Abstract

Mindfulness witnessed a substantial popularity surge in the past decade, especially as digitally self-administered interventions became available at relatively low costs. Yet, it is uncertain whether they effectively help reduce stress. In a preregistered (OSF 10.17605/OSF.IO/UF4JZ; retrospective registration at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT06308744) multi-site study (nsites = 37, nparticipants = 2,239, 70.4% women, Mage = 22.4, s.d.age = 10.1, all fluent English speakers), we experimentally tested whether four single, standalone mindfulness exercises effectively reduced stress, using Bayesian mixed-effects models. All exercises proved to be more efficacious than the active control. We observed a mean difference of 0.27 (d = −0.56; 95% confidence interval, −0.43 to −0.69) between the control condition (M = 1.95, s.d. = 0.50) and the condition with the largest stress reduction (body scan: M = 1.68, s.d. = 0.46). Our findings suggest that mindfulness may be beneficial for reducing self-reported short-term stress for English speakers from higher-income countries.

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Psychology

Does self-administered mindfulness effectively reduce stress? In a study across 37 sites involving 2,239 participants, four mindfulness exercises significantly reduced short-term, self-reported stress.

Main

Mindfulness meditation is defined as ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally’1. It thus emphasizes attention to the present moment, with awareness of one’s bodily sensations or one’s mental content such as thoughts, emotions and memories. Engaging in mindfulness meditation appears simple: one is asked to focus one’s attention on the breath and on the present moment, without needing complex postures, settings or apparatus. Partly because of this apparent simplicity, mindfulness meditation protocols that can be self-administered (often referred to as self-help mindfulness interventions) have increased in accessibility and popularity in recent years2. Their appeal relies on costs lower than for those administered by professionals, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programmes3, and on easier accessibility4–6 owing to diverse formats (for example, self-help books, computer programmes, smartphone apps and audio and video recordings).

Notwithstanding their popularity, access to such mindfulness tools remains restricted to those who can afford both the costs and the time necessary to practice. Yet, despite having millions of users, evidence for the effectiveness of these mindfulness interventions is debated and at least two key empirical questions remain unanswered. First, are these types of interventions truly effective in reducing stress levels? And second, which self-administered mindfulness exercises, from the plethora of those available, might work best? We attempted to answer these questions first by conducting a survey among mindfulness practitioners to identify the mindfulness exercises that are most likely to reduce stress. On the basis of the results of the survey, we then designed a multi-site, highly powered study to test the effects and the boundary conditions of four self-administered mindfulness meditation exercises on stress reduction.

Compared to established mindfulness protocols (for example, MBSR3), self-administered mindfulness exercises present fewer constraints. They do not require the physical presence of an instructor because they include prerecorded protocols and they allow practitioners to meditate at the time and place of their choosing6. And while some established protocols need individuals to sustain practice for at least 8 weeks, many self-administered mindfulness interventions hold promises for reducing stress levels despite being short and allowing one to practice if and when one decides. It is thus important to understand whether they indeed bring about the expected results. While some studies2,7 and a recent meta-analysis8 have shown reductions in self-reported stress following self-administered mindfulness, others9 did not find evidence that such training effectively decreased perceived stress and a meta-analysis failed to find robust effects in this direction after accounting for publication bias10.

A different, albeit important issue is that many such exercises have been empirically examined as part of longer sequences that include more than one exercise, making it difficult to conclude what specific effect each exercise can have on reducing stress. Some studies have tested single brief mindfulness exercises11,12, however, to our knowledge, none investigated the effectivess of brief standalone mindfulness exercises on stress reduction. Others13 divided the plethora of mindfulness exercises into three categories reflective of their focus, namely ‘awareness’, ‘present experience’ and ‘acceptance’. Awareness mindfulness exercises typically involve a sequence of steps going from disengaging from an automatic train of thought (for example, interrupting repetitive thoughts by taking a long breath) to focusing the attention on an object that is used as an ‘anchor’ (for example, the breath and body parts), returning the attention to the object of focus when one realizes they had been distracted and watching where the mind wanders next. Present experience mindfulness exercises instruct participants to pay attention completely to the activity being carried out (for example, bringing the attention to the sole of the foot while walking). If the mind wanders, the instructions given aim to help the practitioner redirect their attention to the present moment. Acceptance mindfulness exercises are characterized by applying a non-judgmental attitude of kindness and curiosity to one’s experience. Practitioners are invited to cultivate positive feelings towards themselves and others (for example, directing loving kindness to themselves or to someone else). While these different categories may share some common features, for the purposes of the present investigation we maintained this system of classification because it allowed us to better understand the potential applied value of such self-administered mindfulness exercises.

Finally, the potential moderating influence of different personality traits on the effects of these exercises remains largely unexplored. Previous research has indicated that neuroticism may moderate the psychological effects of mindfulness training14,15. A meta-analysis appraising the evidence of 29 studies found that neuroticism exhibits the most pronounced association with self-reported individual differences in mindfulness among the Big Five personality traits (r = −0.45; ref. 16). Furthermore, one study found that individuals who scored higher in neuroticism showed a more significant decrease in psychological distress and improvement of overall wellbeing when compared to a control group after participating in an MBSR. While this study suggested that neuroticism moderated the effect, the power of the design (with n = 244) to detect smaller but still theoretically meaningful interaction was modest17 and the authors acknowledged that the use of four possible moderators for each outcome may have inflated type 1 errors14.

Therefore, the primary objective of this multi-site project was to test the comparative effectiveness of self-administered mindfulness exercises in reducing individuals’ stress levels when compared to a non-mindful active control condition. We proposed that participants allocated to any experimental (mindfulness) condition would experience lower self-reported stress levels compared to participants allocated to an active control condition. The secondary objective was to explore whether these effects are moderated by participants’ levels of neuroticism and by their English language proficiency. To justify the latter factor’s potential moderating role, we looked at how language plays a role in the acquisition of knowledge to make meaning of emotional experiences and perceptions18. If certain levels of knowledge of a particular language are not reached, the processes of making meaning out of emotional experiences could be compromised.

Results

Confirmatory analyses of mindfulness versus control effect

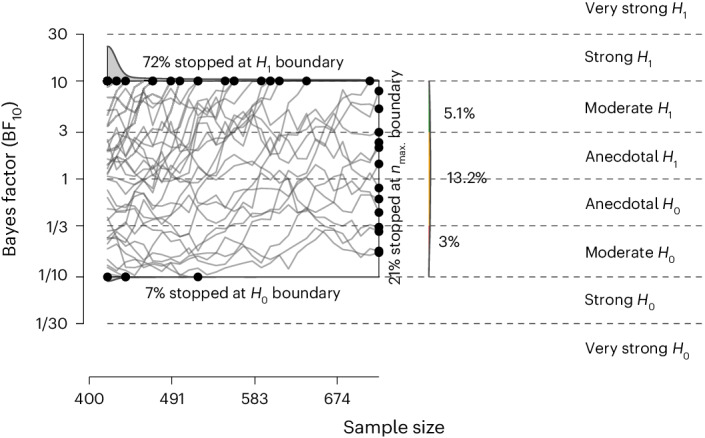

We recoded the reverse items and then averaged the scores for the 20 state-focused items of the state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) Form Y-1 (ref. 19), the self-reported measure of stress. The experimental condition with the highest Bayes factor was the body scan, with a Bayes factor of 3.69 × 1011, indicating that the observed data are 3.69 × 1011 times more likely to occur under H1 (that is, participants report lower self-reported levels of stress in the mindfulness conditions compared to the control condition) than under H0 (that is, there is no difference between conditions in self-reported stress levels), thus denoting ‘extreme evidence’20. This confirms the hypothesis that the body scan meditation exercise reduced self-reported stress compared to the active control condition (Table 1). All other mindfulness conditions also surpassed the threshold of compelling evidence of 10 in favour of H1 compared to the active control (Table 1). The Bayesian mixed-effects models provided strong evidence that all four mindfulness conditions were effective in reducing participants’ self-reported stress levels compared to the active control condition (Fig. 1 gives a simulation of the Bayes factor design).

Table 1.

Means and s.d. of self-reported stress levels of the four Bayesian mixed-effects models with the active control for the STAI Form Y-1

| Condition | n | M | s.d. | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active control condition | 478 | 1.95 | 0.50 | – |

| Body scan | 449 | 1.68 | 0.46 | 3.7 × 1011 |

| Mindful breathing | 469 | 1.73 | 0.50 | 2.3 × 105 |

| Loving kindness | 427 | 1.70 | 0.49 | 1.1 × 107 |

| Mindful walking | 416 | 1.73 | 0.46 | 4.8 × 102 |

A positive Bayes factor (BF10) denotes increasing evidence of H1 compared to H0.

Fig. 1. Simulation of the Bayesian two-sided sequential design.

After 10,000 iterations, the simulation indicates that under the proposed design, there is a 79% chance (72% under H1 and 7% erroneously under H0) that the test will reach compelling evidence boundaries (BF10 = 10 or 1/10). There is a 21% chance that the test will conclude by reaching the maximum (max.) sample size of 720 per condition, with a 5% probability of providing some evidence in favour of H1 (BF10 > 3).

Exploratory analyses

Cohen’s d for each condition compared to the active control condition

We calculated Cohen’s d for each condition test using the escalc function of the metafor package using sample means (M) and sample s.d. Even if we relied on a Bayesian framework, we used Cohen’s d as an estimate of the magnitude of the effect because Cohen’s d can be interpreted as the standard mean difference between two independent samples. Table 2 summarizes the effect sizes for all the conditions when compared to the control condition.

Table 2.

Effect sizes for each mindfulness condition tested against the active control, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and standard errors of the estimate (s.e.)

| Condition test (against control) | Cohens’ d [95% CI] | s.e. |

|---|---|---|

| Body scan | −0.56 [−0.43, −0.69] | 0.07 |

| Mindful breathing | −0.46 [−0.30, −0.61] | 0.08 |

| Loving kindness | −0.48 [−0.35, −0.62] | 0.07 |

| Mindful walking | −0.45 [−0.32, −0.59] | 0.07 |

Heterogeneity per site

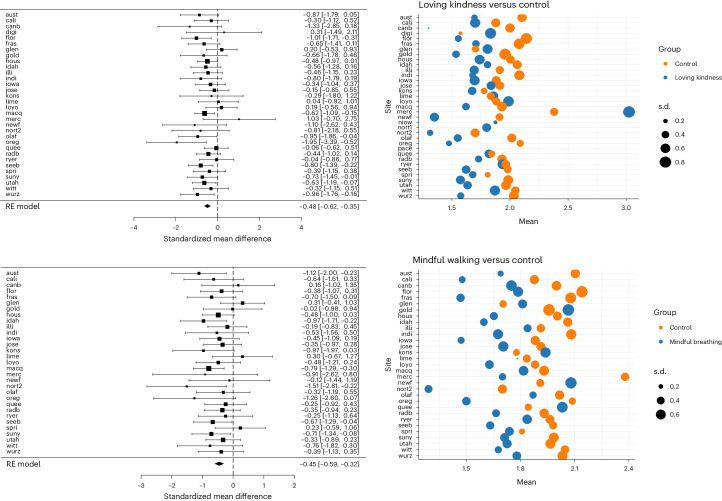

For each of the mindfulness exercises, we did not detect significant heterogeneity. Forest plot (right side) plotted means and s.d. for self-reported levels of stress for each mindfulness condition exercise compared to the active control condition (left side) are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Additionally, in Table 3 we reported the heterogeneity values for each mindfulness condition across sites.

Fig. 2. Forest plot and bubble plot for body scan and mindful breathing.

On the left are the Forest plots for the effects of body scan (upper one) and mindful breathing (lower one) versus control, using Cohen’s d as the effect size measure. Black boxes represent site-level effect size estimation of the random-effects (RE) model and the horizontal lines represent the associated CIs. The diamond represents overall effect size estimate and the 95% CI (n = 2,239). On the right are the bubble plots showing site-level means and s.d. The list of sites and abbreviations can be found here: https://osf.io/bdwu8.

Fig. 3. Forest plot and bubble plot for loving kindness and mindful walking.

On the left are the Forest plots for the effects of loving kindness (upper one) and mindful walking (lower one) versus control, using Cohen’s d as the effect size measure. Black boxes represent site-level effect size estimation of the RE model and the horizontal lines represent the associated CIs. The diamond represents overall effect size estimate and the 95% CI (n = 2,239). On the right are the bubble plots showing site-level means and s.d. The list of sites and abbreviations can be found here: https://osf.io/bdwu8.

Table 3.

Heterogeneity values for each mindfulness condition across sites

| Condition | Cochran’s Q-test (P value) | τ | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body scan | 0.83 | 0 | 0% |

| Mindful breathing | 0.17 | 0.21 | 24.24% |

| Loving kindness | 0.50 | 0 | 0% |

| Mindful walking | 0.67 | 0 | 0% |

τ, s.d. of the distribution of true effects; I2, proportion of total variation in study estimates due to heterogeneity.

Emotion dimensions

We explored the effects of the mindfulness exercises on the dimensions of pleasure, arousal and dominance as compared to the active control condition again using four Bayesian mixed-effects models. We found that only for the dimension of pleasure and only for the mindful breathing condition the Bayes factor favoured H1, surpassing the set threshold (BF10 = 16.1), indicating that participants who engaged in mindful breathing felt more pleasant than participants who listened to the story in the active control condition.

Moderation by neuroticism

We investigated whether neuroticism moderated the relationship between mindfulness exercises and stress. We merged the four mindfulness conditions and compared the merged conditions to the active control condition to achieve higher power. We failed to find any evidence for the moderation of neuroticism as the ratio between the two models (the full model and the one with only the interaction) yielded an inconclusive Bayes factor (BF10 = 0.11).

Moderation by English language proficiency

We investigated whether participants’ English language proficiency moderated the effect of the mindfulness exercises on stress. Of the total 2,239 participants included in the analyses, 647 were non-native English speakers at least C1/C2 level, while 1,592 were native English speakers. We again merged the mindfulness conditions into a single group to increase statistical power. We did not find evidence for an interaction effect between mindfulness conditions and participants’ English language proficiency (BF10 = 0.05).

Robustness analyses

We examined whether the difference in stress levels between the experimental (mindfulness) and the control condition could be due to one particular story excerpt (‘Silverview’ by John le Carré21) being perceived as more anxiogenic than the others (Table 4). We conducted three independent t-tests and found a slight discrepancy in self-reported stress levels between participants who listened to John le Carré’s ‘Silverview’ excerpt and those who listened to Tolkien’s ‘Smith of Wootton Major’ excerpt22, t(313.75) = 2.71, P = 0.007. To address the issue of several comparisons, we applied the Bonferroni correction, yielding an adjusted P = 0.021. Notably, even after applying the Bonferroni correction, a statistically significant difference persisted between the two excerpts. These results indicate that participants exposed to the ‘Silverview’ excerpt experienced higher levels of stress compared to those exposed to the ‘Smith of Wootton Major’ excerpt. To test whether this may have affected the overall results, we re-ran the main analyses excluding participants who listened to ‘Silverview’ (n = 157). This participant exclusion resulted in a significant decrease in power because the control group was reduced from 478 to 321 participants; nevertheless, the Bayes factor remained above the threshold for compelling evidence in three of the mindfulness conditions (body scan, mindful breathing and loving kindness) but not in the mindful walking condition (BF10 = 0.08; Table 5).

Table 4.

Means and s.d. of scores on the STAI Form Y-1 for each story of the control condition

| Story excerpt | Length (min) | Word count | M | s.d. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Silverview’ by John le Carré | 15.01 | 1,838 | 2.04 | 0.51 |

| ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ by Ernest Hemingway | 14.19 | 2,039 | 1.93 | 0.47 |

| ‘Smith of Wootton Major’ by J. R. R. Tolkien | 14.58 | 2,309 | 1.88 | 0.50 |

Table 5.

Results of the four independent comparisons with the active control for the STAI Form Y-1, after excluding participants who listened to the ‘Silverview’ excerpt

| Condition | n | M | s.d. | BF10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active control condition | 321 | 1.91 | 0.49 | – |

| Body scan | 449 | 1.68 | 0.46 | 2.3 × 105 |

| Mindful breathing | 469 | 1.73 | 0.50 | 16.65 |

| Loving kindness | 427 | 1.70 | 0.49 | 118.10 |

| Mindful walking | 416 | 1.73 | 0.46 | 0.08 |

Discussion

We investigated whether four different mindfulness exercises were independently effective in reducing participants’ stress levels as compared to the active control condition. We found that all four mindfulness exercises (body scan, mindful breathing, mindful walking and loving kindness) decreased participants’ self-reported stress compared to listening to one of the three story excerpts that was part of the active control condition.

The current research aimed to fill a knowledge gap regarding the efficacy of brief, self-administered mindfulness interventions for reducing stress. Recent meta-analyses either failed to find evidence in favour of such effects9,10 or detected them, albeit small in magnitude2,8, potentially because of the high risk of bias or small sample of the studies included and insufficient power23. Other such tests included solely a passive, rather than an active, control condition7, while still others did not adhere to open science practices by lacking preregistration24,25.

The present multi-site design attempted to provide solutions for these shortcomings. Indeed, compared with previous studies, the present multi-site design was adequately powered, compared each mindfulness condition with an active control group (and not a passive control group or a waiting list) and was preregistered. The results can thus serve as a reliable basis for building testing protocols of self-administered mindfulness effects because they suggest that the four mindfulness exercises included in the study are slightly effective in reducing stress levels.

This project is an important step toward obtaining high-powered tests of the efficacy of self-administered mindfulness exercises for reducing stress. On the one hand, the current multi-site study showcases how even short mindfulness exercises can be valuable tools in situations when short-term mood regulation is necessary, such as withstanding a stressful exam or calming oneself in a road-rage situation26. The possibility that short-term mindfulness practice adds to one’s repertoire of skills to reduce stress need not harm nor challenge the popular expectation that mindfulness meditation brings about positive results only via prolonged practice. Learning to practice mindfulness in a shorter time than traditional protocols typically require is a valuable asset for people for whom longer time commitment for mindfulness is a capacity- or motivation-based deterrent27.

Understanding the optimal timing to learn mindfulness skills or the conditions in which mindfulness induces effects which are longer-term compared to those observed in the present experiment are important questions, yet they extend beyond the scope of the present research. Notwithstanding the absence of high-powered, preregistered studies which would make for a more reliable body of knowledge on these topics, some existent data yet allow partial answers. In line with the extended model of emotion regulation28, mindfulness skills mastered before a stressful situation occurs can allow someone extra flexibility to regulate antecedents of emotional reactions, such as which aspects one pays attention to (attentional deployment) or the way one cognitively represents the stressful situation (cognitive change). For example, an 8-week randomized controlled trial of mindfulness completed in the year leading to the examination period significantly reduced students’ psychological distress during that same examination period29. Longer, for example, 8-week mindfulness protocols such as MBSR can enhance trait/dispositional mindfulness (the inherent capacity to be in the present moment15,30) and people’s mindfulness self-efficacy (one’s perceived ability to maintain non-judgemental awareness in different situations). Therefore, for individuals who already possess high levels of trait mindfulness, the timing of mindfulness exercises may be less crucial, as they already exhibit a disposition that helps reduce their susceptibility to stressors. Nevertheless, more preregistered, high-powered studies need to be conducted on the topic to conclusively determine the ideal timing for mindfulness exercises and their potential for long-term changes.

Despite the strengths of the current multi-site project, some limitations must be considered. The effects of each mindfulness exercise on stress were rather small and relied on self-reported stress. Such assessments may limit the validity of the present findings. Participants may lack introspective ability leading to biased estimates about their levels of stress31 and may be subjected to demand characteristics effects32,33. Future research using physiological assessments of the autonomic nervous system (for example, assessment of catecholamines, assessment of the autonomic nervous system via skin conductance, cortisol, heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure34,35) may help limit such problems. Thus, future studies investigating the efficacy of single brief self-administered mindfulness exercises should include both psychological and physiological measures to render more reliable estimates of stress levels and to rule out the possibility of a demand characteristics effect. Another potential limitation is the choice of control condition in our study. We found that participants who listened to the excerpt from ‘Silverview’21 by John le Carré exhibited higher levels of state anxiety compared to participants who listened to the two other story excerpts. We conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding the former and found that only three mindfulness conditions (body scan, loving kindness and mindful breathing) led to a significant reduction in self-reported stress when compared to the control condition, which now involved listening to only two different randomly sampled stories. However, we did not observe a similar significant effect for the mindful walking group. This outcome may be attributed to a reduced statistical power in the control group which in this analysis loses one-third of the participants (decreasing from 478 to 321). Finally, we believe that it is important to consider several limitations on the generalizability of the results of this study36: Our findings only apply directly to participants who are (1) older than 18, (2) fluent/native English speakers living in Australia, Europe, the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States, (3) non-meditators, (4) do not have a history of mental illness and (5) mostly students (94.2%). Further research is needed to test whether the findings of the present study will indeed generalize to other populations.

In conclusion, we have conducted a large-scale project investigating the efficacy of single brief mindfulness interventions in a multi-site study conducted over 37 sites and including 2,239 valid observations. The limitations of the study notwithstanding, we found that each of the four mindfulness exercises (body scan, mindful breathing, mindful walking and loving kindness) was slightly more efficacious in reducing self-reported stress as compared to the active control condition. These interventions should be intended as being effective in the short-term and are unlikely to affect dispositional traits (such as chronic stress). Although we found an effect for single brief mindfulness exercises, our multi-site study carries the limitations of using only self-report measures. Well-powered studies with a physiological assessment of the autonomic nervous system are thus necessary to corroborate the results of the current multi-site project.

Methods

Ethical regulations statement

This research project complied with all ethical regulations for research involving human participants laid out by the host organization, Swansea University. Approval was granted by the School of Psychology’s Research Ethics Committee. The participating sites either received ethical approval from their local institutional review boards (IRBs) or stated that they were exempt. Swansea University and Université Grenoble Alpes carried out the administrative organization for the study. Swansea University was also the data controller for this project. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before collecting any data. Participants’ personal data were processed for the purposes outlined in the information sheet. The project was conducted in line with the CO-RE Lab Lab Philosophy v.5 (ref. 37). The current multi-site project (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06308744) followed the route of a parallel randomized controlled trial. All materials used in the study, including the preregistered document (https://osf.io/us5ae), the ethics (IRB) approval documents of all the sites involved in the project and the meditation scripts are available on our Open Science Framework (OSF) page (https://osf.io/6w2zm/) and in our ClinicalTrials.gov registration. The data analytic script can be found on the GitHub repository of the project (https://github.com/alessandro992/A-large-multisite-test-of-self-administered-mindfulness) and on the OSF page (https://osf.io/6w2zm/).

Participants

Data were collected between 23 March and 30 June 2022. We limited participation in the study to English native speakers or participants who self-assessed their English language proficiency at the C1/C2 levels from the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages38 to ensure maximum comprehension of the English-spoken audio files used in all conditions. Participants were excluded if they reported having or having had a history of mental illnesses assessed via a prescreening question, if they declared having meditated in the previous 6 months or if they did not match the English language proficiency required (participants had to be either native language level or fluent in English). Each participant was asked to take part in the survey using a smartphone with headphones or earphones attached, to ensure that participants could perform any of the mindfulness activities they were randomly assigned to (that is, mindful walking). Each site committed to collect between 70 and 120 participants; however, if a site collected fewer or more participants than was the target, we still used the data from those participants in the analysis. Each site collected a different number of participants, from a minimum of one and a maximum of 179. Our Rpubs page shows the total number of participants per site (https://rpubs.com/ale-sparacio92/920457). Data collection was performed blind to the experimental conditions but data analysis was not performed blind. However, given that all our analyses were preregistered, it is unlikely that the lack of blinding in data analysis introduced bias.

The dataset originally comprised 6,691 responses, including both the ‘test answers’ generated by the site collaborators while developing and previewing the survey and the actual answers submitted by the participants. From the initial participants in the survey, we excluded the following: 1,307 who self-identified as meditators or reported having engaged in meditation within 6 months before the experiment, 776 who did not meet the English language proficiency requirement and 981 who disclosed having a history of mental illnesses. Finally, 1,660 participants started the survey without using a smartphone with headphones attached. Among these participants who failed to meet the inclusion criteria, 1,491 simultaneously met several exclusion criteria. Respondents who did not meet one or more inclusion criteria (n = 3, 233) were immediately directed towards the end of the survey and we did not record further data from them. We also removed from analyses those who initiated the survey but did not progress up to the listening of the audio track (n = 976) and the ‘test answers’ provided by the collaborating researchers while developing the survey (n = 19); thus, the sample size dropped to n = 2,463. We then removed data from 19 participants who dropped out of the experiment and data from 205 participants who, according to our criteria, were considered careless respondents, yielding a final sample of 2,239 valid observations. Of these, 611 participants self-identified as male, 1,576 as female, 7 as transgender male, 2 as transgender female, 27 did not identify with any choice and 16 preferred not to say (mean age (Mage) = 22.4, s.d.age = 10.1; range 17–87; 94.2% students), with an approximately even distribution across the five experimental conditions (nmindful walking = 416, nmindful breathing = 469, nloving kindness = 427, nbody scan = 449, nbook chapter control = 478). We are not aware of how many participants were invited to the survey but declined to participate.

Dealing with careless responders

We applied a set of rules to deal with responders39 who were careless or had made insufficient effort, to reduce the random variance component in the data. First, we made the answers for the questions connected to our exclusion criteria (meditation experience, English language proficiency and mental illnesses) compulsory. For the questionnaires related to our dependent variables/moderator, we alerted respondents about unanswered questions but they had the possibility to continue with the survey without providing a response. Second, the programmed survey prevented participants from skipping the 15 min audio file (for both mindfulness exercises and control conditions) by blocking the screen with the audio of the meditation/control condition for 14 min, so as not to allow participants to proceed to the following survey page until the meditation was finished. Third, we identified and excluded participants who provided identical responses to a long series of items (that is, always selecting the answer ‘strongly agree’) by performing a long-string analysis. Using long-string analyses, we excluded participants with a string of consistent responses equal to or greater than 10 (that is, half of the scale length).

Distribution of participants across sites

Thirty-seven sites participated in the data collection (see the full list at https://osf.io/uh3pk). Participants could be recruited through the SONA system (the platform used to recruit student participants from universities, https://www.sona-systems.com/) of the respective institution or via crowdsourcing platforms such as mTurk or Prolific. Participants could come from any geographic area if they met our inclusion criteria and could be given either credits or financial compensation in exchange for participating in the study.

Materials

Self-administered mindfulness interventions

To compile a list of self-administered mindfulness exercises to be tested in our multi-site project, we initially conducted a survey among mindfulness practitioners, whom we asked to recommend the most prominent and widely used exercises in their practice. We then retained the most popular exercises suggested by the surveyed practitioners, which we cross-referenced with the exercises included by Matko40 in an inventory of present popular mindfulness exercises. This combined approach led to the selection of four types of mindfulness exercises: body scan, mindful breathing, mindful walking and loving kindness meditation. The full procedure that led us to the selection of the four self-administered mindfulness exercises can be found in the extended preregistration document.

The four audio files of the mindfulness exercises and the three audio files of the stories of the non-mindful active control condition were recorded by the same certified meditation trainer, C. Spiessens, a BAMBA registered mindfulness teacher in MBSR (https://www.christophspiessens.com/) and each lasted 15 min. The exact text of the seven meditations and of the three stories used in the active control condition can be found on our OSF project page (https://osf.io/6w2zm/). The seven recordings can be found on the Soundcloud page of the project (https://soundcloud.com/listening-385769822).

Mindfulness conditions

In body scan, the meditation trainer invited participants to ‘scan’ their parts of the body. Every time the mind wandered, the meditation trainer invited participants to bring back the awareness and attention to the part of their body they were ‘scanning’. During mindful breathing, the meditation trainer invited participants to ‘stay with their breath’, without changing the way they were breathing. When their mind wandered, the meditation trainer invited participants to bring their attention back to their breath with kindness and patience. During the loving kindness meditation, the trainer encouraged participants to direct loving kindness toward themselves and then to extend these feelings of loving kindness towards somebody else. During mindful walking, the meditation trainer asked participants to walk in a quiet place (preferably indoors or in a place as isolated as possible from distractions), while listening to the instructions. During this practice, the meditation trainer invited participants to bring their awareness to the experience of walking and subsequently the meditation trainer invited them to ‘feel’ the physical sensations of contact of their feet with the ground.

Control conditions

Participants in the active control condition listened to an excerpt from ‘Silverview’ by John le Carré21 (word count 1,838), ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ by Ernest Hemingway41 (word count 2,039) or ‘Smith of Wootton Major’ by J. R. R. Tolkien22 (word count 2,309). We used more than one story excerpt to increase the variance of the control conditions and thus push towards greater generalizability across stimuli42. These three excerpts had a similar word count, were written in standard English, did not feature major plot changes and were thus unlikely to elicit strong emotions. Participants had equal chances of listening to any one of the three story excerpts.

Neuroticism

We measured this trait with the neuroticism subscale of the International Personality Item Pool five NEO domains, comprising 20 items43. Examples of items include ‘I often feel blue’ or ‘I am filled with doubts about things’ and answers ranged from 1 (very inaccurate) to 5 (very accurate; coefficient omega ωu = 0.90).

Stress

Participants answered the 20 item STAI Form Y-1 (ref. 19). They indicated how they felt in that exact moment on 20 items (for example, ‘I am tense’; ‘I feel frightened’; ωu = 0.92) on a 4-point scale (1, not at all; 2, somewhat; 3, moderately so; 4, very much so). By using the STAI Form Y-1 scale, we aimed to measure the short-term effects of stress on individuals. This scale, after all, has been shown to correlate with biomarkers of stress in previous research (salivary α-amylase44).

Emotion dimensions

Participants filled in the self-assessment manikin scale, a three-item non-verbal pictorial assessment technique which measures emotions on three different dimensions, namely pleasure, arousal and dominance45. The self-assessment manikin scale is the picture-oriented version of the widely used semantic differential scale46. This instrument measures the three-dimensional structure of stimuli, objects and situations with 18 bipolar adjective pairs which can be rated along a 9-point scale. This measure was not the primary dependent variable of our study but we added it in the study for the exploratory analyses.

Demographics

Participants provided information regarding their age, gender, country of birth, country of residence, whether they were students or not, which university they were studying at (for the former) and what was their current occupation (for the latter).

Simulation of the sequential Bayesian design

Before the data collection, we simulated data based on a Bayes factor design analysis to assess the expected efficiency and informativeness of the present design. The aim of the simulation was to establish (1) the expected likelihood of the study to provide compelling relative evidence either in favour of H0 (BF10 = 1/10) or H1 (BF10 = 10), (2) the likelihood of obtaining convincing but misleading evidence and (3) the likelihood that the study points into the correct direction even if stopped earlier due pragmatic constraints on sample size47.

Given these aims, we modelled a sequential design with a maximum n where the data collection continues until either the threshold for compelling evidence is met or the maximum n is reached. Although 41 laboratories indicated an interest in the project, we took the conservative estimate of 30 data-collecting laboratories. Each laboratory was expected to collect data of at least n = 70 participants, with a maximum n at 120 (translating to minimum 420 and maximum 720 participants per condition). Our goal was to be able to detect an effect size of d = 0.20; we modelled the true value to vary between laboratories by repeatedly (for each simulation) drawing from a normal distribution, δ ∼ n (0.20, 0.05), with a 95% probability that the effect size falls between d = 0.10 and 0.30.

We tested the effectiveness of four standalone interventions using a between-participants adaptive group design, whereupon hitting a threshold of compelling evidence in one condition, we planned to allocate the rest of the participants into other conditions where the threshold had not been met yet. The simulation, however, assumed a conservative scenario with equal n across all conditions, therefore, simplifying the computations to a single between-participants t-test scenario.

The results (Fig. 3) show that, given the assumed design, the probability of the test arriving at the boundary of compelling evidence (BF10 = 10 or 1/10) was 0.79 (0.72 at H1 and 0.07 erroneously at H0). The probability of terminating at a maximum n of 720 per condition was 0.21; 0.05 of showing some evidence for H1 (BF10 > 3), 0.13 of being inconclusive (3 > BF10 > 1/3) and 0.03 of showing evidence for H0 (BF10 < 1/3). For the test of a single condition against controls, the sequential design is expected to be 27% more effective than collecting a fixed maximum n per laboratory, with the average n at the stopping point (BF boundary and maximum n) at 526. Even conservatively assuming a balanced-n situation, the informativeness of the design thus appeared to be adequate and the use of the adaptive design would probably enhance informativeness and/or resource efficiency.

Procedure

Participants accessed the experiment via a Qualtrics link. We provided participants with detailed information about the study (see ‘Participants information sheet’ included in the IRB package, https://osf.io/6w2zm/) and asked for their consent to participate. We asked them to use a smartphone with headphones or earphones attached instead of a computer or laptop. We asked participants whether they started the survey from a device other than a smartphone; if they answered positively, we asked them to exit the survey and to restart it, this time using a smartphone with headphones or earphones attached. We then asked participants to sit in a quiet place such as a room where they would not be disturbed for 20 min. After providing informed consent, participants completed the neuroticism measure, then were randomly allocated by the Qualtrics algorithm to one of the four intervention conditions or one of the three control conditions, each lasting 15 min. On completion, participants answered the main study outcome, namely the stress measure and the self-assessment manikin scale. Finally, participants provided demographic information, were then thanked and debriefed and were awarded credit or payment depending on the site policy.

Analysis plan

To assess the effectiveness of the chosen mindfulness exercises against the control conditions at reducing stress in participants in an efficient manner, we carried out four independent-samples Bayesian t-tests to determine whether there was a difference between each mindfulness exercise and the active control condition. This study was originally conducted as a sequential Bayesian design48. The data were continuously monitored to see when each condition met the compelling evidence threshold of BF10 of 10 in favour of H1 or a BF10 of 1/10 in favour of H0. When we monitored the data, three out of four mindfulness exercises reached the BF10 threshold of 1/10 in favour of H0 before reaching the BF10 of 10 in favour of H1 as the sample increased. A detailed explanation of the sequential Bayesian design can be found in the extended preregistration document on the OSF page at https://osf.io/us5ae.

We used a two-tailed test using a non-informative Jeffreys–Zellner–Siow Cauchy prior for the alternative hypothesis with a default r-scale of √2/2 (ref. 49). To account for the hierarchical nature of the data, we compared the condition means using a Bayesian mixed-effects model which involved a random intercept for the site and for the different stories used in the non-mindful active control condition. We set our threshold of compelling evidence on the basis of which we would have drawn inferences about the results: a Bayes factor (BF10) of 10 in favour of H1 or a Bayes factor of 1/10 favoring H0. We chose a Bayes factor of 10 because, according to the classification of ref. 20, it demarcates the threshold between moderate and strong evidence. Here, using a Bayes factor of 10, we aimed to substantially decrease the probability of misleading evidence48. In the Bayesian analyses, we only engaged in comparative inference using Bayes factors (comparing the likelihood of the data under two competing hypotheses, H0 and H1) and for this reason we did not estimate posteriors. Finally, we decided not to screen for and exclude outliers and we did not perform any (nonlinear) transformations contingent on the observed data.

Exploratory analyses

We also carried out analyses exploring the effect of the experimental conditions on pleasure, arousal and dominance and for the moderating effect of neuroticism. We performed separate Bayesian t-tests for each dimension of the self-assessment manikin scale (pleasure, arousal and dominance) comparing our experimental conditions with the control condition. We then looked at the Bayes factor to establish whether the data favoured H1 or H0. We compared the means of the different conditions using a Bayesian mixed-effects model with a random intercept for laboratory and for the different stories used in the non-mindful active control condition to account for the hierarchical nature of the data.

To examine whether neuroticism moderated the effects of the four experimental conditions on stress, we compared the model with the interaction to the model with only the main effects (using the lmBF function) and we reported the corresponding BF10. If the model with the interaction was preferred to the model with only the main effects of a BF10 of 10 or more, we regarded it as solid evidence of the moderation of neuroticism on stress. We performed a similar analysis to investigate the potential moderation of English language proficiency on stress levels. The analyses for the current project were performed using RStudio v.2023.09.0 + 463.

Not preregistered analyses

Several analyses conducted in the ‘exploratory analyses’ section were not explicitly outlined in the preregistration. These additional analyses included the computation of heterogeneity and Cohen’s d for each condition when compared to the active control conditions and moderation effects by considering English language proficiency. Additionally, robustness analyses were incorporated at the reviewer’s request.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The preparation of this work was partly funded by Swansea University Strategic Partnerships Research Scholarships from School of Psychology, Swansea University awarded to G.M.J.-B., PRIMUS/24/SSH/017 and NPO ‘Systemic Risk Institute’ (LX22NPO5101) grants awarded to I.R. and NeuroCog ‘Project MIBODA’ from Université Grenoble Alpes awarded to H.I. R.M.R. was supported by the Australian Research Council (grant no. DP180102384) and the John Templeton Foundation (grant no. 62631). We also thank the SCREEN/MSH-Alpes platform for providing access to Qualtrics. The funders had no role in study conceptualization, design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

A.S., G.M.J.-B. and H.I. conceptualized this work. A.S., I.R. and F.G. undertook data curation. A.S., I.R. and F.G. were responsible for the formal analysis. H.I., I.R., R.M.R. and G.M.J.-B. acquired funding. B.N.U., J.L., T.T., S.J.D., J.L.D., J.S., J.D.P., R.M.R., Z.F., A.L., C.M.-K., M.B.F., K.S., C.C.W., W.C.H., B.M.S., S.K.S., G.R., P.T.F., V.J., A.K., P.Z., C.L.J., Y.K., M.A., C.F., M.F.B., H.B., A.B.E.B., M.D., C.E.N., J.C.B., C.M.G., J.M.B., S.M.G., S.D., W.E.D., T.J.W., W.B.M., J.L.H., L.S.R., M.G.S., S.S.D., S.P., S.S.-S., Z.I.W., M.V.D., S.B., A.H.L., C.E.H., L.V.O’B., T.U., J.S.M., K.L.v.d.S., H.B. and C.N.T.-W. undertook investigations. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I. and I.R. developed the methodology. A.S., G.M.J.-B. and H.I. were responsible for project administration. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I. and C.S. obtained resources. A.S. developed the software. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I. and I.R. supervised the project. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I. and I.R. undertook validation. A.S. produced the visualization. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I. and I.R. wrote the original draft. A.S., G.M.J.-B., H.I., I.R., R.M.R., S.J.D., G.R., W.B.M. and W.C.H. reviewed and edited the final paper. The certified mindfulness instructor (C.S.) only recorded the meditations and was not involved in writing any parts of the paper, including the other stages of the project (for example, choice of the analyses, data analysis).

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Marius Golubickis, Ivan Nyklicek and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

This project was preregistered on OSF on 22 March 2022, before the enrolment of the first participant (registration 10.17605/OSF.IO/UF4JZ). On editorial request, we retroactively registered our project as a clinical trial on ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06308744). Our data are available on the OSF (https://osf.io/6w2zm/) and via the GitHub repository (https://github.com/alessandro992/A-large-multi-site-test-of-self-administered-mindfulness). The data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0).

Code availability

The full analysis code is publicly available at https://github.com/alessandro992/A-large-multi-site-test-of-self-administered-mindfulness and on our OSF page (https://osf.io/6w2zm/).

Competing interests

H.I. is the director of a startup, Annecy Behavioral Science Lab, which seeks to promote human flourishing and social connection. He began in the startup when the manuscript was nearly finalized. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/9/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41562-024-01947-z

Contributor Information

Alessandro Sparacio, Email: Alessandro_Sparacio@sics.a-star.edu.sg.

Hans IJzerman, Email: hans@absl.io.

Ivan Ropovik, Email: ivan.ropovik@gmail.com.

Gabriela M. Jiga-Boy, Email: G.Jiga@swansea.ac.uk

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41562-024-01907-7.

References

- 1.Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life (Hyperion, 1994).

- 2.Cavanagh, K. et al. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention in a non-clinical population: replication and extension. Mindfulness9, 1191–1205 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabat-Zinn, J. in Mind/Body Medicine (eds Goleman, D. & Garin, J.) 257–276 (Consumer Reports, 1993).

- 4.Cavanagh, K., Strauss, C., Forder, L. & Jones, F. Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev.34, 118–129 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahbeh, H., Svalina, M. N. & Oken, B. S. Group, one-on-one, or Internet? Preferences for mindfulness meditation delivery format and their predictors. Open Med. J.1, 66–74 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spijkerman, M. P. J., Pots, W. T. M. & Bohlmeijer, E. T. Effectiveness of online mindfulness based interventions in improving mental health: a review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev.45, 102–114 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanagh, K. et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behav. Res. Ther.51, 573–578 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor, H., Strauss, C. & Cavanagh, K. Can a little bit of mindfulness do you good? A systematic review and meta-analyses of unguided mindfulness-based self-help interventions. Clin. Psychol. Rev.89, 102078 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glück, T. M. & Maercker, A. A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry11, 175 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparacio, A. et al. Stress regulation via self-administered mindfulness and biofeedback interventions in adults: a pre-registered meta-analysis. Preprint at PsyArXiv10.31234/osf.io/zpw28 (2024).

- 11.Feldman, G., Greeson, J. & Senville, J. Differential effects of mindful breathing, progressive muscle relaxation and loving-kindness meditation on decentering and negative reactions to repetitive thoughts. Behav. Res. Ther.48, 1002–1011 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutcherson, C. A., Seppala, E. M. & Gross, J. J. Loving-kindness meditation increases social connectedness. Emotion8, 720–724 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germer, C. K., Siegel, R. D. & Fulton, P. R. Mindfulness and Psychotherapy (Guilford Press, 2016).

- 14.de Vibe, M. et al. Does personality moderate the effects of mindfulness training for medical and psychology students? Mindfulness6, 281–289 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang, R. & Braver, T. S. Towards an individual differences perspective in mindfulness training research: theoretical and empirical considerations. Front. Psychol.11, 818 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giluk, T. L. Mindfulness, Big Five personality and affect: a meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif.47, 805–811 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simonsohn, U. No-Way Interactions (Authorea, 2015).

- 18.Lindquist, K. A., MacCormack, J. K. & Shablack, H. The role of language in emotion: predictions from psychological constructionism. Front. Psychol.6, 444 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spielberger, C. D., Gorshu, R. L. & Lushene, R. D. Test Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Consulting Psychologist Press, 1970).

- 20.Lee, M. D. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Bayesian Cognitive Modeling: A Practical Course (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

- 21.Le Carré, J. Exclusive extract from Silverview, John le Carré’s final novel. The Guardian (9 October 2021); www.theguardian.com/books/ng-interactive/2021/oct/09/they-told-me-i-was-grown-up-enough-to-keep-a-secret-exclusive-extract-from-silverview-john-le-carres-final-novel

- 22.Tolkien, J. R. R. Smith of Wootton Major (Redbook, 1967).

- 23.Economides, M., Martman, J., Bell, M. J. & Sanderson, B. Improvements in stress, affect and irritability following brief use of a mindfulness-based smartphone app: a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness9, 1584–1593 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, R. A. & Jung, M. E. Evaluation of an mHealth App (DeStressify) on university students’ mental health: pilot trial. JMIR Ment. Health5, e2 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundqvist, C., Ståhl, L., Kenttä, G. & Thulin, U. Evaluation of a mindfulness intervention for paralympic leaders prior to the paralympic games. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach.13, 62–71 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjureberg, J. & Gross, J. J. Regulating road rage. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass15, e12586 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carmody, J. & Baer, R. A. How long does a mindfulness‐based stress reduction program need to be? A review of class contact hours and effect sizes for psychological distress. J. Clin. Psychol.65, 627–638 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross, J. J. The extended process model of emotion regulation: elaborations, applications and future directions. Psychol. Inq.26, 130–137 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galante, J. et al. A mindfulness-based intervention to increase resilience to stress in university students (the Mindful Student Study): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health3, e72–e81 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., Thoresen, C. & Thomas, G. The moderation of mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Psychol.67, 267–277 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin-Aspenson, H. F. & Watson, D. Mode of administration effects in psychopathology assessment: analyses of gender, age and education differences in self-rated versus interview-based depression. Psychol. Assess.30, 287–295 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols, A. L. & Maner, J. K. The good-subject effect: investigating participant demand characteristics. J. Gen. Psychol.135, 151–165 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber, S. J. & Cook, T. D. Subject effects in laboratory research: an examination of subject roles, demand characteristics and valid inference. Psychol. Bull.77, 273–295 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bally, K., Campbell, D., Chesnick, K. & Tranmer, J. E. Effects of patient-controlled music therapy during coronary angiography on procedural pain and anxiety distress syndrome. Crit. Care Nurse23, 50–58 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berntson, G. G., Cacioppo, J. T. & Quigley, K. S. Cardiac psycho physiology and autonomic space in humans: empirical perspectives and conceptual implications. Psychol. Bull.114, 296–322 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simons, D. J., Shoda, Y. & Lindsay, D. S. Constraints on generality (COG): a proposed addition to all empirical papers. Perspect. Psychol. Sci.12, 1123–1128 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silan, M. A. et al. CO-RE Lab Lab Philosophy v5. Preprint at PsyArXiv10.31234/osf.io/6jmhe (2023).

- 38.Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (Council of Europe, 2001); https://rm.coe.int/1680459f97

- 39.Curran, P. G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol.66, 4–19 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matko, K. & Sedlmeier, P. What Is Meditation? Proposing an empirically derived classification system. Front. Psychol.10, 2276 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hemingway, E. The Old Man and the Sea (Life, 1952).

- 42.Judd, C. M., Westfall, J. & Kenny, D. A. Treating stimuli as a random factor in social psychology: a new and comprehensive solution to a pervasive but largely ignored problem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.103, 54–69 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg, L. R. et al. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J. Res. Pers.40, 84–96 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noto, Y., Sato, T., Kudo, M., Kurata, K. & Hirota, K. The relationship between salivary biomarkers and state-trait anxiety inventory score under mental arithmetic stress: a pilot study. Anesth. Analg.101, 1873–1876 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. Measuring emotion: the self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry25, 49–59 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehrabian, A. & Russell, J. A. An Approach to Environmental USA (MIT, 1994).

- 47.Schönbrodt, F. D., Wagenmakers, E. J., Zehetleitner, M. & Perugini, M. Sequential hypothesis testing with Bayes factors: efficiently testing mean differences. Psychol. Methods22, 322–339 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stefan, A. M., Gronau, Q. F., Schönbrodt, F. D. & Wagenmakers, E. J. A tutorial on Bayes factor design analysis using an informed prior. Behav. Res. Methods51, 1042–1058 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rouder, J. N., Speckman, P. L., Sun, D., Morey, R. D. & Iverson, G. Bayesian t tests for accepting and rejecting the null hypothesis. Psychon. Bull. Rev.16, 225–237 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This project was preregistered on OSF on 22 March 2022, before the enrolment of the first participant (registration 10.17605/OSF.IO/UF4JZ). On editorial request, we retroactively registered our project as a clinical trial on ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06308744). Our data are available on the OSF (https://osf.io/6w2zm/) and via the GitHub repository (https://github.com/alessandro992/A-large-multi-site-test-of-self-administered-mindfulness). The data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0).

The full analysis code is publicly available at https://github.com/alessandro992/A-large-multi-site-test-of-self-administered-mindfulness and on our OSF page (https://osf.io/6w2zm/).