Abstract

Racism pervades the US criminal legal and family policing systems, particularly impacting cases involving women with a history of a substance use disorder (SUD). Laws criminalizing SUD during pregnancy disproportionately harm Black women, as do family policing policies around family separation. Discrimination within intersecting systems may deter Black pregnant women with a SUD from seeking evidence-based pregnancy and substance use care. This convergent parallel mixed-methods study aimed to illuminate how systemic oppression influenced the lived experiences of Black mothers with a SUD, facing dual involvement in the criminal legal and family policing systems. Using convenience and snowball sampling techniques, we recruited 15 Black mothers who were incarcerated, used substances while pregnant, and had a history with family policing systems. We conducted semi-structured interviews and developed and distributed a scale questionnaire to describe participants’ experiences navigating overlapping systems of surveillance and control. Drawing on models of systemic anti-Black racism and sexism and reproductive justice, we assessed participants’ experiences of racism and gender-based violence within these oppressive systems. Participants described how intersecting systems of surveillance and control impeded their prenatal care, recovery, and abilities to parent their children in gender and racially specific ways. Although they mostly detailed experiences of interpersonal discriminatory treatment, particularly from custody staff while incarcerated and pregnant, participants highlighted instances of systemic anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism while accessing prenatal care and substance use treatment in carceral and community settings. Their narratives emphasize the need for action to measure and address the upstream macro-level systems perpetuating inequities.

Keywords: Substance use treatment, Family policing, Incarceration, Pregnancy, Anti-Black racism, Sexism

Introduction

Incarceration rates among women in the USA continue to rise, with the disproportionate burden of incarceration falling on Black women1 [1, 2]. US incarceration rates for all women increased at an alarmingly rapid pace, with more than a 500% increase between 1980 and 2022 [1]. Although Black women make up only 15% of the total US female population, they account for nearly 30% of incarcerated women [1, 2]. Despite this statistical reality, their perspectives and experiences are excluded in solutions addressing systemic inequities within the criminal legal system. This is particularly true for Black pregnant and postpartum women with a history of substance use disorder (SUD), whose prenatal care, substance use treatment, and social service needs are shaped by overlapping systems of oppression.

Black feminist scholars have long argued that Black women experience a particular type of oppression that is not based on their race or gender alone [3–6]. We use the theoretical framing of “gendered racism” to denote the intersection of racial and gender oppression that creates distinct experiences for Black women [7]. Anti-Black gendered racism creates a double burden for Black women with a SUD, as they not only grapple with the shame, stigma, and stereotypes associated with using substances, but they also experience gendered racism across multiple interrelated systems, such as the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems.

To grasp the full significance of anti-Black gendered racism in the lives of these individuals, it is essential to contextualize it within the broader narrative of mass incarceration and its consequences for Black women and mothers. Mass incarceration in the USA has led to imprisoning more people than any other nation in the world [8]. The “war on drugs” has been a driver of the fast-growing rates of incarceration among Black people, leading to devastating consequences for Black women, their families, and their communities [8, 9]. For example, in 2003, Regina McKnight, a Black woman from South Carolina, was the first woman in the USA to be detained, indicted, and convicted of homicide by child abuse because she experienced a stillbirth after using drugs (State v. McKnight). Legal scholars argue that McKnight’s conviction prompted similar prosecutions of others whose only crime was having a SUD and being poor, Black, and pregnant [10]. This punitive approach to a public health issue is rooted in a history of systemic anti-Black gendered racism and perpetuates a cycle of incarceration and dehumanization against Black women and mothers.

The punitive approach to drug-related offenses, coupled with the separation of mothers from their children by the family policing system, raises important moral and ethical considerations. We use the term “family policing system” to refer to the governmental entity widely known as the child welfare system, which is engaged in family assessment, investigation, and intervention following referral for suspected child abuse or neglect. We amplify Dorothy Roberts’ interpretation, who argues that these systems are more engaged in family policing than family support [11].

Coerced or forced parent-child separation can have long-lasting traumatic effects on both mothers and children [12]. Additionally, research consistently demonstrates that Black families are disproportionately subjected to child removals and foster care placements when compared to White families [11, 13–15]. Parent-child separation can undermine Black women’s substance use recovery and perpetuate cycles of social and economic disadvantages, such as poverty and mass incarceration [13]. At the intersection of anti-Black gendered racism, reproduction, and parenting, one sees the vitriol towards Black reproduction and Black motherhood, particularly among Black pregnant and postpartum women experiencing SUDs, entrenched within and across three systems of oppression: healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems. Within this context, addressing the experiences of Black women is a microcosm of the broader structural and systemic injustices within the institutions that they must interface with.

Existing research on gendered racism has not examined the experience of Black mothers at the intersection of the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems. We, therefore, conducted a convergent mixed-methods study [16–18] to address this gap. The objective of this study was to describe experiences of anti-Black gendered racism and reproductive injustice among Black pregnant and postpartum women who use substances, have been incarcerated, and have been subjected to family policing systems. We aimed to document such experiences in order to contextualize their interactions with overlapping systems of surveillance and control that are known to have roots in intersecting forms of racism and sexism, which come to bear on their parenting and recovery experiences.

Central to our approach is the importance of centering the lived experiences of Black women with a SUD and acknowledging the multifaceted aspects of their identities. Therefore, the study’s overarching framework integrates Black feminist theory (BFT) and the reproductive justice (RJ) framework, which guided our research objectives. Both BFT and the RJ frameworks posit that Black women navigate a complex intersection of race, womanhood, and reproductive control, emphasizing its fluidity across contexts. They also identify and analyze oppressive systems that (re)produce anti-Black gendered racism, as well as preventive and mitigating solutions at the systemic and structural levels. A glossary of terms is provided in Table 1 to assist in understanding the overarching framework and relevant theories and concepts that informed this study.

Table 1.

Glossary of terms, abbreviations, and definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Black feminist theory (BFT) | An intersectional theory that centers Black women’s lived experiences both theoretically and methodologically. Patricia Hill Collins [1] locates BFT in four tenets – (1) Black women empower themselves by creating self-definitions and self-valuations that enable them to establish positive, multiple images and to repel negative, controlling representations of Black womanhood; (2) Black women confront and dismantle the “overarching” and “interlocking” structure of domination in terms of race, class, and gender oppression; (3) Black women intertwine intellectual thought and political activism; (4) Black women recognize a distinct cultural heritage that gives them the energy and skills to resist and transform daily discrimination. |

| Gendered racism | A type of gender and racial oppression that intersects to create a distinct type of subjugation experienced by women of color [3]. |

| Internalized racism | Acceptance by members of the stigmatized races of negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth [4]. |

| Interpersonal racism | Prejudice and discriminatory treatment from individual perpetrators on the basis of perceived racial differences regardless of intent [4]. |

| Obstetric racism | An occurrence and analytical tool that sits at the intersection of obstetric violence and medical racism. It facilitates mechanisms of subordination that create adverse medical experiences to which Black pregnant and postpartum people are subjected. Dána-Ain Davis [5] outlines the six dimensions of obstetric racism as beliefs and behaviors of any medical staff that demonstrates: (1) having critical lapses in diagnosis; (2) being neglectful, dismissive, or disrespectful; (3) intentionally causing pain; (4) perpetuating medical abuse; (5) coercing patients; and (6) staging ceremonies of degradation. Davis added three responses to obstetric racism: refusal, resistance, and racial reconnaissance. |

| Reproductive justice (RJ) | Was coined in 1994 by twelve Black women. It is a social movement and human rights framework that rests on centuries of Black feminism and Black women’s intellectual and radical organizing traditions. RJ focuses on more than legal rights related to abortion and contraception and connects bodily autonomy and reproduction to broader social justice issues, such as access to high quality affordable healthcare, housing, and education. As such, it is grounded in four main principles – (1) the right to have children; (2) the right not to have children; (3) the right to raise children in safety and with dignity; and (4) the right to bodily autonomy to disassociate sex from reproduction [6]. |

| Systemic and structural racism | Emphasizes the involvement of whole systems, and often all systems (e.g., political, legal, economic, healthcare, school, and criminal justice systems) in the (re)production of race-based oppression, including the structures that uphold these systems [7]. |

BFT accounts for how Black women interact with, confront, and dismantle systems of domination shaped by racism, sexism, and classism [4]. Importantly, BFT does not view these oppressive systems in isolation but asserts that they should be studied together because they intersect and influence each other. In our study, we incorporated Camara Jones’ [19] and Paula Braveman et al.’s [20] frameworks, which identify levels of systemic, structural, institutional, interpersonal, and internalized racism. These frameworks guided our interview guide development and analysis, particularly in exploring the interactions between Black pregnant women with a SUD and, family policing agents. Notably, structural racism and sexism can be characterized by “mother blame” narratives, attributing poor reproductive health outcomes solely to pregnant Black women while failing to acknowledge the upstream factors that reproduce inequities [21]. In addition to structural factors, we included frameworks to account for the coercive, traumatizing, and stigmatizing culture of incarceration, especially for Black pregnant women with a SUD [22]. To this end, BFT informed our analysis of the ways in which race, motherhood, and incarceration intersect and impact Black women’s experiences accessing maternal healthcare and treatment.

Similar to BFT, RJ centers on the experiences of structurally marginalized women whose reproductive rights have been violated, and who have experienced intersecting systems of oppression that reproduce adverse health outcomes [23, 24]. Our study used assessments of anti-Black gendered racism across the reproductive lifespan [25, 26], as well as dimensions of and responses to obstetric racism [27, 28], to capture Black participants’ discriminatory experiences while seeking substance use treatment and maternal healthcare. Dána-Ain Davis coined and defined obstetric racism as both an analytical tool and a phenomenon that sits at the intersection of medical racism and obstetric violence [27, 28]. Obstetric racism details how the US maternal healthcare system devalues, dehumanizes, and controls Black women and their babies in ways that perpetuate anti-Black racism and eugenics. When considering Black pregnant and postpartum women with a SUD, incarceration histories, and family policing system involvement, obstetric racism provides an additional nuanced understanding of the harms experienced by these women during the provision of any pregnancy-related event.

The integrated framework allowed us to holistically center Black women with a SUD and their experiences navigating the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems, including their narratives on the ways in which they confront and advocate against their own subjugation. In studying their narratives, we challenge existing racist and sexist stereotypes about the “unfit Black mother” who uses substances (e.g., the myth of the Black crack mother on government assistance and her crack babies); foster a deeper understanding of the complex intersections of incarceration, healthcare, motherhood, and different types and levels of oppression; and advocate for meaningful change within these systems. Our scholarship builds upon the work of Black feminist and reproductive justice scholars to hold these systems accountable and to uplift the health and well-being of Black women and mothers.

Methods

Overall Study Design

We conducted a convergent mixed-methods study in which we adapted and used a scale questionnaire while simultaneously conducting semi-structured interviews [16–18]. Study eligibility included pregnant and postpartum women who self-identified as Black and who (1) used illegal substances while pregnant, (2) were incarcerated in jail or prison while pregnant, and (3) had a history with family policing. We used the adapted scale questions to assess specific instances of discrimination across systems (healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing) pertaining to obstetric and systemic racism. We recruited individuals from one jail, three community mother-infant opioid treatment programs (OTPs), and two additional OTPs. Study sites spanned four states (Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, and Ohio), and people interviewed in the community could have been incarcerated at any jail or prison.

Research Team

Our core research team (DB, CK, CH, and CS) consisted of three Black cis-gendered women and one White cis-gendered woman. A fourth Black cis-gendered woman (KS) supported the research team as a subject matter expert in scale development, narrative analysis, and interpretation of results through the lens of obstetric racism and human rights violations. All study team members were trained in qualitative and quantitative research methods. Three team members, all Black women (DB, CK, and CH), conducted all study interviews. The study team had no prior relationship or contact with research participants.

We formed a community advisory board (CAB) of community members with lived experience of being pregnant with a SUD and having either criminal legal or family policing systems histories. All four members of the CAB self-identified as Black cis-gendered women. We met with the CAB three times during the 1-year study period to gain input on the overall study design, recruitment methods, interview guide content and terminology, findings, and data dissemination. Board members were compensated for their time and expertise.

Recruitment, Participants, and Study Procedures

We recruited study participants using convenience and snowball sampling methods. The study jail and mother-infant OTPs were recruited from a parent study focused on medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment experiences while being pregnant with OUD in jail (Sufrin et al., under review). We recruited community-based organizations through professional networks and internet searches to seek organizations that support and provide services to people with substance use, pregnancy, incarceration, and family policing experiences. We had no geographic restrictions for recruitment since all data was collected virtually.

To help facilitate study recruitment, we sent weekly emails to study site personnel at our partner jail and OTPs. The point of contact was someone involved in care or programming for pregnant women. If a newly admitted pregnant woman with substance use and/or criminal legal system history was admitted, we coordinated with the site point of contact to arrange a phone call to share more about the study and assess eligibility. Some participants at OTPs had their own cellular devices, and they called the study team directly to express interest. We used passive recruitment with the other community-based organizations by posting study flyers where members could see them. We also posted study flyers at the mother-infant OTPs. If someone was interested in participating in the study, they were instructed to contact the study team via phone or email.

Additional study eligibility criteria for all participants included being over 18 years old and English-speaking. For those recruited from jail, criteria also included being currently pregnant, using illegal substances while pregnant before arrest, and having a family policing history. For community participants who were either currently pregnant or not pregnant, their experience of being pregnant while incarcerated (jail or prison), using illegal drugs in pregnancy, and family policing involvement must have been within the last 10 years.

Once we identified someone interested and eligible to participate, we scheduled the interview at least 1 to 2 days later to allow people to fully consider their participation. We conducted all interviews remotely via Zoom or telephone. Participants who were in jail or at an OTP during the time of the interview were given a private space so no facility staff could overhear the conversation. Interviews lasted 90 min and were audio-recorded and transcribed for accuracy. Interviewers wrote post-interview memos to capture any non-verbal cues and initial impressions.

Interview Guide and Scale Development

Data collection methods included a scale questionnaire (quantitative data) and interview guide (qualitative data) using parallel constructs to determine the frequency, distribution, and contextualization of how racism and other forces of systemic and interpersonal discrimination affected the lived experiences, recovery, and parenting outcomes of Black pregnant and postpartum women with a SUD. We developed the interview guide to capture experiences of anti-Black gendered racism embodied by the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems, including how these systems surveil and impede treatment and parenting.

Study participants answered the scale questions (yes or no) during the interview. Interview questions were open-ended. The instrument and interview questions were organized by three systems: healthcare (OBGYNs, nurses, and SUD treatment staff), criminal legal, and family policing systems. We adapted the eleven scale questions from David Williams’ “Everyday Discrimination Scale” [29]. We added specific items on pregnancy and parenting informed by Davis’ [27, 28] dimensions of obstetric racism and Chambers et al.’s [26] and Treder et al.’s [25] structural racism across the reproductive lifespan. We referred to the adapted scale as the Reproductive Injustice Across Systems Scale (RIASS) and asked the scale questions across the three systems.

We opened the interview by first asking participants to share their overall perspectives of the criminal legal and family policing systems. We included questions across systems on whether they were mistreated or discriminated against based on their race or something else; how they thought systems’ workers viewed them; whether they felt they received the care and treatment they deserved; how their interactions with multiple systems impacted their healthcare, substance use treatment, and parenting; how they navigated these systems; and how they coped with these experiences.

Data Analysis

We used the integrated framework described in the “Introduction” to guide qualitative and quantitative data analyses. We developed the initial codebook using a priori domains from the interview guide. We then added inductive codes based on the content that emerged from the interviews. We (DB, CK, CS) independently coded most transcripts after first double-coding to assess agreeance in code application and conceptual understanding. During the coding process, we also referred to the post-interview memos to enhance the interpretation of codes and themes. Coders met regularly to address any uncertainties in code application. We identified key themes as they emerged within and between codes. We applied thematic data analysis based on interpretive phenomenology, which recognizes that people are inherently sense-making, especially regarding lived experiences that are complex, ambiguous, and emotionally taxing [30]. It uses historical, cultural, and social context, allowing researchers and participants to co-construct the phenomena.

For quantitative analysis of responses to the scale, we calculated the frequency and proportion of participants responding “yes” to each item per system. We then triangulated interview data with the RIASS scores by comparing participants’ scores in each system category with their narrative response for that system. For mixed-methods analysis, we conducted a side-by-side comparison of results from the RIASS and open-ended questions to determine areas of alignment and misalignment.

Ethical Considerations

The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved this study. We obtained additional research approval from all recruitment sites. We intentionally used a lag time between the recruitment call and the interview to avoid coercing participation. We compensated all participants with a $50 gift card. For those who were incarcerated at the time of the interview, we arranged to send study remuneration to a designated trusted individual in the community or to the individual after release. We intentionally asked all participants if they were in a space where they felt comfortable speaking freely before conducting the interview. We use pseudonyms in this manuscript to protect the identity of study participants.

Results

A total of 15 pregnant and postpartum women with a SUD (13 in the community, 2 in jail) participated in this study from July 2022 to March 2023. Table 2 provides details on demographics, pregnancy, and incarceration status. All participants self-identified as Black or Biracial, and the median age was 35 (range 22–55). Three participants were pregnant at the time of the interview. While most of the participants gave birth while living in the community, two gave birth in custody. The majority of participants, at the time of the interview, were currently living at a specialized substance use treatment facility for pregnant women or mothers and children.

Table 2.

Participant demographics and characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (N = 15) |

|---|---|

| Incarceration status at the time of the interview (n (%)) | |

| Incarcerated | 2 (13) |

| Not incarcerated | 13 (87) |

| State of residence at the time of the interview (n (%)) | |

| Kentucky | 6 (40) |

| Maryland | 7 (47) |

| Virginia | 2 (13) |

| Median age in years (minimum, maximum) | 35 (22, 55) |

| Pregnancy status at the time of the interview (n (%)) | |

| Pregnant | 3 (20) |

| Not pregnant | 12 (80) |

| Median gestational age at arrest in weeks (minimum, maximum)1 | 4 (4, 32) |

| Median duration of incarceration while pregnant in days (minimum, maximum) | 90 (2, 240) |

| Previously incarcerated (n (%)) | 14 (93) |

| Median number of times in jail or prison before this time (minimum, maximum) | 4 (0, 15) |

| Median number of times in jail or prison while pregnant (minimum, maximum) | 1 (1, 5) |

| Race ((n (%)) in each category) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13 (87) |

| Biracial (Black and white, non-Hispanic) | 2 (13) |

| Highest education level (n (%)) | |

| Primary school | 2 (13) |

| Some high school | 1 (7) |

| High school diploma/graduate equivalency degree | 7 (47) |

| Some college | 3 (20) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 (13) |

| Relationship status (n (%)) | |

| Single | 11 (73) |

| Married | 2 (3) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (13) |

| Housing status at the time of arrest while pregnant (n (%)) | |

| Stable housing (lived with family, on their own, or with partner) | 11 (73) |

| No stable housing | 4 (27) |

| Employment/source of income at the time of arrest while pregnant (n (%)) | |

| Employed | 7 (47) |

| Unemployed | 6 (40) |

| Sex work | 1 (7) |

| Drug trade | 1 (7) |

| Average number of children they have given birth to (minimum, maximum) | 3 (1, 7) |

| Been pregnant in jail/prison during a prior pregnancy (n (%)) | 5 (33) |

| Ever given birth in custody (n (%)) | 2 (13) |

| Desire to have more children in the future (n (%)) | |

| Want more children now | 2 (13) |

| Want more children, just not now | 4 (27) |

| Don’t want any more children | 6 (40) |

| I don’t know | 2 (13) |

| Other: didn’t want more, no longer menstruating | 1 (7) |

| Health insurance coverage when not incarcerated (n (%)) | |

| Medicaid | 14 (93) |

| Medicaid + Medicare (disability) | 1 (7) |

Missing data (n = 1)

The qualitative analysis revealed the powerful impact of multiple interactions with intersecting healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems on participants, many of whom described feeling traumatized by their experiences. They described grappling with the role these systems played in perpetuating reproductive injustices in their lives. Additionally, participants shared experiences of facing multiple stigmatizations, such as being a Black woman with a criminal record and a history of substance use while pregnant, which influenced their interactions with healthcare providers, carceral staff and family policing agents. While most recounted instances of interpersonal anti-Black gendered racism, a subset articulated how structural and systemic discrimination also shaped their experiences accessing healthcare and treatment. These encounters with mistreatment and, at times, dehumanization profoundly impacted their willingness to seek treatment and disclose their substance use to prenatal care providers, as well as their perceptions of these systems.

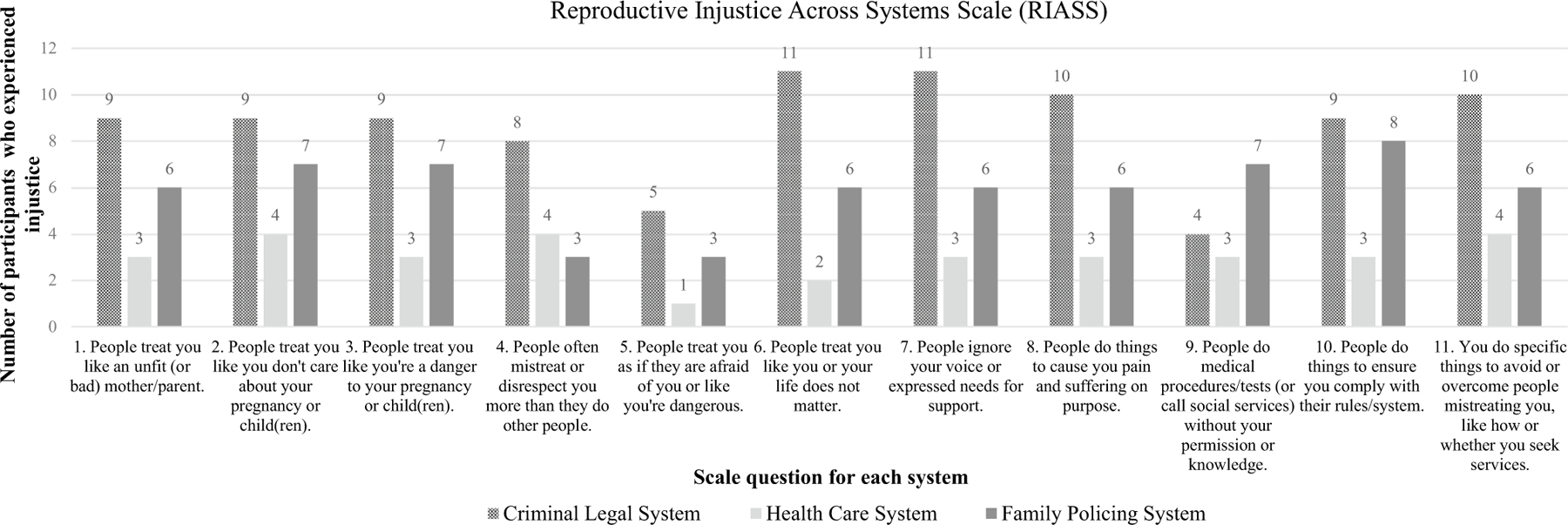

In Fig. 1, we present participants’ aggregated responses to the RIASS questions to support the qualitative findings. Individuals were more inclined to report experiencing mistreatment when interfacing with the criminal legal system compared to other systems. However, participants also voiced concerns regarding staff within the healthcare and family policing systems. For example, four participants stated that healthcare staff treat them like they do not care about their pregnancy or child(ren), while seven participants echoed similar statements about the family policing system.

Fig. 1.

Reproductive Injustice Across Systems Scale (RIASS) aggregate responses

Despite the healthcare system receiving the lowest scores, some participants offered detailed descriptions of their experiences of obstetric racism and anti-Black gendered racism while accessing prenatal healthcare and substance use treatment in community settings. These narratives underscore the nuanced nature of participants’ encounters within these systems. For a more comprehensive understanding, we delve into a detailed discussion of participants’ scale responses, examining how they align with each theme.

Four themes emerged from our analysis of interviews with Black pregnant and postpartum women about their experiences of anti-Black gendered racism while navigating the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems: (1) Uncertainty and imperceptibility when talking about structural and systemic anti-Black gendered racism and how it impacted their lives; (2) Convergence of the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems that perpetuated systemic anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism against Black women; (3) Dehumanization and stigmatization of the “bad and unfit” Black mother that reproduces obstetric racism and systemic anti-Black gendered racism; and (4) Internalized “mother blame” narratives particular to Black women who used drugs while pregnant and have criminal legal and family policing system histories.

(1). “I Never Had a Problem with Racism.”: Uncertainty and Imperceptibility When Talking About Structural and Systemic Anti‑Black Gendered Racism and How It Impacted Their Lives

Most participants described experiences of mistreatment while navigating the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems and attributed this mistreatment to both their substance use and incarceration status. Although many participants described instances of interpersonal discrimination, they expressed mixed beliefs and even uncertainty when recounting their experiences of systemic and structural racism. When asked how racism, specifically, impacted their lives, six participants plainly stated that racism had no impact. Ashley explained that for her, she “never really came across anybody who’s been racist towards me, not that I know of. And I…haven’t really had to deal with it.” Similarly, Keisha lived in a majority-Black city, which meant that she had limited contact with different racial groups.

I’m not used to being around a mixture of people. So, what is good for one is good for another, from where I’m from. So, I don’t really specifically deal with the race card like that…as far as racism, I’m not up on that.

In this excerpt, Keisha explained that her experiences are comparable to those of other Black people in her community. For Keisha, “If it’s Black people around that area, then it’s mainly Black people around that area,” making it difficult for her to decipher whether she experienced racism or not.

Other participants shared varying views about if and how interpersonal and systemic anti-Black gendered racism impacted their lives. Diamond was certain about her experiences with interpersonal discrimination while navigating the criminal legal and family policing systems. However, she was sometimes hesitant when describing her experiences navigating the healthcare system. When an interviewer asked if she ever felt discriminated against or mistreated by a healthcare provider, Diamond stated, “I did.” She talked through her experiences for a short while, paused for a second, then asked the interviewer, “And when you say discriminated, can you give me a definition of it? Because I want to make sure I’m using it the right way.” The interviewer answered, “Discriminated, as in treated differently than someone else who might be another race, or who might not be using drugs, or who might be another gender…” Diamond, with her voice drawing back, explained:

I feel as though that…I don’t want to talk bad about them [staff at the substance use treatment program]. Sometimes, I feel as though that, when I’m [at the substance use treatment program]…I have been labeled as a bully… And I feel as though…everybody who was called [a bully] was Black. I felt that was discrimination. Because I don’t feel as though only Black people are bullies.

Diamond clearly described experiencing anti-Black gendered racism at the substance use treatment facility. Yet, her insistence on not talking “bad” about her substance use treatment providers could signal her discomfort in talking about her experiences of interpersonal discrimination. It could have also been a response to systems of care that supported Diamond while in recovery and simultaneously harmed her by constructing racialized and gendered imagery that constructs some women as bullies over others.

The interconnectedness of substance use treatment programs and the family policing system raises the stakes for individuals like Diamond. Reunification with children, which is contingent on meeting certain standards outlined in a case plan, often hinges on assessments of a person’s fitness to parent and perceived behavior and progress at the treatment program. The responses to the RIASS questions supported this assumption as eight participants stated family policing agents do things to ensure participants comply with their rules/system, and six participants stated they do specific things to avoid or overcome family policing agents mistreating them, like how or whether they seek services. For Diamond and others in a similar position, the fear of losing custody of their children may compel them to comply with their substance use treatment providers, even if their providers harmed them through discriminatory and dismissive care.

Once Diamond was reassured about her experiences with discrimination while receiving treatment, she felt comfortable expressing herself. Diamond’s constant reflection on what discrimination is and if, how, and when it affected her life was commonly expressed among most participants. Yet, participants’ answers to our RIASS questions added to the complexity of their narrative responses and demonstrated divergence between the two sources of data. When asked if jail staff “treat you like you or your life does not matter,” “ignore your voice or expressed needs for support,” “do things to cause you pain and suffering on purpose,” and “you do specific things to avoid or overcome people mistreating you, like how or whether you seek services,” at least 10 participants replied “yes” to each question. The divergence may imply that most participants experienced discriminatory treatment but may have had a difficult time narrating these experiences when asked to give explicit examples of discrimination.

One additional driver of divergence in our comparative analysis was participants’ uncertainty about how structural and systemic anti-Black gendered racism appeared in their lives. Most respondents were certain and even comfortable discussing more explicit forms of discriminatory treatment, like interpersonal interactions, as was the case for Regina, a 37-year-old mother of three. Regina was even-toned during much of her interview. Her responses were quick, assertive, and definitive, particularly when discussing her experiences while incarcerated. Regina described how custody officers “treated [her] like an animal” by not responding to her needs. She also discussed how they called her and other incarcerated Black women “nigger,” regularly saying things like: “You monkeys don’t belong here.” or “All you’re doing is just inbreeding more monkeys.” Regina maintained that this was “typical racism shit.” Most participants’ examples of anti-Black gendered racism consisted of similar racist and sexist imagery, as well as receiving different treatment than their White female counterparts.

However, Regina stated she believed that the family policing system treated all people the same—“like someone who needs help.” When we asked additional questions, Regina described how the family policing system required her to undergo regular urine toxicology tests and supervised visits with her children, a routinized system of surveillance. Regina shared she must agree and comply with this surveillance, or she could lose certain privileges, like remaining at the substance use treatment facility or having regular contact with her children. Regina stated that she felt sad about her experience because it negatively impacted her ability to raise her children and be a part of their lives. This is a direct violation of a reproductive justice core tenet—the right to raise a family with dignity without fear or violence. In this example, Regina reported fair treatment from family policing agents because they helped all people equally. When questioned further, she gave personal examples of systemic anti-Black gendered racism through routinized surveillance.

Only one participant described anti-Black gendered racism as a structural and systemic phenomenon that shaped her experiences while incarcerated and pregnant. This suggests the ubiquitous nature of anti-Black gendered racism, making it difficult to name, understand, and explain the ways it affects Black women’s lives. Regina and other participants’ responses exemplified how being unable to identify the perpetrator of structural and systemic inequities obstructs individuals’ attempts to acknowledge when they are victims of it.

(2). “They Just Treat You Different All the Way Around.”: The Convergence of the Healthcare, Criminal Legal, and Family Policing Systems That Perpetuated Systemic Anti‑Black Gendered Racism and Obstetric Racism Against Black Women

Although participants reported being unaffected by racism, they described how multiple systems manifested interdependently to perpetuate systemic anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism. Accordingly, our data revealed several parallels between participants’ narrative accounts and their responses to the RIASS questions. For example, many participants described feeling judged and stigmatized by custody staff, which was supported by the RIASS findings. At least 10 respondents indicated experiencing discrimination from the criminal legal system, supporting their qualitative accounts. Conversely, fewer participants reported experiencing discrimination within the family policing system or while seeking healthcare, according to responses to the RIASS. Nevertheless, their narrative accounts detailed instances of anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism within and across these systems.

Almost all participants expressed a crippling fear of the family policing system that kept them from disclosing their substance use to healthcare providers and seeking prenatal care. Debra, for instance, described feeling discouraged from telling her prenatal care providers about her substance use. When reflecting on the questions her prenatal care providers asked during appointments, she explained, “[the questions] make me feel uncomfortable [because] they just treat you different all the way around.” Debra stated that she believed when prenatal care providers see that someone has a history of substance use, they sometimes ask about current substance use to get the care that they need, and other times ask to make a referral to the hospital social worker. Like Debra, many participants described delaying prenatal care because they assumed their prenatal care providers would report them to family policing agents. Notably, the relationship between the healthcare and family policing systems, as described by participants, caused many to worry about whether they would receive adequate care, as well as stress about their ability to parent their children without state intervention and surveillance.

This was true for Alexis, a 29-year-old mother of two. Alexis was referred to family policing by the hospital that supported her during the birth of her first baby after testing positive for cannabis. Alexis communicated that the hospital did not inform her that they tested her for substances. She discovered that the hospital notified family policing agents about her substance use from a letter in the mail accusing her of child neglect. When she received the letter, her newborn was in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), so she was still coming to visit her daughter at the same hospital that filed the complaint.

Alexis stated she was skeptical about why the hospital treated her that way. She shared that she was unsure whether the mistreatment was because of her race or other social identities. Nonetheless, Alexis explained that her negative experience, like others, deterred her from disclosing her substance use to healthcare professionals in the future. This reluctance largely stemmed from the fear of potential involvement with the family policing system.

Participants disclosed that their experiences of discrimination from healthcare providers occurred more often when they were in jail. Debra described how custody officers placed her in isolation while pregnant because of a physical encounter with a nurse who worked at the jail:

A White nurse made a stipulation that I had - she was running to a code, and she bumped into me. Well, she went to the [custody officers] and told them that I bumped into her. So, they put me in isolation, which I was in isolation when I went into labor. And I didn’t get bonding visits or nothing. And they believed everything she said. And I had to stay in there until they rolled back cameras and seen that they were wrong. So, yeah…Because she knew the truth. She knew that I didn’t run into her. She knew that she ran into me. And so why she would lie, I’m not sure.

Debra later articulated her perception that individuals in positions of authority exploited and discriminated against Black incarcerated individuals. Even as Debra advocated for herself, the conditions of incarceration meant she had no claims to the truth about who bumped into whom. Debra succinctly summed up this sentiment, stating, “No one’s going to believe this inmate, especially this Black inmate.”

Following her transfer to a hospital in a predominantly White town after going into labor, Debra described feeling uncomfortable with the hospital staff. She noted their insincere sympathy towards her situation and their apparent lack of engagement in her treatment and care. Debra’s perception of the hospital staff’s insincerity reflects feelings of neglect, dismissal, and disrespect—a dimension of obstetric racism. She highlighted the absence of empathy from her healthcare providers, which she believed affected the quality of care she received. The life-negating experiences recounted by both Debra and Alexis as they navigated various systems— healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing—underscore how these systems converge and create distinct challenges for Black women with a history of substance use.

(3). “Because I Was a Criminal and Drug Addict.”: The Dehumanization and Stigmatization of the “Bad and Unfit” Black Mother That Reproduces Obstetric Racism and Systemic Anti‑Black Gendered Racism

Participants described how their constant interactions with the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems took a psychological toll on them. While most participants stated that they expected custody and medical staff to judge them for their incarceration status and substance use while pregnant, they also said they hoped for person-centered care that acknowledged their humanity. Unfortunately, their experiences conveyed overt instances of substandard care and animalistic forms of dehumanization.

For example, many participants articulated how they were not treated with the dignity and care one would expect when pregnant, with four participants even likening their treatment to being treated like animals. When probed to give an example of how they were treated like an animal, participants referenced experiencing regular shackling while pregnant during transportation to court and hospital appointments, receiving minimal, if any, prenatal care, recreational activities, or even showers, and being provided with inadequate meals and sleeping arrangements. One mother detailed how custody officers forced her to “lay on the floor…for three days” while seven months pregnant. Such denials of basic human needs and being chained like animals constituted their dehumanization.

The likening of Black pregnant women to monkeys, as referenced earlier by Regina, is an example of explicitly blatant animalistic dehumanization. When asked to give additional examples of when she felt like she was being disrespected or treated like an animal while incarcerated, Regina recalled:

I can remember one time when I was having really, really bad cramps, and I asked could I be taken to the hospital just for precautions because my second daughter that I had, she was premature, so I was already at high risk of having premature children, and [the jail medical staff and custody officers] ignored it. They sent me back to my cell. Three days later I started bleeding, and that’s when they took me to the hospital where I miscarried.

In this example, Regina knew what medical care should have happened, but it was denied despite her established risk of preterm birth. Regina’s experience illustrated how multiple dimensions of obstetric racism can happen concurrently to incarcerated Black pregnant women with a history of substance use. When asked why she believed she was treated so inhumanely by jail staff, Regina responded, “Because I was a criminal and drug addict.”

Many participants described how community health care providers judged patients for their past and current substance use, which deterred them from seeking treatment in the future. We asked participants to describe their childbirth experience, including their interactions with the hospital staff. Jessica, a mother of three who experienced incarceration during one pregnancy, noted that her treatment while in the hospital “wasn’t a good experience because nurses and doctors frown upon mothers who use while pregnant.” In detailing her childbirth experience, Jessica stated:

My baby was in NICU for two days, and I didn’t know that I was allowed to go and see her. I didn’t know that [my older kids] were allowed to come and see her. I didn’t know a lot of stuff because they weren’t communicating. And when I asked, I was like, “So, does she whine a lot?” I’m like, I don’t know this because I never had a baby in NICU. So, I’m asking questions, and the nurses [said], “She hasn’t had not one withdrawal.” And I’m like, “But your nurse just got mad.” But, apparently, she didn’t have any withdrawals. But according to the NICU nurse, she did. So, it was like just being treated that way. It was awful.

Unfortunately, like many participants, Jessica discovered her positive drug test result when the family policing representative entered her room. This discovery was particularly distressing, considering seven participants stated experiencing instances where social services were contacted without their consent or knowledge—a finding supported by the responses in the RIASS. Although the representative connected Jessica to a mother-infant substance use treatment program, she stated feeling embarrassed and ashamed throughout her hospital stay due to the ongoing judgment from the hospital staff.

Many participants communicated that community healthcare providers and family policing agents judged their ability to parent and sustain effective parenting strategies because of their race, gender, and past substance use. The RIASS scale responses reflected this with seven participants who stated that family policing workers treated them like they did not care about and were a danger to their pregnancy or child(ren). Debra refuted this assumption, stating, “That’s the furthest thing from the truth.” The persistent judgment from these workers left Debra feeling powerless, a sentiment echoed by many participants, as she expressed, “They make the rules on when you can see [your children] and when you can’t see them.” Debra and Jessica’s experiences illustrated how responses to their race, gender, and past substance use subjected them to increased surveillance and policing by the healthcare and family policing systems.

Participants communicated a constant fear of family policing workers, driven by the foundational fear that these agents of the state would determine them unfit to parent and remove their children from their custody. For many, this fear materialized into a harsh reality. Diamond narrated how her family policing workers “could’ve been a little bit more supportive instead of just kept on just taking my children.” She reflected on how constant system involvement impacted her relationship with her children:

I have three [children] that I don’t get to see. I can only email them…They made it very hard, you know? It took trust away…It took the bonds away… the bonding that I had with my girls, they don’t trust me as their mother. I am not able to protect my children. Them being taken away and put in places with people I don’t know. I don’t know what’s going on with them. Just me not being able to…be a mom and show them that I am going to be there to protect them. You know, what a mother is supposed to be… It destroyed my family a lot…A lot of hurt and pain. Just a lot of stuff, like a lot of hatred.

Diamond’s narrative drew attention to the role of the family policing system in the destabilization and destruction of Black family units. Important to note, Diamond initially called a family policing agency herself because she needed help—“I wish that I never called CPS. Because I did not receive the help that I asked for.” While Diamond stated that she self-medicated with substances because of personal issues, the constant child removals exacerbated her stress and caused her to return to use, further constraining her ability to parent her children.

(4). “We Judge Ourselves or Say Bad Things to Ourselves.”: Internalized “Mother Blame” Narratives Particular to Black Women Who Used Drugs While Pregnant and Have Criminal Legal and Family Policing System Histories

Participants shared feelings of shame and internalized “mother blame” for both using drugs and being incarcerated while pregnant. “I feel like it’s hard,” said Yasmine, a Black mother of three. Yasmine shared, “There’s a lot of stereotypes about Black mothers…[and we] judge ourselves or say bad things to ourselves, so I think it just messes with our self-esteem a little bit.” Regina described similar thoughts: “When society say, you know, ‘Black women, Black pregnant women aren’t shit,’ sometimes I believe that, and that’s all just the negative part of my brain feeding into the negative.” Yasmine’s and Regina’s reflections illustrated shame and internalized mother blame for their decisions, including its effects on their self-esteem and perceptions of self.

Participants described how their internalized mother blame stemmed from external mother blame narratives touted by health care providers, custody staff, local police, and even judges. When asked how she was treated in court after testing positive for drugs while pregnant, Regina replied:

Like a typical Black person going up against a Caucasian judge. It was – it wasn’t, you know, offered drug treatment or second chance. It was straight, A, “You’re going to go to jail. You don’t care about your baby. If you would have cared about your baby, then you would have never been getting high.”

Regina was clear about why her judge responded to her substance use with punitive discipline rather than humane and just care, including optimal treatment and resources. Regina and many other participants narrated how they internalized these messages, sometimes described as tough love. They spoke extensively about their decision to do drugs, not to do drugs, comply with family policing agents’ demands, and stay out of trouble.

Ashley stated that she hated that the family policing system was involved in her life. She described how her thoughts about their involvement shifted from self-blame to holding the family policing system accountable. While she stated, “I was upset with myself that I was in that situation,” she also “[felt] like I didn’t necessarily do anything wrong with my child.” Ashley explained that she could “see both sides in it – where I was wrong and where I feel like I didn’t deserve [family policing system involvement] as well.” She eventually began to normalize the family policing system’s constant involvement in her life — “But I mean I’ve put myself in the situation to have to deal with them. So I just expect it at this point.” This fatalistic outlook became a normal response to continuous interactions with the criminal legal and family policing systems.

Similar to Ashley, other participants explained why they deserved the hyper-surveillance of the criminal legal and family policing systems. Their narratives included scripts of brokenness, describing themselves as needing fixing. Often, participants expected to be reunited with their children after vocalizing and internalizing the therapeutic language of self-blame and complying with their family policing agents’ and substance use treatment providers’ demands. To illustrate, Brittney, a 40-year-old mother of four, detailed her frustrations after completing her case plan and not being reunited with her children.

It’s just, I don’t know. When I was in active addiction, I looked a mess. You know what I’m saying? Who don’t look a mess active? [The judge who was assigned to my case] actually came to my job not too long ago. She didn’t recognize who I was. I had to tell her who I was. And I don’t blame it on her. I don’t blame it on nobody but myself for my actions. But then in the same sense, if someone straightens up and does what they’re supposed to…I bumped my head, I got up and straightened up, and I’ve been straight. So, I don’t understand the system at all.

Brittney detailed how complying with the demands of both the criminal legal and family policing systems failed to lead to family reunification. However, her insistence on attributing blame solely to herself reflected the linguistic scripts participants described learning while receiving substance use treatment. Therapeutic language of internalized mother blame suggested that Black mothers who have used drugs must take personal responsibility for their current circumstances while simultaneously dismissing that their actions may have been survival mechanisms against systemic violence. Consequently, internalized mother blame narratives caused Brittney and many other participants to question these systems because they did not often result in being reunited with their families.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to describe the experiences of anti-Black gendered racism and reproductive injustice among Black pregnant and postpartum women who use substances, have a history of incarceration, and are involved with family policing systems. Our purpose was to document these experiences to provide context for their interactions with intersecting systems of surveillance and control. These systems are entrenched in intersecting forms of racism and sexism, which significantly influence Black women’s parenting and recovery experiences [11, 13, 31–34]. To achieve this objective, we conducted a convergent mixed-methods study that sheds light on the multifaceted nature and impact of anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism, which shaped and compromised optimal recovery for Black mothers enmeshed in multiple punitive and surveilling systems.

The manner in which Black pregnant and postpartum women in this study framed their overlapping involvement in multiple oppressive systems (healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems) underscored the implicit and explicit ways that anti-Black gendered racism and obstetric racism permeated their experiences while navigating these systems. For example, Regina’s accounts of the custody officers’ racist and sexist remarks towards the Black pregnant women under their care exemplified longstanding interpersonal anti-Black gendered racism [35, 36]. Pregnant women with a SUD threaten US representations of ideal motherhood [37]. However, since participants’ gender is racialized, they are more likely to be blamed, stigmatized, and punished by these systems for their substance use while pregnant than White men, White women, and Black men [38]. Multiple studies show that the healthcare, criminal legal, and family policing systems have a historical pattern of perpetuating multiple forms of anti-Black gendered racism, and our participants’ experiences while navigating these systems supported this work [11, 26–28, 32, 36, 39–41].

Our study highlighted multiple convergences between quantitative and qualitative findings. The instances of divergence between data sources occurred when participants articulated an ongoing denial of experiencing structural and systemic racism. This divergence reflects the power relations and dynamics of anti-Black gendered racism in favor of interlocking systems of oppression. However, we interpreted participants’ denial as an important protective response to shield themselves from internalizing a victim’s identity from systems that brutalize and demoralize Black women as mothers. Furthermore, participants’ denial may also reflect an act of resistance against the researcher during data collection. Black women’s resistance to victimization, as informed by BFT, is a testament to their unwavering commitment to self-determination [42]. BFT allows space for Black women to acknowledge and resist internalizing oppressive images stemming from systems designed to dehumanize and devalue Black women [41]. For example, Black women who navigate multiple systems of oppression within various institutions often survive by empowering themselves to create their own definitions of self. This enables them to establish positive self-images while repelling negative and controlling representations of Black womanhood [42].

Likewise, BFT acknowledges that Black women, although not impervious to hurt, pain, and trauma, are part of a cultural heritage that gives them the energy and skills to be resilient and survive [4]. One could also argue that participants’ denial serves as a formidable shield, protecting their mental health against the insidious impact of multiple types, intensities, and durations of anti-Black gendered racism while simultaneously demanding societal change. After all, their consent to participate in this study is an act of resistance that shatters the silence, facilitating a reclaiming of their voices, their truths, and their autonomy. These interpretations of denial permit nuances in Black reproductive health and Black mothering discourse because it recognizes the role of oppression (i.e., gendered racism), resistance (i.e., protecting themselves and their families from anti-Black racism), and resilience (i.e., self-efficacy and self-empowerment) in Black women’s lives [43].

In trying to understand how anti-Black gendered racism impacted their lives, participants described the contradictions of systemic and structural oppression that is historically and firmly felt but is denied by both institutions and people. Epistemic injustice, characterized by the denial of marginalized communities to generate and be recognized as knowledge producers, encompasses testimonial and hermeneutical injustices, hindering Black women from naming the root causes of the structural and systematic violence perpetuated against them [44, 45]. Unfortunately, a consequence of living in a racist and sexist society where one may argue to have never encountered racism or sexism is that many survivors may internalize narratives of self-blame, attributing oppressive conditions solely to individual actors. Thus, participants in our study similarly responded to questions about their incarceration and substance use with mother blame narratives.

Mother blame has been demonstrated in qualitative research as a gendered and racialized process that attributes social problems to the behaviors of Black mothers [21]. State agents and institutional actors tend to privilege mother blame narratives in an effort to change behavior. Yet, changes to individual behaviors do not eliminate adverse maternal and infant health outcomes or the structural and systemic factors driving health inequities and injustices [46, 47]. Moreover, research suggests that therapeutic interventions that are hyper-focused on self-blame may also be deepening individuals’ feelings of shame, a risk factor for increased substance use [48]. Scholars note that prioritizing individual choice without considering structural issues perpetuates stigma, surveillance, and criminalization, all of which impacted participants’ recovery and parenting experiences [21].

Participants in our study outlined the cumulative effects of multiple system involvement on their experiences accessing prenatal care and substance use treatment. Notably, participants experienced obstetric racism and systemic anti-Black gendered racism within and across systems. However, they may have interpreted the impact of each system differently because of the conflict between the stated intentions of these systems and their actual impact on participants’ lives. Abolitionists argue that the conflict individuals feel is by design. As stated by Dorothy Roberts, “That conclusion would be obvious if the government hadn’t run such an effective propaganda campaign, convincing most Americans that the trauma it inflicts on children is a form of family policing, care, and protection” [11]. Some scholars argue that those in power do not benefit from fundamentally changing systems that serve their interests, reinforce White supremacy and oppressive structures, and enrich their political and financial reigns [11, 49, 50] Hence, they have convinced most of us to believe in a phantasm of reforms and failed promises.

Still, some women questioned the legitimacy of the family policing and criminal legal systems, including the authority of their substance use treatment and community prenatal care providers. It should be noted that not every participant provided a critique as incisive as Debra and Diamond. This may be in part because participants’ experiences and familiarity with these systems varied. For example, Ashley initially thought of her substance use treatment providers as supportive because they gave her the tools to remain sober as a new mother. After she returned to using, the substance use treatment center filed a child endangerment report against her causing her view of the center to change from favorable to extraneous oversight of her mothering.

To explain the role of healthcare providers in funneling pregnant women into the criminal legal and family policing systems, legal scholar Michele Goodwin argues that healthcare providers serve a key function in the arrests and prosecutions of pregnant women. According to Goodwin, their roles as “undercover informants and modern day ‘snitches’” create conflicts between their ethical duties to their patients and their law enforcement obligations [40]. Other works reveal how race, gender, and class determine if medical information (e.g., previous substance use or a lack of prenatal care) is even used to surveil and police patients [38, 51, 52]. McCabe [38] describes how health care workers mobilize the law to criminalize and drug test pregnant women. In her study, the health care providers used a process of discretionary suspicion to target Black mothers for criminal investigation. This phenomenon is supported by prior work that suggests that Black mothers are more likely to be tested for substance use and referred to family policing systems than White women [14, 15, 51]. Once Black women have family policing system involvement, they may be subjected to even more implicit and explicit biases and heightened surveillance.

The family policing system marginalization that participants experienced resembled their experiences with the criminal legal system. The denial of participants’ family reunification and their over-surveillance post-incarceration illustrated how anti-Black gendered racism does not happen in a vacuum but is grounded in socio-historical factors that continue to shape how state actors perceive Black mothering. For example, research shows that the family policing system forcibly removes Black children from their parents at much higher rates than their White counterparts, although Black children’s removal is disproportionate to their parents’ substance use [15, 51]. Furthermore, empirical data has demonstrated that Black parents are more likely than White parents to be suspected and reported for abuse even when controlling for the likelihood of abuse [53]. When compounded with incarceration, which prevents women from raising a family with dignity because they are confined, the odds stacked against Black women are pronounced [54]. Therefore, when placed within the context of Black women’s increased drug screening and child removal, the reach of the carceral state goes far beyond institutional confinement.

Black pregnant and postpartum women with a SUD who have criminal legal and family policing system involvement understand all too well that the decisions state officials make about their and their family’s lives often ignore their prevailing vulnerabilities to oppressive systems. Each participant shared stories about failed state interventions or lack thereof, spanning from their childhood to seeking healthcare, social services, and substance use treatment as adults. They provided detailed descriptions of the limitations of these systems, including examples of how these systems have harmed them. Many participants described how they would return to using substances because of the stress caused by the constant surveillance by the family policing system. Furthermore, our research on family policing agents’ perceptions of anti-Black racism on the parenting experiences of Black pregnant women with a SUD underscores how these state agents, some of whom identified as Black, acknowledge the intergenerational and compounding racialized harms perpetuated by involvement in the criminal legal and family policing systems. Yet, they struggled to reconcile the perceived benefits of family policing involvement with its known harms (Martinez et al. under review). This cyclic return to substance use and the institutional barriers institutional actors face when trying to enact social change demonstrate how limited these systems are at addressing the upstream factors, such as systemic racism and sexism, undergirding participants’ adverse health and parenting experiences [11, 13, 33, 36, 55].

Implications and Future Research

In centering the experiences of Black women, we highlight their knowledge and perspectives across multiple intersecting sites of oppression, which shaped their relationships to these interconnected institutions. However, this research comes with limitations. One is that we did not ask women to discuss if or how anti-Black gendered racism, specifically, impacted their lives. Many of our questions were single-issue focused and asked participants about their experiences with internalized, interpersonal, systemic, and structural racism. After reviewing participants’ responses and discussing the results with experts in the field, we realized that we could not separate participants’ gender from their race. To that end, we restructured our analysis to focus on anti-Black gendered racism to accurately assess participants’ experiences.

Another study limitation is that our RIASS questionnaire failed to distinguish between prenatal care and substance use treatment providers when asking questions about healthcare workers. Future research might distinguish healthcare systems to examine the nuances of Black women’s experiences while navigating these systems. A better understanding of these nuances can provide insight into how different healthcare systems aid or impede Black women’s parenting and recovery experiences. Furthermore, some participants were in jail custody during the study interview, but many others were in a community setting, sometimes an in-patient treatment facility. Their setting and the length of time from their incarceration for those who were not in custody should be considered a study limitation because it could impact their comfortability sharing their experiences and the salience of those experiences.

To better understand what Brittany Friedman and Brooklynn K. Hitchens [56] call the punishment continuum — the continuity of carcerality designed to precede, ensure, and outlast any single conviction into infinity — it is critical for analyses to prioritize Black women’s accounts of intersectional oppression across and within overlapping institutions. The use of parallel constructs during study design and data analysis facilitated our understanding of the deprived liberties the carceral state imposes on the lives of Black mothers who have a SUD and criminal legal and family policing systems histories. In addition, future research on Black women’s experiences must draw upon Black feminist and reproductive justice theories to examine the ways in which structurally marginalized Black women discuss interconnected institutions and their influence on their reproductive healthcare experiences, recovery, and parenting outcomes.

The first step to addressing their experiences of reproductive injustice during care delivery and treatment is to train clinical and custody staff on providing trauma-informed care and pregnancy-specific training on administering medications for different SUDs. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women [57] and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [58] established recommendations for reproductive healthcare and medications for substance use treatment for incarcerated pregnant and postpartum women. The carceral and healthcare systems must implement recommendations from medical experts to ensure quality healthcare for those confined.

Furthermore, participants were resolute in expressing their love and dedication to their children. They emphasized the importance for providers and custody staff to recognize that they were grappling with a disorder often accompanied by mental and physical health challenges. These system actors must be trained in human-centered language when addressing Black women with a SUD, including training on reducing stigma, mistreatment, and understanding that substance use is a medical disorder and not a personal failure. Birth equity scholars have proposed models of care, such as the cycle to respectful maternity care framework [59], which trains clinicians and other system actors involved in the care and treatment of Black pregnant and postpartum women on actionable steps towards providing anti-racist maternity care. This framework offers guidance on administering care at the internalized, interpersonal, and institutional levels, ensuring that dignity, privacy, and confidentiality are maintained and that care is free from harm and mistreatment [59].

Next, the trauma participants recounted experiencing while navigating both carceral and healthcare systems suggests that there needs to be radical policy changes that eliminate the criminalization of Black girls and women who use substances. This change is crucial to ensure that they are not subjected to increased surveillance, policing, confinement, and infringement upon their reproductive rights. Achieving radical change requires a disinvestment in systems of surveillance, punishment, and control, coupled with an increased investment in systems of care. Long-term policy strategies must focus on investing in care systems that sustain Black life, such as Black women and femme led birth centers and structural support systems that promote healing, health, and life-making.

Ultimately, this convergent mixed-methods study emphasizes the need for a reconfiguration of how society understands, treats, and illustrates Black motherhood. Black pregnant and postpartum women with a SUD must not be cast as criminals but rather as loving mothers struggling at the nexus of multiple systems designed to harm Black women and their children. Our goal is to advocate for a future without jails, prisons, and family policing systems so that all people can savor what it means to be treated as full humans. To this end, we must rectify the grave harms our institutions have committed against Black women and their families and imagine alternative processes and practices that support them while in recovery.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Community Advisory Board, which assisted with the interview guide, reflection on results, and the dissemination of results. We also want to thank our participants for their willingness to participate and share their life stories with us.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIDA K23DA045934–04S1).

Footnotes

We acknowledge that people of many gender identities have the capacity to become pregnant. However, we intentionally use the term “women” in this manuscript to focus on the unique experiences of cis-gendered Black women.

Declarations

Ethics Approval The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB00174954) granted ethical approval for this project.

Consent to Participate All participants provided informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for Publication All participants provided informed consent for their data to be published in a journal article.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Carson A (2022) Prisoners in 2021 - Statistical Tables. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng Z (2023) Jail inmates in 2022 – Statistical Tables. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewer RM. Black women and feminist sociology: the emerging perspective. Am Sociol 1989;20:57–70. 10.1007/BF02697787. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collins P Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Second edition. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crenshaw K Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist politics. Univ Chic Legal Forum 1989;1989:39–52. 10.4324/9780429499142-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkins AC. Becoming Black women: intimate stories and intersectional identities. Soc Psychol Q 2012;75:173–96. 10.1177/0190272512440106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Essed P Understanding Everyday Racism: an interdisciplinary theory. SAGE Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinton E From the war on poverty to the war on crime: the making of mass incarceration in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander M The New Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The New; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin M How the criminalization of pregnancy robs women of Reproductive Autonomy. Hastings Cent Rep 2017;47:S19–27. 10.1002/hast.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts DE. Torn apart: how the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families - and how Abolition can build a Safer World. New York City: Basic Books; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sankaran V, Church C, Mitchell M. A cure worse than the Disease: the impact of removal on children and their families. Marquette Law Rev 2019;102:1161–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts DE. Prison, foster care, and the systemic punishment of black mothers. UCLA Law Rev 2012;59:1474–500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts SCM, Zahnd E, Sufrin C, Armstrong MA. Does adopting a prenatal substance use protocol reduce racial disparities in CPS reporting related to maternal drug use? A California case study. J Perinatol 2015;35:146–50. 10.1038/jp.2014.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts SCM, Nuru-Jeter A. Universal alcohol/drug screening in prenatal care: a strategy for reducing racial disparities? Questioning the assumptions. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:1127–34. 10.1007/s10995-010-0720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design : qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles: Sage; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins D, Gioia D. Mixed methods research. New York City: Oxford University Press (OUP); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkins D Secondary data in mixed methods research. First edition. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones CP. Going public - levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1212–5. 10.3102/0002831211424313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braveman BPA, Arkin E, Proctor D, et al. Systemic and structural racism. Health Aff 2022;41:171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott KA, Britton L, McLemore MR. The Ethics of Perinatal Care for Black women: dismantling the structural racism in mother blame narratives. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2019;33:108–15. 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth R, Ainsworth SL. If they hand you a paper, you sign it: a call to end the sterilization of women in prison. Hastings Womens Law J 2015;26:7–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross L, Solinger R. Reproductive Justice: an introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross LJ, Roberts L, Derkas E, et al. Radical Reproductive Justice: foundations, theory, practice, and Critique. New York City: The Feminist Press at CUNY; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treder K, White KO, Woodhams E, et al. Racism and the Reproductive Health Experiences of U.S.-Born Black Women. Obstet Gynecol 2022;139:407–16. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chambers BD, Arega HA, Arabia SE, et al. Black women’s perspectives on structural racism across the Reproductive Lifespan: a conceptual Framework for Measurement Development. Matern Child Health J 2021;25:402–13. 10.1007/s10995-020-03074-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis DA. Reproducing while Black: the crisis of Black maternal health, obstetric racism and assisted reproductive technology. Reprod Biomed Soc Online. 2020;11:56–64. 10.1016/j.rbms.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]