Lede:

This Translations piece argues that schools have been left out of research and policy discussions related to adolescent social media use, which misses opportunities to promote adolescent mental health.

Translations:

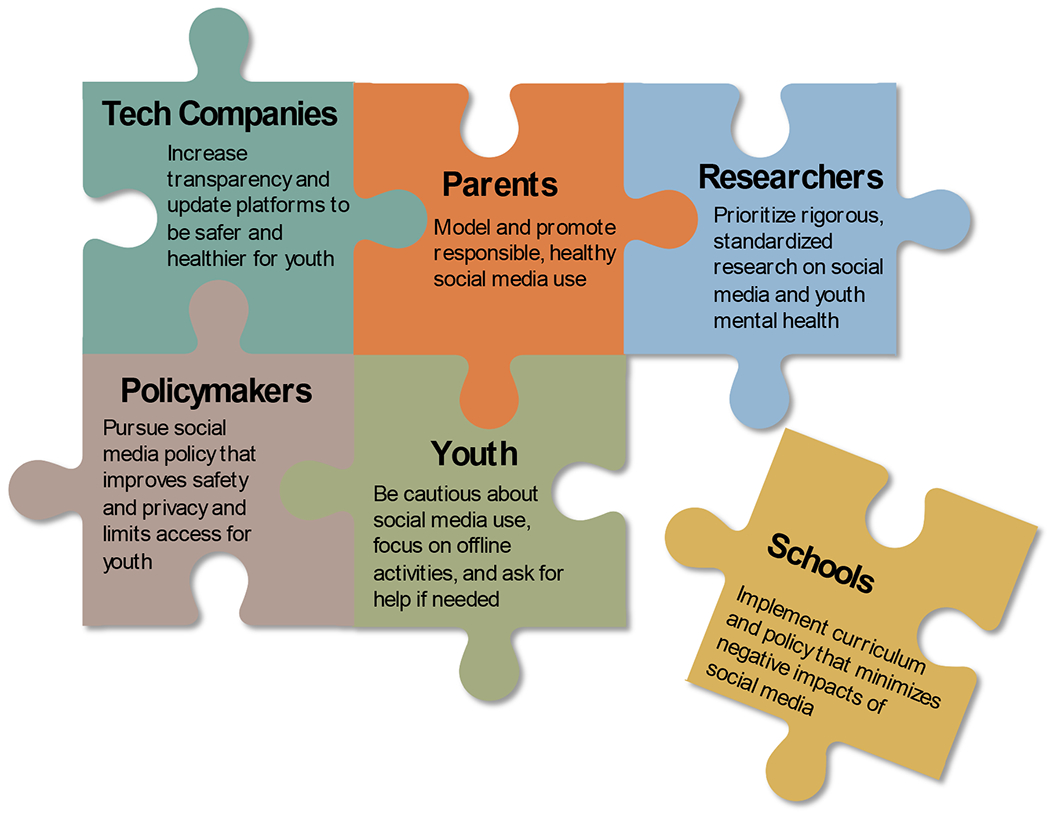

Last month, Congress held its most recent hearings focused on the mental health risks of social media for young people, and last year saw the emergence of two high profile policy reports on this topic. In May 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General released an advisory report1 that identified exposure to harmful content and problematic and addictive use of social media as detrimental to youth mental health. In December, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) released a more measured consensus study2 that called for development of standards for platform design and data use; digital literacy education; and more research. While the two reports differed in their conclusions, they both focused on recommendations directed at tech companies, policymakers, researchers, parents, and youth as key stakeholder groups. We argue that these reports, reflective of the broader national discourse on adolescent social media use, have left out a key stakeholder group that can serve as a useful site of intervention: schools.

Approximately 55 million U.S. youth spend most of their waking hours in school, where the vast majority have access to digital, Internet-connected devices.3 Teachers and administrators across the country make daily pedagogical and disciplinary decisions about student social media use. Schools– including administrators, teachers, and staff– are key stakeholders in the adolescent social media policy landscape because they have decision-making power regarding social media in the classroom and during other school hours. The school context offers as yet untapped opportunities to adjust and optimize social media policies and practices to support student mental health.

Input from education experts and school leaders – ideally in collaboration with the other stakeholder groups identified by the Surgeon General and the NASEM – could be leveraged to identify focus areas poised to have the most immediate, tangible, and beneficial effects for teens. Below we offer some initial suggestions:

1. Establish partnerships with schools as a key research site

Schools are a key site for the NASEM’s outlined research agenda. To inform effective policy, we encourage collaboration between researchers, policymakers and schools, not only on development and evaluation of programs on digital media literacy, but also on research related to safety and educational outcomes, as well as mental and physical health outcomes.

2. Develop best practices for social media as a teaching tool

The NASEM study acknowledged that reliance on technology in classrooms influences student use of social media, but the report missed an opportunity to recommend development of best practices for social media use in the classroom (beyond digital literacy training) and in the broader school environment. Specifically, educators utilize social media as a teaching tool in many ways,4 but there is minimal evidence of the impacts of these strategies and when and for whom they show benefit or harm. Education professional associations could work to clarify best practices for the use of social media as a teaching tool. At the local level, schools could then work to create standard operating procedures to guide teachers on appropriate use of social media.

3. Consider thoughtful restrictions on device use

Whole school policies aiming to influence smartphone and social media use have the potential to positively impact youth mental health.5 Research has suggested significant impact of device use on student attention and wellbeing outcomes, which has prompted some schools to adopt policies that restrict access to devices during selected school hours or even create “phone-free schools.”6 Anecdotal reports also suggest that phone-free schools may promote higher classroom engagement, although research should explore the possibility of nuanced or even negative effects in different types of schools and student bodies.

4. Increase awareness of social media monitoring

School districts across the country have purchased and implemented third-party social media monitoring (SMM) of their students, citing the need for increased security due to risk of school shootings, high rates of cyberbullying, and rising adolescent depression and suicide. The increasingly common use of SMM suggests that exclusion of schools from the policy discourse around adolescent social media use risks omitting a key actor in this landscape. There is little research on the impacts of SMM,7 although anecdotal reports suggest there is risk of adverse effects, such as discriminatory treatment of students from marginalized backgrounds.8

In general, policy efforts related to social media and adolescent health would benefit from bringing schools into the discourse as a key stakeholder group. Moreover, at a national level, there may be benefit to increased coordination between the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Education. The Surgeon General’s letter represented an important call to action, however, joint activities across agencies may produce greater public value and impact,9 particularly on a policy area as complex and historically intractable as mitigating harms from social media. State agencies could also collaborate in this manner. We also suggest other influential bodies involve school leaders and professionals, as well as a diversity of student and parent voices, in stakeholder convenings and policy development. For instance, the open session meetings that informed the NASEM Committee’s report appeared to include few, if any, school leaders or experts in school-based policies. Future work by the NASEM may benefit from amplifying these perspectives.

Understanding the complex interplay between social media use and adolescent health and charting a path forward that minimizes harm and promotes benefits to teens are crucial policy goals. In our view, achievement of these goals may be accelerated by ensuring that schools are represented at the table of key stakeholders along with tech companies, policymakers, researchers, healthcare providers, parents, and youth.

Figure 1.

Schools have been left out of policy discussions related to youth social media use, which misses opportunities to enhance youth mental health.

Funding:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Mental Health grant R01MH129774 “Stakeholder Perspectives on Social Media Surveillance in Schools” (PI Cinnamon Bloss) and the Center for Empathy and Technology of the Institute for Empathy and Compassion at the University of California San Diego.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Social Media and Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Office of the Surgeon General; 2023:1–25. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/youth-mental-health/social-media/index.html

- 2.Galea S, Buckley GJ, Wojtowicz A, eds. Social Media and Adolescent Health. National Academies Press; 2023. doi: 10.17226/27396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NCES Fast Facts: Back-to-school statistics. National Center for Education Statistics. Published 2023. Accessed December 19, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=372

- 4.Dennen VP, Choi H, Word K. Social media, teenagers, and the school context: a scoping review of research in education and related fields. Educ Technol Res Dev. 2020;68(4):1635–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09796-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dix KL, Slee PT, Lawson MJ, Keeves JP. Implementation quality of whole-school mental health promotion and students’ academic performance. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2012;17(1):45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.This Florida School District Banned Cellphones. Here’s What Happened. - The New York Times. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/31/technology/florida-school-cellphone-tiktok-ban.html

- 7.Burke C, Triplett C, Rubanovich CK, Karnaze MM, Bloss CS. Attitudes Toward School-Based Surveillance of Adolescents’ Social Media Activity: Convergent Parallel Mixed Methods Survey. JMIR Form Res. 2024;8(1):e46746. doi: 10.2196/46746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shade LR, Singh R. “Honestly, We’re Not Spying on Kids”: School Surveillance of Young People’s Social Media. Soc Media Soc. 2016;2(4). doi: 10.1177/2056305116680005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office USGA. Government Performance Management: Leading Practices to Enhance Interagency Collaboration and Address Crosscutting Challenges | U.S. GAO. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105520