Abstract

Introduction

High body mass index (BMI) is a risk‐factor for stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Mid‐urethral sling (MUS) surgery is an effective treatment of SUI. The aim of this study was to investigate if there is an association between BMI at time of MUS‐surgery and the long‐term outcome at 10 years.

Material and Methods

Women who went through MUS surgery in Sweden between 2006 and 2010 and had been registered in the Swedish National Quality Register of Gynecological Surgery were invited to participate in the 10‐year follow‐up. A questionnaire was sent out asking if they were currently suffering from SUI or not and their rated satisfaction, as well as current BMI. SUI at 10 years was correlated to BMI at the time of surgery. SUI at 1 year was assessed by the postoperative questionnaire sent out by the registry. The primary aim of the study was to investigate if there is an association between BMI at surgery and the long‐term outcome, subjective SUI at 10 years after MUS surgery. Our secondary aims were to assess whether BMI at surgery is associated with subjective SUI at 1‐year follow‐up and satisfaction at 10‐year follow‐up.

Results

The subjective cure rate after 10 years was reported by 2108 out of 2157 women. Higher BMI at the time of surgery turned out to be a risk factor for SUI at long‐term follow‐up. Women with BMI <25 reported subjective SUI in 30%, those with BMI 25—<30 in 40%, those with BMI 30—<35 in 47% and those with BMI ≥35 in 59% (p < 0.001). Furthermore, subjective SUI at 1 year was reported higher by women with BMI ≥30, than among women with BMI <30 (33% vs. 20%, p < 0.001). Satisfaction at 10‐year follow‐up was 82% among women with BMI <30 vs 63% if BMI ≥30 (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

We found that higher BMI at the time of MUS surgery is a risk factor for short‐ and long‐term failure compared to normal BMI.

Keywords: body mass index, long‐term effect, mid‐urethral sling, obesity, overweight, stress urinary incontinence

Treating stress urinary incontinence with a mid‐urethral sling seems to be more effective if you have a BMI <30 than if you are obese and have a BMI ≥30.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- Gynop

The Swedish National Quality register of Gynecological Surgery

- MUS

mid‐urethral sling

- SUI

stress urinary incontinence

Key message.

The long‐term result of mid‐urethral sling surgery due to stress urinary incontinence depends on your body mass index at surgery. In women with a higher body mass index, the expectation of consistent continence in 10 years is lower than in those with a normal body mass index.

1. INTRODUCTION

Being overweight or obese is a known risk factor for stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and negatively affects quality of life. 1 The proportion of the population suffering from obesity has increased dramatically in the past 30–40 years. Today, more than 40% of women in Sweden are overweight or obese. 2 The prevalence of obesity in the USA is even more alarming, where 41.9% of women have a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2, indicating obesity. 3

Overweight and obese women who have a higher intra‐abdominal pressure are at greater risk of SUI. 4 Chronically increased intra‐abdominal pressure is thought to have a negative effect on the pelvic floor muscles and nerves. However, the pathophysiology underlying obesity and urinary incontinence is not fully understood. 5 Weight loss, through lifestyle modifications or surgical intervention, has been shown to have a significant effect on SUI. 5

Studies on the impact of BMI on mid‐urethral sling (MUS) outcomes have been inconclusive and contradictory. 6 , 7 , 8 Furthermore, there is little knowledge of the long‐term effects of MUS surgery in obese women. 5

The primary aim of this study was to investigate whether there is an association between BMI at the time of MUS surgery and the long‐term subjective status of SUI. Secondary aims were to examine subjective SUI 1 year after surgery and evaluate treatment satisfaction at 10‐year follow‐up in relation to BMI at the time of surgery.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This retrospective cohort study comprises women who have had a primary MUS inserted between 2006 and 2010 in Sweden. They were registered in the Swedish National Quality Register of Gynecological Surgery (Gynop), established in 1997. All data entering the registry are collected prospectively. Patients are administered a preoperative questionnaire on general health and gynecological symptoms, and the surgeon subsequently reports the preoperative status, surgical data and any complications. Questionnaires are also sent to patients after 8 weeks and 1 year. During the study period, data coverage of the Gynop is unknown, but the rate was between 85 and 90% over the following 4 years. 9 Ten years after surgery we invited women registered in the Gynop to participate in a long‐term follow‐up. To assess lower urinary tract symptoms women were asked to complete an abbreviated version of the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI‐6). This validated questionnaire assesses urinary tract symptoms and their effect on quality of life (higher scores indicating greater disability). 10 The third question in the UDI‐6 was used to define our primary outcome (SUI at 10 years after surgery): “Do you experience urinary leakage during physical activity?” followed by the options “yes” or “no” and if so, how much are you bothered: “not at all,” “a little bit,” “moderately,” or “greatly.” No SUI was defined as “no” or “yes, but not bothered at all.” Hereafter, we will use the term “subjective SUI at 10 years.” Data were retrieved from the 10‐year follow‐up questionnaire.

The secondary outcome, SUI at 1 year, was defined by the question: “How often do you experience urinary leakage during physical activity, or when you laugh, cough or sneeze?” This question was followed by the options “never,” “1–4 times per month,” “1‐6 times per week,” “once a day,” and “more than once a day.” No SUI was defined as never or 1–4 times per month. For the secondary outcome we use the term “subjective SUI at one year.” Data were collected from the Gynop registry 1 year after surgery. Another secondary outcome was satisfaction 10 years after MUS surgery. This outcome was grouped into “very satisfied” or “satisfied” vs “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied.”

In accordance with the World Health Organization, 11 we classified BMI (in kg/m2) into four groups: group 1 BMI <25, group 2 BMI 25–<30, group 3 BMI 30–<35, and group 4 BMI ≥35. This study did not distinguish obesity class 3 (BMI 35–<40) from obesity class 4 (BMI ≥40). The distinction between non‐obese (BMI class 1 and 2, BMI <30) and obese women (BMI class 3 and 4, BMI ≥30) was taken into consideration 11 when analyzing the change in reported SUI from one to 10‐year follow‐up. Non‐obesity and obesity were also used when analyzing the secondary outcome “satisfaction.” The baseline BMI, which refers to the BMI measured at the time of surgery, was utilized in the analyses. When investigating the significance of the BMI change from surgery to the 10‐year follow‐up, we also used the BMI reported in the questionnaire administered at the 10‐year follow‐up.

Age at baseline was stratified into four categories: <50 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years, and ≥70 years. This stratification was done due to the nonlinear relationship between SUI and age, with a higher risk of incontinence post menopause.

Two previous publications from this cohort have appeared in the International Urogynecology Journal, presenting comprehensive details on the questionnaires and findings from the 1‐ and 10‐year follow‐ups. 12 , 13

2.1. Statistical analyses

Demographic data are presented as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The chi‐squared test was used to compare the difference in the primary categorical outcome. p‐levels <0.05 were considered significant. Logistic regression models were used to illustrate potential predictors of SUI. We adjusted for age, BMI (change in BMI from surgery to the time of the 10‐year follow‐up in regression analysis in Table 3), type of MUS sling inserted and preoperative incontinence (mixed urinary incontinence). Results of the logistic regressions are presented as crude (OR) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

TABLE 3.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for subjective SUI 10 years after MUS surgery based on the change in BMI from surgery to the 10‐year follow‐up (n = 2018).

| OR (95% CI) | aOR a (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI change from surgery to the 10‐year follow‐up | ||

| <30–<30, n = 1504 | Referent | Referent |

| <30–≥30, n = 164 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) |

| ≥30–<30, n = 105 | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) |

| ≥30–≥30, n = 245 | 2.3 (1.8–3.0) | 2.2 (1.6–2.9) |

Note: Data are OR (95% CI).

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Adjusted for age at surgery, type of MUS and type of preoperative incontinence.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.

3. RESULTS

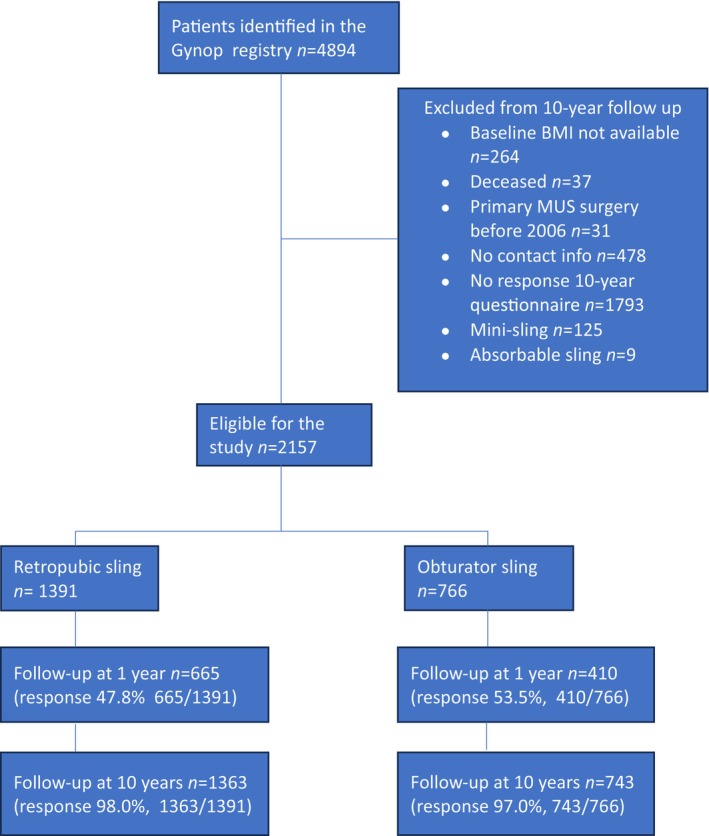

A total of 4894 women who had undergone MUS‐surgery in 2006–2010 were identified in the Gynop registry. The 10‐year follow‐up questionnaire was returned by 2555 (59%) women. We excluded individuals with missing information about BMI at baseline (n = 264), women who had received an absorbable sling or a mini‐sling (n = 134) and those who reported having had a first MUS inserted before 2006 (n = 31). In all, 2157 patients were eligible for analysis. The flowchart in Figure 1 depicts the number of women available for assessment at one‐ and 10 years post‐surgery.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of the study population (n = 2157).

Background data for women who meet the eligibility criteria (n = 2157) are given in Table 1. In the cohort, 139 (6.7%) women reported repeated MUS‐surgery (5.2% in the retropubic and 8.7% in the obturator group) after primary surgery and up to the 10‐year follow‐up. These women are included in the analyses.

TABLE 1.

Baseline data of the study population (n = 2157) divided according to BMI‐group.

| BMI <25, n = 995 (46) | BMI 25–≤30, n = 778 (36) | BMI 30–≤35, n = 292 (14) | BMI >35, n = 92 (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MUS surgery, mean (SD) | 51.7 (10.9) | 53.9 (10.7) | 56.5 (±10.7) | 55.9 (11.6) |

| Age at 10‐year follow‐up, mean (SD) | 63.1 (11.0) | 65.2 (10.8) | 67.8 (10.7) | 67.1 (11.4) |

| Years after MUS surgery, mean (SD) | 10.9 (0.8) | 10.8 (0.8) | 10.9 (0.8) | 10.8 (0.8) |

| Smoking at baseline, n (%) | 101/893 (10) | 78/713 (10) | 39/279 (13) | 9/88 (10) |

| Parity, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.5 (1.3) |

| ASA‐class, n (%) | ||||

| 1/2 | 964/974 (99) | 756/768 (98) | 283/286 (99) | 89/91 (98) |

| 3/4 | 10/974 (1) | 12/768 (2) | 3/286 (1) | 2/91 (2) |

| Obturator MUS, n (%) | 329/995 (33) | 288/778 (37) | 110/292 (38) | 39/92 (42) |

| Type of incontinence before surgery | ||||

| SUI, n (%) | 805/971 (83) | 559/761 (73) | 195/285 (68) | 51/91 (56) |

| MUI, n (%) | 162/971 (17) | 197/761 (26) | 89/285 (31) | 40/91 (44) |

| UUI, n (%) | 4/971 (0.4) | 5/761 (1) | 1/285 (0.3) | 0/91 (0) |

Note: Data are mean (± standard deviation) or n; number (%) of the BMI‐group.

Abbreviations: ASA, The American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status classification system; BMI, body mass index (kg/m2); MUI, mixed urinary incontinence; MUS mid‐urethral sling; SD, standard deviation; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UUI, urgency urinary incontinence.

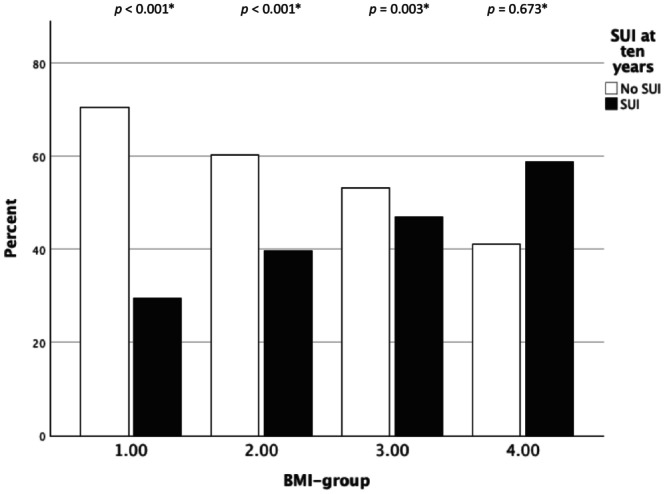

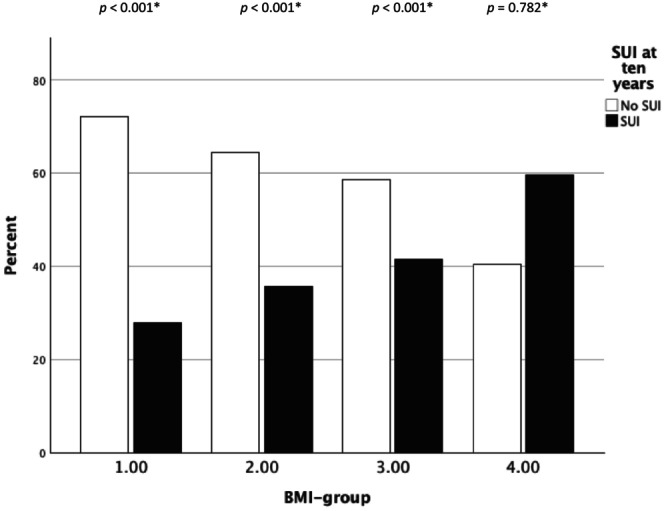

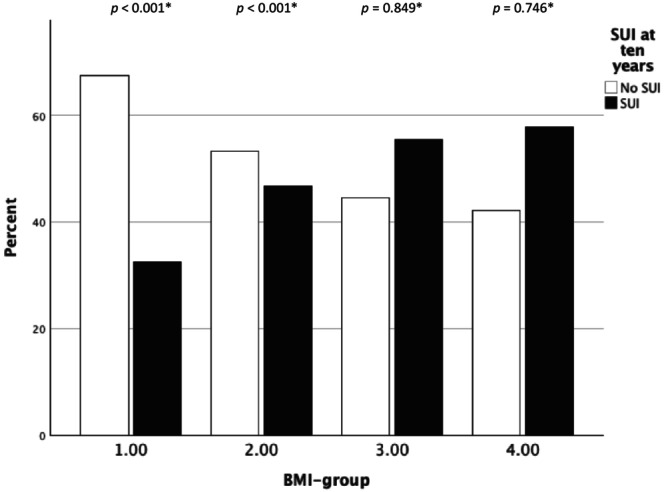

Subjective SUI at the 10‐year follow‐up differed significantly between BMI groups. Women with a BMI <25 reported subjective SUI in 30%, while those with a BMI 25–<30 reported it in 40%. For women with a BMI ranging from 30 to <35, the percentage rose to 47%, and for those with a BMI of ≥35, the prevalence reached 59% (p < 0.001). The primary outcome is also illustrated in Figures 2, 3, 4. Subjective SUI differed overall between the four BMI‐groups, both in total, as well as when divided into retropubic and obturator insertion groups. We found that the higher the BMI at the time of surgery, the higher the risk of subjective SUI at the 10‐year follow‐up.

FIGURE 2.

Subjective stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at the 10‐year follow‐up by BMI‐group. Data based on retropubic and obturator mid‐urethral sling mid‐urethral sling procedures. *Chi‐squared test within each BMI‐group.

FIGURE 3.

Subjective stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at the 10‐year follow‐up by BMI‐group – retropubic mid‐urethral sling. *Chi‐squared test within each BMI‐group.

FIGURE 4.

Subjective stress urinary incontinence (SUI) at follow‐up at the 10‐year follow‐up by BMI‐group – obturator mid‐urethral sling. *Chi‐squared test within each BMI‐group.

A binary logistic model was used to explore the meaning of BMI for MUS‐surgery (Table 2). The probability of subjective cure decreased with a higher BMI. In a multi‐variable regression analysis that adjusted for age, MUS technique and preoperative incontinence the aOR for SUI at the 10‐year follow‐up was 1.5 (1.2–1.9) for women with a BMI of 25–<30, 1.9 (1.5–2.6) for those with a BMI of 30–<35 and 3.0 (1.9–4.7) for those with a BMI of ≥35 compared to women with a BMI <25. Moreover, women who were older at surgery, women with MUI and women who received an obturator MUS were at higher risk of SUI at the 10‐year follow‐up (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Crude and adjusted odds ratios for subjective SUI more than 10 years after MUS surgery by age, BMI‐group at surgery, type of MUS and preoperative incontinence (n = 2108).

| OR (95% CI) | aOR a (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery (years) | ||

| <50, n = 871 | Referent | Referent |

| 50–59, n = 583 | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| 60–69, n = 494 | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) |

| >70, n = 160 | 2.4 (1.7–3.4) | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) |

| BMI at surgery | ||

| <25, n = 978 | Referent | Referent |

| 25–<30, n = 754 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) |

| 30–<35, n = 286 | 2.1 (1.6–2.8) | 1.9 (1.5–2.6) |

| ≥35, n = 90 | 3.4 (2.2–5.3) | 3.0 (1.9–4.7) |

| MUS | ||

| Retropubic MUS, n = 1363 | Referent | Referent |

| Obturator MUS, n = 745 | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| Type of incontinence prior surgery | ||

| SUI, n = 1575 | Referent | Referent |

| MUI, n = 475 | 1.8 (1.5–2.3) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) |

| UUI, n = 10 | 3.0 (0.9–10.9) | 3.0 (0.8–11.2) |

Note: Data are OR (95% CI).

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; MUI, mixed urinary incontinence; MUS, mid‐urethral sling; n, number; OR, odds ratio; SUI, stress urinary incontinence; UUI, urgency urinary incontinence.

Adjusted for age at surgery, type of MUS and type of preoperative incontinence.

Table 3 describes the significance of BMI‐change from surgery to the 10‐year follow‐up. The risk of SUI increases when BMI is ≥30 during surgery and remains so during the 10‐year follow‐up. The mean BMI for the study population changed from 26.3 kg/m2 (SD 4.4 kg/m2) at surgery to 26.7 kg/m2 (SD 4.6 kg/m2) at the 10‐year follow‐up.

Comparing treatment satisfaction 10 years after MUS surgery, 82% in the BMI groups 1 and 2 (BMI <30) reported being very satisfied or satisfied compared to 63% in groups 3 and 4 (BMI ≥30) (p < 0.001).

We also analyzed the 1075 women who responded both at the 1‐ and 10‐year follow‐ups, comparing the difference in postoperative outcome in obese (n = 232) and non‐obese (n = 842) women over time. One year post‐surgery, a higher percentage (33%) of obese women reported SUI compared to non‐obese women (20%) (p ≤ 0.001). At the 10‐year follow‐up, 56% of the obese women reported SUI and 42% of the non‐obese (p < 0.001).

To further analyze changes within the groups, we found that 29% of obese women reported no SUI at the 1 year follow‐up but did report de novo SUI at the 10‐year follow‐up. By comparison, 6% of the obese women reported SUI at 1‐year follow‐up but reported being cured at the 10‐year follow‐up (p < 0.001). Of the non‐obese women 28% were continent at 1 year after surgery but reported de novo SUI at the10‐year follow‐up, whereas 5% reported SUI at the 1‐year follow‐up but not at the 10‐year follow‐up (p < 0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

This nationwide registry study shows that obese women, compared to non‐obese women, report a worse subjective outcome 10 years after MUS surgery. Thus, obesity is a risk‐factor for failure, at the 1‐ and 10‐year follow‐ups. However, the difference in continence outcomes between obese and non‐obese women did not escalate 10 years after surgery. In both obese and non‐obese women, continence seems to decrease similarly over time. Self‐reported satisfaction with treatment after 10 years was higher in non‐obese compared to obese women.

Older age is a known risk factor for MUS failure. In a study by Gyhagen et al., 14 older age was associated with a lower cure rate 1 year after surgery. This finding is in agreement with our data, showing that women ≥60 years of age have an increased risk of SUI after MUS surgery, compared to women <60. In a previous study, we showed that retropubic slings demonstrated greater efficiency than obturator slings. This result holds, also when adjusting for BMI. Likewise, preoperative MUI is a predictor for SUI at long‐term follow‐up. 12

Several studies have investigated the relationship between BMI and SUI. The recent study by Solhaug et al. contributes important information about the relationship between obesity and a reduced subjective and objective cure rate of SUI after tension‐free vaginal tape surgery, during follow‐ups spanning up to 20 years. 15 A 2011 study evaluated the long‐term outcomes of women who underwent a MUS procedure and noted that 57% (81/141) reported being subjectively cured. The cure rate was reported to be 61% (59/97) in women with BMI <30 and 50% (22/44) in women with a BMI ≥30. 16 In a Swedish study 760 women who had previously undergone MUS insertion were followed for an average of 5.7 years. The findings revealed that 81.2% of women with a BMI <35 reported being cured from SUI, in contrast to 52.1% of women with BMI ≥35. 17 A 2013 review article challenges the findings of the studies described above. 18 Of 14 studies assessed only three showed a statistically significant difference in cure rate after MUS surgery between obese and non‐obese. The authors concluded that regardless of BMI, women have comparable cure rates after MUS surgery. However, many of these 14 studies had limited sample sizes, resulting in low statistical power.

Hence, previous research is inconsistent, as some studies have suggested that the effectiveness of the MUS does not differ between obese and non‐obese women. 7 , 8 , 18 In contrast, other reports have indicated that obesity is a predictor of poor outcomes. 15 , 16 , 17 In a randomized controlled trial of 176 females, obese women reported more SUI than non‐obese women at a 5‐year follow‐up. 6

The major strengths of our study are the large sample size and the long‐term follow‐up. In addition, the high‐quality and nationwide registry of the Gynop ensures a high level of generalizability. However, it should be noted that the inclusion rate of 59% at the 10‐year follow‐up could be seen as a potential limitation. Nevertheless, this rate is consistent with the typical expectation for long‐term follow‐ups. Another limitation is the absence of an objective measure of the primary outcome (SUI 10 years after surgery). Still, self‐reports after urinary incontinence surgery have been shown to align well with objective measure of surgical success. 19 A possible weakness is the use of different questions to assess subjective SUI at the 1‐ and 10 year‐follow‐ups, potentially impacting the results and their interpretation. Despite this, our results align with other relevant studies, suggesting that this limitation is negligible. We also believe that including women with both retropubic and obturator slings and comparing the two techniques is a strength and a significant contribution to evidence‐based facts relative to MUS‐surgery.

When interpreting and explaining our findings, we believe that increased abdominal pressure in obese women could be an additional stress on the pelvic floor to the extent that it challenges the effect of MUS‐surgery. Another speculation is that an increased amount of adipose tissue in the surgical area could diminish the stabilizing effect of the MUS.

Our study is relevant in guiding obese women, to make a well‐informed decision on whether to undergo MUS‐surgery. Trying to lose weight is a challenge for most people and exercise when suffering from urinary leakage is problematic. In accordance with the study of older women and MUS‐surgery, many women may accept some, but less bothersome incontinence. 14 Our study does not reveal to what extent obese patients regret their surgery, or their tolerance for a certain leakage. This issue warrants further investigation. Important to consider when guiding women regarding treatment options are peri‐ and postoperative complications. Several studies have suggested that complications of MUS‐surgery are not more prevalent in obese women. 20 , 21 However, the limited size of these studies makes it difficult to draw conclusions and generalize the results. More and larger studies are needed to clarify these important issues.

5. CONCLUSION

Obese women experience a lower cure rate after MUS surgery than non‐obese women in the short‐ and long‐term. However, the proportional increase of women with SUI from 1 to 10 years post‐surgery does not differ between obese and non‐obese women. Satisfaction 10 years after primary surgery is reported to be higher in non‐obese than in obese women.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anna Lundmark Drca, Marie Westergren Söderberg and Marion Ek made substantial contributions to the design and development of the project, the data analysis, the interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Open access funding provided by Karolinska Institutet. This study was funded by grants from Stockholm's Health Care Region (FoU).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved on May 8, 2019 by the Ethical Review Board at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm (reference number 2019‐02529). The study participants' informed consent were considered fulfilled if the questionnaires were returned.

Lundmark Drca A, Westergren Söderberg M, Ek M. Obesity as an independent risk factor for poor long‐term outcome after mid‐urethral sling surgery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103:1657‐1663. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14883

REFERENCES

- 1. Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Daltveit AK, Hunskaar S. Are smoking and other lifestyle factors associated with female urinary incontinence? The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. BJOG. 2003;110:247‐254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Statistik om övervikt och fetma hos vuxna. Accessed January 2024. www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se2023.

- 3. State of Obesity 2023: Better Policies for Healthier America – TFAH. Trust for America's Health. Accessed January 2024. https://www.tfah.org.

- 4. Doumouchtsis SK, Loganathan J, Pergialiotis V. The role of obesity on urinary incontinence and anal incontinence in women: a review. BJOG. 2022;129:162‐170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fuselier A, Hanberry J, Margaret Lovin J, Gomelsky A. Obesity and stress urinary incontinence: impact on pathophysiology and treatment. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brennand EA, Tang S, Birch C, Murphy M, Ross S, Robert M. Five years after midurethral sling surgery for stress incontinence: obesity continues to have an impact on outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28:621‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Majkusiak W, Pomian A, Horosz E, et al. Demographic risk factors for mid‐urethral sling failure. Do they really matter? PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pereira I, Valentim‐Lourenço A, Castro C, Martins I, Henriques A, Ribeirinho AL. Incontinence surgery in obese women: comparative analysis of short‐ and long‐term outcomes with a transobturator sling. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:247‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bennet Bark A . Täckningsgrader (Coverage rates). 2016: 17–23 pp.

- 10. Franzén K, Johansson JE, Karlsson J, Nilsson K. Validation of the Swedish version of the incontinence impact questionnaire and the urogenital distress inventory. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:555‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. A healthy lifestyle – WHO recommendations. 2010. Accessed January 2024. www.who.int.

- 12. Alexandridis V, Lundmark Drca A, Ek M, Westergren Söderberg M, Andrada Hamer M, Teleman P. Retropubic slings are more efficient than transobturator at 10‐year follow‐up: a Swedish register‐based study. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34:1307‐1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lundmark Drca A, Alexandridis V, Andrada Hamer M, Teleman P, Söderberg MW, Ek M. Dyspareunia and pelvic pain: comparison of mid‐urethral sling methods 10 years after insertion. Int Urogynecol J. 2024;35:43‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gyhagen J, Åkervall S, Larsudd‐Kåverud J, et al. The influence of age and health status for outcomes after mid‐urethral sling surgery‐a nationwide register study. Int Urogynecol J. 2023;34:939‐947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Solhaug BR, Nyhus M, Svenningsen R, Volløyhaug I. Rates of subjective and objective cure, satisfaction, and pain 10‐20 years after tension‐free vaginal tape (TVT) surgery: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG. 2024;131:1146‐1153. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aigmueller T, Trutnovsky G, Tamussino K, et al. Ten‐year follow‐up after the tension‐free vaginal tape procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:496.e1‐496.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hellberg D, Holmgren C, Lanner L, Nilsson S. The very obese woman and the very old woman: tension‐free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:423‐429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Osborn DJ, Strain M, Gomelsky A, Rothschild J, Dmochowski R. Obesity and female stress urinary incontinence. Urology. 2013;82:759‐763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kulseng‐Hanssen S. The development of a national database of the results of surgery for urinary incontinence in women. BJOG. 2003;110:975‐982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weltz V, Guldberg R, Lose G. Efficacy and perioperative safety of synthetic mid‐urethral slings in obese women with stress urinary incontinence. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:641‐648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rotchild M, Shelef G, Sade S, Shoham‐Vardi I, Weintraub AY. Obesity is not an independent risk factor for peri‐ and post‐operative complications following mid‐urethral sling (MUS) surgeries for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:1119‐1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]