Abstract

Purpose:

To assess long-term visual and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) after strabismus surgery.

Methods:

A consecutive sample of five children with CZS who underwent strabismus surgery was enrolled. All children underwent a standardized pre- and postoperative protocol including binocular best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) using the Teller Acuity Cards II (TAC II), ocular alignment, functional vision using the functional vision developmental milestones test (FVDMT), and neurodevelopmental milestone evaluation using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development-Third Edition (BSID-III). Scores of the FVDMT outcomes considering the child’s developmental age based on the BSID-III score were compared with scores from postoperative assessment.

Results:

Five children with CZS (3 girls, 2 boys) were enrolled with a mean age at baseline (preoperative) of 35.0 ± 0.7 months (range, 34 - 36 months) and at final assessment of 64.4 ± 0.5 months (range, 64 - 65 months). Preoperative BCVA was 1.2 ± 0.5 logMAR and at final assessment 0.7 ± 0.1 logMAR. Successful strabismus surgery outcome was maintained in 4/5 (80.0%) of children at final assessment. The children’s BSID-III scores showed significant neurodevelopment delay at initial assessment (corresponding developmental mean age was 4.7 months) and at their final assessment (corresponding developmental mean age was 5.1 months). There was improvement or stability in 34/46 items evaluated in the FVDMT (73.9%) when comparing baseline with 2-year follow-up.

Conclusions:

Strabismus surgery resulted in long-term ocular alignment in the majority of children with CZS. All the children showed improvement or stability in more than 70.0% of the functional vision items assessed. Visual and neurodevelopmental dysfunction may be related to complex condition and associated disorders seen in CZS including ocular, neurological, and skeletal abnormalities.

Keywords: Congenital Zika syndrome, cerebral visual impairment, strabismus, surgery, visual outcome, neurodevelopment

INTRODUCTION

The Zika virus (ZIKV) was first isolated from rhesus monkeys in the Zika forest, Uganda, in 1947, and later isolated in humans with mild illness during an outbreak of jaundice in eastern Nigeria1. In 2015, the virus rapidly spread in Brazil and several other countries in the Americas, followed by an increased number of notification cases of children born with microcephaly and other neurologic conditions2-4.

The morphological and clinical features that characterize the congenital Zika syndrome (CZS) include multiple neurological, skeletal, and ocular abnormalities as well as hearing and visual impairment5. In the central nervous system (CNS), the ZIKV infects progenitor cells of the developing brain leading to destructive, calcification, hypoplasia, and migration disturbances6,7. The spectrum of ZIKV-induced brain injury includes malformations and calcifications, most located along the cortical and subcortical white matter junction and the basal ganglia8, but also the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system are affected7. The visual pathway damage in CZS includes abnormalities of the occipital cortex, chiasmal atrophy, and optic nerve such as hypoplasia, atrophy, and calcification9.

Fundus findings including retinal lesions and optic nerve abnormalities were described in up to 55% of children with CZS10-14. However, studies showed that visual impairment in CZS results not only from ocular findings but also from CNS visual pathway damage caused by the ZIKV, which characterizes cortical visual impairment (CVI)9,13.

Oculomotility disorders including early-onset strabismus are commonly seen in children with CZS15. Population-based studies about strabismus have estimated a prevalence of approximately 2–4% in the pediatric population16,17, compared to 92% in children with CZS18. It is well known that this oculomotor condition is the most frequent cause of amblyopia and contributes to childhood visual impairment, but it can also be a consequence of poor visual acuity or visual impairment19,20. Moreover, ocular misalignment may be associated with poor visual-motor performance, which can affect the ability to perform basic functional tasks of daily living, including hand–eye coordination, gross and fine motor skills, self-image, and social interactions19,20.

Given that CZS is a new entity, several questions about the course of CZS remain unanswered. They pose significant challenge to healthcare professionals when managing these children. Our group was the first to report the favorable visual outcome of strabismus surgery in children with CZS at the 6-months after surgery with beneficial effects on ocular alignment, expansion of the visual field, and child's social, functional, and behavioral skills21. We report herein the long-term surgical outcome as well as the visual and neurodevelopment outcomes in the same set of children with CZS submitted to strabismus surgery.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants and Data Collection

In this prospective, consecutive, interventional case series study, the same 5 participants from our previous study were enrolled21. All children received early intervention rehabilitation services at the Rehabilitation Center of the Altino Ventura Foundation beginning at the first months of life, including visual and hearing assessments, occupational therapy, physical therapy, as well as speech, and language therapy.

The study participants were submitted to the following protocol: demographic and clinical data collection; visual and neurodevelopment evaluation. Data collection took place between April 2018 and April 2021. The demographic and clinical data of the studied sample has been previously published by our group21. To classify gestational age (GA), babies were considered full-term when born at ≥ 37 weeks, and premature when born at < 37 weeks13. In the present study, we describe the ocular alignment, visual acuity, functional vision, and neurodevelopment recorded pre-operatively (baseline) and postoperatively (3-6 months, 1 year, and 2 years after surgery). All caregivers signed a consent form prior to enrollment. This study received the approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo and Altino Ventura Foundation, according to National Health Council, Ministry of Health, Brazil (protocol numbers: 4.286.547 and 4.241.155, respectively).

Previous Surgical Procedure

All patients were submitted to strabismus surgery under general anesthesia. Surgical planning was based on the near measurements given that all children had visual impairment. The smallest angle of deviation measured in primary position was considered and a hypocorrection was performed to avoid overcorrection. Successful strabismus surgery was considered when child did not require additional horizontal strabismus surgery and residual horizontal deviation at the final recorded visit was ≤10 prism diopters (PD), as described in our previous publication21.

Visual Assessment

Preoperative and long-term ophthalmological assessments, including ocular alignment and binocular BCVA using the TAC II (Stereo Optical Co Inc., Chicago, IL), were performed by the same group of pediatric ophthalmologists using the same protocol described in our previous publication21.

Visual acuity (VA) data was compared with age-related reference acuity norms and reference values for categorization of visual status and classified as very low vision (< 1.6 cy/deg), low vision (1.6-9.6 cy/deg), near-normal vision (9.6-26.0 cy/deg), and normal vision (>26.0 cy/deg)22.

Visual impairment classification was based on binocular BCVA using the World Health Organization International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD-10): category 0 = mild or no visual impairment (BCVA ≤ 20/70); category 1 = moderate visual impairment (BCVA > 20/70 – 20/200); category 2 = severe visual impairment (BCVA > 20/200 – 20/400); category 3 = blindness (BCVA > 20/400 – 20/1200; category 4 = Blindness (BCVA > 20/1.200 – light perception); category 5 = Blindness (BCVA = no light perception)23.

Ocular alignment was assessed using the Krimsky Test at near fixation given children’s visual impairment. Significant refractive error was considered and corrected when hyperopia was 2.00 diopters (D) or greater, or myopia or astigmatism was 1.00 D or greater21.

Preoperative and long-term assessment of functional vision was performed using the Functional Vision Developmental Milestones Test (FVDMT) to determine how well the child used vision in daily tasks. Children were tested and retested by the same examiner, a certified occupational therapist, in different days, in the same setting, using the same materials and the same battery test. The assessment was binocular and those children that needed correction were using their glasses during the evaluation. The FVDMT test is based on Hyvarinen (2017)24, Chen and colleagues (2015)25, on the Parents and Their Infants with Visual Impairments (PAIVI), and related to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) and patient characteristics26,27. The FVDMT is used to measure the child’s visual behavior when recognizing and responding to environment stimulus, as well as performing tasks. This instrument is composed of 43-items, age-standardized, and organized into clusters of items age-related visual-perceptual, behavior/response, reference up to 12-24 months. Children with CZS present visual impairment and motor delays. Vision-related tasks items that required motor response or manipulation of objects were excluded from the study’s protocol to avoid misinterpretation.

Therefore, 18 items of the FVDMT scale were used for the current study and 18 was the maximum score that these children could obtain. In addition, the items in the FVDMT instrument are age-related: 1 – 2 month (eye contact and located face without vocalization at near – 30 cm); 3 – 4 months (social smile, regards hand, follow object horizontally, and follows object presented in lower vertical trajectory); 5 – 6 months (goal-directed for reach, fixes object at 3 meters, and fix small object and try to catch); 7 – 1 months (recognition facial features, interest in printed figures, and search partially hidden objects); and 11 – 12 months (explore an object can operate it according to the function and visually follow or search for objects thrown to the ground). In the present study, each child was assessed considering their BSID-III developmental age results18. For statistical analysis, the items achieved by each child were added individually and divided by the total number of items tested.

Our previous research has standardized this instrument in children with CZS aged up to 11-12 months measuring functional vision and visual developmental milestone29. The administration of the FVDMT instrument to the children with CZS had an average duration of 30 minutes. Each item was rated according to International Classification Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) rate code26: 0 - normal or near-normal visual behavior; 1 - mild visual dysfunction; 2 - moderate visual dysfunction; 3 - severe visual dysfunction; 4 - profound visual dysfunction; 8 - inconclusive visual behavior; 9 - non-applicable. We compared preoperative (baseline) scores with the last postoperative (more than 2 years after surgery) assessment. Baseline scores were compared to the postoperative scores (3-6 months), and these scores were compared to the long-term results (more than 2 years after surgery) to determine improvement, stabilization, or deterioration. Inconclusive visual behavior results (code 8) were not considered within the analysis.

Neurodevelopment Assessment

The neurodevelopment evaluation in each child was performed using the BSID-III and applied by a certified therapist. The BSID-III instrument was translated to Brazilian Portuguese, culturally adapted, and has been tested and approved for developmental functioning outcomes in children28. It is considered a widely used norm-referenced measure of infant development spanning five key developmental domains of development-cognition: language (receptive and expressive communication), motor (gross and fine), social-emotional, and adaptive behavior. Administration adaptations suggested by the BSID-III manual were done to better assess the studied population28. The BSID-III assessment took an average of 45 minutes per child due to visual and motor impairments.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses (Jamovi version 2.3.28) were performed for continuous variables (expressed as mean ± standard deviation). Categorical variables were expressed by their absolute and relative frequencies.

RESULTS

Five children with CZS (3 girls, 2 boys) who underwent strabismus surgery (4 with esotropia and 1 with exotropia) between October and November 2018 were enrolled in this study. All children had significant refractive errors, and 3 (60.0%) had nystagmus. Four children (80.0%) have microcephaly, of which 3 (60.0%) have severe microcephaly (<3 SDs below the mean head circumference). Three children (60.0%) were premature. Seizures were controlled with medication in all children. Clinical and ophthalmological characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and ophthalmologic characteristics of children with congenital Zika syndrome that underwent strabismus surgery.

| Characteristics | Case | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Clinical | |||||

| Gestacional age, at birth (weeks) | 35.0 | 37.4 | 40.0 | 36.0 | 31.0 |

| Microcephaly | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cerebral Palsy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Epilepsy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hydrocephalus | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| VPS | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Hearing Loss | N | N | N | N | N |

| Behavioral problems | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ocular | |||||

| Visual impairment | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Photophobia | N | Y | N | N | Y |

| Esotropiaa | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Exotropiaa | N | N | N | N | Y |

| Nystagmus | N | Yb | Yc | Yb | N |

| Significant RE | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Abnormal optic nerved | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Abnormal Retinae | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

Y- Yes; N- No; VPS – Ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery; RE – Refractive error.

Preoperative Strabismus

Manifest nystagmus.

Latent nystagmus

Abnormal optic nerve: Hypoplasia, Increased disc cupping, Pallor.

Abnormal retina: Pigment mottling, Chorioretinal scar, Hypochromic lesions.

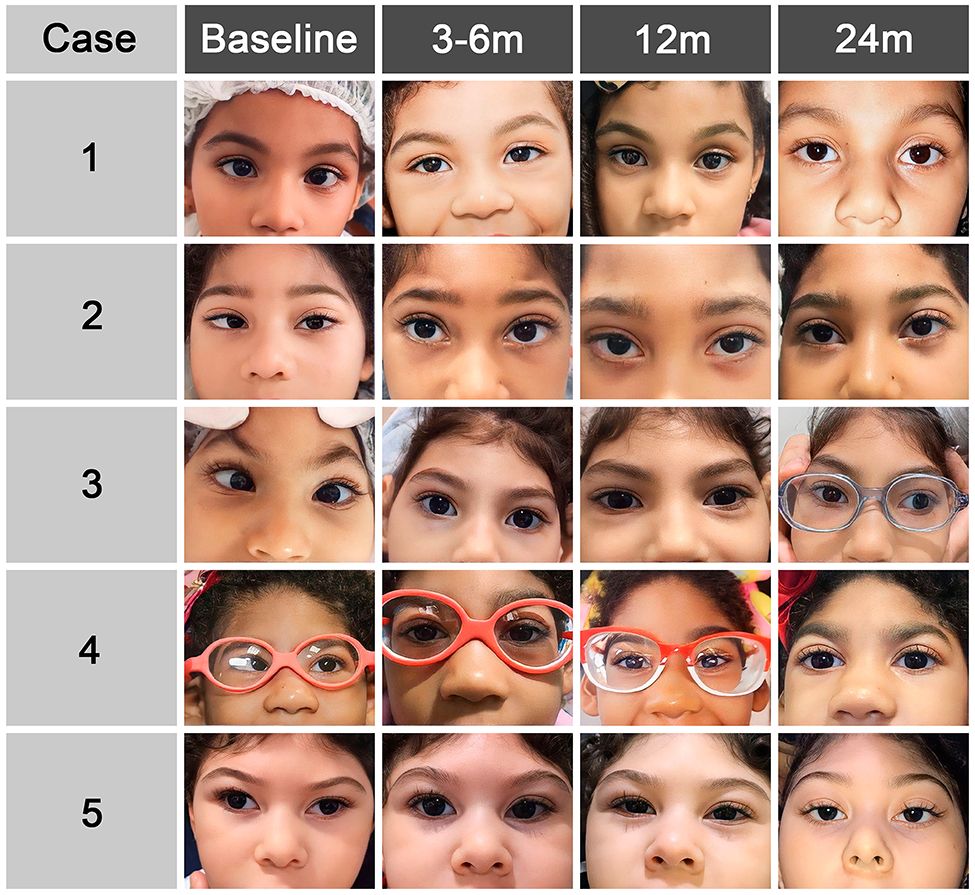

The mean age at baseline (preoperatively) was 35.0 ± 0.7 months (range, 34 - 36 months), and at final assessment (more than 2 years after surgery) was 64.4 ± 0.5 months (range, 64 - 65 months). The mean age at surgery was 36.4 ± 0.9 months (range, 35 - 37 months). The mean postoperative follow-up time was 29.6 ± 0.6 months (range, 29 - 30 months). Successful surgical outcome long-term was observed in 4/5 (80.0%) of children at long-term follow-up. (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Surgical procedure and ocular motility in primary position at preoperative (baseline) and postoperative (3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months).

| Case | Surgical procedure (mm) |

Ocular Motility in Primary Position | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 3 - 6 | 12 | 24 | ||

| (Months) | |||||

| 1 | BMR= 4.0 | ET=35 PD | O | O | O |

| 2 | OD MR= 6.5, SRT; OS MR= 5.0, SRT | ET=40 PD | O | O; DVD= 15 PD (OS) | O; DVD= 15 PD (OS) |

| 3 | BMR= 5.5 | ET=50 PD (DS) | O – XT=16 PD (DS) | O – XT=16 PD (DS) | O – XT=25 PD (DS) |

| 4 | BMR= 5.0 | ET=40 PD | O | O | O |

| 5 | BLR= 11.0; OS MRc=4.0; BSOT | XT=65 PD; OASO OU | O | O | O |

Preoperative alignment in primary position: B – Baseline; Postoperative alignment in primary position: 3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months. At near (33 centimeters).

Surgical procedure: BMR = Bilateral medial rectus recessions; MR = Medial rectus recession; SRT = Superior rectus transposition; BLR = Bilateral lateral rectus recession; MRc = Medial rectus resection; BSOT = Bilateral superior oblique tenectomy performed temporally;

OD = Right eye; OS = Left eye; OU = Both eyes; PD = Prism diopters; O = Orthotropic; ET = Esotropia; XT = Exotropia; DS = Dyskinetic strabismus; DVD = Dissociated vertical deviation; OASO = Overaction superior oblique.

Figure 1.

The preoperative binocular BCVA (with TAC® II) was 1.2 ± 0.5 LogMAR and at final assessment was 0.7 ± 0.1 LogMAR. Binocular BCVA (with TAC® II) at baseline and follow-up examinations compared with age-related reference ranges showed visual impairment in all children. At baseline, two children (40.0%) had moderate visual impairment (cases 1 and 3), two (40.0%) had blindness (cases 4 and 5), and one (20.0%) had severe visual impairment. (Table 3).

Table 3.

Visual acuity assessment, vision categorization, and visual impairment classification of children with congenital Zika syndrome that underwent strabismus surgery at preoperatory (baseline) and postoperative (3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months).

| Patient | BCVA-OU | Vision Categorizationa |

Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycles/cm | Distance measured (cm) |

Visual impairment b | |||

| B | 1 | 4.8 | 55 | LV | 1 |

| 2 | 2.4 | 38 | LV | 2 | |

| 3 | 6.5 | 55 | LV | 1 | |

| 4 | 1.3 | 55 | VLV | 3 | |

| 5 | 0.43 | 38 | VLV | 4 | |

| 3-6 m | 1 | 3.2 | 84 | LV | 1 |

| 2 | 2.4 | 55 | LV | 2 | |

| 3 | 3.2 | 84 | LV | 1 | |

| 4 | 0.86 | 38 | VLV | 3 | |

| 5 | 2.4 | 38 | LV | 2 | |

| 12 m | 1 | 3.2 | 84 | LV | 1 |

| 2 | 3.2 | 55 | LV | 1 | |

| 3 | 4.8 | 84 | LV | 1 | |

| 4 | 0.86 | 84 | VLV | 3 | |

| 5 | 0.43 | 38 | VLV | 4 | |

| 24 m | 1 | 4.8 | 84 | LV | 1 |

| 2 | 3.2 | 84 | LV | 1 | |

| 3 | 3.2 | 84 | LV | 1 | |

| 4 | 4.8 | 38 | LV | 1 | |

| 5 | 2.4 | 84 | LV | 2 | |

Preoperative visual acuity: B – Baseline; Postoperative visual acuity: 3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months.

m – Month; cm – Centimeter; VA – Visual acuity; BCVA-OU – Binocular best corrected visual acuity measured with Teller Acuity Cards (TAC) II; LP – Light perception.

Categorization of vision based on TAC II findings: VLV = very low vision (< 1.6 cy/deg); LV= Low vision (1.6-9.6 cy/deg); NNV= near normal vision (9.6-26.0 cy/deg); N= Normal vision ( > 26.0 cy/deg).

Visual impairment classification based on Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10): 0 = Mild or No visual impairment, VA as ≥ 20/70; 1 = Moderate visual impairment, VA as < 20/70 – 20/200; 2 = Severe visual impairment, VA as < 20/200 – 20/400; 3 = Blindness, VA as < 20/400 – 20/1.200; 4 = Blindness, VA as < 20/1.200 – LP; 5 = Blindness, VA as No LP.

The neurodevelopmental assessment (BSID-III) was performed at baseline at 30.2 ± 1.3 months (range, 29 - 32 months) and long-term at 64.6 ± 0.6 months (range, 64 - 65 months). The children’s mean developmental age at initial assessment was 4.7 months and at final assessment was 5.1 months. Long-term follow-up in these children showed slight motor (gross and fine) skills improvement in 4/5 children (80.0%) and cognitive improvement in 3/5 cases (60.0%).

The FVDMT scale results were described in Table 4. The items of “1-2 months” were assessed in all 5 children. The items of “3 – 4 months” were assessed in cases 1, 2, 3, and 4. The items of “5 – 6 months” were assessed in cases 1 and 3. The items of “7 – 10 months” was assessed only in case 1. The items of “11 – 12 months” was assessed in only case 1.

Table 4.

Functional vision milestones assessments outcomes of children with congenital Zika syndrome operated of strabismus at preoperatory (Baseline) and postoperative (3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months).

| Case 1 | Follow-up (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 3 | 12 | 24 | |

| Age (months) a | 8 (36) | 11.3 (40) | 12.6 (48) | 11.3 (65) |

| 1-2 months | ||||

| Eye contact | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Locate face without vocalization at near (30 cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Imitate facial expression | 8 | 4 | 0 | 8 |

| 3-4 months | ||||

| Social smile | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Regards hands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Follow object horizontally | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Follows object presented in lower vertical trajectory | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Moves to reach | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5-6 months | ||||

| Goal-directed for reach | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Fixes object at 3 meters | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fix small object and try to catch | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7-10 months | ||||

| Recognition facial features | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interest in printed figures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Search partially hidden objects | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11-12 months | ||||

| Explore an object can operate it according to the function | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Visually follow or search for objects thrown to the ground | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Case 2 | B | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| Age (months) a | 4.4 (36) | 4 (40) | 3.7 (48) | 3.4 (64) |

| 1-2 months | ||||

| Eye contact | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Locate face without vocalization at near (30 cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Imitate facial expression | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 3-4 months | ||||

| Social smile | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Regards hands | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Follow object horizontally | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Follows object presented in lower vertical trajectory | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Moves to reach | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Case 3 | B | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| Age (months) a | 5 (36) | 4.1 (39) | 5 (43) | 5.3 (65) |

| 1-2 months | ||||

| Eye contact | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Locate face without vocalization at near (30 cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Imitate facial expression | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 3-4 months | ||||

| Social smile | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Regards hands | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Follow object horizontally | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Follows object presented in lower vertical trajectory | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Moves to reach | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 5-6 months | ||||

| Goal-directed for reach | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Fixes object at 3 meters | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fix small object and try to catch | 2 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| Case 4 | B | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| Age (months) a | 1.8 (35) | 3 (39) | 3 (48) | 3.4 (64) |

| 1-2 months | ||||

| Eye contact | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Locate face without vocalization at near (30 cm) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Imitate facial expression | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| 3-4 months | ||||

| Social smile | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Regards hands | 8 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| Follow object horizontally | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Follows object presented in lower vertical trajectory | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Moves to reach | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Case 5 | B | 3 | 12 | 24 |

| Age (months) a | 2.1 (37) | 1.5 (40) | 2.1 (50) | 1.0 (65) |

| 1-2 months | ||||

| Eye contact | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Locate face without vocalization at near (30 cm) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Imitate facial expression | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

Preoperative functional vision milestones: B – Baseline; Postoperative functional vision milestones: 3-6 months, 12 months, 24 months.

Bayley age (Chronological age); 0 - typical or near-typical vision; 1 - slight visual functioning problem; 2 - moderate visual functioning problem; 3 - serious/considerable visual functioning problem; 4 - complete visual functioning problem; 8 - non-specified; 9 - non-applicable

Case 1 showed improvement in 2/16 (12.5%) items when comparing baseline and last postoperative assessment. Furthermore, stabilization was obtained in 10/16 (62.5%) items in the last postoperative assessment. Thus, a total of 12/16 (75.0%) items were obtained or maintained over a 2-year period.

Case 2 showed improvement in 1/8 (12.5%) items when comparing baseline and last postoperative assessment. Furthermore, stabilization was obtained in 5/8 (62.5%) items in the last postoperative assessment. Thus, a total of 6/8 (75.0%) items were obtained or maintained over a 2-year period.

Case 3 improved 2/11 (18.2%) items when comparing baseline and last postoperative assessment. Furthermore, stabilization was obtained in 4/11 (36.4%) items in the last postoperative assessment. Thus, a total of 6/11 (54.5%) items were obtained or maintained over a 2-year period.

Case 4 showed improvement in 2/8 (25.0%) items when comparing baseline and last postoperative assessment. Furthermore, stabilization was obtained in 5/8 (62.5%) items in the last postoperative assessment. Thus, a total of 7/8 (87.5%) items were obtained or maintained over a 2-year period.

Case 5 showed stabilization in the 3/3 (100.0%) items when comparing baseline and last postoperative assessment but presented stabilization in all these items.

Comparison of functional vision developmental data (FVDMT scale) measured preoperatively (baseline) with the immediate postoperative (3-6 months) showed an improvement in 13/46 (28.3%) items, stabilization in 30/46 (65.2%) items, deterioration in 1/46 (2.2%) items, and inconclusive in 2/46 (4.3%) items. When comparing baseline with the long-term results (24 months), an improvement or stability was observed in 34/46 items (73.9%).

DISCUSSION

Children born with CZS frequently have cerebral palsy (CP) and CVI13,15,29. These neurological disorders often occur with oculomotor dysfunction and significant visual and neurodevelopmental delays30,31. In CZS, findings such as refractive errors, poor accommodation, and oculomotor system dysmotility are common and may contribute to the worsening of visual impairment10,13,18,21,29. Little is known about the course and prognosis of visual development in children with CZS13. However, Ventura et al (2017)18 reported immediate improvement in binocular vision in 62% of the children with CZS with the use of eyeglasses for correction of the refractive error and of the deficit of accommodation. Therefore, thorough evaluations, close follow-ups, and early intervention during this sensitive period of neuroplasticity may offer the possibility of improvement18,21.

The children in our series have been evaluated by a multidisciplinary team since birth. They were carefully selected for strabismus surgery after formal neurologic assessment including controlled seizures and stable medical status21. Pre- and postoperative visual and developmental assessments were made by the same examiners. Thus, our study is the first to access the long-term visual and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with CZS that underwent strabismus surgery.

It is well known that strabismus interferes with binocular vision and stereopsis development, which may lead to early visual impairment17,19. Management of strabismus in children who are visually impaired and with additional neurological abnormalities remains a challenge32. Although surgical correction of the strabismus in children with developmental delay is well tolerated and effective, the success rate remains less predictable, and reoperations are common. In patients with CVI spontaneous resolution of strabismus occur in the minority of the cases (16%) and satisfactory surgical outcomes can be achieved in most of the cases (56%)33. In addition, half of children with CVI have CP associated, which is more related to worse long-term surgical outcomes than children that have CVI without CP34. Therefore, complete pre-operatory ophthalmological and clinical evaluations as well as meticulous surgical planning considering adjustments are necessary in this population33.

Although studies have shown that standard strabismus surgery in delayed children can present unpredictable outcomes32,34, the present study showed a high success rate (80.0%) of satisfactory long-term surgical outcome. Only one child (20.0%), case 3, required reoperation for consecutive exotropia and one child (case 2) presented an intermittent vertical deviation (DVD) postoperatively with satisfactory control that did not require surgical intervention.

The main purpose of strabismus surgery in children with neurologic conditions is to promote visual function improvement, psychosocial health, and quality of life35,36. Michieletto et al (2020)37 have shown additional motor skills improvement in children with Angelman’s syndrome submitted to strabismus surgery. Ventura et al (2020)21 also observed improvement in the ocular alignment and expansion of the temporal visual field in children with CZS that underwent strabismus surgery, as well as behavioral improvement in daily activities, detection of peripheral targets, and socialization skills. Thus, surgical intervention in delayed children may promote other gains such as functional, social, and behavioral in additional to ocular alignment34.

The visual acuity of our sample at baseline varied but was mostly poor. This is probably related to the extent of the visual and CNS damage9. Moreover, clinical markers for worse visual outcome include the presence of prematurity38 and comorbidities including seizures, as well as the use of neurological medications 13,30,31. In our sample, all children had seizures and three children were premature.

Improvement of visual acuity observed over time after strabismus surgery may have been associated to other factors such as visual maturation. In typically developing children there is a clear relationship between the increase of visual acuity and age and there is attainment of crucial developmental milestone during early childhood39,40. In contrast, children with CZS present congenital ocular alterations as well as maldevelopment of key visual processing pathways (CVI), which affects visual function and visual development9,13. In addition, studies have shown a high prevalence of strabismus and nystagmus as a consequence to the severe visual impairment in this population.10,15 Given that all these factors have an important and complex role on visual development and visual function, and knowing that strabismus alone can impact negatively on visual development34,36, our team decided to surgically intervene in a sample of children that presented constant horizontal strabismus21.

The present study has followed these children for over 2 years and identified functional vision developmental gain. The FVDMT instrument improved or stabilized in 93.5% items in the first assessment and improved or stabilized in 73.9% of the FVDMT items in the 2-year follow-up. However, it is important to highlight that despite the functional vision improvement observed herein, the improvement still was below to what was expected for their age. As the child's chronological age advances, functional vision becomes more complex and requires greater brain capacity24,25. The assessment of children with CZS, on the other hand, is challenging because of the multiple and severe brain disorders. These neurological manifestations must be taken in consideration because they affect their overall development and consequently, their functions5.

As expected, the present study found a sustained overall developmental delay using the BSID-III instrument. Global development depends on the integration of several neural systems including those responsible for cognition, fine and gross motor skills, visual processing, and functional vision41. Through this study, we were able to understand that, although there was an improvement or stabilization of most items related to functional vision, children did not necessarily improve in other neurological domains. Thus, we hypothesize that the overall neurodevelopment of children with CZS rely not only on vision and functional vision but also combined to other neurological functions, as well as environmental stimuli received throughout life that might also compromise their global development.

The limitations in our study include a small sample and the fact that it was conducted at a single institution. Another limitation was the lack of a control group composed of children with CZS that did not undergo strabismus surgery. It is noteworthy that our cohort of children with CZS are severely affected with significant neurological manifestations and visual impairment, therefore, outcomes may be skewed toward poorer outcomes. Measuring visual acuity was challenging since most of the children with CZS present CVI, oculomotility dysfunction, and attention deficit, which may have affected the child’s response and, consequently, the examiner’s judgment of the child’s response13,37. However, the aim of our study was to present the long-term visual and developmental outcomes of strabismus surgery, and as such, reliability of visual and development outcomes was increased by using functional visual milestones and BSID-III in multiple assessments.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that strabismus surgery led to sustained ocular alignment in most children with CZS in the studied sample. Despite no visual acuity improvement was observed, the patients demonstrated improvement or stability in almost 75% of the assessed visual functional items in a 2-year follow-up period. The complexity of other comorbidities and associated conditions, such as neurological, ocular, and skeletal abnormalities, may have affected child's neurodevelopmental and visual acuity improvement. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the long-term outcomes of children with CZS that were submitted to strabismus surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children and families/caregivers who took part in this study. We thank the contributions of the multidiscipline team of the Rehabilitation Center and the Department of Research of the Altino Ventura Foundation. We also thank Dr. Daena Leal for reviewing the visual acuity data and Dr. Linda Lawrence for reviewing this manuscript.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Funding for the study was provided by grant 1R01HD093572-0 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Macnamara FN. (1954). Zika Virus: A Report on Three Cases of Human Infection during an Epidemic of Jaundice in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Tro. Med. Hyg, 48 (2), 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IML, et al. (2016). Possible Association between Zika Virus Infection and Microcephaly—Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 65(3), 59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris J, Orioli IM, Benavides-Lara A, de la Paz Barboza-Arguello M, et al. (2021). Prevalence of Microcephaly: the Latin American Network of Congenital Malformations 2010-2017. BMJ Paediatr Open, 23, 5(1), e001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Araújo TVB, Rodrigues LC, de Alencar Ximenes RA, et al. (2016). Association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Brazil, January to May, 2016: preliminary report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis, 16, 1356–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore CA, Staples JE, Dobyns WB, et al. (2017). Characterizing the pattern of anomalies in congenital Zika syndrome for pediatric clinicians. JAMA Pediatr, 171, 288–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, et al. (2016). Zika Virus Infects Human Cortical Neural Progenitors and Attenuates Their Growth. Cell Stem Cell, 18, 587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chimelli L, Melo ASO, Portari EA. (2017). The spectrum of neuropathological changes associated with congenital Zika virus infection. Acta Neuropathol, 133, 983–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aragao MFV, Van Der Linden V, Brainer-Lima AM et al. (2016). Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study. BMJ, 353, i1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henderson AD, Ventura CV, Huisman TAGM, et al. (2021). Characterization of Visual Pathway Abnormalities in Infants With Congenital Zika Syndrome Using Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Neuroophthalmol, 41(4), e598–e605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ventura CV, Maia M, Ventura BV, et al. (2016). Ophthalmological findings in infants with microcephaly and presumable intra-uterus Zika virus infection. Arq Bras Oftalmol, 79(1), 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventura CV, Maia M, Bravo-Filho V, et al. (2016). Zika virus in Brazil and macular atrophy in a child with microcephaly. The Lancet, 387(10015), 228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, et al. (2016). Ocular findings in infants with microcephaly associated with presumed Zika virus congenital infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol, 134(5), 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ventura LO, Ventura CV, Lawrence L, et al. (2017). Visual impairment in children with congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS, 21(4), 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventura CV, Zin A, Paula Freitas BD, et al. (2021). Ophthalmological Manifestations in Congenital Zika Syndrome in 469 Brazilian Children. J AAPOS, 25 (3), 158–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuler-Faccini L, Del Campo M, García-Alix A, et al. (2022). Neurodevelopment in Children Exposed to Zika in utero: Clinical and Molecular Aspects. Front Genet, 13, 758715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study, G. (2008). Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in African American and Hispanic children ages 6 to 72 months the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology, 115:1229–1236 e1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Giordano L, Ibironke J, Hawse P, et al. (2009). Prevalence of amblyopia and strabismus in white and African American children aged 6 through 71 months the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology, 116:2128–2134 e2121–2122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ventura LO, Lawrence L, Ventura CV, et al. (2017). Response to Correction of Refractive Errors and Hypoaccommodation in Children with Congenital Zika Syndrome. J AAPOS, 21 (6), 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robaei D, Rose KA, Kifley A, Cosstick M, Ip JM, & Mitchell P (2006). Factors associated with childhood strabismus: findings from a population-based study. Ophthalmology, 113(7), 1146–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemptinne C, Aerts F, Pellissier T, et al. (2020). Motor skills in children with strabismus. Journal of AAPOS, 24(2):76.e1–76.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ventura LO, Travassos S, Ventura-Filho MC, et al. (2020). Congenital Zika Syndrome: Surgical and Visual Outcomes After Surgery for Infantile Strabismus. JPOS, 57(3), 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazzi E, Signorini SG, Bova SM, et al. Spectrum of visual disorders in children with cerebral visual impairment. J Child Neurol. 2007; 22: 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. List of Official ICD-10 Updates Ratified October 2006. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyvärinen L, Walthes R, Jacob N, et al. (2017). Delayed visual development: development of vision and visual delays. Am Acad Ophthalmol. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D, Calvello G, Friedman CT. Parents and Their Infants with Visual Impairments (PAIVI). 2nd Edition Kit. 2015; American Printing House for the Blind. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiariti V, Longo E, Shoshmin A, Kozhushko L, Besstrashnova Y, Król M, Amado S. (2018). Implementation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) core sets for children and youth with cerebral palsy: global initiatives promoting optimal functioning. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(9), 1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simeonsson RJ.; Andrea Lee. (2017). The international classification of functioning, disability and health-children and youth. An Emerging Approach for Education and Care: Implementing a Worldwide Classification of Functioning and Disability. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madaschi V, Mecca TP, Macedo EC, et al. (2016). Bayley-III scales of infant and toddler development: transcultural adaptation and psychometric properties. Paidéia, 26, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ventura LO, Ventura CV, Dias NDC, et al. (2019). Visual Impairment Evaluation in 119 Children with Congenital Zika Syndrome. J AAPO, 22 (3), 218–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odding E, Roebroeck ME & Stam HJ. (2006). The epidemiology of cerebral palsy: incidence, impairments and risk factors. Disab and Rehab, 28(4), 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philip SS & Dutton GN. (2014). Identifying and characterising cerebral visual impairment in children: a review." Clin and Experim Optomet, 97(3), 196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickering JD, Simon JW, Ratliff CD, Melsopp KB, Lininger LL. Alignment success following medical rectus recessions in normal and delayed children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1995;32(4):225–227. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19950701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Binder NR, Kruglyakova J, Borchert MS. (2015). Strabismus in patients with cortical visual impairment: outcomes of surgery and observations of spontaneous resolution. J AAPOS, 19(4), e37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu G & Ranka MP. (2014). Strabismus surgery for children with developmental delay. Currt Opin in Ophthal, 25(5), 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West MR, Borchert MS & Chang MY. (2021). Ophthalmologic characteristics and outcomes of children with cortical visual impairment and cerebral palsy. J AAPOS, 25(4), 223–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buffenn AN. (2021). The impact of strabismus on psychosocial heath and quality of life: a systematic review. Surv Ophthalmol, 66(6), 1051–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michieletto P, Pensiero S, Diplotti L, Ronfani L, Giangreco M, Danieli A, Bonanni P. Strabismus surgery in Angelman syndrome: More than ocular alignment. PLoS One. 2020. Nov 13;15(11):e0242366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson LK, & Dutton GN (2000). Periventricular leukomalacia: an important cause of visual and ocular motility dysfunction in children. Survey of ophthalmology, 45(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mercuri E, Baranello G, Romeo DM, Cesarini L, Ricci D. (2007). The development of vision. Early Human Development, 83(12), 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purpura G, Tinelli F.(2020). The development of vision between nature and nurture: clinical implications from visual neuroscience. Child’s Nervous System, 36(5), 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler AC, Toth D, Ridenour T, et al. (2020). Developmental Outcomes Among Young Children With Congenital Zika Syndrome in Brazil. JAMA Netw Open, 3(5), e204096–e204096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]