Abstract

Gram-negative bacteria from the Bacteroidota phylum possess a type-IX secretion system (T9SS) for protein secretion, which requires cargoes to have a C-terminal domain (CTD). Structurally analysed CTDs are from Porphyromonas gingivalis proteins RgpB, HBP35, PorU and PorZ, which share a compact immunoglobulin-like antiparallel 3+4 β-sandwich (β1–β7). This architecture is essential as a P. gingivalis strain with a single-point mutant of RgpB disrupting the interaction of the CTD with its preceding domain prevented secretion of the protein. Next, we identified the C-terminus (‘motif C-t.’) and the loop connecting strands β3 and β4 (‘motif Lβ3β4’) as conserved. We generated two strains with insertion and replacement mutants of PorU, as well as three strains with ablation and point mutants of RgpB, which revealed both motifs to be relevant for T9SS function. Furthermore, we determined the crystal structure of the CTD of mirolase, a cargo of the Tannerella forsythia T9SS, which shares the same general topology as in Porphyromonas CTDs. However, motif Lβ3β4 was not conserved. Consistently, P. gingivalis could not properly secrete a chimaeric protein with the CTD of peptidylarginine deiminase replaced with this foreign CTD. Thus, the incompatibility of the CTDs between these species prevents potential interference between their T9SSs.

Keywords: periodontal disease, bacterial virulence factor, infectious disease, protein secretion, X-ray crystal structure, T9SS

1. Introduction

The interface between bacteria and their extracellular environment is permeated by secretion machineries, which are multiprotein gateways for the transport of cargoes from the cytosol across the cytoplasmic inner membrane (IM; ‘protein export’) and, when present, outer membrane (OM; ‘protein secretion’) [1–4]. These systems are critical for bacterial viability at a site of infection or colonization as they serve nutrient acquisition and communication with other bacteria, often across species barriers [2,3]. They further enable bacterial adhesion to biofilms, S-layer formation and gliding motility, as well as the secretion of virulence factors to disarm host defences and competing bacteria at the site of colonization/infection [3–5]. One of the 11 secretion systems [3] that are currently known to exist is the type-IX secretion system (T9SS) [6], which was earlier known as the ‘PerioGate’ and ‘Por Secretion System’ [7–9]. It is widely found in the Gram-negative Bacteroidetes (synonymous with Bacteroidota) phylum of the ‘FCB superphylum’ [10], and sequences of T9SS core proteins have been identified in the genomes of 90 species of this phylum, with the notable exception of Bacteroides spp. [11]. T9SSs may also be present in other FCB phyla [12], including Chlorobiota, Ignavibacteriota, Rhodothermota, Gemmatimonadetes, Cloacimonadota and Fibrobacterota [6,11,13–15]. Remarkably, T9SS genes are absent from other bacterial phyla, archaea and eukaryotes [11].

T9SSs or their component proteins have been experimentally studied from Candidatus paraporphyromonas polyenzymogenes; Capnocytophaga ochracea; Cellulophaga algicola and Cellulophaga omnivescoria; Cytophaga hutchinsonii; Dyadobacter sp.; Fibrobacter succinogenes; Flavobacterium columnare, Flavobacterium johnsoniae, Flavobacterium collinsii, Flavobacterium spartansii and Flavobacterium psychrophilum; Parabacteroides distasonis; Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella melaninogenica; Porphyromonas gingivalis; Riemerella anatipestifer; Roseithermus sacchariphilus; Sporocytophaga myxococcoides; Tannerella forsythia; and Tenacibaculum maritimum [4,7,9,11,14,16–35]. Many of these species infect animals, among which P. gingivalis and T. forsythia are human periodontopathogens that proliferate in the gingiva under dysbiotic conditions of the oral microbiome. Together with Treponema denticola, they form the ‘red complex’ [36] that causes grievous gingivitis and periodontal disease, which affects an estimated 750 million people worldwide in its severe form and is the sixth most prevalent disabling health condition [37–40].

The T9SS is a specialized OM shuttle of protein cargoes that includes a rotary motor, a translocon, an OM-associated scaffold and an attachment complex [4,41]. It operates in conjunction with the general secretory (Sec) pathway for the previous export of cargoes from the cytosol across the IM [4,41]. Once in the periplasm, the N-terminal Sec signal peptide is removed, and cargoes fold and are escorted to the T9SS translocon for secretion. The best-characterized T9SSs are from F. johnsoniae and P. gingivalis [4,7,9,28]. In the latter, it is the major protein secretion pathway and is conformed or regulated by at least 24 ‘Por’ proteins [4,9,41]. It secretes >35 cargo proteins, which include essential virulence factors for infection such as the gingipain cysteine peptidases Kgp, RgpA and RgpB [42]; Porphyromonas peptidylarginine deiminase (PPAD) [8,43]; a 70 kDa metallocarboxypeptidase (CPG70) [44]; and a 35 kDa haemin-binding protein (HBP35) [27].

T9SS transport requires a C-terminal domain (CTD) of 70–100 residues, also known as the ‘T9SS signal’ [16,17,41,45–50], which contrasts with the short unstructured signal peptides of other secretion systems [2,51]. In fact, all Bacteroidetes species potentially encompassing a T9SS also encode putative cargo proteins featuring a CTD and, vice versa, species lacking T9SS genes also miss-predicted proteins with a CTD [11]. Thus, T9SS cargoes are also dubbed ‘CTD proteins’ [46,52]. In P. gingivalis, the CTD is generally chopped off during or after OM translocation by the C-terminal T9SS signal peptidase PorU [53], which operates within an ‘attachment complex’ with PorQ, PorV and PorZ [4,41,54], and cargoes are released to the environment. In a subset of them, however, anionic lipopolysaccharide provided by PorZ is attached to the new C-terminus by PorU, which thus also acts as a sortase-type transpeptidase [53,55,56]. These cargoes are anchored to the extracellular side of the OM [17,57–60]. Notably, some T9SS constituents that are themselves secreted, such as PorA, PorU and PorZ, also possess a CTD, which, however, is not removed upon secretion [5,41,61]. Thus, there are PorU-processed and PorU-unprocessed CTDs.

The CTD is apparently necessary and sufficient for T9SS secretion [4,11,52,62]. Moreover, CTDs are functionally exchangeable between cargoes within a given species, as shown for P. gingivalis Kgp with the CTD of RgpB [45]. What is more, the CTDs of P. gingivalis cargo proteins RgpB, PPAD, CPG70 or P27 fused to a green fluorescent protein caused the resulting chimaeras to be secreted and anchored to the OM by this bacterium [45,52]. In F. johnsoniae, the same fluorescent protein and mCherry, furnished with the CTD of the RemA adhesin [11] or the ChiA chitinase [47], were secreted by the T9SS. CTDs may also function across species within Bacteroidetes, as shown for the Flavobacteriia class. Indeed, C. algicola AmyA α-amylase was secreted by the T9SS of F. johnsoniae [11]. Across classes, the latter translocon recognized the CTD of C. hutchinsonii (class Cytophagia) Cel9B cellulase but not that of P. gingivalis (class Bacteroidia) RgpB [11]. Moreover, the CTD of C. hutchinsonii Cel9A cellulase is required to be N-glycosylated in the periplasm prior to secretion and cell-surface exposure in what resembles an additional step of regulation in this species [63]. Overall, these findings pinpoint species-specific differences across the T9SS signals and disparate interspecific compatibility.

Although CTDs have been classified into types A, B and C, sequence identities are generally very low and there are no obvious motifs attributable to cargo translocation and/or cleavage through the C-terminal T9SS signal peptidase [4,11]. This has fuelled the hypothesis that conserved structural elements rather than sequence stretches may be responsible for function [11]. In this sense, the structures of the CTDs of RgpB [49,64] and HBP35 [27], which are removed upon secretion, as well as those of the non-cleaved CTDs of PorZ [5] and PorU [41], have been determined. All correspond to P. gingivalis proteins and no CTDs from other species have been reported to date.

Here, we sought to identify molecular determinants for T9SS secretion and PorU-cleavage in P. gingivalis by comparing the four aforementioned structures with two ad hoc high-confidence homology models and verified them with a cohort of mutant strains that were subjected to cellular and functional assays. Furthermore, we determined the crystal structure of the CTD of the T. forsythia T9SS cargo mirolase [65] (dubbed ‘LKK’; from L706 to K–K791, see UniProt entry (UP) A0A0A7KVG3 for residue numbering), the first outside P. gingivalis, and assessed if the above structural determinants were conserved across species. Finally, we checked the CTD compatibility of T. forsythia and P. gingivalis.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Molecular determinants of P. gingivalis C-terminal domains for T9SS function

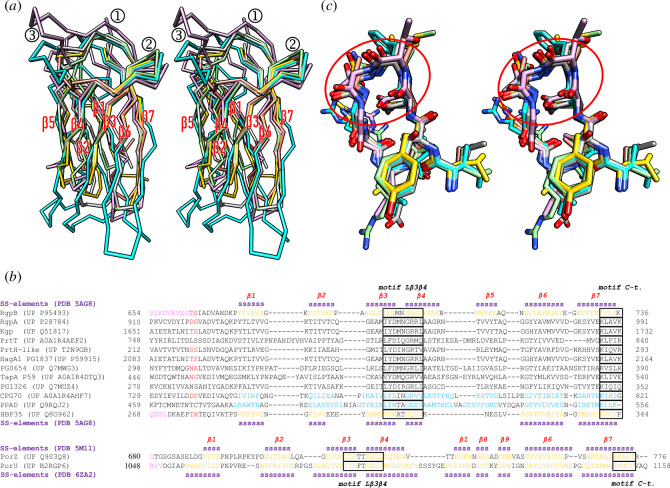

We compared the CTD structures of PorZ [5], PorU [41], HBP35 [27] and RgpB [49] with the calculated high-confidence comparative models (see §3.10) of the CPG70 and PPAD CTDs (figure 1a). We found that the general topology and connectivity, as first described for RgpB [49], were maintained. All molecules consisted of a central immunoglobulin-like moiety [66–68], which features an antiparallel seven-stranded β-sandwich with a four-stranded (β4–β3–β6–β7) and a three-stranded (β5–β2–β1) β-sheet, with intersheet angles of ~30–40°C and Greek-key strand connections (figure 1a). However, with the exception of the loop connecting strands β3 and β4 (Lβ3β4), each structure displayed large variations in the length of the strands and the connecting loops, which led to rather high rmsd and low sequence-identity values in pairwise comparisons (table 1). We then performed a structure-assisted sequence alignment and included a total of 12 CTDs from reported P. gingivalis cargoes, which confirmed the lack of significant sequence similarity (figure 1b). We found that PorU-processed cargoes are generally shorter and span 67–88 residues from the predicted/determined PorU cleavage site [50,53,55] to the C-terminus, while PorZ and PorU encompass 96 and 108 residues, respectively. Thus, CTDs significantly vary in length.

Figure 1.

Structural comparison of P. gingivalis CTDs. (a) Overall superposition in cross-eye stereo of the Cα-traces of the non-cleaved CTDs of PorU (Protein Data Bank (PDB) access code 6ZA2; A1054–Q1158, for UP codes, see (b); cyan) and PorZ (PDB 5M11; E688–R776; plum), as well as of the cleaved CTDs of RgpB (PDB 5AG8; K672–K736; light green), HBP35 (PDB 5Y1A; P287–P344; salmon), CPG70 (predicted model; Q746–G821; gold) and PPAD (predicted model; K476–K556; dark grey). The seven consensus strands are labelled β1–β7, as well as the two essential structural motifs for T9SS function (①, motif C-t. and ②, motif Lβ3β4) and the non-functional β-hairpin within Lβ5β6 (③). (b) Structure-based sequence alignments of the cleaved CTDs of selected cargoes (top alignment) and the non-cleaved CTDs of PorZ and PorU (bottom alignment). The respective UP access codes and flanking residue numbers are provided. Residues in β-strand conformation (‘SS-elements’) according to the respective PDB entries for RgpB and PorZ (above the respective alignment block) and HBP35 and PorU (below the respective alignment block) are displayed in orange. They are earmarked with a magenta ‘s’ and labelled β1–β7. PorU and PorZ have an extra β-ribbon (strands β8+β9) inserted after the fifth strand. Predicted strand residues of the two homology models (CPG70 and PPAD) are in blue. The last residues of the respective upstream domains of structurally analysed proteins are shown in magenta. Determined or putative cleavage sites by PorU are flanked by residues in red [50,53,55]. Motifs Lβ3β4 and C-t. are boxed and are similar to regions B and E of [46]. (c) Superposition in stereo of motif Lβ3β4 (red ellipse, end-on view) from PorU (residues I1090–V1098, carbons in cyan), PorZ (I720–L728, plum), RgpB (I694–V702, light green), HBP35 (V287–V295, tan), CPG70 (L773–V781, gold) and PPAD (L505–V513, grey). The residue numbers correspond to the respective UP entries in (b). The orientation results from that of (a) after successive vertical and horizontal rotations of 120°C and 40°C, respectively.

Table 1.

Pairwise comparison of experimental and predicted P. gingivalis CTD structures.

| PorU | PorZ | RgpB | HBP35 | PPAD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PorZ | 80; 105/89; 3.0; 6 | ||||

| RgpB | 64; 105/65; 3.0; 6 | 61; 89/65; 1.8; 20 | |||

| HBP35 | 29; 105/59; 2.8; 0 | 54; 89/59; 2.3; 22 | 57; 65/59; 2.0; 30 | ||

| PPAD | 77; 105/81; 1.9; 13 | 72; 89/81; 2.0; 10 | 59; 65/81; 2.7; 8 | 54; 59/81; 2.6; 7 | |

| CPG70 | 72; 105/76; 2.4; 15 | 70; 89/76; 2.2; 13 | 60; 65/76; 2.1; 27 | 56; 59/76; 2.7; 9 | 72; 81/76; 1.9; 18 |

For each pair of structures, the number of aligned residues out of the total residues of each protein, the overall rmsd (in Å) and the sequence identity (in %) are indicated.

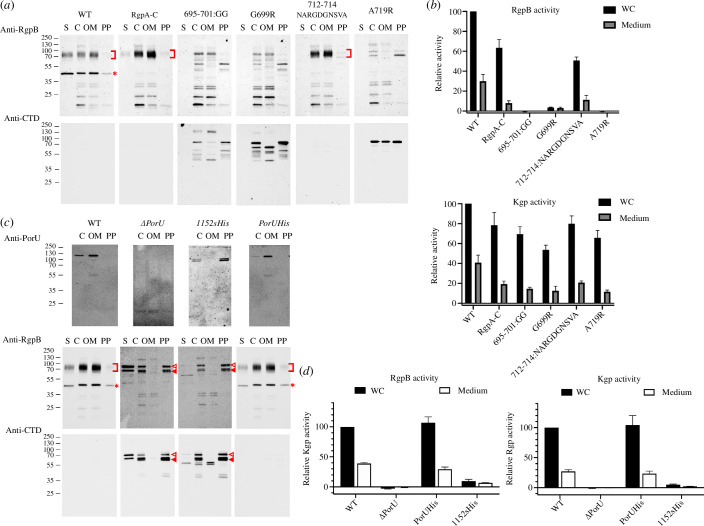

Previous studies with a cohort of 16 point mutations across the CTD of RgpB had revealed no particular residue side chain indispensable for export [69,70]. Thus, we hypothesized that an intact well-folded CTD and, possibly, particular three-dimensional structural motifs would be required for secretion and PorU-mediated cleavage/transpeptidation, as previously suggested [11]. To validate the importance of overall CTD integrity, we identified RgpB residue A719 (numbering according to UP P95493), which is the central residue of the penultimate β-strand β6 of the CTD and is engaged in interactions with the upstream protein domain [49]. We generated a P. gingivalis strain with the alanine replaced with arginine (mutant A719R). To perform such RgpB mutations, we routinely employ the RgpA-deficient mutant strain RgpA-C to prevent the highly homologous rgpA gene from interfering with the genetic manipulation of rgpB and RgpB protein detection [16,71]. We compared the occurrence of the mutant protein in distinct cell-culture fractions and extracellular gingipain activity with those of the wild-type and RgpA-C as positive controls. We found that the mutant protein was not secreted to the OM but accumulated in the periplasm (figure 2a), and the strain lacked extracellular RgpB proteolytic activity (figure 2b). This is indicative of T9SS malfunction for this cargo [16,41,56]. In contrast, Kgp activity was unaffected, which documents the correct function of the T9SS for other cargoes (figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Cell-fraction analysis and proteolytic activity of RgpB and PorU mutant strains. (a) Western blotting analysis of RgpB-mutant strains in the supernatant (S), whole-cell extract (C), outer-membrane (OM) fraction and periplasmic/cytoplasmic fraction (PP) employing polyclonal antibodies against RgpA and RgpB (top row, pAb GP1) or the CTD of RgpB (bottom row). Red square brackets pinpoint membrane-type RgpB and asterisks denote the isolated RgpA catalytic domain. The latter is missing in the RgpA-C strain and the mutants generated with a RgpA-C template. The absence of gingipain activity results from deficient proteolytic processing of the respective zymogens, which require the entire prodomain to be removed and degraded to release activity [56]. (b) RgpB (top panel) and Kgp (bottom panel) activity relative to the wild-type (100%) of the RgpB-mutant strains of (a) in whole-cell (WC) cultures and the culture medium after cell centrifugation. Experiments were performed in triplicate. (c) Western blotting analysis of PorU-mutant strains employing the monoclonal antibody 7G9 against PorU (top row) and the polyclonal antibodies of (a) against RgpB and its CTD (middle and bottom rows). Red square brackets pinpoint membrane-type RgpB; asterisks denote the isolated RgpA catalytic domain; open triangles hallmark the unprocessed, full-length 80 kDa RgpB zymogen including the intact N-terminal prodomain and the CTD; and full triangles designate the N-terminally truncated RgpB zymogen. (d) RgpB (left panel) and Kgp (right panel) activity of the PorU-mutant strains of (c) in whole cultures (WC) and the culture medium after cell centrifugation.

As to particular CTD elements that may be relevant for T9SS function, we identified two structural motifs, ‘motif C-t.’ and ‘motif Lβ3β4’ (figure 1a,b). They are conserved and located on the surface, near the top edge of the domain (figure 1a,c) and, thus, potentially accessible for interaction with the T9SS translocon and subsequent PorU cleavage [41].

2.2. Motif C-t.

Previous studies have underlined the importance of the CTD C-terminal end for function [11]. In particular, the truncation of two residues—but not one—at the C-terminus of RgpB created an inactive variant that is retained in the periplasm [16]. Moreover, the T9SS targeting signal of HBP35 was localized to the last 22 residues of the CTD [52]. Inspection of the superposed CTD structures revealed that the main chains of the C-terminal β-strand coincide (figure 1a), which suggests they may be important for structural integrity and/or function of the whole domain. Moreover, a conserved lysine is found in equivalent positions of strand β7 (figure 1b).

To validate this hypothesis, we constructed and assayed P. gingivalis strains featuring two PorU mutants, in which the last six residues were replaced with hexahistidine (replacement mutant 1152sHis) or eight histidines were added to the C-terminus (extension mutant PorUHis). By using the wild-type and a PorU deletion mutant (ΔPorU) as positive and negative controls, respectively, we found that in the PorUHis mutant, PorU and RgpB were correctly translocated to the OM surface and the CTD of RgpB was properly removed by PorU, as found in the wild-type (figure 2c). Moreover, the mutant evinced extracellular RgpB and Kgp activity indistinguishable from the wild type (figure 2d). In contrast, mutant 1152sHis mimicked the ΔPorU deletion mutant in that RgpB was not exported or processed correctly, so its CTD was still attached (figure 2c). Moreover, mutant PorU protein accumulated in the periplasm. Finally, again, as in ΔPorU, no relevant extracellular RgpB or Kgp activity was detected (figure 2d). Overall, these results indicate general malfunctioning of the T9SS due to aberrant PorU.

Altogether, the findings of the two mutants confirm the importance of the residues constituting the C-terminal motif for translocation, but the C-terminus may be extended without consequences. This is consistent with reports for PorZ, for which elongation of the C-terminus by histidine tags likewise did not cause functional T9SS impairment, but replacement of the last residues with histidines did [5]. Furthermore, extension of the C-terminus by polyhistidine tags, as well as deletion of the last two residues—but not four residues—did not affect the secretion and OM attachment of PPAD. In fact, the CTDs of PorZ and PorU evince one and three extra C-terminal residues, respectively, when superposed onto those of the other cargoes (figure 1a,b).

2.3. Motif Lβ3β4

All CTD models showed an excellent fit of the segment encompassing Lβ3β4 (figure 1a,c), which suggests a possible consensus role in T9SS function. This finding is consistent with a previous deletion mutant of RgpB lacking L692–V702, which suppressed the secretion of this cargo [69]. However, as this mutant had been designed before the structure of the RgpB CTD was available [49], we hypothesized that an internal deletion of 11 residues ablating not only the connecting loop but also most of strands β3 and β4 might have caused the collapse of the entire domain instead of selectively ablating a specific structural element in an otherwise intact scaffold. Thus, we obtained a more conservative structure-based deletion strain that should keep the overall structure well folded, in which F695–D–M–N–G–R–R701 was replaced with two glycines (mutant 695–701:GG). We found that in this mutant, RgpB accumulated in the periplasm and was not secreted and that extracellular RgpB activity—but not Kgp activity—was significantly diminished (figure 2a,b). Moreover, the aforementioned study by Slakeski et al. also reported that replacement in RgpB of the only conserved residue of the Lβ3β4 motif, a glycine (G699) in the first position of the fourth strand (figure 1b), with proline had no significant deleterious effect [69]. We hypothesized that this replacement may not have had a structural impact large enough to cause motif disruption. To verify this, we replaced this glycine with arginine (mutant G699R) and found that this mutation actually hindered RgpB secretion and processing to its active mature form (figure 2a). Moreover, extracellular RgpB activity was ablated (figure 2b). Thus, this glycine is functionally relevant and pinpoints motif Lβ3β4, narrowed down to the encircled region in figure 1c, as essential for CTD recognition and cargo secretion by the T9SS translocon.

2.4. The β-hairpin within Lβ5β6 of PorU and PorZ is functionally not relevant

Upon examining PorU-processed and PorU-unprocessed CTDs for any noticeable variations, we found that PorU and PorZ share an additional β-hairpin at the end of the fifth strand, which is not present in the other four models (figure 1a,b). This protrusion, which accounts for most of the extra residues in the two Por proteins when compared with PorU-processed CTDs, should hamper any functional interaction Lβ5β6 might perform, so we hypothesized that this element might be engaged in PorU binding for cargo processing within the attachment complex. To validate this hypothesis, we constructed a mutant strain in which E712–A–Q714 of RgpB was replaced with N–A–R–G–G–D–G–N–S–V–A (mutant 712–714:NARGGDGNSVA). This mimics the insertion of PorZ except for a serine replacing an arginine (figure 1b). Unexpectedly, we found that in this mutant RgpB was correctly exported, cleaved by PorU and anchored on the surface in a manner indistinguishable from the RgpA-C positive control (figure 2a), and extracellular gingipain activity was not affected (figure 2b). Thus, motif Lβ5β6 is apparently not relevant to distinguish between translocation and PorU processing, so the discerning features between these two functions remain to be determined.

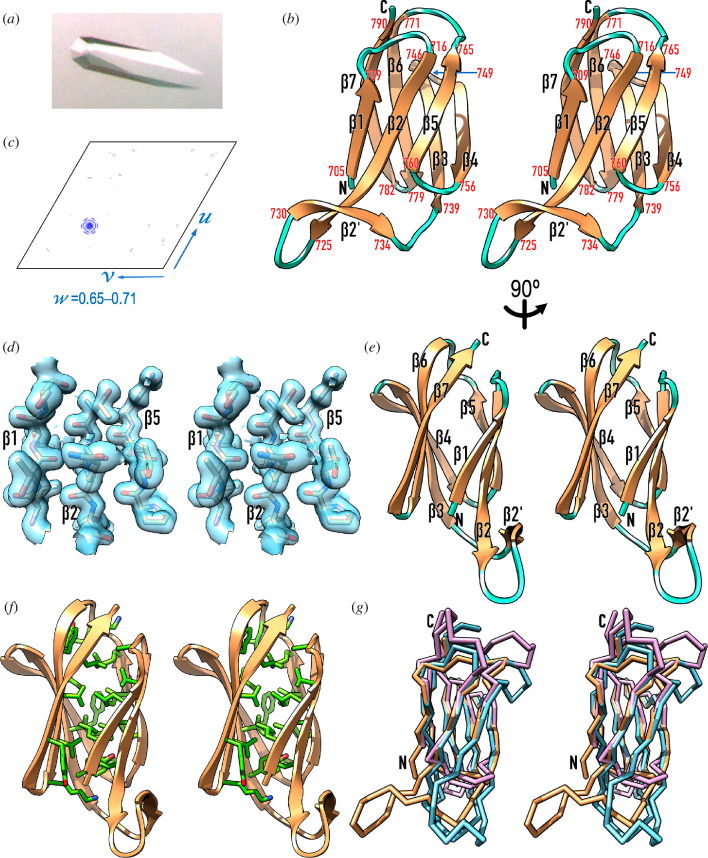

2.5. Crystal structure of a C-terminal domain orthologue from T. forsythia

The LKK protein domain from T. forsythia mirolase was recombinantly produced in Escherichia coli with selenomethionine replacing methionine as an N-terminal fusion with glutathione-S-transferase, and purified by affinity and size-exclusion chromatography steps (see §3.7). After tag removal, the protein was crystallized in the form of well-diffracting trigonal crystals (see figure 3a and table 2). However, structure solution and refinement proved exceptionally difficult owing to the simultaneous occurrence of translational non-crystallographic symmetry (tNCS; figure 3b) and hemihedral twinning, which led to space-group ambiguity (see §3.9). Eventually, the structure was solved in the primitive space group P3121 by single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) with data collected at the selenium K-edge, but it could only be refined in P31 after the diffraction data had been detwinned (table 2). All this notwithstanding, the final structure (figure 3c), with six protomers in the crystallographic asymmetric unit (a.u.), was backed by solid Fourier map density (figure 3d) and exhibited good validation parameters (table 2).

Figure 3.

Crystallographic studies of T. forsythia LKK. (a) Trigonal crystal of space group P31 of selenomethionine-derivatized LKK diffracting to 1.6 Å resolution. (b) Native Patterson map section (axes u, v, w) viewed down the w axis for fraction 0.65–0.71. A peak of 72% the height of the origin peak at fractional coordinates 0.331, 0.663 and 0.678 accounts for strong translational non-crystallographic symmetry, which obscures hemihedral twinning following twin law h,–h–k,–l (estimated twin fraction α = 0.423). (c) Ribbon-type plot in cross-eye stereo of LKK, which encompasses eight β-strands as salmon arrows (β1–β7 plus β2’) connected by coil regions in cyan. The flanking residues of each strand are numbered in red, and the N- and the C-terminus are labelled in black. In this view, the molecule has been rotated vertically ~180° with respect to figure 1a for clarity. (d) Detail of the final σA-weigthed (2mFobs–DFcalc)-type Fourier map, contoured at 1σ above the threshold, centred on the three β-strands (β1, β2 and β5) of the front sheet of molecule A. The final refined model is shown for segments L706–S709, T718–L721 and P759–Q762, approximately in the view of (c). (e) Same as (c) after a vertical 90° rotation. (f) Variant of (e) depicting the side chains that form the hydrophobic core of the LKK moiety, with carbons in light green. The participating residues are L706, L708, A713, V717, L719, L721, Y740, I742, I744, F754, T756, F761, I763, P764, M765, L768, Y773, V775, V777, K779, Y784, L788 and K790. (g) Superposition of LKK as Cα-plot in sandy brown in the view of (c) onto the structures of the PorU (cyan; PDB 6ZA2) and PorZ (plum; PDB 5M11) CTDs.

Table 2.

Crystallographic data.

| dataset | LKK (T. forsythia mirolase CTD, SeMet) |

|---|---|

| beam line (synchrotron) | ID23-1 (ESRF) |

| detector | ADSC Quantum Q315r |

| space group / protomers per a.u.a | P31 / 6 (A–F) |

| cell constants (a and c, in Å) | 81.45, 66.55 |

| wavelength (Å) | 0.91917 |

| no. of measurements / unique reflections | 731 662 / 65 076 |

| resolution range (Å) (outermost shell)b | 48.4–1.60 (1.70–1.60) |

| completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.6) |

| Rmergec | 0.121 (0.954) |

| Rmeasc | 0.127 (0.999) |

| CC(1/2)c | 0.999 (0.943) |

| Average intensityd | 9.0 (2.7) |

| B-factor (Wilson) (Å2) | 23.5 |

| aver. multiplicity | 11.2 (11.1) |

| twinning law | h, -h-k, -l |

| twinning fraction α | 0.423 |

| no. of reflections used in refinement [in test set]e | 64 231 [656] |

| crystallographic Rfactor / free Rfactor | 0.275 / 0.302 |

| Fobs , Fcalc correlation [test set] | 0.933 [0.930] |

| no. of protein residues / atoms / solvent molecules / non-covalent ligands | 518 / 4048 / 476 / 2 K+, 6 Cl−, 6 PEG |

| Rmsd from target values | |

| bonds (Å) / angles (°) | 0.008 / 0.97 |

| average B-factors (Å2): overall // mol. A/B/C/D/E/F | 21.7 // 17.9/22.9/22.2/17.8/22.8/22.0 |

| all-atom contacts and geometry analysisf | |

| protein residues | |

| in favoured Ramachandran regions / outliers / all residues | 503 (98.4%) / 0 / 511 |

| with outlying rotamers / bonds / angles / chirality / torsion | 5 (1.1%) / 0 / 0 / 0 / 0 |

| all-atom clashes / clashscore | 20 / 2.2 |

| PDB access code | 8QB1 |

Abbreviations: a.u., crystallographic asymmetric unit; PEG, diethylene glycol.

Values in parentheses refer to the outermost resolution shell.

For definitions, see [72].

Average intensity is < I/σ(I) > of unique reflections after merging according to Xscale [73].

Refinement was performed against processed data that were subsequently detwinned according to twin-law (h,-h-k,-l) and a twinning factor α = 0.423 with program Detwin within Ccp4.

According to the wwPDB Validation Service: https://wwpdb-validation.wwpdb.org/validservice.

The LKK moiety has an elongated ellipsoidal shape of ~42 Å height, ~26 Å width and ~22 Å depth in the view of figure 3c. As the aforementioned P. gingivalis CTDs, it is an antiparallel β-sandwich with a three-stranded sheet (β1, β2 and β5, from left to right in figure 3c) and a four-stranded sheet (β7, β6, β3 and β4). Two extra N-terminal residues from the purification tag (glycine and serine) replace domain residues L704 and Y705 and form the first residues of strand β1, so that the domain actually spans 88 residues (L704–K791). This lies within the range of cleavable P. gingivalis CTDs (see §2.1). The two LKK sheets are arranged with an intersheet angle of ~35° and have Greek-key connectivity (figure 3c,e). The strands are connected by short loops spanning either two residues (Lβ3β4 and Lβ6β7), three residues (Lβ4β5), five residues (Lβ5β6) or six residues (Lβ1β2). The only exception is Lβ2β3. Here, a further strand external to the central sandwich (β2′) interacts with the elongated tip of strand β2, which gives rise to a 13-residue connector that generates a hairpin-like appendage at the bottom of the sandwich (figure 3c,e). Overall, the moiety is cohered by an internal hydrophobic core made up by 23 residues (figure 3f). Finally, the C-terminal segment of strand β7 encompasses the sequence K787–L–I–K–K791, which is found at the C-terminus of five unique serine- and metal-dependent peptidases secreted by the T9SS of T. forsythia in addition to mirolase, collectively named ‘KLIKK-peptidases’ [65,74]. This conservation is in line with the above sequence requirements of motif C-t. in P. gingivalis, which also includes a conserved lysine in the middle of C-terminal strand β7 (see §2.2).

Structure similarity searches with LKK identified the CTDs of PorZ (Z-score 10.0, rmsd 1.7 Å, 72 aligned residues, 18% identity; see [75]) and PorU (Z-score 9.9, rmsd 1.9 Å, 78 aligned residues, 19% identity) as the closest structural relatives. Contrary to the Tannerella moiety, these Porphyromonas CTDs correspond to non-cleaved forms. Notably, the similarity was significantly lower with the cleavable CTDs of RgpB (Z-score 8.3, rmsd 2.2 Å, 72 aligned residues, 7% identity) and HBP35 (Z-score 6.0, rmsd 2.2 Å, 54 aligned residues, 17% identity). Superposition of LKK onto the PorU and PorZ CTDs (figure 3g) revealed that the topology and connectivity of the sandwich β-strands are maintained but loops largely deviate and pairwise sequence identities span mere 18–19%. In particular, the extended loop Lβ2β3 of LKK is much longer and adopts completely different trajectories in the Por proteins. In contrast, Lβ6β7 and Lβ5β6 are shorter in LKK. The latter is uniquely longer in both PorU and PorZ but is apparently not relevant for function (see §2.4).

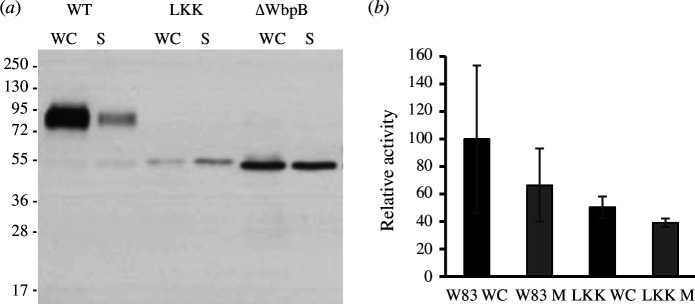

2.6. C-terminal domain interchange between P. gingivalis and T. forsythia

We found that, in addition to the much longer Lβ2β3, LKK lacked one residue in motif Lβ3β4, which is relevant for T9SS function in P. gingivalis (see §2.3), and the conserved glycine was replaced with methionine. Thus, we anticipated specific differences between the T9SSs of the two species, as previously reported for the P. gingivalis and F. johnsoniae pair [11]. We constructed a strain with a replacement mutant of P. gingivalis PPAD, in which the CTD (A474–K556; numbering according to UP Q9RQJ2) was replaced with LKK (D702–K791) to yield mutant PPAD-LKK. We found that this chimaera was not properly secreted and mimicked a strain that cannot anchor cargoes to the OM (figure 4a). Moreover, the mutant strain evinced substantially less extracellular PPAD activity (figure 4b). This confirms that the CTDs are not functionally interchangeable between P. gingivalis and T. forsythia due to the disruption of motif Lβ3β4, despite both species belonging to the Bacteroidia class.

Figure 4.

Cross-species CTD exchange between P. gingivalis and T. forsythia. (a) Western blotting analysis of PPAD export in WC cultures and the culture medium (S) for the wild-type protein (labelled WT) and a PPAD chimaera with LKK as CTD (labelled LKK), as well as for a P. gingivalis mutant strain (ΔWbpB), which does not attach lipopolysaccharide and thus does not anchor substrates to the OM. The chimaera mimics the phenotype of the latter strain, though with a substantially lower yield, which indicates that the protein is not properly secreted. (b) PPAD activity in whole-cell extract and medium for the wild-type protein and the chimaera.

2.7. Conclusion

In an effort to determine molecular determinants for the recognition of the specific T9SS secretion signal, a folded CTD, by the translocon in P. gingivalis, as well as for its cleavage by the C-terminal signal peptidase, we compared six structures. We found the domain’s C-terminus and loop Lβ3β4 to be essential for function. In contrast, we could not determine the distinguishing features between Por-cleaved and PorU-non-cleaved CTDs.

Given that all the reported CTD structures are from P. gingivalis, we determined the structure of a CTD from a T. forsythia cargo, LKK. This module shares the gross architecture with its P. gingivalis counterparts but lacks the specific features of Lβ3β4, and it evinces a substantially longer Lβ2β3. Consistently, the replacement of the CTD of a P. gingivalis cargo with LKK hampered its secretion, which points to specific differences in CTD recognition between the translocons of these two species. This may prevent potential functional interference due to the accidental transfer of cargo genes between two phylogenetically close periodontopathogens, which share the human gingival crevice as an ecological niche, are found in the same biofilm, and compete for resources and thrive at the site of infection [76].

3. Material and methods

3.1. Bacterial culturing

All P. gingivalis mutants were derived from strain W83 (see table 3 for a list of strains and cells used in this study) and were cultured in trypticase soy broth (30 g l−1) enriched with haemin (5 mg l−1), menadione (2 mg ml−1), ʟ-cysteine (0.5 g l−1) and yeast extract (5 g l−1). Solid cultures were additionally supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood, 1.5% agar, and, when antibiotic selection was needed, erythromycin (5 μg ml−1 or tetracycline (1 μg ml−1). Cells were cultivated in an incubator from Don Whitley Scientific at 37°C under anaerobic conditions (10% carbon dioxide, 5% hydrogen and 85% nitrogen). For molecular cloning procedures, E. coli strain DH5α was grown in Luria–Bertani medium (Lennox). Solid cultures in the same medium were prepared with 1.5% agar and supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg ml−1) for antibiotic selection.

Table 3.

List of strains and plasmids.

| strains | description (genotype; resistance) | source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | general cloning host | Thermo Fisher |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) | expression of PorU protein | Millipore |

| P. gingivalis W83 | ||

| WT | wild type | |

| ∆PorU | porU::ermF; Emr | [5] |

| 1152sHis | porU1153-1158::6His, ermF; Emr | this study |

| PorUHis (1158iHis) | porU1158ins8His, ermF; Emr | [41] |

| RgpA-C | RgpA::cat; Cmr | [16] |

| 695-701:GG | RgpA::cat, RgpB 695-701::GG, tetR, Cmr ,Tetr | this study |

| G699R | RgpA::cat, RgpB G699R, tetR; Cmr, Tetr | this study |

| A712-714:NARGDGNSVA | RgpA::cat, RgpB 712-714::NARGDGNSVA, tetR; Cmr,Tetr | this study |

| A719R | RgpA::cat, RgpB A719R, tetR; Cmr, Tetr | this study |

| PPAD-LKK | PPAD 474-556::Mirolase 702:791, tetR; Tetr | this study |

| ∆WbpB | wbpB::tetQ; Tetr | this study |

| plasmids | ||

| p22-E-1158iHis | suicide plasmid for PorUHis (1158iHis) strain generation | [41] |

| pPorU 1152sHis | suicide plasmid for 1152sHis strain generation | this study |

| pRgpB-t | suicide plasmid for RgpB-coding gene modification | [16] |

| pRgpB 695-701:GG | suicide plasmid for 695-701:GG strain generation | this study |

| pRgpB G699R | suicide plasmid for G699R strain generation | this study |

| pRgpB 712-714:NARGDGNSVA | suicide plasmid for 712-714:NARGDGNSVA strain generation | this study |

| pRgpB A719R | suicide plasmid for A719R strain generation | this study |

| pPPAD-tet | suicide plasmid for PPAD-coding gene modification | this study |

| pPPAD-LKK | suicide plasmid for PPAD-LKK strain generation | this study |

| LKK-pGEX6-P-1 | expression plasmid for LKK domain | this study |

| pWbpB-t | suicide plasmid for wbpB gene deletion | this study |

3.2. Subcellular fractionation of P. gingivalis cells

P. gingivalis cultures (controls and mutants) were grown to a stationary phase, and their cell density was adjusted to OD600 ≈ 1.5 with trypticase soy broth. Next, WC cultures were preincubated with 2 mM 2,2′-dithiodipyridine for 15 min and centrifuged (5000×g; 20 min) to separate the cell-free culture medium, which was designated ‘supernatant fraction’ (S). The resulting cell pellets were washed and resuspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with a complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mix (Roche) and 0.2 mM tosyl-ʟ-lysyl-chloromethane hydrochloride (Sigma) and subjected to cell disruption at 30 kPa pressure with a BT40/TS2/AA cell disruptor from Constant Systems. This was followed by 30 min digestion with 0.02 mg ml−1 DNase I (Roche), which resulted in the ‘cell extract’ (C) fraction. The remaining cell lysate was ultracentrifuged at 150 000×g for 1 h and the soluble fraction (‘periplasmic/cytoplasmic’ fraction; PP) was separated from the pellet, which contained the insoluble membrane fraction. IM proteins were solubilized by incubation with 200 mM magnesium chloride and 10% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 30 min and separated by further centrifugation at 150 000×g for 1 h. The remaining insoluble pellet contained OM proteins (‘OM fraction’) and was resuspended by sonication in PBS supplemented with the above protease inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined with the BCA protein assay kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific, and fractions were stored at −20°C.

3.3. Generation of C-terminal domain mutants

Genomic modification of P. gingivalis was performed by homologous recombination with suicide plasmids carrying an antibiotic resistance cassette, as described before [41]. Primers used for PCR reactions are listed in table 4. For RgpB and PorU mutagenesis, the two master plasmids pRgpB-t [16] and p22-E-1158iHis [41] were used, respectively. The desired mutations (RgpB: A719R, 695-701:GG and G699R; PorU:1152sHis) were introduced into the plasmids by standard PCR- and ligase-based methods. For RgpB mutant 712-714:NARGDGNSVA, subcloning of a commercially synthesized 542 bp long fragment of the RgpB gene carrying the desired substitution was performed.

Table 4.

List of vectors and primers (5’→3’) used for mutant generation.

| pPorU1152sHis | |

| P22i6h_Fs | TAGCCTCTAGAATAGCTTCCGC |

| P22i6h_Ft | CACCATCACCATCACCATTAGCCTCTAGAATAGCTTCCGC |

| P22d1129_Rs | TTTCTTGGCCATGGAGGC |

| P22d1129_Rt | ATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGTTTCTTGGCCATGGAGGC |

| pRgpB695-701:GG | |

| RB695GGFnew2 | GGCGTAGCTACTGCTAAAAACCGCATGG |

| RB695GGRnew2 | ACCGATCGTCAGCCCGGCAGCA |

| pRgpBG699R | |

| RgpBG699R_F | GATCTTCGATATGAACCGCCGTGTAGCTACTG |

| RgpBG699R_R | CAGTAGCTACACGACGGCGGTTCATATCGAAGATC |

| pRgpB 712-714:NARGDGNSVA | |

| inRBporZ712F | GCAGGTTACGGCTCCGGCAA |

| inRBporZ712R | GGCTGTGCCGAATGGATTCC |

| vRBporZ712F | TCCATTCGGCACAGCCCTT |

| vRBporZ712R | CGGAGCCGTAACCTGCATT |

| pRgpB A719R | |

| RgpBA719R_F | CAAAACGGCGTGTATCGCGTTCGCATCGCTACTGAAGGC |

| RgpBA719R _R | GCCTTCAGTAGCGATGCGAACGCGATACACGCCGTTTTG |

| pPPAD-tet | |

| pUPPADa_F | GATGATGAATTCCCCAAATACGAAGCAC |

| pUPPADa_R | ATTACCCGGGAATTAAGAATATCAGTGGAG |

| pUPPADb_F | CAGCGTCGACGGGTTATTATTCAAAATCTGAGC |

| pUPPADb_R | TCACTGCAGCTCCGTATAGAGCAGGATC |

| pPPAD-LKK | |

| 749_364_inF | CATGTACTGTGACCGGAGATAATCTTTATCTCACCCTCT |

| 750_364_inR | TTCTCAAATAAGGGGCCTCATTTTTTGATCAATTTCTGC |

| 751_364_vR | TCCGGTCACAGTACATGTATT |

| 752_364_vF | GGCCCCTTATTTGAGAATAC |

| LKK-pGEX6-P-1 | |

| LKK-F | TCAGGGATCCCTCACCCTCTCCCCCAACCCGGC |

| LKK-R | CTGGCTCGAGTTATTTTTTGATCAATTTCTGCGTG |

| pWbpB-t | |

| wbpB_puc19R | GAATTCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTAC |

| wbpBupF | CGACGGCCAGTGAATTCTCGTGTTCGGATTGTATGAAC |

| wbpBupR | GTTAAGGAGATAATTCGTTGTTGTCCTGTTCCTCATTATATCTG |

| wbpBtetF | ACAACGAATTATCTCCTTAACG |

| wbpBtetR | GCCAAGTTCTAATGCTTCTATCACAACGAATTATCTCCTTAACG |

| wbpBdwF | AGAAGCATTAGAACTTGGCAAAAGGAATTCCTATAATCTTATC |

| wbpBdwR | CATGCCTGCAGGTCGACATGATCAAATTCATGAGTATCGC |

| wbpB_puc19F | GTCGACCTGCAGGCATGCA |

For PPAD mutagenesis, master-plasmid pPPAD-tet was designed based on the pUC19 background to introduce a tetracycline resistance gene just after the coding sequence of the ppad gene. The LKK domain was amplified by PCR from T. forsythia genomic DNA. The chimaera of P. gingivalis PPAD (UP Q9RQJ2; residues M1–G473) fused with fragment D702–K791 of T. forsythia mirolase was generated by Gibson cloning. A control strain, ∆WbpB, which is a P. gingivalis strain that does not glycosylate T9SS cargoes but secretes them without attached lipopolysaccharide [77], was generated based on the pWbpB-t suicide plasmid, itself obtained by Gibson cloning based on pUC19.

Generated plasmids were introduced by electroporation into either wild-type P. gingivalis W83 cells (for PorU, PPAD and ΔWbpB modifications) or the ∆rgpA strain of P. gingivalis W83, named RgpA-C (for RgpB modification) and subjected to antibiotic selection. Positive clones were verified by DNA sequencing.

3.4. Proteolytic activity assays

Extracellular gingipain activity was measured as described [41,71], with the chromogenic substrates AcO-K-p-nitroanilide (for Kgp) or PheCO-R-p-nitroanilide (for RgpA/B) at 1 mM in assay buffer (200 mM Tris·HCl, 100 mM sodium chloride, 5 mM calcium chloride, 10 mM ʟ-cysteine and pH 7.6) at 37°C in triplicate. The change in absorbance was monitored at λ = 405 nm in a SpectroMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Enzyme activity was presented as a percentage of the control strain activity.

3.5. Peptidyl arginine deiminase activity

PPAD activity was assayed with N-acetylarginine as the substrate (at 10 mM) in 100 mM Tris·HCl, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.5, as reported [78]. Results were obtained from three independent biological replicates for whole-culture or cell-free-media samples and presented as per cent of the activity of the P. gingivalis wild-type strain. The results of strain ΔWbpB were further presented for completeness.

3.6. Western blot analyses

The distinct subcellular fraction samples of §3.2 were resolved by SDS-PAGE and blotted on nitrocellulose membranes. Unspecific binding was ablated with blocking buffer (5% non-fat skim milk in PBS plus 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20). The primary antibodies mAb 7G9 (for the detection of PorU), as well as pAb GP-1 and anti-CTD (for the detection of RgpB), were diluted in blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C with the blotted samples. Anti-mouse (for anti-PorU blots) or anti-rabbit (for anti-RgpB and anti-CTD blots) horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated IgGs from goat were used as secondary antibodies at 1:20 000 dilution.

3.7. LKK protein production and purification

The coding sequence of LKK, whose boundaries (L706–K791) were designed before the structure of the first CTD was available, was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of T. forsythia strain ATCC 43037 with forward primer LKK-F and reverse primer LKK-R (see table 4). The amplicon was purified and cloned using BamHI and XhoI sites into the pGEX-6P-1 expression vector, which attaches an N-terminal glutathione-S-transferase fusion protein for affinity purification followed by a recognition sequence for PreScission peptidase. The plasmid was verified by sequencing and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) for protein expression. In order to obtain a heavy-atom derivative of the protein, which includes three methionines in its sequence, for structure solution by the SAD method, bacteria were grown in SelenoMethionine complete medium supplemented with SelenoMethionine solution (both from Molecular Dimensions) at 37°C to OD600 = 0.5 and induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-ᴅ-galactopyranoside. After 4 h cultivation at 37°C, cells were harvested by centrifugation (6000×g, 15 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 15 ml wash buffer (PBS with 0.02% sodium azide, pH 7.3) per pellet from 1 l cell culture, and subsequently lysed by sonication (30 × 0.5 s pulses at 70% maximal amplitude per pellet from 1 l culture) using a Branson Sonifier Digital 450 cell disrupter (Branson Ultrasonics). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation (50 000×g, 30 min, 4°C) and applied at 4°C onto a glutathione-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow column (Cytiva) previously equilibrated with wash buffer. After washing out unbound proteins, the protein was released by in-column digestion with PreScission peptidase in wash buffer (0.01 U ml−1) for 40 h at 4°C. The final protein contained the extra N-terminal residues G−4–P–L–G–S−1 from the tag. Protein concentrations were determined through OD280 measured in a NanoDrop microvolume spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the Beer–Lambert law and through the BCA protein assay kit, and protein purity was monitored by SDS-PAGE.

3.8. Crystallization and X-ray diffraction data collection

The selenomethionine derivative of LKK was crystallized by the sitting-drop vapour diffusion method. Reservoir solutions were prepared in 96-deep-well blocks of 2 ml capacity with a Tecan robot. A Phoenix robot (Art Robbins) dispensed drops of 100 nl or 200 nl protein solution (at 19 mg ml−1 in 5 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0) and 100 nl reservoir solution into 96-well 2-drop Swissci PS MRC plates (Molecular Dimensions). Over 1500 conditions from different screenings were assayed at the in-house Automated Crystallography Platform (https://www.ibmb.csic.es/en/platforms/automated-crystallographic-platform). Plates were stored at 4°C or 20°C in Bruker steady-temperature crystal farms with remote access for crystal-growth monitoring. The morphologically best crystals were obtained from drops with 30% polyethylene glycol 2000, 0.1 M potassium thiocyanide as reservoir solution (figure 3a).

Crystals were cryo-protected by rapid passage through drops containing 40% polyethylene glycol 2000, 10% glycerol (v/v) and flash vitrified in liquid nitrogen before transport in a liquid-nitrogen cryogenic dewar to the ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble (France). Diffraction data were collected to 1.6 Å resolution from a crystal cryocooled at −173°C on an ADSC Quantum Q315r CCD detector at beam-line ID23-1 on 28 August 2011. The chosen wavelength corresponded to the selenium absorption edge, which was determined by a previous X-ray absorption near-edge fluorescence scan. The data were indexed, integrated, and merged with programs Xds [73] and Xscale [79], as well as Combat/Scala [80] from the Ccp4 suite of programs [81]. Data were transformed with Xdsconv or Truncate [82] to Mtz- and Shelx-format for structure solution and refinement. Table 2 provides a summary of the data processing statistics.

3.9. Structure solution and refinement

Initial automatic indexing suggested that the space group was R32, which led to very good processing statistics and an overall Rmeas of 7.7%. However, with this setting, only 65% of the collected spots were used for indexing and the structure could not be solved by SAD despite the presence of significant anomalous differences in the data. Thus, the data were reprocessed with space group P3121, which employed all the spots collected for indexing and yielded an overall Rmeas of 10.6%. With these data, the structure was solved by SAD with the program pipeline Xprep-Shelxd-Shelxe [83,84], which found all nine selenium sites in the a.u., enabled distinction between the space group and its enantiomorph and yielded a set of phases for automatic tracing with Arp/wArp [85]. The resulting model, consisting of three protomers per a.u., was completed through manual remodelling with the Coot program [86], but the final map was partially blurry and contained several regions with spurious density. Not surprisingly, crystallographic refinement of the model with the Refine protocol of the Phenix suite [87] stalled at Rfactor/free Rfactor values of ~35%/40%.

Thus, the data were reprocessed with space group P31. Analysis with Xtriage within Phenix revealed a strong off-origin peak of 72% height relative to the origin peak at fractional cell coordinates 0.331, 0.663 and 0.678, which was indicative of strong tNCS (figure 3b). Moreover, the data were hemihedrally twinned according to twin law (h, –h–k and –l). The values of the twin fraction α estimated by Xtriage ranged from 0.423 (ML α) to 0.430 (Britton) to 0.478 (H α). To determine the correct value, data from Xds processing were prepared for Ccp4 with Combat and Sortmtz, scaled with Scala and systematically detwinned with Detwin (https://www.ccp4.ac.uk/html/detwin.html) testing α values ranging from 0.30 to 0.48. The resulting data were transformed to Cns-format with Mtz2various within Ccp4 and analysed with the Padilla & Yeates twinning procedure (https://srv.mbi.ucla.edu/Twinning) [88], which determines local intensity differences by the formula L=(I1–I2)/(I1+I2), with I1 and I2 being the reflection intensities to be compared. This approach is insensitive to anisotropic diffraction and pseudo-centring [88]. The values of <|L|> and <L2> for the different twin fractions were compared with the theoretical values of a non-twinned dataset, which are 0.500 and 0.333, respectively. The best match was obtained with α = 0.423 (<|L|> = 0.493 and <L2> = 0.340).

Subsequent attempts to directly solve the structure within space group P31 and untreated data by SAD, as aforementioned for P3121, failed. By contrast, molecular replacement calculations with Phaser using a monomer of the model built into the P3121 Fourier map, with the program option Tncs inactivated, unambiguously found six molecules in the a.u. However, automatic crystallographic refinement of this model with Refine within Phenix or Shelxl, with the twinning option on, determined α to be ~0.5 in both cases, and yielded poor Fourier maps and R values. In contrast, refinement with programs Phenix and Buster/Tnt [89] with standard parameters for non-twinned data against the dataset detwinned as aforementioned with α = 0.423 yielded acceptable Fourier maps and enabled completion and refinement of the model of LKK to final Rfactor/free Rfactor values of 27.5%/30.2%. This model encompassed residues L706–K791 plus two N-terminal tag residues (S−1+G−2) in six copies per a.u. (molecules A–F) plus six chloride and two potassium ions, six diethylene glycol molecules and 476 solvent molecules (see table 2). While these R values are generally high for the resolution of the data, they are deemed acceptable given the intrinsic difficulty of handling data with (i) strong tNCS (molecules D–F result from pure translations of A–C); (ii) strong hemihedral twinning; and (iii) six protein monomers in the a.u. Moreover, all other validation parameters of the final model are within usually acceptable limits (table 2).

3.10. Miscellaneous

Figures were prepared with the Chimera program [90]. Secondary structure predictions were calculated with Jpred4 [91], and structure-similarity searches were performed with Dali [75]. Structure-based sequence alignments were first calculated with Promals3d (https://prodata.swmed.edu/promals3d) [92] and subsequently manually adjusted based on structure superposition, which was performed with the Ssm routine [93] within Coot and secondary structure predictions. Superposition of structures was also performed with Chimera and PDBeFold [94].

Comparative models for the CTDs of PPAD (K476–K556; UP A0A1R4AEC9) and CPG70 (Q746–G821; UP A0A1R4AHF7) were calculated with AlphaFold [95] using paired multiple sequence alignments, which enable the extraction of coevolutionary information and enhance the prediction accuracy [96]. The local confidence of the models was assessed by means of the predicted local-distance difference test (pLDDT) [97], which reliably estimates the accuracy of the Cα local-distance difference test [95]. In this respect, pLDDT values >90% account for high accuracy of the overall prediction and values >70% indicate generally correct predictions of the backbone [98]. The predicted CTD models of CPG70 and PPAD evince average pLDDT values of 93% and 92%, respectively, which indicates they are highly accurate.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the joint IBMB/IRB Automated Crystallography Platform and the Protein Purification Service at IBMB for assistance during crystallization and purification. The authors would also like to thank the ESRF synchrotron in Grenoble (France) for beamtime allocation and the beamline staff for assistance during diffraction data collection.

Contributor Information

Danuta Mizgalska, Email: dankamizgalska@gmail.com.

Arturo Rodríguez-Banqueri, Email: arbcri@ibmb.csic.es.

Florian Veillard, Email: florian.veillard@gmail.com.

Mirosław Książęk, Email: ksiazek.miroslaw@gmail.com.

Theodoros Goulas, Email: theodorosgoulas@uth.gr.

Tibisay Guevara, Email: tgpcri@ibmb.csic.es.

Ulrich Eckhard, Email: ueccri@ibmb.csic.es.

Jan Potempa, Email: jan.potempa@icloud.com.

F. Xavier Gomis-Rüth, Email: xgrcri@ibmb.csic.es.

Ethics

This work did not require ethical approval from a human subject or animal welfare committee.

Data accessibility

All data and reagents developed for the work presented in this paper can be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request. The new experimental crystal structure of the paper has been submitted to the Protein Data Bank and is universally accessible under code 8QB1.

Supplementary material is available online [99].

Declaration of AI use

We have not used AI-assisted technologies in creating this article.

Authors’ contributions

D.M.: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; A.R.-B.: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; F.V.: investigation, writing—review and editing; M.K.: investigation, writing—review and editing; T.G.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision; T.G.: investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; U.E.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, supervision, writing—review and editing; J.P.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; F.X.G.-R.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing—original draft.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported in part by funding from public bodies, which included grant nos. PID2019-107725RB-I00, RYC2020-029773-I, PID2021-128682OA-I00, PDC2022-133344-I00 and PID2022-137827OB-I00 from the State Agency of Research (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). Acknowledgements include ‘European Union Next Generation EU/PRTR’ and/or ‘cofunded by the EU’ and/or ‘ERDF – A way of making Europe’. Further funding was obtained by grant no. 2021SGR00423 from the National Government of Catalonia and by grant UMO-2019/35/B/NZ1/03118 from the National Science Centre of Poland.

References

- 1. Economou A, Christie PJ, Fernandez RC, Palmer T, Plano GV, Pugsley AP. 2006. Secretion by numbers: protein traffic in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 62, 308–319. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05377.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Christie PJ. 2019. The rich tapestry of bacterial protein translocation systems. Protein J. 38, 389–408. ( 10.1007/s10930-019-09862-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trivedi A, Gosai J, Nakane D, Shrivastava A. 2022. Design principles of the rotary type 9 secretion system. Front. Microbiol. 13, 845563. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2022.845563) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paillat M, Lunar Silva I, Cascales E, Doan T. 2023. A journey with type IX secretion system effectors: selection, transport, processing and activities. Microbiology (Reading) 169, 001320. ( 10.1099/mic.0.001320) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lasica AM, et al. 2016. Structural and functional probing of PorZ, an essential bacterial surface component of the type-IX secretion system of human oral-microbiomic Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 6, 37708. ( 10.1038/srep37708) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McBride MJ, Zhu Y. 2013. Gliding motility and Por secretion system genes are widespread among members of the phylum bacteroidetes. J. Bacteriol. 195, 270–278. ( 10.1128/JB.01962-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sato K, Naito M, Yukitake H, Hirakawa H, Shoji M, McBride MJ, Rhodes RG, Nakayama K. 2010. A protein secretion system linked to bacteroidete gliding motility and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 276–281. ( 10.1073/pnas.0912010107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goulas T, et al. 2015. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial host-protein citrullinating virulence factor, Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase. Sci. Rep. 5, 11969. ( 10.1038/srep11969) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lasica AM, Ksiazek M, Madej M, Potempa J. 2017. The Type IX Secretion System (T9SS): highlights and recent insights into its structure and function. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7, 215. ( 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00215) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gupta RS, Lorenzini E. 2007. Phylogeny and molecular signatures (conserved proteins and indels) that are specific for the bacteroidetes and chlorobi species. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 71. ( 10.1186/1471-2148-7-71) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kulkarni SS, Zhu Y, Brendel CJ, McBride MJ. 2017. Diverse C-terminal sequences involved in Flavobacterium johnsoniae protein secretion. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00884–00816. ( 10.1128/JB.00884-16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rinke C, et al. 2013. Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature 499, 431–437. ( 10.1038/nature12352) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bochtler M, Mizgalska D, Veillard F, Nowak ML, Houston J, Veith P, Reynolds EC, Potempa J. 2018. The Bacteroidetes Q-rule: pyroglutamate in signal peptidase I substrates. Front. Microbiol. 9, 230. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00230) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raut MP, Couto N, Karunakaran E, Biggs CA, Wright PC. 2019. Deciphering the unique cellulose degradation mechanism of the ruminal bacterium Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. Sci. Rep. 9, 16542. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-52675-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Williams TJ, Allen MA, Berengut JF, Cavicchioli R. 2021. Shedding light on microbial ‘dark matter’: insights into novel Cloacimonadota and Omnitrophota from an Antarctic lake. Front. Microbiol. 12, 741077. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2021.741077) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nguyen KA, Travis J, Potempa J. 2007. Does the importance of the C-terminal residues in the maturation of RgpB from Porphyromonas gingivalis reveal a novel mechanism for protein export in a subgroup of Gram-negative bacteria? J. Bacteriol. 189, 833–843. ( 10.1128/JB.01530-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Veith PD, Nor Muhammad NA, Dashper SG, Likić VA, Gorasia DG, Chen D, Byrne SJ, Catmull DV, Reynolds EC. 2013. Protein substrates of a novel secretion system are numerous in the Bacteroidetes phylum and have in common a cleavable C-terminal secretion signal, extensive post-translational modification, and cell-surface attachment. J. Proteome Res. 12, 4449–4461. ( 10.1021/pr400487b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Narita Y, Sato K, Yukitake H, Shoji M, Nakane D, Nagano K, Yoshimura F, Naito M, Nakayama K. 2014. Lack of a surface layer in Tannerella forsythia mutants deficient in the type IX secretion system. Microbiology 160, 2295–2303. ( 10.1099/mic.0.080192-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomek MB, Neumann L, Nimeth I, Koerdt A, Andesner P, Messner P, Mach L, Potempa JS, Schäffer C. 2014. The S-layer proteins of Tannerella forsythia are secreted via a type IX secretion system that is decoupled from protein O-glycosylation. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 29, 307–320. ( 10.1111/omi.12062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu Y, McBride MJ. 2014. Deletion of the Cytophaga hutchinsonii type IX secretion system gene sprP results in defects in gliding motility and cellulose utilization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 763–775. ( 10.1007/s00253-013-5355-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kita D, Shibata S, Kikuchi Y, Kokubu E, Nakayama K, Saito A, Ishihara K. 2016. Involvement of the type IX secretion system in Capnocytophaga ochracea gliding motility and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 1756–1766. ( 10.1128/AEM.03452-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li N, et al. 2017. The type IX secretion system is required for virulence of the fish pathogen Flavobacterium columnare. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e01769–e01717. ( 10.1128/AEM.01769-17) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen S, Blom J, Loch TP, Faisal M, Walker ED. 2017. The emerging fish pathogen Flavobacterium spartansii isolated from chinook salmon: comparative genome analysis and molecular manipulation. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2339. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02339) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kondo Y, Sato K, Nagano K, Nishiguchi M, Hoshino T, Fujiwara T, Nakayama K. 2018. Involvement of PorK, a component of the type IX secretion system, in Prevotella melaninogenica pathogenicity. Microbiol. Immunol. 62, 554–566. ( 10.1111/1348-0421.12638) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taillefer M, Arntzen MØ, Henrissat B, Pope PB, Larsbrink J. 2018. Proteomic dissection of the cellulolytic machineries used by soil-dwelling Bacteroidetes. mSystems 3, 00240–00218. ( 10.1128/mSystems.00240-18) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Naas AE, et al. 2018. ‘Candidatus Paraporphyromonas polyenzymogenes’ encodes multi-modular cellulases linked to the type IX secretion system. Microbiome 6, 44. ( 10.1186/s40168-018-0421-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sato K, et al. 2018. Immunoglobulin-like domains of the cargo proteins are essential for protein stability during secretion by the type IX secretion system. Mol. Microbiol. 110, 64–81. ( 10.1111/mmi.14083) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McBride MJ. 2019. Bacteroidetes gliding motility and the type IX secretion system. Microbiol. Spectr. 7, PSIB-0002-2018. ( 10.1128/microbiolspec.PSIB-0002-2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ramos KRM, Valdehuesa KNG, Bañares AB, Nisola GM, Lee WK, Chung WJ. 2020. Overexpression and characterization of a novel GH16 β-agarase (Aga1) from cellulophaga omnivescoria W5C. Biotechnol. Lett. 42, 2231–2238. ( 10.1007/s10529-020-02933-x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barbier P, Rochat T, Mohammed HH, Wiens GD, Bernardet JF, Halpern D, Duchaud E, McBride MJ. 2020. The type IX secretion system is required for virulence of the fish pathogen Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86, e00799–e00720. ( 10.1128/AEM.00799-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen Z, Niu P, Ren X, Han W, Shen R, Zhu M, Yu Y, Ding C, Yu S. 2022. Riemerella anatipestifer T9SS effector SspA functions in bacterial virulence and defending natural host immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e0240921. ( 10.1128/aem.02409-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naito M, Shoji M, Sato K, Nakayama K. 2022. Insertional inactivation and gene complementation of Prevotella intermedia type IX secretion system reveals its indispensable roles in black pigmentation, hemagglutination, protease activity of interpain A, and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 204, e0020322. ( 10.1128/jb.00203-22) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Astafyeva Y, Gurschke M, Streit WR, Krohn I. 2022. Interplay between the microalgae Micrasterias radians and its symbiont Dyadobacter sp. HH091. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1006609. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1006609) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Escribano MP, Balado M, Toranzo AE, Lemos ML, Magariños B. 2023. The secretome of the fish pathogen Tenacibaculum maritimum includes soluble virulence-related proteins and outer membrane vesicles. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1197290. ( 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1197290) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kondo Y, Ohara K, Fujii R, Nakai Y, Sato C, Naito M, Tsukuba T, Kadowaki T, Sato K. 2023. Transposon mutagenesis and genome sequencing identify two novel, tandem genes involved in the colony spreading of Flavobacterium collinsii, isolated from an ayu fish, Plecoglossus altivelis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13, 1095919. ( 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1095919) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent Jr RL. 1998. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25, 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hajishengallis G, et al. 2011. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe 10, 497–506. ( 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. 2014. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1045–1053. ( 10.1177/0022034514552491) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tonetti MS, Jepsen S, Jin L, Otomo-Corgel J. 2017. Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: a call for global action. J. Clin. Periodontol. 44, 456–462. ( 10.1111/jcpe.12732) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Butt K, Butt R, Sharma P. 2019. The burden of periodontal disease. Dent. Update 46, 907–913. ( 10.12968/denu.2019.46.10.907) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mizgalska D, et al. 2021. Intermolecular latency regulates the essential C-terminal signal peptidase and sortase of the Porphyromonas gingivalis type-IX secretion system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2103573118. ( 10.1073/pnas.2103573118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hočevar K, Potempa J, Turk B. 2018. Host cell-surface proteins as substrates of gingipains, the main proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biol. Chem. 399, 1353–1361. ( 10.1515/hsz-2018-0215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bereta G, Goulas T, Madej M, Bielecka E, Solà M, Potempa J, Gomis-Rüth FX. 2019. Structure, function, and inhibition of a genomic/clinical variant of Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase. Protein Sci. 28, 478–486. ( 10.1002/pro.3571) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen YY, Cross KJ, Paolini RA, Fielding JE, Slakeski N, Reynolds EC. 2002. CPG70 is a novel basic metallocarboxypeptidase with C-terminal polycystic kidney disease domains from Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 23433–23440. ( 10.1074/jbc.M200811200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sato K, et al. 2005. Identification of a new membrane-associated protein that influences transport/maturation of gingipains and adhesins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8668–8677. ( 10.1074/jbc.M413544200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seers CA, Slakeski N, Veith PD, Nikolof T, Chen YY, Dashper SG, Reynolds EC. 2006. The RgpB C-terminal domain has a role in attachment of RgpB to the outer membrane and belongs to a novel C-terminal-domain family found in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6376–6386. ( 10.1128/JB.00731-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kharade SS, McBride MJ. 2014. Flavobacterium johnsoniae chitinase ChiA is required for chitin utilization and is secreted by the type IX secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 196, 961–970. ( 10.1128/JB.01170-13) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kharade SS, McBride MJ. 2015. Flavobacterium johnsoniae PorV is required for secretion of a subset of proteins targeted to the type IX secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 197, 147–158. ( 10.1128/JB.02085-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. de Diego I, et al. 2016. The outer-membrane export signal of Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion system (T9SS) is a conserved C-terminal β-sandwich domain. Sci. Rep. 6, 23123. ( 10.1038/srep23123) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Veith PD, Glew MD, Gorasia DG, Reynolds EC. 2017. Type IX secretion: the generation of bacterial cell surface coatings involved in virulence, gliding motility and the degradation of complex biopolymers. Mol. Microbiol. 106, 35–53. ( 10.1111/mmi.13752) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Green ER, Mecsas J. 2016. Bacterial secretion systems: an overview. In Virulence mechanisms of bacterial pathogens (eds Kudva ITCornick NA, Plummer PJ, Zhang Q, Nicholson TL, Bannantine JP, Bellaire BH), pp. 213–219, 5th edn. Washington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shoji M, Sato K, Yukitake H, Kondo Y, Narita Y, Kadowaki T, Naito M, Nakayama K. 2011. Por secretion system-dependent secretion and glycosylation of Porphyromonas gingivalis hemin-binding protein 35. PLoS ONE 6, e21372. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0021372) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Glew MD, et al. 2012. PG0026 is the C-terminal signal peptidase of a novel secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24605–24617. ( 10.1074/jbc.M112.369223) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Glew MD, Veith PD, Chen D, Gorasia DG, Peng B, Reynolds EC. 2017. PorV is an outer membrane shuttle protein for the type IX secretion system. Sci. Rep. 7, 8790. ( 10.1038/s41598-017-09412-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gorasia DG, Veith PD, Chen D, Seers CA, Mitchell HA, Chen YY, Glew MD, Dashper SG, Reynolds EC. 2015. Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion substrates are cleaved and modified by a sortase-like mechanism. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1005152. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005152) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Veillard F, et al. 2019. Proteolytic processing and activation of gingipain zymogens secreted by T9SS of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Biochimie 166, 161–172. ( 10.1016/j.biochi.2019.06.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Curtis MA, Thickett A, Slaney JM, Rangarajan M, Aduse-Opoku J, Shepherd P, Paramonov N, Hounsell EF. 1999. Variable carbohydrate modifications to the catalytic chains of the RgpA and RgpB proteases of Porphyromonas gingivalis W50. Infect. Immun. 67, 3816–3823. ( 10.1128/IAI.67.8.3816-3823.1999) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shoji M, Sato K, Yukitake H, Kamaguchi A, Sasaki Y, Naito M, Nakayama K. 2018. Identification of genes encoding glycosyltransferases involved in lipopolysaccharide synthesis in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 33, 68–80. ( 10.1111/omi.12200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Veith PD, Shoji M, O’Hair RAJ, Leeming MG, Nie S, Glew MD, Reid GE, Nakayama K, Reynolds EC. 2020. Type IX secretion system cargo proteins are glycosylated at the C terminus with a novel linking sugar of the Wbp/Vim pathway. mBio 11, e01497–e01420. ( 10.1128/mBio.01497-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Madej M, et al. 2021. PorZ, an essential component of the type IX secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis, delivers anionic lipopolysaccharide to the PorU sortase for transpeptidase processing of T9SS cargo proteins. mBio 12, e02262–e02220. ( 10.1128/mBio.02262-20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yukitake H, Shoji M, Sato K, Handa Y, Naito M, Imada K, Nakayama K. 2020. PorA, a conserved C-terminal domain-containing protein, impacts the PorXY-SigP signaling of the type IX secretion system. Sci. Rep. 10, 21109. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-77987-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kulkarni SS, Johnston JJ, Zhu Y, Hying ZT, McBride MJ. 2019. The carboxy-terminal region of Flavobacterium johnsoniae SprB facilitates its secretion by the type IX secretion system and propulsion by the gliding motility machinery. J. Bacteriol. 201, e00218–e00219, ( 10.1128/JB.00218-19) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xie S, Tan Y, Song W, Zhang W, Qi Q, Lu X. 2022. N-Glycosylation of a cargo protein C-terminal domain recognized by the type IX secretion system in Cytophaga hutchinsonii affects protein secretion and localization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 88, e0160621, ( 10.1128/AEM.01606-21) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dorgan B, Liu Y, Wang S, Aduse-Opoku J, Whittaker SB, Roberts MAJ, Lorenz CD, Curtis MA, Garnett JA. 2022. Structural model of a Porphyromonas gingivalis type IX secretion system shuttle complex. J. Mol. Biol 434, 167871. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2022.167871) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Książek M, et al. 2023. A unique network of attack, defence and competence on the outer membrane of the periodontitis pathogen Tannerella forsythia. Chem. Sci. 14, 869–888. ( 10.1039/d2sc04166a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bork P, Holm L, Sander C. 1994. The immunoglobulin fold. Structural classification, sequence patterns and common core. J. Mol. Biol. 242, 309–320. ( 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1582) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Halaby DM, Poupon A, Mornon J. 1999. The immunoglobulin fold family: sequence analysis and 3D structure comparisons. Protein Eng. 12, 563–571. ( 10.1093/protein/12.7.563) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Berisio R, Ciccarelli L, Squeglia F, De Simone A, Vitagliano L. 2012. Structural and dynamic properties of incomplete immunoglobulin-like fold domains. Protein Pept. Lett. 19, 1045–1053. ( 10.2174/092986612802762732) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Slakeski N, Seers CA, Ng K, Moore C, Cleal SM, Veith PD, Lo AW, Reynolds EC. 2011. C-terminal domain residues important for secretion and attachment of RgpB in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 193, 132–142. ( 10.1128/JB.00773-10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhou XY, Gao JL, Hunter N, Potempa J, Nguyen KA. 2013. Sequence-independent processing site of the C-terminal domain (CTD) influences maturation of the RgpB protease from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Microbiol. 89, 903–917. ( 10.1111/mmi.12319) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Veillard F, Potempa B, Guo Y, Ksiazek M, Sztukowska MN, Houston JA, Koneru L, Nguyen KA, Potempa J. 2015. Purification and characterisation of recombinant His-tagged RgpB gingipain from Porphymonas gingivalis. Biol. Chem. 396, 377–384. ( 10.1515/hsz-2014-0304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Einspahr HM, Weiss MS. 2012. Quality indicators in macromolecular crystallography: definitions and applications. In International tables for crystallography. Volume F: crystallography of biological macromolecules (eds Arnold E, Himmel DM, Rossmann MG), pp. 64–74, 2nd edn. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kabsch W. 2010. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 125–132. ( 10.1107/S0907444909047337) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ksiazek M, Mizgalska D, Eick S, Thøgersen IB, Enghild JJ, Potempa J. 2015. KLIKK proteases of Tannerella forsythia: putative virulence factors with a unique domain structure. Front. Microbiol. 6, 312. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00312) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Holm L, Laiho A, Törönen P, Salgado M. 2023. DALI shines a light on remote homologs: one hundred discoveries. Protein Sci. 32, e4519. ( 10.1002/pro.4519) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bao K, Belibasakis GN, Thurnheer T, Aduse-Opoku J, Curtis MA, Bostanci N. 2014. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipains in multi-species biofilm formation. BMC Microbiol. 14, 258. ( 10.1186/s12866-014-0258-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Shoji M, Sato K, Yukitake H, Naito M, Nakayama K. 2014. Involvement of the Wbp pathway in the biosynthesis of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide with anionic polysaccharide. Sci. Rep. 4, 5056. ( 10.1038/srep05056) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Boyde TR, Rahmatullah M. 1980. Optimization of conditions for the colorimetric determination of citrulline, using diacetyl monoxime. Anal. Biochem. 107, 424–431. ( 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90404-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kabsch W. 2010. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 133–144. ( 10.1107/S0907444909047374) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D 62, 72–82. ( 10.1107/S0907444905036693) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Agirre J, et al. 2023. The CCP4 suite: integrative software for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 79, 449–461. ( 10.1107/S2059798323003595) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. French S, Wilson K. 1978. On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr. A 34, 517–525. ( 10.1107/S0567739478001114) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sheldrick GM. 2010. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 479–485. ( 10.1107/S0907444909038360) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sheldrick GM. 2011. The SHELX approach to experimental phasing of macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. A 67, C13. ( 10.1107/S0108767311099727) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Langer GG, Hazledine S, Wiegels T, Carolan C, Lamzin VS. 2013. Visual automated macromolecular model building. Acta Crystallogr. D 69, 635–641. ( 10.1107/S0907444913000565) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Casañal A, Lohkamp B, Emsley P. 2020. Current developments in coot for macromolecular model building of electron cryo-microscopy and crystallographic data. Protein Sci. 29, 1069–1078. ( 10.1002/pro.3791) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]