Abstract

Background

High potency synthetic opioids like fentanyl have continued to replaced or contaminate the supply of illicit drugs in North America, with fentanyl test strips (FTS) often used as a harm reduction tool for overdose prevention. The available evidence to support FTS for harm reduction has yet to be summarized.

Methods

A search of PubMed, Ovid Embase and Web of Science was conducted in March 2023. A two-stage review was conducted to screen by title and abstract and then by full text by two reviewers. Data were extracted from each study using a standardized template.

Results

A total of 91 articles were included, mostly from North America, predominantly reporting on FTS along with other harm reduction tools, and all conducted after 2016. No randomized controlled trials are reported. Robust evidence exists supporting the sensitivity and specificity of FTS, along with their acceptability and feasibility of use for PWUD and as a public health intervention. However, limited research is available on the efficacy of FTS as a harm reduction tool for behavior change, engagement in care, or overdose prevention.

Conclusions

Though fentanyl test strips are highly sensitive and specific for point of care testing, further research is needed to assess the association of FTS use with overdose prevention. Differences in FTS efficacy likely exist between people who use opioids and non-opioid drugs, with additional investigation strongly needed. As drug testing with point-of-care immunoassays is embraced for non-fentanyl contaminants such as xylazine and benzodiazepines, increased investment in examining overdose prevention is necessary.

Keywords: fentanyl test strips, drug checking, community drug checking, drug testing

INTRODUCTION

Drug overdoses in North America have continued to increase over the past few years, with over 100,000 deaths in 2021, of which 70,601 were from synthetic opioids like fentanyl.1 Originally mixed into heroin and other opioids, fentanyl has entirely replaced heroin in the opioid supply in some contexts, even becoming the drug of choice for some people who use drugs (PWUD).2 Concurrently, fentanyl contamination in non-opioid drugs is becoming more commonplace.3 Given the small quantity of fentanyl needed to cause respiratory suppression and overdose, attempts to identify the drug as a contaminant have been emphasized by harm reduction organizations,4 physicians,5 and public health practitioners.6

A wide range of drug checking services (DCS) exist to help determine the components of a drug sample, including fentanyl test strips (FTS). Originally designed to test an individual’s urine for fentanyl and its metabolites after drug use,7 FTS are now frequently used as a method for direct drug checking to assess the presence or absence of fentanyl in a sample. FTS are thought to serve as a harm reduction tool for PWUD by allowing modification of drug consumption practices prior to consumption.8 Positive behavior change (PBC) from a FTS result, such as discarding a batch of drugs or using less of the drugs if fentanyl is detected, is thought to decrease the risk of a fentanyl overdose.9

FTS are currently embraced in many public health campaigns to end the opioid overdose epidemic alongside other interventions with strong evidence of benefit, including naloxone, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), syringe services programs, and overdose prevention centers. Given their inexpensive cost and simple design, point-of-care immunoassay-based consumer testing is now expanding beyond fentanyl, with calls for increased access to xylazine test strips as additional contaminants enter the drug supply.10

However, to date, there have been no comprehensive reviews synthesizing data on the effectiveness of FTS among PWUD, particularly with regards to acceptability, feasibility, resulting behavior change, and overdose prevention. To address this gap, we provide a scoping literature review on FTS to assess the state of current research and identify priority areas for research around FTS for harm reduction.

METHODS

Data sources and searches

The project was registered with Open Science Framework (OSF) on March 6, 2023. A literature search was conducted to find abstracts relating to fentanyl test strips, using comprehensive search terms (made available on OSF), and a librarian (FL) searched PubMed, Ovid Embase and Web of Science Core Collection on March 7, 2023.

Study selection

We employed a two stage review methodology as described by the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews11(p4) and used the Covidence web application12 to review articles. Two reviewers (EK, MBG) screened article titles and abstracts for inclusion, followed by full-text screening and finally full-text reading for characterization of literature in accordance with the methodology described by Grant and Booth.13 The two reviewers discussed articles where discrepancies existed to come to a consensus on inclusion.

Due to the relatively low volume of articles, we included articles with primary data on FTS as a harm reduction tool, which could include measures relating to FTS accuracy and reliability, acceptability, and feasibility of use by community, feasibility of inclusion in public health interventions, behavior change from test results, and overdose-related outcomes. We did not restrict by nation of origin but did restrict to English language articles. Due to citation limitations, only the first 50 references are included here, with the entire reference list in Appendix 1.

Extraction and topics

After full text screening, data were extracted using a standardized template (available on OSF). Articles were classified by country of study, year of data collection initiation and completion, study design type, role of fentanyl test strips within the study, drug types studied (opioid, non-opioid, or both), and the domain of reported evidence. All reported data on FTS were also extracted from each text. Studies were organized by domain of evidence and included in the corresponding sections of the manuscript. Throughout writing, papers were frequently reviewed to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness of extracted data.

RESULTS

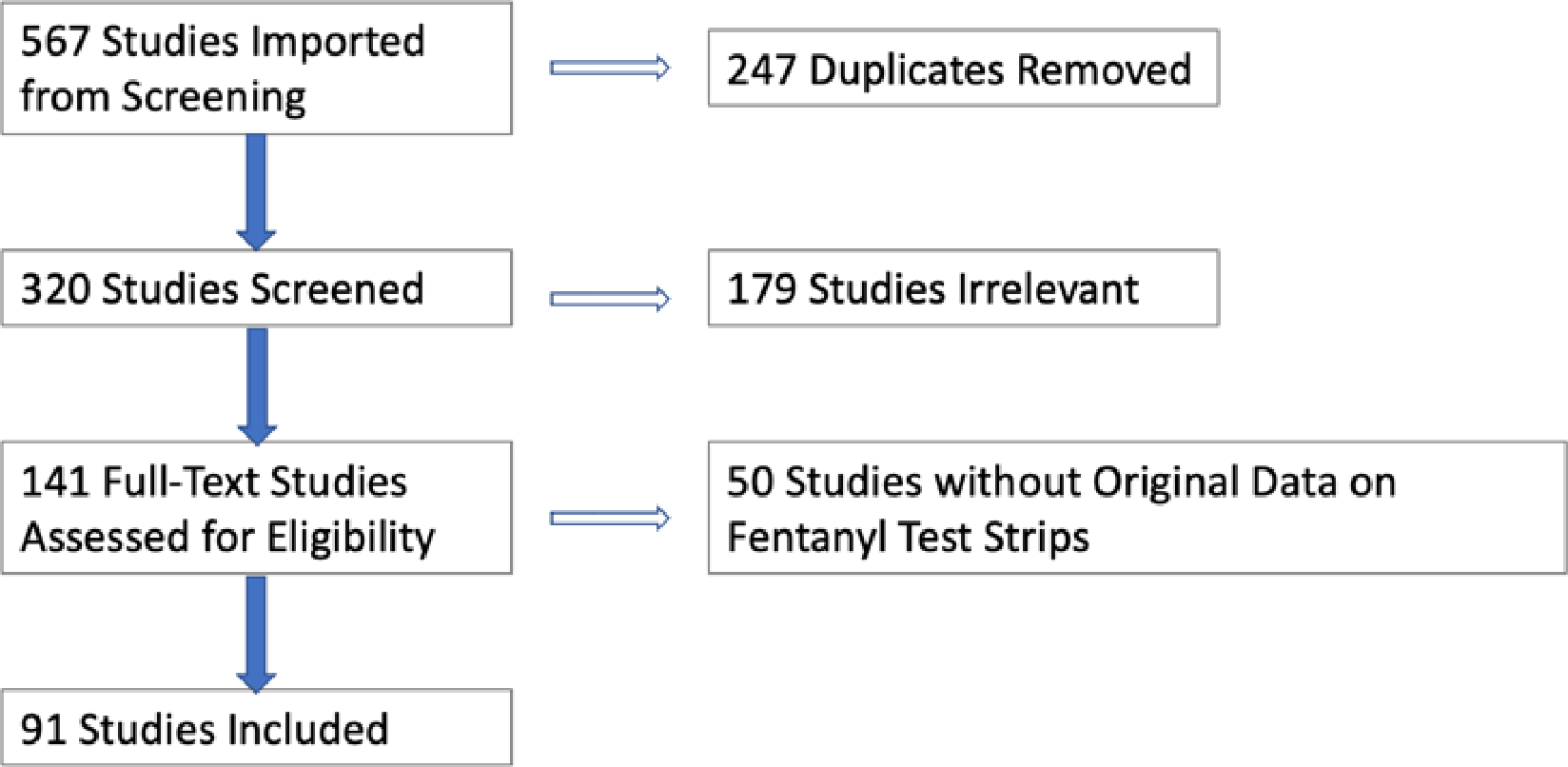

Our search returned 567 articles, and after de-duplication, title and abstract screening, and full text screening we analyzed 91 articles using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Figure 1, Table 1). All included studies were conducted after 2016, with the majority (99%) in North America. There were no randomized controlled trials, and almost half were qualitative studies. Most articles included FTS along with other harm reduction interventions, and most studied the use of FTS among individuals using both opioid and non-opioid drugs. The overall study population across all papers totaled 8,929 people, with a median of 44 participants per study.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Sheet

Table 1.

Study Features of Included Articles (N = 91 studies)

| Study Feature | N (studies) | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Year of Data Collection (completion) | ||

| - Before 2016 | 0 | 0% |

| - 2016 | 1 | 1% |

| - 2017 | 16 | 18% |

| - 2018 | 13 | 14% |

| - 2019 | 20 | 22% |

| - 2020 | 8 | 9% |

| - 2021 | 19 | 21% |

| - 2022 | 6 | 7% |

|

| ||

| Country of Study | ||

| - United States | 58 | 64% |

| - Canada | 29 | 32% |

| - Mexico | 3 | 3% |

| - Australia | 1 | 1% |

|

| ||

| Design Type | ||

| - Randomized controlled trial | 0 | 0% |

| - Non-randomized experimental study | 1 | 1% |

| - Cohort Study | 8 | 9% |

| - Cross sectional study | 3 | 3% |

| - Qualitative Research | 39 | 43% |

| ○ Interviews | 34 | 37% |

| ○ Surveys | 12 | 13% |

| ○ Focus Groups | 0 | 0% |

| - Case series | 1 | 1% |

| - Case Report | 0 | 0% |

| - Diagnostic test accuracy study | 14 | 15% |

| - Quality Improvement | 5 | 5% |

| - Mixed Methods/Other | 13 | 14% |

|

| ||

| Study Focus Primarily on FTS | 39 | 43% |

|

| ||

| Drug Types Studied | ||

| - Opioid Only | 13 | 14% |

| - Opioids and Other Drugs | 69 | 76% |

| - Only Non-Opioid Drugs | 3 | 3% |

Evidence on FTS predominantly focused on test accuracy, acceptability, and feasibility both to community use and as a public health intervention (Table 2). Nearly 1 in 3 articles included information on the impact of FTS results on individual behaviors, and only 2 articles provided data on overdose outcomes.

Table 2.

Number of Articles for Each Evidence Domains on FTS Use (N = 91)

| Evidence Domain | Number of Studies |

|---|---|

| Test Accuracy and Reliability | 16 |

| Acceptability to Community | 40 |

| Feasibility of use by Community | 41 |

| Feasibility of use as Public Health Intervention | 17 |

| Behavior Change Based on Results | 37 |

| Overdose-Related Outcomes | 2 |

FTS accuracy and reliability

Originally developed and approved for detection of fentanyl and its metabolites in urine samples after drug use, FTS have been shown to be accurate and reliable immunoassays for use in direct drug testing after dilution with at least 50mL of water or until a limit of detection of 0.100mcg/mL.7,14,15 When used for direct drug testing, FTS have approximately 96.3–98% sensitivity and 89.2–89.4% specificity for fentanyl.16,17

FTS detect fentanyl in both “China white” and “black tar” heroin,18,19 in counterfeit pills,20 and in non-opioid drugs including xylazine,21 alprazolam,20,22 cocaine,16,23 counterfeit Adderall pills,20 crystal methamphetamine,18 and psychedelics.24 False positives can occur at high concentrations of certain non-opioid drugs, including cocaine, gabapentin, alprazolam, buprenorphine-naloxone, methamphetamine, MDMA, and diphenhydramine,14,16 which can be prevented with drug dilution. Notably, only some fentanyl analogs test positive using FTS, such as acetyl fentanyl and furanylfentanyl, while others including carfentanil, norcarfentanil, norfentanyl test negative.15,16,25,26

Fentanyl can also be detected using more sophisticated methods like gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS), and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR).17,27 However, given their inexpensive cost and simple design, FTS are often the test of choice for point-of-care consumer testing.

Acceptability of FTS use by community

A high level of interest and acceptability of FTS use is documented among PWUD, particularly individuals fearful of fentanyl28,29 or overdose.30–33 Willingness to use FTS is reported in five studies, ranging from 43%–85% of study participants.33–37 Notably, interest in FTS use is not always motivated by avoiding fentanyl, as the proliferation of fentanyl into the drug market has led some PWUD preferring fentanyl as their drug of choice.2,30,34,38,39 Participants in many studies agreed that testing should occur when obtaining a new batch of drugs, purchasing from a new seller, purchasing a large amount, using drugs that look different than prior, using what has been described as a “strong” batch, purchasing from an area with high levels of overdose, or selling to others.39–42

Acceptability of FTS may be limited by comfort with pre-existing methods for detecting fentanyl, such as the use of color, texture, smell, taste, and tester shots32,33,43–47 Purchasing drugs from a known and trusted dealer is often thought of as a sufficient method of protection from fentanyl and may limit acceptability.41,42

Limitations of FTS in an evolving drug supply

Many participants expressed that knowing whether or not fentanyl was present was insufficient to make an informed choice on usage or necessary harm reduction measures, especially in contexts where the opioid drug supply has been almost entirely replaced with fentanyl.31,41,48–54 Among people using opioids regularly with some tolerance to fentanyl, changes in the percentage of fentanyl is considered more valuable information for overdose prevention.

Among people without an opioid tolerance or for whom a non-opioid is their drug of choice, knowledge about the evolving drug supply limits acceptability. Individuals who do not perceive their drugs as at-risk of fentanyl contamination have less interest in FTS use,32,55 while those with knowledge of fentanyl contamination and without an opioid tolerance are highly interested in FTS use,2,47,56,57 as are individuals who experienced atypical symptoms when using their drug of choice.58

FTS acceptability is also impaired by their inability to provide information on contaminants with non-fentanyl substances, including fentanyl analogs,2 xylazine,21 synthetic cannabinoids,59 phenacetin,23 levamisole,23 and etizolam.60 Many participants thus desired more comprehensive DCS that could provide accurate information on the exact composition of a substance.48–50,61,62

Feasibility of FTS Use

Despite the high acceptability of FTS, rates of utilization are appreciably lower, with the wide range of documented FTS use ranging from 1%–80% (median of 19%, Supplemental Table 1). DCS were more likely to be used by individuals who have witnessed an overdose in the past 6 months, suspect fentanyl exposure, inject in public, participate in sex work, and have experienced a non-fatal overdose.63

Ease of use

FTS are often considered “easy” or straightforward to use, but can be error prone.30,48,64–67 For instance, positive FTS results occurred five times more frequently at home than at a DCS program.66 The finding may indicate the increased likelihood of inadvertent drug and/or test strip contamination in real world settings, or highlight limitations in FTS performance in non-laboratory settings. Similarly, difficulty interpreting FTS results ranged from 3% to almost 34%.38,39,52 False positive and false negative results, though rare, can also cause confusion and impact the degree to which PWUD trust their accuracy.58

Misinformation about how to interpret FTS results have also been reported, such as the erroneous belief that the intensity of the test indicates the purity of fentanyl in the supply, or that a negative FTS indicates the presence of xylazine (and conversely that a positive FTS precludes xylazine contamination).10,30,48

It is unclear if trainings improve ease and feasibility of FTS use, with some authors reporting confusion despite trainings, and others showing increased feasibility of FTS after trainings.30,53

Timing of FTS Use with relation to drug use

Individuals using FTS as a harm reduction tool usually perform direct drug checking prior to consumption, but seven studies show rates of post-consumption testing from either testing urine or drug paraphernalia ranging from 13% to 58% of participants.38,47,58,66,68,69 Behavior change was noted with both pre- and post-consumption FTS use, with two studies showing PWUD having a preference for pre-consumption testing28,38,70 and two studies providing data in favor of post-consumption testing.64,71

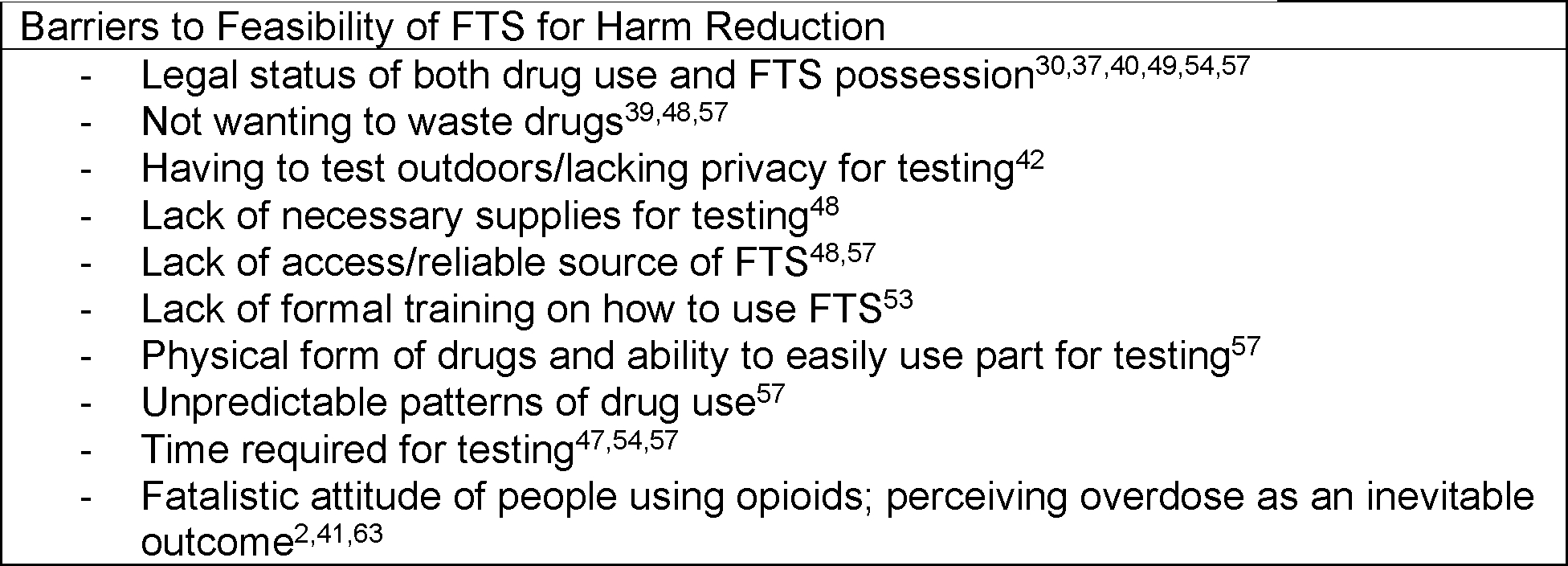

Barriers and facilitators to use

Many barriers to FTS uptake are documented (Figure 2), with the most common cited barrier the illegality of drugs and drug paraphernalia. PWUD have reported that the criminalization of substances at each step of the supply chain poses a significant barrier to ensuring safety of drugs prior to consumption, though some PWUD had no concerns about police while using FTS.30,40,50,72,73 Some postulated that FTS could delay drugs use and make it more likely to be arrested.54 Fear of judgment or prosecution was thought to be exacerbated in small-town, rural areas.37 In some contexts, FTS are themselves considered illegal or exist in a legal gray space where only post-consumption use is legal.74

Figure 2.

Barriers to the Feasibility of FTS for Harm Reduction

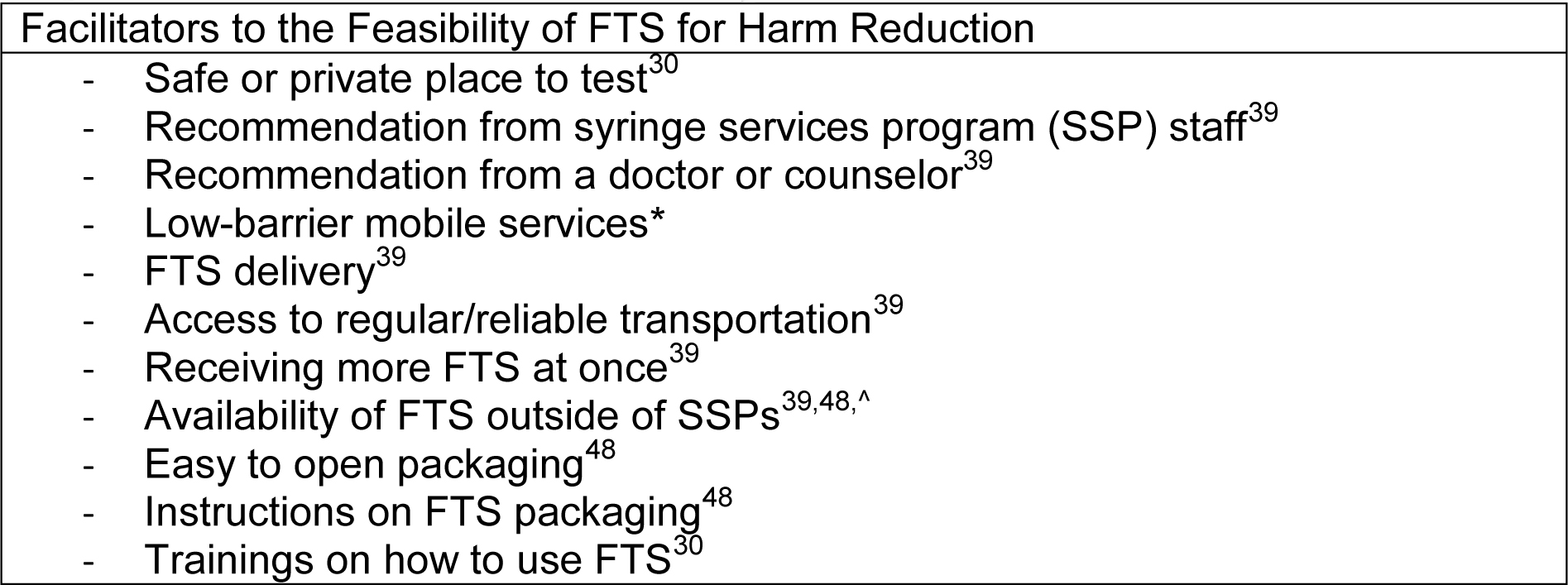

Overall, enhanced access and low barriers to FTS are the best methods for improving uptake and usage, with some variations unique to each context of drug use (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Facilitators to the Feasibility of FTS for Harm Reduction

* Lowenstein M, Abrams M, Shimamoto K. Exploring Patient Perspectives on Low-Threshold Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(Supplement 2):S271. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07653-8

^ Shin SS, LaForge K, Stack E, et al. “It wasn’t here, and now it is. It’s everywhere”: fentanyl’s rising presence in Oregon’s drug supply. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):76. doi:10.1186/s12954-022-00659-9

Overall satisfaction with use

Most PWUD, regardless of context, report positive experiences using FTS, ranging from 49% to 96% of participants finding FTS useful and wanting to use them again (Supplemental Table 2).

Feasibility of FTS distribution as a public health intervention

Many studies report FTS distribution to PWUD for harm reduction (Table 3), usually focusing on the number of FTS distributed. Importantly, few studies report data on a net change in FTS use, either by showing a change in number of participants using FTS from baseline, or by showing a change in the frequency of FTS use by participants. Stakeholders and care providers involved in FTS distribution have predominantly reported positive experiences.75–78

Table 3.

Published Interventions Demonstrating the Feasibility of FTS for Harm Reduction

| Study | Intervention | FTS related outcomes (if any) |

|---|---|---|

| Arendt 202281 | Distribution of harm reduction services through an automated dispensing machine, including FTS | – 10,155 FTS distributed – Test strips detected fentanyl 937 times, with 702 instances resulting in no use or less use of the drug – County has seen 10% decrease in unintentional overdose deaths |

| Bolinski 202284 | Continued provision of harm reduction services, including FTS, during Covid-19 lockdowns through PPE, social distancing, and contactless delivery | FTS were provided through a mobile model during the pandemic, and widely discussed by participants as important resources |

| Brown 202385 | University of Southern California pharmacy students partnered with student health services to provide opioid overdose education and distribute harm reduction kits, including FTS | In 1 year, more than 300 USC students requested kits |

| Canning 202186 | A Connecticut statewide collaboration started an overdose monitoring program that identified a cluster of overdoses from fentanyl-contaminated crack cocaine, and provided local PWUD with harm reduction services, including FTS | 300 test strips distributed during a 5-day period to opioid-naïve crack cocaine users, with no additional overdoses until weeks later |

| Cook 202287,88 | Group medical visits were conducted with walk in visits and access to harm reduction services, including FTS | 62 visits occurred, with each group visit attended by 7.61 patients, with 34% of patients pursuing harm reduction services |

| Goldman 201964 | Participants trained in FTS use and given 10 FTS for personal use | 62 of 93 young adults provided with free FTS returned 2–4 weeks later having used at least one FTS |

| Lima 202289 | Patients with an opioid-related visit to the ED were provided with FTS within the emergency department in Chicago, Illinois | FTS were offered to 23 patients, of which 18 accepted the FTS, and 16 took the FTS home |

| Olson 202273 | Municipal police departments in Massachusetts distributed FTS to PWUD | 320 kits distributed in 3 months, leading to 318 referrals or follow up services |

| Park 202080 | FTS distribution to female sex workers who use drugs in Baltimore | 5 FTS were distributed to 103 participants, of which 57 returned for follow up and reported use of 1 or more FTS |

| Park 202152 | FTS were distributed to PWUD at SSP in Baltimore and Delaware | 17,000 FTS distributed over 7 months with utilization of FTS in Baltimore of 70% and Delaware of 77% |

| Perera 202290 | Provided harm reduction services, including FTS, as part of hospital-based addiction care | 195 individuals provided with harm reduction kits over 12 months |

| Reed 202277 | ED staff distributed FTS to PWUD presenting to care at a large academic medical center | Over 3 months, 2540 FTS distributed to PWUD through 127 packs of 20 strips |

| Winograd 202274 | Implementation of a contingency management program in Missouri for individuals using stimulants, providing clients with harm reduction services and FTS | 4,118 FTS kits (20,590 strips) were distributed to organizations serving individuals using stimulants within 8 months |

Behavior Change from FTS Results

The effectiveness of FTS as a harm reduction tool centers on providing PWUD with information about the risk of overdose from a particular drug supply, allowing the opportunity for PWUD to modify drug consumption practices to decrease overdose (termed positive behavior change, or PBC). Examples of PBC after a positive FTS result include not using the drug, using with others instead of alone, and ensuring naloxone is available when using. Notably, PWUD often use harm reduction tools and embrace PBC, regardless of FTS usage.31,37,40,53,56,62,79

Only two studies investigated behavior change before and after FTS counseling and distribution. In a prospective cohort study of young adults in Rhode Island who inject drugs, 68% of individuals who received a positive test result reported a positive behavior change; of those who did not even use FTS, only 32% reported PBC.70

The second study is a FTS training and distribution among 103 female sex workers in Baltimore, showing that women with a positive FTS result were more likely to report PBC (67% compared to 10% of women with a negative FTS result).80 Of women who had used at least 1 FTS, there was a statistically significant decrease in self-reported drug use for both illicit opioids and benzodiazepines.80

Among seven studies assessing PBC without introducing FTS as a controlled intervention, a median of 55% (range: 23–75%) of participants across the eight locations reported any positive change (Supplemental Table 3).19,38,52,55,66,71,81 Results from studies assessing for actual behavior change or theoretical behavior change in the hypothetical setting of a positive FTS are summarized in Table 4. The most common PBCs included using smaller amounts, not using the drug, going slower, or using a “tester shot” to see how the drug feels before administering the whole dose.

Table 4.

Number of Studies Documenting Reported and Theoretical Behavior Change using FTS for Harm Reduction

| Behavior Change | Actual Behavior Change After FTS Result Documented (# of studies) | Theoretical Behavior Change from FTS Documented (# of studies) | Total (# of studies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using Smaller Amounts of Drugs | 2,19,30,37,38,43,52,55,56,69,71,91–93 | 32,33,94 | 17 |

| Changing the route of administration | 37,38 | 2 | |

| Using “tester shots” | 2,37,38,52,91,93 | 32,67 | 8 |

| Going “slower” | 38,52,56,66,71,91,93,95 | 67,95 | 10 |

| Using with another person | 2,64,66,71,95 | 67,95 | 7 |

| Having a “check in” plan | 2,52,93 | 3 | |

| Keeping naloxone available | 31,42,56,64,71 | 67,95 | 7 |

| Using at an overdose prevention center | 92 | 1 | |

| Not buy from same dealer again | 43,93 | 32,33 | 4 |

| Not using the drug (including sell or give to others) | 19,30,53,55,56,64,71,93,95 | 32,33,67,94,95 | 14 |

| Using more or faster | 66,47 | 94 | 3 |

| Engagement with addiction services | 71,73 | 2 |

However, PWUD may opt to use drugs as usual despite a positive FTS to alleviate withdrawal symptoms, or because they already engage in harm reduction practices, have a pre-existing tolerance to fentanyl or an apathy towards its presence, are skeptical of the result, or desire fentanyl as their drug of choice.30,80

Few studies discuss the role of FTS in engaging PWUD in additional addiction care, with two showing increased referrals to additional services for people who use drugs, but not commenting on engagement with or retention in addiction services or treatments.71,73

Notably, a few participants in two studies report that they use or would use FTS to use more drugs or use drugs faster.47,66 One participant reported that a negative FTS would require him to “do a little more, because it won’t be as strong,”47 while another study found six participants (1.8% of the sample) who reported riskier behavior after a positive FTS result.66

PWUD with a non-opioid drug of choice may be more likely to change behavior after a positive FTS result, with 80% of individuals using stimulants reporting theoretical PBC.30,36,57 Yet a positive FTS result in this population may also cause individuals to falsely believe they have a tolerance for fentanyl.31

Of note, individuals who sell drugs may also use FTS, including to navigate what drugs they sell and to whom.50,51,62

Overall, among individuals concerned about fentanyl, a positive FTS likely results in a net increase in PBC, though the true efficacy of these PBCs at preventing overdose remains unknown.

Overdose related outcomes after FTS use

The primary goal of FTS distribution to PWUD is opioid overdose prevention, yet only two of the 91 published articles reviewed explicitly discuss overdose related outcomes.

The first investigated overdose related outcomes at an overdose prevention center in Vancouver, where only 1% of visits resulted in drug checking and post-consumption testing was most common.69 Among pre-consumption tests, a positive FTS result was associated with increased odds of dose reduction intention (9.36). Regardless of FTS result, reduction intention was associated with a reduced odds of overdose (0.41) and a reduced odds naloxone administration (0.38), suggesting the use of FTS to prompt reduction intention was more important than the FTS result.69

The second article evaluated the impact of a machine in Hamilton County, Ohio that dispensed harm reduction supplies (such as naloxone and safe injection equipment) as well as 10,155 FTS in its first year of service.81 Of 105 clients who completed a survey about the impact of the machine, participants reported that FTS directly from the machine detected fentanyl 937 times, resulting in 702 instances of individuals choosing to discard the drug or use less of it.81 During this timeframe, Ohio saw an increase of overdose deaths by about 5% overall, while Hamilton County had a decrease of 10%, along with a decrease in overdose related emergency department visits.81 As noted by the authors, evaluating the impact of FTS distributed by the machine is confounded by the inclusion of the lifesaving medication naloxone among the supplies provided, and absence of a true control group.

Overall, only limited data suggest that FTS use as a harm reduction strategy decreases overdose rates or overdose mortality.

DISCUSSION

A sizable body of evidence supports the high sensitivity and specificity of FTS for detecting fentanyl both in pre- and post-consumption drug testing of both opioid and non-opioid drugs. FTS are limited in nature in their ability to detect only fentanyl and some of its analogs, without providing PWUD information about the concentration of fentanyl in a sample, and are thus becoming increasingly anachronistic among PWUD in many contexts. In Canada, for instance, a mean fentanyl concentration was found to be between 7–8.9%, but more than 16% of fentanyl samples had concentrations more than 17.7%.60,82 Though all of these samples will test positive with FTS, only some are likely to result in overdose for people with regular opioid use in Canada who have developed some degree of tolerance to fentanyl. In contrast, in other countries and contexts where fentanyl has yet to infiltrate the drug supply, FTS may provide the exact information PWUD need to prevent overdose.

Among individuals seeking non-opioid drugs of choice or those more casually experimenting with drugs, increased awareness of fentanyl and concern around its contamination of the drug supply likely results in increased usage of FTS. This opioid-naïve population may be the ideal target population for FTS at a time when fentanyl has largely saturated the opioid drug supply in the North American context. Campaigns to raise awareness around drug contamination are urgently needed, emphasizing that fentanyl may be in many types of non-prescribed drugs, and that numerous drug checking technologies exist.

Though high levels of acceptability of FTS for harm reduction are reported, rates of uptake of FTS are substantially lower, which may be from fentanyl infiltration into the drug supply and/or limited knowledge around FTS.32,34,83 Drug checking is further impeded by confusion around FTS results and a lack of safe spaces to perform drug testing. Though current United States policy attempts to expand funding and availability of FTS, additional investigation into facilitators of FTS and DCS use is warranted, including critical evaluation of the role of drug enforcement policies. Implementation science research may therefore be an optimal method to study FTS as a public health intervention.

Positive behavior change when receiving a positive FTS is widely documented, and may highlight an opportunity for public health messaging for PWUD to treat all drugs as if they contain fentanyl. Public health providers should emphasize the importance of universal practice of harm reduction techniques such as using with others and carrying naloxone. Similarly, interventions such as using less drug, using drugs more slowly, and taking tester shots may decrease the rate of drug administered regardless of substance, and may also be helpful universal harm reduction techniques. Further research on the safety and effectiveness of these methods for overdose prevention is urgently needed.

Significantly, our research shows a dearth of evidence regarding the use of FTS as a harm reduction tool to prevent opioid overdoses or to engage PWUD into addiction care. Distributing FTS can allow PWUD to learn more about their drugs, and is warranted in the midst of the current opioid overdose epidemic when all possible methods of overdose prevention are needed. Inherent ethical and logistical challenges exist in studying drug testing through a randomized clinical trial. Yet, as FTS are made available, best attempts at evaluation of its efficacy through rigorous comparative cohort studies is urgently needed.

With increasing contamination of the drug supply with non-fentanyl substances such as xylazine and benzodiazepines, the utility of a test specific to one drug will likely decrease. Though each contaminant can be tested for with an immunoassay, this review suggests that it is unrealistic to expect PWUD to test for the presence/absence of each with individual tests. More comprehensive drug checking services such as FTIR and GC/MS are likely more acceptable and feasible at this stage of the epidemic. Resources are needed to increase access to comprehensive DCS in the United States, and to research the impact of these services.

Our scoping review is limited by our use of English language texts only, the inclusion of literature published only until March 2023, and reliance on peer-reviewed and published reports.

CONCLUSION

Fentanyl test strips are highly sensitive and specific when used as point of care testing. Limited evidence currently exists showing the utility of FTS for overdose prevention. Further longitudinal research is needed to assess the efficacy of FTS among PWUD, with particular attention to differences that may exist between people who use opioids and those who do not intend to use opioids. As community drug testing with point of care immunoassay strips is embraced for non-fentanyl contaminants such as xylazine and benzodiazepines, increased investment in examining outcomes from point of care drug testing is necessary.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Primary Funding:

NIDA R25DA033211

NIH UL 1TR001445

HRSA T25HP37605

Footnotes

Declarations of Competing Interests:

Dr. Lee receives in-kind study drugs for an NIH-sponsored clinical trial from Alkermes and Indivior. Dr. Lee is a science advisor for Oar Health. There are no other conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Drug Overdose Death Rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Published February 9, 2023. Accessed June 16, 2023. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urmanche AA, Beharie N, Harocopos A. Fentanyl preference among people who use opioids in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;237:109519. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell E Rapid Analysis of Drugs: A Pilot Surveillance System To Detect Changes in the Illicit Drug Supply To Guide Timely Harm Reduction Responses — Eight Syringe Services Programs, Maryland, November 2021–August 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7217a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fentanyl Test Strip Pilot. National Harm Reduction Coalition. Accessed July 2, 2023. https://harmreduction.org/issues/fentanyl/fentanyl-test-strip-pilot/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.AMA to urge using opioid litigation funds to train physicians in opioid treatment. American Medical Association. Published November 15, 2022. Accessed July 2, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-urge-using-opioid-litigation-funds-train-physicians-opioid [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fentanyl Test Strips: A Harm Reduction Strategy. Published February 16, 2023. Accessed July 2, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/fentanyl-test-strips.html

- 7.Bergh MSS, Øiestad ÅML, Baumann MH, Bogen IL. Selectivity and sensitivity of urine fentanyl test strips to detect fentanyl analogues in illicit drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;90:103065. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Federal Grantees May Now Use Funds to Purchase Fentanyl Test Strips. Published April 7, 2021. Accessed July 2, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/202104070200

- 9.Appel G, Farmer B, Avery J. Fentanyl Test Strips Empower People And Save Lives—So Why Aren’t They More Widespread? Health Aff Forefr. doi: 10.1377/forefront.20210601.974263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reed MK, Imperato NS, Bowles JM, Salcedo VJ, Guth A, Rising KL. Perspectives of people in Philadelphia who use fentanyl/heroin adulterated with the animal tranquilizer xylazine; Making a case for xylazine test strips. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2022;4:100074. doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chapter 4: Searching for and selecting studies. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-04

- 12.Covidence - Better systematic review management. Covidence. Accessed June 11, 2023. https://www.covidence.org/

- 13.Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lockwood TLE, Vervoordt A, Lieberman M. High concentrations of illicit stimulants and cutting agents cause false positives on fentanyl test strips. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18(1) (no pagination). doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00478-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green TC, Park JN, Gilbert M, et al. An assessment of the limits of detection, sensitivity and specificity of three devices for public health-based drug checking of fentanyl in street-acquired samples. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;77:102661. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JN, Sherman SG, Sigmund V, Breaud A, Martin K, Clarke WA. Validation of a lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay for the detection of fentanyl in drug samples. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;240:109610. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCrae K, Tobias S, Grant C, et al. Assessing the limit of detection of Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and immunoassay strips for fentanyl in a real-world setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2020;39(1):98–102. doi: 10.1111/dar.13004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleiz C, Arredondo J, Chavez A, et al. Fentanyl is used in Mexico’s northern border: current challenges for drug health policies. Addiction. 2020;115(4):778–781. doi: 10.1111/add.14934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman-Meza D, Arredondo J, Slim S, et al. Behavior change after fentanyl testing at a safe consumption space for women in Northern Mexico: A pilot study. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;106:103745. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman J, Godvin M, Molina C, et al. Fentanyl, Heroin, and Methamphetamine-Based Counterfeit Pills Sold at Tourist-Oriented Pharmacies in Mexico: An Ethnographic and Drug Checking Study. medRxiv. Published online January 28, 2023:2023.01.27.23285123. doi: 10.1101/2023.01.27.23285123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobias S, Shapiro AM, Wu H, Ti L. Xylazine Identified in the Unregulated Drug Supply in British Columbia, Canada. Can J Addict. 2020;11(3):28–32. doi: 10.1097/CXA.0000000000000089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tobias S, Shapiro AM, Grant CJ, Patel P, Lysyshyn M, Ti L. Drug checking identifies counterfeit alprazolam tablets. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;218:108300. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel P, Guzman S, Lysyshyn M, et al. Identifying Cocaine Adulteration in the Unregulated Drug Supply in British Columbia, Canada. Can J Addict. 2021;12(2):39–44. doi: 10.1097/cxa.0000000000000112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCrae K, Tobias S, Tupper K, et al. Drug checking services at music festivals and events in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107589. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crepeault H, Socias ME, Tobias S, et al. Examining fentanyl and its analogues in the unregulated drug supply of British Columbia, Canada using drug checking technologies. Drug Alcohol Rev. Published online November 24, 2022. doi: 10.1111/dar.13580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wharton RE, Casbohm J, Hoffmaster R, Brewer BN, Finn MG, Johnson RC. Detection of 30 Fentanyl Analogs by Commercial Immunoassay Kits. J Anal Toxicol. 2021;45(2):111–116. doi: 10.1093/jat/bkaa181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karch L, Tobias S, Schmidt C, et al. Results from a mobile drug checking pilot program using three technologies in Chicago, IL, USA. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;228:108976. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krieger MS, Yedinak JL, Buxton JA, et al. High willingness to use rapid fentanyl test strips among young adults who use drugs. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0213-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krieger Maxwell. ACMT 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts: High Willingness to Use Rapid Fentanyl Test Strips Among Young Adults Who Use Drugs. J Med Toxicol Conf 15th Annu Sci Meet Am Coll Med Toxicol ACMT. 2018;14(1). https://ezproxy.med.nyu.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=emed19&AN=621476648 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed MK, Guth A, Salcedo VJ, Hom JK, Rising KL. “You can’t go wrong being safe”: Motivations, patterns, and context surrounding use of fentanyl test strips for heroin and other drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;103:103643. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKnight C, Des Jarlais DC. Being “hooked up” during a sharp increase in the availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyl: Adaptations of drug using practices among people who use drugs (PWUD) in New York City. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;60:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen ST, O’Rourke A, White RH, Sherman SG, Grieb SM. Perspectives on Fentanyl Test Strip Use among People Who Inject Drugs in Rural Appalachia. Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(10):1594–1600. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1753773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherman SG, Morales KB, Park JN, McKenzie M, Marshall BDL, Green TC. Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: Baltimore, Boston and Providence. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;68:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mistler CB, Rosen AO, Eger W, Copenhaver MM, Shrestha R. Fentanyl Test Strip Use and Overdose History among Individuals on Medication for Opioid Use Disorder. Austin J Public Health Epidemiol. 2021;8(5). Accessed March 15, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9249264/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rammohan I, Bouck Z, Fusigboye S, et al. Drug checking use and interest among people who inject drugs in Toronto, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;107:103781. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kennedy MC, Scheim A, Rachlis B, et al. Willingness to use drug checking within future supervised injection services among people who inject drugs in a mid-sized Canadian city. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:248–252. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walters SM, Felsher M, Frank D, et al. I Don’t Believe a Person Has to Die When Trying to Get High: Overdose Prevention and Response Strategies in Rural Illinois. Int J Env Res Public Health. 2023;20(2). doi: 10.3390/ijerph20021648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peiper NC, Clarke SD, Vincent LB, Ciccarone D, Kral AH, Zibbell JE. Fentanyl test strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program in the Southeastern United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tilhou AS, Birstler J, Baltes A, et al. Characteristics and context of fentanyl test strip use among syringe service clients in southern Wisconsin. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00720-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodyear T, Mniszak C, Jenkins E, Fast D, Knight R. “Am I gonna get in trouble for acknowledging my will to be safe?”: Identifying the experiences of young sexual minority men and substance use in the context of an opioid overdose crisis. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00365-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bardwell G, Boyd J, Arredondo J, McNeil R, Kerr T. Trusting the source: The potential role of drug dealers in reducing drug-related harms via drug checking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swartz JA, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Jimenez AD, Robison-Taylor L, Prete E. Feasibility Study of Using Mobile Phone-Based Experience Sampling to Assess Drug Checking by Opioid Street Drug Users. Res Sq. Published online January 13, 2023:rs.3.rs-2472117. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2472117/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhodes B, Costenbader B, Wilson L, et al. Urban, individuals of color are impacted by fentanyl-contaminated heroin. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zibbell JE, Peiper NC, Duhart Clarke SE, et al. Consumer discernment of fentanyl in illicit opioids confirmed by fentanyl test strips: Lessons from a syringe services program in North Carolina. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;93 (no pagination). doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCrae K, Wood E, Lysyshyn M, et al. The utility of visual appearance in predicting the composition of street opioids. Subst Abus. 2021;42(4):775–779. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1864569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaplowitz E, Macmadu A, Green TC, Berk J, Rich JD, Brinkley-Rubinstein L. “It’s probably going to save my life;” attitudes towards treatment among people incarcerated in the era of fentanyl. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;232:7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duncan Cance J, Bingaman A, Kane H, et al. A qualitative exploration of unintentional versus intentional exposure to fentanyl among people who use drugs in Austin, TX. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2023;63(1):317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed MK, Salcedo VJ, Guth A, Rising KL. “If I had them, I would use them every time”: Perspectives on fentanyl test strip use from people who use drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;140:108790. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallace B, van Roode T, Pagan F, et al. What is needed for implementing drug checking services in the context of the overdose crisis? A qualitative study to explore perspectives of potential service users. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00373-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace B, van Roode T, Burek P, Pauly B, Hore D. Implementing drug checking as an illicit drug market intervention within the supply chain in a Canadian setting. Drugs-Educ Prev Policy.:10. doi: 10.1080/09687637.2022.2087487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.