Abstract

Background

Diverticulosis is a normal anatomical variant of the colon present in more than 70% of the westernized population over the age of 80. Approximately 3% will develop diverticulitis in their lifetime. Many patients present emergently, suffer high morbidity rates and require substantial healthcare resources. Diverticulosis is the most common finding at colonoscopy and has the potential for causing a significant morbidity rate and burden on healthcare. There is a need to better understand the aetiology and pathogenesis of diverticular disease. Research suggests a genetic susceptibility of 40–50% in the formation of diverticular disease. The aim of this review is to present the hypothesized functional effects of the identified gene loci and environmental factors.

Methods

A systematic literature review was performed using PubMed, MEDLINE and Embase. Medical subject headings terms used were: ‘diverticular disease, diverticulosis, diverticulitis, genomics, genetics and epigenetics’. A review of grey literature identified environmental factors.

Results

Of 995 articles identified, 59 articles met the inclusion criteria. Age, obesity and smoking are strongly associated environmental risk factors. Intrinsic factors of the colonic wall are associated with the presence of diverticula. Genetic pathways of interest and environmental risk factors were identified. The COLQ, FAM155A, PHGR1, ARHGAP15, S100A10, and TNFSF15 genes are the strongest candidates for further research.

Conclusion

There is increasing evidence to support the role of genomics in the spectrum of diverticular disease. Genomic, epigenetic and omic research with demographic context will help improve the understanding and management of this complex disease.

There is a need to better understand the aetiology and pathogenesis of diverticular disease. Research suggests a genetic susceptibility of 40–50% in the formation of diverticular disease, supported by further genome-wide association studies. The aim of this review is to present the hypothesized functional effects of the identified gene loci.

Introduction

Diverticular disease (DD) is a heterogenous disease of unknown molecular pathophysiological origin with increasing incidence and lack of an international unifying clinical management strategy. DD covers the spectrum of asymptomatic diverticulosis to complicated diverticulitis. Diverticulosis is a common anatomical variant found at colonoscopy in 15% of patients in their fifth decade of life and gradually increasing to 70% by the eighth decade1–3. Approximately 20% of patients with diverticulosis will develop symptomatic DD of which 15% will go on to develop diverticulitis within their lifetime4,5. DD is the most common gastrointestinal cause for emergency department visits and inpatient admission, creating a significant health economic burden6. Over the past decade an increase in the number of elective operations for diverticulitis reflects the rising incidence of DD in a younger patient cohort7. Across Europe, DD accounts for around 13 000 deaths per year8.

The current understanding of the genomic predisposition for diverticulitis is founded on epidemiological studies. These studies identified several risk factors including: age, sex, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, dietary factors, alcohol, smoking, medication, co-morbidities and location6,9–15. However, environmental factors have not been able to risk stratify patients for management or reduce the disease burden. Further studies are being undertaken to better understand the pathophysiology of DD and its molecular pathways to evaluate the strength of associated risk factors.

Approximately 50% of the cause of DD is due to genetic effects, such as Mendelian connective tissue disorders like Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, polycystic kidney disease, Marfan’s syndrome and Williams–Beuren syndrome16–18. The aetiological trigger for symptomatic diverticulitis in diverticulosis patients remains unknown. Understanding the risk factors, pathophysiology and genetic predisposition to diverticulitis are important to direct clinical management in symptomatic patients19,20. There is variation in the management of DD including traditional dietary recommendations, antibiotics, and elective colectomy, alternative surgical approaches having fallen in and out of vogue in the last decade21. Approximately 15% of patients with diverticulitis require surgery and these operations are predominantly performed under emergency conditions that may result in the formation of a colostomy. Emergency operations for diverticulitis have high morbidity and mortality rates (reported up to 30%), a significant impact on quality of life and potential reoperation for stoma reversal in appropriate patients22.

The increasing incidence of diverticulitis, attributed to westernized industrialization compounding individual and environmental risk factors, places a strain on healthcare systems that makes understanding the disease and identifying patients that will progress to complicated disease increasingly important8. Understanding the causative genomic and molecular pathways creates the potential to identify a biological profile to predict complicated diverticulitis, which requires higher acuity of care or preventative treatment strategies such as surgery. This systematic literature review details the known genomic and epigenetic factors related to the formation of diverticulosis, highlighting the pathways indicated in association with diverticulitis.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The title, methods and outcome measures were stipulated in advance and can be found in the Supplementary materials (Supp. S1). There was insufficient evidence to perform a diagnostic accuracy, methodological or prognostic systematic review, therefore, this study was not registered on PROSPERO (an international prospective register of systematic reviews). A systematic review was performed to map evidence of the topic, identify main concepts and knowledge gaps, and examine the evidence in question to aid the planning and commissioning of future research in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR checklist (Supplementary materials, Supp. S2)23.

Included studies

All papers including scientific evidence of colonic DD, epigenetics and human genetics were included with a focus on the genomics of inflammation and sepsis in diverticulitis. No regional restriction was placed. All study designs were considered for inclusion. Full-text papers available in the English language were included. Studies from 1972 up until the last search on 13 June 2023 were included.

Participants

All studies reporting patients with diverticulosis, DD or diverticulitis were included. Studies pertaining to ‘segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis’ (SCAD) were excluded. All degrees of disease severity were included. No age restriction was applied but the studies included mainly focused on adult participants. Animal studies were excluded.

Variables of interest

Genomics already known to be associated with DD in the literature were included, for example ARHGAP15, FAM155A, COLQ, and TNFSF15 as well as epigenetic or genetic changes associated with DD. The correlation between genetic/epigenetic changes and the presence or severity of DD was assessed.

Search strategy

The MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and Cochrane databases available through the National Health Service (NHS) National Library of Health website, the Cochrane library and PubMed available online were used. No time limit was placed on publication date. The last search was performed on 13 June 2023.

All titles containing the text and MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) search terms: ‘diverticular disease,’ ‘diverticulosis,’ ‘diverticulitis,’ ‘genomics,’ ‘genetics’ and ‘epigenetics’ were screened. Relevant papers identified in the database were included. Grey literature was searched using Google Scholar, personal communication, conference abstracts and abstract data. Full texts were reviewed, and quality was assessed by two independent reviewers. Studies relating to extra colonic diverticula were excluded. All relevant titles were then further screened by abstract. The full articles of eligible abstracts were then obtained. Bibliographies of the identified articles were manually screened for additional papers of interest. A PRISMA-ScR chart of the literature is shown (Supplementary materials, Supp. S2).

Study selection and data collection process

Each included article was reviewed by three researchers. For abstracts with ambiguous relevance, full texts were screened. Where more specific or missing data was required the authors of manuscripts were contacted. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and if no consensus could be reached the senior author would decide. Data was entered onto an Excel worksheet.

Data items and extraction

Appropriate scientific evidence on the genetics and epigenetics of DD was extracted. Patient demographics and study characteristics were extracted from the relevant studies. Evidence of good quality has been included for discussion in this article. Risk of bias and quality was discussed but was not able to be formally assessed due to the lack of studies available and inappropriateness of performing a quality assessment on too few studies.

Results

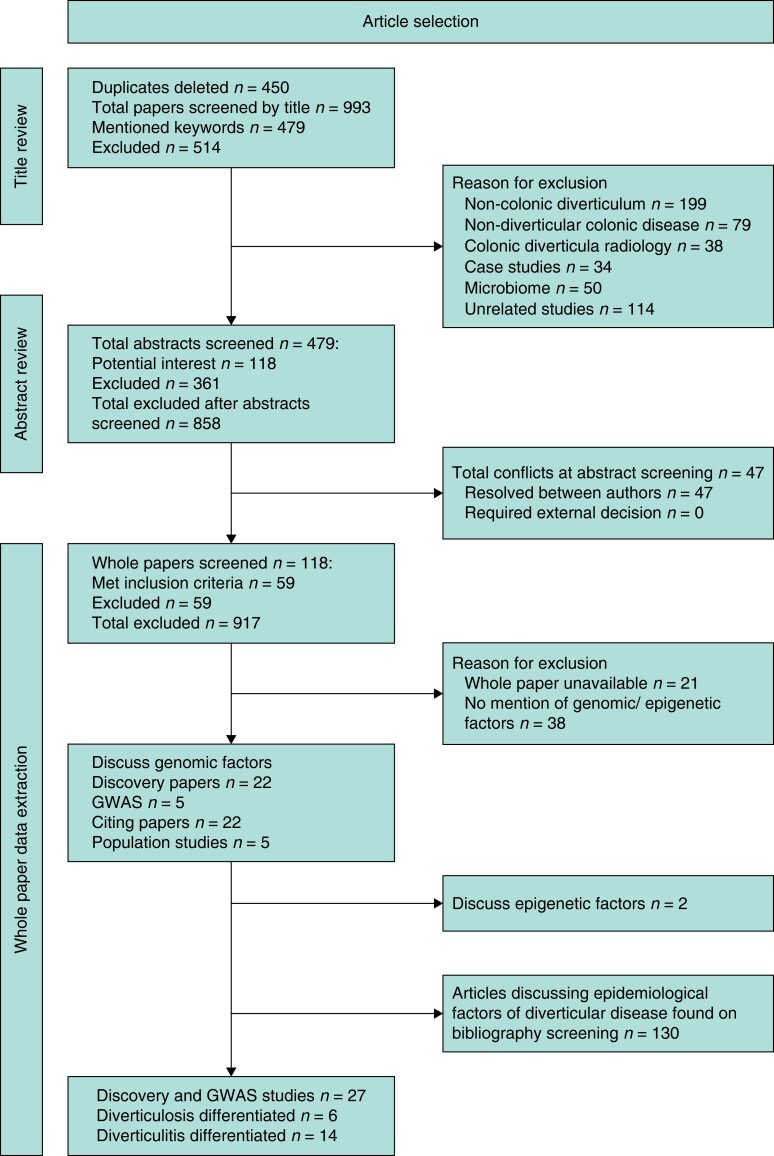

The search strategy identified 995 articles, excluding duplicates. After screening of titles and abstracts, 59 articles met the inclusion criteria for the study. A further 130 articles of interest were found on manual screening of the bibliographies relating to epidemiology of DD (Fig. 1). A total of 27 articles reported discovery studies of potential novel mutations associated with DD (Supplementary materials, Supp. S3).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram GWAS, genome-wide association studies.

The literature review included five genome-wide association studies (GWAS), five population studies, 22 discovery studies and 22 citing papers. The level of evidence for each study, location and study population demographics are described (Supplementary materials, Supp. S4, S5, S6)4.

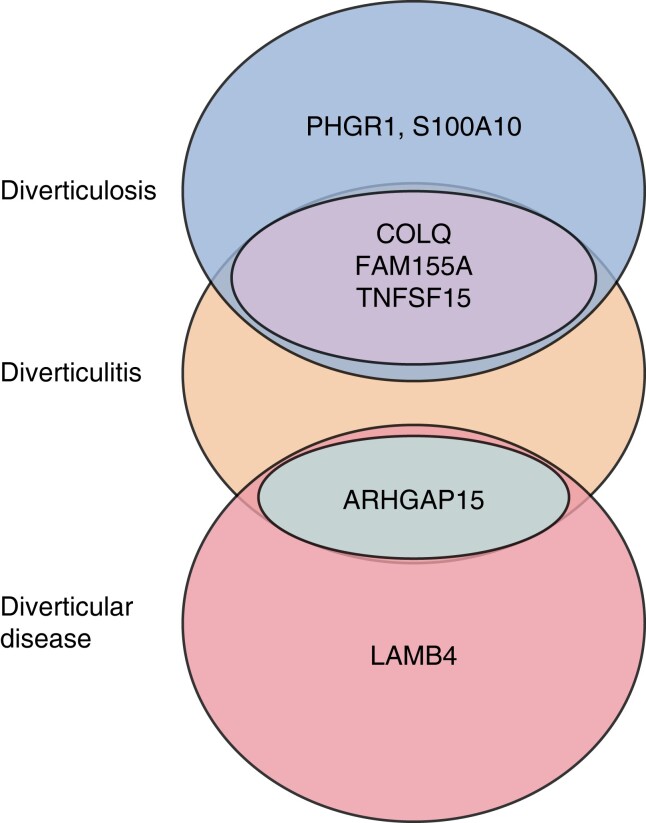

A total of 86 novel loci have been described, of which 31 have been replicated. Mutations in 18 loci have been associated with diverticulosis, and 25 related to diverticulitis specifically (Supplementary materials, Supp. S3). The most cited loci were ARHGAP15, COLQ, FAM155A, and TNFSF15. The loci with the strongest association with DD are ARHGAP15 and LAMB4. The loci with the strongest association with diverticulitis are COLQ, FAM155A, PHGR1, S100A10, and TNFSF15 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic overlap of genes with strongest association to diverticulosis, diverticulitis and diverticular disease

Molecular pathways involved in extracellular matrix, connective tissue formation, immunity, membrane transport, cell adhesion and intestinal motility have been proposed in the literature as potential causative physiology in the development of diverticulosis. Some mutations are associated with pathways within the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) system, wingless-related integration site (WNT) signalling pathway, OAS 1/3 (2' - 5' oligoadenylate synthetase) pathway and RHOU pathway, downstream phenotypic applications described (Supplementary materials, Supp. S6).

Two papers identified in this study, from the same authors, described epigenetic changes associated with DD24,25.

Epidemiology

Age and sex

DD has traditionally been considered a disease of older adults with a peak incidence over the age of 70. There has been a large increase in prevalence in the 18–40 age group in a European cohort noted since 2000, in which the incidence per 1000 population increased from 0.15 to 0.251 in only 7 years, with no change being described over this time interval for those over 657,8,10,26. In those over 50, DD has an equal prevalence between sexes. In the under 50 cohort, DD has a male predominance, with young males more likely to have aggressive disease, complications and higher risk of recurrence11,12. It is hypothesized that the prolonged time course of the bowel wall to insult, rather than age per se, increases the risk of diverticulosis. Caucasian Western patients have equal distribution between the sexes27,28. A Korean study showed an incidence by sex ratio of 2.2:1 male:female29.

It is reported that individuals with a family history of diverticulitis have a similar risk of recurrence when compared with those without a family history (HR 1.0; 95% c.i. 0.8 to 1.2) but are more likely to undergo elective surgery (HR 1.4; 95% c.i. 1.1 to 1.6). This was most notable in those with a first-degree family member affected by diverticulitis (HR 1.7; 95% c.i. 1.4 to 2.2)30.

Obesity and sedentary lifestyle

The relationship between body mass index (BMI) and diverticulosis has conflicting evidence13,14. A large prospective series linked an increased BMI to an elevated risk of diverticulitis31. However, other population studies have not replicated this and found no association between BMI and diverticulitis at colonoscopy4,32. Physical activity has a significant correlation with reducing complications of diverticulitis15–17.

Dietary factors

Studies attributing diverticulitis to low fibre, seeds and nuts have been disproved and no association has been supported17,18. The Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) comprising 51 000 US male health professionals found an inverse association between nut and popcorn consumption and the risk of diverticulitis with a reduction in the risk of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding33.

The recommended dietary fibre intake for adults is 20–35 g/day, which few achieve by those consuming a ‘westernized’ diet. The Vitamin D and Calcium Polyp Prevention Study did not find an association between fibre and diverticulosis at colonoscopy34,35. However, secondary analysis using the Diet and Health Study and the Healthcare Professional Follow Up Study found patients with the highest fibre intake were most likely to have symptomatic diverticular disease8,21,26. Conversely, the Oxford cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) consisting of 57 000 patients from the UK found a protective effect of a fibre-rich diet36. This finding is reinforced by data from the prospective Million Women Study from the UK, which observed a reduced incidence of DD on a high fibre diet37. However, this depends on the specific sources of fibre, with the lowest risk resulting from fruit consumption38. Vitamin D regulates intestinal proliferation and is important to maintain colonic homeostasis by modulating inflammation. A study demonstrated that low ultraviolet (UV) light exposure is associated with diverticulitis and higher levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are associated with a lower risk of diverticulitis39,40.

There is conflicting evidence around the association with red meat, alcohol and smoking14,19. The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study found that red meat consumption in a westernized diet was associated with increased risk of incident diverticulitis and the EPIC-Oxford Study found red meat eaters had a higher risk of hospitalization from diverticulitis than vegetarians36,41,42. The EPIC-Oxford study, a prospective cohort of 47 678 US men, 40–75 years old, also found that those who drink > 30 g of alcohol/day have a weak and non-significant association with symptomatic DD when compared with non-drinkers. It is acknowledged that due to the multifactorial and slow course of the disease it is hard to study lifestyle factors over the interval in which diverticula develop.

Co-morbidities

Hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus have been associated with asymptomatic diverticulosis20,21,43. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin is associated with diverticular bleeds22. Steroids and opiate use are suggested to increase the presence of diverticula1,44,45. Smoking has not been significantly associated with the presence of diverticula44,46,47. Several case reports linking familial syndromes to increased severity of DD support the hypothesis that collagen tissue abnormality plays a role in the pathophysiology of diverticulosis (Table 2). However, studies investigating ancestry present conflicting data about the increased prevalence of DD in individuals with a positive family history. Some studies do show that individuals with a strong family history are more likely to have surgical management for DD30,55,56 (see Table 1 for extrinsic factors related to DD).

Table 2.

Familial syndromes associated with increased risk of diverticulosis

Table 1.

Extrinsic factors for diverticular disease

| Risk factor | Potential risk factor | Potential protective factor | No effect | Potential risk factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Hypertension | Vegetarianism | Sex | Family history |

| Obesity | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Exercise | Red meat consumption | |

| Smoking | Medication: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (including aspirin), steroids | Nuts, corn, seeds | Fibre | |

| High levels of vitamin D | Alcohol | |||

| Medication: statins, probiotics | Microbiome profile |

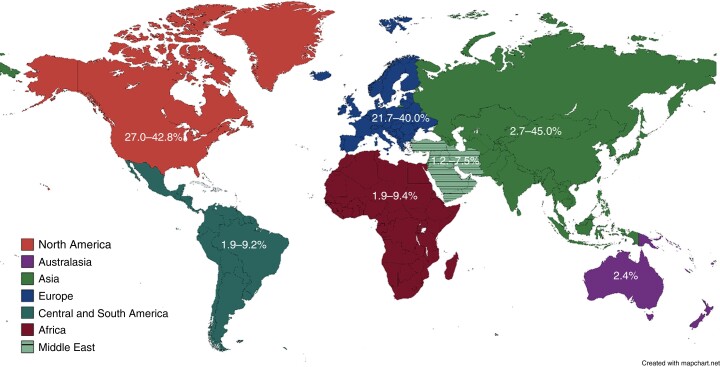

Location

DD is found throughout the world and has become increasingly common notwithstanding global variation. South-East Asia reports predominantly right-sided true diverticulosis of 70–98% of all cases, peaking in the fifth decade with an overall prevalence between 8 and 25%10. Western populations have predominantly left-sided ‘false’ diverticulosis11,12 with over half of DD confined to the sigmoid colon13,14. False diverticula are an ‘out pouching’ of the mucosa/submucosa as compared with ‘true’ diverticula that contain all layers of the bowel wall.

North America has the highest incidence of DD worldwide, reaching 50% in the population over 60 years of age, followed by western Europe and Australia57. In contrast, Nigeria, Kenya and Egypt report the incidence of diverticulosis at colonoscopy as low as 9.4%, 6.6% and 2% respectively, although this may be biased by overall life expectancy15,58,59. Reports from Asia report a prevalence between 8 and 28.5%, which is variable depending on location and ethnicity, with a peak in the fifth decade of life60–63. Studies undertaken in Asia found DD affects the right colon in 70–98% of cases60. However, in Japan there has been a notable increase in prevalence (P < 0.01) from 66.0% in 2003 to 70.1% in 2011 in those aged over 60 and a higher prevalence of left-sided diverticulosis that is associated with the adoption of a westernized lifestyle46, Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Percentage prevalence of the presence of diverticulosis at colonoscopy cited in the literature by location

In Europe, the prevalence of diverticulosis among white Western patients is 15–35% at colonoscopy, more frequently left-sided in older patients13,64–66. However, a lower incidence has been shown in developing countries67. There is no large population data from the Arabic or South American countries.

Intrinsic factors

Disordered collagen and elastin are associated with diverticulosis. Increased rigidity and loss of tensile strength of the bowel wall is associated with densely packed collagen fibres with an overexpression of collagen cross-linking. Elastosis of the longitudinal muscle layer causes subsequent bowel wall thickening68.

Neuromuscular activity is affected by reduction in the myenteric plexus neurons and decreased myenteric glial cells and interstitial cells of Cajal with denervation hypersensitivity noted; this can cause uncoordinated contractions, high colonic pressure and associated muscle atrophy26,28. Neuromuscular colonic dysregulation may trigger symptoms of abdominal pain and cramping often associated with DD. Patients have a higher prevalence of visceral hypersensitivity45,69. Colonic motility is affected by serotonin levels and a significant decrease in 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) transporter (SERT) transcript levels has been found in the mucosa of patients with diverticulitis11,29.

Genetics

Extracellular matrix

The extracellular matrix (ECM), containing collagen, elastin and proteoglycans, maintains the integrity and flexibility of the colonic wall. Association with other connective tissue disorders such as rectal prolapse, polycystic kidney disease, heritable syndromes (Marfan or Ehlers–Danlos), female genital prolapse, aneurysm, inguinal hernia, hiatus hernia and joint dislocations points to an inherent underlying weakness in the connective tissue70,71. To maintain structure collagen forms cross-links; however, excessive cross-linking causes rigidity and loss of tensile strength, which has been associated with a low fibre diet with specific alterations in collagen demonstrated in diverticulosis72.

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome is a group of 13 inherited connective tissue disorders arising through mutations in COL5A1 or COL5A2 genes that partially encode type V collagen protein or the ECM protein tenascin-X73. Similarly, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in COL3A1, with alteration in the collagen vascular system associated with inflammation, have been most strongly associated in Caucasian men when diverticulosis is present19,74,75. SNP missense variations in COLQ were found in both the Icelandic and Danish population studies; although the association is not of genome-wide significance, the replicable probability established by the association of rs7609897-T and the suggested association of rs146687198-G points to COLQ as a causative gene76. COLQ mutations can cause muscle weakness by reducing available acetylcholinesterase (AChE) at the neuromuscular junction; COLQ encodes a subunit of a collagen-like molecule that anchors AChE to the basal lamina. In addition, mutations in the ELN gene, encoding elastin, have been found in association with diverticulosis77.

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) are a family of homologous zinc-dependent endopeptidases. MMP 1, 8, 13 and 18 form the subgroups of collagenases. Activation of MMP results in an enzymatic cascade resulting in degradation and remodelling of the ECM including collagen, proteoglycans and other glycoproteins. Dysregulation of MMP has been shown to affect gut healing in several colonic diseases, for example enteric fistula formation in inflammatory bowel disease (BD)74,78.

Whilst a collagen deficit does not identify individuals who will go on to develop diverticulitis, one study demonstrated downregulation of MMP2, MMP9 and MMP13 expression and an increase in MMP1, TIMP1 and TIMP3 in inflamed mucosa of patients with diverticulitis versus Crohn’s disease. TIMP1 and TIMP3 are tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases that affect the turnover of the ECM by controlling MMP activity79,80. The pathophysiological correspondence between diverticulitis and IBD is still unclear, with clinical overlap most notable in segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis (SCAD)81. Whilst the two diseases appear genetically separate, they share pathways of inflammation and fibrosis. At a molecular level, patients with IBD and diverticulitis were found to have similar levels of the inflammatory protein syndecan-1 (SD1) but significantly higher expression of basic fibroblastic growth factor (bFGF) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF-α) in diverticulitis82–84.

Furthermore, LAMN4, the laminin β-4 gene, localizes to the myenteric plexus of colonic tissue, a constituent of the ECM that has a role in regulation, development and colonic dysmotility. Two variants in this gene caused a reduction in laminin in a cohort of diverticulitis compared with controls77,85.

Growth factor genes EGF, IGFI, CSF1, PDGF, and TPH-1 were found to have no significant association with DD86,87 (see Table 2 for familial syndromes associated with diverticulosis).

Neuromuscular function and motility

Neuromuscular function is intrinsically linked to the signalling pathways and downstream effects of the ECM. Histological staining has shown an increase in collagen fibres between the smooth muscle bundles in diverticulosis, associated with a decrease in TACR1 and TACR2, which encode the NK2 receptor88.

Compared with controls, thicker circular and longitudinal muscle layers were present in DD with an increased connective tissue index and smooth muscle alterations89. This has been linked to variation in mRNA expression; deficiency in the GDNF system results in decreased SNAP-25 (synaptosomal-associated protein) and GDNF mRNA expression producing diminished immunoreactive signals in the enteric ganglia and a significant reduction in GFRa1 and RET (rearranged in transfection) receptors which code tyrosine kinase respectively90–92. The mRNA of Phox2b, expressed in the myenteric neuronal and glial part of the enteric nervous system, was increased in patients with diverticulitis92.

The prime gene candidates of interest among gene variants associated with alteration in neuromuscular function are ANO1, PPP1R14A, COLQ6, COL6A1, CALCB and CALCA, of which ANO1 affects muscle contraction by influencing calcium-activated chloride channels in the pacemaker interstitial cells of Cajal93. COL6A1, along with ARHGAP15 and S100A10, are proposed to impact the structure and tensile strength of smooth muscle; however, the SNPs and SNVs (single nucleotide variants) identified thus far in relation to these genes are mostly intronic and of unclear clinical significance94.

Several motility studies have shown dysregulation in association with DD. For example, upregulation of the nitrergic pathway has been recorded in early stages of diverticulosis and may play a role in colonic motor disorders95. Similarly, serotonin is a primary trigger for peristalsis, secretion and visceral sensation, dysregulation of which is observed in IBD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in addition to diverticulitis. Smoothelin-A is a marker protein for smooth muscle contraction, inactivation of which results in a decrease in contractile potential, slow irregular wave patterns and colonic obstruction in knockout of the Smoothelin gene in a mouse model96.

Vascular alteration

The genes ELN, BMPR1B, and EFEMP1 are associated with connective tissue laxity, which may predispose to shearing of the culprit artery in diverticular bleeds. The ABO gene, related to the blood group system, encodes carbohydrates expressed on the surface of many tissues, increasing the risk of thrombosis and haemorrhage, in particular gastrointestinal bleeding. Similarly, P2RY12 has a role in platelet function. Other genes associated with vascular disease include CALCB, SLC35F3 and CACNB2, supporting the hypothesis that vascular disease drives diverticulitis94. CALCB is also associated with afferent nerve function and calcium balance, suggesting a role for dysmotility in diverticulitis pathophysiology.

The WNT signalling pathway, regulating cellular morphology and proliferation, is another key influence associated with DD, mediated by the RHOU gene that also has proangiogenic and human endothelial progenitor functions. WNT4 is related to vascular smooth cell proliferation and this potentially supports the link between smooth muscle hypertrophy and atherogenesis in diverticulosis. The WNT family proteins are also reported to differentiate intestinal neuronal and glial cells and play a role in anti-inflammatory activity in a rat model, suggesting that WNT family genes play a pivotal role in the development of diverticulosis and the potential complication of diverticular bleeding97.

The clinical implications of genetic effects on the vasculature are evident in the impact of Nicorandil. First prescribed in 1984 for angina, reports of gastrointestinal ulceration and fistulation led to restriction of the drug. Data has shown that individuals with DD are at an increased risk of bowel perforation and seven times more likely to develop a fistula. It has been hypothesized that toxic Nicorandil metabolites accumulate in the blood vessels that often occur as the focal point of weakness within a diverticulum and cause ulceration, or the nitrous oxide released by the proinflammatory Nicorandil may trigger fistula formation among sigmoid diverticula. It has been proposed that genotyping may be used to guide prescribing by stratifying the individual risk of side effects96,98.

Immunity

Inflammatory pathways have undergone less scrutiny thus far. Hub genes RASAL3, SASH3, PTPRC, and INPP5D were found to upregulate immune response-associated transcripts in the sigmoid colons of chronic, recurrent diverticulitis patients as identified by Schiefer et al25. These interconnected hub genes affect a network of immune regulators. RASAL3 regulates natural killer T cell expansion and function in mouse models. INPP5D (SHIP1) is a leucocyte-specific molecule which negatively regulates phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; it is proposed that upregulation of dephosphorylation affects signalling in the AKT (serine/threonine-protein kinase) pathway, increasing the rate of apoptosis. Reduced levels were found in intestinal biopsies of patients with Crohn’s disease and increased levels have been demonstrated in diverticulitis. PTPRC (CD45) encodes a cell-surface glycoprotein involved in protein tyrosine phosphorylation, in particular the initiation of leucocyte-specific immune responses resulting in high levels of inflammatory cytokines which may play a role in the chronicity of diverticulitis.

GWAS on the Icelandic, Denmark and UK populations replicated gene variants in ARHGAP15, COLQ and FAM155A with increased association with diverticulitis over diverticulosis76. Variants in ARHGAP15, the gene for Rho GTPase (guanosine triphosphate) activating protein 15, are associated with phagocyte function and inflammation; the role of FAM155A is unclear but is proposed to have a protective role against infection and inflammation6. The relative genetic risk of 27 replicating loci in a European cohort identified that PHGR1, FAM155A-2, CALCB and S100A10 had a stronger effect in patients with diverticulitis as opposed to diverticulosis. Variants in PHGR1 may induce inflammation by causing epithelial dysfunction and increasing the likelihood of bacterial penetration. S100A10 regulates the remodelling of the extracellular matrix, further supporting the proposal that dysmotility and colon wall weakness have a role in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis94.

Two smaller studies found an associated SNP in the TNFSF15 gene in the subset of patients requiring surgery for diverticulitis; TNFSF15 encodes a cytokine in the TNF family and has been associated with severe IBD56,99,100. Connelly et al. propose the SNP rs7848647 may have the potential as a marker for DD severity to assist surgical decision-making. A rare SNP encoding a D435N substitution in LAMB4 has also been described in diverticulitis and is known to play a role in intestinal barrier function74. Rat models have identified SNP variants near the OAS1/3 gene that are upregulated by cytotoxic insult and interferons; OAS encodes a family of proteins with antiviral and apoptotic effects, the induction of which can result in chronic low-grade inflammation in the colonic wall97.

The association between diverticulitis with an allergic histamine response was studied and showed strong expression of H1R and H2R mRNA found in the colonic epithelium of complicated diverticulitis compared with controls and non-complicated diverticulitis, characterized by increased histamine release and massive inflammatory infiltration. Histamine is known as a regulator of gastrointestinal functions, such as gastric acid production, intestinal motility and mucosal ion secretion101,102.

At the transcriptome level an enrichment of innate and adaptive immune system pathways is observed in the sigmoid tissue of patients with diverticulitis. Network analysis suggests that diverticulitis is associated with dysregulation of the immune system both genetically and histologically92. However, in-depth analysis of wound healing transcriptome factors showed no statistical correlation with diverticulitis, and several genes identified have an unknown molecular pathway, highlighting the need for further research22,55.

The interactions between the molecular pathways and the host microbiome have also been demonstrated to play an important role in gut health and the growing understanding in this area has changed guidelines around antibiotic usage for uncomplicated diverticulitis. However, the interaction of genomics with the microbiome is an exciting area of development103. For example, bacteria and fungi can induce interferon expression that may alter the expression of OAS genes. Patients with early-onset DD were found to have elevated expression of host genes involved in the antiviral response, implying that susceptibility to a viral pathogen may play a role in the development of diverticulitis24.

The potential role of microbiota composition in the pathogenesis of diverticulosis is under investigation. In a prospective study of 43 patients comparing the microbiota profiles of patients with asymptomatic diverticulosis versus controls who underwent colonoscopy, no difference was detected between the two groups104. This is supported by further observational studies in the literature that did not detect a significant difference between microbiota in asymptomatic diverticulosis (AD) and controls, suggesting that microbiota may not play any role in the development of colonic diverticula5,105. However, in one study the symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD) group showed significant alterations of the microbiota profile, with a reduction in Enterobacteriaceae sp. and higher levels of Bacteroides/Prevotella sp. in the biopsies coinciding with a higher macrophage count. In the faecal analysis, SUDD patients exhibited a significant reduction of members of clostridium cluster IX, Fusobacteriae sp. and Lactobacillaceae sp.106. In another small case-control study 16 patients with DD showed significantly higher levels of Enterobacteriaceae sp. compared with 35 controls without any diverticula107. This suggests a potential role of microbiota in the development of symptoms, and the symbiotic and pathognomonic role of the gut microbiome requires further study108 (Table 3 lists intrinsic factors related to DD).

Table 3.

Intrinsic factors for diverticular disease

| Increased |

| Gut motility |

| Abnormal |

| Collagen |

| Elastin |

| Enteric nervous system |

| Decreased |

| Serotonin |

Epigenetics

Epigenetics is an important area of research assessing the impact of environmental factors on gene expression such as methylation. There is little published evidence on the impact of epigenetics on diverticulosis or diverticulitis but there have been interesting studies demonstrating immune cell epigenetic-mediated susceptibility to sepsis107. Early epigenetic data suggest variation in gene expression within molecular pathways in early- and late-onset diverticulitis, with early-onset diverticulitis displaying an increased expression of antiviral response genes25. This built on earlier work, by the same team, which suggested the hub genes RASAL3, SASH3, PTPRC and INPP5D within the brown module eigengene were highly correlated (r = 0.67, P = 0.0004) with diverticulitis. This data was supported by downstream analysis showing that transcripts associated with the immune response were upregulated in adjacent tissue from the sigmoid colons of chronic, recurrent diverticulitis patients25.

Exploratory studies such as DAMASCUS (Diverticulitis management, a snapshot collaborative audit study)109, gut microbiome work and broader demographic profiles will further the understanding and impact of epigenetics in diverticulitis110.

Discussion

The genomic understanding of the causation and pathophysiology of the spectrum of DD is an area of fervent research. There is evidence of the genomic risk associated with DD, approximately 50%, as demonstrated in the Twin Studies and, whilst the variety of literature is limited, the wealth of information provided by GWAS provides novel pathophysiological insight.

Four GWAS undertaken in the UK, Europe and Korea have identified 49 susceptible loci, 25 replicated, associated with DD76,93,97,111. Two discriminated between diverticulosis and diverticulitis. Mapping has identified significant loci expression in pathways of extracellular matrix, connective tissue formation, immunity, membrane transport, cell adhesion and intestinal motility. These associated loci are highly expressed in mesenchymal stem cells, connective tissue cells and vascular cells77. Four replicated loci, ARHGAP15, COLQ, FAM155A and TNFSF15, are highlighted to have a stronger association with diverticulitis and may have a role in inflammation.

Due to the heterogenous nature of the disease and confusion about the most appropriate management pathways, clear classification and nomenclature is paramount; this has often been ambiguous in the literature. Diverticulosis is defined as the anatomical presence of colonic diverticula and DD as clinically significant and symptomatic diverticulosis. The umbrella term diverticular disease covers symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease (SUDD), a subtype of DD characterized by persistent abdominal symptoms in the absence of macroscopic colitis or diverticulitis, and diverticular bleed. Diverticulitis is the presence of macroscopic inflammation within the diverticula and can be complicated or uncomplicated; uncomplicated diverticulitis is identified on CT scan showing signs of inflammation such as colonic wall thickness and mesenteric/pericolic fat stranding, and becomes complicated with the addition of abscess, peritonitis, obstruction, fistula or per rectal haemorrhage. The colonoscopic Diverticular Inflammation and Complication Assessment (DICA) and radiological Hinchey classifications for standardized diagnostic reporting are now widely used6,7. Another condition, SCAD, is associated with the spectrum of DD with a clinical overlap to IBD; however, it may be considered a clinically distinct entity with different pathogenesis and surgical management8.

The most substantial genetic information on DD has been provided by GWAS. Sigurdsson et al.75 performed GWAS on Icelandic and Danish populations; however, in the Danish population they did not have the clinical data to separate into diverticulosis, DD and diverticulitis subsets, whereas Schafmayer et al.109 used the International Classification of Disease 10 diagnostic coding. Using population cohorts may lead to higher inaccuracy in clinical data than a case-control cohort; however, the statistical power from increased cohort size often outweighs this bias. Participant age ranges were also not provided, which leads to the additional concern of misclassification in a potentially younger cohort who may yet develop a diagnosis of diverticulosis. Schafmayer et al.109 and Maguire et al.91 studied the UK Biobank, a prospective cohort study on ∼500 000 population-based individuals, with different hospital registers for comparison identifying 39 and 48 susceptibility loci respectively. GWAS loci usually harbour multiple genes, making the causal gene hard to identify. Candidate genes can be identified by downstream in silico analysis and additional analysis of mRNA expression and fluorescence immunohistochemical staining in colonic biopsies. However, due to the intronic nature of several gene variants identified, these mechanisms must be viewed hypothetically, in need of robust study to interrogate functional impact102,112.

There is a known ethnic variation between Eastern and Western populations and caution must be exercised interpreting the presence of mutations and generalizing data within the demographic context. Choe et al. performed a GWAS in Korea that identified three novel loci associated with WNT, RHOU, and OAS 1/3, which were not described in the Western cohorts of the other GWAS that has a greater overlap of identified loci. Large-scale epidemiological studies assessing the role of fibre were undertaken in the USA and Japan and had similar results33,35. These studies do not consider the socioeconomic background of the participants. Furthermore, studies reporting prevalence do not consider comparative life expectancy or access to healthcare and colonoscopy. This requires further exploration as the body of the literature has been undertaken in Western populations.

The multifactorial nature of DD presents difficulties in interpreting the specificity of complex genomic interactions and molecular pathways. Diverticulosis is associated with numerous co-morbidities including obesity, hypertension and age, which may increase mutation and affect phenotype. Awareness for the presence of simultaneous gastrointestinal diseases and other connective tissue disorders is also required; a candidate-gene study assessing colon cancer found an association between diverticulosis and a variant in RPRM, a tumour suppressor gene regulating the G2 arrest of the cell cycle113. Strikingly, there is minimal overlap between diverticulitis and other inflammatory bowel diseases114.

The crucial question yet to be determined is the distinction between causation and association for the identified, replicable loci. For example, serotonin is the primary trigger for gut motility, and it is unclear if the upregulation of 5HT-4R, the gene associated with serotonin production, is a causative factor for diverticulitis or a phenotypic effect of localized inflammation87. Further studies are required to identify the causative genetic factor of diverticulosis and diverticulitis and associated genetic changes influenced by other risk factors. The ALADDIN (alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency carriers in a population with and without colonic diverticula) study is underway to investigate A1AT deficiency, a protease inhibitor that protects connective tissue, as a causative risk factor for the development of diverticulosis113.

This review has a number of limitations, most notably the lack of meta-analysis due to the limited literature. It was not possible to analyse the replicability or strength of association for each mutation or demonstrate significant differences between different patient cohorts. Bias was not formally assessed in the papers, however, this is of less relevance, given the low level of evidence of the studies and citing articles excluding the higher quality GWAS. The limitations of this study highlight the need for robust, replicable research into DD that can be translated into clinical practice.

The evidence supports the importance of genomics as a crucial factor in the pathophysiology of diverticula formation and the risk of diverticulitis. COLQ, FAM155A, PHGR1, ARHGAP15, S100A10, and TNFSF15 are the strongest candidates for further research to develop a tool to clinically stratify patients into surgical and conservative management. Including genomics there is a need for more ‘omic’ research in areas such as epigenomics, transcriptomics, microbiomics and metabolomics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Mary Smith, Clinical Support Librarian, Exeter Health Library (database search assistance).

Contributor Information

Hannah N Humphrey, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Devon University Healthcare Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK.

Pauline Sibley, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Devon University Healthcare Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK.

Eleanor T Walker, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Devon University Healthcare Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK.

Deborah S Keller, Department of Surgery, Lankenau Medical Center and Lankenau Institute for Medical Research, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, USA.

Francesco Pata, Department of Pharmacy, Health and Nutritional Sciences, University of Calabria, Rende, Italy.

Dale Vimalachandran, Department of Molecular & Cancer Medicine, Institute of Cancer Medicine, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK; Department of Colorectal Surgery, Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Chester, UK.

Ian R Daniels, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Devon University Healthcare Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK.

Frank D McDermott, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Royal Devon University Healthcare Foundation Trust, Exeter, UK.

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJS Open online.

Data availability

No novel data are included in this systematic review.

Author contributions

Hana Humphrey (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Pauline Sibley (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Eleanor Walker (Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Debby Keller (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Francesco Pata (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Dale Vimalachandran (Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing), Ian Daniels (Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing—review & editing) and Frank McDermott (Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing). The final manuscript was approved by all authors

References

- 1. Templeton AW, Strate LL. Updates in diverticular disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2013;15:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Di Mario F, Elisei W, Picchio M, Allegretta L et al. Prognostic performance of the ‘DICA’ endoscopic classification and the ‘CODA’ score in predicting clinical outcomes of diverticular disease: an international, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Gut 2022;71:1350–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ebersole J, Medvecz AJ, Connolly C, Sborov K, Matevish L, Wile G et al. Comparison of American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grading scale with modified Hinchey classification in acute colonic diverticulitis: a pilot study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;88:770–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tănase I, Păun S, Stoica B, Negoi I, Gaspar B, Beuran M. Epidemiology of diverticular disease—systematic review of the literature. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2015;110:9–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Freeman HJ. Segmental colitis associated diverticulosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:8067–8069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1282–98.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Binda GA, Mataloni F, Bruzzone M, Carabotti M, Cirocchi R, Nascimbeni R et al. Trends in hospital admission for acute diverticulitis in Italy from 2008 to 2015. Tech Coloproctol 2018;22:597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tursi A, Mastromarino P, Capobianco D, Elisei W, Miccheli A, Capuani G et al. Assessment of fecal microbiota and fecal metabolome in symptomatic uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016;50:S9–S12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tursi A. Diverticulosis today: unfashionable and still under-researched. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016;9:213–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner GA, O'Grady MJ, Purcell RV, Frizelle FA. The epidemiology and etiology of right-sided colonic diverticulosis: a review. Ann Coloproctol 2021;37:196–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rajendra S, Ho JJ. Colonic diverticular disease in a multiracial Asian patient population has an ethnic predilection. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;17:871–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miulescu AM. Colonic diverticulosis. Is there a genetic component? Maedica (Bucur) 2020;15:105–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loffeld RJ, Van Der Putten AB. Diverticular disease of the colon and concomitant abnormalities in patients undergoing endoscopic evaluation of the large bowel. Colorectal Dis 2002;4:189–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tursi A, Scarpignato C, Strate LL, Lanas A, Kruis W, Lahat A et al. Colonic diverticular disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calder JF. Diverticular disease of the colon in Africans. Br Med J 1979;1:1465–1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maguire LH. Genetic risk factors for diverticular disease—emerging evidence. J Gastrointest Surg 2020;24:2314–2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strate LL, Erichsen R, Baron JA, Mortensen J, Pedersen JK, Riis AH et al. Heritability and familial aggregation of diverticular disease: a population-based study of twins and siblings. Gastroenterology 2013;144:736–42.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Granlund J, Svensson T, Olen O, Hjern F, Pedersen NL, Magnusson PKE et al. The genetic influence on diverticular disease—a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeut 2012;35:1103–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stumpf M, Cao W, Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Kasperk R, Schumpelick V. Increased distribution of collagen type III and reduced expression of matrix metalloproteinase 1 in patients with diverticular disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2001;16:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peery AF, Keku TO, Galanko JA, Sandler RS. Sex and race disparities in diverticulosis prevalence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:1980–1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peery AF, Shaukat A, Strate LL. AGA clinical practice update on medical management of colonic diverticulitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol 2021;160:906–11.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Connelly TM, Berg AS, Harris LR 3rd, Tappouni R, Brinton D, Deiling S et al. Surgical diverticulitis is not associated with defects in the expression of wound healing genes. Int J Colorectal Dis 2015; 30:1247–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schieffer KM, Kline BP, Harris LR, Deiling S, Koltun WA, Yochum GS. A differential host response to viral infection defines a subset of earlier-onset diverticulitis patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2018;27:249–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schieffer KM, Choi CS, Emrich S, Harris L, Deiling S, Karamchandani DM et al. RNA-seq implicates deregulation of the immune system in the pathogenesis of diverticulitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2017;313:G277–GG84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Strate LL, Modi R, Cohen E, Spiegel BM. Diverticular disease as a chronic illness: evolving epidemiologic and clinical insights. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1486–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Painter NS, Burkitt DP. Diverticular disease of the colon: a deficiency disease of western civilization. Br Med J 1971;2:450–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Floch MH, Bina I. The natural history of diverticulitis: fact and theory. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:S2–S7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim HU, Kim YH, Choe WH, Kim JH, Youk CM, Lee JU et al. Clinical characteristics of colonic diverticulitis in Koreans. Korean J Gastroenterol 2003;42:363–368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohan JN, Horns JJ, Hanson HA, Allen-Brady K, Kieffer MC, Huang LC et al. The association between family history and diverticulitis recurrence: a population-based study. Dis Colon Rectum 2023;66:269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kopylov U, Ben-Horin S, Lahat A, Segev S, Avidan B, Carter D. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and the risk of development of colonic diverticulosis. Digestion 2012;86:201–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Song JH, Kim YS, Lee JH, Ok KS, Ryu SH, Moon JS. Clinical characteristics of colonic diverticulosis in Korea: a prospective study. Korean J Intern Med 2010;25:140–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu PH, Cao Y, Keeley BR, Tam I, Wu K, Strate LL et al. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle is associated with a lower risk of diverticulitis among men. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1868–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peery AF, Barrett PR, Park D, Rogers AJ, Galanko JA, Martin CF et al. A high-fiber diet does not protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology 2012;142:266–72.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peery AF, Sandler RS, Ahnen DJ, Galanko JA, Holm AN, Shaukat A et al. Constipation and a low-fiber diet are not associated with diverticulosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1622–1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Key TJ. Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC): prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ 2011;343:d4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Crowe FL, Balkwill A, Cairns BJ, Appleby PN, Green J, Reeves GK et al. Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut 2014;63:1450–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reichert MC, Lammert F. The genetic epidemiology of diverticulosis and diverticular disease: emerging evidence. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2015;3:409–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maguire L. Understanding the natural history of the disease. Semin Colon Rectal Surg 2021;32:100795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maguire LH, Song M, Strate LE, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Higher serum levels of vitamin D are associated with a reduced risk of diverticulitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1631–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strate LL, Keeley BR, Cao Y, Wu K, Giovannucci EL, Chan AT. Western dietary pattern increases, and prudent dietary pattern decreases, risk of incident diverticulitis in a prospective cohort study. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1023–30.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing AL, Trichopoulos DV, Willett WC. A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Ann Epidemiol 1995;5:221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sakuta H, Suzuki T. Prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes and hypertension are elevated among middle-aged Japanese men with colonic diverticulum. Environ Health Prev Med 2007;12:97–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hjern F, Wolk A, Håkansson N. Smoking and the risk of diverticular disease in women. Br J Surg 2011;98:997–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Humes DJ, Simpson J, Smith J, Sutton P, Zaitoun A, Bush D et al. Visceral hypersensitivity in symptomatic diverticular disease and the role of neuropeptides and low grade inflammation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:318–e163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nagata N, Niikura R, Shimbo T, Kishida Y, Sekine K, Tanaka S et al. Alcohol and smoking affect risk of uncomplicated colonic diverticulosis in Japan. PLoS One 2013;8:e81137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Aune D, Sen A, Leitzmann MF, Tonstad S, Norat T, Vatten LJ. Tobacco smoking and the risk of diverticular disease—a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:621–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lindor NM, Bristow J. Tenascin-X deficiency in autosomal recessive Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2005;135:75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Santin BJ, Prasad V, Caniano DA. Colonic diverticulitis in adolescents: an index case and associated syndromes. Pediatr Surg Int 2009;25:901–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Deshpande AV, Oliver M, Yin M, Goh TH, Hutson JM. Severe colonic diverticulitis in an adolescent with Williams syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health 2005;41:687–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pourfarziani V, Mousavi-Nayeeni SM, Ghaheri H, Assari S, Saadat SH, Panahi F et al. The outcome of diverticulosis in kidney recipients with polycystic kidney disease. Transplant Proc 2007;39:1054–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Machin GA, Walther GL, Fraser VM. Autopsy findings in two adult siblings with Coffin-Lowry syndrome. Am J Med Genet Suppl 1987;3:303–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Robey BS, Peery AF, Dellon ES. Small bowel diverticulosis and jejunal perforation in Marfan syndrome. ACG Case Rep J 2018;5:1–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maconi G, Pini A, Pasqualone E, Ardizzone S, Bassotti G. Abdominal symptoms and colonic diverticula in Marfan's syndrome: a clinical and ultrasonographic case control study. J Clin Med 2020;9:3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kline BP, Schieffer KM, Choi CS, Connelly T, Chen J, Harris L et al. Multifocal versus conventional unifocal diverticulitis: a comparison of clinical and transcriptomic characteristics. Dig Dis Sci 2019;64:3143–3151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Connelly TM, Berg AS, Hegarty JP, Deiling S, Brinton D, Poritz LS et al. The TNFSF15 gene single nucleotide polymorphism rs7848647 is associated with surgical diverticulitis. Ann Surg 2014;259:1132–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Warner E, Crighton EJ, Moineddin R, Mamdani M, Upshur R. Fourteen-year study of hospital admissions for diverticular disease in Ontario. Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21:97–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alatise OI, Arigbabu AO, Agbakwuru EA, Lawal OO, Ndububa DA, Ojo OS. Spectrum of colonoscopy findings in Ile-Ife Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2012;19:219–224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Elbatea H, Enaba M, Elkassas G, El-Kalla F, Elfert AA. Indications and outcome of colonoscopy in the middle of Nile delta of Egypt. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:2120–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Miura S, Kodaira S, Shatari T, Nishioka M, Hosoda Y, Hisa TK. Recent trends in diverticulosis of the right colon in Japan: retrospective review in a regional hospital. Dis Colon Rectum 2000;43:1383–1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chan CC, Lo KK, Chung EC, Lo SS, Hon TY. Colonic diverticulosis in Hong Kong: distribution pattern and clinical significance. Clin Radiol 1998;53:842–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fong SS, Tan EY, Foo A, Sim R, Cheong DM. The changing trend of diverticular disease in a developing nation. Colorectal Dis 2011;13:312–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lohsiriwat V, Suthikeeree W. Pattern and distribution of colonic diverticulosis: analysis of 2877 barium enemas in Thailand. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:8709–8713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Blachut K, Paradowski L, Garcarek J. Prevalence and distribution of the colonic diverticulosis. Review of 417 cases from Lower Silesia in Poland. Rom J Gastroenterol 2004;13:281–285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Paspatis GA, Papanikolaou N, Zois E, Michalodimitrakis E. Prevalence of polyps and diverticulosis of the large bowel in the Cretan population. An autopsy study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2001;16:257–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Delvaux M. Diverticular disease of the colon in Europe: epidemiology, impact on citizen health and prevention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;18:71–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Miron A, Ardelean M, Bogdan M, Giulea C. Surgical management of colonic diverticular disease. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2007;102:37–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Whiteway J, Morson BC. Elastosis in diverticular disease of the sigmoid colon. Gut 1985;26:258–266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Clemens CH, Samsom M, Roelofs J, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Smout AJ. Colorectal visceral perception in diverticular disease. Gut 2004;53:717–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Broad JB, Wu Z, Clark TG, Musson D, Jaung R, Arroll B et al. Diverticulosis and nine connective tissue disorders: epidemiological support for an association. Connect Tissue Res 2019;60:389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Commane DM, Arasaradnam RP, Mills S, Mathers JC, Bradburn M. Diet, ageing and genetic factors in the pathogenesis of diverticular disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:2479–2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Petruzziello L, Iacopini F, Bulajic M, Shah S, Costamagna G. Review article: uncomplicated diverticular disease of the colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:1379–1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Malfait F, Francomano C, Byers P, Belmont J, Berglund B, Black J et al. The 2017 international classification of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2017;175:8–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Nasef NA, Mehta S. Role of inflammation in pathophysiology of colonic disease: an update. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:4748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Reichert MC, Kupcinskas J, Krawczyk M, Jungst C, Casper M, Grunhage F et al. A variant of COL3A1 (rs3134646) is associated with risk of developing diverticulosis in white men. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:604–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sigurdsson S, Alexandersson KF, Sulem P, Feenstra B, Gudmundsdottir S, Halldorsson GH et al. Sequence variants in ARHGAP15, COLQ and FAM155A associate with diverticular disease and diverticulitis. Nat Commun 2017;8:15789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mastoraki A, Schizas D, Tousia A, Chatzopoulos G, Gkiala A, Syllaios A et al. Evaluation of molecular and genetic predisposing parameters at diverticular disease of the colon. Int J Colorectal Dis 2021;36:903–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stumpf M, Krones CJ, Klinge U, Rosch R, Junge K, Schumpelick V. Collagen in colon disease. Hernia 2006;10:498–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Altadill A, Eiró N, González LO, Junquera S, González-Quintana JM, Sánchez MR et al. Comparative analysis of the expression of metalloproteases and their inhibitors in resected Crohn's disease and complicated diverticular disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:120–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Nehring P, Gromadzka G, Giermaziak A, Jastrzębski M, Przybyłkowski A. Genetic variants of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase 1 (rs4898) and 2 (rs8179090) in diverticulosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;33:e431–e434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sladen GE, Filipe MI. Is segmental colitis a complication of diverticular disease?. Dis Colon Rectum 1984;27:513–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Inchingolo CD, Nenna R et al. Mucosal expression of basic fibroblastic growth factor, syndecan 1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in diverticular disease of the colon: a case-control study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:836–e396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Tursi A, Elisei W, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Inchingolo CD, Nenna R et al. Musosal tumour necrosis factor α in diverticular disease of the colon is overexpressed with disease severity. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:e258–e263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tursi A, Elisei W, Inchingolo CD, Nenna R, Picchio M, Ierardi E et al. Chronic diverticulitis and Crohn's disease share the same expression of basic fibroblastic growth factor, syndecan 1 and tumour necrosis factor-α. J Clin Pathol 2014;67:844–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Coble JL, Sheldon KE, Yue F, Salameh TJ, Harris LR III, Deiling S et al. Identification of a rare LAMB4 variant associated with familial diverticulitis through exome sequencing. Hum Mol Genet 2017;26:3212–3220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Alexander RJ, Panja A, Kaplan-Liss E, Mayer L, Raicht RF. Expression of growth factor receptor-encoded mRNA by colonic epithelial cells is altered in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Costedio MM, Coates MD, Danielson AB, Buttolph TR III, Blaszyk HJ, Mawe GM et al. Serotonin signaling in diverticular disease. J Gastrointest Surg 2008;12:1439–1445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Liu L, Markus I, Saghire HE, Perera DS, King DW, Burcher E. Distinct differences in tachykinin gene expression in ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and diverticular disease: a role for hemokinin-1? Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:475–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hellwig I, Böttner M, Barrenschee M, Harde J, Egberts JH, Becker T et al. Alterations of the enteric smooth musculature in diverticular disease. J Gastroenterol 2014;49:1241–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Barrenschee M, Böttner M, Harde J, Lange C, Cossais F, Ebsen M et al. SNAP-25 is abundantly expressed in enteric neuronal networks and upregulated by the neurotrophic factor GDNF. Histochem Cell Biol 2015;143:611–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Böttner M, Barrenschee M, Hellwig I, Harde J, Egberts JH, Becker T et al. The GDNF system is altered in diverticular disease—implications for pathogenesis. PLoS One 2013;8:e66290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cossais F, Lange C, Barrenschee M, Möding M, Ebsen M, Vogel I et al. Altered enteric expression of the homeobox transcription factor Phox2b in patients with diverticular disease. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2019;7:349–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Maguire LH, Handelman SK, Du X, Chen Y, Pers TH, Speliotes EK. Genome-wide association analyses identify 39 new susceptibility loci for diverticular disease. Nat Genet 2018;50:1359–1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Camilleri M, Sandler RS, Peery AF. Etiopathogenetic mechanisms in diverticular disease of the colon. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;9:15–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Espín F, Rofes L, Ortega O, Clavé P, Gallego D. Nitrergic neuro-muscular transmission is up-regulated in patients with diverticulosis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;26:1458–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Niessen P, Rensen S, van Deursen J, De Man J, De Laet A, Vanderwinden JM et al. Smoothelin-A is essential for functional intestinal smooth muscle contractility in mice. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1592–1601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Choe EK, Lee JE, Chung SJ, Yang SY, Kim YS, Shin ES et al. Genome-wide association study of right-sided colonic diverticulosis in a Korean population. Sci Rep 2019;9:7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Noyes JD, Mordi IR, Doney AS, Palmer CNA, Pearson ER, Lang CC. Genetic risk of diverticular disease predicts early stoppage of Nicorandil. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020;108:1171–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Connelly TM, Choi CS, Berg AS, Harris L, Coble J, Koltun WA. Diverticulitis and Crohn's disease have distinct but overlapping tumor necrosis superfamily 15 haplotypes. J Surg Res 2017;214:262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Kadiyska T, Tourtourikov I, Popmihaylova AM, Kadian H, Chavoushian A. Role of TNFSF15 in the intestinal inflammatory response. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2018;9:73–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. von Rahden BH, Jurowich C, Kircher S, Lazariotou M, Jung M, Germer CT et al. Allergic predisposition, histamine and histamine receptor expression (H1R, H2R) are associated with complicated courses of sigmoid diverticulitis. J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. von Rahden BH, Germer CT. Pathogenesis of colonic diverticular disease. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2012;397:1025–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Cianci R, Frosali S, Pagliari D, Cesaro P, Petruzziello L, Casciano F et al. Uncomplicated diverticular disease: innate and adaptive immunity in human gut mucosa before and after rifaximin. J Immunol Res 2014;2014:696812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. van Rossen TM, Ooijevaar RE, Kuyvenhoven JP, Eck A, Bril H, Buijsman R et al. Microbiota composition and mucosal immunity in patients with asymptomatic diverticulosis and controls. PLoS One 2021;16:e0256657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Barbara G, Scaioli E, Barbaro MR, Biagi E, Laghi L, Cremon C et al. Gut microbiota, metabolome and immune signatures in patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease. Gut 2017;66:1252–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Linninge C, Roth B, Erlanson-Albertsson C, Molin G, Toth E, Ohlsson B. Abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in the colon mucosa in diverticular disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2018;9:18–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Gimenez JLC, Carbonell NE, Mateo CR, López EG, Palacios L, Chova LP et al. Epigenetics as the driving force in long-term immunosuppression. J Clin Epigenet 2016;2:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 108. Tursi A, Papa V, Lopetuso LR, Settanni CR, Gasbarrini A, Papa A. Microbiota composition in diverticular disease: implications for therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:14799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Pinkney T. Clinical research in colorectal surgery—where are we heading? Colorectal Dis 2021;23:2499–2500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Lewis SK, Nachun D, Martin MG, Horvath S, Coppola G, Jones DL. DNA methylation analysis validates organoids as a viable model for studying human intestinal aging. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;9:527–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Schafmayer C, Harrison JW, Buch S, Lange C, Reichert MC, Hofer P et al. Genome-wide association analysis of diverticular disease points towards neuromuscular, connective tissue and epithelial pathomechanisms. Gut 2019;68:854–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Weersma RK, Parkes M. Diverticular disease: picking pockets and population biobanks. Gut 2019;68:769–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Rottier SJ, de Jonge J, Dreuning LC, van Pelt J, van Geloven AAW, Beele XDY et al. Prevalence of alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency carriers in a population with and without colonic diverticula. A multicentre prospective case-control study: the ALADDIN study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2019;34:933–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Dai L, King DW, Perera DS, Lubowski DZ, Burcher E, Liu L. Inverse expression of prostaglandin E2-related enzymes highlights differences between diverticulitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:1236–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No novel data are included in this systematic review.