Abstract

Non-consensual pornography has become a growing concern, with potentially negative consequences for the victims. Victims of revenge porn are more likely to be blamed, and understanding why and how blame is attributed toward victims of non-consensual pornography is crucial to support them and reduce the negative consequences. This study aimed to explore and synthesize the existing evidence on victim blaming in non-consensual pornography and the underlying psychosocial factors within the context of attribution framework. A comprehensive systematic review was conducted across four databases namely PubMed, ProQuest, Google Scholar, and Scopus for English-language studies published from April 2012 to June 2022. Data from the selected studies were extracted and collated into the review matrix. Among the 22 full-text reviews, 10 records that met the eligibility criteria were included in the final review. Two themes namely “Culture and morality” and “gendered differences in attributions of blame” were derived from a thematic synthesis of 10 studies and reflected the psychosocial underpinnings of victim blaming. The review highlighted how cultural narratives and perceived immorality play a major role in how attributions are placed on self or others for victim blaming in “non-consensual pornography.” Blame attributions emerging from gender stereotyping and gendered responsibilization within cultural and societal contexts were found to impact self-blame and compound victimization in non-consensual pornography. The study findings implicated that recognizing psychosocial underpinnings of victim blame attribution in revenge porn would allow for evolving suitable legislative and policy responses for designing effective educative and preventative strategies.

Keywords: Attribution, culture, morality, psychosocial, revenge porn, victim blame

As technology has evolved over the last decade, non-consensual pornography has become a growing concern, with potentially negative consequences for the victims. Non-consensual pornography, often referred to as “revenge pornography,” “revenge porn,” “cyber rape,” “image-based sexual abuse (IBSA),” or “involuntary porn,” is the practice of sharing nude or sexually graphic images of an adult individual without the consent of the person(s) present in the image/video.[1] A multitude of studies show that the sharing or distribution of images without consent can have potentially damaging impact on the victim, in the forms of psychological distress, including anxiety and depression.[2,3] Non-consensual pornography has also been criminalized in several countries as a form of online sexual abuse.[2,4]

Despite legislative laws being in place against non-consensual pornography to discourage potential offenders, it has very limited potential toward addressing victim blame. Victim blame occurs when others judge victims of crime as being responsible for the occurrence of crime.[5] Victim blame in non-consensual pornography is inevitable as the victims have invariable obligation to bear some responsibility for the images that are being shared.[6] Research shows that victims of non-consensual pornography are more likely to be blamed and viewed as sexually promiscuous.[7] Many theories exist to explain victimization in non-consensual pornography.[8] Theories such as victim precipitation from criminology perspectives posit that a crime is initiated by the actions of the victim.[9] Besides harassment, victim blaming also makes the victim believe that he or she will be judged for taking their intimate image in the first place. These, in turn, make it difficult for a non-consensual pornography victim to seek help from the criminal justice system.[10] The other potential consequences of victim blaming include insults and rejection by family members, loss of employment, migration, and even suicides in some instances.[11]

It is thus important to understand why and how blame is attributed toward victims of non-consensual pornography to support them and reduce the negative consequences. As a result, it becomes crucial to investigate the attributions that people make in such situations. Thus, examining victim blaming within an attributional framework will provide a unique insight into the causal explanations for the peoples’ and victims’ behavior in the context of “non-consensual pornography.” Weiner’s attribution framework looks at how people perceive causality or how they judge why a particular event has occurred, and influence the allocation of responsibility and the subsequent behaviors.[12] Such interpretations include inferences of responsibility for an event, such as the assumption that a particular behavior was out of their volitional control or results in judgments about the traits of others involved. In view of the critical role that attributions play in how individuals interpret and respond to victims or victims to themselves and given the relevance of psychosocial factors in attribution,[13] we aimed to explore and synthesize the existing evidence on victim blaming in non-consensual pornography and the underlying psychosocial factors within the context of attribution framework.

METHODS

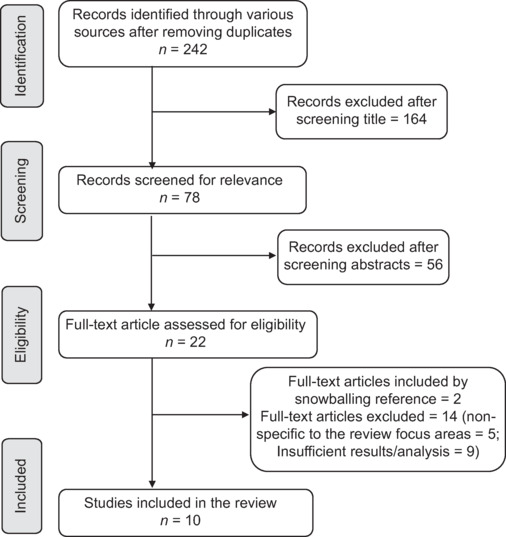

A comprehensive systematic review was conducted, and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for designing, conducting, and reporting the review.

Data sources and search strategy

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted across four databases namely PubMed, ProQuest, Google Scholar, and Scopus. All the databases were searched for English-language entries from April 2012 to June 2022 to synthesize the recent decadal evidence that are relevant to inform the current context. We conducted exploratory searches in Google Scholar and PubMed to develop and refine the list of relevant keywords/search terms and subject headings for the given topic of interest. The keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used for electronic search included Victim, victimization, attribution, attribution theory, non-consensual, revenge, involuntary, image based sexual violence, and technology facilitated sexual violence. The aforementioned keywords were combined with the search terms “porn” and “blame” using the Boolean operator “AND” to restrict the search results to the subject area of investigation. The reference list of primary retrieved articles was snowballed to identify any relevant articles that were missed during the database search [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection for the review

Study selection—inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that are relevant for the review were identified based on the occurrence of the terms “revenge pornography,” “attribution,” “non-consensual,” or “blame” in the title, abstract, or body of the article. The primary variable of interest is “victim blaming in non-consensual pornography examined from attribution perspective,” and the secondary variables are “the psychosocial factors examined from attribution perspective for victim blaming in non-consensual pornography.” Studies were included regardless of the study design (quantitative/qualitative/mixed methods), study setting (online/offline), and country of origin. Peer-reviewed studies with blame and pornography as primary or secondary variables were included. Book chapters, editorials, studies with a sample size of less than 50 (to minimize the influence of selection bias), case series, case reports, review articles, meta-analyses, letters, conference abstracts or posters, credible blog posts, and preprints were all excluded. Gray literature and unpublished data (policy papers, institutional reports, dissertations, and theses) were also excluded because their quality could not be adequately assessed.

Two independent authors conducted the literature search, who screened the titles, abstracts, and keywords based on the review objective. The duplications of the selected articles were removed by exporting their citations to Zotero reference management software. The title and abstracts were screened for relevance, followed by retrieval of the relevant full-text articles for further screening. The retrieved full-text articles were further reviewed for final inclusion based on the eligibility criteria. Consensual agreement between the reviewing authors was used to make decisions concerning study inclusion and data interpretation.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data from the selected studies were extracted and entered into the relevant data field of the review matrix using the following headings: Study title, author, year of publication, measurement tools, research setting, study participants, sample size, study design, and key findings. The full-text articles of final inclusion were distributed among the team members for data extraction after thorough reading. The data extracted from the team members were collated into the review matrix and reviewed to ensure consistency and completeness. A descriptive-analytical framework was used to synthesize the extracted data to provide a coherent and meaningful narrative account relevant to the study topic.

Risk-of-bias assessment in included studies

Two researchers (SA and MKS) independently assessed the quality of the included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for analytic cross-sectional studies.[14] The tool evaluated the included studies for sample characteristics, study setting, exposure, standardization of measurement, confounders, control for cofounders, outcome measures, and analysis. Based on the quality of evidence and the availability of information, the data quality of each study was scored by assigning one point to each applicable item, with a maximum score of 8. The qualitative studies were assessed using the JBI Checklist for Qualitative Research with a maximum score of 10.[15] Each quantitative study was given a rating of good (7–10), fair (4–6), or poor (<4), while each qualitative study was given a rating of good (7–10), fair (5–7), or poor (<5).[16,17,18] After resolving any disagreements, the reviewers agreed on a final score, and no studies were excluded solely based on the quality assessment.

RESULTS

The initial database search yielded a total of 242 studies. Following the exclusion of publications that did not meet the inclusion criteria and after deleting duplicates, a total of 10 studies were included following a full-text review [Figure 1]. By coding the content of each research congruent to the stated objectives, two themes that reflect the psychosocial underpinnings of victim blaming were derived through a thematic synthesis approach. Ten studies were summarized and categorized into these two broad themes: culture and morality and gendered differences in attributions of blame [Table 1]. While the quality of qualitative research ranged from good to fair, that of quantitative studies was in the fair range [Tables 2 and 3]. Most of the studies were cross-sectional in nature, and few of them were conducted on the online platform. Few studies included samples from teachers and female victims. The data collection methods employed in the studies encompassed a variety of tools, including semi-structured interview guides, validated scales, case vignettes, anonymous postings, and recorded firsthand accounts of real experiences.

Table 1.

Summary of studies included in the review (n=10)

| Author (Year) | Sample | Design | Tools | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aborisade, R. A, 2022[19] | 27 adult women victims of revenge pornography | Qualitative analysis | Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews using semi-structured interview guide | • Victims of IBSA were subjected to greater attribution of blames where sexual “double standards” are common in a culturally conservative society. • Institutional re-victimization and self-blame were documented. |

| Mckinlay and Lavis, 2020[20] | 122 participants (mean age=27.6, 76% female) | Online survey method | Scale to measure perceived promiscuity of the victim; single question on blameworthiness of victim; SDSS | • “Revenge porn” victims are susceptible to being victim-blamed. • Individuals with stronger endorsements of traditional gender roles would perceive the female victim as more promiscuous and blameworthy. |

| Zvi, 2021[21] | 560 students aged 19–42 years; mean age=24.32 | Cross-sectional design using 2 × 2 between-participants design | Four vignettes by victims’ sex (male, female) and behavior (self-taken, stealth-taken) presenting the non-consensual distribution of intimate photographs | • Differential treatment toward female and male victims of IBSA. • More blaming and negative feeling were documented toward a female victim whose intimate images were self-taken. |

| Mandau, 2021[22] | 182 posts from an online Danish counseling hotline (86.26% posts by females; mean age=13.63) | Qualitative analysis | Thematic analysis of anonymous posts relating to sharing of private sexual images | • Majority of posts involved behavioral and characterological self-blame, refraining from approaching adults for help. |

| Serpe and Brown, 2022[23] | 359 individuals (52.4% women; mean age=30.57) | Online survey method | Demographic form, Vignette, Competence Scale, Morality Scale, Humanity Scale, Warmth Scale, adapted victim blame measure | • Women are less likely to assign blame on victims than male. • Victims perceived to be less competent, moral, human, and warm were more likely to be the recipients of blame. • Participants consistently rated the perpetrator as most at fault in the vignettes. • No difference between bisexual, straight, and lesbian victims on victim blame. |

| Sciacca et al., 2021[24] | 92 pre-service teachers (75% women; mean age=26.07; 85.9% heterosexual) | Cross-sectional design | IRI; IRMA Scale; Vignettes on different incidents; questions on attribution of blame and feelings of responsibility |

• Participants tended to blame the target more when the self-produced sexual images were shared to seek attention, compared to other contexts. • Positive correlation between attribution of blame and rape myth acceptance. • Older participants attributed more blame to the participants |

| Scott and Gavin, 2018[25] | 239 students (120 men; mean age=20.13) | Cross-sectional design using 2 × 2 × 2 between-participants design | Vignettes with questions on seriousness and responsibility, sexting experience, and demographic information | • Men were more likely to believe the situation was serious when it involved a male perpetrator and a female victim rather than vice versa. • Participants without sexting experience were more likely than participants with sexting experience to believe the situation was serious, and to hold the victim responsible. |

| Starr and Lavis, 2018[8] | 186 participants (75% female; mean age=23.91) | Online survey method | Victim Blame Scale and General Trust Scale | • Victims tended to be blamed less when they were in a 1-year relationship compared with a 1-month relationship. • Mode of image delivery inconsequential in victim blame. • Individuals with higher levels of interpersonal trust showed less victim blame. |

| Gavin and Scott, 2019[26] | 222 UK university students (111 male, 111 females) | Qualitative analysis | Two vignettes (one involving a male victim of a female perpetrator, and the other a female victim of a male perpetrator) with open-ended | • Consent was central in attributing blame to the victim. • Experience of male victims of revenge pornography is trivialized. • Victim control over intimate self-images |

| question regarding responsibility. | played a greater role than gendered assumptions around sexting. | |||

| Attrill-Smith et al., 2021[27] | 342 participants (76 male, 266 female; mean age=39.27) | Online survey method using mixed-groups design | Two videoed accounts of real experiences of revenge porn victims with victim blame questionnaire and direct questions of who was to blame for sharing | • Male reported significantly higher levels of blame. • Higher level of blame was assigned to victims who had shared self-taken. • Sex of victim and mode of shared sexually explicit material (video or image) did not appear to affect levels of victim blame. |

SDSS: The Sexual Double Standard Scale; QMI: Quality of Marriage Index; GMSSEX: Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction

Table 2.

Quality assessment of quantitative studies included in the systematic review

| Name of the study | Inclusion criteria defined? | Subjects and setting described in detail? | Exposure measured reliable/valid? | Measurement of condition standard? | Confounding factors identified? | Confounding factors addressed? | Outcomes measured in a valid way? | Statistical analyses appropriate? | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mckinlay and Lavis, 2020[20] | No | No | N/A | + | + | No | + | + | 4 |

| Zvi, 2021[21] | No | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Serpe and Brown, 2022[23] | + | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 6 |

| Sciacca et al., 2021[24] | No | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Scott and Gavin, 2018[25] | No | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Starr and Lavis, 2018[8] | No | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

| Attrill-Smith et al., 2021[27] | No | No | N/A | + | + | + | + | + | 5 |

N/A—not applicable; +—satisfies the criteria

Table 3.

Quality assessment of qualitative studies included in the systematic review

| Title of the study | Congruity between philosophical, Perspective, and research methodology | Congruity between research question and research methodology | Congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data | Congruity between research methodology and data analysis | Congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results | Locating the researcher culturally or theoretically | Influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa | Representation of participants and their voices | Ethical approval by an appropriate body | Relationship of conclusions to analysis, or interpretation of the data | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aborisade, 2022[19] | + | + | + | + | + | No | No | + | + | No | 7 |

| Mandau, 2021[22] | + | + | No | + | + | No | No | + | No | + | 6 |

| Gavin and Scott, 2019[26] | + | + | No | + | + | No | No | + | + | + | 7 |

+—satisfies the criteria

Culture and morality

Blaming attribution of revenge porn victims happened in the same manner as rape victims through negative evaluation of their morality.[20] Such negative evaluations are plausibly explained by “fundamental attribution error” and “Just world theory” whereby people tend to overestimate personal factors that influence behavior (promiscuity and social deviance) and blame victims for their suffering by perceiving that they are immoral (e.g., “why the picture was taken in the first place?”). Situational factors (committed relationship when the image was shared, permission not given when the image was leaked) are often ignored in the presence of perceived immorality. Further, female victims of revenge porn are often blamed on moral grounds where they are subjected to “sexual double standards” particularly in a culturally conservative society with a conventional, misogynistic regulation of women.[19] Also, those who strongly endorsed the sexual double standard (representing more traditional gender attitudes) viewed victims as more promiscuous and blameworthy than those who had more contemporary perspectives.[20]

Blaming and perceived immorality increased with increased nudity of the image (particularly from women) that was leaked. This disparity in blame is further compounded in a culture where sexual violence against women is normalized due to societal attitudes around gender and sexuality.[19] Moral concern was denied for victims who are objectified (less competent, warmth, moral, and human); objectified victims are perceived as more at fault, and more blame was attributed to them.[23] Also, those with higher levels of rape myth acceptance (victimization in which individuals believe the victim to be responsible for provoking the perpetrator) were found to have higher blaming attributions toward victims of non-consensual pornography.[24] Further, female victims of non-consensual pornography were found to have greater tendency to blame themselves for their victimization, attributing into their own errors, poor decisions, or naïveté.[22] These clearly indicate a broader, culturally embedded understanding of responsibility in the context of sexual victimization.

Gendered differences in attributions of blame

Gender stereotypes influence blame attributions toward victims of revenge porn, and blame attributions varied based on the sex and behavior (self/stealth-taken) of the victim.[21] A female victim whose intimate images were self-taken received the most negative feelings and blame, reflecting a social gender stereotyping where blame attributions and negative feelings are disparate due to differential interpretation of taking nude selfies for male and female victims. On the contrary, women are less prone to place blame and are more likely to have positive compassionate feelings toward victims.[21] Compared with men, women attributed less objectification (higher competency, humanity, and warmth) and lesser blame.[23] Further, the attributions of male victims of revenge pornography are often trivialized than female victims.[26] These clearly reflect the traditional gender roles and double standards to men and women. When it involved a male perpetrator and female victim, the situation was perceived as serious by most men. However, perpetrator–victim sex did not influence women’s perceptions.[25] Men seem to be more accepting of the gender role stereotypes and hence make such attributions. In contrast, a study using videotaped accounts found that men assigned significantly more blame regardless of the victim’s sex,[27] while another study using pre-service teachers found that neither the victim’s nor the attributor’s gender had an impact on the way blame was assigned.[24] In a study with predominant female respondents, blame attributions were found less for female victims who have longer relationship with the perpetrator.[8] Further, women who had high levels of interpersonal trust were more tolerant and gave less blame to the victim.[8] This could be related to defensive attribution theory where victim blaming declines as one’s similarity with the victim increases. This is further reaffirmed where victims of revenge porn had fewer attributions of responsibility by those who had experience with sexting.[25]

Other related factors associated with victim blaming

Additionally, higher victim blaming in non-consensual pornography was found when victim–perpetrator relationship was of shorter duration and there are lower levels of interpersonal trust in the person evaluating the revenge porn incident.[8] Furthermore, victims who were responsible for creating the material themselves received more blame compared to situations where the material was acquired without their knowledge by the perpetrator. This observation aligns with a cognitive bias consistent with the concept of a just world hypothesis. However, it is worth noting that the gender of the victim and the mode of sharing sexually explicit material, whether through video or images, did not seem to have an impact on the level of victim blaming.[27] Also, individuals with higher age, lower levels of empathy, and higher levels of rape myths acceptance tend to attribute higher levels of victim blaming.[24] Likewise, individuals lacking prior experience in sexting were more inclined than those with sexting experience to view the situation as grave and to ascribe blame to the victim.[25] The extent to which the victim controlled their intimate self-images proved more influential than gendered assumptions around sexting. Effective communication between partners engaged in sexting emerged as a significant factor in shaping perceptions of revenge pornography victimization.[26]

DISCUSSION

This review systematically synthesized the existing evidences that examined victim blaming in the context of “non-consensual pornography” from an attribution perspective. The study highlighted how victim blaming is almost seen as “part and parcel” of non-consensual pornography, with several psychosocial elements influencing attributions and consequent victim blaming. The review also highlighted how cultural narratives and perceived immorality resulting from fundamental attribution error, traditional gender attitudes, and sexual objectification play a major role in how attributions are placed on self or others for victim blaming in “non-consensual pornography.” Another significant study finding was the gendered differences in victimizations and blame attributions that emerged from gender stereotyping. The study also indicated how gendered responsibilization within cultural and societal contexts impacts self-blame and compound victimization in non-consensual pornography. Overall, the findings in this review will be crucial to inform evidence-based interventions and drive policy plannings and program deliveries to prevent victimization and protect (potential) victims of non-consensual pornography.

From the review, it can be inferred that victims of revenge porn are vulnerable in the same manner as rape victims for victim blaming. Similar to placing blame on rape victims, potential victims of “revenge porn” are held responsible for their victimization and blaming.[28] This is because the victims were blamed for capturing their image in the first place and their morality was evaluated negatively despite no permission was granted for public dissemination.[29] It is further noted that when nude self-images were captured and shared, consent and acceptance of risk were assumed for victims while attributing blame.[26] Like rape victims, the blame experienced by victims of “revenge porn” can be further explained by “attribution theory” using “fundamental attribution error” and “Just world theory.” The legal literature revealed how the victim’s decision to share the intimate photographs with the perpetrator is viewed as illegitimate or dismissible by the legal systems.[30] It is important to note that such negative attributions and consequent blaming would impede help-seeking behavior, support networks, increase psychological distress, restrict engagement with health services and criminal justice system, and delay recovery for victims.[20,31]

Further, the victim blame in non-consensual pornography is exacerbated by the subjective norms and cultural beliefs. The review highlighted how female victims of non-consensual pornography often seen as blameworthy and more vulnerable for blame attribution particularly in the context of traditional sexual double standard and rape myth acceptance. Despite the fact that the majority of the papers included in this review were from reasonably progressive societies, findings from culturally conservative societies indicated victims of non-consensual pornography (women more often) to experience greater attribution of blame and stigmatization for making themselves vulnerable than victims of rape.[19,32] Further, victim blame in such conserved societies was often found to compound the secondary victimization especially in the presence of weak support and criminal justice system for victims.[19] This clearly emphasizes the need to strengthen advocacy and social support networks for victims of non-consensual pornography besides enhancing enforcement of law.

In the context of non-consensual pornography, the review emphasized the significance of morality and objectification in victim blame. Consensual sharing of photographs is often perceived as objectifiable offense leading to denial of humanness.[23] Consistent with extant literature, the review highlighted the relationship between objectification with negative moral evaluations that result in denial of moral treatment, depersonalization, and enhanced victim blaming.[33,34,35] In general, objectification of women is more pervasive and permeates all spheres of life from the media to interpersonal relationships.[36] This implies that women are more likely than men to be depicted negatively and receive greater blame in the context of consensual pornography. Consistently, this review also emphasized the same conclusions. Surprisingly, a trend of distributing blame to the perpetrator was noted among few individuals.[23] Though this is encouraging and could be attributed to widespread conversations and awareness about sexual violence, focused efforts are required to augment and sustain this positive response to address victim blaming in non-consensual pornography. On the contrary, e-safety campaigns that problematize the victim behavior rather than the perpetrator could increase the blame attributions to the victim.[2,37,38] Given the detrimental effects of objectification on moral evaluation, victim blaming, and well-being, better understanding of the processes is required to foster the development of intervention programs that would help victims to cope with victim blaming and target the perpetrators to challenge the gendered socialization practices and norms that generate sexually objectifying contexts.

Lastly, the review also highlighted gendered differences in attributions of blame. Attributions varied with victims’ sex and behavior, which are closely linked with culture and mortality in non-consensual pornography. Reflecting the perceptions of “traditional gender roles” and “sexual double standard,” men were found to attribute more blaming toward a female (than male) victim and whose intimate images were self-taken (than stealth-taken).[21] Despite the fact that both men and women perpetrate and experience revenge pornography behaviors at comparable levels,[39] the review indicated men were more likely to assign blame to the victims of non-consensual pornography than women. According to male peer support theory, non-consensual pornography is frequently considered a manifestation of gender performativity, a crucial component of which is the degradation and objectification of women.[2] Consequently, such objectification of women victims leads to greater blaming by men.[40] Also, according to the defensive attribution theory, males tend to place greater blame on female victims (particularly when the perpetrator is male) and trivialize male victims, when they more likely to identify themselves with the perpetrator.[41] In fact, research suggests that men sending sexual pictures are often normalized.[42] Contrarily, the same defensive attribution theory explained the lesser blame placed by women particularly those with high interpersonal trust.[8] The differential attributions of blame could be further explained by gender role stereotype or more empathetic, modest, and sociable nature of women.[43] Acknowledging the gendered differences in attributions of blame, the study findings call for a targeted and tailored legal, support, and educational services for both the genders to tackle victim blaming in non-consensual pornography. The review also pointed out additional factors associated with victim blaming. It is important for future research to investigate how these factors affect our perception of revenge porn victimization to gain insights into reducing victim blaming. This research would be essential for guiding and promoting awareness initiatives and the development of programs aimed at supporting victims of non-consensual pornography.

Limitations

There are some noted limitations in this review. The literature search for this review was restricted to studies published in English. Further, the scope of the topic falls into criminology and there was considerable heterogeneity in the terminology used to describe revenge pornography across different studies. Therefore, the possibility of missing out on relevant articles, particularly when search engines indexed with health topics were used primarily, cannot be ruled out. Also, by limiting the inclusion criteria to only peer-reviewed publications and excluding gray literature from this review, it is important to note that the conclusions drawn from the study may not provide a complete and entirely representative reflection of the available evidence. However, the review used a thorough search strategy that covered other language studies (with English-language abstracts) and snowballed the references of retrieved studies to include other relevant articles. It is apparently evident that most of the studies included in the review were derived from English-majority Western population which primarily included young university students. Given the cross-cultural variations and dearth of evidence, the understandings of populations with varying socio-demographic, income, and cultural characteristics are very limited. Further, most of the studies relied on self-report measure than standardized measures using vignettes which could have resulted in social desirability and response bias. Additionally, most of the studies used a sample of females or the vignettes with female as a victim. This irrevocably presents a picture of men not having such experiences, which may not be accurate. Further research should aim to correct these biases and fill the gaps by including broader community samples, expanding the research to various cultural settings, and triangulating perspectives from perpetrators and bystanders to deepen our understanding of victim blaming in non-consensual pornography. With the intent to add depth of understanding and provide a more comprehensive perspective to the topic of interest, we acknowledge the methodological heterogeneity due to inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative studies in this review.

Implications

This review offers directions for a wide range of potential areas for future researches and programs. There can be programs that are developed and successfully implemented to reduce the stigma and blame faced by victims. The role of variables such as interpersonal trust can be used when training legal officers or police officers on how they should be more receptive to the victim, so that the fear of reporting to the police reduces and more trust is established. This can be applied in therapy setting as well. As victim blaming leads to a lot of mental health outcomes, it is important to focus on sexual shaming and blame transference, as these are some of the maladaptive strategies that individuals engage in.

CONCLUSION

The study findings revealed victim blaming as inventible outcome of non-consensual pornography and highlighted the cultural, moral, and gendered contexts associated with victim blaming, similar to rape. Revenge pornography will continue to emerge and normalize as we become more technologically integrated and experience larger shifts in information-sharing behaviors. This calls for increased awareness and action, especially among young people (aged 15 to 29), who are avid technology users and are most likely to become victims. Further research is required on the ways that young people cope with the conflicts that surround intimacy, trust, and sex imagery. Given the similarities to victims of rape and existence of larger gender inequality for women, revenge porn can be conceptualized as a form of gendered, sexualized abuse along the continuum with other forms of sexual violence.[44,45] Such conceptualization along with emphasis on psychosocial underpinnings of victim blame attribution in revenge porn would allow for more suitable legislative and policy responses to be developed toward designing effective educative and preventative strategies that would challenge victim blaming attitudes and safeguard potential victims of revenge pornography.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCue C. Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects: Bridgewater, MA; 2016. Ownership of images: The prevalence of revenge porn across a university population. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry N, Flynn A, Powell A. Responding to ‘revenge Pornography’: Prevalence, nature and impacts. Criminology Research Grants Program, Australian Institute of Criminology; 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamal M, Newman WJ. Revenge pornography: Mental health implications and related legislation. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016;44:359–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGlynn C, Rackley E. Image-based sexual abuse. Oxf J Leg Stud. 2017;37:534–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grubb A, Turner E. Attribution of blame in rape cases: A review of the impact of rape myth acceptance, gender role conformity and substance use on victim blaming. Aggress Violent Behav. 2012;17:443–52. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall M, Hearn J. Routledge: London; 2017. Revenge Pornography: Gender, Sexuality and Motivations. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feather NT. Judgments of deservingness: Studies in the psychology of justice and achievement. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 1999;3:86–107. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0302_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starr TS, Lavis T. Perceptions of revenge pornography and victim blame. Int J Cyber Criminol. 2018;12:427–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timmer DA, Norman WH. The ideology of victim precipitation. Crim Justice Rev. 1984;9:63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bothamley S, Tully RJ. Understanding revenge pornography: Public perceptions of revenge pornography and victim blaming. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2018;10:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franks MA. Drafting An Effective “Revenge Porn” Law: A Guide for Legislators. 2015 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2468823. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol Rev. 1985;92:548–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee D, Gidwani C, Sathyanarayana Rao T. The role of “Attributions” in social psychology and their relevance in psychosocial health: A narrative review. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;36:277–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:179–87. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higginbottom GMA, Hadziabdic E, Yohani S, Paton P. Immigrant women’s experience of maternity services in Canada: A meta-ethnography. Midwifery. 2014;30:544–59. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makhlouf SM, Pini S, Ahmed S, Bennett MI. Managing pain in people with cancer-A systematic review of the attitudes and knowledge of professionals, patients, caregivers and public. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:214–40. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-01548-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poudel P, Griffiths R, Wong VW, Arora A, Flack JR, Khoo CL, et al. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and care practices of people with diabetes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:577. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5485-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aborisade RA. Image-based sexual abuse in a culturally conservative Nigerian Society: Female victims’ narratives of psychosocial costs. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2022;19:220–32. doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mckinlay T, Lavis T. Why did she send it in the first place? Victim blame in the context of “revenge porn.”. Psychiatry Psychol Law. 2020;27:386–96. doi: 10.1080/13218719.2020.1734977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zvi L. The double standard toward female and male victims of non-consensual dissemination of intimate images. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37:NP20146–NP20167. doi: 10.1177/08862605211050109. doi: 10.1177/08862605211050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandau MBH. “Snaps”, “screenshots”, and self-blame: A qualitative study of image-based sexual abuse victimization among adolescent Danish girls. J Child Media. 2021;15:431–47. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serpe C, Brown C. The objectification and blame of sexually diverse women who are revenge porn victims. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2022;34:112–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sciacca B, Mazzone A, O’Higgins Norman J, Foody M. Blame and responsibility in the context of youth produced sexual imagery: The role of teacher empathy and rape myth acceptance. Teach Teach Educ. 2021;103:103354. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott AJ, Gavin J. Revenge pornography: The influence of perpetrator-victim sex, observer sex and observer sexting experience on perceptions of seriousness and responsibility. J Crim Psychol. 2018;8:162–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavin J, Scott AJ. Attributions of victim responsibility in revenge pornography. J Aggress Confl Peace Res. 2019;11:263–72. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attrill-Smith A, Wesson CJ, Chater ML, Weekes L. Gender differences in videoed accounts of victim blaming for revenge porn for self-taken and stealth-taken sexually explicit images and videos. Cyberpsychology: J Psychosocial Res Cyberspace. 2022;15:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bates S. Revenge porn and mental health: A qualitative analysis of the mental health effects of revenge porn on female survivors. Fem Criminol. 2017;12:22–42. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrense-Dias Y, Berchtold A, Surís J-C, Akre C. Sexting and the definition issue. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:544–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Citron DK, Franks MA. Criminalizing revenge porn. Wake Forest L. Rev. 2014;49:345. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assaults victims. J Interpers Violence. 2001;16:1028–47. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Awosusi AO, Ogundana CF. Culture of silence and wave of sexual violence in Nigeria. AASCIT J Educ. 2015;1:31–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Z, Teng F, Zhang H. Sinful flesh: Sexual objectification threatens women’s moral self. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49:1042–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loughnan S, Baldissarri C, Spaccatini F, Elder L. Internalizing objectification: Objectified individuals see themselves as less warm, competent, moral, and human. Br J Soc Psychol. 2017;56:217–32. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loughnan S, Pacilli MG. Seeing (and treating) others as sexual objects: Toward a more complete mapping of sexual objectification. TPM-Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. 2014;21:309–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moradi B, Huang Y-P. Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychol Women Q. 2008;32:377–98. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karaian L. Policing ‘sexting’: Responsibilization, respectability and sexual subjectivity in child protection/crime prevention responses to teenagers’ digital sexual expression. Theor Criminol. 2014;18:282–99. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ringrose J, Harvey L, Gill R, Livingstone S. Teen girls, sexual double standards and ‘sexting’: Gendered value in digital image exchange. Fem Theory. 2013;14:305–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker K, Sleath E, Hatcher RM, Hine B, Crookes RL. Nonconsensual sharing of private sexually explicit media among university students. J Interpers Violence. 2021;36:NP9078–108. doi: 10.1177/0886260519853414. doi: 10.1177/0886260519853414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall M, Hearn J. Revenge pornography and manhood acts: A discourse analysis of perpetrators’ accounts. J Gend Stud. 2019;28:158–70. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kahn AS, Rodgers KA, Martin C, Malick K, Claytor J, Gandolfo M, et al. Gender versus gender role in attributions of blame for a sexual assault. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2011;41:239–51. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ricciardelli R, Adorjan M. ‘If a girl’s photo gets sent around, that’s a way bigger deal than if a guy’s photo gets sent around’: Gender, sexting, and the teenage years. J Gend Stud. 2019;28:563–77. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baez S, Flichtentrei D, Prats M, Mastandueno R, García AM, Cetkovich M, et al. Men, women…who cares? A population-based study on sex differences and gender roles in empathy and moral cognition. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0179336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maddocks S. From non-consensual pornography to image-based sexual abuse: Charting the course of a problem with many names. Aust Fem Stud. 2018;33:345–61. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGlynn C, Rackley E, Houghton R. Beyond ‘Revenge Porn’: The Continuum of image-based sexual abuse. Fem Leg Stud. 2017;25:25–46. [Google Scholar]