Abstract

Background: Despite medical advances in Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), patients living with HIV continue to be at risk for developing HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). The optimization of non-HAART interventions, including cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT), shows promise in reversing the impact of HAND. No data exist indicating the efficacy of CRT in remediating attention skills following neuroHIV. This paper presents a meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to remediate attention skills following HIV CRT.

Methods: The database search included literature from Google Scholar, ERIC, Cochrane Library, ISI Web of Knowledge, PubMed, PsycINFO, and grey literature published between 2013 and 2022. Inclusion criteria included studies with participants living with HIV who had undergone CRT intervention to remediate attention skills following neuroHIV. Exclusion criteria included case studies, non-human studies, and literature reviews. To assess study quality, including, randomisation, allocation concealment, participant and personnel blinding, the Cochrane Collaboration ratings system was applied.

Results: A total of 14 studies met the inclusion criteria (n = 532). There were significant pre- to post-intervention between-group benefits due to CRT in the experimental group relative to control conditions for the remediation of attention skills following HIV acquisition (Hedges g = 0.251, 95% CI = 0.005 to 0.497; p < 0.05). No significant effects (p > 0.05) were demonstrated for subgroup analysis.

Conclusions: To the author's knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis that exclusively analyses the remediation of attention skills in the era of HAART and neuroHIV, where all studies included participants diagnosed with HIV. The overall meta-analysis effect indicates the efficacy of CRT in remediating attention skills in HIV and HAND. It is recommended that future cognitive rehabilitation protocols to remediate attention skills should be context and population-specific and that they be supplemented by objective biomarkers indicating the efficacy of the CRT.

Registration: Protocols.io (01/03/2023).

Keywords: HIV, HAND, Attention Rehabilitation, Neuroplasticity, meta-analysis, meta-regression

Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) continues to be a significant global pandemic with no known cure. Latest figures from UNAIDS (2021) indicate that by the end of 2021, approximately 38.4 million people were living with the virus, with 1.5 million newly reported cases in 2021 alone. Virologically, HIV is a ribonucleic acid (RNA), single-stranded retrovirus ( Poltronieri et al., 2015) that targets cells in the immune system. Through pathobiology yet to be understood, following transmission to the host, HIV permeates the blood-brain barrier (BBB), where it leads to the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages. This differentiation leads to the infection of cells in the CNS, namely microglia and astrocytes ( Filipowicz et al., 2016; Sillman et al., 2018). In breaching the BBB, HIV is thought to dysregulate the brain’s intrinsic nerve cell architecture, leading to aberrant neural transmission, including excess glutamate levels and decreased dopaminergic transmission ( Elbirt et al., 2015; Nolan & Gaskill, 2019). Markedly, HIV’s viral penetrance and persistence in the CNS is implicated in neuronal apoptosis, leading to a milieu of neurocognitive impairments associated with HIV ( Das et al., 2016; Smail & Brew, 2018).

Neurocognitive impairments resulting from HIV are well-documented and include HIV Dementia ( Hussain et al., 2022; Mattson et al., 2005), HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) ( Elbirt et al., 2015; Smail & Brew, 2018), and HIV encephalitis ( Morgello, 2018). Specific to HAND 1 , although no reliable worldwide estimates exist, the prevalence rates are estimated to range from 25% to 59% of HIV cases ( Bonnet et al., 2013; Elbirt et al., 2015; Kinai et al., 2017). According to updated criteria, HAND is diagnosed if a patient performs more than one standard deviation (SD) below his or her normative mean, on standardized neuropsychological measures, in two or more cognitive domains ( e.g., attention, speed of processing, verbal memory, executive functioning) ( Antinori et al., 2007; Brew, 2018; Chan et al., 2019; Chan & Wong, 2013; Saloner & Cysique, 2017).

Problem statement

Pharmacological interventions, namely Highly Active Antiretrovirals (HAART), have improved cognitive outcomes in HIV ( Benki-Nugent & Boivin, 2019; Jantarabenjakul et al., 2019). However, to date, their efficacy in treating or reducing the impact of HAND remains variable ( Alford & Vera, 2018; Lanman et al., 2019; Yuan & Kaul, 2019). For example, Underwood et al. (2015) found that prolonged treatment with efavirenz (a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor) (NNRTI) and raltegravir (integrase inhibitor) may play a role in HIV-associated cognitive decline and poorer cognitive function in children living with HIV. A cognate study by Hammond et al. (2019) found that children in a South African study showed no cognitive gains after receiving efavirenz. The study hypothesised that efavirenz, due to its pharmacokinetic profile (genetically slow metabolites), may be a risk factor for neurotoxicity, leading to the poor neurocognitive outcomes associated with HAND.

Correspondingly, Crowell et al. (2015), in their study involving 396 children living with HIV, found an association between early viral suppression and improved neurocognitive outcome; however, they found no association between a high CNS Penetration-Effectiveness score (CPE) 2 and neurocognitive improvement in the children. These findings are similar to those reported by Ellis et al. (2014), who found no association between high CPE and gains in neurocognition in a longitudinal study conducted among adults living with HIV. Similarly, Puthanakit et al. (2013), found no improvement in neurocognitive outcomes amongst 139 Thai and Cambodian children living with HIV after a three-year initiation of cARTs. Other studies ( Das et al., 2016; Iglesias-Ussel & Romerio, 2011; Kumar et al., 2018) indicate that when antiretrovirals (ARVs) act upon the brain HIV viral reservoir, they are indicated to significantly cause neurotoxicity, leading to further neurocognitive and psychiatric impairments ( Alford & Vera, 2018; Das et al., 2016; Lanman et al., 2019; Vázquez-Santiago et al., 2014; Wilmshurst et al., 2018).

Brain plasticity and cognitive rehabilitation

Given the pharmacological limitations associated with ARVs, including limitations in viral reservoir penetration in the brain and neurotoxicity, studies have begun investigating the efficacy of alternative non-pharmaceutical therapies, namely cognitive rehabilitation therapy (CRT) 3 , to reverse HAND. The principles of CRT are based on neuroplasticity. Neural brain plasticity posits that the human cortex is malleable and has the inherent capacity to undergo structural and functional change ( Bach-y-Rita, 2003; Wilson et al., n.d.). Within the mammalian cortex, structural and functional change is attendant to continued and repeated exposure to cognitively demanding brain training exercises, purposed to rewire and improve neuronal connectivity, increase blood supply and improve brain function ( Hebb, 1949; Luria, 1948; Merzenich, 2013). Luria (1970), particularly notes that brain plasticity and cognitive training allow for axonal and synaptic connections reintegrating. Accordingly, through dendritic outflow, synaptic connections are thought to stimulate neuronal density and cortical enrichment in near and distant neuronal networks responsible for disparate cortical functions.

Given the promise of positive neuroplasticity to harness neurocortical networks and ameliorate brain function, the extant literature has documented the efficacy of brain training exercises to reduce the risk of cognitive impairment sequent HAND. For example, data indicate improvements in cognitive domains such as executive functions ( Boivin et al., 2016; Frain & Chen, 2018), attention ( Basterfield, & Zondo, 2022; Boivin et al., 2010; Towe et al., 2017), processing speed ( Cody et al., 2020; Vance et al., 2012), and working memory ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Towe et al., 2017), following intensive brain training exercise in neuroHIV.

Despite the above early promising findings, contradictory findings have been reported. For example, Vance et al. (2012) used a computerized CRT program (InSight) to investigate processing speed in adults. Although the experimental group showed significant baseline-to-post-test improvements in speed processing, speed processing deficits are not prevalent in the post-cART era ( Heaton et al., 2011). In another study, Pope et al. (2018) found that a computerised program (Posit Science: BrainHQ) could improve abstraction and executive functions, whereas Fazeli et al. (2019), reported that the same software enhanced other cognitive domains, such as attention, working memory, and information processing in the experimental group. Moreover, some studies returned insignificant findings ( e.g., Vance et al., 2018; Fazeli et al. 2019) when comparing the effect of the cognitive rehabilitation on the experimental group, compared to the control, despite utilizing brain training programs and techniques that have proven to improve cognition in HIV.

Given contradictory findings within the literature, Vance et al. (2019), conducted a systematic review of 13 computerised cognitive rehabilitation (CCT) studies investigating the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation to reverse HAND. The review by Vance et al. (2019) found that, for the most part, CRT in HIV was associated with improved cognitive outcomes that translated to improvements in quality of life. Nonetheless, although the systematic review provides summary data on the effect of CRT on working memory, processing speed, and ageing, it does not provide effect size data for each of the reviewed cognitive domains. Most importantly, it does not provide information on the cognitive rehabilitation of attention skills, although deficits in attention are the foremost and common consequence of HIV ( Posada et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2017). Moreover, since the review did not provide effect size data, it did not provide data detailing the effect of moderator variables or subgroup meta-analytic data on HIV cognitive rehabilitation outcomes. Given these limitations, the current study aimed to conduct a meta-analysis investigating the efficacy of CRT in remediating attention skills among people living with HIV. Significantly, the study aimed to (1) provide effect size data detailing pre- and post-intervention improvement in attention due to CRT among people living with HIV. Secondly, the study sought to (2) investigate the effect of moderator variables by conducting subgroup analyses of the effect size (if significant). Lastly, the study aimed to provide clinical suggestions for implementing HIV CRT interventions in low-to medium-income countries with a high number of HIV cases.

Methods

This study was registered on Protocols.io ( dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.5jyl8jqm7g2w/v1; 01/03/2023). Although the study was not registered in PROSPERO the review protocol can be found as Extended data ( Zondo, 2023). The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines for meta-analyses ( Moher et al., 2009).

Search strategy

The units of analysis were chosen from published literature containing medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words related to: ‘HIV and attention rehabilitation’ or ‘HIV and cognitive rehabilitation’, ‘HIV and/or attention’, ‘HIV and attention remediation’, ‘HIV and executive attention remediation’. These were combined with terms related to outcome research such as: ‘effect’, ‘efficacy’ ‘evaluation’, or ‘outcome’. To identify relevant studies, journal articles, books, dissertations, and electronic databases were searched. Electronic database searches included Google Scholar (RRID:SCR_008878), ERIC (RRID:SCR_007644), Cochrane Library (RRID:SCR_013000), ISI Web of Knowledge, PubMed (RRID:SCR_004846), and PsycINFO (RRID:SCR_014799). Grey literature and unpublished papers were searched based on indices of conference proceedings and dissertation abstracts to minimise publication bias ( Higgins & Green, 2008). A complete breakdown and description of the search strategies are available as Extended data ( Zondo, 2023).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies included in the meta-analysis were included based on the PICOS criteria. The population and condition of interest were patients diagnosed with HIV, receiving cognitive rehabilitation to remediate attention. Participants in the experimental group should have undergone an intervention to remediate attention skills following neuroHIV. Studies should have included a comparison between the experimental group and at least one control group (passive control group, or active control group). Studies should also have reported outcome data in the form of pre-and post-intervention attention scores using validated neuropsychological measures of attention 4 . Lastly, studies were included if they used random and non-random control trial study designs. In addition to the PICOS criteria, studies should have reported sample sizes to enable effect size weighting ( Borenstein et al., 2021).

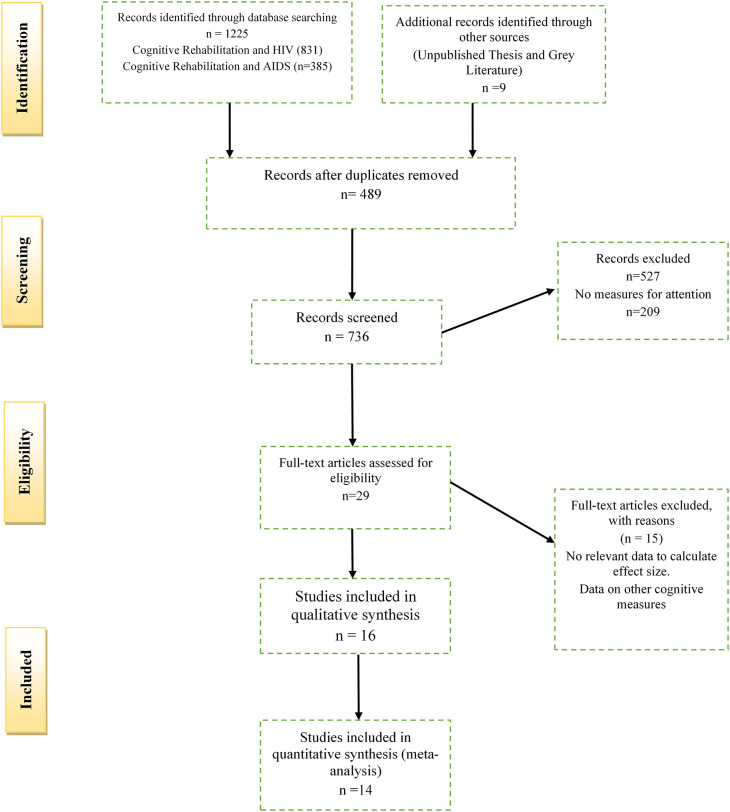

The above inclusion criteria were combined with the 27-item PRISMA checklist to produce a four-phase PRISMA flow diagram as suggested by Moher et al. (2009). The complete PICOS criteria accompanied by the PRISMA checklist can be found as Extended data ( Zondo, 2023). The PRISMA flow diagram is indicated below in Figure 1. All duplicate studies for the meta-analysis were removed using Mendeley Data (RRID:SCR_002750) Software, Version 1. The author (S.Z) and two researcher assistants (K.S and T.C), independently assessed the titles and abstracts retrieved from literature searches for relevance. After the initial assessment, the same reviewers determined the eligibility of all full-text relevant for the meta-analysis. Any disagreements (three articles) were resolved by a third research assistant (N.M) with expertise in meta-analytic research. Relevant but excluded studies from the reviewed literature are indicated in the Extended data ( Zondo, 2023).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram depicting the selection of studies for the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Data extraction was done by the author and cross-checked (by K.S. and T. C.) using an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation) (RRID:SCR_016137). The relevant summary statistics to investigate attention outcomes due to cognitive rehabilitation included individual data points linked to: (a) The number of participants in each of the groups, (b) relevant statistical data such as means, and standard deviations, for both the experimental and control groups (active or passive control) on the attention measures, pre and post the intervention ( Field & Gillett, 2010; Lee, 2018).

The extraction of attention outcomes (dependent variable) for each of the studies used in the meta-analysis are available as Extended data ( Zondo, 2023). Other key moderator data extracted from each of the studies included in the meta-analysis included data related to: (a) the duration of the cognitive training exercises (<10 sessions; 10 sessions; >10 sessions in each study; (b) the type of cognitive training received (computerised; pencil and paper, mixed); (c) the setting of the cognitive training (individualised training; group intervention); (d) the type of research design employed (random control trial vs. non-random control); (e) the socio-economic setting of the study (High vs. Low); (f) the data quality of the study (Low, Medium, High); (g) the type of sample (paediatric HIV vs. geriatric HIV); (h) the type of control group utilised (active, passive, both) and (g) whether participants were blind or aware to their condition (experimental or control). The above variables were included in the subgroup meta-analysis to investigate the influence of pertinent moderator variables on the overall effect size of the cognitive rehabilitation.

Data analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using Stata 17 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX. StataCorp, LLC) (RRID:SCR_012763) (free alternative, RStudio). The overall effect size was determined by measuring attention scores pre-and-post the CRT to investigate the effectiveness of the attention intervention. Given the heterogeneity across all studies, the random effect model was used to estimate the pooled effect ( Borenstein et al., 2009). Effect sizes were calculated based on the standardised mean difference (SMD) sizes for the individual studies, weighted according to the relevant sample size. Briefly, when using SMD, effect is calculated as the mean change in pre-intervention scores compared to post-intervention scores in the intervention group minus the mean change from pre-intervention to post-intervention scores in the control group, divided by the combined pre-intervention standard deviation scores ( Borenstein et al., 2009; Field & Gillett, 2010).

Following suggestions from Borenstein et al. (2021), the inverse variance method was used to interpolate the SMDs of each study. As suggested by Borenstein et al. (2021), since the SMD model also corrects for the use of different outcome measures ( i.e., different neuropsychological outcomes used to assess attention), it, however, fails to account for differences in the direction of the participants’ behavioural performance (neuropsychological performance) within the various outcome measures used in the meta-analysis (neuropsychological assessments). Stated differently in certain assessments, an increase in mean scores may represent a decline in disease severity, whereas, in some neuropsychological assessments, a decrease in mean scores represents a decline in disease severity ( Borenstein et al., 2009). To correct these differences, mean scores from studies in which a decrease in mean scores represents a decline in disease severity were multiplied by -1, ensuring conformity of direction for all the scales used in the meta-analysis calculation ( Borenstein et al., 2009). Based on the above recommendations, the mean scores for both the control and experimental group from the following studies Fazeli et al. (2019), Zondo and Mulder (2015) were corrected by multiplication of -1.

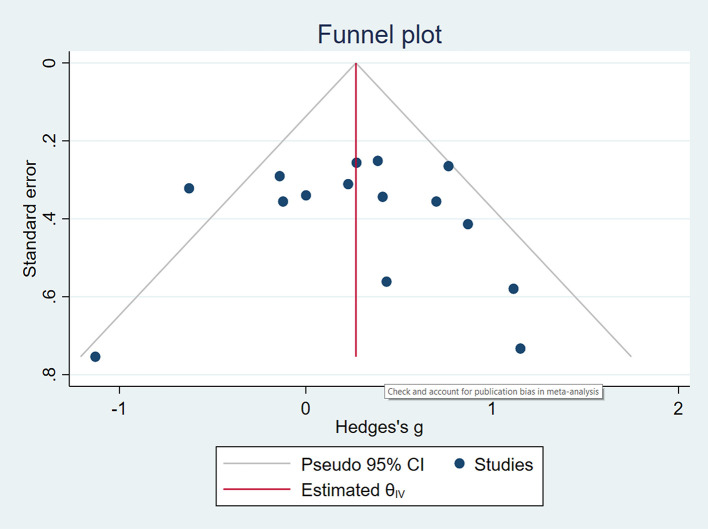

The H 2 and I 2 statistic (based on the Q statistic) was used to assess the proportional significance of heterogeneity ( Borenstein et al., 2009). The author tested for publication bias using a funnel plot, which is a type of scatterplot with treatment effect size (Cohen’s D) plotted on the x-axis, and the standard error (variance) plotted on the y-axis ( Borenstein et al., 2009). Statistical significance for all analyses was set at a threshold of p < 0.05.

Results

Search results

Since the inclusion criteria of the studies are detailed in the methods section, a PRISMA flow chart indicating the decision process and study selection is described in Figure 1. In summary, the study included a total of 1,225 records; after removing duplicates (489), 736 records were screened. A further 527 records were excluded based on title searches, abstracts, and methodological considerations ( i.e., case studies and qualitative designs). A total of 15 studies were deemed relevant but were excluded from the analysis due to reasons provided as Extended data ( Zondo, 2023). In total, 29 studies were assessed for eligibility with the final selection including 11 randomised control studies ( Basterfield, & Zondo, 2022; Boivin et al., 2010; Casaletto et al., 2016; Cody et al., 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Frain & Chen, 2018; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Livelli et al., 2015; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012) and three non-randomised studies ( Cody et al., 2015; Ezeamama et al., 2020; Zondo & Mulder, 2015).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of all studies included in the meta-analysis are detailed in Table 1. The analysis included data from South Africa ( Basterfield, & Zondo, 2022; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Zondo & Mulder, 2015), Uganda ( Boivin et al., 2010; Ezeamama et al., 2020), Italy ( Livelli et al., 2015), and the US ( Casaletto et al., 2016; Cody et al., 2015, 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Frain & Chen, 2018; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012). In total, the study comprised 532 participants (255 participants in the intervention group and 277 participants in the control group).

Table 1. Study and participant characteristics.

CRT, cognitive rehabilitation therapy; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; HAART, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; HAND, HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.

| Study | Sample | Attention remediation group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Age mean in years | Female (n) | Overall description of participants | Training received | Number of sessions b | Sessions per week | Follow up duration | Type of attention training | Control condition | |||||

| Total | CRT | Control | CRT | Control | CRT | Control | ||||||||

| Basterfield & Zondo (2022), SA | 5 | 3 | 2 | 11.27 | 11.23 | 2 (66) | 1(50) | Children a (aged 10-15 yrs.) with HIV receiving HAART. | BrainWaveR | 8 | 3 | None | Selective | Microsoft Word Exercises |

| Boivin et al. (2010), Uganda | 60 | 32 | 28 | 10.34 | 9.36 | 21(65.6) | 15(53.6) | Children (aged 6-16 yrs.) with perinatal transmission of HIV on HAART. | Captain’s Log | 10 | 2 | None | Simple | Non-Active Cognitive Training |

| Casaletto et al. (2016), USA | 90 | 30 | 30 x 2 | 50.1 | 47.8 | 3 (10) | 7 (23) | Adults (47-51 yrs.) with HIV and Substance Use Disorder and Dysexecutive Syndrome. | Goal Management & Metacognition Training | 1 | N/A | None | Divided | Paper Origami Exercises |

| Cody et al. (2015), USA | 20 | 13 | 24 | 50.22 | 52.9 | 4 (25) | (7) 29 | Adults (47-51 yrs.) with asymptomatic HIV. | PositScience | 5 | N/A | 1-2 Months | Selective& Divided | No Contact |

| Cody et al. (2020), (USA) | 33 | 17 | 16 | 58.82 | 62.12 | 7 (33.3) | 5 (31) | Adults (>55 yrs.) with and without HIV, and no Hx of brain trauma. | PositScience

Transcranial Deep Stimulation (tDCS) |

10 | 2 | N/A | Selective& Divided | Sham tDCS |

| Study | Sample | Attention remediation group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Age, Mean Years | Female, sex, % | Overall description of participants | Training received | Number of sessions | Sessions per week | Follow up duration | Type of attention training | Control condition | |||||

| Total | CRT | Control | CRT | Control | CRT | Control | ||||||||

| Ezeamama et al. (2020), Uganda | 81 | 41 | 49 | 59.7 | 60.0 | 24 (59) | 25 (50) | Elderly adults (>50 yrs.) with HIV and without other mental or health disorders. | Captain’s Log | 10 | 2 | 5 Weeks | Simple | Standard of Care (SOC) |

| Fazeli et al. (2019), USA | 33 | 17 | 16 | 56 | 55.63 | 6 (35) | 5 (31) | Adults (>50 yrs.) with HIV, and without a history of brain trauma, and/or mental health disorders. | PositScience BrainHQ | 10 | N/A | 4 Weeks | Selective & Divided | Sham tDCS |

| Frain & Chen (2018), USA | 22 | 10 | 12 | 58 | 54 | 0 (0) | 3 (25) | Adults (>50 yrs.) with HIV, on ARVs. | PositScience BrainHQ | N/A | 3 | 2 and 4 Months | Visual Attention | Nonactive Cognitive Training |

| Fraser & Cockcroft (2020), SA | 63 | 31 | 32 | 12.0 | 12.41 | 16 (52) | 16 (50) | Adolescents (aged 10-15 yrs.) diagnosed with Clad C HIV on HAART. | Jungle- Memory Computer Exercises | 32 | 4 | 6 months | Selective & Sustained | Microsoft Paint Exercises |

| Livelli et al. (2015), Italy | 32 | 16 | 16 | 47.5 | 50.0 | 5 (31) | 3 (19) | Adults (>50 yrs.) with HAND receiving care (Amedeo di Savola Hospital). | Mixed: Pencil and Paper & Computer Exercises | 36 | N/A | 6 months | Selective

Divided Sustained Divided |

Standard Care (SOC) |

| Ownby & Acevedo (2016), USA | 11 | 5 | 6 | 50.3 | 52.8 | 0 | 2 (40) | Adults (>51 yrs.) with HIV, and self-reported cognitive impairment in at least 2 cognitive domains. | GT Racing2 Game & tDCS | 6 | N/A | N/A | Simple Attention | Sham tDCS |

| Pope et al. (2018), USA | 30 | 15 | 15 | 55.3 | 53.7 | 5 (33) | 6 (40) | Adults (>50 yrs.) with HIV, and without a history of brain trauma, and/or mental health disorders. | PositScience | 10 | 4 | N/A | Divided & Selective | Sham tDCS |

| Vance et al. (2012), USA | 46 | 22 | 24 | 50.1 | 52.9 | 5 (23) | (7) 29 | Adults (47-51 yrs.) with asymptomatic HIV. | PositScience | 10 | N/A | N/A | Visual Attention | No Contact |

| Zondo & Mulder (2015), SA | 6 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | Children (11-year-old) with HIV receiving HAART. | BrainWaveR | 8 | 2 | N/A | Selective | No Contact |

The definition ‘child’, is based on age guidelines from the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child that describe the child/paediatric age as ranging from birth to adolescence (16-19 years) (UN Convention Assembly, 1989).

In most studies ( e.g., Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020), a session lasted for a period of 30-45 mins.

As indicated in Table 1, participant ages for adults ranged from a mean of 47.5 years ( Livelli et al., 2015) to 59.7 years ( Ezeamama et al., 2020) in the intervention group; and 50.0 years ( Livelli et al., 2015) to 62.12 years ( Cody et al., 2020) in the control group. Participant ages in the paediatric HIV groups ranged from a mean of 10.34 years ( Boivin et al., 2010) to 12.0 years ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020) in the intervention group and 9.36 years ( Boivin et al., 2010) to 12.41 years ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020) in the control group. The proportion of female participants ranged from 0% ( Frain & Chen, 2018) to 66% ( Boivin et al., 2010) in the intervention group and 0% ( Zondo & Mulder, 2015) to 90% ( Boivin et al., 2010) in the control group.

The ‘types’ of attention intervention implemented varied extensively and included selective attention training ( Basterfield, & Zondo, 2022), divided attention training ( Casaletto et al., 2016), selective and divided attention training ( Fazeli et al., 2019), selective, divided, and sustained attention training ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Livelli et al., 2015), visual attention ( Frain & Chen, 2018; Vance et al., 2012), and simple attention training ( Ezeamama et al., 2020; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016). Nine of the studies ( Boivin et al., 2010; Casaletto et al., 2016; Ezeamama et al., 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Frain & Chen, 2018; Livelli et al., 2015; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012) reported participant biomarker data, in the form of CD4+ T-cell count, pre-and post-the intervention. CD4+ T-cell counts in the treatment group ranged from 552 cells/μL ( Casaletto et al., 2016) to 833 cells/μL ( Fazeli et al., 2019). None of the studies reported biomarker data in the form of neuroimaging data ( i.e., MRI, EEG, fNIRS) detailing the effects of the intervention from baseline to post-intervention changes.

The total number of rehabilitation sessions ranged from 1 ( Casaletto et al., 2016) to 36 sessions ( Livelli et al., 2015). There was much variability within the studies regarding the duration of each rehabilitation session, with some sessions, ranging from 10-15 minutes per session ( Casaletto et al., 2016) to others ranging from 30-45 minutes per session ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020). Training frequency within studies ranged from two sessions per week ( Boivin et al., 2010) to four sessions per week ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Pope et al., 2018). For most studies, the control conditions were divided into one of two control types: either active controls (six studies: Basterfield & Zondo, 2022; Casaletto et al., 2016; Cody et al., 2020; Ezeamama et al., 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Livelli et al., 2015), or passive controls (five studies: Boivin et al., 2010; Cody et al., 2015; Frain & Chen, 2018; Vance et al., 2012; Zondo & Mulder, 2015). None of the reviewed studies included both active and passive controls, to assess the impact of the active ingredient (cognitive rehabilitation), compared to the influence of a sham activity (active control) and/or passive interaction (passive control).

Overall, 10 of the studies implemented computerised cognitive rehabilitation (CCT) protocols ( Boivin et al., 2010; Cody et al., 2015, 2020; Ezeamama et al., 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Frain & Chen, 2018; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012, 2018); two utilised pencil and paper protocols ( Basterfield & Zondo, 2022; Zondo & Mulder, 2015), whereas one study employed a mixture of computer and paper-pencil protocols ( Livelli et al., 2015), whilst another used a mixture of Goal Management and individualised metacognition training ( Casaletto et al., 2016). Of the 10 studies that implemented computerised CRT, two ( Cody et al., 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019) coupled computerised training with transcranial deep brain stimulation (tDCS). Moreover, of the studies that utilised computerised interventions, six used the PositScience-BrainHQ system ( Cody et al., 2015, 2020; Fazeli et al., 2019; Frain & Chen, 2018; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012), whereas two employed the Captain’s Log ( Boivin et al., 2010; Ezeamama et al., 2020), which trains multiple cognitive domains including working memory and executive skills, and one made use of Jungle-Memory ( Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020), which trains working memory.

Meta-analysis of attention

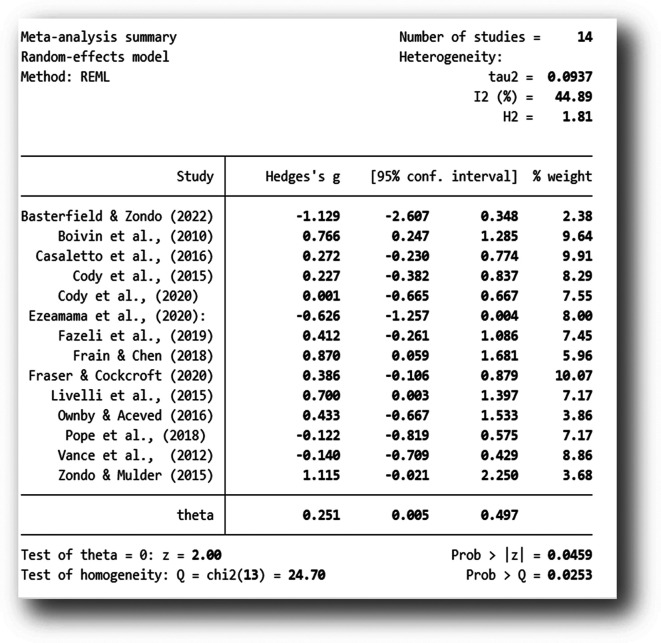

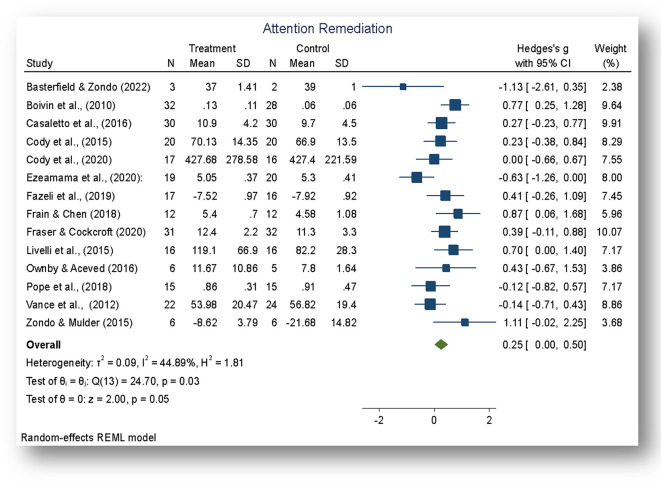

The analysis was carried out using the standardized mean difference as the outcome effect measure. As indicated in Figure 2, a random-effects model was fitted to the data. The amount of heterogeneity (tau 2) was estimated using the restricted maximum-likelihood estimator ( Viechtbauer, 2010). In addition to the estimate of tau 2, the Q-test for heterogeneity and the I 2 statistic was conducted on a total of 14 studies included in the analysis. The observed standardized mean differences ranged from -1.129 to 1.115, with the majority of estimates being positive (71%). The estimated average standardized mean difference based on the random-effects model was Hedges, g = 0.251 (95% CI: 0.005 to 0.4977).

Figure 2. Mean difference.

Note: The overall standardized mean difference was estimated using the restricted maximum-likelihood estimate (REML).

The average outcome for attention rehabilitation differed significantly from zero (z = 2.00, p = 0.045). According to the Q-test, the true outcome of the effect size appears to be heterogeneous (Q (13) = 24.70, p = 0.025, tau 2 = 0.097, I 2 = 44.89%). A 95% prediction interval for the true outcomes of the intervention ranged from - 0.3901 to 0.8579. Although the average outcome for the rehabilitation was estimated to be positive (Hedges g = 0.251, p = 0.045), the data indicate that in some studies the true outcome of the rehabilitation may in fact be negative. Further examination of the studentized residuals revealed that none of the studies had a value larger than ± 2.9137. Hence, there was no indication of outliers in the context of this model. As further indicated by the Forest Plot ( Figure 3), there was greater variability in the 95% CIs in studies with smaller sample sizes and larger weights in studies with post-intervention follow-ups and larger sample sizes.

Figure 3. Forest plot.

Note: The overall effect of the cognitive rehabilitation to remediate attention skills following neuroHIV was significant, z = 2.00, p < 0.05.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses are presented in Table 2. These were conducted to investigate the effect of key moderator variables, namely (a) the duration of the intervention (<10 sessions, 10 sessions, >10 sessions), (b) the type of rehabilitation (computerized, pencil and paper, mixed), (c) the setting of the rehabilitation (individualized or group), (d) the type of research design employed (randomized, non-randomised), (e) data quality rating (Low median, high), (f) the population of the study (paediatric HIV or geriatric HIV), (g) the type of control group in the study (active control, passive control), and (h) the blinding of subjects (aware or blind). No significant subgroup differences were found on any of the moderator variables. Further meta-regression analysis could not be conducted on the data, despite the significant outcomes of the cognitive rehabilitation (Hedges g = 0.25, p < 0.05).

Table 2. Subgroup analysis.

HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

| Table moderator effects (Post test) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure | Criteria | Subgroup (study) | n | Hedges’ g (95% CI) ns | Test of subgroup differences a |

| Remediation of Attention | Duration | ≤10 session | 6 | 0.47 (0.15–0.78) | Q=2.43, df=2 (p=0.31) |

| 10 Sessions | 6 | 0.06 (-0.34–0.47) | |||

| ≥10 Session | 3 | 0.23 (-0.53–0.99) | |||

| Type of Rehabilitation | Computerised | 12 | 0.24 (-0.01–0.49) | Q=1.52, df=2, (p=0.46) | |

| Pencil and Paper | 2 | 0.04 (-2.15–2.24) | |||

| Mixed | 1 | 0.27 (0.03–1.40) | |||

| Setting | Individualised | 5 | 0.38 (-0.20–0.96) | Q=0.17, df=1, (p=0.68) | |

| Group Rehabilitation | 10 | 0.25 (-0.04–0.53) | |||

| Research Design | Randomization | 12 | 0.33 (0.10–0.56) | Q=0.14, df=1, (p=0.71) | |

| None Randomized | 3 | 0.15 (-0.77–1.07) | |||

| Socio Economic Setting | High | 10 | 0.26 (0.05–0.48) | Q=0.06, df=1, (p=0.81) | |

| Low | 5 | 0.17 (-0.55–0.89) | |||

| Data Quality | Low | 4 | 0.37 (-0.5–1.24) | Q=0.73, df=2, (p=0.68) | |

| Medium | 4 | 0.07 (0.59–0.73) | |||

| High | 7 | 0.37 (0.15–0.60) | |||

| Population | Paediatric | 4 | 0.48 (-0.04–1.00) | Q=0.94, df=1, (p=0.33) | |

| Geriatric HIV | 11 | 0.19 (-0.07–0.46) | |||

| Type of Control | Active | 8 | 0.11 (-0.22–0.44) | Q=2.15, df=2, (p=0.34) | |

| Passive | 4 | 0.51 (-0.02–1.05) | |||

| No control | 3 | 0.43 (-0.06–0.91) | |||

| Blinding | Aware | 11 | 0.17 (-0.13–0.46) | Q=3.27, df=2, (p=0.19) | |

| Blind | 3 | 0.57 (0.10–1.04) | |||

ns: All the subgroup analysis were not significant at the 0.05 level of significance.

Heterogeneity measures for the each of the group analysis.

Study quality and risk of bias

Study quality assessment ratings were conducted on all studies based on criteria established by the Cochrane Collaboration ( Cumpston et al., 2019; Higgins & Green, 2008). The criteria for quality assessment were as follows: (1) adequate randomization concealment of participants to either the treatment or control group (by the Primary Investigator (s); (2) Blinding of participants to either the treatment or control condition(s) 5 ; (3) Baseline comparability, detailing whether the experimental and control group(s) were comparable on all outcome measures from baseline to post-intervention; (4) Power analysis: Did the study have adequate power and/or at least 15 participants per group for comparative analysis (experimental vs. control)? (5) Completeness of follow-up data: Was there adequate follow-up of at least three months post the intervention, with clear attrition analysis of data? (6) Handling of missing data: Were multiple imputation analysis and/or maximum likelihood analysis (or other advanced statistical techniques) applied to account for missing data and high attrition rates? Each of the above criteria was rated as 0 (the study does not meet criterion) or 1 (the study meets criterion). In summary, all studies were rated as Low (score 1 or 2), Medium (score 3 or 4), and High (Score 5 or 6) following suggested guidelines by Cochrane collaboration.

Based on the above criteria, five studies ( Boivin et al., 2010; Casaletto et al., 2016; Fazeli et al., 2019; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020; Livelli et al., 2015) had high-quality evidence. Six studies ( Cody et al., 2020; Ezeamama et al., 2020; Frain & Chen, 2018; Ownby & Acevedo, 2016; Pope et al., 2018; Vance et al., 2012) had moderate-quality evidence, and three studies ( Basterfield & Zondo, 2022; Cody et al., 2015; Zondo & Mulder, 2015) had low-quality evidence. Summary data for the quality assessment of each study are available as Extended Data ( Zondo, 2023). The studies with low-quality ratings primarily presented with small sample sizes and had no follow-ups of at least three months post-intervention and presented large 95% CIs ( e.g., Basterfield & Zondo, 2022; Zondo & Mulder, 2015). Expectedly, the studies with high-quality ratings implemented randomisation, including blinding research participants to group allocation, and had adequate follow-up assessments of at least three months post-intervention. Further indication for study quality and publication bias based on Cook's distances indicated that one study ( Ezeamama et al., 2020) could be overly influential on the meta-analysis effect. Nonetheless, in terms of publication bias, neither the rank correlation nor the regression test indicated any funnel plot asymmetry (p = 0.6265 and p = 0.3459, respectively), but one study was identified with publication bias as indicated in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Publication bias.

Note: According to the funnel plot, only one study could indicate publication bias.

Discussion

Main findings

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to specifically investigate the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapy as it pertains to brain training to remediate attention in neuroHIV. The nascent brain plasticity literature indicates intrinsic functional connectivity, particularly within the frontoparietal brain network, following attention and working memory cognitive rehabilitation training ( Astle et al., 2015; Marek & Dosenbach, 2022; Spreng et al., 2010, 2013). Based on the scalability of attention and working memory cognitive training, the current meta-analysis found a small but significant effect (Hedges g = 0.25, p < 0.05) for the cognitive rehabilitation of attention following HIV acquisition, pre- and post-the rehabilitation.

Findings from this meta-analysis are consistent with previous studies indicating the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation to train and remediate attention skills in patients with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) ( Bikic et al., 2018; Wexler et al., 2021), autism ( Spaniol et al., 2018), as well as children ( Astle et al., 2015; Schrieff-Elson et al., 2017), and adults ( Rosenbaum et al., 2018; Spreng et al., 2010) without ADHD. Nonetheless, despite the significant findings indicated in the overall meta-analysis regarding the efficacy of attention remediation in HIV, insignificant effects were noted on key sub-group moderator effects contrary to expectation.

Noteworthy research ( e.g., Azouvi, 2015; Shawn Green et al., 2019; Shoulson et al., 2012; Simons et al., 2016) indicate that multiple moderator effects, including methodological standards, such as the type(s) of the control group employed, randomization and blinding of subjects, and other contextual factors (the social environment of the rehabilitation), including the setting of intervention (group vs. individual rehabilitation) ( das Nair et al., 2016; Lincoln et al., 2020), influence cognitive rehabilitation outcomes in brain training protocols.

Within the current meta-analysis, presumably, the null effect observed at the subgroup level may be a result of (a) the limited number of studies and the small number of participants in some of the studies, which might have resulted in insignificant findings being noted at the subgroup level. Secondary to the above, given the variegated nature of ‘attention types’ remediated in the various studies ( i.e., sustained, selective, divided, and simple attention) may have led to a lack of uniformity in the analysis, despite controlling for, and applying the standardised mean difference (SMD) as suggested in the meta-analysis literature ( Borenstein et al., 2009).

Study limitations

There continues to be a dearth of research investigating the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation therapy in neuroHIV, and as such, there were limitations on the number of studies that could be included in the analysis. It is thus possible that the strict inclusion criteria (data points reporting ‘attention’ rehabilitation), permitted a weak interpretation of the treatment effect of the cognitive rehabilitation in the current study. The above observation is particularly significant, given that most studies investigating cognitive rehabilitation in the current era of neuroHIV have tended to focus on re-establishing cognitive functions related to ‘executive functions’, ‘working memory’, ‘processing speed’, and ‘aging’ ( Vance et al., 2019). As such, in some studies ( e.g., Ezeamama et al., 2020; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020), the cognitive rehabilitation of attention was a secondary consideration to the study's main objectives ( e.g., to remediate executive functions’ or working memory in neuroHIV).

Moreover, considering the somewhat limited evidence base for the cognitive rehabilitation of attention in neuroHIV, the current study included data from both paediatric and geriatric HIV populations. Resultantly, the age-heterogeneous nature of participants may have affected the results as indicated by high 95% confidence intervals of some paediatric studies ( e.g., Basterfield & Zondo, 2022). To this end, although research indicates that younger brains have a greater susceptibility to cognitive training compared to adult brains ( Luria, 1970), conducting a meta-analysis on a composite ‘group’ (paediatric and geriatric) at different levels of brain plasticity may have resulted in different magnitudes of observed effects within the analysis. Additionally, as noted within the brain science literature ( e.g., Boot et al., 2013; Simons et al., 2016), there continues to be a preponderance of cognitive rehabilitation studies to compare the effects of the cognitive intervention to passive, inactive controls. As noted by Boot et al. (2013), although this approach is expedient, it limits the vigorous interpretation of the ‘active ingredient’ within the rehabilitation and fails to control for the placebo effect that may be present within the intervention group. Significantly, the inclusion of ‘active control groups’, in brain research serves the dual purpose of mitigating the placebo effect and subsequently aids in matching perceived expectations of the cognitive rehabilitation within the treatment group. Unfortunately, none of the studies included in the meta-analysis had active control groups in order to match ‘the active ingredient’ within the intervention group in order to establish causal inference and treatment potency resulting from the intervention, resulting in a major limitation in the current meta-analysis.

Conclusions

Based on the current body of literature, coupled with findings from the current meta-analysis, there appears to be reasonable evidence to suggest the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation to remediate attention dysfunction in neuroHIV. Nonetheless, more studies are required to confirm these nascent findings, especially in contexts such as Sub-Saharan Africa, where the high incidence of HIV/AIDS continues to be a significant risk factor for HAND. Following a review of the HIV literature, the suggestions below should be considered when designing cognitive rehabilitation protocols in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and other low-to medium-income countries with a high number of HIV cases.

Clinical implications and recommendations for future research

Although the reviewed literature indicates that random control trial studies incorporating individualized interventions coupled with intensive intervention protocols ( i.e., 30 sessions of 30-45 minutes per session) ( e.g., Frain & Chen, 2018; Fraser & Cockcroft, 2020) generate larger effect sizes, the nature of brain training intervention research tends to be taxing, time-consuming, and resource heavy, and tends to be associated with high attrition rates ( Ballieux et al., 2016; Salkind, 2015; Schrieff-Elson et al., 2017).

It is thus suggested that future studies could benefit from adopting the Single Case Experimental Designs (SCED) to study the efficacy of CRT as it pertains to neuroHIV in SSA. The benefits of the SCED approach include in-depth rehabilitation sessions (30–45 min) with a limited number of participants (6-8) for prolonged periods of intervention. Their adoption could help mitigate high attrition rates often observed with paediatric intervention research, further improving the internal validity of neuroHIV rehabilitation studies.

Closely linked to the above, due to the limited number of participants required in SCEDs, the adoption of SCEDs could help address research design limitations within the rehabilitation literature by enabling the incorporation of both active and passive control groups in the same analysis in so doing, enabling the evaluation of the ‘active ingredient’ within the treatment arm ( Evans et al., 2014; Krasny-Pacini & Evans, 2018). Additionally, due to SCED’s individualised and meta-cognitive nature, these designs have the added benefit of incorporating shorter intervention sessions (15 minutes), interspaced with longer sessions (30-45 mins), thereby allowing for regular follow-up of shorter periods (two weeks), juxtaposed with longer follow-ups (four to eight weeks) ( Evans et al., 2014; Krasny-Pacini & Evans, 2018; Manolov & Moeyaert, 2016) to evaluate the efficacy of neuro-rehabilitation protocols.

The reviewed literature further indicates that a limited number of studies report biological marker data, such as patient viral loads, before and after cognitive rehabilitation intervention. To this end, previous studies ( e.g., Benki-Nugent & Boivin, 2019) have found that (a) people living with HIV with CD4+ T-cell counts lower than 500 cells/μL are more likely to indicate HAND. Conversely, data suggests that (b) participants with lower viral loads and higher CD4+ T-cell counts may experience significant benefits from cognitive rehabilitation therapy ( Brahmbhatt et al., 2017). It is therefore recommended that future studies conducting cognitive rehabilitation in the era of neuroHIV, report objective bio-marker data, such as viral load data, to complement neuropsychological measures indicating changes due to the cognitive rehabilitation. In line with the above observation, it is recommended that cognitive rehabilitation studies further supplement post-rehabilitation findings with objective brain imaging techniques such as functional near-infrared spectrometry (fNIRS), EEGs or other affordable neuroimaging markers to ascertain the efficacy of brain training protocols.

Lastly, several of the reviewed studies highlight the evolving nature of HIV/AIDS, especially the fact that the neuropsychological and neurobiological sequelae of HIV differ from population to population ( Brahmbhatt et al., 2017; Brew & Garber, 2018). Consequently, it is recommended that cognitive interventions implement context-specific population norms, paired with specific cognitive rehabilitation protocols, supplemented with specific objective biomarker evaluations ( e.g., fNIRS or CD4 viral load data). These context-specific norms could form the blueprint for cognitive rehabilitation studies regarding expected trajectories or outcomes related to the implementation of cognitive rehabilitation protocols within the specific context of interest, for example, in SSA or other low to middle-income settings with a heavy burden of neuroHIV.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the assistance of three research assistants (Ms. Kate Solomons, Ms. Tatenda Chivuku, and Ms Nike Mes) in cross-checking all studies included in the meta-analysis. All mentioned individuals have given permission to be named in the publication.

Funding Statement

This study is supported by funding from the South African National Research Foundation, Thuthuka Grant (TTK200408511634).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

Footnotes

Within the extant literature, the terms ‘HAND’ and ‘neuroHIV’ are used concurrently to indicate cognitive impairment following HIV ( Saloner & Cysique, 2017).

CPE ranks all ARVs on four categories (a) physicochemical properties, (b) concentrations achieved in the CSF, (c) efficacy based on CSF virologic suppression, and (d) neurocognitive improvement ( Letendre et al., 2008).

Within the extant literature, the terms ‘cognitive rehabilitation therapy’, ‘cognitive-training intervention’, and ‘brain training’, are used interchangeably ( Shawn Green et al., 2019; Simons et al., 2016), and this sequence will be equally applied in the manuscript.

Valid measures of attention were cross checked and validated based on ( Lezak et al., 2004; Strauss et al., 2006).

Following personal correspondence with multiple authors, the blinding of assessors to the experimental condition was not possible in most cases due to (a) resource constrains, (b) limited time frames to conduct research, and (c) the pilot nature of most studies in the field.

Data availability

Underlying data

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Extended data

Figshare: The cognitive remediation of attention in HIV Associated Cognitive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22196833 ( Zondo, 2023).

This project contains the following extended data:

-

•

Study Protocol.doc

-

•

Prisma Flow Diagram.pdf

-

•

Study Prisma Checklist.docx

-

•

Supplementary Materials.docx (Full Search Strategy, Relevant but Excluded Studies, Attention Outcome Measures, Study Quality Assessment)

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

References

- Alford K, Vera JH: Cognitive Impairment in people living with HIV in the ART era: A Review. Br. Med. Bull. 2018;127(1):55–68. 10.1093/bmb/ldy019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. : Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assembly UNG: Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations, Treaty Series. 1989;1577(3):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Astle DE, Barnes JJ, Baker K, et al. : Cognitive Training Enhances Intrinsic Brain Connectivity in Childhood. J. Neurosci. 2015;35(16):6277–6283. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4517-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azouvi P: Evidence-based in cognitive rehabilitation. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015;58:e143–e143. 10.1016/j.rehab.2015.07.340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach-y-Rita P: Theoretical basis for brain plasticity after a TBI. Brain Inj. 2003;17(8):643–651. 10.1080/0269905031000107133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballieux H, Wass SV, Tomalski P, et al. : Applying gaze-contingent training within community settings to infants from diverse SES backgrounds. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016;43:8–17. 10.1016/j.appdev.2015.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basterfield C, Zondo S: A Feasibility Study Exploring the Efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation Therapy for Paediatric HIV in rural south Africa: A Focus on Sustained Attention. Acta Neuropsychologica. 2022;20(3):315–329. 10.5604/01.3001.0016.0115 Reference Source [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benki-Nugent S, Boivin MJ: Neurocognitive Complications of Pediatric HIV Infections. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer;2019;1–28. 10.1007/7854_2019_102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bikic A, Leckman JF, Christensen TØ, et al. : Attention and executive functions computer training for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): results from a randomized, controlled trial. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2018;27(12):1563–1574. 10.1007/s00787-018-1151-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ, Busman RA, Parikh SM, et al. : A pilot study of the neuropsychological benefits of computerized cognitive rehabilitation in Ugandan children with HIV. Neuropsychology. 2010;24(5):667–673. 10.1037/a0019312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin MJ, Nakasujja N, Sikorskii A, et al. : A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate if Computerized Cognitive Rehabilitation Improves Neurocognition in Ugandan Children with HIV. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2016;32(8):743–755. 10.1089/AID.2016.0026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet F, Amieva H, Marquant F, et al. : Cognitive disorders in HIV-infected patients: are they HIV-related? AIDS (London, England). 2013;27(3):391–400. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835b1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot WR, Simons DJ, Stothart C, et al. : The Pervasive Problem With Placebos in Psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013;8(4):445–454. 10.1177/1745691613491271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. : Meta-regression. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. 2009; pp.187–203. 10.1002/9780470743386.ch20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. : Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons;2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmbhatt H, Boivin M, Ssempijja V, et al. : Impact of HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy on Neurocognitive Outcomes Among School-Aged Children. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2017;75(1):1–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew BJ: Introduction to HIV infection and HIV neurology. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 1st ed.Vol.152. Elsevier B.V;2018. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brew BJ, Garber JY: Neurologic sequelae of primary HIV infection. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 1st ed.Vol.152. Elsevier B.V;2018. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaletto KB, Moore DJ, Woods SP, et al. : Abbreviated Goal Management Training Shows Preliminary Evidence as a Neurorehabilitation Tool for HIV-associated Neurocognitive Disorders among Substance Users. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2016;30(1):107–130. 10.1080/13854046.2015.1129437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LG, Ho MJ, Lin YC, et al. : Development of a neurocognitive test battery for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND) screening: suggested solutions for resource-limited clinical settings. AIDS Res. Ther. 2019;16(1):9. 10.1186/s12981-019-0224-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LG, Wong CS: HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders--An issue of Growing Importance. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2013;42(10):527–534. 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V42N10p527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody SL, Fazeli PL, Crowe M, et al. : Effects of speed of processing training and transcranial direct current stimulation on global sleep quality and speed of processing in older adults with and without HIV: A pilot study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult. 2020;27(3):267–278. 10.1080/23279095.2018.1534736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cody SL, Fazeli P, Vance DE: Feasibility of a home-based speed of processing training program in middle-aged and older adults with HIV. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2015;47(4):247–254. 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell CS, Huo Y, Tassiopoulos K, et al. : Early viral suppression improves neurocognitive outcomes in HIV-infected children. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(3):295–304. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. : Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;10(10.1002):14651858. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das MK, Sarma A, Chakraborty T: Nano-ART and NeuroAIDS. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016;6(5):452–472. 10.1007/s13346-016-0293-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair R, Kontou E, Smale K, et al. : Comparing individual and group intervention for psychological adjustment in people with multiple sclerosis: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2016;30(12):1156–1164. 10.1177/0269215515616446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbirt D, Mahlab-Guri K, Bezalel-Rosenberg S, et al. : HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2015;17(1):54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Letendre S, Vaida F, et al. : Randomized trial of central nervous system-targeted antiretrovirals for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58(7):1015–1022. 10.1093/cid/cit921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JJ, Gast DL, Perdices M, et al. : Single case experimental designs: Introduction to a special issue of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2014;24(3/4):305–314. 10.1080/09602011.2014.903198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezeamama AE, Sikorskii A, Sankar PR, et al. : Computerized Cognitive Rehabilitation Training for Ugandan Seniors Living with HIV: A Validation Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(7). 10.3390/jcm9072137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli PL, Woods AJ, Pope CN, et al. : Effect of transcranial direct current stimulation combined with cognitive training on cognitive functioning in older adults with HIV: A pilot study. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult. 2019;26(1):36–47. 10.1080/23279095.2017.1357037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AP, Gillett R: How to do a meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2010;63(3):665–694. 10.1348/000711010X502733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz AR, McGary CM, Holder GE, et al. : Proliferation of Perivascular Macrophages Contributes to the Development of Encephalitic Lesions in HIV-Infected Humans and in SIV-Infected Macaques. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32900. 10.1038/srep32900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frain JA, Chen L: Examining the effectiveness of a cognitive intervention to improve cognitive function in a population of older adults living with HIV: a pilot study. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2018;5(1):19–28. 10.1177/2049936117736456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, Cockcroft K: Working with memory: Computerized, adaptive working memory training for adolescents living with HIV. Child Neuropsychol. 2020;26(5):612–634. 10.1080/09297049.2019.1676407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond CK, Eley B, Ing N, et al. : Neuropsychiatric and Neurocognitive Manifestations in HIV-Infected Children Treated With Efavirenz in South Africa—A Retrospective Case Series. Front. Neurol. 2019;10:742. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. : HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J. Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebb DO: The organization of behavior: A neuropsychological theory. Wiley;1949. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2008.

- Hussain T, Corraes A, Walizada K, et al. : HIV Dementia: A Bibliometric Analysis and Brief Review of the Top 100 Cited Articles. Cureus. 2022;14(5):e25148. 10.7759/cureus.25148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Ussel MD, Romerio F: HIV reservoirs: the new frontier. AIDS Rev. 2011;13(1):13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantarabenjakul W, Chonchaiya W, Puthanakit T, et al. : Low risk of neurodevelopmental impairment among perinatally acquired HIV-infected preschool children who received early antiretroviral treatment in Thailand. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019;22(4):e25278. 10.1002/jia2.25278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinai E, Komatsu K, Sakamoto M, et al. : Association of age and time of disease with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: a Japanese nationwide multicenter study. J. Neurovirol. 2017;23(6):864–874. 10.1007/s13365-017-0580-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasny-Pacini A, Evans J: Single-case experimental designs to assess intervention effectiveness in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018;61(3):164–179. 10.1016/j.rehab.2017.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Maurya VK, Dandu HR, et al. : Global Perspective of Novel Therapeutic Strategies for the Management of NeuroAIDS. Biomol. Concepts. 2018;9(1):33–42. 10.1515/bmc-2018-0005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanman T, Letendre S, Ma Q, et al. : CNS Neurotoxicity of Antiretrovirals. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2019;16(1):130–143. 10.1007/s11481-019-09886-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH: An overview of meta-analysis for clinicians. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018;33(2):277–283. 10.3904/kjim.2016.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letendre S, Marquie-Beck J, Capparelli E, et al. : Validation of the CNS Penetration-Effectiveness Rank for Quantifying Antiretroviral Penetration Into the Central Nervous System. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65(1):65–70. 10.1001/archneurol.2007.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW, et al. : Neuropsychological assessment. USA: Oxford University Press;2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln NB, Bradshaw LE, Constantinescu CS, et al. : Group cognitive rehabilitation to reduce the psychological impact of multiple sclerosis on quality of life: the CRAMMS RCT. Health Technol. Assess. (Winch. Eng.). 2020;24(4):1–182. 10.3310/hta24040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livelli A, Orofino GC, Calcagno A, et al. : Evaluation of a Cognitive Rehabilitation Protocol in HIV Patients with Associated Neurocognitive Disorders: Efficacy and Stability Over Time. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2015;9:306. 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR: Restoration of Brain Function After Brain Injury. New York: Macmillan;1948. [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR: The functional organization of the brain. Sci. Am. 1970;222(3):66–78. 10.1038/scientificamerican0370-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolov R, Moeyaert M: How Can Single-Case Data Be Analyzed? Software Resources, Tutorial, and Reflections on Analysis. Behav. Modif. 2016;41(2):179–228. 10.1177/0145445516664307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek S, Dosenbach NUF: The frontoparietal network: function, electrophysiology, and importance of individual precision mapping. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Haughey NJ, Nath A: Cell death in HIV dementia. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 1):893–904. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich MM: Soft-wired: How the new science of brain plasticity can change your life. Parnassus:2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgello S: HIV neuropathology. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;152:3–19. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00002-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan R, Gaskill PJ: The role of catecholamines in HIV neuropathogenesis. Brain Res. 2019;1702:54–73. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ownby RL, Acevedo A: A pilot study of cognitive training with and without transcranial direct current stimulation to improve cognition in older persons with HIV-related cognitive impairment. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016;12:2745–2754. 10.2147/NDT.S120282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltronieri P, Sun B, Mallardo M: RNA Viruses: RNA Roles in Pathogenesis, Coreplication and Viral Load. Curr. Genomics. 2015;16(5):327–335. 10.2174/1389202916666150707160613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope CN, Stavrinos D, Vance DE, et al. : A pilot investigation on the effects of combination transcranial direct current stimulation and speed of processing cognitive remediation therapy on simulated driving behavior in older adults with HIV. Transport. Res. F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2018;58:1061–1073. 10.1016/j.trf.2018.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada C, Moore DJ, Deutsch R, et al. : Sustained attention deficits among HIV-positive individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2012;24(1):61–70. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11010028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthanakit T, Ananworanich J, Vonthanak S, et al. : Cognitive function and neurodevelopmental outcomes in HIV-infected Children older than 1 year of age randomized to early versus deferred antiretroviral therapy: the PREDICT neurodevelopmental study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013;32(5):501–508. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31827fb19d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum D, Maier MJ, Hudak J, et al. : Neurophysiological correlates of the attention training technique: A component study. NeuroImage. Clinical. 2018;19:1018–1024. 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salkind N: Encyclopedia of Research Design. Dictionary of Statistics & Methodology. 2015. 10.4135/9781412983907.n1240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saloner R, Cysique LA: HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders: A Global Perspective. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017;23(9–10):860–869. 10.1017/S1355617717001102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrieff-Elson LE, Ockhuizen JRH, During G, et al. : Attention-training with children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds in Cape Town. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health. 2017;29(2):147–167. 10.2989/17280583.2017.1372285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawn Green C, Bavelier D, Kramer AF, et al. : Improving Methodological Standards in Behavioral Interventions for Cognitive Enhancement. J. Cogn. Enhanc. 2019;3(1):2–29. 10.1007/s41465-018-0115-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shoulson I, Wilhelm EE, Koehler R: Cognitive rehabilitation therapy for traumatic brain injury: evaluating the evidence. National Academies Press;2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sillman B, Woldstad C, Mcmillan J, et al. : Neuropathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;152:21–40. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00003-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons DJ, Boot WR, Charness N, et al. : Do “Brain-Training” Programs Work? Psychol. Sci. Public Interest. 2016;17(3):103–186. 10.1177/1529100616661983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smail RC, Brew BJ: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 1st ed.Vol.152. Elsevier B.V;2018. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaniol MM, Shalev L, Kossyvaki L, et al. : Attention Training in Autism as a Potential Approach to Improving Academic Performance: A School-Based Pilot Study. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018;48(2):592–610. 10.1007/s10803-017-3371-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Sepulcre J, Turner GR, et al. : Intrinsic architecture underlying the relations among the default, dorsal attention, and frontoparietal control networks of the human brain. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2013;25(1):74–86. 10.1162/jocn_a_00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spreng RN, Stevens WD, Chamberlain JP, et al. : Default network activity, coupled with the frontoparietal control network, supports goal-directed cognition. NeuroImage. 2010;53(1):303–317. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O: A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. American Chemical Society;2006. [Google Scholar]

- Towe SL, Patel P, Meade CS: The Acceptability and Potential Utility of Cognitive Training to Improve Working Memory in Persons Living With HIV: A Preliminary Randomized Trial. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2017;28(4):633–643. 10.1016/j.jana.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS: World HIV/AIDS Statistics. 2021. Reference Source

- Underwood J, Robertson KR, Winston A: Could antiretroviral neurotoxicity play a role in the pathogenesis of cognitive impairment in treated HIV disease? AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(3):253–261. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Cheatwood J, et al. : Computerized Cognitive Training for the Neurocognitive Complications of HIV Infection. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2019;30(1):51–72. 10.1097/JNC.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Fazeli PL, Ross LA, et al. : Speed of processing training with middle-age and older adults with HIV: a pilot study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(6):500–510. 10.1016/j.jana.2012.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Jensen M, Tende F, et al. : Individualized-Targeted Computerized Cognitive Training to Treat HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder: An Interim Descriptive Analysis. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(4):604–611. 10.1016/j.jana.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Santiago FJ, Noel RJ, Jr, Porter JT, et al. : Glutamate metabolism and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J. Neurovirol. 2014;20(4):315–331. 10.1007/s13365-014-0258-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W: Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010;36(3 SE-Articles):1–48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhu S, et al. : Selective impairments of alerting and executive control in HIV-infected patients: evidence from attention network test. Behav. Brain Funct. 2017;13(1):11. 10.1186/s12993-017-0129-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wexler BE, Vitulano LA, Moore C, et al. : An integrated program of computer-presented and physical cognitive training exercises for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Med. 2021;51(9):1524–1535. 10.1017/S0033291720000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmshurst JM, Hammond CK, Donald K, et al. : NeuroAIDS in children. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 1st ed.Vol.152. Elsevier B.V;2018. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63849-6.00008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BA, Society BP, Society IN, et al. : Neuropsychological Rehabilitation Handbook. n.d..

- Yuan NY, Kaul M: Beneficial and Adverse Effects of cART Affect Neurocognitive Function in HIV-1 Infection: Balancing Viral Suppression against Neuronal Stress and Injury. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2019;16(1):90–112. 10.1007/s11481-019-09868-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zondo S: The Cognitive Remediation of Attention in HIV Associated Neurocognitive Disorders (HAND): A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review.[Dataset]. figshare. 2023. 10.6084/m9.figshare.22196833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zondo S, Mulder A: Early Signs of Success in the Cognitive Rehabilitation of Children Living with HIV/AIDS in Rural South Africa Review of Literature Methodology Design. 2015;2(1):105–109. Reference Source [Google Scholar]