Abstract

Objective

To assess the diagnostic value of C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT) for anastomotic leakage (AL) following colorectal surgery.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed data for patients who underwent colorectal surgery at our hospital between November 2019 and December 2023. CRP and PCT were measured postoperatively to compare patients with/without AL, and changes were compared between low- and high-risk groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of CRP and PCT to identify AL in high-risk patients.

Results

Mean CRP was 142.53 mg/L and 189.57 mg/L in the low- and high-risk groups, respectively, on postoperative day (POD)3. On POD2, mean PCT was 2.75 ng/mL and 8.16 ng/mL in low- and high-risk patients, respectively; values on POD3 were 3.53 ng/mL and 14.86 ng/mL, respectively. The areas under the curve (AUC) for CRP and PCT on POD3 were 0.71 and 0.78, respectively (CRP cut-off: 235.64 mg/L; sensitivity: 96%; specificity: 89.42% vs PCT cut-off: 3.94 ng/mL; sensitivity: 86%; specificity: 93.56%; AUC: 0.78). The AUC, sensitivity, and specificity for the combined diagnostic ability of CRP and PCT on POD3 were 0.92, 90%, and 100%, respectively (cut-off: 0.44).

Conclusions

Combining PCT and CRP on POD3 enhances the diagnostic accuracy for AL.

Keywords: Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, anastomotic leakage, colon leakage score, postoperative, sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic accuracy

Introduction

Anastomotic leak (AL) is a severe complication that can occur after colorectal surgery, leading to significant postoperative morbidity. 1 These leaks typically manifest near the fifth or sixth day following surgery, although they can occasionally occur shortly after the procedure.2–3 The incidence of AL varies between 2% and 14%, with a higher incidence observed with anastomosis of the lower rectum. 4 The development of AL can have serious long-term consequences, including the need for a permanent stoma, chronic sepsis, delays in administering chemotherapy, increased risk of local recurrence, and reduced overall survival. 5

The current implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) and multimodal rehabilitation protocols has successfully facilitated early discharge for patients who undergo colorectal surgery.6–7 As a result, there is a growing interest in identifying a dependable diagnostic method to predict AL in its early stages, prior to the onset of sepsis symptoms. Early identification of AL would enable safe and early discharge without increasing the risk of a late AL diagnosis, which can be associated with severe consequences.

Recently, serum biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin (PCT), have been studied in relation to AL.8–10 However, important issues remain and are subject to debate. These include determining the optimal timing for measuring these biomarkers, identifying the most accurate biomarkers, and investigating whether combining multiple biomarkers can enhance their diagnostic value.

The main objective of this study was to assess the reliability of CRP and PCT in detecting AL early, specifically, on the third postoperative day (POD), in patients at high risk for colorectal AL. In addition, the study aimed to compare the reliability of various markers, identify the optimal cut-off value for each marker in detecting AL, and explore the potential improvement in AL diagnosis reliability through their combination.

Materials and methods

Study population and data collection

We performed a retrospective analysis of all consecutive colorectal cancer patients who underwent elective resection with anastomosis without a stoma at the General Surgery Department of Nanjing Yimin Hospital between November 2019 and December 2023. The exclusion criteria were: intraoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy, multiple anastomoses, emergency setting, benign disease, age under 18 years, and lack of informed consent. We collected the patients’ preoperative demographic characteristics, type of surgical resection, type of surgical approach, and anastomotic technique, as well as whether the patient developed AL. All patients included in the study underwent blood testing for CRP and PCT on PODs 1 to 3.

Dekker et al. developed a scoring system called the colon leakage score (CLS) to assess the risk of AL and aid in preoperative and postoperative planning. 11 The CLS incorporates 11 parameters, namely age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) status, body mass index (BMI), history of intoxication (smoking, alcohol, steroid use), history of neoadjuvant therapy, history of emergency surgery, anastomotic distance from the anal verge, additional procedure, amount of blood loss, and duration of surgery. 12 The CLS score is categorized into two groups: ≤11 for a low risk of AL and >11 for a high risk. 13

An exemption was received regarding ethical approval for this retrospective study from the Institutional Review Board of Nanjing Yimin Hospital. The images were fully anonymized before analysis by the authors, and the investigators de-identified all patient information. The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. 14 Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Definition of AL

In this study, we adopted the definition of AL proposed by The United Kingdom Surgical Infection Study Group in 1991. In accordance with that definition, AL was defined as the presence of a fecaloid discharge, emission of fecal material from the wound, extravasation of contrast on enema, evidence of postoperative peritonitis at a reintervention, and/or the presence of fluid or air in the anastomotic region during computed tomography (CT). 15

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation, while categorical variables were reported as number and percentage. The normality of the data was assessed using the D’Agostino–Pearson test. The Friedman test was used to analyze the changes in CRP and PCT levels at specific time points. Nonparametric analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney test to compare differences between groups. The diagnostic accuracy of CRP and PCT for detecting AL was determined by constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and calculating the area under the curve (AUC). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

One hundred twenty-six patients who underwent colorectal cancer resection were enrolled in this study; 13 were excluded owing to postoperative loss of follow-up. Of the total number of patients, 84 underwent a laparoscopic procedure, while 21 underwent laparotomy resection. Eight patients initially scheduled for laparoscopy underwent conversion to laparotomy. The patients comprised 67 men and 46 women, with an average age of 68.3 years and a BMI of 26.5 kg/m2. Of the 113 included patients, 20 were classified as ASA grade I, 72 as ASA grade II, and 21 classified as ASA grade III. All patients underwent successful colonic resections, with the following distribution: 36 right colectomies, 18 left colectomies, 9 transverse resections, 23 sigmoid resections, 3 ileocecal resections, and 24 low anterior resections. Among the patients, 86 underwent mechanical anastomosis while 27 underwent manual anastomosis. Eleven resections (9.7%) resulted in AL as a complication. On the basis of the CLS, 59 patients were classified as having a low risk of developing AL (CLS ≤ 11), whereas 54 patients were classified as having a high risk of developing AL (CLS > 11).

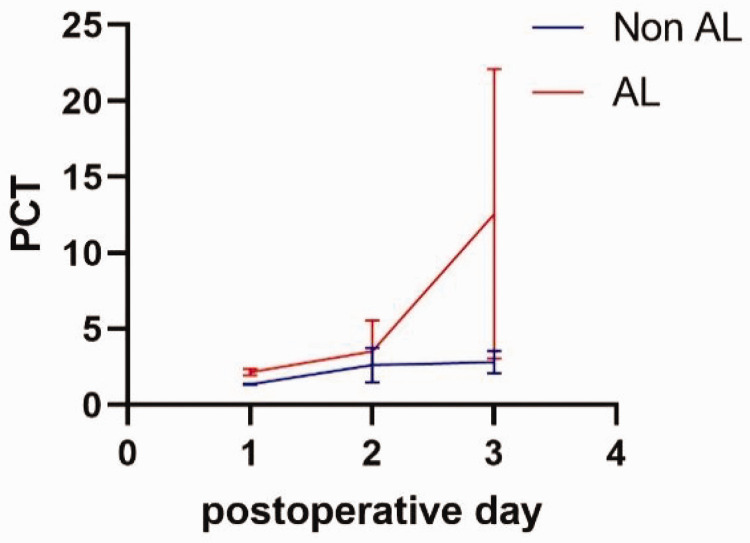

Differences in CRP and PCT values during the postoperative course were observed between PODs 1 to 3, as shown in Table 1, Figure 1, and Figure 2. The mean CRP value increased on POD 2 and POD 3 in all patients, with the peak CRP level significantly higher in the AL group only on POD 3. On POD 3, the mean CRP values were 131.26 mg/L in non-AL patients and 325.95 mg/L in AL patients (p < 0.01). Similarly, the mean PCT increased on PODs 2 and 3 in all patients, but the increase in PCT was significantly higher among patients with AL only on POD 3. The mean PCT on POD 2 was 2.63 ng/mL in non-AL patients and 3.52 ng/mL in AL patients, whereas on POD 3, the values were 2.82 ng/mL and 12.56 ng/mL, respectively (p < 0.01).

Table 1.

CRP and PCT values on PODs 1 to 3 in non-AL and AL patients.

| Parameter | Non-AL (n = 102) | AL (n = 11) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP POD 1, mg/L | 43.51 ± 12.23 | 58.36 ± 22.31 | 0.62 |

| CRP POD 2, mg/L | 123.92 ± 30.44 | 136.32 ± 34.42 | 0.54 |

| CRP POD 3, mg/L | 131.26 ± 32.61 | 325.95 ± 56.31 | <0.01 |

| PCT POD 1, ng/mL | 1.35 ± 0.05 | 2.16 ± 0.22 | 0.72 |

| PCT POD 2, ng/mL | 2.63 ± 1.15 | 3.52 ± 2.05 | 0.57 |

| PCT POD 3, ng/mL | 2.82 ± 0.75 | 12.56 ± 9.52 | <0.01 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day; PCT, procalcitonin; AL, anastomotic leak.

Figure 1.

Average CRP changes over time.

CRP, C-reactive protein; AL, anastomotic leak.

Figure 2.

Average PCT changes over time.

PCT, procalcitonin; AL, anastomotic leak.

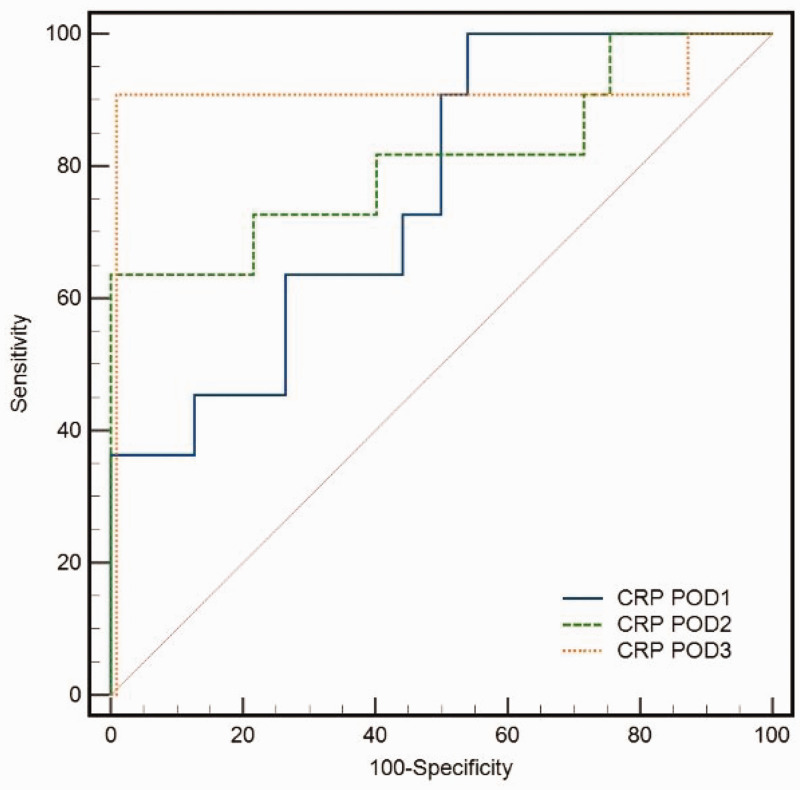

The analysis of ROC curves revealed that the AUC for CRP on POD 3 was 0.83, while that for PCT was 0.85. The calculated cut-off value for CRP on POD 3 was 258.65 mg/L, which resulted in a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 87.43% for AL. Similarly, the calculated cut-off value for PCT on POD 3 was 3.84 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 94.76% for AL (Table 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4).

Table 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as diagnostic tests for anastomotic leakage among all included patients.

| Parameter | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cut-off | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP POD 1, mg/L | 63 | 68.87 | 52.65 | 0.62 | 0.46 |

| CRP POD 2, mg/L | 68 | 71.43 | 128.77 | 0.68 | 0.76 |

| CRP POD 3, mg/L | 94 | 87.43 | 258.65 | 0.83 | 0.025 |

| PCT POD 1, ng/mL | 60 | 72.54 | 1.85 | 0.68 | 0.69 |

| PCT POD 2, ng/mL | 83 | 85.65 | 3.05 | 0.72 | 0.41 |

| PCT POD 3, ng/mL | 85 | 94.76 | 3.84 | 0.85 | 0.013 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day; PCT, procalcitonin; AUC, area under the curve.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of serum CRP in patients with AL.

CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day.

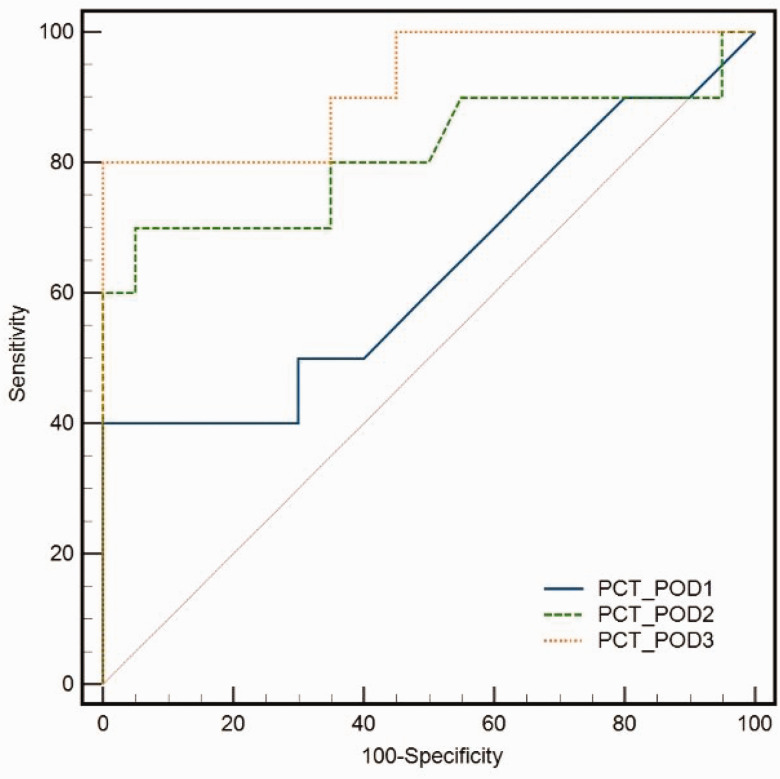

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of serum PCT in patients with AL.

PCT, procalcitonin; POD, postoperative day.

Differences in CRP and PCT values between low- and high-risk groups were observed from PODs 1 to 3, as shown in Table 3. On POD 3, the mean CRP values were 142.53 mg/L in the low-risk group and 189.57 mg/L in the high-risk group (p = 0.013). The mean PCT increased on PODs 2 and 3 in all patients, but the increase in PCT was significantly higher among high-risk patients on PODs 2 and 3. The mean PCT on POD 2 was 2.75 ng/mL in low-risk patients and 8.16 ng/mL in high-risk patients (p = 0.021), while on POD 3, the values were 3.53 ng/mL and 14.86 ng/mL, respectively (p = 0.006).

Table 3.

CRP and PCT values on PODs 1 to 3 in low- and high-risk AL patients.

| Parameter | Low-risk group (CLS ≤11, n = 59) | High-risk group (CLS >11, n = 54) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRP POD 1, mg/L | 33.54 ± 9.54 | 38.13 ± 13.25 | 0.082 |

| CRP POD 2, mg/L | 131.12 ± 25.65 | 136.32 ± 31.53 | 0.409 |

| CRP POD 3, mg/L | 142.53 ± 28.33 | 189.57 ± 31.61 | 0.013 |

| PCT POD 1, ng/mL | 1.57 ± 0.03 | 2.41 ± 0.35 | 0.605 |

| PCT POD 2, ng/mL | 2.75 ± 1.53 | 8.16 ± 2.21 | 0.021 |

| PCT POD 3, ng/mL | 3.53 ± 0.41 | 14.86 ± 4.64 | 0.006 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day; PCT, procalcitonin; CLS, colon leakage score.

The analysis of ROC curves in high-risk patients revealed that the AUC for CRP on POD 3 was 0.71, while that for PCT was 0.78. The calculated cut-off value for CRP on POD 3 was 235.64 mg/L, which resulted in a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 89.42% for AL. Similarly, the calculated cut-off value for PCT on POD 3 was 3.94 ng/mL, with a sensitivity of 86%, specificity of 93.56%, and AUC of 0.78 for AL. We found that the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity for the combined diagnostic abilities of CRP and PCT on POD 3 were 0.92, 90%, and 100%, respectively, at the cut-off of 0.44 (Table 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6).

Table 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as a diagnostic test for anastomotic leakage in high-risk patients.

| Parameter | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cut-off | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP POD 1 (mg/L) | 67 | 69.65 | 36.76 | 0.66 | 0.64 |

| CRP POD 2 (mg/L) | 76 | 78.45 | 129.66 | 0.69 | 0.51 |

| CRP POD 3 (mg/L) | 96 | 89.42 | 235.64 | 0.71 | 0.016 |

| PCT POD 1 (ng/mL) | 69 | 78.54 | 1.45 | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| PCT POD 2 (ng/mL) | 79 | 89.54 | 3.85 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| PCT POD 3 (ng/mL) | 86 | 93.56 | 3.94 | 0.78 | 0.028 |

| CRP POD3 + PCT POD 3 (ng/mL) | 90 | 100 | 0.44 | 0.92 | 0.004 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day; PCT, procalcitonin; AUC, area under the curve.

Figure 5.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of serum CRP in high-risk patients with AL. CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day.

Figure 6.

Adding PCT to CRP significantly enhanced the diagnosis of AL in high-risk patients on POD 3 (AUC: 0.92). CRP, C-reactive protein; POD, postoperative day; PCT, procalcitonin; AUC, area under the curve.

Discussion

CRP and PCT have long been used to identify septic complications.16–18 Our objective was to determine whether CRP and PCT could also be useful in predicting anastomotic complications in high-risk colorectal patients and assist in identifying patients suitable for early discharge, in accordance with the ERAS protocol. Combining a minimally invasive approach with the ERAS protocol, the average hospital postoperative stay could be safely reduced to 4 days. Fast-track protocols promote early discharge, but may result in delayed diagnosis of anastomotic dehiscence.19–21 Early detection of AL is crucial for prompt treatment, as delayed diagnosis is associated with higher mortality rates. 22 The ideal biochemical markers should have the potential to identify patients at risk of surgical complications before the onset of clinical symptoms.23–25 This could potentially aid in distinguishing patients who can be safely discharged early from those who require closer monitoring and a longer hospital stay.

CRP is a serum acute-phase reactant synthesized primarily in the liver. 26 This compound is released in response to stimulation by proinflammatory cytokines. CRP production is a component of the nonspecific acute-phase response, which occurs in various conditions, such as tissue damage, infection, inflammation, and malignant neoplasia. 27 In healthy young adults, the median CRP concentration is approximately 0.8 mg/L. However, in response to an acute-phase stimulus, the values can increase dramatically, even surpassing 500 mg/L. 28 The liver initiates the production of CRP swiftly after a single stimulus and reaches its highest level within 48 hours. 29 Following colorectal surgery, CRP levels exhibit a rapid increase on POD 1, reaching a peak on POD 2, and subsequently declining steadily to normal levels. 30 In patients with septic complications, the peak CRP value tends to occur on POD 3 and remains relatively stable thereafter. 31 In 2012, Warschkow et al. 32 performed a meta-analysis to assess the predictive value of CRP for infectious complications after colorectal surgery. The authors reported that measuring CRP on POD 4 provided satisfactory accuracy in predicting AL and suggested a cut-off value of 135 mg/L, with a negative predictive value of 89%. 32 Recently, Singh et al. 33 performed another meta-analysis (n = 2483), examining CRP as a predictor of AL on PODs 3, 4, and 5. The authors found that CRP had comparable diagnostic accuracy at all three time points, with a high negative predictive value of 97% but a low positive predictive value of 21% to 23%. 33 These findings confirm that while measuring CRP is useful to rule out AL, this biomarker is not a reliable indicator to confirm the presence of AL. In our study, we observed significantly elevated CRP levels on POD 3 in the AL group, which could increase the suspicion of AL and necessitate close monitoring. However, it is important to note that in some cases, elevated CRP levels may be attributed to other sources of sepsis, such as a wound, or respiratory or urinary tract infection, rather than AL.

PCT is a potential plasma biomarker that shows promise in identifying sepsis.34–37 PCT is a protein composed of 116 amino acids and is the precursor of calcitonin. 38 The parafollicular C-cells of the thyroid gland synthesize this protein. 39 PCT is released in response to bacterial endotoxins and its levels do not increase in response to non-infectious inflammation. 40 After major abdominal, vascular, or thoracic operations, patients often exhibit elevated concentrations of PCT on PODs 1 and 2. 41 Conversely, patients who have undergone minor, aseptic procedures tend to have lower PCT levels.42–44 This suggests that PCT may be triggered by transient bacterial contamination or bacterial translocation that occurs during the operation or preparation of intestinal anastomoses. PCT appears to be a more specific indicator of septic complications compared with CRP. Lagoutte et al. performed a study of the kinetics of PCT after colorectal resection. 45 The authors examined 100 patients and observed that in non-AL patients, PCT levels increased on POD 1, peaked on POD 2, and then gradually decreased. However, in comparison, patients with AL experienced a higher PCT peak on POD 1, followed by a decrease. While PCT showed better accuracy in predicting AL on POD 4, its correlation with AL was weaker compared with CRP. Our study showed that if PCT levels are significantly elevated on POD 3, this should raise suspicion regarding AL and necessitates close monitoring.

The CLS is a clinically relevant scoring system with a sensitivity of 84.6% and specificity of 87.2% for predicting preoperative anastomotic leaks. 11 The CLS considers the patient’s condition and preoperative variables. Our study aimed to assist in decision making for early discharge after colorectal cancer resection, specifically in patients at high risk of developing colorectal AL (CLS >11). We observed significantly higher CRP and PCT levels on POD 3 in patients with AL. Both markers demonstrated similar specificity and sensitivity, with ROC analysis indicating higher accuracy for PCT. In high-risk patients, measuring both PCT and CRP on POD 3 yielded a high diagnostic value for AL, with a sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 100%, and AUC of 0.92. Our study confirms that CRP and PCT are reliable early predictors of anastomotic dehiscence. Based on these findings and previous results, we propose the routine implementation of CRP and PCT testing on POD 3 in fast-track protocols, especially in patients with a high risk of developing AL. After hospital admission, clinicians should perform a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s physical condition and be knowledgeable about the CLS system to identify high-risk patients for AL. This will enable individualized postoperative management and early intervention to prevent AL.

The limitations of our study include the need to confirm whether the conclusions drawn from high-risk patients can be generalized to all colorectal cancer surgery patients. Future research will focus on verifying these conclusions in a broader population of patients who meet the inclusion criteria. In addition, this was a retrospective study with a small sample size, highlighting the need for larger, prospective, multicenter studies. Furthermore, CRP and PCT testing involves costs and blood collection, which may not be suitable for all patients, particularly those with tumors or malnutrition.

Conclusion

In the context of fast-track protocols that require early patient discharge after colorectal surgery, it is crucial to identify a diagnostic tool to assist surgeons in promptly diagnosing AL in high-risk patients. Our study demonstrated that PCT is a valuable biomarker for the early detection of AL following colorectal surgery. CRP also appears to be a reliable indicator, and measuring both markers on POD 3 improves the diagnostic accuracy for AL. Further research is recommended to identify early and specific predictors of AL. There is a pressing need to develop a simple, non-invasive, and cost-effective method for predicting colorectal AL.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients for their cooperation and consent for publication of this report.

Author contributions: Yilong Hu drafted the manuscript. Junjie Ren performed the literature review. Zhixin Lv and He Liu performed the procedures. Xiewu Qiu collected and analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD: Yilong Hu https://orcid.org/0009-0008-8078-0428

Data availability statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Foppa C, Ng SC, Montorsi M, et al. Anastomotic leak in colorectal cancer patients: new insights and perspectives. Eur J Surg Oncol 2020; 46: 943–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stearns AT, Liccardo F, Tan KN, et al. Physiological changes after colorectal surgery suggest that anastomotic leakage is an early event: a retrospective cohort study. Colorectal Dis 2019; 21: 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsalikidis C, Mitsala A, Mentonis VI, et al. Predictive factors for anastomotic leakage following colorectal cancer surgery: where are we and where are we going? Curr Oncol 2023; 30: 3111–3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott FD, Heeney A, Kelly ME, et al. Systematic review of preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative risk factors for colorectal anastomotic leaks. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 462–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komen N, De Bruin RW, Kleinrensink GJ, et al. Anastomotic leakage, the search for a reliable biomarker. A review of the literature. Colorectal Dis 2008; 10: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes C, Vaz Gomes M, Rosete M, et al. The impact of the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol on colorectal surgery in a Portuguese tertiary hospital. Acta Med Port 2023; 36: 254–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seow-En I, Wu J, Yang LWY, et al. Results of a colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme and a qualitative analysis of healthcare workers’ perspectives. Asian J Surg 2021; 44: 307–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierrakos C, Velissaris D, Bisdorff M, et al. Biomarkers of sepsis: time for a reappraisal. Crit Care 2020; 24: 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bona D, Danelli P, Sozzi A, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 27: 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goulart A, Ferreira C, Estrada A, et al. Early inflammatory biomarkers as predictive factors for freedom from infection after colorectal cancer surgery: a prospective cohort study. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2018; 19: 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dekker JW, Liefers GJ, De Mol van Otterloo JC, et al. Predicting the risk of anastomotic leakage in left-sided colorectal surgery using a colon leakage score. J Surg Res 2011; 166: e27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu XQ, Zhao B, Zhou WP, et al. Utility of colon leakage score in left-sided colorectal surgery. J Surg Res 2016; 202: 398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao LS, Millas SG. Predicting the risk of anastomotic leakage in left-sided colorectal surgery using a Colon Leakage Score. J Surg Res 2012; 173: 246–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, STROBE Initiative et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peel AL, Taylor EW. Proposed definitions for the audit of postoperative infection: a discussion paper. Surgical Infection Study Group. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1991; 73: 385–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.August BA, Kale-Pradhan PB, Giuliano C, et al. Biomarkers in the intensive care setting: a focus on using procalcitonin and C-reactive protein to optimize antimicrobial duration of therapy. Pharmacotherapy 2023; 43: 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu X, Li K, Zheng J, et al. Usage of procalcitonin and sCD14-ST as diagnostic markers for postoperative spinal infection. J Orthop Traumatol 2022; 23: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeza-Murcia M, Valero-Navarro G, Pellicer-Franco E, et al. Early diagnosis of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: prospective observational study of the utility of inflammatory markers and determination of pathological levels. Updates Surg 2021; 73: 2103–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Telem DA, Sur M, Tabrizian P, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal anastomotic dehiscence after hospital discharge: impact on patient management and outcome. Surgery 2010; 147: 127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamini N, Cassini D, Giani A, et al. Computed tomography in suspected anastomotic leakage after colorectal surgery: evaluating mortality rates after false-negative imaging. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2020; 46: 1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhama AR, Maykel JA. Diagnosis and management of chronic anastomotic leak. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2021; 34: 406–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edomskis PP, Goudberg MR, Sparreboom CL, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 in relation to patients with complications after colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Int J Colorect Dis 2020; 36: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agnello L, Sasso BL, Giglio RV, et al. Monocyte distribution width as a biomarker of sepsis in the intensive care unit: a pilot study. Ann Clin Biochem 2021; 58: 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agnello L, Vidali M, Lo Sasso B, et al. Monocyte distribution width (MDW) as a screening tool for early detecting sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med 2022; 60: 786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnello L, Bivona G, Parisi E, et al. Presepsin and midregional proadrenomedullin in pediatric oncologic patients with febrile neutropenia. Lab Med 2020; 51: 585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajab IM, Hart PC, Potempa LA. How C-reactive protein structural isoforms with distinctive bioactivities affect disease progression. Front Immunol 2020; 11: 2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friend SF, Nachnani R, Powell SB, et al. C-reactive protein: marker of risk for post-traumatic stress disorder and its potential for a mechanistic role in trauma response and recovery. Eur J Neurosci 2022; 55: 2297–2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeller J, Zeller J, Bogner B, et al. Transitional changes in the structure of C-reactive protein create highly pro-inflammatory molecules: therapeutic implications for cardiovascular diseases. Pharmacol Ther 2022; 235: 108165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plebani M. Why C-reactive protein is one of the most requested tests in clinical laboratories? Clin Chem Lab Med 2023; 61: 1540–1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramanathan ML, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The impact of the peak (day 2) C-reactive protein (CRP) on the day 3 and day 4 CRP. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 595–595. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortega‐Deballon P, Facy O, Rat P. Diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein and white blood cell counts in the early detection of infectious complications after colorectal surgery. Int J Colorect Dis 2011; 27: 1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warschkow R, Beutner U, Steffen T, et al. Safe and early discharge after colorectal surgery due to C-reactive protein: a diagnostic meta-analysis of 1832 patients. Ann Surg 2012; 256: 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh PP, Zeng IS, Srinivasa S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of use of serum C-reactive protein levels to predict anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2014; 101: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schuetz P. How to best use procalcitonin to diagnose infections and manage antibiotic treatment. Clin Chem Lab Med 2023; 61: 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakstad B. The diagnostic utility of procalcitonin, interleukin-6 and interleukin-8, and hyaluronic acid in the Norwegian consensus definition for early-onset neonatal sepsis (EONS). Infect Drug Resist 2018; 11: 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Kushimoto S, Shibata Y, Koido Y, et al. The clinical usefulness of procalcitonin measurement for assessing the severity of bacterial infection in critically ill patients requiring corticosteroid therapy. J Nippon Med Sch 2007; 74: 236–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luzzani A, Polati E, Dorizzi R, et al. Comparison of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of sepsis. Crit Care Med 2003; 31: 1737–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russwurm S, Stonans I, Stonane E, et al. Procalcitonin and CGRP-1 mrna expression in various human tissues. Shock 2001; 16: 109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molter GP, Soltész S, Kottke R, et al. Procalcitonin plasma concentrations and systemic inflammatory response following different types of surgery. Anaesthesist 2003; 52: 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitaka C. Clinical laboratory differentiation of infectious versus non-infectious systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 2005; 351: 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Oro N, Gauthreaux ME, Lamoureux J, et al. The use of procalcitonin as a sepsis marker in a community hospital. J Appl Lab Med 2019; 3: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meisner M, Tschaikowsky K, Hutzler A, et al. Postoperative plasma concentrations of procalcitonin after different types of surgery. Intensive Care Med 1998; 24: 680–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarbinowski R, Arvidsson S, Tylman M, et al. Plasma concentration of procalcitonin and systemic inflammatory response syndrome after colorectal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2005; 49: 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sablotzki A, Friedrich I, Mühling J, et al. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome following cardiac surgery: different expression of proinflammatory cytokines and procalcitonin in patients with and without multiorgan dysfunctions. Perfusion 2002; 17: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lagoutte N, Facy O, Ravoire A, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin for the early detection of anastomotic leakage after elective colorectal surgery: pilot study in 100 patients. J Visc Surg 2012; 149: e345–e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.