Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sarcopenia and malnutrition are frequently found in cirrhosis, arising from a confluence of factors such as increased energy requirements, catabolism, systemic inflammation, reduced nutrient intake, altered metabolism, etc. Both conditions contribute to a functional decline that can lead to frailty, decreased quality of life, and an overall poor prognosis in cirrhosis; consequently, nutrition therapy is essential for improving body composition as well as nutritional and functional status.1,2

NUTRITION PRINCIPLES IN CIRRHOSIS

General recommendations

Total energy expenditure in cirrhosis is variable and can range from 28 to 38 kcals/kg/dy. While indirect calorimetry is the preferred and most accurate method to assess energy expenditure, it is often unavailable, resulting in prediction equations or rapid formulas being employed instead. Current recommendations from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines suggest providing at least 35 kcals/kg/d,1,3 while the recent guidelines from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) suggest 30–35 kcals/kg/d.4 A practical approach could be to start with 30 kcals/kg/d in compensated patients without malnutrition and 35 kcals/kg/d in decompensated patients.

Protein requirements range between 1.2 and 1.5 g/kg. The inclusion of both animal and vegetable protein is advised; a general recommendation is to include 50% of vegetable protein and 50% of animal protein (25% from dairy and 25% from any type of meat, preferably white meats). This would ensure a balanced amino acid profile with high-quality protein, fiber, and the provision of diverse micronutrients.5 Certain conditions, such as severe sarcopenia, critically ill patients and patients with HCC, or cholangiocarcinoma might require a higher protein intake, potentially up to 1.8–2.0 g/kg.4,6

Frequent small meals throughout the day and avoiding prolonged fasting periods has shown to improve malnutrition. Additionally, the inclusion of late-evening snacks containing complex carbohydrates and protein has demonstrated to improve muscle mass and energy metabolism.1,2

Micronutrient deficiencies are common in patients with cirrhosis, warranting at least 1 evaluation and, if feasible, subsequent monitoring after repletion. Given the prevalence of low vitamin D across cirrhosis etiologies, routine assessment and repletion is recommended. Pragmatic supplementation based on clinical signs for high-risk patients can be beneficial. For instance, zinc supplementation may help patients with dysgeusia. Patients with alcohol-associated liver disease or those with prolonged decreased energy intake may benefit from B vitamins (B1, B6, and B12) supplementation, especially to prevent refeeding syndrome. And patients with cholestatic etiologies may benefit from fat-soluble vitamins.7 Additionally, AASLD guidelines recommend the pragmatic use of multivitamin supplements for short-term periods, especially in patients with poor nutritional intake.1

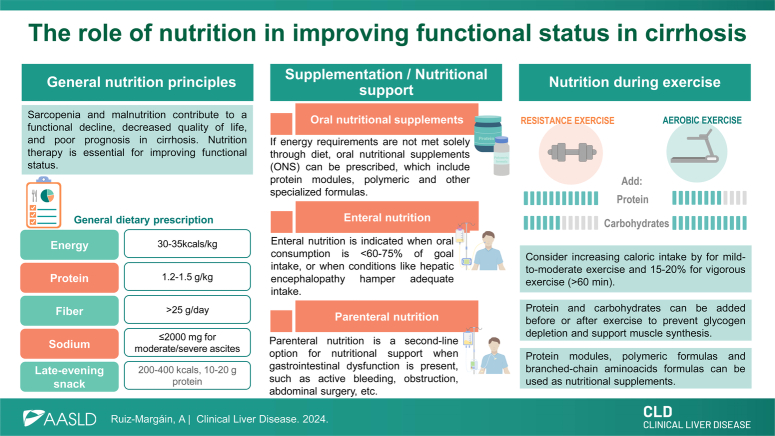

General nutritional recommendations are outlined in Figure 1, and more specific recommendations on the nutritional management of cirrhosis-related complications are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

General dietary recommendations for nutritional management in cirrhosis. Abbreviations: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; ESPEN, European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism.

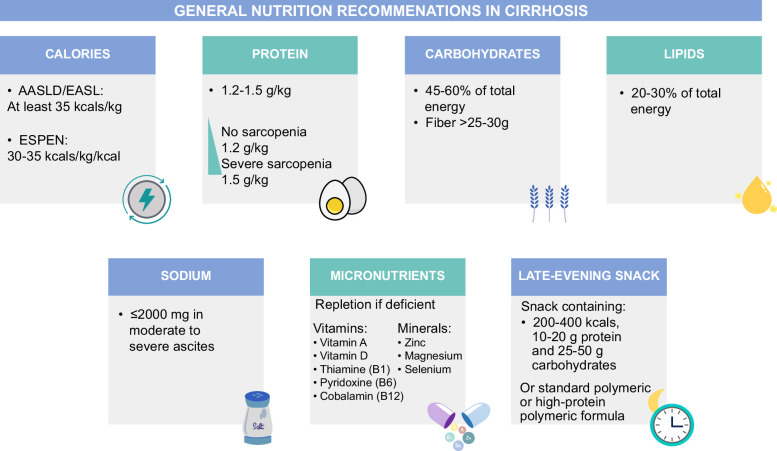

FIGURE 2.

Recommendations for nutritional management for specific clinical scenarios in cirrhosis.

Special considerations in obesity

In patients with obesity, depending on the degree, a range of 20–30 kcals/kg is recommended. An alternative approach is the use of the Mifflin-St. Jeor prediction equation to estimate energy needs, and indirect calorimetry is particularly beneficial in these cases, given that numerous studies have demonstrated the variable energy requirements among individuals with obesity.8

Dietary intervention should result in a mild to moderate caloric restriction with the aim of decreasing body weight, with benefits such as improved mobility, and decrease in portal hypertension. While promoting weight loss, it is essential to focus on adequate protein intake to prevent loss of muscle mass. Dietary adjustments include an increase in protein with the parallel decrease in carbohydrates. Protein for patients with body mass index 30–40 kg/m2 can range from 1.5 to 2.0 g/kg, and for patients with body mass index >40 kg/m2 up to 2.5 g/kg can be considered.3,4,9

ORAL, ENTERAL, AND PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Oral supplementation

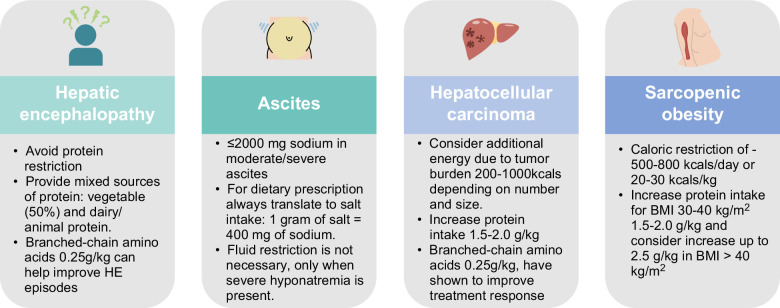

When patients are unable to meet their energy requirements through regular diet, oral nutritional supplements can be prescribed. Several nutritional supplements are available, and Figure 3 outlines their recommended use.7 For additional details on available nutritional formulas, the Enteral Nutrition Formula Guide from the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) can be consulted.10

FIGURE 3.

Suggested use of oral/enteral nutritional supplements for sarcopenia management for different complications and comorbidities. Abbreviation: BCAA, branched-chain amino acids.

Enteral nutrition

Enteral nutrition (EN) is regularly used in cirrhosis. The main indication for EN is the inability of patients to meet their energy needs by oral intake, and this is regularly seen in decompensated patients due to decreased appetite, early satiety, HE, etc.

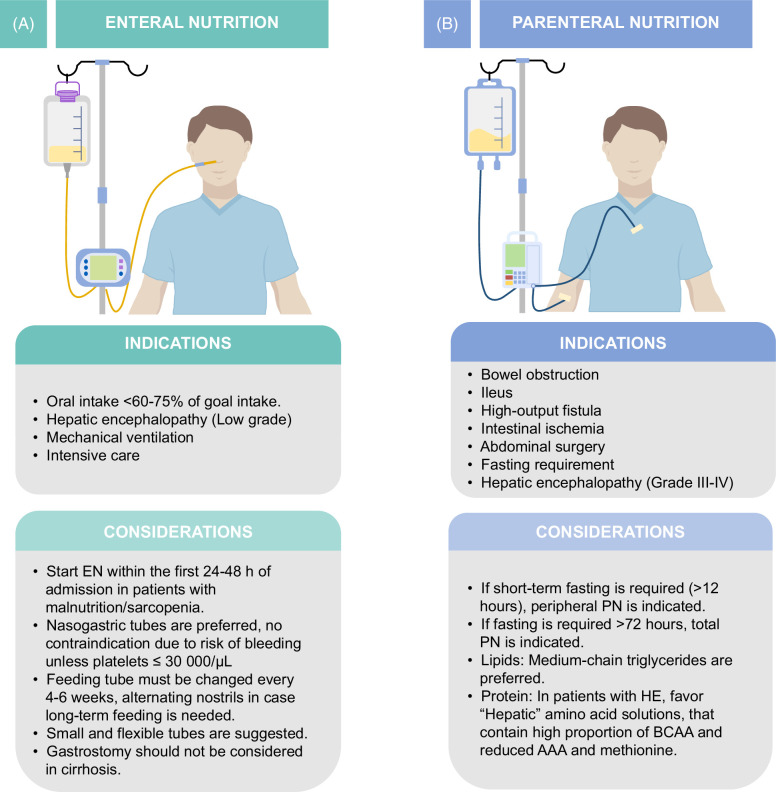

Enteral nutrition (EN) should be considered when energy intake consistently falls between 65% and 75% of energy requirements for over 7 days, even with oral nutritional supplements. Furthermore, if oral intake is <65% of the required energy, EN should be considered mandatory; for hospitalized patients not meeting this requirement, EN should be started early, ideally within 24–48 hours of admission. For outpatients with inadequate energy intake, home EN should also be considered. Other indications and considerations regarding EN in cirrhosis are found in Figure 4A.4,6,7,11

FIGURE 4.

Indications for enteral nutrition (A) and parenteral nutrition in cirrhosis (B). Abbreviations: AAA, aromatic amino acids; BCAA, branched-chain amino acids; EN, enteral nutrition; PN, Parenteral nutrition.

Parenteral nutrition

Parenteral nutrition (PN) is considered as a second-line option for nutritional support and is indicated when EN is not feasible due to gastrointestinal dysfunction. Indications and considerations regarding parenteral nutrition in cirrhosis are shown in Figure 4B.1,12

NUTRITIONAL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR EXERCISE

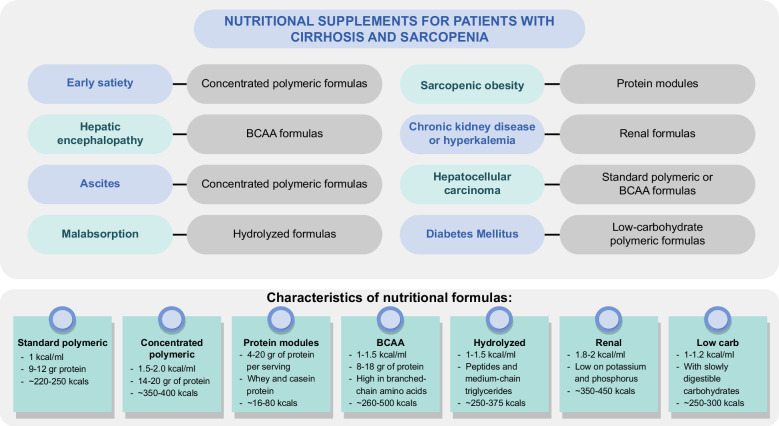

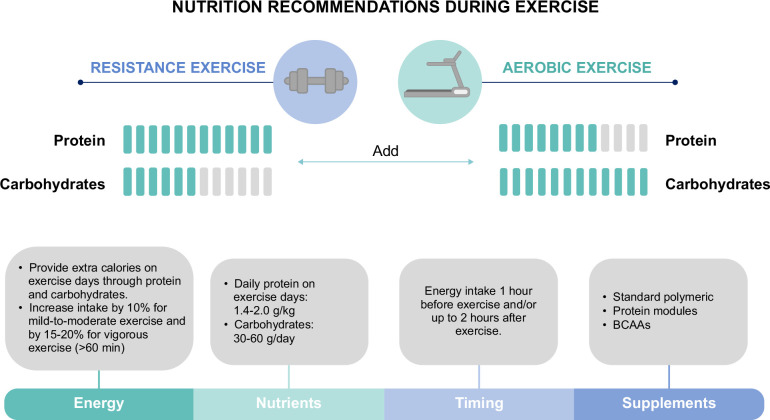

For patients engaging in an exercise program, dietary modifications are essential; inadequate nutrition when exercising can lead to loss of muscle mass, weight loss, and fatigue. Additional substrates are necessary during exercise, and 3 main components need to be considered: energy, protein, and carbohydrates. A summary of nutritional recommendations is outlined in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Nutritional recommendations for exercise interventions in patients with cirrhosis. Abbreviation: BCAA, branched-chain amino acids.

Energy

The provision of extra calories depends on the type of exercise performed. For patients with sarcopenia and malnutrition, additional 10%–20% of caloric intake may be required. Conversely, in patients with obesity, to promote weight loss, this increase in calories is not recommended.13

Protein

Protein is necessary for muscle protein synthesis and to increase the number of muscle fibers. Protein intake has shown benefits both before and after exercise, and before sleep, therefore the inclusion of a late-evening snack is also recommended for exercising patients.14

During days of exercise, a protein range of 1.4–2.0 g/kg/d is recommended depending on the type and duration. The inclusion of essential amino acids is necessary to stimulate protein synthesis, including at least 1 g of leucine daily.15

The use of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) during exercise has been extensively studied, particularly in the general population and athletes, and it is broadly recommended. The available studies indicated that BCAAs can decrease postexercise muscle damage markers and muscle soreness. In the context of cirrhosis, the recommended dose of BCAAs is 0.25 g/kg.4,16

Carbohydrates

Glycogen storage in the liver and muscles is impaired in cirrhosis due to altered metabolism and sarcopenia; therefore, carbohydrates have a crucial role in exercise. Depleted glycogen levels can lead to hypoglycemia, decreased exercise tolerance, and increased tissue breakdown.

Carbohydrate intake is beneficial before exercise to increase performance and after exercise to restore muscle glycogen. There is no specific recommendation for patients with cirrhosis; however, the suggested carbohydrate intake for general population performing exercise ranges from 5 to 7 g/kg, whereas for athletes, the range is 8–10 g/kg. This could translate to extra 30–80 g/d, depending on the duration and type of exercise.14

Supplementation during exercise

Selecting a snack or supplement for exercising patients depends on the goal of the exercise program, especially whether weight loss is a desired outcome or not and depending on the presence and degree of sarcopenia.

For most patients, the combination of protein and carbohydrate intake would be recommended, as it helps to achieve greater endurance, muscle hypertrophy, faster exercise recovery, and reduction in muscle damage compared to the effects observed with protein or carbohydrates alone. This combination can be provided either as a food snack or through the inclusion of nutritional supplements.15

In patients with obesity where the goal is to achieve weight loss with muscle mass preservation or increase, the inclusion of powder protein modules is the best option for maintaining and gaining muscle mass without increasing energy intake.

Muscle cramps

Muscle cramps are a frequent complaint in patients with cirrhosis. Although the evidence is still limited, certain nutritional strategies may help reduce both the frequency and intensity of these cramps. Ensuring adequate hydration, especially during physical activity, is essential to prevent muscle cramps. Additionally, dietary interventions such as zinc supplementation (440 mg zinc sulfate) and BCAAs (6–12 g/d) have shown to reduce or resolve muscle cramps, and a recent study found that pickle juice is effective in reducing the severity of muscle cramps.17,18

CONCLUSIONS

A multidisciplinary approach is essential in the management of cirrhosis. The aim of nutritional therapy is to supply adequate energy, macronutrients, and micronutrients to improve sarcopenia and functional status, to help manage complications, and to enhance exercise interventions.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts to report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; ASPEN, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; BCAA, branched-chain amino acids; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; EN, enteral nutrition; ESPEN, European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lai JC, Tandon P, Bernal W, Tapper EB, Ekong U, Dasarathy S, et al. Malnutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis: 2021 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;74:1611–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duarte‐Rojo A, Ruiz‐Margáin A, Montaño‐Loza AJ, Macías‐Rodríguez RU, Ferrando A, Kim WR. Exercise and physical activity for patients with end-stage liver disease: Improving functional status and sarcopenia while on the transplant waiting list. Liver Transplant, 24:122–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Merli M, Berzigotti A, Zelber-Sagi S, Dasarathy S, Montagnese S, Genton L, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;70:172–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Plauth M, Bernal W, Dasarathy S, Merli M, Plank LD, Schütz T, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:485–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, Cordoba J, Kato A, Montagnese S, et al. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International society for hepatic encephalopathy and nitrogen metabolism consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennett AR, Olson JC. Nutrition management in the critically ill patient with cirrhosis. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2020;19:30–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasse JM, Dicecco SR. Enteral nutrition in chronic liver disease: Translating evidence into practice. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30:474–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Madden AM, Mulrooney HM, Shah S. Estimation of energy expenditure using prediction equations in overweight and obese adults: A systematic review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016;29:458–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, Warren MM, Johnson DR, Braunschweig C, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr . 2016;40:159–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ASPEN | Enteral Nutrition Formula Guide . Accessed March 29, 2024. https://www.nutritioncare.org/Guidelines_and_Clinical_Resources/EN_Formula_Guide/Enteral_Nutrition_Formula_Guide/.

- 11. Plauth M, Schuetz T, Escuro A, Grenda B, Johnston T, Kozeniecki M, et al. When is enteral nutrition indicated? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2022;46:1470–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Plauth M, Schuetz T. Working group for developing the guidelines for parenteral nutrition of The German Association for Nutritional Medicine. hepatology - guidelines on parenteral nutrition, chapter 16. Ger Med Sci. 2009;7:Doc12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aragon AA, Schoenfeld BJ, Wildman R, Kleiner S, VanDusseldorp T, Taylor L, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Diets and body composition. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kerksick CM, Arent S, Schoenfeld BJ, Stout JR, Campbell B, Wilborn CD, et al. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Nutrient timing. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jäger R, Kerksick CM, Campbell BI, Cribb PJ, Wells SD, Skwiat TM, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017;14:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salem A, Trabelsi K, Jahrami H, AlRasheed MM, Boukhris O, Puce L, et al. Branched-chain amino acids supplementation and post-exercise recovery: an overview of systematic reviews. J Am Nutr Assoc. 2024;43:384–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vidot H, Carey S, Allman‐Farinelli M, Shackel N. Systematic review: the treatment of muscle cramps in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:221–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tapper EB, Salim N, Baki J, Zhao Z, Sundaram V, Patwardhan V, et al. Pickle juice intervention for cirrhotic cramps reduction: The PICCLES randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:895–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]