Abstract

Introduction

Despite declared life-course principles in non-communicable disease (NCD) prevention and management, worldwide focus has been on older rather than younger populations. However, the burden from childhood NCDs has mounted; particularly in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs). There is limited knowledge regarding the implementation of paediatric NCD policies and programmes in LMICs, despite their disproportionate burden of morbidity and mortality. We aimed to understand the barriers to and facilitators of paediatric NCD policy and programme implementation in LMICs.

Methods

We systematically searched medical databases, Web of Science and WHOLIS for studies on paediatric NCD policy and programme implementation in LMICs. Screening and quality assessment were performed independently by researchers, using consensus to resolve differences. Data extraction was conducted within the WHO health system building-blocks framework. Narrative thematic synthesis was conducted.

Results

93 studies (1992–2020) were included, spanning 86 LMICs. Most were of moderate or high quality. 78% reported on paediatric NCDs outside the four major NCD categories contributing to the adult burden. Across the framework, more barriers than facilitators were identified. The most prevalently reported factors were related to health service delivery, with system fragmentation impeding the continuity of age-specific NCD care. A significant facilitator was intersectoral collaborations between health and education actors to deliver care in trusted community settings. Non-health factors were also important to paediatric NCD policies and programmes, such as community stakeholders, sociocultural support to caregivers and school disruptions.

Conclusions

Multiple barriers prevent the optimal implementation of paediatric NCD policies and programmes in LMIC health systems. The low sociopolitical visibility of paediatric NCDs limits their prioritisation, resulting in fragmented service delivery and constraining the integration of programmes across key sectors impacting children, including health, education and social services. Implementation research is needed to understand specific contextual solutions to improve access to paediatric NCD services in diverse LMIC settings.

Keywords: adolescent health, health services research, child health, developing countries, noncommunicable diseases

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The mortality burden of paediatric non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is disproportionately high in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Compared with policies and programmes in paediatric communicable diseases and adult NCDs in LMICs, few systematic studies of those for paediatric NCDs have been done.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Paediatric NCDs lie mostly in the ‘other’ category of the conventional ‘5×5’ framing of NCD agendas, lending to their low visibility.

Health system fragmentation is a key barrier to implementing programmes in which children receive timely, age-specific care.

Because of children’s dependence on their families and communities, non-health sector factors have important impacts on successful implementation of effective NCD policies and programmes, for example, the task-shifting of NCD care to education workers.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

A reframing of the ‘5×5’ international agenda for tackling NCDs is required to bring more focus to paediatric NCDs, both in policymaking and in research.

The younger demographic profile of LMICs suggests that unless paediatric NCDs are adequately addressed, adult NCDs will become an even greater problem, since about 70% of premature deaths due to NCDs have their roots in risks established early in life.

The distinctiveness of children’s needs underscores the importance of committing to child-relevant implementation research that encompasses the sociocultural environment of NCD policies and programmes, extending beyond the bounds of the health system.

Introduction

The management of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has become a major public health focus worldwide. Despite the declared all-ages and life-course principles in international initiatives, there has been a disproportionate focus of NCD policies and programmes among older populations due to their higher prevalence. NCDs, however, have a profound impact on children and youth. As childhood mortality and morbidity associated with communicable diseases have diminished, the burden from NCDs has mounted.

NCDs are chronic conditions resulting from genetic, physiological, environmental and behavioural influences, rather than person-to-person transmission.1 2 Although the definition remains consistent across income levels and age groups, the patterns of prevalence and burden vary significantly. Globally, 1 in 10 youth live with a physical disability, with 80% residing in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).2 This statistic does not specify whether the results stem from communicable diseases, or NCDs, particularly injuries. As such, paediatric NCDs within LMICs necessitate comprehensive scope, inclusive of grey areas such as physical and congenital disabilities, as to not limit burden characterisation.

An estimated 1 million paediatric deaths (aged 0–19 years) were attributed to NCDs in 2017, and incident cases numbered about 250 million.2 Prevalence of the major NCDs, in millions, was estimated at: mental health disorders—231.3; injuries and violence—170.4; chronic respiratory disorders—108.9; cardiovascular disease—13.9; diabetes—8.8 and cancer—5.9.2 Among adolescents aged 10–19 years, about 20% of deaths in 2019 were attributable to NCDs.3 Childhood behavioural disorders comprised the highest combined mortality/morbidity toll in those aged 10–14 years, with 433 disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) lost per 100 000 population. Depressive disorders exacted the highest toll among those aged 15–19 years, with a loss of 497 DALYs/100 000.3

Moreover, the health behaviours that drive the development of NCDs in adulthood, such as tobacco and alcohol use, physical inactivity and unhealthy eating, often have their beginnings in childhood and adolescence. Akseer et al estimate that 80% of boys and girls aged 11–17 across all regions of the world have insufficient physical activity.4

As for many other diseases and conditions, the mortality due to paediatric NCDs in LMICs is disproportionately higher than in high-income countries (HICs). Lower GDP and health expenditure per capita are strong predictors of higher NCD burden among adults and adolescents.4 Approximately three-quarters of child deaths attributable to NCDs take place in LMICs, but this is likely an underestimate, as surveillance for and monitoring of childhood NCDs is limited in low-resource settings.2

In response, policies, regulations and programmes addressing NCDs in children and youth have been implemented in LMICs. For example, in the WHO Africa region, national strategies for health/family planning exist in 95% of countries; mental health, 82%; nutritional interventions, 80% and tobacco control, 79%, among others. Yet, the implementation status of these strategies remains largely unknown, as does the understanding of the challenges encountered and the successes achieved in their execution.4

To advance understanding of LMIC health system responses to paediatric NCDs, we conducted a systematic review to describe policy and programme implementation and to identify barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist.5 We systematically searched MEDLINE, EMBASE Classic, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science and WHOLIS from database inception to 23 July 2020. Search concepts included NCDs, policy and programme implementation or evaluation, LMICs and children, infants or adolescents (sample search strategy in online supplemental appendix A).

bmjpo-2024-002556supp001.pdf (219.1KB, pdf)

Screening and study selection

Inclusion criteria were: (a) addressed policy or programme implementation; (b) reported on an LMIC setting, based on World Bank classifications; (c) focused on one or more NCDs and (d) included paediatric populations (<18 years).6 We excluded editorials, commentaries, opinion pieces, formal systematic reviews, study protocols, studies with narrow clinical focus, studies on injuries, studies where no specific health intervention was described (eg, prevalence studies, cost-effective analyses), non-peer-reviewed published proceedings, conference abstracts and non-English language studies. Abstracts were imported into Covidence, and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two of three reviewers (LW, NM, KP). Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by joint full article review, and a fourth reviewer (AD) facilitated consensus when necessary. Two out of six reviewers (NM, GTN, LW, JN, BW, KP) independently screened full texts, and discrepancies were resolved by joint reviews. Two additional reviewers (CG, AD) helped reach consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction form was developed and piloted by NM (online supplemental appendix B). GN independently reviewed and extracted relevant data from each study, including, year of publication; NCD type; continuum-of-care component; policy/programme implementation stage, platform and system level; target population and geographic area. Author-reported health system barriers and facilitators were extracted and mapped to the six WHO health system building-blocks and an additional non-health systems ‘other’ block, to enable a comprehensive health system perspective.7 Two reviewers (GTN, NM) independently assessed the quality of each included article, using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses.8 9 Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

bmjpo-2024-002556supp002.pdf (81.4KB, pdf)

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was conducted by classifying barriers and facilitators using descriptive codes, then grouping these codes into broader categories or themes. We descriptively analysed and generated frequency plots, maps and tables for the following characteristics: year of publication, geographic distribution of studies, NCD classifications, continuum-of-care component (ie, prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment, palliative care and survivorship) and frequency of barriers and facilitators within each health system building-block.

Patient and public involvement

We did not involve patients or the public in the design, conduct or reporting of this study.

Results

Study characteristics

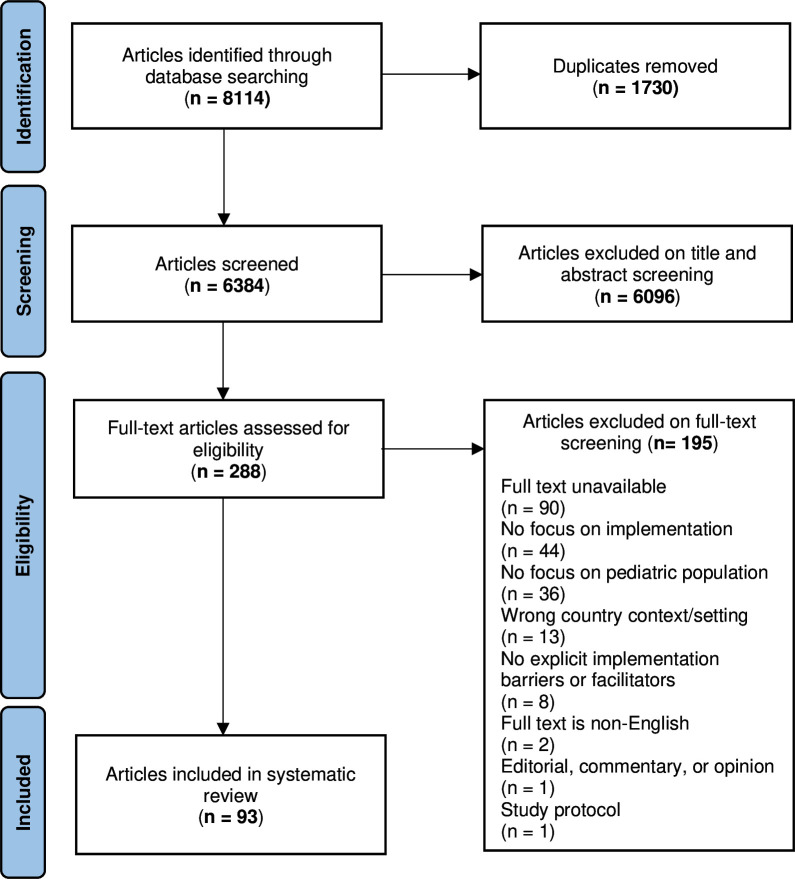

Our search yielded 6384 unique articles, 93 meeting full inclusion criteria (figure 1). There were 67 qualitative (72%), 18 mixed method (19%), 3 quantitative (3%) and 5 informal review studies (5%). Of the five review studies, four were of ‘moderate’ quality and one was of ‘low’ quality. Of the other 88 studies, most were of ‘high’ (n=49; 56%) and ‘moderate’ quality (n=36; 41%), with only two studies being rated as ‘low’ quality (2%). Details of quality assessment can be found in online supplemental appendix C.

Figure 1.

Selection process for literature inclusion.

bmjpo-2024-002556supp003.pdf (114.5KB, pdf)

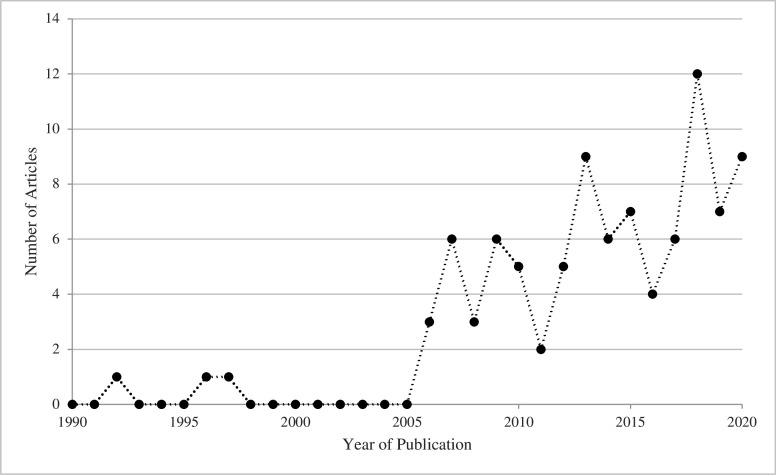

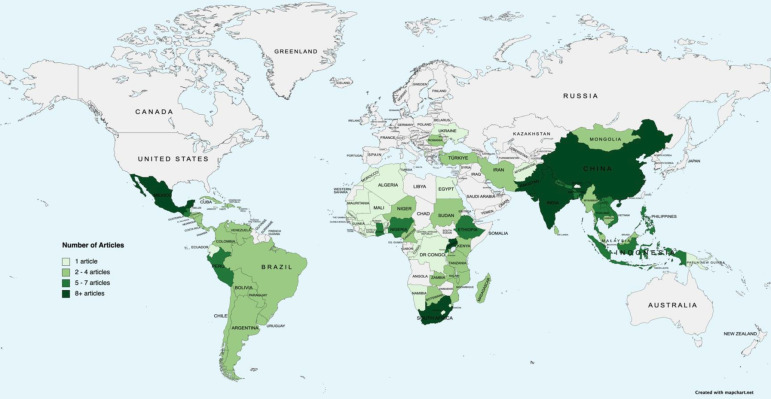

Articles were published between 1992 and 2020, exhibiting a notable increase in publications after 2005 (figure 2). 73 articles (78%) reported on a single country and 20 (22%) reported on multiple. Our sample represents 86 of 137 LMICs (figure 3).6

Figure 2.

Year of publication.

Figure 3.

Geographic distribution of articles.

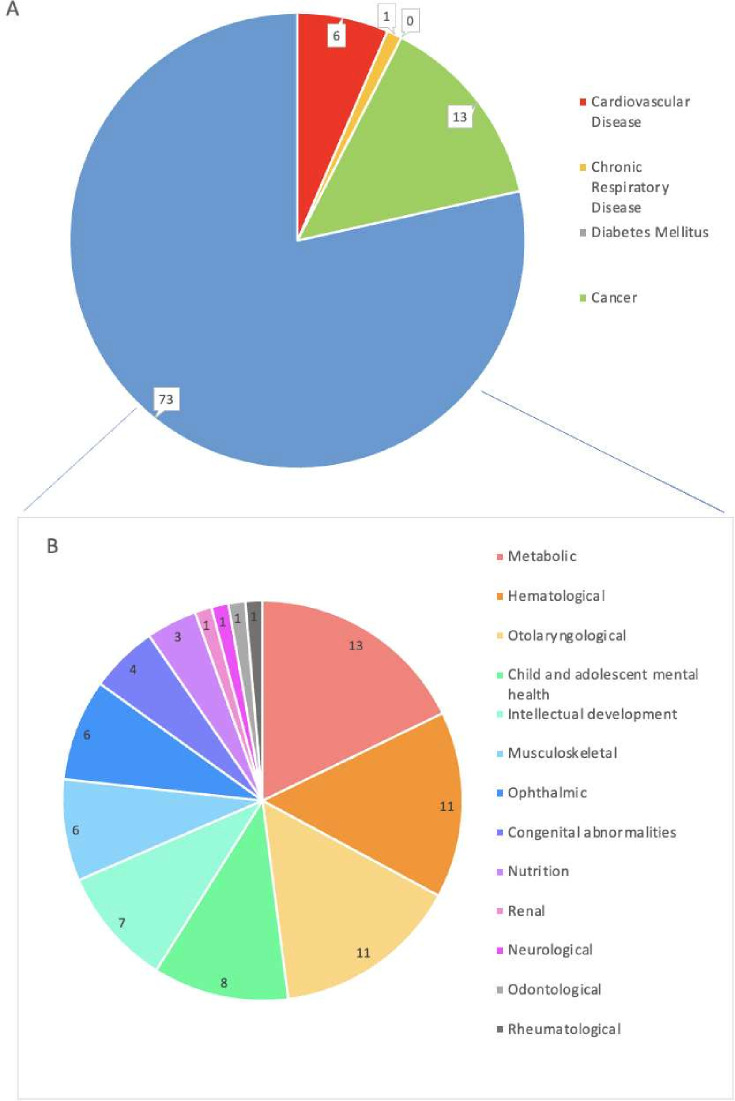

Notably, 78% (n=73) of articles reported on paediatric NCDs in the ‘other’ category, outside the four principal disease classifications (figure 4). Of these, the most prevalent conditions included metabolic disorders (n=13; 14%), such as inborn errors of metabolism, congenital thyroid disorders and obesity; haematological disorders (n=11; 12%), primarily sickle cell disease and trait, anaemia and haemophilia and otolaryngological conditions (n=11; 12%), principally congenital or childhood-acquired hearing loss. Within the 4 principal classifications, 13 pertained to cancer (14%), 6 to cardiovascular disease (6%), 1 to chronic respiratory disease (1%) and none to diabetes mellitus (0%).

Figure 4.

Non-communicable disease (NCD) classifications. (A) Classification by WHO’s main four NCDs framework; cardiovascular disease (n=6), chronic respiratory disease (n=1), diabetes mellitus (n=0), cancer (n=13) and others (n=73). (B) Classification of NCDs not encompassed by the framework; metabolic (n=13), haematological (n=11), otolaryngological (n=11), child and adolescent mental health (n=8), intellectual development (n=7), musculoskeletal (n=6), ophthalmic (n=6), congenital abnormalities (n=4), nutrition-related (n=3), renal (n=1), neurological (n=1), odonatological (n=1) and rheumatological conditions (n=1).

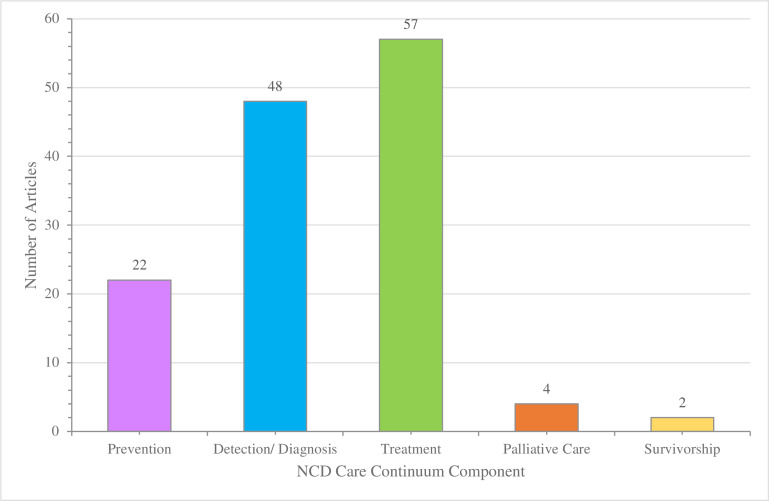

Most articles reported on a policy or programme addressing a single care continuum component (n=67; 72%), with a high prevalence involving prevention (n=23; 24%), detection and diagnosis (n=47; 51%) and treatment (n=57; 61%) (figure 5). Specific to cancer, palliative care and survivorship were addressed in four and two articles, respectively.

Figure 5.

Components of care continuum represented in studies. NCD, non-communicable disease.

Study characteristics of included articles are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Country | NCD | Care continuum component |

| Abalo et al 102 | Cuba | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Abbo et al 67 | Uganda | Nodding syndrome, epilepsy | Treatment |

| Abu-Osba et al 100 | Saudi Arabia | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Akilan et al 28 | India | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Akintayo et al 63 | Nigeria | Clubfoot | Treatment |

| Akol et al 16 | Uganda | Mental health, neuropsychiatric illness | Prevention |

| Al-Jurayyan et al92 | Saudi Arabia | Congenital hypothyroidism | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Andersen et al 77 | Botswana | Eye health | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Anie et al 42 | Ghana | Sickle cell disease/trait | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Atiim et al 57 | Ghana | Food allergy | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Barboza-Arguello et al 47 | Costa Rica | Neural tube defects | Treatment |

| Berry et al 45 | India | Anaemia | Prevention |

| Bingoler Pekcici et al 32 | Turkey | Developmental disorders | Treatment |

| Borrajo12 | Multiple | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Brewer et al 84 | Peru | Anaemia | Treatment |

| Bussé et al 29 | Albania | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Calderón-Colmenero et al 99 | Mexico | Cardiovascular disease | Treatment |

| Calderón-Colmenero98 | Mexico | Cardiovascular disease | Treatment |

| Coker-Bolt et al 69 | Ethiopia | Physical disability | Treatment |

| Dearani et al 48 | Multiple | Cardiovascular disease | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| De Garcia et al 70 | Multiple | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Denburg et al 93 | Multiple | Cancer | Treatment |

| Denburg et al 10 | Multiple | Cancer | Treatment, palliative care, survivorship |

| Dhillon et al 81 | Multiple | Anaemia | Treatment |

| Diez-Canseco et al 46 | Peru | Multiple | Prevention |

| Dvorak et al 54 | Mauritius | Multiple | Prevention |

| Edefonti et al 40 | Nicaragua | Renal disease | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Ekeroma et al 49 | Multiple | Cancer | Prevention, treatment, palliative care |

| Ertem et al 87 | Turkey | Developmental disorders | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Ford-Powell et al 65 | Bangladesh | Clubfoot | Treatment |

| Franz et al 79 | South Africa | Autism spectrum disorder | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Ghodsi et al 80 | Iran | Malnutrition | Treatment |

| Gladstone et al 83 | Malawi | Visual impairment | Treatment |

| Gordillo et al 72 | Peru | Retinopathy of prematurity | Prevention |

| Gregersen et al 11 | South Africa | Multiple | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Hailu et al 50 | Ethiopia | Cancer | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment, palliative care, survivorship |

| Hamdani et al 51 | Pakistan | Developmental disorders | Treatment |

| Hamdan et al 96 | Multiple | Anaemia | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Hariharan et al 94 | Argentina | Retinopathy of prematurity | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Harpham and Tuan60 | Vietnam | Mental health | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Hatam et al 30 | Iran | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Hill et al 41 | Kenya | Cancer | Treatment |

| Hobday et al 73 | Timor-Leste | Eye health | Prevention |

| Hockenberry et al 91 | Multiple | Cancer | Treatment |

| Hoehn et al 85 | The People’s Democratic Republic of Laos | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Howard et al 97 | Multiple | Cancer | Treatment |

| Khan et al 38 | Pakistan | Hearing loss | Treatment |

| Khapre et al 58 | India | Anaemia | Treatment |

| Khneisser et al 90 | Lebanon | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Kleintjes et al 25 | Multiple | Mental health | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Krotoski et al 78 | Multiple | Congenital hypothyroidism | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Kutcher et al 19 | Multiple | Mental health | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Larrandaburu et al 20 | Uruguay | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Leong et al 59 | Malaysia | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Martin et al 44 | Peurto Rico | Chronic respiratory disease | Treatment |

| McElroy et al 27 | Uganda | Clubfoot | Treatment |

| McKay et al 52 | Uganda | Mental health | Treatment |

| McLean et al 43 | Rwanda | Anaemia | Prevention, treatment |

| Mokitimi et al 86 | South Africa | Mental health | Prevention |

| Moodley et al 101 | South Africa | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Mugomeri37 | Lesotho | Nutritional deficiency | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Mumtaz et al 61 | Pakistan | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Okonta and Tobin-West74 | Nigeria | Cardiovascular disease | Treatment |

| Olusanya and Okolo et al 33 | Multiple | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Olusanya et al 53 | Multiple | Hearing loss | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Orem and Wabinga et al 56 | Uganda | Cancer | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Owen et al 68 | Multiple | Clubfoot | Treatment |

| Padilla35 | Multiple | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Padilla and Therrell et al 23 | Multiple | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Padilla and Therrell et al 62 | Multiple | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis |

| Park et al 24 | The People’s Democratic Republic of Laos | Cancer | Treatment |

| Pasco et al 89 | Romania | Autism spectrum disorder | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Penny et al 34 | Uganda | Chronic orthopaedic disabilities | Treatment |

| Picolo et al 82 | Mozambique | Nutritional deficiency | Prevention |

| Pillay and Lockhat et al 55 | South Africa | Mental health | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Poon and Luke et al 36 | China | Haemophilia | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Prathanee et al 26 | Thailand | Speech and language complications postcleft palate surgery | Treatment |

| Regmi and Wyber et al 88 | Nepal | Cardiovascular disease | Treatment |

| Roche et al 13 | Indonesia | Anaemia | Prevention |

| Shulman et al 39 | Rwanda | Cancer | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Shung-King et al 18 | South Africa | Multiple | Prevention, detection/diagnosis |

| Slone et al 75 | Botswana | Cancer | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Sukati et al 15 | Eswatini | Eye health | Prevention, detection/diagnosis, treatment |

| Sulafa71 | Sudan | Cardiovascular disease | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Tapela et al 66 | Rwanda | Cancer | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment, palliative care |

| Tekola-Ayele and Rotimi76 | Multiple | Multiple | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Tekola et al 21 | Ethiopia | Developmental disorders | Treatment |

| Treadwell et al 31 | Ghana | Sickle cell disease/trait | Treatment |

| Vichayanrat et al 14 | Thailand | Dental health | Prevention |

| Whitman et al 64 | China | Mental health | Prevention |

| Wilimas et al 22 | Multiple | Cancer | Treatment |

| Zepeda-Romero and Gilbert et al 17 | Mexico | Retinopathy of prematurity | Detection/Diagnosis, treatment |

| Zhang et al 95 | China | Multiple | Treatment |

NCD, non-communicable disease.

Implementation factors by health system building-block

Themes in barriers and facilitators are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Implementation barriers and facilitators by health system building-block

| Barriers | Facilitators | |

|

Health service delivery

A health system’s accessibility, continuity and comprehensiveness.7 |

System organisation and coordination | |

|

|

|

| Education and communication | ||

|

|

|

| Logistics and infrastructure | ||

|

|

|

|

Health workforce

The human resources engaged in the organisation and delivery of health services.7 |

Capacity utilisation and optimisation | |

|

|

|

| Qualification and training | ||

|

|

|

| Support and incentives | ||

|

|

|

|

Leadership and governance

The policy frameworks; oversight; coalition-building and regulation and accountability processes within a health system.7 |

Planning and priority setting | |

|

|

|

| Policy development | ||

|

|

|

| Stakeholder relationships | ||

|

|

|

|

Financing

The mobilisation, accumulation and allocation of financial resources to maintain and improve population health coverage.7 |

Funding streams | |

|

|

|

| Financial and economic costs | ||

|

|

|

|

Health information systems

Systems that concern the generation, complication and analysis of data that is ultimately synthesised for use and communication.7 |

Surveillance | |

|

|

|

| Data dissemination and management | ||

|

|

|

|

Access to essential medicines

A health system’s procurement process, supply and distribution management and regulatory control of essential therapies, inclusive of medicines, vaccines and technologies.7 |

Procurement and supply chain management | |

|

|

|

| Distribution | ||

|

|

|

| Regulation | ||

|

|

|

|

Other

Non-health system insights to capture the environmental and societal interactions that influence paediatric health.2 |

Sociocultural influence | |

|

|

|

| Sociopolitical climate | ||

|

|

|

Refer to online supplemental appendix D for details and supporting references.

NCD, non-communicable disease.

bmjpo-2024-002556supp004.pdf (139KB, pdf)

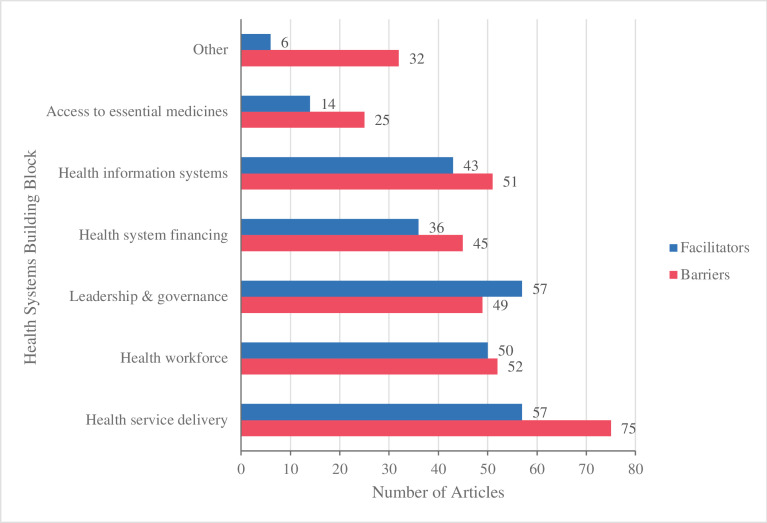

Health service delivery

Implementation factors related to health service delivery were most frequently reported (figure 6). Shortfalls in service delivery highlighted system fragmentation, service inaccessibility and inadequate public health education. Meanwhile, efforts to mitigate geographic disparities, addressing sociocultural factors and integration within existent services and facilities were key facilitators.

Figure 6.

Frequency of implementation barriers and facilitators across health system building-blocks.

System organisation and accessibility

Care continuity was commonly hindered by system fragmentation across healthcare tiers, and among specialties and service types.10–26 Authors emphasised the particular relevance of system fragmentation to paediatric NCDs, as children’s development necessitates age-specific services linked with transitioning services. Service inaccessibility was another frequently cited barrier, driven by geographic dispersion of patients from programme sites, routine centralisation of paediatric NCD services and inadequate public transportation infrastructure.18 19 23 27–37 These challenges have outsized bearing on paediatric NCD care, since service delivery is often concentrated at urban health facilities and consistent longitudinal follow-up essential to favourable long-term outcomes is needed.15 38 39 Challenges are amplified by childhood dependency on caregivers and the family unit. Studies reported family-level indirect care costs, with caregivers forced to compromise other responsibilities, including income generation, and out-of-pocket costs related to childcare or transportation for other dependents.27 29 40

Key facilitators included addressing sociocultural dimensions of healthcare to improve accessibility.10 13 14 19 21 22 24 24 26 41–54 An Indonesian national iron supplementation programme for adolescent females used formative interviews with them and key actors, such as parents and educators, to enhance the relevance of their awareness campaigns.13 A Ugandan rehabilitation programme for paediatric orthopaedic disorders established community-based rehabilitation hostels as stepdown units for rural populations, reducing travel distance and frequency while alleviating healthcare facility congestion.34

Education and communication

Inadequate public health education on NCDs impeded health-seeking behaviours and addressing stigma and misinformation, hindering uptake of implemented strategies.11 12 15 16 19 20 22 36 55–61 Reflecting Ghana’s lack of formalised policy on health promotion, public awareness of food allergy symptoms and risks was limited. Exacerbated by scepticism and misinformation perpetrated by cultural beliefs, paediatric cases were under-reported and addressed outside the formal medical system.57 Limited outreach communication to patients, caregivers and healthcare personnel also hindered uptake. Patients and caregivers remained unaware of available services, while healthcare personnel lacked the necessary information to offer recommendations and referrals.62–64

Logistics and infrastructure

Healthcare infrastructural constraints impeded the development of dedicated paediatric NCD facilities and their integration within facilities already grappling with overwhelming patient traffic and deteriorating sanitary environments.33 63 65–67 Limited or inconsistent supplies in poor and outdated conditions additionally constrained programme service delivery.15 17 22 29 50 57 68–72 Given the limited resources of LMICs, integration with existing paediatric services was advantageous. Nigeria and South Africa integrated newborn hearing screening within immunisation clinics and schedules, leveraging established credibility and enhanced compliance with convenient two-in-one scheduling, while facilitating cost-effectiveness.33

Health workforce

The deficits in specialty provider capacity limiting paediatric NCD strategies in LMICs were further exacerbated by poor staff delegation and weak sustainability of already limited capacity; obstacles to achieving pediatric-specific education and continued training and the lack of staff support and retention incentives.

Capacity utilisation and optimisation

Many initiatives lacked specialty-qualified or pediatrics-qualified personnel, contributing to healthcare fragmentation.10 15 16 25 26 31 35 51 66 67 70 71 73–79 In the Healthy Eyes in School initiative of Timor-Leste’s Alieu district, the presence of only one eye care technician from 2011 to 2014 created a referral bottleneck, limiting large-scale implementation.73 Systems with sufficient capacities were often compromised by poor staff retention or frequent rotation, perpetuating a cyclic need for recruitment and specialty training unconducive to programme sustainability.13 15 32 50 58 80 Poor staff allocation also resulted in inefficient use of skills; a paediatric cardiology programme in Sudan failed to use available echocardiogram technicians, sustaining dependence on physicians to conduct diagnostic testing.71 Task-shifting extended beyond the health sector was a facilitator in various community-based strategies.28 33 39 43 55 65 66 81 Non-medical tasks, such as information dissemination, were purposefully delegated to teachers and childcare personnel in a community-based hearing screening project implemented in the Tamil Nadu district of South India.28 Leveraging the community presence and familiarity of these workers facilitated acceptance and compliance while alleviating the burden on medical personnel. Community health workers (CHWs) were a valuable resource for task-shifting. Embedded in the community and having clinical training, they mitigated concerns about qualifications that often impede the acceptability of task-shifting.34 43 51 52 59 81–83

Qualification and training

Capacity limitations due to barriers in qualification and training were pronounced for paediatrics. The lack of domestic medical and specialty education compelled prospective trainees to pursue paediatrics programmes and employment in neighbouring regions or foreign countries.15 38 49 Furthermore, implementing innovations was often constrained by the limited number of staff who were supplementally trained to use new strategies in paediatric care.10 12 16 18–20 39 59 63 84 Uruguay’s development of comprehensive and universal care policies for congenital and rare NCDs highlighted the critical need to improve domestic health personnel training in the identification of congenital anomalies.20 Expert-knowledge gaps exacerbated frailties along the care continuum, as treatment-focused initiatives were constrained by limited capacity for detection and diagnosis of paediatric NCDs. Insufficient attention to knowledge retention, evidenced by lack of refresher training and feedback opportunities, created an additional barrier.12 14 18 24 26 29 31 57 58 67 77 83 85–88 Specific to community task-shifting, retention of teachers and CHWs was compromised as they were expected to implement novel responsibilities without standardised guidance and instruction.58

Significantly, adaptive and flexible delivery of training was a powerful facilitator of paediatric NCD programmes.11 13 14 16 24 26 31 34 41 48 50 71 72 75 82 87 89–92 Versatile platforms, such as tele-teaching or multimethod training (eg, onsite and offsite, and sessions by request), enhanced the feasibility of continuous training and broadened available training options.

Workforce support and incentives

Recruitment was limited by uncompetitive public sector salaries, which were routinely well below domestic and foreign private sector remuneration.15 17 24 32 49 50 77 Private-public compensation disparities resulted in limited recruitment and retention of childhood cancer providers in the Philippines’ public health sector.93 Additionally, reliance on volunteerism or low wages reduced workforce retention.32 51 94 Increased burden on the public paediatric workforce was identified as a downstream barrier to NCD programme implementation in a range of health systems. Staff shortages placed excessive burdens on a limited few, resulting in high patient-to-nurse ratios, which led to increased risk of medical errors and workforce burnout.15 18 46 56 58 59 63 67 73 80 91 Persistent lack of student interest in paediatric specialty training schemes, based on limited employment opportunities due to domestic underdevelopment of these specialties, was also an important barrier.26 50 This perpetuated a vicious cycle hindering the growth of paediatrics.

Leadership and governance

Health system leadership and governance emerged as decisive determinants of paediatric NCD policy implementation, underscoring the importance of political recognition and priority, paediatric policy specificity rather than umbrella NCD policies and the inclusion of a broad panoply of stakeholders in the implementation of policies and programmes.

Planning and priority setting

Successful implementation of paediatric NCD policies and programmes relies on sustained prioritisation within national health system planning cycles. In many LMICs undergoing epidemiological transition, NCD prioritisation is challenged with a persistent focus on communicable diseases.10–12 15 24 35 53 59 60 62 82 A key barrier was inadequate political visibility of paediatric NCDs, evidenced by lack of awareness among government officials regarding disease burden, of pediatric-focused policies and of supportive policies to facilitate the integration of paediatric programmes in health systems.10 14 15 17 19 24 26 32 35 42 49 50 56 61 62 67 68 74 75 78 79 82 83 89 95

Conversely, strategic framing of policies to align with current policy agendas facilitated prioritisation: they met less resistance, drew on existing momentum and leveraged stakeholders already invested in aligned policies and programmes.18 24 35 39 47 50 52 60 64 79 Policy windows were powerful facilitators of strategic alignment. A school-based programme promoting mental health among Chinese students was implemented in tandem with overarching government efforts to reform its education system.64 Finally, multiphase implementation of paediatric NCD policies, through pilot initiatives and evidence-based reporting of sequential phases, surfaced as a facilitator, enabling the timely identification of barriers, informing subsequent planning and offering increased opportunities for stakeholder input.43 44 54 69

Policy development

Lack of specificity in setting objectives was a barrier in programme and policy development.15 76 79 80 96 In 2005, Iran implemented a national programme to enhance paediatric nutrition in impoverished settings.80 Despite having a clear mission statement, it failed to implement successfully due to the absence of actionable protocols and to ambiguity in participant selection criteria, family socioeconomic status assessment and nutrition recovery indicators. This resulted in unwarranted exclusion of children, underscoring the necessity of designing paediatric-specific strategies rather than adopting pre-existing umbrella or adult frameworks and policies.

Stakeholder relationships

Health-promoting school programmes uniquely highlighted the multisectoral coordination required between the education and healthcare sectors to ensure feasible curriculum integration, appropriate training and sustainable allocation of responsibility.18 19 25 58 64 Local stakeholders often played a crucial role in sustainable implementation.20 21 42–44 48–50 52 60 65 69 81 94 97 The My Child Matters programme by the Sanofi Espoir Foundation recognised the synergistic and catalytic role of local non-governmental organisations that leverage pre-existing community acceptance and resources and that sustain domestic leadership, mitigating chronic dependence on external stakeholders.97 Moreover, community leaders, including religious and elder figures, facilitate culturally sensitive implementation, leveraging their heightened influence in LMICs and on paediatric social development.21 42 44 Inter-regional and international partnerships fostered policy community cohesion, in turn facilitating political advocacy and the sharing of high-level information and resources.10 23 24 32 36 38–41 48 49 71 75 76 78 90 91 93 97 Twinning partnerships with HICs were a prevalent approach to enhance paediatric NCD programmes in LMICs, facilitating increased awareness and mobilisation of supplemental resources and capacity.23 38–40 49 71 90 91 93

Financing

The chronicity and sequelae of paediatric NCDs highlights necessary but commonly unavailable funding for sustained programme implementation, including across developmental stages, in LMICs. A heavier family financial burden also exists, given recurrent user payments, larger family units and limited public insurance schemes. In health systems where private services are prevalent, provider concerns of non-profitability and reduced service uptake exist.

Funding streams

Limited public financing of paediatric NCD initiatives was frequently attributed to low political visibility and priority.10 13 16 22 38 50 53 59 61 63 78 80 82 93 95 Consequently, supplementary private funding, often from HICs and donor organisations, was commonly sought. However, funding flow was often inconsistent or limited to short-term agreements.13 16 22–24 40 41 43 44 53 54 68 97 98 At the clinical interface, out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure exacerbated inaccessibility in health systems reliant on user fees, especially for larger families.27 36 38 74 85 The lack of or limitations in coverage of public health insurance perpetuated this burden. Low-coverage schemes typically had limited inclusion of NCDs or specialised treatments, restricted availability to certain populations or had wide coverage but with low compensation.29 36 39 70 71 87 93 95 To this end, the Shanghai Children Hospital Care Aid was implemented to address the reluctance of commercial insurance companies and charitable organisations in China to cover costly treatments for critical paediatric diseases, including NCDs.95

Innovative strategies to enhance service affordability facilitated population accessibility, and programme and policy uptake.17 20 23 39 41 48 66 81 One example is the microfinance programme developed by the National Health Insurance Fund under Kenya’s national retinoblastoma strategy to improve paediatric outcomes. Caregivers of inpatients were taught to handmake and sell crafts, the profits of which were used to cover their health insurance premiums and additional treatment costs.41

Financial and economic costs

High costs, such as expensive upfront capital investments in diagnostic technologies, were a barrier for initial investments, profitability and sustainability of programmes.33 59 71 95 Newborn screening programmes in Latin America struggled to source screening tests as private suppliers were often concerned about poor profitability.12 Furthermore, the failure to determine programme cost-effectiveness deterred appropriate evaluation and design of pre-emptive strategies to decrease costs.12 20 39 Whether through the establishment of efficiency through cost-utility analyses or demonstration of profitability to stakeholders, dedicated efforts to generate investment demand was a financial facilitator to implementation.13 23 30

Health information systems

As a cross-cutting building-block, the underdevelopment of health information systems, demonstrated by poor surveillance and data management systems, contributed to political invisibility of paediatric NCDs and impeded effective service delivery.

Surveillance

The lack of established data systems for surveillance, through registries or epidemiological modelling, hampered political visibility and prioritisation of paediatric NCDs and was a contributing barrier to programme planning and delivery.11 20 39 47 49 60 61 75 81 82 93 98–100 A policy assessment of Pakistan’s public neonatal hearing screening determined a deficit of credible research on paediatric hearing impairment that limited policymaker awareness of the associated health and economic burdens.61 Limited data collection capability was a barrier to addressing such information gaps.10 13 16 24 37 53 57 62 70 81 82 99–101 Limitations were technical and infrastructural, for example, the absence of centralised data management systems, as well as resource-based, including inadequate human resource capacity or funding.10 55 78 80 101

Strong research capability served as a facilitator, mutually reinforcing surveillance efforts.39 41 56 67 This is exemplified by Uganda’s rich cancer research history, from which paediatric epidemiology justified and informed the incorporation of paediatric cancer priorities in the national cancer control programme.56 Data sharing, enabled by collaborative data-pooling networks and open information exchange among paediatric clinical and research groups, facilitated expansion of epidemiological information for LMICs struggling to develop domestic health information systems.13 40 44 48 56 62 98

Data dissemination and management

Existing information systems for paediatric NCDs were commonly compromised by poor management, evinced by inconsistent data completeness and accuracy, data loss during transfer and delayed error responses.15 19 29 43 47 65 66 80 99 Costa Rica’s implementation of its registry for congenital anomalies was challenged by participating hospitals submitting case reports in inconsistent formats, without verification and at erratic intervals.47 Conversely, pairing NCD information system development with mechanisms for oversight, and routine monitoring and evaluation facilitated quality assurance of data systems.48 60 68 73 76 81 89

Access to essential medicines

The included literature highlights a complex interplay of determinants impacting access to medicines for paediatric NCDs. Principal barriers include gaps in medicine availability and price variability conditioned by reactive procurement processes, reliance on foreign suppliers, weak supply management systems, poorly coordinated distribution and limited listing of paediatric NCD drug indications and formulations on national formularies.

Procurement and supply chain management

Paediatric NCD medicine availability across an array of diseases and systems was characterised by recurrent stockouts, and unreliable supply.10 15 27 38–40 56 58 67 71 75 80 81 88 Two dominant barriers were identified: the lack of domestic manufacturers and resulting reliance on importation, in which lengthy procurement times compromised quality and sustained availability; and inadequate storage systems that precipitated preventable product expiry and spoilage.43 45 81 88 By contrast, coordinated procurement strategies for private and public sourcing leveraged policy-backed resource allocation and lowered financial barriers through economies of scale.13 22 41 65 66 81 Proactive procurement processes, including those premised on evidence-based forecasting, mitigated shortages and helped stabilise prices in the context of relatively low demand for paediatric NCD drug indications.13 16 65 67 102

Distribution

The distribution of NCD medicines to paediatric facilities or programmes was sometimes compromised by inaccurate forecasting, discordance between supply duration and restocking intervals, insufficient allocation and non-standardised distribution.14 16 43 45 58 67 82 A school-based supplementation programme in India revealed that all participating schools had experienced stockout periods or expired products as distribution scheduling was misaligned with the school year, underscoring multisectoral coordination as a key facilitator of policy implementation.58

Regulation

Limited inclusion of paediatric indications and formulations of NCD medicines on national formularies and essential medication lists hampered reliable public sector access for children.10 16 A stakeholder forum on implementation considerations for national childhood cancer strategies in Latin America highlighted regulatory policies that constrained formulary inclusion of certain medicine formulations and devices, in the absence of overarching policy prioritisation of childhood cancers in national cancer control plans.10 Health technology regulation also created financial barriers to access, demonstrated by the mark-ups and taxes imposed on medical supplies by Ethiopia’s governmental agencies, which complicated supplying materials essential for the implementation of a paediatric physical and occupational therapy training programme.69

Other factors

Paediatric health and healthcare are heavily influenced by the environments and communities that children and youth interact with in their everyday lives. Sociocultural values, political instability and macroeconomic conditions were encompassing determinants of paediatric NCD policy and programme implementation.

Sociocultural influence

Inadequate caregiver support was a sociocultural barrier that hindered uptake and compliance with implemented strategies.21 27 31 34 80 84 Caregivers faced unshared financial burdens, challenges in acquiring childcare, overwhelming or competing parental responsibilities and misleading social interactions that discouraged health proactivity.21 27 34 63 84 The latter was heavily influenced by societal stigma.19 21 26 31 33 38 51 55 63 67 67 83 86

Sociopolitical climate

Political instability compromised health resources and services.23 55 59 71 80 90 Iran’s frequent administration turnovers with each presidential election introduced numerous political priority shifts that jeopardised the stability of paediatric NCD policies and programmes.80 Civil insecurities, such as risk of imminent war and electrical outages, also obstructed the implementation and accessibility of essential health services.55 90 Institutional distrust also surfaced as a barrier, as the uptake of some healthcare programmes was tainted by increasing prevalence of child sexual abuse or hindered by societal distrust in governments.31 35 55 59 67 84 Conversely, in the development of Shanghai’s national child health security system for critical diseases, analysis of existent insurance schemes identified periods of national stability and rapid economic development as advantageous economic windows for increased financing.95

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of paediatric NCD policies and programmes in LMICs to identify factors that promote or forestall their successful implementation. In the 93 studies, a wide range of paediatric conditions was represented, but disproportionately outside of the conventional adult NCD burden, highlighting the epidemiological differences and unique attendant health system considerations relevant to children and youth with NCDs. Synthesising our findings across the six WHO health-system building-blocks, we identified facilitators instrumental for policy and programme implementation, prominent among them appropriate consideration of sociocultural influences, comprehensive linking of care components, strategic alignment with broader policy agendas and multisectoral coordination, particularly with the education sector. Conversely, health system fragmentation—across tiers of care and between service settings—and lack of dedicated resource allocation to paediatric NCD management were common barriers, conditioned by weak evidence of paediatric NCD burden, corollary lack of sociopolitical visibility and resultant failure of political prioritisation. Notably, prominent barriers and facilitators across all health system domains highlight the unique diversity of stakeholders in paediatric NCD care, emphasising the influence of family, community and education systems on healthcare access for children and youth.

Previous reviews of NCDs in LMICs have focused on adults; in those that included children, we have not found any related to policy and programme implementation. A review by Jain et al examined a broad range of NCD interventions for school-aged children to assess their clinical but not implementation, effectiveness and only 12.5% of included studies were LMIC-based.103 Employing a health-system building-blocks framework, Heller et al reviewed the delivery of NCD care by non-physician health workers in LMICs, a programmatic facilitator identified in our review; however, their focus was not on children.104 Shah et al reviewed the delivery of NCD care to women and children in conflict zones. Although the included studies were based in LMICs, many of the insights identified were unique to conflict settings, limiting the relevance of their findings to policy and programme implementation for paediatric NCDs in LMIC health systems more generally.105

In both our study and in the general literature on paediatric NCDs in LMICs, we note an important gap in programmes and policies to address diabetes, a growing burden worldwide. This may relate to limited study of the incidence of type 1 diabetes in LMICs, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, resulting in lack of evidence for policy guidance.106

Our review underscores the relative neglect of paediatric NCDs in global NCD policy. The ‘4×4’ framework (four main NCDs of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases and cancers and four main modifiable risk factors of tobacco use, excessive alcohol use, unhealthy diets and physical inactivity) and its ‘5×5’ extension (including mental health and air pollution) have excluded diseases and issues pertinent to LMICs.107 The pervasiveness of this framing in policy agendas has poorly served children and youth in LMICs by relegating the majority of paediatric NCDs to a poorly specified category of ‘other’. It also ignores the fact that most paediatric NCDs are driven not by the causal and modifiable risk factors at play in adult NCDs, but by genetic, congenital and poorly understood environmental factors less amenable to behavioural risk reduction or prevention. The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission estimated that the NCD DALY loss per 1000 persons among those aged under 5 years in LMICs is greater than for the same age group in HICs and similar in those aged 5–19 years, and has recommended disaggregation of the maternal and child mortality targets to better address NCDs across health system contexts.108

The epidemiology, presentation and management of paediatric NCDs are distinct from those in adults and often age-specific, necessitating unique modes and patterns of engagement with healthcare systems. Different frameworks for paediatric NCD policy and programme implementation and evaluation are therefore required.2 The Paediatric Oncology System Integration Tool framework delineates the unique realities and programmatic requirements of childhood cancer care in a system-wide perspective, assessing cancer system performance through integrated consideration of the health workforce, infrastructure, medicines and technologies and supportive services.109 Comparable heuristics for other paediatric NCDs will help develop and evaluate evidence-informed policies and programmes for children and youth in LMICs.

The prevalence of school-based programming and policies in our review highlights the education sector as a critical health system extension for the paediatric population.110 However, in the least-developed countries, approximately 81% of children do not attend early childhood education.110 Students in LMICs are also disproportionately impacted by civil insecurity, as demonstrated by the average of 4 months of disrupted schooling during the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic, in contrast to the average 6 weeks lost in HICs.111 Minimising attendance disruptions may have far-reaching impacts on health policy and programming.

School-based and community-based approaches in particular have contributed to successful child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) programming.2 This underscores mental health as a key multisectoral investment priority, given that CAMH is the most prevalent NCD among those under the age of 20.2 A UNICEF analysis reported that school-based interventions addressing anxiety, depression and suicide provide a return on investment of US$21.5 for every US$1 invested over 80 years.110 Yet, our review revealed only eight CAMH-focused studies, pointing to stigma, lack of epidemiological evidence and a scarcity of mental health researchers and providers in LMICs.110 The need to increase visibility for mental health underscores leadership and governance as a cross-cutting implementation factor, as invisibility hinders policy prioritisation and resource allocation.109

Strengths

This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review of the factors contributing to the success of paediatric NCD policies and programmes in LMICs. It provides much-needed evidence to inform a life-course approach to addressing the growing strain of NCDs in low-resource settings. With its wide geographic span, our review reports on strategies that provide a representative view of implementation considerations in low-resource health systems. Our study benefited from a structured system-wide lens, particularly needed to capture the intersectoral determinants of NCDs and the wider ecosystem of NCD healthcare particular to children and youth.

Limitations

Our review is limited by the inclusion of English-only articles. We may have missed country-specific data contained in locally published, non-English journals. We also acknowledge the potential loss of valuable proximal insights of LMIC-based collaborators. However, our review includes studies conducted by authors and teams based in LMICs, ensuring local perspectives are incorporated. Moreover, in excluding literature on injuries, we may have missed emerging and pertinent information.

The WHO building-blocks framework offers a useful skeleton with which to map complex health systems; however, implementation challenges rarely manifest themselves in clear-cut blocks. Consequently, classification of barriers and facilitators was subjective, and their categorisation may have varied for articles where settings were not explicit. Inter-related or cross-cutting themes may also have been constrained by this framework. However, we deliberately identified boundary interactions across blocks to overcome overcompartmentalisation.

Conclusion

The implementation of NCD policies and programmes for children and youth face a multitude of barriers in LMICs across all aspects of the health sector. Yet, key facilitators identified offer an opportunity to advance our understanding of effective NCD policy and programme implementation among paediatric populations. Future implementation research focused on specific policies and programmes is recommended to further discern which factors have the most consequential impact within differing local contexts. Moreover, given the paediatric NCD burden in LMICs, future studies may strive to improve research coverage for countries not included in the current study and for understudied impacts on childhood development.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation and design: AD, GTN, NM, CG, LW, BW, JN, KP. Data screening: NM, LW, BW, JN, GTN, KP. Data analysis and interpretation: GTN, CG, AD. Manuscript writing: GTN, CG, KP, AD. Guarantor: AD.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Full extracted datasets are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Non communicable diseases. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases [Accessed 24 Apr 2024].

- 2. NCD Child . Children & non-communicable disease: global burden report 2019. Available: https://www.ncdchild.org/2019/01/28/children-non-communicable-disease-global-burden-report-2019/ [Accessed 31 May 2023].

- 3. UNICEF DATA . Non-communicable diseases. Available: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-health/noncommunicable-diseases/ [Accessed 31 May 2023].

- 4. Akseer N, Mehta S, Wigle J, et al. Non-communicable diseases among adolescents: current status, determinants, interventions and policies. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1908. 10.1186/s12889-020-09988-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Bank Data Help Desk . World Bank country and lending groups. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [Accessed 17 Apr 2023].

- 7. World Health Organization . Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258734 [accessed 17 Apr 2023] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Department of Family Medicine . Mixed methods appraisal tool. Available: https://www.mcgill.ca/familymed/research/projects/mmat [Accessed 31 May 2023].

- 9. JBI . JBI’s tools assess trust, relevance & results of published papers: enhancing evidence synthesis. Available: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools [Accessed 31 May 2023].

- 10. Denburg A, Wilson MG, Johnson SI, et al. Advancing the development of national childhood cancer care strategies in Latin America (2599). J Cancer Policy 2017;12:7–15. 10.1016/j.jcpo.2016.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gregersen N, Lampret J, Lane T, et al. The greater Sekhukhune-CAPABILITY outreach project (6996). J Community Genet 2013;4:335–41. 10.1007/s12687-013-0149-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Borrajo GJC. Newborn screening in Latin America at the beginning of the 21st century. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007;30:466–81. 10.1007/s10545-007-0669-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roche ML, Bury L, Yusadiredja IN, et al. Adolescent girls’ nutrition and prevention of anaemia: a school based multisectoral collaboration in Indonesia. BMJ 2018;363:k4541. 10.1136/bmj.k4541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vichayanrat T, Steckler A, Tanasugarn C. Barriers and facilitating factors among lay health workers and primary care providers to promote children’s oral health in Chon Buri province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2013;44:332–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sukati VN, Moodley VR, Mashige KP. A situational analysis of eye care services in Swaziland. J Public Health Afr 2018;9:892. 10.4081/jphia.2018.892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Akol A, Engebretsen IMS, Skylstad V, et al. Health managers’ views on the status of national and decentralized health systems for child and adolescent mental health in Uganda: a qualitative study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2015;9:54. 10.1186/s13034-015-0086-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zepeda-Romero LC, Gilbert C. Limitations in ROP programs in 32 neonatal intensive care units in five States in Mexico. BioMed Research International 2015;2015:1–8. 10.1155/2015/712624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shung-King M. From 'stepchild of primary healthcare' to priority programme: lessons for the implementation of the National integrated school health policy in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2013;103:895–8. 10.7196/samj.7550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kutcher S, Perkins K, Gilberds H, et al. Creating evidence-based youth mental health policy in sub-Saharan Africa: a description of the integrated approach to addressing the issue of youth depression in Malawi and Tanzania. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:542. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larrandaburu M, Matte U, Noble A, et al. Ethics, genetics and public policies in Uruguay: newborn and infant screening as a paradigm. J Community Genet 2015;6:241–9. 10.1007/s12687-015-0236-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tekola B, Girma F, Kinfe M, et al. Adapting and pre-testing the World Health Organization’s caregiver skills training programme for autism and other developmental disorders in a very low-resource setting: findings from Ethiopia. Autism 2020;24:51–63. 10.1177/1362361319848532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilimas JA, Wilson MW, Haik BG, et al. Development of retinoblastoma programs in Central America. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:42–6. 10.1002/pbc.21984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Padilla CD, Therrell BL. Newborn screening in the Asia Pacific region. J Inherit Metab Dis 2007;30:490–506. 10.1007/s10545-007-0687-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Park KD, Hong CR, Choi JY, et al. Foundation of pediatric cancer treatment in Lao people’s democratic republic at the Lao-Korea National children’s hospital. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2018;35:268–75. 10.1080/08880018.2018.1477888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kleintjes S, Lund C, Flisher AJ. A Situational analysis of child and adolescent mental health services in Ghana, Uganda, South Africa and Zambia. Afr J Psych 2010;13. 10.4314/ajpsy.v13i2.54360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prathanee B, Dechongkit S, Manochiopinig S. Development of community-based speech therapy model: for children with cleft lip/palate in northeast Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai 2006;89:500–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McElroy T, Konde-Lule J, Neema S, et al. Understanding the barriers to Clubfoot treatment adherence in Uganda: a rapid ethnographic study. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:845–55. 10.1080/09638280701240102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akilan R, Vidya R, Roopa N. Perception of 'mothers of beneficiaries' regarding a rural community based hearing screening service. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2014;78:2083–8. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bussé AML, Qirjazi B, Goedegebure A, et al. Implementation of a neonatal hearing screening programme in three provinces in Albania. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;134:110039. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hatam N, Askarian M, Bastani P, et al. Cost-utility of screening program for neonatal hypothyroidism in Iran. Shiraz E-Med J 2016;17:e33606. 10.17795/semj33606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Treadwell MJ, Anie KA, Grant AM, et al. Using formative research to develop a counselor training program for newborn screening in Ghana. J Genet Couns 2015;24:267–77. 10.1007/s10897-014-9759-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bingoler Pekcici EB, Özalp Akin E, Ayranci Sucakli I, et al. Addressing early childhood development and developmental difficulties in Turkey: a training programfor developmental pediatrics units. Arch Argent Pediatr 2020;118:e384–91. 10.5546/aap.2020.eng.e384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olusanya BO, Okolo AA. Early hearing detection at immunization clinics in developing countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006;70:1495–8. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Penny N, Zulianello R, Dreise M, et al. Community-based rehabilitation and orthopaedic surgery for children with motor impairment in an African context. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:839–43. 10.1080/09638280701240052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Padilla CD. Towards universal newborn screening in developing countries: obstacles and the way forward. Ann Acad Med Singap 2008;37:6–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Poon M-C, Luke K-H. Haemophilia care in China: achievements of a decade of world Federation of hemophilia treatment centre twinning activities. Haemophilia 2008;14:879–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2008.01821.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mugomeri E. Identifying Imperatives for an effective nutrition surveillance policy framework for maternal and child health in Lesotho. Food Nutr Bull 2018;39:608–20. 10.1177/0379572118806708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Khan MIJ, Mukhtar N, Saeed SR, et al. The Pakistan (Lahore) cochlear implant programme: issues relating to implantation in a developing country. J Laryngol Otol 2007;121:745–50. 10.1017/S0022215107007463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shulman LN, Mpunga T, Tapela N, et al. Bringing cancer care to the poor: experiences from Rwanda. Nat Rev Cancer 2014;14:815–21. 10.1038/nrc3848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Edefonti A, Marra G, Castellón Perez M, et al. A comprehensive cooperative project for children with renal diseases in Nicaragua. Clin Nephrol 2010;74 Suppl 1:S119–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hill JA, Kimani K, White A, et al. Achieving optimal cancer outcomes in East Africa through multidisciplinary partnership: a case study of the Kenyan national retinoblastoma strategy group. Global Health 2016;12:23. 10.1186/s12992-016-0160-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anie KA, Treadwell MJ, Grant AM, et al. Community engagement to inform the development of a sickle cell counselor training and certification program in Ghana. J Community Genet 2016;7:195–202. 10.1007/s12687-016-0267-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLean J, Northrup-Lyons M, Reid RJ, et al. From evidence to national scale: an implementation framework for micronutrient powders in Rwanda. Matern Child Nutr 2019;15:e12752. 10.1111/mcn.12752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Martin CG, Andrade AA, Vila D, et al. The development of a community-based family asthma management intervention for Puerto Rican children. Cpr 2010;4:315–24. 10.1353/cpr.2010.a406087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Berry J, Mehta S, Mukherjee P, et al. Implementation and effects of India’s National school-based iron supplementation program. J Dev Econ 2020;144:102428. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.102428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Diez-Canseco F, Boeren Y, Quispe R, et al. Engagement of adolescents in a health communications program to prevent noncommunicable diseases: multiplicadores Jovenes, Lima, Peru, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2015;12:E28. 10.5888/pcd12.140416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Barboza-Argüello M de la P, Umaña-Solís LM, Azofeifa A, et al. Neural tube defects in Costa Rica, 1987-2012: origins and development of birth defect surveillance and folic acid fortification. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:583–90. 10.1007/s10995-014-1542-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dearani JA, Neirotti R, Kohnke EJ, et al. Improving pediatric cardiac surgical care in developing countries: matching resources to needs. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu 2010;13:35–43. 10.1053/j.pcsu.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ekeroma A, Dyer R, Palafox N, et al. Cancer management in the pacific region: a report on innovation and good practice. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:e493–502. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30414-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hailu D, Adamu H, Fufa D, et al. Training pediatric hematologists / oncologists for capacity building in Ethiopia. Blood 2019;134:3423. 10.1182/blood-2019-121796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hamdani SU, Atif N, Tariq M, et al. Family networks to improve outcomes in children with intellectual and developmental disorders: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst 2014;8:7. 10.1186/1752-4458-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McKay MM, Sensoy Bahar O, Ssewamala FM. Implementation science in global health settings: collaborating with governmental & community partners in Uganda. Psychiatry Research 2020;283:112585. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Olusanya BO, Swanepoel DW, Chapchap MJ, et al. Progress towards early detection services for infants with hearing loss in developing countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:14. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dvorak J, Fuller CW, Junge A. Planning and implementing a nationwide football-based health-education programme. Br J Sports Med 2012;46:6–10. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pillay AL, Lockhat MR. Developing community mental health services for children in South Africa. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1493–501. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00079-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Orem J, Wabinga H. The roles of national cancer research institutions in evolving a comprehensive cancer control program in a developing country: experience from Uganda. Oncology 2009;77:272–80. 10.1159/000259258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Atiim GA, Elliott SJ, Clarke AE, et al. 'What the mind does not know, the eyes do not see'. Placing food allergy risk in sub-Saharan Africa. Health & Place 2018;51:125–35. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Khapre M, Shewade HD, Kishore S, et al. Understanding barriers in implementation and scaling up WIFS from providers perspective: a mixed-method study. J Family Med Prim Care 2020;9:1497. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1014_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Leong YH, Gan CY, Tan MAF, et al. Present status and future concerns of expanded newborn screening in Malaysia: sustainability, challenges and perspectives. MJMS 2014;21:64–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Harpham T, Tuan T. From research evidence to policy: mental health care in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84:664–8. 10.2471/BLT.05.027789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mumtaz N, Babur MN, Saqulain G. Multi-level barriers & priorities accorded by policy makers for neonatal hearing screening (NHS) in Pakistan: a thematic analysis 5106. Pak J Med Sci 2019;35:1674–9. 10.12669/pjms.35.6.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Padilla CD, Therrell BL, Working Group of the Asia Pacific Society for Human Genetics on Consolidating Newborn Screening Efforts in the Asia Pacific Region . Consolidating newborn screening efforts in the Asia Pacific region: networking and shared education. J Community Genet 2012;3:35–45. 10.1007/s12687-011-0076-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Akintayo OA, Adegbehingbe O, Cook T, et al. Initial program evaluation of the Ponseti method in Nigeria. Iowa Orthop J 2012;32:141–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Whitman CV, Aldinger C, Zhang X-W, et al. Strategies to address mental health through schools with examples from China. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008;20:237–49. 10.1080/09540260801994649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ford-Powell VA, Barker S, Khan MSI, et al. The Bangladesh Clubfoot project: the first 5000 feet. J Pediatr Orthop 2013;33:e40–4. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318279c61d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tapela NM, Mpunga T, Hedt-Gauthier B, et al. Pursuing equity in cancer care: implementation, challenges and preliminary findings of a public cancer referral center in rural Rwanda. BMC Cancer 2016;16:237. 10.1186/s12885-016-2256-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Abbo C, Mwaka AD, Opar BT, et al. Qualitative evaluation of the outcomes of care and treatment for children and adolescents with nodding syndrome and other epilepsies in Uganda. Infect Dis Poverty 2019;8:30. 10.1186/s40249-019-0540-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Owen RM, Penny JN, Mayo A, et al. A collaborative public health approach to Clubfoot intervention in 10 low-income and middle-income countries: 2-year outcomes and lessons learnt. J Pediatr Orthop B 2012;21:361–5. 10.1097/BPB.0b013e3283504006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Coker-Bolt P, DeLuca SC, Ramey SL. Training paediatric therapists to deliver constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) in sub-Saharan Africa. Occup Ther Int 2015;22:141–51. 10.1002/oti.1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. De Garcia BG, Gaffney C, Chacon S, et al. Overview of newborn hearing screening activities in Latin America. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica/Pan American Journal of Public Health 2011;29:145–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sulafa KMA. Paediatric cardiology programs in countries with limited resources: how to bridge the gap. J Saudi Heart Assoc 2010;22:137–41. 10.1016/j.jsha.2010.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gordillo L, Villanueva AM, Quinn GE. A practical method for reducing blindness due to retinopathy of prematurity in a developing country. J Perinat Med 2012;40:577–82. 10.1515/jpm-2011-0225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hobday K, Ramke J, du Toit R, et al. Healthy eyes in schools: an evaluation of a school and community-based intervention to promote eye health in rural Timor-Leste. Health Education Journal 2015;74:392–402. 10.1177/0017896914540896 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Okonta KE, Tobin-West CI. Challenges with the establishment of congenital cardiac surgery centers in Nigeria: survey of cardiothoracic surgeons and residents. J Surg Res 2016;202:177–81. 10.1016/j.jss.2015.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Slone JS, Slone AK, Wally O, et al. Establishing a pediatric hematology-oncology program in Botswana. J Glob Oncol 2018;4:1–9. 10.1200/JGO.17.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tekola-Ayele F, Rotimi CN. Translational genomics in low- and middle-income countries: opportunities and challenges. Public Health Genomics 2015;18:242–7. 10.1159/000433518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Andersen T, Jeremiah M, Thamane K, et al. Implementing a school vision screening program in Botswana using Smartphone technology. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:255–8. 10.1089/tmj.2018.0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Krotoski D, Namaste S, Raouf RK, et al. Conference report: second conference of the Middle East and North Africa newborn screening initiative: partnerships for sustainable newborn screening infrastructure and research opportunities. Genet Med 2009;11:663–8. 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ab2277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Franz L, Adewumi K, Chambers N, et al. Providing early detection and early intervention for autism spectrum disorder in South Africa: stakeholder perspectives from the Western Cape province. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2018;30:149–65. 10.2989/17280583.2018.1525386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ghodsi D, Omidvar N, Rashidian A, et al. Key informants’ perceptions on the implementation of a national program for improving nutritional status of children in Iran. Food Nutr Bull 2017;38:78–91. 10.1177/0379572116682870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nyhus Dhillon C, Sarkar D, Klemm RD, et al. Executive summary for the micronutrient powders consultation: lessons learned for operational guidance. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13 Suppl 1:e12493. 10.1111/mcn.12493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Picolo M, Barros I, Joyeux M, et al. Rethinking integrated nutrition-health strategies to address micronutrient deficiencies in children under five in Mozambique. Matern Child Nutr 2019;15 Suppl 1:e12721. 10.1111/mcn.12721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Gladstone M, McLinden M, Douglas G, et al. 'Maybe I will give some help…. maybe not to help the eyes but different help': an analysis of care and support of children with visual impairment in community settings in Malawi. Child Care Health Dev 2017;43:608–20. 10.1111/cch.12462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Brewer JD, Santos MP, Román K, et al. Micronutrient powder use in Arequipa, Peru: barriers and enablers across multiple levels. Matern Child Nutr 2020;16:e12915. 10.1111/mcn.12915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hoehn T, Lukacs Z, Stehn M, et al. Establishment of the first newborn screening program in the people’s Democratic Republic of Laos. J Trop Pediatr 2013;59:95–9. 10.1093/tropej/fms057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mokitimi S, Schneider M, de Vries PJ. Child and adolescent mental health policy in South Africa: history, current policy development and implementation, and policy analysis. Int J Ment Health Syst 2018;12:36. 10.1186/s13033-018-0213-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ertem IO, Pekcici EBB, Gok CG, et al. Addressing early childhood development in primary health care: experience from a middle-income country. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2009;30:319–26. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b0f035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Regmi PR, Wyber R. Prevention of rheumatic fever and heart disease: Nepalese experience. Glob Heart 2013;8:247–52. 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Pasco G, Clark B, Dragan I, et al. A training and development project to improve services and opportunities for social inclusion for children and young people with autism in Romania. Autism 2014;18:827–31. 10.1177/1362361314524642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]