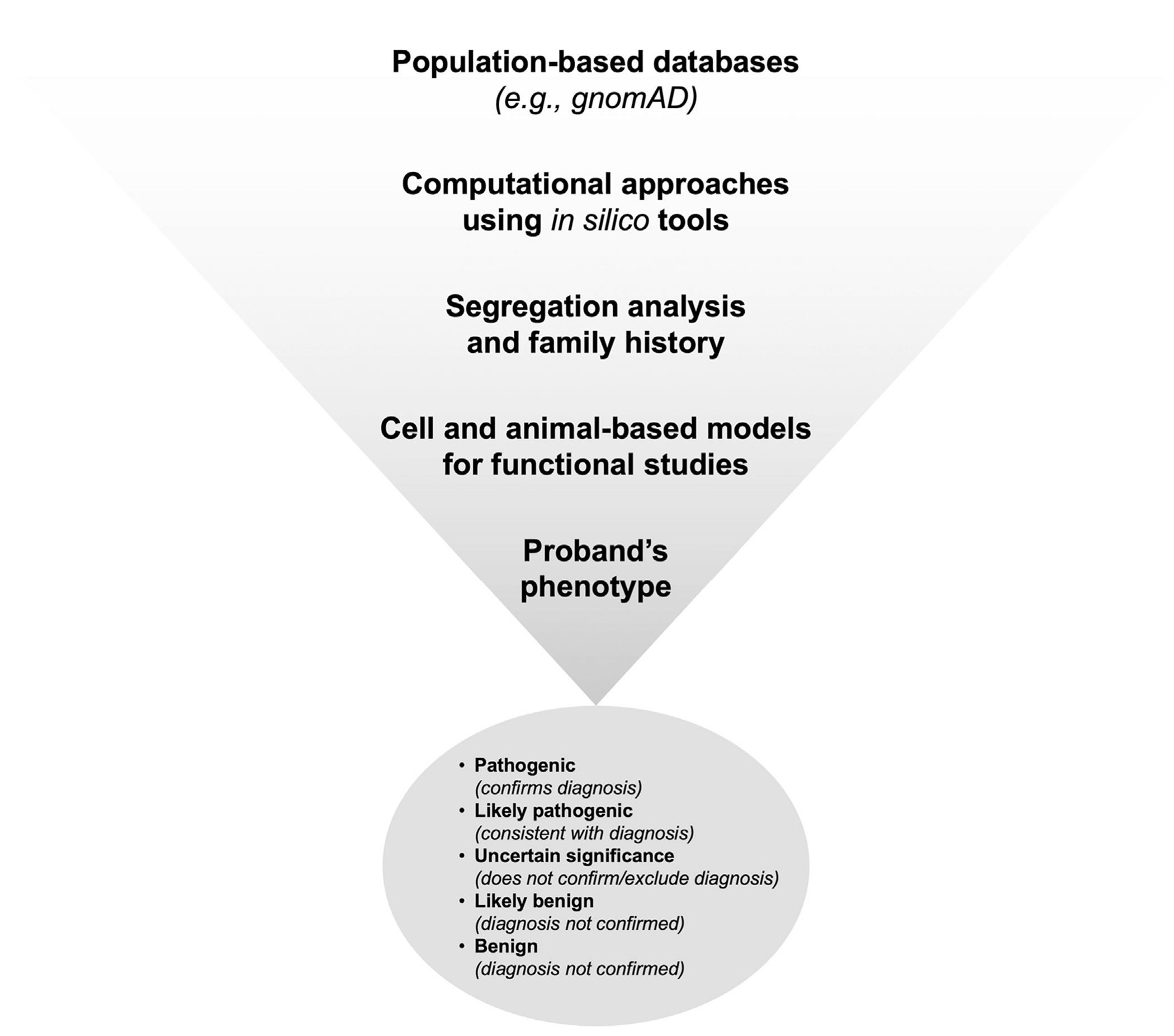

In the case of a novel variant, there are several approaches to determine its potential pathogenicity (Figure 4). In general, large rearrangements, copy number variants, and premature termination codons are clearly pathogenic and do not require extensive analysis. An essential first step is to filter the data to differentiate a benign variant from a potential candidate pathogenic variant. Large population-based databases (eg, https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) can be useful for obtaining the frequencies of variants in large populations, with a frequency cutoff of <1% being used to discriminate a disease-causing variant from a neutral variant. Notwithstanding, some pathogenic VWF variants (eg, p.Arg854Gln, p.Ser1731Thr, and p.Thr1034del) can have frequencies close to 1% in certain populations [4]. Next, interpretation of the effect of variants at the protein level can be assisted by computational approaches using in silico tools. These algorithms are categorized into 2 main groups: predicting missense variants and splicing variants. For missense variants, these tools predict the known pathogenic variants with a range of 65% to 80% accuracy [79] but with a lower specificity. A list of these in silico tools is reported in Table 2, including PolyPhen2, SIFT, REVEL, and CADD. The second group of algorithms was developed to predict splicing such as SpliceAI, GeneSplicer, and Human Splicing Finder (Table 2). Of note, variants that alter the consensus dinucleotide–splice site (first or last 2 intronic nucleotides or ±1, ±2) are generally considered pathogenic with no further need for investigation. It is recommended to use multiple software programs for sequence variant interpretation, but these predictions should not be used as the sole source of evidence in clinical decisions [79]. In addition, segregation within family members is very useful to better understand the pathogenicity of genetic variants and the inheritance pattern within a family [80]. Functional studies can also be approached from the messenger RNA level by analyzing the effect of variants on splicing. Even though nucleotide substitutions at the exon/intron boundary (splice sites) are more commonly associated with an abnormal splicing pattern, other variants such as deep intronic, nonsense, missense, and synonymous variants might also impair the normal splicing process through disruption of splice enhancer and silencer sequences. Cell and animal-based models can be applied to assess the influence of identified variants on protein production and function [81,82]. The characterization of VWF variants and the interpretation of genotype-phenotype associations have also been made possible by the use of patient-derived endothelial colony-forming cells [83,84].

FIGURE 4.

Assessment of pathogenicity and interpretation of novel variants. In the case of a novel variant, large population-based databases such as gnomAD can be used to filter out common variants. Next, the effect of variants at the protein level can be assisted using in silico tools. The study of family members is useful in understanding the pathogenicity of genetic variants and their inheritance patterns. The true effect of variants on protein production and function can be determined by cell and animal-based models. The final step is to confirm the variant influence in the studied proband using phenotypic assays to classify variant.

TABLE 2.

In silico predictive algorithms that are used for missense and splice variants.

| Category | Name | Website | Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missense | ConSurf | http://consurftest.tau.ac.il | Evolutionary conservation |

| FATHMM | http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk | Evolutionary conservation | |

| MutationAssessor | http://mutationassessor.org | Evolutionary conservation | |

| SIFT | http://sift.jcvi.org | Evolutionary conservation | |

| MutationTaster | http://www.mutationtaster.org | Protein structure/function and evolutionary conservation | |

| MutPred | http://mutpred.mutdb.org | Protein structure/function and evolutionary conservation | |

| PolyPhen-2 | http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2 | Protein structure/function and evolutionary conservation | |

| PROVEAN | http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php | Alignment and measurement of similarity between variant sequence and protein sequence homolog | |

| Condel | Condel http://bg.upf.edu/fannsdb/ | Combines SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and MutationAssessor | |

| CADD | http://cadd.gs.washington.edu | Contrasts annotations of fixed/nearly fixed derived alleles in humans with simulated variants | |

| REVEL | https://sites.google.com/site/revelgenomics/downloads | Combines 13 individuals for in silico algorithms | |

| Splice-site prediction | GeneSplicer | http://www.cbcb.umd.edu/software/GeneSplicer/gene_spl.shtml | Markov models |

| SpliceAI | https://spliceailookup.broadinstitute.org/ | Neural networks | |

| Human Splicing Finder | http://www.umd.be/HSF/ | Position-dependent logic | |

| MaxEntScan | http://genes.mit.edu/burgelab/maxent/Xmaxentscan_scoreseq.html | Maximum entropy principle | |

| NetGene2 | http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetGene2 | Neural networks | |

| NNSplice | http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html | Neural networks | |

| FSPLICE | http://www.softberry.com/berry.phtml?topic=fsplice&group=programs&subgroup=gfind | Species-specific predictor for splice sites based on weight matrices model | |

| varSEAK | https://varseak.bio/ | - |

8 |. REPORTING

Based on the strength of the evidence, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology recommend [79] systematic characterization of variants associated with Mendelian disorders as pathogenic (confirms diagnosis), likely pathogenic (consistent with diagnosis), uncertain significance (does not confirm/exclude diagnosis), likely benign (diagnosis not confirmed), and benign (diagnosis not confirmed). Based on the number of independent observations that associate a variant with a disease phenotype, as well as functional characterizations of variant pathogenicity, class 5 and class 4 pathogenicity are demonstrated. It is recommended that only class 4 and 5 variants be reported or class 3 variants if no other pathogenic candidates are identified [85]. Of note, it is essential that clinical genetic testing results are presented in a clear and concise way to ensure that they are readable and understandable.

9 |. GENETIC COUNSELING

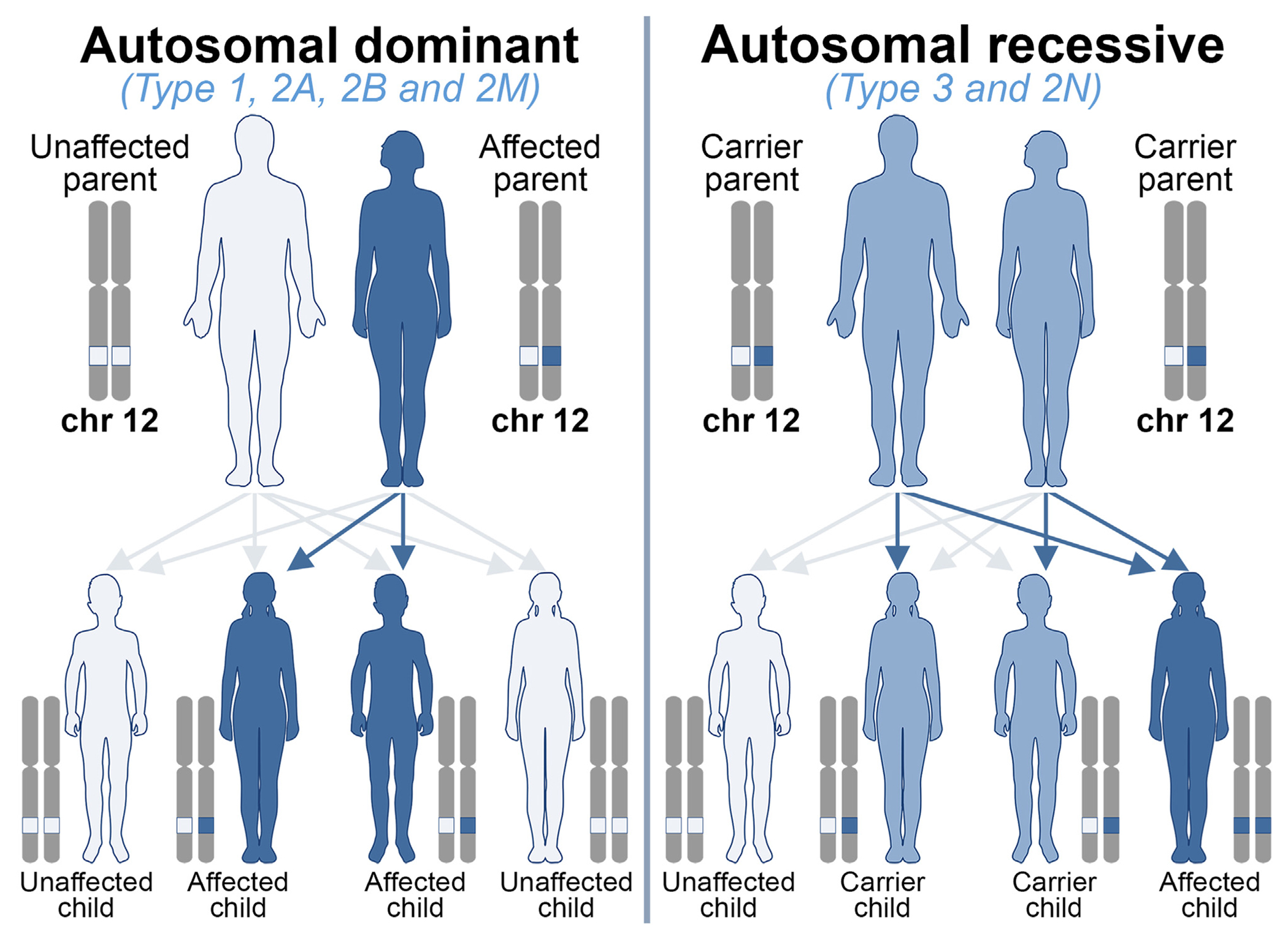

VWD occurs among men and women equally, and autosomal–dominant VWD types include type 1, 2A, 2B, and 2M, whereas recessive types include type 2N, type 2A(IIC), and type 3 (Figure 5). In general, VWD patients with an autosomal-dominant form have an affected parent, but it can also arise from a new VWF variant (ie, de novo). The latter scenario was reported in about 5% of probands, with no identified variants in parents [21,86]. In autosomal recessive forms, both parents are carriers of the genetic defect(s). The chance of a child inheriting VWD from an affected parent is 1 in 2 (50%) for dominant forms. The chance of a child inheriting 2 copies of the altered gene and developing VWD recessive types when both parents are carriers is 1 in 4 (25%; Figure 5). In cases of pregnancies at high risk, typically type 3 VWD, prenatal diagnosis is possible. The causative genetic alleles in the parents must be identified before performing prenatal diagnosis [87].

FIGURE 5.

Genetic counseling for von Willebrand disease (VWD). VWD occurs among men and women equally. Autosomal–dominant VWD types: type 1, 2A, 2B, and 2M; autosomal recessive VWD types: type 2N and type 3. Of note, a rare type 2A phenotype, 2A(IIC), is also inherited as autosomal recessive. An autosomal-dominant VWD only requires one copy of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) gene to be altered for the condition to present. The chance of a child inheriting the variant and developing the VWD from an affected parent is 1 in 2 (50%). In autosomal recessive conditions, both copies of the VWF gene are required to be altered for the condition to be present. The chance of a child inheriting 2 copies of the altered gene and developing VWD when both parents are carriers is 1 in 4 (25%). Chr, chromosome.

10 |. NGS

The utility of NGS approaches for diagnosis of many rare disorders has been documented [88]. The potential of NGS for VWD diagnosis was revealed in a preliminary study based on the amplification of all exons, intron–exon boundaries, and promoter regions using microfluidics technology [89] and later on by many others [31,75,90]. Considering the cost benefit of NGS and its ability to investigate many samples at the same time, the molecular testing of VWD can be very beneficial.

This may also facilitate personalized and effective care for VWD patients. Another advantage of NGS over (target) Sanger sequencing is that patients may have more than 1 variant, which can change the VWD phenotype. Currently, NGS can be used for differential diagnosis when RIPA (type 2A from 2B and type 2B from Platelet-type VWD), VWF:FVIIIB (type 2N from hemophilia A), or multimer assays (type 2M from 2A and 2B) produce equivocal results or are not available. Furthermore, it can be used for confirming diagnosis (type 1 with VWF levels <30 IU/dL, all type 2 and type 3) and genetic counseling (types 3 and 2N).

11 |. CONCLUSION

Genetic testing is increasingly integrated into the diagnostic assessment for VWD. The advent of NGS has greatly facilitated the incorporation of genetic diagnosis, which can now be performed in a timely and efficient manner. Genetic diagnosis for all type 2 VWD subtypes and for type 3 VWD will continue to play an important role in patient management, and with increasing knowledge of the genetic modifiers of low VWF levels, genetic testing for type 1 VWD may become more practical.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Bando Ricerca Corrente). We acknowledge P.M. Mannucci for critical advice and L.F. Ghilardini for the illustration work. The Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico is a member of the European Reference Network EuroBloodNet.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF COMPETING INTERESTS

F.P. serves on the advisory committee of CSL-Behring, BioMarin, Roche, Sanofi, and Sobi and participated in educational meetings/symposia of Takeda/Spark. D.L. reports research support from BioMarin, CSL-Behring, and Sanofi and participates in an advisory role for BioMarin, CSL-Behring, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. The other authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Dini E. Epidemiological investigation of the prevalence of von Willebrand’s disease. Blood. 1987;69:454–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Werner EJ, Broxson EH, Tucker EL, Giroux DS, Shults J, Abshire TC. Prevalence of von Willebrand disease in children: a multiethnic study. J Pediatr. 1993;123:893–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bowman M, Hopman W, Rapson D, Lillicrap D, James P. The prevalence of symptomatic von Willebrand disease in primary care practice. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seidizadeh O, Cairo A, Baronciani L, Valenti L, Peyvandi F. Population-based prevalence and mutational landscape of von Willebrand disease using large-scale genetic databases. NPJ Genom Med. 2023;8:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sadler JE, Budde U, Eikenboom JC, Favaloro EJ, Hill FG, Holmberg L, Ingerslev J, Lee CA, Lillicrap D, Mannucci PM, Mazurier C, Meyer D, Nichols WL, Nishino M, Peake IR, Rodeghiero F, Schneppenheim R, Ruggeri ZM, Srivastava A, Montgomery RR, et al. Update on the pathophysiology and classification of von Willebrand disease: a report of the Subcommittee on von Willebrand Factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leebeek FW, Eikenboom JC. Von Willebrand’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2067–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Federici A. Clinical diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2004;10:169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].James PD, Connell NT, Ameer B, Di Paola J, Eikenboom J, Giraud N, Haberichter S, Jacobs-Pratt V, Konkle B, McLintock C, McRae S, R Montgomery R, O’Donnell JS, Scappe N, Sidonio R, Flood VH, Husainat N, Kalot MA, Mustafa RA. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. 2021;5:280–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Connell NT, Flood VH, Brignardello-Petersen R, Abdul-Kadir R, Arapshian A, Couper S, Grow JM, Kouides P, Laffan M, Lavin M, Leebeek FWG, O’Brien SH, Ozelo MC, Tosetto A, Weyand AC, James PD, Kalot MA, Husainat N, Mustafa RA. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the management of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. 2021;5:301–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mancuso DJ, Tuley EA, Westfield LA, Worrall NK, Shelton-Inloes BB, Sorace JM, Alevy YG, Sadler JE. Structure of the gene for human von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:19514–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mancuso DJ, Tuley EA, Westfield LA, Lester-Mancuso TL, Le Beau MM, Sorace JM, Sadler JE. Human von Willebrand factor gene and pseudogene: structural analysis and differentiation by polymerase chain reaction. Biochemistry. 1991;30:253–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lenting PJ, Christophe OD, Denis CV. von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: connecting the far ends. Blood. 2015;125:2019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Springer TA. von Willebrand factor, Jedi knight of the bloodstream. Blood. 2014;124:1412–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lenting P, Casari C, Christophe O, Denis C. von Willebrand factor: the old, the new and the unknown. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:2428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yee A, Kretz CA. Von Willebrand factor: form for function. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seidizadeh O, Baronciani L. The molecular basis of von Willebrand disease. In: Provan D, Lazarus HM, eds. Molecular hematology. John Wiley & Sons; 2024:231–49. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Budde U, Schneppenheim R, Eikenboom J, Goodeve A, Will K, Drewke E, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Federici AB, Batlle J, Pérez A, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Ingerslev J, Habart D, Vorlova Z, Holmberg L, Lethagen S, Pasi J, Hill F, Peake I. Detailed von Willebrand factor multimer analysis in patients with von Willebrand disease in the European study, molecular and clinical markers for the diagnosis and management of type 1 von Willebrand disease (MCMDM-1VWD). J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:762–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sadler JE. von Willebrand disease type 1: a diagnosis in search of a disease. Blood. 2003;101:2089–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bowman M, James P. Controversies in the diagnosis of type 1 von Willebrand disease. Int J Lab Hematol. 2017;39:61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cumming A, Grundy P, Keeney S, Lester W, Enayat S, Guilliatt A, Bowen D, Pasi J, Keeling D, Hill F, Bolton-Maggs PH, Hay C, Collins P, UK Haemophilia Centre Doctors’ Organisation. An investigation of the von Willebrand factor genotype in UK patients diagnosed to have type 1 von Willebrand disease. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:630–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].James PD, Notley C, Hegadorn C, Leggo J, Tuttle A, Tinlin S, Brown C, Andrews C, Labelle A, Chirinian Y, O’Brien L, Othman M, Rivard G, Rapson D, Hough C, Lillicrap D. The mutational spectrum of type 1 von Willebrand disease: results from a Canadian cohort study. Blood. 2007;109:145–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Goodeve A, Eikenboom J, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Federici AB, Batlle J, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Schneppenheim R, Budde U, Ingerslev J, Habart D, Vorlova Z, Holmberg L, Lethagen S, Pasi J, Hill F, Hashemi Soteh M, Baronciani L, et al. Phenotype and genotype of a cohort of families historically diagnosed with type 1 von Willebrand disease in the European study, Molecular and Clinical Markers for the Diagnosis and Management of Type 1 von Willebrand Disease (MCMDM-1VWD). Blood. 2007;109:112–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lanke E, Johansson A, Halldén C, Lethagen S. Genetic analysis of 31 Swedish type 1 von Willebrand disease families reveals incomplete linkage to the von Willebrand factor gene and a high frequency of a certain disease haplotype. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2656–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Johansson AM, Halldén C, Säll T, Lethagen S. Variation in the VWF gene in Swedish patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:447–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Flood VH, Christopherson PA, Gill JC, Friedman KD, Haberichter SL, Bellissimo DB, Udani RA, Dasgupta M, Hoffmann RG, Ragni MV, Shapiro AD, Lusher JM, Lentz SR, Abshire TC, Leissinger C, Hoots WK, Manco-Johnson MJ, Gruppo RA, Boggio LN, Montgomery KT, et al. Clinical and laboratory variability in a cohort of patients diagnosed with type 1 VWD in the United States. Blood. 2016;127:2481–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Atiq F, Boender J, van Heerde WL, Tellez Garcia JM, Schoormans SC, Krouwel S, Cnossen MH, Laros-van Gorkom BAP, de Meris J, Fijnvandraat K, van der Bom JG, Meijer K, van Galen KPM, Eikenboom J, Leebeek FWG. Importance of genotyping in von Willebrand disease to elucidate pathogenic mechanisms and variability in phenotype. HemaSphere. 2022;6:e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yadegari H, Driesen J, Pavlova A, Biswas A, Hertfelder HJ, Oldenburg J. Mutation distribution in the von Willebrand factor gene related to the different von Willebrand disease (VWD) types in a cohort of VWD patients. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:662–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Seidizadeh O, Baronciani L, Pagliari MT, Cozzi G, Colpani P, Cairo A, Siboni SM, Biguzzi E, Peyvandi F. Genetic determinants of enhanced von Willebrand factor clearance from plasma. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21:1112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Borràs N, Batlle J, Pérez-Rodríguez A, López-Fernández MF, Rodríguez-Trillo Á, Lourés E, Cid AR, Bonanad S, Cabrera N, Moret A, Parra R, Mingot-Castellano ME, Balda I, Altisent C, Pérez-Montes R, Fisac RM, Iruín G, Herrero S, Soto I, de Rueda B, et al. Molecular and clinical profile of von Willebrand disease in Spain (PCM-EVW-ES): comprehensive genetic analysis by next-generation sequencing of 480 patients. Haematologica. 2017;102:2005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Veyradier A, Boisseau P, Fressinaud E, Caron C, Ternisien C, Giraud M, Zawadzki C, Trossaert M, Itzhar-Baïkian N, Dreyfus M, d’Oiron R, Borel-Derlon A, Susen S, Bezieau S, Denis CV, Goudemand J. French Reference Center for von Willebrand disease. A laboratory phenotype/genotype correlation of 1167 French patients from 670 families with von Willebrand disease: a new epidemiologic picture. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fidalgo T, Salvado R, Corrales I, Pinto SC, Borràs N, Oliveira A, Martinho P, Ferreira G, Almeida H, Oliveira C, Marques D, Gonçalves E, Diniz M, Antunes M, Tavares A, Caetano G, Kjöllerström P, Maia R, Sevivas TS, Vidal F, et al. Genotype–phenotype correlation in a cohort of Portuguese patients comprising the entire spectrum of VWD types: impact of NGS. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116:17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lavin M, Aguila S, Schneppenheim S, Dalton N, Jones KL, O’Sullivan JM, O’Connell NM, Ryan K, White B, Byrne M, Rafferty M, Doyle MM, Nolan M, Preston RJS, Budde U, James P, Di Paola J, O’Donnell JS. Novel insights into the clinical phenotype and pathophysiology underlying low VWF levels. Blood. 2017;130:2344–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].de Jong A, Eikenboom J. Von Willebrand disease mutation spectrum and associated mutation mechanisms. Thromb Res. 2017;159:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Batlle J, Pérez-Rodríguez A, Corrales I, Borràs N, Costa Pinto J, López-Fernández MF, Vidal F, PCM-EVW-ES Investigators Team. Update on molecular testing in von Willebrand disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2019;45:708–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sanders YV, Groeneveld D, Meijer K, Fijnvandraat K, Cnossen MH, van der Bom JG, Coppens M, de Meris J, Laros-van Gorkom BA, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Leebeek FW, Eikenboom J, WiN study group. von Willebrand factor propeptide and the phenotypic classification of von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2015;125:3006–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Othman M, Chirinian Y, Brown C, Notley C, Hickson N, Hampshire D, Buckley S, Waddington S, Parker AL, Baker A, James P, Lillicrap D. Functional characterization of a 13-bp deletion (c.-1522_-1510del13) in the promoter of the von Willebrand factor gene in type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2010;116:3645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Christopherson PA, Haberichter SL, Flood VH, Perry CL, Sadler BE, Bellissimo DB, Di Paola J, Montgomery RR, Zimmerman Program Investigators. Molecular pathogenesis and heterogeneity in type 3 VWD families in US Zimmerman program. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20:1576–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang JW, Bouwens EA, Pintao MC, Voorberg J, Safdar H, Valentijn KM, de Boer HC, Mertens K, Reitsma PH, Eikenboom J. Analysis of the storage and secretion of von Willebrand factor in blood outgrowth endothelial cells derived from patients with von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2013;121:2762–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zolkova J, Sokol J, Simurda T, Vadelova L, Snahnicanova Z, Loderer D, Dobrotova M, Ivankova J, Skornova I, Lasabova Z, Kubisz P, Stasko J. Genetic background of von Willebrand disease: history, current state, and future perspectives. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46:484–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Castaman G, Giacomelli SH, Jacobi PM, Obser T, Budde U, Rodeghiero F, Schneppenheim R, Haberichter SL. Reduced von Willebrand factor secretion is associated with loss of Weibel–Palade body formation. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:951–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Haberichter SL, Balistreri M, Christopherson P, Morateck P, Gavazova S, Bellissimo DB, Manco-Johnson MJ, Gill JC, Montgomery RR. Assay of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) propeptide to identify patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease with decreased VWF survival. Blood. 2006;108:3344–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Eikenboom J, Federici AB, Dirven RJ, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Budde U, Schneppenheim R, Batlle J, Canciani MT, Goudemand J, Peake I, Goodeve A, MCMDM-1VWD Study Group. VWF propeptide and ratios between VWF, VWF propeptide, and FVIII in the characterization of type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2013;121:2336–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Casari C, Lenting P, Wohner N, Christophe O, Denis C. Clearance of von Willebrand factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nichols WL, Rick ME, Ortel TL, Montgomery RR, Sadler JE, Yawn BP, James AH, Hultin MB, Manco-Johnson MJ, Weinstein M. Clinical and laboratory diagnosis of von Willebrand disease: a synopsis of the 2008 NHLBI/NIH guidelines. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:366–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Seidizadeh O, Ciavarella A, Baronciani L, Boggio F, Ballardini F, Cozzi G, Colpani P, Pagliari MT, Novembrino C, Siboni SM, Peyvandi F. Clinical and laboratory presentation and underlying mechanism in patients with Low VWF. Thromb Haemost. 2024;124:340–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Swystun LL, Lillicrap D. Genetic regulation of plasma von Willebrand factor levels in health and disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:2375–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Smith NL, Chen MH, Dehghan A, Strachan DP, Basu S, Soranzo N, Hayward C, Rudan I, Sabater-Lleal M, Bis JC, de Maat MP, Rumley A, Kong X, Yang Q, Williams FM, Vitart V, Campbell H, Mälarstig A, Wiggins KL, Van Duijn CM, et al. Novel associations of multiple genetic loci with plasma levels of factor VII, factor VIII, and von Willebrand factor: the CHARGE (Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genome Epidemiology) Consortium. Circulation. 2010;121:1382–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sabater-Lleal M, Huffman JE, de Vries PS, Marten J, Mastrangelo MA, Song C, Pankratz N, Ward-Caviness CK, Yanek LR, Trompet S, Delgado GE, Guo X, Bartz TM, Martinez-Perez A, Germain M, de Haan HG, Ozel AB, Polasek O, Smith AV, Eicher JD, et al. Genome-wide association transethnic meta-analyses identifies novel associations regulating coagulation factor VIII and von Willebrand factor plasma levels. Circulation. 2019;139:620–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].O’Brien LA, James PD, Othman M, Berber E, Cameron C, Notley CR, Hegadorn CA, Sutherland JJ, Hough C, Rivard GE, O’Shaunessey D, Lillicrap D, Association of Hemophilia Clinic Directors of Canada. Founder von Willebrand factor haplotype associated with type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2003;102:549–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Christopherson PA, Tijet N, Haberichter SL, Flood VH, Ross J, Notley C, Rawley O, Montgomery RR, , Zimmerman Project Investigators, James PD, Lillicrap D. The common VWF variant p. Y1584C: detailed pathogenic examination of an enigmatic sequence change. J Thromb Haemost. 2024;22:666–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Baronciani L, Goodeve A, Peyvandi F. Molecular diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2017;23:188–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zimmerman TS, Dent JA, Ruggeri ZM, Nannini LH. Subunit composition of plasma von Willebrand factor. Cleavage is present in normal individuals, increased in IIA and IIB von Willebrand disease, but minimal in variants with aberrant structure of individual oligomers (types IIC, IID, and IIE). J Clin Invest. 1986;77:947–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Seidizadeh O, Baronciani L, Pagliari MT, Cozzi G, Colpani P, Cairo A, Siboni SM, Biguzzi E, Peyvandi F. Phenotypic and genetic characterizations of the Milan cohort of von Willebrand disease type 2. Blood Adv. 2022;6:4031–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Baronciani L, Peyvandi F. How we make an accurate diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Thromb Res. 2020;196:579–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Schneppenheim R, Michiels JJ, Obser T, Oyen F, Pieconka A, Schneppenheim S, Will K, Zieger B, Budde U. A cluster of mutations in the D3 domain of von Willebrand factor correlates with a distinct subgroup of von Willebrand disease: type 2A/IIE. Blood. 2010;115:4894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hommais A, Stépanian A, Fressinaud E, Mazurier C, Pouymayou K, Meyer D, Girma JP, Ribba AS. Impaired dimerization of von Willebrand factor subunit due to mutation A2801D in the CK domain results in a recessive type 2A subtype IID von Willebrand disease. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:776–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Federici AB, Mannucci PM, Castaman G, Baronciani L, Bucciarelli P, Canciani MT, Pecci A, Lenting PJ, De Groot PG. Clinical and molecular predictors of thrombocytopenia and risk of bleeding in patients with von Willebrand disease type 2B: a cohort study of 67 patients. Blood. 2009;113:526–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Sacco M, Lancellotti S, Ferrarese M, Bernardi F, Pinotti M, Tardugno M, De Candia E, Di Gennaro L, Basso M, Giusti B, Papi M, Perini G, Castaman G, De Cristofaro R. Noncanonical type 2B von Willebrand disease associated with mutations in the VWF D′ D3 and D4 domains. Blood Adv. 2020;4:3405–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nurden P, Debili N, Vainchenker W, Bobe R, Bredoux R, Corvazier E, Combrie R, Fressinaud E, Meyer D, Nurden AT, Enouf J. Impaired megakaryocytopoiesis in type 2B von Willebrand disease with severe thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2006;108:2587–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Nurden P, Gobbi G, Nurden A, Enouf J, Youlyouz-Marfak I, Carubbi C, La Marca S, Punzo M, Baronciani L, De Marco L, Vitale M, Federici AB. Abnormal VWF modifies megakaryocytopoiesis: studies of platelets and megakaryocyte cultures from patients with von Willebrand disease type 2B. Blood. 2010;115:2649–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Casari C, Berrou E, Lebret M, Adam F, Kauskot A, Bobe R, Desconclois C, Fressinaud E, Christophe OD, Lenting PJ, Rosa JP, Denis CV, Bryckaert M. von Willebrand factor mutation promotes thrombocytopathy by inhibiting integrin αIIbβ3. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5071–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kanaji S, Morodomi Y, Weiler H, Zarpellon A, Montgomery RR, Ruggeri ZM, Kanaji T. The impact of aberrant von Willebrand factor-GPIbα interaction on megakaryopoiesis and platelets in humanized type 2B von Willebrand disease model mouse. Haematologica. 2022;107:2133–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Legan ER, Liu Y, Arce NA, Parker ET, Lollar P, Zhang XF, Li R. Type 2B von Willebrand disease mutations differentially perturb auto-inhibition of the A1 domain. Blood. 2023;141:1221–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Othman M, Gresele P. Guidance on the diagnosis and management of platelet-type von Willebrand disease: a communication from the Platelet Physiology Subcommittee of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1855–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Seidizadeh O, Mollica L, Zambarbieri S, Baronciani L, Cairo A, Colpani P, Cozzi G, Pagliari MT, Ciavarella A, Siboni SM, Peyvandi F. Type 2M/2A von Willebrand disease: a shared phenotype between type 2M and 2A. Blood Adv. 2024;8:1725–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Doruelo AL, Haberichter SL, Christopherson PA, Boggio LN, Gupta S, Lentz SR, Shapiro AD, Montgomery RR, Flood VH. Clinical and laboratory phenotype variability in type 2M von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:1559–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Maas DPMSM, Atiq F, Blijlevens NMA, Brons PPT, Krouwel S, Laros van Gorkom BAP, Leebeek FWG, Nieuwenhuizen L, Schoormans SCM, Simons A, Meijer D, van Heerde WL, Schols SEM. von Willebrand disease type 2M: correlation between genotype and phenotype. J Thromb Haemost. 2022;20:316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Seidizadeh O, Peyvandi F, Mannucci PM. von Willebrand disease type 2N: an update. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:909–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gupta M, Lillicrap D, Stain AM, Friedman KD, Carcao MD. Therapeutic consequences for misdiagnosis of type 2N von Willebrand disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1081–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zadeh OS, Ahmadinejad M, Amoohossein B, Homayoun S. Are Iranian patients with von Willebrand disease type 2N properly differentiated from hemophilia A and do they receive appropriate treatment? Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2020;31:382–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Pérez-Rodríguez A, Batlle J, Pinto JC, Corrales I, Borràs N, Garcia-Martínez I, Cid AR, Bonanad S, Parra R, Mingot-Castellano ME, Navarro N, Altisent C, Pérez-Montes R, Moretó A, Herrero S, Soto I, Mosteirín NF, Jiménez-Yuste V, Jacob AA, Fontanes E, et al. Type 2N VWD: conclusions from the Spanish PCM-EVW-ES project. Haemophilia. 2021;27:1007–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Casonato A, Cozzi MR, Ferrari S, Rubin B, Gianesello L, De Marco L, Daidone V. The lesson learned from the new c.2547-1G > T mutation combined with p.R854Q: when a type 2N mutation reveals a quantitative von Willebrand factor defect. Thromb Haemost. 2022;122:1479–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Casonato A, Sartorello F, Cattini MG, Pontara E, Soldera C, Bertomoro A, Girolami A. An Arg760Cys mutation in the consensus sequence of the von Willebrand factor propeptide cleavage site is responsible for a new von Willebrand disease variant. Blood. 2003;101:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Hilbert L, Nurden P, Caron C, Nurden AT, Goudemand J, Meyer D, Fressinaud E, Mazurier C, INSERM Network on Molecular Abnormalities in von Willebrand Disease. Type 2N von Willebrand disease due to compound heterozygosity for R854Q and a novel R763G mutation at the cleavage site of von Willebrand factor propeptide. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Baronciani L, Peake I, Schneppenheim R, Goodeve A, Ahmadinejad M, Badiee Z, Baghaipour MR, Benitez O, Bodó I, Budde U, Cairo A, Castaman G, Eshghi P, Goudemand J, Hassenpflug W, Hoorfar H, Karimi M, Keikhaei B, Lassila R, Leebeek FWG, et al. Genotypes of European and Iranian patients with type 3 von Willebrand disease enrolled in 3WINTERS-IPS. Blood Adv. 2021;5:2987–3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bowman M, Lillicrap D, James P. The genetics of Canadian type 3 von W illebrand disease: further evidence for codominant inheritance of mutant alleles: a reply to a rebuttal. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1786–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Eikenboom JC. Congenital von Willebrand disease type 3: clinical manifestations, pathophysiology and molecular biology. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2001;14:365–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Pagliari MT, Budde U, Baronciani L, Eshghi P, Ahmadinejad M, Badiee Z, Baghaipour MR, Benítez Hidalgo O, Biguzzi E, Bodó I, Castaman G, Goudemand J, Karimi M, Keikhaei B, Lassila R, Leebeek FWG, Lopez Fernandez MF, Marino R, Oldenburg J, Peake I, et al. von Willebrand factor neutralizing and non-neutralizing alloantibodies in 213 subjects with type 3 von Willebrand disease enrolled in 3WINTERS-IPS. J Thromb Haemost. 2023;21:787–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Baronciani L, Federici A, Cozzi G, Canciani M, Mannucci P. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant von Willebrand factor (VWF) with combined type 2B and type 1 defects in the VWF gene in two patients with a type 2A phenotype of von Willebrand disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Eikenboom J, Hilbert L, Ribba AS, Hommais A, Habart D, Messenger S, Al-Buhairan A, Guilliatt A, Lester W, Mazurier C, Meyer D, Fressinaud E, Budde U, Will K, Schneppenheim R, Obser T, Marggraf O, Eckert E, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, et al. Expression of 14 von Willebrand factor mutations identified in patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease from the MCMDM-1VWD study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1304–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Golder M, Pruss CM, Hegadorn C, Mewburn J, Laverty K, Sponagle K, Lillicrap D. Mutation-specific hemostatic variability in mice expressing common type 2B von Willebrand disease substitutions. Blood. 2010;115:4862–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ng CJ, Liu A, Venkataraman S, Ashworth KJ, Baker CD, O’Rourke R, Vibhakar R, Jones KL, Di Paola J. Single-cell transcriptional analysis of human endothelial colony-forming cells from patients with low VWF levels. Blood. 2022;139:2240–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Starke RD, Paschalaki KE, Dyer CE, Harrison-Lavoie KJ, Cutler JA, McKinnon TA, Millar CM, Cutler DF, Laffan MA, Randi AM. Cellular and molecular basis of von Willebrand disease: studies on blood outgrowth endothelial cells. Blood. 2013;121:2773–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Deans ZC, Ahn JW, Carreira IM, Dequeker E, Henderson M, Lovrecic L, Õunap K, Tabiner M, Treacy R, van Asperen CJ. Recommendations for reporting results of diagnostic genomic testing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30:1011–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Goodeve A, Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Federici A, Batlle J, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Eikenboom J, Schneppenheim R, Budde U, Ingerslev J, Habart D, Vorlova Z, Holmberg L, Lethagen S, Pasi J, Hill F, Hashemi-Soteh MB, Baronciani L, et al. Rate of de novo VWF mutations in patients historically diagnosed with type 1 VWD in the European study, molecular and clinical markers for the diagnosis and management of type 1 VWD (MCMDM-1VWD). J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5. PT–189. [Google Scholar]

- [87].James PD, Goodeve AC. von Willebrand disease. Genet Med. 2011;13:365–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kernohan KD, Boycott KM. The expanding diagnostic toolbox for rare genetic diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2024; in press. 10.1038/s41576-023-00683-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Corrales I, Catarino S, Ayats J, Arteta D, Altisent C, Parra R, Vidal F. High-throughput molecular diagnosis of von Willebrand disease by next generation sequencing methods. Haematologica. 2012;97:1003–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Liang Q, Qin H, Ding Q, Xie X, Wu R, Wang H, Hu Y, Wang X. Molecular and clinical profile of VWD in a large cohort of Chinese population: application of next generation sequencing and CNVplex® technique. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1534–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]