Abstract

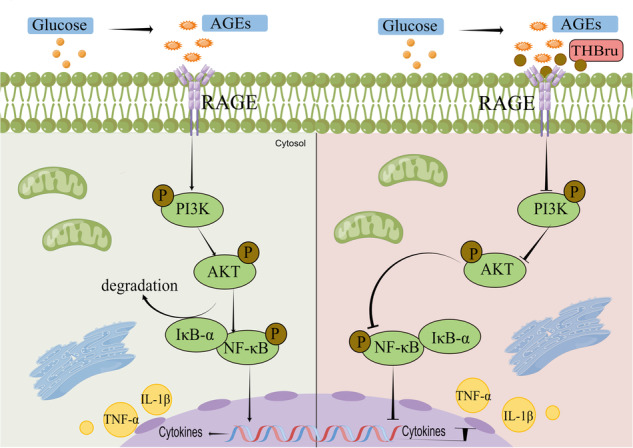

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a complication of diabetes mellitus characterized by heart failure and cardiac remodeling. Previous studies show that tetrahydroberberrubine (THBru) retrogrades cardiac aging by promoting PHB2-mediated mitochondrial autophagy and prevents peritoneal adhesion by suppressing inflammation. In this study we investigated whether THBru exerted protective effect against DCM in db/db mice and potential mechanisms. Eight-week-old male db/db mice were administered THBru (25, 50 mg·kg−1·d−1, i.g.) for 12 weeks. Cardiac function was assessed using echocardiography. We showed that THBru administration significantly improved both cardiac systolic and diastolic function, as well as attenuated cardiac remodeling in db/db mice. In primary neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs), THBru (20, 40 μM) dose-dependently ameliorated high glucose (HG)-induced cell damage, hypertrophy, inflammatory cytokines release, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. Using Autodock, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and DARTS analyses, we revealed that THBru bound to the domain of the receptor for advanced glycosylation end products (RAGE), subsequently leading to inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. Importantly, overexpression of RAGE in NMCMs reversed HG-induced inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway and subsequently counteracted the beneficial effects mediated by THBru. We conclude that THBru acts as an inhibitor of RAGE, leading to inactivation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. This action effectively alleviates the inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes, ultimately leading to ameliorated DCM.

Keywords: diabetic cardiomyopathy, tetrahydroberberrubine, RAGE, inflammation

Introduction

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a ventricular dysfunction that develops in diabetic people regardless of known cardiac risk factors such as coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, or hypertension [1]. As of 2021, it was estimated that approximately 537 million adults between the ages of 20 and 79 years worldwide had diabetes. However, projections indicate that this quantity is anticipated to increase to approximately 643 million by the year 2030 [2]. Moreover, it is estimated that nearly half of patients with well-regulated asymptomatic/normal blood pressure in diabetes exhibit cardiac insufficiency [3]. The scarcity of effective therapeutic interventions and the slow pace of drug development for DCM have resulted in its high morbidity rate [4]. Thus, it is imperative to thoroughly explore the underlying mechanisms and to prioritize the development of innovative therapeutic drugs to address the challenges posed by DCM.

Chronic inflammation is the predominant mechanism driving the onset of DCM. Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) have been consistently observed in diabetic patients and animal models. These cytokines actively participate in extensive tissue remodeling, thus ultimately leading to heart failure [5–7]. Receptor for advanced glycosylation end products (RAGE) is a transmembrane protein that belongs to the immunoglobulin (Ig) receptor superfamily [8]. The discovery of RAGE initially stemmed from its interaction with and facilitation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which represent the foundational contributors to diabetes-related complications. In addition to AGEs, RAGE functions as a pattern recognition receptor (PRR) with the remarkable ability to bind a diverse array of structurally unrelated endogenous and exogenous ligands, thus confirming its pivotal role as a regulator of inflammation [9–11]. In the context of DCM, AGE/RAGE-associated signaling is activated, thus resulting in the release of proinflammatory cytokines, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and other detrimental effects [8, 12]. Therefore, the targeting and inhibiting of key proteins within this signaling cascade holds significant therapeutic potential for mitigating inflammation and effectively treating DCM.

Tetrahydroberberine is synthesized by a semichemical synthesis in which berberine chloride is mono-demethylated by pyrolysis and then reduced by potassium borohydride. Our previous study showed that THBru retrogrades cardiac aging by promoting PHB2-mediated mitochondrial autophagy [13] and prevents peritoneal adhesion by suppressing inflammation [14]. Despite these encouraging results, the effectiveness of THBru in DCM has not been investigated. Moreover, the underlying mechanisms and direct targets of THBru in DCM remain unknown.

Our findings demonstrated that THBru attenuates DCM by directly binding to RAGE and inhibiting the RAGE/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB inflammatory pathway. These results highlight the therapeutic potential of THBru for managing DCM, thus providing more information on its molecular targets and underlying mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Animals

8-week-old male db/db mice were purchased from Beijing Viton Lihua Laboratory Animal Technology Co. Mice were kept in captivity under standard animal housing conditions (temperature, 23 ± 1 °C; humidity, 55%-60%); moreover, they were fed and watered ad libitum. The mice were randomly divided into five groups (n = 5 per group) as follows: the normal control group (control), DCM group (db/db), low-dose berberine derivative-treated DCM group (25 mg·kg−1·d−1, +THBru-L), high-dose berberine derivative-treated DCM group (50 mg·kg−1·d−1, +THBru-H), and metformin-treated DCM group (100 mg·kg−1·d−1, +MET). The drug was dissolved in distilled water containing 0.5% sodium carboxymethylcellulose and administered by gavage for 12 weeks. Cardiac function was measured at the 6th and 12th weeks. All of the procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Harbin Medical University (Protocol [2009]−11). The use of animals was compliant with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Reagents

Tetrahydroberberrubine was obtained from the Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Harbin Medical University. Berberine (1,8-dihydroxy-3-(hydroxymethyl)-anthraquinone) and rapamycin were purchased from Solarbio Co. (Beijing, China). In parallel, THBru, BBR and rapamycin were dissolved in 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide. The cells were treated with 20 µM THBru or 40 µM THBru. The cells were treated with 1.5 μM IMD0354 (CAS No. 978-62-1) for NF-κB inhibition.

Echocardiographic Analyses

Monitoring cardiac function in animals using a Vevo® 1100 High-Resolution Imaging System (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) ultrasound machine following anesthesia confirmation, as documented in prior studies [13]. Measurements related to cardiac function included the ejection fraction (EF%), fractional shortening (FS%), left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) thickness, interventricular septum (IVS) thickness, left ventricular internal dimension (LVID), and early-to-late transmitral filling velocity (E/A) ratio.

Histopathological and morphometric analysis

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections of cardiac tissue were used for histological analysis. Sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome to assess fibrosis. The sections were also stained with H&E for routine histological examination. The processed cardiac tissues were transversely cut into 5 μm thick sections, after which images were captured with a light microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany), and the relevant data were statistically analyzed by using ImageJ software.

Acquisition of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes (NMCMs)

Hearts were isolated from neonatal mice and digested overnight in D-Hanks solution containing 0.25% trypsin. After digestion was completed, we isolated cardiomyocytes and cultured them for 2 days in high-sugar Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin‒streptomycin to ensure a sterile environment at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. CFs were allowed to adhere for 1.5 h, and the bottle wall was gently blown to separate the nonadherent cardiomyocytes. Subsequent experiments were performed in an NMCMs cell culture flask. After drug treatment and incubation for 24 h, the cells were used for the experiments.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay

NMCMs were homogeneously inoculated into 96-well plates, and the effects of THBru on the cells were evaluated by using the CCK8 Cell Viability Assay Kit (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). Cells induced by high glucose were treated with THBru at various concentrations for 24 h. CCK8 solution was added to the medium containing the cells and incubated in an incubator for 60 min. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm by using an enzyme meter.

Transfection of pcDNA3.1-RAGE

The RAGE expression plasmid was cloned and inserted into the pcDNA3.1 vector by Shanghai Abbs Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The pcDNA3.1-RAGE vector was used to infect NMCMs with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA), and the serum-free medium was replaced with complete medium after 6–8 h.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from cells and tissues, and the total protein content was determined by using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The processed protein samples were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate‒polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose (NC) filter membranes. The membrane was blocked with Tris-buffered saline containing 5% skim milk for 2 h. The NC membrane was incubated with the specific primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with secondary antibodies for fluorescent labeling (1:10,000, LI-COR, NE, USA). The protein content was analyzed by using an Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR, NE, USA). A specific RAGE antibody (Abcam, Rabbit, monoclonal, 1:1000) was used. PI3K/p-PI3K, AKT/p-AKT, and NF-κB/p-NF-κB antibodies were used. Phosphorylated antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (rabbit, monoclonal, 1:1000).

Mouse Cytokine Array Panel A

A Mouse Cytokine Array Panel A (Bio-Techne China Co., Ltd.) was used for relative quantitative analysis of cytokines in mouse serum. Please refer to the official website for the specific operational steps (www.RnDSystems.com).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay measurement

We collected mouse serum and cell supernatants to measure the levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β. The plasma concentrations of TNF-α (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd) and IL-1β (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd) were measured via ELISA.

ROS detection

The cells were treated with nutrient-free medium, which was diluted according to the ratio for 24 h. The cell culture medium was removed, and 250 μL of diluted DCFH-DA was added. The cells were incubated in a constant temperature incubator for 0.3 h. The cells were washed with PBS three times and finally observed by using confocal microscopy.

SPR analysis

The COOH chip was mounted according to the SOP of the SPRTM instrument, and the run was initiated at the maximum flow rate (150 µl/min) by using HEPES (pH: 7.4) as the assay buffer. After the signal baseline was reached, the sample ring was washed with buffer, the signal baseline was reached, the buffer flow rate was adjusted to 20 µl/min, and the chip was activated by sampling EDC/NHS (1:1) solution. Afterwards, 200 µl of ligand diluted in activation buffer was sampled for 4 min, the binding was stabilized, the sample ring was cleaned with an appropriate amount of buffer, and 200 µl of the sealed solution was sampled. Subsequently, the sample ring was washed with buffer, the baseline was observed for 5 min, the sample ring was washed with buffer to ensure stability, and the baseline was observed for 5 min to ensure stability with buffer (200 × 10−6, 100 × 10−6, 50 × 10−6, 25 × 10−6, and 10 × 10−6 M). After upsampling at 20 µl/min, the protein binding time to the ligand was 240 s; moreover, the natural dissociation time was 360 s with the Open SPRTM instrument. The flow rate was increased to 150 µl/min, and appropriate regeneration buffer was added to remove the analytes.

Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) analysis

Cardiomyocytes were harvested from the myocardial tissue of neonatal mice aged 1–3 days, after which the cells were cultured. The cells were seeded in cell culture dishes prepared in advance. Subsequently, the total protein extracted from these cells was subjected to overnight incubation at 4 °C in the presence of different concentrations of THBru (0, 10, 20, and 40 μM). The following day, pronase (Cat# 10165921001, Roche) was added to the cell lysates at a final concentration of 1 ng/µg total protein, and the lysates were incubated at room temperature for 7 min. After incubation, an appropriate volume of 6× loading buffer was added to the samples, which were then immediately heated at 100 °C for 10 min to halt the enzymatic digestion. The prepared protein samples were subsequently subjected to immunoblot analysis.

WGA staining

Appropriately diluted fluorophore (such as FITC and Alexa Fluor)-labeled wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) working stock solutions were prepared in PBS or staining buffer. WGA staining solution was added to the fixed tissue, which was then incubated for 15–30 min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were washed with PBS to remove unbound WGA. The cells were also washed with PBS to remove excess dye and mounted with mounting medium. The stained cells were examined by using a fluorescence microscope or confocal microscope equipped with appropriate filters for the utilized fluorophores.

Molecular dynamics simulation

The crystal structure of the mouse RAGE structural domain (PDB code 4P2Y) was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. MGLTools 1.5.6 (The Scripps Research Institute, CA, USA) was used to prepare the initial structures of the ligand and receptor that were used for docking. Molecular docking was performed by using AutoDock Vina 1.0.2. Multiple binding conformations were obtained by sampling the binding conformation of THBru on the surface of the entire structural domain of RAGE. The binding capacity of each docking site of THBru was recovered by using the MM/GBSA method in the AmberTools20 software package. Finally, key residues for protein‒ligand interactions were identified based on disintegration energy calculations for each residue.

SERS

Raman spectral data were obtained by using a WITec alpha 300 R confocal Raman microscope (WITec GmbH, Germany). Reference samples were irradiated with a 633 nm laser at 5 mW for 3 s of integration. The instrument probed the spectral range of 0–3000 cm−1 with a CCD detector offering a 4 cm−1 spectral resolution. To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, scans were taken in triplicate with tenfold exposure.

Statistical analyses

All of the experimental procedures and data analysis were blinded. All of the data presented in this study are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Student’s t test was used for comparative analysis between two groups of data, and one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test were used for comparative analysis between four groups of data. GraphPad Prism version 8.2 was used for all of the statistical analyses. Significant differences are presented as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001.

Results

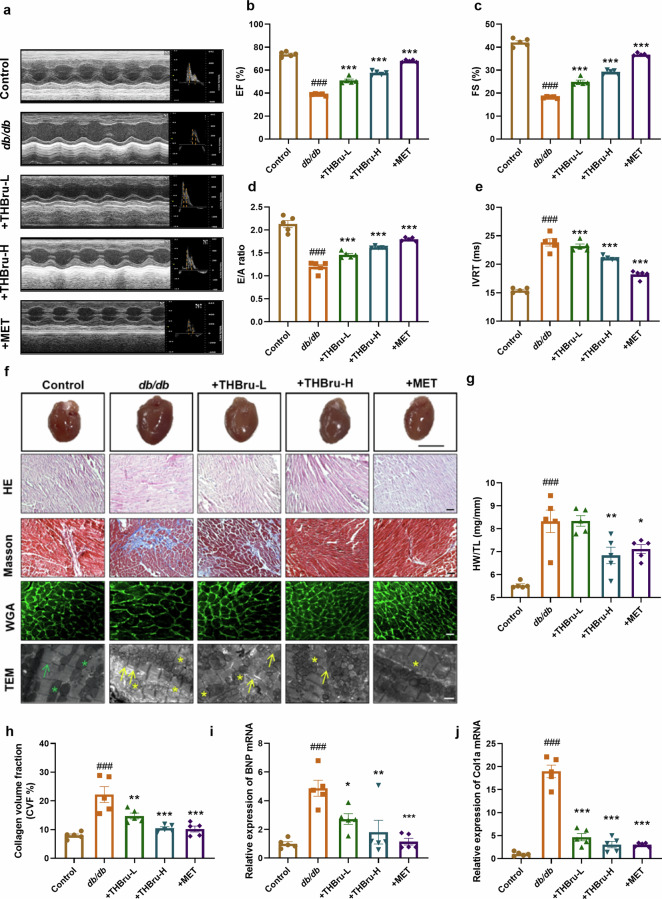

THBru improves cardiac dysfunction in db/db mice

We initially characterized the structure of THBru by using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) technology. The SERS spectrum of THBru demonstrated distinct Raman signals characterized by principal peaks at wavenumbers of 456 cm−1, 732 cm−1, 1148 cm−1, 1503 cm−1, and 1622 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S1). We presented the chemical bonds represented by the characteristic peaks in Supplementary Table 1. Different concentrations of THBru were administered to db/db mice by gavage for 12 weeks, whereas MET was used as the positive control drug. Cardiac function was assessed via echocardiography at the end of week 6 and week 12 in each group of mice. The results demonstrated a significant increase in the ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) of db/db mice at the end of the 6th week (Supplementary Fig. S2a–c), thus indicating that myocardial hypertrophy occurs in db/db mice at this stage, whereas the administration of THBru subsequently improved hypertrophy. After 12 weeks of treatment, the db/db mice progressed to severe heart failure (Fig. 1a), as indicated by decreased EF%, FS%, E/A ratio and increased IVRT (Fig. 1b–e). However, THBru afforded protection to both systolic and diastolic function. In addition, db/db mice displayed evident pathological cardiac remodeling, which was characterized by an increased heart-weight/tibial length (HW/TL) ratio, enlarged cardiomyocytes, loosely disorganized myocardial fibers, and collagen deposition. However, treatment with THBru notably mitigated cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac fibrosis in db/db mice (Fig. 1f–h). TEM micrographs provided further insights into the ultrastructural changes observed in the heart tissue. The images demonstrated disorganized sarcomeres and swollen mitochondria in cardiomyocytes from db/db mice (Fig. 1f). However, administration of THBru effectively reversed these pathological alterations. We then assessed the expression of the cardiac pathological markers BNP and Col1a, which are commonly associated with heart dysfunction. The significant downregulation of both BNP and Col1a expression further confirmed the therapeutic potential of THBru in attenuating DCM (Fig. 1i, j). Furthermore, we evaluated the effects of THBru on body weight and blood glucose levels. The results indicated that THBru had minimal effects on both parameters, whereas MET significantly reduced them (Supplementary Fig. S2d, e), which suggested that the therapeutic effects of THBru on DCM were not attributed to glucose and lipid lowering effects.

Fig. 1. THBru improves cardiac dysfunction in db/db mice.

a Representative echocardiographic images showing the echocardiograms and ratio of the E/A ratio for assessment of cardiac function in db/db mice. b Statistical results for EF, an indicator of cardiac systolic function in mice. n = 5. c Statistical results for FS, an indicator of cardiac systolic function in mice. n = 5. d Statistical results of E/A ratio, an indicator of cardiac diastolic function in mice. n = 5. e Statistical results for IVRT,an indicator of cardiac diastolic function in mice. n = 5. f Histopathological changes and collagen deposition were assessed by H&E (magnification 200×, Scale bar:100 μm), Masson trichrome (magnification 200×, Scale bar:100 μm), WGA (magnification 200×, Scale bar:100 μm) and electron microscopy. The green arrow indicates normal sarcomeres, yellow arrows indicate normal sarcomeres, green asterisk indicates normal mitochondria, yellow asterisk indicates mitochondrial swelling. (magnification 2500×, Scale bar: 10 μm) (g) Statistical results for HW/TL. (Scale bar: 0.5 cm). n = 5. h Statistical results for fibrosis as revealed by Masson staining. n = 5. i qPCR verification of BNP. n = 5. j qPCR verification of Col1a. ###P < 0.001 vs. control; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. db/db. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

THBru directly binds RAGE and modulates the expression of RAGE protein

To determine how THBru protects diabetic hearts, we predicted potential drug targets of THBru by using Swiss Targetprediction. KEGG enrichment analysis was used to analyze the regulatory signaling pathways associated with THBru. The analysis revealed significant enrichment of the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway (Fig. 2a), thus indicating the potential involvement of RAGE as a target for therapeutic intervention by THBru. SPR quantification demonstrated the strong binding ability of THBru to RAGE, with a dissociation constant (KD) of 5.09e−5 (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, DARTS analysis provided additional evidence supporting the specific interaction between THBru and RAGE (Fig. 2c, d). To further explore the regulatory effect of THBru on RAGE, Western blot analysis was used to detect the expression of RAGE in the hearts of different groups of mice. RAGE protein levels were significantly greater in the db/db group than in the control group. However, treatment with THBru led to a decrease in RAGE protein levels, thus indicating that THBru can modulate RAGE expression (Fig. 2e). In addition, we utilized the RAGE crystal structure for global docking (Fig. 2f). To elucidate the stability and kinetics of the docked complexes, we performed 100 ns MD simulations of the complexes at 300 K and 1 atmosphere. Six residues were identified as being essential for maintaining the stability of the complex: 24-GLN, 26-ILE, 29-ARG, 36-LEU, 37-LYS, and 113-TYR (Fig. 2g). The results are shown as the root mean square deviation (RMSD) and the distance between residues and THBru. The RMSD was used to analyze the stability of the RAGE protein. The RMSD of the RAGE protein (Fig. 2h) and THBru (Supplementary Fig. S3a) showed slight fluctuations in the simulation. The distance between these six major residues and THBru (Fig. 2i) was less than 10 Å, and the RMSF results (Supplementary Fig. S3b) also showed that these six residues were relatively stable during the simulation.

Fig. 2. THBru directly binds to RAGE and modulates the expression of RAGE protein.

a KEGG enrichment of THBru banding protein. b SPR quantification analysis of THBru with RAGE. c, d The protein expression changes of RAGE in DARTS (Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability) analysis. n = 3. ***P < 0.001 vs. THBru 0. e Western blot analysis of the protein level of RAGE in mice heart. n = 5. ###P < 0.001 vs. control; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. db/db. f The binding pocket of THBru on RAGE. g The key residues with the lowest binding energy. h RMSD of the docked complex reflects the stability of the protein. i The distance between the residues and THBru. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

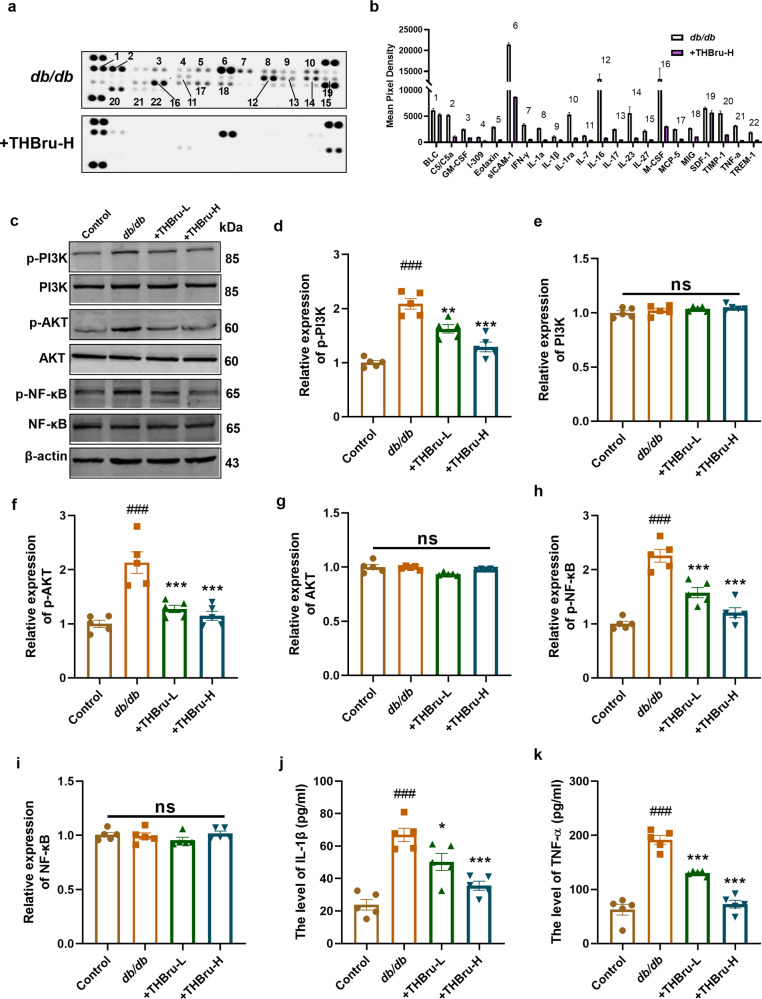

THBru reduces inflammatory responses in db/db mice by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway

RAGE interacts with AGEs and plays a critical role in regulating the inflammatory response. Thus, we used a Multiplex Mouse Cytokine ELISA Kit to detect inflammatory factors influenced by THBru in the context of DCM. Compared with those in the db/db group, the levels of a number of inflammation-related factors were significantly reduced after THBru administration (Fig. 3a, b). It is widely acknowledged that RAGE plays a crucial role in activating inflammatory responses through the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway. Our data consistently demonstrated the activation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway upon RAGE overexpression in cardiomyocytes under high glucose (HG) conditions (Supplementary Fig. S4a–g). Moreover, treatment with the NF-κB inhibitor IMD0354 notably inhibited cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and attenuated the production of ROS induced by RAGE overexpression (Supplementary Fig. S5a–c). In conjunction with this effect, Swiss Targetprediction-based GO analysis of the potential drug targets of THBru suggested the potential regulatory effects of THBru on the PI3K signaling pathway (Supplementary Fig. S6a). Furthermore, protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network analysis demonstrated strong interactions between the dysregulated inflammatory cytokines affected by THBru and NF-κB (Supplementary Fig. S6b). Based on these findings, we investigated the activation of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway following treatment with THBru. Western blot analysis demonstrated that THBru treatment significantly inhibited the activation of PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling in the hearts of db/db mice, which was evident from the reduced expression of p-PI3K, p-Akt, and p-NF-κB (Fig. 3c–i). Furthermore, we validated the upregulation of two crucial inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and TNF-α) in the serum of db/db mice. Notably, the administration of THBru resulted in significantly lower serum levels of these cytokines (Fig. 3j, k). These findings offer direct evidence supporting the involvement of the RAGE/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway in the protective effects of THBru on DCM.

Fig. 3. THBru reduces inflammatory responses in db/db mice by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway.

a Multiplex mouse Cytokine ELISA Kit to detect mouse serum inflammatory factors. b Statistical results of changed inflammatory factors. c–i Western blot analysis of the protein level of phosphorylation (p-) and total PI3K, AKT, and NF-κB in mice heart. n = 5. j IL-1β levels in serum tested by Elisa. n = 5. k TNF-α levels in serum tested by Elisa. n = 5. ###P < 0.001 vs. control; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. db/db. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

THBru ameliorates cardiomyocyte damage and the inflammatory response induced by high glucose (HG)

We subsequently investigated the protective effect of THBru on cardiomyocytes under HG conditions. The CCK-8 assay demonstrated that HG induced a notable decrease in cell viability, whereas THBru treatment effectively improved the reduction in cell viability, even at a low concentration of 20 μM (Fig. 4a). Cardiomyocytes produce massive amounts of ROS in a high-glucose environment. We found that THBru effectively reduced HG-induced ROS production in primary cardiomyocytes (Fig. 4b). Afterwards, we stained primary cardiomyocytes with α-actinin to measure cell size and confirm CM hypertrophy. As expected, we observed an increase in cell size after HG exposure, and this increase was reversed in cells pretreated with THBru (Fig. 4c, d). Furthermore, an inflammatory response was detected in cardiomyocytes; moreover, consistent with the in vivo data, the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the cell culture medium were found to increase upon exposure to high glucose (HG). However, treatment with THBru successfully prevented the increase in TNF-α and IL-1β levels (Fig. 4e, f). These findings provide compelling evidence that THBru exerts a protective effect against HG-induced cell damage and inflammation.

Fig. 4. THBru ameliorates cardiomyocyte damage and inflammatory response induced by high glucose.

a CCK8 was used to detect cell viability of NMCMs after THBru treatment for 24 h. n = 5. b Representative imagies of ROS production in NMCMs. (magnification 100×, scale bar:20 μm). n = 5. c Immunofluorescence staining of NMCMs for α-actinin (green). (magnification 400×, scale bar:20 μm). n = 5. d Statistical results for cell area. n = 5. e TNF-α levels in cell culture medium tested by Elisa. n = 5. f IL-1β levels in cell culture medium tested by Elisa. n = 5. ###P < 0.001 vs. control; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. HG. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

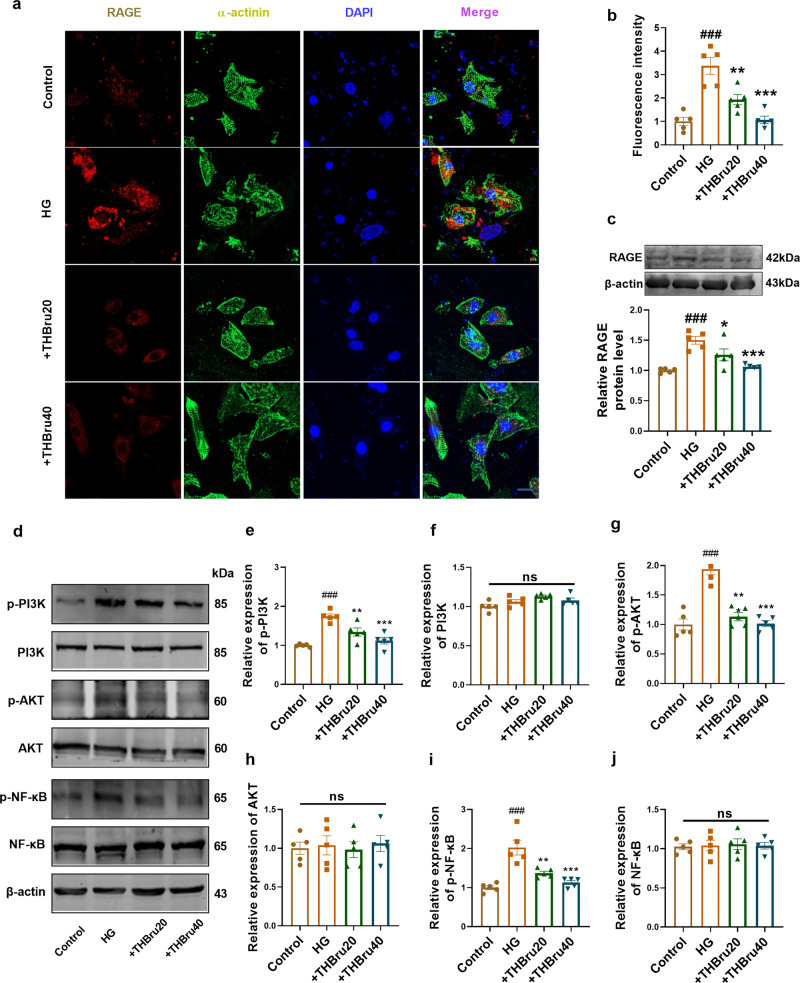

THBru inhibits the RAGE-dependent signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes exposed to HG

To further elucidate the regulatory mechanisms underlying the protective effects of THBru on HG-induced cardiomyocytes, we measured the expression of signaling proteins involved in RAGE-dependent pathways. The immunofluorescence and Western blot results showed that the expression of RAGE was significantly increased by HG treatment but was significantly inhibited by THBru (20 μmol/L, 40 μmol/L) (Fig. 5a–c). Additionally, we assessed the activation of PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling, which is regulated by RAGE. Western blot analysis demonstrated that HG treatment increased the activation of PI3K/AKT/NF-κB signaling molecules, whereas pretreatment with THBru effectively reduced the activation levels of these molecules (Fig. 5d–j). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated a decrease in NF-κB nuclear localization following THBru treatment, thus providing additional support for the inhibitory effects of THBru on NF-κB activation (Supplementary Fig. S7a, b).

Fig. 5. THBru Inhibits RAGE-dependent signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes exposed to HG.

a Immunofluorescence staining of NMCMs for RAGE (red). (magnification 400×, scale bar:10 μm). n = 5. b Statistical results for RAGE staining. n = 5. c Western blot analysis of the protein level of RAGE in NMCMs. n = 5. d–j Western blot analysis of the protein level of phosphorylation (p-) and total PI3K, AKT, and NF-κB with RAGE overexpression. n = 5. ###P < 0.001 vs. control; *P < 0.01, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. HG. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

RAGE overexpression reversed the protective effects of THBru in HG-treated cardiomyocytes

We then investigated the effects of RAGE overexpression on the protective effects of THBru. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that THBru effectively attenuated HG-induced CM hypertrophy; however, this effect was reversed upon RAGE overexpression (Fig. 6a, b). Moreover, THBru reduced HG-induced ROS production in cardiomyocytes, but this protective effect was diminished by RAGE overexpression (Fig. 6c, d). Additionally, the overexpression of RAGE abolished the inhibitory effect of THBru on the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway (Fig. 6e–k). These findings provide convincing evidence that THBru exerts its anti-inflammatory effects on HG-induced cardiomyocytes by specifically targeting RAGE.

Fig. 6. Overexpression of RAGE reversed the protective effects of THBru in HG-treated cardiomyocyte.

a Immunofluorescence staining of NMCMs for α-actinin (green). (magnification 400×, scale bar:20 μm). n = 5. b Statistical results for cell area. n = 5. c Representative imagies of ROS production with RAGE overexpression in NMCMs. (magnification 200×, Scale bar:50 μm). n = 5. d Statistical results of ROS production in NMCMs. n = 5. e–k Western blot analysis of the protein level of phosphorylation (p-) and total PI3K, AKT, and NF-κB with RAGE overexpression. n = 5. ***P < 0.001 vs. HG; &&&P < 0.001 vs. +HG+THBru. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Myocardial inflammation plays a crucial role in the development of diabetes-induced cardiac insufficiency [4, 15]. In this study, we demonstrated the effectiveness of THBru in preventing cardiac damage in DCM patients. Our findings indicate that THBru exerts its cardioprotective effects by directly binding to the RAGE protein, thereby inhibiting the activation of RAGE-dependent proinflammatory signaling pathways. This cardioprotective effect of THBru was further confirmed in HG-treated cardiomyocytes. These findings emphasize the potential of THBru as a promising therapeutic agent to attenuate the inflammatory response in DCM.

Consistent with previous studies, db/db mice exhibited significantly elevated blood glucose levels and cardiac dysfunction, which were characterized by abnormal systolic and diastolic function [16]. Moreover, these mice exhibited cardiac remodeling, including cardiac hypertrophy, extensive collagen deposition and structural damage. These findings confirm the scientific success of the DCM mouse model in the present study [12, 17]. Our study demonstrated that both 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg THBru effectively ameliorated cardiac dysfunction and cardiac remodeling and enhanced the viability of cardiomyocytes. Notably, these findings were consistent with our previously published study, as evidenced by its ability to attenuate diastolic dysfunction, cardiac hypertrophy, and cardiac senescence in naturally aged mice at the same doses. In support of the safety and efficacy of THBru, a study conducted by Xiu Yu demonstrated that a dose of 50 mg/kg THBru effectively mitigated LPS-induced acute lung injury [18]. Collectively, these results further reinforce the notion that both 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg THBru exhibit promise as safe and effective therapeutic options for cardiac protection.

Furthermore, THBru did not exert a meaningful influence on blood glucose levels or body weight in diabetic mice. This finding suggested that the beneficial effects of THBru in treating DCM are not solely attributed to a decrease in blood glucose levels. These findings indicate that the ability of THBru to ameliorate heart injury plays a crucial role in its therapeutic mechanisms. Consistent with these findings, our findings supported the beneficial effects of THBru in HG-treated primary cardiomyocytes, as THBru enhanced cell viability, reduced ROS production, and ameliorated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. These observations further underscore the cardiomyocyte-targeting effects of THBru in mitigating DCM. Accumulating evidence has consistently demonstrated that ameliorating cardiomyocyte injury is a promising therapeutic strategy for treating DCM. For instance, Jin et al. demonstrated that exercise enhances the cardioprotective actions of FGF21 by regulating SIRT3/AMPK/FOXO3 signaling, thereby ameliorating oxidative stress and energy disorders in cardiomyocytes and effectively reversing DCM [17]. Additionally, sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is), which represent a novel category of diabetes medication, have shown cardiovascular benefits based on clinical data. Arow et al. reported that SGLT2I exerted cardioprotective effects in ATII-stressed diabetic mice by reducing oxygen radicals and inflammation in cardiomyocytes, thus leading to the amelioration of DCM. However, whether THBru has beneficial effects on other heart cells in DCM, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages, remains an important research area for future studies.

An important discovery of this study was the identification of the interactions between THBru and RAGE. Swiss TargetPrediction is a computational tool that predicts potential protein targets for compounds by comparing their two-dimensional and three-dimensional structures to known compounds. By utilizing this approach, we were able to identify 101 proteins that exhibit binding affinity for THBru. Further analysis using KEGG enrichment indicated a notable enrichment of these proteins in the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway. This finding strongly suggested that THBru may exert its effects by modulating the binding interactions of these proteins within the pathway. To further validate this hypothesis, we employed two complementary techniques: surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and molecular docking. SPR analysis demonstrated that at a concentration of 25 μM, THBru exhibited a notable binding interaction with RAGE. This result provides experimental evidence supporting the specific interaction between THBru and RAGE. Additionally, the findings obtained from molecular docking simulations supported the stability of the THBru-RAGE complex, thus further reinforcing the notion of a stable binding interaction between the two entities. The extracellular domain of RAGE consists of three Ig structural domains (V, C1, and C2), with the V structural domain considered to be the primary ligand-binding structural domain, and a number of ligands have also been shown to interact with the C1 or C2 structural domains, including S100A6, S100A12, and S100A13. We found that THBru binds to RAGE in a complex to induce the unique dimeric conformation of RAGE and affect its signal transduction. Remarkably, THBru treatment effectively decreased RAGE protein levels at both the tissue and cellular levels, which further confirmed their interaction.

RAGE can interact with a multitude of proinflammatory ligands, including AGEs, that aggregate in diabetic tissues, thereby initiating downstream inflammatory signaling pathways. Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the upregulation of myocardial RAGE expression in DCM. This upregulation subsequently modulates inflammatory signaling pathways mediated by AMPK, AKT, and NF-κB, thereby upregulating the production of inflammatory factors and inducing myocardial cell injury [3, 19]. Additionally, RAGE serves as an effective target for drug intervention in DCM. Drugs such as dapagliflozin, vitamin D, and the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor enpalifloxacin have been shown to mitigate myocardial inflammation by suppressing RAGE levels and effectively treating DCM [9, 20, 21]. Our findings further validated the upregulation of RAGE expression in the myocardial tissue of db/db mice and HG-induced injured cardiomyocytes. Moreover, THBru significantly suppressed RAGE expression. This observation suggested that RAGE is involved in the therapeutic effect of THBru for treating DCM, thus suggesting that THBru is a potential candidate inhibitor of RAGE for managing related diseases.

In our previous study, we demonstrated an additional pharmacological mechanism of THBru; specifically, this mechanism involves its ability to protect against cardiac senescence by enhancing the stability of PHB2 mRNA [22]. A potential limitation of the current study is that we did not investigate whether THBru exerts its anti-DCM effects by specifically targeting PHB2. A study conducted by Li et al. showed that the expression of PHB2 was not altered in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells treated with HG, thus suggesting that the inhibitory effect of THBru on PHB2 may be ineffective for DCM. However, further investigation is still required to confirm this inference and determine the potential mechanisms underlying the effects of THBru on DCM.

The pivotal molecular function of RAGE is its mediation of proinflammatory signaling [23]. Consistent with these findings, our findings consistently demonstrated that THBru effectively inhibited the generation of several inflammatory cytokines, including ICAM-1, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. Numerous studies have established a correlation between the blood levels of inflammatory cytokines and the progression of DCM [24]. The levels of proinflammatory markers, such as IL-6, IL-18, IL-10, TNF-α, and CPR, as well as monocyte production of IL-1 receptor agonists, which can inhibit adiponectin mRNA expression and adiponectin secretion in adipose tissue, are elevated in T2DM patients; moreover, low levels of adiponectin are associated with T2DM [25, 26]. Therefore, the subsets of inflammatory cytokines that were identified in this study and that are effectively suppressed by THBru may serve as blood biomarkers for DCM and as indicators of the therapeutic efficacy of DCM treatments. Subsequently, we investigated the involvement of the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB inflammatory pathway, which is a well-recognized signaling cascade activated by RAGE. We observed significant activation of this signaling pathway in the myocardial tissues of db/db mice and damaged cardiomyocytes. Importantly, treatment with THBru effectively deactivated this inflammatory pathway cascade. However, when RAGE was overexpressed, the inhibitory effects of THBru on this pathway were abolished. These findings emphasize the therapeutic potential of THBru for the treatment of RAGE-related diseases and inflammation-related diseases.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our investigation demonstrated that THBru, an inhibitor of RAGE, effectively exerted cardioprotective effects by attenuating CM inflammation through the regulation of the RAGE/PI3K/AKT/NF-κB inflammatory signaling cascade. These findings suggest that THBru is a promising potential therapeutic compound for ameliorating cardiac dysfunction in diabetes patients.

Supplementary information

Figure legends for supplementary figures

Author contributions

Design of the study: XL, YZ. Performance of the experiments: HHX, SXH, HYS, XXD, YL, HL, LMZ, PPT, ZJD, JJH, MHD, ZXC. Analysis of the data: HHX, SXH. Writing—original draft: HHX. Writing—review & editing: HHX, SXH, HYS, YL,HL, LMZ, PPT, ZJD, JJH, MHD. ZXC, PK, DS, XL, YZ.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273919, 82270396), the HMU Marshal Initiative Funding (HMUMIF-21022) and the Science Foundation for the Excellent Youth Scholars of Heilongjiang Province (JJ2023YX0509).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All of the authors have declared their consent for this publication.

Ethics approval

The use of animals was approved by the Ethics Committees of Harbin Medical University and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: “In this article fig. 1 as well as the legends of the supplementary figures have been updated.”

These authors contributed equally: Heng-hui Xu, Sheng-xin Hao, He-yang Sun

Change history

1/23/2025

The original online version of this article was revised: "In this article fig. 1 as well as the legends of the supplementary figures have been updated."

Change history

1/30/2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41401-025-01483-0

Contributor Information

Xin Liu, Email: freyaliuxin@163.com.

Yong Zhang, Email: hmuzhangyong@hotmail.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-024-01307-7.

References

- 1.Chiao Y, Chakraborty A, Light C, Tian R, Sadoshima J, Shi X, et al. NAD redox imbalance in the heart exacerbates diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Heart Fail. 2021;14:e008170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Yang Q, Huang Z, Liang C, Zhang DH, Shi HT, et al. Dual-specificity phosphatase 12 attenuates oxidative stress injury and apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy via the ASK1-JNK/p38 signaling pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;192:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Y, Zhang H, Dai X, Zhu R, Chen B, Xia B, et al. A comprehensive review on the phytochemistry, pharmacokinetics, and antidiabetic effect of Ginseng. Phytomedicine. 2021;92:153717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Escobar-Lopez L, Ochoa J, Royuela A, Verdonschot J, Dal Ferro M, Espinosa M, et al. Clinical risk score to predict pathogenic genotypes in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:1115–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali T, Rahman S, Hao Q, Li W, Liu Z, Ali Shah F, et al. Melatonin prevents neuroinflammation and relieves depression by attenuating autophagy impairment through FOXO3a regulation. J Pineal Res. 2020;69:e12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bopp C, Bierhaus A, Hofer S, Bouchon A, Nawroth PP, Martin E, et al. Bench-to-bedside review: The inflammation-perpetuating pattern-recognition receptor RAGE as a therapeutic target in sepsis. Crit Care. 2007;12:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu LM, Dong X, Xue XD, Xu S, Zhang X, Xu YL, et al. Melatonin attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy and reduces myocardial vulnerability to ischemia‐reperfusion injury by improving mitochondrial quality control: role of SIRT6. J Pineal Res. 2020;70:e12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kierdorf K, Fritz G. RAGE regulation and signaling in inflammation and beyond. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thakur V, Alcoreza N, Delgado M, Joddar B, Chattopadhyay M. Cardioprotective effect of glycyrrhizin on myocardial remodeling in diabetic rats. Biomolecules. 2021;11:569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanajou D, Ghorbani Haghjo A, Argani H, Aslani S. AGE-RAGE axis blockade in diabetic nephropathy: current status and future directions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;833:158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalea AZ, Schmidt AM, Hudson BI. RAGE: a novel biological and genetic marker for vascular disease. Clin Sci. 2009;116:621–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronlage M, Dewenter M, Grosso J, Fleming T, Oehl U, Lehmann L, et al. O-GlcNAcylation of histone deacetylase 4 protects the diabetic heart from failure. Circulation. 2019;140:580–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Tang X, Shi Y, Li H, Meng Z, Chen H, et al. Tetrahydroberberrubine retards heart aging in mice by promoting PHB2-mediated mitophagy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022;44:332–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Liu H, Xu H, Sun H, Xu H, Han J, Zhao L, et al. Tetrahydroberberrubine prevents peritoneal adhesion by suppressing inflammation and extracellular matrix accumulation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;954:175803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chavakis T, Bierhaus A, Al-Fakhri N, Schneider D, Witte S, Linn T, et al. The Pattern Recognition Receptor (RAGE) is a counterreceptor for leukocyte integrins. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1507–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lew JK-S, Pearson JT, Saw E, Tsuchimochi H, Wei M, Ghosh N, et al. Exercise regulates microRNAs to preserve coronary and cardiac function in the diabetic heart. Circ Res. 2020;127:1384–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Yin Y, Wang S, Zhao T, Gong F, Zhao Y, et al. FGF1 prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress via AMPK/Nur77 suppression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu X, Yu S, Chen L, Liu H, Zhang J, Ge H, et al. Tetrahydroberberrubine attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by down-regulating MAPK, AKT, and NF-κB signaling pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derakhshanian H, Djazayery A, Javanbakht MH, Eshraghian MR, Mirshafiey A, Jahanabadi S, et al. Vitamin D downregulates key genes of diabetes complications in cardiomyocyte. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:21352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yue Z, Li L, Fu H, Yin Y, Du B, Wang F, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on diabetic patients with cardiovascular disease via MAPK signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:7500–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TW, Kao YH, Chen YJ, Chao TF, Lee TI. Therapeutic potential of vitamin D in AGE/RAGE-related cardiovascular diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:4103–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S, Liu M, Chen J, Chen Y, Yin M, Zhou Y, et al. L‐carnitine alleviates cardiac microvascular dysfunction in diabetic cardiomyopathy by enhancing PINK1‐Parkin‐dependent mitophagy through the CPT1a‐PHB2‐PARL pathways. Acta Physiol. 2023;238:e13975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, Wen Y, Wang L, Chen B, Chen J, Wang H, et al. Hyperglycemia-induced accumulation of advanced glycosylation end products in fibroblast-like synoviocytes promotes knee osteoarthritis. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53:1735–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francisco V, Sanz MJ, Real JT, Marques P, Capuozzo M, Ait Eldjoudi D, et al. Adipokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: are we on the road toward new biomarkers and therapeutic targets? Biology. 2022;11:1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruun JM, Lihn AS, Verdich C, Pedersen SB, Toubro S, Astrup A, et al. Regulation of adiponectin by adipose tissue-derived cytokines: in vivo and in vitro investigations in humans. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E527–E33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf AM, Wolf D, Rumpold H, Enrich B, Tilg H. Adiponectin induces the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA in human leukocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure legends for supplementary figures

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.