Abstract

Rationale

The influence of the lung bacterial microbiome, including potential pathogens, in patients with influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) or coronavirus disease (COVID-19)–associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has yet to be explored.

Objectives

To explore the composition of the lung bacterial microbiome and its association with viral and fungal infection, immunity, and outcome in severe influenza versus COVID-19 with or without aspergillosis.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study in mechanically ventilated patients with influenza and COVID-19 with or without invasive aspergillosis in whom BAL for bacterial culture (with or without PCR) was obtained within 2 weeks after ICU admission. In addition, 16S rRNA gene sequencing data and viral and bacterial load of BAL samples from a subset of these patients, and of patients requiring noninvasive ventilation, were analyzed. We integrated 16S rRNA gene sequencing data with existing immune parameter datasets.

Measurements and Main Results

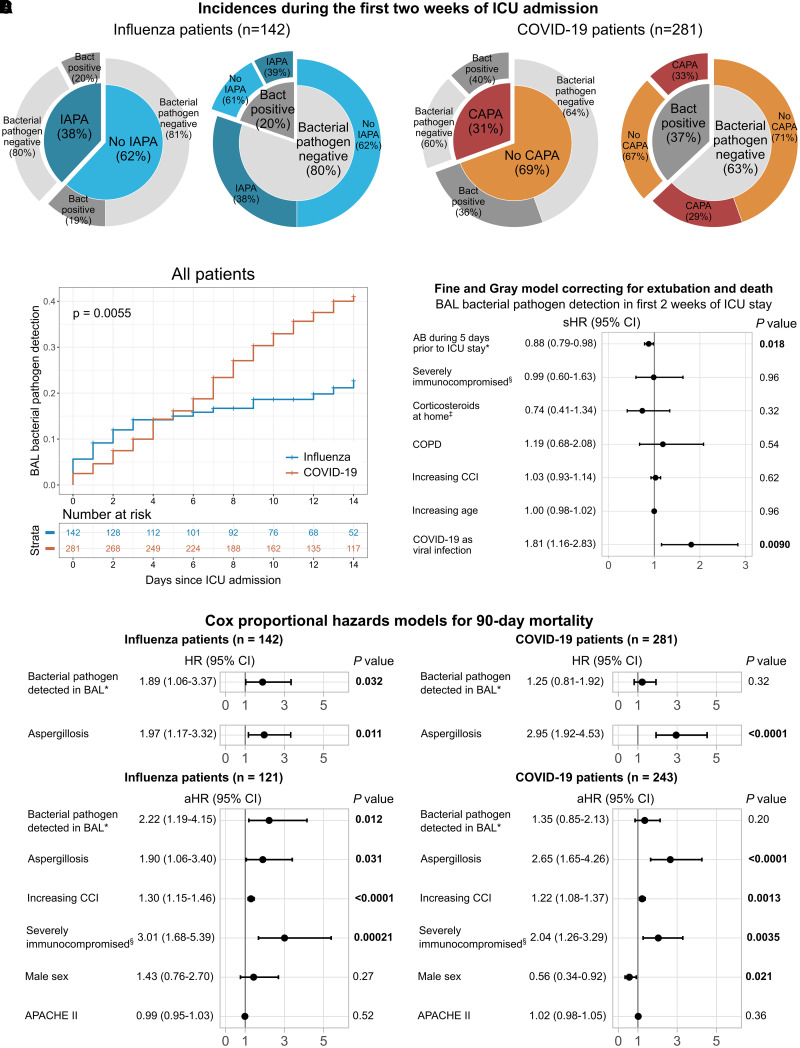

Potential bacterial pathogens were detected in 20% (28/142) of patients with influenza and 37% (104/281) of patients with COVID-19, whereas aspergillosis was detected in 38% (54/142) of patients with influenza and 31% (86/281) of patients with COVID-19. A significant association between bacterial pathogens in BAL fluid and 90-day mortality was found only in patients with influenza, particularly patients with IAPA. Patients with COVID-19, but not patients with influenza, showed increased proinflammatory pulmonary cytokine responses to bacterial pathogens.

Conclusions

Aspergillosis is more frequently detected in the lungs of patients with severe influenza than bacterial pathogens. Detection of bacterial pathogens associates with worse outcome in patients with influenza, particularly in those with IAPA, but not in patients with COVID-19. The immunological dynamics of tripartite viral–fungal–bacterial interactions deserve further investigation.

Keywords: microbiome, influenza, COVID-19, aspergillosis, immunology

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Little is known about the interplay and relevance of multikingdom bacterial and fungal superinfections in severe influenza or coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our results support a diagnostic-driven approach (rather than empirical use of antibiotics) in patients with influenza if clinical deterioration occurs after 3 days of ICU stay. Moreover, our study confirms the need to actively look for aspergillosis in patients with severe influenza and, to a lesser extent, in patients with COVID-19.

Severe viral pneumonia poses a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Each year, on average, 400,000 people die from influenza, whereas the recently emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus caused the deadliest pandemic in a century (1, 2). A superinfection with the fungus Aspergillus is a major complication that may affect patients with severe influenza or coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) and coronavirus disease (COVID-19)–associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) occur in approximately 10–20% of patients admitted to the ICU because of virus-induced respiratory failure and may affect even higher percentages of severely immunocompromised patients (3–7). IAPA and CAPA are associated with higher mortality rates than the viral infection without fungal superinfection, reaching approximately 50% mortality in affected patients (8–10).

As aspergillosis was classically only reported in immunocompromised patients, several studies have sought to understand in which way infection with influenza virus or SARS-CoV-2 affects the antifungal host response or how this immune response differs in patients who develop IAPA or CAPA compared with those who do not (11–14). Although the virus, the fungus, the host, and immunomodulatory drugs are definitively key players in these coinfections, so far little attention has been paid to a potential additional player: the lung microbiome.

Until now, only one study investigated the lung microbiome in the setting of aspergillosis, mainly in immunocompromised patients without severe viral pneumonia (15). Even for COVID-19, only a few studies have looked into the lung bacterial microbiota of patients with severe disease (16–18), whereas for severe influenza only one study that investigated endotracheal aspirates is available (19). Hence, the lung microbiome and its influence in patients with IAPA and CAPA remains to be investigated.

Bacterial superinfections in patients with severe influenza and COVID-19 have been described to occur in approximately 20% and 30–40%, respectively (20–23), with bacterial superinfections being more frequent early after intubation in patients with influenza compared with patients with COVID-19 (24). Conflicting literature exists with respect to the association between bacterial superinfections and mortality in these patients (23–25). Moreover, little is known about the interplay and relevance of multikingdom bacterial and fungal superinfections in severe influenza or COVID-19.

With this study, we aim to obtain insight into the role of the lung bacterial microbiota in patients with severe influenza versus severe COVID-19, with or without aspergillosis. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (26).

Methods

Details about the methods can be found in the online supplement.

Study Cohorts

We performed a retrospective observational study, for which we included adult patients admitted to the ICUs of University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium, a tertiary referral center, who required mechanical ventilation for at least 24 hours because of PCR-proven severe influenza or COVID-19, and in whom a BAL sampling had been performed in the first 14 days of their ICU admission for bacterial and fungal culture (with or without additional galactomannan testing and bacterial PCR for Streptococcus pneumonia, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Chlamydia psittaci, Coxiella burnetii, and/or Legionella pneumophila). The usual trigger for BAL sampling (with or without bacterial PCR) in our center is respiratory deterioration (e.g., upon initiation of mechanical ventilation, increasing fraction of inspired oxygen with increasing inflammation, fever with increased sputum production, or new infiltrates). Patients with influenza admitted to the ICU between October 1, 2009 and March 8, 2020 and patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU between March 1, 2020 and November 14, 2022 were included. We assessed identification of potential respiratory bacterial pathogens (further termed “bacterial pathogens”) through BAL culture or PCR. We assessed the association between bacterial pathogen identification and influenza versus COVID-19 infection with or without invasive aspergillosis and the association between bacterial pathogen identification and outcome.

In addition, we performed 16S rRNA gene sequencing, 16S rRNA gene quantitative PCR (qPCR) (for bacterial load), and viral qPCR (for viral load) on BAL fluid samples available in the hospital biobank of mechanically ventilated patients included in the clinical observational study who were admitted to our ICUs between October 1, 2009 and March 31, 2021. BAL samples from patients requiring noninvasive ventilation for severe influenza or COVID-19 admitted during the same time period were also collected. For each patient, the first collected sample available in the biobank was used (for patients with IAPA or CAPA, the first available sample with positive mycological arguments).

For both study cohorts, patients with recent history of invasive aspergillosis (within 3 months before ICU admission) and/or active treatment for non–viral-associated invasive aspergillosis at the time of ICU admission were excluded.

Probable (relying on BAL fluid or serum for mycology) and proven (requiring histology) cases of IAPA and CAPA were defined according to the criteria defined by Verweij and colleagues (27) and Koehler and colleagues (28) (see Tables E1 and E2 in the online supplement).

The study was approved and the need for informed consent was waived by the hospital Ethical Committee (as part of protocol S65588).

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Analyses

Bacterial DNA was extracted, amplified, and sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform according to previously published protocols (29). After sequencing quality control, raw 16S rRNA reads were processed to obtain counts of amplicon sequence variants by following the DADA2 R package pipeline (version 1.24.0) (30), and taxonomy was assigned using the SILVA 16S rRNA database (version 138) (31). Additional quality control was performed using four negative control samples (sterile water) to correct for possible contamination background using the R package decontam (version 1.20.0) (32). We characterized α diversity metrics (reflecting species richness and evenness in a single sample), including the observed number of species and the Shannon and Simpson indices. Regarding β diversity metrics (measuring variability in community composition between samples), we computed Aitchison distances. Data were normalized by transforming the counts to centered log-ratios.

Integration with Immune Parameters

16S rRNA gene sequencing data and clinical bacterial pathogen identification data (culture or PCR) were integrated with previously published immunological data (gene expression and/or cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor concentrations) available for most of the samples (12).

Viral and Bacterial Load

qPCR was performed using universal primers for influenza A virus, influenza B virus, SARS-CoV-2, and the 16S rRNA gene to assess viral and bacterial load.

Statistical Analyses

For univariable clinical statistical analyses, Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical data, Student’s t test or ANOVA for parametric continuous data, and Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis test for nonparametric continuous data, unless specified otherwise. Permutational multivariate ANOVA was performed to identify significant differences in β diversities. Identification of significantly differentially abundant taxa was addressed using the Mann-Whitney U test, linear models, and selbal (33). Spearman’s rank correlation was used for correlation analyses. Gray’s test was used to compare cumulative incidences of bacterial pathogen detection among patients with influenza versus patients with COVID-19 with or without aspergillosis, and, in addition, a Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model was used to correct for competing risks (extubation or death) and relevant clinical factors (antibiotic and corticosteroid use, immunosuppression, age, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Survival analyses were performed using multivariable Cox proportional hazards models for 30-day and 90-day mortality, with BAL bacterial pathogen identification or aspergillosis as time-dependent variables, with or without additional relevant clinical variables (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, Charlson Comorbidity Index, sex, and immunosuppression). We performed correction for multiple testing in high-throughput analyses using Benjamini-Hochberg’s false discovery rate method.

Results

Clinical Observational Cohort

We identified 501 adult patients who received at least 24 hours of mechanical ventilation in our ICUs because of severe influenza or COVID-19 in the study period. Bacterial culture (with or without additional bacterial PCR) was performed on BAL fluid in 423 patients (142 patients with influenza and 281 patients with COVID-19) within the first 2 weeks after ICU admission, and these patients were included in downstream statistical analyses (Tables 1 and E3–E6). More than 90% (258/281) of patients with COVID-19 received high-dose corticosteroids (⩾20 mg prednisone equivalent dose) during the first 2 weeks of their ICU stay, compared with 70% (99/142) of the patients with influenza. Patients with influenza received antibiotics significantly more often than patients with COVID-19 in the 5 days preceding ICU admission, whereas almost all patients received antibiotics within the first 2 weeks of their ICU stay (median duration, 11 d for both the influenza and COVID-19 cohorts) (Tables 1 and E4). Within the first 2 weeks of the ICU stay, proven or probable IAPA was diagnosed in 38% (54/142) of patients with influenza and CAPA in 31% (86/281) of patients with COVID-19 (Tables 1 and E3 and Figure 1A).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Clinical Observational Cohort (N = 423)

| Influenza (n = 142) | COVID-19 (n = 281) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 78 (55) | 200 (71) | 0.0011 |

| Mean age, yr, (SD) | 59 (14) | 63 (11) | 0.0032 |

| Median BMI (IQR) | 26 (23–30) | 28 (25–33) | 0.00030 |

| COPD | 23 (16) | 37 (13) | 0.46 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 8 (5.6) | 3 (1.1) | 0.0085 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (18) | 102 (36) | 0.00013 |

| EORTC/MSGERC host factor* | 39 (27) | 70 (25) | 0.64 |

| Solid organ transplant | 17 (12) | 46 (16) | 0.25 |

| Hematological malignancy | 9 (6.3) | 17 (6.0) | 1 |

| Allogeneic HSCT | 3 (2.1) | 4 (1.4) | 0.69 |

| Recent prolonged neutropenia | 5 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0.0041 |

| Recent prolonged high-dose CS | 7 (4.9) | 3 (1.1) | 0.035 |

| T- or B-cell immunosuppressants | 27 (19) | 62 (22) | 0.53 |

| Inherited severe immunodeficiency | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Low-dose CS† as home medication | 26 (18) | 58 (21) | 0.61 |

| Received antibiotics in 5 d before ICU admission | 97 (68) | 140 (50) | 0.00029 |

| Received antibiotics in first 14 d of ICU stay | 141 (99.3) | 280 (99.6) | 1 |

| Median APACHE II score at ICU admission (IQR) | 27 (21–31) (n = 121) | 20 (16–26) (n = 243) | <0.00001 |

| Median Charlson Comorbidity Index at ICU admission (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (2–4) | 0.33 |

| CS (daily dose ⩾ 20 mg prednisone equivalent) as treatment in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 99 (70) | 258 (92) | <0.00001 |

| Tocilizumab in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 0 | 14 (5.0) | 0.0035 |

| Received MV | 142 (100) | 281 (100) | 1 |

| Median days of MV (IQR) | 11 (7–19) | 15 (9–26) | 0.0017 |

| Received ECMO | 29 (20) | 60 (21) | 0.90 |

| Median days of ECMO (IQR) | 10 (7–14) (n = 29) | 14 (10–24) (n = 60) | 0.025 |

| Required RRT | 44 (31) | 63 (22) | 0.059 |

| Median days ICU stay (IQR) | 18 (11–30) | 26 (16–43) | 0.00001 |

| Median days hospital stay (IQR) | 34 (21–56) | 40 (24–64) | 0.050 |

| BAL culture performed in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 142 (100) | 281 (100) | 1 |

| BAL bacterial PCR performed in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 123 (87) | 240 (85) | 0.77 |

| Bacterial pathogen positive in BAL culture or PCR in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 28 (20) | 104 (37) | 0.00025 |

| Median days between ICU admission and first positive sample for bacterial pathogen (IQR) | 2 (0–5) (n = 28) | 7 (3–9) (n = 104) | 0.00039 |

| Probable/proven aspergillosis during ICU stay‡ | 59 (42) | 104 (37) | 0.40 |

| Median days between ICU admission and first mycological evidence of IAPA or CAPA (IQR) | 4 (2–8) (n = 59) | 6 (3–12) (n = 104) | 0.015 |

| IAPA/CAPA diagnosed in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 54/59 (92) | 86/104 (83) | 0.16 |

| Bacterial pathogen positive in BAL culture/PCR in first 2 wk of ICU stay in patients with IAPA/CAPA diagnosis in first 2 wk of ICU stay | 11/54 (20) | 34/86 (40) | 0.025 |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; BMI = body mass index; CAPA = COVID-19–associated pulmonary aspergillosis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; CS = corticosteroids; ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; EORTC = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; GM = galactomannan; GVHD = graft-versus-host disease; HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; IAPA = influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis; IQR = interquartile range; MSGERC = Mycosis Study Group Education and Research Consortium; MV = mechanical ventilation; RRT = renal replacement therapy.

Data are given as n (%) unless otherwise noted. P values were calculated for categorical variables by Fisher’s exact test and for continuous variables with Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test where appropriate.

EORTC/MSGERC host factors for invasive mold disease (34).

Daily dose below the EORTC/MSGERC corticosteroid host factor cutoff as chronic home medication.

Figure 1.

Incidence and associations with outcome of a positive culture or PCR for a bacterial pathogen in BAL fluid, or invasive aspergillosis, during the first 2 weeks of ICU admission in patients mechanically ventilated for influenza or coronavirus disease (COVID-19). (A) Incidence of invasive aspergillosis and bacterial pathogen identification in BAL fluid in the first 2 weeks since ICU admission, subdivided in the influenza and COVID-19 cohorts. (B) Cumulative incidence curves of patients with influenza and patients with COVID-19 showing incidence of a positive bacterial pathogen in BAL culture or PCR during the first 2 weeks of their ICU stay. Censoring was performed at extubation, death, or after 14 days after ICU admission. Gray’s test P value is shown. Risk table shows the number of patients at risk at the start of the day since ICU admission. (C) Forest plot showing the results of the Fine and Gray model for 14-day incidence of a positive bacterial pathogen BAL culture or PCR, correcting for competing risks (extubation or death) and relevant clinical factors. Fine and Gray model incorporating antibiotic and corticosteroids use during ICU stay can be found in Figure E2. *Number of days on antibiotics during the 5 days preceding ICU stay. §Severely immunocompromised, as defined by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and Mycosis Study Group Education and Research Consortium (EORTC/MSGERC) host factors for invasive mold disease (34). ‡Low-dose (below EORTC/MSGERC cutoff) corticosteroids as home medication. (D) Cox proportional hazard models for 90-day mortality in patients with influenza or COVID-19. Two univariable models (with bacterial pathogen identification in BAL fluid during the first 2 weeks of ICU admission, or aspergillosis throughout the ICU stay) and a similar model with additional relevant clinical variables are shown for the influenza cohort and the COVID-19 cohort. The number of patients included in the large multivariable models is lower because of missing data for APACHE II scores on ICU admission. In all models, bacterial pathogen identification and aspergillosis are modeled as time-dependent variables. *Detected in BAL fluid during the first 2 weeks of ICU stay through culture or PCR. §Severely immunocompromised, as defined by the EORTC/MSGERC host factors for invasive mold disease (34). Cox proportional hazards models for 30-day mortality are illustrated in Figure E3. AB = antibiotics; APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; Bact = bacterial; CAPA = COVID-19–associated pulmonary aspergillosis; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR = hazard ratio; IAPA = influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis; sHR = subdistribution hazard ratio.

Bacterial Pathogens Are Identified in BAL Fluid More Often in Patients with COVID-19 but Are Only Associated with Outcome in Patients with Influenza

A bacterial pathogen was cultured from or detected by PCR in BAL fluid during the first 2 weeks of the ICU stay in 20% (28/142) of patients with influenza and 37% (104/281) of patients with COVID-19 included in the clinical observational cohort (Tables 1, E5, and E6 and Figure 1A). Identification of a bacterial pathogen in the first 2 weeks of the ICU stay was therefore more frequent than CAPA in patients with COVID-19. However, in our influenza cohort screened for superinfection, IAPA was more frequent than bacterial pathogen identification in the first 2 weeks of ICU admission (Figure 1A). The most frequently detected bacterial pathogens were Streptococcus and Klebsiella species (Table E7). Cumulative incidences of bacterial pathogen detection were similar in patients with influenza and patients with COVID-19 in the first 3 days after ICU admission but then plateaued for patients with influenza, while still increasing steadily for patients with COVID-19 (mainly due to typical hospital-acquired pathogens, such as Klebsiella species), in the second week of the ICU stay (Figure 1B). Patients who developed aspergillosis had similar rates of bacterial pathogen positivity compared with patients with influenza or COVID-19 who did not develop aspergillosis (Figure E1). Fine and Gray modeling correcting for competing risks and relevant clinical factors corroborated that patients with COVID-19 had a higher risk for identification of a bacterial pathogen in BAL fluid during the first 2 weeks of ICU admission than patients with influenza (Figures 1C and E2). This was independent of antibiotic or corticosteroid use before or during their ICU stay.

We found no association between BAL bacterial pathogen identification and 30-day and 90-day mortality in patients with COVID-19, whereas we did observe a significant association in patients with influenza (Figures 1D and E3). Aspergillosis was associated with increased 90-day mortality in both viral infection cohorts (but with 30-day mortality in the COVID-19 cohort only). These observations stayed similar when adjusting for relevant clinical factors (Figures 1D and E3). We found a 90-day mortality exceeding 80% (9/11) in patients with influenza with aspergillosis and BAL bacterial pathogen detection within the first 2 weeks of ICU admission.

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Cohort

To explore the lower respiratory tract microbiome composition of patients with severe influenza versus COVID-19 in more detail, we performed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on biobanked BAL samples from 163 patients who required ICU admission because of severe influenza or COVID-19. We subdivided the influenza and COVID-19 groups based on aspergillosis status at the time of sampling. The samples of 162 patients passed sequencing quality control: 89 in the influenza cohort (50 patients with influenza only and 39 patients with IAPA) and 73 in the COVID-19 cohort (39 patients with COVID-19 only and 34 patients with CAPA) (Figure 2A). Of these 162 patients, 146 received mechanical ventilation and were included in the clinical observational study discussed above as well. Most samples were obtained during the first week of the ICU admission. Tables E8 and E9 show the clinical and sample characteristics of the 162 patients included in statistical analyses.

Figure 2.

BAL 16S rRNA gene sequencing analyses. (A) Study design and number of included patients in the BAL bacterial microbiome study. Figure created with aid of Biorender.com. (B) Multidimensional scaling plot showing bacterial β diversity (according to Aitchison distance metrics) of BAL fluid, with patients stratified for viral–fungal infection type. (C) α diversity metrics calculated in BAL fluid, with patients stratified for viral–fungal infection type. P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. (D) Relative abundance of the most abundant classified genera in all patients. See Figure E6 for the plot including the most abundant unclassified genera. (E) Relative abundance of genera per patient, stratified for viral–fungal infection type. Each bar on the x-axis represents a single patient. (F) Boxplots showing relative abundances of the nine most prevalent identified genera, with patients stratified for viral–fungal infection type. P values calculated by Student’s t test are shown. See Figure E6 for the plot with P values calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. (G) Dot plot depicting significantly enriched or depleted species at P < 0.05 in the four relevant viral–fungal infection type comparisons. Size of the dots is determined by number of positive tests (Mann-Whitney U test, linear models or selection of balances). See Figure E8 for details on the specific tests that were positive for each significantly enriched or depleted species and for details regarding significant results after correction for multiple testing. CAPA = coronavirus disease (COVID-19)–associated pulmonary aspergillosis; IAPA = influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis.

Bacterial α and β Diversity Indices Are Similar in Patients with Severe Viral Pneumonia with or without Aspergillosis

Visualization of the communities by multidimensional scaling showed limited segregation among the four groups, with the least dispersion within the influenza-only and IAPA groups (Figure 2B). After correction for multiple testing, we found no significant association of aspergillosis with β diversity at the species or genus level using permutational multivariate ANOVA in the influenza cohort or in the COVID-19 cohort (Table E10). However, the type of viral infection did show a significant association with β diversity in the non-aspergillosis cohort. In the pooled patients with influenza, use of antibiotics in the 14 days before BAL sampling and positivity of one or more host factors for invasive mold disease (34) were associated with β diversity differences.

In an earlier study, Hérivaux and colleagues reported significantly lower bacterial α diversity in patients with invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) compared with control patients with initially suspected but eventually disproven IPA (15). We reanalyzed their dataset, including only patients admitted to ICU for whom data was available (n = 39), and observed the same results (Figure E4). In contrast, in our dataset, we noted no significant differences between the four disease groups in terms of α diversity measures (Figure 2C). For influenza versus COVID-19, this aligns with earlier observations in endotracheal aspirates (19). We also did not find significant differences in α diversity indices in patients with versus without a positive bacterial culture or PCR in the study sample (Figure E5).

Patients with Influenza and Patients with COVID-19 with or without Aspergillosis Show Minor Microbiome Composition Differences

We analyzed the composition of lung microbiota at the genus level (Figures 2D–2F and E6). A significant proportion of the bacterial reads could not be subtyped to the genus level (e.g., Unclassified.G75) and could constitute species that have not been identified to date, or contamination, which is encountered (even after quality control) across different pipelines and in other BAL studies as well, especially in critically ill patients (Figures E6 and E7) (16). The most abundant identifiable genera were Streptococcus, Prevotella, Staphylococcus, and Haemophilus, which may all be found in healthy lung microbiota as well. In a parametric analysis, we found little difference comparing fractions of the most abundant genera, with the exception of higher fractions of Streptococcus and Cutibacterium in patients with influenza only compared with other patient groups before correction for multiple testing (Figure 2F and Table E11). The higher relative abundance of these genera was largely driven by few patients with influenza only with high relative abundances of these genera, as most comparisons were not significant in nonparametric univariable analysis (Figure E6 and Table E12).

Regarding specific species, we found significantly enriched or depleted species in the four different disease comparisons using the univariable Mann-Whitney U test and multivariable linear models and selection of balances correcting for age, presence of host factors for invasive mold disease (34), and the number of days between the start of mechanical ventilation and study BAL sampling, although most significant findings were lost after correction for multiple testing (Figures 2G and E8). The IAPA versus CAPA comparisons yielded the highest numbers of significantly differentially abundant species. We found differences in species that are typically encountered in the healthy human lung (35): several Streptococcus species were depleted in patients with CAPA compared with patients with COVID-19 only and patients with IAPA, whereas several Veillonella and Prevotella species were either enriched or depleted in these comparisons.

We then interrogated the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data to find pathogens that were identified through bacterial culture or PCR. We found significantly higher relative abundances by 16S rRNA gene sequencing of Klebsiella and Streptococcus species (the most frequently detected species through culture or PCR) in patients in whom these pathogens were cultured or positive on PCR in the same sample (Figure E9).

Patients with Influenza Show a Less-pronounced Response to the Presence of Bacterial Pathogens

We integrated α diversity indices with published protein concentrations of the same BAL samples (47 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors) (Table E13) (12). We observed moderate negative correlations between α diversity and proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β or IL-8) in patients with influenza only but not in patients with IAPA. Patients with COVID-19 only and patients with CAPA showed moderate positive correlations between some proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1α and IL-1β) and α diversity (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Integration with existing BAL immune parameters. (A) Correlogram showing correlations between Shannon and Simpson diversity indices and previously published concentrations of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors on the same BAL sample (12). Only proteins for whom a significant correlation was found are shown. Color legend shows the range of Spearman’s rho. *P value < 0.05, **P value < 0.01, and ***P value < 0.001. (B) Boxplots showing levels of IL-1β and TNF in BAL fluid, stratified for negative or positive culture or PCR results for a bacterial pathogen in the same sample. P values obtained by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. (C) Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in patients with influenza and in patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) with versus without a positive BAL culture or PCR for a bacterial pathogen on the same sample. For the volcano plot in patients with COVID-19, the cutoff at 0.05 Benjamini-Hochberg FDR is shown. Significant DEGs of interest are annotated. CAPA = COVID-19–associated pulmonary aspergillosis; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease; FDR = false discovery rate; IAPA = influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis.

Positivity of a bacterial pathogen in culture or PCR, however, was associated with major differences in the BAL immune landscape of patients with COVID-19 (irrespective of the presence of aspergillosis), illustrated by significantly higher concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF, and CCL20 compared with patients without a bacterial pathogen in BAL fluid (Figures 3B, E10, and E11 and Table E14) (36). In patients with influenza, we noticed a nonsignificant increase of proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines if bacterial pathogens were detected. Given this signal, we interrogated the published expression of 755 genes linked to innate immunity in the same BAL samples (Table E13) (12). The hyperinflammatory responses to bacterial pathogens seen in patients with COVID-19, and, in contrast, the less-pronounced responses in patients with influenza, were reflected in gene expression as well; although patients with COVID-19 showed significant upregulation of 57 genes, many linked to inflammation (such as IL1B, TNF, HIF1A, and CCRL2), if a bacterial pathogen was present, we found no significantly differentially expressed genes after correction for multiple testing comparing patients with influenza with versus those without a bacterial pathogen in the BAL sample (Figure 3C).

Lower Bacterial α Diversity but Not Bacterial or Viral Load Is Associated with Positive Aspergillus BAL Culture in IAPA

Positivity of Aspergillus culture is seen in approximately half of the patients with IAPA or CAPA and reflects higher fungal burden. We found significantly reduced bacterial α diversity in patients with IAPA (but not patients with CAPA) with Aspergillus culture positivity (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Associations between BAL Aspergillus culture results and bacterial α diversity indices, viral load, and bacterial load. (A) Boxplots showing Shannon and Simpson diversity indices in BAL fluid stratified for positive or negative Aspergillus culture results in the same sample in patients with influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA) and patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19)–associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA). P values obtained by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. (B) Study design and number of included patients in the BAL viral and bacterial load study. Figure created with aid of Biorender.com. (C) Boxplots showing the association between BAL bacterial culture, PCR or oral flora (through direct microscopy or culture) results, and 16S rRNA gene cycling threshold (Ct) value on the same BAL sample. Lower Ct value indicates higher bacterial load. P values obtained by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. (D) Boxplots showing the association between BAL viral load (represented as normalized viral log10 copies/ml) for influenza A, influenza B, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and underlying disease. P values obtained by a generalized linear model correcting for time between ICU admission and BAL sampling are shown. (E) Boxplots showing the association between BAL bacterial load and underlying disease. Lower Ct value indicates higher bacterial load. P values obtained by Mann-Whitney U test are shown. (F) Boxplots showing the association between BAL viral load (represented as normalized viral log10 copies/ml) for influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2 and underlying BAL Aspergillus culture positivity in patients with IAPA and CAPA. P values obtained by a generalized linear model correcting for time between ICU admission and BAL sampling are shown, except (*) for influenza B, where a P value obtained by Mann-Whitney U test is shown. (G) Boxplots showing the association between bacterial load and underlying BAL Aspergillus culture positivity in patients with IAPA and CAPA. Lower Ct value indicates higher bacterial load. P values obtained by Mann-Whitney U test are shown.

We further assessed the association between the burden of bacteria and viruses with the presence of Aspergillus in the lower respiratory tract by determining viral and bacterial load in BAL fluid of patients included in the 16S rRNA gene sequencing cohort through viral qPCR (n = 109) and bacterial 16S rRNA gene qPCR (n = 81) (Figure 4B). As expected, the bacterial load was significantly higher (reflected by lower qPCR cycling threshold values) in BAL fluid positive for bacteria via culture or PCR by the clinical lab, or in which oral flora was present on microscopy or culture (Figures 4C and E12). There were no significant differences in viral or bacterial load and the presence of aspergillosis, except for higher bacterial loads in patients with CAPA (Figures 4D and 4E), or in viral or bacterial load and Aspergillus culture positivity in patients with IAPA or CAPA (Figures 4F and 4G).

We found no significant associations between 90-day mortality and viral load, bacterial load, or bacterial α diversity in the four patient groups, although we observed a trend toward higher mortality with higher bacterial load in the pooled patient groups (P = 0.073) (Figure E13). In line with previous literature (37), Aspergillus culture positivity was significantly associated with 90-day mortality (Figure E14).

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we explored the role of potential bacterial pathogens and microbiota in the lower respiratory tract of patients with severe viral pneumonia with or without aspergillosis. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the lung microbiomes of patients with severe influenza versus severe COVID-19 using BAL fluid. Moreover, with this work, we open the field of microbiome research in viral–fungal coinfections in critically ill patients. By incorporating our findings with data on cellular and molecular immune components and clinical characteristics, we have also obtained crucial insights into the associations between lung bacterial pathogens, microbiota, the host response, and outcome in these viral–fungal coinfections.

We observed that bacterial pathogens were detected significantly more often in BAL fluid of patients with COVID-19 than patients with influenza, even when correcting for competing risks (extubation or death) and clinical confounders (such as corticosteroids or antibiotic administration). This was largely driven by a linear increase in the identification of gram-negative pathogens during the first 2 weeks of the ICU stay, reflecting hospital- and ventilator-associated pneumonia, whereas most pathogens in patients with influenza were identified in the first 3 days of the ICU admission. Exemplary is Klebsiella, which was identified often in COVID-19 but not in a single case of influenza. Our results, therefore, support a diagnostic-driven approach (rather than empirical use of antibiotics) in patients with influenza if clinical deterioration occurs after 3 days of ICU stay. Moreover, we found that in mechanically ventilated patients with influenza, aspergillosis is more common than a suspected secondary bacterial infection based on the presence of bacterial pathogens in BAL fluid. This confirms the previously stressed need to actively look for aspergillosis in all critically ill patients with influenza (38).

We found an association between identification of a bacterial pathogen and outcome in the influenza cohort but not in patients with COVID-19. For COVID-19, this is in line with previously published research (17, 24, 39), whereas, for influenza, it contrasts with a previous comparative multicenter study (24). Within the influenza cohort, patients showed a particularly dismal outcome if both aspergillosis and a bacterial pathogen were identified within the first 2 weeks of the ICU stay. Moreover, we found no differences in the immune response of patients with influenza with or without the presence of a bacterial pathogen in the lungs, compared with a strong proinflammatory response in the presence of bacterial pathogens in patients with COVID-19. These findings point to severely hampered bacterial recognition and/or downstream inflammatory responses to bacteria in patients with severe influenza, leading to a more pronounced clinical impact of the pathogen in these patients compared with patients with COVID-19. Taking into account our previously published results on the immune response against aspergillosis in largely the same cohort as the one presented here (12), we can conclude that patients with influenza show reduced expression of genes related to anti-Aspergillus immunity when IAPA is present and a largely similar expression of immunity-related genes regardless of whether a bacterial pathogen is present or not. From a clinical point of view, this translates into higher rates of Aspergillus angio-invasion in IAPA compared with CAPA (9) and worse outcome if lung bacterial pathogens are present in patients with influenza compared with patients with COVID-19. Moreover, the finding of early but not late bacterial coinfection in patients with influenza aligns with the often early detection of aspergillosis in these patients (40), whereas both bacterial and Aspergillus detection are incremental during the first weeks of an ICU stay in patients with COVID-19 (4). The effect of influenza on the antifungal and antibacterial host response, therefore, seems to be earlier and at the same time more immunoparalyzing than the effect of COVID-19. Although poor outcome is likely driven by severe hyperinflammation in severe COVID-19, it may be more driven by bacterial and/or fungal superinfection in severe influenza.

We did not observe any association between bacterial α diversity and outcome in the four disease groups. This is in line with several large studies in BAL fluid of critically ill patients with COVID-19 (16, 17) and now appears to be the case in patients with severe influenza as well. Strikingly, we did find an association between bacterial α diversity and BAL galactomannan values or Aspergillus culture positivity in patients with IAPA specifically. The more convincing the supporting mycological evidence is for IAPA, the lower the bacterial α diversity, mirroring what is seen in patients with classical risk factors for IPA (15). The fact that we did not observe this association in patients with CAPA aligns with earlier findings that aspergillosis seems to have a less significant impact on the lung immune environment in the setting of severe COVID-19 than in the setting of severe influenza (12). We further observed no differences in viral load between patients with IAPA or CAPA and patients with severe viral pneumonia without aspergillosis. In contrast, we observed higher bacterial loads in patients with CAPA compared with the other disease groups, despite our observation that bacterial superinfection is not more frequent in patients with versus those without aspergillosis. This could imply more pronounced spillover and impaired mucociliary clearance of oral flora in these patients, but this was not apparent from the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data and thus deserves further investigation.

Our study has several limitations. First, the study samples for 16S rRNA gene sequencing were retrospectively collected from our hospital biobank. The collection time point during the ICU stay was generally similar for patients within the influenza cohort and within the COVID-19 cohort but was slightly delayed in the COVID-19 versus the influenza cohort. A prospective multicentric study, including protocol-based (rather than clinical indication–based) longitudinal assessment of superinfections and the lung microbiota, would allow us to obtain more information on the generalizability of our results. Second, a proportion of the bacterial reads in most samples were not subtypable to the genus or species level, and, as such, it is possible that we lack a full picture of the lung bacterial species composition in our patients. Third, combination with Internal Transcribed Spacer amplicon sequencing, or performing shotgun metagenomics, could provide access to other microbiome components, such as fungal mycobiota. However, BAL samples are not ideal for such approaches given the dilution of biological material in these samples and given the need for deep sequencing, as the DNA composition in BAL fluid is often dominated by host cells rather than that of microorganisms. Fourth, the COVID-19 cohort in the 16S rRNA gene sequencing analyses consisted almost exclusively of (previously) immunocompetent patients, whereas patients with severe COVID-19, especially those who develop aspergillosis, are now often severely immunocompromised (7, 41). Fifth, the presence of pathogenic bacteria only indicates a potential for infection, as many of these species can be commensals or colonizers. To obtain more insight into the potential causative role the microbiome composition has in the incidence and severity of IAPA or CAPA, longitudinal studies and animal work will be required.

In conclusion, our results show the relevance of studying tripartite viral–fungal–bacterial pathogen interactions in addition to the classical viral–fungal and viral–bacterial coinfections. In addition to bacterial superinfection, aspergillosis must be looked for in all critically ill patients with influenza. Prospective studies investigating the lung microbiome, providing integration with metabolomics and animal work, will be required to improve our insight in the complex interplay between the host, virus, fungus, and bacteria.

Supplemental Materials

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Pedro González Torres and Nuria Escudero (Microomics, Barcelona, Spain) for their aid with the 16S rRNA gene sequencing of our samples. They also thank Doreen Brysens and Lauren Van Der Sloten (formerly University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium) for their aid with constructing the clinical database.

Footnotes

Supported by Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek grant G053121N (S.H.-B. and J.W.) and grants G0A0621N and G065421N (J.V.W.) and Ph.D. grants 11M6922N and 11M6924N (S.F.), 11PBR24N (J.H.), 1186121N and 1186123N (L.S.), and 11E9819N (L.V.); the Universitaire Ziekenhuizen Leuven, KU Leuven “Coronafonds” (J.W.); the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia grants UIDB/50026/2020, UIDP/50026/2020, and PTDC/MED-OUT/1112/2021 (https://doi.org/10.54499/PTDC/MED-OUT/1112/2021) (A.C.), and 2022.06674.PTDC (https://doi.org/10.54499/2022.06674.PTDC) and CEECIND/04058/2018 (https://doi.org/10.54499/CEECIND/04058/2018/CP1581/CT0015) (C.C.); the “la Caixa” Foundation under the agreement LCF/PR/HR22/52420003 (MICROFUN) (C.C.); and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Programme grant agreement number 847507 (Host-Directed Medicine in Invasive Fungal Infections) (F.L.v.d.V., A.C., and J.W.). For this research, the Toni Gabaldón group acknowledges support from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación for grants PID2021-126067NB-I00, CPP2021-008552, PCI2022-135066-2, and PDC2022-133266-I00, cofounded by ERDF “A way of making Europe”; the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca grant SGR01551; European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme grant ERC-2016-724173; Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation grant GBMF9742; “La Caixa” foundation grant LCF/PR/HR21/00737; and Instituto de Salud Carlos III grants IMP/00019 and CIBERINFEC CB21/13/00061-ISCIII-SGEFI/ERDF.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: S.F., J.V.W., A.C., J.W., and T.G. Methodology: S.F., M.C.-B., A.S., J.V.W., L.N., A.C., J.W., and T.G. Formal analysis: S.F., M.C.-B., and A.R.-R. Investigation: S.F., C.J., H.M.L., A.S., S.G., C.C., Y.D., G.H., J.H., S.H.-B., K.L., L.M., P.M., M.P., A.R.-R., L.S., M.R.S., K.T., G.V.V., C.V., L.V., A.W., L.N., F.L.v.d.V., and J.V.W. Figures: S.F. and M.C.-B. Resources: J.V.W., A.C., J.W., and T.G. Data curation: S.F., M.C.-B., A.S., T.G., and A.C. Writing – original draft: S.F. and M.C.-B. Writing – review & editing: S.F., M.C.-B., C.J., H.M.L., A.S., S.M.G., C.C., Y.D., G.H., J.H., S.H.-B., K.L., P.M., L.N., M.P., A.R.-R., L.S., M.R.S., K.T., G.V.V., C.V., L.V., A.W., F.L.v.d.V., J.V.W., T.G., J.W., and A.C. Funding acquisition: S.H.-B., G.V.V., J.V.W., T.G., J.W., and A.C.

Data availability: All sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under the BioProject ID PRJNA1045644. Gene expression data used in this manuscript are available in the appendix of the publication in which these data were featured originally (Reference 12). The analytical codes for the 16S rRNA gene sequencing analyses are available under https://github.com/Gabaldonlab/lung_microbiome_16S.

A data supplement for this article is available via the Supplements tab at the top of the online article.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202401-0145OC on June 12, 2024

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Paget J, Spreeuwenberg P, Charu V, Taylor RJ, Iuliano AD, Bresee J, et al. Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network and GLaMOR Collaborating Teams Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: new burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR Project. J Glob Health . 2019;9:020421. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi Z-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol . 2021;19:141–154. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00459-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schauwvlieghe AFAD, Rijnders BJA, Philips N, Verwijs R, Vanderbeke L, Van Tienen C, et al. Dutch-Belgian Mycosis study group Invasive aspergillosis in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with severe influenza: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2018;6:782–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prattes J, Koehler P, Hoenigl M, Wauters J, Giacobbe DR, Lagrou K, et al. ECMM-CAPA Study Group COVID-19 associated pulmonary aspergillosis: regional variation in incidence and diagnostic challenges. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:1339–1340. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06510-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Janssen NAF, Nyga R, Vanderbeke L, Jacobs C, Ergün M, Buil JB, et al. Multinational observational cohort study of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Emerg Infect Dis . 2021;27:2892–2898. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.211174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gangneux J-P, Dannaoui E, Fekkar A, Luyt C-E, Botterel F, De Prost N, et al. Fungal infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 during the first wave: the French multicentre MYCOVID study. Lancet Respir Med . 2022;10:180–190. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feys S, Lagrou K, Lauwers HM, Haenen K, Jacobs C, Brusselmans M, et al. High burden of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) in severely immunocompromised patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Clin Infect Dis . 2024;78:361–370. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rijnders BJA, Schauwvlieghe AFAD, Wauters J. Influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: a local or global lethal combination? Clin Infect Dis . 2020;71:1764–1767. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feys S, Almyroudi MP, Braspenning R, Lagrou K, Spriet I, Dimopoulos G, et al. A visual and comprehensive review on COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) J Fungi (Basel) . 2021;7:1067. doi: 10.3390/jof7121067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Sprute R, Cunha C, Oliverio M, Goldman GH, et al. COVID-19-associated fungal infections. Nat Microbiol . 2022;7:1127–1140. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tappe B, Lauruschkat CD, Strobel L, Pantaleón García J, Kurzai O, Rebhan S, et al. COVID-19 patients share common, corticosteroid-independent features of impaired host immunity to pathogenic molds. Front Immunol . 2022;13:954985. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.954985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feys S, Gonçalves SM, Khan M, Choi S, Boeckx B, Chatelain D, et al. Lung epithelial and myeloid innate immunity in influenza-associated or COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: an observational study. Lancet Respir Med . 2022;10:1147–1159. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feys S, Heylen J, Carvalho A, Van Weyenbergh J, Wauters J, Gonçalves SM, et al. Variomic Study Group A signature of differential gene expression in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid predicts mortality in influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis. Intensive Care Med . 2023;49:254–257. doi: 10.1007/s00134-022-06958-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sarden N, Sinha S, Potts KG, Pernet E, Hiroki CH, Hassanabad MF, et al. A B1a-natural IgG-neutrophil axis is impaired in viral- and steroid-associated aspergillosis. Sci Transl Med . 2022;14:eabq6682. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abq6682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hérivaux A, Willis JR, Mercier T, Lagrou K, Gonçalves SM, Gonçales RA, et al. Lung microbiota predict invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its outcome in immunocompromised patients. Thorax . 2022;77:283–291. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kullberg RFJ, de Brabander J, Boers LS, Biemond JJ, Nossent EJ, Heunks LMA, et al. ArtDECO Consortium and the Amsterdam UMC COVID-19 Biobank Study Group Lung microbiota of critically ill patients with COVID-19 are associated with nonresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;206:846–856. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202202-0274OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sulaiman I, Chung M, Angel L, Tsay JJ, Wu BG, Yeung ST, et al. Microbial signatures in the lower airways of mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients associated with poor clinical outcome. Nat Microbiol . 2021;6:1245–1258. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00961-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lloréns-Rico V, Gregory AC, Van Weyenbergh J, Jansen S, Van Buyten T, Qian J, et al. Clinical practices underlie COVID-19 patient respiratory microbiome composition and its interactions with the host. Nat Commun . 2021;12:6243. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Imbert S, Revers M, Enaud R, Orieux A, Camino A, Massri A, et al. Lower airway microbiota compositions differ between influenza, COVID-19 and bacteria-related acute respiratory distress syndromes. Crit Care . 2024;28:133. doi: 10.1186/s13054-024-04922-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martín-Loeches I, Sanchez-Corral A, Diaz E, Granada RM, Zaragoza R, Villavicencio C, et al. H1N1 SEMICYUC Working Group Community-acquired respiratory coinfection in critically ill patients with pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus. Chest . 2011;139:555–562. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klein EY, Monteforte B, Gupta A, Jiang W, May L, Hsieh Y-H, et al. The frequency of influenza and bacterial coinfection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses . 2016;10:394–403. doi: 10.1111/irv.12398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adelman MW, Bhamidipati DR, Hernandez-Romieu AC, Babiker A, Woodworth MH, Robichaux C, et al. Emory COVID-19 Quality and Clinical Research Collaborative members Secondary bacterial pneumonias and bloodstream infections in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2021;18:1584–1587. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1093RL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pickens CO, Gao CA, Cuttica MJ, Smith SB, Pesce LL, Grant RA, et al. NU COVID Investigators Bacterial superinfection pneumonia in patients mechanically ventilated for COVID-19 pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;204:921–932. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202106-1354OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rouzé A, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, Metzelard M, Du Cheyron D, Lambiotte F, et al. coVAPid Study Group Early bacterial identification among intubated patients with COVID-19 or influenza pneumonia: a European multicenter comparative clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;204:546–556. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0030OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russell CD, Fairfield CJ, Drake TM, Turtle L, Seaton RA, Wootton DG, et al. ISARIC4C investigators Co-infections, secondary infections, and antimicrobial use in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 during the first pandemic wave from the ISARIC WHO CCP-UK study: a multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe . 2021;2:e354–e365. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(21)00090-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feys S, Cardinali M, Jacobs C, Lauwers HM, Gonçalves SM, Cunha C, et al. Bacterial microbiota and pathogens in the lungs of patients with severe influenza versus COVID-19 with or without aspergillosis. Presented at ESCMID Global. April 27, 2024, Barcelona, Spain: [Google Scholar]

- 27. Verweij P, Rijnders B, Brüggemann R, Azoulay E, Bassetti M, Blot S, et al. International expert review of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in ICU patients and recommendations for a case definition. Intensive Care Med . 2020;46:1524–1535. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti A, Chen SCA, Colombo AL, Hoenigl M, et al. European Confederation of Medical Mycology International Society for Human Animal Mycology; Asia Fungal Working Group; INFOCUS LATAM/ISHAM Working Group; ISHAM Pan Africa Mycology Working Group; European Society for Clinical Microbiology; Infectious Diseases Fungal Infection Study Group; ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Critically Ill Patients; Interregional Association of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobial Chemotherapy; Medical Mycology Society of Nigeria; Medical Mycology Society of China Medicine Education Association; Infectious Diseases Working Party of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology; Association of Medical Microbiology; Infectious Disease Canada. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis . 2021;21:e149–e162. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30847-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Willis JR, González-Torres P, Pittis AA, Bejarano LA, Cozzuto L, Andreu-Somavilla N, et al. Citizen science charts two major “stomatotypes” in the oral microbiome of adolescents and reveals links with habits and drinking water composition. Microbiome . 2018;6:218. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0592-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods . 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res . 2013;41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davis NM, Proctor DM, Holmes SP, Relman DA, Callahan BJ. Simple statistical identification and removal of contaminant sequences in marker-gene and metagenomics data. Microbiome . 2018;6:226. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rivera-Pinto J, Egozcue JJ, Pawlowsky-Glahn V, Paredes R, Noguera-Julian M, Calle ML. Balances: a new perspective for microbiome analysis. mSystems . 2018;3:e00053-18. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00053-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis . 2020;71:1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Natalini JG, Singh S, Segal LN. The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nat Rev Microbiol . 2023;21:222–235. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00821-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Starner TD, Barker CK, Jia HP, Kang Y, McCray PB., Jr CCL20 is an inducible product of human airway epithelia with innate immune properties. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol . 2003;29:627–633. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0272OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giacobbe DR, Prattes J, Wauters J, Dettori S, Signori A, Salmanton-García J, et al. ECMM-CAPA Study Group Prognostic impact of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid galactomannan and aspergillus culture results on survival in COVID-19 intensive care unit patients: a post hoc analysis from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) COVID-19-Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis Study. J Clin Microbiol . 2022;60:e0229821. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02298-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feys S, Hoenigl M, Gangneux J-P, Verweij PE, Wauters J. Fungal fog in viral storms: necessity for rigor in aspergillosis diagnosis and research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2024;209:631–633. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202310-1815VP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Clancy CJ, Schwartz IS, Kula B, Nguyen MH. Bacterial superinfections among persons with coronavirus disease 2019: a comprehensive review of data from postmortem studies. Open Forum Infect Dis . 2021;8:ofab065. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vanderbeke L, Janssen NAF, Bergmans DCJJ, Bourgeois M, Buil JB, Debaveye Y, et al. Dutch-Belgian Mycosis Study Group Posaconazole for prevention of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill influenza patients (POSA-FLU): a randomised, open-label, proof-of-concept trial. Intensive Care Med . 2021;47:674–686. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Agrawal U, Bedston S, McCowan C, Oke J, Patterson L, Robertson C, et al. Severe COVID-19 outcomes after full vaccination of primary schedule and initial boosters: pooled analysis of national prospective cohort studies of 30 million individuals in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Lancet . 2022;400:1305–1320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01656-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.