Abstract

Objectives

Fructosamine correlates well with glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in Caucasians. This study investigates this correlation and whether fructosamine can reliably estimate glycated haemoglobin in Southeast Asians.

Methods

We recruited 193 participants based on 4 HbA1c bands (<6.0%; 6.0 – 7.9%; 8.0– 9.9%; ≥10%) from a secondary hospital in Singapore between August 2017 and December 2021. Blood samples for fructosamine, glycated haemoglobin, albumin, haemoglobin, thyroid stimulating hormone and creatinine were drawn in a single setting for all participants. Scatter plot was used to explore correlation between fructosamine and glycated haemoglobin. Strength of linear correlation was reported using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Simple linear regression was used to examine the relationship between fructosamine and glycated haemoglobin.

Results

We performed simple linear regression to study the relationship between fructosamine and HbA1c in the research participants (R2 = 0.756, p<0.01). Further analysis with natural logarithmic transformation of fructosamine demonstrated a stronger correlation between HbA1c and fructosamine (R2 = 0.792, p<0.01).

Conclusions

Fructosamine is reliably correlated with HbA1c for the monitoring of glycaemic control in Southeast Asians.

Keywords: fructosamine, glycated haemoglobin, Southeast Asian population, diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Hyperglycaemia promotes non-enzymatic glycation of proteins through the Maillard reaction with Schiff base formation through Amadori rearrangements.1 Glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is formed when the N-terminal valine residue of the beta chain is glycated.2 The half-life of HbA1c is 4 weeks3 and it reflects average blood glucose over the past 1 to 4 months. It was estimated that 50% of HbA1c reflects blood glucose in the past 1 month, 25% for the past 1 to 2 months, and 25% for the past 2 to 4 months.4 Hence, HbA1c does not accurately reflect blood glucose in the immediate period before blood sampling. The correlation between HbA1c and blood glucose is further eroded in the setting of pregnancy, advanced kidney disease, and conditions altering erythrocyte life expectancy, such as haemoglobin variants, haemoglobinopathies, and iron deficiency.5–9

Glycation of plasma proteins form ketoamines. These are collectively known as fructosamine because of the 1-amino-1-deoxy-D-fructose groups that are present in the glycated protein molecules. The half-life of fructosamine is 2.5 weeks10,11 and it reflects blood glucose in the preceding 2 to 4 weeks.12 Thus, fructosamine provides better reflection of blood glucose in the shorter term compared to HbA1c. Fructosamine had similar diagnostic performance as fasting glucose in detecting diabetes in a North American population.13 Fructosamine was also found to predict microvascular complications of diabetes.14–16 It is reportedly more suitable in monitoring blood glucose17 and predicted stillbirths in pregnant women with diabetes.18 One benefit of using fructosamine as a marker of glycaemic control is that it is not affected by erythrocyte lifespan or haemoglobin structure12 as compared to HbA1c. This is of particular importance in Southeast Asia where iron deficiency and haemoglobin variants are highly prevalent. Southeast Asia was ranked as the region with the highest prevalence for iron deficiency anaemia in 2010.19 The prevalence of iron deficiency in Malaysian school children was reported to be between 4.4% and 5.2%20,21 while up to 74% of Singaporean women in the third trimester of pregnancy were iron deficient in a cross-sectional study.22 Southeast Asia was reported in 2010 as one of the regions with the highest prevalence of thalassaemias.19 Between 4.5% and 22.6% of Malaysians were estimated to carry the gene for alpha thalassaemia.23 Between 1 and 9% of Southeast Asians carry the beta thalassaemia gene and between 1 and 8% carry the gene for Haemoglobin Constant Spring.24 Fructosamine was found to correlate well with HbA1c in studies conducted in North America,15 Sweden,25 Spain,26 Korea27 and the United Kingdom,3 involving participants with and without diabetes. Considering that fructosamine correlates well with HbA1c under normal circumstances and that erythrocyte abnormalities are highly prevalent in Southeast Asia, it can potentially be used as an alternative to HbA1c to monitor glycaemic status in patients with erythrocyte disorders. Thus, we aimed to find out if this correlation exists in a Southeast Asian population and whether fructosamine can reliably estimate HbA1c.

METHODOLOGY

Recruitment

This is a cross-sectional study. Patients were recruited from the Diabetes outpatient clinic, and the Health and Wellness clinic of Ng Teng Fong General Hospital between August 2017 and December 2021 based on 4 HbA1c bands: <6.0%; 6.0–7.9%; 8.0–9.9%; ≥10%. The sampling design is by purposive sampling through the recruitment of patients in the clinic, to ensure all ranges of HbA1c are represented equally.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria include all the following: people without diabetes based on medical history or physical examination record, patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, age between 21 and 99 years, of Chinese, Indian, or Malay ethnicity and who are able to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria include any of the following: pregnant women, patients with erythrocyte disorders (defined as mean corpuscular volume above or below the normal limits), anaemia (defined as haemoglobin below the lower limit of normal), protein-losing disorders, thyroid disorders, estimated glomerular filtration rate below 60 mL/min, on erythropoietin therapy or who have received blood transfusion within the preceding three months of recruitment.

Analytical methods

The following were measured based on either fasting or random serum samples from each participant during a single visit in a seated position: HbA1c, fructosamine, albumin, creatinine, full blood count and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH).

Samples for HbA1c were collected in ethylenediamine-tetraacetic acid tubes and measured using an enzymatic assay (Abbott Architect c8000, interassay coefficient of variation (CV) ≤2% when HbA1c is between 5.7% (39 mmol/mol) and 7.0% (53 mmol/mol), ≤3.5% when HbA1c >7.0% (53 mmol/mol). This method is standardised to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial assay. Samples for fructosamine were collected in plain tubes and measured using spectrophotometry (Roche Cobas c502, total imprecision when fructosamine < 285 umol/L is ≤9 umol/L, CV ≤3% when fructosamine >285 umol/L). Samples for albumin were collected in serum separator tubes and measured using the photometric method based on binding with bromcresol green (Abbott Architect c16000, CV ≤3.3%). Samples for creatinine were collected in serum separator tubes and measured using the enzymatic method (Abbott Architect c16000, CV ≤3.6%). Samples for haemoglobin were collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes. Samples for TSH were collected in serum separator tubes and measured using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (Abbott Architect i2000SR, CV ≤10%).

The laboratory results were recorded and secured in the hospital's electronic medical record system.

Sample size calculation

The sample size of 203 was calculated based on 80% statistical power and 5% Type I error rate. We assumed a modest positive linear correlation of 0.5 between HbA1c and fructosamine for each of the three ethnic groups (Chinese, Malay, and Indian) and 4 pre-defined HbA1c bands.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 28 was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics was used to summarise the demographics of participants. Scatter plot was used to explore the relationship between fructosamine and HbA1c. Strength of linear correlation was reported using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A stronger correlation between nature log transformed fructosamine and HbA1c than the untransformed fructosamine was observed and it indicated that HbA1c might be linearly associated with log-transformed fructosamine. Simple linear regression model was used to evaluate the linear relationship between nature log transformed fructosamine and HbA1c in the research participants. Assumptions of linear regression model were checked by the residual plots to ensure the model's validity. R2 was reported to evaluate the fitness of the model. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical concerns

The study was approved by the Domain Specific Review Board of the National Healthcare Group (Singapore). Signed informed consent was obtained from all research participants. All study data were de-identified.

RESULTS

Characteristics of research participants

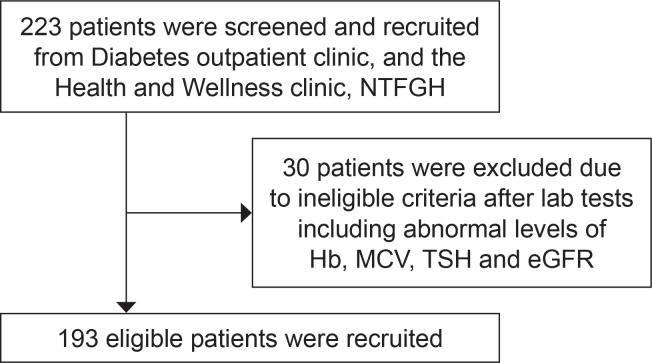

One hundred and ninety-three research participants were recruited and analysed (Figure 1). Recruitment stopped at 193 participants after analysis demonstrated R2 = 0.792. The characteristics of research participants with regards to gender, ethnicity, age and biochemical parameters are summarised in Table 1. Based on 4 HbA1c bands: <6.0%; 6.0 – 7.9%; 8.0 – 9.9%; ≥10%; there were 50 (25.9%), 50 (25.9%), 47 (24.4%) and 46 (23.8%) participants recruited in the respective categories.

Figure 1.

Overall recruitment flow.

Table 1.

Characteristics of research participants

| Characteristic | All |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 86 (44.6%) |

| Male, n (%) | 107 (55.4%) |

| Age (years, mean, SD) | 53.7, 12.7 Range: 22-76 |

| Chinese, n (%) | 125 (64.8%) |

| Indian, n (%) | 42 (21.8%) |

| Malay, n (%) | 26 (13.5%) |

| Hb (g/dL, mean, SD) | 14.3, 1.4 |

| MCV (fL, mean, SD) | 86.0, 3.5 |

| Albumin (g/L, mean, SD) | 42.7, 2.5 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min, mean, SD) | 98.1, 13.2 |

| HbA1c (%, mean, SD) | 8.0, 2.2 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol, mean, SD) | 64, 24 |

| Fructosamine (umol/L, mean, SD) | 325.9, 83.4 |

n: number; SD: standard deviation

Relationship between fructosamine and HbA1c

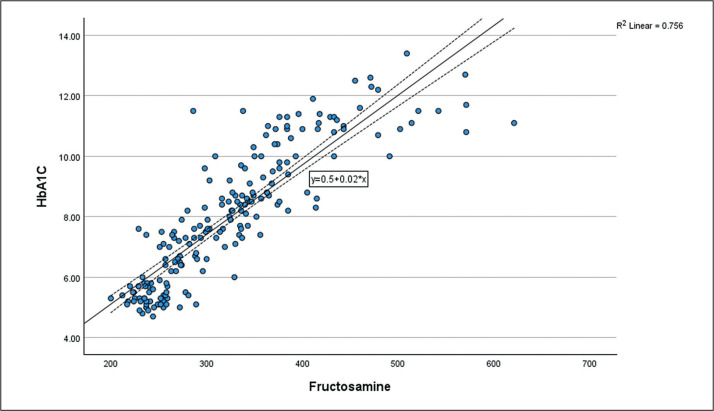

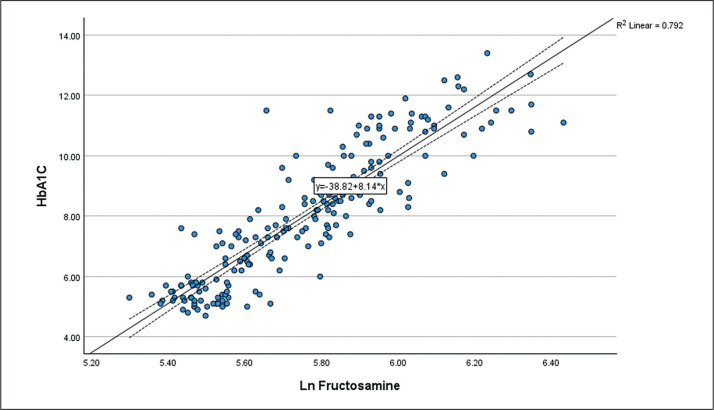

We performed simple linear regression to study the relationship between fructosamine and HbA1c in the research participants (R2 = 0.756, p<0.01) (Figure 2). Further analysis with natural logarithmic transformation of fructosamine demonstrated a stronger correlation between HbA1c and fructosamine (R2 = 0.792, p<0.01). Linear relationship between Ln fructosamine and HbA1c is shown in the scatter plot (Figure 3). This correlation study yields the following:

Figure 2.

Scatter plot of Fructosamine against HbA1c.

Figure 3.

Scatter plot of Ln Fructosamine against HbA1c.

(HbA1c is expressed in % and fructosamine is expressed in umol/L):

HbA1c = (Ln Fructosamine x 8.14) – 38.82

Table 2 lists the estimated corresponding fructosamine values for HbA1c based on the correlation model.

Table 2.

Interpretation of correlation model

| HbA1c (%) | HbA1c (mmol/mol) | Fructosamine (umol/l) |

|---|---|---|

| 6.5 | 47.5 | 261.8 |

| 7.0 | 53.0 | 278.4 |

| 7.5 | 58.5 | 296.0 |

| 8.0 | 63.9 | 314.8 |

| 8.5 | 69.4 | 334.7 |

| 9.0 | 74.9 | 355.9 |

| 9.5 | 80.3 | 378.5 |

| 10.0 | 85.8 | 402.4 |

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a strong correlation between fructosamine and HbA1c in Southeast Asian patients, and this is similar to prior studies in Caucasian populations.3,25,26 HbA1c may ‘average’ out the highs and lows of glucose control for the past 4 months while fructosamine values would only reflect the levels in the preceding month. Furthermore, protein glycation via the Maillard reaction depends on other factors such as the availability and reactivity of amino groups on proteins, intracellular and extracellular glucose concentration, concentration and reactivity of carbonyl compounds and the rate of deglycation and elimination of Maillard products.28 These factors may explain the variability in fructosamine levels for the same HbA1c level. We believe this variability is unlikely to have a major impact on using fructosamine to monitor glycaemic control because there was strong correlation between fructosamine and HbA1c in our research participants.

Our study suggests that fructosamine can be used as a reliable adjunct to HbA1c in monitoring glycaemic control in a Southeast Asian population.

This is the first study on the relationship between fructosamine and HbA1c in a Southeast Asian population. Laboratory analyses were done on fresh blood samples using validated techniques so the chance of erroneous measurements is low. We excluded patients with thyroid disorders because serum protein turnover is lower in hypothyroidism and higher in hyperthyroidism, which leads to increased and decreased protein glycation respectively.29,30 We also excluded patients with protein-losing disorders. Hence, the rates of serum protein turnover and glycation in the study participants were likely to be occurring at steady states.

There are limitations of this study arising from the characteristics of participants. The age of participants is between 22 and 76 years (mean age = 53.7 years) and children were excluded from this study. Thus, it is uncertain whether a similar correlation exists in the paediatric or older Southeast Asian population. However, a correlation was demonstrated in an older Caucasian cohort (mean age = 70 years)13 and in a paediatric cohort in the United Kingdom.3 In addition, patients with anaemia, haemoglobinopathies and those who were pregnant were excluded from this study. Theoretically, fructosamine levels would be a better indicator of glycaemic status in such patients. In patients with protein-losing disorders, the use of fructosamine may be less than ideal. The extent of HbA1c variability with fructosamine levels in these patients could be a subject of further investigation.

This study has limitations arising from the cross-sectional nature of its design. We were unable to conduct sub-group analysis based on differences in age, gender, ethnicity, or recent changes in diabetes medications because of the small sample size. We were unable to account for confounding factors arising from poor adherence to diabetes medication, or deviations in dietary habits or activity levels in this observational study.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we demonstrated a strong correlation between fructosamine and HbA1c in a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population. Fructosamine can be considered as a reliable alternative to HbA1c in monitoring glycaemic control.

Funding Statement

Funding Source None.

Statement of Authorship

All authors certified fulfillment of ICMJE authorship criteria.

CRediT Author Statement

KC: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; SML: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Project administration; LS: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization; ELT: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing, Visualization, Supervision.

Author Disclosure

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Anguizola J, Matsuda R, Barnaby OS, et al. Review: Glycation of human serum albumin. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2013;425: 64-76. PMID: 23891854. PMCID: . 10.1016/j.cca.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoelzel W, Miedema K. Development of a reference system for the international standardization of HbA1c/glycohemoglobin determinations. J Int Fed Clin Chem. 1996;8(2):62-4, 66-7. PMID: 10163516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allgrove J, Cockrill BL. Fructosamine or glycated haemoglobin as a measure of diabetic control? Arch Dis Child. 1988;63(4):418-22. PMID: 3365012. PMCID: . 10.1136/adc.63.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahara Y, Shima K. Kinetics of HbA1c, glycated albumin, and fructosamine and analysis of their weight functions against preceding plasma glucose level. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(4):440-7. PMID: 7497851. 10.2337/diacare.18.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little RR, Roberts WL. A review of variant hemoglobins interfering with hemoglobin A1c measurement. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3(3):446-51. PMID: 20144281. PMCID: . 10.1177/193229680900300307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen RM, Franco RS, Khera PK, et al. Red cell life span heterogeneity in hematologically normal people is sufficient to alter HbA1c. Blood. 2008;112(10):4284-291. PMID: 18694998. PMCID: . 10.1182/blood-2008-04-154112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman BI, Shihabi ZK, Andries L, et al. Relationship between assays of glycemia in diabetic subjects with advanced chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2010;31(5):375-79. PMID: 20299782, 10.1159/000287561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panzer S, Kronik G, Lechner K, Bettelheim P, Neumann E, Dudczak R. Glycosylated hemoglobins (GHb): An index of red cell survival. Blood. 1982;59(6):1348-50. PMID: 7082831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doumatey AP, Feron H, Ekoru K, Zhou J, Adeyemo A, Rotimi CN. Serum fructosamine and glycemic status in the presence of the sickle cell mutation. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;177:108918. PMID: 34126128. PMCID: . 10.1016/j.diabres.2021.108918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker JR, O’Connor JP, Metcalf PA, Lawson MR, Johnson RN. Clinical usefulness of estimation of serum fructosamine concentration as a screening test for diabetes mellitus. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;287(6396):863-7. PMID: 6412861. PMCID: . 10.1136/bmj.287.6396.863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rendell M, Paulsen R, Eastberg S, et al. Clinical use and time relationship of changes in affinity measurement of glycosylated albumin and glycosylated hemoglobin. Am J Med Sci. 1986;292(1):11-4. PMID: 3717201. 10.1097/00000441-198607000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armbruster DA. Fructosamine: Structure, analysis, and clinical usefulness. Clin Chem. 1987;33(12):2153-63. PMID: 3319287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juraschek SP, Steffes MW, Selvin E. Associations of alternative markers of glycemia with hemoglobin A(1c) and fasting glucose. Clin Chem. 2012;58(12):1648-55. PMID: 23019309. PMCID: . 10.1373/clinchem.2012.188367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neelofar K, Ahmad J. A comparative analysis of fructosamine with other risk factors for kidney dysfunction in diabetic patients with or without chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2019;13(1): 240-4. PMID: 30641705. 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvin E, Francis LMA, Ballantyne CM, et al. Nontraditional markers of glycemia: associations with microvascular conditions. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):960-7. PMID: 21335368. PMCID: . 10.2337/dc10-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selvin E, Rawlings AM, Grams M, et al. Fructosamine and glycated albumin for risk stratification and prediction of incident diabetes and microvascular complications: a prospective cohort analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(4):279-88. PMID: 24703046. PMCID: . 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parfitt VJ, Clark JD, Turner GM, Hartog M. Use of fructosamine and glycated haemoglobin to verify self blood glucose monitoring data in diabetic pregnancy. Diabet Med J Br Diabet Assoc. 1993;10(2):162-6. PMID: 8458194. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1993.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arslan E, Allshouse AA, Page JM, et al. Maternal serum fructosamine levels and stillbirth: a case-control study of the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;129(4):619-26. PMID: 34529344. 10.1111/1471-0528.16922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615-24. PMID: 24297872. PMCID: . 10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nik Shanita S, Siti Hanisa A, Noor Afifah AR, et al. Prevalence of Anaemia and Iron Deficiency among Primary Schoolchildren in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(11):2332. PMID: 30360488. PMCID: . 10.3390/ijerph15112332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poh BK, Ng BK, Siti Haslinda MD, et al. Nutritional status and dietary intakes of children aged 6 months to 12 years: Findings of the Nutrition Survey of Malaysian children (SEANUTS Malaysia). Br J Nutr. 2013;110(Suppl 3):S21-35. PMID: 24016764. 10.1017/S0007114513002092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loy SL, Lim LM, Chan SY, et al. Iron status and risk factors of iron deficiency among pregnant women in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):397. PMID: 30975203. PMCID: . 10.1186/s12889-019-6736-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goh LPW, Chong ETJ, Lee PC. Prevalence of Alpha(α)-thalassemia in Southeast Asia (2010-2020): A meta-analysis involving 83,674 subjects. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):E7354. PMID: 33050119. PMCID: . 10.3390/ijerph17207354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fucharoen S, Winichagoon P. Haemoglobinopathies in southeast Asia. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(4):498-506. PMID: 22089614. PMCID: . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malmström H, Walldius G, Grill V, Jungner I, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Hammar N. Fructosamine is a useful indicator of hyperglycaemia and glucose control in clinical and epidemiological studies--cross-sectional and longitudinal experience from the AMORIS cohort. PloS One. 2014;9(10):e111463. PMID: 25353659. PMCID: . 10.1371/journal.pone.0111463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez-Segade S, Rodríguez J, Camiña F. Corrected fructosamine improves both correlation with HbA1C and diagnostic performance. Clin Biochem. 2017;50(3):110-5. PMID: 27777100. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi R, Park MJ, Lee S, Lee SG, Lee EH. Association Among Glycemic biomarkers in Korean adults: hemoglobin A1c, fructosamine, and glycated albumin. Clin Lab. 2021;67(7). PMID: 34258983. 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2020.201133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tessier FJ. The Maillard reaction in the human body. The main discoveries and factors that affect glycation. Pathol Biol (Paris). 2010;58(3):214-9. PMID: 19896783. 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim MK, Kwon HS, Baek KH, et al. Effects of thyroid hormone on A1C and glycated albumin levels in nondiabetic subjects with overt hypothyroidism. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2546-8. PMID: 20823345. PMCID: . 10.2337/dc10-0988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Udupa SV, Manjrekar PA, Udupa VA, Vivian D. Altered fructosamine and lipid fractions in subclinical hypothyroidism. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(1):18-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23449765. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3576741. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2012/5011.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]